For many years staffers on The Motor Cycle would review their favourite bikes of the year. No-one is better qualified to continue that tradition than John Nutting, my former editor on Motor Cycle Weekly. If fact his review of the year goes further than that. This is a treat to read. Guvnor, you have the floor.

“WE MIGHT HAVE BEEN sliding into recession in 1980, with inflation rising above 20% and unemployment accelerating to more than two million, but that year motorcycles and mopeds were selling faster in the UK than in any year since World War II, or since for that matter. By then the British bike had all but disappeared, with the Triumph factory continuing to limp along with its traditional twins and the expectation that futuristic Norton rotary bikes might be launched being foiled by repeated delays. Only the new Hesketh vee-twin provided a glimmer of hope. In stark contrast, the Japanese factories were locked in a battle for market share. Two years earlier, Yamaha had vowed to topple Honda as the world’s leading motorcycle producer. But while it didn’t work out that way, the competition resulted in exciting new models being launched in every sector. Some might say that the growing demand for motorcycles was in response to the political and cultural gloom. Business was in upheaval following the election of Thatcher’s Conservative government a year earlier, with strikes in the steel industry and meltdown in the domestic automobile sector. Abroad, Iraq and Iran started their squabbles, and the siege of the Iranian embassy in London was ended by the SAS. Call me a

cynic, but with music fans making Don McLean’s Crying the top selling single of the year and post-punk band Talking Heads producing the top selling album (though there was the start of a Two-tone Mod music revival with bands like the Specials and The Jam) things couldn’t get much worse. But they did, with John Lennon being shot dead in New York in the December of that year. That really was the day that the music died. Road racing provided some relief with Kenny Roberts winning his third 500cc world title on the trot, and Britain’s Jock Taylor the sidecar class. Yamaha may have been the top dog in the big class but the writing was on the wall, with Suzuki’s square fours becoming the racer of choice. Honda, now dominant in world endurance racing and TT Formula 1, was still two years away from its road racing revival with two-strokes. With just over ten years since the superbike era started in 1969 with the launch of Honda’s CB750, Kawasaki’s Mach III and the BSA-Triumph 750cc triples, the factories had been upping their performance with a second generation of machines typified by six-cylinder machines like the Honda CBX and Kawasaki’s Z1300. Suzuki had launched its range of four-stroke fours and Yamaha offered its shaft-drive 750cc triples

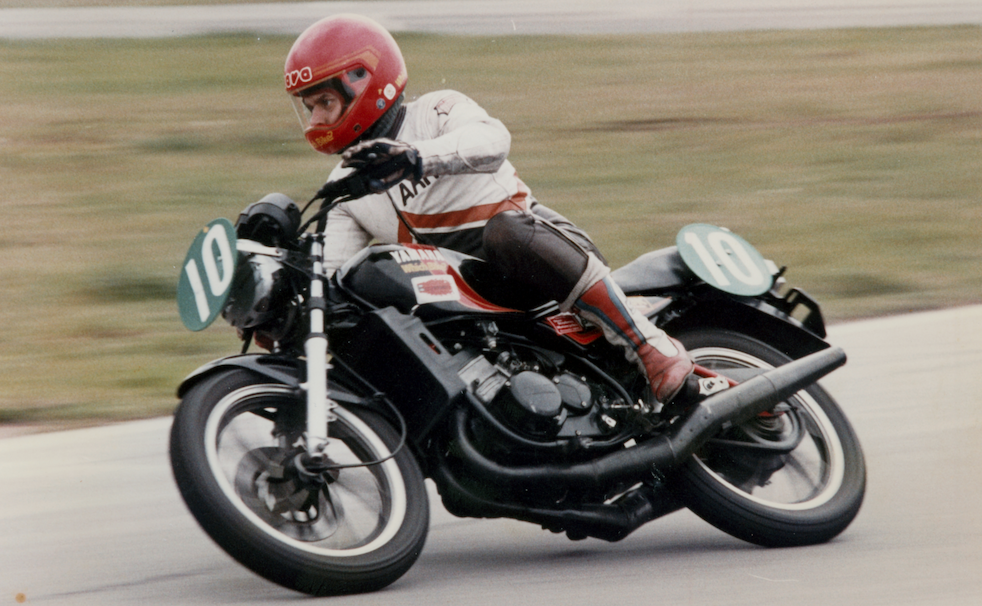

and 1,100cc fours. Riders couldn’t get enough of them, and in 1980 UK sales grew to a peak of 315,641 units, made up of 225,101 motorcycles and 90,834 mopeds, according to the Motor Cycle Industry Association. It was motorcycles that provided the growth, with sales up 26% on five years earlier, and would be the highest ever in the post-war period. To put this in context, in 2015 motorcycle sales in the UK were 82,590, up 18%. The lowest UK sales were in 1993, with just 40,731 units. First opportunity to see what was in store for the 1980 model year was at the Tokyo Show at the end of the previous year. Biggest surprise was Yamaha’s RD250LC and RD350LC twins, primarily aimed at the European market. For UK riders yet to pass their test, the smaller version represented a step change in performance with a top speed close to 100mph. Both offered a new subdued styling with a distinct lack of chrome, the GK design house drawing on ideas from a British team that included Mick Ofield, Bob Trigg and Dave Bean. Engines were based on Yamaha’s TZ racing machines with liquid-cooled cylinders, six-speed gearboxes and Monoshock rear suspension. Smooth and peaky power matched to hair-trigger handling offered a thrilling ride. Both bikes were a roaring success with the 350cc version being popular for production racing and the 250cc model largely contributing to the UK government’s decision to limit learners to 125cc machines a year or so later. Proposals to change the L-plate laws had already been tabled early in 1980 by transport minister Norman Fowler. Yamaha was also innovative with its big bikes as well. No doubt stung by comments that its 750cc shaft-drive triple launched in 1977 was too much of a tourer, it revealed the XJ650. While it also

featured shaft drive, this was more sporty, with the double-overhead-camshaft in-line four-cylinder engine slimmed down by mounting the generator above the gearbox. It offered fine handling, a great riding position but was let down by the peakiness of the power curve and poor fuel consumption. Later versions were upped to 750cc while chain-drive XJ550 followed. To inject new life into the shaft-drive XS750 triple, it was upped to 826cc with the XS850G and restyled for the European market. The range-leading XS1100 four, first launched in 1978, was also restyled as the 1.1 with a black finish and handlebar fairing. Other new models for 1980 included lightweights such as the XT250 ohc single trail bike and its road-going custom counterpart, the SR250 Special. Honda mostly didn’t offer anything completely new, but offered models based already established machines. For example, the range-topping six-cylinder CBX was improved with a better front fork and swing-arm bushes, but was slightly detuned, making it less of a hot rod. For touring types, the Gold Wing flat four was increased in capacity as the GL1100K, and restyled with a taller fuel tank, new side panels and fabricated aluminium-alloy Comstar wheels. Detail changes to Honda’s 16-valve dohc fours, the CB900F for Europe and the CB750F for the US launched for 1978, would be released until later in 1980, with the CB900F four getting vibration-absorbing mounts for the engine and the smaller CB750K with four pipes also uprated. At the same time, Honda also revealed its CB1100R homologation special, based on the CB900F, which would become a winner worldwide in production racing. In the US, the 750 four was augmented with the CB900C, a custom-styled machine featuring a shaft drive and an extra two-speed gearbox to lower engine speed for cruising. The most innovation for the 1980 model year from Honda was devoted to its lightweights, with the 250cc ohc engine used in its XL250 trail bike adapted for road use in the CB250RS, which proved to be a surprisingly lively machine, despite its modest 27bhp power. Slim with a

sporty riding position, the RS was much more responsive and agile than Honda’s 250cc twins, and very economical to run. For commuters, the CM200T twin was an adaptation of Honda’s 125cc twin, and while a bit dull offered dependable reliability. For teenage newcomers to motorcycling, Honda launched two fresh 50cc two-strokes, the MB50 and MT50, based on the same spine-frame platform and conforming to the new ‘moped’ regulations in which speeds were limited to just over 30mph. Great styling set these sports and trail style machines apart from the pack. Also based on the same engine was the H100 commuter single. At Kawasaki it was also a time for consolidation across the range, with the Z1000 dohc four and its shaft-drive Z1000ST variant continuing almost unchanged, along with the huge six-cylinder Z1300. High spot in 1980 was detail improvements to the Mk2 version of the Z1R, powered by the 94bhp Z1000 Mk2 engine but with better steering provided by a 19-inch front wheel, rather than the fashionable but inappropriate 18-incher. On the face of it, the new and conventionally-styled four-cylinder Z750E looked nothing more than an overbored Z650, but it was much more than that, with a revised chassis offering a lower seat, more compliant suspension and better handling. That made the 738cc dohc four a much better performer than the latest Honda and Suzuki equivalents, because they were larger, being derived from 1,100cc and 900cc equivalents. With a weight of just 210kg and 74bhp the Z750E could punch well above its category, with a top speed approaching 125mph and class leading quarter-mile acceleration in the mid 12s. Kawasaki’s Z550 four was also new in 1980, and the additional capacity added to the previous year’s Z500 four transformed it, with a top speed approaching 120mph and fine handling to match. At Suzuki, it had been four years since its newly developed four-strokes had been launched, and it was time to revitalise them. New range topper was the four-cylinder GSX1100, a restyled bigger-capacity version of the 998cc GS1000, and punching out 100bhp in a lighter package than Honda’s CBX it was a much more capable machine with a top speed approaching 140mph. Key feature of the 1,075cc engine was the four-valve combustion chamber design called Twin-Swirl, which was also used on the smaller-capacity GS750 for the US market and the GSX400E and GSX250 twins. The styling of the GSX1100, with a rectangular headlamp cowl and blocky fuel tank, might not have been to everyone’s taste, but Suzuki’s

management were already thinking of the future and had teased us at the end of 1979 by showing a prototype design from the pen of Hans Muth at Target Design, who had been responsible for the aerodynamic BMW R100RS sports tourer. While the base GSX1100 featured a cushy chassis with a soft suspension, the new Katana promised to be much more aggressive in its looks and handling. By the end of 1980, Suzuki had production versions of the GSX1100 Katana on show, and its design cues would be adopted across all of Suzuki’s range with two years. Suzuki had first used shaft drive for its big fours in 1979 with the GS850G, an exceptionally refined tourer that challenged BMW’s shaft-drive flat-twins. For 1980, Suzuki added the GS1000G, and with more power across the range it could only be better. New lightweights from Suzuki in 1980 included the SP400T, a larger capacity version of the four-stroke ohc SP370 trail bike, and its quirky road-going counterpart, the GN400T aimed at riders already interested in Yamaha SR500 singles. European motorcycle manufacture in 1980 was dominated by Germany’s BMW, followed by Moto Guzzi, Ducati, Benelli, Laverda, Cagiva and Morini in Italy. BMW had extended its range a year earlier with the additional of the 980cc R100RT tourer aimed primarily at the US market, but its pushrod ohv flat twins were largely unchanged, the emphasis remaining on smooth refinement at wallet-busting prices. But the Munich-based factory would spice up its twins later that year with mods to the engines and chassis. These mods included lighter flywheels, which with new carburettors would markedly improve throttle response, hard-coated alloy cylinder bores (reducing overall weight and sharpening handling and performance) and better Brembo disc brakes. And the mods really worked, turning the R100CS – the latest version of the R90S that kicked off BMW’s edgy evolution six years earlier – into a lively, wheelie-prone sportster. Of the Italian factories, Ducati

had the highest profile and was doing its best to keep up with demand for its 864cc vee-twin Mike Hailwood Replicas, while supporting what would be Tony Rutter’s first forays into a string of TT Formula 2 world titles. At the same time Ducati improved its 864cc desmo vee-twin Darmah road bike as the Darmah Sport, featuring a lowered frame and lifted suspension to improve cornering clearance. Launched alongside the Darmah Super Sport, which used an SS style fairing, the SD was described as Ducati’s best conventional – we’d say naked now – machine with few of the foibles of earlier versions but retaining the rock-solid Ducati steering. Two new models from Italy were Laverda’s 500cc Montjuic, a limited edition production racing version of the Alpino 8-valve dohc parallel twin, dubbed the ‘Son of Jota’ by UK importer Slater Brothers who developed the machine, and a 250cc version of Morini’s vee-twin roadster, which although exquisitely finished and delightful to ride was both expensive to buy and mistimed in view of the coming learner legislation in the UK. In the UK at the beginning of 1980 the only factory making big bikes was the Meriden Co-operative, which continued with the production of its venerable 750cc Triumph twins in the face of an increasingly difficult financial situation, because the factory still owed the government £5 million, given as a loan by the previous Labour administration. But they weren’t giving up and launched an electric-start version of the Bonneville, called the T140ES. Build-quality had been improved and along with a number of detail improvements, such as in the lubrication, the starter motor was much more reliable than Norton’s had been on the Commando. But the Bonneville was regarded less as a classic as an anachronism with engine vibration still spoiling the fun. Talking of Norton, the rump of the factory was still developing its rotary engine, and during 1980 I was promised a scoop story about the imminent launch of the Classic, a conventional looking machine with the latest version of the super-smooth air-cooled twin-rotor Wankel-based unit that I’d first ridden in 1974. As it turned out the plans were premature, but the Classic did eventually appear a couple of years later under new ownership. British hopes for a revival in the domestic motorcycle industry were buoyed in the Spring of 1980 when Lord Hesketh pulled the covers of his new V1000 dohc vee-twin. Launched at

his country retreat near Towcester, the superbike has been developed by the best that the domestic industry could muster, and details of the factory at Daventry where the bike would be manufactured were revealed. But suspicions that the Hesketh wasn’t fully developed for production were confirmed when I later rode the prototype which had an awful gearbox action. There were also problems with the lubrication and the subsequent delays necessary to sort it out undermined Hesketh’s investment plans. The whole operation was scaled down and never met its targets. It was a minor issue in a domestic market that couldn’t get enough bikes, but one that probably set back any effort to rebuild the industry, at least for another decade when Triumph was restarted by John Bloor. But undoubtedly, the memorable machines of the year were Yamaha’s LC twins, Suzuki’s GSX1100, Kawasaki’s Z750E and, for me at least, Honda CB250RS. THE BIKES OF 1980—BMW R100CS: Engine: 980cc ohv flat-twin, five speed, shaft drive. Peak power: 70bhp at 7,250rpm. Wheelbase: 1,465 mm. Weight: 220kg dry. Maximum speed (est): 125mph. St ¼ mile: 12.8s. Fuel consumption: 50mpg. Ducati 900SD Darmah: Engine: 864cc ohc desmo vee-twin, five speed, chain drive. Peak power: 62bhp at 7,000rpm. Wheelbase: 1,519 mm. Weight: 220kg dry. Maximum speed (est): 115mph. St ¼ mile: 13.3s. Fuel consumption: 42mpg. Hesketh V1000: Engine: 992cc dohc vee-twin, five speed, chain drive. Peak power: 86bhp at 6,500rpm. Wheelbase: 1,560 mm. Weight: 227kg dry. Maximum speed (est): 130mph. St ¼ mile: 12.5s. Fuel consumption: 50mpg. Honda CB250RS: Engine: 248cc ohc single, five speed, chain drive. Peak power: 26bhp at 9,000rpm. Wheelbase: 1,359 mm. Weight: 125kg dry. Maximum speed (MIRA): 88.2mph. St ¼ mile: 16.7s. Fuel consumption: 65mpg. Kawasaki Z750E: Engine: 738cc dohc in-line four, five speed, chain drive. Peak power: 74bhp at 9,000rpm. Wheelbase: 1,420 mm. Weight: 210kg dry. Maximum speed (est): 122mph. St ¼ mile: 12.5s. Fuel consumption: 45mpg. Suzuki GSX1100: Engine: 1,075cc dohc 16-valve in-line four, five speed, chain drive. Peak power: 100bhp at 8,500rpm. Wheelbase: 1,519mm. Weight: 232kg dry.Maximum speed (est): 135mph. St ¼ mile: 12.2s. Fuel consumption: 45mpg. Suzuki GS1000G: Engine: 997cc dohc in-line four, five speed, shaft drive. Peak power: 91bhp at 8,500rpm. Wheelbase: 1,500mm. Weight: 255kg dry. Maximum speed (est): 130mph. St ¼ mile: 12.4s. Fuel consumption: 43mpg. Triumph T140ES: Engine: 744cc ohv parallel twin, five speed, chain drive. Peak power: 50.5bhp at 6,500rpm. Wheelbase: 56in. Weight: 456lb full tank. Maximum speed (est): 110mph. St ¼ mile: 13.9s. Fuel consumption: 53mpg. Yamaha RD250LC (RD350LC): Engine: 247cc (347cc) liquid-cooled two-stroke parallel twin, six-speed, chain drive. Peak power: 35.5bhp (47bhp) at 8,500rpm. Wheelbase: 1,360mm. Weight: 139kg (143kg) dry. Maximum speed (MIRA): 99.7mph (107.1mph). St ¼ mile: 15.50s (13.83s). Fuel consumption: 42mpg (40mpg). Yamaha XJ650: Engine: 653cc dohc in-line four, five speed, shaft drive. Peak power: 68bhp at 8,500rpm. Wheelbase: 1,435 mm. Weight: 204kg dry. Maximum speed (est): 125mph. St ¼ mile: 12.8s. Fuel consumption: 45mpg. Yamaha XS850G: Engine: 826cc dohc in-line triple, five speed, shaft drive. Peak power: 74bhp at 8,000rpm. Wheelbase: 1,450 mm. Weight: 241kg dry. Maximum speed (est): 125mph. St ¼ mile: 12.9s. Fuel consumption: 40mpg.

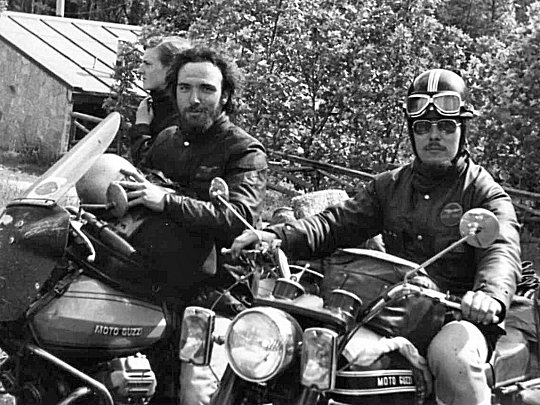

Here’s a report of the classic Stella Alpina Rally courtesy of mon ami Fanfan, who has contributed so much to this timeline. He wrote it just before Christmas 2025 for the excellent lpmcc.net which is required reading for anyone with an interest in rallying and touring (they also do a good line in awful jokes). It’s not the cheerful reminiscing you might expect, as Fanfan will explain. Mon cher ami, vous avez la parole…

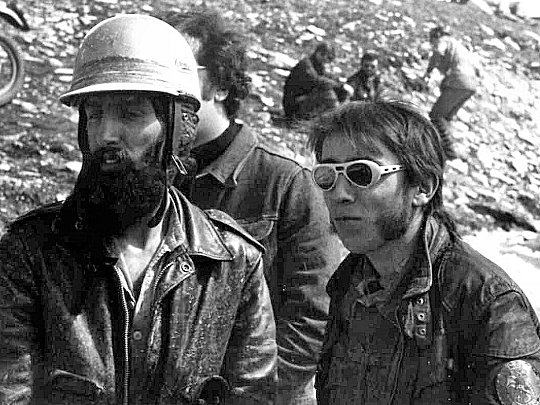

THE HOLIDAY SEASON is fast approaching, and with it the end of a year that has flown by without warning. As we stand on the threshold of 2026, I would like to extend my most sincere wishes to each and every one of you for this end-of-year period. This moment is also an opportunity to look back and bring back to light a significant—and painful—episode in the history of motorcycle touring: the Stella Alpina 1980. Forty-five years later, this event is still too often relegated to oblivion, even though it fully deserves its place in the collective memory of rally riders from all countries. Sunday, 13 July 1980, should have been bathed in golden sunlight. As every year, Luigi’s restaurant — the unofficial headquarters of France’s most devoted motorcycle touring fanatics—was buzzing. Tables overflowed with friends, laughter rang out, jokes flew, and cold beers clinked. Even the surrounding mountains seemed to approve, standing tall as silent witnesses to the camaraderie. Everything breathed friendship, brotherhood, and the thrill of the open road. Then came the bus, inching down Via Medail, the main street squeezed tight like a bottleneck. On one side, our motorcycles stood neatly lined up in front of Luigi’s; on the other, a carabinieri vehicle sat planted across the road, a defiant barrier. It was clear it had been placed there deliberately, a monument to authority. One small push and it could have moved, letting the bus pass with ease. But no — Italian police chose instead to command us, the riders, to clear our

machines, as if bending to their will was our only option. Cooperation? Clearly, that wasn’t on the agenda.What happened next was beyond belief. It came suddenly. Brutally. Surreally. As some riders began to shift their motorcycles, the leader of the unit — a brigadier named Antonio Cutillo — lost all sense of control. That name — I have never forgotten it. Forty-five years have passed, yet it lingers in my memory as if it were yesterday. You never forget a man capable of turning a calm, sunny afternoon into sheer chaos. Everything flipped in an instant. Brigadier Antonio Cutillo struck without warning. No provocation, no hesitation — he lunged at them, pistol in hand, shielded by his armed men. The blows came down quickly. Those with long hair, a jacket, or simply a face the officer didn’t like were pinned to the ground, handcuffed, and taken to the station like real criminals. The sound of the impacts and the cries of the victims echoed in the street, while witnesses could only stand by, helpless. At the station, the situation did not improve. Fists and batons were used on six of them: Jean-Louis Beltram aka ‘Toulouse’, Jean-Marc Roquet aka Genese, the late Belgium Phil Van Vlemmeren, and three other friends. When they were released, they bore the marks of the violence. Their injuries attested to an unprovoked and unjustifiable use of force. While they endured the blows, a tow truck carried off several motorcycles, their owners away at a nearby fair, unaware of the chaos awaiting them. The sun

continued to shine over Bardonecchia, but for us, the Stella Alpina had lost a bit of its light. What should have remained a friendly, festive gathering had been marked by injustice and violence. Laughter had vanished from the celebration. And in the eyes of the gathered riders, a single thought was clear: disbelief, and the bitter certainty that the Stella Alpina would never be the same again. One of the main causes of these incidents was the absence of the head of the Carabinieri, who had been stationed in Bardonecchia for many years and was therefore fully familiar with the Stella Alpina and its gatherings. That weekend, he was on leave in Turin. Taking advantage of his absence, his subordinate, Brigadier Antonio Cutillo, temporarily in command, seemed eager to make his mark in the boss’s place. According to Bardonecchia’s shopkeepers, who were shocked by the violence that occurred that Sunday, Cutillo had a habit of abusing his authority — and this was far from his first excess. To make matters worse, the other Carabinieri present were young recruits, recently assigned to Bardonecchia from various regions of Italy. Unfamiliar with the traditions and customs of the Stella Alpina, they could do nothing but follow their superior’s orders blindly, contributing to an atmosphere of tension and clumsy enforcement that could easily have been avoided. One might almost have wondered if a curse had fallen on the 1980 Stella Alpina. After the afternoon nightmare with the Carabinieri, everything seemed to spiral further into chaos. For many years, Sunday evenings had been the unmissable gathering: the French community

would come together to celebrate the end of the rally at the café-restaurant of our friend Luigi, alongside his sister Lucianna and her husband, Mario Viarengo, an exceptional cook. But that year, things were off to a bad start. After the violence of Brigadier Cutillo, who now had the motorcycle community squarely in his sights, and after our Italian hosts had suffered the consequences of his abuses, the café was temporarily closed. The long-awaited celebration could no longer take place, and the mood of the participants suffered even more. Despite everything, our hosts took the risk of defying the ban and continued to serve us drinks — not inside the establishment, but discreetly in their garden. Later in the afternoon, I met up with a group of friends at a pizzeria. They quickly filled me in on the latest news — of course, none of it good. The first was that many French participants, disgusted and disheartened by the day’s incidents, had already crossed back over the border, cutting short what was supposed to be their vacation in Bardonecchia. Among them were a group of young riders from Pornic, in Brittany. They had traveled nearly 960 kilometres on their Kreidler mopeds to experience, for the very first time, the Stella Alpina that had been so highly praised to them. Imagine their disappointment. They turned back, deeply disheartened. One of them summed up the rally with these words: “The Stella Alpina, the highest rally in Europe… but also the most policed.” Since the very first time I took part in this rally, we had always pitched our tents at the same traditional campsite in the heart of town, known at the time as ‘Campo Smith.’ In July 1980, staying true to tradition, we set up our tents there once again. That year, a large British delegation camped alongside us, mostly familiar faces, including our longtime friends Rodney Taylor and Colin ‘Codge’ Harris. The atmosphere, usually so friendly, had turned to suspicion and tension. As a telling anecdote — one that illustrates just

how on edge the Carabinieri were that year — Codge, a true gentleman incapable of any provocation, was punched square in the face by a policeman. His only ‘offence’: defending his partner after a Carabinieri had roughly shoved her. But the second piece of bad news was far worse: my friends revealed that the Carabinieri had issued an ultimatum — every camper had to vacate the site by 9.00pm. We had only a few hours to gather our gear, dismantle our tents, and find somewhere else to stay. The reason? According to the police, we were “illegally” occupying Campo Smith. The absurdity was staggering: some campers had been there for several days, yet not a single local official — or even the police themselves — had come by to inform anyone that their stay was forbidden. We later learned, through Italian contacts, that three months earlier the mayor, Mr Gibello, had summoned the late Mario Artusio, the organiser of the rally, to inform him that, exceptionally, ‘Campo Smith’ could not be used that year. Mario had been unable to attend the meeting at the time for personal reasons, which had already upset the local authorities. The Beaulard campsite, 6km from the city centre, on the road to Turin, had been planned as an alternative site. The problem: no participant had been informed. Even worse, there were practically no signs or markers along the route to indicate the way to the Beaulard campsite. Most of the riders ended up camping more or less anywhere, completely unaware that they had unknowingly placed themselves on forbidden ground. I was not the only one who thought that Mario Artusio might have borne a small share of responsibility for this organisational lapse. Sadly, not a single rallyist had been informed — neither by Mario himself nor by representatives of the town council — about the issue with Campo Smith until late Sunday afternoon. Among the French rallyists, some quietly suggested that Mario, with all his enthusiasm and passion, had

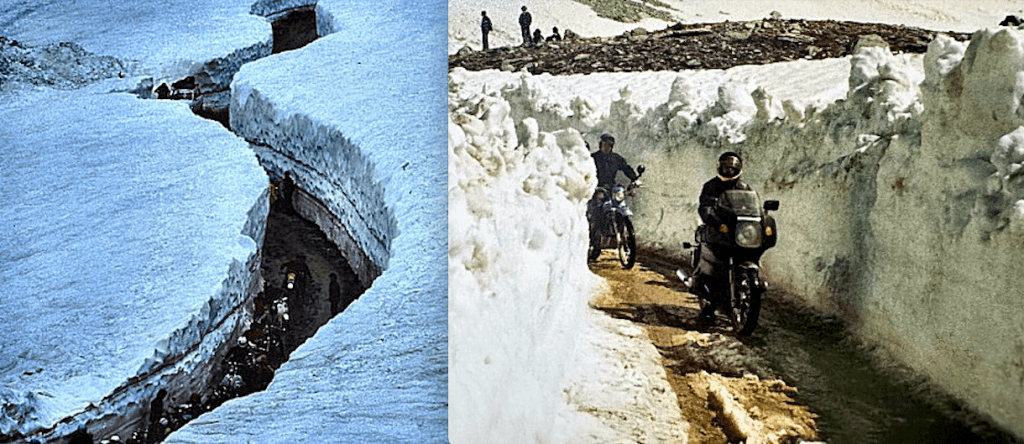

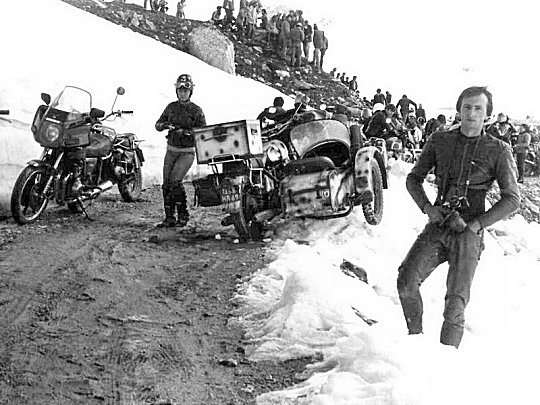

perhaps devoted a little more of his time and energy to organising his three-day Safari — his pride and joy, which gathered a few dozen close friends — than to the rally itself, which each year brought together more than five hundred riders from across Europe. In an article I wrote upon my return, published in La Revue des Gueux d’Route, then the voice of the crème de la crème of French rallyists, I briefly mentioned this unfortunate misunderstanding. I won’t dwell on it again here. Time has softened old frustrations, and I prefer to remain silent, not wishing to cast even a bit of shadow over Mario’s legacy Exasperated by the situation and by the police violence, Mario Viarengo — Lucianna’s husband and the cook at Chez Luigi — decided that enough was enough. Using his connections, he managed to reach the chief of police in Turin by telephone to describe the unbearable situation in Bardonecchia. It is said that Brigadier Cutillo was severely reprimanded by his superiors. It must be true, because by Monday morning, not a single policeman could be seen in the streets. Calm had returned, as if nothing had ever happened. Unfortunately, many friends had already left the town, taking with them the bitter memory of a weekend that should have been nothing but celebration and camaraderie. As for the rally itself, I have vivid memories of the 1980 edition. I particularly remember an English rider who, on Sunday morning, tackled the Sommeiller climb and completed the two days of the Safari on a venerable

Vincent 1000. There were also two magnificent single-cylinder Ariels, relics of another era and admired by all. Year after year, the number of Italian participants, riding off-road motorcycles and arriving solely on Sunday morning, continued to grow. Most came as casual tourists, simply to ride up to the pass and buy the commemorative medal. That year, it cost 3,000 lire, with a sandwich and a drink included. By the registration caravan, what had started as casual fun quickly erupted into a full-blown snowball fight. In the middle of July, resisting the temptation was impossible! Snowballs flew in every direction, and naturally, Hervé ‘Le Grec’ Bully and I were right in the thick of it, joined by a few other ‘Gueux d’Route’. It was pure, unrestrained joy — a scene straight out of a carefree childhood, bursting with laughter and good spirits. After the rain comes the sunshine: the mayor finally confirmed to Mario that there would indeed be a 1981 edition of the Stella Alpina. Good news that finally restored a bit of hope after so much tension and disappointment. Some time later, I received at the editorial office of La Revue des Gueux d’Route, as I did every month — and for two and a half years while I served as editor-in-chief — a batch of new humorous drawings created by Jacques ‘Jacquou’ Lejeune, intended to illustrate the content of the upcoming issues. The name may mean nothing to you, but Jacquou was, at the time, the talented official illustrator of this handmade magazine devoted to motorcycle touring and the rallying world. A gifted storyteller and a caricaturist of genius, overflowing with humour, he brought to life on paper delightful scenes from the rallies of the day and their wonderfully colourful characters. It was only much later that I truly realised his real talent, and how much of a cornerstone he had been within our magazine’s editorial team. He deserves to be thanked

and remembered for it — fully and rightfully so. Among all the drawings, one in particular perfectly captured one of the brutal episodes of the 1980 Stella Alpina. The two characters depicted could have stepped straight out of a Guignol puppet theatre — it was brilliant. The moment I saw it, I knew it had to become a special commemorative Stella Alpina sticker. My plan was to distribute it freely to all the “martyr rallyists” who had been there — and endured stress, moral injury, and the lingering shock of that day. And so it was done. After finalising the logo, I added a title for the sticker based on a subtle play on words: “Stella Alpina Rally” became “C’t’est là qui m’tapa” (meaning “That’s where he hit me”). Since the early 1970s, I had never missed a Stella Alpina gathering. Year after year, I had been a loyal regular, drawn by the camaraderie, the mountains, and the thrill of the rally. But after the events of 1980, a bitter taste lingered. I forced myself to return in 1981, yet the excitement and passion I once felt were gone. The rally no longer held the same magic for me — and I never went back again, leaving behind a chapter that belonged to another time.