1860

A WELCOME ARRIVAL for linoleum, which is easy to clean following essential indoor maintenance.

JEAN-JOSEPH Etienne Lenoir and Pierre-Constant Hugon built engines fuelled by coal gas (available as a by-product of coke ovens). Lenoir’s engines, with Ruhmkorff coil-and-battery ignition, were the first internal combustion engines to win commercial success. Hugon relied on flame ignition. Lenoir set up a company in Paris to develop his engines, and used one to power a three-wheeled carriage which he dubbed the Hippomobile.

FRENCHMAN Gaston Plante invented the rechargeable lead-acid battery.

THEY FOUND oil in the USA. Black gold… Texas tea…

1861

EXPERIMENTS SHOWED that ‘town’ gas gave more power than hydrogen, and that compressing the gas/air mix would give faster, more powerful combustion.

DRAISIENNE MANUFACTURERS Frenchman Pierre Michaux and his sons Ernest and Henri fitted cranks and pedals to the front wheel: Michaux Snr said it was “like turning the handle on grindstone”. They also fitted a ‘spoon’ rear brake operated by a twistgrip. So now we had a lightweight two-wheel rolling chassis with pedals, brakes (well, a brake) and steering, all ready for an engine.

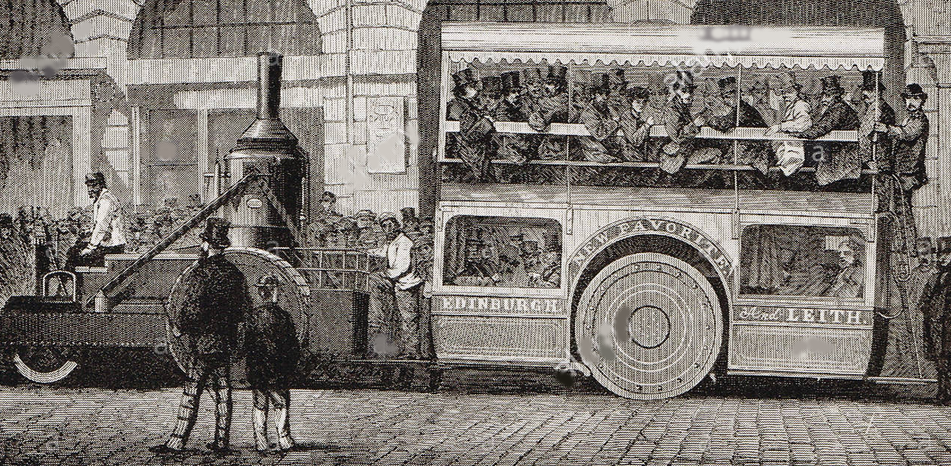

PARLIAMENT REPLACED local tolls with a nationwide fee of £2 for a steamer compared with three bob (15p) for a horsedrawn wagon and introduced a 10mph national speed limit, falling to 5mph in towns and villages. In response to the increasing use of heavy traction engines, the law also restricted the size and weight of engines and imposed limits on axle weights.

BUCKS-BASED RICKETTS bridged the gap between the last of the steam carriages and the first petrol-engined cars. Its little steamers had room for three passengers with a stoker behind the boiler and could cruise at 10mph. The Earl of Caithnes had one and put it to good use; he covered 150 miles in two days in mountainous country from Invernes to Barogell Castle.

WO CARRETT DESIGNED a three-wheeled ‘steam pleasure carriage’ for mill owner George Salt. It boasted a differential and was described by Engineering magazine as “probably the most remarkable locomotive ever made”. Salt was put off by the new speed limit and flogged his trike to a hooligan called Frederick Hodges who dubbed it Fly-by-Knight and clocked up 800 miles, mostly at night. According to Engineering, he “did fly, and no mistake, through the Kentish villages when most honest people were in their beds”. During an eventful 800 miles Salt picked up six speeding summonses in as many weeks; one for doing 30mph—three times the national limit. In a bid to fool the cops he modified Fly-by-Knight to resemble a fire engine and dressed his passengers in uniform, including brass helmets. But he finally accepted defeat and converted it again, to a slow-speed traction engine. Engineering concluded: “But the Fly-by-Night was a good job, and deserved a worthier career.”

1862

FRENCHMAN ALPHONSE de Rochas published a booklet in which he established the four prerequisites for an economical ‘explosion engine’. It amounted to a description of the four-strike cycle 14 years before Dr Otto independently re-invented it, but de Rochas never ventured beyond the theoretical stage.

THE GREAT International Exhibition in London featured a display of Parkesine, a predecessor of celluloid (cellulose nitrate). The plastics industry was born in good time to be of service to motorcyclists.

YARROW & HILDITCH of Islington designed a steam-driven road carriage. TW Cowan of Greenwich built one under licence and, for a short time, ran it as a once-a-week PSV between Greenwich and Bromley. The steamer was shown at the International Exhibition, where it attracted a good deal of attention.

1863

READING IRONWORKS built more than 100 Lenoir gas engines. Lenoir demonstrated a second three-wheeled “experimental road carriage” powered by a 2,543cc engine rated at 1½hp. Fuel was “a light volatile hydrocarbon, vaporised by a surface evaporating device”, which sounds suspiciously like a petrol-fuelled car with a surface carburettor some 20 years before the Germans, or even Butler. It completed an 11km run from Paris to Joinville-le-Pont and back in about three hours. The Hippomobile MkII attracted the attention of Tsar Alexander II so one was sent to Russia, where it promptly vanished.

SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN described tests of an internal combustion vehicle that weighed just 300kg and did 20mph.

1864

POWER FROM Petrol! German inventor Siegfried Marcus, while living in Austria, built a single-cylinder two-stroke engine running on petrol, complete with a spray carburettor and low-tension magneto. He rigged it to drive the rear wheels of a cart and drove it for a couple of hundred yards. He was not happy with his first attempt, dismantled it and built a more sophisticated version which he exhibited atthe Vienna Exhibition. [An extremely honourable mention to the petrolheads who ran the Viennese museum where Siegfried’s automobile was subsequently deposited. When the Nazis came to power they ordered the car and all records of its existence to be destroyed because Siegfried Marcus was Jewish. Marcus was removed from German encyclopedias as the inventor of the modern car, under a directive from the German Ministry for Propaganda during World War II. His name was replaced with the names of Daimler and Benz. The museum staff risked their lives by defying the Nazis’ orders; they bricked up the car and associated paperwork in the cellar. It, and one must hope they, survived the war; it was restored and is still on show.]. Marcus held 131 patents in 16 countries; they includeed “Improvements to relay magnets”, “Device for mixing of fuel with air”, “Improved gas engine”, and “Electrical igniting device for gas engines”.

1865

DESPITE THE CRIPPLING legislation small, reliable steam engines led to a resurgence in steam coaches running a number of scheduled routes. One foolhardy operator boasted “14mph at 3d a mile”, which must have attracted the attention of the cops (don’t forget the national speed limit was 10mph).

THE EARL OF CAITHNESS used a Ricketts steam carriage (see 1858) to tour the Highlands. He reported: “I may state that such a feat as going over the Ord of Caithness has never before been accomplished by steam, as I believe we rose one thousand feet in about five miles. The Ord is one of the largest and steepest hills in Scotland; the turns in the road are very sharp. All this I got over without trouble. There is, I am confident, no difficulty in driving a steam carriage on a common road. It is cheap, and on a level I got as much as nineteen miles an hour.” The nobility clearly had no truck with speed limits.

AS IF THE LAW wasn’t already draconian enough Britain introduced the Locomotives on Highways Act, better known as the Red Flag Act, which imposed a speed limit of 4mph in the country and 2mph in towns. Every roadgoing vehicle required a minimum crew of three, one of whom “shall precede such Locomotive on foot by not less than sixty yards and shall carry a red flag constantly displayed, and shall warn drivers of horses and riders… and shall signal the [locomotive] driver when it is necessary to stop and assist horses, and carriages drawn by horses, passing said locomotive.” The Red Flag Act was designed to regulate the use of heavy traction engines hauling heavy loads but it had a crippling effect on the development of lighter motor vehicles.

1867

THE OTTO-LANGEN engine, designed and manufactured by Nicolaus Otto and Eugene Langen at their factory in Cologne, beat the Lenoir engine to win the Grand Prize at the Paris Exposition of 1867 as the most efficient gas engine.

ROBERT THOMSON (who had patented a pneumatic tyre in 1846) built a number of road steamers shod with solid Indiarubber tyres. They were heavy traction engines, but some were geared high to suit passenger services (though they were also effectively crippled by the red flag rule).

INEVITABLY, WHEN TWO enthusiasts met, they raced—and to hell with the Red Flag Act! The Engineer reported: “On Monday morning, the 26th instant [August], in accordance with previous arrangement, two road steam carriages, one made by Mr Isaac W Boulton, of Ashton-under-Lyne, [and driven by Thomas Boulton] having only one 4¼in cylinder 9in stroke, the other, made by Messrs Daniel Adamson and Co, of Newton Moor, having two cylinders 6in diameter, 10in stroke, started from Ashton-under-Lyne at 4.30am for the show ground at Old Trafford, a distance of over eight miles. The larger engine, made by Messrs Adamson and Co, is a very well-constructed engine, and had a good quarter of a mile start of the smaller machine. The little one, with five passengers upon it, passed the other in the first mile, and kept a good lead of it all the way, arriving at Old Trafford under the hour, having to go steady through Manchester. The engine made by Mr Boulton ran the first four miles in sixteen minutes. The running of both engines is considered very good. On arrival at Old Trafford they tested their turning qualities, and both engines turned complete circles of 27ft diameter, both to right and left, frequently.” Thomas Boulton wrote: “…the distance was over ninety miles in one day without a stoppage except for water. I believe this to be the longest continuous run on record ever accomplished by any road locomotive within twenty-four hours.” However The Engineer reported: “In this Mr Boulton was mistaken. We have stated in a previous article that Hill ran from London to Hastings and back in one day, a distance of 128 miles…Two speeds were obtained by means of two trains of spur gearing between the crank shaft and the counter shaft, the motion of the counter shaft was transmitted to the axle by a pitch chain, the ratios of the gearing were 6½ to 1 and 11 to 1. During the trip recorded above, six persons were carried all the distance, and sometimes there were eight and ten passengers.”

WESTERNERS LIVING IN JAPAN set up the first horsedrawn stagecoach company in Japan. Before long traffic laws were passed. These included bans on drink-driving, nudity and flying kites on the public highway.

1868

Finally… the first (steam)-powered two wheelers! There’s a surprising amount of confusion over who did it first but to keep the story moving along let’s call it a dead heat.

IN FRANCE, between 1867 and 1871 velocipe manufacturer Pierre Michaux teamed up with steam engineer Louis Gillaume Perreaux to develop the velo-a-vapeur. Belts ran from the remarkably compact alcohol-fuelled steam engine to pulleys on each side of the rear wheel (with pedals on the front wheel). The saddle was mounted just over the boiler, it was claimed to do 9mph and there were no brakes.

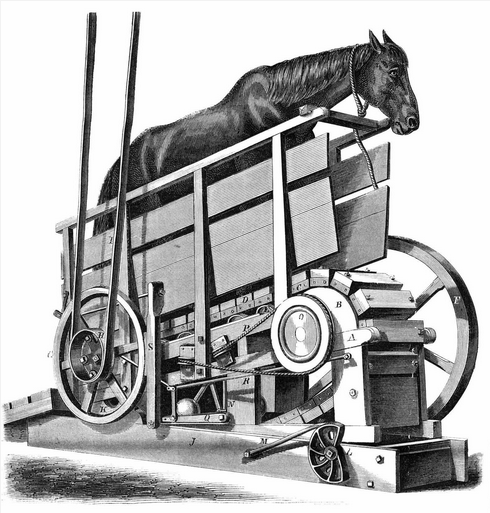

IN THE USA, between 1867 and 1869 Sylvester Roper was touring the fairs and circuses with another steam-powered velocipede. It’s not clear if his first example used an adapted velocipede frame, a home-made iron frame or a hickory wood frame built by showmen Hanlon Brothers, who made and demonstrated boneshakers at fairs. In any case Roper’s steam bike had a rigid, forged iron fork and handlebars that twisted one way to open the throttle and t’other to slow down by applying a spoon brake on the front wheel; drive was by locomotive-style conrods and cranks to the rear wheel. An enthusiast by the name of WW Austin is variously recorded as a rider, promoter and owner of Roper steamers. However, in 1910 the US magazine Motorcycle Illustrated reported: “It was away back in 1868 that a new Englander, WW Austin, of Wintrope, Mass, attached a coal-burning steam engine to his bicycle or, as it was then called, velocipede, and thus produced the first American-built motorcycle.”

NEW YORKER William van Anden fitted pedals to the front wheel of a velocipede a la Michaux; it boasted a free-wheel mechanism and a rear brake controlled by a twistgrip.

NOTTINGHAM BLACKSMITH Thomas Humber built a velocipede based on a picture in a letter about a Parisian machine that was published in the English Mechanic magazine. He incorporated improvements such as (solid) rubber tyres and ball bearings. It was the beginning of a pioneering career in bicycles and motor cycles.

BACK IN BLIGHTY Crossley Bros of Manchester signed a deal to make Otto and Langen gas engines; Crossley developed a number of improvements.

THE WORD “bicycle” was coined for a velocipede shod with (solid) rubber tyres. So we got motorised bicycles, then motor-bicycles and eventually motor cycles rather than motorised velocipedes, motor-velocipedes and motorpedes. And that’s why we have the dismal appellation “biker” rather than the rather jolly “pedder”.

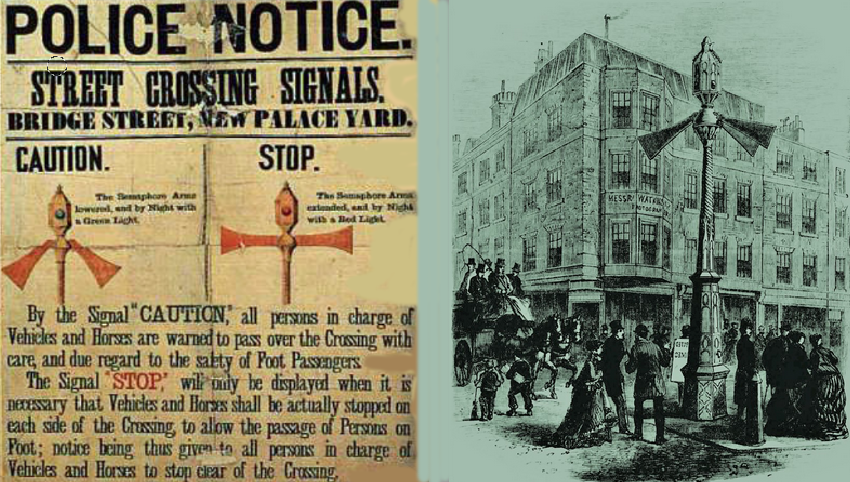

RAILWAY SIGNALLING engineer JP Knight installed the world’s first traffic lights outside the Houses of Parliament to control a chaotic junction (two MPs had been badly injured and a traffic policeman killed at this spot). The 20ft-high red/green gas lights were not bright enough by daytime so semaphore paddles were added to the top. However a few months after the signal was erected a gas leak caused an explosion at the base of the semaphore, injuring the police operator. This, combined with constant breakdowns and the signal’s lack of effect, led to its removal.