ENTREPRENEUR CHARLES Garrard imported 160cc Clement engines which were fitted into bicycle frames by James Norton and marketed as Clement-Garrards. Before long the first Norton motorcycles appeared, also powered by Clement engines and marketed as ‘Energettes’. Adolphe Clement was a bicycle manufacturer who had been working on developing engines since 1897. He also produced pneumatic tyres and owned the French Dunlop patents.

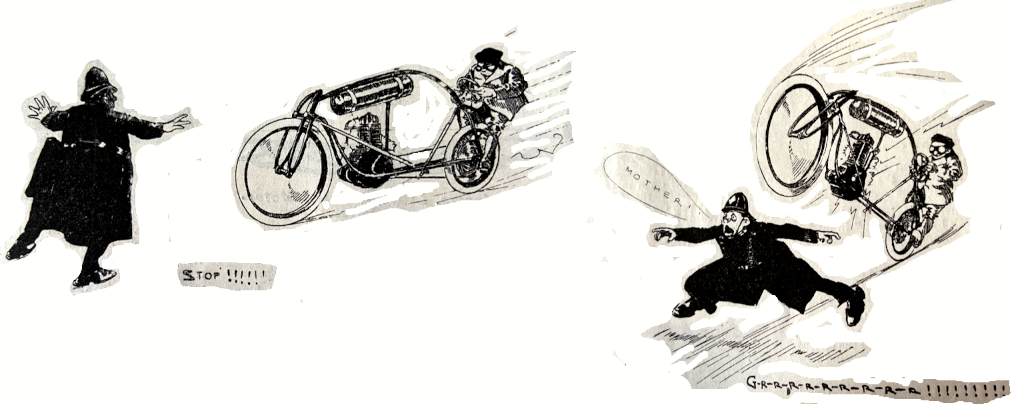

THE COURTS WERE beginning to deal with motoring offences. In Somerset one Alfred Nipper of Weston Super Mare was hauled before the beak summons for the way he was riding his 1898 Werner: “Then being the driver of a certain carriage (to wit a motorcycle) on a certain highway there situate called Bristol Road unlawfully did ride the same furiously thereon so as then to endanger the lives and limbs of passengers on the said highway.” He was fined 7/6d; worth about £40 today.

JAMES, WHICH HAD been making bicycles since 1872, fitted FN engines; Brown Bros branched out from parts and accessories into complete bikes marketed under the Vindec banner; the first Triumphs and the first Ariels both used 2¼hp Minervas. More than 75 marques on both sides of the Channel relied on Minerva engines, including Matchless and Royal Enfield.

MOTOR CYCLING WAS a global obsession—the first bike arrived in Tasmania.

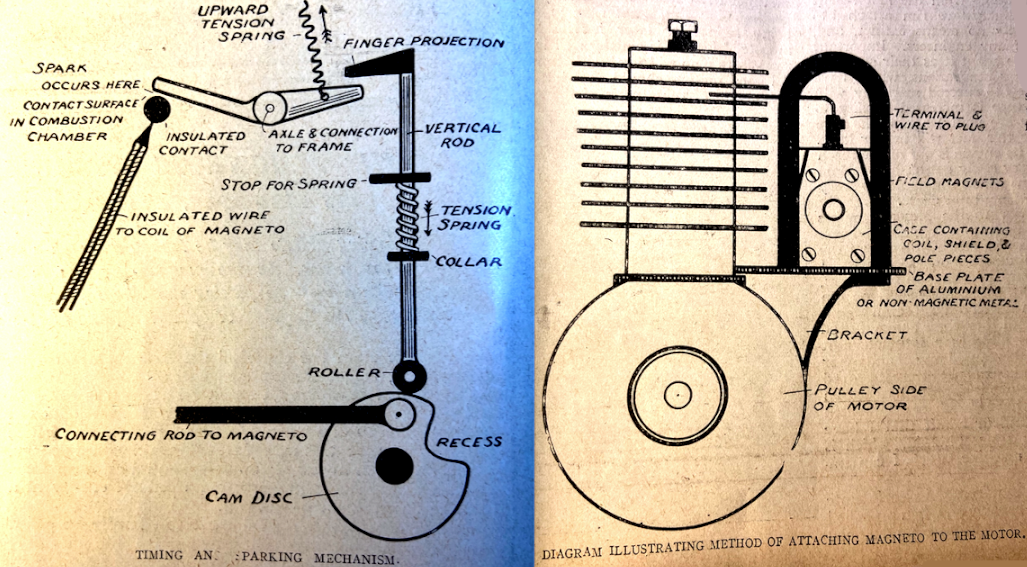

BOSCH LAUNCHED a high-voltage magneto and spark plug. The mag included a condenser which enhanced its reliability. Other technical developments included a water-cooled engine from US manufacturer Steffey; a V-twin engine from Zedel which was used on (French) Griffons; and a practicable drum brake, invented by Louis Renault (a less-sophisticated version had been used by Maybach the previous year).

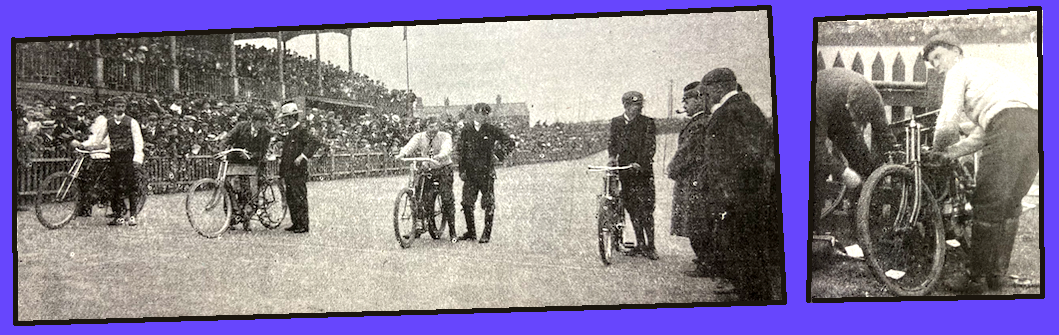

OTHER NEW MARQUES included Montgomery, Brough (WE, George’s dad), Bradbury (with a 1¾hp Minerva clip-on engine, from Oldham, Lancs), Simplex (in the Netherlands), Merkel, Metz and Yale (USA) and Victoria (Scotland) – not to be confused with the German Victoria, which was designed by the memorably named Max Frankenburger. In the US Marsh built a 6hp racer that was said to do 60mph.

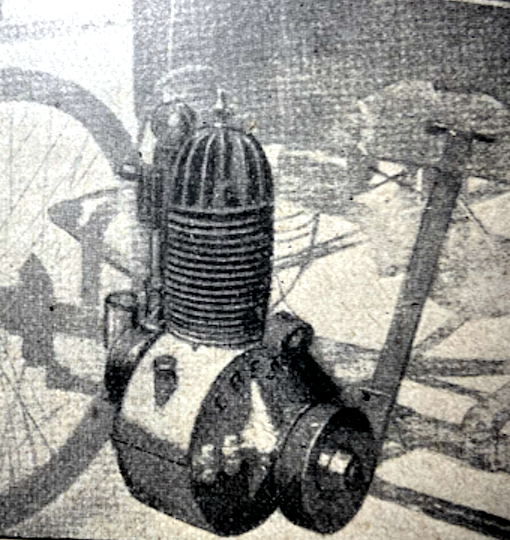

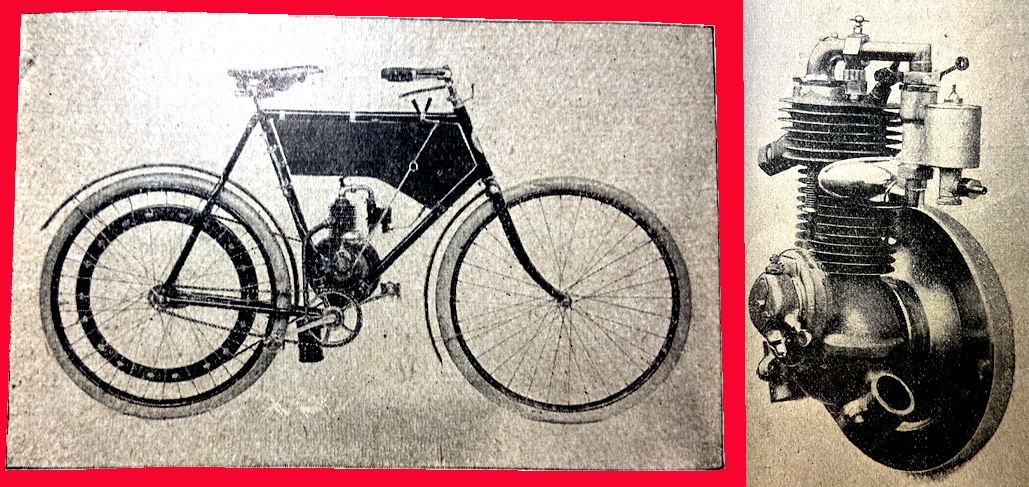

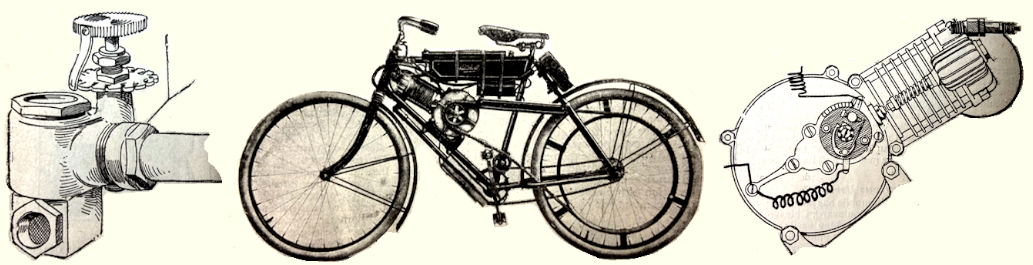

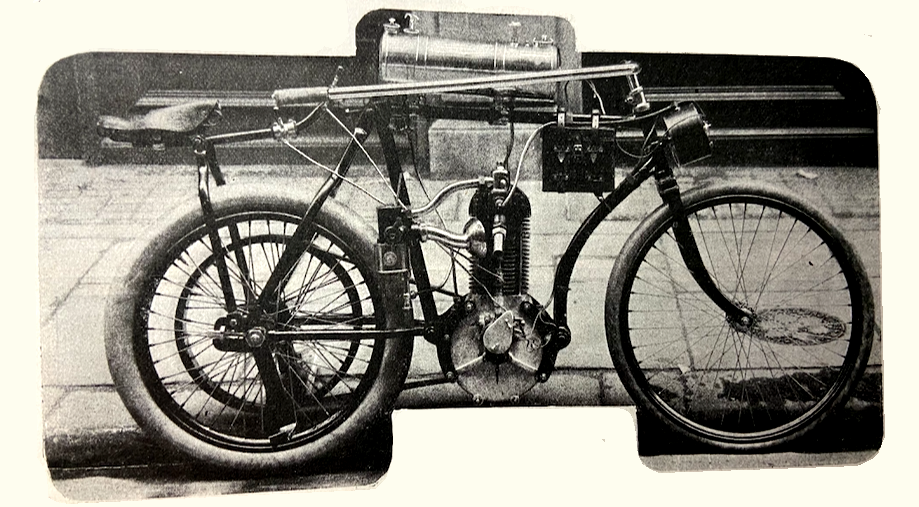

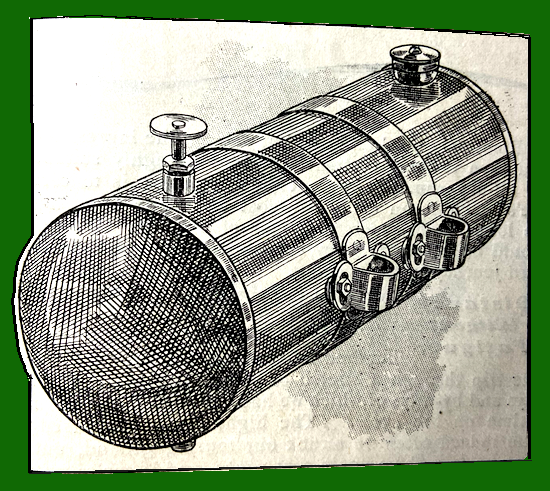

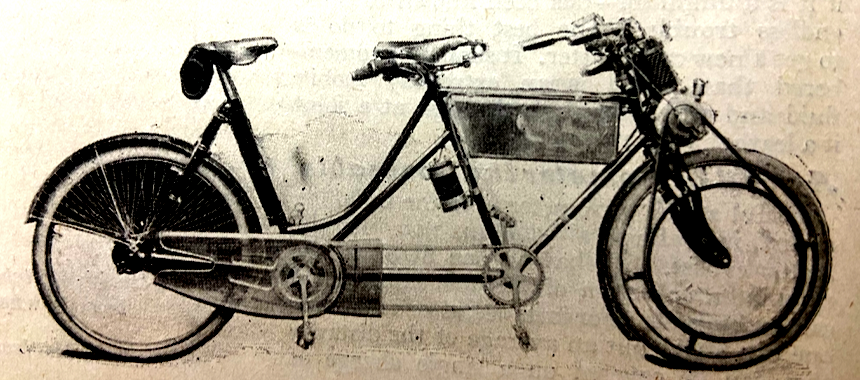

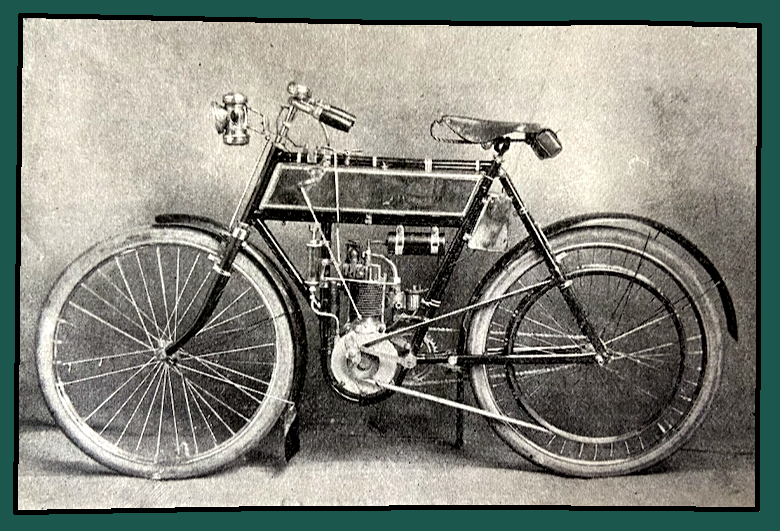

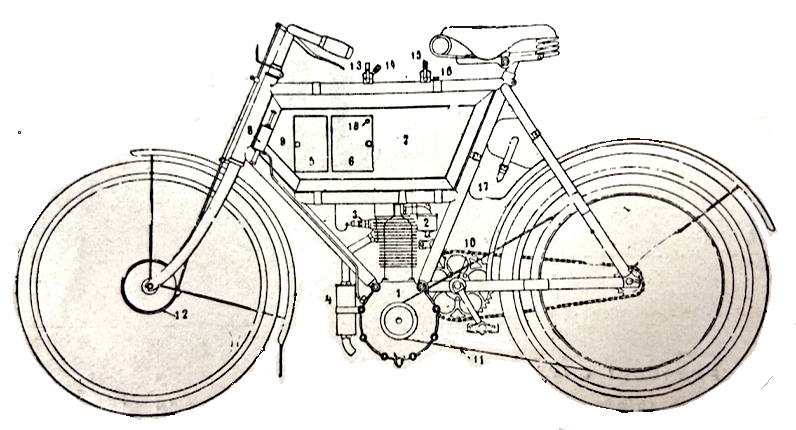

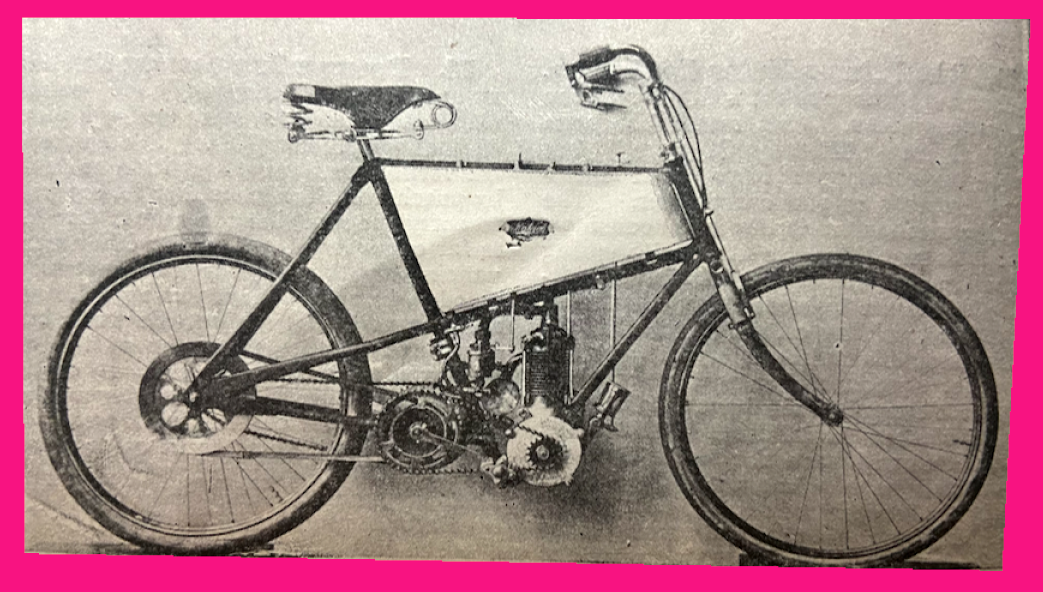

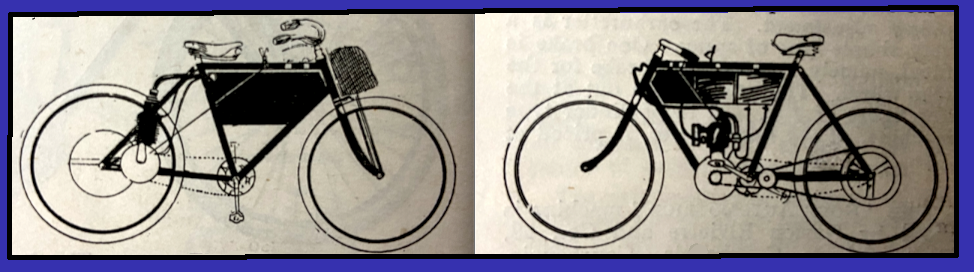

“THE BORD MOTOR-BICYCLE is a machine that is being put upon the market at a very low figure, and from what we could gather after a brief inspection and run, it is remarkably good value. The motor develops 1½hp, and is made be that reputed firm the Fabriques Nationale, Belgium. It is fitted in a vertical position in the large panel of the frame, and drives by a round belt on to the back wheel pulley. An outside fly wheel and De Dion contact breaker are fitted. The coil and accumulator—which, by the way, is a new and highly efficient French make—are carried in a neat case hung from the top tube. The petrol supply is kept in a cylindrical tank mounted on the handlebar, and feeds the motor through an indiarubber tube to the mixing chamber combined in the inlet valve. Regulation is effected by a needle valve on the petrol supply and the spark advance lever. There seems to be plenty of power in the motor, and the total weight is 60lb.”

IF MATCHLESS (which was now fitted with a 2¾hp MMC engine) was making Woolwich famous, the De Dion-engined BAT would do the same for Penge. BAT’s Model No 1 used a 2¾hp De Dion. Did BAT stand for ‘best after test’? That was the firm’s slogan but, more prosaically, the founder was Samuel Batson.

HAVING FINALLY put the Holden into production, Harry Lawson’s Motor Traction Co launched an optimistic ad campaign claiming: “1902 will be a motor bicycle year”. It was indeed, but not theirs. Few pioneers wanted the heavyweight obsolete fours and production ceased.

DEBUT OF THE Stanley Steamer car; two years later the Stanley Rocket set a world record of 128mph.

ERNEST H ARNOTT, Captain of the MCC, was the first rider to complete a timed Land’s End-John o’ Groats run, in 65hr 45min, on a 2hp Werner. Following the run he noted: “I do not think that anyone who has not been over this route can have any idea of the difficulties of the road. I certainly expected to find the ride less trying than it proved. The journey includes, I suppose, some of the steepest hills and the roughest roads in the two countries traversed. It is a certainty that no more severe or practical test could be undergone, and the new type Werner has added one more to the long list of honours which it has already secured.” His epic ride went a long way towards ending the perception that the motor cycle was a toy; Motor Cycling said: “We have pleasure in devoting considerable space to Mr Arnott’s interesting account of his excellent, motor ride, believing that performances of this kind accomplished on standard machines as offered to the public are of the greatest value showing as they do the capabilities of the motor-bicycle for practical purposes.”

“LAND’S END TO JOHN O’ GROAT’S inside three days—It is almost impossible for anyone who has not been over the course to really appreciate all that is conveyed in the sentence that stands at the head of this paragraph. Eight hundred and eighty-eight miles at top speed; opportunities for rest very few; for sleep, very little; hills, numerous, long and steep rains at all sorts of times in the Highlands; roads as bad as they well could be in many places; the worry and the anxiety of the trial—all these things are enough to try the hardiest, to quench the ambitions of the most strenuous of record breakers. They have been the undoing of many a rider in the past, and, so far, few motor vehicles indeed have essayed the journey, and (fewer—greatly fewer—is the number which have succeeded in travelling from End to End. GP Mills [a champion pedal cyclist] was the most wonderful man on this record up to the time when he practically put an end to all attempts by going through in 3 days 5hr 49min. A marvellous ride that, simply marvellous; and on that last seemingly interminable stretch, the greatest battle was not with time, nor with roads, nor with weather, but with sleep. The motor vehicle brings new conditions with it.. The physical fatigue is, maybe, less, but brain fag is greater, and there is not the action of pedalling to help the rider in his fight with the desire to sleep. Of the motorists who have been over this route, none had succeeded in equalling GP Mills’s time until the beginning of last week, when JW Stocks, on an 8hp De Dion Bouton car, and Ernest H Arnott, on a 1¾hp Werner motor-bicycle started from Land’s End in the early hours of Sunday morning. Stocks accomplished the distance in 2 days 14hr 25min, and Arnott in 2 days 17hr 45min. Stocks had a few hours’ sleep on the first evening, but thereafter he went right through without further rest for over 38 hours. Arnott on the other hand, snatched a few hours’ sleep; but as 3am was the accepted hour for starting each day, the rest was by no means adequate. From the De Dion car and from JW Stocks a successful performance might have been expected, because we have now reached that stage of development in which confidence in the machine and mechanism has been established. But even the most sanguine would consider that, for a motor-cycle and a motorcyclist, the tasks—over those fearfully rough roads and through those pitiless rains—would be almost too much. All the more, then, to the credit of EH Arnott and to his Werner for accomplishing it. The excellent impression created by this machine in the Paris-Vienna race is confirmed in the Land’s End to John-o,Groat’s ride. A performance such as this is, to our mind, worth fifty of a fast five miles on a racing track by a freak machine. It proves something; it teaches us that the motorcycle is not a toy; that it is a really sound practical vehicle, full of capacity and full of possibilities. It also proves this, that although the Holbeins, the Mills, an the Shorlands of one decade have left the sphere of cycle records, the next decade has its Bucquets and its Arnotts, and their influence for good, especially upon a sport and industry so young as is motor cycling, is undoubted.” For a comprehensive review of the End-to-End, six-day and coastal record record rides, including Arnott’s account of his run, check out the 1911 Features section.

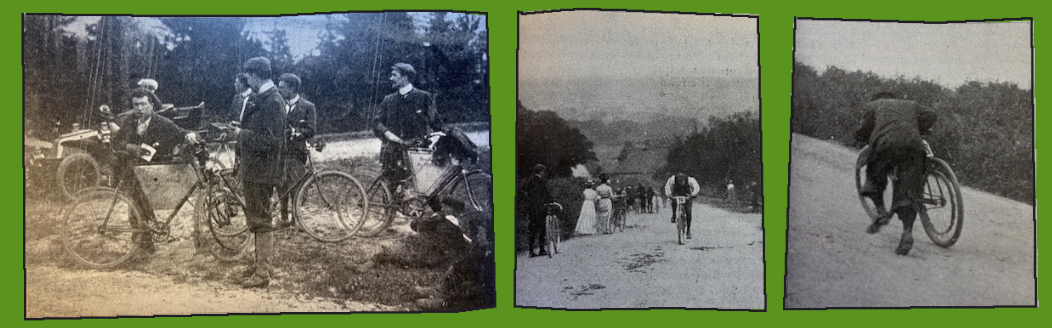

THE MCC ARRANGED a weekend run from London to Brighton and extended an invitation to all motor cyclists to join them. Only about a dozen bikes made the trek but this event deserves its footnote in history as the first club run.

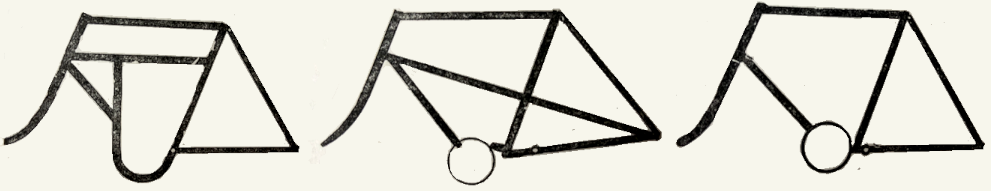

THE ADOPTION OF A really simple and efficient two-speed gear to the motor-bicycle Is undoubtedly a much to be desired feature, and at the present time a good deal of experimenting is being done in this direction…The power developed by small internal combustion engines is largely determined by the rate of speed at which they run, and below a certain point the power is by no means directly proportionate to the speed. Now the problem arises as to whether the weight of the motor-bicycle must be increased as a result of fitting larger motors to get the power for hills, or retain the small dimensioned motor of 1½hp and fit a two-speed gear. The average rider of a 1½hp motor. bicycle is, as a rule, satisfied with its running on moderate roads, but now and again hills are met with that even hard pedalling will not suffice to get the machine up; this is simply because the speed of the motor drops below the critical point, at which point the power falls off rapidly. This is where the two-speed gear will score, viz, by allowing the motor itself to run at constant speed and always develop its maximum power.”

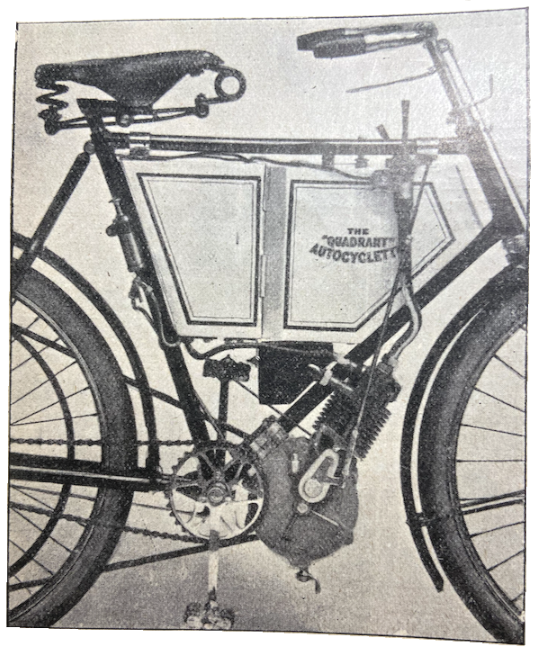

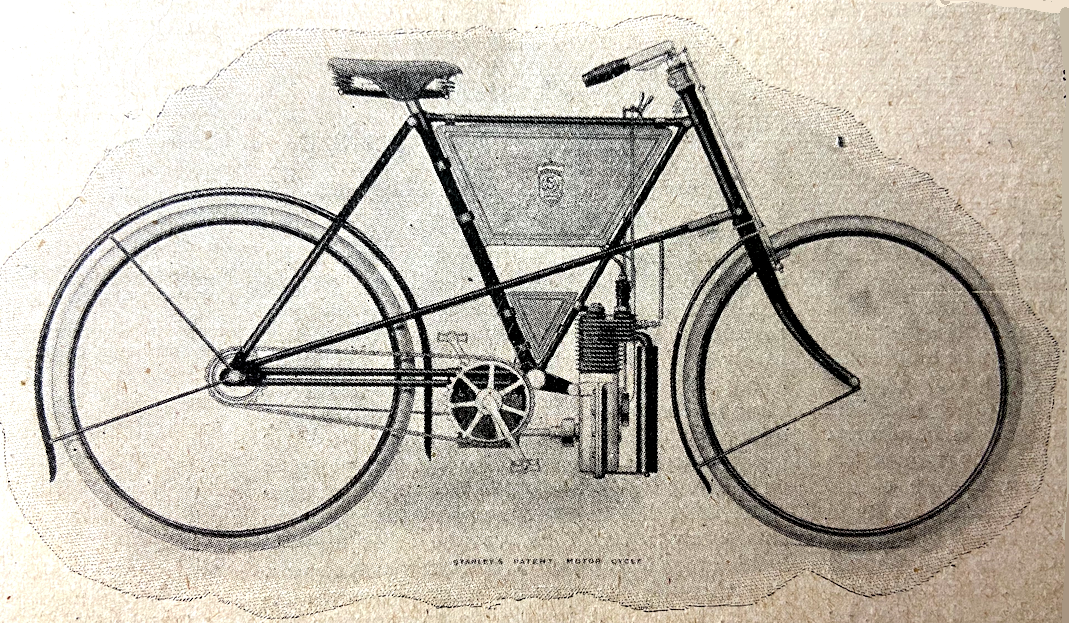

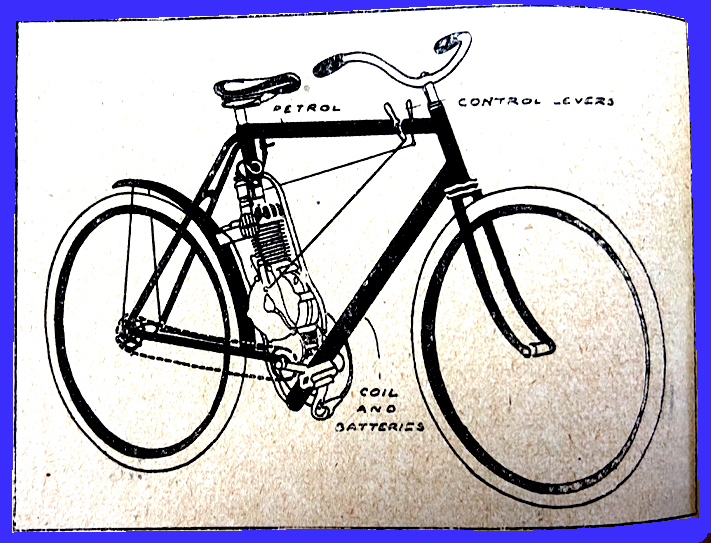

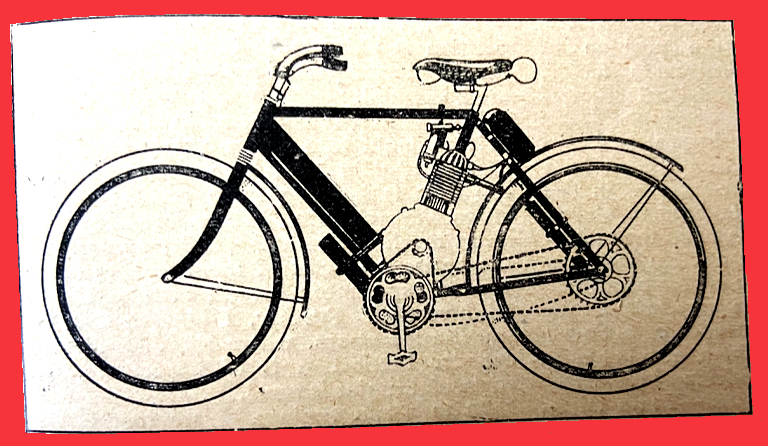

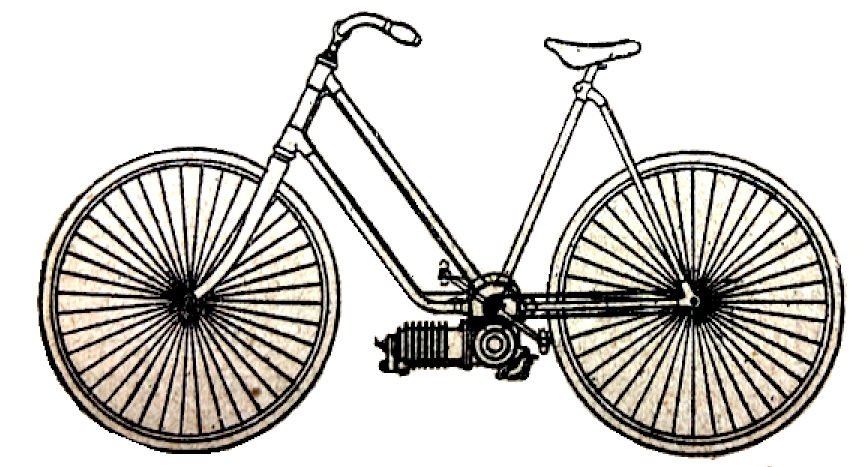

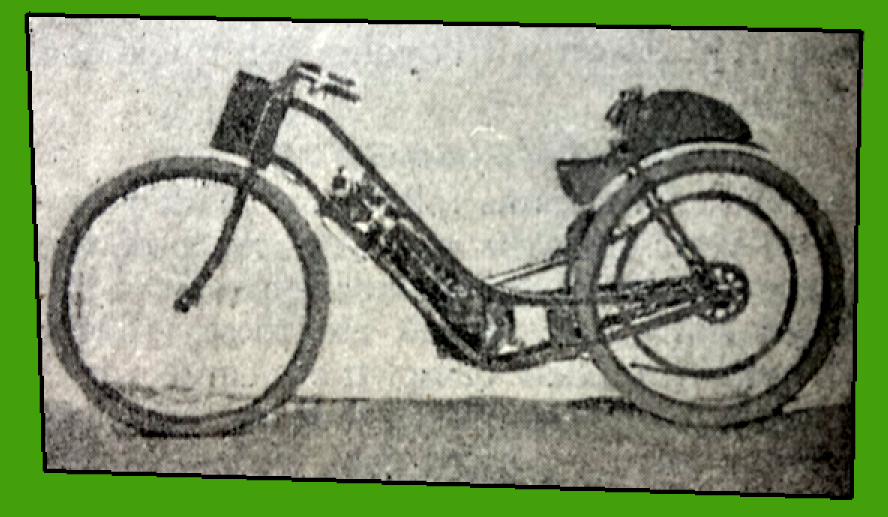

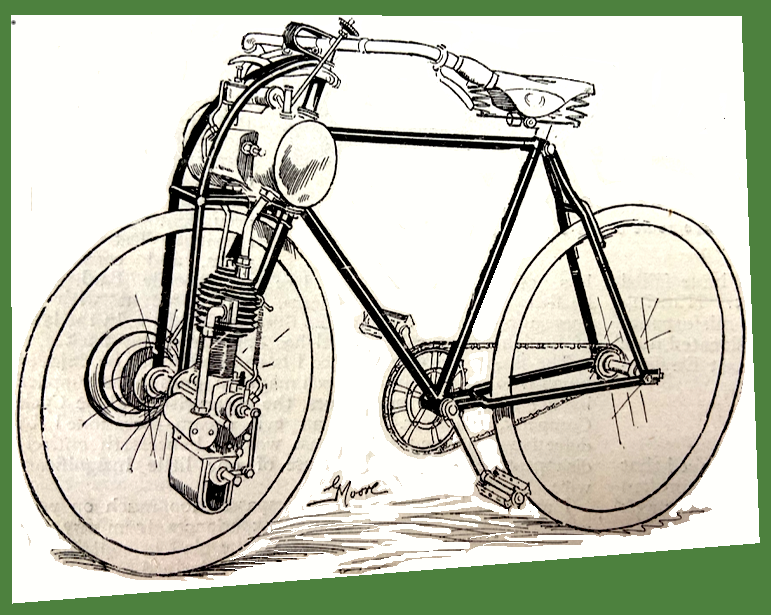

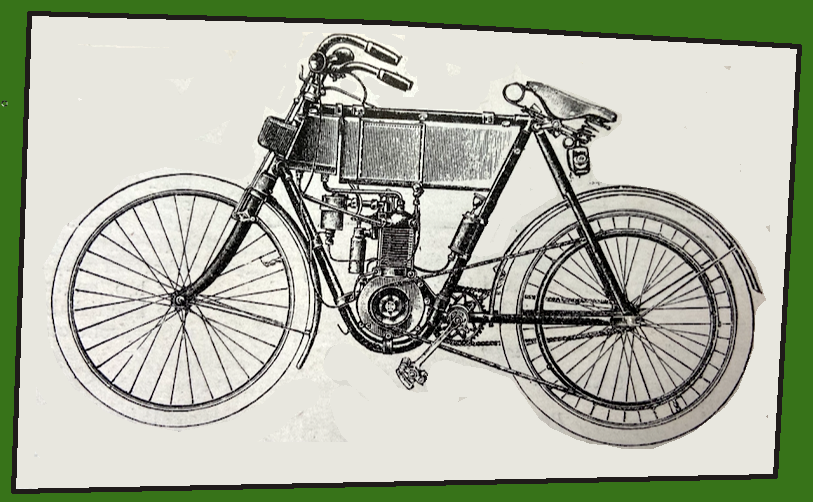

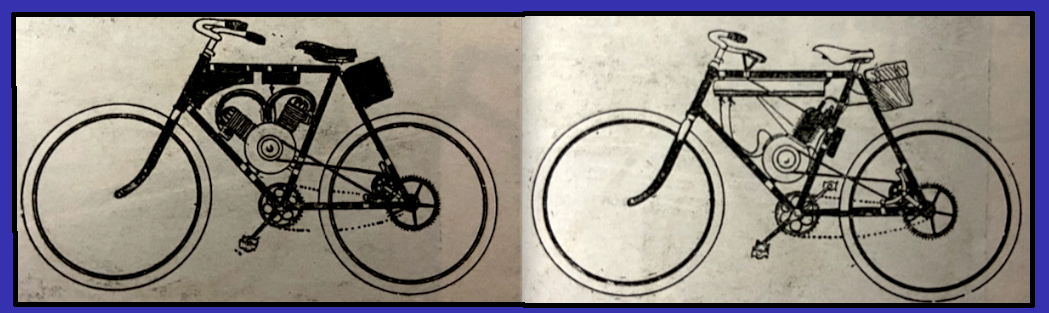

CLARENDON, JAMES, Quadrant, Bradbury, Rex, New Hudson and Phoenix were among British manufacturers to follow the New Werner’s lead by mounting their engines vertically at the bottom of the frame. Ditto Continentals such as Peugeot, FN and NSU. Light Motors produced a lightweight clip-on engine.

TEMPLE PRESS launched Motor Cycling and Motoring magazine (the first issue, produced by the staff of Cycling, was dated 12 February). After a few months the new magazine reduced its motor cycling content to concentrate on cars but Motor Cycling would return in 1909.

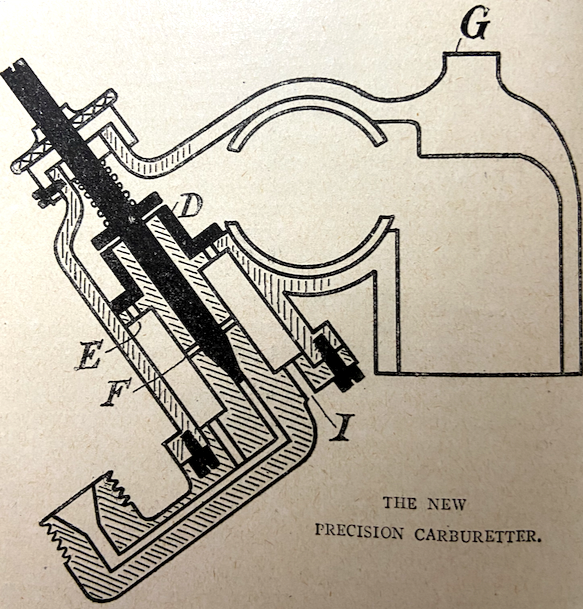

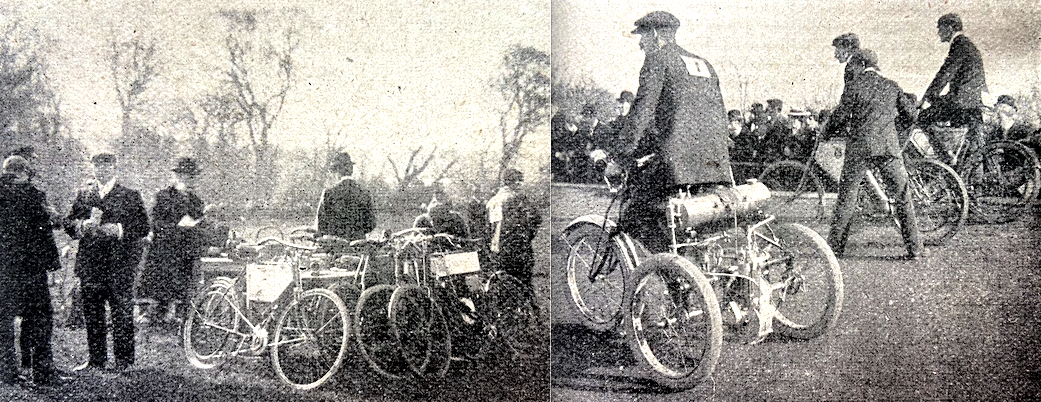

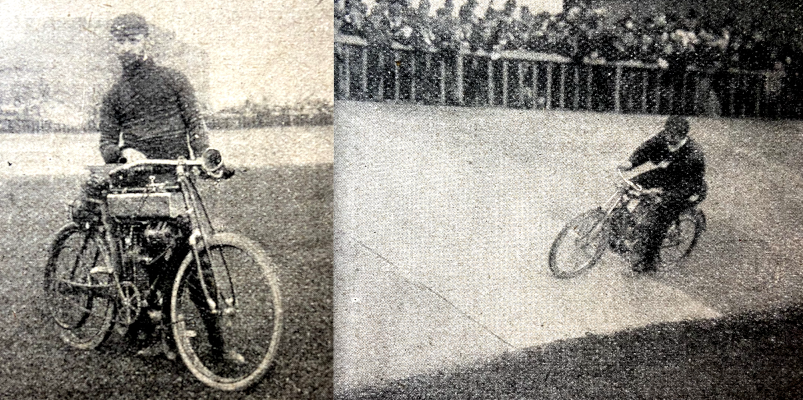

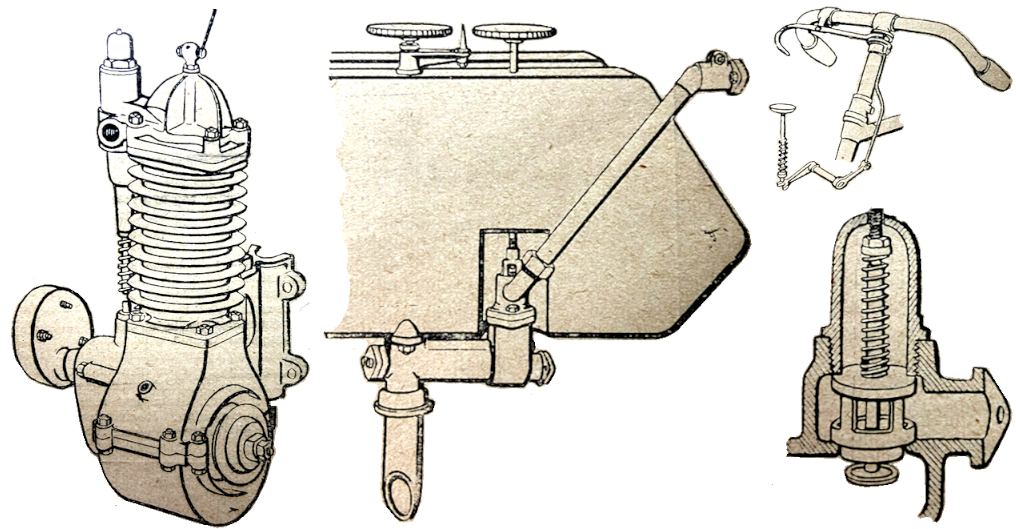

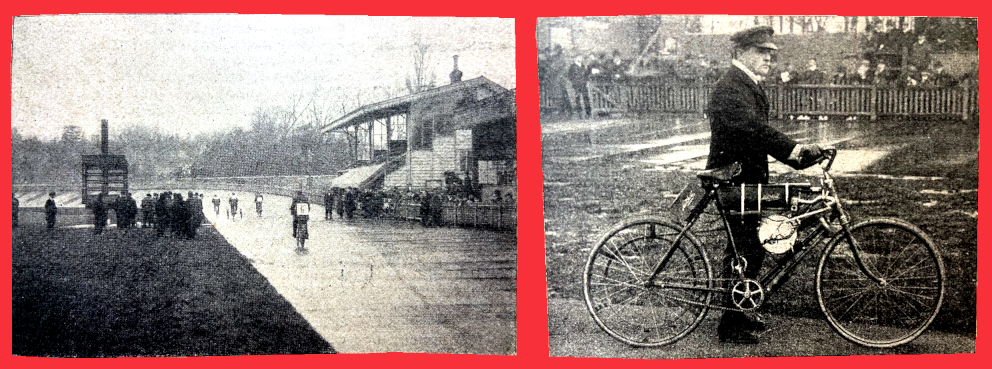

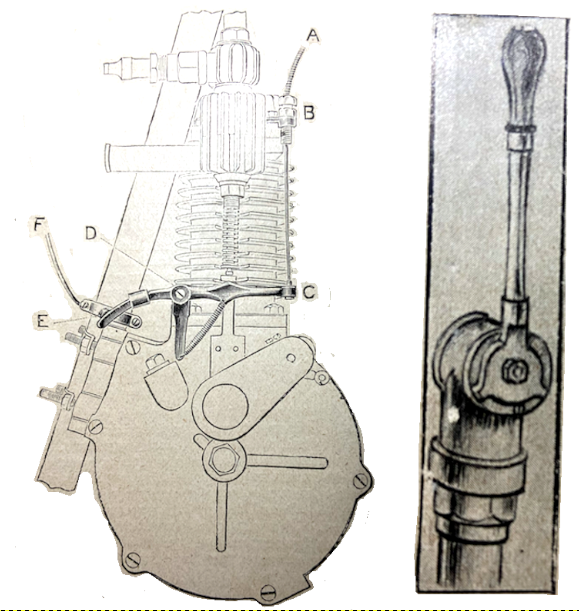

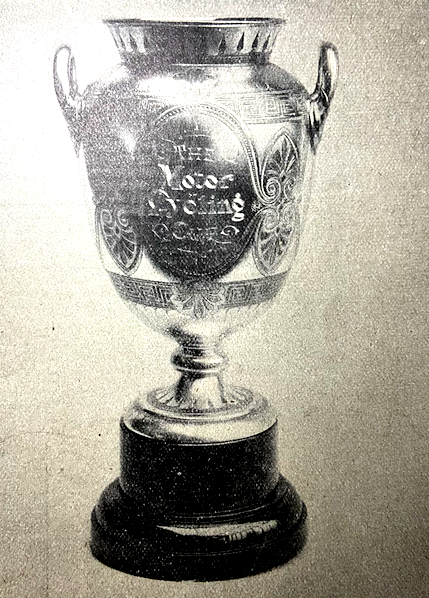

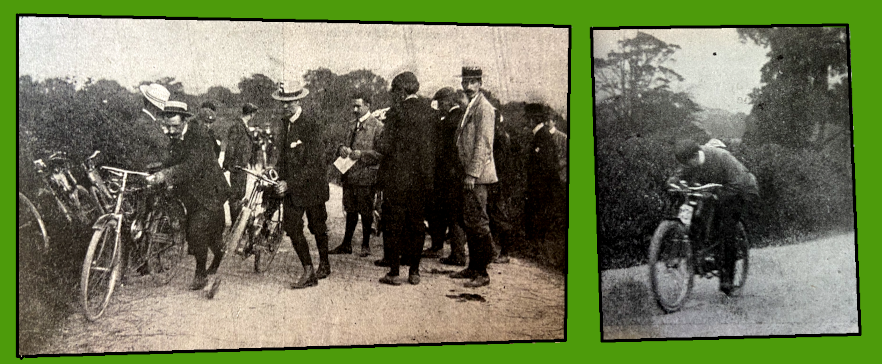

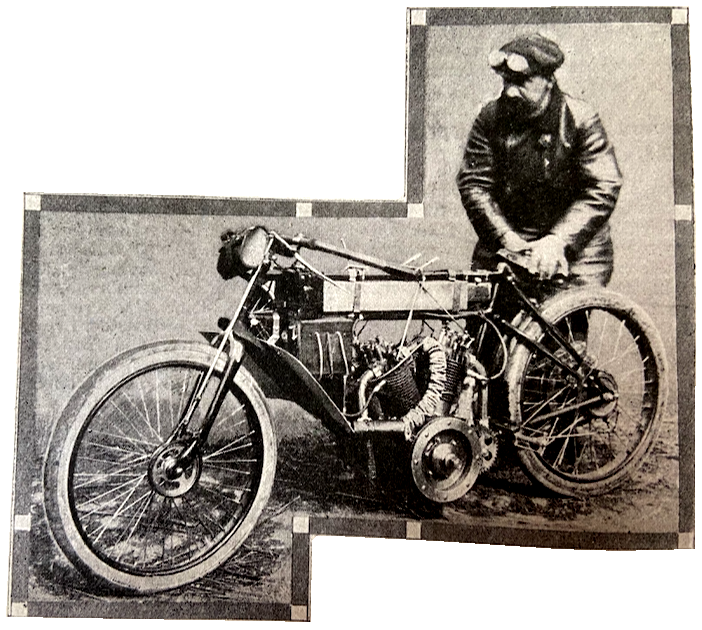

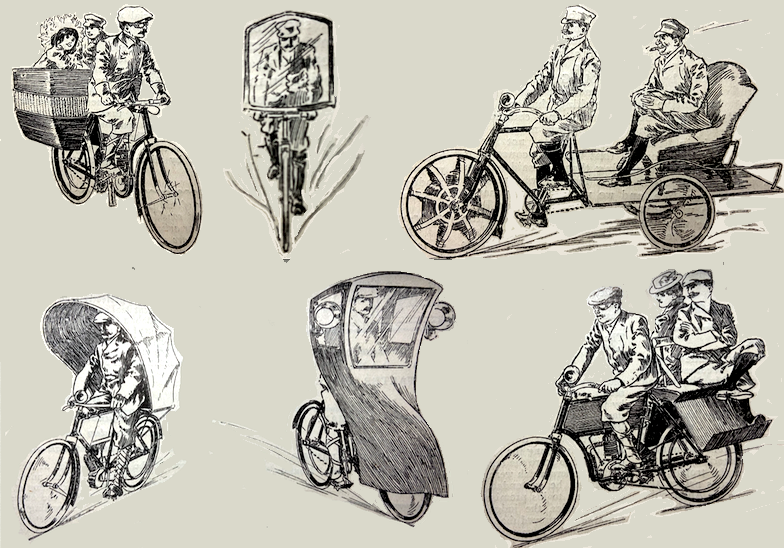

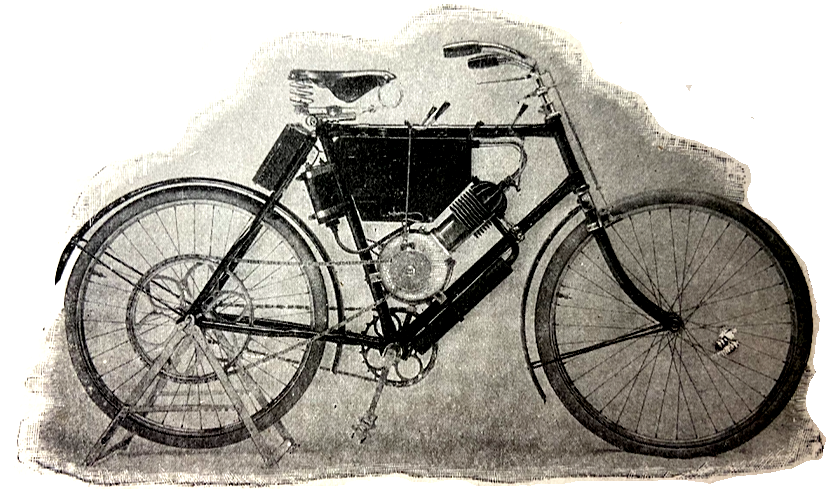

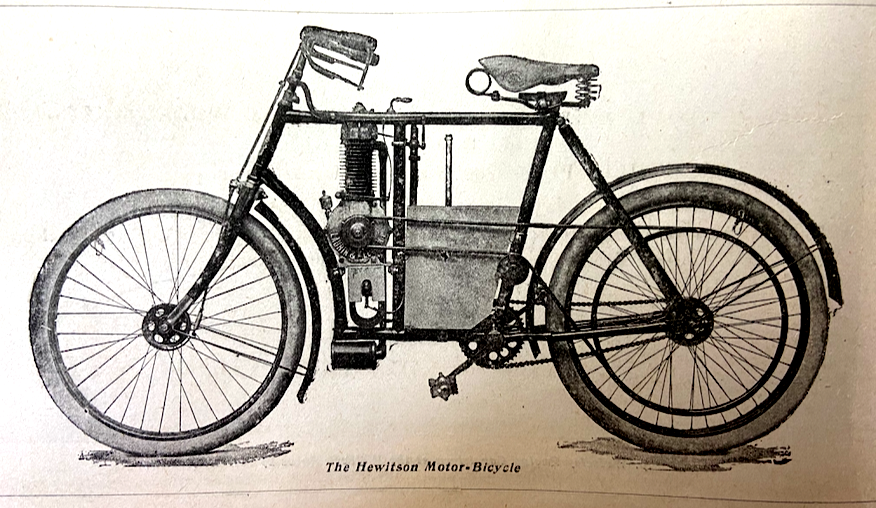

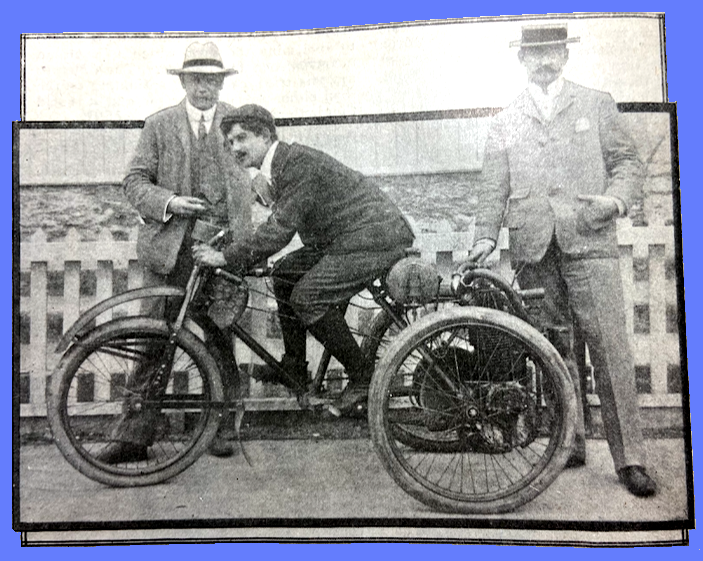

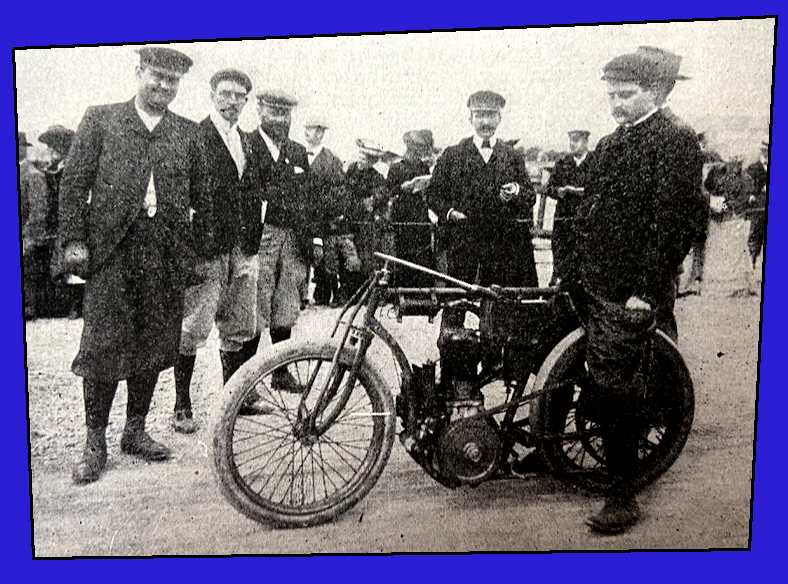

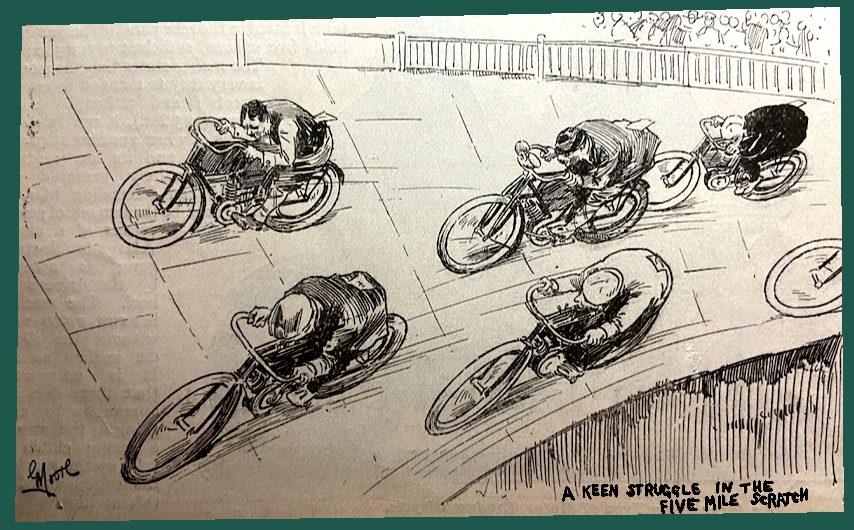

Here are a few images from the launch issue of the world’s first motor cycle magazine.

The foregoing excerpts were culled from the 50th anniversary issue of the Green ‘Un (discovered by chance at a Kempton Park autojumble). Since then, as you might have read in the site’s blog, I’ve invested my children’s inheritance in the four volumes of Motor Cycling covering 1902-4 (Sorry Harry, sorry Katy). As I work through the volumes I’ll be moving these pics and placing them in context but will no doubt be anomolies—as always, this timeline is a work in progress. Let’s get started, with the original masthead and the first words of the first issue of the first volume…

“IN DISCUSSING THE MANY DETAILS of a new paper the primary point is, or should be, a serious and lengthy consideration of the problem—Is it wanted? This all important question has received the most careful attention of those who are responsible for the production of No 1 of Motor Cycling, and we are firmly convinced that this, the first attempt at a journal specially devoted to motor cycling, is fully warranted by present conditions and. future prospects. To ensure success for a new paper, there must be good reasons for starting it. The reasons for starting Motor Cycling are many. In the first place, great interest is being taken in the new movement by the public. This is proved by the fact that the readers of Cycling placed the motor bicycle at the head of a list of desirable innovations and gave it a good majority. At the two bicycle shows, the interest in motor bicycles thoroughly justified the voice of Cycling’s readers, and since the shows the public interest in motor bicycles has been daily increasing. It is not necessary to go far in search of a reason for this interest. In the motor bicycle we have the cheapest. handiest, lightest and simplest power-propelled vehicle that has yet been introduced. The majority of cyclists have followed the motor movement from its inception, and wherever motor events take place one will always find present the inevitable little crowd of interested cyclists. To many thousands of riders of cycles the luxurious motor car is a forbidden pleasure on account of its prime cost, and the expense of maintenance. But in the motor bicycle the cyclist has a vehicle that particularly appeals to his fancy, and his pocket. It is a machine he can ride and drive at once; it is a vehicle he can keep in the house like an ordinary safety bicycle, and he can always get home on it should anything by chance go wrong. In a word, the motor bicycle will introduce the pleasures of moting to thousands of cyclists who would never otherwise be able to participate in the new pastime; and it is safe to assume that at the present time some thousands of riders of ordinary bicycles will he interested in the development of the motor bicycle. With all these facts in mind it was not difficult to foresee a very considerable development in the motor cycle and in motor cycling, and we were brought face to face with a full realisation of the fact that we could not possibly devote the necessary space in Cycling in which to deal adequately with such an important and such an expansive subject as motor cycling, without a considerable, and, in our opinion, an unjustifiable encroachment upon space that should be rightfully devoted to other purposes in the interests of the cyclist. A full consideration of all these points decided as that if the subject was worth dealing with at al1, it was worth dealing with thoroughly. If this movement is capable of such rapid development as we firmly believe it to be, some steps should be immediately taken to provide for its its immediate and future expansion, and we unhesitatingly decided to provide such means at the outset by launching this journal, the principal objects of which will be: To closely watch the interests of motor cyclists; To encourage motor cycling as a pastime; To be first out with illustrated motor cycling news; To describe and boldly illustrate the latest new inventions in connection with the motor cycle; To further the motor cycling movement by every means in our power; To advance the interests of the motor cycling industry. To these objects we shall devote ourselves assiduously, and with the co-operation of our readers, which we cordially solicit, we hope to make Motor Cycling thoroughly useful, entertaining and consistently interesting. There is one point we must particularly emphasise—that Motor Cycling will be absolutely unfettered in its opinion and in its policy. We shall not hesitate to speak out when speaking out is necessary in the interests of sport, pastime, or trade, anti the cause of the motor cyclist will always be our first consideration. Six short weeks ago the first announcement concerning this publication made its appearance. It has been a busy time, but there were several reasons why briskness was necessary, not the least of which was the impending opening of the Crystal Palace Exhibition and the importance of dealing with the exhibits in an adequate manner in the early issues of a journal devoted specially to the new pastime. Motor Cycling now awaits the result of our readers’ careful scrutiny and candid criticism. Is its existence justified? At the outset we stated that the subject of motor cycling could not be adequately dealt with except by means of a special publication, and we venture to assert that the matter appearing in this issue is in itself proof of our assertion; indeed, but our difficulty has not been one of finding sufficient ‘copy’, but of finding sufficient room. Even at this early stage our pigeon-holes are well occupied by a great variety of striking articles, for which it is quite impossible to find space in this issue. It has been our endeavour to obtain the views and opinions of not only the best known authorities upon our particular subject, but also to bring to the front talent which we felt confident was hiding its light under a bushel and which would be fresh and welcome to us all. It is our intention to give every encouragement to expressions of opinion from every possible quarter, for. dealing as we are with a subject comparatively strange to all, we feel that a common expression of views and ideas will be the quickest and soundest manner in which the movement can be advanced. The motor cycle is in its infancy, but we arc sure that when the cycle mechanics and amateur enthusiasts of this country settle down to the subject, improvements will be rapid and new ideas plentiful. We think it will be admitted that our advertisements give ample evidence that such an industry is already established; had there been more time at our disposal this evidence would have bean considerably stronger, but when we state that no single announcement has been received upon any other terms than those of strict business character, the amount of work involved will perhaps be appreciated. We wish to state plainly that the existence of this publication will not be dependent upon charitable or even friendly support in its advertisement department, but, like its predecessor, will rely entirety upon its merits, and the prospect of being able to bring sound business results to those whom it will always be a pleasure call our clients, but with whom business relationship will be one of mutual advantage. We are now content to leave the diagnosis of our case in the hands of our friends many of whom have already rendered us valuable assistance, and to whom we accord our heartiest thanks.”

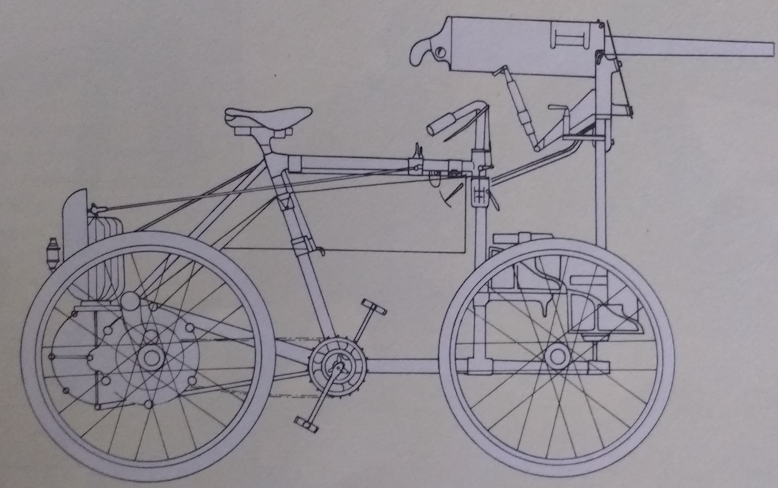

The first feature in that first issue was the first a three-part review of motor cycle evolution, including “some motor bicycle history which goes to show that motor bicycles were engaging the attention of inventors so far back as 1781…” You’ll find Daimler’s 1885 Einspur and the 1895 Hildebrand & Wolflmuller which already appear in this timelines, as well as many forgotten pioneers with external and internal-combustion power. It was introduced as “some motor cycle history, and some personal experiences—by Anthony Westlake”.You really couldn’t ask for a better introduction to the state of the motor cycling nation. Over to you, Tony.

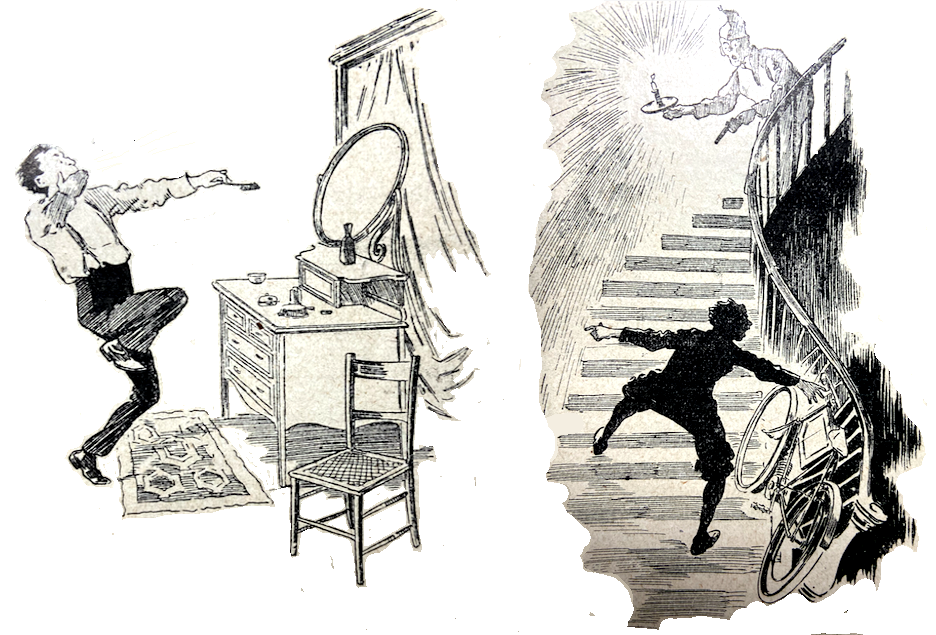

“IN GIVING SOME EXPERIENCES and descriptions of many motor cycles, my mind is inadvertently led back to reflect upon numerous men who essayed, even in bygone centuries, to make mechanical locomotion a practical thing; and now that this is with us in all its present force, the somewhat crude and cumbersome efforts of those anachronic geniuses have a strange pathos about them. To me they appeal strongly as my own early mechanical dreams were all in this direction, and I made many early efforts to realise them, which circumstance brings me to my first experience in motor matters, due to a fractured back hub on my safety in 1891. A friendly engineer on a traction engine entered into consultation, and finally volunteered a lift to within a quarter of a mile of my destination. The acquaintance afterwards

ripened, and my progression in the art of driving increased until one day I managed with some adroitness to place the machine partly on its side in a ditch. I will draw a veil over the sequel, for with a maximum speed of nearly five miles an hour, and the now nearly-universal wheel steering, it was a wild and thrilling time; and so now, with middle age coming upon me, and my 1902 racer (with a steady plod of fifty miles or so) in view, I settle down to a quiet and respectable view of life. But allons a nos moutons, or perhaps more correctly a nos velos. My personal interest in motor power applied to bicycles was of even earlier birth At the French Exhibition of 1878 there was exhibited a steam motor bicycle, the invention of a Swiss mechanic, whose name I quite forget and which I have been unable, for the present, to obtain. I give a rough drawing (No 2) from memory of this machine. The wheels were of hickory, with iron tyres, which had been superseded by the suspension wire-wheel in England some years before the date of which I speak. I have no knowledge of any records made on this machine, the boiler, according to my impression, being too small for any ride longer than 100 yards. In appearance it suggested a wild caricature of the Holden motor bicycle, which most of us I think know by sight. The engine drove direct on to a pair of cranks attached to a small back wheel above which the boiler was placed, the rider sitting in the ordinary position common to the bicycles of those days. But a century previous

to this masterpiece (1781), Murdock, Watts’ foreman, had designed and constructed a small road carriage, or rather tricycle. See footnote. Small as the model was (I append sketch and dimensions), it proved however, from the mechanical point of view highly successful, for on one of its trials, made in the evening, on the road in front of Murdock’s cottage, it literally ran away from its inventor, and charged down the street at twelve miles an hour, scattering fire cinders, steam, and the villagers in all directions; the last-named fled shrieking that ‘Satan was unchained again. It ended its comet-like flight in the horse-pond, and its inventor nearly followed it. Murdock, under Watts’ persuasion, very reluctantly abandoned his motoring ideas. Apropos of Watt, a warning to inventors. When first designed, his engine and its piston and mechanism for transforming rectilinear into circular motion by means of the crank (before then never used in conjunction with steam and so constituted a valuable patent) being much elated with

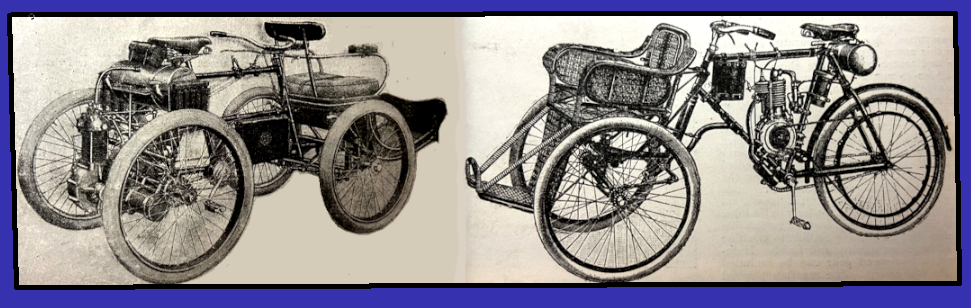

his success he walked down to the village inn, and there, in the presence of the elite of the place, proceeded to explain with accuracy his most recent idea, by the simple expedient of dipping his finger in his mug of beer; and tracing with this medium on the counter an outline of the invention before all beholders. or beer-holders. Amongst the company was a smart gentleman from London, named James Pickard, who, recognising the importance and value of the invention, immediately returned thereto, and filed the patent before poor Watt had a chance to do so. This same person actually sued Watt for infringement and Royalty on what was really Watt’s invention. However Watt immediately designed the sun and planet motion (geared facile movement) and thus evaded this imposition. The foregoing, however apparently irrelevant to my subject, is in reality most pertinent, as the crank and piston are the common foundation of nearly all motors. However, to continue to relate these almost forgotten incidents in connection with the subject would be to risk running into many volumes, so I will proceed at once to deal with the petrol motor, the advent of which heralded the first tangible progress in our movement. In 1885, Herr Otto. Daimler made his now famous motor-bicycle, with which most of us are familiar. The object of this construction was not to supply a practical vehicle so much as to provide a means of obtaining reliable data for the construction of other carriages. This machine (Fig 4) of Daimler had a most important effect, however, as De Dion, a little subsequent to this period, had experimented with steam with such disappointing results that he abandoned hopes of success but finally in 1895, or thereabouts, he practically took Daimler’s engine en masse (see Fig 3), and attached it to the back of a tricycle. I append a drawing of Daimler’s early engine. The original drawing appears in a most valuable work on motors, Petroleum and Benzine Motoren, by G Lieckfield, Munich, 1894, unfortunately published only in the German language. On reference to the drawing of Daimler’s engine, it will be seen that great resemblance between it and a sectional drawing of De Dion’s motor, even down to the valve arrangements and the enclosed flywheels (afterwards abandoned by Daimler), the only difference being that De Dion’s engine was entirely air cooled. How ever, this was a huge step in advance, for in the Paris Toulouse races in 1897, and many others, the tricycles easily beat the cars of that period. De Dion also constructed a motor bicycle about this time. He placed his tricycle engine just behind the bottom bracket, and drove from engine to back wheel by a

train of pinions. One of these machines I know for certain came to England, and I believe that Mr FW Baily, Hon Secretary of the English Motor Car Club, had some amusement with it—principally in railway trains. Contemporary with De Dion’s invention was the Hildebrand-Wolfmuller bicycle (Fig. 5). This came into being in 1895. One in the hands of Mr New was brought to England in 1896, and did some time tests and raced against a well-known cyclist on the CP [Crystal Palace] track. This machine achieved a speed of some 27 miles an hour on level ground, but its great faults were its slipping propensities and its lack of ability to climb hills. It came to grief on the track, owing, I believe, to the locking of the steering head, which caused it to charge the railings through which it passed in great style It afterwards appeared at the great opening motor car run to Brighton in November, 1896, but it did not cover much of the distance. I made its direct acquaintance in 1897, while on a visit to the Continent. Our intimacy was not of long duration. Being placed carefully in the saddle, and having got the control by means of the throttle and mixture, I went off in grand form at about 20 miles an hour. I felt very imposing indeed but suddenly became aware that there was a crossing some ten yards in front, and a large railway van just turning the corner. There was little time for reflection. In a second I realised that I could not get through, and in less time than it takes to relate pictured myself under the wheels of that van. My impulse was to swing the front wheel at right angles to the frame with the result that the machine and I came down at once—about four feet from the van—with a crash that resembled the discharge of a cartload of fire-irons. As I lay prostrate I saw my friend rushing up the road, swinging. his arms about wildly and shouting ‘Put out the lamps! Put out the lamps!’ As the machine was fitted with the tube ignition, the danger of the petrol firing can be understood. However, nothing happened in the way of an illumination, and I considered that I had got off cheaply with a cut knee and damaged hand. These I immediately dressed with petrol—a useful tip in such cases. The machine was absolutely uninjured. Apropos of the Wolfmuller bicycle, it is well to mention that this was perhaps the first practical motor-bicycle. The engine was water-cooled. The water reservoir took the form of a mudguard for the back wheel, the tank and carburetter (surface type) being placed on the fore part of the frame, and the foot plates in the place usually occupied by the crank bracket. Pedal-gear there was none. The gear for valves was actuated by a small ball-bearing eccentric placed on the back axle. Large India rubber straps were attached to the big end of the connecting rod and cylinder to assist in overcoming the compression. As the outward stroke of the piston extended these, they, in returning,

on the inward stroke exerted considerable force. A marked peculiarity of this machine was a funny tapping sound made by the carburetter. This was due to the two little non-return valves which served as air inlets. I have often wondered that this small feature has not been copied, for anybody who has placed his hand to the air intake of a carburetter when the engine is running will have felt the force of the ‘blow back’, and will be able to appreciate the economy which such an arrangement, if efficient, will bring about. Wolfmuller also constructed a tandem with four cylinders, arranged almost exactly as in the Holden engine, but it was not a success, chiefly owing to ignition troubles. In fact, for the first two years of its existence, the Wolfmuller bade fair to be a failure owing to this defect. I have a relic of the tandem in the shape of two of its cylinder covers fitted with two separate insulated plugs in each head, their points converging to parking distance. This machine was first fitted with the electrical ignition, but their system being faulty, lamps and tubes were substituted. These gave endless trouble, blowing out, going out, flaring, irregularly firing, etc, until, in 1895, I believe, Dr Ganz, of Frankfurt, brought out his improved pressure-fed burner. In 1897, Dr Ganz employed an engineer named Baur to ride his Wolfmuller so fitted in the Paris-Dieppe race (the first Gordon-Bennett). He duly competed, and would, in my opinion, have undoubtedly won this race, for the road suited the now vastly improved machine admirably, but unfortunately by an oversight Baur had forgotten to close the drain tap of the water tank before starting, and only became aware that something was radically wrong when his engine was nearly red hot. Not being able to speak a word of French, he had much trouble in explaining his wants to the peasants at the auberge at which he stopped in the anticipation of procuring the necessary water. At length he obtained what he required and resumed his

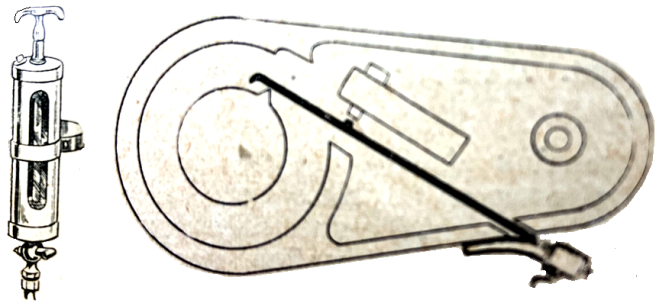

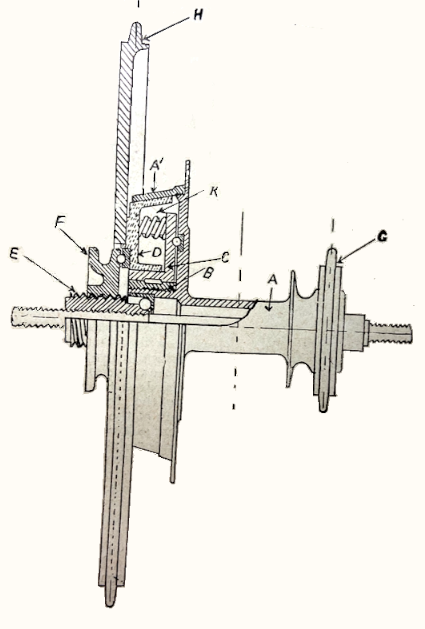

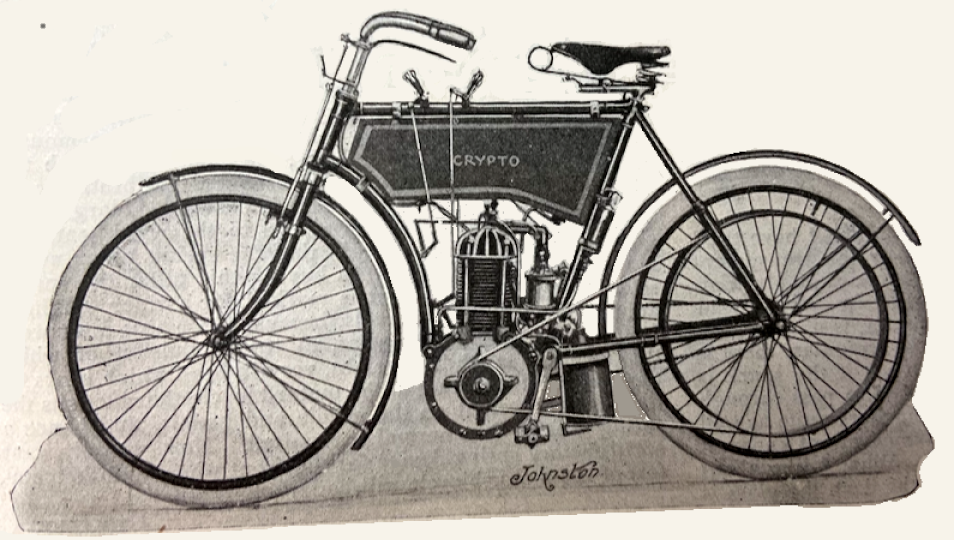

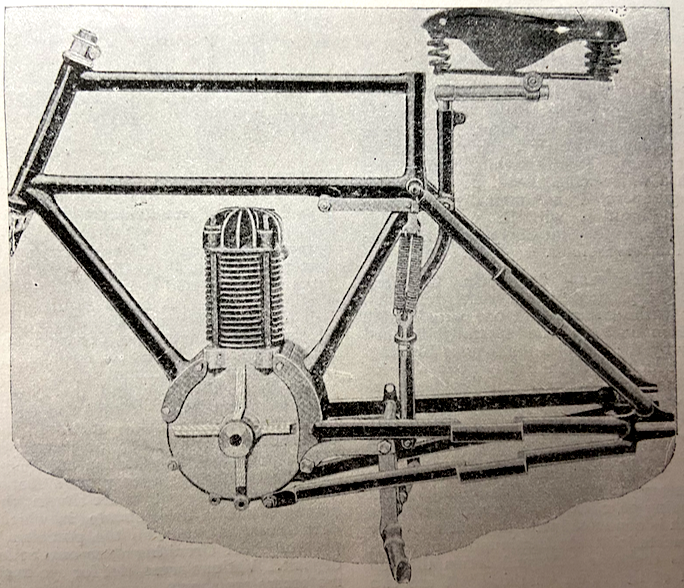

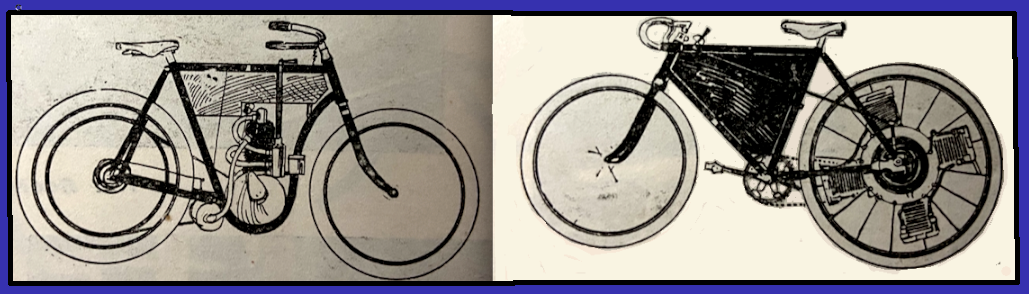

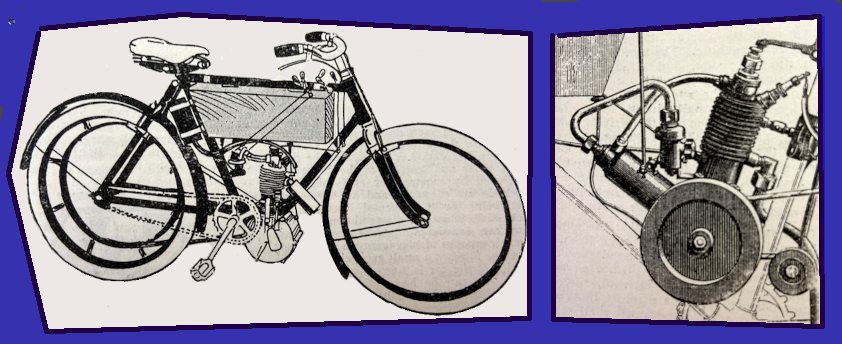

journey. Presently ominous sounds from the engine betokened more trouble. Dismounting he found it once more almost red hot, and the water tank again empty. At this juncture he thought of looking at the drain cock, which, of course, he found wide open. A horse pond being handy, he filled up and started again, and all seemed right. But not for long. His engine began to lose power in a remarkable manner, and upon examining his lubricators he found them empty. He had used the lubricant too lavishly on the cylinders before finding out the true cause of their over-heated condition. Managing to obtain some salad oil, he filled up with it and essayed to continue. As one may imagine, salad oil did not prove to be a very good lubricating medium, and owing to continual back firing Baur eventually abandoned the contest at Amiens. Another machine (see Fig 6), I might say an attempt to rival the Wolfmuller, appeared during 1896, made by Heigel-Weguelin, also a Munich firm. This machine was fitted with one large air-cooled cylinder, which occupied the position of the down tube from the head to the bracket, and drove a bevel gear therein which was continued to the back hub. The cylinder was 4in bore and with a 4in stroke, and was furnished with magneto-dynamic ignition. This cylinder, which I have still, is another interesting relic. This last-mentioned machine never achieved great notoriety, although one was to be seen about the streets of London a year or two ago. In common with the Wolfmuller machine it was a bad hill climber. The Pennington bicycle appeared at the CP cycle show in 1898. This was a somewhat similar arrangement to the Wolfmuller, only the cylinders were horizontal and reversed in their position, the heads pointing back and driving forward on to a pair of direct cranks. There were no ribs or other cooling device for these cylinders, which were fashioned from steel tube. Electrical ignition was fitted, but I never heard of this machine being at all practically ridden, it being one of those attempts to take an ordinary safety and gum an engine to it. However, it did have pedals, and was thus a true motor bicycle. At the same show I saw a small steam engine and boiler placed on a safety, the boiler in front of the handle-bar on a bracket, and a long-stroke single cylinder driving directly on to pedal gear. It was too small to be practical, although the intention was good. Major Holden’s bicycle was also shown in an incomplete state on the Crypto stand at this same exhibition. And now, I think, we may close the description of .these incomplete evolutions of the past, and come to the era of the really practical development of the modern motor bicycle. In mentioning the advent of the practical motor bicycle in the foregoing, it is well to state that actually the two periods, as we may call them, overlap considerably. The early efforts were, almost without exception, aimed at direct driving with comparatively slow speed engines. This as a rule involves a heavier machine in proportion to power given off; in the development of steam engines exactly the same transition took place. For example, compare the dimensions of engine of a 30-knot torpedo boat destroyer of 5,000hp with 2,000 or 3,000hp Atlantic liners of 40 years ago. It will be found that the latter weighed about as much as the former and occupied corresponding space—the difference laying in this: Forty years ago men were content with engines running 30 to 60 revolutions per minute, and used 50-lb pressure; to-day 300 to 600 revolutions and 200lb pressure are the rule. Although there are wide differences between steam and petrol engines, yet this rule to some degree holds good that the power of an engine to a large extent depends on the number of impulses given to a piston in a given time; thus in petrol engines, take a machine having 4 cylinders of 3-inch bore and stroke running at 500 revolutions per minute—it will give off approximately the same power as an engine having one cylinder of same dimensions running at 2,000 revolutions per minute; the number of impulses in both cases per minute are the same. Of course, the higher speed engine probably does not get the full charge of mixture each turn and has more resistance to the exhaust, and its power is correspondingly slightly less, but as it is, perhaps, about ⅓ to ½ the weight, its advantages to self-propelled vehicles are at once obvious and its chances of going wrong are also diminished; also the internal friction of moving parts is less. These theories have been more than borne out in actual practice, for it was found that the high-speed engine was not only a better hill climber, but that its range of control was also far larger; there are practical reasons for that which we shall, perhaps, enter into at a later date. Daimler, curiously enough, showed his grasp of the practical side of the question in 1885, for his bicycle engine was of the high-speed, geared-down, type. As I have shown, up to 1898 men still tried to perfect direct driving, and indeed, in the Holden, it is continued to the present day. The latter is certainly a masterpiece of design for this type, and may prove very successful, but I fear its weight is much against it, together with one or two essential points which my experience has shown me a motor bicycle should have. The first practical motor bicycles were without doubt the inventions, one in Paris of Werner Freres, the other in Munich by Alexander Bluhm; both machines were produced almost at exactly the same date during 1897. I illustrate the first machine as made by Werners, which differed from the later type in having outside fly-wheels, and outside bearing for front wheel. The driving pulley also placed outside the forks, was really a hollow rim and small wheel, built on a sort of secondary hub as a prolongation of the front wheel spindle. A reference to the drawing will make this clear. It was also fitted with tube and lamp ignition as were all the early De Dion machines. The first Bluhm bicycle was a tandem (see drawing), and was remarkably effective, as it was a fair hill climber and attained a speed on the track of over 45 kilometres an hour (about 30 miles). It was chain driven, weighed about 150lb, and had a method of running the engine free, and curiously enough, in view of later developments, ignited its charge by means of an automatic catyaplatinum system, which was started by means of an electric current. Only the front rider had pedals, and these were mainly for starting the engine. The back passenger had foot rests only. The engine had a bore of 70mm with a stroke of 70mm, and was geared to back wheel at 5 to 1. It was designed to run at a speed of 1,200 revolutions per minute. This engine drove a small sprocket wheel, geared to a larger one by a short chain; on the axle of large sprocket was a chain wheel which transmitted the drive to back wheel. This axle also carried the chain wheel (which was fitted with a direct clutch) by which the power for starting engine was conveyed from the front rider’s pedals. A reference to the drawing should make this quite clear. This motor bicycle is still extant, and was running up to a short time ago, but I have not much news of it lately. It survived most of the early Werners and should be of great interest to latter day motor bicycle designers who, perhaps, fancy they have done something new in designing a machine chain driven and started with overrunning clutches. The next machine which was designed by Bluhm has a great interest for me, as I have ridden it the greater part of the last three years, and is undoubtedly one of the oldest practical motor bicycles running, but a faulty casting (aluminium crank case) has developed defects which necessitate its retirement to some museum. This machine differs from the tandem in some important details. The engine (size, 65mm bore, 70mm stroke), instead of being connected by a chain to a large sprocket wheel, a toothed pinion took the place of the latter, and the engine axle had a small pinion in mesh with this, the axle in the large pinion was hollow and through it passed, running on ball bearings, the pedal axle; this, on the opposite side to pinion, had a sprocket wheel in connection by chain with back hub, and free wheel, the pedal axle could be connected or disconnected with the large pinion axle at will in order to start engine, or to pedal the machine as a simple bicycle. The large toothed pinion had also a chain wheel on it driving a chain on the other side of back hub, also fitted with free wheel clutch, this latter was found absolutely necessary, to prevent chain breaking if engine back-fired. I show a diagram of engine and its arrangements; by-the-bye, it is well to mention this machine had electric ignition, the contact breaker of which was fitted on large pinion axle. I have derived

a great deal of pleasure from this machine and it was very reliable, as I had fitted it with a 2-gallon petrol tank and large lubricating oil reservoir, I could take fairly long journeys, my longest day’s ride was 140 miles, starting 11am and finishing 7 to the evening, with two stops for personal refreshment. The machine could always average about 25 an hour over give-and-take roads, and owing to the pedalling gear being 84, I could assist the average of my mount up hill very materially and found it most exhilarating to do so. I never had an actual side-slip with this motor, but I came off once owing to trying to take a slippery corner at top speed. The whole concern simply slithered about 10 yards sideways and then lay down very suddenly indeed, so to speak. I rode home some 20 miles, later, which shows there wasn’t much harm done. On another occasion I put on the first brake too suddenly on a very wet road, downhill; the front wheel simply locked, skidded, and once more ‘took the floor in style’. Result: broken pedal and a lost temper. However the things and opinions I expressed to myself about myself on that occasion have so impressed me that I have not repeated the performance since. I consider that both these falls really resulted from the weight of machine (some 140lb), and the large-diameter smooth tyres I used. I then fixed oat bands with most satisfactory results. It may be of general interest for motor cyclists to learn that Mons Bluhm has lately designed a new type of machine, somewhat on the old lines but much simplified and lightened. This machine will be exhibited in the Automobile Club show at the Agricultural Hall in April-May. Although I have full particulars at hand, I am most unfortunately precluded from giving them as foreign patents are pending. The above machine was also made as a tricycle with no alteration to engine at all, simply a back bridge and balance gear in place of hub. I have ridden it a good deal in this form and it had some distinct advantages over the De Dion type. I may mention the chain drive as fitted was perfectly satisfactory, a ¼ inch racing chain lasted for two years, ie from 1898 to 1900, since that date two other chains have been used, and machine is still as fit as new. The same sparking plug has been in use the whole time and is as efficient as ever. I am ready to satisfy anybody who may require further information on above points, but I think they nearly constitute a record. And once more to retrace our steps a little. In the autumn. of ’98 I had a good deal of experience of the early Werner. I was staying near Ostend at that time, and there is a lovely kind of Parade (commonly called ‘La Digue’), about 3 miles long, and after that continuing on a sort of brick footpath to Middle-kerke, about 8 miles in all. It made a capital practice ground for my early experiments, in which I gained a lot of information about the effect of a strong sea breeze on tube and lamp ignition. The great advantage of this machine was that, when I was tired of playing at ‘motors’ with it, I could take the belt off and it wasn’t much worse than an ordinary bicycle. Under favourable conditions one could get nearly 20 miles an hour out of it. The chief troubles were due to the carburetter, and the very exposed position of the ignition lamp. Regarded as the foundation of a large class or division of motor bicycle, it is full of interest, for the only difference between the frame and ordinary safety lay in the front forks, and I regard it as the first practical attempt to convert any usual form of bicycle into a motor propelled machine; for there are, to my mind, three broad classes or divisions between modern motor bicycles, ie (1) Motors made or fitted to any ordinary pattern frame; (2) A frame built to take in an ordinary pattern motor as De Dion; (3) A machine in which both frame and motor are specially designed each to suit the other’s essential requirements. The latter is undoubtedly what the 1902 pattern has come to, which shows that attempts to make a motor in order to convert any bicycle into a motor driven one are bound to be superseded by the more perfect combination designed for the altered conditions of traction which attain when a motor does the principal part of the propelling. A machine belonging to the second category appeared in ’99. known as the Shaw, made by Shaw & Sons of Crawley. It had

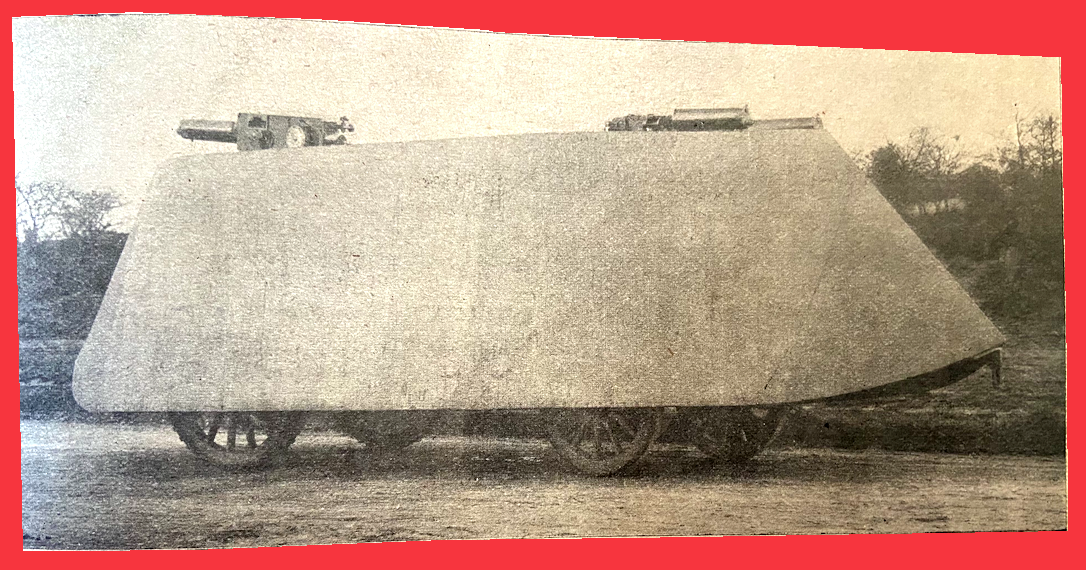

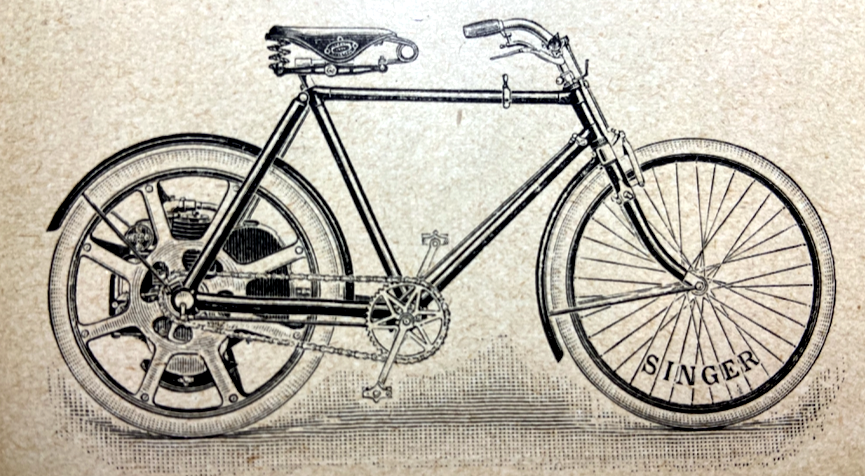

an ordinary 2¼ or 2¾hp De Dion motor built in just behind the crank bracket; when it first appeared it had no pedals and was chain driven, absolutely rigidly, and was started by running the machine along till the engine chose to chip in. There was evidently a good deal in the machine that was commendable, as I have an acquaintance who has always. sworn by it, and has ridden one consistently for some two years. The great drawback to the early type was undoubtedly the liability of the chain to break (which it used to do pretty often). This was, no doubt, occasioned by the back pinion being a fixed, instead of a free wheel, as in the Bluhm; but, of course, if Shaw had used a free wheel he would have had to arrange for some other method of starting the engine than the method named. But the difficulty has been apparently avoided by substituting a belt instead of a chain and attaching pedalling gear on other side. The little experience I had of this machine showed it to be very fast and powerful ‘climber’. Another machine belonging to type 2 will be shown. at Fig X. It was of French origin and I came across my first example of it at Easter ’99, in the town of Ghent, Belgium a 2¼ De Dion motor was placed transversely just in front of bottom bracket, which had no pedals but only rests for the-feet. The engine shaft was continued by a long shaft having a universal joint at the engine end and a bevel gear at the back hub. This machine ran fairly well however, but during the short trip I made on it, the engine knocked off work three times in 100 yards, owing to defective carburetter. Anyone who knows the streets of Ghent and Rue Neuf, St Pierre, where this little episode took place, can easily place credence on that statement. I do not know if the machine is still made, indeed I forget its very name, but it seemed to me an attempt to carry light voiturette practice into bicycle work, but it is of interest, as it is the second instance we come to in which a bevel gear for driving is employed. Heigel Weguelin being the first. From ’99 to 1900 the movement made a very sudden jump and I fancy that no less than 20 new designs appeared during this period, the best known of which being perhaps the Minerva. It would be tedious to go into details of most of these as descriptions have appeared at one time and another during the past 18 months. The ‘Automotor Journal’ came out with a very complete list with descriptions and diagrams about a year ago. Generally speaking it struck me that those which were original were absurd for their purpose and those that weren’t were copies or variations of the Minerva and Werner types. Sir Hiram Maxim, of flying machine and quick firing gun fame, had a little flutter at motor cycle design in latter part of ’99; in connection with which he took out some patents, in which he states his aim was to attain simplicity of construction and working. The machine was not exactly a bicycle or a tricycle, inasmuch as it had two driving wheels at the rear placed about one foot apart and keyed rigidly on a cranked axle. This latter was driven by a very large two-stroke petrol motor; a two-stroke motor is more or less an idiomatic term for an internal combustion engine obtaining an impulse or explosion for each revolution. I never saw this machine, but it appeared to me a most unpractical design so far as one could judge from the specification and patent drawing; it had no pedals, as may be surmised, and the frame consisted of two huge tubes extending from head to back axle, these tubes formed petrol tanks and beneath was placed the above described cylinder; this machine brings to my mind that late in the eighties or early nineties Messrs. Roots and Venables made a tricycle having a small two-stroke engine connected on to back axle by bevel gear; it was not a direct process, owing to its tendency to back fire or ignite the incoming charge of mixture, due to some incandescent portions of previous exhaust stroke remaining in the cylinder, but I believe it enabled that firm to obtain much useful data, and during its experimental periods it was often to be seen endeavouring to urge its career down High Holborn, long before the motor car Emancipation Act of 1896 was dreamt of. Having now given a brief resume of some little known efforts of the past, let us turn our attention to what has been the more or less direct outcome of these well-meant efforts. I will commence this with a motor tricycle little known in England, though there are a great number running in Germany, known as the ‘Jooss’ pronounced ‘Yoss’. This was designed some three years back by the maker of the Hildebrand-Wolfmuller machine, and was the outcome of his seeing the failure of the slow-speed direct driving engine as applied to motor cycles. It is a somewhat unique machine, inasmuch as it rejoices in the possession of two cylinders working on one crank by a rocking shaft arrangement shown in Fig XIII. The dimensions of cylinders are 55mm bore and 60mm stroke giving, so the makers assert, ⅝bhp at 1,500 revolutions per minute; and it is not intended to run faster than that. Its speed is under favourable conditions, nearly 30 miles an hour (2min 6sec for the mile is the best I have done, timed), and it takes a grade of 1 in 12 very well indeed. The single fly-wheel is outside on the right and of 11 inches diameter, and the driving pulley on the left, the transmission is by an endless plaited square cord and this wears extremely well. I have had one belt running without change for the last year, and it seems good for a bit more yet; a jockey pulley fitted with a ratchet lever is situated so that one can tighten the belt instantaneously. I am inclined to approve of this arrangement, as I find that on the level the machine drives best with the belt just taut; tighter than that slows the machine; up a hill, however, if the engine starts slipping, this can be at once remedied, I have found this machine the most convenient of any I have ridden in traffic as if a block occurs I at once slack off the belt, letting the engine run free; and starting again like a car, by just giving a touch to the lever. This machine has simple magneto-electric ignition, there is no spark advance or retard, control of speed being obtained by varying the mixture and by cutting out. A simple exhaust valve lifter is fitted, and the machine is about the most ‘fool proof’ one I know, and I fancy as the movement stands at present, that this is a most essential qualification. I have never had a side-slip on this machine at all, its weight is 80lb. Birch & Perks’ patent bicycle, as made by the Singer Cycle Co, is another endeavour to obtain extreme simplicity although I cannot honestly say that I think the interior of the wheel is the place for a motor. But of course time will enlighten us more on this point. The engine is the best finished and made that I have seen, which might be expected from the standing and reputation of the above makers. Of the Minerva type of machine, I think this may prove to be the nucleus, as it were, of an immense development, but as it stands and is generally made it is rather heavy and, to my mind, underpowered. I may mention that I have certain information that in France machines are already being made with cylinders 75mm by 75mm weighing from 60 to 80lb. This, my experiences teach me, is what will be more sought after shortly. No matter how good an engine is, then are times when it will not give off its best, perhaps bad petrol, a weak battery, unfavourable climatic conditions, &c, and I do not think 50% too large a margin of power to allow for these eventualities, as one can double the power of the engine by adding perhaps 10lb to the weight of it. I, for one, approve most strongly of any attempt to make a serviceable roadster weighing not more than 90lb, with the greatest possible engine power consistent with the proper construction and proportions of the rest of the machine for speed. The gearing of engine can be altered to suit the part of the country the machine is required for, and hill-climbing power is always there without the expense and trouble of two speed gears. It is better to increase the power of the engine than to add any further mechanism to it. Of course these modern machines are far too familiar to most of us to need any detailed description here; but there are one or two I should like to mention—for instance, the Mitchell, an American make. This machine has an

engine 75mm by 75mm, and should be capable of great things, but from a few days’ experience of it the following points struck me: the flywheels were too light, and if I owned one I should add a 9in 10lb extra one to the outside, with pulley attached. The carburetter I do not approve of, though it may in some be unnecessarily heavy; also the silencer. The electrical arrangements could easily, in my opinion, be bettered by using accumulators instead of dry batteries and a more efficient coil, the make-and-break contact is ingenious, but, as in most of this type, the ‘break’ is too slow for a good spark, especially at starting, when it is most wanted. One conclusion forced itself on my mind when riding this machine, which is this, that as the power of the engine is increased the efficiency of a belt to transmit is decreased, and as the engine power undoubtedly will be augmented very much presently, makers will, I think, be wise in studying the perfection of the chain drive. These changes took place in cars, as also the transposing of flywheel from inside a case to the outside of it, and we shall see the same in bicycles, I feel sure. A machine which took my fancy greatly at the late Stanley show was the Petrocyclette

shown by Mr Marriott, the old long-distance rider, now residing at St Albans. It was chain driven and had a friction clutch like a car, forming part of the large single exterior flywheel. This clutch was actuated by a lever on the top tube. The machine was most beautifully made and finished, and Mr Marriott spoke of its reliability and convenience in the highest terms; and as the machine has many points in common with one I had designed just previously to the show, embodying what I thought was required in the machine of the future, it may be imagined that I could heartily agree with him in his commendations. My machine will not be finished for some time yet. The only points that struck, me were that the engine was somewhat small, and its cooling arrangement rather ‘faddy’, in view of the good results attained in far larger engines using simply broad thin ‘Ailettes’ on the cylinder and cover. There were many machines at the same show having chain driving and an overrunning clutch driven by the pedals to start the engine, but in view of a machine I mentioned as being made in ’97 I do not think this is the ideal transmission we are looking for and must have. I will not now indulge in further criticism of modern machines all well known and on their trial, but the following points my study of the question seems to assure me are essential: 1st—A method of putting the engine in and out of gear at will. 2nd—Means of starting and allowing the engine to run whilst machine is at rest. 3rd—Arrangements so that the machine can at once be used if desired; as to such things as carburetters, firing and electrical devices, valves, &c, the best will soon sort themselves out when a definite type of machine is more common, and in these things, as the French say, ‘Chacun a son gout’. I think this form of sport has an immense future before it, as large in its way as the car part of the movement, if not larger. The control over time and space and the exhilarating sense of power, so dear to the heart of the sportsman, have a fascination for myself that words cannot express, and I feel sure it is the same with all those who try it, and who have the patience to learn confidence and control of their engine. I think time will show that the car for old age and comfort and the skeleton single-track machine for speed and youth, will undoubtedly be the two divisions of automobilism. And now that we have really and truly a paper and journal of out own for the latter branch, developments will not be slow in forthcoming. There is no doubt the bicycle or skeleton racers will outstrip the fastest car in point of speed, if men can be found to ride them, but having indicated a future of dazzling proportion for our sport I will leave the imagination of the reader to carry him into it.”

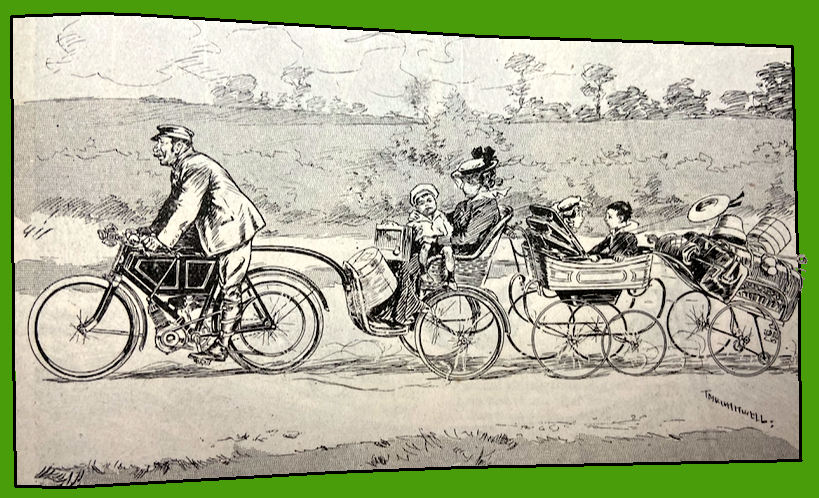

“CANDIDLY SPEAKING, MOTOR CYCLING is the best kind of pastime I have struck yet. And I think at one time or another I have tried them all from Rugby football down to parlour tennis. It used to be claimed for golf that it was the ideal exercise for body and brain—but that was before motor cycling had been invented or become possible. To my mind there is nothing in the world to be compared with motor cycling under favourable conditions and no sense of enjoyment so keen as that to be obtained from travelling along a well surfaced road at anything between ten and twenty miles an hour, bathing in the fresh air and sunshine, with a proper appreciation of surrounding scenery and finding occupation all the time for one’s mind in the working of the motor, trying to get the best result from it under all conditions and learning by sound and almost by instinct the way in which it is working and the best method in which to handle it with that end in view. And then there is that spirit of competition which gives an added relish to our enjoyment; the gradual overtaking and eventual passing of others on the road, whether they be either drivers of horses or well developed and athletic young cyclists of the customary kind. Uphill and down the motor cyclist feels that black care has left his shoulders for ever, and the business worries of yesterday’s workaday world have disappeared. Downhill he flies with exhaust valve open and current switched off to cool the engine and prepare it for the next ascent; and this begun, he sets his legs to work, and with gentle pedalling assists it to the summit. At the end of the run neither his appetite nor his sense of satisfaction is any less keen than they were wont to be ten or twenty years ago after an hour and a half of exciting ‘scrums’ on the football field, a ten mile spin across country at hare and hounds, or a thirty mile ride—or scorch—on bicycles with bootlace tyres of the solid sort and a hard ding-dong at the finish. Dusty he may be; he may have a sense of flies in his eyes and a taste of the same in his throat; but dust and flies are alike easily removed; and during the time in which he has been acquiring them, he has enjoyed every minute of his existence, and the cobwebs that during the week had gathered round his brain have all been blown away. He stables his machine with a feeling of pride, increased rather than diminished by the remarks of the on-lookers at its rarity and virtue, he eats his meal with a relish, and enjoys his subsequent pipe with even more than his customary gusto as he suns himself under the cathedral wall, lies prone in a sunlit meadow or watches the river glide by under the arches of the bridge in the old town to which he has made his pilgrimage. And when shadows begin to lengthen he seeks once more his machine,

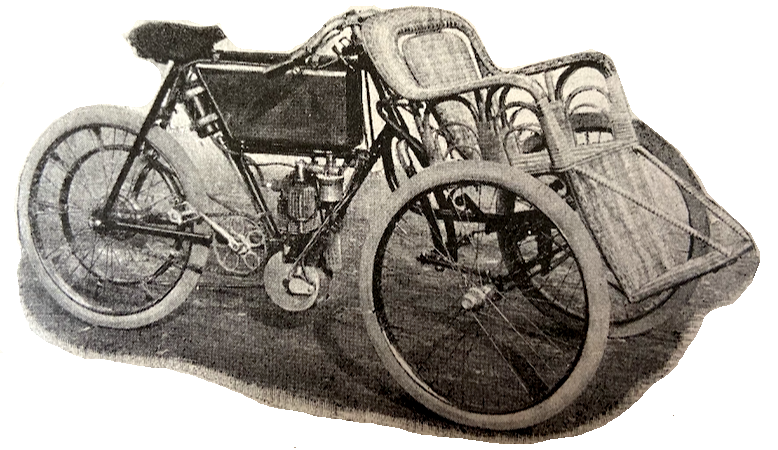

carefully overlooks tyres, nuts, sparking and other vital parts, injects a drop or two of paraffin into the cylinder head and sets off in cool of the evening on his homeward way. Thereon the engine working well in the keener air, his way will probably be even pleasanter than before; the setting sun be casting more mellow lights on trees and hills; the workers from the fields, having finished their round of toil, will be devoting the last few hours of the week to rendering their own gardens neat and trim, and will gaze with open-mouthed wonder and good humour at this new invention, the motor cycle. Of such are the delights of motor cycling under its best conditions and in its single form. The single machine, whether bicycle or tricycle, is a selfish instrument ; but the Quadricycle, at no great increase either in capital outlay or in cost of up-keep and motive power, permits the easy carrying of a partner to share with us our joys and sympathies and assist us when skies are unpropitious and breakdowns occur. For it is not always plain sailing; roads are not always good, and the sun does not always shine. Now and again the inevitable sometimes, unfortunately, happens, which may necessitate an hour or two’s work by the road-side, during which we chafe under the cynical comments or kindly meant sympathy of those same rustics who so lately cheered us gaily as we sped along; the hour’s work itself may be in vain, and we may be reduced to the ignoble position of having to call horse and cart to our aid to tow or carry ourselves and our unruly instrument to the nearest town or railway station; or may be recognising the fact that the only thing required to make it go is something we have not with us, we leave the machine to its fate in friendly hands and set off homewards on foot or on a borrowed bicycle.”

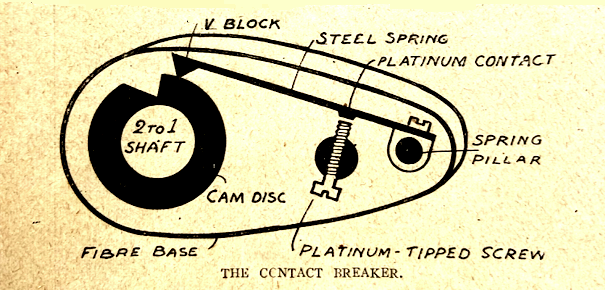

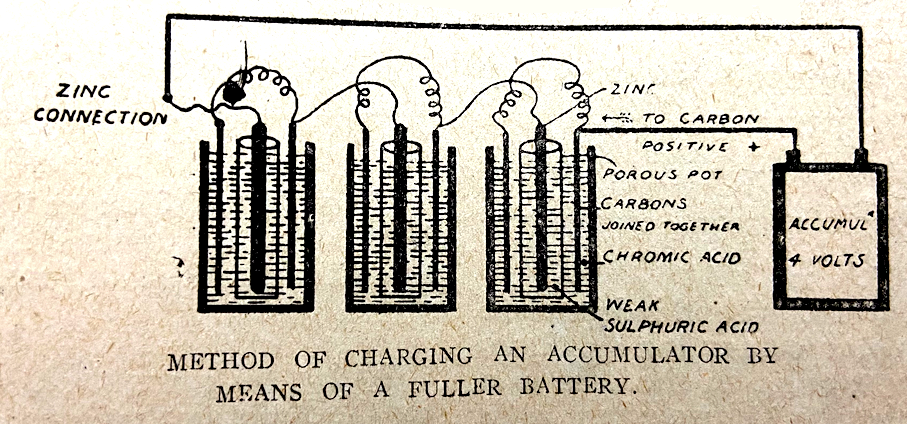

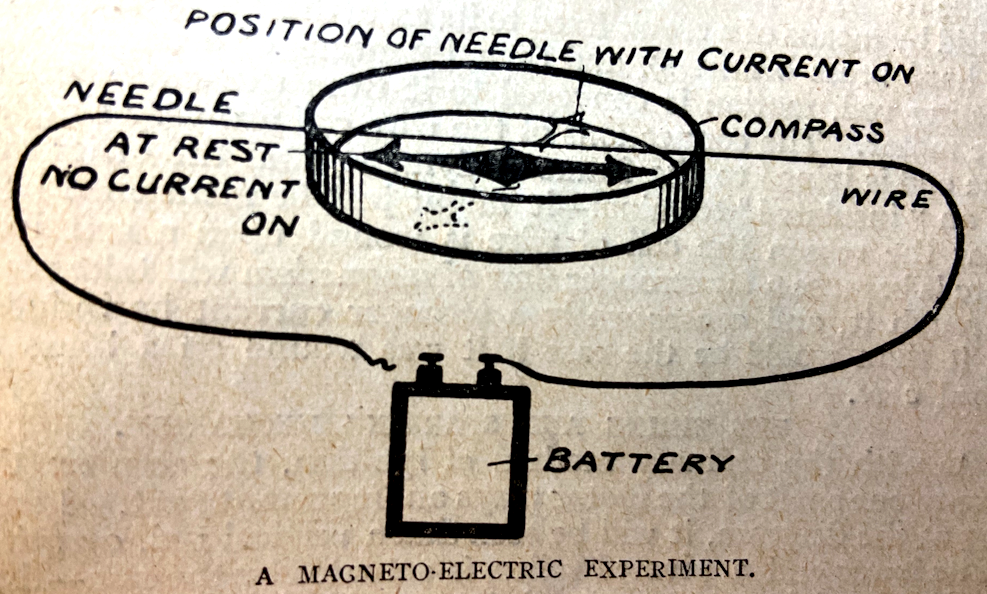

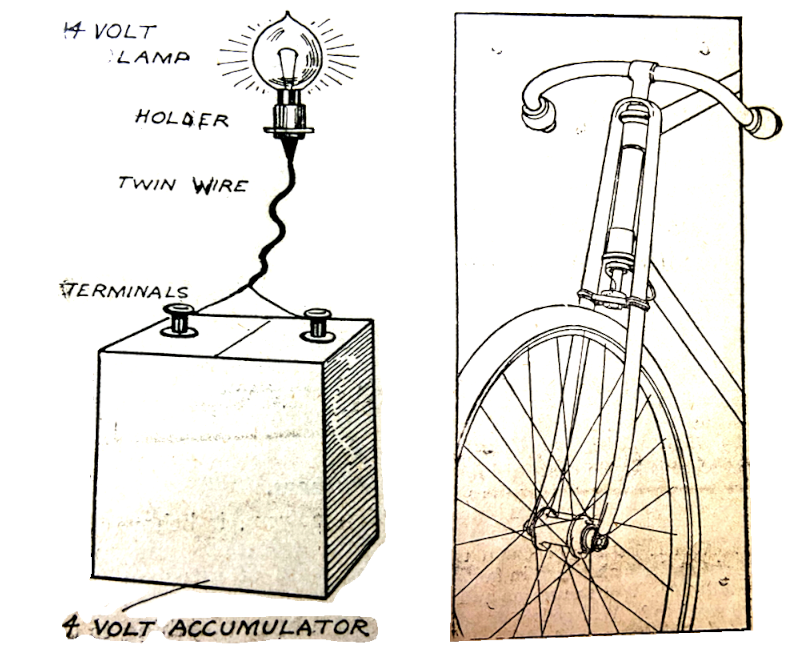

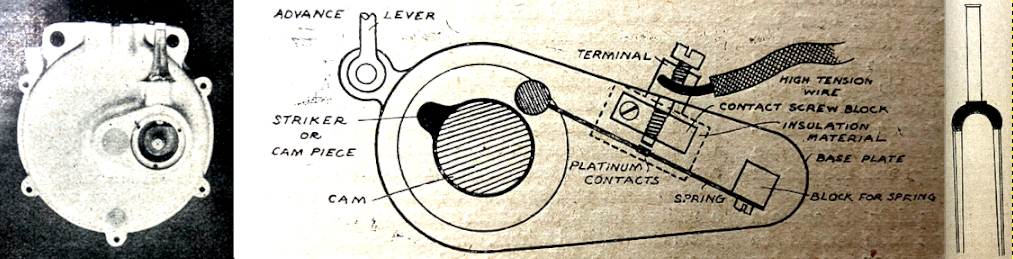

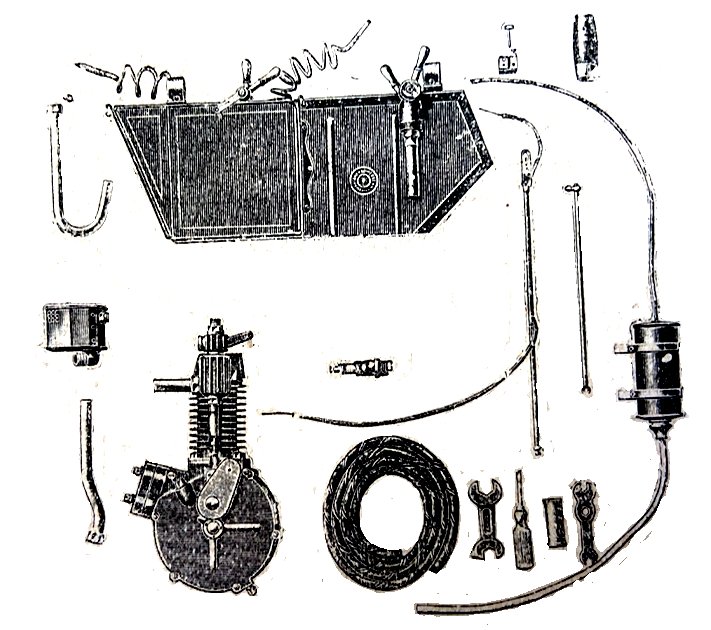

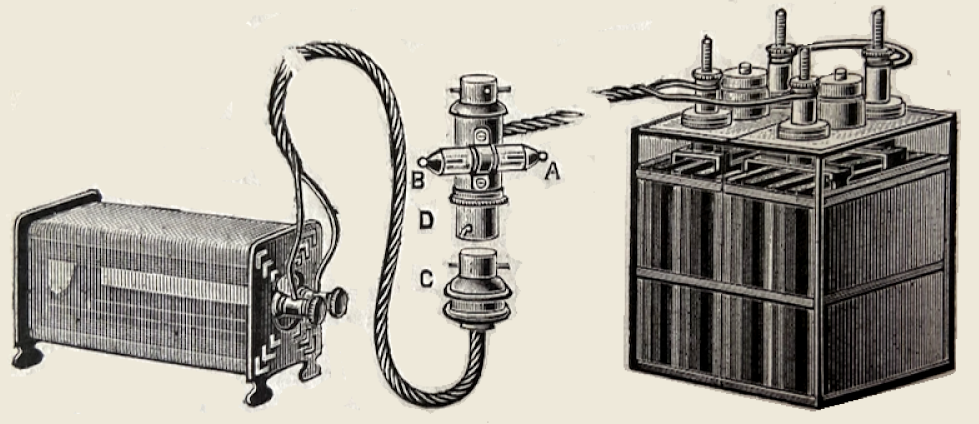

Many experienced riders will confess to occasional confusion when it comes to motor cycle electrics. In 1902 experienced riders were few and far between and converts from pushbikes faced a nigh-on vertical learning curve. Motor Cycling was ready and willing to enlighten them.

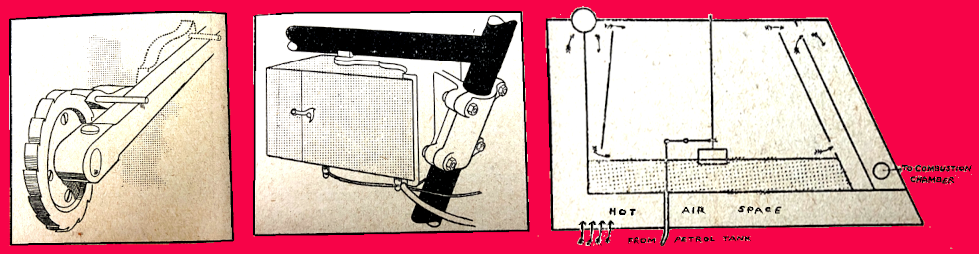

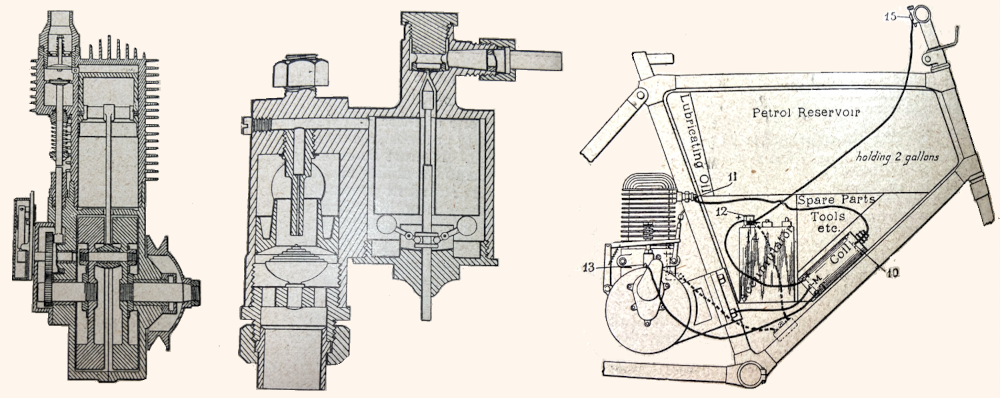

“MOST OF THE TROUBLES encountered in the running of a motor cycle may generally be traced to some defect in the electrical system adopted for firing the explosive mixture of gas and air in the motor cylinder. The early patterns of the motor bicycle, notably the Werner, were fitted with ‘tube’ ignition. This arrangement was very simple in principle, consisting briefly of a platinum tube kept at a bright red heat by a small spirit blast lamp. This tube was fixed in a chamber attached to the cylinder of the motor, and an arrangement of slides or valves allowed the explosive mixture to come in contact with the red hot tube at the right instant. This system was easily understood by the non-technical. rider and was found reliable and easily kept in order. Its great drawbacks however were (1) the liability of the naked flame to come in contact with the petrol by any means (say in case of a fall) and thus cause an explosion in the carburetter or tank ; (2) the limited range of speed and power obtainable. Both these defects are absent in the electrical

system of ignition now used, its safety and efficiency indeed, being remarkable, but we are now using certain mysterious looking pieces of apparatus and their wire connections, the scientific principles of which the motor cycle novice has only the vaguest idea, consequently he is at a loss how to account for many of the difficulties and is thereby put to expense and inconvenience which could be avoided if he would learn at least the fundamental. principles of the electric ignition system. The object of these articles will be to put these principles before the reader in the simplest possible language, so that, with the aid of diagrams, practical hints and directions, he may able to keep this most important part of the motor bicycle in good order. In this article will be described in detail the system used on motor bicycles of the two main types, viz, the Minerva and the Werner. In fact, we may say that 90% of motor bicycle makers are employing the coil and battery system, in distinction to the few who use the dynamo system. The component parts of the coil and battery system are: (1) The battery which supplies the electrical energy; (2) The coil or transformer which increases the the tension or pressure of the electrical energy; (3) The contact breaker or automatic switch which is worked by the.motor and sends impulses of electrical energy through the coil; (4) The sparking plug which allows the high-pressure electric impulse or current to produce a tiny spark or flame in the explosive mixture and thus ignite it; (5) The main switch on top by which the current is cut off at will by the hand for stopping, and starting the motor; (6) The insulators or protected wires which conduct electrical energy to the desired positions; (7) The ‘timing’ lever attached to the automatic switch or contact breaker, which, to a large extent, regulates the speed and power of the motor. The battery, sometimes termed the accumulator or storage cell, is totally different in construction and principle to the ‘dry’

battery in use on some patterns of tricycles and cars. The general type of storage cell met with consists of a celluloid or vulcanite box, divided into two watertight compartments in each of which are fitted 3 or 5 gridwork plates of lead. The spaces forming the grids are filled in with a paste containing oxide of lead (such a one, for instance, as ordinary red lead. The plates are immersed in a mixture consisting of sulphuric acid (oil of vitriol) and water of a certain strength or proportion. Now, when these plates are connected together in a certain way and a current of electricity from a generator, termed dynamo, is sent through them when immersed in the acid, they extract certain gases composing the acid and accumulate them on their surfaces as it were; this is technically termed electrolysis or decomposition of acid. When the plates have absorbed as much of these gases as possible, the battery is said to be charged, but strictly speaking, not charged with electrical energy but with chemical energy. The store of chemical energy, may, with great ease, be changed back into electricity. This is the operation known as discharging, and when all the chemical energy is used up, no more current can be obtained, therefore the operation charging muss repeated. This method of producing

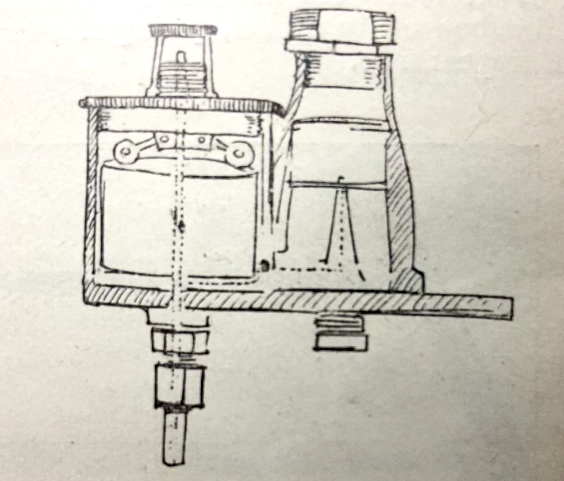

current for sparking may seem a roundabout one, and a much simpler method in fact is to obtain your current by the burning (in a chemical sense) of the metal zinc as adopted in the ordinary household electric bell system, but this method cannot compare with the accumulator system on the points of reliability and compactness combined with large storage capacity (a most important point in a motor bicycle) and certainty of giving current of a uniform strength at all times. In outward appearance the induction coil or transformer consists of a closed cylindrical case of vulcanite, at the ends of which arc fixed small brass fittings known as terminal screws. Inside the case would be found coils of insulated copper wire, wound over a central ‘core’ or bar formed out of soft iron wires, while in addition is there is a paper and tinfoil arrangement termed a ‘condenser’, which serves an important function. The exact purpose of the coil in the electric system of ignition is to increase the pressure or ‘tension’ of the current, which is supplied by the accumulator, to such a degree that it will be able to jump across a small air space in the form of a spark. Without the aid of the coil it would be necessary to use some hundreds o accumulators connected together to force a current across ¹⁄₁₆ inch even! To understand exactly how the coil increases the pressure involves some considerable a knowledge of electrical theory, but, the non-technical reader might get an idea of the function of the coil by comparing it with the gearing system of an ordinary chain driven cycle. Here the power supplied by the rider’s legs is converted into speed by the process of ‘gearing up’, but there is no actual gain in mechanical energy, in fact power is to a slight extent lost owing to leakage and chain-friction &c, so we may regard the coil as a ‘gearing up’ system between battery and sparking plug. Part of the power supplied is here also lost by the ‘resistance’ or friction of the wire coils through which the current passes. The process by which the transformation of the low pressure of the battery to the high pressure available at the sparking plug takes place, is that known as electro-magnetic induction and is described in good text books on electricity and magnetism. The contact breaker or trembler is a most important detail of the ignition system and forms a part of the motor mechanism. Its function to cause the current to circulate through the coil and stop instantaneously at the exact instant that the explosive mixture in the cylinder is at maximum compression; simultaneously with the stopping of current the spark takes place in the explosive mixture and fires it. The construction of the contact breaker is very simple and efficient in action, and is practically the same arrangement as used by De Dion. On the cam or 2 to 1 shaft of the motor is fixed a base plate of vulcanized fibre. On this is supported a brass pillar and flat steel spring, a V-shaped metal block is fixed to the free end of the spring and engages in a notch on the revolving cam. On the fibre plate is also fixed a brass pillar carrying a screw which is tipped with a tiny bit of the rare metal platinum; this platinum tip presses against a similar one fixed to the lower side of the spring. The reason platinum is used for the ‘contacts’, is because every time the tips separate a small electric arc or flame takes place between them when the motor is working; no other metal but platinum will resist the burning and corrosive effect of this arcing to anything like the same extent. This method of construction is adopted chiefly on motors of the Werner type, but a slightly modified form is used on the Minerva motor, inasmuch as the fibre base is replaced by a light metal one, the contact spring being fixed in -metallic connection with it, and the platinum tipped screw is insulated from. this base by means of a somewhat thin Mica washer dipped under its support. Another distinguishing feature is that instead of the V-block or spring dropping into a slot in the cam disc, a projection on the disc strikes the block and presses the spring contact on to the screw, thus ensuring a perfect ‘make’, the tension of the springs, of course, bringing the points out of contact. Both types of contact breakers are now provided with light metal covers for protection from oil and dust. The ‘timing’ or advance sparking lever is an attachment to the contact breaker, and consists of a simple arrangement of hinges, rods, or levers for moving the contact breaker to various positions of the cam circle. It allows of the spark being produced in the explosive mixture

at various phases of its compression, enabling the speed of the motor to be regulated by the operation of late or early joining. As an example, to obtain the greatest power out of the motor the spark must take place the instant the piston has completed the compression stroke. The sparking plug serves the purpose of conveying the high-tension current into the combustion chamber of the motor and provides a minute air gap for it to jump across in the form of a spark. In construction it consists of a screwed metal socket into which an insulating bush of porcelain or mica is tightly fitted. Through the centre of this bush passes a steel or brass wire ending in a platinum tip where it enters the combustion chamber; this tip almost touches the body of the plug, missing it by about ¹⁄₄₀ inch, and this space forms the sparking gap. The outside end of the plug is threaded and provided with nuts so that the high-tension wire from the coil may be attached. Porcelain or mica are the most suitable materials for sparking plugs owing to their high insulating and heat resisting properties, but glass has also to some extent been used. In most machines the main switch is arranged in one of the handlebar grips, and may be regarded as a tap which controls the electric circuit. The principle of an electric switch is easy to understand, being simply some method of bridging a gap in circuit by a conductor and thus completing it and allowing the current to flow. In addition to the main switch there is generally a second or reserve switch fitted of the plug type (distinguishing it from the handle switch) and this consists of an arrangement for screwing two brass washers into contact. The insulated wires or conductors are of stranded copper covered with indiarubber and prepared tape. The wire carrying the current from coil to plug is more heavily insulated than wires from battery to coil, as the increased pressure needs thicker rubber protection. The position of the coil and battery varies with the type of machine. In the Minerva both are carried in the case fixed in the diamond frame, in the Werner the coil is clipped behind the diagonal or seat tube and the battery is carried in a separate compartment of the petrol tank. Some

American types of motor bicycles have the battery slung or clamped behind the saddle. The positions of contact maker, switches and sparking plug are practically the same in all types. Now, looking at the diagram, it will be seen how the wires are run to the various parts of the system. Starting at the + or some positive pole of battery, a wire goes to one of the primary terminals of the coil, from the other a wire is connected to contact screw of trembler or make and break, and the spring is directly in contact with frame of bicycle—this, of course, conducts the current through handle-bar to the switch where the wire circuit recommences, is broken at plug switch and goes on again to the negative pole of battery. Then the other circuit, which may be regarded as quite independent and not connected with the other one, consists of one thickly insulated wire from the single terminal of coil to sparking plug direct. The other end of secondary coil makes contact through one of the clips to the frame, so that even in this circuit we have a ‘frame’ return. Why is the frame utilized as a conductor? From a purely electrical point of view it would be more correct to adopt an ‘all wire’ circuit throughout. This would entail the use of a more complex design of sparking plug, viz: one with two insulated poles and two thickly insulated wires from coil—which would now have two secondary terminals instead of one; the condenser connections in coil would be different and an extra wire would go to handle-bar switch. So that increased electrical efficiency would entail somewhat of a loss in simplicity of wiring, design of sparking plug, &c, but still it is a fact that this ‘frame’ connection is the cause of a lot of breakdowns owing to short circuits taking place. This frame connection is sometimes termed an ‘earth’ because the bicycle is insulated by the tyres—excepting when wet a partial ‘earth’ is formed. Charging the accumulator. One of the the greatest troubles experienced by the motor cyclist, is: When and how is the battery to be charged? Upon having a store of electrical energy that can be relied on much of the successful running of the motor depends. When the new machine is delivered, the accumulator is supposed to be sent

out with a maximum charge in it. This is really rarely the case, because the battery requires a considerable amount of use in the way of charging and discharging to get it up to full capacity. After the first 100 miles the battery should be recharged. To do this there are several methods—one being to take it to the depot, another one is to get some user of the electric light to allow you to connect it up to one of his lamps in the following manner: Obtain a small fitting called an ‘Adaptor’ from one of the electrical fitting dealers (this costs about 1/6), also a spare lamp holder (2/-) and a few yards of No 18 insulated wire. Make the connections which are clearly shown. The current will then pass through the lamp and battery in ‘series’, and providing you connect the Positive of battery to Positive of supply and leave on for long enough—known by the battery ‘gassing’ strongly—the charging will be very effectively performed. You will require to find out which is the positive wire of the supply (the positive of battery being always marked with a + or painted red). This is a simple matter. Obtain two scraps of sheet lead, clean them bright and place them in a glass or jar so that they touch each other; then pour into the jar some dilute acid (sulphuric, say, out of the battery—but be sure to put it back; then fasten the the wires A and B, one to each lead plate, and switch on the current. In a few minutes the lead plate connected with the positive wire will turn brown and, provided you always put the adaptor into the holder on the same side, this wire will always be positive. Remember, however, that the current supply must be direct and not an alternating one. The third method is perhaps the one that will commend itself to the average motor cyclist, au because by adopting it he is independent of agents (some of whom ask fancy prices for charging), and he can always rely on his