1890

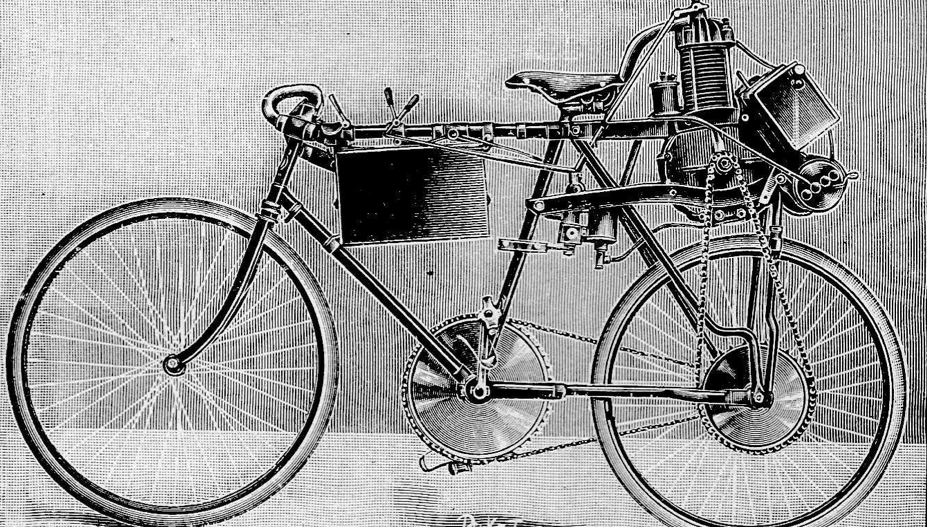

IN THE FACE OF the 2/4mph urban/rural speed limit Edward Butler gave up on his Petrol-cycle. He wrote in the magazine The English Mechanic: “The authorities do not countenance its use on the roads, and I have abandoned in consequence any further development of it.” It was a brave attempt that, had it not been scuppered by ridiculous legislation, would have put Britain at the forefront of the motor cycle (and automobile) revolution from the beginning.

KITCHEN GOODS specialist John Marston and Co expanded its output to include bicycles. As we’ll see in 1912, this was A Good Thing for motorcyclists.

HERBERT AKROYD Stuart patented a compression-ignition engine, a clea189r three years ahead of that nice Mr Diesel.

KARL BAYER developed the large-scale production of aluminium from bauxite.

IN JAPAN EISUKE Miyata set up a gun factory where he also made Asahi bicycles, closely based on the British Cleveland.

1891

EADIE MANUFACTURING renamed its Townsend bicycles Enfields to mark an arms deal with the Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield. The Enfield Manufacturing Co, soon renamed Royal Enfield, was set up to market them. In 1893 the firm adopted a familiar slogan: ‘Built Like a Gun—Goes Like a Bullet’.

MAYBACH DEVELOPED a spray carburettor, though surface carbs would be more common for years to come.

1892

HANS GEISENHOF, who had worked with Karl Benz, designed a two-stroke petrol engine for the Hildebrand brothers. They fitted it into a bicycle frame but it was gutless so he and Alois Wolfmuller built a 1,489cc, water-cooled four-stroke parallel twin that developed 2½hp at 240rpm. The weight of this engine snapped the frame so the brothers used the frame from their 1889 steamer.

RUDOLPH DIESEL started development of a compression-ignition engine and was awarded a patent the following year.

JD ROOTS DEVELOPED a water-cooled, two-stroke trike featuring shaft drive and exported its entire output to France to avoid Britain’s bonkers legislation.

COMPTE ALBERTE de Dion, Georges Bouton and Charles Trepardoux had been making successful steamers for a decade when, following a visit to the Paris Exposition where they saw the Daimler engines, De Dion and Bouton decided internal combustion was the coming thing and began serious work on a petrol engine at the expense of their steamer projects. Trepardoux, a confirmed steam-head (‘vaporiste’, en Francais), walked out in disgust with the parting shot, “How can a motor function on a series of explosions?” His departure must have caused a row in the family, particularly when De Dion and Bouton were proved right.

1893

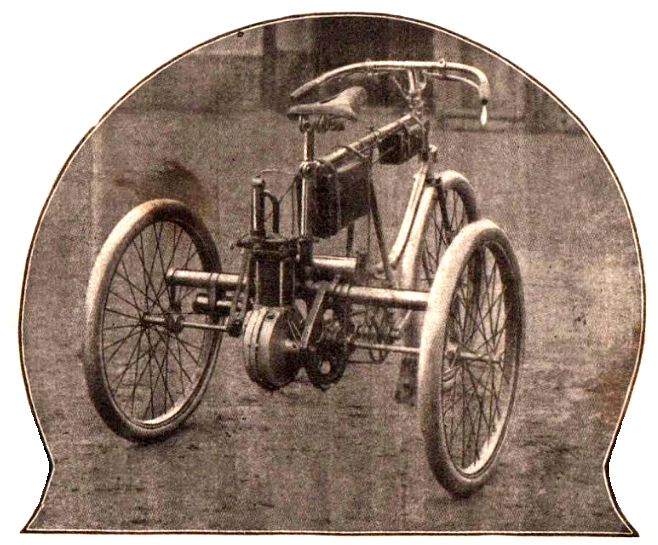

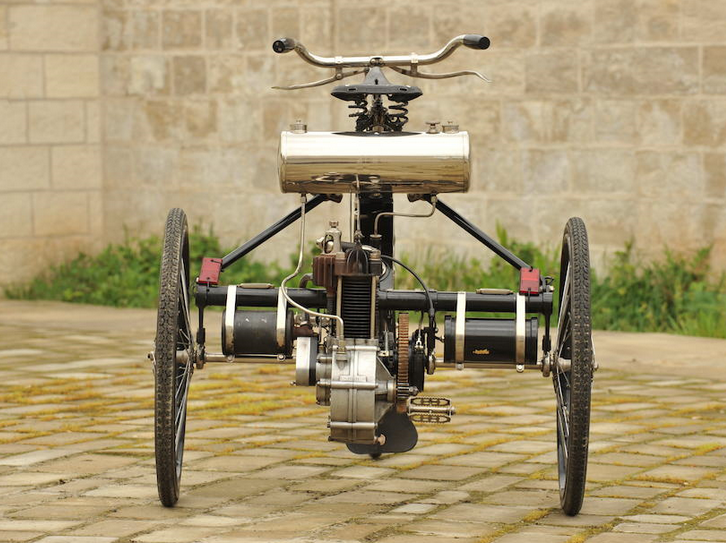

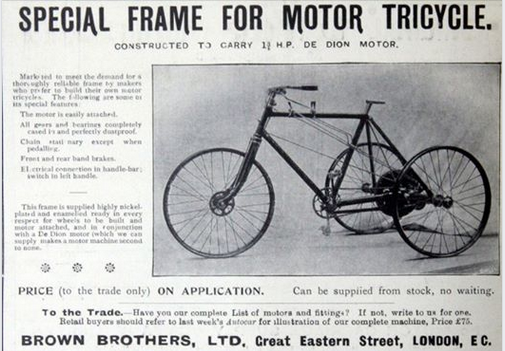

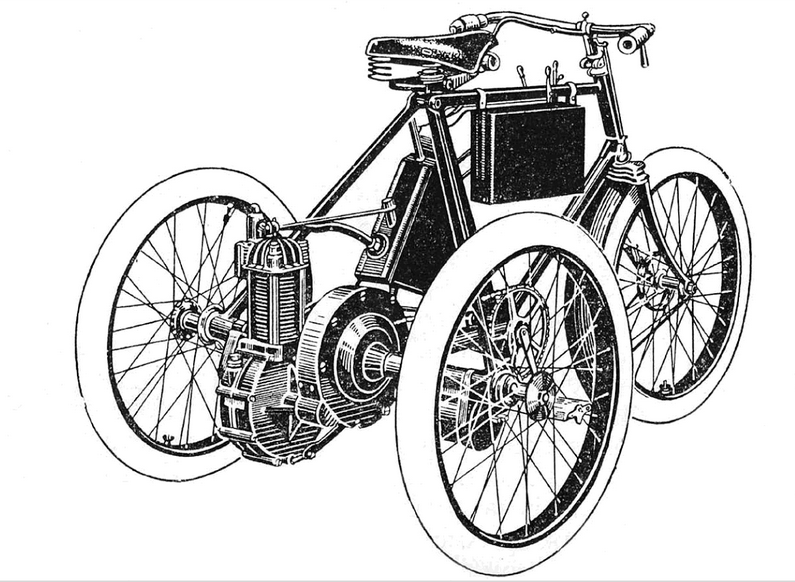

GEORGES BOUTON produced a 138cc single inspired by the Daimler engine in the 1885 Einspur but he found that it ran much smoother at higher revs. So while the Daimler engine ran at 250rpm and the Daimler at 750rpm, the De Dion Bouton ran at 1,500-2,000rpm and in trials reached 3,500rpm. Instead of hot-tube ignition the new ‘high-speed’ engine had a 4V battery/coil system with a contact breaker. Unlike many later engines it also boasted a detachable cylinder head; power output was about ½hp. De Dion and Bouton mounted their engine at the back of a pedal-powered Decauville trike which became a great success, running on the new tyres being mass produced by brothers Andre and Edouard Michelin. They also sold De Dion Bouton engines to power motor cycles, trikes and even an airship. This was the practicable proprietary engine that, combined with the many safety bicycles coming onto the market, launched an industry and, let it be said, an obsession.

ANGLO-GERMAN Frederick Simms, a pal of Daimler’s, bought the British rights to Daimler engines.

IN THE USA A bicycle was fitted with a rear-mounted horizontal twin two-stroke by one EJ Pennington – a second-rate designer but a first-class conman (‘premier division’ would be more accurate; he thought big. Take a look in the Galimaufrey for some of his scams).

A GERMAN CALLED von Mayenberg built a two-speed steamer with fuel for the burner carried inside the frame.

COTTON REINFORCING cords were moulded into bicycle tyres for tougher sidewalls.

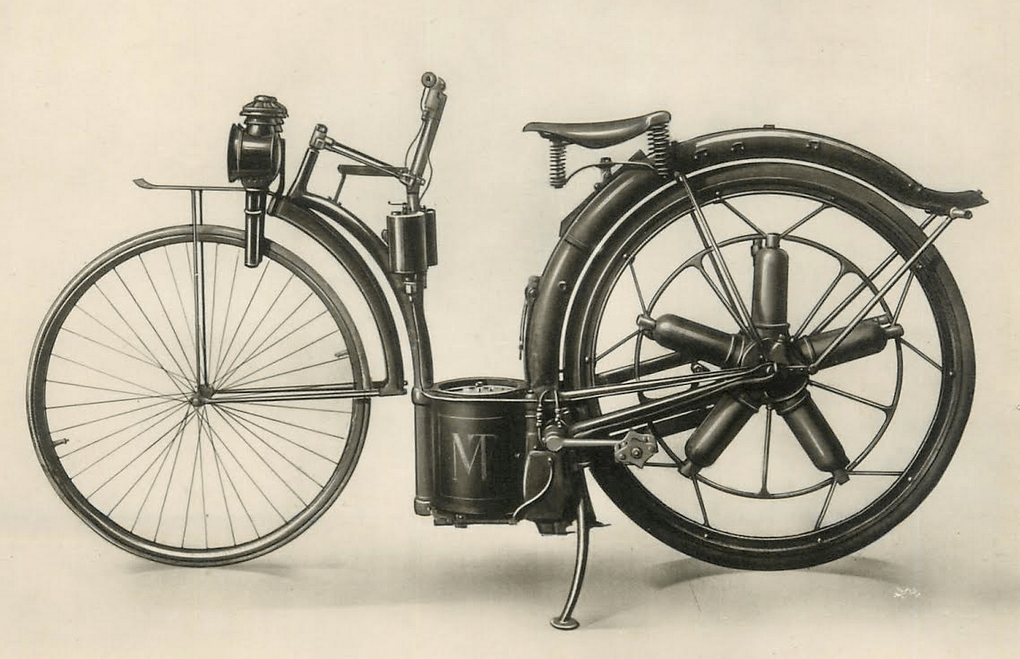

HAVING POWERED A TRIKE with his five-pot radial engine in 1887, Félix Millet built a motor cycle. This time the engine was in the rear wheel; the crankshaft served as the wheel spindle. Revolutionary features included a clutch (operated by back-pedalling, which also applied a brake), a semi-automatic frame lubrication system, mechanically operated valves, what was probably the first motorcycle centre stand (well, yes, it was a prop stand but it was in the middle) and an ‘elastic’ rear wheel which was an early attempt at suspension. The 1,924cc engine was rated at ¾hp at 180rpm giving a claimed top speed of 35mph. Fuel consumption was about 110mpg. Ignition was by a coil and lead-acid battery rather than the Hildebrand & Wolfmuller’s hot tube. Fuel was carried in the rear mudguard; a surface carb and air filter were fitted between the wheels. Millet sold the rights to Alexandre Darraq who planned to put the bike into series production; it was one of 17 starters (out of 102 two, three and four-wheeled entries) in in the Paris-Rouen Trials, generally accepted as the world’s first motoring contest. The Millet retired early in the race, production plans were dropped and Millet died in poverty.

ENRICO BERNARDI, having registered the first patent for an Otto-cycle engine in 1882, also produced a petrol-powered two-wheeler, although in this case the engine was mounted in a trailer which pushed the bike.

1894

HEINRICH HILDEBRAND and Alois Wolfmuller patented the bike they’d been working on since 1892: a 1,428cc/2½hp water-cooled four-stroke twin (with hot-tube ignition and surface ‘bubbler’ carb) which would become the first motor cycle to sport pneumatic tyres, thanks to a deal with Dunlop. Following steam-locomotive practice the conrods drove the rear wheel so there was no crankcase and no belt, chain or shaft rear drive. Neither was there a flywheel; instead elastic straps helped the pistons back down the barrels. Claimed top speed was 25mph; brakes comprised a steel ‘spoon’ pressing against the front tyre and a pedal operated ‘sprag’ rear brake—a lump of metal that could be forced down against the road surface as an anchor of last resort. It was the world’s first motor cycle to go into series production, made in Munich by Motorfahrrad-Fabrik Hildebrand & Wolfmuller in a factory the brothers had purpose built for the project with 1,200 assembly workers; they also used many local engineering firms for components. ‘Motorfahrrad’ translates as ‘motorcycle’; an early use of the term. They even sent a demo model to Paris in a bid to win export business.

PROFESSOR ENRICO Bernadi of Verona built a four-stroke, water-cooled ohv 265cc single-cylinder engine and named it the Lauro. It was too bulky to fit in a bicycle frame so Bernadi mounted it in a monowheel trailer. The engine turned the trailer wheel and the trailer pushed the bike. Control was via a rubber bulb which controlled a carburettor diaphragm.

HARRY LAWSON’S Motor Manufacturing Company (MMC) company bought the British rights to De Dion engines.

THERE WERE 102 two, three and four-wheeled entries for the Paris-Rouen Trials, the world’s first motoring contest, of which 17 started. The following year there were about the same number of entrants for America’s first race, from Chicago to Waukegan. Two made it to the start line so they re-ran the race but only six vehicles turned up.

1895

JOHN KNIGHT BUILT “the first petroleum carriage for two people made in England”. He was stopped for speeding up Castle Hill near Farnham, Surrey and collected the first English speeding ticket. His four sons all drove it until 1903 when the minimum driving age of 17 was introduced—with Knight Snr’s encouragement the lads got stuck in and built themselves a wooden-framed trike.

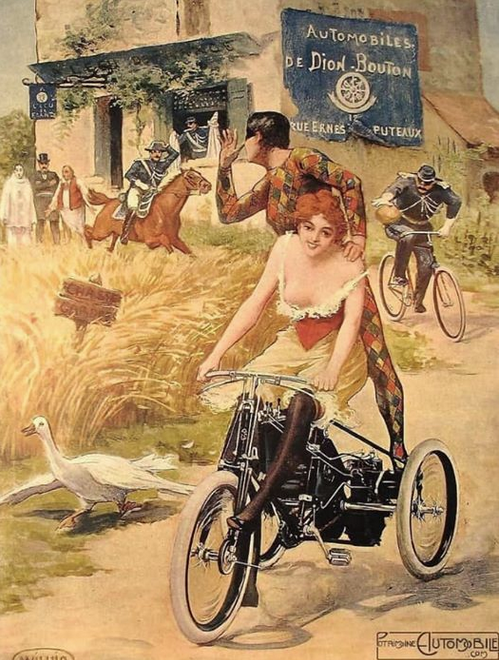

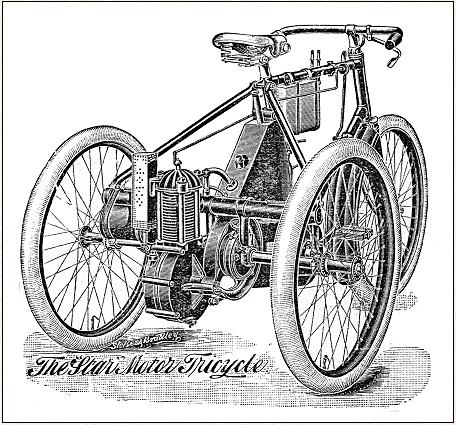

THE DE DION-BOUTON engine, enlarged to 185cc (1¼hp) and then to 211cc (1½hp), but still weighing less than 40lb including the battery and petrol tank, was mounted at the back of a Decauville pedal trike which was shod with the new tyres being mass produced by brothers Andre and Edouard Michelin. De Dion-Bouton were soon selling their own trikes and engines as fast as they could make them. The tricycle (with a 920mm track) was chosen because, according to the good count, “a bike appeared too fragile for this purpose”. It would be the most successful motor vehicle in Europe until 1901, with about 15,000 copies sold,

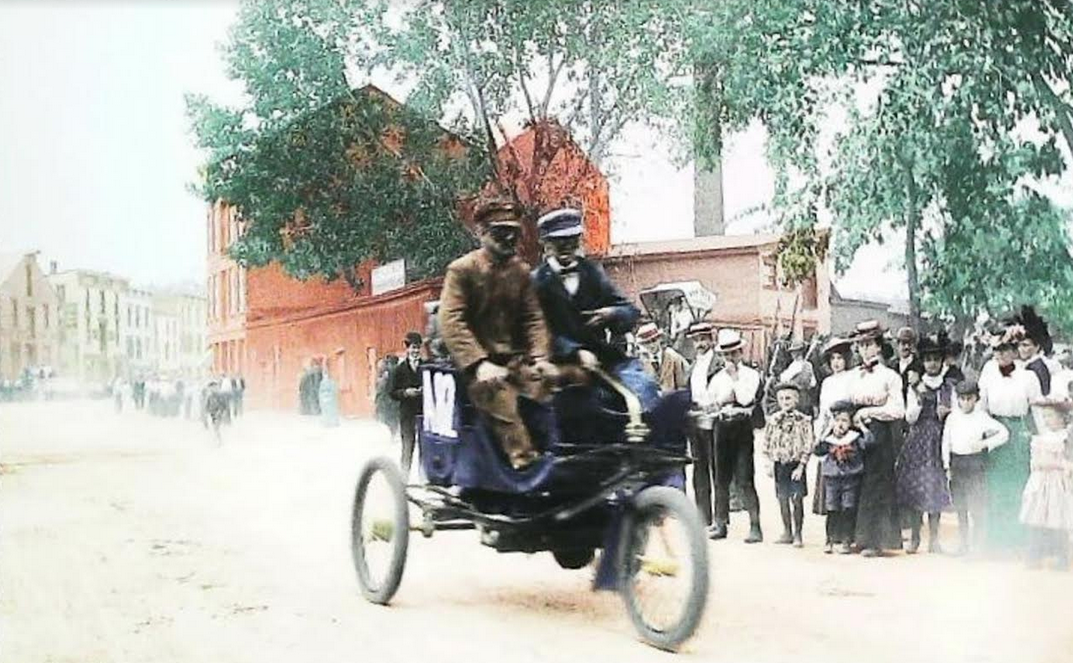

IT ALL LOOKS TRES JOLI but judging by the caption on this card, trikes were not universally popular in La Belle France…

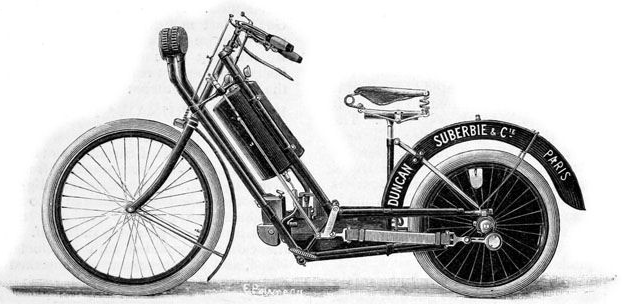

SIEGFRIED BETTMAN’S partner in Triumph, Mauritz Schulte, considered producing H&Ws under licence. He imported one for testing but the idea went no further. However the French manufacturer Duncan-Superbie & Co produced bikes developed from H&Ws which they marketed as Petrolettes (presumably to mollify painful French memories of the 1870-1 Franco-Prussian war). Wolfmuller took a brace of H&Ws to Italy for its first bike/car race; they came 2nd and 3rd over a rocky 62-mile course behind a Daimler car. Two Petrolettes were among the six bikes that entered the 732-mile Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race. None of them completed the course but a Petrolette, ridden by Georges Osmont, was the only two-wheeler to complete the first leg from Paris to Bordeaux, in 45 hours. The first car home was a Panhard et Lavossar (driven by Emile Levassor), in 48hr 48min, ahead of three Peugeots. However the first two finishers were ineligible for the cup as they were two-seaters and the rules called for at least three seats. A report for the French Institute of Civil Engineers predicted that motorcycles would be no more than a curiosity.

THE HONOURABLE EVELYN ELLIS ordered a left-hand-drive motor car to be made to his own specifications from the Paris firm of Panhard-Levassor, powered by a 709cc Daimler engine developing 3½hp at 7000rpm. The car was driven from Paris to Le Havre, shipped to Southampton and by train to Micheldever station in Hampshire. From there, on 6 July, Ellis drove home. His passenger, Frederick Simms (who we’ll be meeting again) described the journey in the Saturday Review: “We set forth at exactly 9.26am and made good progress on the well-made old London coaching road; it was delightful travelling on that fine summer morning. We were not without anxiety as to how the horses we might meet would behave towards their new rivals, but they took it very well and out of 133 horses we passed only two little ponies did not seem to appreciate the innovation. On our way we passed a great many vehicles of of all kinds (ie horse-drawn), as well as cyclists. It was a very pleasing sensation to go along the delightful roads towards Virginia Water at speeds varying from three to twenty miles per hour, and our iron horse behaved splendidly. There we took our luncheon and fed our engine with a little oil. Going down the steep hill leading to Windsor we arrived right in front of the entrance hall of Mr Ellis’s house at Datchet at 5.40, thus completing our most enjoyable journey of 56 miles, the first ever made by a petroleum motor carriage in this country in 5 hours 32 minutes, exclusive of stoppages and at an average speed of 9.84 mph. In every place we passed through we were not unnaturally the objects of a great deal of curiosity. Whole villages turned out to behold, open mouthed, the new marvel of locomotion. The departure of coaches was delayed to enable their passengers to have a look at our horseless vehicle, while cyclists would stop to gaze enviously at us as we surmounted with ease some long hill.” Ellis was deliberately testing the law that required all self-propelled vehicles on public roads to travel at no more than 4mph and to be preceded by a man waving a red flag. He was not arrested and, as we’ll see, the Act was repealed in 1896.

THE CHICAGO Times-Herald coined the term ‘moto-cycle’ to supersede ‘horseless carriage’ when organising the first automobile race in the USA with $5,000 in prizes. There were 83 entrants but only six showed up on the day. After a gruelling 54-mile run a Duryea, built and driven by J Frank Duryea, crossed the line in 7hr 53min at an average speed of 7mph to win $2,000. Runner up, 90 minutes later, was a Benz—the rules stated: “In the event the first prize goes to a vehicle of foreign manufacture, the most successful American entry will receive this prize”. The Sturges Electro Motocycle won $500 although it was abandoned after 12 miles. The GW Lewis Motocycle was awarded $150 “…for friction driving device and brake and a reduction gear for increasing speed.”

I’M GRATEFUL TO my amigo Francois for recording the first known motor cycle race (in ‘Images of Yesteryear’). Italy was first past the post when two (sadly unidentified) bikes joined three cars in a 70-mile race from Turin to Asti and back. We don’t know who won, or indeed if anyone completed the course—but they tried. Viva l’italia! Within weeks the French had a go when two bikes started in the ambitious 732-mile Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race. The winning car finished in 48 hours; neither bike survived the course.

1896

AT LAST! HP SAUCE ARRIVED to complement the bacon sandwiches (and baked beans) which have always sustained motorcyclists, courtesy of Fred Garton who cooked it up in his pickle factory in Basford, Nottingham. And now it’s made overseas. Shameful.

EDWARD BUTLER sold the patent rights to his Petrol-Cycle to Harry Lawson, who manufactured its advanced engine to power boats, and broke up his machine for scrap but, as the Red Flag Act had been repealed, Butler and his wife were able to make at least one last ride in the Petrol-Cycle on the roads of Erith—he wrote of reaching a speed of 12mph— before selling it as 163 pounds of scrap metal. (The weight of the machine was 280 pounds so maybe the “very compact motor” was salvaged.)

FROM THE BENDIGO ADVERTISER, in the Aussie state of Victoria: “A new terror is to be added to our thoroughfares. This is to take the shape of a motorcycle, to be worked by oil and to be capable of a record pace. It is to be provided also with pedals so that the rider can first take his fill of exercise, then shield his feet from the pedals and enjoy all the pleasures of rapid locomotion. Nor is this all, the motor bicycle is to be built for either one of two passengers, to be followed by the motor tricycle, on which three people may find comfortable seats. The thoroughfares are dangerous enough as it is what, with trams and other conveyances and with bicycles shooting sharply round corners without even that pre-emptory tinkle of the bell that is popularly supposed to be one of the regulations for cycle traffic. But what will they be with the motorcycles. Then again, ‘horrors are likely to be piled on horrors’ head’ by the appearance of the electric motor, which is gaining so much popularity in the old country , but, thank heaven! it requires the passing of an Act of Parliament before these can be used on our public roads, and Parliament is not likely to enter on the consideration of fresh legislation for a long time to come. For which relief much!”

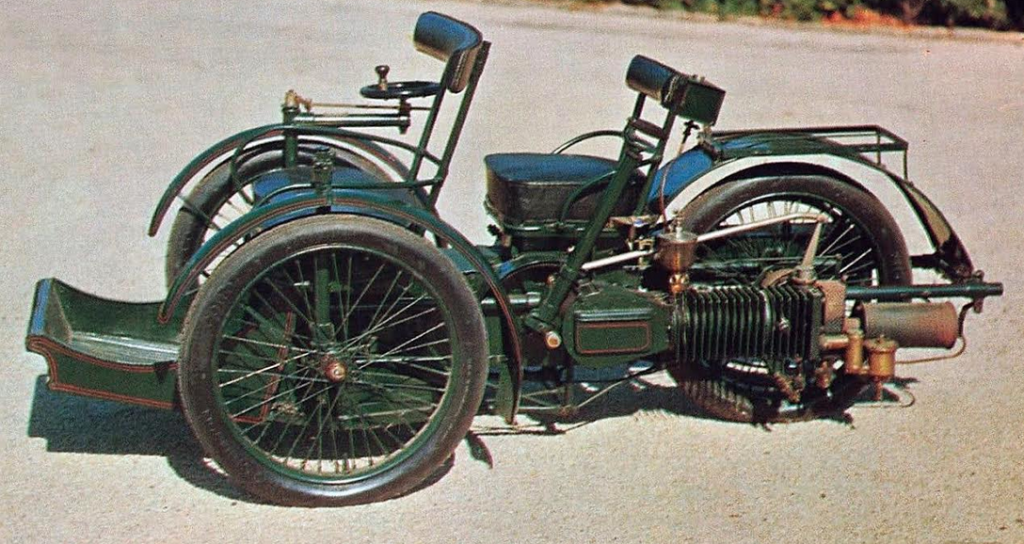

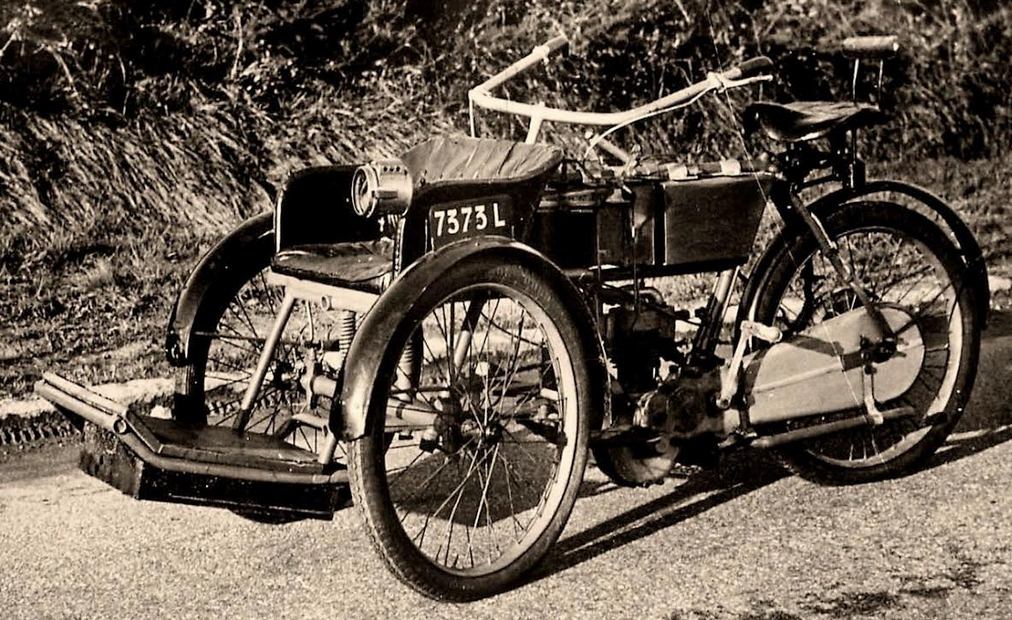

IN LE MANS LEON BOLLÉE and his dad, Amédéé, patented and built a 650cc 2½hp tricar marketed as the Voiturette—the passenger seat position earned it the nickname ‘Tue Belle-mère’, ‘Mother-in-law killer’. The border between motor cycles and automobiles was blurred but Bollée called his company Léon Bollée Automobiles and, although the Voiturette won the 1897 Paris-Dieppe and Paris-Trouville races, he switched his attention to four-pot four-wheelers.

WEALTHY ENTHUSIAST and Mayor of Tunbridge Wells Sir David Salomons co-hosted the first ever motor vehicle show with Frederick Simms. There was a grand total of five exhibits including two cars, a fire engine, a steam carriage and a trike. Among the spectators was one Harry J Lawson who clearly saw a great future for petrol power —he bought the British rights to Daimler engines from Frederick Simms and made a serious attempt to dominate the nascent British industry.

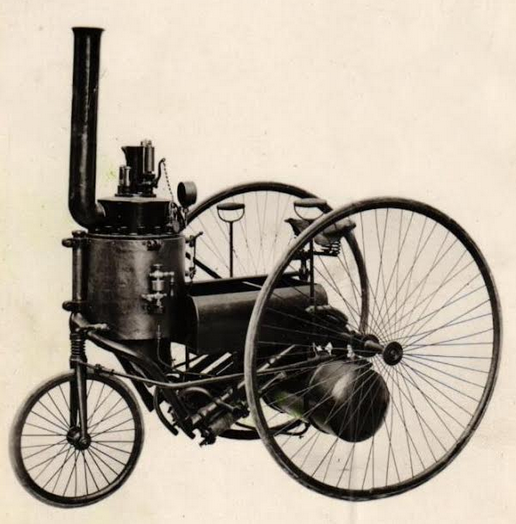

WITH THE REPEAL of the Locomotion Act the British speed limit was raised from 2mph in towns and 4mph in the country to a breathtaking 12mph. On 14 November this was marked by the Emancipation Run from the Hotel Metropole in Whitehall to its namesake in Brighton. Lord Winchelsea symbolically ripped a red flag in two at the start. A De Dion-engined Beeston trike assembled in Austria (to avoid local import duty) was the only British trike to complete the run (three Bollee trikes were specially imported from France for the event). Two Beestons were subsequently sent to Sandringham where one was ridden by the Duke of York, later George V. A Monsieur Lormont entered a steam-powered bike as the Dalifol, and therby hangs a tale. He worked for the Hildebrand brothers who were busy with the Hildebrand & Wolfmuller petrol-powered motor cycle, and his steamer was actually the Hildebrand steamer (which you might have read about in 1889). The Dalifol/Hidebrand failed to make it all the way to Brighton and was abandoned at Southern Railways’ Newhaven depot, and there it stayed for the next 44 years. In 1940, finally accepting that M Lormont wasn’t coming back, the railwaymen donated the steamer to the Science Museum of London. It was exhibited as ‘the Brighton Steamer’ until 1956 when Heinrich L Hildebrand, son of Heinrich Hildebrand, identified it as the prototype built in 1889 by his father and uncle. Charles Jarrott, who was on the run, recalled: “The effect of the run on the public was curious. They had come to believe that on that identical day a great revolution was going to take place. Horses were to be superseded forthwith, and only the marvellous motor vehicles about which they had read so much in the papers for months previously would be seen upon the road. No one seemed to be very clear as to how this extraordinary change was to take place suddenly; nevertheless, there was the idea that the change was to be a rapid one. But after the procession to Brighton everybody, including even horse dealers and saddlers, relapsed into placid contentment, and felt secure that the good old-fashioned animal used by our forefathers was in no danger of being displaced. It was, however, the beginning of the movement, and the start in England of the great modern era of mechanical traction on the road.”

This photo isn’t blurry—this is the Dalifol/Hildebrand and, being a steamer, it’s steaming.

THE FIRST LONDON show for “horseless carriages” was held at the Imperial Institute in South Kensington under the auspices of Harry Lawson’s Motor Car Club.

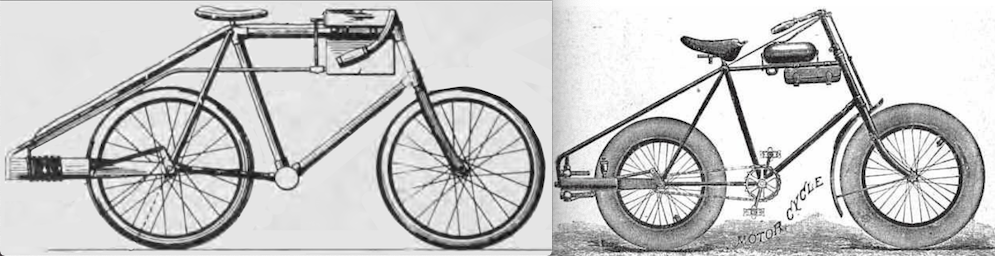

BAYLISS THOMAS and Co of Coventry had been making penny-farthings since 1874; the firm became Britain’s first motorcycle manufacturer, fitting De Dion engines over the front wheel of the safety bicycles. It was marketed under the Excelsior banner.

A PATENT IN the name of Gustav Mees mentioned desmodromic valves. Instead of springs, vales were to be closed, as well as opened, by cams.

THE 1½HP ENGINE ON the Munich-made Heinle & Wegelin replaced the downtube years before Joah Phelon (of P&M) patented the idea. It also had one of the first Bosch mags and shaft drive. Evidently a pillion seat could be fitted; trailers were offered to carry people or luggage and an ambulance version was available. One was driven on the streets of London

LUDWIG RUB, A Munich shoemaker, designed the Heigel-Wegulin, a shaft-drive motor cycle which used the engine and fuel tank as part of the (conventional bicycle) frame. Advanced features included a mechanically operated inlet valve. It went into production and was exhibited in Britain but high production costs killed it off.

THE COVENTRY MOTOR Company (part of the Harry Lawson empire) began to produce motorcycles on the same site as Beeston and Humber. The Autocar reported: “The first practical motor cycle built in this country was completed last week when Messrs Humber and Co finished a bicycle fitted with a Pennington 2hp motor, made at their works in Coventry [and displayed it at the Horseless Carriages Exhibition]. The machine was…tried in the presence of witnesses, and the speed developed was said to have varied from 30-40mph.” Which goes to show how much they knew, because the Kane-Pennington (it was funded by Thomas Kane of Racine, Wisconsin and based on Kane’s patent) would have seized after a few hundred yards for lack of cooling fins, and was a pile of junk despite its “long-mingling spark” and “inpenetrable” balloon tyres. Pennington came to England at the invitation of Humber boss Harry Lawson—a sharp cookie in his own right—and relieved him of £100,000 for the rights to this hopeless engine and some other dodgy patents. Pennington’s story is a fascinating one which is covered in the Gallimaufry in all its grisly detail. In truth he had little to do with the evolution of the motor cycle and everything to do with conning lots of people out of lots of money on both sides of the Atlantic. His vehicles were praised to the skies in Autocar; but the launch editor of Autocar was later sacked for “undisclosed financial dealings” with Pennington. Meanwhile Humber produced its own 3hp engine which, fitted to Humber’s pioneering diamond-framed safety bicycle, made Humber the country’s first motor cycle manufacturer.

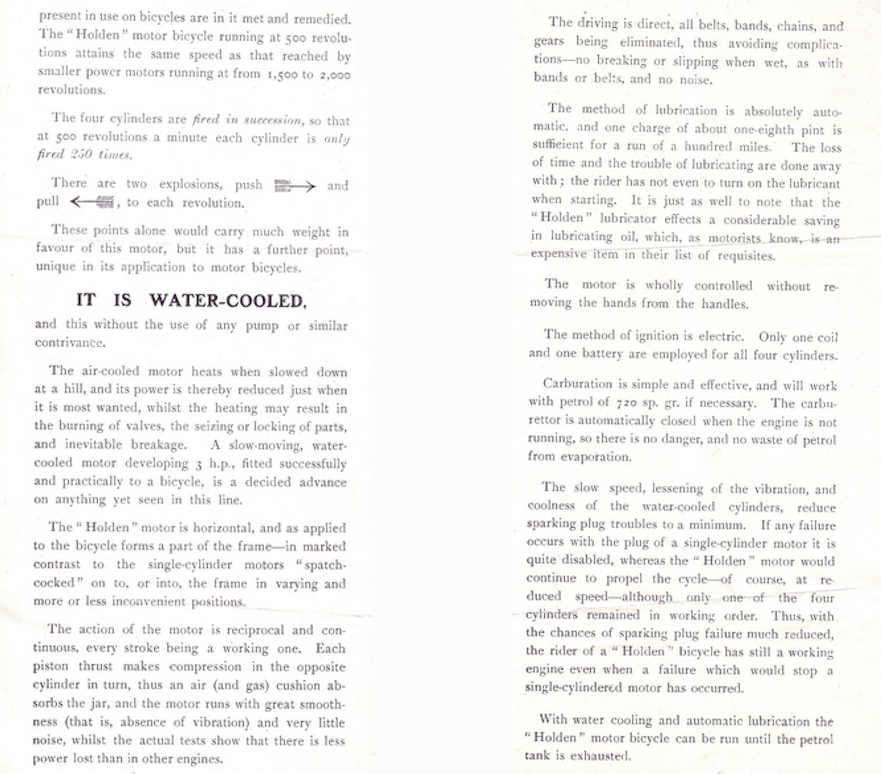

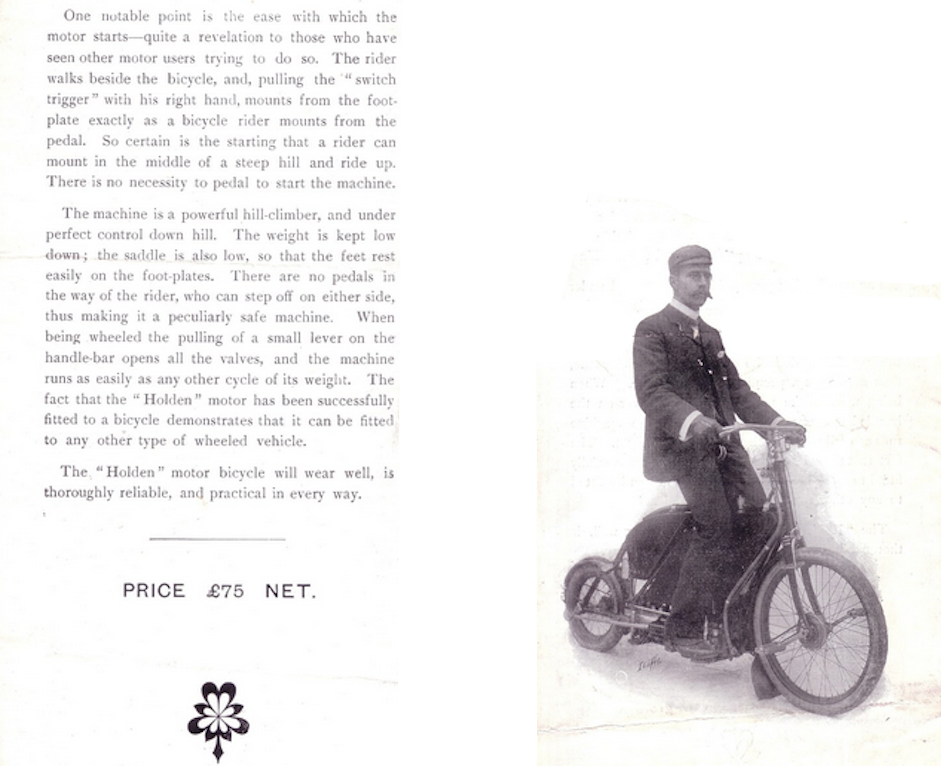

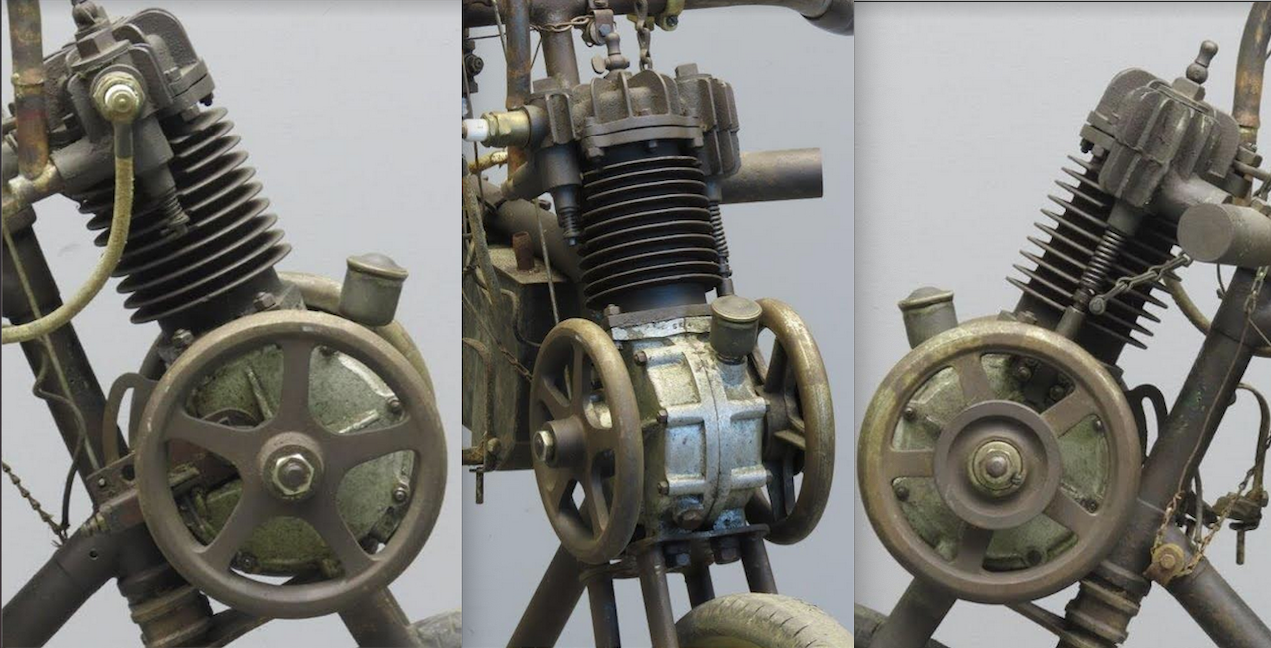

MAJOR (LATER BRIGADIER-GENERAL) Henry Capel Lofft Holden of the Royal Engineers produced the world’s first four-pot motor cycle. Its water-cooled 1,047cc engine developed a claimed 3hp at 400rpm. Like the Hildebrand and Wolfmuller (and indeed the ‘opeless Pennington) railway-style conrods drove the rear wheel; the exhaust was routed through the fuel tank because, as we all know, warm petrol vapourises quicker. Top speed was about 25mph. The Holden was built around a modified Crypto Bantam bicycle frame. The Crypto Bantam was a development of the penny farthing with gearing built in to the front hub to allow a smaller front wheel. It was soon replaced by the safety cycle.

The Holden four is clearly a motor cycle rather than a motorised bicycle. This contemporary sales brochure makes fascinating reading…

ERWIN ROSS Thomas of Buffalo, NY added De Dion engine kits to his output of Cleveland bicycles.

IN PARIS HIPPOLYTE Labitte built a tidy little 198cc ¾hp engine and offered it to Russian emigrees Michel and Eugene Werner to replace the electric motors that powered the kinetoscopes (film projectors) they were importing from the Edison company. Michel fitted one over the front wheel of a bicycle as a publicity stunt. It drove the front wheel via a twisted rawhide belt that slipped hopelessly in the rain. It was top heavy and, when it skidded on wet, greasy cobblestones, tended to burst into flames because of the spirit burner that heated its hot-tube ignition. But there wasn’t much competition and a dozen had been sold within a few months.

HERE’S A TREAT, dating from the early years of the 20th century—the nearest thing you’ll find to a roadtest of a first generation over-the-front-wheel Werner: “She cost me thirty shillings, did my 1½hp front- drive Werner, back in 1903, and I shall never be able to buy so much fun for the money again. A schoolboy is not over plentifully supplied with cash (or should not be), and the indulgent cycle-maker who let me have her accepted half-crown instalments, at irregular intervals. Even then she was a wondrous antique, but her tyres (French racing Dunlops) were thoroughly good, her frame strong enough for a modern twdn, and her engine was a splendid job. That was a proud moment when, after an overhaul lasting weeks (needless to say the price included the right to do all the necessary tinkering in the seller’s workshop), we bore her down the steps. I had done my best to transform her into the outward semblance of a speed monster: the saddle had been removed, and a rickety luggage-carrier intended for a cycle substituted, liberally padded on top, the exhaust arrangements and pedalling gear scrapped, and in the place of the latter a piece of broomstick (wrapped with inner tube to conceal its domestic origin) did duty for footrests. (One had to mount gingerly.) I sat astride her in the road, regarding thef engine with affection and pride. Please remember that I was sixteen, she was my very own (for had not the first half-crown been paid?), and I had never been on a power-driven machine before. The kindly cycle-maker and his apprentices pushed lustily. We swayed down the road in wide arcs. She fired. Oh, irrecoverable moment! Never was such a bark as that baby engine possessed. They lodged complaints in the Maida Vale flats about me, because I would run up and down half the day wondering if it wasn’t really possible to do something in the way of tuning on a surface carburetter. Little Werner and I careered down the road, keep- ing an eye out for people who might know us, and be impressed. We rounded the first comer successfully, but on straightening up side-slipped on a tramline, and went down with a slam. (That was her first naughty trick, and her last: with the engine over the front wheel the little machine steered perfectly, and could be ridden ‘hands off’.) I recovered my steed: a little acid spilt from the accumulator and some petrol (tenpence a gallon, so it didn’t matter) was all that was lost, and we ran soberly round the houses back to where the expectant staff awaited us. That was the beginning of a jolly time. A man named Arthur Cummings, who was very prominent as a speed exponent on the 70×70 class, used to haunt Paddington track near by. I

showed him the Werner. He was too well-mannered to laugh, and took her and my efforts to make her do thirty miles an hour seriously. We bought a drill, and started to tune her. The air intake to the engine was governed by a revolving sleeve on the handle-bar, and the neat mixture was led from a surface carburetter forward of the tank up the head column to the handle-bar lug, where the engine was bolted on. Drive was by twisted round belt (and some of you think a V belt is troublesome!) to a pulley on the front wheel, and you carried your oil in a little glass cup on the crank case. Coil and accumulator conspired together to defeat dull care: one or the other or both always needed attention. The band brake on the back wheel was splendidly efficient—until one day it broke; after that I remember I used to stop by dragging my feet on the ground and using the compression. (There is undeniably a special providence for mechanically-minded schoolboys). We removed the gauze from the induction pipe, and while this ran her consumption up terribly, it was worth it. I ran her to Brighton and back in days when none ventured on pedalless machines, and she took everything except the last stretch of Handcross. There her proud owner had to slip off and run; but she was forgiven, for it was a plucky climb for an engine aged and so small. By this time we were regular habitues (sixpence admission) at Paddington track. One day we borrowed a back wheel from a racing push-cycle, with a fabric-sided tyre about the diameter of a lead pencil, and a slender wood rim and cobweb spokes. We inserted this in the back forks, gave Werner an extra swig of oil, and issued a formal challenge to a neighbouring youth who owned a wheezy 3hp Kelecom. It was a Homeric struggle. I flattened myself along the top bar until I could flatten no more, sprayed with hot oil, and unutterably happy because the dreaded Kelecom was well behind. It was a famous victory, but as she crossed the line poor Werner seized. Her piston had gone. We disembowelled a worn-out Yankee ‘Thomas’ that we had access to. Some brisk work with a file, and the old rings, and the little engine was got going again—a thought metallic in the exhaust at speed, but serviceable. I always feared it was the drilling we did on that piston: we used much enthusiasm on the job, but little discretion. Poor little ‘bus. I suppose her rusty bones are lying in some forgotten corner. Still, I think in her time she gave a keener pleasure than my little opposed twin, now waiting in the shed, eager and twice as speedy, can ever give.” RHB.

BICYCLE MANUFACTURER Alexander Leutner & Co of Riga produced five trikes powered by De Dion Boutin engines. Leutner was a motoring pioneer: he comp[eted in the first motor race in St Petersburg, in the 1890s, had tested-driven a Hildebrand and Wolfmuller and was chums with Gottlieb Daimler, who had visited him in Riga. He had studied in Lyon, Aachen and Coventry.

A HILDEBRAND & Wolfmuller made a demo run in Tokyo—the first motor cycle to be seen in Japan. But that year its German and French operations collapsed. H&Ws had been sold at below cost price, they were unreliable and buyers demanded their money back. An H&W was raced at the Crystal Palace where it was said to have reached 27mph, but only on level ground. Major weaknesses were a tendency to skid and problems climbing even gentle slopes.

IN THE 171-MILE race from Bordeaux to Agen and back a De Dion trike came 4th, ahead of a Hildebrand & Wolfmuller. In a race from Paris to Mantes six DeDions finished 1-2-3-4-6-8 (with a Hildebrand & Wolfmuller 7th). De Dion started to sell engines to all comers.

PEUGEOT, HAVING made steam cars since 1889, began to make petrol engines of its own design.

NO SOONER HAD petrol-engined motor cycles appeared than they were used as ‘pacers’ for racing bicycles (you’ll find a fine selection of pacers at the start of the picture melange). Those pioneer petrol burners were unreliable so Colonel Albert Pope, the man behind Pope Columbia bicycles, decided to try steam. He commissioned Sylvester Roper, now 72, to build him a steam-powered pacer in a modified Columbia bicycle frame (you’ll find details of Roper’s first steamer back in 1868). Roper duly fitted an improved steam engine rated at 8hp; all-up weight was 150lb with a range of some 25 miles. Its range was only seven miles but the reckoned it could ‘climb any hill and outrun any horse’. American Machinist magazine reported: “The exhaust from the stack was entirely invisible so far as steam was concerned; a slight noise was perceptible, but not to any disagreeable extent.” Roper was asked to demonstrate his ‘self propeller’ at the Charles River velodrome, a banked concrete bicycle racing track. Having paced the racing cyclists he raced against them and was timed at over 40mph. Sad to say at this point he was seen to swerve off the track. He was found to have suffered a heart attack and died in the saddle.

FROM A DAILY newspaper: “The ‘horseless carriage’ race from Bordeaux to Paris, which was held recently, displayed how remarkably electricity and other motive-powers for light vehicles have progressed. Never had such a novel sight been witnessed, and the interest taken in the event shows plainly how people regard the importance of modern appliances for speed purposes. The petroleum motor bicycle was one of the vehicles entered for competition, and by no means the least interesting. Many people consider that the motor-driven cycle is the cycle pf the future, while others assert that the physical exertion necessary for propulsion purposes gives the real charm to cycling. Be that as it may, the motor bicycle is an accomplished fact.”

IRISHMAN ERNEST MORNINGTON BOWDEN was granted a patent for the ‘Bowden mechanism’. Thanks for the cables, Ernie.

LLOYDS ISSUED the first motor insurance policy.

THE GENEVA STEAM bicycle was made by the Geneva Cycle Company, of Geneva in Ohio. The naptha-fired steam engine was based on a design by Lucius Copeland. A modern replica was found to be capable of 12mph, but maintaining a head of steam at that speed was not easy.

1897

THE FIRST ‘MOTOR BICYCLE’ race in England took place at Sheen House. Charles Jarrott rode against HO Duncan, both on 1¾hp De Dions. They had to be push-started; the pedals were used purely as footrests. There was no adjustment on the flat drivebelts which had to be smeared with “a gluey sticky form of compound” to ensure grip.

FREDERICK SIMMS sent a De Dion-Bouton trike to Robert Bosch to be fitted with a magneto. This led to the development of the high-voltage mag; Simms set up a UK Bosch agency (and LATER helped set up what would become the RAC).

IN 1899 THE STEVENS BROTHERS, George, Jack, Joe, and Harry set up the Stevens Motor Manufacturing Company in Wolverhampton to produce petrol engines. Harry was interested in powered transport and fitted a US-made Mitchell engine that had been acquired for use as a stationary engine into a BSA bicycle that was lying around the works. Ignition was by accumulator and trembler coil; a metal rim was fitted to the rear wheel for a belt drive. The engine wasn’t too reliable but it attracted the attention of their neighbour William Clark, who ran the Wearwell Cycle Company. Believing they could improve on the Mitchell, the Stevens boys had some castings made by a firm in Derby and, in their spare time, made a reliable, efficient (for its day) 1¾hp engine incorporating a carburettor made from an old mustard tin. Stevens already supplied Clark with spokes and fasteners; before long they were also supplying him with engines.

BEESTONS WERE AMONG eight motor cycles and trikes at the Stanley Show. This marque was among several owned by the ever-confident Harry Lawson. The Autocar reported: “Recognising the uselessness of the motor bicycle for general use the company does not propose to continue their manufacture in large quantities.”

IN LONDON A DUNLOP Rubber engineer, Arthur Hertschmann, built an air-cooled four-stroke vertical twin and bolted it into a bicycle frame with separate inclined cylinders clamped to either side of the downtube. It featured chain drive and ram-air cooling with a cowling over the head.

IN THE USA Hiram Maxim (of machine gun fame) built a petrol trike while working for Colonel Albert Pope, the country’s leading cycle manufacturer. When he showed it to Pope the Colonel snorted: “You can’t get people to sit over an explosion.” Three years later he would be making motor cycles.

THE HOLLEY BROTHERS, Earl, 16, and George, 19, of Bradford, Pennsylvania, built a trike using a single-cylinder engine of their own design and manufacture. They called it the Runabout and proceeded to top 30mph.

THERE WAS SO much interest in the Werner Brothers’ petrol-powered bicycle that they bought some bicycles from the Hozier company of Glasgow, fitted engines and marketed them as Motocyclettes. Harry Lawson paid £4,000 for the UK manufacturing rights—a much better deal than he got from Pennington.

THE FIRST COUPE des Motocycles was a five-lap/100km race between Saint-Germain and Ecquevilly about 20 three-wheelers entered, along with an un-named “bicyclette” ridden by a M Simon; alas it failed to finish. Most of the trikes used De Dion engines—De Dion offered a trike to the winner. Other prizes included a bronze from a local property developer named Dufayel and 100 litres of Motonaphta (petrol). However a handful of riders turned up on Léon Bollée trikes which took four of the first five places. First home 2hr 46min 17sec was Léon Bollée himself who presumably took home a De Dion. Evidently the two ends of the road between Saint-Germain and Ecquevilly ended in hairpin bends The reporter of La France Automobile reported: “They (the Léon Bollées) arrived at full speed on the right-hand side of the road and abruptly locked their brakes at the same time as they gave their front wheels the sharpest possible angle to the left. In this movement, the rear wheel was brutally driven away by the acquired speed, it was driven onto the ground, and the car was straightened out by itself. This is the controlled skid that is well known to tricycle drivers!”

THE STADE-VÉLODROME in the Parc des Princes in Paris was christened by motor cycle races. Gaston Rivierre on a De Dion-Bouton won the first series and posted the best time of the day at 40.8km/h.

1898

“TWO OR THREE YEARS AGO,” according to the Chicago-based The Cycle Age And Trade Review, “the general appearance and use of the motorcycle the world over seemed an immediate certainty. Oddly enough, this anticipation has been abundantly realized in some countries, while in others it has been almost wholly disappointed. In France the motorcycle has ‘arrived’, and is seen everywhere; large establishments exclusively devoted to its manufacture are running day and night and are yet months behind their orders. The principal type of motorcycle adopted in France is that driven by the gasoline engine; there are several makers, but there is no material difference in the ‘petrole’ engines. Then in France, there are a number of builders of steam driven motorcycles, The Companie General, Decanville-Serpollet, Dion et Bouton, Le Blant, Societe des Chaudieres Scotte, and Weidknecht, who are doing heavy work, mainly in the omnibus and goods-carrying lines. There are no less than 47 different firms and companies and individuals manufacturing ‘petrole’ motorcycles in France, many of them having large plants, and all full of orders, most of them declining to fix day of delivery, and the customers paying each other premiums for early-filled orders. There are also nine concerns which supply electrically driven carriages, making a total of over sixty motorcycle builders in France, and the French nation seems to be falling over itself in its eagerness to buy the product of these makers. The Winton motor carriage company at Cleveland are offering motorcycles with gasoline motors. The Fierce-Crouch Engine Company, New Brighton, Pa, have placed their gas engines in two motorcycles and say that the lightness of their engines and several other advantageous features make them peculiarly suitable for motorcycle service. But neither in England or America is the gasoline motor driven motorcycle received with anything like universal approval. They are hot, they are not exactly quiet, they want a lot of cold water, although they are said to emit ‘very little’ in the way of disagreeable odours. There are only a very few gas engine driven motorcycles in the hands of purchasers in America, perhaps not more than ten or fifteen all told. So far, all of the gasoline or gas engine driven motorcycles are practically identical so far as the motive power is concerned. There are small detail differences in the engines, but nothing radical or generic to distinguish one from the other. They are all explosion engines, using a mixture of air and gas which is very much compressed and then fired in the engine cylinder or an extension of the engine cylinder, by an electric spark or by a red hot tube. All of these gas engines operate on what is known as the ‘Otto-Cycle’, that is to say that the cylinder and piston perform several entirely different acts, and these acts recur in a fixed sequence. Thus one stroke outward of the piston draws into the single-acting cylinder, a mixture of gas and air, the following inward stroke of the piston compresses this charge at the expense of power stored up in the fly-wheel, and at the end of this inward stroke the charge is fired and creates a pressure of about 170lbs to the square inch, which drives the piston outward in its effective or working stroke, at the end of which the cylinder is filled with burned vapour which is inert, and is pushed out of the cylinder at the next inward stroke of the piston, which completes the ‘cycle’ invented by Dr Otto, an eminent German improver of the gas engine, and bearing his name. There are thus three strokes of the gas engine which do not help turn the crank shaft, so that the engine is idle three-fourths off the time, and if only a single cylinder is used, the crank shaft obtains a turning impulse only during one-half of each alternate revolution. If two cylinders are used in one vehicle then the crankshaft has a turning impulse given it during one-half of every revolution it makes, and if four cylinders are employed then the crankshaft receives two turning impulses during each revolution, same as the ordinary single-cylinder steam engine. The cycle’ makes a single cylinder gas engine a very unsteady driver, and hence calls for a large and heavy flywheel. The gas engine was first applied to carriages in any notable way by Daimler, a German who ran a little pleasure railway from the little town where he lived to a little lake…Now that Dr. Otto’s patents have expired, the gas engine is free to the world, and there are no patents of controlling effect in the art…There are constant rumours of the formation of motorcycle companies, but the foregoing about covers the American motorcycle industry, so far as it has a tangible existence. The English are making an effort to place the steam-engine driven motorcycle in front, and this form of motor has undeniable advantages for general heavy work. It does not now seem likely that the petroleum or gasoline engine driven motorcycle is to have any great use in either England or America until the engine has been very materially improved. Americans want machines that are nice in every way; silent, clean, and without bad smells…For three-quarters of a century the best of mechanical talent has directed its efforts towards the improvement of the steam boiler without finding any radical or fundamental advantage…there seems to be no prospect of anything new in the steam way that will make the steam motorcycle desirable for anything except heavy freight work. With the gas engine we have unlimited power at our disposal. We can carry a large amount of gas-producing materials, and the air is everywhere with us. We can mix air with a little gas and squeeze this mixture pretty hard, and fire it off and so obtain all the power we want, and obtain it in a controllable form. Having the power, it seems beyond dispute that we shall sooner or later find out how to use it. We shall find some elements which we can place between this force generated by explosion and the wheels of our vehicles which will be wholly satisfactory. The power, the living force, is in our hands now. We shall learn how to use it.”

WERNER BROS SOLD more than 300 Motocyclettes, including a number in Britain via Harry Lawson’s Motor Manufacturing Co (MMC). Lawson also had the rights to De Dion’s tricycle, which Humber made for him.

CARRIAGE BUILDER Henry Timken developed a tapered roller bearing sturdy enough to be used in wheel hubs.

ELMER SPERRY OF Cleveland, USA built an electric car with disc brakes – the brake pads were applied by electromagnets.

IN GERMANY’S FIRST race, over the 36 miles from Berlin to Potsdam, a Beeston-Humber trike took the flag ahead of a Daimler car and a Clement trike. Harry Lawson launched a Beeston motor cycle using a strengthened bicycle frams. It was powered by a 346cc De Dion engine mounted low, just behind the pedalling gear. Triumph considered making it under licence, but no agreement was reached. Siegfried Bettman also negotiated to make Humber motor cycles but failed to come to an agreement.

JULES TRUFFAULT made sprung forks for his bicycle; they were quickly adapted to suit motorcycles.

JAMES LANSDOWNE Norton began making bicycle parts, primarily chains.

THE SCOTTISH REFEREE REPORTED: “A very interesting interview with Mr SF Edge, the manager of the Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co, appears on the subject of motor cycles in this week’s Cycle. Mr Edge was first introduced to the motor cycle somewhere in the spring of last year, since which time in company with Mrs Edge he has travelled over 4,000 miles in his motette. Regarding break-downs to motorcycles, Mr Edge affirms that this has been much exaggerated. Asked whether he thought the motor-cycle would supersede the present type of cycle, Mr Edge gave it as his opinion that it will not, on account of the expense, but added that motor-cycling will doubtless become a popular sport just as yachting.”

PEUGEOT EXHIBITED a prototype De Dion-engined Peugeot bicycle at the Paris Salon in 1898, but the first motorised cycles to leave the factory were trikes with De Dion-Bouton engines.

GLOBAL PRODUCTION of aluminium had risen from 15 tonnes in 1885 to several thousand tonnes.

ROBERT AYTON OF COVENTRY lodged a patent covering “Improvements in or relating to radiating devices for heating or cooling purposes…According to this invention I provide the tube, cylinder, or other body from which heat is to be radiated, with a partial or total covering constructed of a metal having a higher conductivity than the metal of which the tube or cylinder itself is composed. Thus in applying the invention to the cylinder of an internal combustion engine, the cylinder may be provided with a conductive covering or with wings or gills constructed of aluminium, silver, or some alloy of these or other metals, whose heat conductivity is considerably greater than that of the iron or steel of which the cylinder is composed…” It was an idea ahead of its time so Ayton did not profit from his patent but he did build and race his own bike in the first (1907) TT. He used a Riley Engine and finished 7th.

THE SCHRADER valve stem was patented to facilitate inner tube inflation; we’re still using it today.

ANDREE BOUDEVILLE developed a high-tension magneto in Paris, but it lacked a condenser.

DUTCH (EYESINK), Belgian (Sarolea) and Italian (Figini) motor cycles went into production.

HENRI FOURNIER TOOK the first bicycle pacing machines to the United States. A young French Canadian named Jake De Rosier became infatuated with the motorised machines and, after much persuasion, convinced Fournier to let him ride one. Fournier was impressed enough to hire De Rosier to ride for him in the Paris races. We’ll meet Jake again.

WILLIAM R. BULLIS of Chatham, Massachusetts patented a twin-cylinder two-stroke engine equipped with poppet valves; the inlet valves were automatic. The fuel pipes were to be coiled round the cylinders to cool the engine while utilising its heat to vaporise fuel. The ignition was to be actuated by a fitting on the tops of the pistons. The Horseless Age reported that Bullis’s engine had been fitted to a “railroad velocipede with most satisfactory results” as it produced “unusual power”. Bullis’s patent drawing bore an uncanny similarity to the twin made by that arch fraudster Joel Pennington in 1896. (Scroll back up, unless you’ve just been there; or read more about the scoundrel in the gallimaufry.)

“A MOTOR-CYCLE’S MISBEHAVIOUR. Before the Chester magistrates yesterday, Mr Henry Burton Webb, manager of the Rock Ferry Cycle Company, was charged with a breach of the Locomotive and Highways Act. It appeared that Mr Webb arrived in the city from Shrewsbury with his motorcycle. At Chester the machine failed for want of oil. He bought a quantity of benzine, and was proceeding to examine the cycle with a light when the benzine exploded. The flames went as high as the houses, and a boy named Whitley was severely burnt. The inspector of petroleum stated that benzine flashed of its own accord at a temperature of 51°. The defence was that the people flocked round to see the machine, and that the affair was purely an accident. The Bench said they considered the explosion was quite unintentional. At the same time there had not been reasonable care taken, and they inflicted a fine of 20s and costs.”—Westminster Gazette

1899

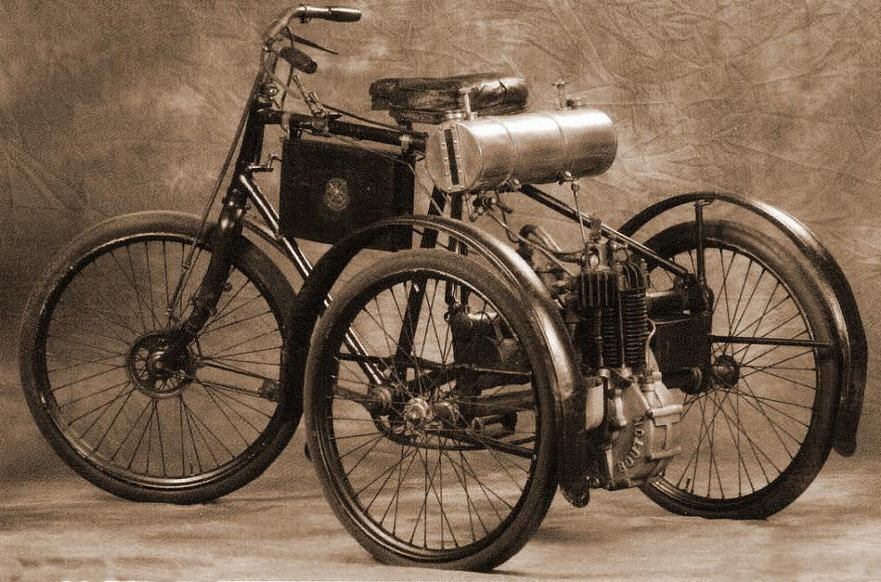

PRINETTI& STUCCI of Milan, who had been making sewing machines since 1882 and bicycles since 1892, began making Tipo 1 trikes (and quads) using not one but two De Dion engines. They were designed by Ettore Bugati who drove a Tipo 1 to victory in a number of road races. Carlo Maserati built a bike on which he also won several races (yes, THAT Bugatti and THAT Maserati).

THE COLLIER Brothers put Woolwich on the map with the first Matchless.

WITH DE DION concentrating on trikes and quads the relatively crude Werner had the market to itself. Harry Lawson’s Motor Traction Company bought the UK rights to the Motocyclette for £4,000; the Werners replaced its hot-tube ignition with a trembler coil. MTC also bought the rights to the four-cylinder Holden. Raleigh fitted 1½hp De Dion engines into its trikes. De Dion-style engines were built under licence by Fafnir in Germany, Laurin and Klement in what is now the Czech Republic and MMC in England. Other firms simply built their own versions; they included Aster, Buchet and Clement in France, Sarolea in Belgium and ZL in Switzerland. Also in Switzerland Henri and Armand Dufaux made an engine to power bicycles. It came in its own subframe which was said to look like an engine in a bag so they called it the Motosacoche, which translates as “engine in a bag”.

FOR ANYONE PLANNING an Easter run The Autocar listed petrol suppliers—there were four in London and 29 elsewhere in England, including a chemist and a grocer.

IN THE US THE Marsh Brothers, WT and AR, built the 1hp single-cylinder Marsh Motor Bicycle.

IN FRANCE Paul Bruneau launched a business making motorised bicycles and tricycles.

HUMBER CONSTRUCTED a tandem, driven by a battery-powered electric motor. Although its life was short—petrol-engined pacers were faster—it proved to be useful on racing tracks where it was used for cycle pacing. A ladies’ bicycle, modified to carry an engine behind the seat tube, was also produced, along with a forecar known as the Olympia Tandem. This was based on the Pennington design, with the engine hung behind the rear wheel. None of these models were produced beyond 1899.

FOLLOWING A FACT finding tour of France, Germany and England, or to be more precise, Coventry, German emigree Alexander Leitner returned home to Riga, Latvia to set up as a bicycle manufacturer. He prospered. Then, having tried and being unimpressed by a Hildebrand & Wolfmuller, Leitner saw some De Dion trikes in St Petersburg and produced half a dozen, using a reinforced version of his existing pedal tricycle.

JOHN HARRIS OF CLEVELAND, OHIO was using an oxy-fuel process in an attempt to make synthetic rubies and sapphires when he accidentally cut through a steel plate. He developed the process and established the Harris Calorific Company to manufacture and sell oxy-acetylene welding and cutting equipment.

JOHN PERRY, DSC, FRS, PROFESSOR OF MECHANICS and Mathematics in the Royal College of Science, Vice-President of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, Vice-President of the Physical Society, wrote a prophetic essay on the evolution of engines and energy sources: “Watt was jubilant if his cylinder was not more than an inch untrue in its bore…the limits of error now allowed by Messrs Willans and Robinson are 0.05mm, and there is less error allowed in other parts of an engine (the metric system of measurement is in use in these excellent shops; its introduction has given no trouble whatsoever). in 1629, the Italian architect Giovanni Branca conceived Branca engine that operated on the same principle as today’s impulse turbines, but it remained at the conceptual stage and never saw practical use. Why! the very engine of Branca, almost without improvement, has lately been brought into use, and already competes in economy with the very best steam engines of equal power. There is a great deal of virtue in a revolving wheel. It may go at great speed, and yet not shake the framework which supports it, even when this framework is light. The very earliest engine, that of Hero, was really a revolving wheel, a reaction turbine, and as I write this (April, 1897) I have received a letter from a friend in Newcastle to say he had just been out on the new Parsons’ turbine steam boat, and that it proves to be the very fastest boat that has ever gone through the water, although only 100ft long. And furthermore, at much smaller speeds, the very best other boats vibrate so much that a man in the stern can hardly keep himself upright, even when holding on hard, whereas at its highest speed the Turbinia has no vibration. When Aladdin first discovered the power at his command it is remarkable how conservative he was in his notions. He made the genie bring him silver dishes, because he started in the silver dish line, and there is one of the most interesting of lessons in the fact that although each of his silver dishes was worth sixty pieces of gold, he sold each of them for one piece of gold over and over again. Aladdin’s imagination had to be stirred by a violent emotion before he could make the genius work in other ways for him. Even at his best I believe that Aladdin never took full advantage of the power of the wonderful lamp. His finest palace was probably just an ordinary house, made very large and stuck over with precious stones, as vulgar as Milan Cathedral. The engineer, far more than Aladdin, needs to have his imagination developed, because Aladdin’s power was unlimited, whereas, great as the stores of Nature are, they are not all for the engineer to develop. It is possible that future scientific men may discover some way of developing them, but so far as we can see there is no great store of energy available for man which is in any way comparable with coal. For the past 20 years I have lifted up my voice occasionally in the hearing of a not unbelieving but a half-hearted generation, to warn men of the time to come, when their great stores of energy will be exhausted. The chancery law of England is destroying invention in all but small details; but if I am right in my beliefs, it would be worth while for our government to hand over a few millions of money to its best scientific men, telling them to squander it in all sorts of experiments, in an intense search for some method by which instead of only from one-twelfth to one-hundredth of the energy of coal being utilised, nine-tenths of it might be utilised. If I am right, almost all the social and political questions which excite us now will be of small importance on the future of the human race, for the wild competition of nations and people for luxuries must gradually during the next 400 years become a struggle for mere existence. Quite common men live now in houses furnished with luxuries of which no potentate of the Middle Ages could dream. I think it to be evident that very much the greater part of all that goes to make up our civilisation is directly or indirectly to be traced to our utilisation of coal, and it is just as evident that when our stores of coal get exhausted the greater part of all this wealth and evidence of civilisation must disappear. The world will not be left in its old state. The old state was like that of an earnest poor young man with great hopes, the new state will be that of the spendthrift, whose fortune has gone but whose expensive habits remain. Then will come the time of great struggle for Niagara by all the civilised nations of the earth; the water power of the West of Ireland will form a new centre of civilisation, as will the hills of Switzerland and all places of high tide round the coasts of the world. Then will be the time when men will try to utilise the stores of energy which now seem to be insignificant or hopelessly out of our reach: the direct radiation from the sun or the internal heat of the earth. I am sure that the mind of no engineer ought ever to be quite free from this incubus that we are wasting our coal with enormous rapidity: that a heat engine is essentially uneconomical. But this book is altogether about heat engines, and when in future I shall speak of the economy of a steam engine, I shall compare it not with that of the perfect engine about which we know so much, but of which not one cheap specimen has yet been made, and not even with the most perfect heat engine imaginable but with the perfect steam engine. In Great Britain an annoying defect may remain unreformed for a century, but let it be called a nuisance by a chancery court and reform is very rapid. Large steam engines are now working in towns: not merely in the slums, but in the districts inhabited by rich people. We are first told that really we must produce no smoke, and instantly we use mechanical stokers or better grates and flues, and we refrain from forcing the fires, and get rid of smoke, although for 100 years every engineer has declared the thing impossible. There is a vast difference between being asked to try to get rid of a nuisance and being told by the policeman that we must stop working if we create a nuisance. We find it necessary to use non-condensing engines in towns because condensation water is expensive; and of course our blast pipe becomes an organ-pipe nuisance; we find that all window frames within half a mile are really microphones. We have remedied this defect of our engines because the only alternative was to stop working. There is a defect that is put up with in locomotives and in ships which is ever so much worse in a large town, and it has been declared to be a nuisance. Consequently every young station engineer has already acquired an astonishing amount of cunning in diagnosing it and mitigating its effects. It is the vibration produced by reciprocating engines. Of course the only real remedy is the use of a steam or gas turbine, sure to be applied in the long run; but capital has given momentum in the direction of reciprocating engine manufacture, and a complete change towards turbine manufacture must be slow.”

THE CRITÉRIUM DES Motocyclettes is said to be the first race to have been run exclusively for motor cycles. It ran from Etampes to Chartres and back over a distance of 100km; Eugène Labitte won on a Pernoo motorcyclette, powered by the 1¼hp Labitte engine he produced.

“PARIS, BEING AT PRESENT without any cycle races, seems to be taking kindly to motorcycle contests. One of these was held on Sunday last at the Parc des Princes cycle track, the competitors being Corré and Osmont, who both rode petroleum tricycles. The match was of six hours duration, and Osmont won, covering 236 kilometres, leaving Corré (the old-time cyclist) a long way behind.”—Cycling

THE FIRST MEETING of the Tour de France Automobile was held, with 19 cars and 25 motorcycles starting a course of seven stages over 2,216km.