BROOKLANDS STAGED A 200-MILER; Bert Le Vack won the 350 and 1000c classes for New Imperial and Brough Superior. The track also hosted two record attempts. Freddie Dixon did 106.8mph on a 989cc Harley, then CF Temple brought the record back to Europe, squeezing 108.5mph from his 996cc British Anzani. George Brough wasn’t going to take that lying down. He hired Le Vack; they went to Arpajon and raised the bar to 118.98mph.

ALFRED SCOTT DIED OF PNEUMONIA, aged just 48. As well as his revolutionary two-stroke twin-cylinder water-cooled motorcycle, he is generally credited with the invention of the kickstart. His patents covered everything from a triangulated frame to rotary induction valves and unit construction.

SADDLE TANKS WERE becoming more common; marques to adopt them included Coventry-Eagle, Brough Superior, Cedos and Mars.

AMONG THE 1923 SEASON’S must-have goodies were straight-through copper exhaust pipes. One example, made just for Duggies, was marketed as the Zoom-Zoom, promising “no back pressure, pleasing note, improved appearance” (with regular polishing, no doubt).

TRIUMPH’S 350CC THREE-SPEED Model LS (for Light Solo) was unique in the company’s line-up in that it came with unit-construction and an engine-driven oil pump. The company had just started to produce cars and this seems to have influenced the design. The driveline was certainly state of the art; however roadtests in the Blue ‘Un and Green ‘Un agreed that the footrests were too far forward; the wide handlebars hit the rider’s knees when attempting to turn; the front brake would not hold the bike on a rising slope and a foot had to be lifted from the footrest to operate the rear brake. Overall it was not a pleasant machine to ride and was soon withdrawn.

WHAT IS BELIEVED TO BE the first motorcycle football match was played on Good Friday at the well established Richmond Meet, hosted by the Middlesbrough Club. Legend has it that the idea came from a committee member called Freddie Dixon. Yes, that Freddie Dixon. As the sport caught on the club drew up rules that were adopted throughout the empire. [Historical footnote: the first game was enlivened by the presence of one George Butt Craig who turned up in “riding breeches, stockings, a jersey with a black and red vee-shaped stripe on the upper portion, and a bowler hat from which the crown had been removed and on which the rim was worn upside down”.]

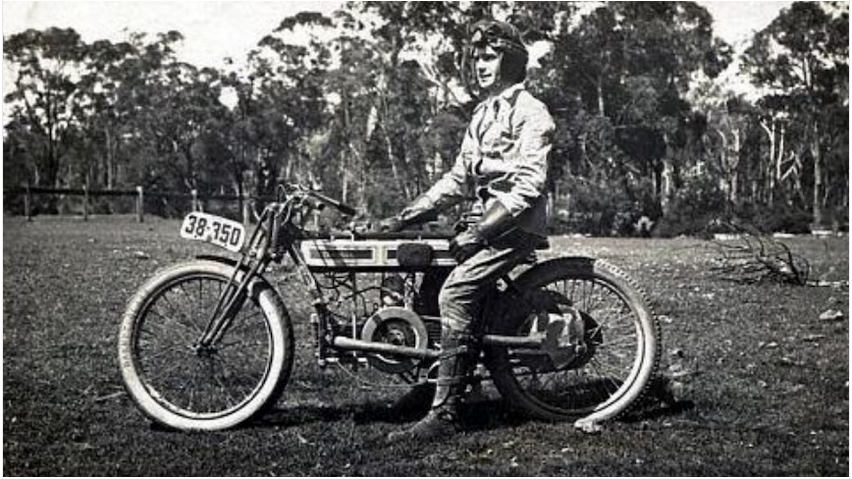

EXACTLY 100 YEARS AGO as I write this (on 15 December 2023) a speedway race was staged at Maitland Showground in New South Wales’ Hunter Valley. Speedway fans should raise a glass Johnnie Hoskins, a Kiwi who was in West Maitland because, according to Jennifer Buffier of the Maitland and District Historical Society: “He was broke in Sydney, he had a few bob in his pocket, he plunked it on the counter at Central Station and said something like ‘give me a ticket to wherever this will take me’.” Hoskins got a job as secretary of the West Maitland Agriculture Society and was expected to increase its membership. Ms Buffier reports: “He tried many events during his first year and nothing was really working. He proposed motorcycle racing at the showground, but the idea was initially rebuffed by the committee. As a last resort he got some of the boys who rode motorbikes together on a quiet Sunday morning and decided to race on the [showground’s] sacred trotting track. Because of the large crowd that was drawn in, committee members agreed to host a proper race event at the showground.The event saw a huge crowd and, due to popular demand, weekly race meets were held at the showground thereafter. What we had was the consistency of weekly races and we paid regular prize money so the guys could actually turn professional.” The Maitland Daily Mercury reported: “Motor cycle races will be a novel feature of the sports carnival to be held on December 15 on the Show Ground. The track is in splendid order, and it is expected that over 40 entries will be received for the different motor cycling events. This will be the first time that motor cycling races have been held on the Show Ground, and the events should therefore prove of great interest.” Three years later Hoskins was promoting speedway at the Sydney Showground; in 1928 he headed for Blighty…

HERE’S A GOOD YARN from The Perth Daily News, reproduced from Vintage Chatter, the excellent magazine of the Vintage MCC of Western Australia: “The two overland cyclists, Messrs CV Watson and A Grady, members of the Coastal Motor Cycle Club, have returned home after securing the honour of having completed the first successful attempt that has ‘ been made by motor cyclists to accomplish the long journey from Perth to Adelaide. Messrs Watson and Grady, who are young men, traversed the coastal route via Eucla, using an 8hp BSA motorcycle…they covered 1,952 miles in 154.25 hours, which they regarded as fair average travelling. Their longest day’s run was 208 miles, while on another day they did 196 miles. Still another good day’s run was 194 miles. The engine withstood the severe test over rough roads and beaten tracks remarkably well. ‘Not once did we have to decarbonise the engine, or was a spanner required at any time on any mechanical part,’ remarked Mr Watson. Referring to the trip, Mr Watson said that all went well until they had passed through Norseman. They then got on to the wrong track, and had to return on low gear. That delayed them three days. In the Nanwarra drift sands their progress was so slow that only 15 miles was registered in 12 hours. In one part of the journey they were for two days without water, when they were fortunate enough to strike a workman’s camp. It was not until they had crossed the South Australian border that wet weather was experienced. The machine and side car were at times coated with mud, and as the vehicle had no mudguards both he and his comrade were most uncomfortable. The road and tracks in places, were in a bad state. Before reaching Port Augusta, they encountered a claypan, which held them up for four hours. Messrs. Watson and Grady spoke highly of the hospitality accorded to them by people along the route. ‘Now that we know the road, we intend to make another attempt,’ said Mr Watson. The overlanders returned to Western Australia by train.”

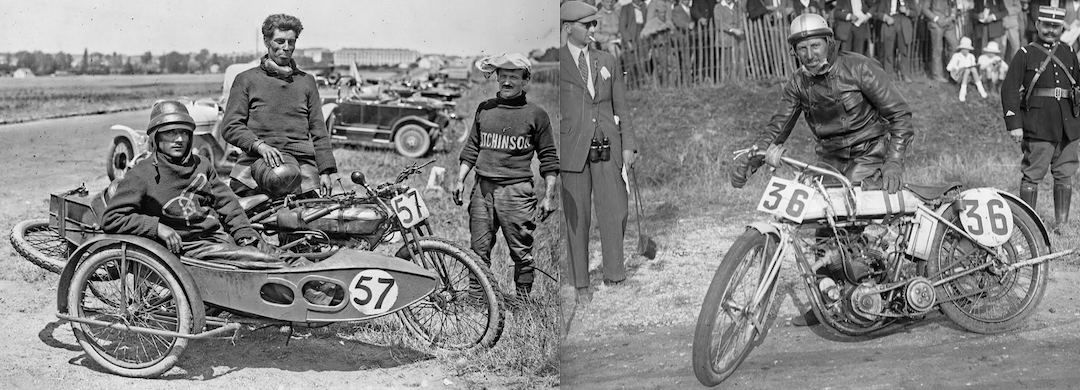

THE BLUE ‘UN AND GREEN ‘UN published comprehensive reports on the TT but there was an excellent alternative. What follows is the 1923 TT as recounted by Geoff Davison in his legendary annual, TT Special. Mr Davison, you have the floor: “In response to popular demand, as they say, the Auto-Cycle Union staged a sidecar race for the first time in 1923. The year was also an outstanding one for the TT, in that the entries constituted an absolute record. There were 177 in all—17 better than the previous record of 160 in 1914. Although the sidecar race attracted only 14 competitors, it was considered by many to be the most interesting of all. Eight different makes were represented and the field was divided evenly between singles and twins. The biggest support was by Douglas, with three machines, whilst Nortons, Scotts and Sunbeams had two apiece. The cubic capacity limit was raised from the normal 500 of the Senior to 600cc and only three laps had to be covered. One of the most interesting machines in the race was the banking [Douglas]

sidecar outfit driven by Freddy Dixon. This was an ingenious device which enabled the whole machine to be leaned over to the right or left as was required. ‘Its effect was naturally more marked on left-hand corners,’ Freddy told me, ‘but, of course, it was very useful on right-hand bends as well. It was operated by my passenger, but, except on a quick S-bend such as Braddan Bridge, I didn’t expect him to judge when to put it into action-whenever possible I gave him a signal for each bend and he then got busy.’ I asked Freddy how much he thought it increased his speed on the corners. ‘That’s almost impossible to say,’ he told me. ‘It all depends on the type of corner, but it was very much faster than a rigid-frame job. On a high-speed left-hand bend it might easily have raised the safe speed 10 or 15mph, and on very slow bends, such as Governor’s Bridge and Ramsey Hairpin, my banking sidecar outfit could probably get round considerably faster than any solo machine.’ ‘How did the race itself go, Freddy?’ I asked him. ‘Well, everybody thought in advance that it lay between Harry Langman [Scott] and myself. Harry had been putting up some very good laps in practice and I reckoned he would want some beating. We started off at half-minute intervals in the afternoon, as soon as the

lightweights had finished. I was No 55 and Harry No 59, so I was two minutes ahead of him on the roads. I didn’t know my position at the end of the first lap, of course, and I chased along nicely in the second lap, thinking I was doing pretty well. Then, going up the Mountain, I was singing cheerfully to myself “We won’t be Home till Morning,” when I suddenly found Harry on my tail. That meant that he had picked up two minutes on me in just over a lap and a half. I went off like a scalded cat and got away from him all right, but I had to stop for petrol at the end of the second lap and whilst I was at the pits, Harry, who didn’t need to stop, came tearing past. Off I went again, down Bray Hill, round Quarter Bridge and flat out for Braddan, when I suddenly sensed some sort of commotion at Braddan and, as I rounded the left-hand bend, saw that there had been a crash. My passenger did some hectic work with the banking sidecar and we managed to get through without hitting anything. As we passed I realised that it was Harry who had piled up. He was not much hurt, but was obviously out of the race. As it was, his crash gave me the race, for his Scott had the speed to hang on to me and, if he had let me past on the third lap and stayed on my tail, he would, of course, have won by an easy margin. When I saw that Harry was out of it, I took things a bit more easily, which was just as well, for at Hilberry on the last lap one of the frame tubes broke and the outfit folded over so much that the handlebar jammed on the Sidecar body. I had to trickle on very slowly after that and almost lifted the machine round Governor’s Bridge. However, it just got me to the end and I finished just under a couple of minutes ahead of Graham Walker on the Norton.’ So that was the first Sidecar TT. Freddy Dixon’s speed was 53.15mph and Harry Langman made the record lap at 54.69. George Tucker, on another Norton, was

third, a minute behind Graham Walker. It was then 23 before the next man-DH Davidson (Douglas)—arrived. A somewhat disappointing race, with only 14 entries and six finishers, but one which had provided the public with an extraordinary number of thrills. Now back to the 1923 solo races. The increasing speed and reliability of the Junior and Lightweight machines made it clear that they could stand a longer race than in the past. The distance of these two events was therefore increased from five laps to six, the same as the Senior. Entries for the Junior had closed with the total of 72, which stood as a record for the event until 1948, when there was an entry of 100, as there was again in 1949. Twenty-one makes were represented, Douglas heading the list with 11, of which no fewer than 10 were works entries. AJS had nine and Sunbeams-newcomers to the Junior race-seven. The Matchless firm had now come back to the racing game, with an entry of four, whilst New Imperials, hopeful after Le Vack’s fine ride the previous year, had five. Amongst the riders there had been various changes of camp, perhaps the most notable of which was that Jim Simpson had turned from Scott to AJS and Alec Bennett from Sunbeam to Douglas. The race itself provided a number of surprises. Jim Simpson had shown up well in practice, but his only race experience amounted to less than one lap in the Senior of the year before. Those who had studied form, however, realised that he was a man to he watched and wagged knowing heads when he covered his first lap in 38 minutes dead—2min 7sec better than the existing Junior record and only 14sec outside Alec Bennett’s Senior recent of the year before. Charlie Hough, on another AJS, was second and Bert le Vack had to be content with third place. Jim retained his lead in the next lap, but Hough dropped out, letting Le Vack into second place, 1min 33sec behind the leader. Stanley Woods (Cotton) was third, Tommy de la Hay

(Sunbeam) fourth and Vic Anstice (Douglas) fifth—five different makes in the first live places! Then Jim broke down and Le Vack and Woods moved up. Positions in the fourth lap were the same, with Woods closing in and George Dance (Sunbeam) in third place, less than half-a-minute behind him. Le Vack then retired and Woods had a slow fifth lap, giving George a lead of over 2½ minutes. We said that at last George Dance was to break his phenomenal run of bad luck. I was watching the race personally from Sulby Bridge and George came round on his last up, with, I reckoned, a good three minutes lead. But once again bad luck overtook him, for he broke down on the Mountain when victory was almost within sight. Woods went on to win the first of his ten TT races, with HF Harris (AJS) second and Alfie Alexander (Douglas) third. Stanley’s speed was 55.73mph and Jim Simpson’s first lap in 38 minutes constituted a record at 59.58sec. The Lightweight race, held on the following day, produced a record entry of 40, which has only once been beaten since, when in 1931 there were 44. Once again it was thought to be a battle between two-strokes and four-strokes, but those of us in the Levis camp-the only two-strokes represented-knew that we had little real chance. The best of the four-strokes had always been a shade faster than our machines and they were now getting much more reliable. We knew that it would be really a battle between Blackburne and JAP engines, and so, indeed, it turned out, with Blackburnes first and third and a JAP second. The first two-stroke home was no higher than seventh. Wal Handley

led off the race in characteristic style with a record lap of 53.95mph. He was followed by Jock Porter, the Scot rider-manufacturer of the New Gerrard, nearly two minutes behind. Wal led again on the second lap by 3½ minutes, but Jock was less than half-a-minute behind him when the third lap positions were shown. Wal slowed down in the next lap, letting Jock Porter into the lead, which be retained to win at 51.93mph by nearly five minutes from Bert Le Vack on the New Imperial. The 1923 Senior shook us! So far as I remember, it was the first wet TT since the Junior of 1912, and none of us, I think, who were riding in 1923 had competed in that event eleven years before. It was drizzling at the start and conditions on the Mountain were obviously dreadful, for there was a low bank of cloud over Creg-ny-Baa. This meant that we should probably be riding through mist for about ten miles of the Mountain stretch. In contrast to the huge entries for the Junior, there were only 51 in the big race, the principal makes being AJS (still 350s), Douglas, Indian, Norton, Scott, Sunbeam and Triumph. Douglases were back in earnest, with nine works entries, including amongst their riders Alec Bennett, Cyril Pullin and Tom Sheard-all past TT winners-and Jim Whalley, who had so nearly won the Junior in 1921. They had proved very fast in practice, but had had a fair amount of mechanical trouble and it was popularly said that they wouldn’t last the course. The other camps were not unduly alarmed, therefore, when the fat-twins took first four positions at the end of the first lap. Jim Whalley led with a lap at 59.74mph, actually the fastest of the day, with Alec Bennett second, Alfie Alexander third and Tom Sheard fourth, less than a minute separating the four. Alec slowed down next lap, but Jim maintained his lead for the second and third laps, after which Tom Sheard, the Manxman, who knew every inch of the course and was alleged to take the almost invisible Mountain bends by memory rather than by sight, came into the lead. By the last lap all the Douglases except Tom’s had disappeared from the first five. The Manxman slowed down slightly to be on the safe side, but won by nearly two minutes after the most miserable Senior that was ever run. The only bright spot in it for me personally was when I broke down at Ramsey and came home by the Mountain Railway with Howard Davies, the pair of us eventually acquiring an open horse-drawn carriage and driving it to the start at the end of the race in crash hats and soaking leathers. That would have made a picture

which the Press photographers missed! In view of the fearful weather, Tom Sheard’s speed of 55.55mph was most creditable, but it was nearly 3mph slower than the 1922 Senior…No-one had yet lapped the TT course at the full 60mph.” Spare a thought for Jim Whalley who came so close with a Senior lap at at 59.74mph on his Douglas before retiring. Graham Walker had a better year: runner-up in the Senior and 4th in the Sidecar (The Motor Cycle described the sidecar race as “the most spectacular and genuinely thrilling struggle to be witnessed in the Isle of Man”). The Douglas team could also rejoice, with wins in the Senior and Sidecar and a 3rd in the Junior; and Manxmen must have ben proud that, having won the Junior the previous year, local lad Tom Sheard won the Senior. Jock Porter won the Lightweight on the New Gerrard he’d launched the previous year. Stanley Woods’ Junior victory was the first of 10 TT wins; Jimmy Guthrie failed to finish his Junior outing but would go on to win six TTs. And Geoff Davison, who wrote the report you’ve just read, rode his Levis to a creditable 10th place in the Lightweight.

Lightweight: 1, Jock Porter (New Gerrard) 51.93mph; 2, Hubert Le Vack (New Imperial); 3, D Hall (Rex-Acme); 4, R Gray (Rex-Acme); 5, N Black (Cedos); 6, L Horton (New Imperial). Junior: 1, Stanley Woods (Cotton) 55.74mph; 2, HF Harris (AJS); 3, AH Alexander (Douglas); 4, JA Watson-Bourne (Matador); 5, Vic Anstice (Douglas); 6, Frank Lomgman (AJS). Senior: 1, Tom Sheard (Douglas) 55.55mph; 2, GM Black (Norton); 3, Freddie Dixon (Indian); 4, Graham Walker (Norton); 5, Tom Simister (Norton); 6, JLE Emerson (Douglas). Sidecar: 1, Freddie Dixon & TW Denny (Douglas) 53.15mph; 2, Graham Walker & Tony Mahon Norton); 3, George Tucker & WW Moore (Norton); 4, Douglas Davidson (Douglas); 5, Harry Reed & Joe Hooson (348cc Dot-Bradshaw); 6, Freddie Hatton (Douglas).

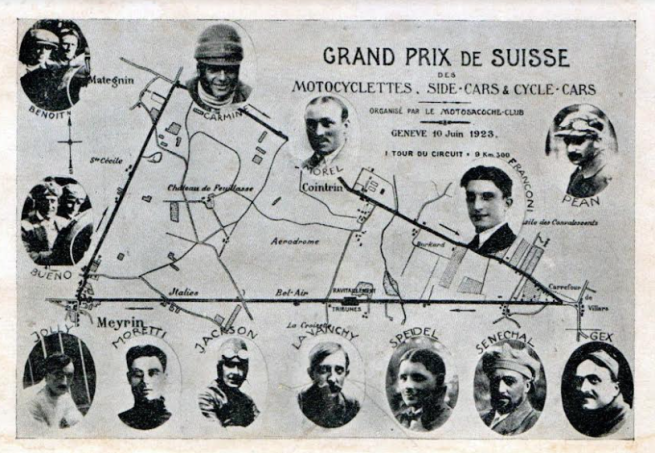

FOLLOWING THE TT THE BRITS crossed the Channel for the various Grands Prix. In the 500cc class of the French a Douglas was followed home by a pair of Nortons. AJS took 350cc honours; the top two 250s were Levis and Cotton. But the Brits didn’t have it all their own way. At the Belgian GP Indian took 500cc honours ahead of two Belgian-made Saroleas (Sarolea dated back as far as 1898, but during the early 1920s its 350 and 500cc singles had a distinctly British look to them). FN, also on its home ground, took 350cc honours but Wal Hanley’s Rex-Acme was the fastest 250 on the day. The Italian Grand Prix gave AJS another 350cc win but a 4-valve sohc version of the Peugeot vertical twin led the 500s by better than 12 minutes. The best placed Italian contender was a Guzzi, which came 4th. AJS collected another 350 trophy; the feared Garelli team was relegated to 4th, 5th and 6th spots.

The Helios was built in BMW’s factory using the 493cc flat-twin BMW engine but it wasn’t an inspiring machine. So, having made a success of its proprietary engine, BMW decided to produce a complete motor cycle. Max Friz, who had designed the engine, came up with the R32, featuring a tidy triangulated frame with leaf-sprung forks; the unit-construction 4½hp side-valve engine was mounted transversely. It was launched at the Paris Salon; this wouldn’t be the last time the Jerries took Paris by storm.

The Helios was built in BMW’s factory using the 493cc flat-twin BMW engine but it wasn’t an inspiring machine. So, having made a success of its proprietary engine, BMW decided to produce a complete motor cycle. Max Friz, who had designed the engine, came up with the R32, featuring a tidy triangulated frame with leaf-sprung forks; the unit-construction 4½hp side-valve engine was mounted transversely. It was launched at the Paris Salon; this wouldn’t be the last time the Jerries took Paris by storm.

FOLLOWING A GOOD SHOWING IN the 1922 ISDT in Switzerland, where two of their riders won gold medals, Sweden was granted the right to host the 1923 trial. The 1,863km route started and finished in Stockholm with a couple of days in Norway. A Swedish enthusiast reported: “I was surprised to see all the foreigners cope so well with the harsh Swedish conditions. We knew that ‘our own’ would be tested to the limit here, but we were all surprised that the international riders did so well in the inferno of mud. Going uphill during these demanding conditions was hard. The roads were so miserable that you thought you were standing in the middle of a recently ploughed field. Passing through with good speed required determination and stamina. And everyone seemed to know exactly where to change sides, taking another furrow to make the most of the race.

So, the first day ended in the region of Dalarna at Rättvik after 320km of riding. The second day was slightly longer being 378km in length, taking the fast crowd to Karlstad. Then it was time to go to Norway. On the third day, the riders went 270km to Kristiania (Oslo) before getting some rest. Outside of the Norwegian capital there was a hill-climb section of 2,250 meters. Being very steep, it was a decisive moment for many a rider trying to go fast uphill. After half the race, the Husqvarna team with riders Gustaf Göthe, Bernhard Malmberg and Gunnar Lundgren were well ahead—so far without penalties. On the fourth day, it was back to Sweden again, going all the way to Gothenburg—a distance of 388km. The fifth day was only 335km long, but at this stage, everyone was getting tired and you could see the strain in the faces of every participant. During the final stage back to Stockholm, 172km, there was a kilometre-long speed-stage ahead of the capital. It proved to be quite decisive and only the fastest managed to keep up their pace here. All in all, 67 riders were seen arriving at the finish line in Stockholm. Thirteen of them were awarded a gold medal while the Husqvarna team ended up winning the all-important Trophy class. There were of course happiness and congratulations in the famous red brick-wall Stadium, before everyone hurried to town for drinks, meal and final celebrations.”

ISDT Results: The Swedish team won the trophy; the Brits were runners up. Harley-Davidson won the manufacturer’s prize, with Husqvarna 2nd and FN 3rd. The club prize went to SMC Dalaavdening. Class winners were: Class A (250cc), Bert Kershaw (new Imperial), England; Class B (350cc), BL Bird (BSA), England; Class C (500cc), CL Vaumund (Triumph), Norway; Class D (750cc), Oluff Graff (Husqvarna), Sweden; Class E (1,000cc), JW Petterson (Excelsior), Sweden; Class E1 (unlimited), G Tidstrand (Ace), Sweden; Class F (600cc sidecar), P Pehrson (Dunelt), England; Class G, (1,000cc sidecar), Ed Gex (Motosacoche), Switzerland; class G1 (unlimited sidecar), E Friberg (Indian Big Chief), Sweden.

A RECORD BREAKING 130 ENTHUSIASTS started the Edinburgh &DMCC’s Scottish Six Days Trial; 89 of them completed the 1,010-mile route which included three new test hills. A dozen heroes earned gold medals, riding two Ajays, a Beeza, a Coventry-Eagle, a Douglas, an FN, an Indian, three Raleighs, a Triumph and a Velo. A trio of AJS 350s won the manufacturer’s team prize.

MIKUNI SHOTEN WAS SET UP to import vehicles into Japan, and to make components. Its carburettors would play a significant role in the development of the Japanese industry (in 1932 Mikuni bought manufacturing rights for Amal carbs). Nippon Jidoshe some Harley Davidsons; the company was run by Cambridge graduate Kishichiro Okuro who had taken second place in the first Brooklands car race in 1907.

MUSASHINO KOGYO MANUFACTURED a single-cylinder two-stroke powered machine for which it made an incredible claim; every part was made in Japan. If it were true it would have been an astonishing first; in fact magnetos, carburettors and gearboxes were imported.

WHITE LINES WERE PAINTED on the roads of Sutton Coldfield, Barnstaple and Kirton, Lincs.

“THIS PAGE,” IXION CONFIDED, “has never been closer to appearing with a heavy black border than in the current issue. I don’t share the common enthusiasm for helmets as headgear, but when the wind is east and the thermometer down towards zero, my somewhat elongated ears feel that they require what the airmen call ‘fairing’. So last week I donned a helmet, not because it was a helmet, but because my cap has no sausages The road ran between high walls, and twisted snakily towards the setting sun. All seemed clear, and I rounded a mildish bend at speed to get the full blaze of a Westering horizontal sun right in my eyes. Not a thing could I see for several seconds, and when visibility returned I was about half a millimetre off the tail of a nasty, solid looking coal cart, screened in the shadow of the wall. The Norton did a greased lightning right and left skid to round the cart without fouling the opposite wall; and when I got home, I gave the helmet to the children to play air raids with. There should be a market for a helmet with a light stiff peak (say, aluminium, covered in leather), for a low sun is awkward for a westbound rider in unpeaked headgear at any season of the year.”

“THE BULB HORN,” IXION REMARKED, “is all very well for what the secretary in Joseph Conrad’s ‘Victory’ would describe as ‘tame’ people, viz, such as like to live where there are plenty of police, and regard all laws and officials with reverence. But its meek, shortcarrying notes do not suffice for some of us. And in this class of rider the mechorn reigns supreme. Mechorns have saved my life and my freedom many a time, so I must say nothing unkind about them. But they make a raucous noise, like a crow who has been out after wireworm too early on several November mornings running. Moreover, you have to remove a hand from the bar to thump them. Until I invested in a dynamo, I never dreamt of anything better than a mechorn. But as soon as electrical supplies were taken on board I bethought me of electric hooters, and for many miles I have soothed the errant pedestrian out of my path with the dulcet notes of the Dekla horn, operated by a spring push near the left forefinger. It has never let me down, and is altogether better-bred and more musical than a mechorn.”

“MANY OF US ARE CONTENT to take the rain as it comes. If it wets us through whilst out riding we grumble and dry ourselves the best we may. In the same way, if the machine bearings, the plating, the coachwork or the hood suffer through inattention after journeys in soaking downpours, the damage is viewed philosophically. But there is no wisdom in getting soaked through careless selection of clothing, neither is there sense in permitting undue depreciation of the machine to take place through laziness or thoughtlessness. It is just a matter of a little care whether we ride in comfort or in discomfort. To keep warm one must wear leather, but to be perfectly dry oilskin or rubber is absolutely necessary, and to decide which to use is difficult. The Motor Cycle staff are divided in their opinions, but the majority favour rubber for the reason that oilskins have a way of cracking at the elbows and across the shoulders; and unless special care is taken, they soon become useless. Given a long rubber poncho snugly fitting at the neck (or a long rubber coat and a heavy muffler), waders large enough to slip over the boots, an apron on the handlebars and an oilskin helmet, one can face hours of heavy rain and yet keep perfectly dry. On

some occasions, the writer has found the use of a shield extending in front of the knees and brought up over the handlebars a decided boon when faced with a long, wet ride–particularly on a sidecar outfit with bars of the touring type. It is quite an easy matter to make this shield; but if that be irksome, there are several effective designs already on the market. Another inexpensive but useful idea is a cover for the saddle. Instead of allowing the seat to become soaked whilst away from the machine, it is an easy matter to slip on a waterproof bonnet-a ladies’ bathing cap once served for this purpose during a wet holiday. Better still, there is on the market a saddle cover which when not in use disappears into a metal case fixed to the carrier. It might be thought that the provision of a stock hood and screen is all that is required to keep the sidecar passenger dry and warm. But that is not so. Unless more than ordinary care is used to ensure that the hood fits accurately over the screen, and provision made to prevent the rain driving in at the sides, a sidecar ride in wet weather can be meet uncomfortable. Unfortunately, many of the sidescreens sent out by hood makers take far too long to adjust. Manufacturers of sidecar hoods might take a leaf out of the car maker’s book and p1ace on the market hoods and side screens of the style that transforms an open touring car into a coupé in a few seconds. Existing sidecar hoods can be made reasonably watertight by home made sidescreens fitted permanently on the upper part of the hood, dropping loosely over the sides to exclude rain when the hood is in position.’. These loose curtains can be made to clip on to the inside of the body.”

“MOTOR CYCLE MEETS AND RALLIES: Those blessed with youth and the keenness of youth are apt to be a little impatient of that type of club function which falls principally Under the control of the social secretary-annual dinners and other strenuous indoor entertainments always excepted. The energetic club man who rides solo is seldom satisfied with any club fixture which does not fall into the speed contest, or reliability trial class. For the older members who have taken to three wheels, or even four, either from considerations of safety or companionship, social events have their charms. As an opening run for the year’s programme, for instance, a rally of the members at some beauty spot is an admirable event. It enables new models to be paraded and discussed; it gives new members a chance of becoming known and old members an opportunity of renewing acquaintanceships. If such a rally can be undertaken collectively by a number of clubs in one area, the social value of the meeting is greatly enhanced. Perhaps the younger element will feel a certain aimlessness in gathering together at a particular place without a set programme, but a competitive atmosphere or an impromptu hill-climb may easily be incorporated. At the Richmond meet in Yorkshire, it was the custom to give prizes to individual riders for such things as the best-kept machine over a certain age, the smartest. turn-out, the most ingenious item of home-made equipment, etc, in . addition to a club prize for the largest percentage membership present, taking mileage into account. The main thing at such a meet is the necessity of having a definite though simple programme, which must be carried out strictly to schedule. Slipshodness in this respect is fatal.”

ALMOST 100,000 MOTORCYCLES were registered by December.

…and, to conclude this review of motor cycling in 1923, a selection of contemporary ads:

PS: Having noted theQuadrant 48-hour run in this advert I looked out for a suitable illustration and came across this image on a Lambert & Butler cigarette car (back in the days when I was a nicotine addict I used to think L&B were rather upmarket. Who says marketing doesn’t work?)

And then I found a card from the same series illustrating the 1923 Omega which also featured in the block of four ads (from the Blue ‘Un)…

…and then I found some more L&B cards—it’s good to see the 1923 crop in glorious colour…

…and, just because it’s a particularly fine illustration, here’s the Indian…

And here’s an equally fine Indian ad.