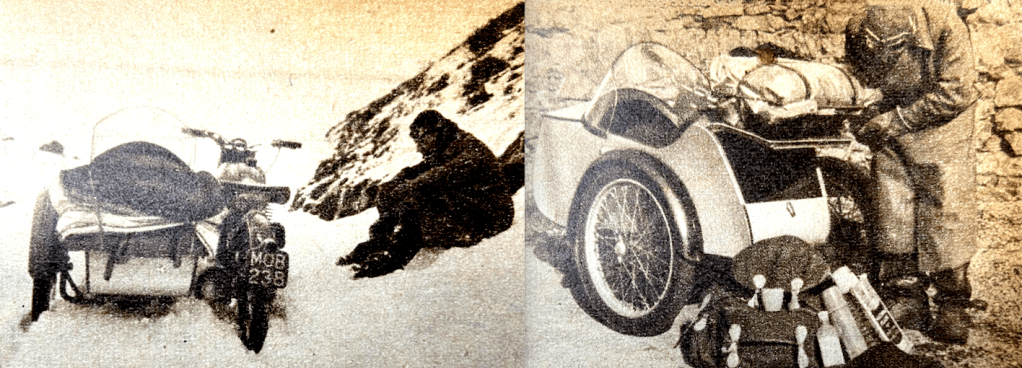

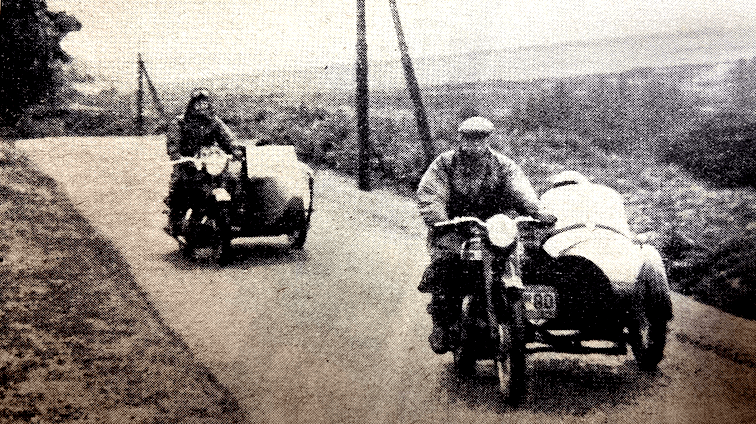

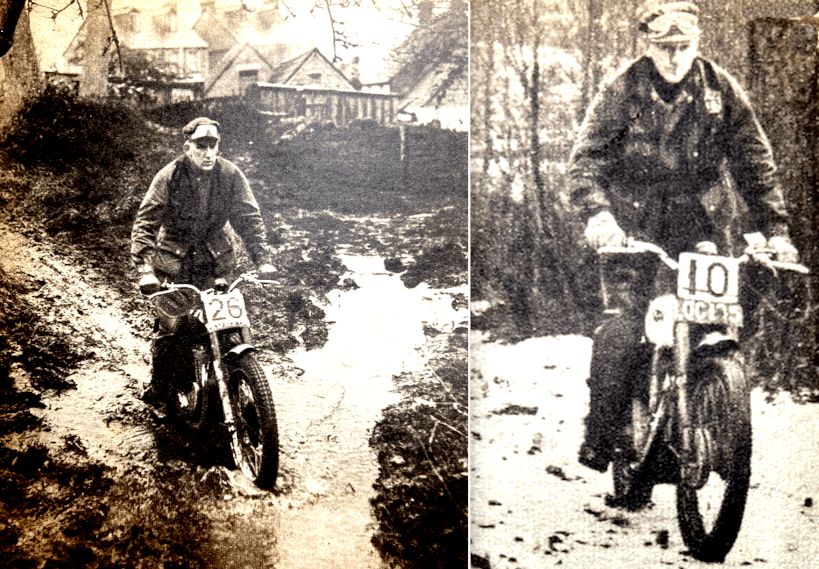

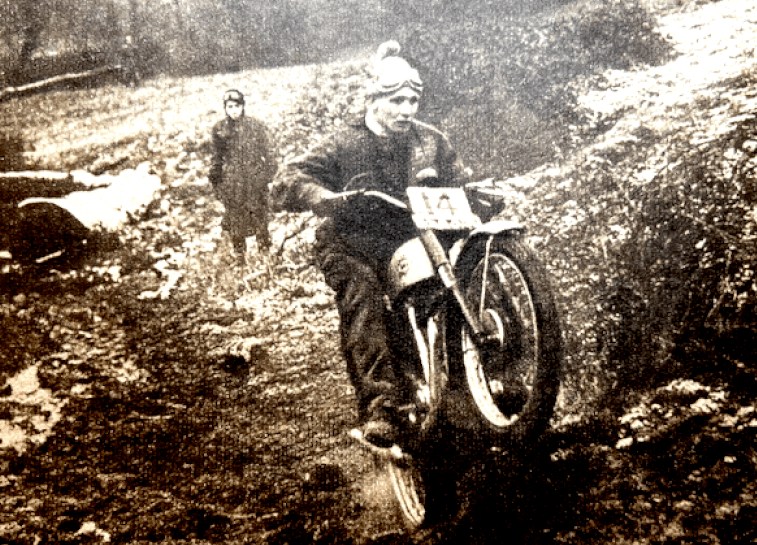

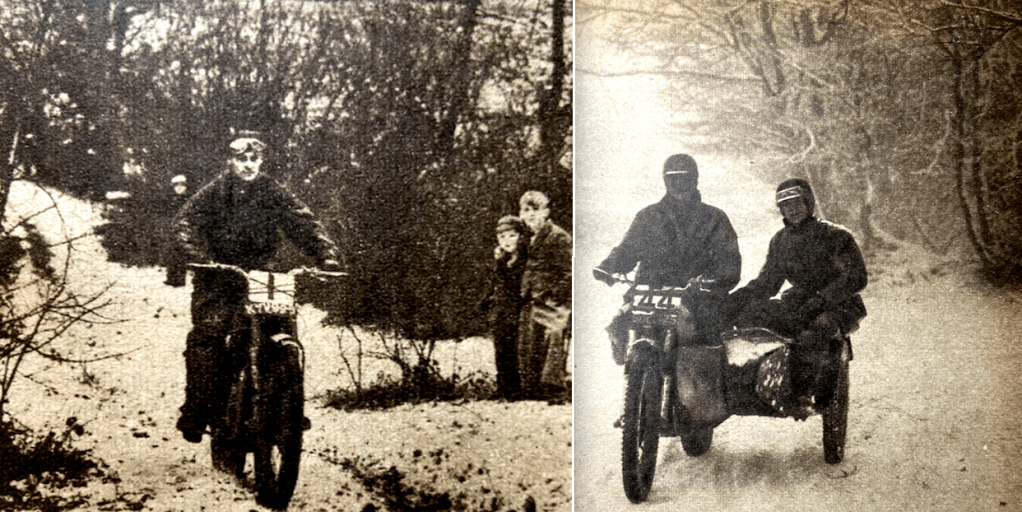

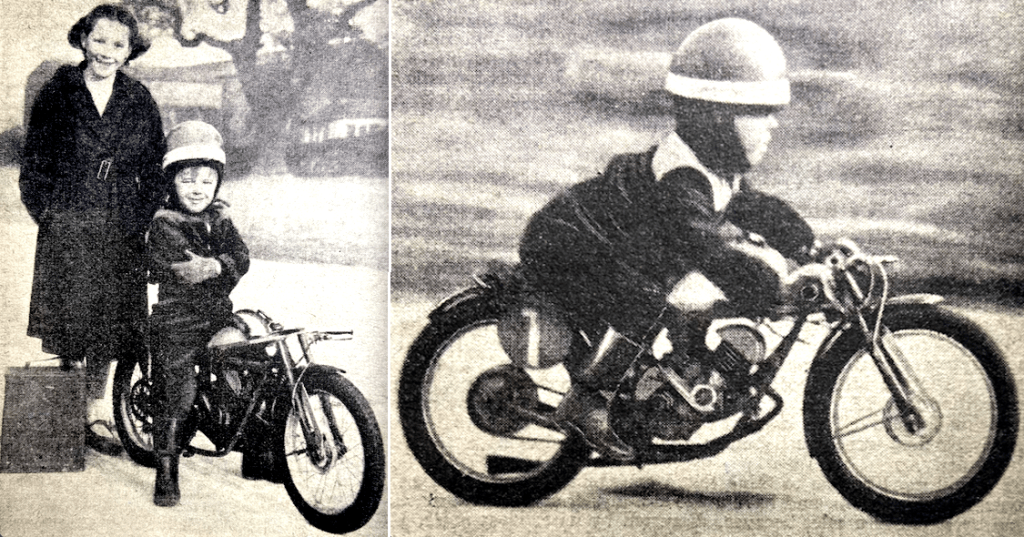

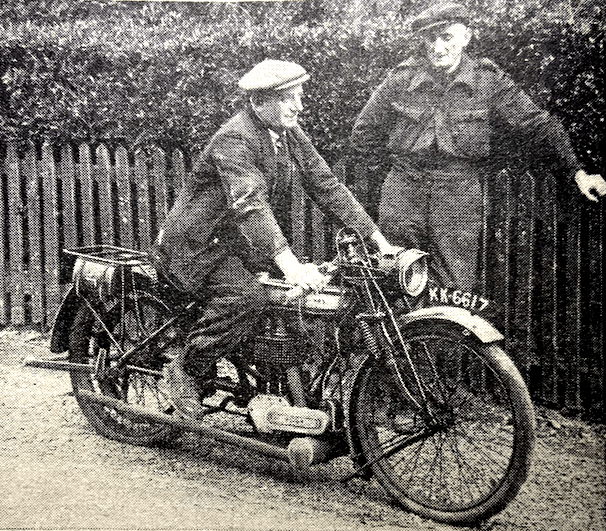

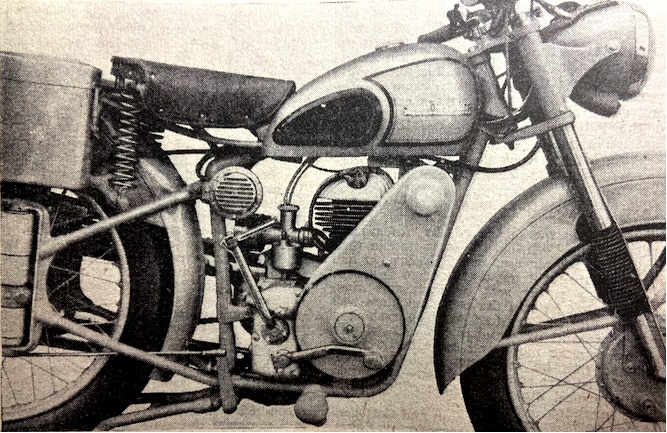

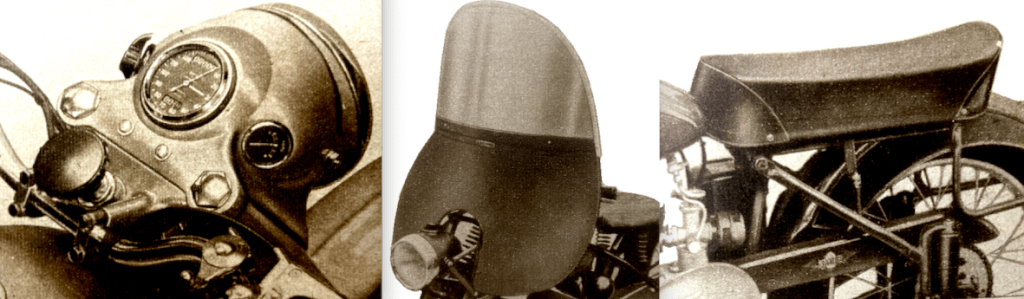

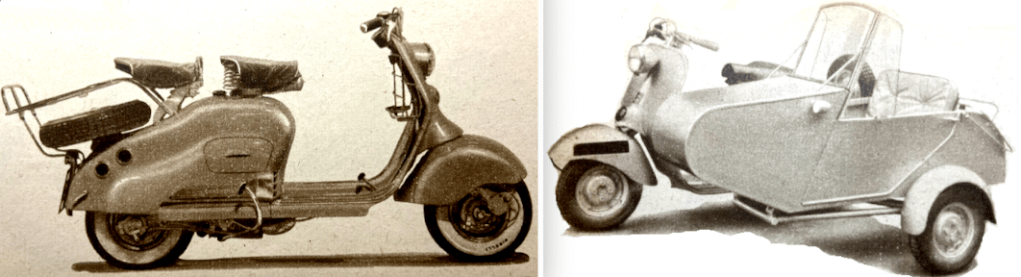

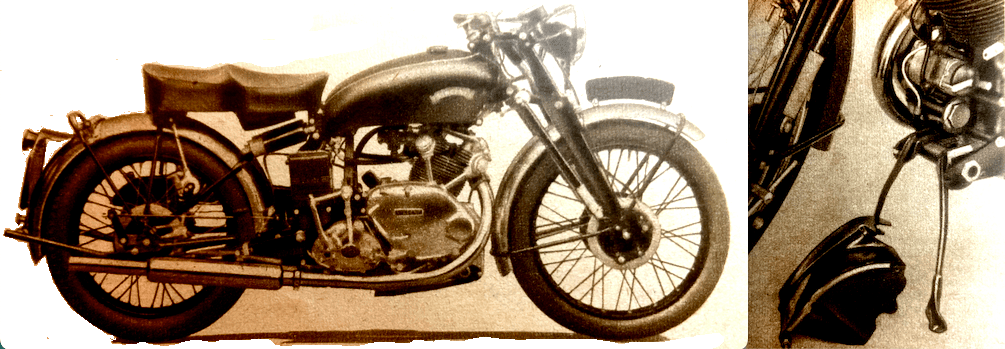

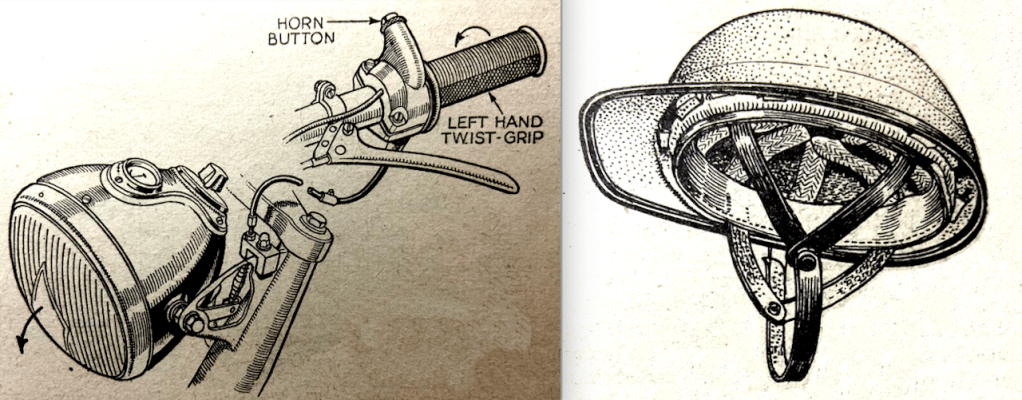

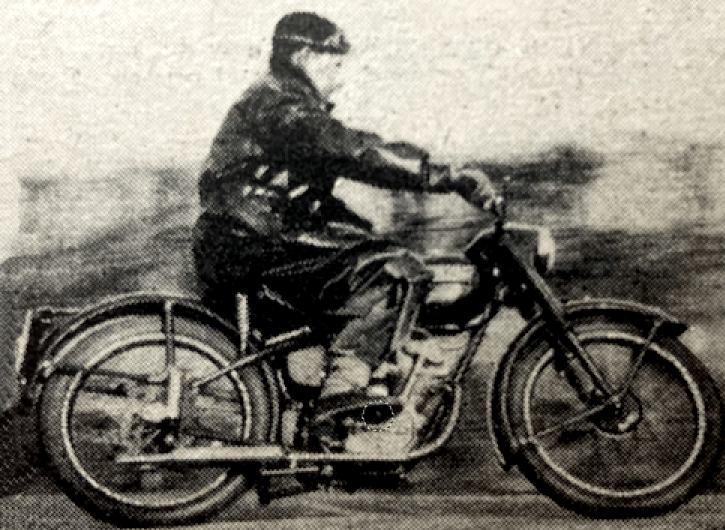

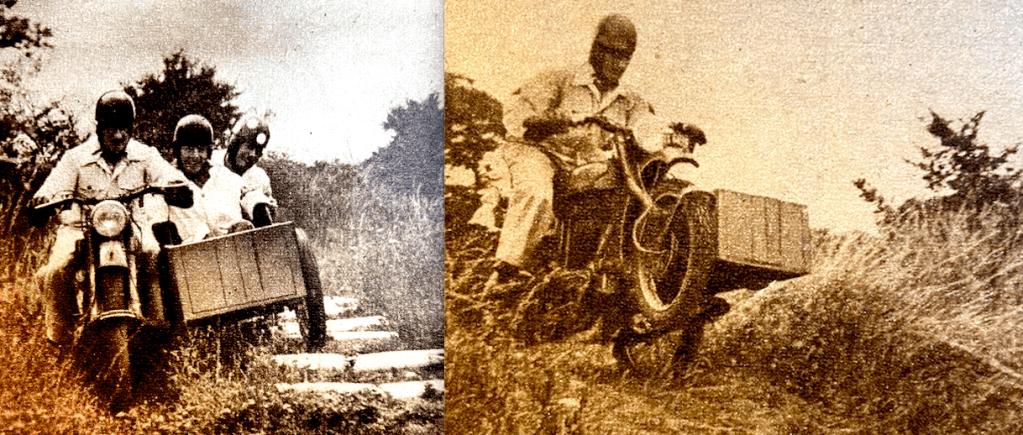

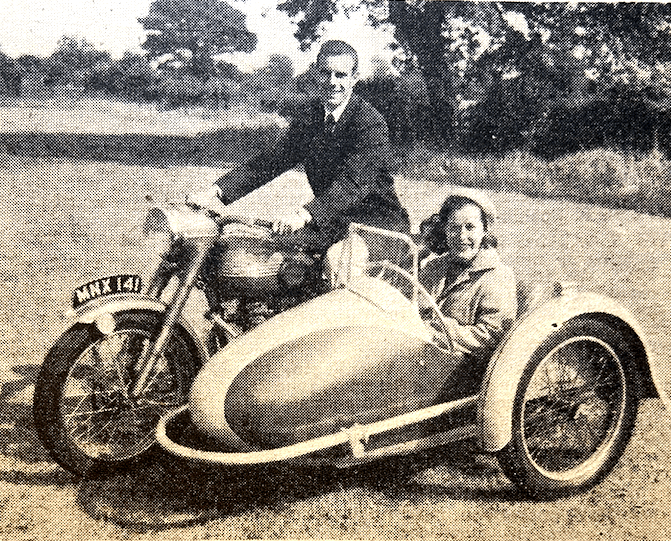

“THE next few days, so far as I was concerned, were unpredictable. How would a small-capacity sidecar perform in North Wales? Would the speed prove so slow as to be boring? Would we find ourselves grinding up the passes in bottom gear, stopping at the top of each to allow a red-hot cylinder to cool? A host of questions crowded the Wilson brain—questions to which I could provide no answer from previous experience…The outfit selected for testing comprised a 197cc James and Watsonian Netherwood lightweight sidecar, which I collected from the James factory after dark. Driving-home was a disappointing experience. The rear chain noisily fouled the top run of the guard; the mixture appeared to be weak and the control was on the right side of the handlebar, where I could not use it in junction with the throttle. There was intermittent backfiring. The brakes—especially the front one—were poor. There was a marked tendency to sideways wobbling of the front wheel and no steering damper with which to curb it. After only six miles in the dark the battery was flat. My spirits were not at their highest pitch, especially since I wanted to make an early start next morning. Two hours later I was in a more cheerful frame of mind. Moving the mixture control to the left, where I could use it, cured all the carburation troubles. After a few crash stops the brakes improved immensely. I found that the sideways wobbling of the front wheel was confined to a period in the region of 25mph. The battery had been discharged because the rear stop light bulb was wired up in reverse. The rear chain rattle I could do nothing with, but that also, I found, only occurred at certain speeds. My companion was Bill Banks, of The Motor Cycle photographic staff. He weights 9½b stone and is 5ft 7in in height, and he had brought his luggage in a large rucksack. He had so much luggage that I wondered whether it would not be better to put that in the sidecar and Banks in the boot. Eventually the rucksack went in the boot, all but filling it, and my leather bag was strapped on the luggage grid, which had been fitted to the door of the boot at my request. We had no fixed idea of how long we would stay away; hence neither of us stinted ourselves in the amount of gear we carried. Also, since Banks insisted on sharing the driving, we were both bewadered and, generally, heavily garbed. When we set off at 10.5 next morning the weather was bitterly cold and it was snowing lightly. Banks, eyeing the open sidecar suggested that at any moment burly men in white coats would appear and put us

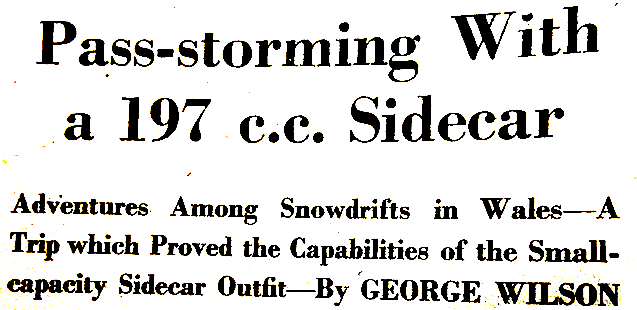

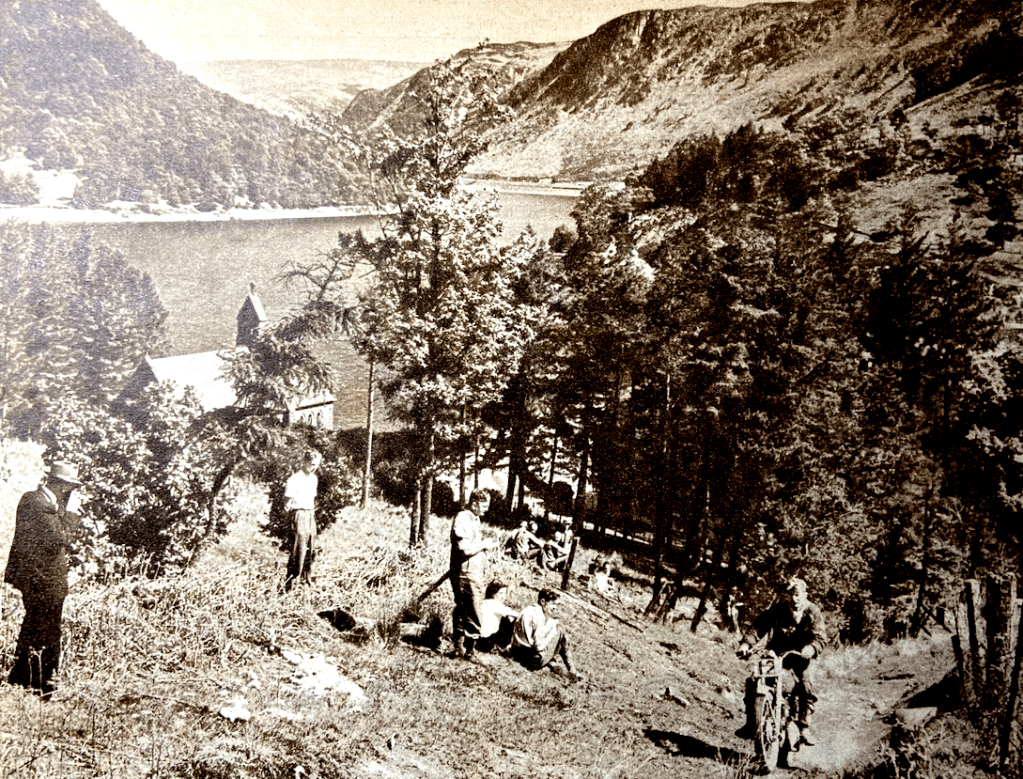

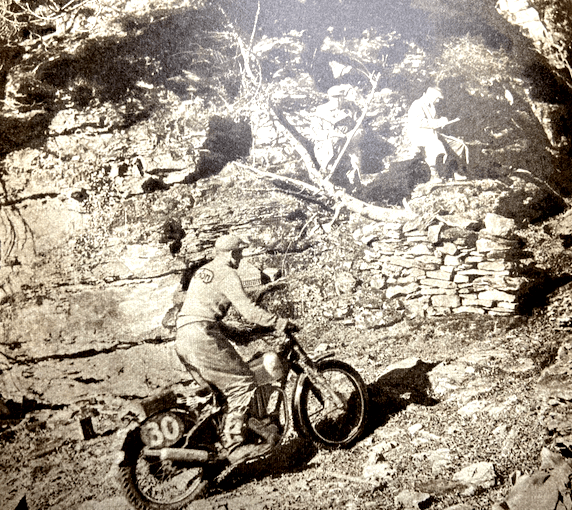

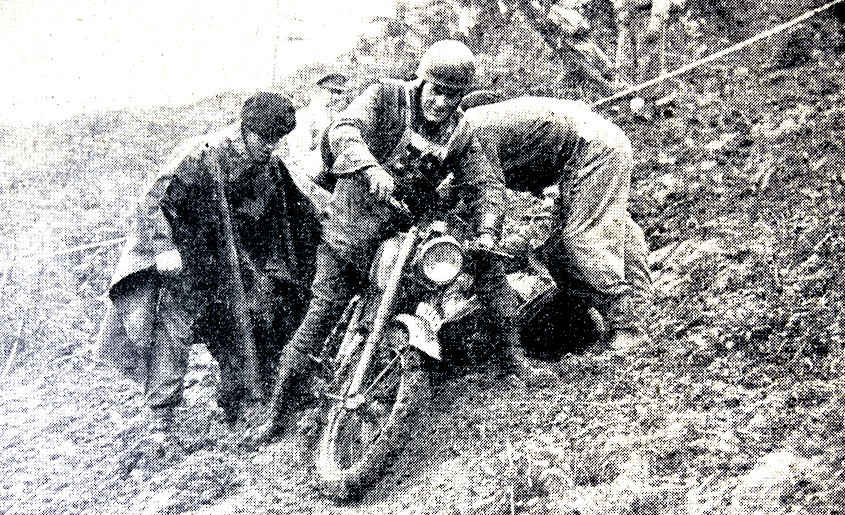

quietly away. We headed west through Wolverhampton to Shrewsbury, county town of Shropshire and once a border fortress against the Welsh. The town has many picturesque streets with timbered houses, but we passed them quickly. Though I was in no way driving ‘on the limit’ we covered the first 30 miles in a few minutes under an hour, and when we made our first stop at 11.35am, we had covered 50 miles exactly. We entered Wales at the Prince’s Oak, which is so called after an incident in 1806, when George IV was introduced to the Principality. We headed for Lake Vyrnwy over slush-covered roads, and stopped for lunch in Llanfyllin (in a cosy dining-room, heated by a coal fire and wherein there stood a single table laid for two). We were climbing now and I was in excellent spirits, for the outfit was exceeding my highest hopes. From Llanfyllin to Lake Vyrnwy by the route we followed, the road was narrow and lay under six inches of rutted snow. There were gradients of 1 in 9 to 1 in 7 climbing to over 1,000 feet and then dropping to the lake (which lies 825ft above sea level). It is the largest lake in Wales, five miles long and nearly a mile wide, and it is the reservoir for Liverpool, 68 miles away. In addition to that, however, it is one of the most beautiful lakes anywhere. We took the road skirting its south bank and headed for the Hirnant Pass—which was included in the International Six Days’ Trials. The Pass is rough and steep, and not generally regarded as a ‘motor road’. By now it was snowing so heavily that an inch-thick carpet fell in approximately half an hour. As soon as the snow stopped we set off through the first gate by the farm of Rhiwargor. Up we climbed in bottom gear, but with power to spare. As we climbed the snow became deeper until, building up under the crankcase and chassis, it brought us to a temporary. stop. On one part of the climb where I estimated the gradient to be 1 in 4, or slightly steeper for a yard or two, we stopped through lack of power and Banks had to abandon the sidecar. At all other times we had power in hand. Eventually, the snow became nearly knee-deep, Banks was breathing like a locomotive, and it was impossible to carry on farther; so we about-turned. At the road again we retraced our wheel tracks to Llanwddyn at the eastern end of the lake and drove by way of Pont-Llogel to Pen-y-bont, thence by way of A458 to Divas Mawddwy—which is at the foot of Bwlch-y-Groes, said to be the highest motoring road in Britain. The way to Pen-y-bont was through typically Welsh going, embracing narrow, twisty lanes with steep gradients and sudden, blind corners. Intermittently, the surface was a sheet of wet ice, but we sped over it with impunity. By now we had been able to assess the capabilities of the little Villiers engine. From its performance on the Hirnant it was obvious that, although newish, it was not going to seize. So I pressed on, buzzing the engine hard (going up to 30mph in second) and maintaining the highest speed possible. Had the outfit been powered by a 1,000cc engine I should not have wanted to go faster in similar circumstances. And in spite of the way I was driving, the engine was not becoming unduly hot. At Dinas Mawddwy we were told that the Bwlch, too, was impassable because of deep snow so we reluctantly abandoned the idea of tackling it. We turned, instead, towards the Tallin Pass which runs from Dinas to

Dolgelly. The pass is surrounded by giant peaks with, on the left, Cae Afon (2,213ft) and Waen Oer (2,197ft) and, on the right, Craig-y-Ffynnon. From approximately 500ft at Dinas, the road rises to 1,178ft at the highest point. According to the RAC Handbook, the average gradient is 1 in 7, the maximum gradient 1 in 5, and the length of the climb one mile. By now the light was almost gone and Banks was driving. In the main, the ascent was accomplished in second gear (which has a ratio of 9.64 to 1), but bottom gear was required for two sections near the summit. In fact, the 18.46 bottom gear was lower than the gradient required. There was power to spare at 15-20mph. The descent was almost as steep as the climb, and the cold night wind cut into us with the keenness of a razor edge. At the bottom, where the road levelled out, Banks opened the throttle for the first time in 1½ miles. There was no response from the engine. He repeatedly blipped the throttle—still no response. In the sidecar, my immediate thought was ‘dud plug’. Without more ado, I nipped out of the sidecar, opened the tool box and made a rapid plug change. The cylinder was quite cold, and before kick-starting I drew the mixture control to the rich position. The engine fired instantly and we were off again but without, for a then unknown reason, any current reaching the sidecar bulb. I found the next morning that the wire had been nipped by the left sidecar spring. The plug had not whiskered or oiled, incidentally; my guess was that the engine had gone cold on the descent and required a rich mixture on which to restart. Dolgelly was inhospitable that Saturday night. We tried three hotels before finally settling in for the night at ‘The Clifton’ and dining at ‘The Ship’. The next day was one of torrential rain. We left Dolgelly at 11am and took the coast road to Barmouth. The distance is roughly 10 miles and the road well-surfaced. It is a twisting 10 miles with sudden, steep gradients, up which the James sang happily in second gear. One of the most popular of the Welsh resorts, Barmouth faces the open sea. It presented an uninviting aspect to Banks and me, however, with mist swirling down from the heights and over the sea, and rain lashing down furiously. We had lunch in Harlech, the ancient capital of Meirionydd and famous for its ruined castle, which is said to date from the 13th century. Nowadays, incidentally, Harlech College is an important centre of working-class education. The rain increased in intensity until it was coming down in a solid sheet. As we splashed north, the road climbed higher and higher as we went through Penrhyndeudraeth and Maentwrog. The James, I felt, really proved itself. My coat seams began to leak so I gave the outfit the gun and drove the 16 miles to Maentwrog on full bore. I did not stop there either. Ahead lay the Crimea Pass which, again according to RAC Handbook, has an average gradient of 1 in 9 and climbs for three-quarters of a mile. The steepest gradient is 1 in 6. I tore at it with the James sounding as if every bee in Christendom was waging war in its silencer. The bulk of the climb was achieved in second and the steeper parts really required, again in this case, an intermediate gear between bottom and second. Blaenau Festiniog, with its huge slate piles bordering the road, presented a dismal picture and we did not pause for it. Instead, we headed for Elen’s Castle Hotel, Dolwyddelan, where, as Signpost had suggested, we received a Royal welcome. We spent two nights there, incidentally, and I thoroughly recommend the hotel to motor cyclists. The terms are reasonable and it has a modest and homely touch that is generally absent in more pretentious establishments. The next day was the one during which, I feel, we achieved our tour de force. We climbed part of Mount Snowdon. From Dolwyddelan we ran north to Bettws-y-Coed which, this morning, was bathed in sunlight. Bettws-y-Coed means, I am told, chapel in the trees. The town nestles snugly in the wooded valley of the Conway. It is said that the surrounding district spots contains more beauty spots to the square mile than any other region in these Islands. But we were itching to get a glimpse of Snowdon and pressed on to Capel Curig, famous headquarters for mountain climbers. From here we took the road to Pen-y-Gwryd and then climbed steeply to Pen-y-pass, from where we turned off the road. Our ascent had begun in earnest now, though we had already been climbing steeply from Pen-y-Gwryd. Below us spread a valley of unbelievable splendour. From Pen-y-pass there are three tracks up Snowdon, the best known and roughest of which is, I believe, the Pig track. We were advised to avoid this and took the track on the extreme left, which climbs steeply over the shoulder of Snowdon to the stone causeway over Llyn Llydaw, a mountain lake. Loosely and roughly surfaced, the track runs south at first and then west, passing, on the left, Llyn Teyrn (a small tarn). At first, the snow was comparatively little trouble to us, and the James took the gradient in its stride. As we climbed, however, the snow became steadily deeper. Occasional drifts brought us to a halt. Then the drifts became more frequent; so much so, indeed, that we decided to turn back. After all, we argued, we had proved to our satisfaction that the gradient could be successfully defeated. But we were goaded on by the sight of Llyn Llydaw, a mile away, round a turn in the track. The sun glinted on the peaks of Crib Goch (3,023ft) and Lliwedd (2,947ft), and on the gossamer clouds resting lightly on Y Wyddfa (3,560ft); Snowdon’s loftiest peak seemed within easy striking distance. In fact, we reached the stone causeway over the glistening, crystal-like mountain lake without more difficulty. We were at journey’s end—for us, anyway. Ahead towered Y Wyddfa, accessible now only to those with mountaineering equipment. I wanted to press on over the causeway, suggesting that I could keep the sidecar airborne, since the causeway was too narrow for our track. Whereat Banks created more than a bit, muttering something about over his dead body; he wasn’t going to walk back to Dolwyddelan if I chose to drown; so I dropped the idea. By now we had been severely bitten by the climbing bug. We were back at the Pen-y-pass Hotel in time for lunch, then we headed for Llanberis and Llyn Padarn, another beautiful Welsh loch which forms the centrepiece of a setting that might well be situated in Austria, Switzerland or northern Italy. At the northern end of the loch we turned off the main road and took a steeply climbing secondary road by way of Deiniolen and Rhiwlas. Then, instead of carrying on to Pentir, we took a track over Douglas

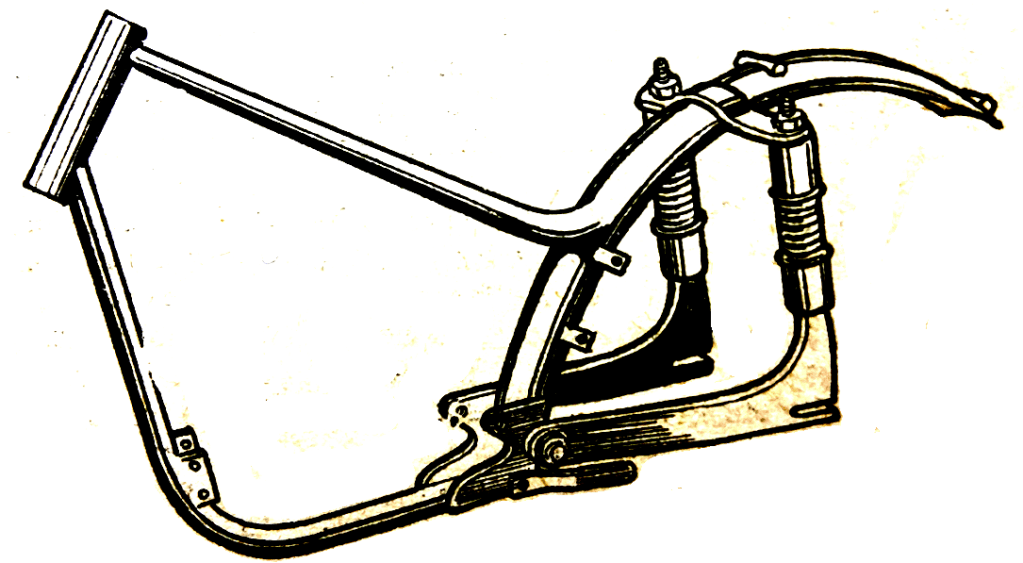

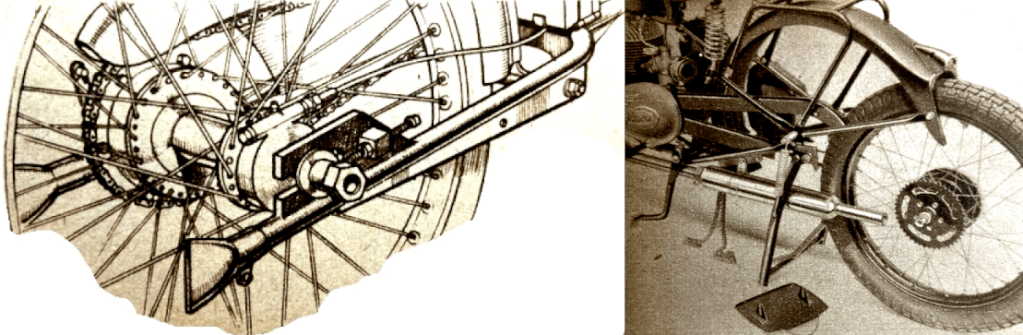

Hill—a track that is marked on nothing less than one-inch Ordnance Survey maps. On the way to Rhiwlas, and through it, we had climbed for something like a mile in bottom gear. When we left the road the track steepened, but still we had power to play with, the engine turning over quite easily (in bottom gear) on about half throttle. At the top we had to open a closed gate. While we were doing so, the sound of a four-stroke single being blipped noisily could be heard faintly in the still, winter air. The sound grew louder, and there appeared from another gate JS Jones (490 Norton), of the Colwyn MC, who scratched his head in amazement when he saw us. We chatted, and with Jones’ blessings ringing in our ears, pressed on over what had once been a trial section—but we had no bother. By now the afternoon was ageing rapidly. We drove hard to Tregarth and Bethesda, and by way of another Welsh lake, Llyn Ogwen, back to Capel Curig, Bettws-y-Coed and Dolwyddelan. Before putting the outfit away I cleaned it, adjusted and oiled the rear chain and took up the brakes—and that was that. We left Dolwyddelan at eleven o’clock the next morning and returned by way of Bettws-y-Coed, Corwen, Llangollen and Shrewsbury to Birmingham. We had the advantage of a good following wind and gave the outfit its head, letting it run up to 50mph wherever possible. We were only once overtaken—and that was by a Lagonda car, which was being beautifully driven. Including a comfortable lunch stop and several other stops to take photographs, we were back in Birmingham at 3.20pm. The distance covered was 111 miles. Our total mileage for the test was 359 miles. Petrol’ consumed was 5½ gallons, giving a petroil consumption of 65mpg. Under almost any conditions we could average 30mph without apparently flogging the engine. Altogether, the performance of the outfit far exceeded my expectations. Criticisms? These are few and certainly not concerned with the Villiers engine-gear unit, which was well-nigh perfect in every way. Even the clutch is fully up to its job when the machine is used with a sidecar. The chief criticism concerns the brakes. If, as I for one visualise, the lightweight sidecar outfit is to have a bright future, bigger front brakes must be regarded as essential. The only other real query concerns the steering. I mentioned earlier that the front wheel had a tendency to sideways wobble at certain speeds. This will have to be overcome by investigation of steering geometry and the position of the sidecar wheel in relation to the rear wheel. On all other counts I liked both the machine and sidecar. The machine controls are light and the riding position near perfect. Incidentally, in order to see whether we had caused any damage I later went over the outfit carefully, even lifting the cylinder and head to inspect the piston. Never have I seen a piston in nicer condition. Our top gear ratio was 6.93 to 1. The gear box was the standard Villiers close-ratio type, and the rear sprocket was a James product with 52 teeth. The original plug, which was entirely satisfactory, was a Lodge HE IQ. The sidecar, on first acquaintance, gave the impression of being too short and too narrow in the nose. Yet, after our experience, neither Banks not I would have it changed in any way—although ladies might prefer a door, in order to simplify entry and exit. Still, doors cost money, and the Netherwood, as it stands, is attractively priced. The boot dimensions are adequate and the grid which I had specially fitted completely overcame our luggage problems. The Perspex screen is well shaped and at an angle which deflects rain and draughts over the passenger’s head. All things considered, the 197cc sidecar outfit is a good proposition—a far better one than the majority realise. If the criticisms I have raised are attended to, there is no reason why there should not be a tremendous boom in this sphere during austere years that may lie ahead.”

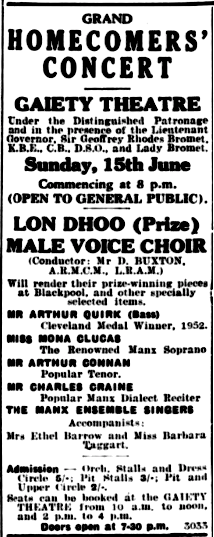

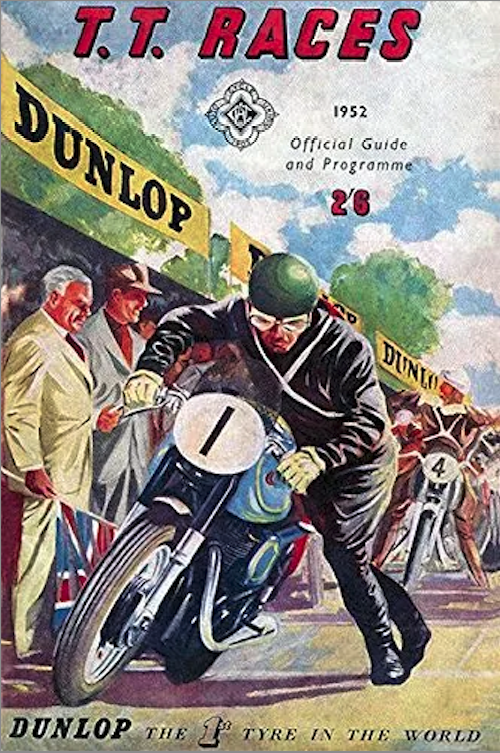

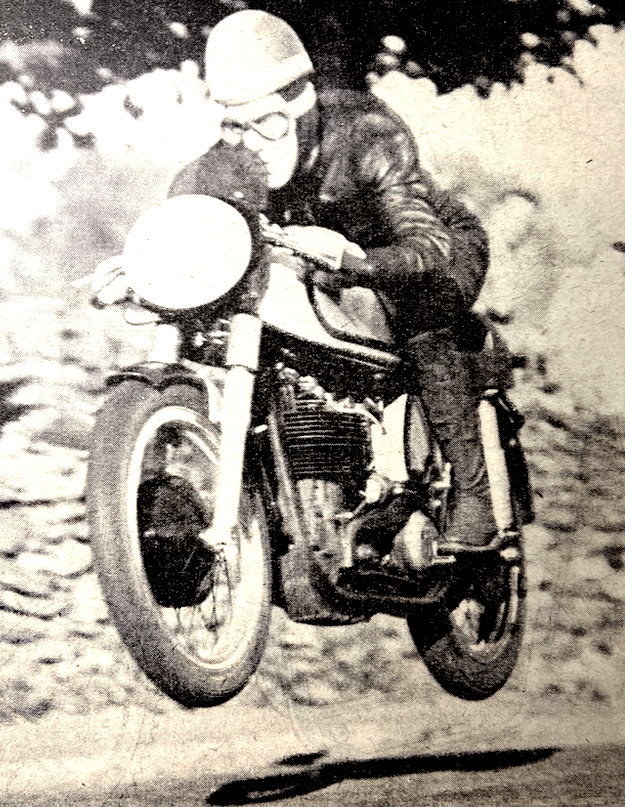

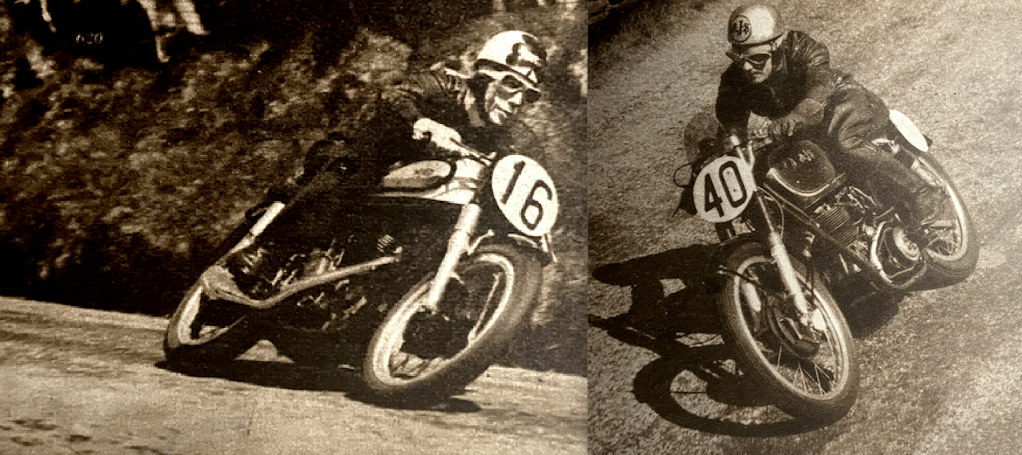

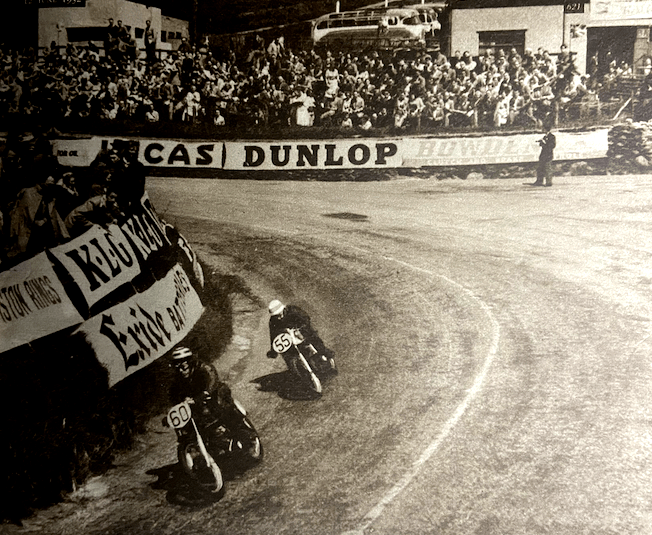

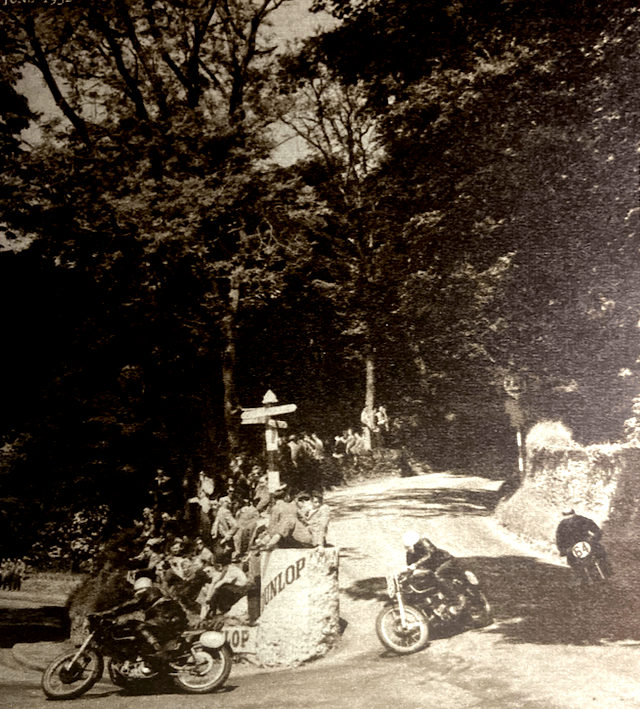

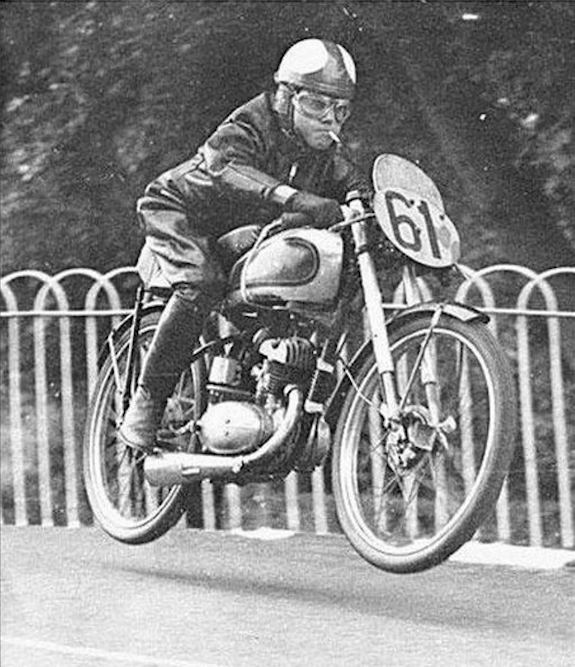

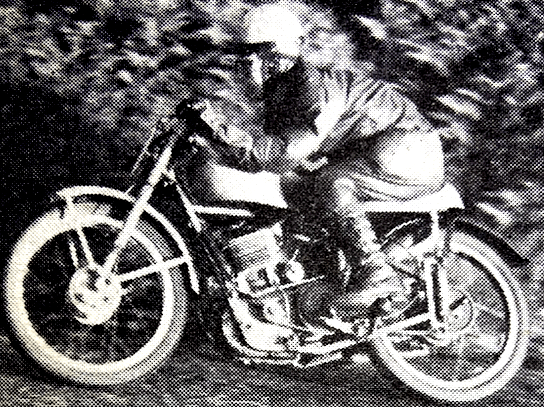

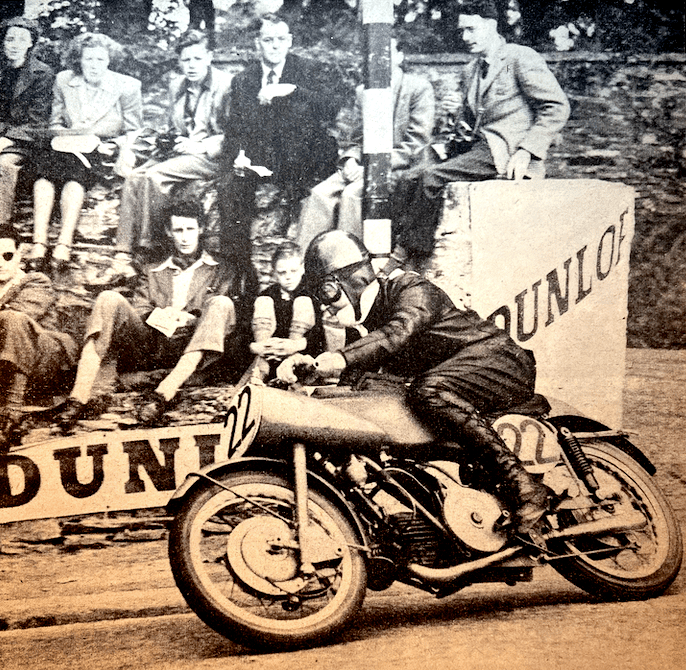

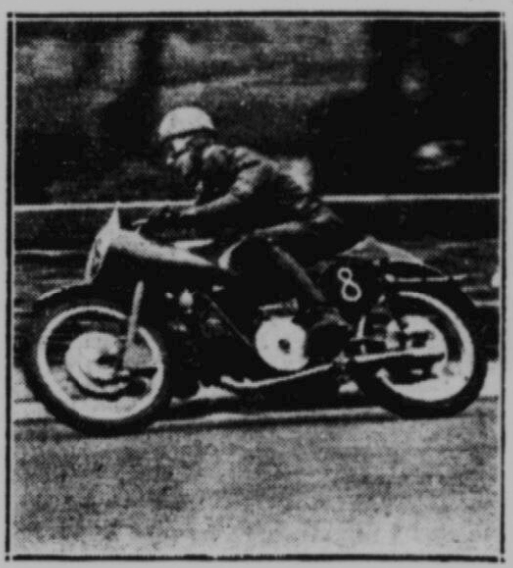

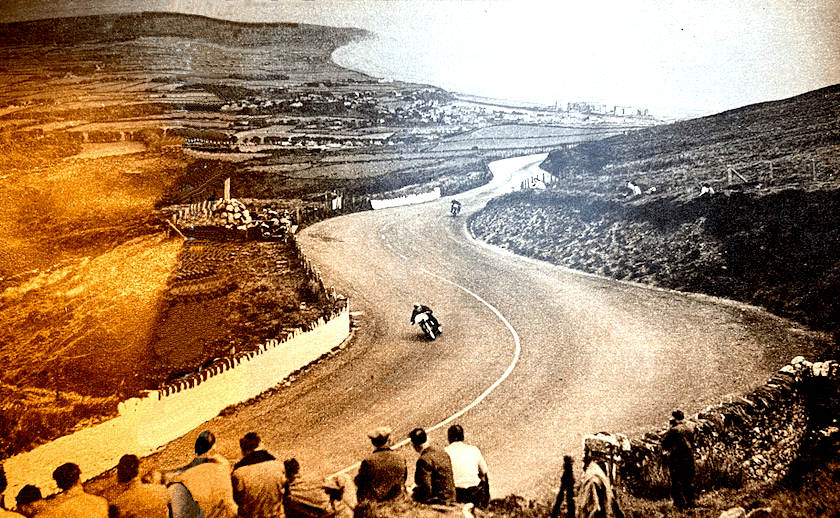

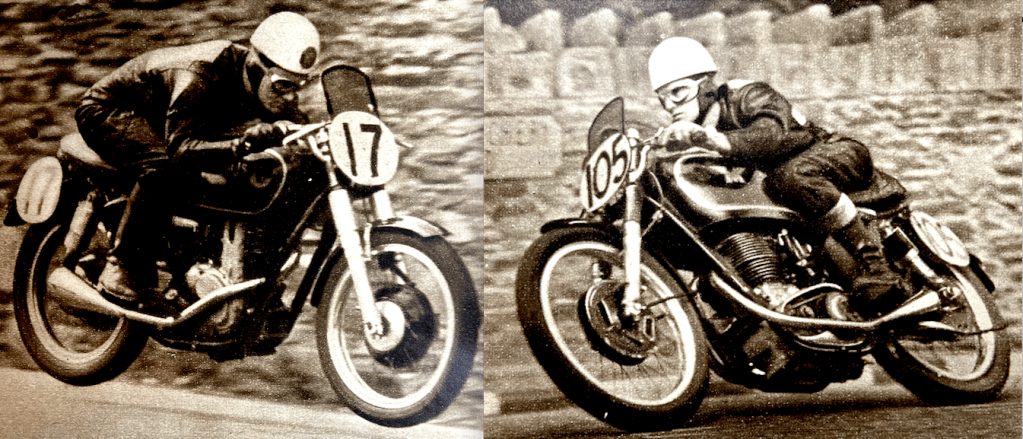

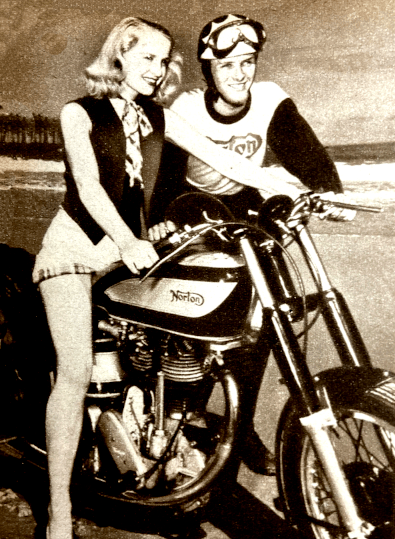

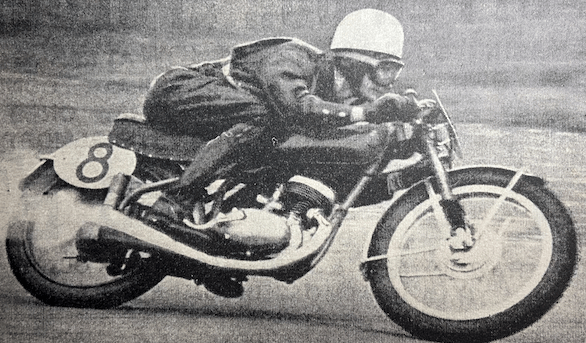

“ENTRIES FOR THIS YEAR’S international TT races total 240. There are 83 for the Senior (500cc) event, 94 for the Junior (350cc), 34 for the Lightweight (250cc), and 29 for the Lightweight (125cc). The total is 52 below the record set last year, but this fact will have no influence on the success of the events, since there is an adequate entry for each. The lists do not show as much variety in national representation as could be wished. Nevertheless, a warm welcome is extended to entrants and riders from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Southern Rhodesia, Ceylon, Denmark, Spain and Italy. It will not pass unnoticed that a rider from Australia and one from New Zealand figure in Manufacturers’ teams. With entry lists for the Clubman’s Senior Race at 97 and for the Junior Race over-subscribed at 105, there is a total of over 400 entries for the various events to take place during the Isle of Man ‘week’. Good racing is in prospect.”

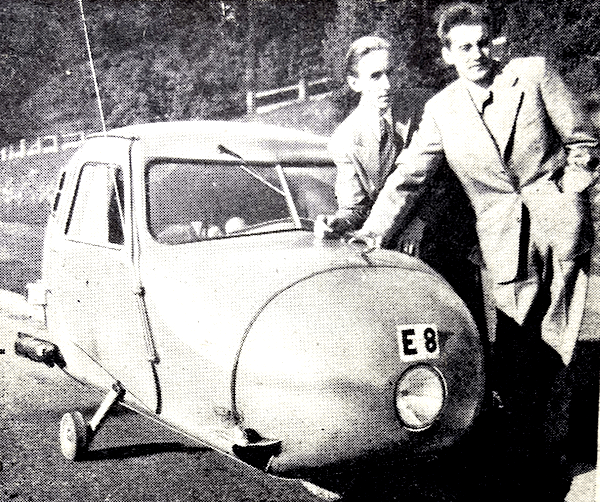

“A DISABLED MAN was recently fined at Brighton for travelling at 41mph on his invalid tricycle! I suspect he is being bombarded with letters from other cripples eager to learn the make of his projectile. But I beseech these sporting invalids to mind their step. Time was when all disabled men had to purchase their mo-chairs out of their own pocket. Now that some State assistance is available, any exuberance on the road might conceivably lead to a micro-motor of clip-on type being substituted for the present more potent engines.”—Ixion

“‘MEDICO’ OWNS A BLACK SHADOW, a Jowett Javelin and a Healey. His mature verdict is that a really long run, ie, up to 400-500 miles in the day, produces far more physical exhaustion on two wheels than on four. Though his two-wheeler is fully sprung, the contrast necessarily pivots on comfort. I have personally noted the same facts, and have always failed to reach a satisfactory analysis. For example, I remember covering 514 miles on a summer’s day (Glasgow to the South Coast), seated alone in a small sports car with not very fat tyres and quite simple suspension. I finished physically fresh. But I have never done 500 miles in the day on two wheels without feeling so punished that a boil-ing hot bath was required to remove the stiffness. Why? Is lack of support for (a) the shoulders, and (b) the hams, the main cause? There seems to, be little difference in the severity of bumps or the total of vibration. Nevertheless, there is a pronounced contrast in the total punishment…Medico accurately remarks that motor cycle head lamps are very substantially inferior to car dittoes, and explains why motor cycles cannot easily put up such high averages over a long distance. Technically he is correct. But I am all against long-distance high averages including any night element at all, nor do I really yearn for more potent motor cycle head lamps. There are a dozen arguments against them—high cost, considerable weight, bigger dynamos, bigger cells, and above all, the risk of young fools abusing so fierce a beam. To be frank, all really powerful head lamps are a confounded nuisance to the majority of road users; and I doubt whether any of us should use lamps substantially exceeding a reasonable level of illumination. I have often wished for a head lamp with a broader and more diffused beam, but I have no wish for a searchlight type.”—Ixion

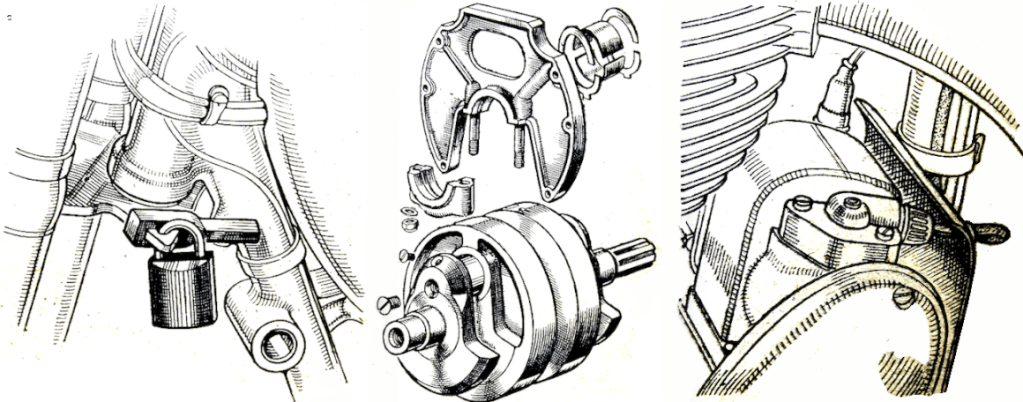

“EVERY INSURED PERSON should read his policy carefully, especially the clauses in small type. Some motor cycle policies apparently furnish no cover against theft unless the complete machine is taken. Even the tariff companies’ policies do not cover loss of ‘accessories and spare parts’ if the motor cycle is not stolen at the same time. As a sample of what must be an extreme case, the other day a reader was in a cinema. At the end of the programme he found that somebody had pinched his cylinder! He could obtain no payment from his insurance company, though they would have forked out a large sum if the complete model had been stolen, By the way, it is well to agree with your company as to the current value of the model, and the figure should be reviewed once per annum. Many owners have received powerful shocks after a theft, on discovering that the current value under the policy is far less than they supposed.”—Ixion

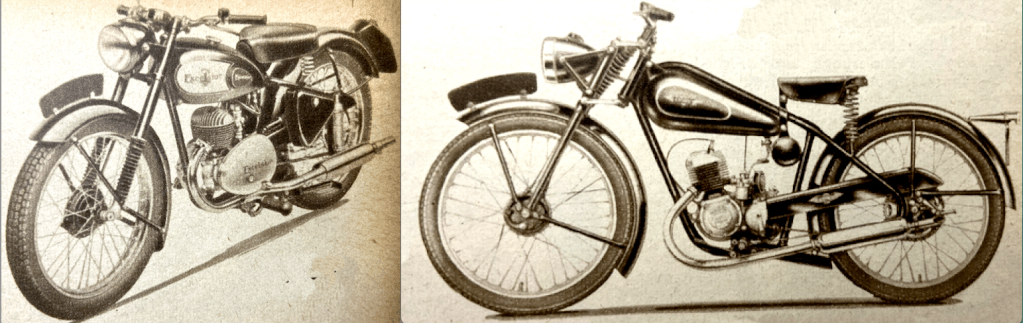

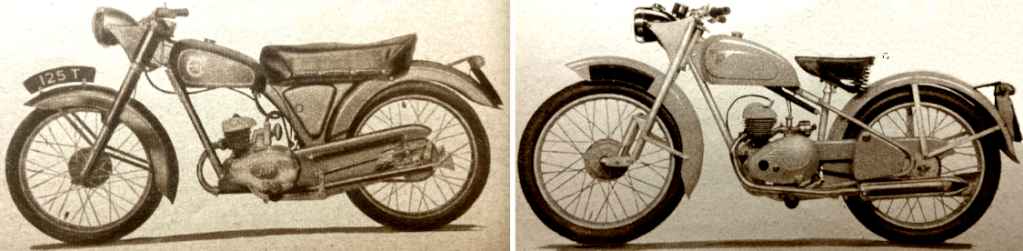

“THE VICES AND VIRTUES of a lightweight are miniature replicas of the corresponding traits of the bigger models. In the comparison, lightweight virtues are, perhaps, greater than those of the big ‘uns. Their special virtues are lower cost, lower depreciation, easier handling with a ‘dead’ engine, less temptation to speed, and less temptation to ‘cover ground’ as opposed to enjoying a trip. Today, the market bristles with magnificent lightweights, so good that machines between 120 and 200cc are coming to be regarded as rather powerful! Perhaps all these benefits may be even more appreciated when we emerge from the present transition age, and British finances find some kind of austere equilibrium. It may well be that fewer folk will then be able to buy 500cc roadsters, and the little ‘uns may become our staple fare.”—Ixion

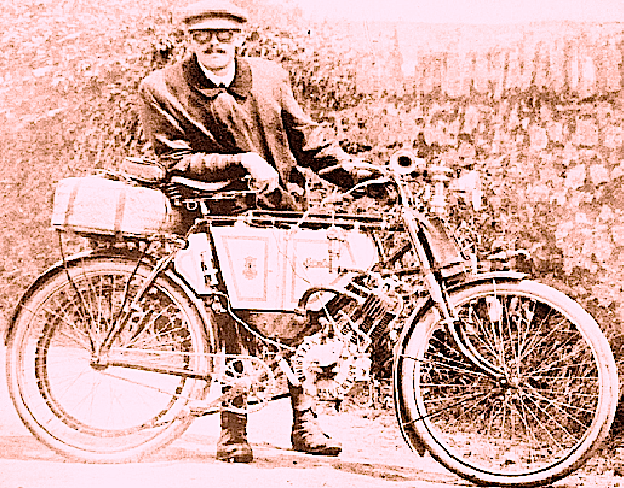

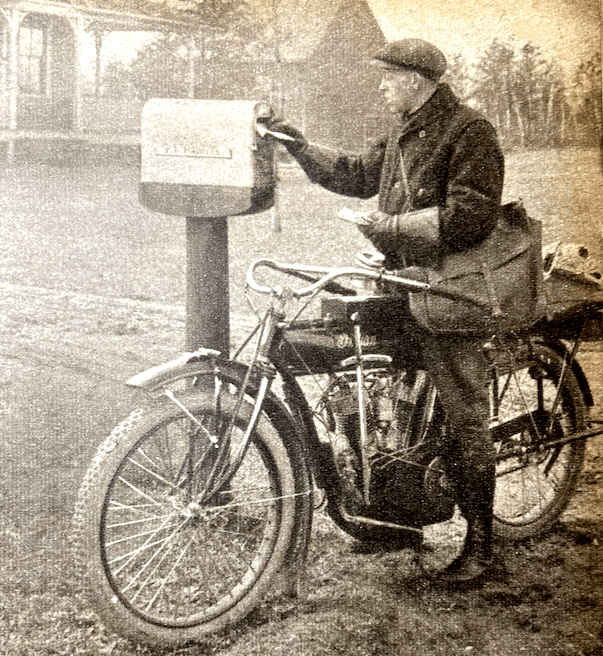

“I WAS CHATTING to an old-timer who rode motor cycles over half a century ago. The 98cc brigade were our topic. He remarked that their performances were better than his first 500cc models of 50 years ago; that they were more comfortable; better climbers; more reliable; and (until the war generated wild inflation) actually cheaper. He speculated on what might have happened if, eg, a 98cc Villiers-engine autocycle had been produced by some precocious genius as far back as 1902. His first reaction was that all British infantry would have been mounted on it, together with an immense number of civilians whose avocations entail daily travel. He had been an industrial physician. He recalled a Midland town where the male and female hospital wards were normally packed with factory hands suffering from gastric ulcers. He ascribed these ulcers to too short a dinner-hour. The hands scurried home, often on foot, and gulped down indigestible food far too fast, lacing it with pungent sauces and pickles because rapid labour in stuffy shops had killed their natural appetites. Gastric ulcers were often followed by tuberculosis. The 98s could have stopped all these disasters by rendering labour mobile at minimum cost and at minimum physical effort. That factor has played a great part in developing lightweight motor cycles on the Continent, and in determining Government policies towards lightweights in terms of tax, licence, and so forth. ‘Lightweights,’ quoth my physician, ‘are cheaper than hospitals and sanatoria.'”—Ixion

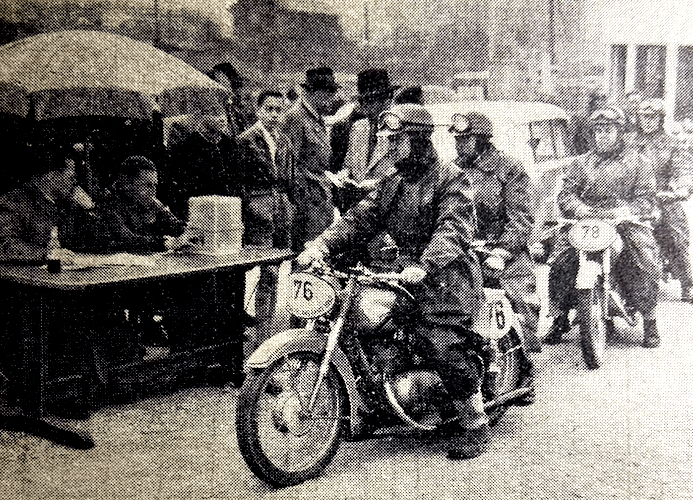

AN ENORMOUS ENTRY—no fewer than 333—compelled the Streatham club to plan a comparatively simple course for their annual Half-crown Trial (open to South-Eastern Centre) held near Liphook last Sunday. Even so, they achieved the ambition of all organisers when the commendably rapid working out of results revealed that only one competitor had completed the 32 sub-sections without loss of marks. Delays were almost non-existent, and the handling of this large entry was a credit to all concerned. RESULTS Best Solo: Sgt R Rhodes (348 BSA), no marks lost. Best Sidecar: BT Welch (497 Ariel sc), 3 marks lost. Best Novice: D Heryet (347 Matchless), 6. Best Team: Sunbury MCC—AGL Bryant (348 BSA), 3; W Conway (249 Triumph), 3; J Liner (348 BSA), 8; total 14.”

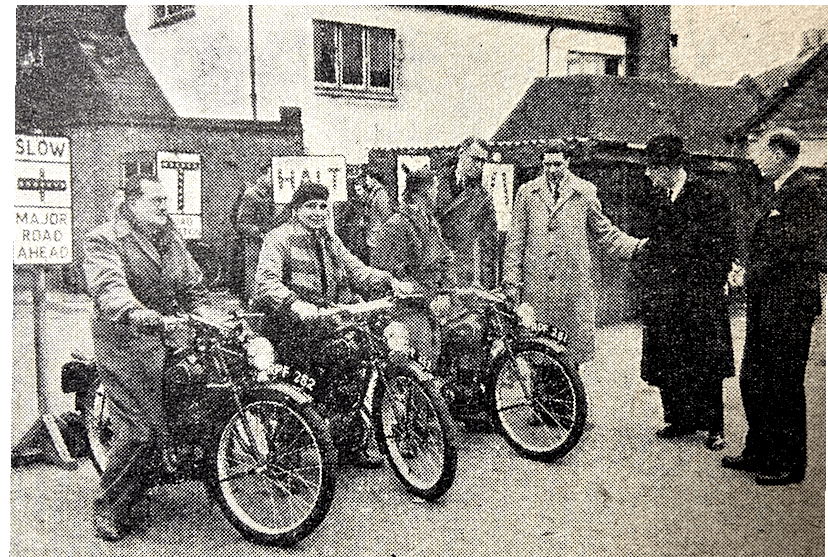

“A 122CC NORMAN MODEL B1 is to be presented by Norman to the Waterlooville. Club for use in connection with the RAC-ACU Training Scheme.”

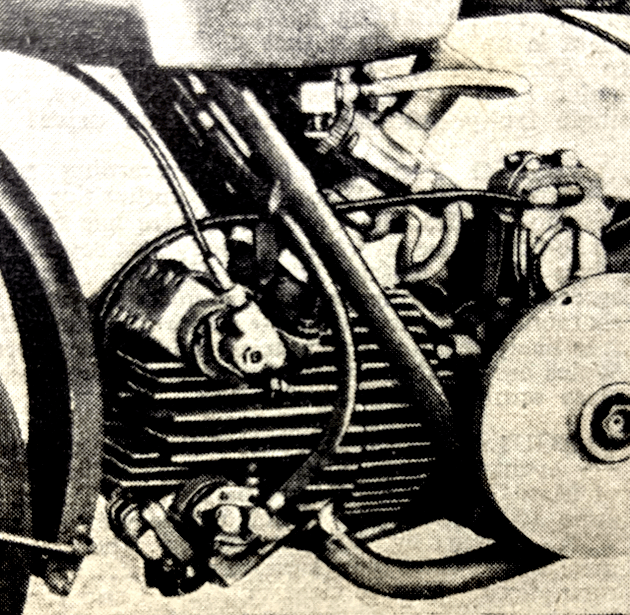

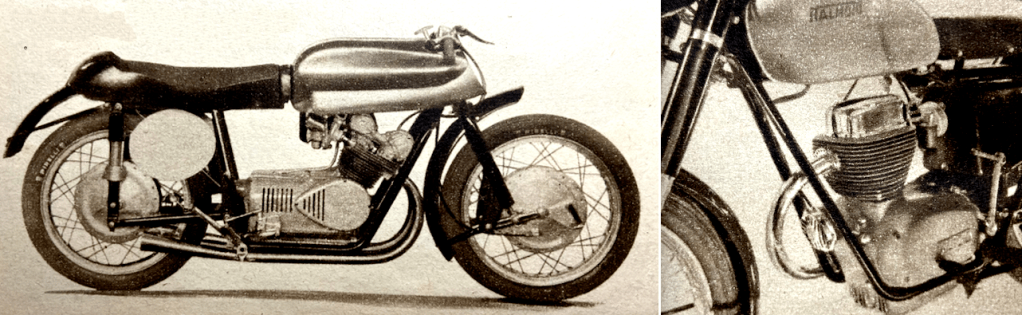

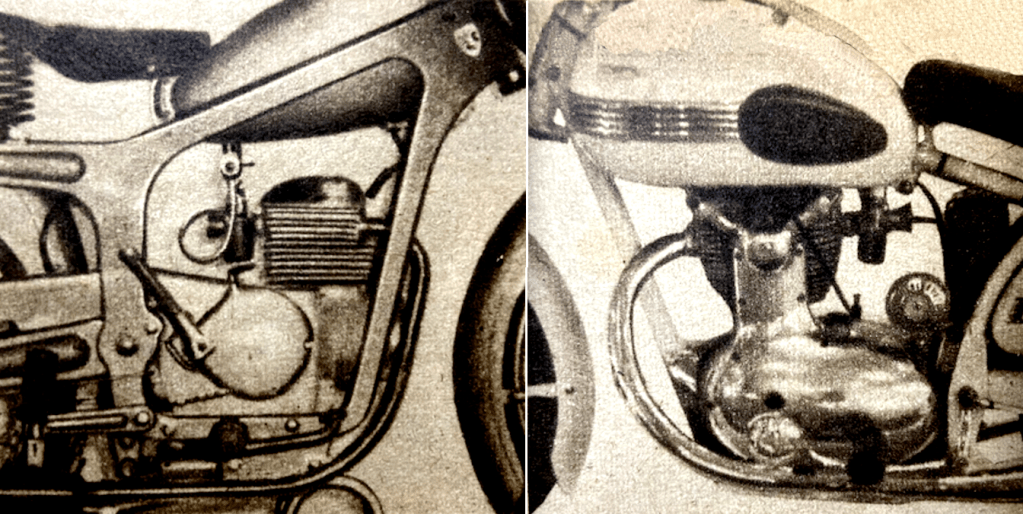

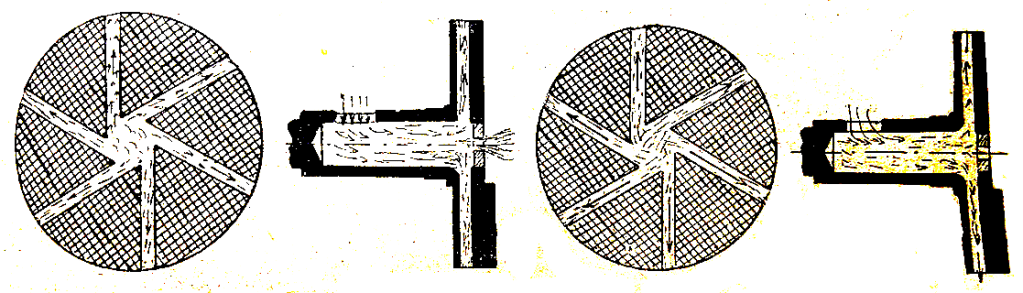

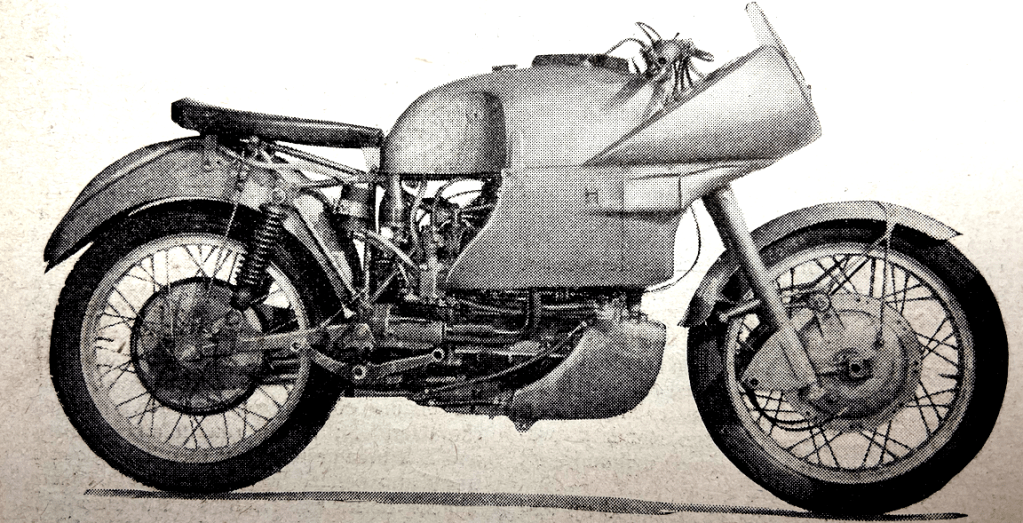

“ONE OF THE MOST stimulating designs of the present day is without doubt the Italian 125cc twin-cylinder two-stroke Rumi. I have just had an enthusiastic letter from Thierry Holst, the well-known Dutch journalist, who has had a peep inside a Rumi engine and an opportunity of trying one of the sports models. One of the things I did not know is that the pistons have deflectors which are V-shape in plan. The cylinder heads have female equivalents of the deflectors, so that good gas turbulence ‘up top’ results. Indeed, according to Thierry, the deflectors have proved so efficient that a reduction in ignition advance has been possible. Before adoption of the deflectors, the ignition advance at 6,500rpm required to be in the region of 29°; with the deflectors, only 22° advance is necessary at 8,200rpm. The compression ratio of the sports model engine is 11½ to 1 (!) for use with normal ‘super’ (78-octane) fuel. The crankshaft is of the three-bearing type, with one bearing in the middle between the big-ends. The circular internal flywheel is highly polished. Holst’s letter goes on, ‘I don’t know if you have ridden a Rumi, but if not, let me tell you it’s a marvel. I rode the sports bus (not the racer), which behaves like a good ohv 350 and has a maximum of over 70mph (not kph—miles!). The suspension proved amazingly good. Braking is positive, progressive and safe. The riding position is like that of a comfortable 500. Acceleration is completely breathtaking. In spite of the high performance, fuel consumption tops 112mpg at 40mph.’ Thierry’s letter runs to nine pages. He does not stint himself in the use of superlatives, and he eulogises the Rumi as I have never known him praise a motor cycle before. Other snippets of interest from the letter are that Rumis have a 125cc ohc four-stroke for attacking Mondial road-racing supremacy. The 250cc ohc parallel-twin racer, which has the camshaft driven by gears between the cylinders, is undergoing tests at Monza. The 125cc racer, says Thierry, has not yet run. For a firm that is also engaged in the manufacture of textile machinery, and which made torpedoes during the war, Rumis have certainly made vast strides in the motor cycle world. He who first condemned the Latins as a lazy people certainly overlooked the Italian-motor cycle manufacturers!”—Nitor

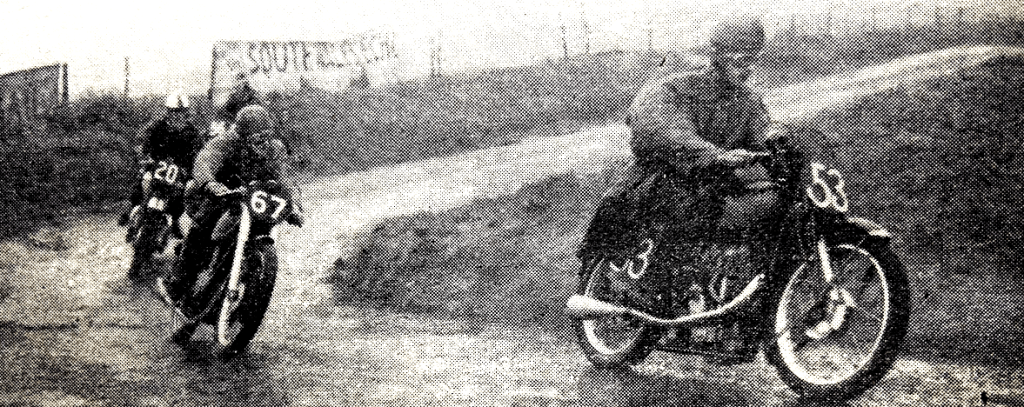

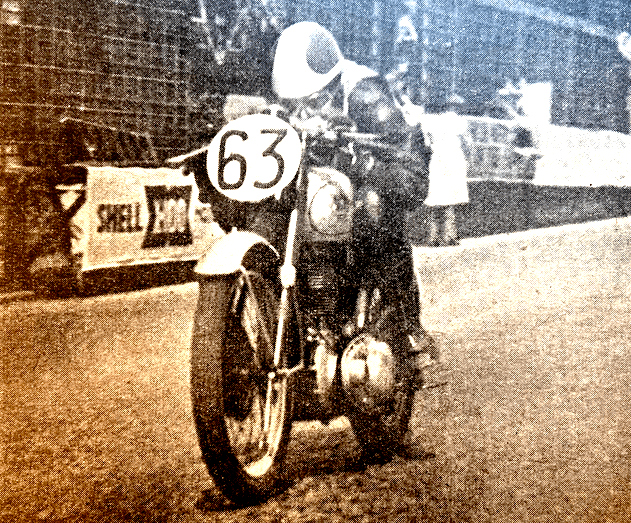

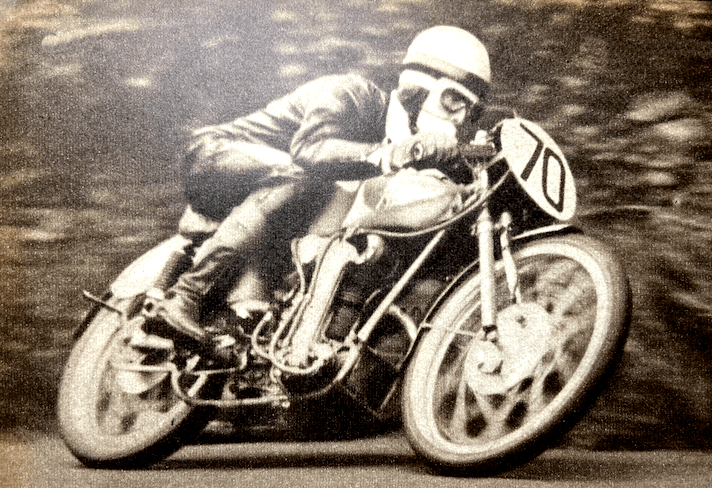

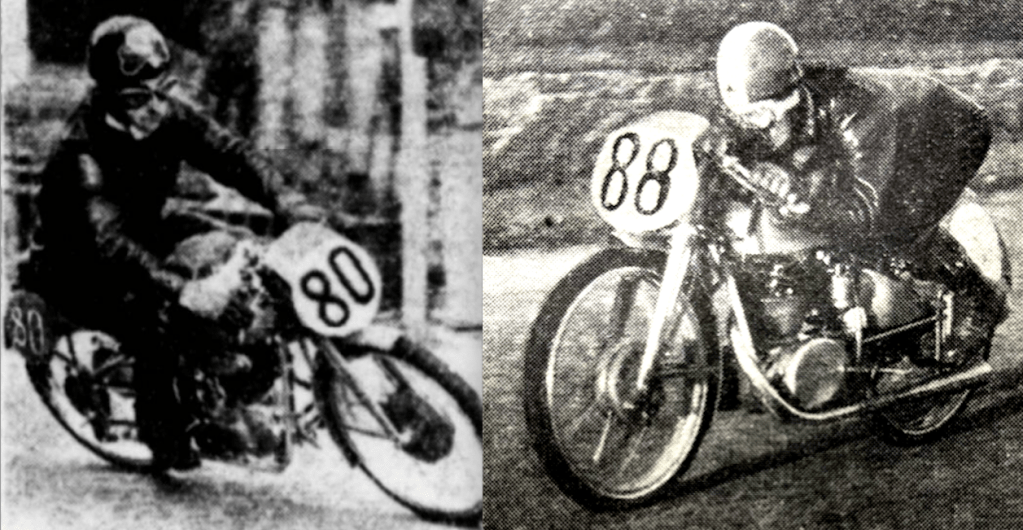

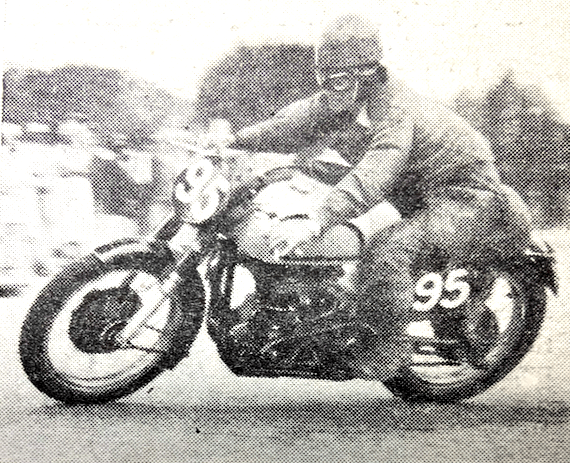

“UNDER OVERCAST SKIES and in heavy rain, thousands of enthusiasts from all parts of South Wales set out for Eppynt last Saturday in the hope that by the time they arrived at the five-mile circuit on the wind-swept Breconshire ranges the weather would relent. But, alas for their hopes! While the rain did ease off to become intermittent during the racing (organised by the Builth Wells and Carmarthen MCs), conditions, at times, were very unpleasant indeed. The spectators, greatly reduced in numbers, huddled at various points of vantage along the course to watch the riders struggle against the vagaries of nature. It was left to these riders to bring some colour into the drabness of the bleak May day. And, indeed, they did so. While no records were broken in the Senior, Junior or Lightweight events, speeds were high and, in one instance, went near to eclipsing last year’s lap record. This was in the Senior race, when ST Barnett (499 Norton) registered the fastest lap at 70.01mph as a challenge to RH Dale’s 1951 figure of 71.12mph.”

“A WEEK OR SO AGO a man proudly showed me his machine that had been treated with some sort of clear varnish to protect the paintwork and chromium. The goo is alleged to keep the finish free from rust and general deterioration. I understand that this preparation does work very well, but I had to have a quiet grin at the thought of covering a very handsome model with a chemist’s brew to keep it handsome. When chromium plate was first introduced I remember the fuss that was made about it. No more cleaning, no more rust, no more tarnished nickel. Now some folks cheerfully buy a preparation that protects the protection! The logical outcome of all this is for some-one to market a compound to protect the stuff that protects the finish. In case you think this is taking things a little too far, I understand that in the USA there are bumpers available that protect the original bumpers from severe

damage!—Nitor

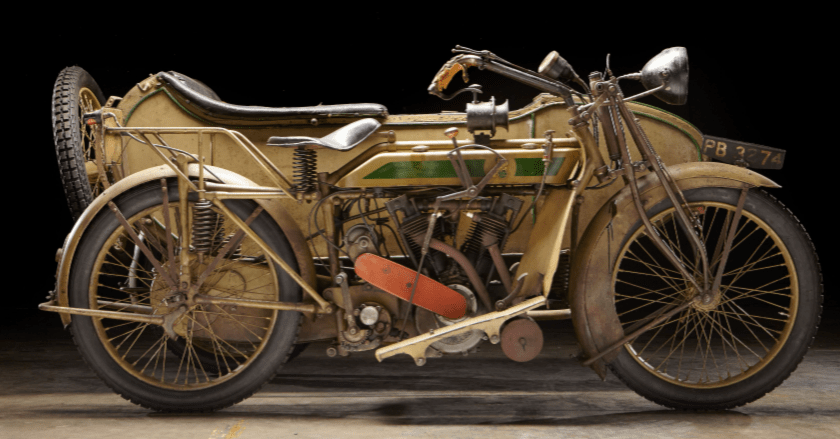

“A SEARCH FOR pre-1914 machines is being conducted by the Belfast Club, which hopes to promote a grass meeting for veteran motor cycles at the Balmoral show grounds, Belfast.”

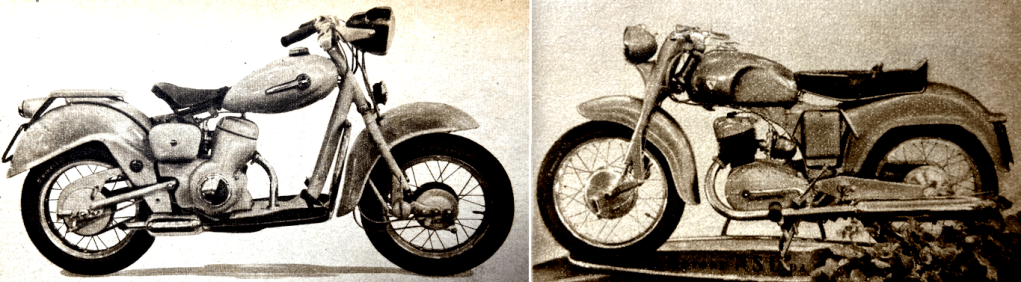

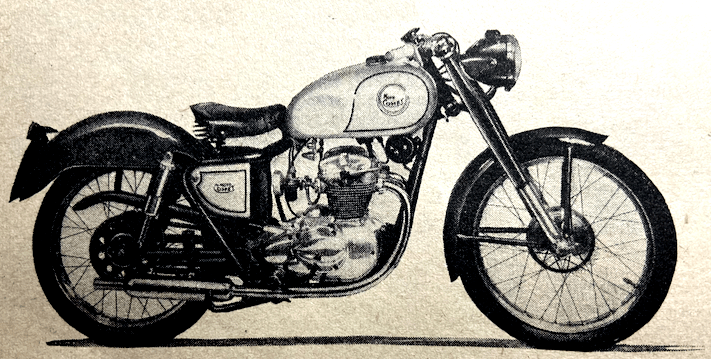

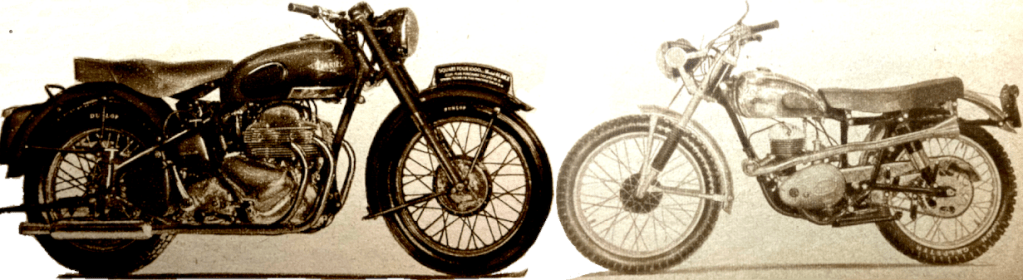

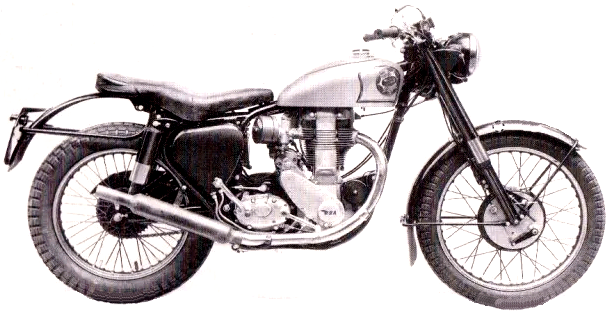

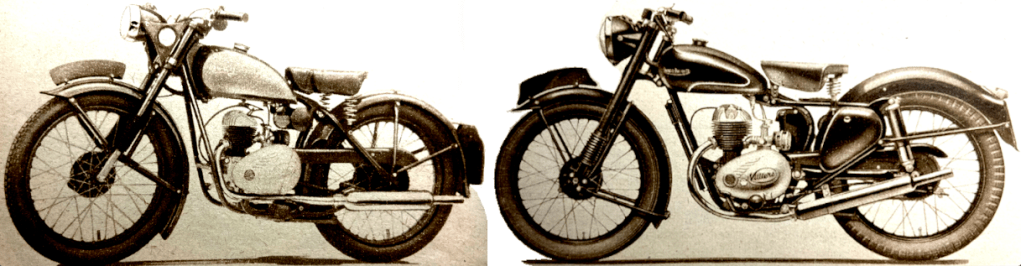

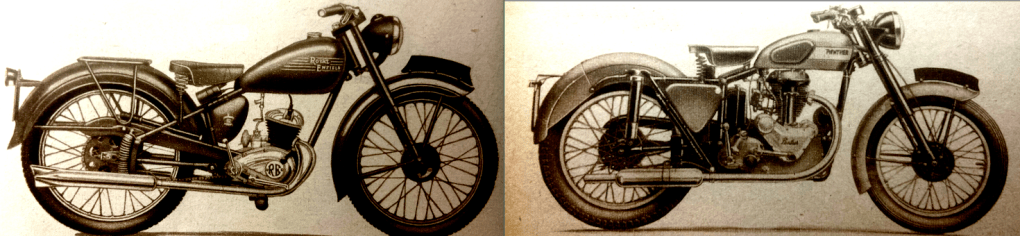

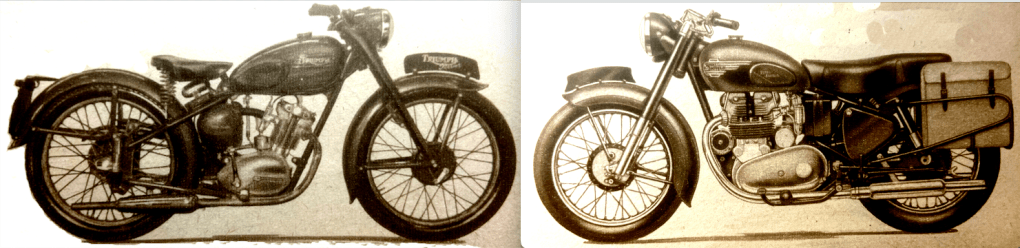

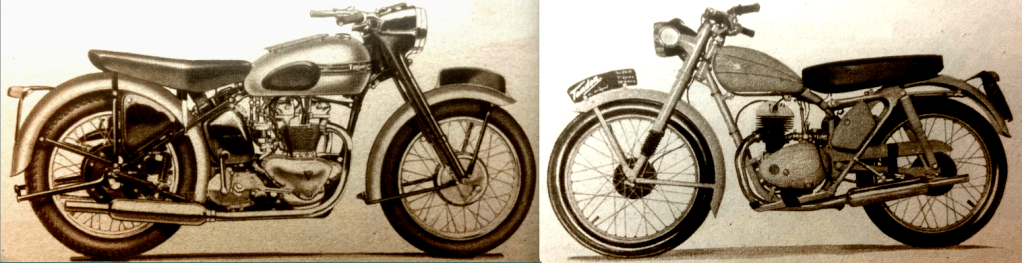

“‘IF I WERE to start making motor cycles off my own, bat, I would concentrate solely on 250s.’ The speaker was the sales manager of one of our biggest motor cycle manufacturing firms. The reasons he advanced were that with modern production methods and knowledge—assuming he were starting from scratch and his designer had a clean sheet of paper on his drawing board—it would be possible to make a 250cc machine with real performance on an economical basis. It is an axiom in the design field that the less the weight of material required, the lower the costs. A cleverly designed 250 would, in his opinion, be as inexpensive as, say, the average modern machine of under 200cc. Bearing in mind the performances of the pre-war Triumph and Ariel 250s, and the Rudges, his machine could have a cruising speed in the region of 55-60mph and a maximum of 70mph. It would be light and handleable, features which, in conjunction with the low cost, would give it a wider appeal, he believes, than any other capacity.”

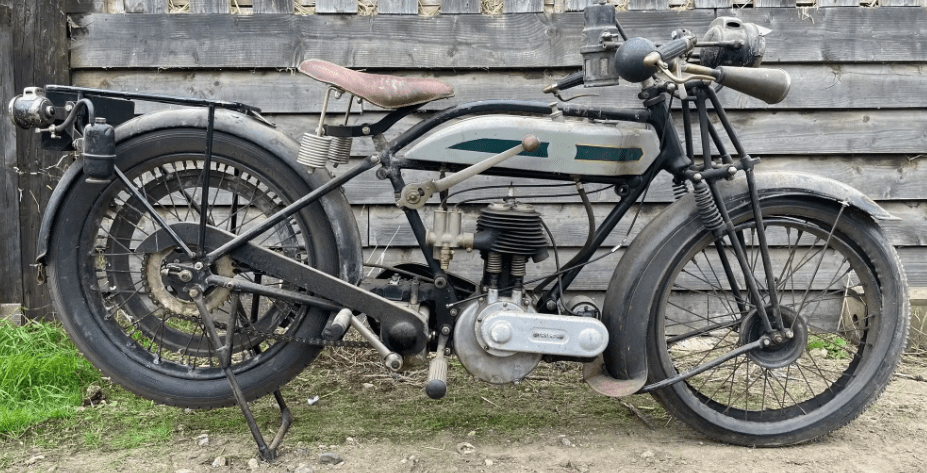

“YOUR VENERABLE SCRIBE Ixion was very interesting in his dissertation about the collectors of veteran motors, but I think that he has overlooked the main reason for this enthusiasm. It applies equally to veteran or vintage enthusiasts, and I feel sure that the all-embracing reason is—fun. The ability to have fun is sadly lacking in this spoon-fed era, and your died-in-the-wool enthusiast (not necessarily, by any means a young man) does like to have fun in his motoring. Professionalism kills the happy-go-lucky spirit, and this reversion to the oldsters does give one that feeling of adventure, no matter how small that adventure may be. For instance, the tackling of the ‘Land’s End’ on a 1952 export reject is very nice but oh so certain of a smooth passage. Indeed, one need not be a clever boy to finish the course. But tackle this run on a veteran or vintage machine, as so any did at Easter—then it becomes real fun and demands real driving. Possibly Ixion may be unaware of the number of veterans that are still on the road doing daily chores. I know of a Model P Triumph and sidecar, a belt-drive 1923 Cedos, and for some weeks I used a 1921 Triumph and sidecar (only 5,000 miles old) for a 10-mile daily business run! All this fun for a few shillings (the Triumph Model P cost 30s). So here’s good luck to them all. I know who has the best of the game—and it doesn’t cost £200-£300!

W DENNIS GRIFFIN, Manchester.”

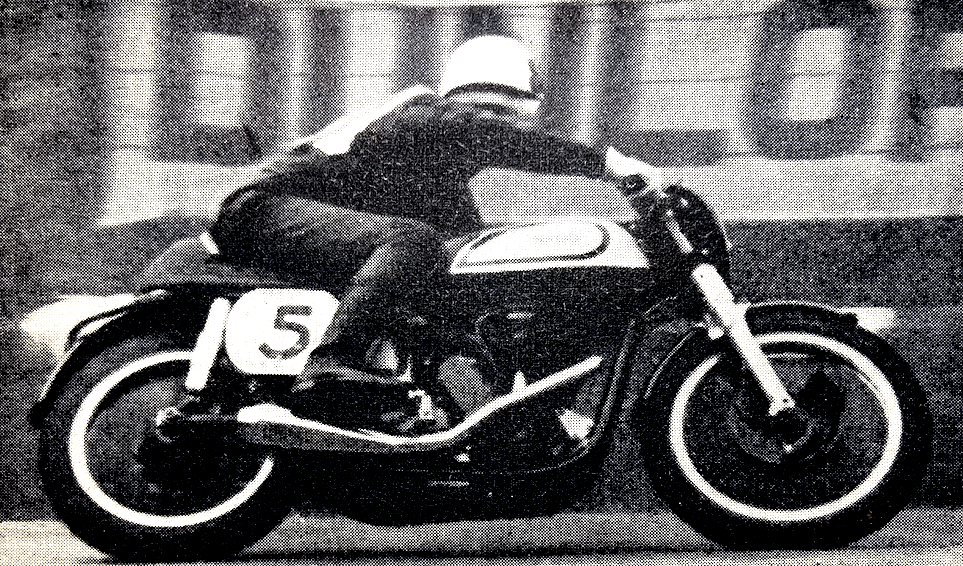

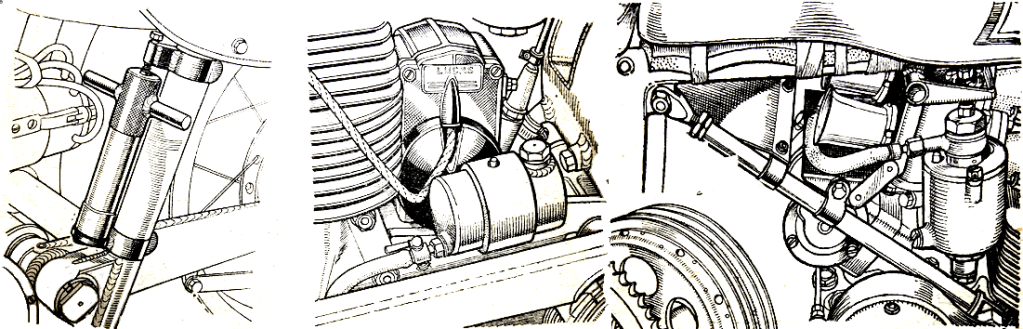

“EXPECTATIONS of new records on the ALJ Wicklow circuit by the Norton team, with the 1952 racing machines, were upset by the weather conditions, and the only record made during the day was by Reg Armstrong, who knocked three seconds off Johnny Lockett’s 1950 figure in the 350cc class with a lap at 83.40mph. The Nortons had the new rear hubs with the brake drums on the right (except Armstrong’s 350) and the modified rear suspension units. Geoff Duke was a non-starter; the explanation given was that he was unable to make the journey to Ireland. Armstrong, in his first appearance for Nortons, won both 350 and 500cc races and made fastest lap in each; Ken Kavanagh was runner-up in both races. When the field lined up for the 100-mile 350cc race, the roads were dry round the start, but a sea fog resulted in drizzle on the far side of the circuit. On the drop of the flag both Armstrong and Kavanagh made good starts, and at the end of the first lap they came through almost together, with the Australian slightly ahead; they had lapped at 79mph from a standing start. Twenty seconds behind were H Clark, C Gray and CG Griffiths (AJSs), With WAC McCandless (Norton) sixth. On Lap 2, Armstrong’s speed was 81.82mph and he led Kavanagh by seven seconds, while the lead over the rest was already 40sec. Gray had headed Clark; and McCandless, recovering from a slowish start, was in fifth place. On the third lap Armstrong surprisingly had a lead of 39sec over Kavanagh, who, it was learned later, had come off at the Beehive cross-roads, a sharp, deceptive turn at the end of the fastest stretch of the course. However, no damage was suffered and Kavanagh later worked up to an 80.72mph lap speed. At the beginning of the fifth lap McCandless came up into third place and closed on Kavanagh, who then speeded up and drew away again. On his seventh lap, Armstrong lapped at 82.71mph, equalling the record, and on his next he went round at 83.40mph, Then the rain started in earnest and speeds went down by nearly 10mph. Until then Armstrong had averaged over 81mph, but when he came in to win three minutes ahead of Kavanagh his average speed was down to 78.98mph. When McCandless finished third, all the rest were flagged off. Seven riders covered the full 12 laps, and another 11 qualified as finishers. The 500cc race (for which 350cc machines were eligible) started rather sensationally. Armstrong got away to another good start, chased by IK Arber (Norton), with Kavanagh some way back in the field. MP Roche, a young rider from Co Wexford, mounted on the ex-Ernie Lyons Triumph, came up from the second row and went into second place half-way round at Ballinabarney corner. A little beyond this point Kavanagh also passed Arber. Armstrong, covering his standing-start lap at 73.95mph, had a lead from Roche of 15sec, and Kavanagh was only one second behind the Triumph man. Going up the long hill out of Wicklow town he caught and passed Roche; but the young Irish rider held on gamely and made an attempt to regain his lead at Woolaghan’s Bridge, a tricky, fast S-bend, but did not manage it and came off, damaging his machine but not himself—in the Ernie Lyons tradition. Armstrong’s third lap was covered at 76.97mph, and this proved to be best of the race, though over 10mph below Artie Bell’s 1950 record, which gives an indication of the very bad conditions. He won by 1min 40sec from Kavanagh in spite of a stop for dry goggles. Arber rode very well in the wet, harrying Kavanagh for several laps, though he was reported as taking unusual lines on several corners. Kavanagh, however, opened up on his

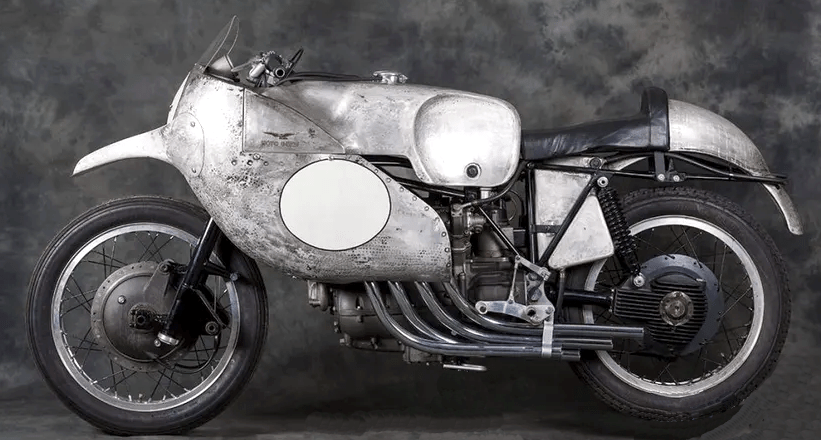

fifth lap and shook off the Kettering rider with a lap at 75.63mph, his best of the race. Arber’s best was at 74.31mph. The Carter brothers of Dublin occupied the next two places for most of the race, Louis, on a ‘Featherbed’, speeded up considerably towards the end and went ahead of his younger brother, Gerard, who was on an older Norton. Only these five covered the full distance, but 11 others, including 0 Sheridan on a 1927 Sunbeam, qualified as finishers. For the 250cc race there were only five starters: three Moto-Guzzis, a Velocette and an Excelsior. RA Mead, on the Velocette, led easily for two laps, making fastest lap at 65.13mph, then retired. W Billington ran out of brakes at Wicklow town corner on the first lap and retired; and TD Sloan, who had a two-camshaft head on his Excelsior, retired with plug trouble. This left AF Wheeler, on the Leon Martin Moto-Guzzi, with a comfortable lead from WJ. Maddrick, on the ex-Ben Drinkwater Moto-Guzzi. RESULTS 350cc Race (12 laps): 1, HR Armstrong (Norton), 78.98mph; 2, K Kavanagh (Norton); 3, WAC McCandless (Norton); fastest lap (record), R Armstrong (Norton), 83.40mph. Class Handicap (private owners): WAC McCandless (Norton). 500cc Race (12 laps): 1, HR Armstrong (Norton), 75.27mph; 2, K Kavanagh (Norton); 3, IK. Arber (Norton); fastest lap, R Armstrong (Norton), 76.97mph. Class Handicap (private owners): IK Arber (Norton). 250cc Race: 1 AF Wheeler (Moto-Guzzi), 60.73mph; 2, WJ Maddrick (Moto-Guzzi); fastest Lap, RA Mead (Velocette), 65.13mph. Hutchinson Trophy (best on handicap): 1, WAC McCandless; 2, R Armstrong; 3, WF Sparling. Skerries Cup (beat novice): WF Sparling. Club Team Prize: Dublin &DMCC No 1 (R Armstrong, L Carter, G Carter).”

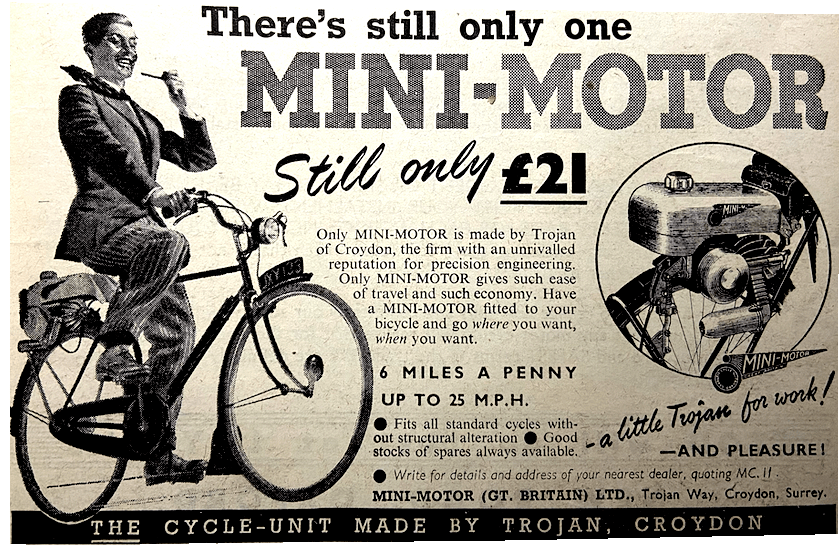

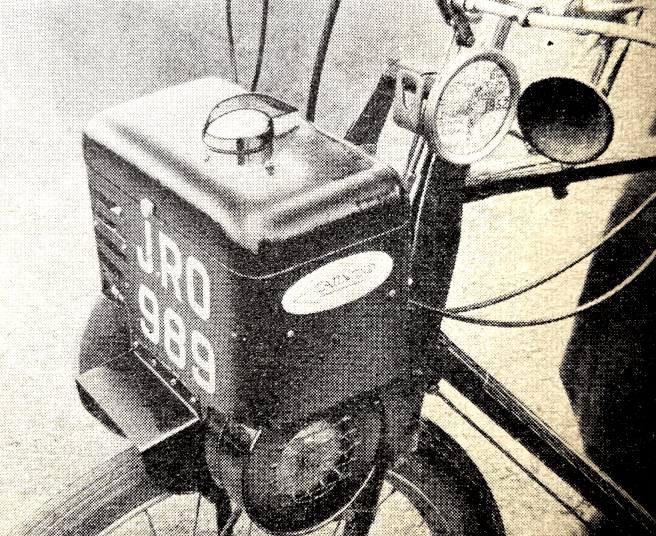

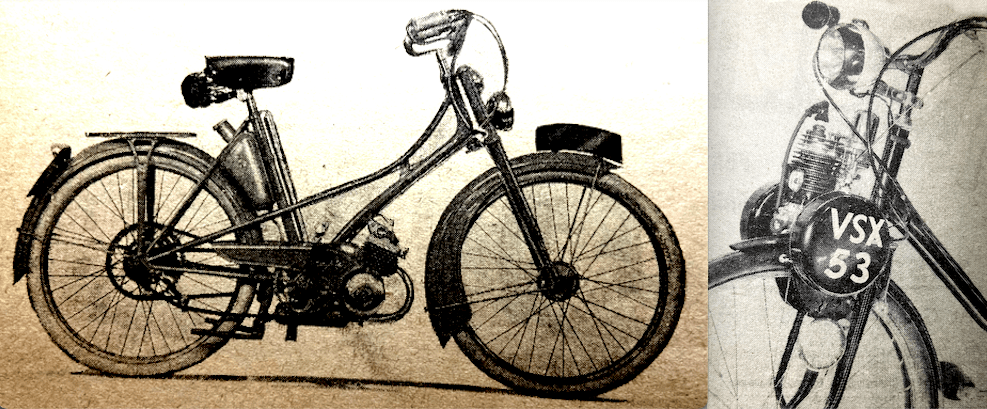

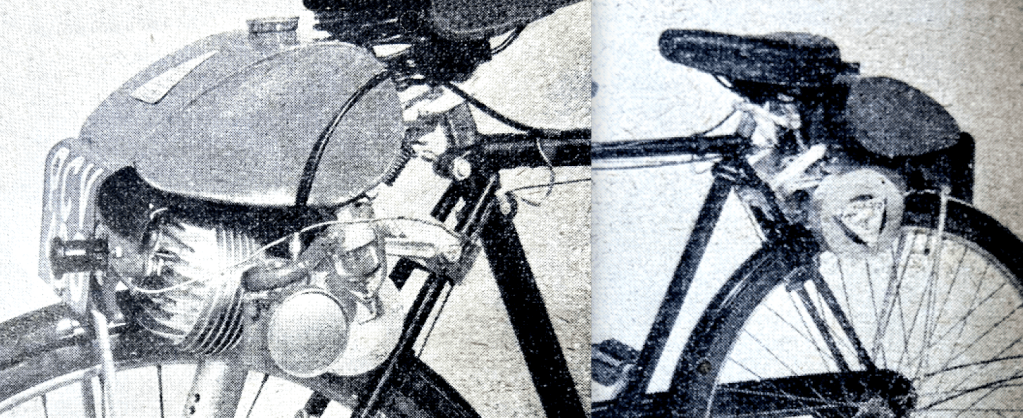

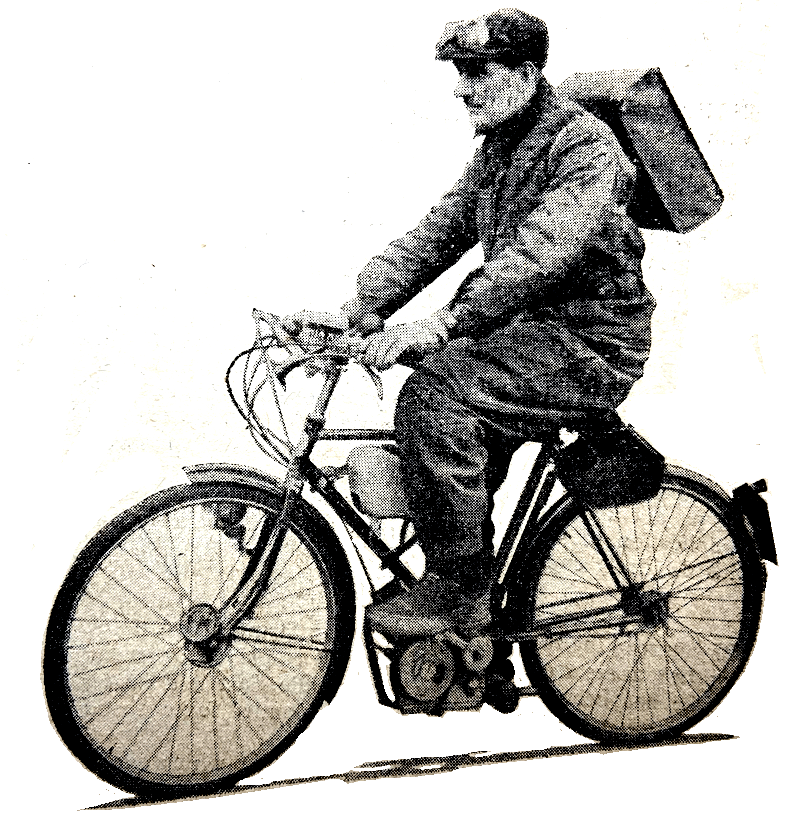

“SIXTY COMPETITORS ASSEMBLED in the car park at Wembley Stadium last Sunday for the Motor-assisted Cycle Demonstration Trial, the first of its kind in this country. Organised jointly by the British Two-stroke Club and the ACU, the trial was mainly of a ‘public interest’ nature. Certificates were awarded to successful competitors. The 14 makes of cyclemotor represented included two hitherto unknown in Britain—the Jet, a Danish engine of 50cc, and the Tailwind, a promising 49cc ‘two-speed’ design. The Jet is an inverted two-stroke engine mounted behind the saddle; it drives on to the tyre through a milled roller. The Dellorto carburettor is controlled by a twist-grip. Ignition is by Stensholm flywheel magneto. It is expected that these units will be available in Britain shortly. Still in the development stages, the Tailwind is a two-stroke enclosed in a box over the wheel. A two-diameter, carborundum-coated roller is employed to give a two-speed effect as between the engine and front wheel. A twistgrip control moves the unit sideways to effect ‘gear changes’. The engine is fan cooled. The trial opened with a starting test. Each competitor had 10 yards in which to pedal the engine into life, followed immediately by 10 yards which had to be covered without pedalling. Detailed route cards

were issued. The course covered 18½ miles of road with traffic lights, roundabouts, a hill, and similar ‘hazards’, and included one ‘rough’ section—a ¼-mile of unmetalled road abounding in potholes, ruts and puddles. The route had to be covered at an average speed of 12mph. At the half-way mark was a hill employed for a climbing test; it was marked out with six lines lettered A to F. Line A was a warning to stop pedalling. After three yards, B indicated that feet must be stationary by this point, and lines C, D, E and F were at five-yard intervals up the hill. Pedal assistance was permitted after line E, but a stop anywhere in the observed section resulted in loss of marks heavy enough to preclude an award. The lower down the hill the rider had to pedal, the heavier was the penalty. In view of the difference in load in relation to the total weight of machine and rider imposed upon the tiny engines by, say, a seven-stone rider and a 12-stone rider, this policy seemed a little severe. Two further tests followed the check-in at the Stadium at the finish. Professor AM Low operated an audiometer to record the degree of silencing, and the readings of the instrument were interpreted in three grades: quiet, reasonable and noticeable. The three Tailwind entries all qualified for the first heading, and Berinis also maintained a high standard in this test. Rain, which fell heavily in the later stages of the trial, produced interesting results in the second test, which was of brakes. The cycle-type rim. brakes let many competitors down, whereas those

machines equipped with internally expanding hub brakes, or with coaster hubs, achieved much better results, One Cyclemotor rider had fitted a 4in front brake—just to be sure! Early arrival at the finish entailed disqualification, but each rider was allowed three minutes after his expected time of arrival. There were two retirements, one through mechanical trouble. The pint of petroil issued to each machine at the start brought all home, though some competitors admitted that the fuel level was on the low side at the end. First-class certificates were awarded for retention of 90 out of 100 marks, and second-class certificates for an 80% performance. The trial appeared to be highly popular with the competitors, and one even suggested that similar events should be run weekly. RESULTS First-class Awards: FG Cosson (38cc Bantamoto), R Dendy (48cc Cucciolo), K Poole (48cc Cucciolo), AW Jones (48cc Cucciolo), CW Saville (31cc Cyclaid), T Gould (31cc Cyclaid), R Miles (25cc Cyclemaster), J Macielinski (48cc Miller), T Smith (48cc Miller), K Mercer (49cc Mini-Motor), A Pointer (49cc Mini-Motor), F Allen (38cc Mosquito), D Shallcross (49cc Power Pak), H Easton (49cc Power Pak), J Latta (49cc Tailwind). Second-Class Awards: P Longsmore (38cc Bantamoto), J Cooke (32 Berini), I Caswell (32 Berini), F Rasch (32 Berini), P Hodge (32 Berini), T Geyther (31cc Cyclaid), K Whiting (25cc Cycle-master), J Meyrick (25cc Cyclemaster),B Bollen (25cc Cyclemaster), G Ryan (25cc Cyclemaster), D Brown (25cc Cyclemaster), G Denton (49cc Mini-Motor), RK Sergent (38cc Mosquito), W Manley (49cc Power Pak), 0 Udall (49cc Power Pak). A Gatto (49cc Power Pak), A Smith (49cc Tailwind).”

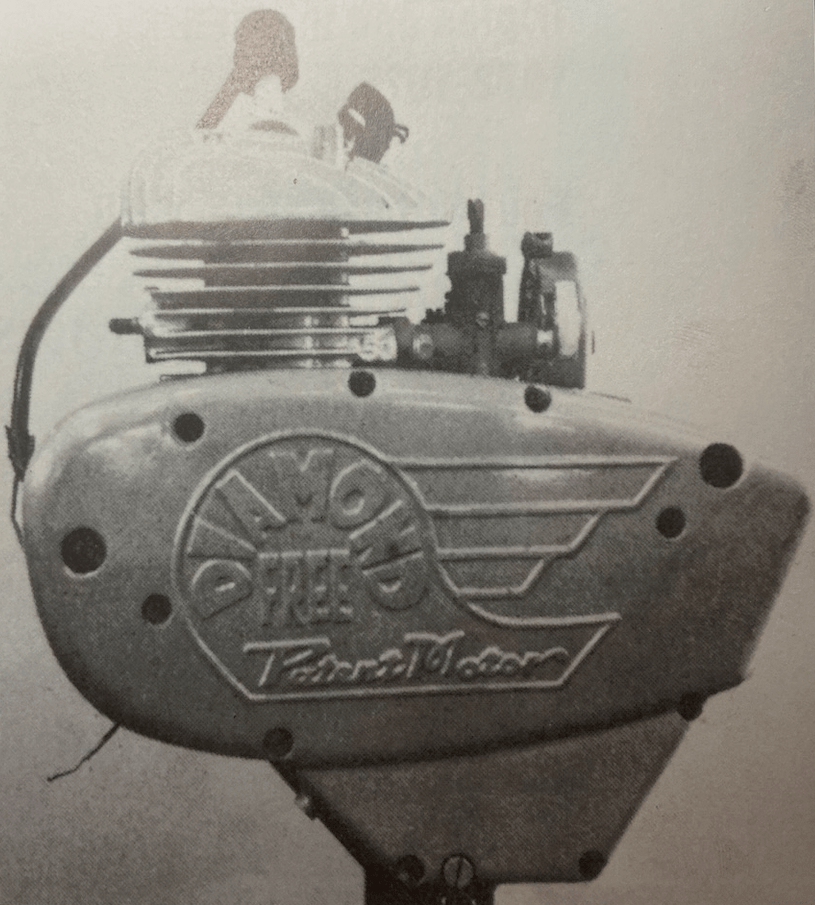

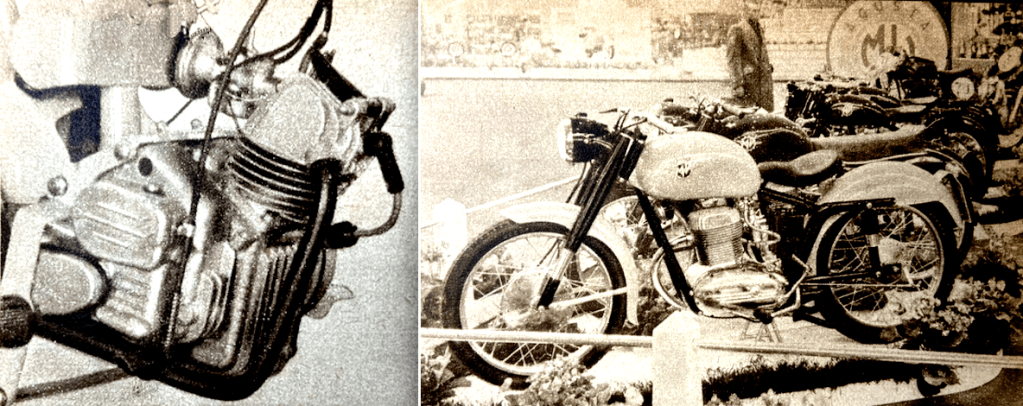

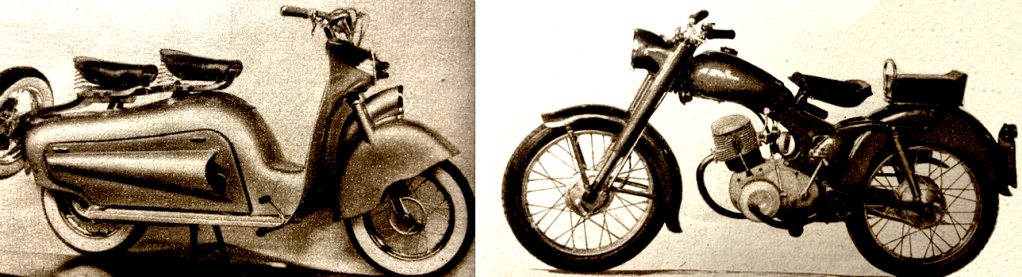

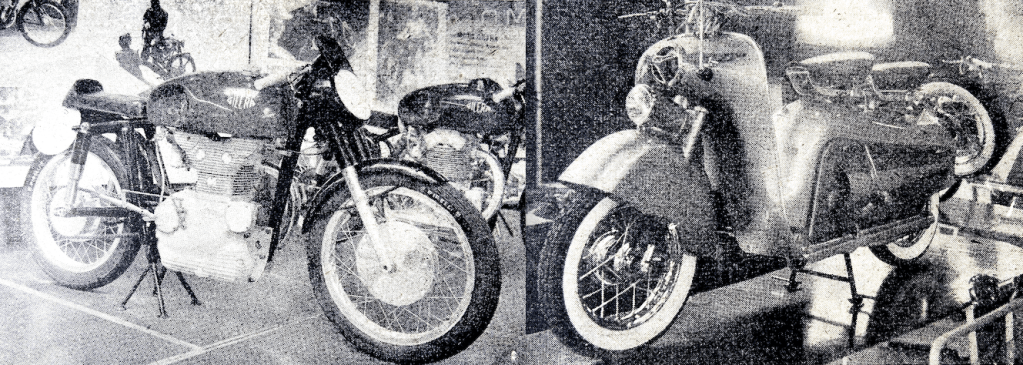

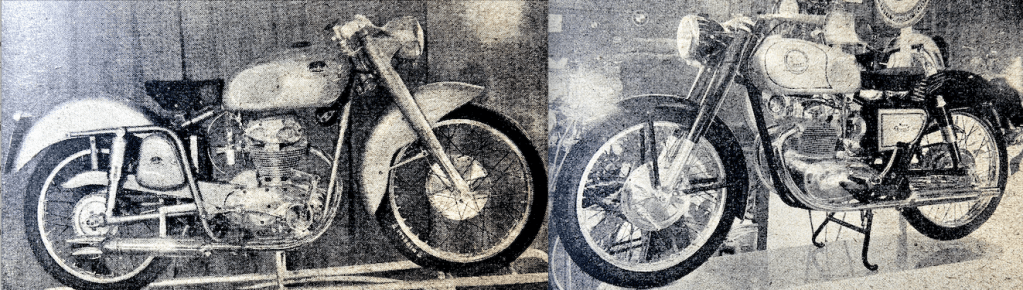

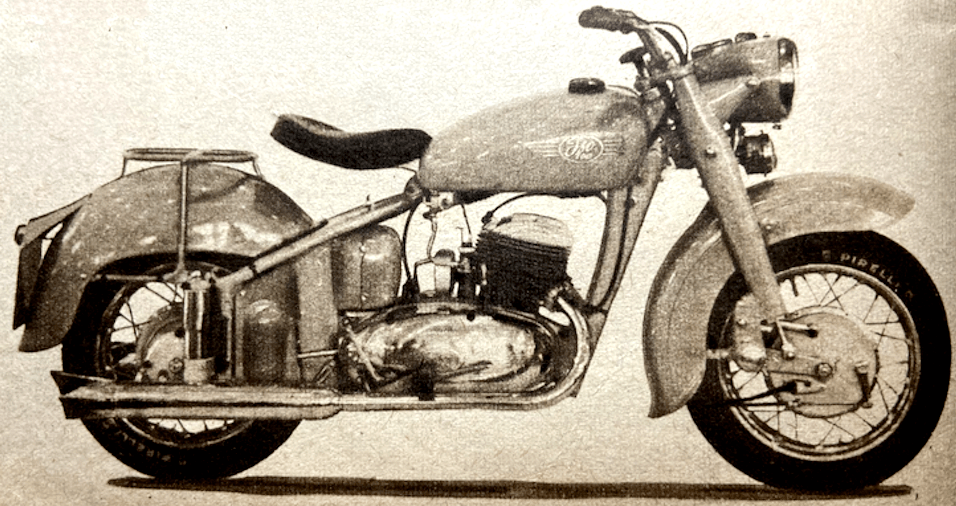

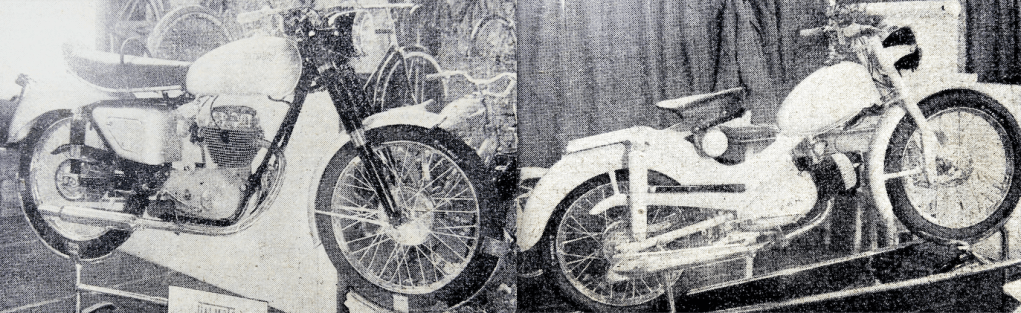

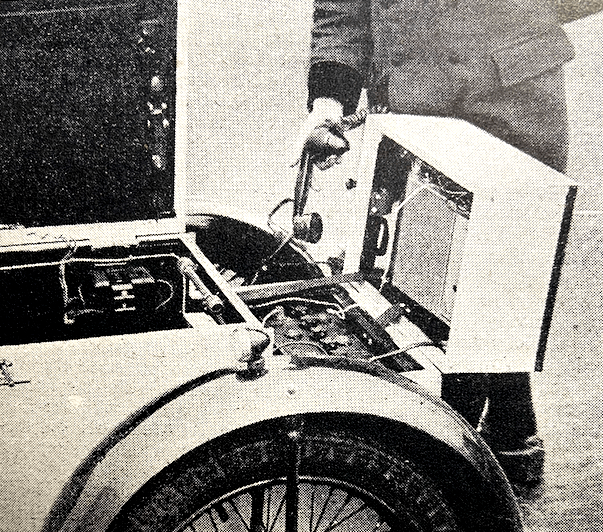

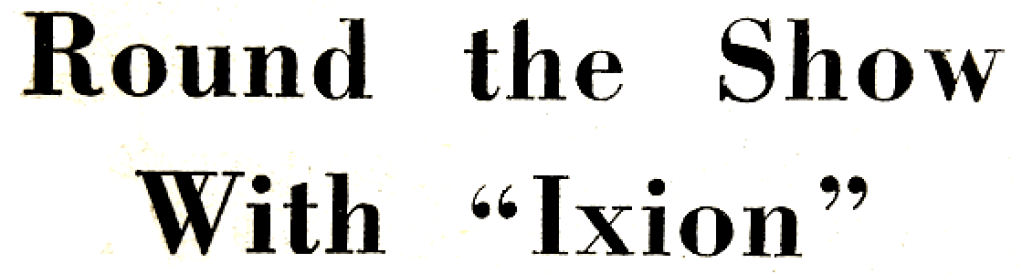

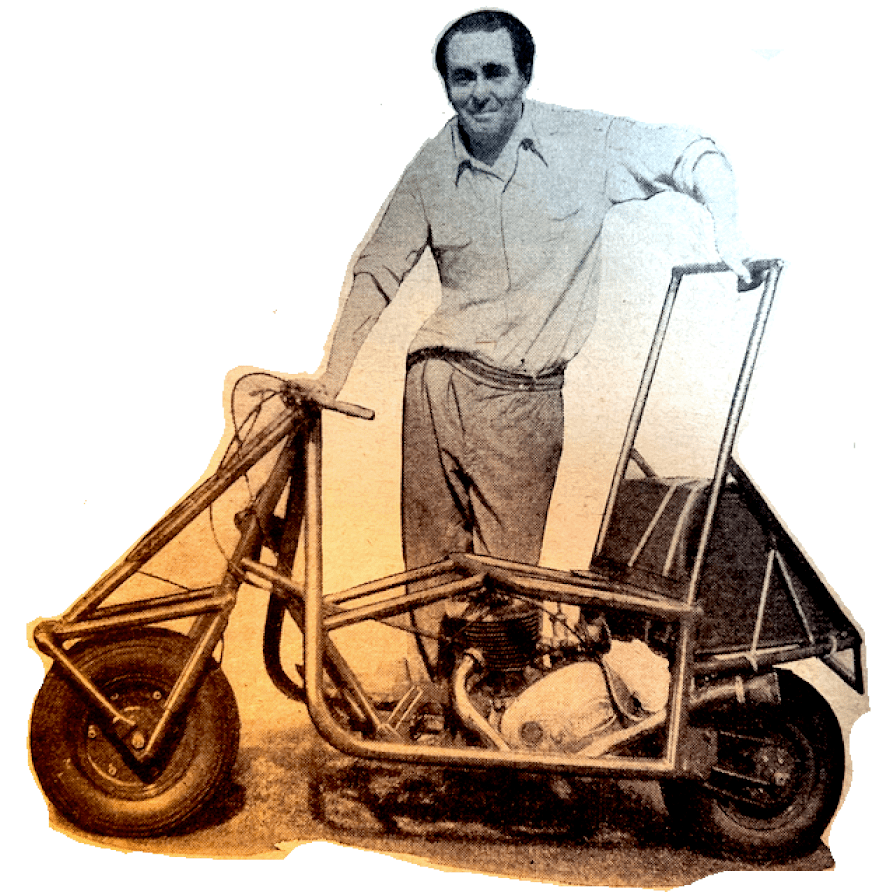

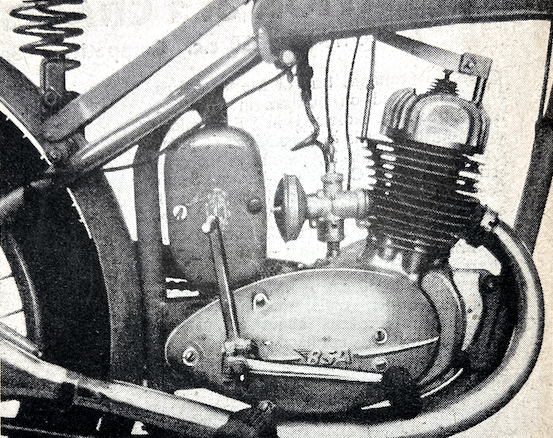

“THERE IS MUCH to interest the motor cyclist at the Birmingham section of the British Industries Fair, which opened at Castle Bromwich on Monday. A surprising number of engines which are familiar as motor cycle power units can be seen adapted to all manner of useful industrial purposes. Royal Enfield two-stroke power units of 98 and 125cc, for instance, are shown ready for application to such implements as chain saws, cultivators, winches, lawn mowers and compressors. The famous 122 and 197cc Villiers two-stroke is available for driving—among other things—water pumps, circular saws, mechanical scythes and milking machines. A 395cc Villiers two-stroke has a special reduction gear to make it suitable to power agricultural elevators and concrete mixers. All these engines are air cooled. BSA 320 and 420cc side-valve industrial engines are seen ready for installation in trucks and winches. A novel and economical method of shunting railway trucks and rolling stock is demonstrated by the BSA truck mover. This is a single-track machine running on a rail and powered by the 420cc engine. The operator walks alongside, controlling the machine from an extended handlebar. A load-moving capacity of 75 tons is claimed for the unit. An interesting two-stroke engine manufactured by Aspin—a name associated with rotary valve four-strokes—is employed for the Sankey Saw. Castings are in magnesium-electron alloy and the cylinder is fitted with an alloy-iron liner. Petrol tank and carburettor as an assembly can be rotated round the inlet stub so that the engine will operate at any angle as demanded by the cutting to be done. Purely motor cycle exhibits are the 250cc side-valve Indian Brave and the Corgi on the Brockhouse stand. On the Lucas stand is the RM12 motor cycle generator which, it will be recalled, is intended to be mounted on the engine shaft. Also on the Lucas stand is an exceptionally fine model of a main road running through a town illustrating the advantages of the double-dip headlamp system for cars.”

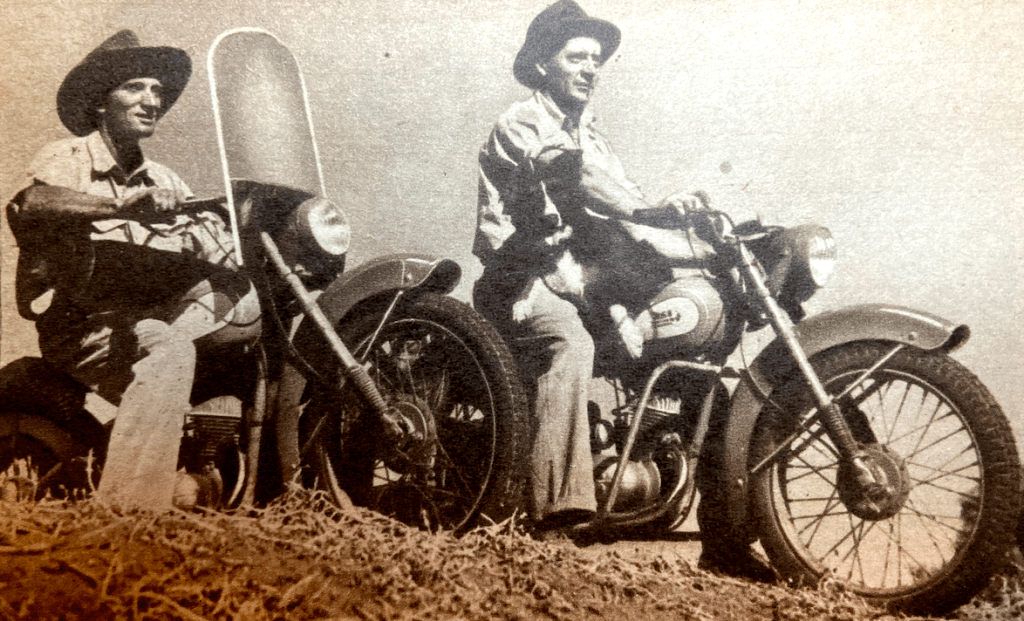

“FOR A HUNDRED YEARS the Australian jackeroo (boundary rider)—that great legend of the outbacks—has relied on horses to do his work. Today it is no longer fashionable, or economical, for that matter, to use a horse, and for boundary riding and sheep droving he uses a motor cycle. This was revealed recently by AE Smith, of Menincourt Station, Pooncaris, New South Wales, in an essay competition which won him a BSA Bantam. He said that the Australian station owner now found that a motor cycle, especially a spring-frame model, will go anywhere and, more quickly and cheaply, do work which previously could only be done by the horse. The 125cc two-stroke, because of its lightness and dependability, is considered ideal for this work. Mr Smith said he uses eight BSA Bantams which have almost replaced horses on his station (ranch). Several stations in the surrounding district also have two-stroke motor cycles doing daily work—for transporting stockmen on long trips across the property, for journeys into town centres for provisions, and generally for all the work formerly executed on horseback. The machines travel up to 20 miles, over all types of country, in under the hour. ‘The horse would take a whole day to complete the same journey,’ said Mr Smith. For rounding up stock a box is generally fitted to the carrier, and a sheepdog, the famous Australian ‘kelpie’ (said to be a cross between a collie and the native ‘dingo’—wild dog), rides pillion. The beauty is that the dog arrives at the destination fresh to start on its energetic work of rounding up the stock. At first, the dogs were a bit shy of motor cycles, but one ride was sufficient to convince them. ‘You only have to walk up to a machine and the dog will leap into the box ready to be taken for a ride,’ said Mr. Smith.”

“HERE IS ANOTHER angle on motor cycling in the Australian hinterland—in the sporting sphere. In the USA they talk of riders ‘burning up the track’ in speed events, and at Yarrambat, Central Victoria, they succeeded in this—literally! At a high-speed scramble event held there by the local club, competition (and the weather—around the century mark) were so hot that competitors actually set fire to the track! The combination of sudden rains and a hot spell produced an over-growth of grass six feet in height. The excitement started in the sidecar handicap. L Evans was leading when he kicked his gear-change such a clump that the lever jammed and the exhaust pipe fell off. Unable to pull up (no gear box), he sailed straight into the long grass and in a second—it was on fire! Racing was forgotten for half-an-hour while everyone played at fire-fighters. Members of the club (Diamond Valley) were also volunteers of the local fire brigade. They dashed back to the village, grabbed the equipment, and returned to make short work of the blaze.”

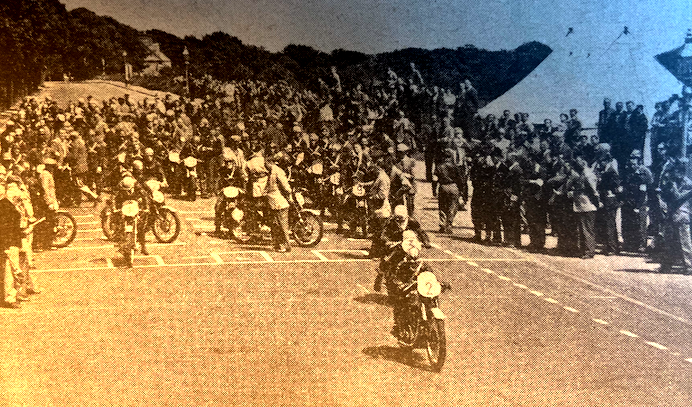

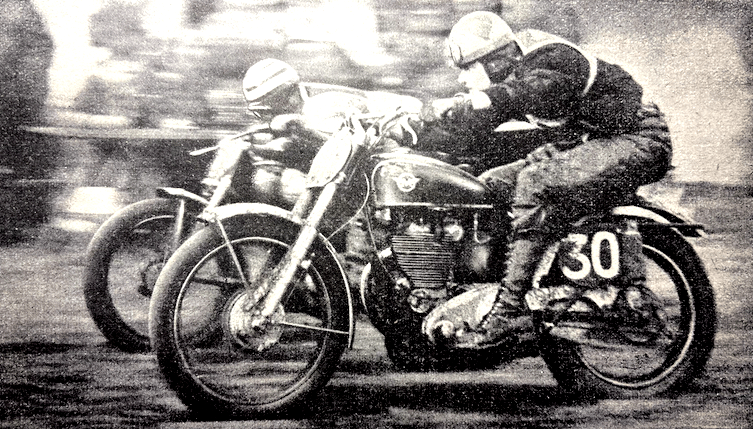

“ORGANISED by the Wirral Hundred MCC and held on Wallasey Sands, the Daily Dispatch Gold Cup meeting always attracts a large entry. At last week-end’s meeting, 73 competitors came under starter’s orders. The races were run in class heats, the first four riders in each class going forward to the big race of the day which was held over 30 laps. The 500cc machines conceded two laps to the 250s and one to the 350s. The event was won in brilliant fashion by RB Young, the Norton factory rider. Starting from scratch, Young disposed of the 350 and 250cc competitors on the 17th lap and continued to draw ahead. By the end of the race he was over a lap ahead of the second man, S Wilson (498 AJS); third position was held by FC Pusey (348 Norton). Because of shifting sands, the course was not in its usual good condition. Both corners were cutting up badly and riders had to cross four gullies in the course of a lap. Viewing the circuit during practice Young very wisely decided to ride his new spring-frame Norton scrambler, and there is no doubt that this choice contributed materially to his victory. Where Manx Nortons and Triumph Tiger 100s were getting bogged down on the corners, Young sailed through as though on a main road. The 15-lap Silver Trophy race for side-car machines brought a resounding victory for F Taylor (498 Norton sc), who won by over a lap from W Poulton (998 Ariel sc), and G Woodworth (499 BSA sc).”

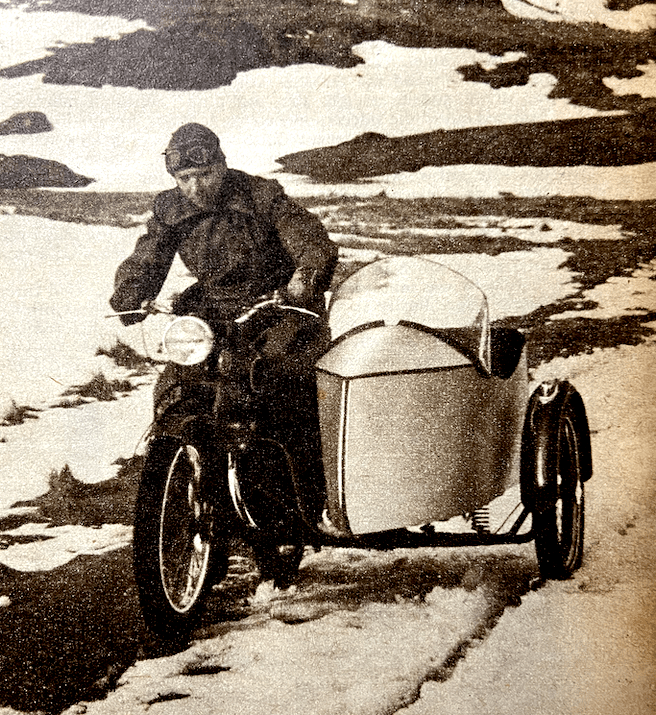

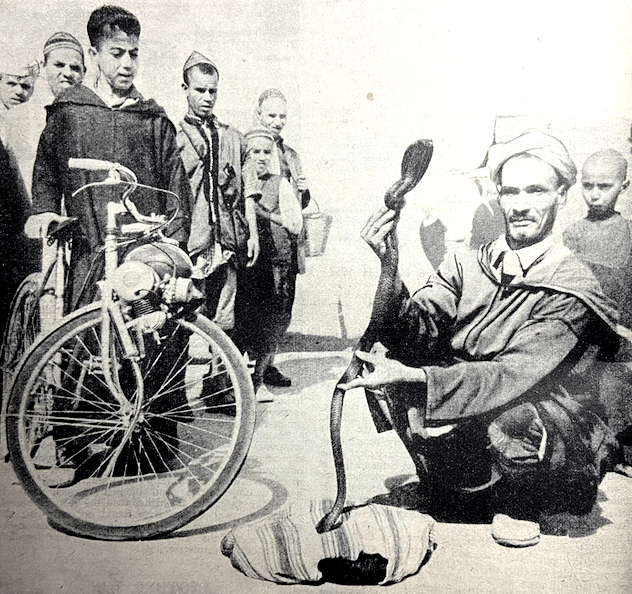

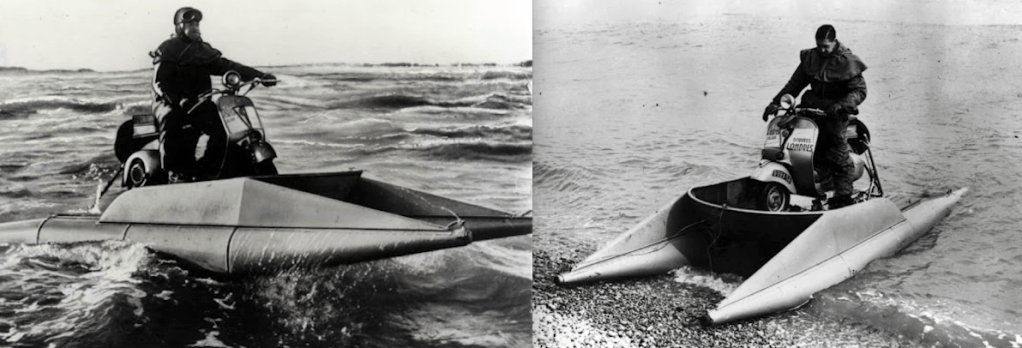

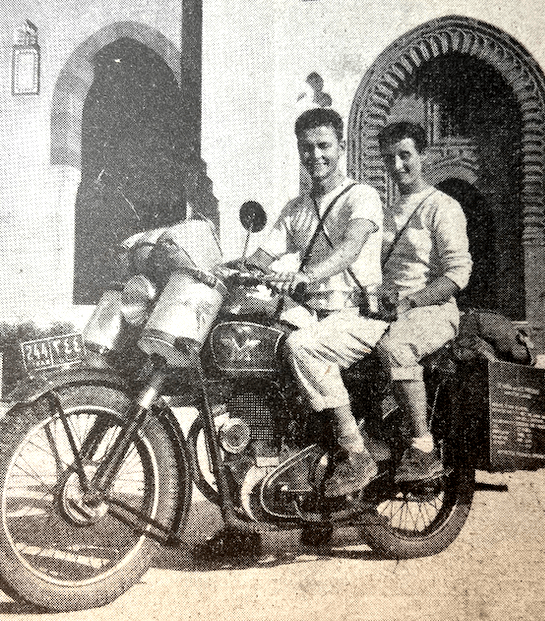

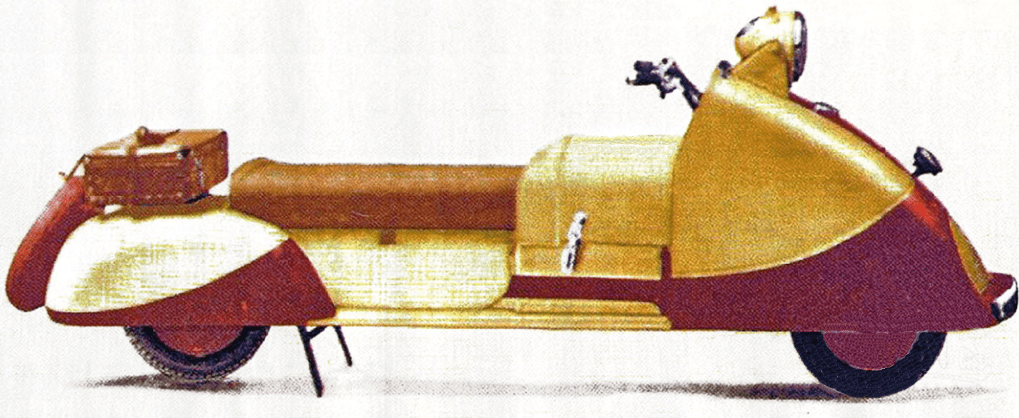

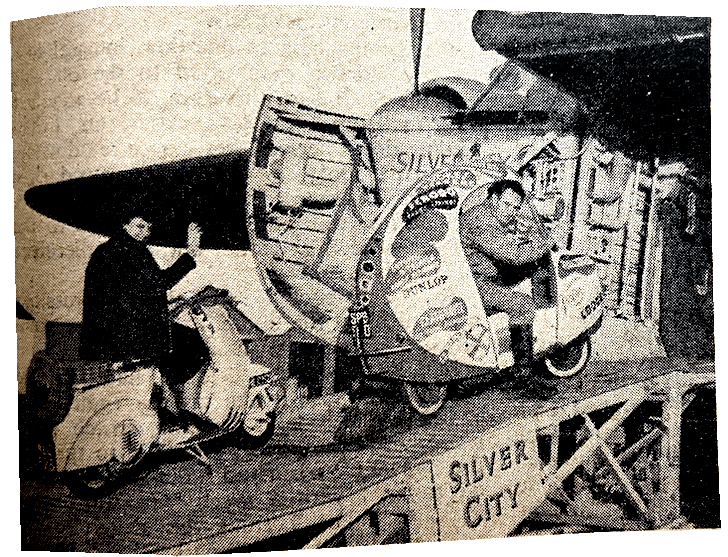

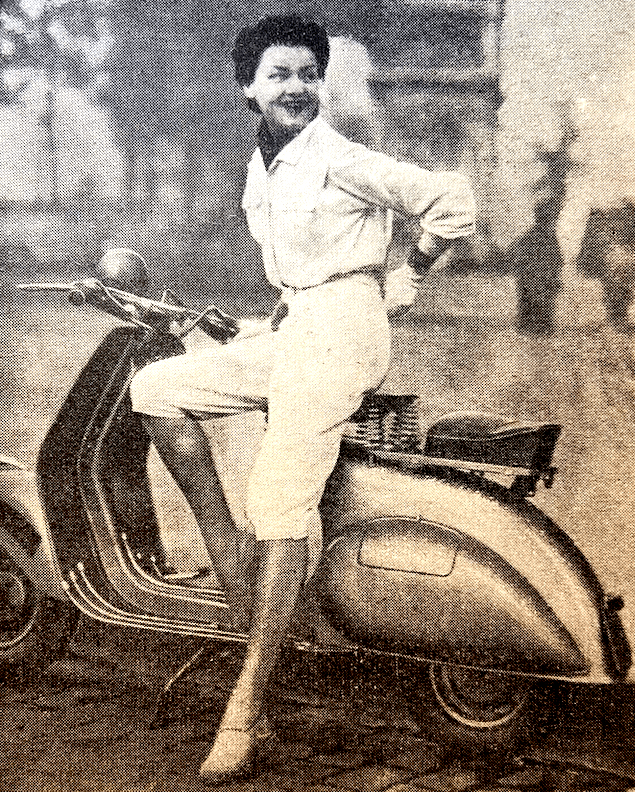

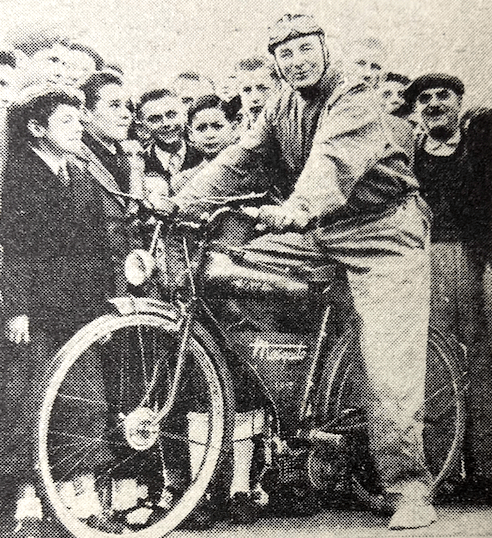

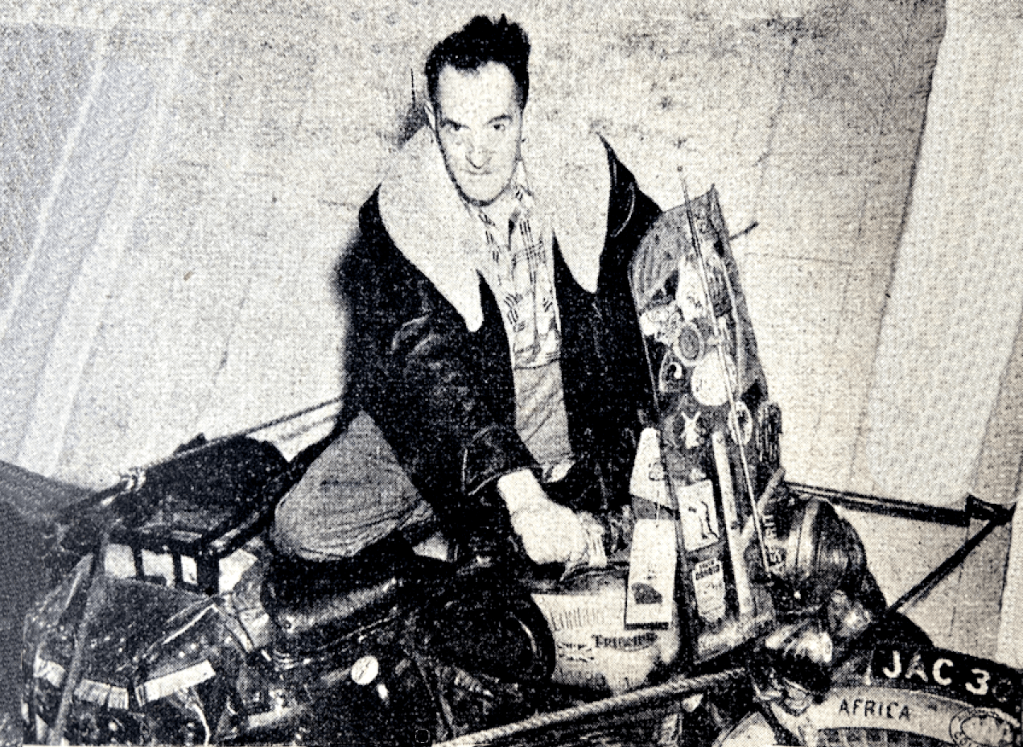

GEORGES MONNERET, NICKNAMED ‘Jojo la Moto’, rode across the Channel as part of a Paris to London race, installing his Vespa on a pedalo-catamaran whose propeller was driven via a roller from the rear wheel. The forced-air turbine continued to cool the engine despite the boat’s low speed. Escorted by a trawler from Boulogne, he reached port on his second attempt (it was damned rough out there) and won the race in a record-breaking 15 hours. In a 32-year racing career Jojo set 183 world records and won 499 races.

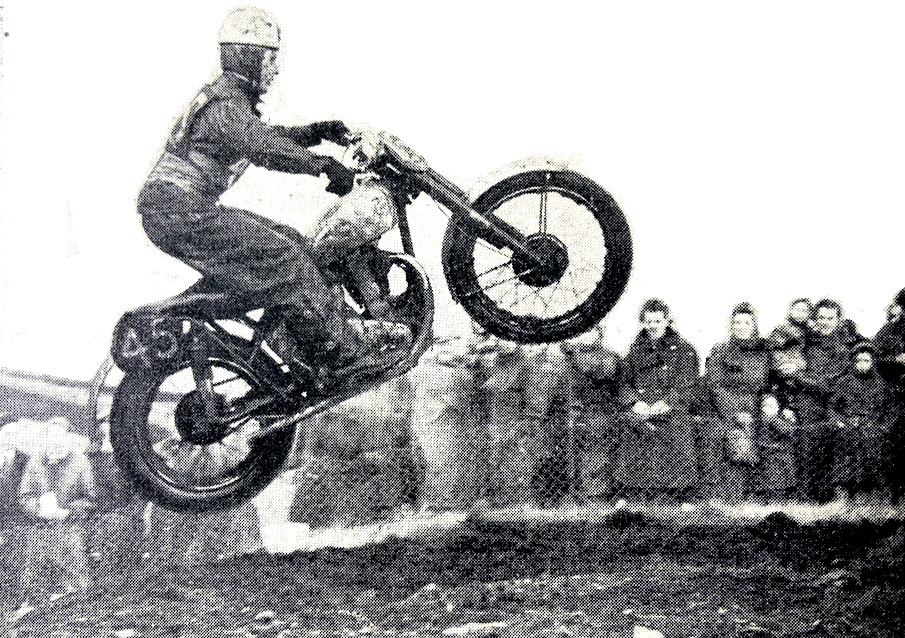

“tHE NORTHERN TEAM had little difficulty in winning the first leg of this year’s North vs South Scramble. When the team goes to Pirbright for the Southern leg it will have a 40-point lead. The South, without the services of some of their star men, and suffering a last minute set-back in the non-appearance of Geoff Ward, never recovered from a 32-point deficit in the first heat. The event was organised by the Ribble Valley MC for the North-Western Centre at Parsonage Farm, near Blackburn, in Lancashire. The 1¾-mile course was very dry and bumpy. Mainly fast, grassy going was interspersed with a number of short, tricky hollows, and one steep ascent from a muddy hairpin. A variation on the usual mass start is being used in this year’s events. The teams are divided into ‘A’ and ‘B’ sections of six riders, each section meeting the other in turn. This gives four races and tends to even out bad luck which might ruin a team’s chances in a single event.”

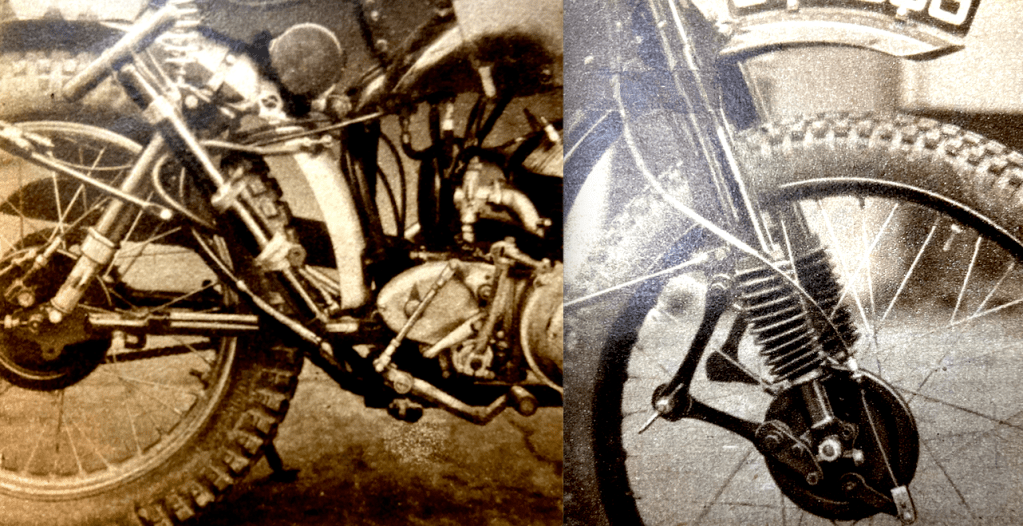

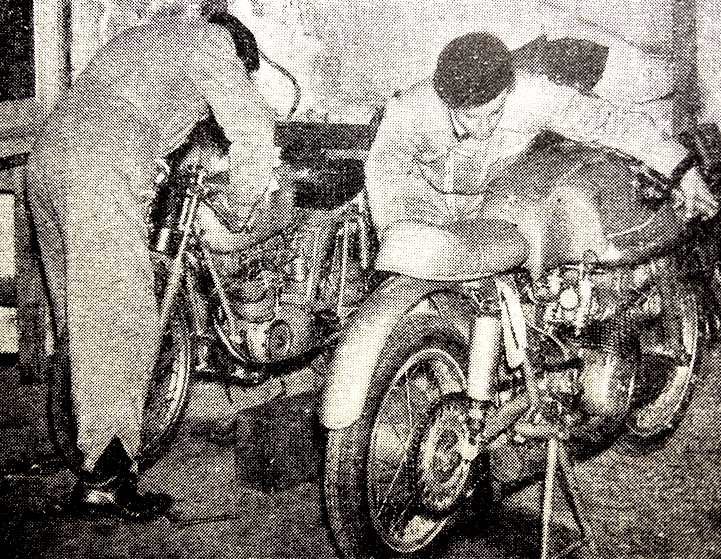

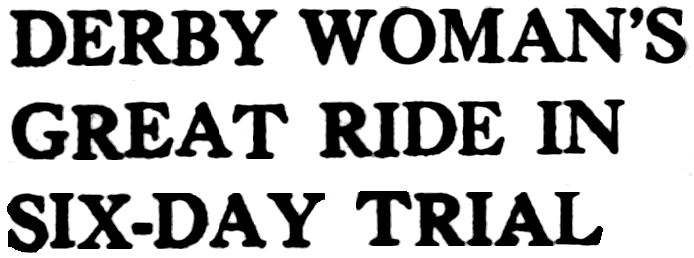

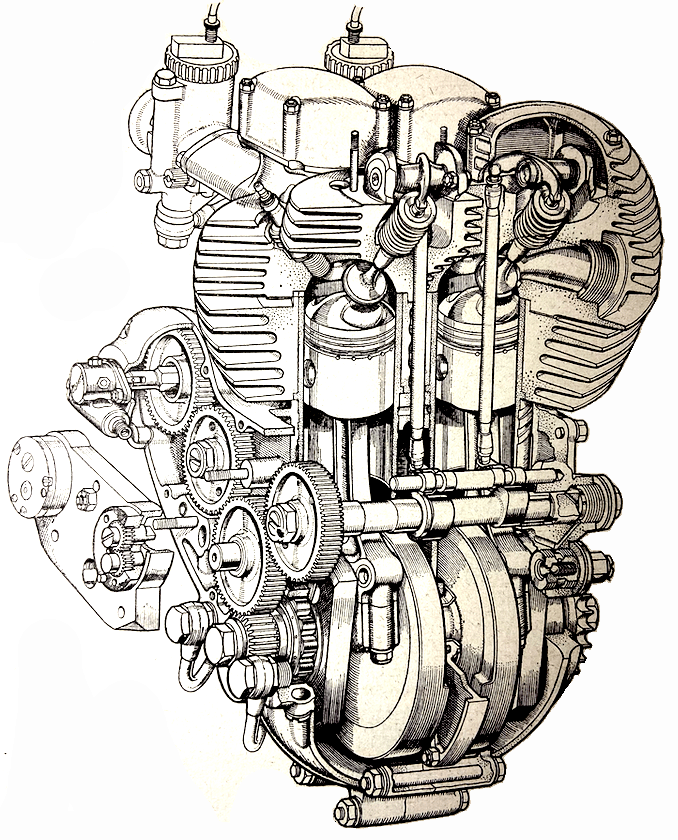

“THE TREND TOWARDS a reduction in the number of spares carried on Scottish Six Days Trial machines continues. This year, components held to machines by rubber bands usually comprise no more than spare inner tubes and footrests. Tools are mounted unobtrusively or carried in haversacks. The Christmas-tree look has disappeared. With so many manufacturers producing quality competition machines, the old order will probably never return. During the weigh-in at the official garage on Sunday, a crowd of enthusiasts and lay public alike collected to watch the proceedings. All were impressed. It is probably true to say that the general standard of machine preparation has never been higher for a ‘Scottish’. The machines gleamed and glistened as though they had come from a showroom. Especially impressive were the Royal Enfield ridden by WJ Stocker and the 347cc Matchless ridden by RW Peacock. As last year, the works’ DMWs are fitted with four-speed gear boxes and air-controlled front forks. One of the ‘unusual’ machines is FH Barnes’ Excelsior Talisman Twin with pivoted-fork rear springing. The fork is controlled for impact loading by coil springs, and by rubber for rebound. Barnes is, of course a regular competitor with sidecars. His usual, passenger, P Parsons, is also competing, riding a 348cc Norton. Another (usually) sidecar competitor riding a solo is FH Carey, who has a 125cc Royal Enfield. As for 1951, there is no sidecar class. The full solo entry of 180 represents a record for the event. The popularity and reputation of the trial may be judged from the fact that of the 180, no fewer than 93 are competing for the first time. Yet another surprising feature of the entry is the large proportion of machines of under

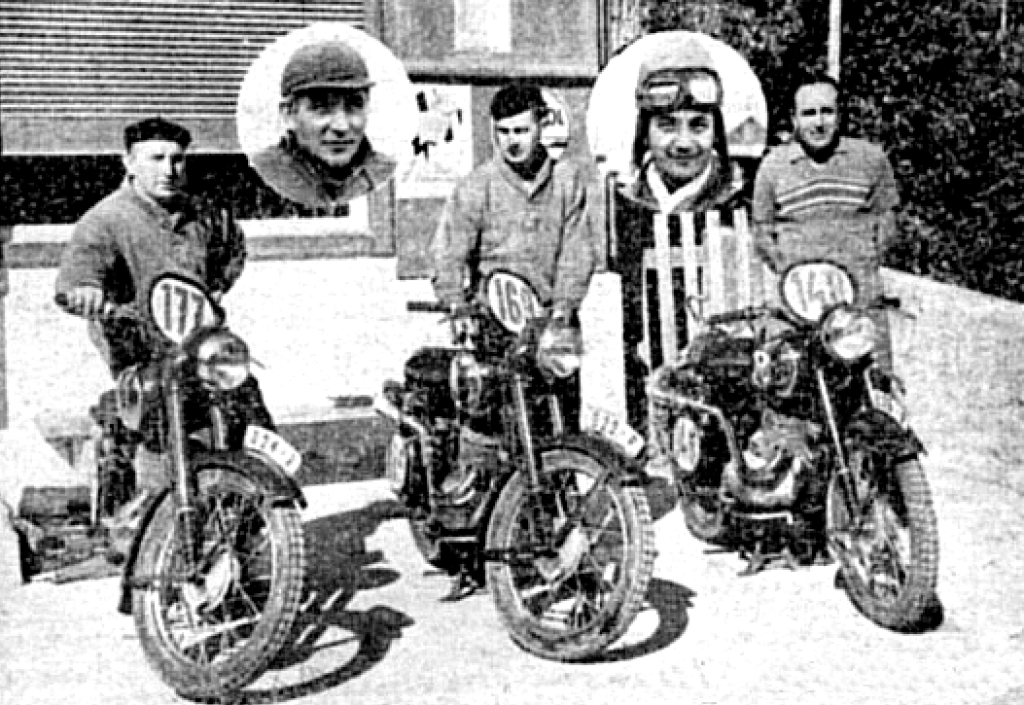

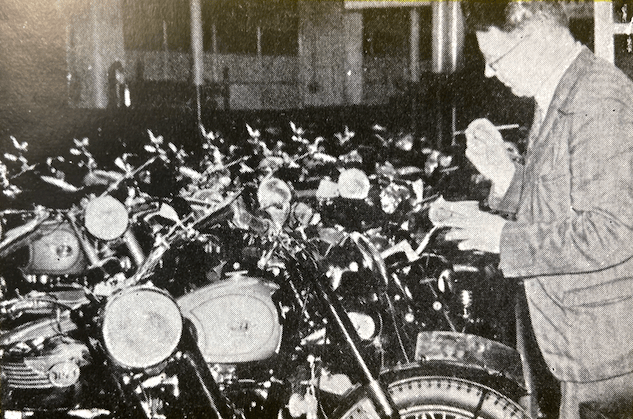

250cc. The number is 65, of which only 10 are over 200cc. It is a sign of the times—of the facts that competing expenses are high and that the modern lightweight can manage anything that a bigger machine can do, except in terms of speed. When at 8am on Monday morning the Lord Provost of Edinburgh gave the starting signal to P Victory (197 James), the roads were wet from overnight rain and a gentle drizzle had begun. There was mist, too, and visibility was down to 300 yards in places. In spite of this unpropitious outlook, however, competitors’ spirits remained high and there was no lack of light-hearted chaff as riders waited to draw their mounts from the closed control. At minute intervals the long crocodile was dispatched in numerical sequence—though this sequence will not be used throughout the week. The smaller-capacity machines, which run on a lower speed schedule, were set off first. Thus they would be overtaken by the larger machines. Because the speed schedules on rough-stuff last year allowed the under-200cc classes very little latitude and the schedules are unaltered this year, early numbers wasted no time in getting off the mark. A small crowd had gathered to watch the fun as competitors cleared the official garage and headed out of the capital’s suburbs for Bo’ness and the Kincardine road bridge. By 8.30am, the drizzle had increased and goggles became a hindrance. From Kincardine the route led to Yetts of Muckart, Dunning, and Bankfoot to Stoney Brae, the first observed hill. North of the Forth, the mist soon cleared; the sky brightened and held promise of a fine day. Stoney Brae’s four observed sections were preceded by a time-section. The hill is euphemistically named. The surface is steep and rutted, and abounds with massive boulders, many of which were loose. As in past years, it was the third section and the beginning of the fourth

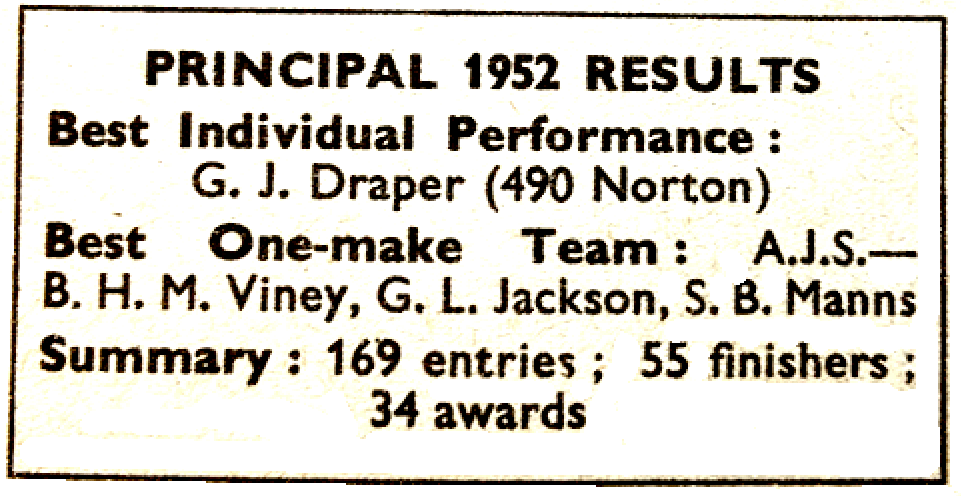

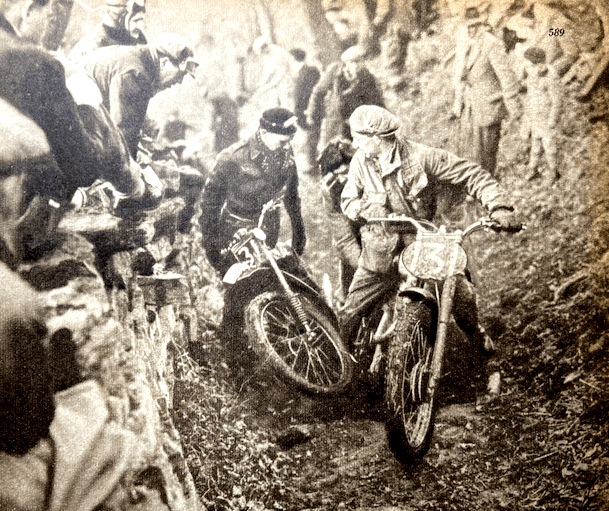

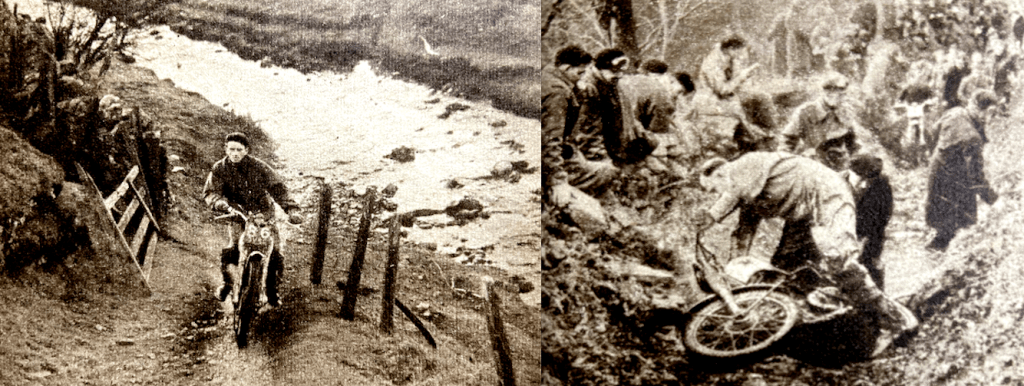

that presented the greatest difficulty. P Victory (197 James) was first to arrive. He took no risks, but paddled through cautiously, choosing a path that avoided the worst of the boulders. JW Briggs, also James-mounted, took the same path and was also non-stop. Competent, but footing, climbs were made by RS Armsden and J Botting (197 Francis-Barnetts). W Coulson (197 DMW) recorded the first stop and gave a rodeo display when his front wheel reared up and the machine turned around. A series of mediocre climbs followed. It appeared as though none of the lightweights was going to master the nasty stretch just before the end of the third section. Then HW Thorne (197 James) arrived to make the perfect performance. He was slow and careful, correcting each wayward machine movement by body-lean and throttle variation. There was applause, too, for the first of the five lady competitors to arrive, Miss Joan Slack (197 Dot). She surmounted the worst with a single dab. Another lady, Miss GE Wickham (197 Francis-Barnett), with a friction-type shock absorber on the front fork, stopped. after making a promising beginning. The ‘impossible’ was achieved by EW Smith (197 Francis-Barnett) who climbed the right-hand bank and yet kept his feet up. Immediately after Stoney Brae came Allan’s Bridge and Balhomish, two sections that were new to the Scottish in 1950. The first presented no great difficulty on Monday. The second merely entailed a ride down a greasy, boulder-strewn watercourse; it, too, caused very little bother. Scotston followed and then came Taymouth, an old favourite included last year for the first time post-war. Provided care was taken in path-picking, Taymouth was harmless. The day was now fine and warm, and the road along the side of Loch Tay to Camushurich was ablaze with the beautiful shades of green and brown peculiar to the area. Notorious Camushurich was even more vicious than usual last Monday, for it had been severely ‘doctored’ between the first and second hairpins. At first sight it looked impossible. None of the riders of lightweights could master it. When the over-200cc machines arrived to tackle Camushurich, a large gallery crowded the banks. EG Coleman (497 Ariel), the lone Australian in the entry, caused amusement when he remarked on picking up his machine: ‘Want to be a blooming mountain goat!’ In spite of the difficulties, there were many creditable performances, but they paled into insignificance alongside that of GJ Draper (490 Norton). Rounding the offending hairpin, Draper took the measure of the hill at a glance. Swiftly he turned the handlebar to full right lock and, from engine-stalling speed, turned up the wick. He put the

front wheel up the steep leaf-mould bank on the right and put the rear wheel through the gap on the right to avoid the path-blocking boulder. It looked so easy, so impudent, that it took the breath away. Like several others in the trial, Draper was wearing the experimental plastic-covered cloth Barbour suit; it is to be called the Barbourette. The lunch stop was five miles farther on at Killin, which lies at the western end of Loch Tay. From here menacing clouds could be seen hovering over the Glencoe area. Locals maintained that heavy rain was already falling thereabouts, but they were mistaken. The run through the Glen of Weeping was one of sheer delight from beginning to end. Near Kinlochleven was the formidable Mamore, the final section of the day. With its many notorious corners the hill is a law unto itself. It is very long. The surface is of loose stones—stones which shoot uselessly away from spinning rear tyres. Because of the dry spell which had preceded the trial, the surface was even more loose than usual. Of the lightweights, only WA Lomas (197 James) could deal successfully with the hill’s higher reaches. He used all the speed he could muster up to Flook’s Corner, nipped smartly round the turn and rode over the loose with as fine an exhibition of throttle control as has been seen in many a day. Few Scottish Six Days’ events take plan without someone running over the edge of the Mamore track. The honour for the first slip of this kind in the 1952 Trial went to G. Coope (248 BSA). As he went over the edge. he threw his arms around a tree and pulled himself off the machine. Then, humorously, he hugged the tree in exaggerated recognition of a service well rendered. The end was not yet in sight. Ahead lay the rocky, rutted 11 miles or so of the old Mamore road leading to Fort William. The track provides great scope for zestful rough-stuff riding and fittingly concluded such an enjoyable day’s riding. The total mileage covered had been 182. At 10.40pm the day’s results were avail-able. These showed that only GJ Draper (490 Norton) had retained a clean sheet. The runner-up, with five marks lost (one stop), was PH Alves (498 Triumph). Next came JV Brittain (346 Royal Enfield) and BW Martin (348 BSA), each with six marks lost. They were followed by G Parsons (348 Ariel), with eight marks gone; and he was followed by TU Ellis (499 BSA), David Tye (348 BSA) and GL Jackson (347 AJS), all with nine marks lost. Best in the under-200cc class was WA Lomas (197 James), with 19 marks lost.” Five days later Johnny Brittain won the 1952 Scottish Six Days Trial; he finished with 22 marks lost.

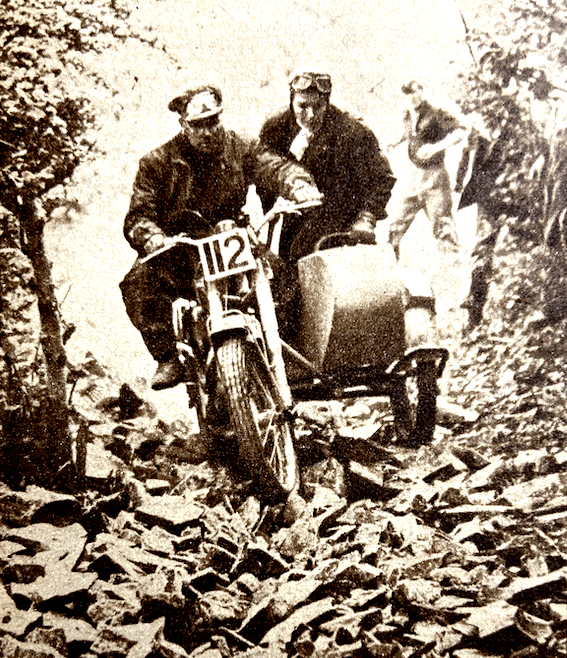

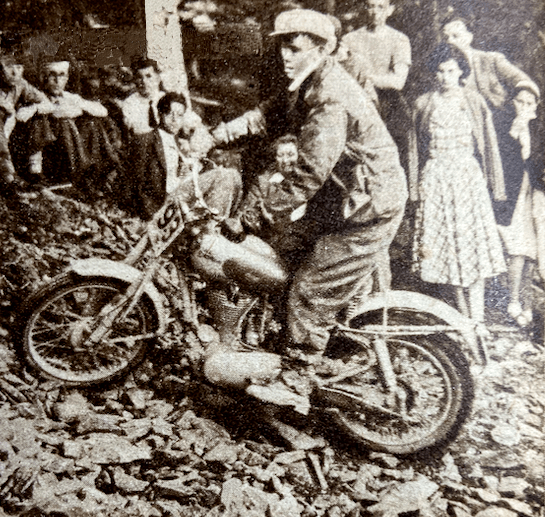

“RUN OVER A super-sporting, mountain course in some of the most rugged and beautiful areas of ‘wild Wales’ last weekend, the national Welsh Two-day Trial drew a record entry of 113 (last year’s entry totalled 78). On the first anniversary of the event, therefore, the organisers, the Mid-Wales Centre, had the satisfaction of knowing that the popularity of their highly-specialised event is increasing and that their enterprise in inaugurating it has been well justified. Fresh from his victory in the Scottish Six Days’ Trial, JV Brittain, riding his 346cc Royal Enfield, remained on top of his form to win the event by a clear-cut margin; he lost only four marks on observation and none on time. His nearest rivals were DS Tye (348 BSA) and PJ Mellers (497 Ariel), each of whom lost nine marks on observation and won the 350 and 500cc cups respectively. Best performance among the sidecar entry of six was made by F Wilkins (497cc Ariel sc) with 31 marks lost. As might be expected, with the trial based in Llandrindod Wells, good humour ran high and there was an air of joie de vivre among riders, officials, and spectators alike. With almost as much depending on the maintenance of tight time schedules over the rough stretches of the course (which meant over most of it!) as on performance on observed hills, there was also, about the event, a trace of ISDT atmosphere. Many riders carried spare inner-tubes and large inflators and many were using rear-sprung twins. A highlight of the event was that WJ Stocker was in charge of a thrilling new 700cc Royal Enfield vertical twin, which was equipped to semi ‘International’ specification. Under a warm, early-morning sun, which beamed out of a clear blue sky, the chairman of the Llandrindod council, councillor WH Edwards, JP, started the first competitor on the 135-mile route for the first day, Friday. Before reaching the first observed section, Fellwyd, some 50 miles, embracing three time checks, had to be covered. Very little

main road was encountered and the going was mostly over loosely-surfaced, winding, secondary and unclassified roads—roads of the type calling for the utmost road-craft, if the speed schedule was to be maintained without resort to ‘risky’ riding methods. The observed section did not rob many of the experts of marks, but the short stretch of smooth, slimy rock slabs required to be treated with more than a little respect. Among the first arrivals was DS Tye (348 BSA). Tye arrived dead on time, and made a very slow, controlled ascent, demonstrating among other things that his engine was in perfect tune. Slightly faster over Fellwyd were JV Keenan and WL James, both riding Trophy Triumphs, but they were equally untroubled. Unexpectedly, WJ Stocker on the 700cc Royal Enfield was bothered with wheelspin, and he had to foot his way out. Through overshooting a turning leading to the section, JV Smith (490 Norton) was some 30 minutes late; he lost no marks on the section, and when he left he was in a hurry! From Fellwyd riders were treated to the wild splendour of the Tregaron Pass before reaching the lunch check. After their brief respite they had to traverse a longish stretch of open mountain to get them to Pen-y-Gareg, the next observed hill, which lay in the Elan Valley. Time schedules, incidentally, were based on the nature of the terrain between various checks, and were in the proportions, 24, 26 and 30mph for solos up to 150 and 250cc, sidecar outfits, and solos over 250cc respectively. Pen-y-Gareg provided an interesting mixture of loose slates and earth and a 1-in-2 gradient. There were many clean climbs, among the best of those seen being by DS Tye, E Sellars (497 Ariel) and JV Britton, The course then led through the small town of Rhayader, where it appeared as though at least half the population was lining the roads to cheer competitors, and the police force, as in Welsh ‘Internationals’, was co-operating to the full. The route to the last two observed sections of the day, near Llandrindod Wells and the finishing point, lay over the tops of mountains and along forestry roads, ‘to give riders an enjoyable half-hour’s scramble riding!’ At the first of the sections, Cwm-Gwyn, an excellent climb was made by L/Cpl JSH Bray, who, with a superb show of riding, and using lots of correcting body-lean, took his WD 347cc Matchless through the tricky mud and boulders unpenalised. DV Chadwick took his BSA Bantam through in fine style, and another

Bantam rider to go through feet up was L Wyer. One of the two lady competitors, Miss Olga Kevelos (497 Ariel) was clean in the early part; then she had trouble in the second sub-section, recovered, and required two dabs. Cefn Coed, the final section, contained a measure of deep mud of plum-duff consistency. Though the section was level and straight, the ruts were long and deep and only JV Smith among the solos rode the entire length unpenalised. JE Breffit (450 Norton) came close to success, but was forced to use three dabs—two of them when he was almost at the ‘ends’ card. Strangely enough, in the circumstances, FH Whittle (598 Panther sc) and F Wilkins (497 Ariel sc) drove their sidecar outfits through fast in great style without losing marks. Early morning mist and a clear blue sky above heralded another glorious day on Saturday for the second half of the trial. Machines had been impounded during the night and there was an easy-starting test before riders set off—this was in addition to the three other special tests (acceleration and braking) during the event. Eight observed sections were included in the course of Saturday’s route of 114 miles, which was also timed, of course. At the first section, LIwyncutta, spectators were treated to a masterly display from DM Viney (347 AJS). Viney inveigled his machine over muddy rock slabs and through a quagmire at the exit from the section with all the grace and skill that is his alone. A praiseworthy performance was made also by the second of the two lady competitors, Miss Joan Slack (197 Dot). Many excellent sections were included in the day’s route, but the highlight was Kinsley, the long stony track bristling with rock ledges, that climbs steeply up the side of a 300ft cliff towering above the roofs of Knighton. It was said that no one had ever climbed it unpenalised, and it presented for riders an awe-inspiring prospect. There was an early sensation when F Allen (123 BSA) rode feet-up almost to the top before hopping out of the saddle when his engine was about to stall. One after the other, the experts were defeated. Most of them made non-stop climbs by dint of heavy footing, and the bulk of the remainder of the entry required tow-rope assistance. The spirited charge by HL Williams (490 Norton) was typical of many who forfeited a non-stop climb in a gallant attempt to ride the entire section feet-up. Williams stormed his way over the worst part with his feet glued firmly to the rests, but eight yards from the end he lost control and dropped the model. When most of the entry had passed Johnny Brittain arrived, still with a clean sheet for the day—he had only lost four marks the previous day and was at this stage in the lead. After carefully weighing the prospects, he made a superbly-judged climb, and a tremendous cheer arose from the crowds thronging the banks when he rocketed out of the section still under control and still feet-up. Not only had he made almost certain of winning the trial but he had made local history by being first to conquer the hill. A word of praise is merited by Clerk of the Course, HP Bangham, and his merry band of fellow organisers. They did a first-class job—a really first-class job throughout the two days. RESULTS Welsh Solo Trophy: JV Brittain (346 Royal Enfield), 4 marks lost. Welsh Sidecar Trophy: F Wilkins (497 Ariel sc) 31. Knighton Cup (best 150): EW Smith (122 Francis-Barnett), 32. Llandrindod Cup (best 260): R Armsden (197 Francis-Barnett), 27. Rhayader Cup (best 350): DS Tye (348 BSA), 9. Metropole Cup (best unlimited cc): PJ Mellers (497 Ariel), 9. Spa Cup (best 350 sidecar): RU Holoway (348 Panther sc), 67. Walters Cup (best unlimited cc sidecar), AG Brown (490 Norton sc), 45. Builth Trophy (best one-make team): AJS (BHM Viney, GL Jackson, PF Richards), 74. Presteign Cup (best club team): Sunbeam MCC (GL Jackson, PJ Mellars, J Giles), 31. Morgan Cup (best Mid-Wales member): WB Mills (498 Triumph), 27. Services Cup (best Army rider): L/Cpl JSH Bray (348 Matchless), 42.”

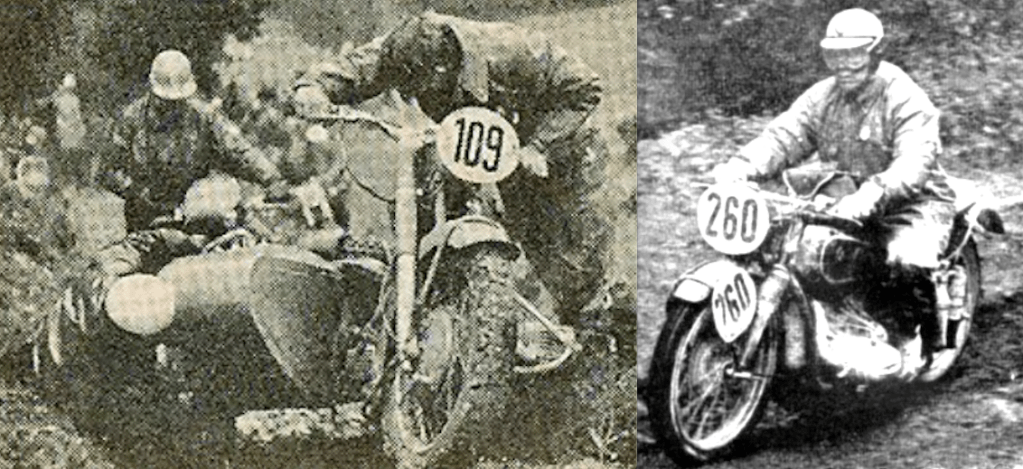

GET ON PARADE! The Royal Artillery dominated the third Army Motorcycle Championship Trial. Nearly all the 84 entrants rode G3L Matchlesses; much of the course followed the route of the 1948 and 1949 ISDTs.

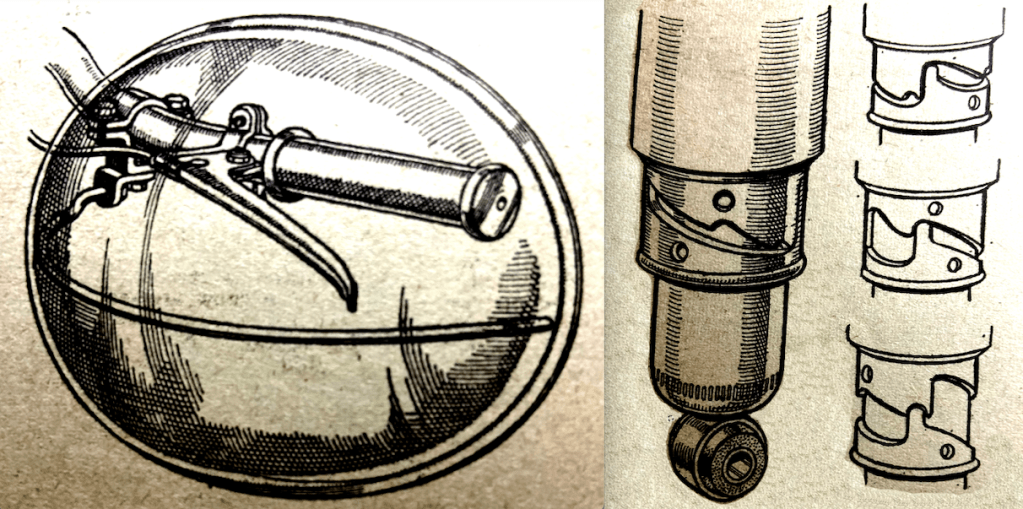

“THE REPORT TO the Minister of Transport on Motor Cycle Accidents by the Committee on Road Safety, in considering the rise in the number of motor cycle casualties, draws attention to the greatly increased number of motor cyclists on the roads. Figures quoted are 32,771 casualties in 1938, when there were 443,651 motor cycles (and similar-category machines) registered; the percentage of casualties was 7.3. In 1950 there were 37,390 casualties and 729,420 machines registered, giving a percentage of 5.12, but it will be recalled that petrol was rationed, and therefore mileage was restricted, for five months during 1950. Conclusive evidence of the reduction in the accident rate is provided by the year 1951, when there was no petrol rationing, and a valid comparison with the last normal pre-war year, 1938, can be made. In 1951, casualties numbered 42,680 or 5.18% of the 822,571 registrations. Hence, since 1938, there has been a drop of more than 2% in the casualty rate in spite of heavier traffic on less satisfactorily maintained, overcrowded roads. The Committee’s recommendations are constructive and of the utmost value in discrediting the common supposition that motor cyclists as a body are wholly culpable for the accidents in which they are involved. Motor cyclists bear their share of responsibility, but no more. Many of the recommendations are on the lines of suggestions made over a long period by The Motor Cycle and other interested parties. Attention is drawn to the danger of slippery surfaces and the need for the Ministry of Transport and highway authorities to remedy such surfaces. It is recommended that the rear lighting and driving mirrors of other vehicles should be improved; that measures for the control of dogs on the highway should be introduced; that the use of crash helmets should be encouraged (assuming a suitable helmet can be produced at a reasonable cost); that driving tests of motor cyclists should be conducted by examiners who are riding motor cycles; that there should be more police patrols mounted on motor cycles; and that the RAC-ACU Training Scheme should be expanded. ‘In essentials,’ says the Report, ‘the problem does not differ from the accident problem generally, and the preventive measures must be a combination of education, enforcement and road and vehicle improvements. The importance of proper training of learner motor cyclists cannot be overstressed.'” The report also concluded: Motor cycle manufacturers should consider further standardisation of motor cycle controls. The development of the auto-assisted pedal cycle and autocycle should be carefully watched. Driving mirrors on motor cycles should not be made compulsory. Direction indicators on motor cycles should not be made compulsory. The value of leg guards should be investigated. Proper footrests should be a requirement for all motor cycles used for carrying pillion passengers. The use of goggles with side panels should be encouraged. Special restrictions on the speed of motor cycles either in relation to the age of their riders, or generally, should not be imposed. The vulnerability of motor cyclists should be discussed between the Department and the motor cycle manufacturers. A booklet on roadcraft should be issued with all new motor cycles. Films on safe motor cycling technique should be produced and made available to interested parties. Auto-assisted pedal cycles and autocycles should be placed in a separate group for the purposes of driving tests and licences, and the question of a separate group for motor cycles of over 350cc borne in mind. The accident position among learner motor cyclists should be watched with a view to consideration being given to limitation of the number of provisional licences which a learner driver may be granted. “It seems clear, says the report, ” that the upward trend in motor cyclist casualties is largely due to the increase in this class of traffic.” Of 16,511 crashes recorded in the police reports skidding accounted for 15%; misjudging clearance, distance or speed, 12%; excessive speed in the prevailing conditions, 11%; overtaking improperly, 11%; lack of care at road junctions, 8%; inattentive or attention diverted, 7%. “The vulnerability of the rider is shared by the pillion passenger. Though no statistics are available to show whether motor cyclists with pillion riders are more likely to be involved in accidents than are solo riders, it is obvious that, if there is an accident, two lives are endangered instead of one. There is a temptation for a young rider with a girl on the pillion to show off by driving at excessive speed. A warning about the foolishness of succumbing to this temptation should be given special stress in the education and training of motor cyclists. A sample investigation of the ages of motor cyclists killed or injured in road accidents showed that about 50% of the casualties were in the age group 19-27. However, there is no information available about the ages of motor cyclists licensed.” Triumph boss Edward Turner said: “It is in refreshing contrast to the usual nonsense one reads almost daily on the same subject. As manufacturers, we heartily endorse the principal recommendations relating to the condition of road surfaces, rear lighting of other vehicles, and straying dogs. To those authorities who find difficulty in providing non-skid road surfaces we would commend a visit to the Isle of Man, where it is possible to lap the tortuous TT course at 90mph in safety on the wettest day. In many of our biggest cities it is almost impossible to travel at 10mph with any degree of confidence after a shower of rain. Motor cycles, by their liveliness and the sport they provide, appeal mainly to the young, and youngsters will always get themselves into trouble on occasion whatever sport they take up. Danger is an inherent part of any real sport, and it would be a sad day for this country if our youngsters preferred the safe pleasure of watching television to getting out into the country on a motor cycle or bicycle, or climbing mountains, or any other real sport which calls for a little courage and dash…since 1938 the number of motor cycles on the roads has increased almost 100% but the accident figures show an increase of only about 25%. There is, of course, no reason for complacency, and every effort must be made to effect a considerable improvement.”

I CAME ACROSS THIS comment piece in a French bike mag: “Better thirty dead than one wounded: When a plane crashes with thirty passengers on board, we blame the sky, the mountains or the ground, which are solely responsible for the disaster. We recover what we can from the victims, give them a beautiful funeral and open an investigation, which is soon, but more discreetly, buried. When two trains travelling on parallel tracks, which by definition cannot meet, are nevertheless clumsy enough to collide, those who did not survive the crash are given a magnificent burial, fine speeches are made, fate, frost, fog or the scapegoat are blamed, and we move on to other matters. Each time, there are massacres to lament, but these do not in any way tarnish the solid reputation for safety of the giants of the air or rail. But if an unfortunate motorcyclist knocks over a careless pedestrian who suddenly appears outside a pedestrian crossing, everyone immediately cries ‘Haro’ on the donkey; this tiny machine is, in evil hands, the most formidable killing machine in the world. If two million motorcycles are responsible for fifty accidents, that’s fifty accidents too many; we must crack down with the utmost severity. Others have the right to cause mass carnage, but an occasional accident here and there is something we cannot tolerate. This is the triumph of mass production.”

“SURPRISE AND POSSIBLY consternation will arise over the FIM decision to allow superchargers for road racing. Undoubtedly the FIM will suffer a good deal of criticism for introducing the change without notice, bearing in mind the understanding that no vitally important modification to road-racing regulations would be made without three years’ warning. Two other points of possible criticism arise. A British rider was suspended for a year at the last Autumn Congress. The suspension has been remitted by a few months, and the rider will be allowed to compete again from 1 July. He was suspended without a hearing, and only sketchy details of the charge have been made public. It is widely felt that FIM rules should be modified to ensure that a rider may state his case before suspension is enforced. Secondly, the two fatal accidents at the Swiss Grand Prix have brought into focus the fact that the FIM permitted the meeting to be held in spite of its own rule that classic motor cycle races shall not be run on the same circuit and on the same day as car events. It appears that the FIM is quick to deal stringently with riders, yet compromises with its own constituent bodies in the application of its rules.”

“WHEN THE ZEBRAS first came into use, I prophesied that many of them would need to be operated by a uniformed policeman in days to come, if only spasmodically. I spent Easter at one of our better-known watering places. The holiday crowds were by no means gigantic, but in the centre of the town all the (very few) zebras were necessarily controlled by point cops over a considerable portion of each fine day. Otherwise the dual hold-up of angry peds and angry motorists would have led to troublous scenes. I heckled a local official for his view of the matter. He said in effect, ‘The zebras are important to us on grounds of economy. In normal times, when traffic is not too heavy, a little colour on the road surface renders a service which would otherwise demand a human agent or an expensive robot lamp installation. We don’t know yet how often we shall have to supplement the zebras in the town centre by posting constables at them, but in any case they will still be extremely economical. It is too early to estimate the aspects of safety and danger, but we are well pleased with their safety up to date.”—Ixion

“I READ OUR sprightly contributor, ‘Technicus’, with a slightly rueful air. ‘Several periods in my ill-spent life have caught me in charge of engines with more than one carburettor. I think the record number was four, though I sometimes wonder whether it wasn’t eight. The job is not too foul if the engine has stub exhaust pipes and no silencers. You carefully adjust one carburettor till you get the tongue of flame with the right colour. You then bring the other carburettors up to the same standard. But this noisy task makes for acute neighbour trouble. So if the job has silencers and prolonged exhaust pipes, you have to take the vehicle bodily up to some lonely place atop of the Pennine hills or suchlike, dismount the exhaust system, set the carburettors, and remount exhaust plumbing. Even then some stupid little item soon upsets the balance, when you have to revisit your mountain summit to put it right. Whereupon the local cops begin to suspect that you are running a pot still and brewing your own whisky. One carburettor is plenty for me on a touring model, thank you.”—Ixion

“CS JONES CONSIDERS that 90% of fast drivers are competent. His thesis can’t be proved. I think that many youthful speedmen are most temerarious. But I will append two samples which tend to pillory the creepers. How many readers know the psychological effect of a tram? Nobody likes running either alongside or just astern of a tram or similar incubus. They occupy an immense slab of road. They block your view ahead. They can (and do) stop most incredibly quickly. When I find myself behind a tram, my instant and powerful reaction is to overtake it. I know as well as you do that there is probably another tram about a hundred yards farther on; and that tram C is probably rollicking a few yards ahead of tram B. No matter! I miss no possible chance of passing every tram I encounter. Again, I never ride quite so foolishly as when I am on something slow, especially in hilly country. Given a clear field, I am compulsorily rather slow over the ground, because my machine can’t do more than so-and-so. So I am loth to slow adequately at awkward corners, and will face almost any risk up a lengthy hill, lest I should be forced off top gear and be unable to change up again for a mile or so. These are two very common factors in accidents; the creeper brigade is especially susceptible to them.”—Ixion

“HOW VERY, VERY SELDOM one sees a motor cyclist tinkering by the roadside! This is no mean tribute to the industry. In a sense it is rather a surprise to me, for today quite a sizeable percentage of us ride clip-ons or autocycles of various types. Many of these riders have still to acquire the smattering of mechanical knowledge requisite for keeping any model in good running order. Hats off to designers and makers—they have done a very goof job.”—Ixion