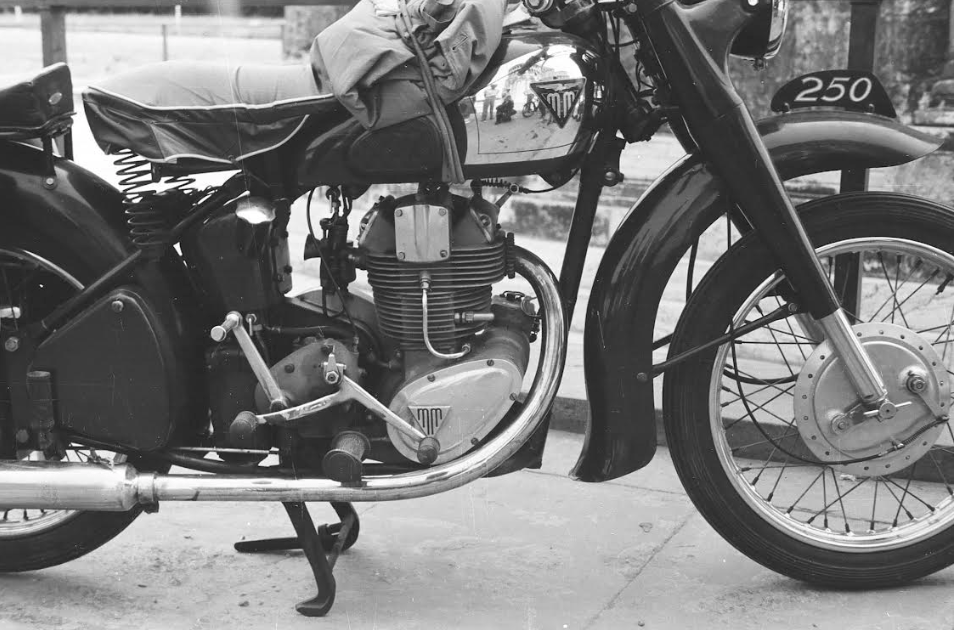

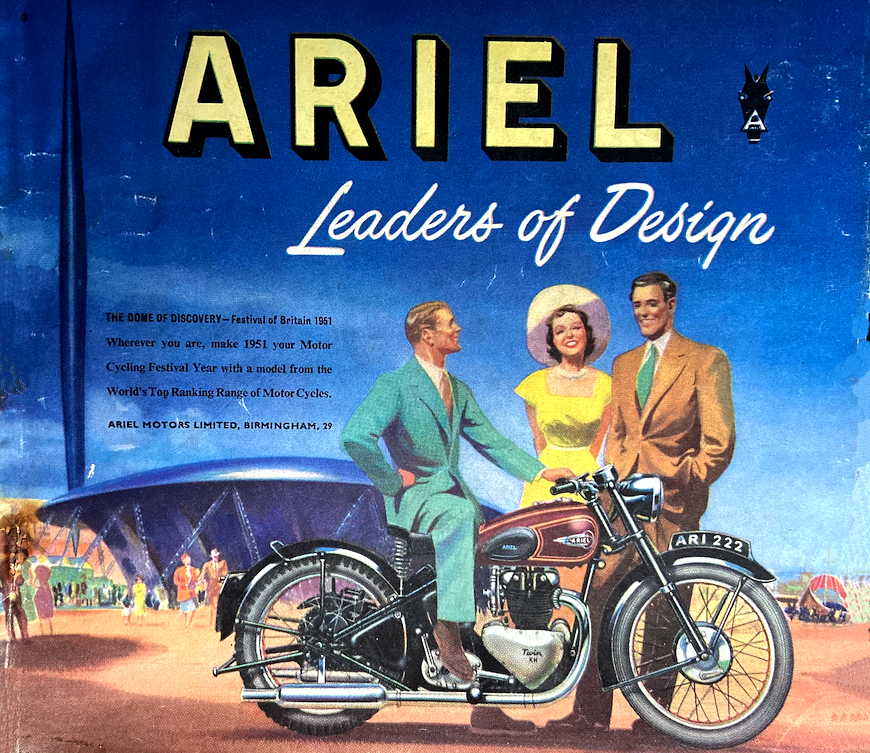

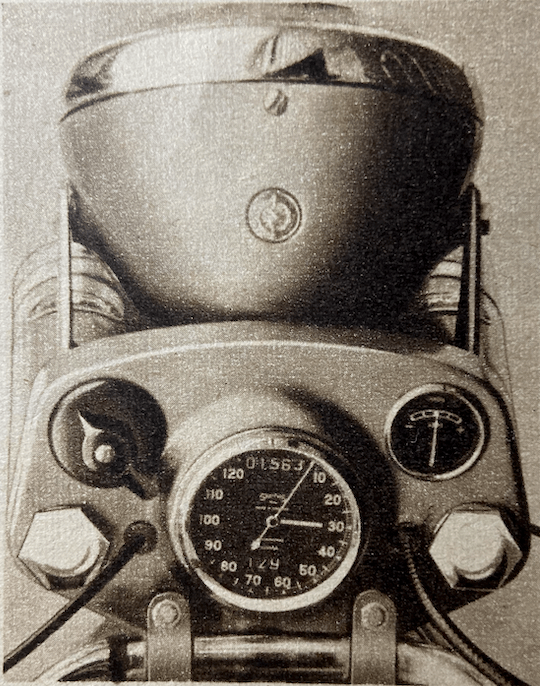

“ARIELS ARE HERALDING a trend which is influenced by the imminent (within a few years I would say at a guess) change-over from magneto-dynamo to AC-generator ignition and lighting equipment. Because of the character of its construction, the AC-generator requires a positive earth return, and by making the polarity change now, Lucas feel that people will be taking positive earth for granted when the time comes for it to be all but standardised. So far as coil-ignition multis are concerned, of course, the positive earth has definite advantages. It means, for instance, that there is a negative polarity spark at the plug (which tends to give lower plug voltages) and burning in the distributor is spread over the separate brass electrodes instead of being confined to the rotor arm…Ariels are already using the new coloured harness. It is an obvious improvement on the more common type with coloured rings, because these ‘idents’ are for ever being pulled off and lost. Personally, I look forward to the day when the new harness is universally adopted.”—Nitor

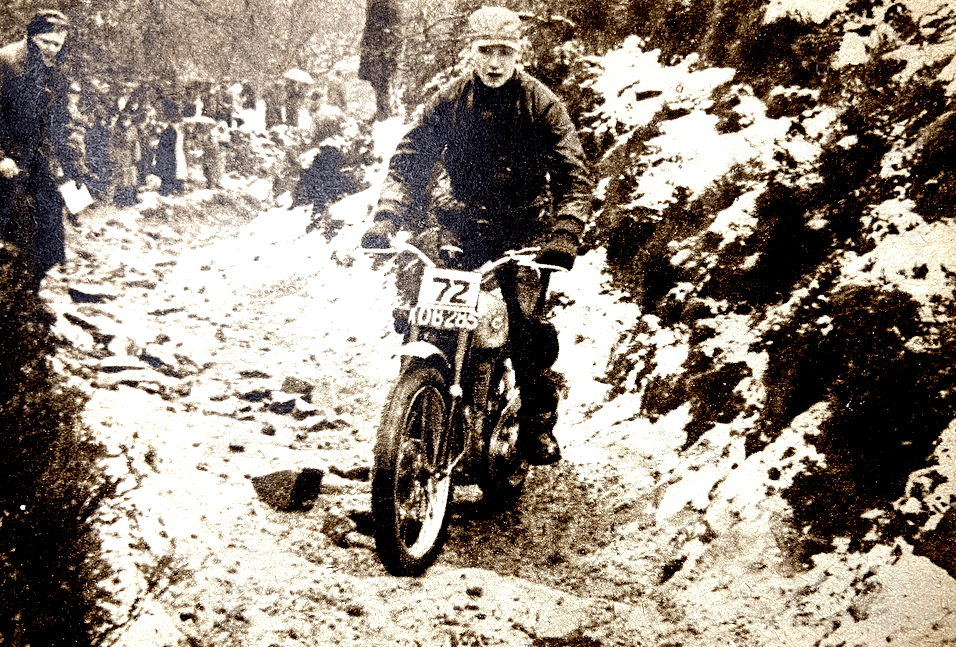

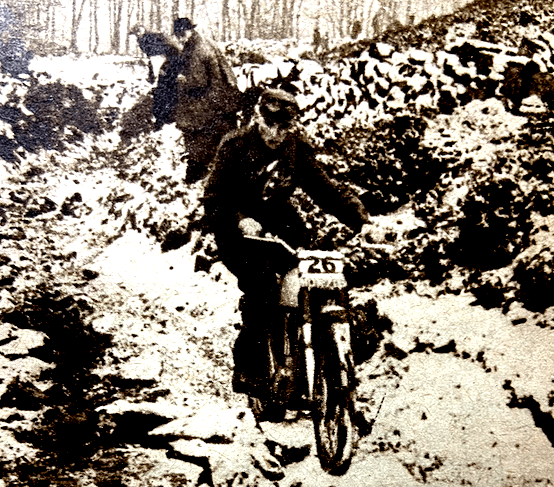

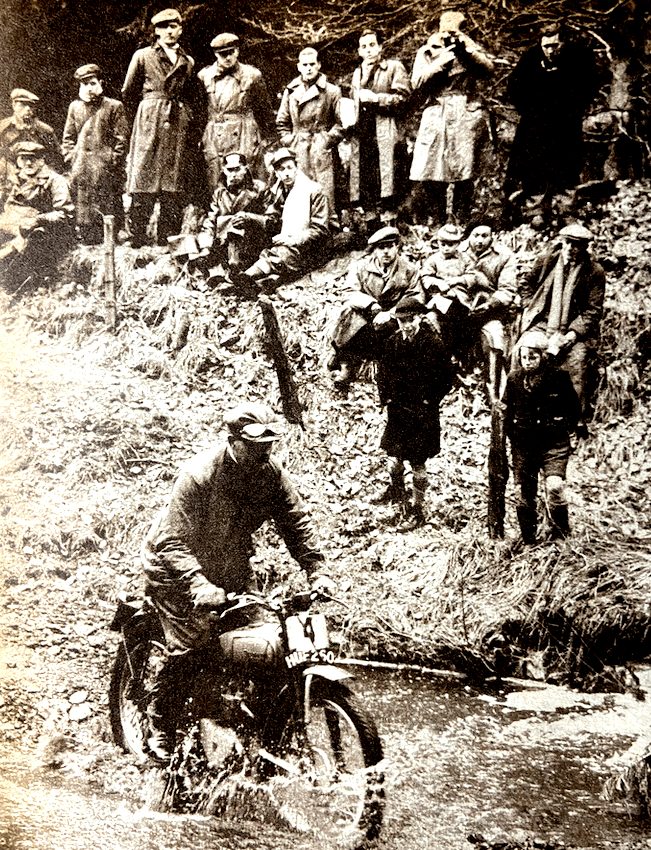

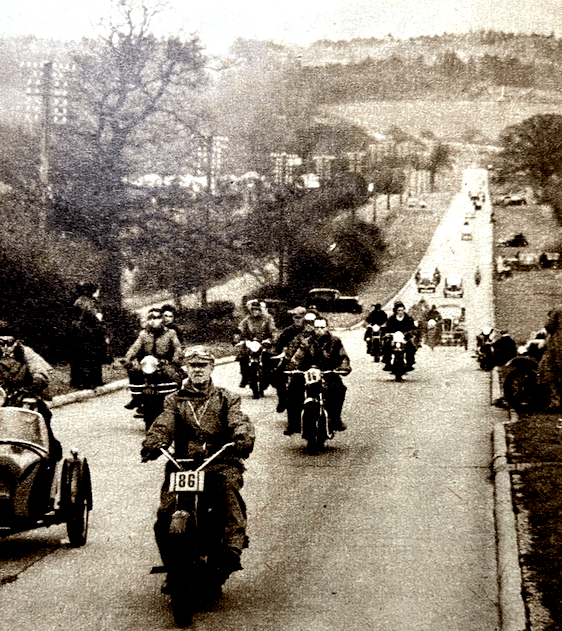

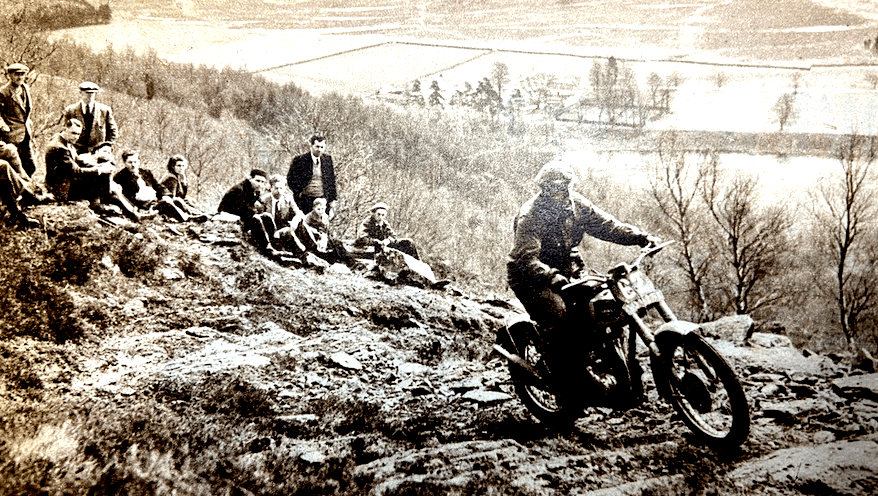

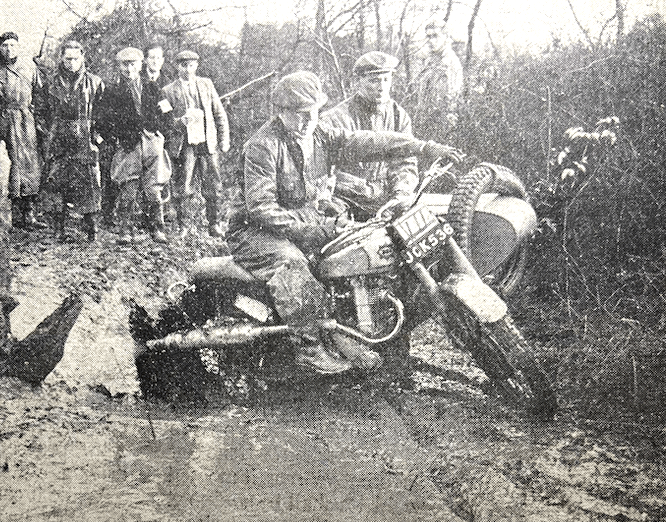

“PITY THE POOR Pathfinders & Derby Club, for assuredly the words ‘snow’ and ‘Bemrose’ are synonymous. As usual, last Saturday’s Bemrose Trial was held ‘mid the Derbyshire hills and dales. At 10am, when the first competitor was scheduled to start, snow was falling in petulant spasms, and the strong wind on which it rode had a cutting edge—and then some! The clouds were so low that they blanketed down to road level only a mile from the Bull i’ th’ Thorn, the headquarters hotel. On the roads the snow lay in an off-white carpet, effectively concealing the marking dye. Consultations were held. What was to be done? Course-finding, it was decided, would not prove too difficult because marking had been carried out with cards as well as with dye. But would the 150 competitors be able to complete the 72-mile course before dark? In order to overcome the difficulty, the course was shortened by 20 miles (leaving 10 of the planned 15 sections). And at approximately 10.20 the first man set out in a howling storm, heading for the first section, Dow Low. This hazard deservedly has the reputation of being a severe marks snatcher. In the first few yards there is a

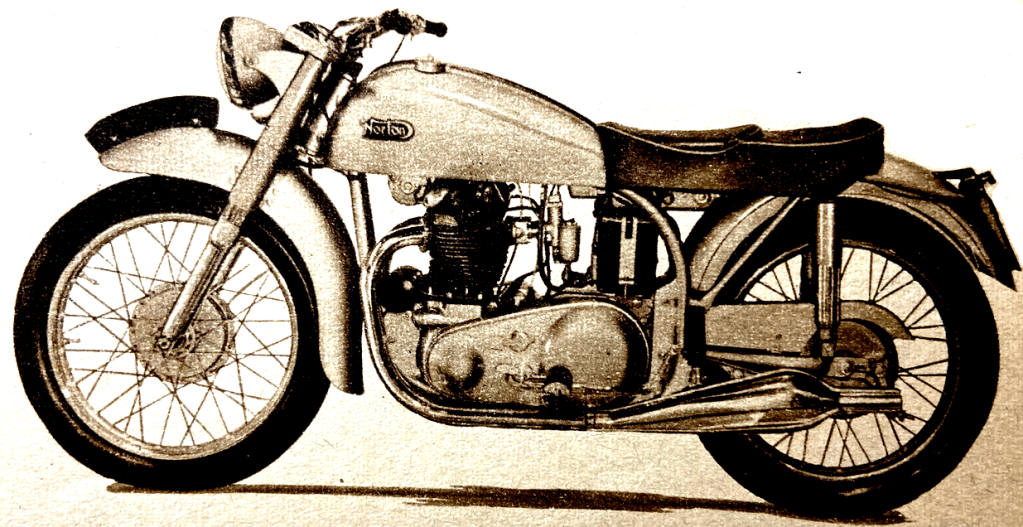

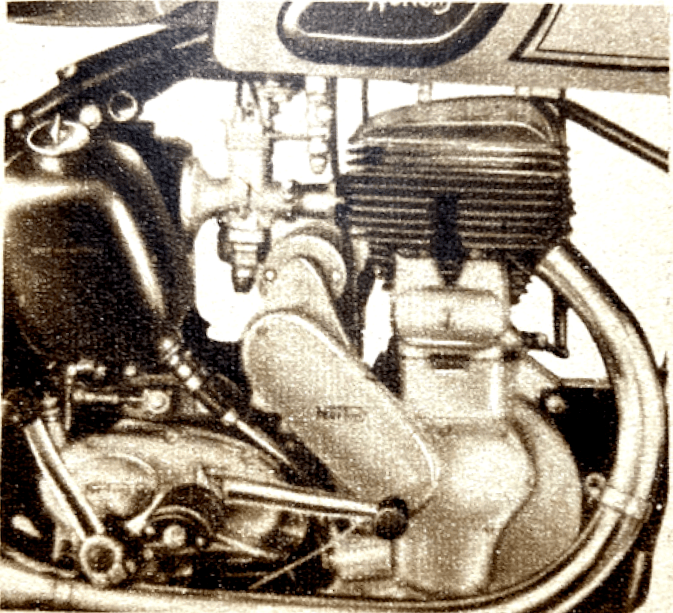

right-left S-bend over an irregular, slimy, rocky surface. Path-picking round the S is important because of an awkward camber, but selecting a line was made very difficult on this occasion because of the carpet of snow, and the falling snow which was stinging competitors’ eyes. The rocky S dealt with, the worst of the section is past. All that remains is (or was last Saturday) an easyish climb over a mixture of earth and grass. Among the first 30-odd riders to tackle the hill, only one was clean. He was R Clayton (490 Norton). Whereas all others followed the most obvious path, Clayton went very wide on the first turn of the S. This allowed him to enter the short straight between the two corners with his Norton upright and the wheels in line. It was the perfect tactic, and Clayton’s demonstration made the section look absurdly easy. Yet, the difficulty experienced by the vast majority of the entry proved that this was far from so. The next section was Washgates and it, in turn, was followed by Hollinsclough, probably one of the most famous of trials hills. Heavy rains before the Bemrose, however, had washed most of the slime from the rocks rendering the hill much easier

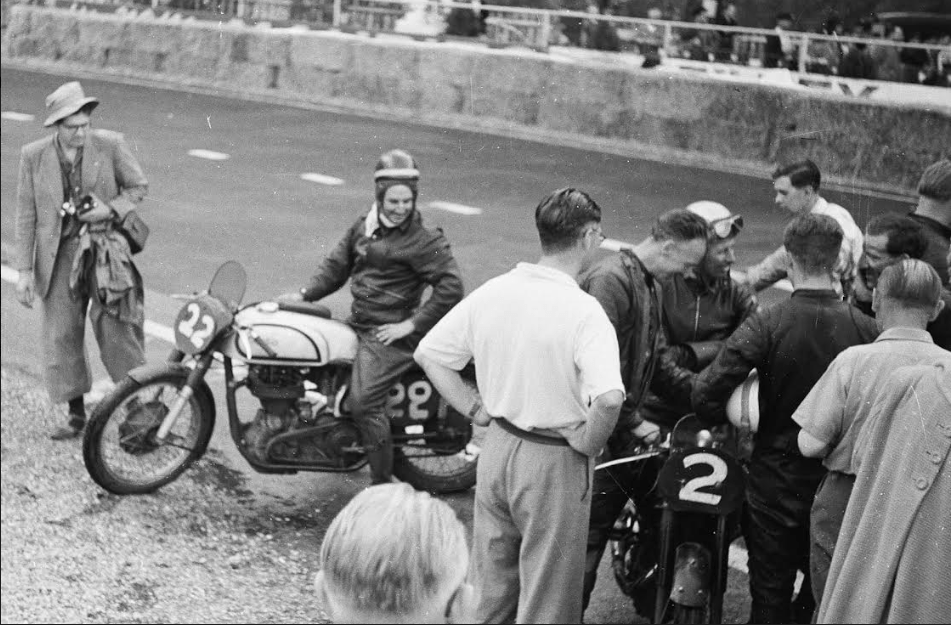

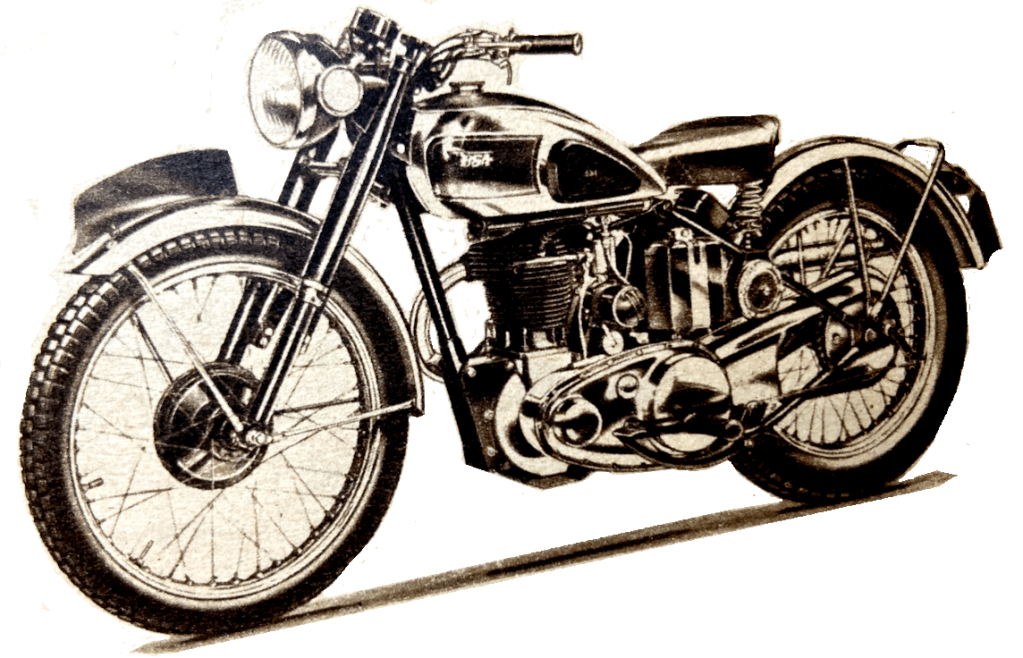

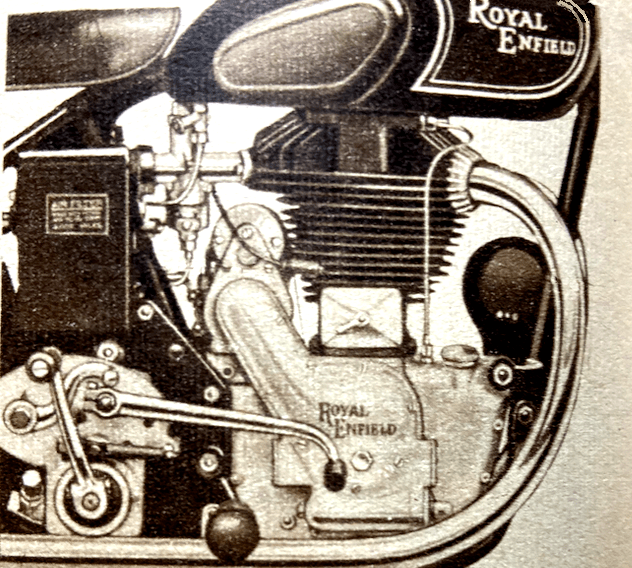

than usual. Nevertheless, it proved sufficiently difficult to take a toll of marks on a grand scale. Among the most impressive machines on the hill were the rear-sprung Royal Enfield Bullets and the VCH Ariels. Both R Chidgey and GW Fletcher, for instance, on Bullets, made most spirited attacks which came within an ace of success. G0 Bridges (347 AJS) was impressive indeed, until he came to an abrupt halt near the top with a stone lodged under his crankcase. Three of the most impressive climbs up as far as could be seen from the second sub-section were those by D Tye (348 BSA), RB Young (490 Norton) and JE Breffitt (490 Norton). Breffitt’s machine, incidentally, was a works model which he will ride in open competitions, including the Scottish and International Six Days’ Trials, during this year. Another most impressive climb was that by KR Craggs (197 James) who was beautifully and effortlessly clean through the last and most difficult sub-section. H Wiley caused a stir by turning out on an Excelsior Talisman Twin which performed magnificently over the rocks. He had a stop in the third sub-section, yet he purred an effortless passage through the final one. Both Miss Ann Newton and Mrs. M Briggs, of the James ladies’ team, had stops. None of the sidecars seen

made non-stop passages farther than the end of the first sub-section. In each case, the outfit tended to overturn—either to one side or the other. After Hollinsclough came Pilsbury, which was fairly easy for early numbers but increased in severity as the entry passed through. There was a particularly nasty few feet just before the end of the section which, on Saturday, was just round to the left at the top of the hill. By midday the snow had changed to heavy sleet which soaked through gloves, numbed hands, and stung ungoggled eyes. From Pilsbury competitors rode to Manifold Quarries, then to Ryecroft, Netherhay, Blackbrook, and the old section at Cheeks Hill. Then there was a check at the Travellers Rest before the Bull th’ Thorn, where competitors signed off and had a cup of nice, hot TEA! RESULTS Bemrose Trophy (best performance): J Giles (348 BSA), 0 marks lost. News of the World Cup (best opposite class): CV Kemp (400 Norton sc), 10. Lapidosa Cup (next best solo): E Sellars (497 Ariel), 0. Green Cup (next best sc): GL Buck 497 Ariel sc), 15. Telford Trophy (best 150cc): BW Martin (122 Francis-Barnett), 6. Committee Cup (best 250cc): HW Thorne (197 James), 1. Alan Smith Cup (best 350cc): TH Wortley (348 Douglas), 0. Ian Robertson Cup (best 500cc): TU Ellis (499 BSA), 1. Best Club Team: Belper (Thorne, Lomas, Phillip), 13. Grantham Cup (best performance by an EM Centre resident, not winning a major trophy): W Lomas (197 James), 2. Souvenir Award (best performance by a lady): Mrs M Briggs (122 James).”

“THE FIRST FORT RALLY, open to members of ACU-affiliated clubs in the Midland Centre, held last Sunday, was christened with steady rain practically all day; short, bright periods were few and far between. Nevertheless, this did not deter the enthusiasm of both organisers and competitors. The 31 motor cycle entries ranged from a very old belt-drive Douglas, which had to retire with belt-slip owing to the wet weather, to the newest model Vincent Rapide. The Wolverhampton Club put up a very good show in winning the team award. A special merit award was presented to 16-year-old R. Bates, riding a solo BSA.”

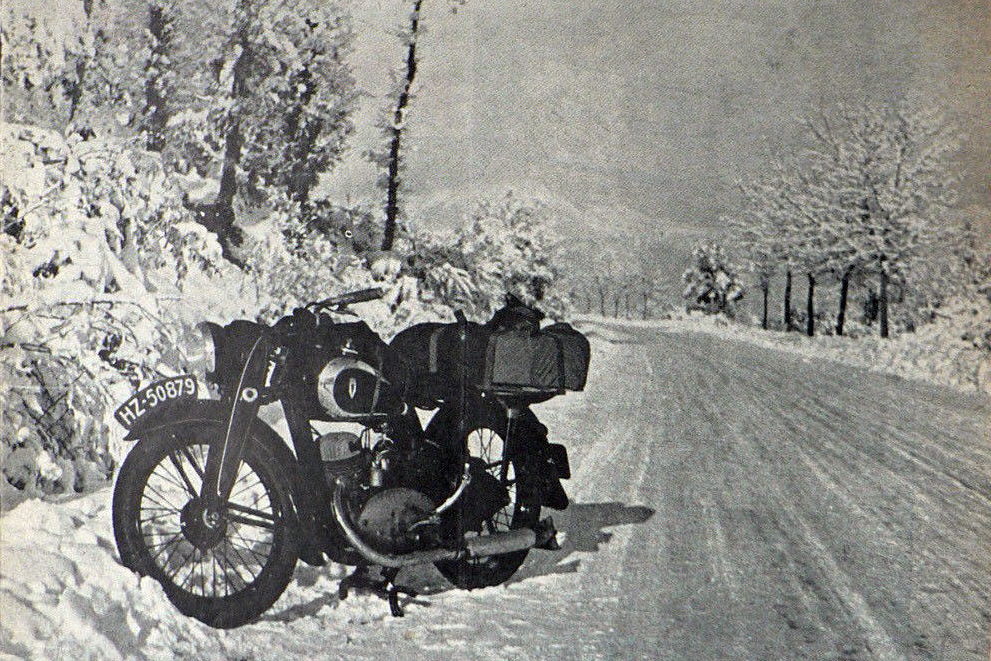

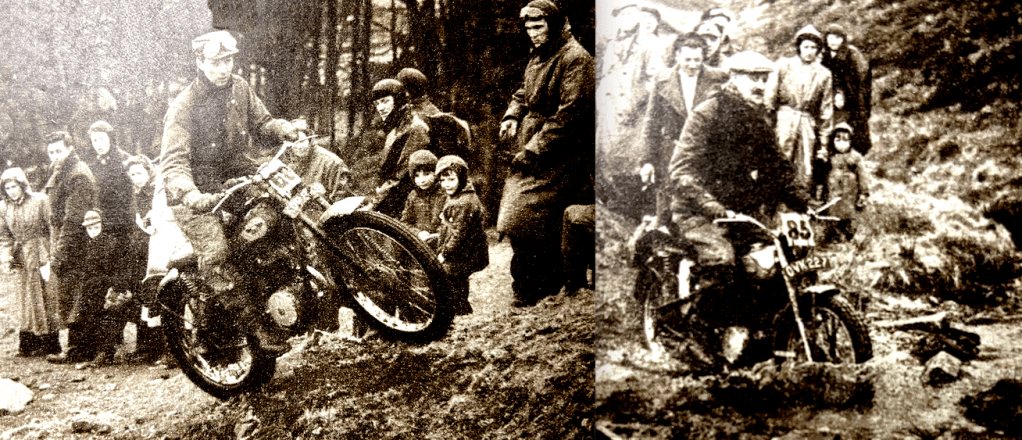

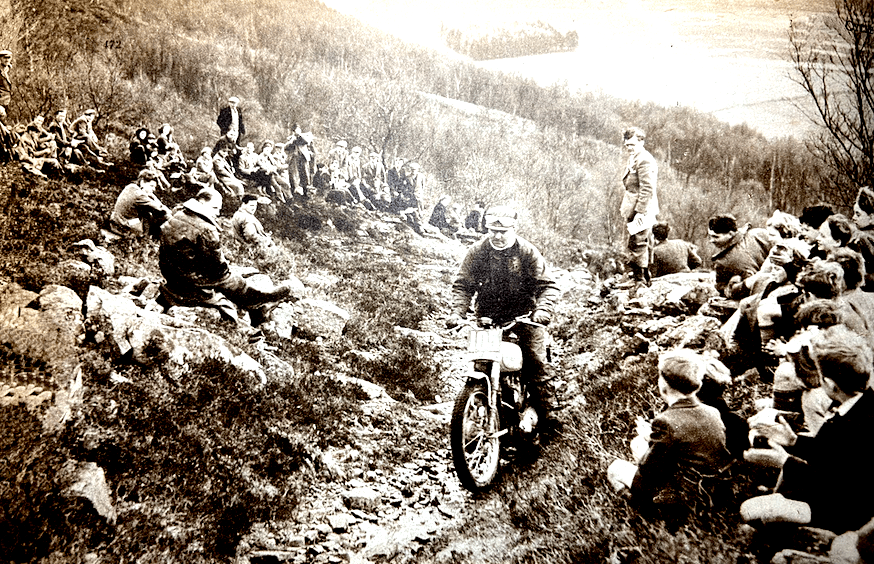

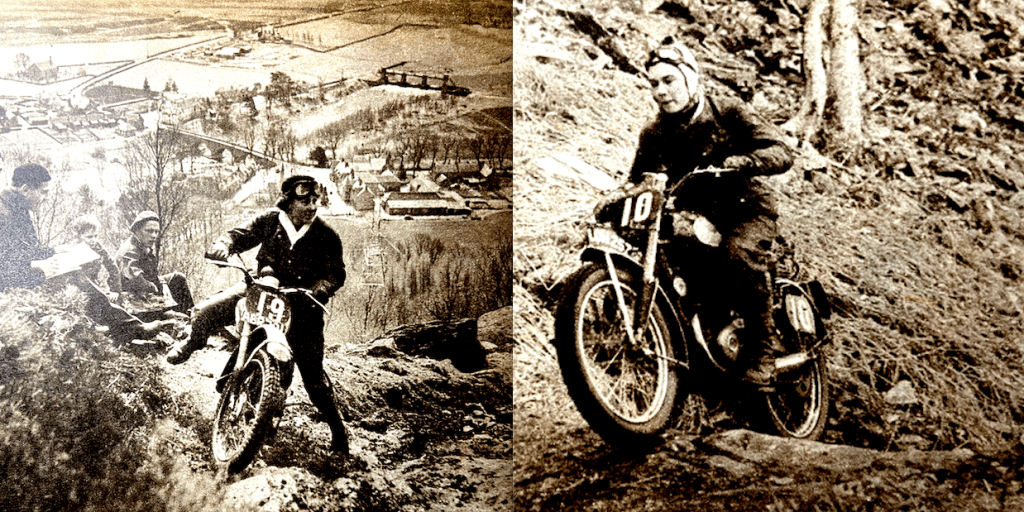

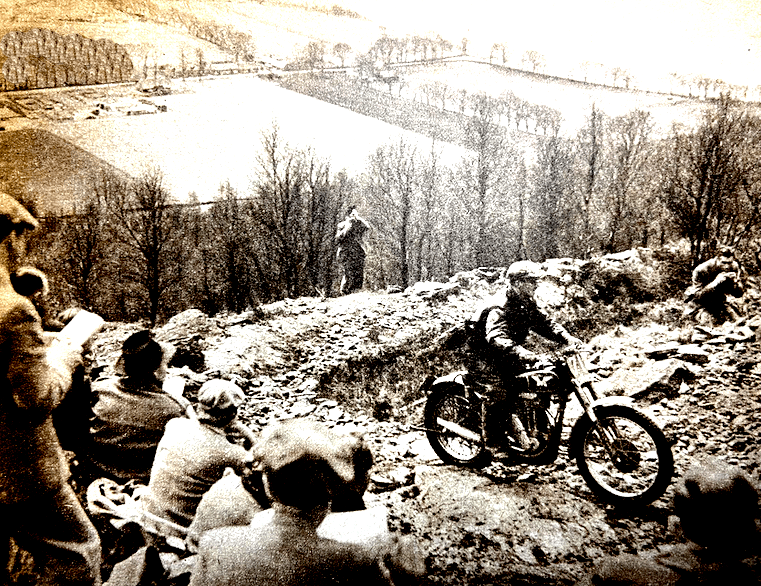

“HOW MANY YEARS since the mileage on a trade-supported one-day trial has run into three figures? And how often has more than two-thirds of the entry retired? And when, if ever, was a big event, such as this, won by the rider of a 197cc two-stroke? Assuredly the 1951 Travers Trophy Trial, held last Saturday on the very back-bone of the Pennine Chain between Alston and Stanhope, was an event in the finest possible tradition. But equally it was one of the most remarkable, not only because of the fact that 68 out of the 98 starters retired (owing largely to a snow blizzard which descended upon the wild Cumberland countryside at about 4.30pm), but also because Bill Lomas has now conclusively established that—even under the toughest conditions—a 197cc two-stroke can more than hold its own against what have hitherto been accepted as the finest trials machines in the world. More than a hint of this was provided by Jack Rotting and his Francis-Barnett in the ‘open’ Beggar’s Roost Trial at Easter, when he and Bob Ray (497 Ariel) returned the only clean sheets of the day. And now popular Bill Lomas, better known for his prowess in road racing, has clinched the deal in a manner so positive as to prove beyond doubt that the two-stroke in trials has well and truly arrived. By way of a change, this year’s Travers had its headquarters at the sleepy little village of St. John’s Chapel, in the picturesque Wear valley. The move from Alston was anything but popular with competitors. What was popular, however, was the complete absence of tape on any of the observed sections—confirming the opinion that the Newcastle &DMC need have recourse to no such ‘artificiality’ when running an event in what must surely be the finest natural trials country in England. Unfortunately the weather took a hand in proceedings, and towards the end of the afternoon there occurred a

blizzard of such magnitude that the later numbers were almost literally forced to retire. Those who did complete the course (two laps of 50 miles each) lost many marks on time, and, all in all, it must be admitted that the 1951 Travers was the toughest trial for a considerable number of years. The first observed section, Irreshope Burn, lay little more than a couple of miles from the start, and certainly gave no indication of the severe obstacles which were to follow. The five sections at Jackson’s Pastures, though, took a heavy toll of marks, the combination of mud, rocks and acute undulations proving more than a match for most competitors. Blagill, in contrast, caused considerably less havoc than of yore; its rocks seeming smaller than they have in the past. Even so, Hugh Viney came to a standstill with the front wheel of his 347cc AJS crabbed against the slimy right-hand bank, but he redeemed himself shortly afterwards by ascending the second half of Blagill (a muddy climb on the opposite side of the road) in masterly fashion—albeit a trifle too fast. GL Jackson (498 Matchless), who followed close behind the Maestro, was much slower but every bit as sure. Riders were arriving at Blagill very much out of numerical sequence—and very much out of breath, too! Explanation for this was to be found in the six-mile timed section, and in the alarming depth of the snowdrifts which existed there. This part of the course was more than 2,200ft above sea level, and the earlier numbers, such as PH Alves (498 Triumph), E Watkinson (348 BSA) and SB Manns (347 AJS) reported having dropped their machines into deep holes concealed by 4ft drifts. Tom Ellis almost lost his machine altogether, and Johnnie Brittain complained that the wheels of his Royal Enfield were completely clogged with snow. Five miles beyond Blagill came that old Travers favourite—the twisty, rocky, four-section climb known as Haggs Mine. James riders seemed particularly at home here, Miss Olga Kevelos getting through the first section without fault (in contrast to many mere males!) and Mrs Molly Briggs putting up quite the best show at the next obstacle. Bill Lomas completed all four sections with a confident ease which caused a spectator to remark: That looks like the winner,’ and how right he was! With a few yards of the main Alston-Stanhope road were two sections called Burn Bottom, crafty placing of the ‘Section Ends’ cards causing considerable trouble at both places. Among some really outstanding demonstrations of throttle control on the muddy second section, probably the finest was that of young John Giles (348 BSA), fresh from his Bemrose win of a week before. Came a fairly innocuous Racehead, then the

notorious Slit Mines—a slimy drop down a steep hillside, up the equally slimy opposite face of the valley, and, by way of a change, through some adversely cambered stone-pits at the top. First to arrive was PH Alves, whose performance on the ascent was pluperfect. Some 17 other competitors equalled Alves’ achievement here, but the tow-rope was much in demand. Miss Anne Newton, looking very trim and attractive in her dark red riding attire (to match her 197cc James), showed a fine sense of balance, and needed only an occasional dab to see her safely to the top of the hill. Wheelgrip was almost non-existent, however, and it was fortunate that this year’s Travers was a ‘solos only’ affair. There remained only the two muddy sections at Dike House, where, on the second circuit, conditions had deteriorated to such an extent that only Alves, Viney, Tye, Jackson, Lomas and Ray were clean. But there also remained the snow. And such snow! As darkness descended upon the wild Cumberland countryside the roads were rapidly becoming impassable, and competitors were scurrying away towards their various destinations, just as fast as their slithering wheels would carry them. A remarkable trial indeed, and one to be long remembered. RESULTS Travers Trophy (best performance): W Lomas (197 James), 9 marks lost (5 on performance, 4 on time). NUT Trophy (runner-up): CM Ray (497 Ariel), 12 marks lost (5 on performance, 7 on time). 150 Cup: KH Holloway (122 James), 143. 250 Cup: Not awarded. 350 Cup: NS Holmes (348 Royal Enfield), 28. 500 Cup: RB Young (490 Norton), 27. Manufacturers’ Team Prize: Royal Enfield (NS Holmes, GE Broadbent, JV Brittain), 134. Club Team Prize: Middlesbrough &DMC (RB Young, D Connett, W Young), 166.”

“IT IS EASY—in some directions, perhaps too easy—to draw conclusions from the figures for new registrations in 1950, now complete following the issue last week of the Ministry of Transport’s returns for the final month, December. Transcending everything, however, is the fact that in the 12 months no fewer than 131,476 vehicles in the motor cycle classes were registered for the first time. This compares with 89,255 for 1949, the record post-war year, and easily beats the boom year, 1927. Having regard to the industry’s magnificent export achievements over the past year, the figure is especially striking and proof indeed of the rapidly increasing popularity of motor cycling in Great Britain. What may surprise many is how the figure breaks down into engine sizes. Whereas in 1938, the last full pre-war year, the number of over-250cc motor cycles sold was five times greater than that of machines under 150cc, today the latter class reigns supreme—67,521 against 49,504. The ascendancy of the lightweight does not rest there, since 78,233 come within 250cc, the accepted limit for lightweights. The comparison is not entirely fair to the larger machines for two reasons. First, bicycles with motor attachments come within the under-150cc category; as yet, the county councils and the Ministry have not attempted to segregate this class of machine. Secondly, the main demand from oversea has been for motor cycles with medium-size or large engines, and therefore some of the larger-capacity models have reached the home market in only small numbers. It is estimated that in 1950, nearly half the under-150cc machines were bicycles with motor attachments. Allowing for this, the swing towards lightweights is still remarkable. Sidecar outfits number only 1 in 18 of all the new registrations, or roughly 1 in 14 if allowance be made for bicycles with motor attachments. This compares with 1 in 10 for 1938, but, once again, figures can mislead, because today there is a dearth of sidecars. However, what can be stated is that motor cycling was never more popular, and the 1929 record of 731,298 motor cycles registered is certain to be beaten this year.”

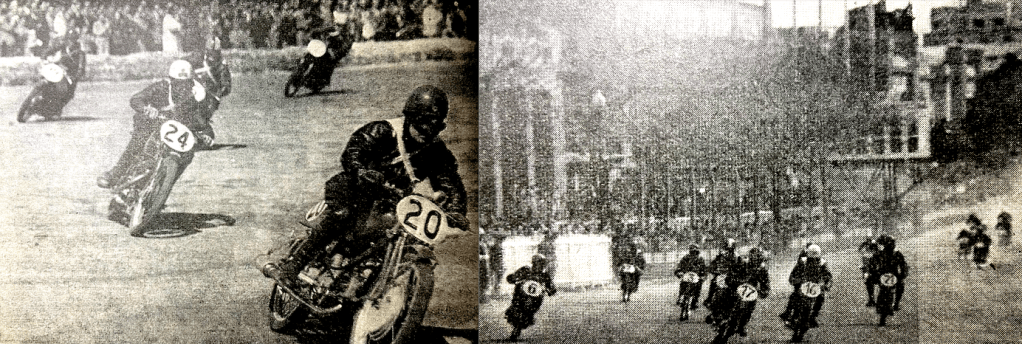

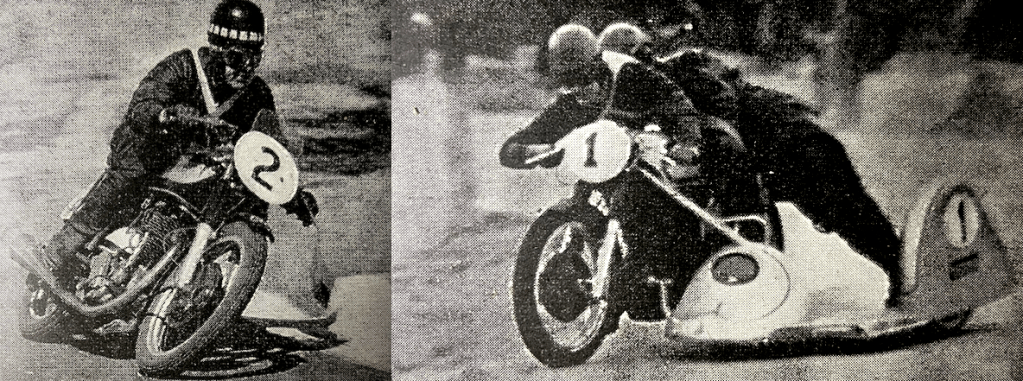

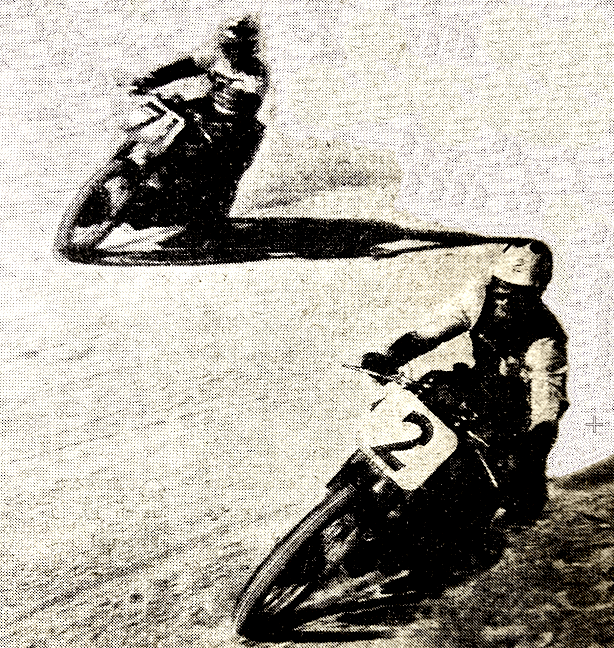

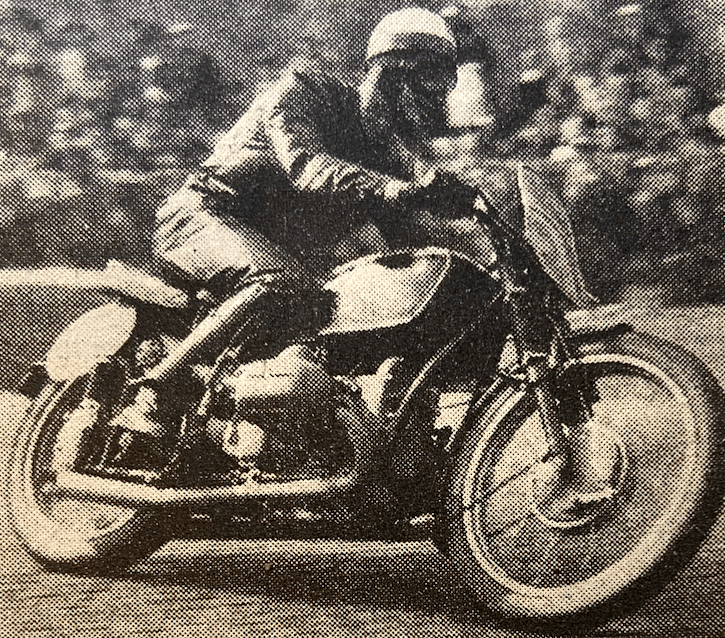

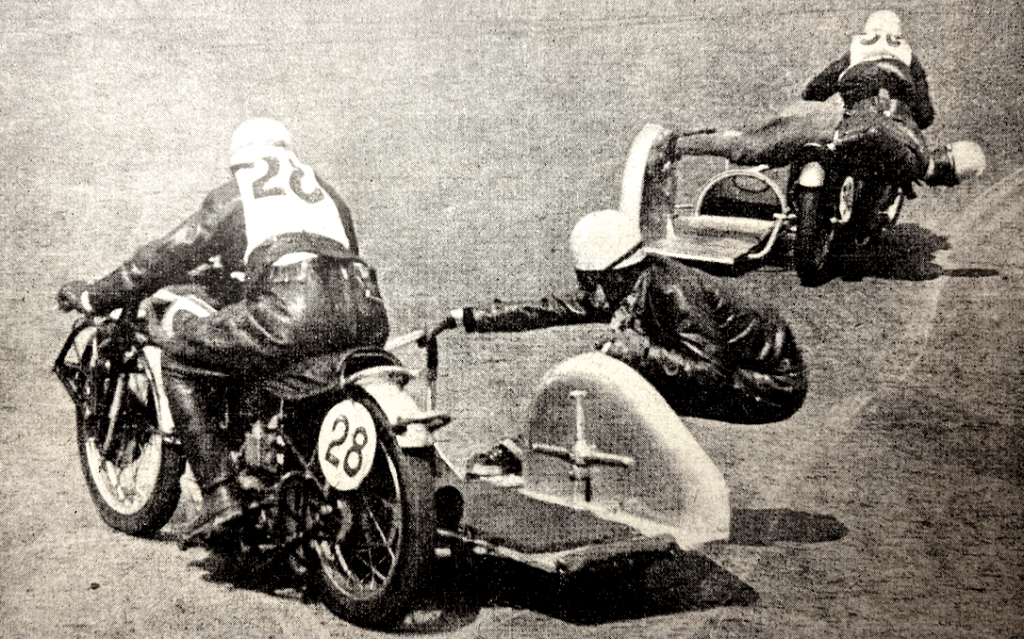

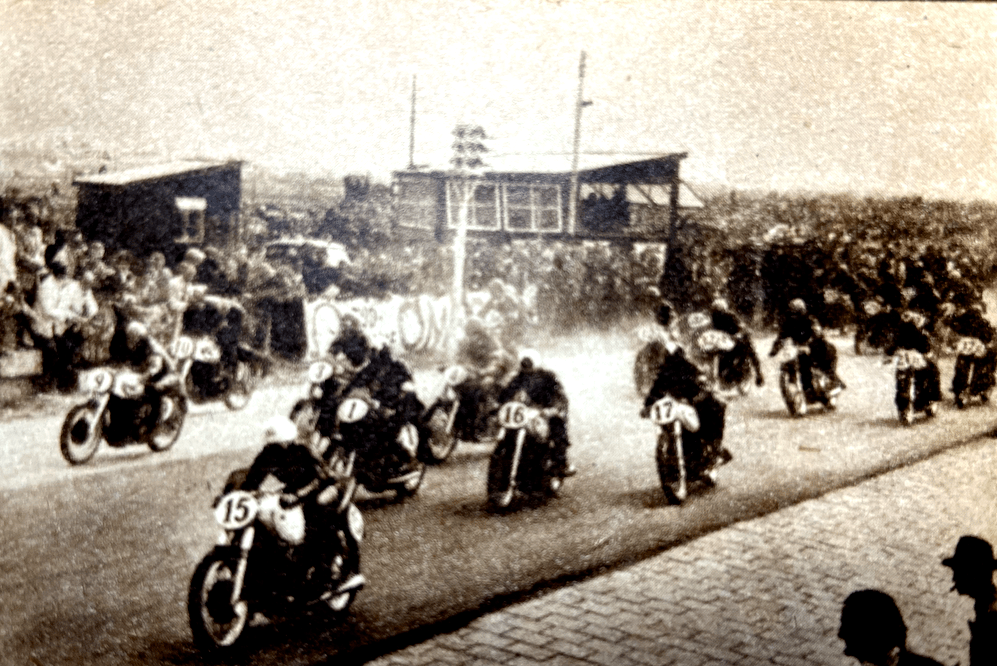

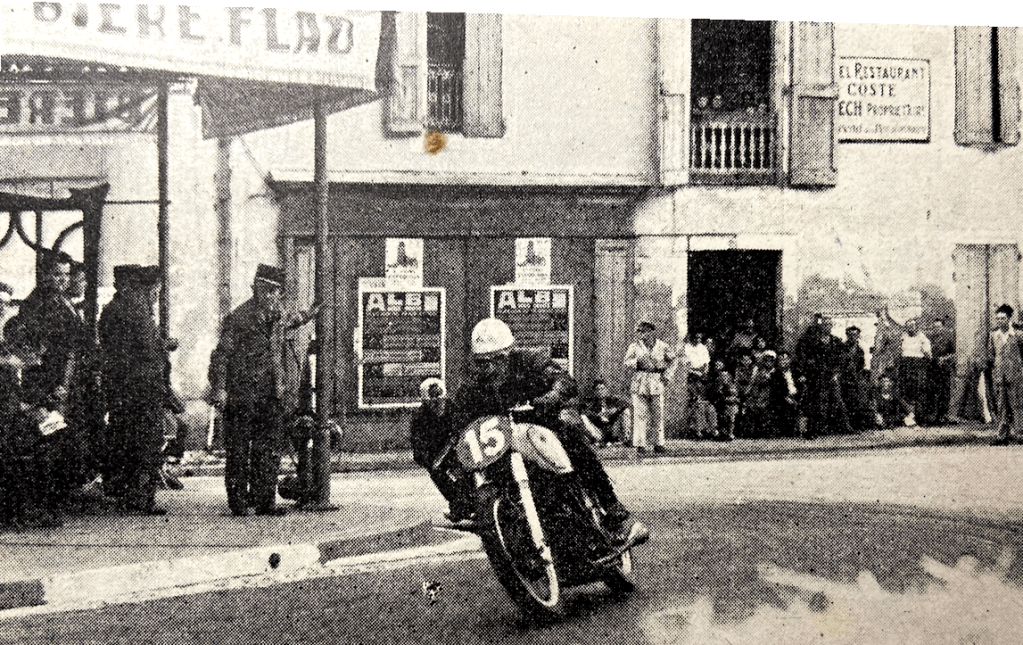

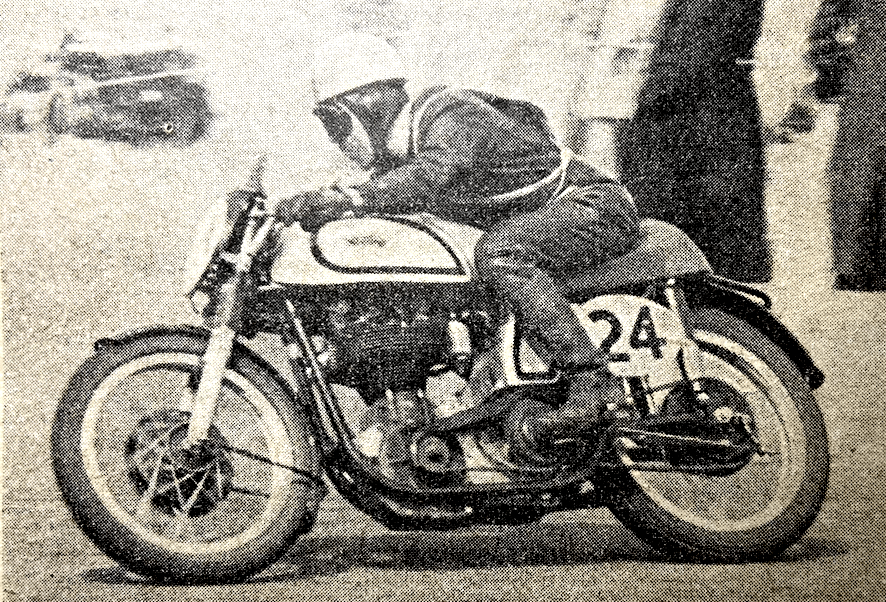

“THE SPANISH GRAND PRIX, held in Barcelona last week-end, proved an uninspiring start to the year’s classic road races. So many misfortunes beset machines and riders that, certainly in the 350 and 500cc classes, if not to the same extent in the 125cc and sidecar classes, it would be unwise to use the results as a basis for assessing future form. Outstandingly successful was TL Wood who won the Saturday’s 350cc class on his Velocette in convincing style and, riding a Norton on the Sunday, was second in the 500cc class to U Masetti (Gilera); Wood also rode extremely well on a Morini in Sunday’s 125cc class until, after being among the leaders for seven laps, he was forced to retire owing to engine trouble. In Saturday’s sidecar event, the winner with an easy mastery over the field was the redoubtable Eric Oliver, driving a 499cc Norton fitted with a Watsonian sidecar. The 125cc winner was Guido Leoni riding a Mondial. As the Spanish meeting was accorded classic status for 1951, the organisers, the Real Moto Club de Cataluna, extended the Montjuich Park circuit to slightly over six kilometres to comply with FIM regulations. The result was an uncommonly twisty course for which top gear could be employed only once for a very short period—this with 350s and 500s geared down as low as reasonably practicable. At 3.30 on Saturday afternoon, when the 350cc race was due to start, bright sunshine, only occasionally obscured by clouds, kept the temperature pleasingly warm for racing. Of the 21 competitors, W. Gerber (AJS), made the best start and flashed into the first bend a few yards ahead of TL Wood (Velocette). After, a 100-yard push W Beevers (AJS) stopped and was still fiddling when Wood reappeared with a clear 200-yard lead over Gerber. Amateur timing made Wood’s figure 3min 59sec, which suggested he meant business. There was no doubt about

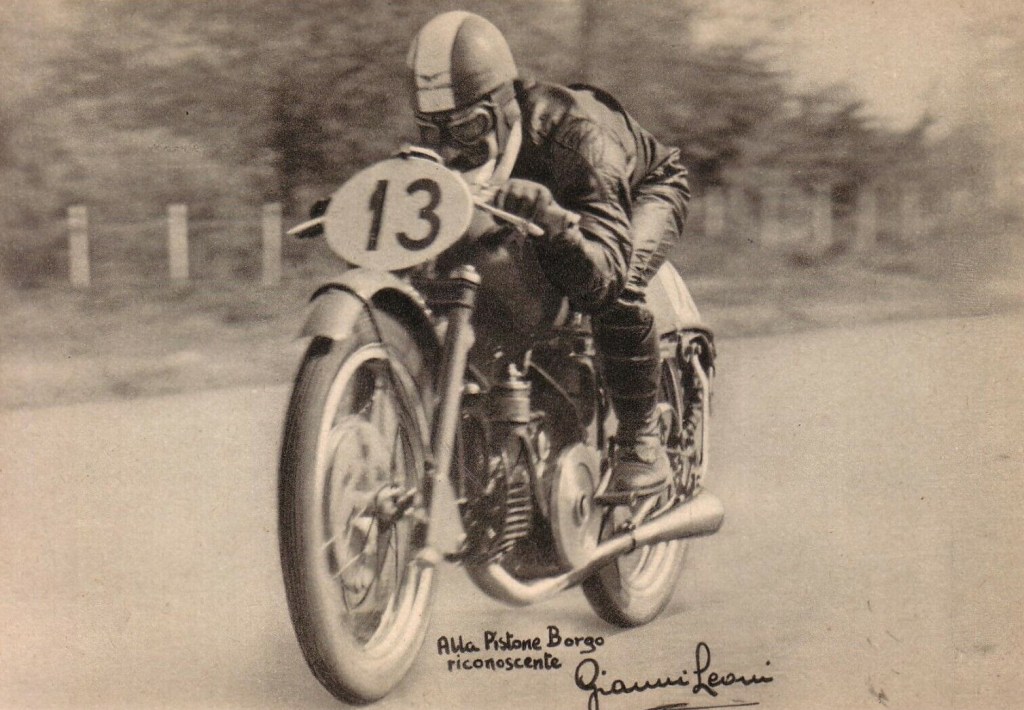

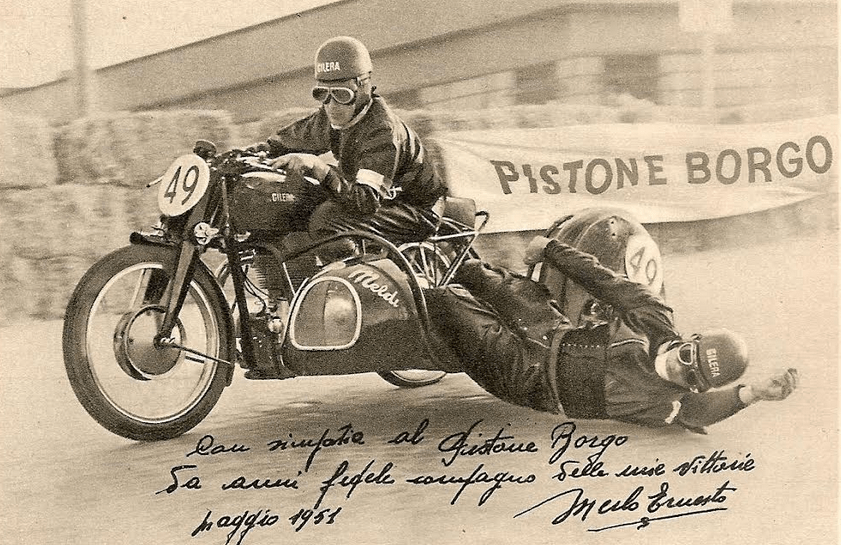

it on the second and third laps, both completed in 3min 47sec, which proved to be the fastest of the race. These two spirited laps gave Wood a half-minute advantage over the second man, Les Graham. Riding Reg Dearden’s Velocette, Graham was in second place from Lap 2 onward, and, with Wood, was pulling away from the field in spite of slight clutch-slip, which persisted for about eight laps. The race was over so far as the first two places were concerned. CW Petch, on what was said to be the first 1951 model 7R AJS to be raced, was holding a comfortable third place, and fourth, although unable to use third gear, was AL Parry (Velocette). Undoubtedly the most zestful riding was being put in by the Spaniard, F Aranda, on a 248cc Moto Guzzi. From 16th place on the first lap he cut through the field to displace Petch for third on Lap 9. But in the last five laps a broken valve spring slowed him and Petch managed to get ahead again. Retirements were heavy and included the two Germans, R Schnell and V Gablenz with their businesslike-looking Parillas. Wood’s victory completed a hat-trick—he trick—he had won the 350cc class of the Spanish GP in three consecutive years. 350cc Class—25 laps, 93 miles: 1, TL Wood (Velocette), 58 3mph; 2, RL Graham (Velocette). For the sidecar race, which followed the 350cc event on the Saturday, Eric Oliver was opposed by 11 competitors representing Austria, Belgium, Spain and Switzerland. The new FIM ruling meant that all machines were of 500cc capacity instead of 600cc as in the past. Oliver’s Norton had a works-type dohc engine in a TT-type frame with a telescopic front fork. Any doubts about how the outfit would handle were dispelled as soon as the first corner was turned. Oliver led in the screaming rush from the starting grid and swept into the corner noticeably faster than the rest. After three laps he had a 40-second lead over his usual challenger, E Frigerio, on the four-cylinder Gilera. A. Vervroegen, of Belgium, driving an FN, was third, but he was soon ousted by Albino Milani (Gilera single). Thereafter the race was a procession with Oliver increasing his advantage, although frequently lapping l0sec slower than he had managed in practice. Sidecar Class—17 laps, 63 miles: 1, ES Oliver (Norton), 50.2mph; 2, E Frigerio (Gilera); 3, A Milani (Gilera). Far more spectators gathered round the circuit for Sunday’s races. Many wore rain-coats in deference to ominous clouds drifting across the sky. But the expected rain did not come, and before noon conditions were again ideal. The 21 starters in the 125cc class included Mondial, Morini, MV, Montesa and Eysink teams, and provided the most keenly fought racing of the week-end. For the first five laps Guido Leoni (Mondial), C Ubbiali (Mondial), V Zanzi (Morini) and TL Wood ( Morini), riding in a 125cc race for the first time in his career, were separated only by yards. Leoni led for two laps; Wood for one; Ubbiali for two; then Leoni again for a lap; then Ubbiali for two more. Small-capacity machines can provide very tame racing in contrast with 350s and 500s on high-speed circuits. But round the serpentine Montjuich Park roads it was another matter. Wood’s popularity in Barcelona is boundless. A sigh of sympathy greeted his arrival at the pits with a sick engine (no compression) at the end of the seventh lap. Then Ubbiali dropped from a very close third to 30sec behind Zanzi and Leoni; his rear chain had jumped the sprockets and the price was the 30sec delay. Another mishap was to Denis Jenkinson (Montesa) who, when in 12th place, had to retire with a seized piston. R Alberti (Mondial) was fourth, but too far behind to rob Ubbiali of third place when the latter had his chain stop. For lap after lap Zanzi remained in front with Leoni about 50 yards away, and the thought arose that perhaps Morinis were now as fast as the world-champion

Mondials. Ubbiali was riding like a demon, trying most successfully to close the gap between himself and the leaders. Lap by lap he got closer. Climax came when, ceasing to play cat and mouse, Leoni headed Zanzi on the next-to-last lap. Ubbiali then had them both in sight, and made a final lap in the best time of the race to pass Zanzi and give Mondials a one-two win. 125cc Class—17 laps, 63 miles: 1, Guido Leoni (Mondial), 53.5mph; 2, C Ubbiali (Mondial); 3, V Zanzi (Morini); 4, R Alberti (Mondial); 5, J Soler Bulto (Montesa); 6, A Elizalde (Montesa). Misfortunes brought the 500cc class almost to the stage of farce. With Gilera, Moto Guzzi and MV factory teams in the field, the prospects of good racing were bright. But on the first bend after the start five or six of the 27 competitors were involved in a multiple crash. Fortunately, no more than bruises and scratches were suffered by riders, but at once the race became falsified. Alfredo Milani, riding a single-cylinder Gilera, gained the lead from N Pagani (Gilera four), S Geminiani (Moto Guzzi), C Bandirola (MV), U Masetti (Gilera four) and TL Wood (Norton). In 7th place, on an MV four, was Les Graham. Bandirola was in trouble with misfiring and made the first of many pit stops. Pagani and Gerniniani dropped back, while Graham and Wood gobbled up places. After seven laps, Milani had a 16-second lead over Masetti; then came Graham and Wood. Gear-box selector trouble put Graham out. Fergus Anderson (Moto Guzzi), one of those in the crash, called at his pit frequently and later retired. Other retirements removed half the starters and included the leader, Milani, who reported valve-gear bother. Masetti thus went into the lead, with Wood, handicapped by fading brakes, riding wonderfully in second place. But Wood was a minute or so behind Masetti, and third man, A Artesiani, was well out of the picture. Lap after monotonous lap the procession continued. Sixth man, E Vidal (Gilera single), walked his silent machine to the line to qualify as a finisher although nine laps short of the distance—a pathetic finish epitomising the week-end’s racing and in sharp contrast to the excellent organisation. 500cc Class—34 laps, 127 miles: 1, U Masetti (Gilera) 58.3mph; 2, TL Wood (Norton).

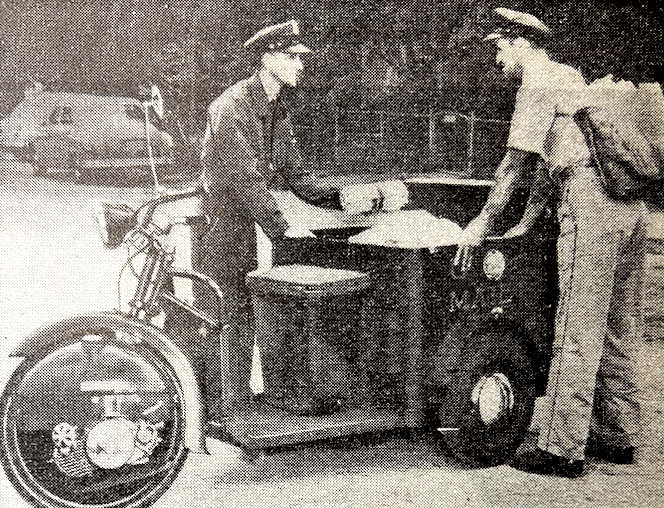

“EVERY NOW AND THEN I get an irate letter from some reader who claims to observe that the police treat pedestrians and cyclists with far more indulgence that they display towards motor cyclists. His generalisation is sweeping. It applies to the entire field of road crimes—lamps, Halt signs, turning to the right, and all the rest. I frankly admit that the village cop is lenient to low-income road-users. He is the sole representative of law and order in his wee community, by which he would rapidly be ostracised if he seized every chance of hauling his neighbours into court. As he relishes a quiet life as much as the rest of us, he seldom pounces on the local cyclists or peds. I have never noticed such lenience in the towns. On reading the letter I went down to the local court, where cyclist offenders that morning easily outnumbered motor cases. The cyclists were mostly on parade for ignoring Halt signs or riding without lamps.”—Ixion

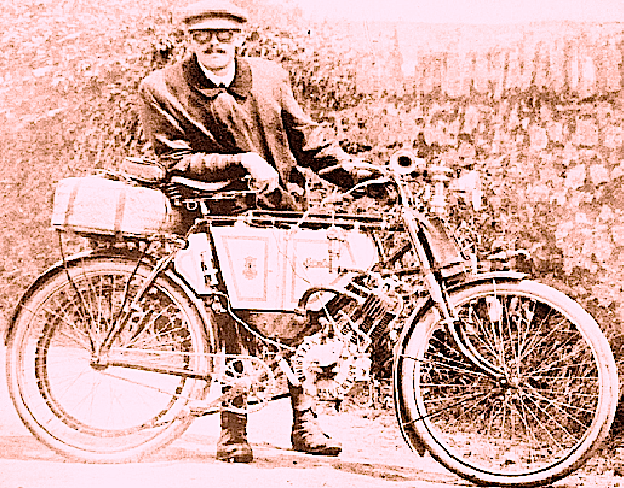

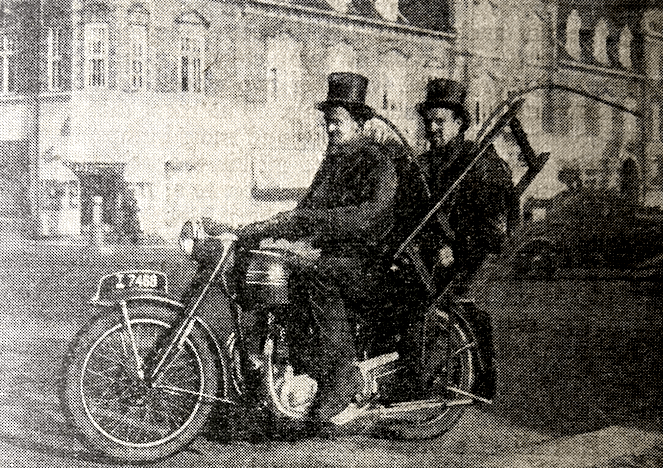

“BETWEEN 1901 AND 1905 I rode five Ormonde machines, equipped with Kelecom engines. But I have only just discovered that their frames were designed by PJ Goodman, of Veloce, Ltd. His employer was Arthur Goodwin, later famous with Vandervell. Goodman wanted to scrap the pedal gear and to build the Ormonde frame so low that the rider could drop his feet on the road while firmly seated in the saddle. Goodwin rejected this layout on the grounds of appearance He held that beauty depended upon the frame tubes being kept to a minimum number of angles. The top tube and chain-stays should be parallel to the ground line. The front down-tube and the backstays should be parallel with each other. I wonder who was responsible for the Ormonde experimental transmission? It employed pulleys with notched edges, conjoined with a belt carrying short, steel cross-pins on its upper side. The pins fitted into the notches and the leather between the pins bestowed flexibility. The designer lost heart when one of these belts broke and the tips of the cross-pins ripped hunks of meat out of his calf!”—Ixion

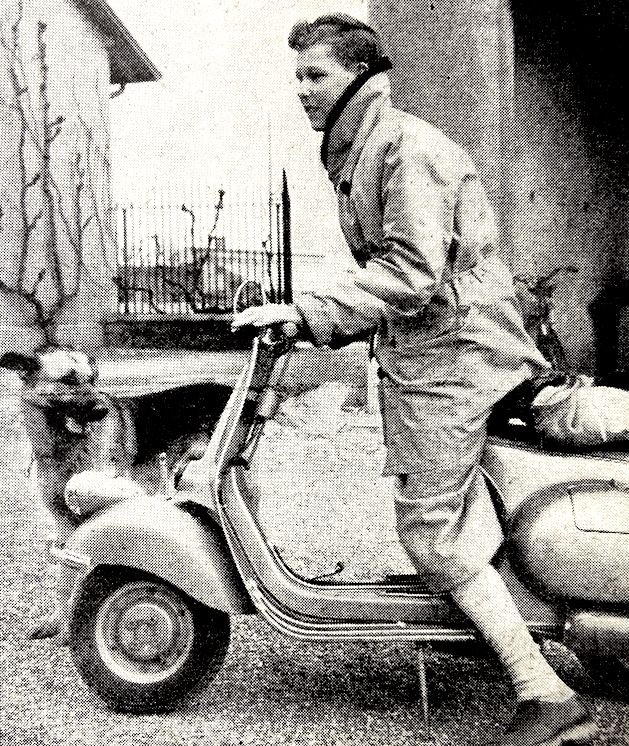

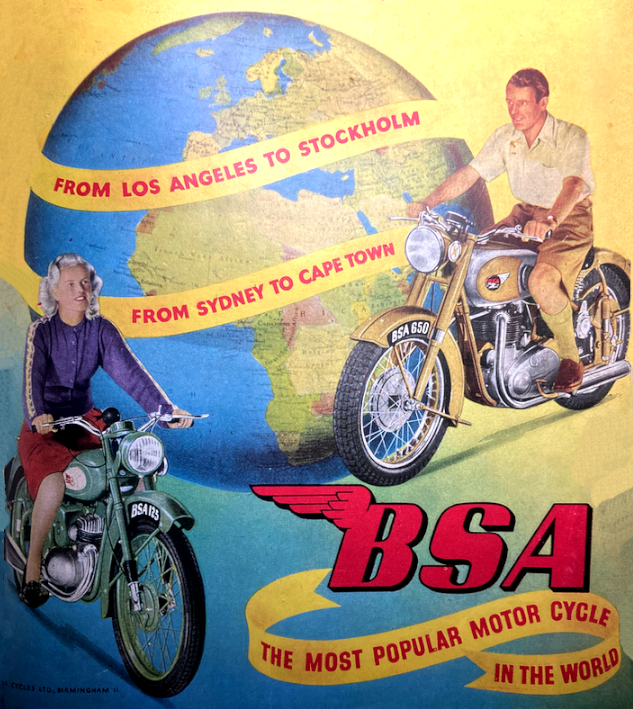

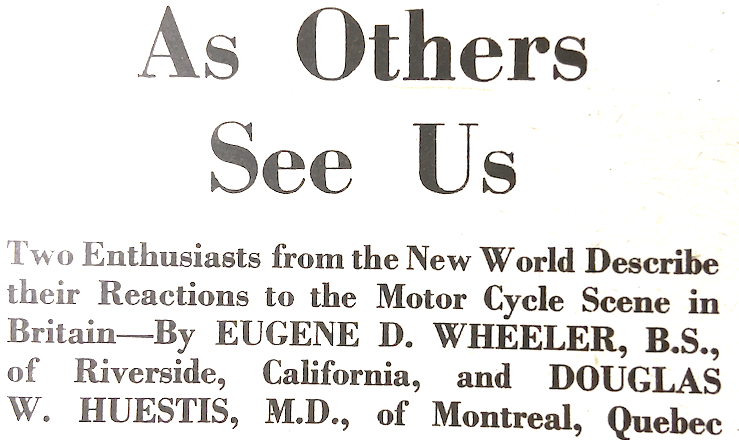

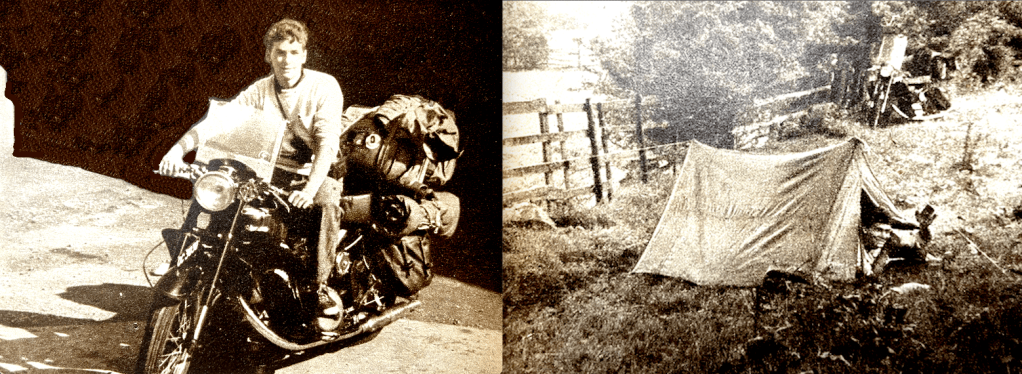

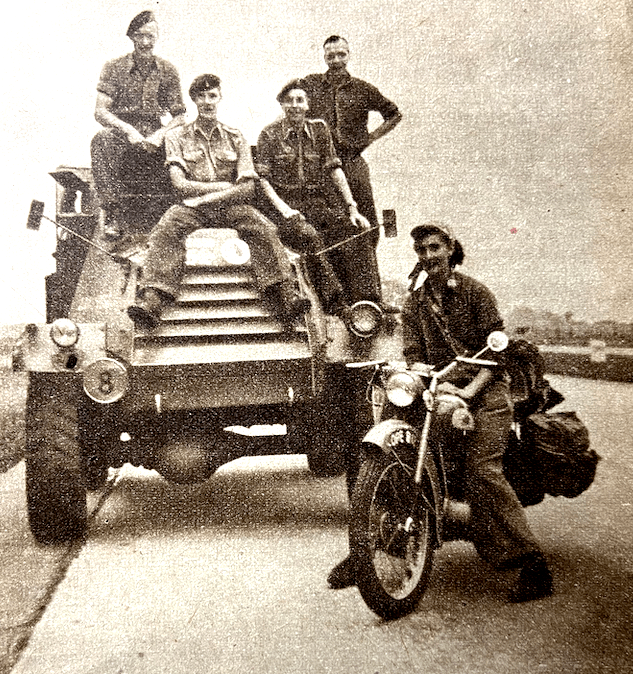

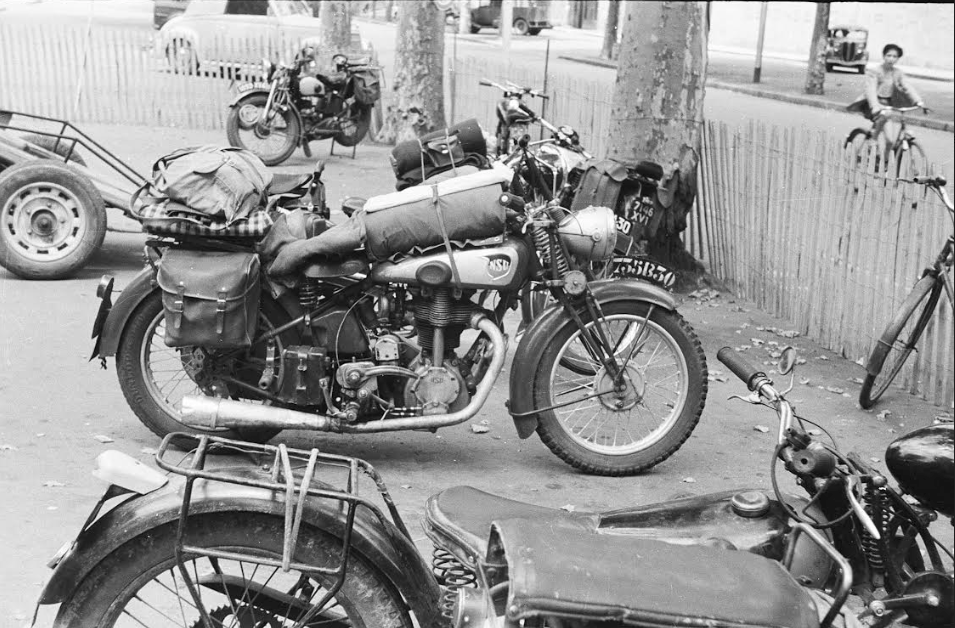

“IT IS QUITE IMPOSSIBLE for Britain to be a strange and unknown land to anyone who has been a reader of The Motor Cycle for any length of time. Nevertheless, we feel that an account of our impressions of motor cycling in these islands would be not only of interest to oversea readers who have not had our good fortune to visit in person, but could even attract the attention of those who view their homeland only with the jaded eye of a native. Similarly, we hope that comparisons made with motor cycling in America may be interesting to British readers. Please note that whenever we say ‘America’, we refer to both the United States and Canada, unless stated otherwise. Before we really get going, we want to pay official homage to those two paragons of British engineering skill, without which our visit to this country would be dull indeed. We refer, of course, to our respective steeds. The one, belonging to DH, is a three-year-old 600cc Panther, recently enriched by the addition of a Clamil spring wheel. The other is a 1950 500cc BSA springer. A good pair of friends to have! Naturally enough, arriving in England as we did after a lengthy stay in Scandinavia, it was a pleasure to be again surrounded by people speaking our own language, Of course, it is pressing the point a little to call it our own language, but, at any rate, we can understand and be understood more easily than on the Continent! We still tend to call petrol ‘gas’, and a gudgeon-pin a ‘wrist-pin’! In the same way, as we had come over from France, it was inevitable to drive off neatly down the right-hand side of the road, and feel indignation at other vehicles driving madly on the ‘wrong’ side This occurred in spite of our having lived and driven in Sweden for the past year, where left-hand drive is the rule. A very short while on the Continent had sufficed to get us back into our lifetime habits of right-hand driving. Generally, we haven’t found it much of a chore to change sides. One of our earliest impressions was of the excellent quality of the road surfacing. Sighs of relief were heaved, for our sit-upons sadly needed recuperation from the bruisings received on the atrocious pavé of Belgium and France. It is only fair to add that this fine impression only lasted until we got to London, where it was at once rudely shattered. However, subsequent wanderings about England have restored our original favourable opinion. There is an ordered and restful character to the green beauty of the English countryside. It is quite unlike anything we have seen before. The meandering nature of your roads is admirably suited to this type of landscape, and contributes greatly to the enjoyment of motor cycling. There is an intimate communion of road with countryside which is pleasant indeed. Here, the road is not something added lately, but has always been there, accommodating itself to hill and dale, growing up with and serving the land around it. There is nothing in all this which is incompatible with a good road surface, and the standard of surfacing is certainly high, even on secondary roads. One of us (DH) still breaks out in a cold sweat when he recalls negotiating the treacherous combination of pot-holes and shifting gravel on the back roads of the Province of Quebec (in his rigid-frame days, too!). Pleasant as it is to wander among the roads and villages of old England, the curving nature of the roads, plus the frequency of towns and villages (to say nothing of buses and trucks) combine to make life difficult for the man who wants to get from point A to point B with a minimum of fuss and bother. The great arterial highways and expressways now springing up in the United States and Canada, like the autobahnen of Germany, seem to be the solution to this, as are the by-passes on some highways in this country (such as on A3 from London to Portsmouth). Four-lane (or more) expressways can be made to look very beautiful, and certainly they can carry a large volume of traffic efficiently. It is possible to drive right into downtown New York on an expressway, paying a couple of small tolls on the way. Contrast this with the problem of getting in or out of central London! It is nice to observe that English highways are not disfigured by large advertising billboards. These are still all too common in some parts of America, where the approach to many a city is thus ruined. Of course, nothing in England or America can compare to the constant scream of day and night advertising assaulting the eyes of the traveller on an Italian autostrada. We find that road directional markings on main and secondary routes in rural areas, towns, and villages are excellent indeed, as they are generally in America (some parts of Canada fall down in this respect, however). However, on entering the big cities, especially London, one is at once plunged into a maze of un-named streets. The first time we arrived in London we got lost almost immediately, and this became a frequent occurrence thereafter. The finding of a given address is often a problem, even when one knows roughly where it is, as the authorities evidently consider it superfluous in the majority of cases to put up signs giving the name of the

street. When a signboard is put up, it is often cleverly blended with a few cigarette advertisements halfway up the side-of a nearby building, or even more ingeniously placed on side walk level, so that passing pedestrians and baby-carriages completely obscure it. In America, city street and direction signs are usually given much more often and in a clearer manner than in England. Even better are the cities of Sweden, where the names of both intersecting streets are given clearly at each of the intersection’s four corners. From the beginning we were both very favourably impressed with the general high standard of road manners and sense in English motorists and motor cyclists. Specifically, we think you are very conscientious in the giving of clear and correct hand signals. The automatic trafficators fitted to vehicles can sometimes be a menace. One of us has encountered two cases where the indicator on one side was put up, then the vehicle swung smartly in the other direction! In each case (Terry Saunders and Co, please note) the driver was a middle-aged woman. These instances are certainly not representative, though. In common with all visitors to this country, we think your police are the world’s finest. Their courtesy, good humour and willingness to help the stranger have become proverbial among travellers. May they ever remain thus. It was a pleasant discovery to note that the motor cyclist is treated with far more respect in England than in America. Here he is accepted as a regular and ordinary user of the road. This must be due largely to the fact that a much greater proportion of motor cycles here are utility vehicles, while in America the over-whelming majority are used for purely pleasure purposes. Furthermore, the immature behaviour of a small but active number of American motor cyclists has created an atmosphere of intolerance on the part of car drivers towards motor cyclists in general. In some extreme cases this can amount to a surprising bitterness. Among the elements contributing to this bad feeling is the uniquely American institution of the ‘motor cycle cowboy’. This is our personal label for the strange, glittering breed which infests the highways of the United States, Canada, and parts of Latin America. We hope that Texans and other Westerners won’t take offence, but we call the type the ‘cowboy’ because of the several resemblances to the Hollywood type of cowboy. Like this latter type, he also appeals mostly to the juvenile mentality. Furthermore, the frequent removal of the silencer from the machine makes the engine sound like the rattle of six-guns in a Grade ‘B’ Western film. Add to this the wide, jewelled and studded, leather ‘kidney-belt’ (also worn by the pillion passenger); beautifully-tooled and often high-heeled riding boots; coloured streamers from the twistgrip ends; fox-tail a-flutter in the breeze—and the picture is completed. But really not quite complete: the things we have omitted in the line of glittering and useless chrome fitments are really too numerous to mention. The gaudy appearance of this type of fellow, with his (often) noisy machine, inconsiderate and thoughtless driving methods, and generally childish and show-off behaviour, have been important factors in the adverse American attitude towards motor cycling. Though we do not know the exact figures, we are certain that they represent a minority of American motor cyclists, yet it is a sad fact that the damage they have caused to all of us is quite out of proportion to their numbers. After this small digression to the New World, we return to Merrie England, and launch off into that ever popular topic of conversation and object of abuse—the famous (or infamous) British weather. We come from two regions with widely differing climates, but we both combine in finding the English climate about the most treacherous we have ever encountered. Early on, we often made the silly mistake of accepting the weather at its existing face value. In other words, say on a beautiful cloudless Sunday morning (all too rare an event), we would gaily set out for a country ramble on our machines without deeming it necessary to carry rain equipment. This doubtless sounds incredibly foolish to you who live here, but we learned the hard way, by getting drenched to the skin a few times. The sheer perfidy of those rapid weather changes seems almost beyond belief. Of course, we understand that we have been here during a period of unparalleled bad weather (or so they tell us), but we give our impressions, anyway. Our experience of Scottish weather has been that it is quite dependable. You know it will rain! Naturally enough, the greater proportion of utility drivers here results in a correspondingly greater number of all-weather drivers. These bold fellows ride cheerfully on through rain, fog, sleet or snow, any of which would be enough to keep the majority of American drivers at home. Their ranks include some of the

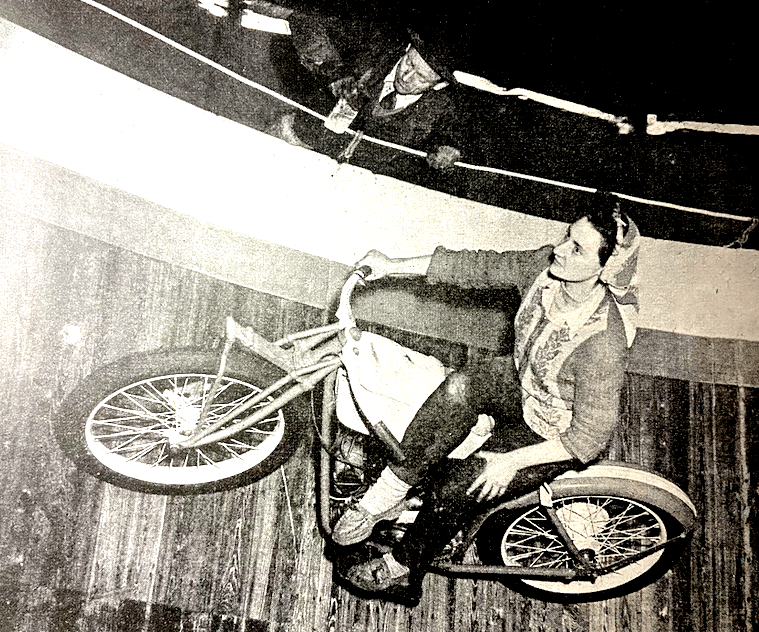

most unobtrusively expert and courteous drivers it has been our pleasure to encounter. They represent the backbone of British motor cycling, in our opinion, and no praise is too high for them. While we’re still in a complimentary mood, we’ll add a plug for the ‘greybeards’; those of middle years or older who for whatever reasons (economy or obstinacy!) still cling to their two- or three-wheelers for sport or transport. The same goes for family men, always a pleasant sight with the chair full of wife and kids. Both belong to a genus almost unknown. in America. They lend dignity and solidity to a hobby too often characterised by youthful abandon, and, furthermore, they keep of spark of youth alive in themselves. More power to them. Talking about family men brings up the whole subject of sidecars. A motor cycle and sidecar is an unusual sight in America, and a British-made outfit rare indeed. The only extensive use of sidecars is in police work. In the city of Montreal police motor cycles are 1,200cc Harley outfits. Neither of us has ever seen a family-type two-seater sidecar in America, which is really a pity, as an American big-twin is superlative for this type of work. It would be perhaps a little heavy on the gas (petrol!), but skill a good deal cheaper to run than a car. We are repeatedly being impressed by the knowledge and interest the English motor cyclist has in what goes on in the ‘innards’ of his machine. It is dangerous to generalise on such a point, but we feel that the ‘average Joe’ here is more mechanically knowledgeable than his counterpart on the other side. If he develops a fondness for an elderly machine (or can’t afford a new one) he will take the trouble to keep it on the road for an incredible length of time. A 20- or 25-year-old motor cycle in good road condition is not much of a rarity here, but is most unusual in America. On the other side of the ledger, the American enthusiast, undertaking trips of great length, as he frequently does, considers comfort and convenience more than his British cousin. Also, he is more gadget-minded. With almost 100% of buyers of new machines in America the first act is to fit an adequate pair of sturdy, leather pannier-bags (called ‘saddle-bags’). These are not regarded as an accessory, but as a necessity, and we would no more drive without them than we would consider buying a model with no mudguards. Windscreens are also popular, though not so universal as panniers. Safety-bars are perhaps a bit more common than here. At the time we left America (summer, 1949), legshields had not yet attained much popularity, but that may be changed by now. Many riders fit American-type ‘buddy-seats’ to British models. These are well made and ride quite well, though they tend to be more comfortable for the pillion-rider than for the driver. You have doubtless noticed that we have had very. little to say about the sporting aspects of motor cycling. The fact is that we are both essentially touring riders, not clubmen, and though we follow the sporting news with interest, we do not feel competent to give a fair comparison. Suffice it to say that trials and scramble-type events are quite popular with enthusiasts in America, while dirt-track (speedway) racing often attracts good-size sections of the non-motor cycling public as well. Lack of circuits has hindered any efforts to popularise road-racing. A pleasant and interesting habit, occurring throughout the United States and Canada, is that, whenever one motor cyclist encounters another on the road, a cheery wave of the hand is exchanged. When travelling two-up, this duty can be effectively delegated to the girl-friend on the pillion. This is a custom which helps to create an atmosphere of camaraderie among all American motor cyclists, an atmosphere to which not even the extreme cowboy-types previously mentioned are immune. Also contributing to this is the almost equally universal custom of stopping to see if a motor cyclist halted by the roadside needs any assistance. One of us recently had the annoying experience of a broken throttle-cable in Surrey at night. He was very pleased to find that he had only been stopped a few minutes when a sidecarrist drew up alongside and rendered valuable assistance. This is the kind of thing that makes our hobby the fine thing it is—in this or any other country. The writers realise that throughout this article they have been guilty of generalisation, with all its inherent dangers. We have tried to express, as honestly as possible, our impressions of motor cycling in Great Britain, and to couple these, wherever possible, with comparisons drawn between the hobby here and in America. It is obvious that not everyone will agree with our findings, in fact, we were often unable to come to agreement among ourselves. In conclusion, let us state that we have both wandered quite considerably on two wheels, both in Europe and America, and we think that Britain is the country for motor cycling. If any US or Canadian readers are thinking of visiting this country, we advise them by all means to bring their machines with them, if at all possible, and ‘have a go’. They won’t regret it. There are more miles of happy motor cycling in the small space of these islands than any stranger would believe possible.”

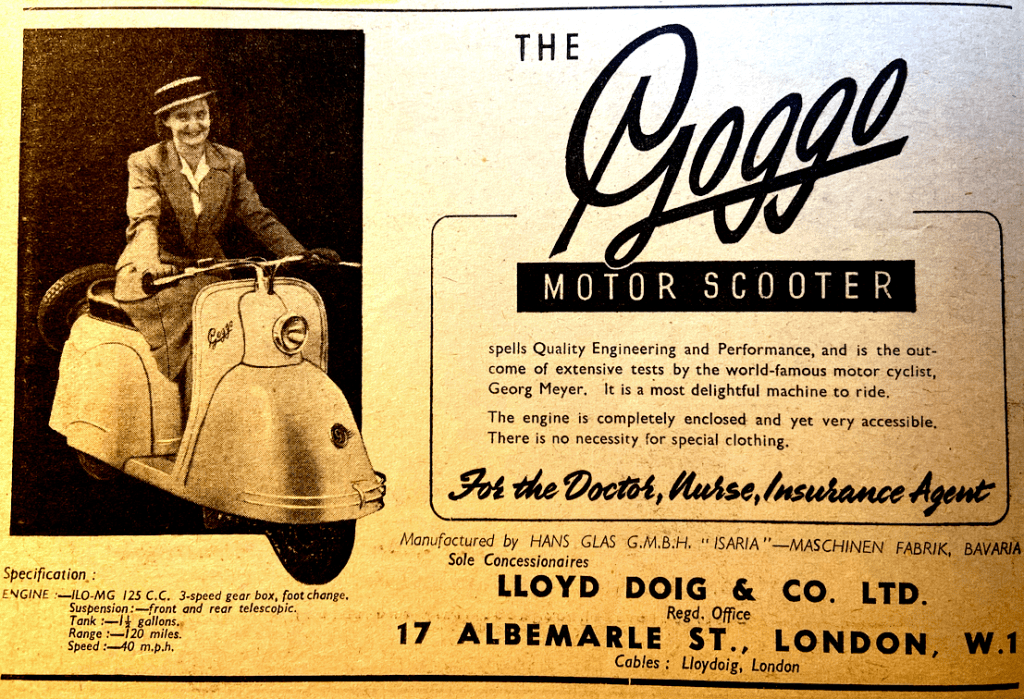

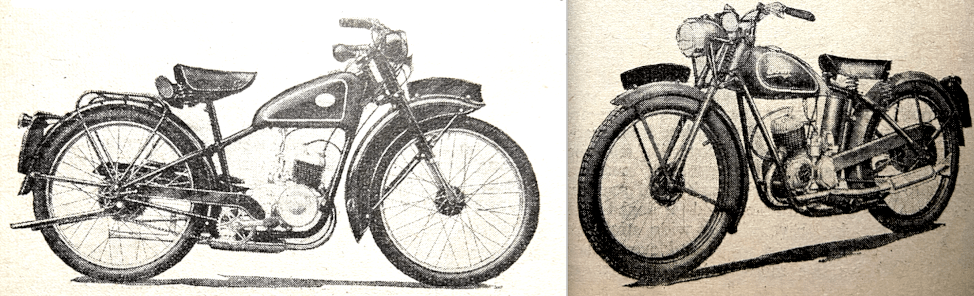

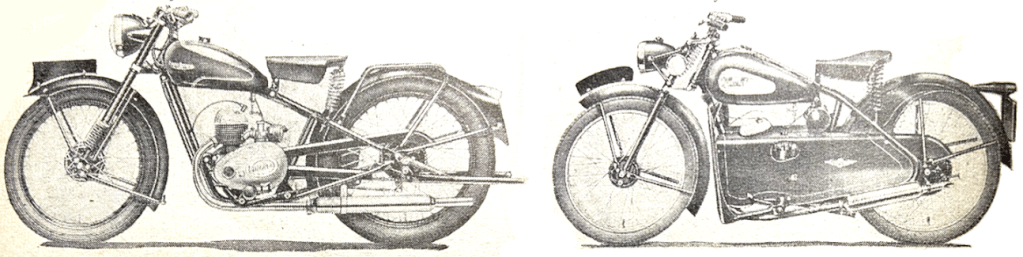

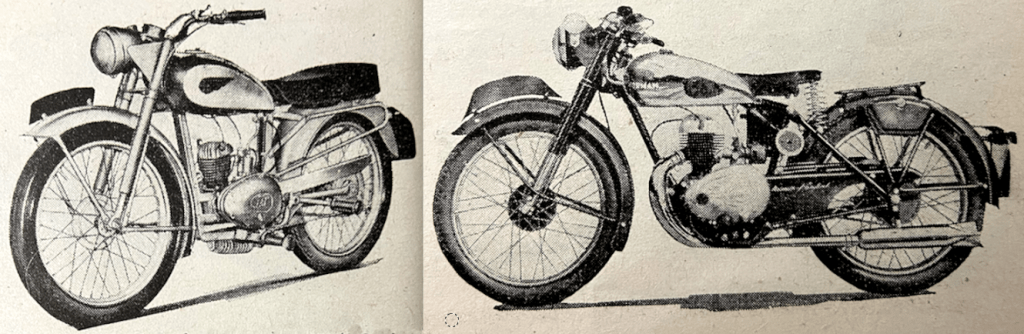

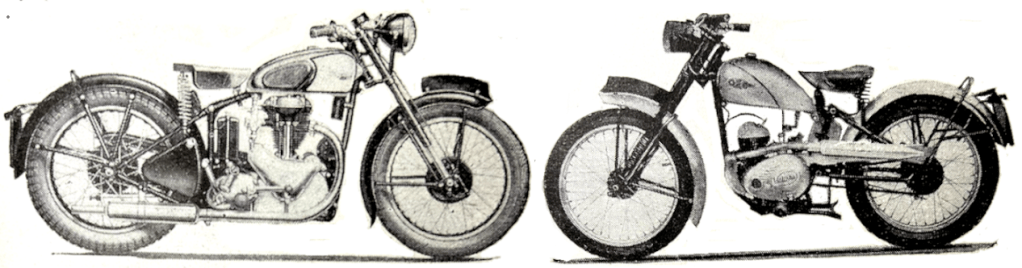

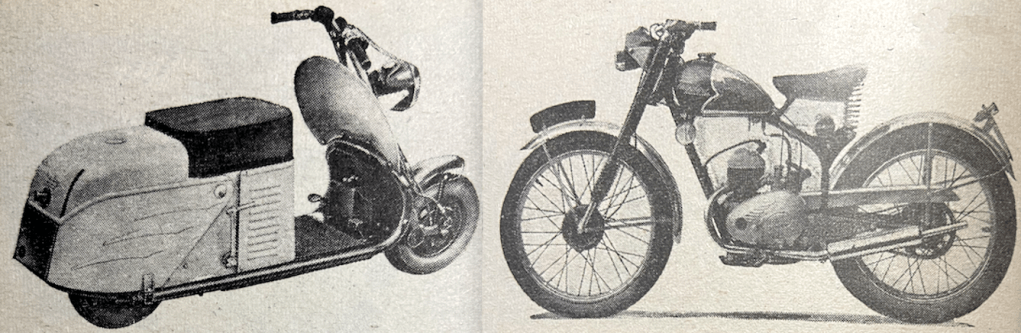

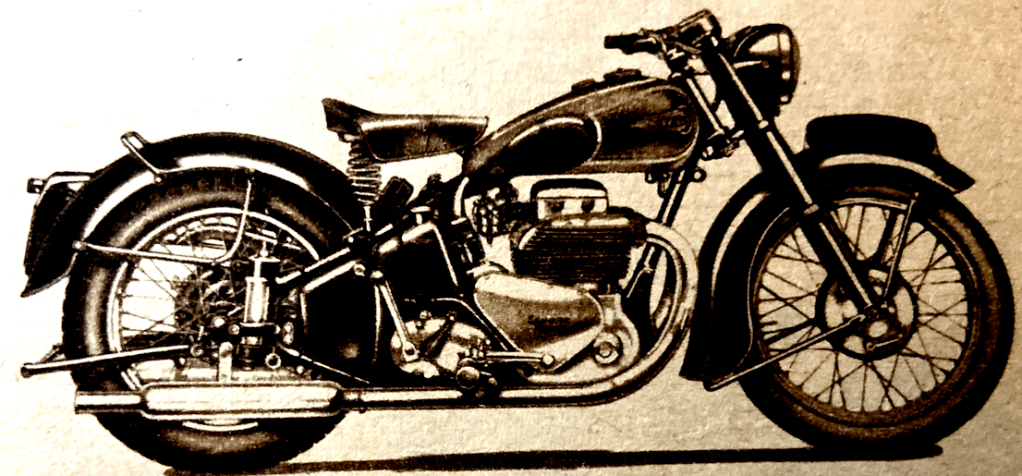

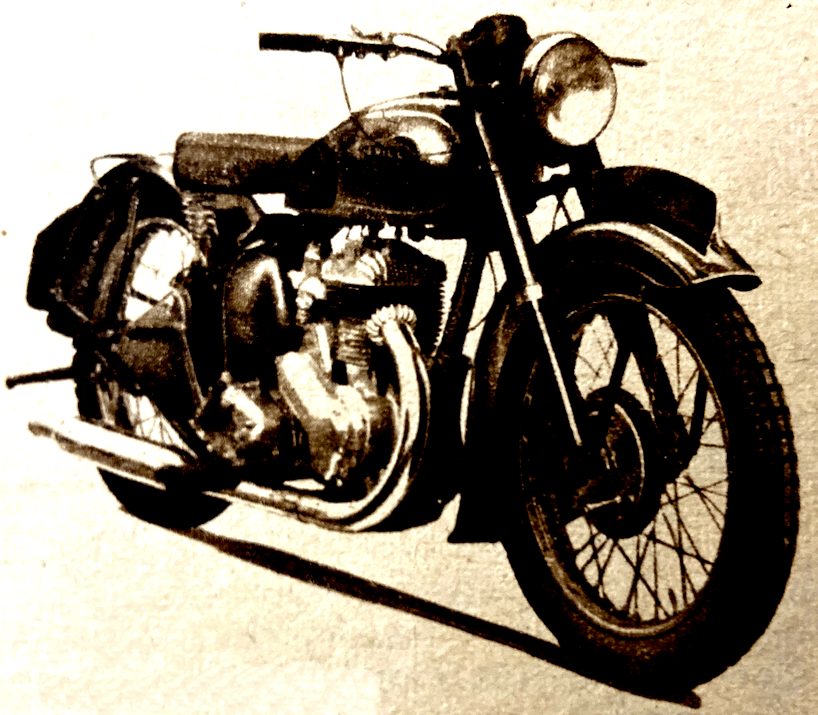

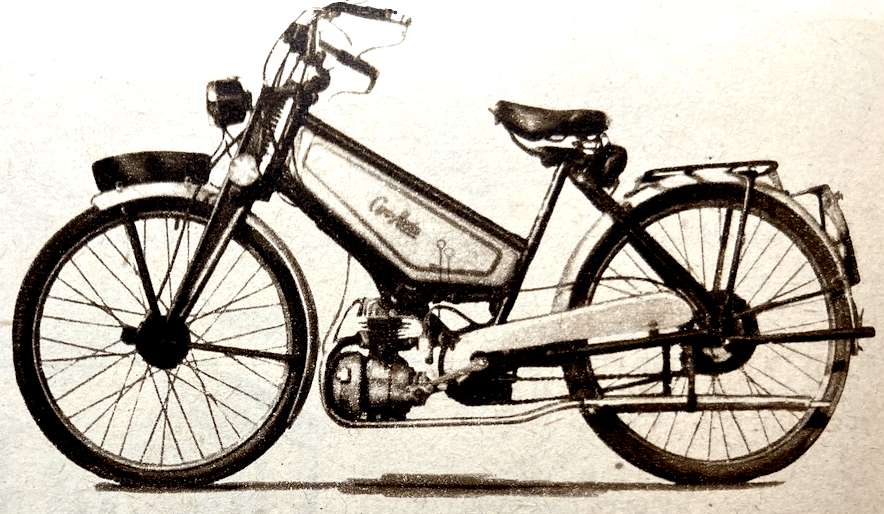

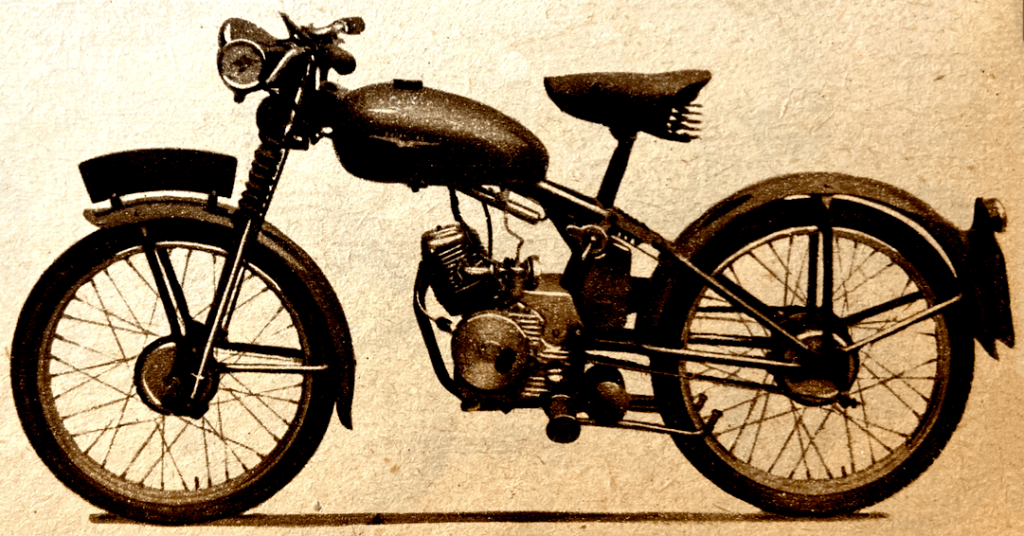

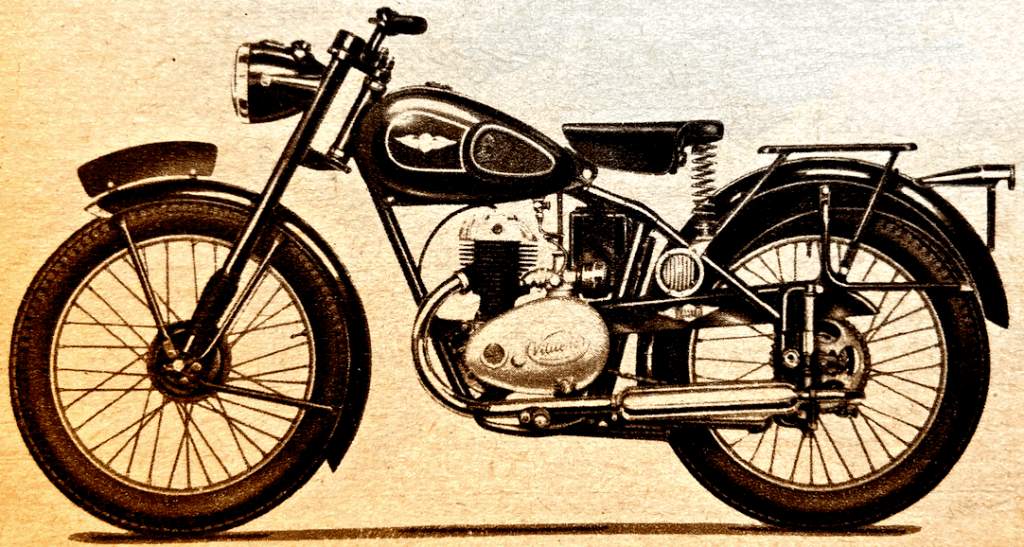

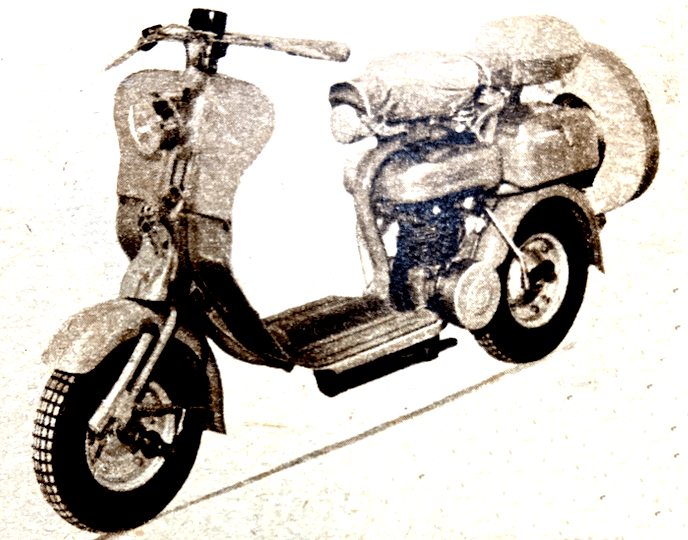

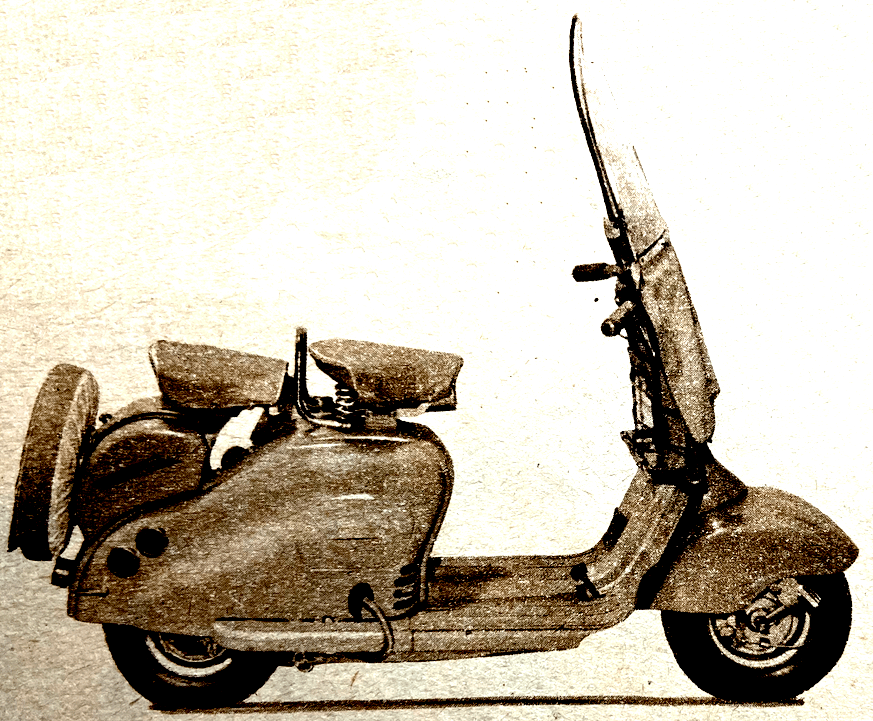

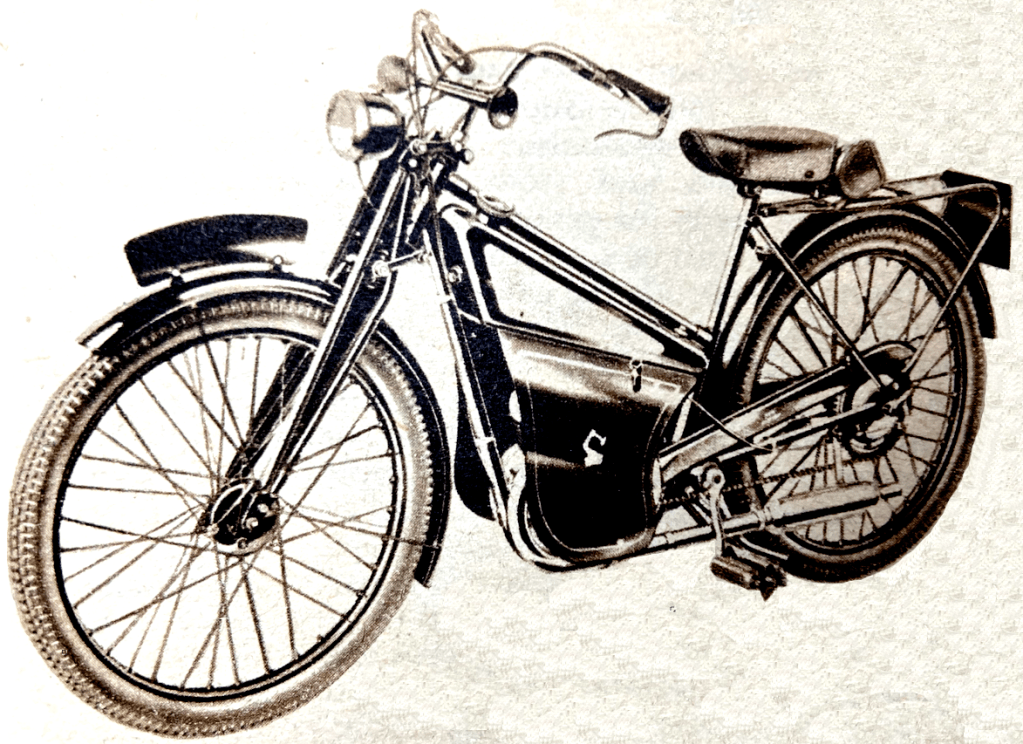

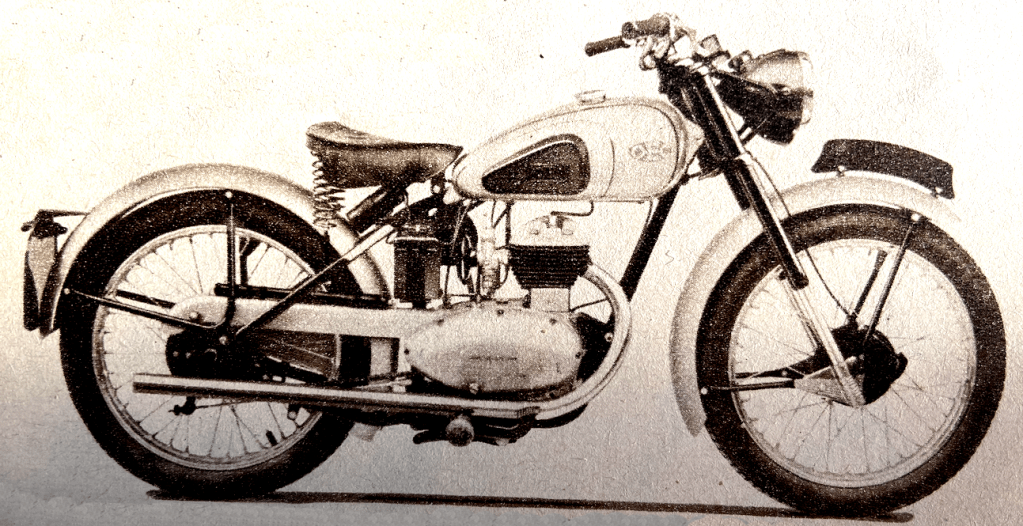

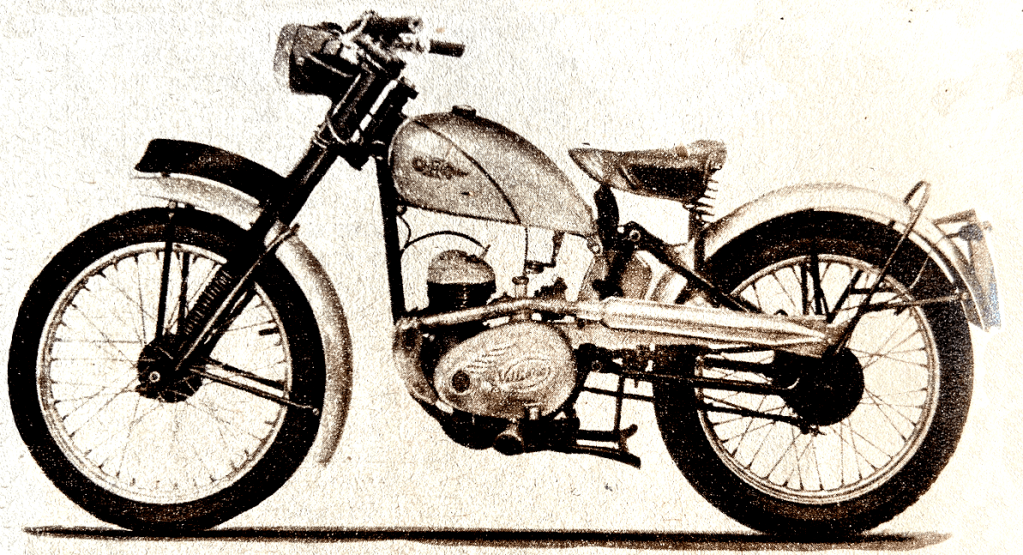

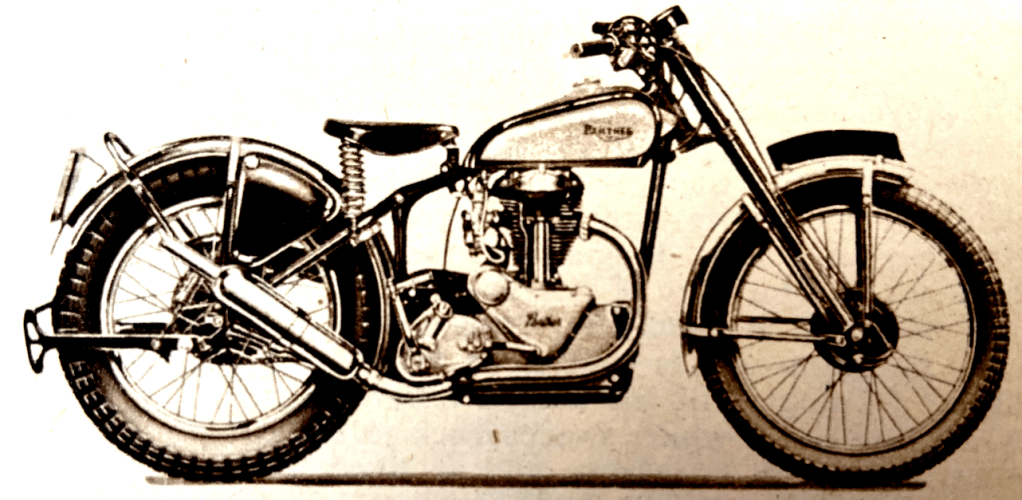

“AS PRODUCTION FIGURES and international exhibitions clearly indicate, the world trend is towards small-capacity machines. Even in Great Britain, the traditional fountain of medium- and larger-capacity machines, more and more attention is being given to lightweight motor cycles and to bicycle-propulsion units. The reason for this trend is two-fold. Throughout the world the cost of living is rising and economy is to the forefront of everyday thinking. Hence, the economical lightweight appeals to the rider who, by the use of his machine, can cut down on his former travelling expenses by public transport, or to the rider who finds a larger machine strains his resources. But there is another aspect; in recent years, the improvement in efficiency and reliability of small-capacity machines has been such that their usefulnesS, and therefore their appeal, is notably broadened. Even motor-assisted cycles, though not designed for such work, have been tested by very lengthy trips such as nearly 2,000 miles in 12 days; and many owners who fitted micro-motors in the first place simply to ease the labour of pedalling to and from work have subsequently realised the full possibilities of powered cycling and become enthusiastic tourists at week-ends. It is not only in the touring sphere that the lightweight is gaining ground. More and more small-capacity machines are appearing in competitive events. An indication is that in the first British national trial of this year the entry list of 138 solos included 28 under-250cc machines; in the Victory Trial, the solo entry of 133 included 15 machines of 125cc, 14 of 200cc and 10 of 250cc. Another pointer is that for the first time in its long history, a class for 125cc machines is included in the programme for the next Isle of Man TT meeting. There are around 100 British models in the under-250cc category of motor cycles, scooters, autocycles and bicycle-propulsion units. Motor cycle capacities from which to choose are of 250cc, 200cc, 125cc and 100cc; the autocycles are of 100cc, and the cyclemotor units from 50cc down to 25cc. No country in the world offers a wider or finer range from which to choose.”

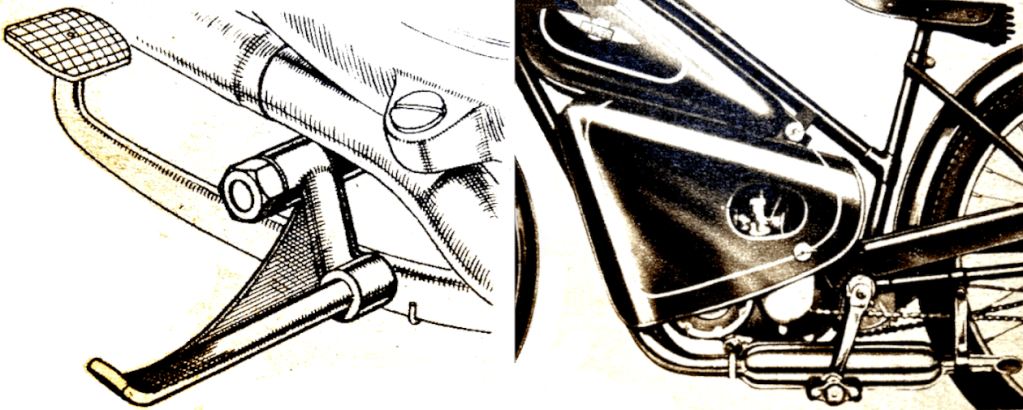

“THE TWO ABJ MODELS listed are almost identical except that the autocycle is fitted with the 98c. Villiers Mark 2F single-speed engine and with pedalling gear, whereas the motor cycle has the 98cc Mark 1F power unit which incorporates a two-speed gear with handle-bar control. Specification details are a loop-type tubular frame, a telescopic fork, deeply valanced front mudguard, 4in-diameter brakes and 2.25x21in tyres. The motor cycle is fitted with rectifier-battery lighting. Though there is a basic similarity between the four Ambassador models—all have the 197cc Villiers engine-gear unit—the appeal of the range is unusually wide. At one end of the scale, the Supreme model introduced for 1951 is a true luxury machine, and at the other end the well-proved Popular model is outstanding value for money. With its very neat telescopic front fork and plunger-type rear suspension giving 2½in deflection, the Supreme appeals to the

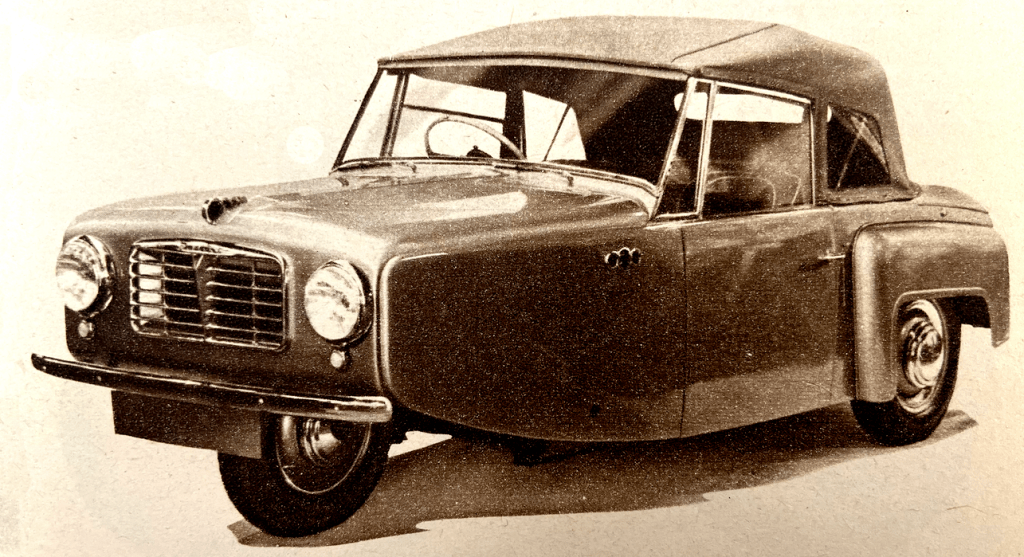

rider who has connoisseur inclinations. Equipment includes lighting with rectifier and battery, a deeply valenced rear mudguard and a specially attractive finish. The colour is light grey and the knee-grips, footrest rubbers, handlebar grips, brake-pedal and Vynide saddle cover match this colour. A telescopic fork is fitted to the Embassy and a Webb link fork with pressed-steel blades is employed on the Courier. The keen-priced Popular is a business-like model with the fork and frame of the Courier, and direct lighting. Yet another machine to be fitted with the lively 98cc two-speed Villiers Mark 1F engine is the BAC Lilliput. Welding is employed for the joints of the loop-type frame and the fork is of the telescopic pattern. As the name implies, the machine is of small dimensions with a 45in wheelbase and 25½in saddle height; it is also light in weight—the figure quoted by the manufacturers is 891b. Finish is in polychromatic bronze. One of the main attractions of the unusual construction employed for Bond machines is that it results in weight saving. The smaller model fitted with the 98cc Villiers two-speed unit scales, according to the manufacturers, no more than 961b, and the larger machine, which has the JAP 125cc two-stroke engine with three-speed gear box, weighs 100lb. The unorthodox frame takes the form of a light-alloy, stressed-skin backbone with a tubular loop supporting the engine unit. Both models have telescopic front forks, 4in-diameter brakes, 4in-section tyres and 1½-gallon fuel tanks. The Bown Autocycle is notable for its lavish specification, which includes a very sturdy duplex cradle frame; a spring fork with

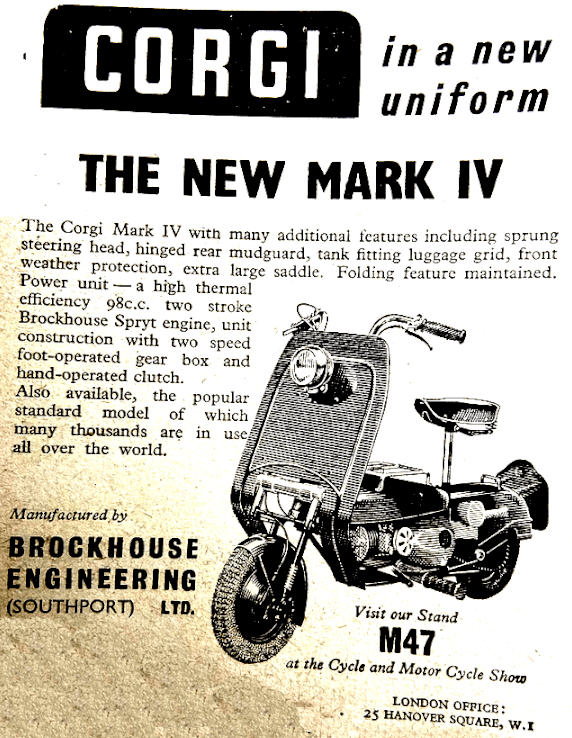

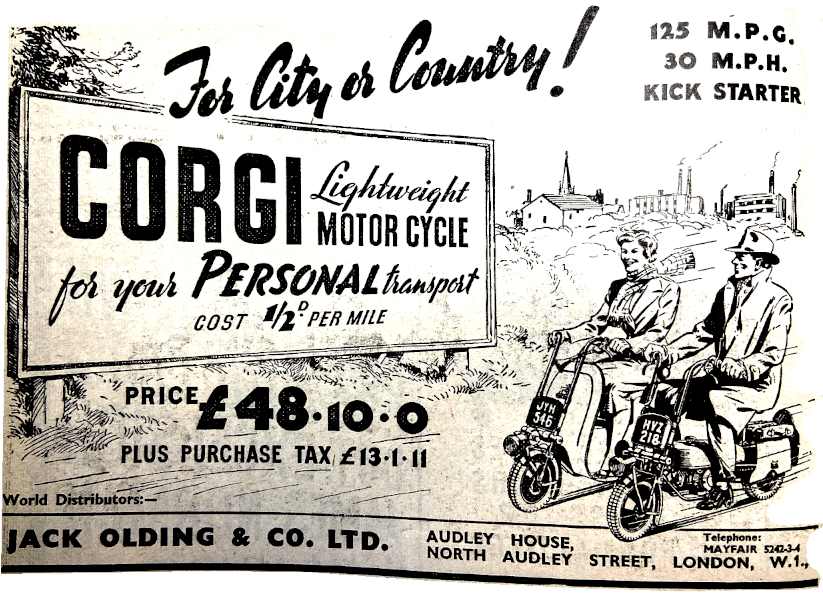

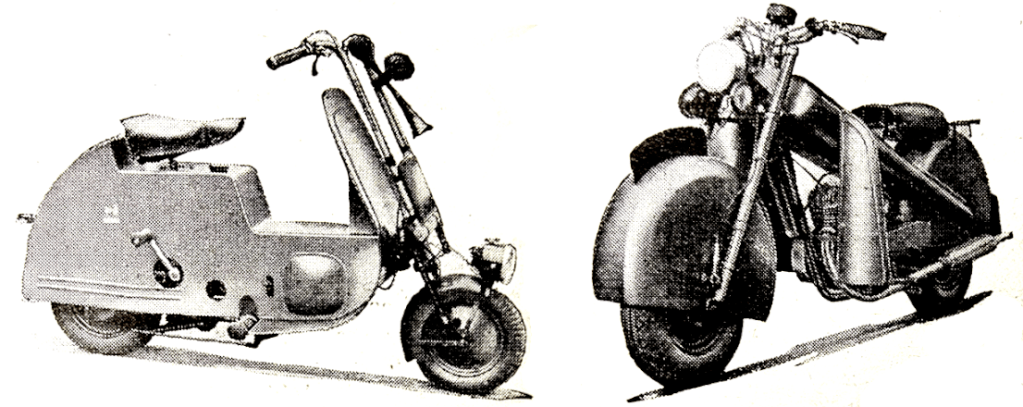

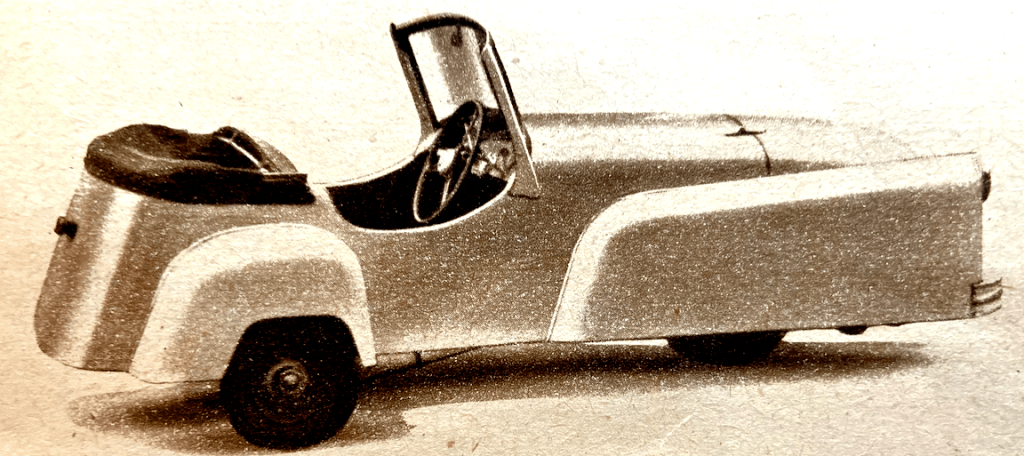

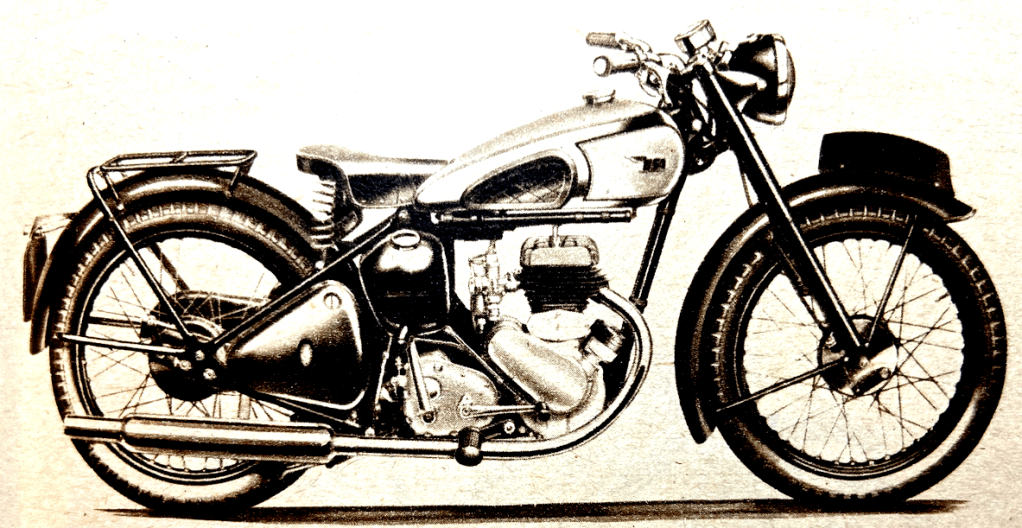

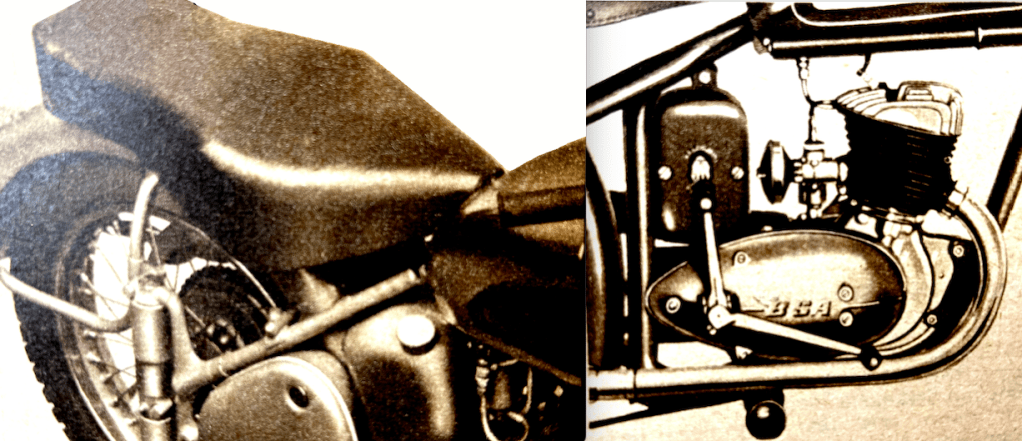

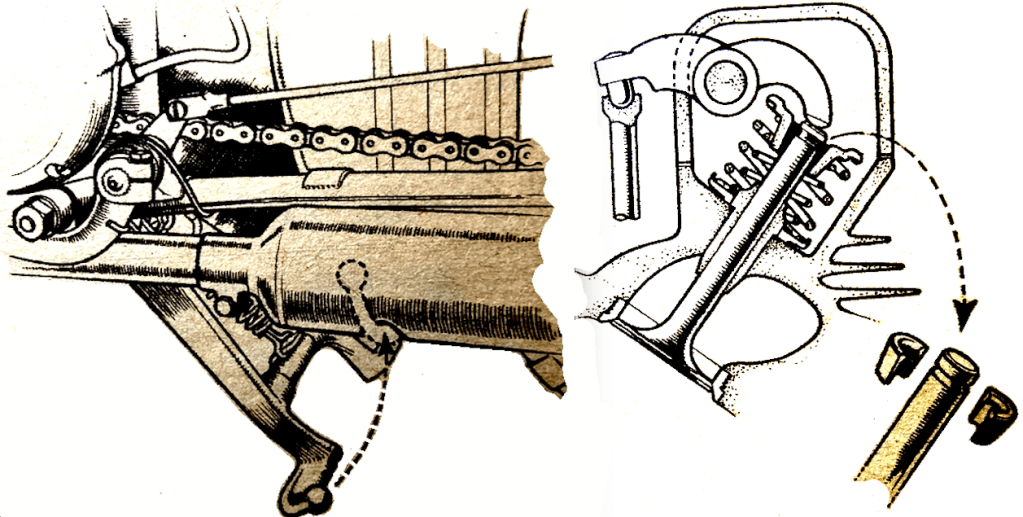

pressed-steel blades; elegant side-shields for the engine, and deep shields over both the pedalling-gear chain and the final-drive chain; a 1½-gallon petroil tank; rubber-cushion pedals and ample saddle; and a large tubular carrier. The engine is the 98cc Villiers. A duplex cradle frame is also employed for the Bown 98cc two-speed motor cycle which, it is expected, will be in production shortly. In the very wide BSA range, the D and C models come within the category of lightweights and give the choice of a two-stroke and side-valve and overhead-valve four-strokes. The widely known name of the D models is ‘Bantam’. Immediate success greeted this machine when it was introduced in 1948. The two-stroke engine with three-speed gear box in unit is highly efficient; it gives a very lively performance and is light on petrol. Positive-stop foot-gear change is fitted. For an additional £5 over the price of the Standard model (£6 7s with Purchase tax) plunger-type rear springing may be obtained. There is also a Competition Bantam with an appropriate specification. C models are 249cc four-strokes. The C10 has a side-valve engine with dry-sump lubrication, coil ignition and three-speed gear box. Similar, except for the obvious differences arising from overhead valves, is the Cll. The same type of neat, diamond frame and telescopic fork is employed for both models and for the C11 de luxe which differs from the C11 standard in finish. All C models may be obtained with a four-speed gear box and with plunger-type rear springing. A point of interest is that the C10 is the only 250cc side-valve machine at present available on the British market. Basically the 98cc two-stroke, single-speed Corgi remains unchanged as a runabout of special appeal because

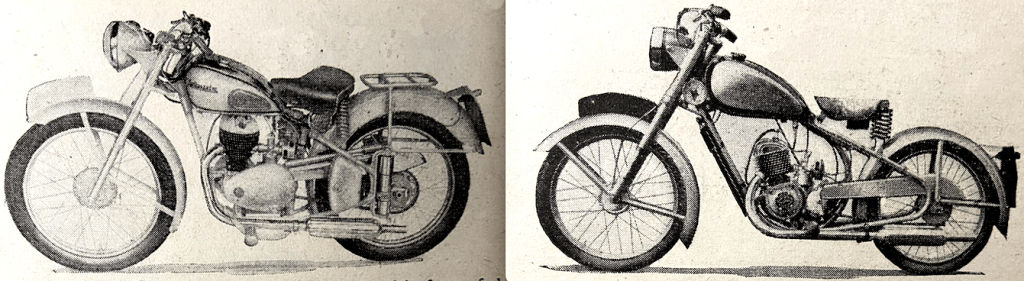

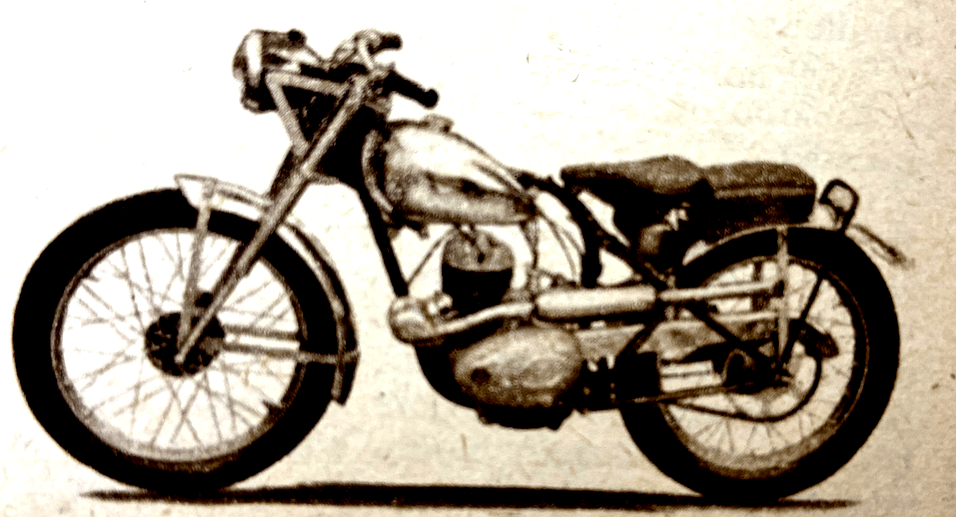

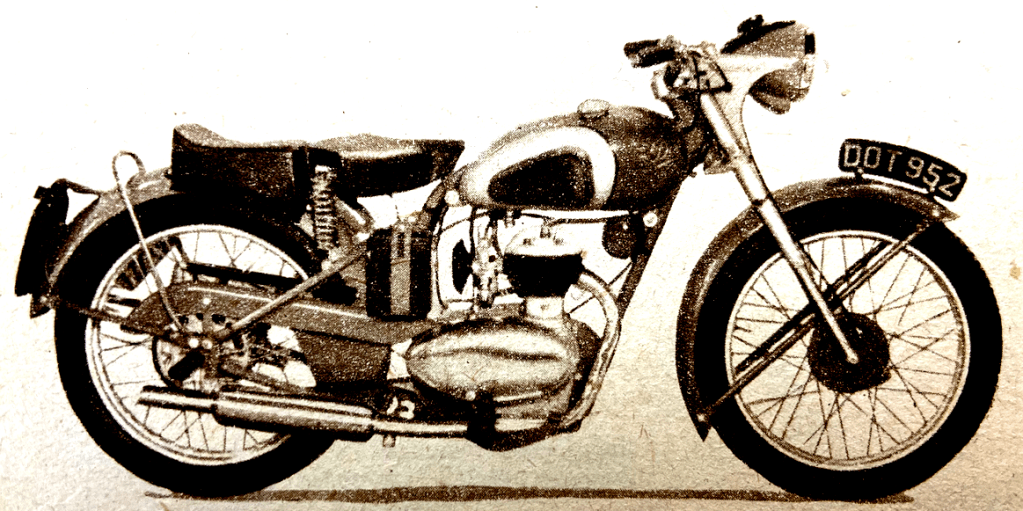

of its light weight and portability (the-handlebars fold back along the tank and the saddle pillar telescopes down). However, there are now available a number of conversions which broaden the appeal of this little machine very considerably. This is especially true of the JO Conversion Set which comprises a sheet-steel body; this encloses the engine and rear wheel and also provides an ample weather shield. One of the first autocycles to be introduced, the Cyc–Auto, remains essentially a mechanically propelled cycle in the sense that although a sprung fork is fitted and the frame is of very sturdy construction, the riding position is such that the machine can be used comfortably as an ordinary cycle. The engine is mounted in front of the bottom bracket of the frame, and drives through a worm shaft and bronze worm wheel; final drive is by a chain on the left-hand side. The multi-plate clutch is operated in the orthodox manner, but the handlebar lever, when it is pulled to the limit of its travel, actuates a powerful transmission brake. There are two basic models in the Dot range, one intended for normal road riding and the other for competition work. Both are fitted with the Villiers 197cc two-stroke engine with three-speed gear in unit. The road model may be obtained in two forms, the DST, which has Villiers direct lighting, and the RST, which has lighting incorporating a rectifier and battery. A sturdy loop-type frame is employed, and the front telescopic fork is of outstandingly robust construction incorporating forged steel lugs. The Competition model may also be obtained in two forms, equipped for scrambles or trials. The frame has been specially developed for high-speed rough riding and is braced for lateral rigidity and strutted for impact loadings.

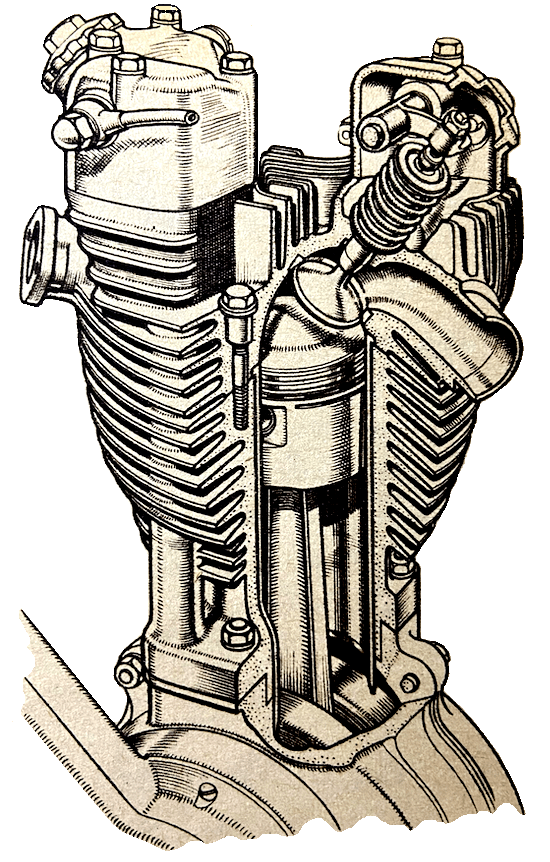

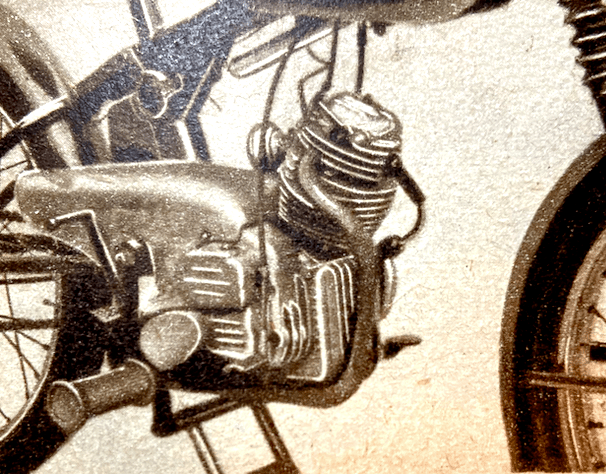

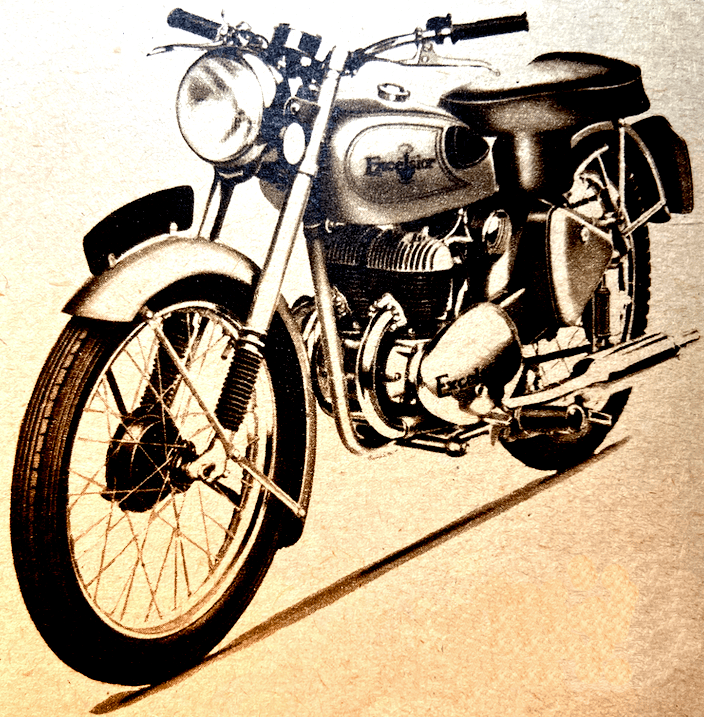

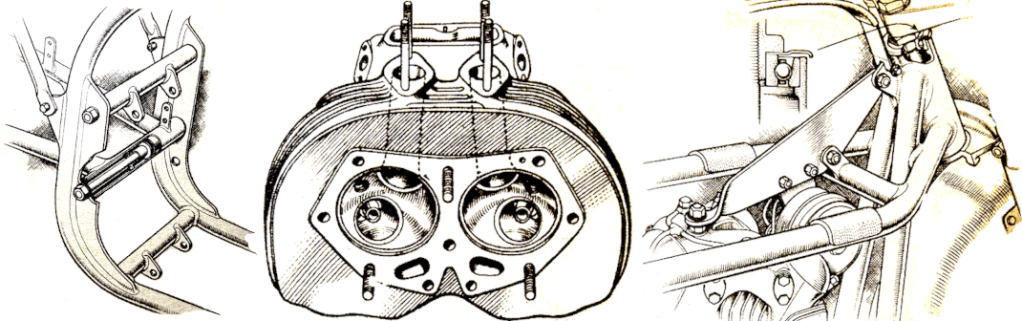

Latest development in connection with DMW models is that they may now be obtained with a novel frame made up of rectangular-section tube, welded at the joints and incorporating plunger-type rear springing. This frame is employed for the de luxe models. Standard models have an orthodox frame without springing, but have the same type of telescopic front fork that is fitted to the de luxe models. Direct lighting is employed. In addition to these four road machines there are competition models of 122 and 197cc, available with the solid frame or the rectangular-section tube spring frame. The appealing Excelsior range includes two 98cc autocycles and five motor cycles—two 122cc two-strokes, two 197cc two-strokes and, finally, a 244cc two-stroke twin. The autocycles are fitted with Excelsior engines, one has the Sptyt and is a single-speeder on orthodox lines, while the other is fitted with the Goblin, which has a two-speed gear in unit. Apart from these differences, the two models, which are respectively known as the Autobyk Sl and the Autobyk G2, are similar; they have a sturdy frame and a front fork controlled by rubber rings. Plunger-type rear springing is standard on all the other models. The frames are of the tubular loop-type, and a telescopic fork incorporating double-action coil springs is employed. Engines in the 122cc Universal models and the 197cc Roadmaster models are the famous Villiers units with three-speed gear box and positive-stop foot control. An outstanding model is the Talisman which is a 244cc parallel-twin Excelsior power unit with the four-speed gear box in unit. The light-alloy cylinder heads are separate

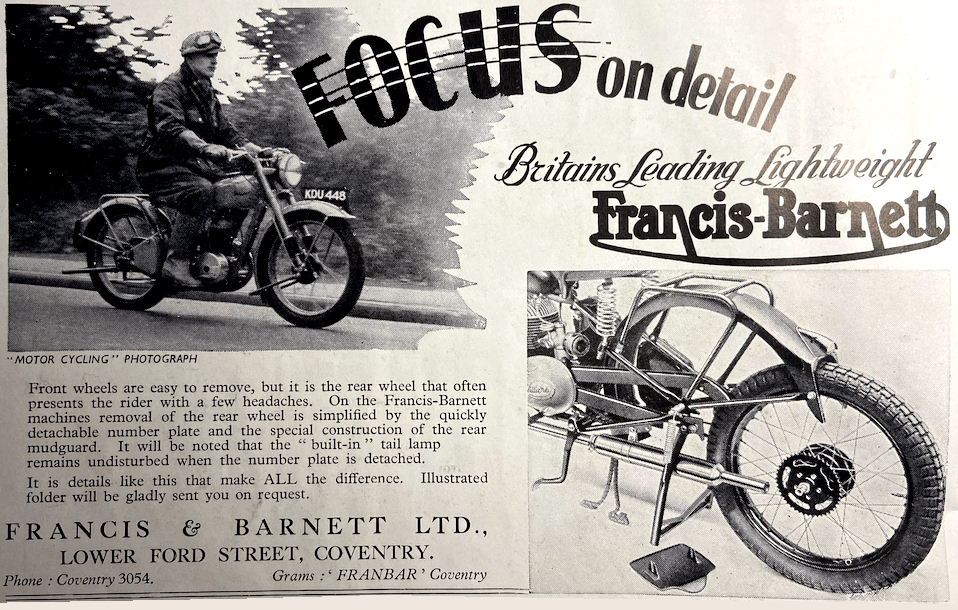

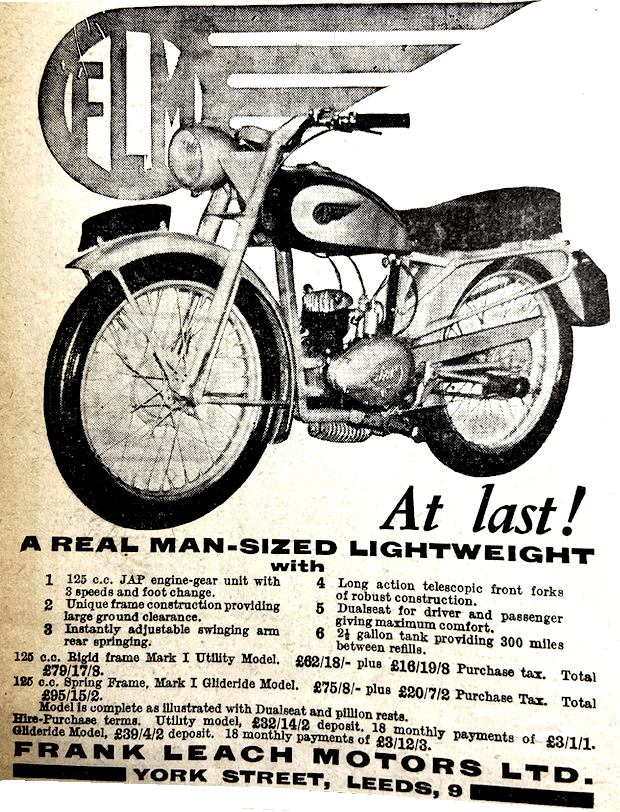

castings, as are the cast-iron cylinders. The crankshaft is supported by five bearings which ensures absolute rigidity and contributes to the inherent smoothness of the twin-cylinder two-stroke. A new lightweight motor cycle, the FLM, is coming on the market. The two models of which advance details are available are fitted with the 125cc JAP two-stroke engine gear unit. On is the Mark I Utility and the other is called the Mark I Glideride which has a channel-section frame with rear springing of pivoted-fork design providing instant adjustment to meet the conditions of usage. A twin-seat and pillion footrests are standard. There is an emphasis on quality and on ‘riders’ points’ with all Francis-Barnett machines. For instance, the all-black finish (azure blue to order) is not only becoming but is also beyond reproach; the silencers are most effective and are readily detachable for cleaning; the saddle is adjustable not only at the springs but also at the nose. A sturdy loop-type frame is employed, and the telescopic fork has three-rate springs which give a range of movement exceeding 5in. Other details are 3.00x19in tyres, a 2¼-gallon tank fitted with a reserve-type tap, and 5in-diameter brakes front and rear. The Merlin models are fitted with the 122cc Villiers engine, the 52 with direct lighting and the 53 with rectifier-battery lighting. The 197cc Villiers engine is fitted to the Falcon 54 model (direct lighting) and the Falcon 55 (rectifier-battery lighting). An autocycle is also included in the Francis-Barnett range. This is the Power-bike 56 which is fitted with the 98cc Villiers engine. Though the Indian Brave is produced in Great Britain, the entire output is exported to the United States. However, there is a chance that later on the machine will be available for other

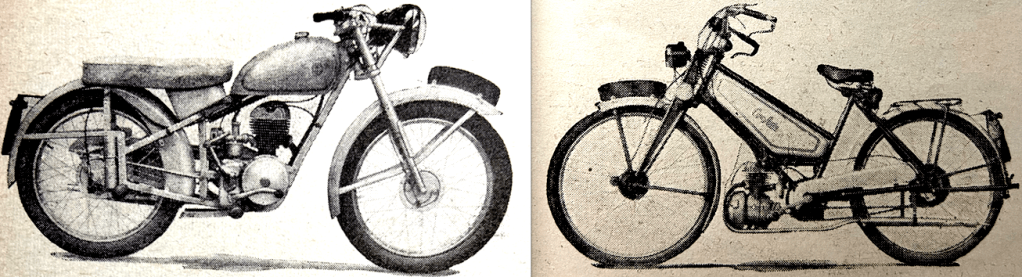

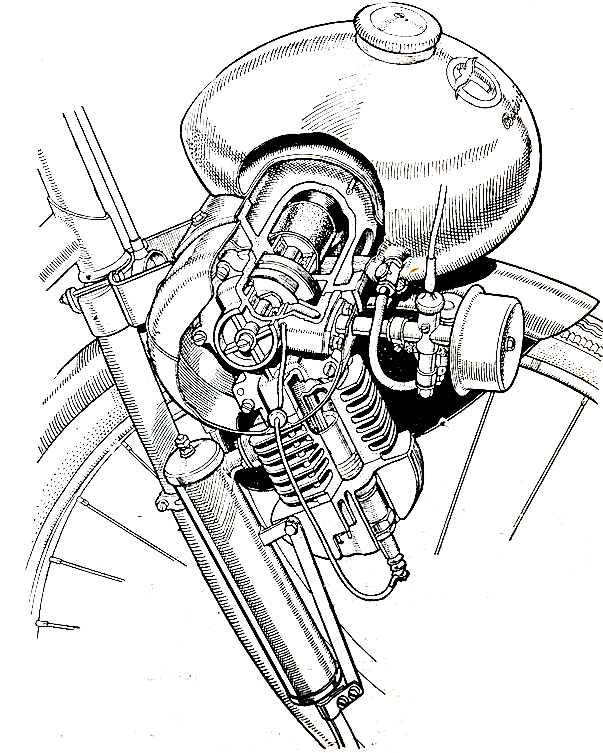

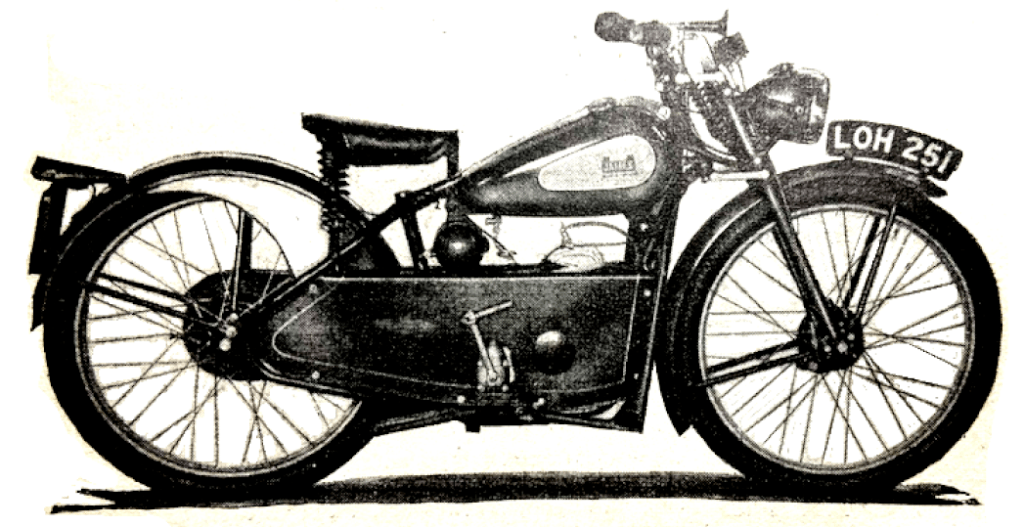

markets, including Britain. The Brave is particularly outstanding for its man-sized dimensions and for its lively performance. The engine is a 248cc side-valve, with a three-speed gear box in unit. Incorporated in the crankcase-cum-gear box casting is a sump, and lubrication is by means of a submerged gear pump. Another feature is that a Lucas 45-watt alternator is fitted on the crankshaft, and ignition is by coil. All James motor cycles are in the lightweight category. For 1951 the nine-model range was increased to 10 by the addition of a most interesting newcomer, the Commodore. This model, fitted with the 98cc two-speed Villiers engine-gear unit, makes a special appeal to the utility rider who requires good weather protection and prefers to ride in everyday clothing. The basis of the machine is the 98cc Comet but the engine unit, from the cylinder head down, and the transmission are shrouded by sheet-metal covers. Safety bars incorporate leg-shields. Fitted with the 122cc Villiers engine-gear unit, the Cadets may be obtained in standard form with direct lighting and in de luxe form with rectifier and battery lighting. For those who require a slightly more powerful machine there are the Captain Standard and the Captain de Luxe, with direct and rectifier-battery lighting respectively, which have the Villiers 197cc engine-gear units. Finally, there are two most attractive competition models developed from experience gained over a long period in all the important trials, including the ISDT. Cadet, Captain and competition models have a robust, tubular, loop-type frame and a telescopic front fork. Plunger-type rear springing is fitted on the Captain de Luxe model. James also market an attractive auto-cycle. An old favourite among autocycle riders, the New Hudson is a business-like little machine with a sturdy loop-type frame and a link fork with pressed-steel blades. The engine is the 98cc Villiers unit. Identical except for the engine-gear units, the Norman models Bl and B2 have a straight-tube frame with malleable-iron lugs. A specially, interesting feature is the Norman telescopic fork,

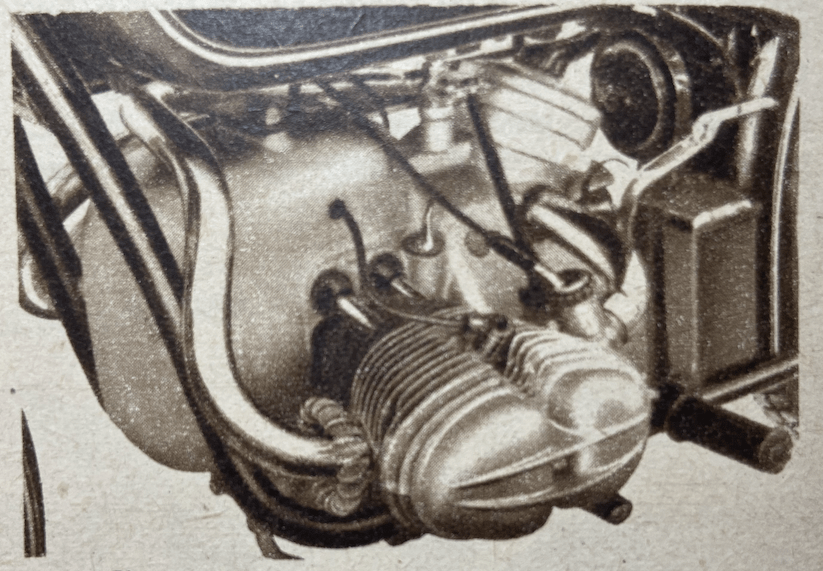

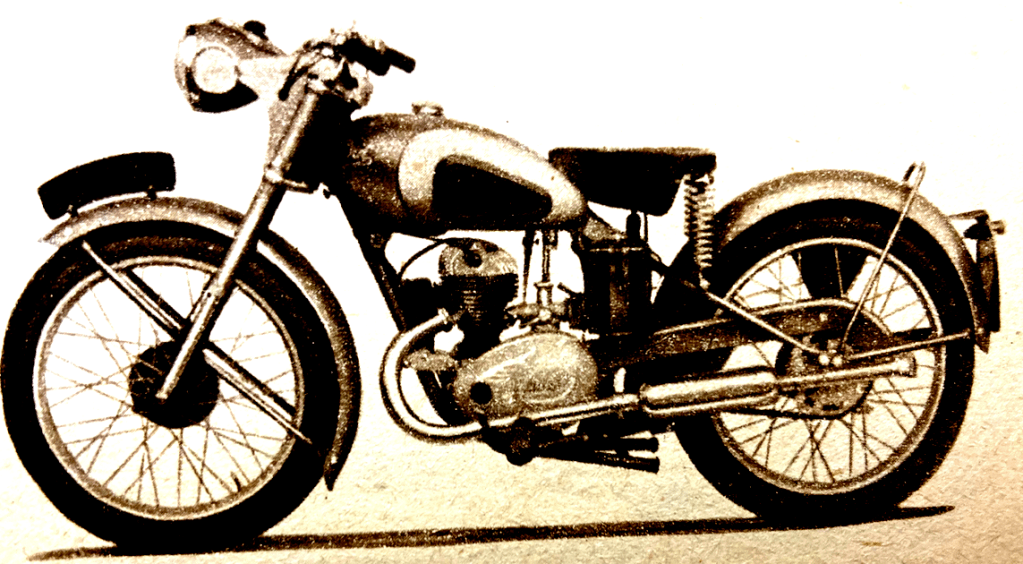

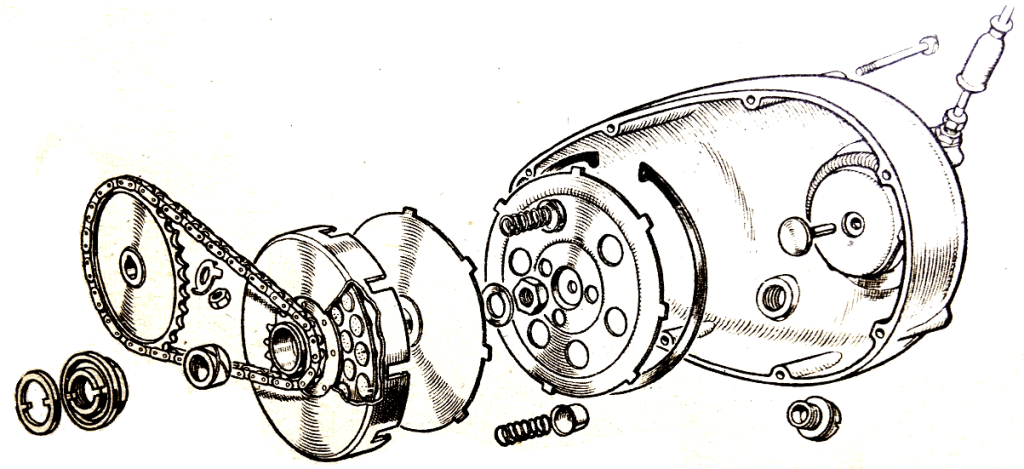

which utilises hydraulic damping balanced be-tween the two legs. This is achieved by a cylinder above the top lug which communicates with the two oil chambers. The 122cc Villiers engine is employed for the Bl and the 197cc for the B2. Other Norman models are the model D which has the 98cc Villiers two-speed engine-gear unit—and also a telescopic front fork—and the model C autocycle. Villiers 122 and 197cc engine-gear units are fitted to OEC machines. The loop-type frame is of welded and bolted-up construction and a telescopic front fork is employed. At an extra charge, a frame with pivoting-fork rear-springing is available. Special competition models are available fitted with either 122 or 197cc engine-gear units. Both frame and fork are specially designed. Though the 248cc ohv Panthers are in the lightweight category, they are full-scale machines in every way; indeed, the engine is similar in many respects to the 350cc Panther power unit and some components are interchangeable. A feature of the design is that, to ensure long life and reliability, special attention has been given to providing adequate working surfaces. The Model 65 and the 65 de luxe are similar except that the latter has the four-speed Burman gear box and a slightly different finish. Ignition is by coil. The Stroud Competition model has a modified frame resulting in a ground clearance of 6¾in, a 1½-gallon tank, a high-level silencer, strengthened footrests, a Lucas ‘Wading’ magneto and various other detail modifications. Completely redesigned for 1951, Royal Enfield’s famous Model RE has a welded, tubular frame of the loop-type and a telescopic front fork. The 125cc two-stroke engine-gear unit is attached at four points and is of advanced design with a light-alloy cylinder head, twin transfer ports, and the single-plate clutch mounted on the crankshaft. The three-speed gear box has fully enclosed, positive-stop foot-change. Coil ignition is by a crankshaft-mounted Miller AC generator. Output of this new engine is said to be 4½bhp at 4,500rpm; this is about ¾bhp higher than the earlier engine. Plunger-type rear-springing is fitted to the 122 and 197cc Sun models. The loop-type frame is specially robust and gives a man-size riding position With a saddle height of 29in. The telescopic fork is fitted with double-action springs and the fork lugs are steel forgings. Engines are the famous Villiers units with three-speed gear boxes incorporating positive-stop foot change. The three-model range is completed by the attractive 98cc de luxe model which has the Villiers two-speed

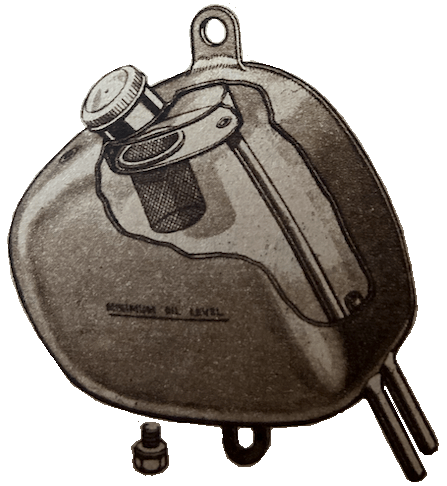

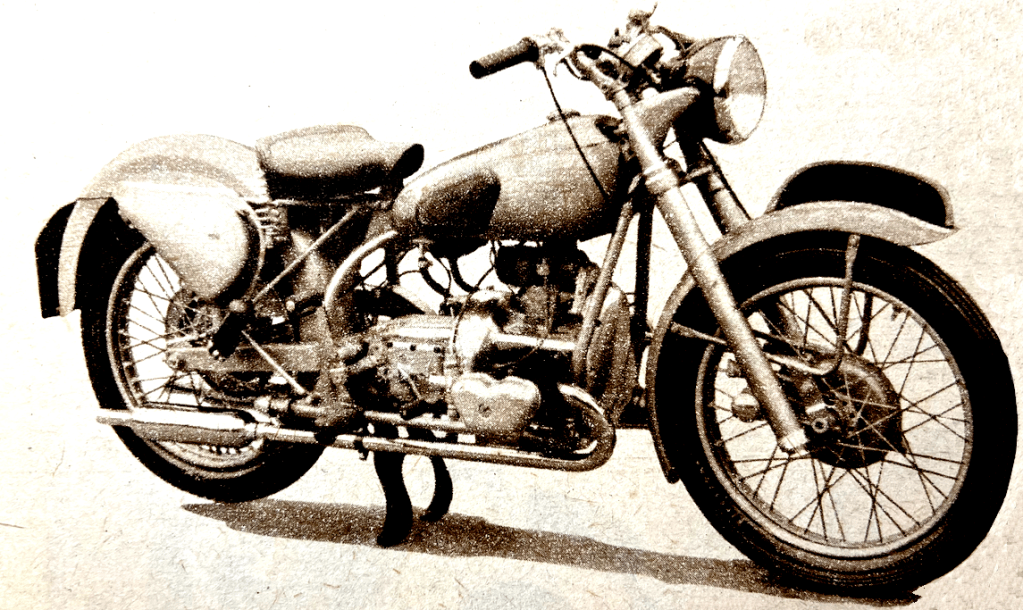

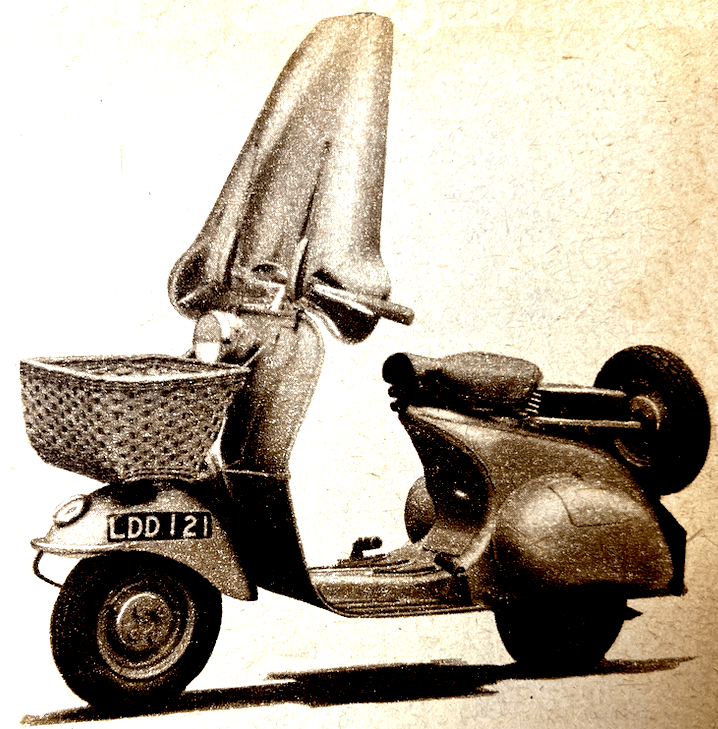

unit. All models are finished in maroon. Solo and sidecarrier Swallow Gadabout models are available. The solo machine has the Villiers 122cc unit and the sidecarrier machine, which is intended for commercial purposes, has the Villiers 197cc unit. Both are equipped with a large weather shield and a bonnet which enshrouds the engine, transmission and rear wheel, and which provides a very large and comfortable seat. Latest addition to the Tandon range is a competition model named the Kangaroo. This model has a specially stiffened-up frame and fork, an under-shield, a smaller-than-standard (1 gallon) petroil tank, light-alloy mudguards, a quickly detachable headlamp, and tyres of 2.75x21in (front) and 2.25x19in (rear). The established 122cc Supaglid and 197cc Supaglid Supreme models are specially attractive for the pivoting-fork rear suspension controlled by a rubber cartridge and a long-action telescopic fork, and for their elegant lines. Also marketed is the Milemaster, which has the 122cc Villiers engine with hand change. The frame is specially interesting. It is of the duplex type made up from straight tubes clamped in Elektron lugs. The telescopic front fork has pre-loaded springs, the tension of which may be varied according to road conditions. Though the VeloSolex with its 45cc two-stroke engine driving the front wheel by Carborundurn-faced roller might well be considered in the motor-assisted cycle category, it is sold as a complete machine. For 1951, engine modifications resulted in increased power output and better low-speed two-stroking, and lubrication has been improved. Specification includes direct lighting. Few motor cycles have aroused more interest throughout the world than the Velocette Model LE. The machine is of most advanced design, with a horizontally opposed, twin-cylinder, water-cooled, side-valve engine in unit with a three-speed gear box, shaft-drive to the rear wheel, pivoting-fork rear suspension (adjustable for load), and a telescopic front fork. The backbone of the frame is a steel pressing, to which is welded the rear mudguard. For 1951 the engine size was increased from 149 to 192cc, and necessary modifications were made to the engine to withstand the increased power output, which gives the latest LE livelier acceleration and better hill-climbing properties.”

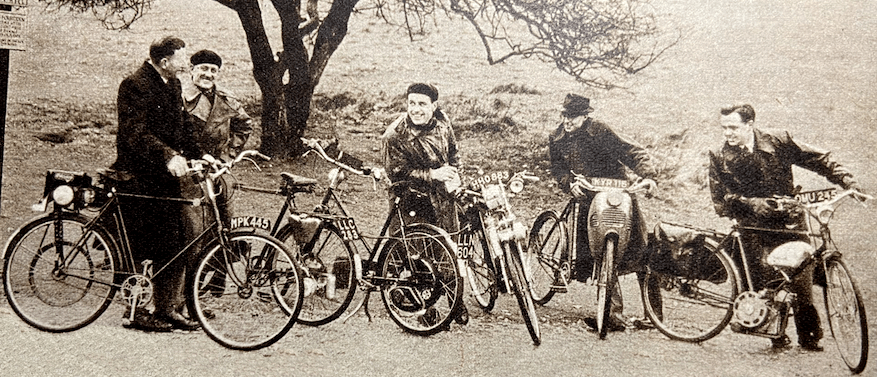

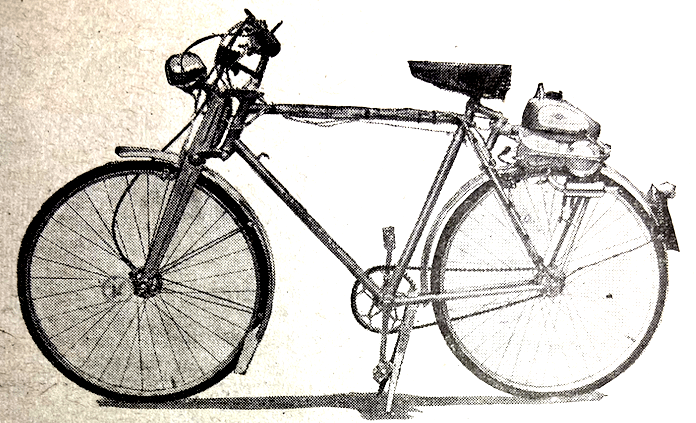

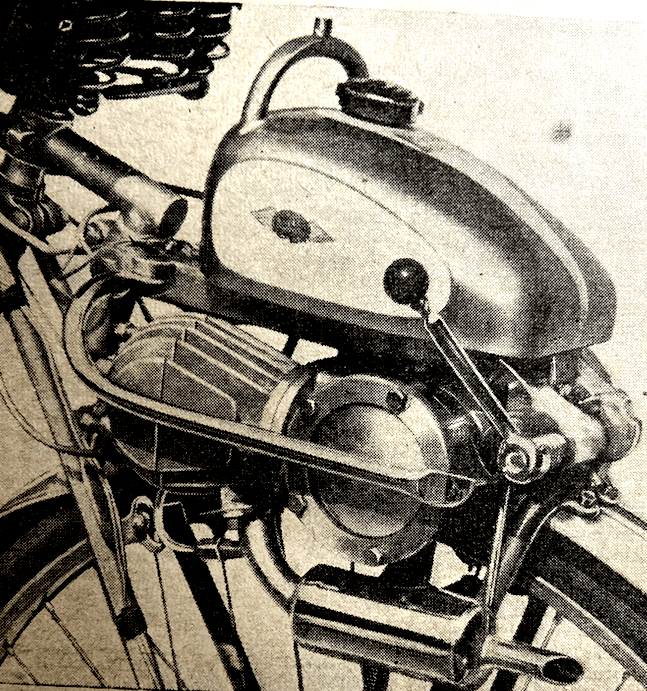

“FEBRUARY, BRITISH READERS will recall without much pleasure, justified its ominous title of fill-dyke. And Tuesday, February 20, made a worthy contribution to the month’s rainfall. In Surrey at 10am the rain pelted down; relentlessly it continued at 11am, at 12, at 1pm, at 2…No occasion for buzzing around Box Hill on motor-assisted cycles (MACs)—at least, not the most propitious of occasions. Some weeks earlier in the office we had this line of thought: bicycle propulsion units—micromotors or clip-ons to those who are fascinated by an expressive, single word—are being produced in ever-increasing quantities; the number of makes in the list creeps up until, if we cheat just a wee bit, we can call it a round dozen (‘cheat’ because our list includes the VeloSolex, sold as a specially designed cycle complete with engine, and therefore not in precisely the same category as all the others which are engines for fitting to a normal pedal-cycle); the variety in design, in methods of attachment, and in drives employed, provides plenty of material for thoughtful study; the appeal of the micromotor has been established and power-propelled cycles are nowadays common on British roads; hence why not ask the manufacturers to join us in a gossip on powered cycles and to bring with them at least one of their models for members of the Staff to gallop around the lanes? At 11am on that Tuesday, more than 20 members of the industry with five of The Motor Cycle Staff were drinking coffee in the lounge of the Burford Bridge Hotel. The bicycles were in the garage. Every make was there except the Bikotor, which is not yet quite ready for production. Since the programme included discussion as well as riding, the obvious thing to do was to talk first and ride later—by then the weather could not be worse. Discussion ranged over such varied topics as the best type of cycle for attachments, speeds, service, decarbonising, lubrication, insurance, taxation, driving licences, and free-wheels. Here are some of the broad conclusions. Any cycle in reasonably good mechanical condition, except the few ultra-lightweight racing types, is deemed suitable for a micromotor. Some frames are better than others and perhaps the best is the fairly sturdy roadster with its longish fork trail. Brakes should be in first-class condition to cope with the slightly higher speeds usually employed when an engine is fitted. Internal-expanding hub brakes are better than rim brakes, mainly because the latter lose efficiency in wet weather. If the drive is by roller on a tyre, the driven wheel should run true. Should special cycles be developed for attachments? The conclusion was ‘no’ for a number of reasons, but mainly because, (a) the attraction of being able to add an engine to a cycle already in use was lost and (b), the special powered cycle with fittings such as a spring fork and bigger tyres and saddle, was already a long-established type—the autocycle. However, experience in Continental countries suggests that there might well be a market for sprung forks, larger saddles and other fittings as accessories to appeal to the type of owner who had the inclination to make his machine more luxurious. Speeds have a bearing on the suitability of the average cycle. If habitual speeds are far in excess of those usual when pedalling, then the stresses on wheels, frame and brakes could be higher than envisaged by the cycle designer. With the possible exception of two units, both imported from the Continent, the micromotors are designed to provide speeds only slightly above those usually accomplished by the average sporting cyclist. In any case, the standard cycle with its unsprung frame and fork, small-section tyres and small saddle is inclined to be uncomfortable when travelling fast. Statistics indicate that about 60% of purchasers of micro-motors are completely unfamiliar with any form of internal-combustion engine. Instances were given of owners who called for help when a plug lead became detached, or when they had forgotten to turn on the petrol tap. The two-stroke micromotors are extremely simple and only the most rudimentary knowledge is required to deal with all likely stoppages. Periodic maintenance is largely a matter of decarbonising the engine and exhaust system, and a general check-over of the ignition and the carburettor. Decarbonising is usually required at 1,000-2,000-mile intervals, though much depends on running conditions and the amount of oil used in the petroil mixture. An engine used for longish journeys on fairly wide throttle openings will carbon up less quickly than one which spends its life on short trips and thus rarely gets more than warm. Indeed, instances were given of mileages well in excess of 2,000 between decarbonising. Charges for this periodic work range from about 7s 6d to 15s, depending

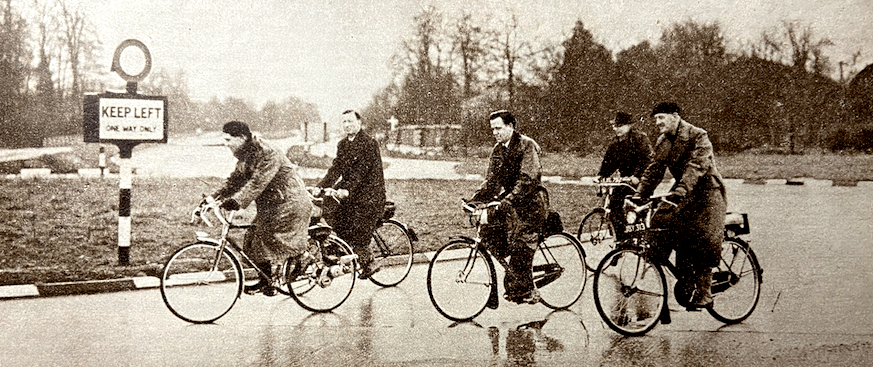

on how much attention is necessary. The makers’ recommendation on the petrol to oil ratio must be followed—for the two-stroke engines on the British market the ratio varies from 16 to 1 to 30 to 1. But a fairly common tendency among owners is to be liberal with the oil; to add a bit more ‘just for luck’. There is no merit in this practice, because the additional oil carbons up the engine more quickly and often aggravates four-stroking. Another point is that the oil should be of the correct grade because a heavier oil (thicker, and with a higher SAE number) also causes quicker carbon formation. It is recognised that the variety of petrol to oil ratios and of oil grades recommended is an undesirable complication and can be a headache to filling-stations. Efforts are being made to standardise ratios and grades of oil. The ideal would be the standardisation of, say, 25 to 1 petrol to oil, and this to be available ready mixed straight from a pump in quantities from a quart up. More might be heard of this scheme before very long. Just as with decarbonisation periods, so running conditions have a big influence on petroil consumption. Anything from 150-300mpg can be expected with an engine in good condition. Insurance rates range from as low as 7s 6d a year for third-party cover up to £2 for a comprehensive policy; one particularly attractive comprehensive policy at £1 17s 6d covers any rider, so that the MAC could be a maid of all work for every member of a family with a driving licence. As might be expected, driving licences came in for a good deal of discussion. There is a strong case for those who argue that a motor-assisted cycle is essentially a cycle and that the rider should be treated as a cyclist—no driving licence, road tax or insurance. On the other hand, there is the view that cyclists should be treated as other vehicle owners and comply with all the formalities, and charges. Perhaps a typical British compromise would be a solution—a fixed annual fee to cover licence, tax and third-party insurance to apply to both macs and cycles. No ‘L’ plates and driving tests, because the value of the tests would be doubtful and in any case it would be impracticable m test the 12-14 million cyclists in Great Britain without a veritable army of examiners. Even with things as they are today, the cost of buying and running a micromotor is remarkably low. For the two-strokes, prices range from £18 18s to just over £27, with the majority in the £20-25 range. Exceptions are the four-stroke Cucciolo with two-speed gear at £40, and the VeloSolex sold as a complete machine at £48 odd…a driving licence costs 5s a year and the driving test fee is 10s. Road Tax is 17s 6d a year; third-party insurance, say, 10s a year; petrol consumption, say, 200mpg. The return for the outlay is no more hard pedalling. True, in hilly country, the pedals will have to be used to assist the engine, but with nothing approaching the energy needed for an ‘un-assisted’ cycle. Or it may be necessary on very steep hills to dismount and push; the only disadvantage compared with doing the same thing with an ordinary cycle is the additional weight of the engine and fuel—say, 20lb. Another advantage is that because the hard work is taken out of cycling the owner of an MAC is almost certain to travel farther afield than he did when he had to pedal all the time. Many a newcomer has bought a clip-on solely with the idea of easing the labour of his cycle ride to and from work and then became an enthusiast for week-end trips out of town on his new-found means of easy, pleasant, cheap transport. All these aspects were informally discussed as the rain sheeted down. As we had lunch, the weather brightened. Well, good or bad weather, we of The Motor Cycle Staff—Arthur Bourne, Roy Morton, Hugh Burton, John Mills and I—were determined to gallop the 11 macs around the Surrey roads. The makes represented were Bantamoto, Cucciolo, Cycloid, Cyclemaster, Cymota, GYS Motomite, Mini-Motor, Mosquito, Power Pak, VAP and VeloSolex. Some manufacturers had brought more than one example of their products and there were well over a dozen machines available. We buzzed along the Dorking-Leatherhead by-pass, round the islands and turned circles in the road to get the feel of low-speed pulling and manoeuvrability; and up the Box Hill zig-zag road, with its gradient ranging from 1i in 25 to 1 in 8 to see how much pedalling, if any, would be necessary. Repeated swops of machines were made and it is a compliment to the simplicity of macs that no one seemed to want more than the most sketchy instructions on which control did what. Though the rain eased off and stopped entirely at times, the roads were almost awash. Do drive rollers slip on wet tyres? The answer is ‘no’ so far as my experience showed. I tried every roller-drive attachment and never once obtained slip even when I endeavoured to provoke it. Another point that impressed itself on me was that there is a fair difference in the type of performance given by the various units. Some are supremely happy pulling hard at low speeds, while others are at their best when nipping along. This impression. emphasised an aspect brought out by a dealer (who is also an importer) that the wide variety of makes available is a good thing because there is the opportunity for a buyer to be recommended the unit best suited to his or her needs. The extreme example would be a middle-aged lady who wanted shopping transport compared with the hardened motor cyclist who was interested in a MAC as an addition to his stable. The former would be recommended the most simple and docile unit, while the latter would probably not require advice—he would probably choose a ‘peppy’ job. But my colleagues also have their impressions and this is what they say: Arthur Bourne writes, ‘In youth and in the recent periods of no petrol except for essential purposes, I frequently bicycled in the Dorking-Leatherhead area, in which

Burford Bridge lies. With the power-assisted bicycles, instead of having to slog up the hill or against the wind, I was either freewheeling or gently twirling the pedals to enable the engines to maintain their power and gait. This was as expected, but. what proved a surprise was that, not having to dissipate any appreciable amount of energy, I found myself able to take an interest in everything around to an extent I had never previously known. There and then I decided that I should like to have a machine—one of the several really quiet ones—for exploring the byways near my home. With it I should be able to see more and to learn more than by any other means. How quiet some of the latest models are was revealed by Harry Louis and I chatting away as we rode along side by side and, perhaps more forcibly, by my hearing the songs of the birds in the woodlands —yes, and the drip of water from the trees. . .’ Roy Morton writes: ‘I never had a cycle as a kid. In fact, I rode a motor cycle for several years before the chance of sampling a pedal. cycle came my way. My approach to these clip-ons, therefore, was essentially that of a motor cyclist with but dim recollections of the hard work and comparative discomfort of pedal-cycling. First impression was the length of time required to cover a given stretch of road compared with the potent 500 that had borne me up Box Hill. However, on uncoupling the motor drive and using my two shanks as motive power, I was very surprised how comparatively fast had been the gait when engine-propelled. Impression No 2 was, and is, amazement at the climbing powers of these tiny engines. Gradient of the Alpine road up Box Hill is such that, when freewheeling down, a speed approaching 40mph is attained if the brakes are not applied to check it. When going up, only an occasions twirl of the pedals was required to keep the engine happy. Even when the speed was allowed to drop to little more than a walking pace, so that the engine was on the point of stalling, only the lightest of pedal assistance was required to pick up speed again, this on a gradient almost impossible to climb by pedalling alone. Climbing the Alpine road with a clip-on was like cycling along the level with a strong following wind. These little units take all the work out of cycling, leaving only the pleasure.’ Hugh Burton writes: ‘It was what the Irish euphemistically call “a soft day”—wet and blustery; but I must say I thoroughly enjoyed it. These mustard-hot engines took us up the winding Surrey lanes with great gusto, and one added little to one’s knowledge of ankling. Indeed, my main criticism of some of the clip-ons is that they are too powerful. After all, a bicycle frame (especially a ladies’ open-frame model) is none too rigid. It is not designed for power propulsion over the 20mph mark. No, I feel that the ideal clip-on must have plenty of urge low down. Low-speed pulling, especially if the owner is a town-dweller, is of greater importance than a comparatively high maximum speed or even startling hill-climbing. For the clip-on owner should, I feel, be prepared to help his little engine on dragging gradients. If he requires greater performance he should graduate to the autocycle or light motor cycle. At present, the little engines are, in the main, designed on the right lines. They are simple and light and they pull well. There should be no attempt to provide luxury features. The fact that, in the event of trouble, the owner may disconnect the drive and pedal to a garage or to his home, is confidence inspiring. He is his own ‘get-you-home’ service. I think the controls of some clip-ons could be simplified. The best I tried consisted of a single twistgrip. Turned one way, the decompressor was brought into action, when one could pedal the machine from a

standstill. Once under way, the twistgrip was opened, whereupon the engine fired end got going.’ John Mills writes: ‘Nobody would ever suggest that I was an enthusiastic pedal-cyclist, and any form of device that relieves effort meets with my approval. Box Hill in pouring rain is perhaps not an ideal place for testing clip-ons, but rather to my surprise the bicycles did not suffer from any feeling of instability. Mostly because of the smooth running and quietness of the power units, it was not until I tried pedalling that I realised just how easily the ground was being covered. It was my luck that my first pick was a machine with very little petrol in the tank, and about a mile from base the engine died. The effort necessary to ride back, with the engine disconnected from the wheel, was sufficient to convince me of the value of a micromotor. Hill-climbing capabilities.of the machines were quite extraordinary—very little lpa was necessary at any time. In fact, the only drawback I found on some machines was the poor brakes. This was due mostly to the wet weather and, of course, being used to first-class motor cycle ‘stoppers’, I tended to leave braking a little late. To sum up, I spent a most enjoyable day riding these machines and would not hesitate to recommend their use to anyone who wants to take the ‘pedal’ out of pedal-cycle.’ SPECIFICATION SUMMARIES. Bantamoto: 40cc two-stroke mounted on an extension on the rear wheel spindle at the left side and driving the wheel by gears. Weight 181b. Price £21. Makers, Cyc-Auto, Brunel Road, East Acton. London W3. Bikotor: 47cc two-stroke mounted across the rear wheel and driving by roller on the tyre. Production expected to start shortly. Marketed by Dennis R Mead, 190-195, Picadilly, London, W1. Cucilolo: 48cc ohv with a two-speed pre-selector gear box in unit. Attachment is to the cycle bottom-bracket and down tube; drive is via the cycle pedalling chain. Weight 17½lb. Price £40. Concessionaires, Britax (London), NW6. Cyclaid: 31cc two-stroke mounted above the rear wheel which it drives by V-belt. Weight, 151b. Price £20. Makers, British Salmson Aero Engines, London SW20. Cyclemaster: 25cc two-stroke housed in a special rear-wheel hub. Enshrouded chain drive. Weight 34½lb including wheel. Price £25. Marketed by Cyclemaster, London SW7. Cymota: 45cc two-stroke mounted across the front wheel which it drives by roller. The unit is enclosed by a pressed-steel cowl. Weight 221b. Price £19 19s. Distributors for UK, Blue Star Garages, London WI4. GYS Motamite: 49cc two-stroke mounted across the front wheel and driving by roller on the tyre. Weight 221b. Price £22 1s. Makers, GYS Engineering, Bournemouth, Hants. Mini-Motor: 49cc two-stroke mounted over the rear wheel and driving by roller on the tyre. Weight 221b. Price £21. Makers, Mini-Motor, Trojan Way, Croydon, Surrey. Mosquito: 38cc two-stroke attached below the cycle bottom-bracket and driving the rear wheel by roller on the tyre. Weight 211b. Price £25. Marketed by Mosquito Motors, Liverpool 2. Power Pak: 49cc two-stroke mounted across the rear wheel with the cylinder inverted and driving by roller on the tyre. Weight 221b. Price £25. Distributors: Sinclair Goddard & Co, London W2. VAP: 48cc two-stroke mounted on an extension of the rear-wheel spindle on the left side and driving by chain. Weight 201b. Price £28 7s. Concessionaires: Frank Lawrence Motor Cycles, London SW11. VeloSolex: 45cc two-stroke mounted across the front wheel and driving by means of a roller. Machine is sold complete as a motor-assisted cycle. Price £48 5s 2d. Makers, Solex (Cycles), London NW1.”

“THE ORIGIN OF the term petrol has now been doubly solved. In quite another connection I reported recently how a bibliophile reader has discovered that Edward Butler, designer of the first British motor tricycle, wrote books, one dealing with carburation. This happy student finally unearthed a copy of the carburation book in its second (1919) edition. In it Butler says: ‘The designation “petrol” was first used and registered by the writer in 1887, which term has been adopted in this country to include all brands of motor spirit.’ Later, on the same page, Butler describes a Lenoir carburettor, in which ‘essence de petrole was fed into a revolving cage, containing a sponge’. The second quotation appears to explain where Butler found his word, and further suggests how the French cut the three-word term to the single word ‘essence’, which they still use to-day.”—Ixion

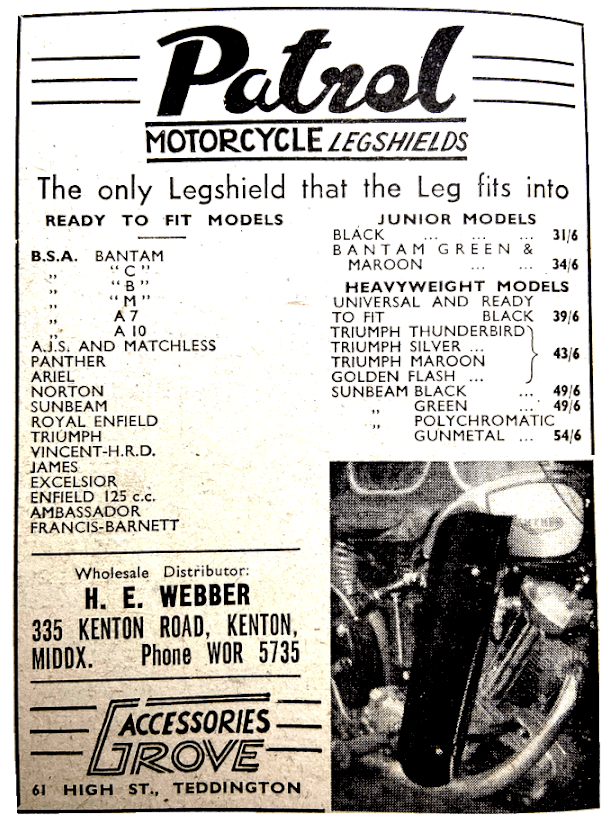

“I IMAGINE THAT the vendors of windscreens are pleased with their turnovers. Time was when you pilloried yourself when you fitted a screen. That nonsense is a thing of the past. Lads who do not wish to look fast or to burn the tar off the road surface even retain their screens through the summer without a blush. In the January cold snap I saw several very ‘warm’ speedmen riding behind windscreens even in town use. We are growing more sensible, and the increased sale of screens is partly due to the fact that screens are more rigid than they used to be, and no longer flap. I even see some owners of clip-ons using screens. If and when somebody introduces really good legshields, easily attached and detached, I think they, too, will grow more popular.”—Ixion