Before we dive into the new decade, here’s a treat—a brief overview from The Motor Cycle’s master historian (and wartime DR and all round good guy) Bob Currie. You’ll find the complete article in his superb book, Great British Motor Cycles of the Fifties. Like the rest of Bob’s books, it’s a joy to read, as is this short excerpt…

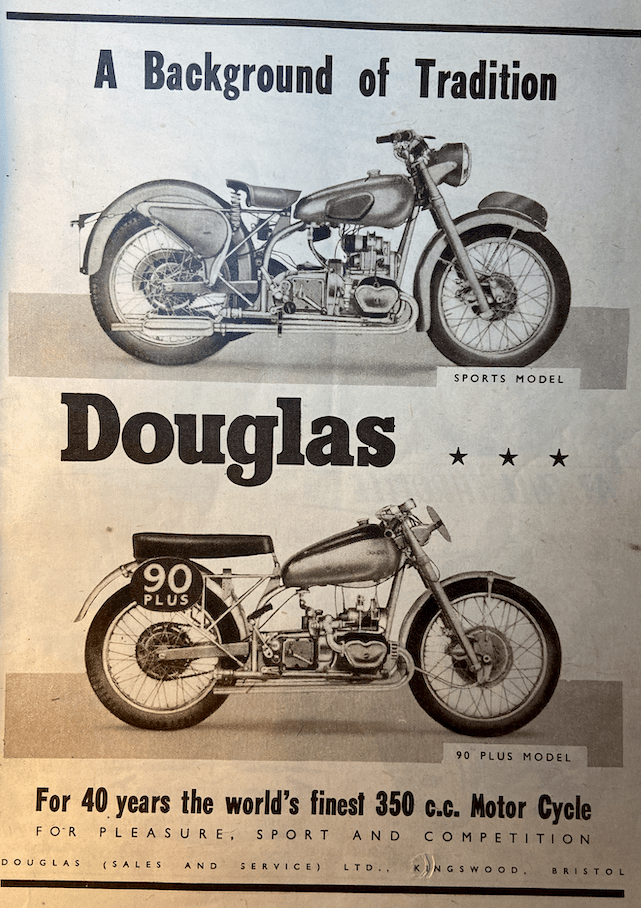

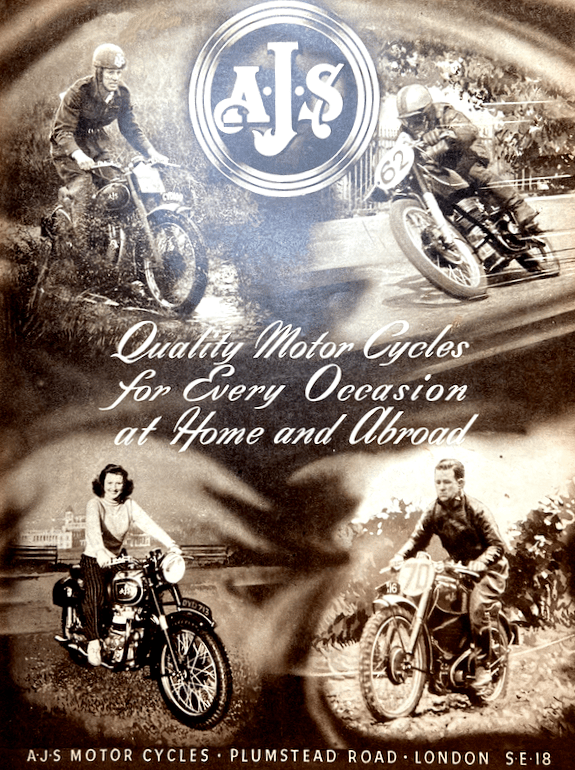

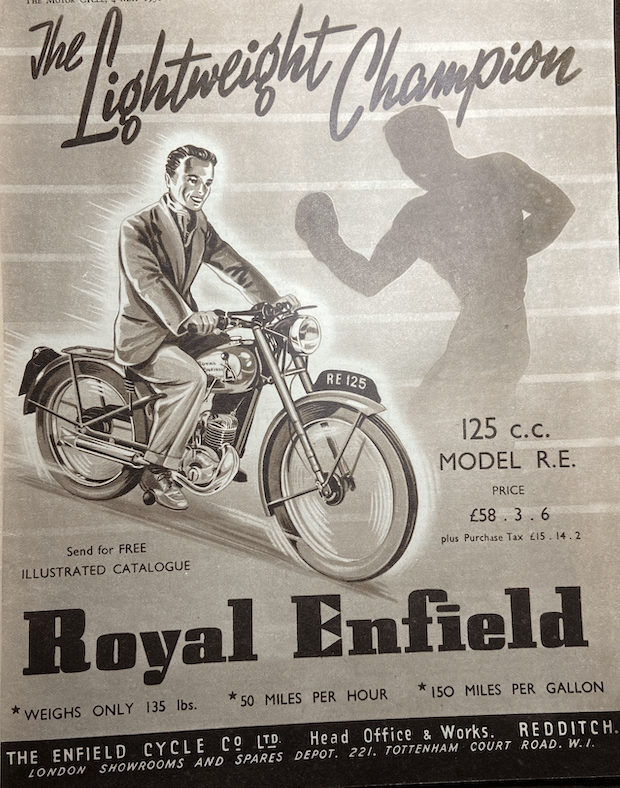

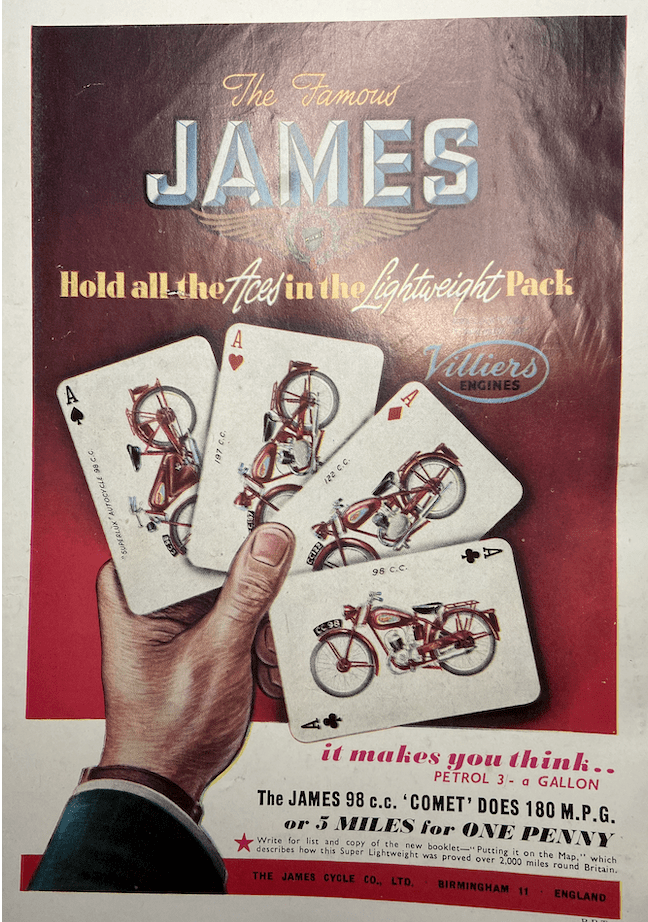

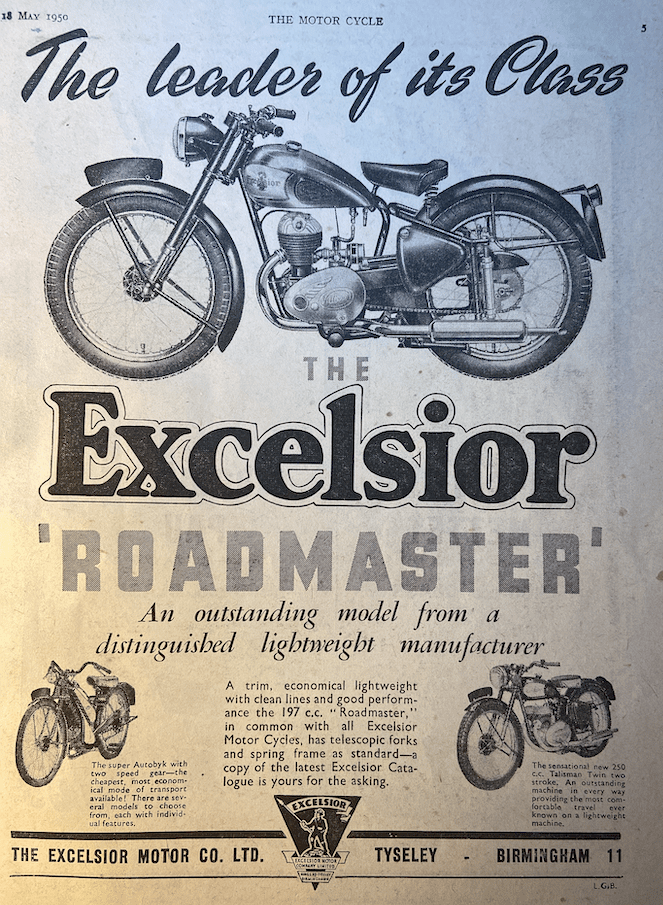

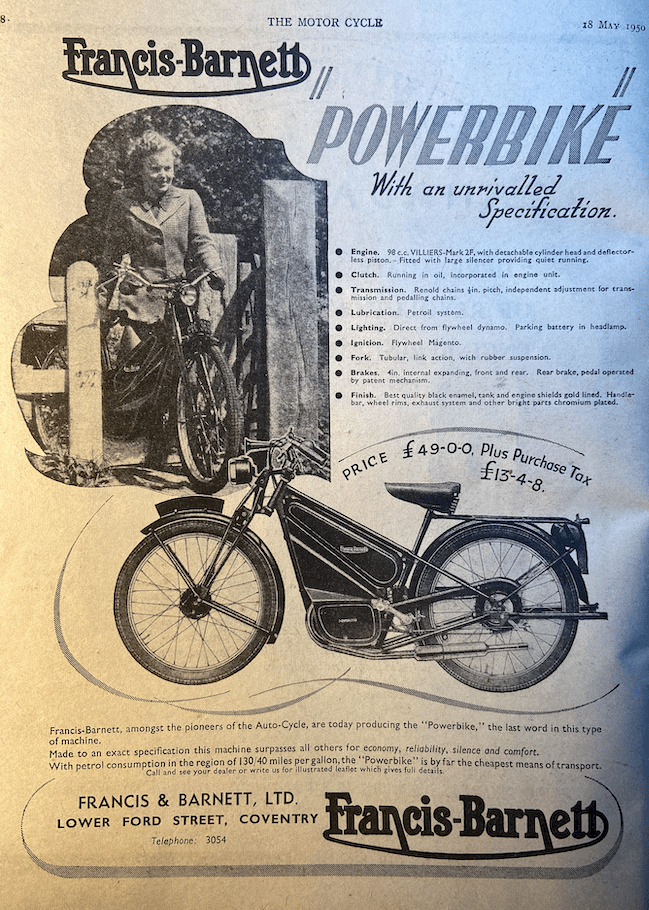

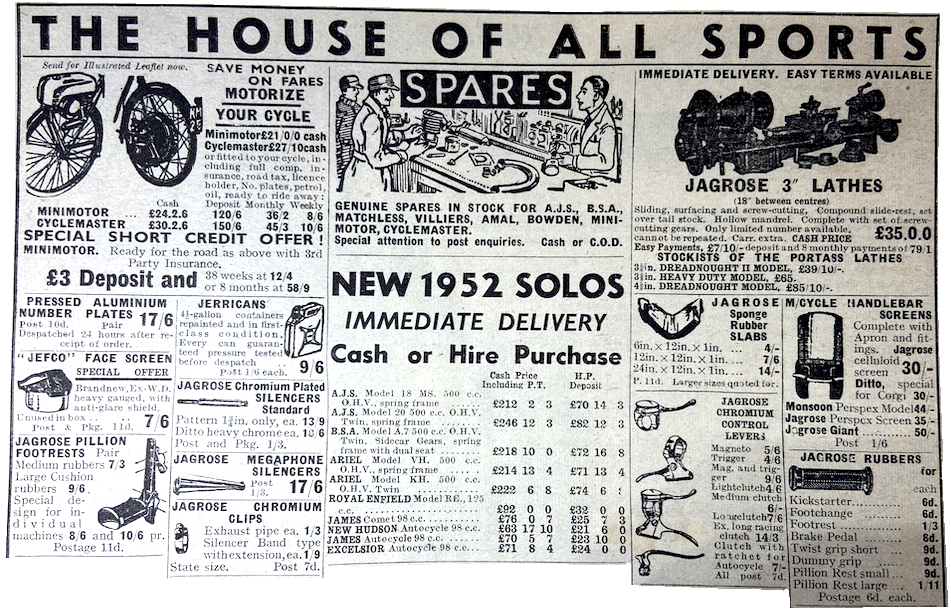

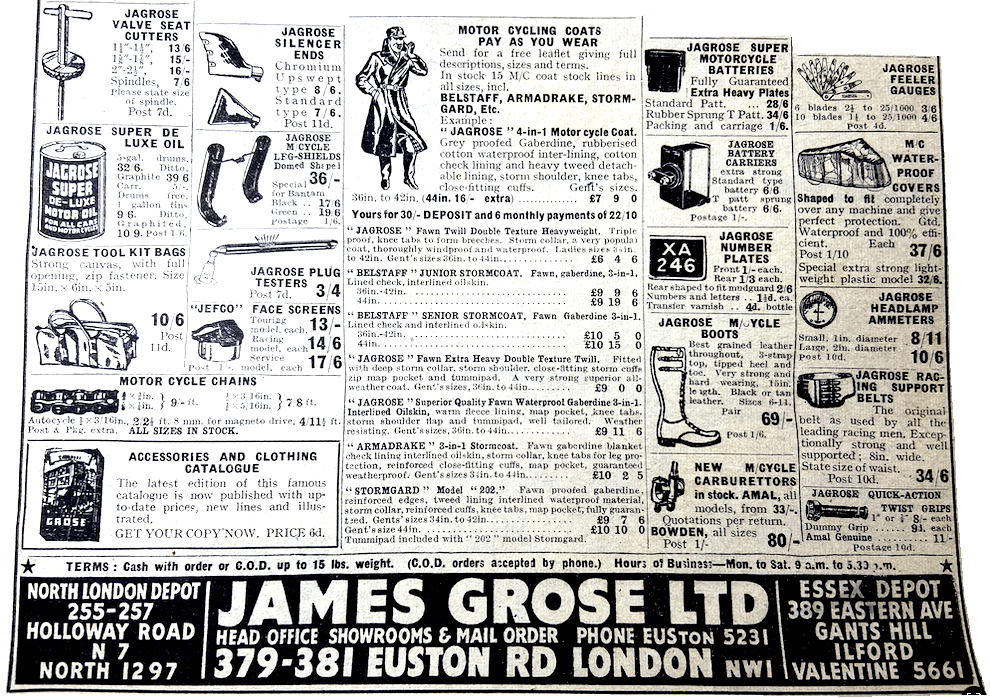

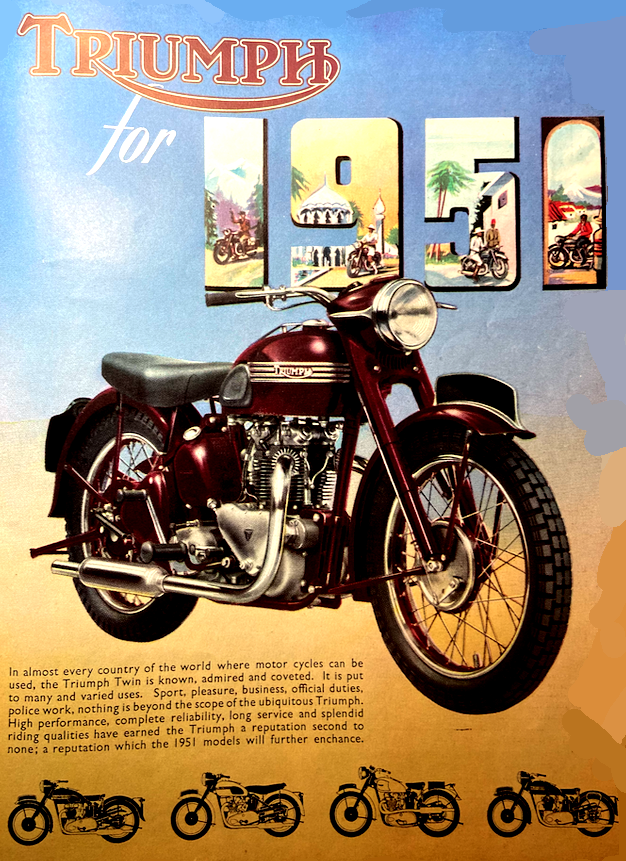

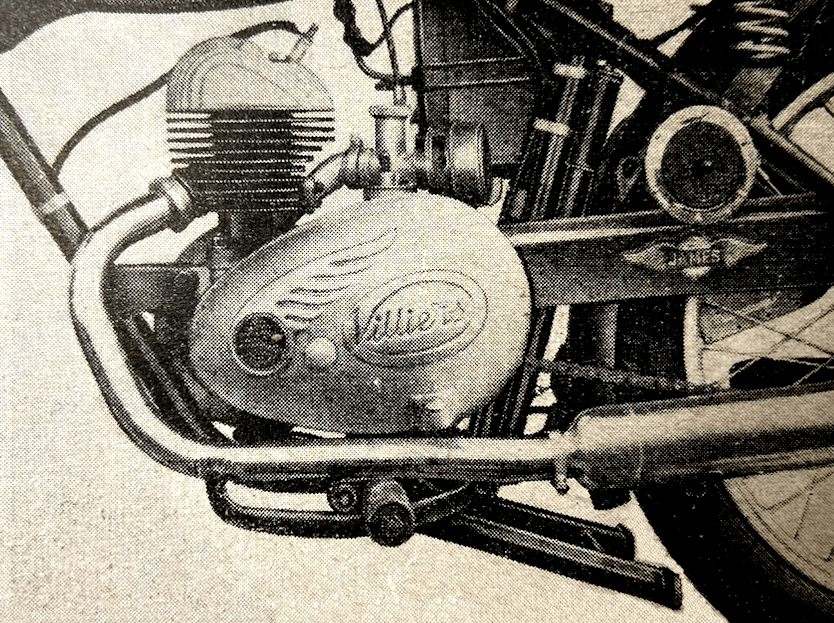

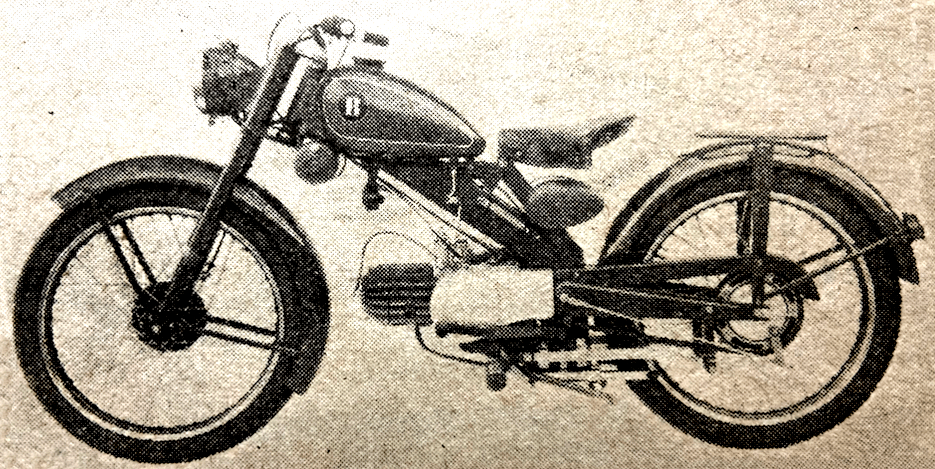

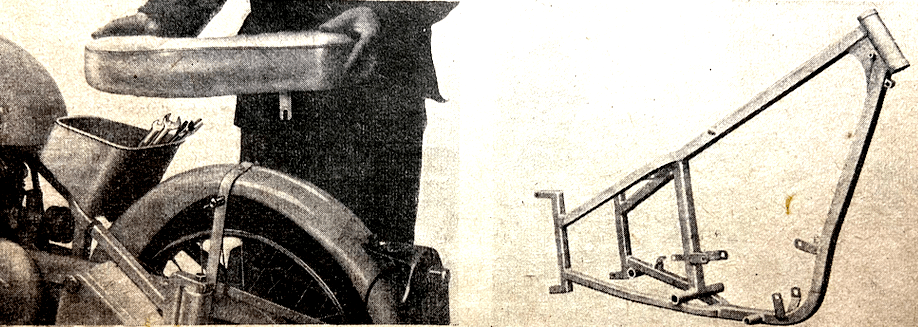

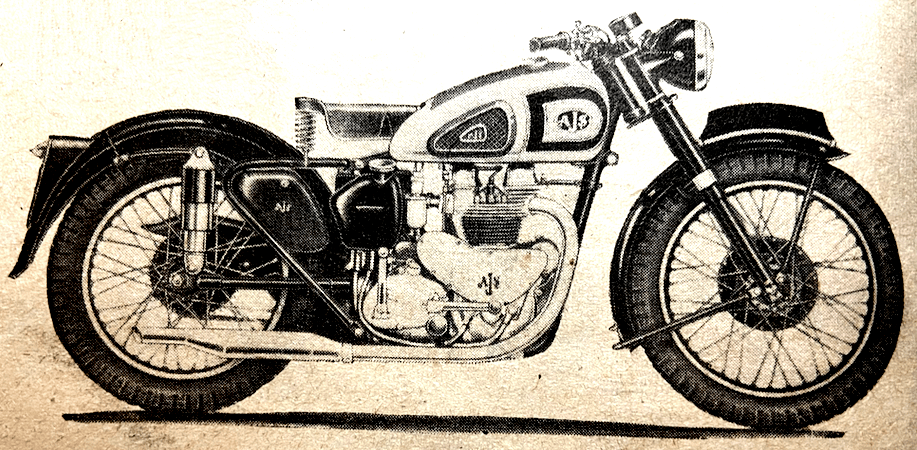

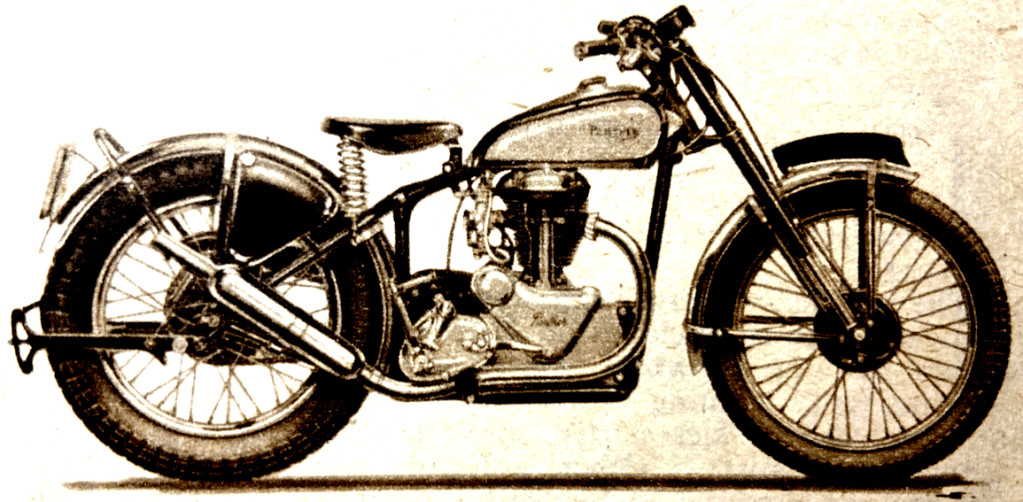

“‘BIKES OF TODAY are all very well,’ complain the traditionalists, ‘but they have no character—Yamahas and Suzukis, and shaft drive, and self-starters, and winkers; they cannot be called real motor cycles. Now, take an old B31 Beesa…Each enthusiast has his own reasons for looking back to the 1950s with a particular kind of affection. Japanese competition was then no more than a speck on the horizon, Germany and Italy were turning out some attractive machines, but above all it was the traditional British single and vertical twin which dominated the motor cycle scene, both at home and abroad. However, during the early 1950s, buying a new machine was not so simple as all that. The demand was certainly there and, on the face of it, Britain’s manufacturers should have been raking in fat profits. But those who are forever carping that British industry should have been investing more heavily in new equipment during this period, would be advised to take a closer look at the country’s economic situation. The struggles of the Second World War had left the nation in a sorry state, and the immediate need was to build up reserves of foreign currency. For that reason, factories both big and small were constantly being urged to export more and more of their production. Metals were in short supply, and stocks were only obtainable by flourishing a government permit—and, usually, such permits were granted only if the firm concerned could produce an order from an overseas customer. Nor were export markets easy to find, because often other countries would either refuse entry to British products or (as in the case of the USA) place a heavy import duty on them. There were quotas and trade agreements to be negotiated and honoured, and it was not really surprising that our factories should find their major overseas markets in the countries of the Commonwealth. Indeed, in 1950, the first year of this decade, Britain’s biggest customer for motor cycles was Australia. However, the American market was just beginning to move, thanks in some measure to the efforts of Edward Turner and the Triumph company. Over a very long period, American riders had grown accustomed to the oversize, overweight V-twins of their own industry, but wartime experience had shown them that bigness is not necessarily a virtue, and that there was a deal of enjoyment to be had from a relatively light, and vastly more manoeuvrable British machine. Nevertheless, the vast distances of the United States permitted bikes to run at higher sustained speeds than was possible in Britain’s crowded land, and it was this factor which led British factories to introduce such models as the 650cc Triumph Thunderbird, and the BSA Golden Flash of the same capacity. It might appear that every factory worthy of the name felt honour-bound to follow Triumph’s lead and include a vertical twin in its post-war range, but that is not strictly true because there were some firms striking out along individual lines—Douglas, for instance, with a 350cc transverse flat twin and torsion-bar springing, Sunbeam with an in-line, ohc twin and shaft final drive, and Velocette, casting aside its pre-war traditions and staking everything on a little water-cooled, side-valve twin in a pressed-steel frame. In the industry as a whole, there was a tendency towards grouping. Ariel and Triumph had long been linked under Jack Sangster’s banner, and now the giant BSA firm joined in, taking Sunbeam with it. The London-based AMC group, already makers of AJS and Matchless, added Francis-Barnett, then James. What with material shortages, international tariff problems. labour difficulties, and the continual demand for more bikes than they were able to produce, the factories just had not the resources available to cope. That is why, with the inevitable disruption a London Show would have caused, there was no major Earls Court Show in 1950… More and more firms were adopting rear springing, albeit plunger type instead of the full pivoted rear fork (although Triumph managed to get extra mileage out of their old rigid frames by adding a rear wheel which encompassed rudimentary springing within the hub). The traditional hearth-brazed lug frame was being ousted by the all-welded frame, due to advancements in steel-tube technology through wartime experience. In trials and scrambles, the big four-stroke single was pre-eminent, but whereas in earlier days competing machines were mainly roadsters stripped of lighting and equipped with suitably knobbly tyres, purpose-built competition bikes were now emerging…The time-honoured Magdyno, a combined magneto and dynamo that had originated in the early 1920s, was on its way out and, instead, the alternator (the rotor of which could be mounted directly on the engine shaft, so avoiding the necessity of providing a separate drive) was making headway. It was not all big stuff, of course. There had long existed a demand for a simple, ride-to-work lightweight, and in the course of any trip by (steam) train, nearly every signalbox along the way would be seen to have a small two-stroke, usually an Excelsior or a James, propped up against the outside stairway. Mostly these were much of a muchness, powered by reliable if none too exciting Villiers two-stroke units, but in 1948 the BSA Bantam had come upon the scene, initially for export only but later for general sale; the Bantam was a frank copy of the pre-war German DKW (as was the 125cc Royal Enfield ‘Flying Flea’, used initially by the Airborne Forces but continued into civilian production as the Model RE)…At the start of 1950, the British motor cyclist was still bedevilled by fuel rationing, but in June of that year came the welcome news that restrictions on private motoring were being lifted at last. True, branded fuel had yet to return, and all that the pumps contained was the dreaded 75-octane ‘Pool’, but at least coupons were to be torn up and the enthusiast could make the most of the summer — always bearing in mind that at 3s (I5p) a gallon, it paid to check the carburettor for economy!”

Now Bob’s set the scene, here’s another treat—Torrens’ review of his year’s favourite bikes . OK, he rode them in 1949 but it was published in the first issue of 1950 and pedantry can be taken to far. In any case, it’s a damned good read. So, Torrens (nom de plume of The Motor Cycle’s editor Arthur Bourne), you have the floor.

“TURKEY, PLUM PUDDING, a riotous walk with the children, for their good and mine—then twenty minutes of purely personal heaven: yes, my 1950 mount had arrived. Norman Vanhouse, from the factory, who had been putting in road miles on it, delivered it on trade number plates on the Thursday afternoon before Christmas. The next day the insurance cover note was obtained; on the following one, Christmas Eve, I presented myself at the local licensing office and on Christinas Day I was ready to take to the road—as soon as a father’s duties were o’er. Did I have just a little run on the machine beforehand—round the garden or out a tone gate and in at the other? No Didn’t I start the engine just to listen to it and to dream? No! I hate starting up an engine unless it is going to warm up properly. In any case, why nibble away one’s pleasure—why not a proper bite, such as a run round a neighbouring 8-mile triangle would give me? But this article is not about a single machine. During 1949 the number of motor cycles I have been fortunate enough to ride has been large—so many that here I can only dwell on ten or a dozen. Some, as usual, cannot be dwelt upon, in that they were one-off experimental mounts which may or may not reach the market. No doubt it is a sign of the times, hut. the majority of these were of small engine capacity. In the year that has just passed there was not a single water-cooled

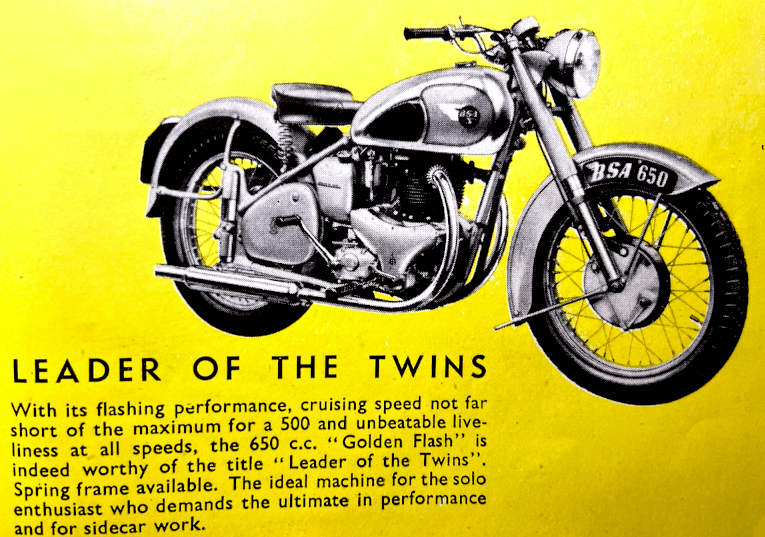

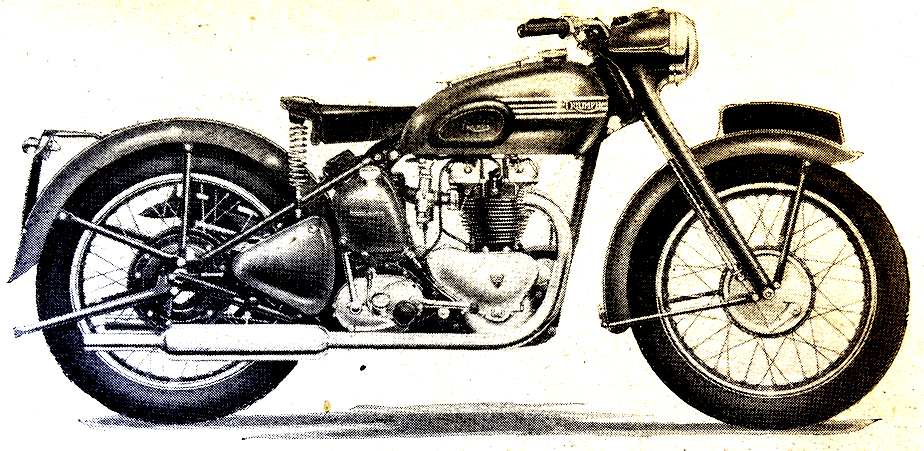

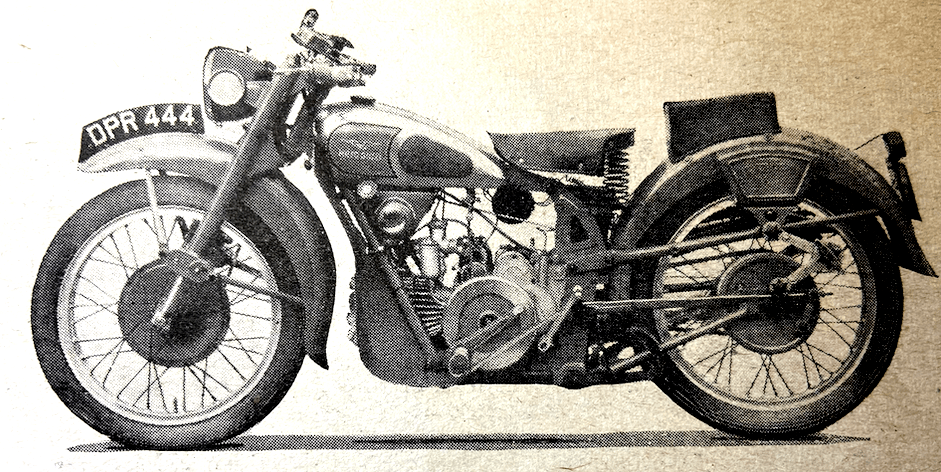

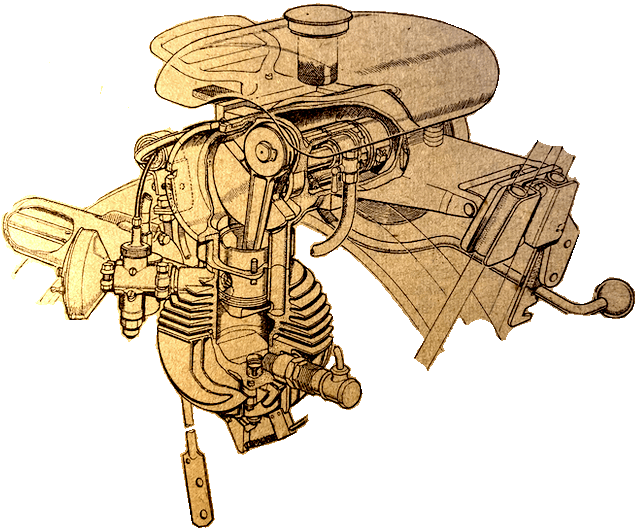

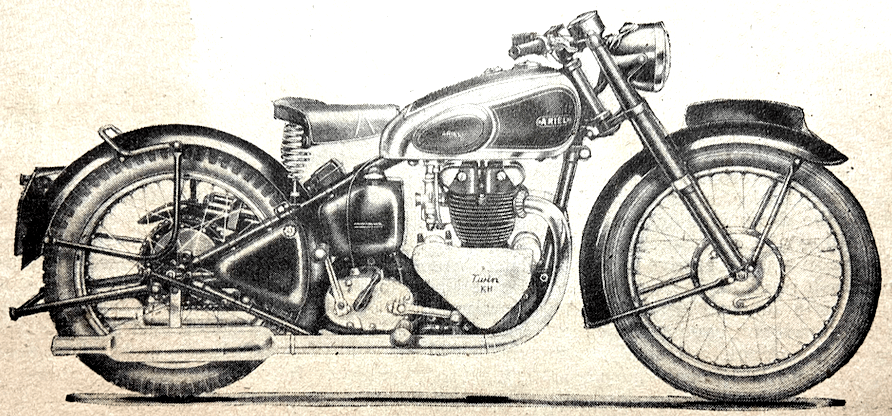

four, nor a three, nor any specially thrilling prototype other than the two new 650cc vertical twins, the BSA and the Triumph. Shall we start with these? In each case the machine I rode was a prototype—in other words, a pre-production mount. The Triumph was ridden many months ago: before the TT, as a matter of fact, and I wonder how many of those who visited the Isle of Man spotted that there was anything unusual about the machine a member of the Triumph staff was using. Some people, I know, were a little taken aback by the effortless speed of the machine, and especially by the acceleration, but apparently dismissed the matter with the thought, ‘A works’ man, a works’ mount!’ My visit to Meriden to try the machine was on a day of lashing rain. Roads were awash, and the thin leather gloves I put on for the test, in order to have maximum feel, were wet through in minutes. Hence the conditions were just those calculated to damp one’s enthusiasm. I was enthralled by the performance of the machine. It seemed unbelievable that the capacity of the engine was-merely 150cc more than that of the Speed Twin and the Tiger 100, and therefore not quite a third greater. This machine had what I have always missed with the 500cc twins—lusty power at low revolutions and fuss-less running at high speeds. There was a beefy sort of performance: the machine seemed to hunch itself under one as the twistgrip was opened and gathered gait in very much the manner of a really good big-twin. And it was not that the engine was on a 500cc type of gear ratio. One of the things I had been asked to ponder was the gearing. I came back from my first run with the remark, ‘The conditions are not such that one can be certain, but the impression I have gained is that you can gear appreciably higher.’ I went on to touch upon the machine being destined for use, among other things, on fast, straight highways and upon the joy of a machine tick-tocking along in the seventies and eighties. Tyrell Smith and his experimental staff managed to find a spare 25T engine sprocket—one left over from a Grand Prix model, I believe—and in a very few minutes had it in place and the machine ready for the road again. Twenty miles or more were covered. Although top gear was now around 4.3 to 1, the machine was still flexible, the acceleration was still a thrill, and there was even more effortless mile-eating, or so it seemed to me under the conditions of wind and rain. Mr Turner thought that, for home at least, a gear half way between the two would probably be best. He and members of his staff would take the machine out under better conditions which would give a fairer test. As you know, the 25T sprocket was used for the Montlhéry tests in which the three 650s averaged over 92mph for 500 miles and is, I gather, available, though the slightly lower gear is standard for this country. I know which set of ratios I would prefer, but then I have no objection to using the gear box, which brings me to the fact that the new gear box is one that very definitely invites use. Good though, folk maintain, the gear change has been in the past, this is far better. My main theme before setting off for London and home was, ‘If they are anything like this prototype, the machines are going to be the most popular Triumphs ever.’ It is not just a case of the new model having a little something that the others in the range have not got; there is a whale of a difference. There are many extra horses, the low-speed torque is magnificent, and the weight of the machine is within a pound or two of that of the five-hundreds. Eulogistic? It is supposed to be a bad thing for a journalist to discuss two very similar machines, each from a different factory, in the same article, but here, were I worried about it or not, there is no option. The new BSA is, of course, also of 650cc. It is new in looks, in its power unit and in its gear box. The gear ratio pulled is in the region of 4.3 to 1. The impression the machine gave me was that, if anything, it was undergeared, such are the pulling powers of the engine. I have ridden many BSAs, but never one I have liked so much as this newcomer. What were those figures Mr Hopwood gave—17bhp at 2,500rpm and some 34bhp at 4,700rpm. I ambled out of Birmingham using the flexibility to the full, dropping down at times to 12-14mph in top and then gently opening up. That it was possible to use such low top-gear speeds, particularly in view of the ratio being so high, was interesting.

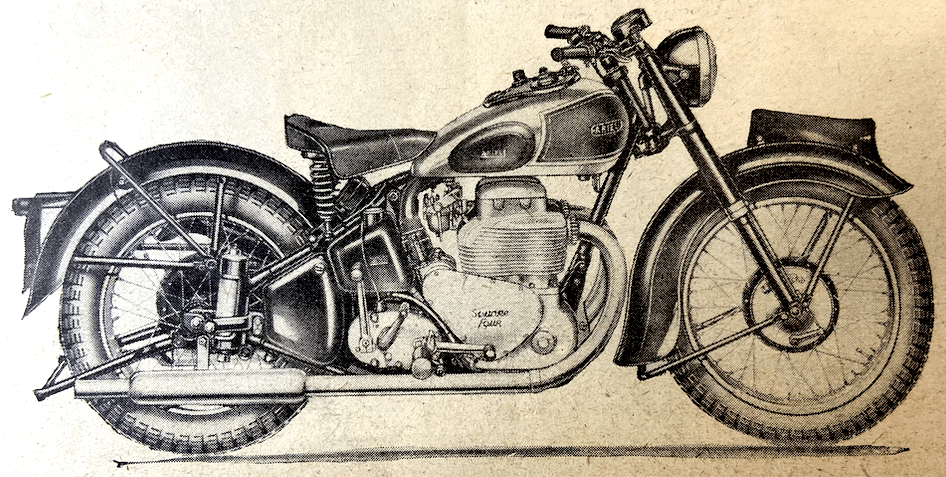

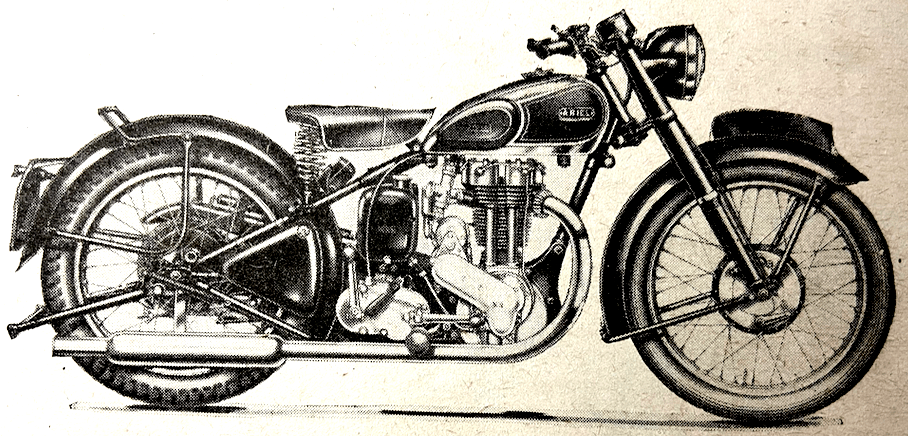

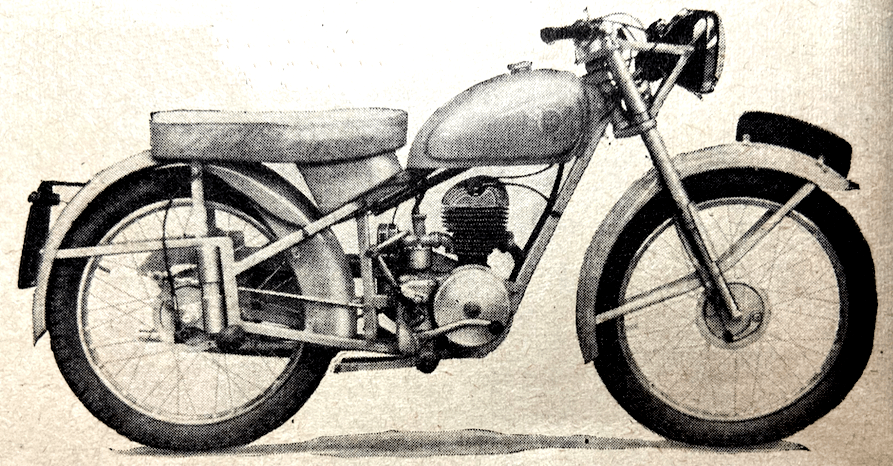

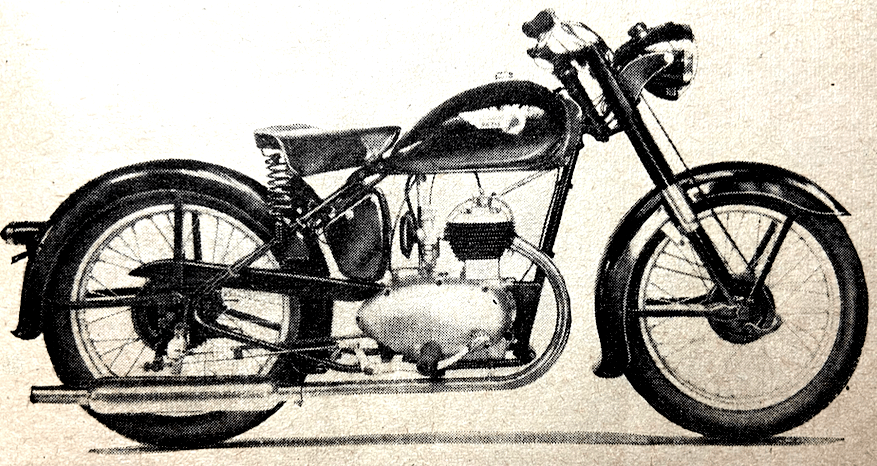

Good traffic manners, I always feel, count for much. Naturally, the opening up had to be velvety, but at anything above about 20mph the grip could be flicked open—the results were satisfying, very. At 60 and 70mph the power still came in with a zestful rush. With this new model, BSAs have an ultra-fast machine with superb road manners. One can spend nearly all the time in top gear, drive like the perfect little gentleman, and yet have what the average being would regard as a super-sports performance. If, however, in the mood for something in the form of hyper-sports, then one has only to make use of the new gear box, the gear change of which I can best liken to that of a close-ratio box on a TT winner. On the stopping side there is a new, large front brake. The riding position is really good, and I liked the handling of this taut-feeling, spring-frame mount. The weight of the machine, I was told, is not more than some 7lb greater than that of the 500cc twin. Thus one has a 650 with very much the cornering characteristics of a 500. According to my impressions of this prototype, here is a machine to thrill and to delight, a joy to the sporting rider and a godsend to the sidecar enthusiast—a very fine motor cycle. You will note that in neither case, that of the new Triumphs or the now BSA, have I made any criticism. The fact is that on my return to the respective factories I had no major criticism to offer. The machines proved far better than I dared to hope, and both appeal to me immensely as potential mounts for my own use. All the points I raised were of a minor character, and two at least were of types to concern the individual machine. While at the factory I had a ride on a spring-frame 125cc BSA Bantam that was undergoing mileage test. It confirmed a view I have held for some time: that rear-springing is very well worth while on an ultra-lightweight. It eliminates back-wheel hammer. Cast your mind back to the last time you saw a rigid-frame 125 on cobblestones; do you remember how the back wheel went along in a patter, spending, it seemed, half the time in the air? This jarring, surely, is the main reason why these little machines become tiring to ride on a long journey? As a rule, I start to get stiff after 40 or 50 miles and to yearn to stretch my legs, yet on bigger machines my practice is to cover the first 100 or 120 miles non-stop and, unless the riding position be a poor one, the thought never occurs that there could be any stiffness. With the Bantam’s rear-springing, this lolloping of the back wheel was noticeably absent—yes, on Birmingham’s roads. In brief, the suspension turns the machine into a really comfortable long-distance roadster. For this I would willingly pay much more than the extra £5 that is demanded—£6 7s in this country, with its Purchase Tax. Harking back to the new 650cc twins, why, if I was so pleased with the Triumph I rode way back in April and had a shrewd idea that the BSA was framing well, did I place an order for a 1950 model 1,000cc Ariel Four? The answer lies in the performance characteristics of a good four-cylinder machine—the droning, zooming power and the greater responsiveness to throttle movement that results from one’s having four cylinders instead of two. I always feel that it is easier to ride neatly with a multi, and that handling such a machine calls for less effort and is less tiring. Today, with the high power/weight ratios of the new 650s, there cannot be a lot of difference in the manner in which hills are gobbled up or in the way the trio dart forward when the throttle is twirled, but having covered roughly 100,000 miles on fours, I like them and prefer them! I was not looking forward to riding the new Ariel with quite the thrilling anticipation you might expect. My old one, HPG 601, has given me 50,000 magnificent miles, and I felt that the new upstart could hardly better the faithful service of the old stager. Moreover, there was every reason to anticipate that the latter would continue to give this year

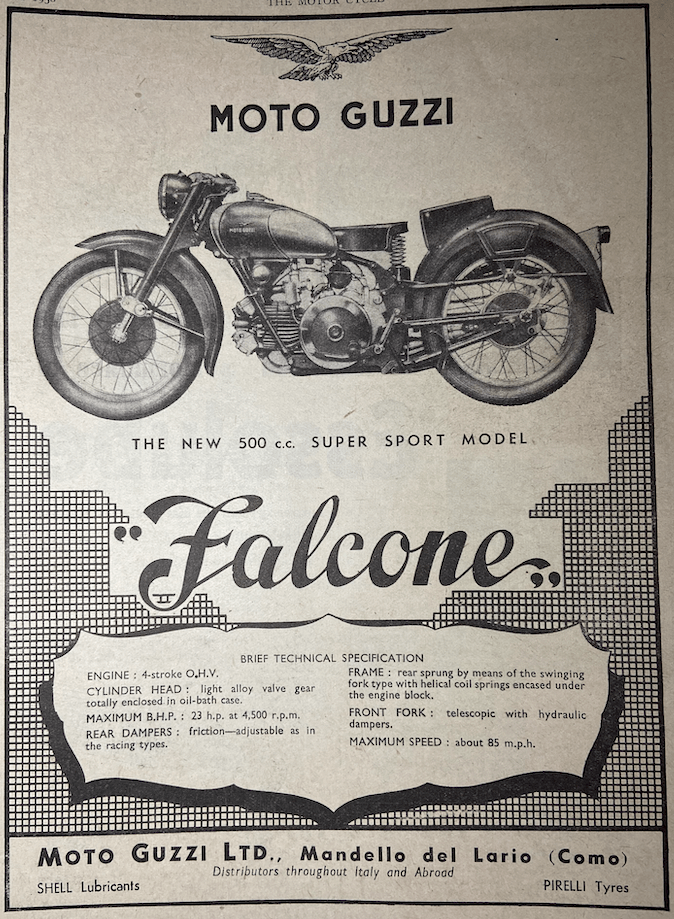

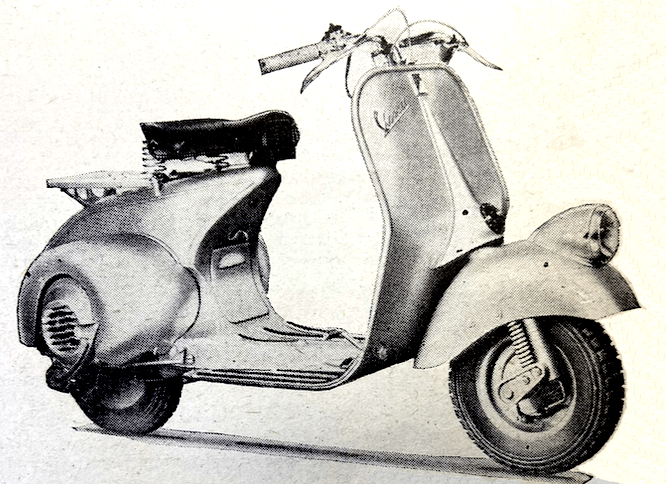

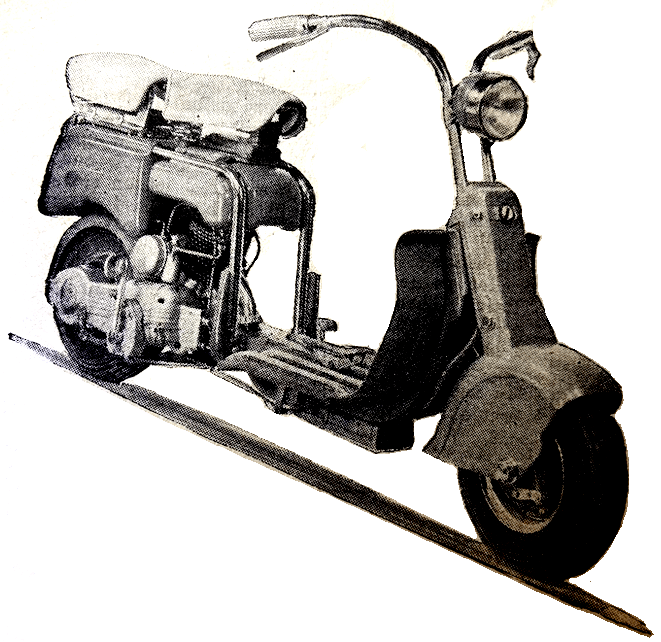

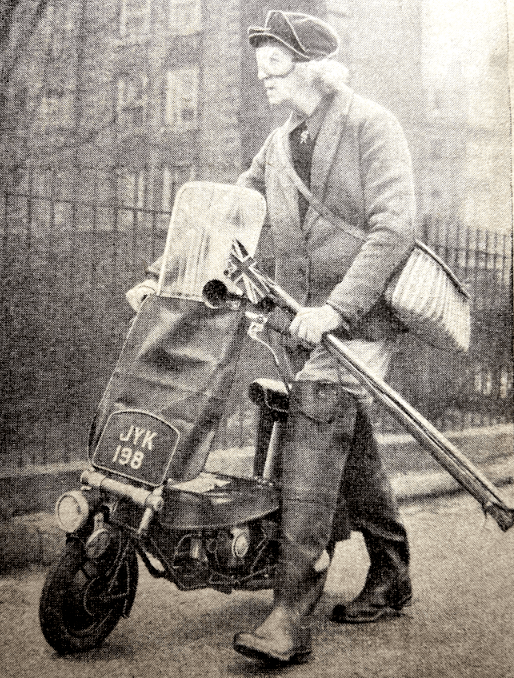

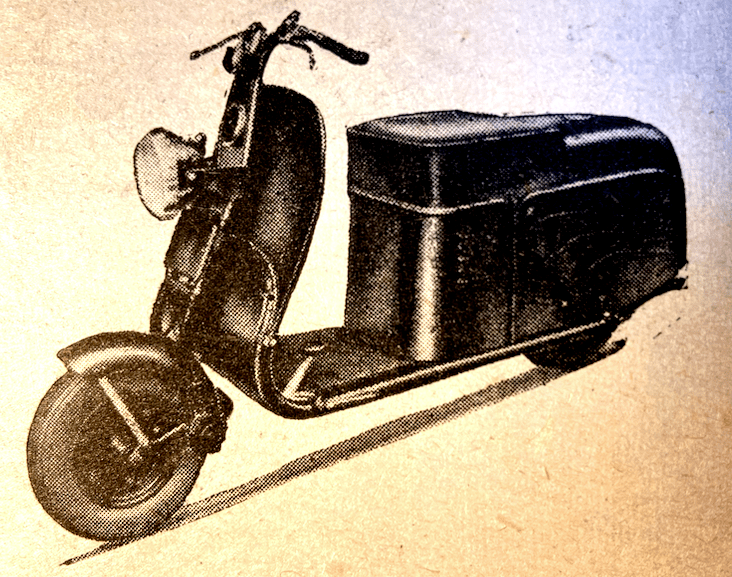

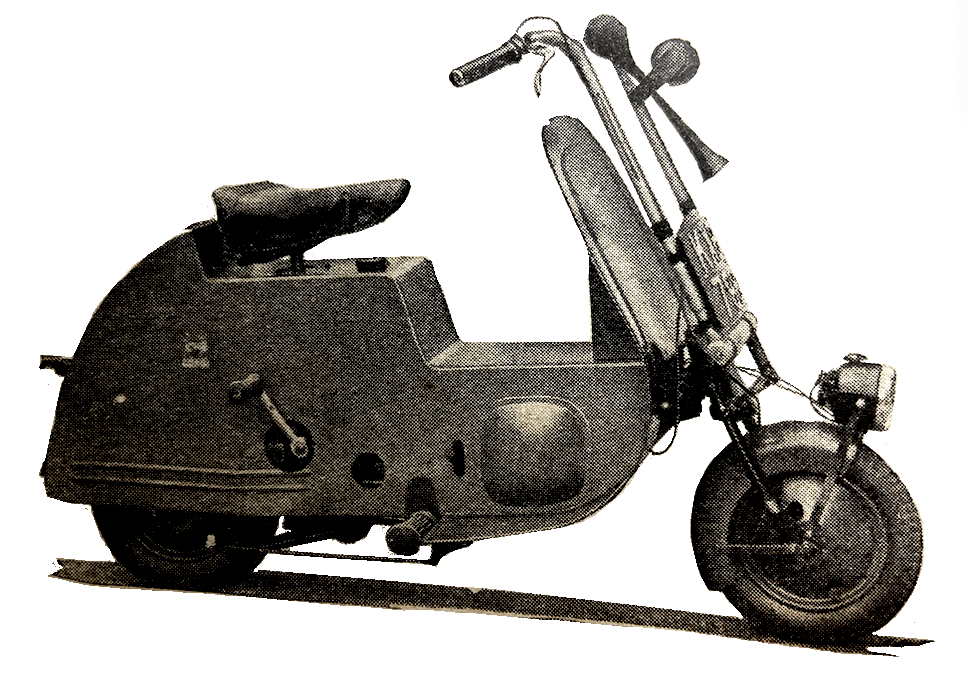

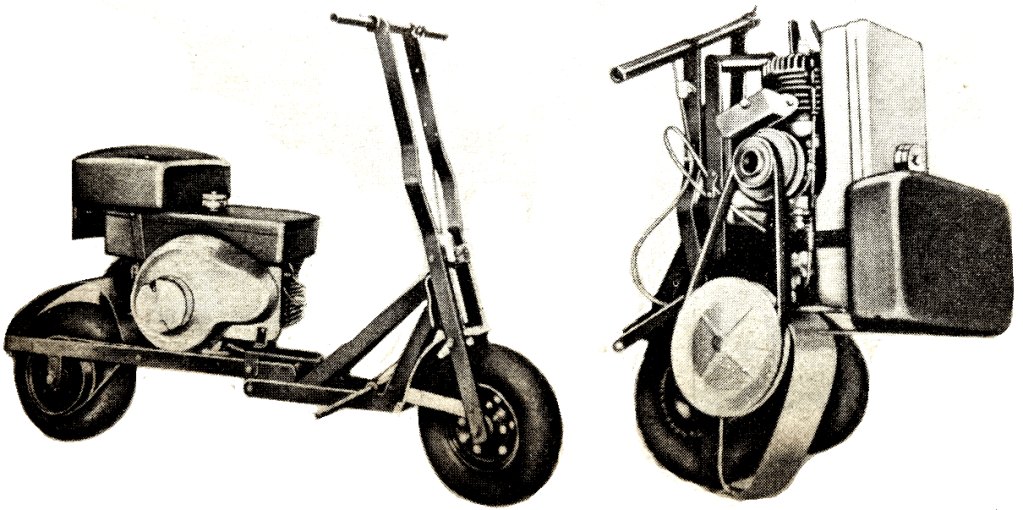

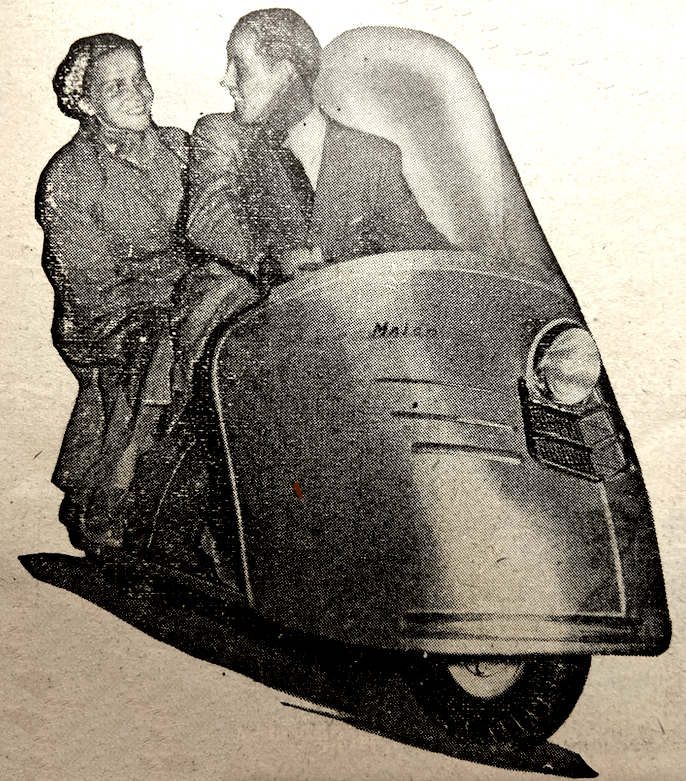

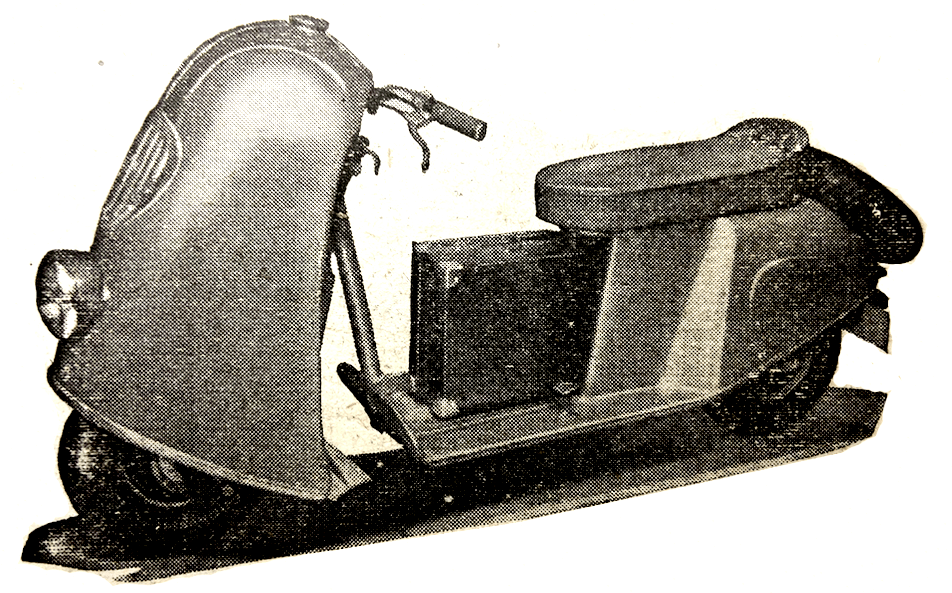

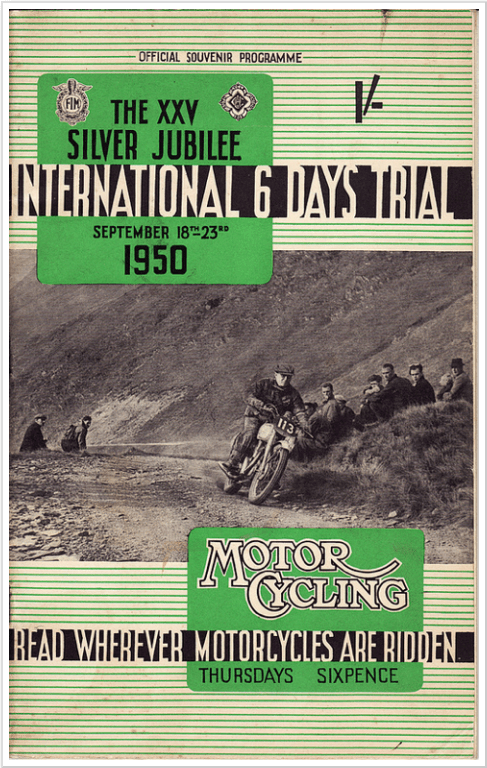

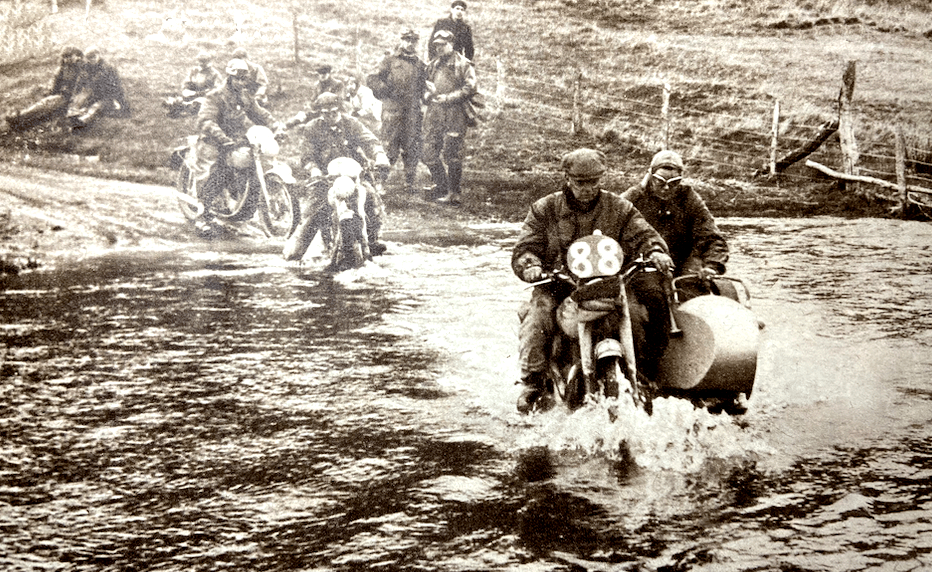

in, and year out reliability. Also, would the new mount do its 60mpg at batting speeds and even 70 at quite a fair gait—yes, and 52mpg when averaging a full 40mph with sidecar! I like the reduced weight of the new model compared with the old one, which weighs some 500lb. The light-alloy cylinder block and head casting, with the changes on the ignition and lighting side, have saved some 40 or 50lb, and make the machine much more handleable. First impressions are good. At the time I write this I have covered only about 60 miles, and the majority of those have been in traffic. However, before this article is published, all being well, the total will be around 500, since I am about to setoff for the Exeter Trial. That, with the roadwork put in by the factory, will bring the mileage to over 1,000. Already I feel, very definitely, that I am making a change for the better and I am looking forward to the ‘Exeter’ with thrilled anticipation. If, as I trust, there are no hints of snow and ice, such as has been the Exeterites lot on so many occasions, my sidecar will not be hitched on and I shall waft to and from the West Country in solo blessedness. However, more of the new pet anon. Let us now hark back to May, when I visited Italy. There I rode a 250cc Airone Guzzi, such as we tested on English roads a week or two ago. I had the machine on the twisting, roughish highways near the Guzzi factory. I was much impressed by the TT-machine-like handling of this spring-frame mount—the clean-cut cornering and the manner in which the suspension smoothed out the Italian hummocky highways. The gear change on the machine I rode was apparently better than that of the mount we have just tested; it was very good indeed, and I gave many marks to a riding position that in the old days we should have referred to as ‘semi-TT’. The machine made me wonder whether we over here are altogether wise in not doing more with ohv 250s. The Airone was a lusty performer, with liveliness and speed capabilities fully equal to the needs of many of the sporting-rider class in this country, and it does not give a small-machine feel. Over in Italy I also rode a Vespa. I had tried a Lambretta earlier and, as it happens, have ridden one again only a few months ago. I can well understand the Italians’ liking for these two machines. The general rule in Italy is for them to be used as potter-buses—in the case of the Vespa there may be father at the handlebars, and mother, plus at least one offspring, on the back. In the last International Six Days’ Trial in Italy the machines were batted at astounding speeds, but the populace, even though they are to be seen touring the mountains, seldom travel fast. The state of the roads is one reason. Comfort sets the pace—comfort and steering qualities. Here we are luckier with our road conditions, and I think such mounts will make an appeal for pottering. Larger-diameter wheels would be a big improvement, but that would mean larger machines, greater weight and, maybe, quite wholesale departures from the present conception. Over the next year or two, developments in the so-called scooter field should be interesting, and they may have their effect on the trend of motor cycle design. It has been my good fortune, too, to try various German productions. How I wish that the new 500cc transverse-twin, shaft-drive BMW could have been numbered among them! Perhaps in 1950…What I do know is that my

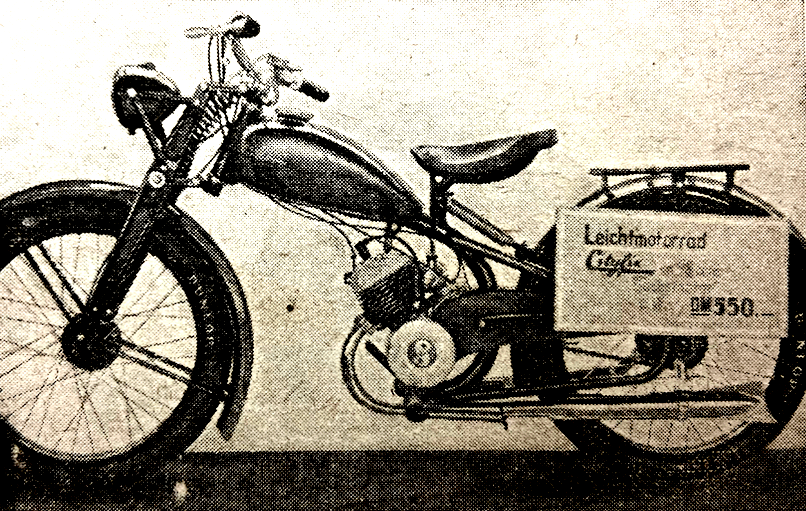

chief criticism of past BMWs has been eliminated: the gear change has been greatly improved. I tend to harp on gear changes, because I believe we had lost our standards—had ceased to realise what a good gear change is. Now, thank goodness, there are signs of a return to gear boxes which you can flick from one gear to another without a fraction’s pause, without sound—yes, without- the need for any skill in mating engine revs with road speed. You could not go wrong with the old Sturmey-Archer gear boxes (not as regards gear engagement), the Norton four-speed box which the late Arthur Carroll designed, the three-speed box fitted to the 550cc SD Triumph, and a small host of others. Our gear changes were the envy at all and until now they have mostly become worse and worse, unknown to and unrealised by the majority of riders of to-day. Believe it or not, on the day when the Norton directors and Major Barnsdale, who was on the Sturmey-Archer board. were discussing whether Sturmeys would supply Nortons with the Carroll box or the then new Sturmey one, and I, happening to arrive at Nortons that day, was asked to test one against the other, I used the hand changes of the four-speed boxes like pump handles, leaving the poor Norton Big Fours on full throttle and the clutch severely alone. Even with this vile form of test—one thought unto destruction—the gears in-variably slid into mesh. Of course, Germany over the past few years—indeed, until very recently—has been forced to concentrate upon small machines, nearly all of them two-strokes. There have been scores, if, not hundreds, of races for such machines. A result of this concentration, to judge from models I have ridden, is that a lot of knowledge has been gained. Pre-war there were no small two-stroke engines to equal those of the DKW made under the then Schnürle patents—the world apparently agrees having regard to the many two-strokes that now have this form of porting—but today still better results are being achieved by some factories if samples I have ridden are a fair criterion. Good for them! One over-the-water machine I tried recently was an almost brand-new Indian twin of 440cc. This is a vertical-twin much on the general lines of those made in Great Britain, but with light-alloy cylinder and head castings and other engine features which seem to smack

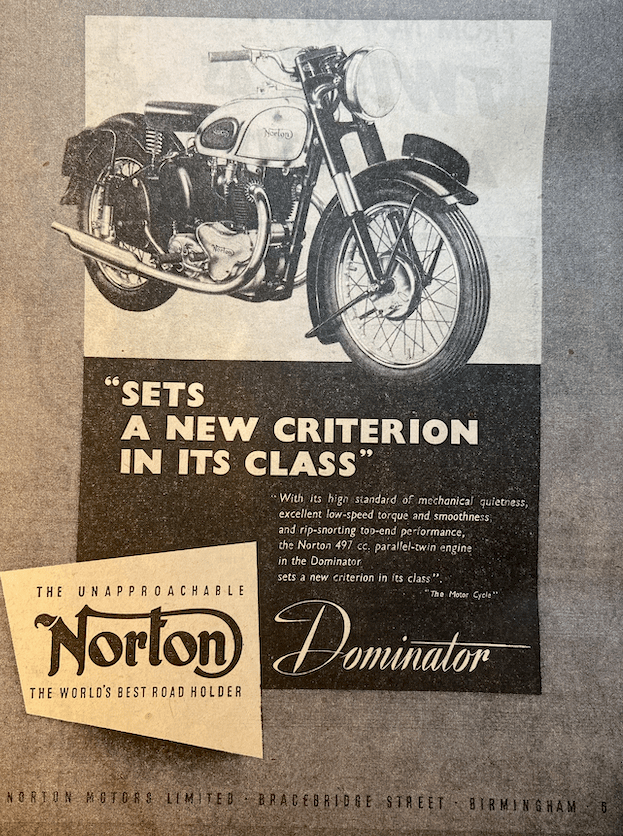

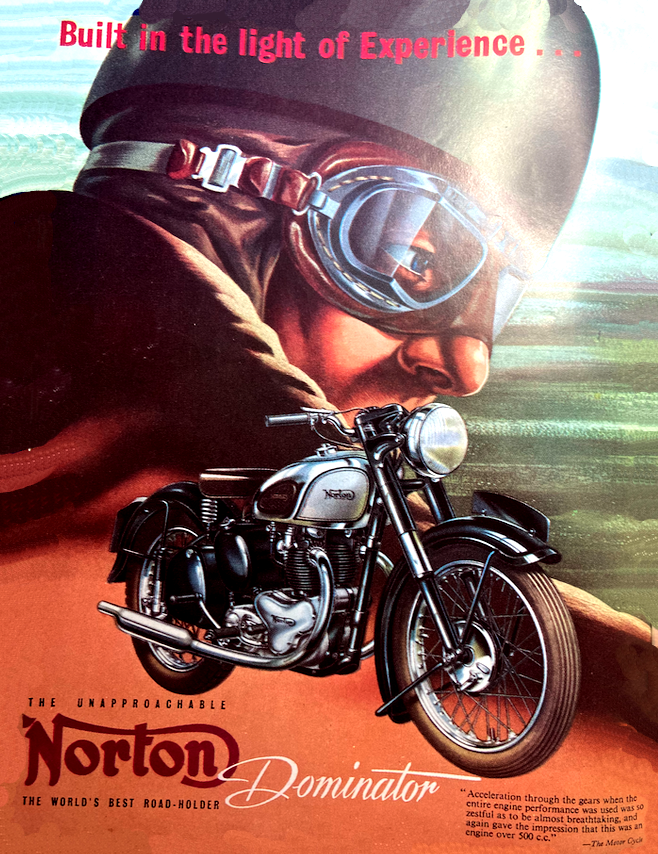

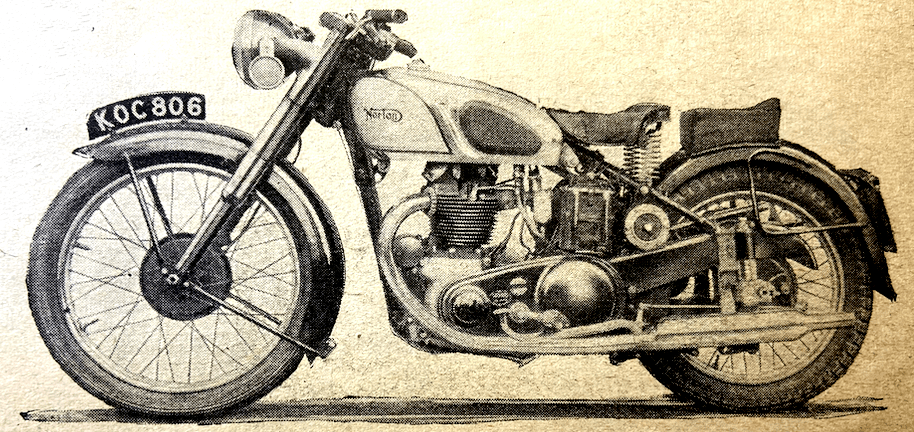

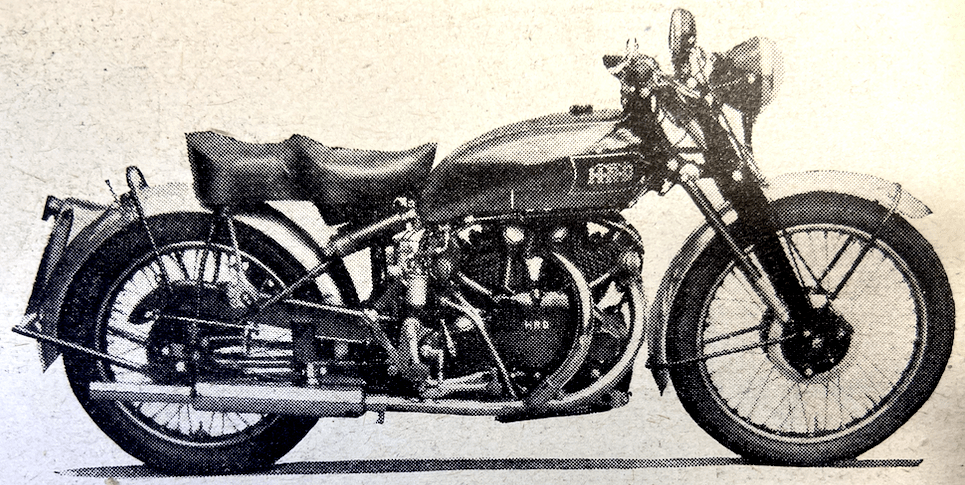

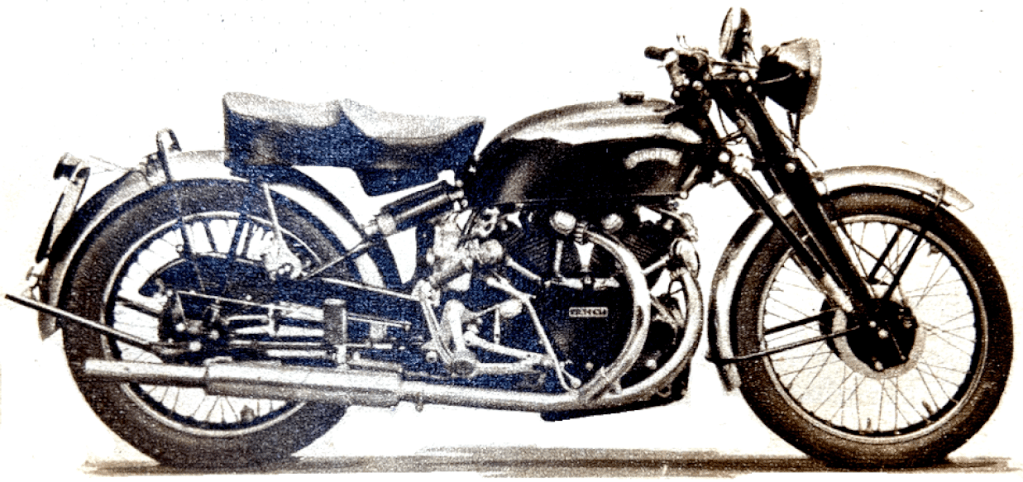

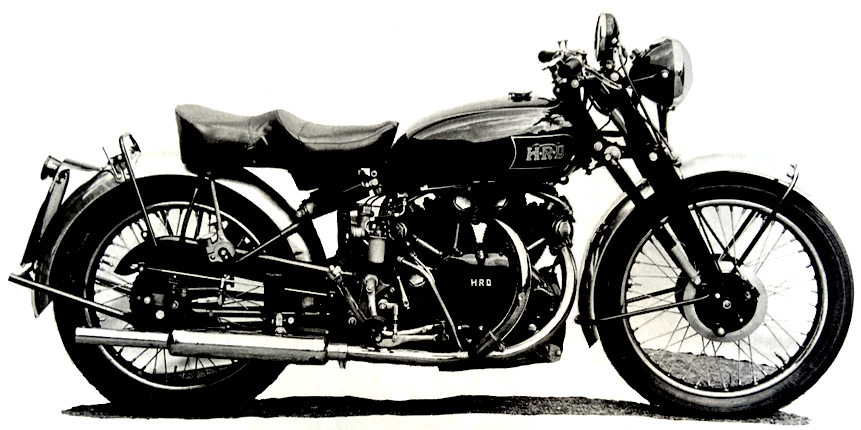

more of the aircraft than the motor cycle industry. Owing largely, no doubt, to the light alloy. in the upper half, the engine was noisier mechanically than is usual with a vertical-twin. The engine, however, developed excellent power for its cc. Because of our poor-quality petrol it was necessary to use the gear box a lot in order to keep pinking within bounds—it was hardly designed for ‘pool’! The gear change proved so-so, but I found that the handling of the machine from the bicycle angle was good—a lithe, lively mount. Now to a very different machine, the latest 1,000cc Vincent Black Shadow, the Series C. I took out the machine we had for road test in order to try the Girdraulic front fork and the hydraulically damped rear-springing. A year ago—as a result of a Black Shadow produced before these improvements came into being—I was critical of the suspension; it might be quite all right on British roads, but could be a limiting factor elsewhere. I was delighted, therefore, to find the vast improvement effected; it puts a very remarkable machine still more firmly on a plane of its own. The vertical-twin Norton I rode early in the year was a pre-production prototype, a good machine which proved reliable and thoroughly sound, but not sensational. Well, we have just had a road test of one of the Dominators that have emerged from the then chrysalis; need I say more? I am not to state that the machine is in a class of its own, because nowadays there is a number of good 500cc vertical-twins, but I do maintain it will be very difficult to find a better mount of its type. And so I near the end of probably the least critical of any ‘What I Rode’ article I have ever written. Of their types, all the machines I have touched upon have been really good—a far, far better series of mounts than I have had in any previous year. That is not to suggest that we can all sit back with the pleasant thought that everything in the garden is lovely. As an idealist I know that the majority of designers have still a long way to go in developing suspension, that it is high time the seating side was the subject of a few brainwaves, that transmission shock-absorbers are too frequently inefficient, and that if some makes have hairline steering at all speeds, it should be possible for all to be endowed with it…but I do say that my many happy miles over the past year suggest that there has been some very worthwhile progress.”

“UNDER THE NEW REGULATIONS at present being drafted, all drivers of vehicles will have precedence over pedestrians at crossings where traffic lights or a policeman’s signals are in favour of vehicular traffic. This is welcome news. On the other hand, why has the Ministry delayed so long in drafting a simple amendment to a somewhat ambiguous law?”

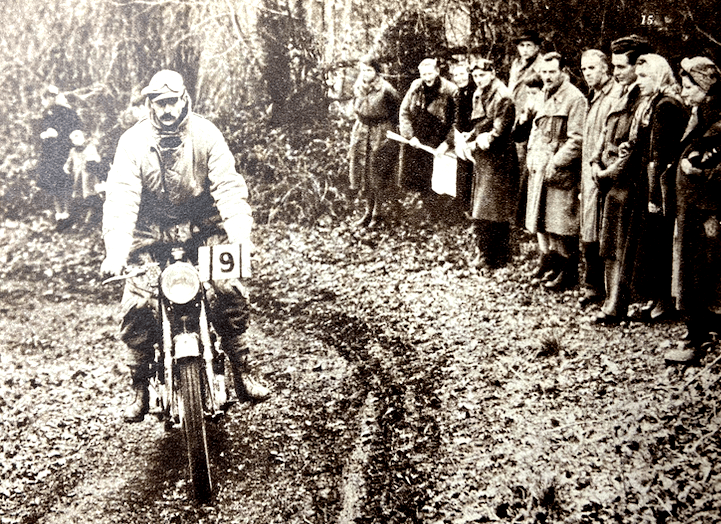

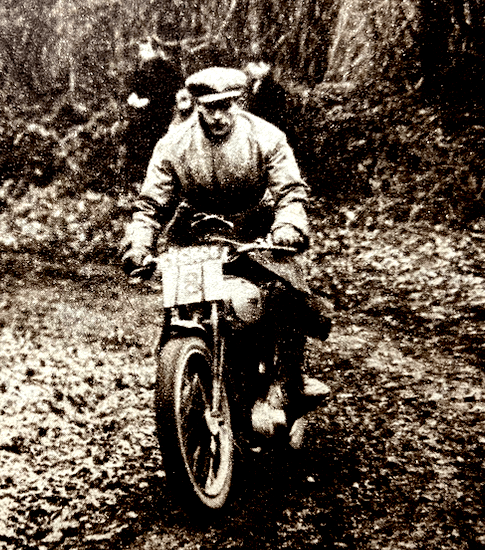

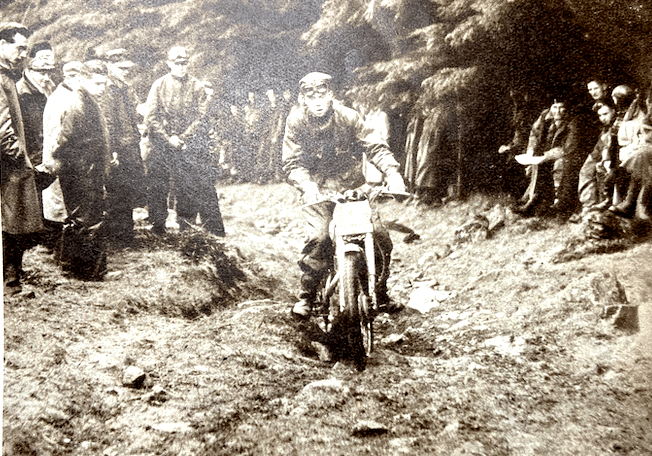

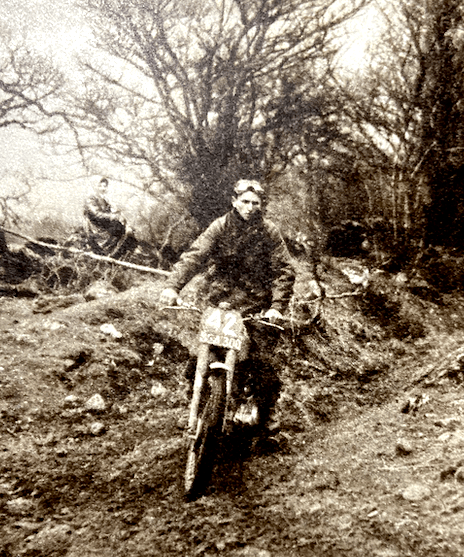

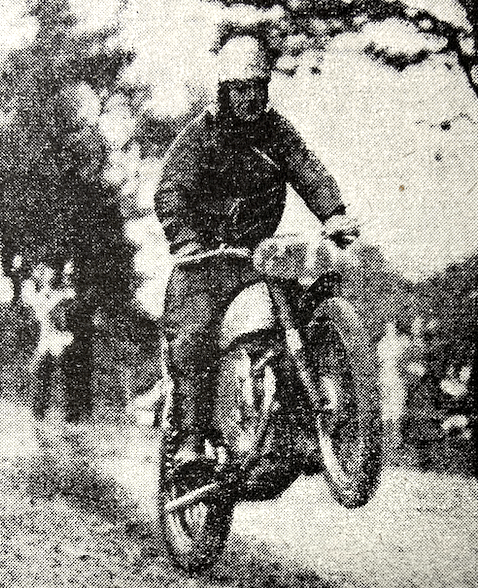

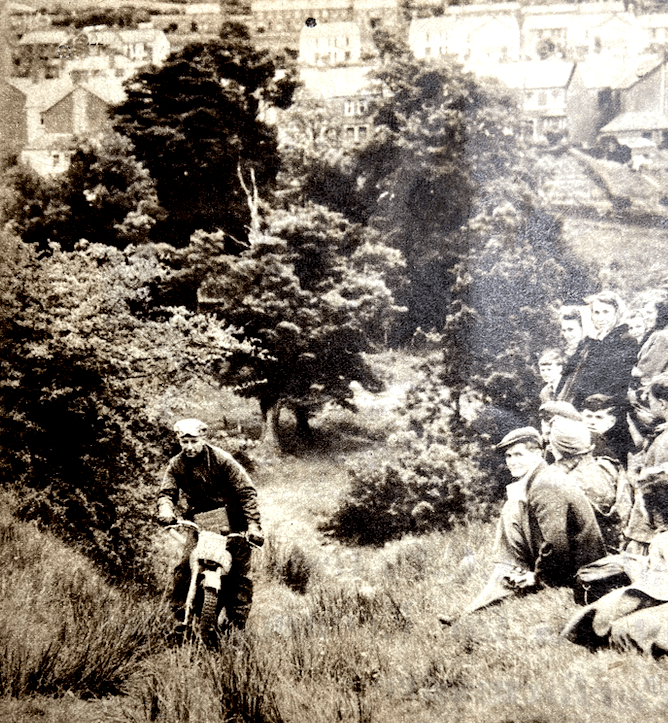

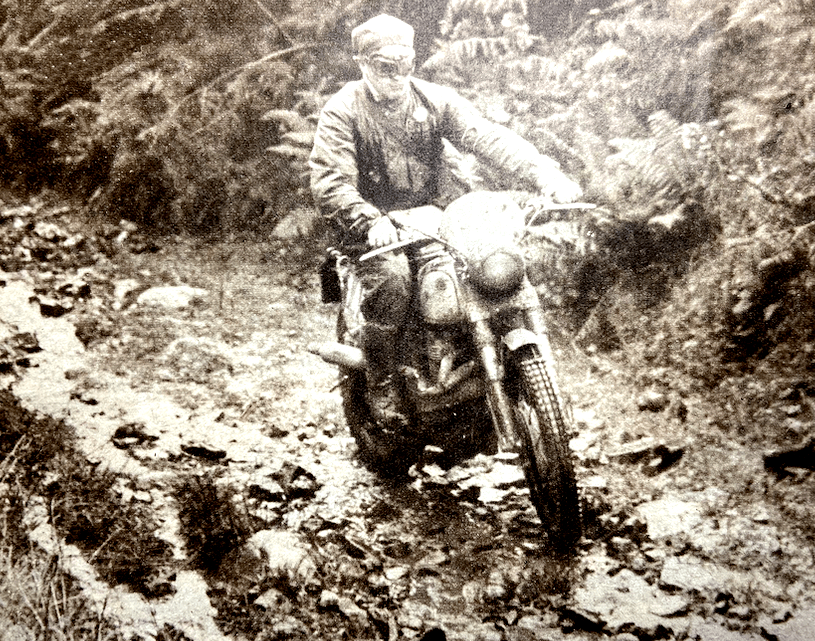

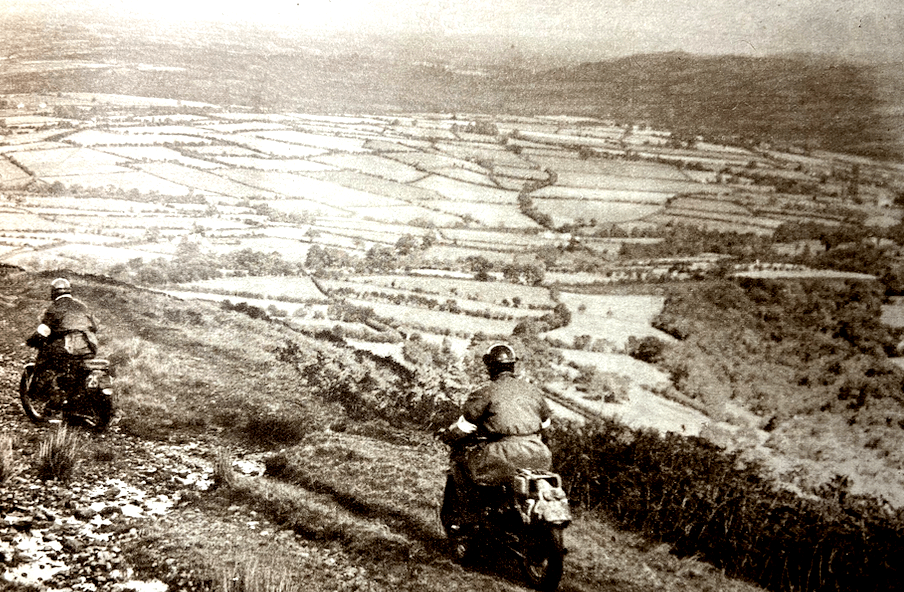

“THAT TRIALS RIDING makes a good road rider better is an axiom which is worth closer consideration than it receives. At present, only a tiny percentage of Great Britain’s 600,000 motor cyclists gains the added skill that results from tackling rough terrain under competitive conditions. Any suggestion of additional events to cater for the road man with an ordinary motor cycle can bring the retort that there are already too many trials and that these trials, particularly in the south, have been attracting an almost impossibly large entry. We would, however, underline the recent statements that trials are in their own particular rut. How many people fully appreciate the vicious circle that began around 1929—that special machines were developed to defeat the wiles of trials organisers, the latter turned the tables, and machines, in due course, were expressly marketed for trials with features and attributes designed to render the ‘impossible’ easy? It is true that, in between times, trials organisers’ hands were strengthened by the ban on competition tyres, though this was largely fortuitous and arose from the fact that either the trials world allegedly set its house in order or trials would be outlawed in the same way that racing on the public highway had been banned. To-day, except for MCC events, the majority of trials place a high premium on ownership of a special trials mount. A few clubs organise events for novices, but hardly any club committees think in terms of trials that give the ordinary-rider of an ordinary motor cycle an afternoon’s fun on some local rough ground well within the compass of such a mount.”

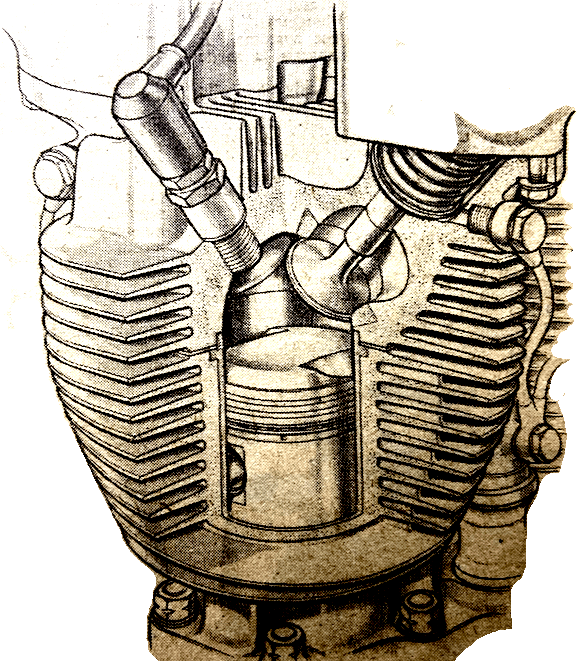

MANY RIDERS WILL AGREE that, notwithstanding the theoretical impossibility of balancing the simple single-cylinder engine, there are to-day many motor cycle engines of this type which are extraordinarily free from vibration at all normally used revolutions. The so-called vertical-twin, comprising two single-cylinder engines with a common crankshaft, is generally even smoother in operation. The horizontally opposed twin has perfect balance except for the small couple resulting from the offset of the cylinders. In short, the old bogy of engine vibration has, by and large, been killed. The qualification is included in the last sentence be-cause in some classes of engine there is a big difference between the best balanced units and certain of the others. There are even cases where engines are not better balanced than in pre-war days, but worse. It is well to realise how high the standards are with the best engines. The achievements of one designer should be within the range of all.”

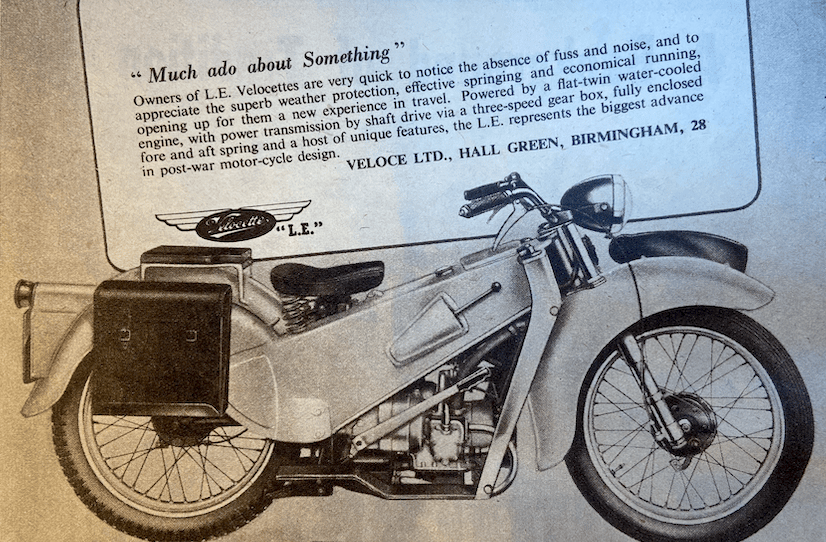

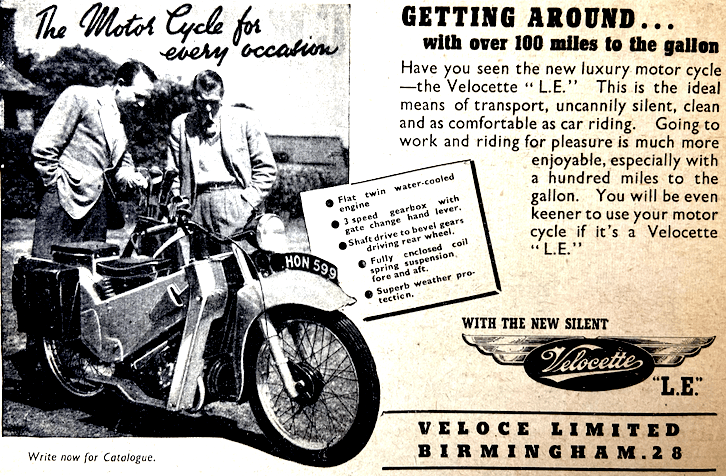

“A FEW DAYS AGO I had the pleasure of a ride on an LE Velocette. I have now an entirely new conception of motor cycling. This machine sets a standard by which all others should be assessed. The engine started effortlessly by a hand lever, ticked over silently, and took up the load in bottom gear sweetly and smoothly. The gears operated easily, and the machine floated over Liverpool roads with no reminder of the cobbles and rails. Hands-off steering is safe and true, and at 30mph in top I proceeded without noticeable sound. The machine is a demonstration LE at Victor Horsmans. By now it has been ridden by dozens of prospective buyers. The brake and clutch cables required adjustment, and the footboard could have been three inches longer for the convenience of a pillion rider—but these are trifling points. The LE Velocette is a remarkable motor cycle.

WILF JONES, Little Nelson, Wirral.”

“AN INAUGURAL RALLY with the object of starting a club for owners of LE Velocettes will be held on May 14 at Newlands Corner, near Guildford, Surrey. The meeting time is 3pm, and all owners of LEs are cordially invited.”

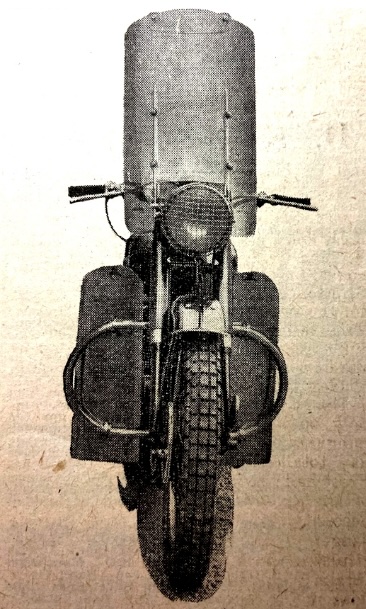

“OUR LEADING ARTICLE of December 8 drew much-needed attention to the defects of too many mudguard layouts. One reader snorted when I showed it to him in proof. ‘A car gets just as dirty,’ he declaimed; ‘look at a Rolls after a dirty run! Its flanks will be plastered to a height of a couple of feet, and you could plant seedlings on its stem far higher up than that!’ True! But we must separate the allied problems of machine-cleanliness’ and ‘rider-cleanliness’. The Rolls may need a long wash, but its occupants can step out spotless. With standard mudguarding a motor cyclist after a dirty run over mixed roads will usually be mud-plastered about knee-high on his legs, and almost neck-high on his back. His nether portions can be kept clean by adding legshields and perhaps some form of footboard (note the LE Velocette). His back could be kept clean, but few standard guards will effect this. No method of keeping the machine clean is known—or even dreamt of. Blow-back off the front guard; mud-fling off the front tyre; suck-back due to the vacuum behind the rider’s body; mud-fling from the rear tyre: guards can reduce these, but nothing can eliminate them. Finally, the side-fling from every vehicle which he passes at short range will foul both his model and his person, no matter how efficient design might become. For he sits low in relation to the road…little research has been definitely focused on this mud nuisance. Even the best standard guards could probably be improved by intelligent and vigorous designing effort without cluttering up the model overmuch. Ease of cleaning is a more promising ideal than averting all the mud from the model. No rider will ever be able to step off a model fit for a ballroom or a fashionable restaurant, so special clothing will always be a ‘must’ in bad weather (unless we accept a Roe monocar with a convertible lid—which we shan’t). But it is one thing to get moderately dirty and quite another to collect an appreciable amount of damp filth distributed over legs and back. Finally, any solution should surely be applied to the lightweights, whose buyers desire protection far more than the roadburners.”—Ixion

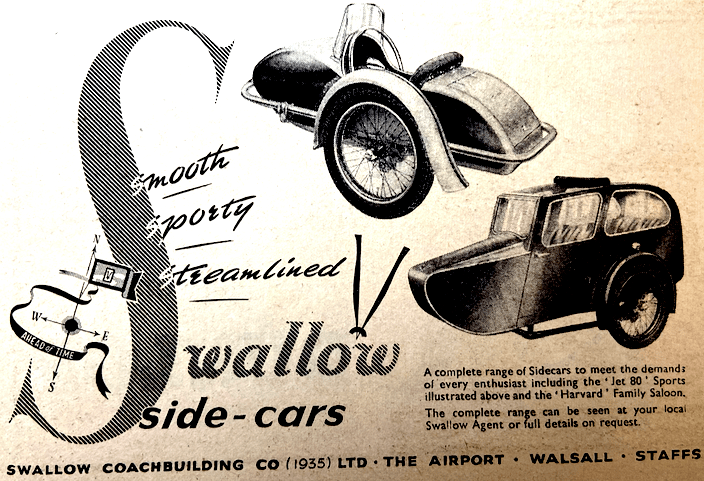

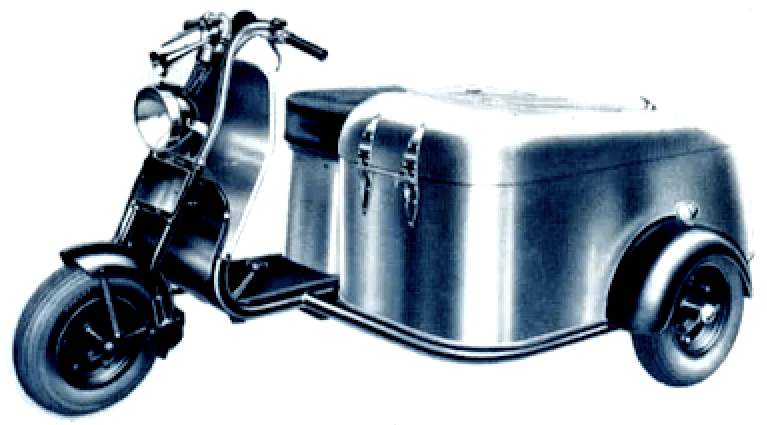

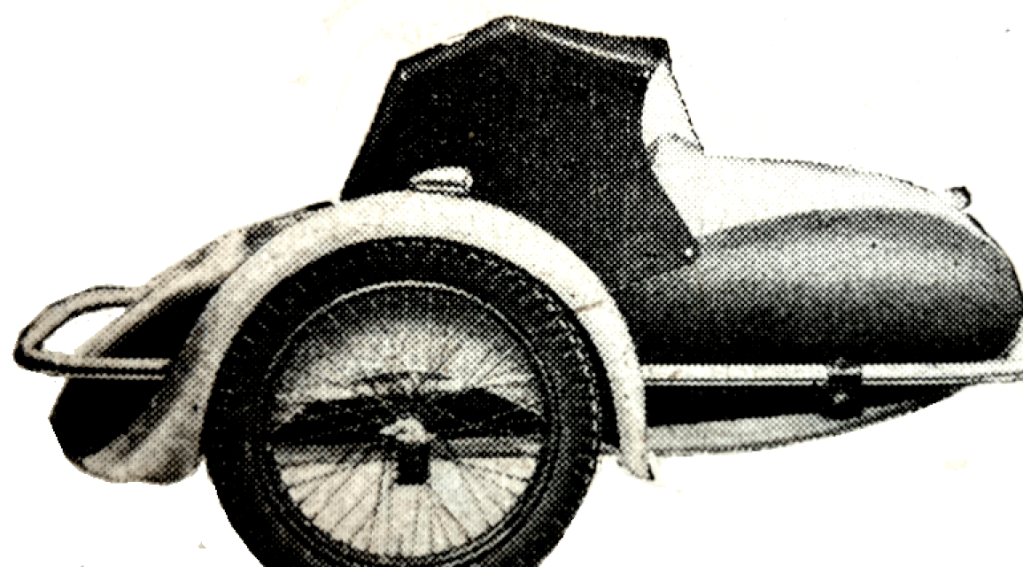

“THERE are signs of a definite demand for the ‘integral ” type of sidecar. This means more than a sidecar which is mechanically non-detachable by reason of brazed connections. As soon as a designer decides that on a given model the sidecar need never be detached, a small bevy of novelties instantly leap to mind. The first is that the usual chair snout has suddenly become ridiculous. Why should ‘she’ have her feet snugly ensconced, while ‘his’ legs are left at the mercy of all the winds that blow and all the mud that is flung? So something approaching a dashboard 5ft wide begins to replace the abandoned snout. Next, the designer concludes that a third brake is desirable to bring the stoppers up to car standards. Then he begins to worry about accessibility—it may be necessary to render the sidecar swiftly detachable from its chassis so that the -owner may reach that side of the engine. Finally, he finds himself saddled with something looking as odd as the Scott Crab. I have chatted with sundry folk engaged on the design of ‘integral’ sidecars; they remain loyal to their ideal, but they spend a bob a week on headache powders. (Don’t mention suspension’ to any of them!)”—Ixion

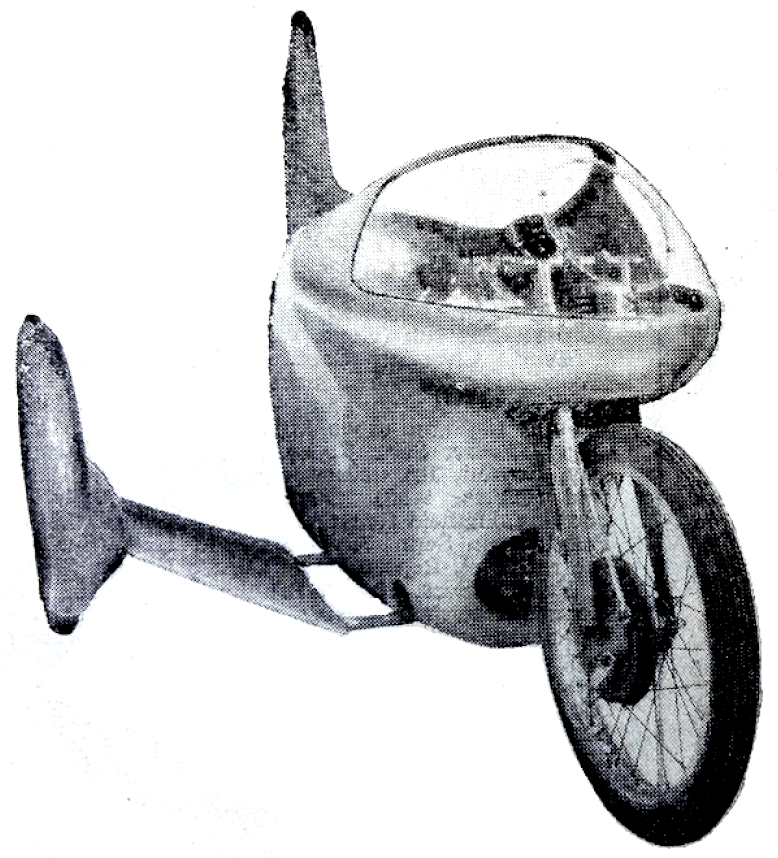

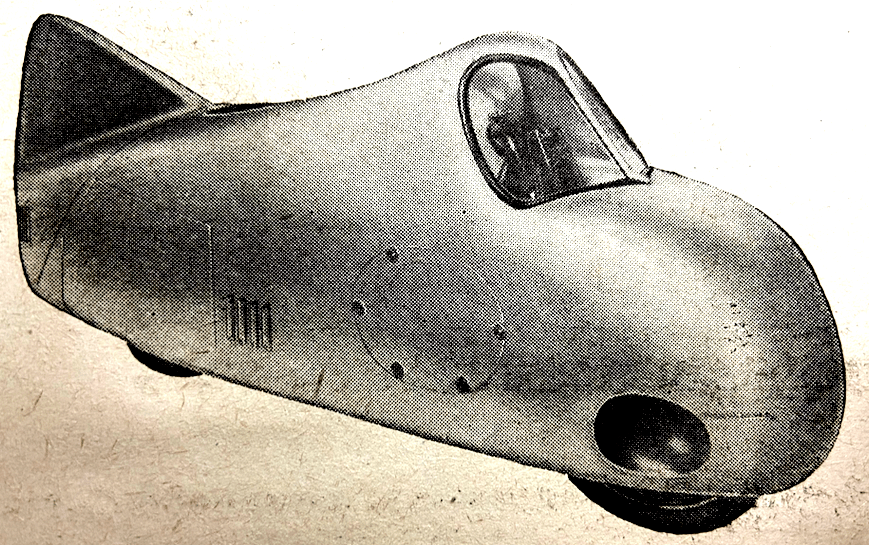

“ON DECEMBER 2 the Guzzi factory achieved a feat so far out of the ordinary that it deserves prominence here. It will interest those lads who handle 250cc sidecar outfits. They supercharged and streamlined one of their 250cc racers, fixed a sidecar to it. and sent it out on the Milan autostrada for speed trials with Cavanna at the helm. Unluckily, the electric timing gear gave incessant trouble, so I doubt whether they are claiming records at the moment. But the best speed registered while the clocks clicked was 209kph over the flying kilometre. This means approximately 130mph. Footnote: Some of our best engineers used to consider it a waste of time to blow a single-cylinder.”—Ixion

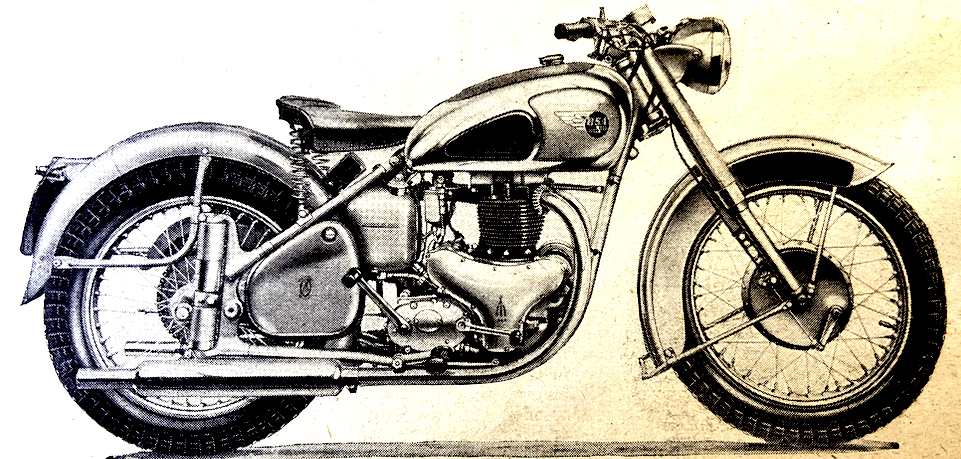

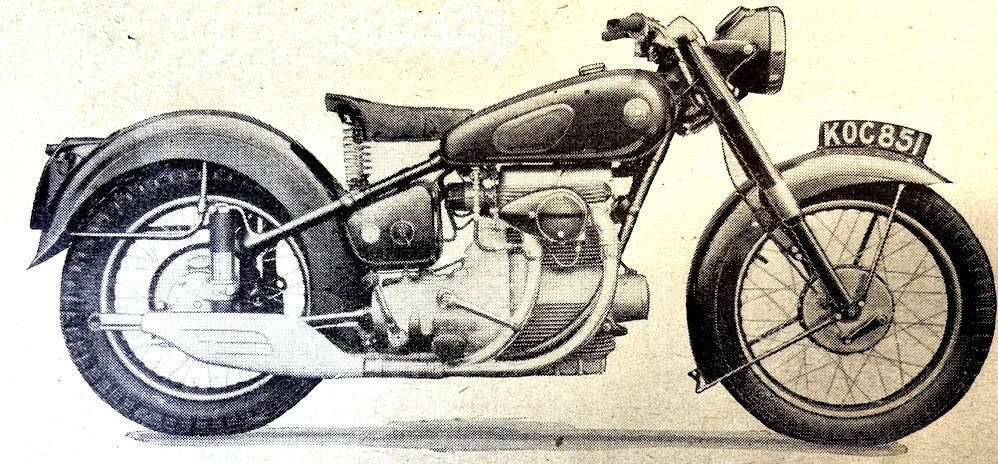

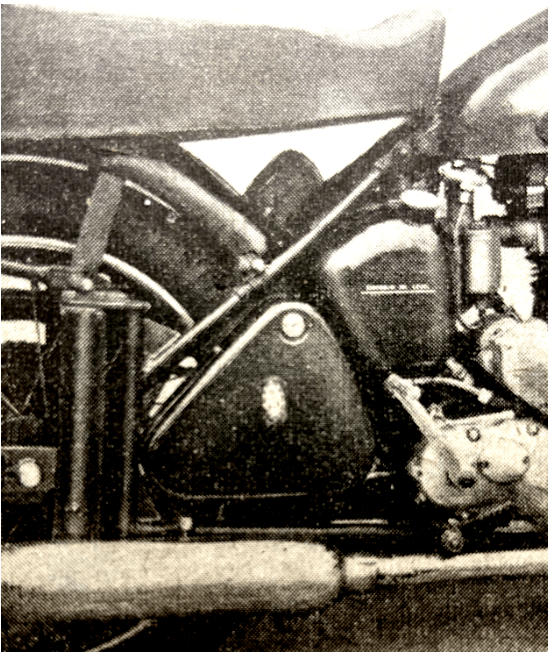

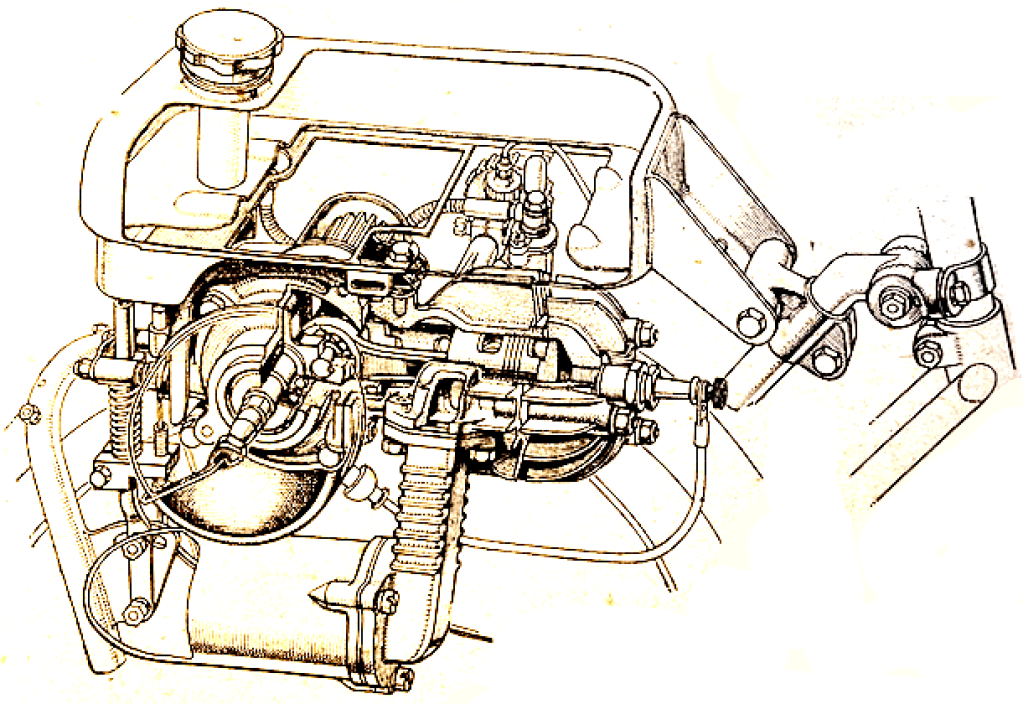

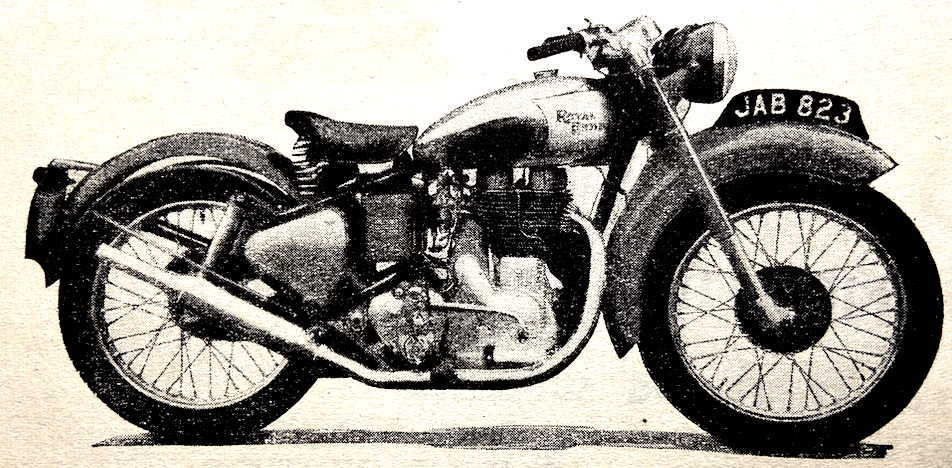

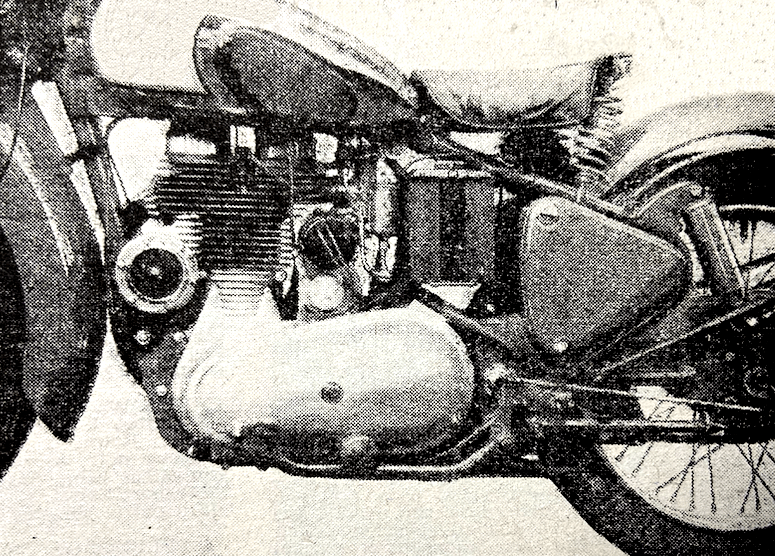

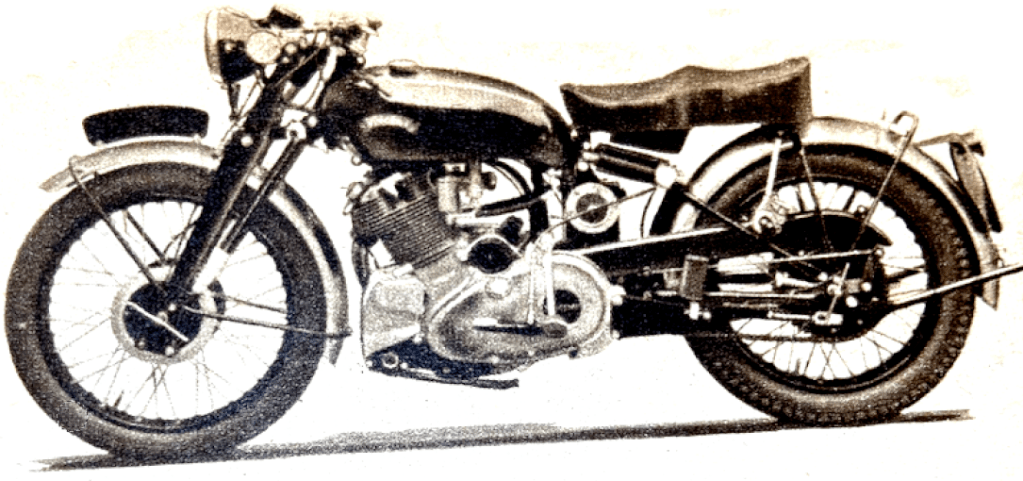

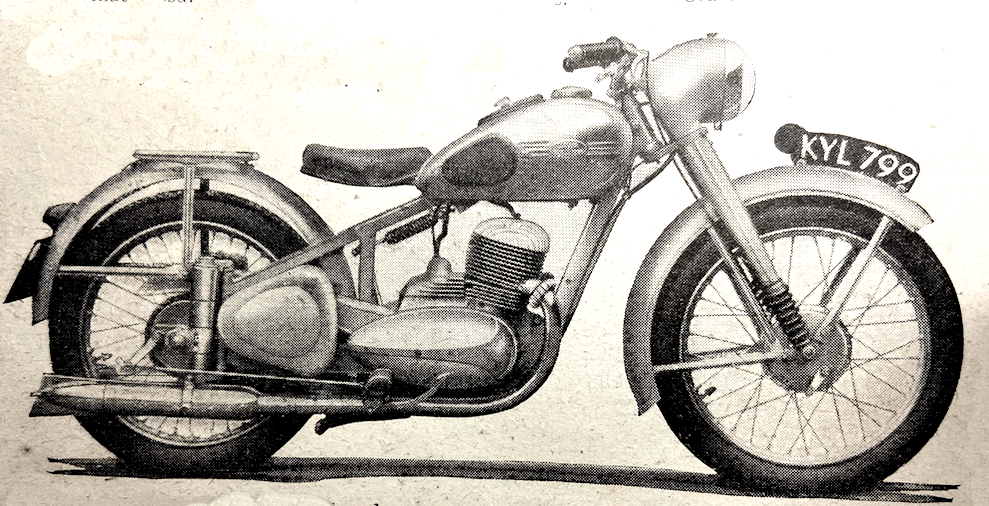

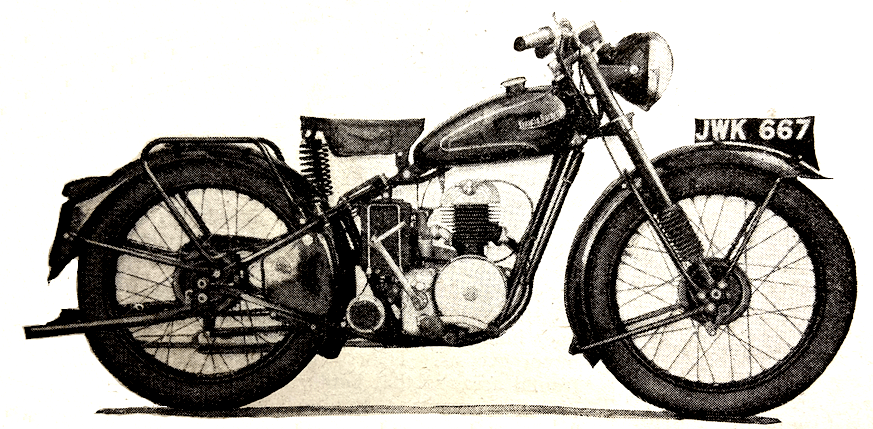

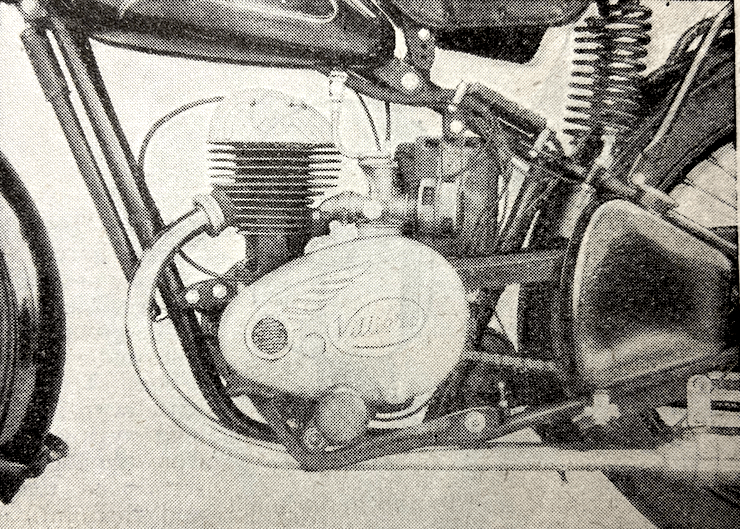

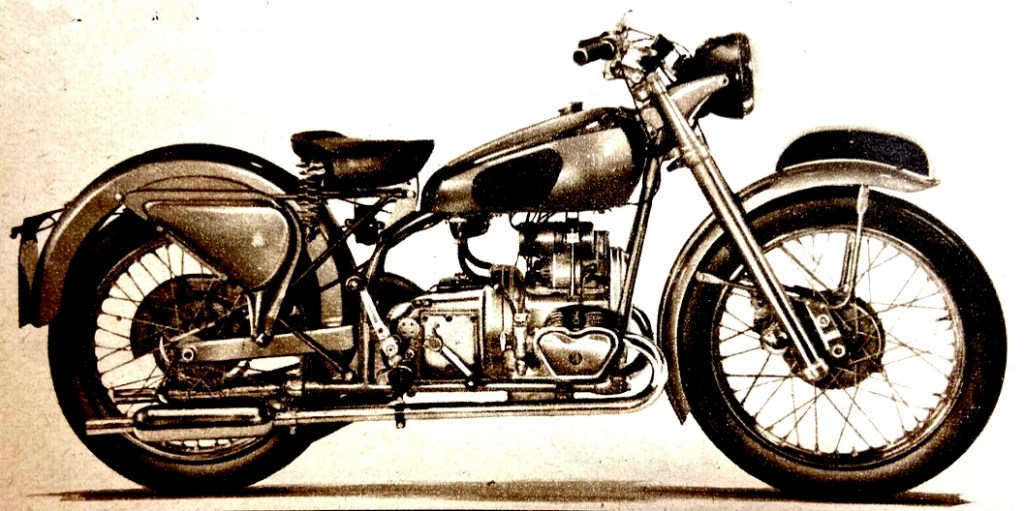

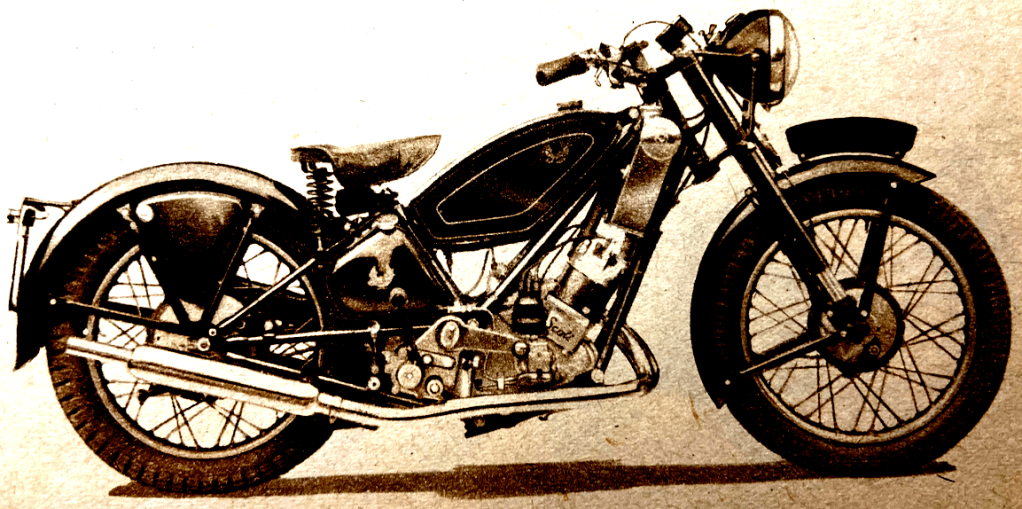

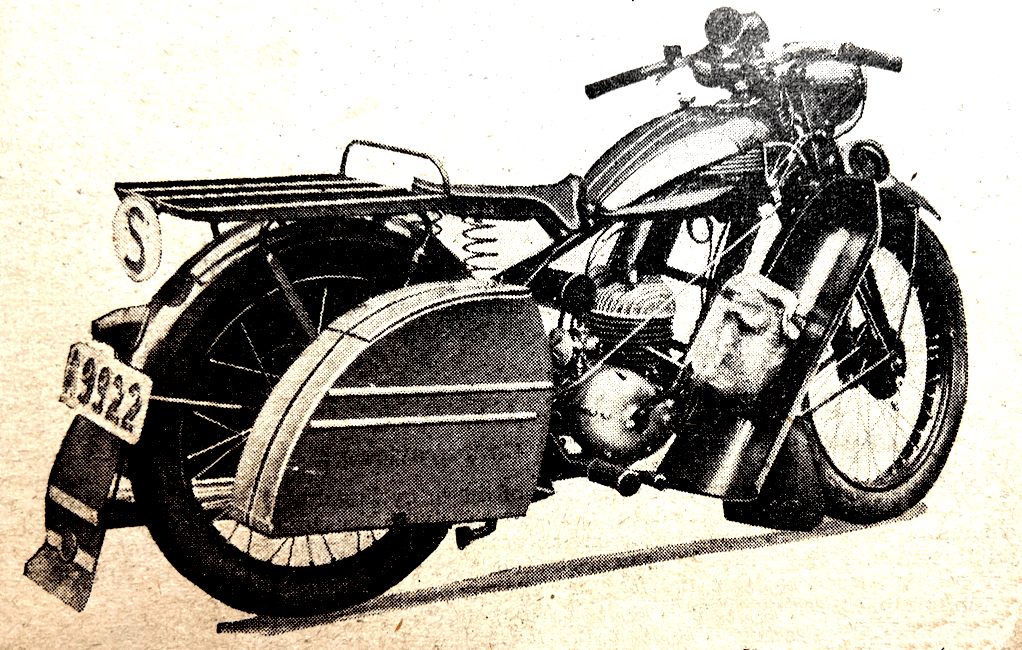

SUNBEAM S8

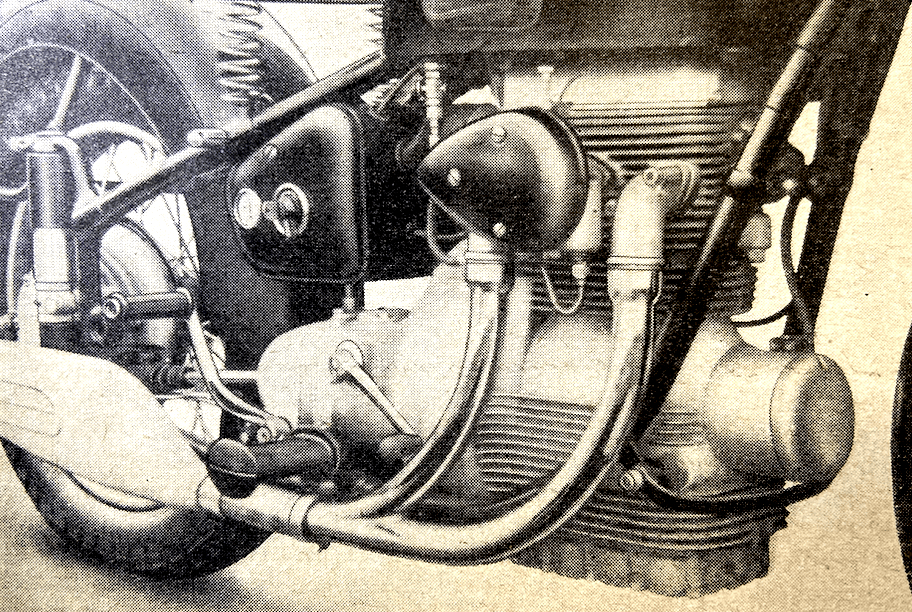

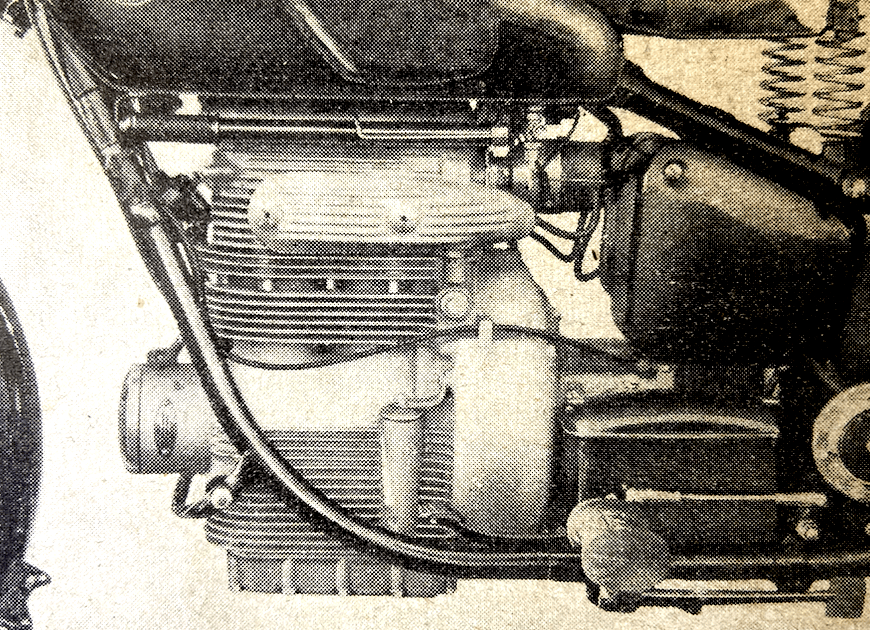

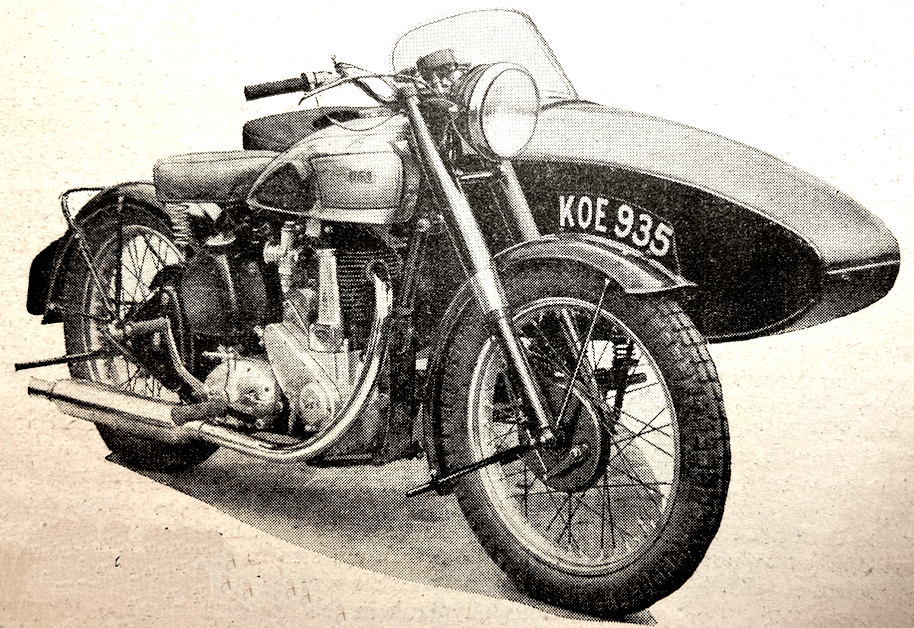

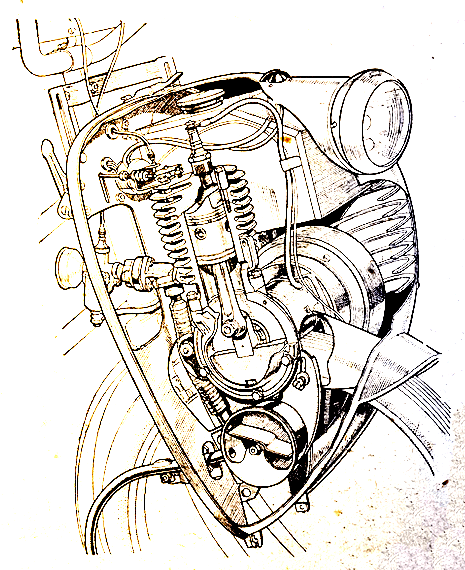

WHEN THE FIRST thrilling post war Sunbeam was announced it was acclaimed as a mount embodying most of the features demanded by the cognocenti. With its in-line parallel twin-cylinder engine and gear box in unit, shaft drive, coil ignition, unique appearance and many ingenious features it, represented a complete breakaway from current motor cycle design. The Model S8, of course, is the lightened version of the original design, It is a machine which has so many praiseworthy attributes that it is hardly possible to single out any one of them and say of it that therein lies the model’s attraction. But if there is one feature that leaves an outstanding impression after experience with the S8 it is the smoothness of the engine and transmission, especially when the engine is revving in the higher ranges. The end of every run during the test, irrespective of length, and under all but the very worst of weather conditions, was reached with regret. There was no pace above 30mph which could be said with certainty to be the machine’s happiest cruising speed. The engine gave the impression that it was working as well within its limits at 75-80mph as it was at 45-50mph. It thrived on hard work and was a glutton for high revs. A pronounced tendency to pinking on pool fuel was noted when the machine was being accelerated hard in top or in third gears. Therefore, on the occasions when it was wanted to reach B from A just as quickly as the machine could be urged, the engine had to be revved very hard in the indirect ratios. Peak rpm in bottom and second gears, and almost as high rpm as were available in third were frequently used—with the most pleasing results. Steering and road-holding were so good that the rider was encouraged to swing the bends with joie de vivre. No oil leaks became apparent in the 600-odd miles of the test. The exhaust pipes did not even slightly discolour. Nothing vibrated loose. The toolkit was only removed from its box on one occasion—and that was out

of sheer curiosity. Mechanical noise was no more apparent at the end of a hard ride than it was at the beginning. Except on the odd occasions when grit found its way into the jet block, engine idling was slow and certain. When the engine was running at idling speed or only slightly faster it rocked perceptibly on its rubber mounting. This rocking was transmitted to the handlebars in the form of slight vibration and was apparent up to speeds of just over 30mph in top gear. Above, say, 33mph, there was complete smoothness Even when the engine was peaking in the indirect ratios the machine was smooth to a degree never hitherto experienced with motor cycles. The harder the engine was revved the smoother and more dynamo-like the machine apparently became. Only the inordinate exhaust noise tended to restrict the use of really high rpm; the exhaust noise, it should perhaps be added, was never obtrusive to the rider. Starting the engine from cold during the recent icy spell. or when it was already hot, was so easy that a child could do it. When the engine was cold it was necessary to close the carburettor air-slide by depressing the easily accessible spring-loaded plunger on top of the carburettor and lightly flood the carburettor; then, with the ignition switched off, to depress the kick-starter twice; switch on the ignition, and the engine would tick-tock quietly into life at the first kick. The air-slide could be opened almost immediately after a cold start. Because of the combination of well-chosen kick-start gearing and relatively low compression ratio, so little physical effort is required to operate the kick-starter that it can be depressed easily by hand pressure. If there was ever such a thing as tickle-starting, the Sunbeam most certainly has it. An outstandingly high standard of mechanical quietness was yet another of the Sunbeam’s qualities. Only the pistons were audible after a cold start. As near as could he ascertained, the valve-gear was noiseless. Low-speed torque was very good, and the engine would pull away quite happily in top gear from 19-20mph. From idling to full throttle the carburation was clean and the pick-up without any trace of hesitation. Acceleration was all that could be expected from a machine which falls into a ‘luxury fast-touring’ rather than a ‘sports’ classification. When the mood was there, however, and the full engine performance was used in the indirect ratios, acceleration was markedly brisk. Pressure required to operate the gear change was so light that the pedal could barely be felt under a bewadered foot. The range of movement of the pedal was delightfully short and allowed upward or downward gear changes to be made merely by pivoting the right foot on the footrest. Clean, delightful gear changing could be effortlessly achieved. Between bottom

and second and second and third gears the pedal required a slow, deliberate movement. Between third and top gears the change was all that could be wished for—light and instantaneous. The clutch, too, was light in operation and smooth and positive in its take-up of the drive. It freed perfectly and continued to do so even after six standing-start ‘quarters’. It required no adjustment during the course of the test. For riders of all but unusually tall or short statures, a better riding position than that provided by the S8 could not be imagined. Saddle height is 30in. The footrests can be ideally situated (they are adjustable through 360°) so that they provide a comfortable knee angle. Even at their lowest position of adjustment they are sufficiently high not to foul the road when the model is banked well over on sharp corners or fast bends, or when it is being turned round in the width of narrow lanes. The wrist angle provided by the handlebars was extremely comfortable. Handling was at all times beyond criticism. There was no trace of whip from the duplex frame or of lack of lateral rigidity from the plunger-type rear suspension. With plunger-type suspension spring characteristics normally have to be rather ‘hard’. Total movement was approximately 1¼in. The degree of cushioning is therefore not large. The hydraulically damped telescopic front fork was very light round static load and behaved perfectly under all conditions. Both brakes provided first-class stopping power. They were light to operate and smooth and progressive in action. They did not fade under conditions of abuse, never required adjustment during the test, and were not adversely affected when the machine was driven hard through heavy rain and snow. The standard of mudguarding was very good. A long, road-width beam was provided by the 8in head lamp. Full lamp load was balanced by the 60-watt pancake generator at 30mph. in top gear. Numerous detail features of the machine make it easy to clean and maintain. The ignition coil, voltage control regulator, ammeter and combined ignition and lighting switch are housed in a metal container below the saddle. Opposite to it the battery is housed in a lead-lined box of similar proportion and design. Both front and rear wheels are quickly detachable, the rear especially so. Ignition and oil warning lights are located in the head lamp, one on each side of the speedometer. The speedometer in this position was easily read when the rider was in a normally seated position. The instrument registered approximately 7% fast and ceased to function at 589 miles. Finish of the test machine was black and chromium and the quality fully in keeping with the high engineering standards used on the machine.”

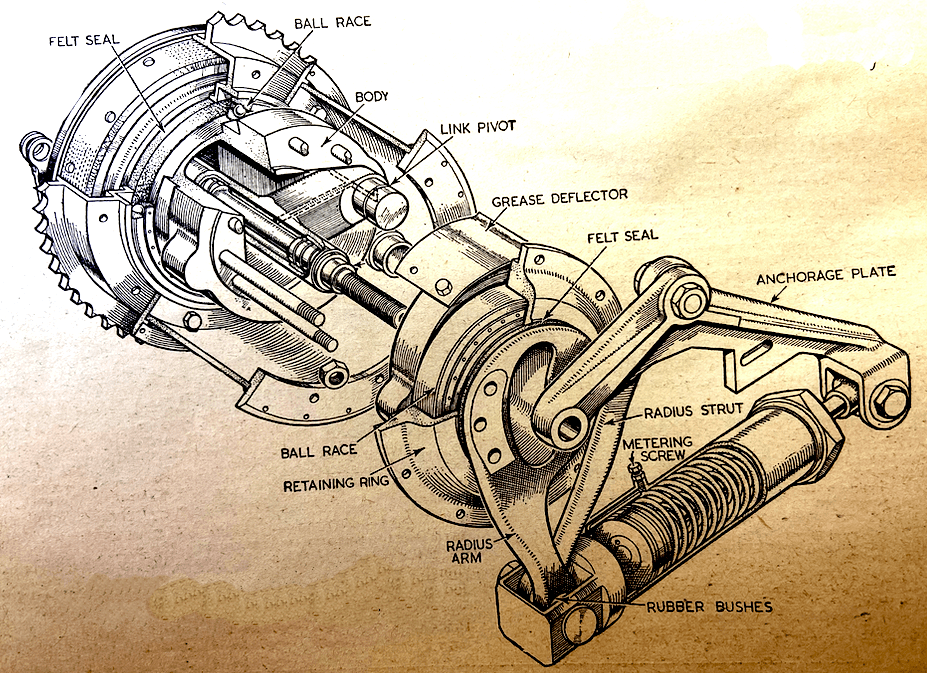

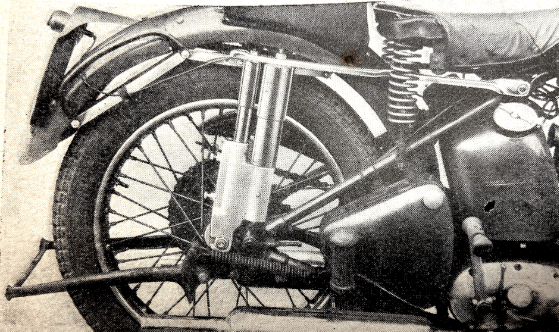

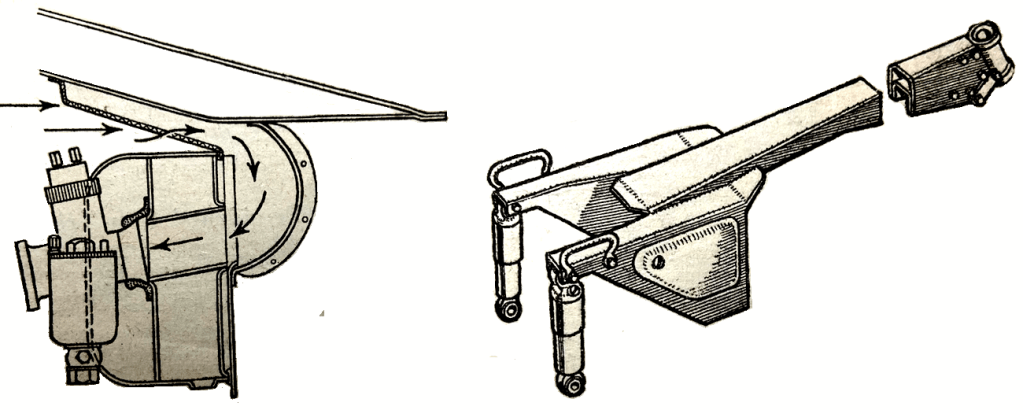

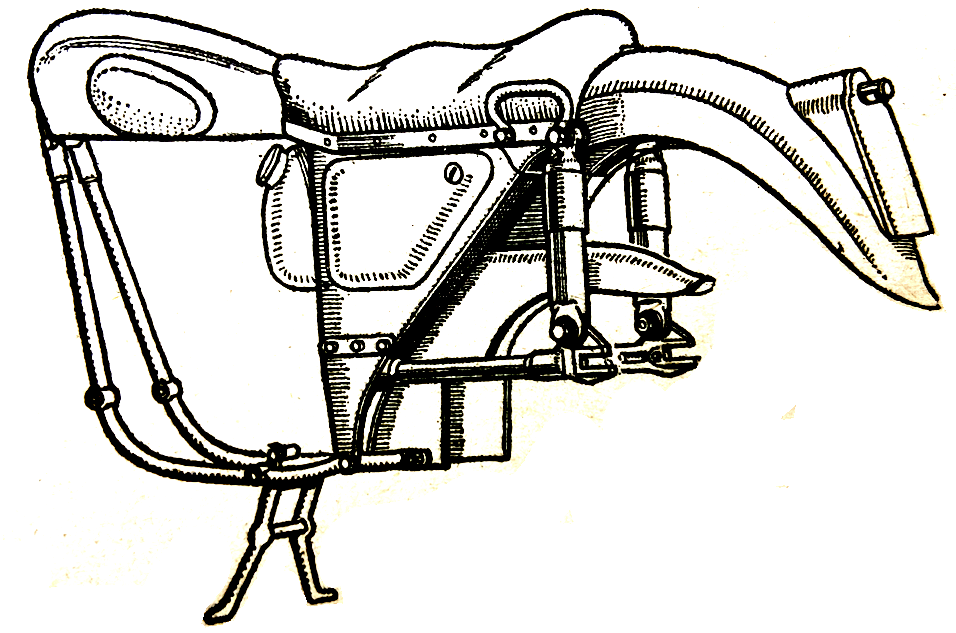

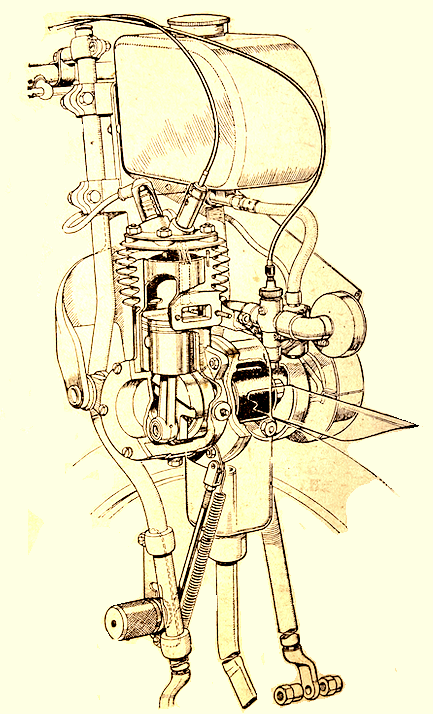

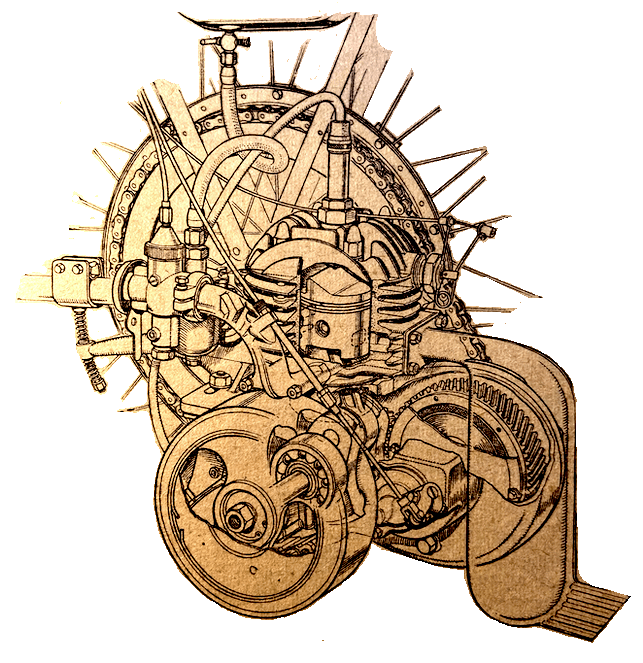

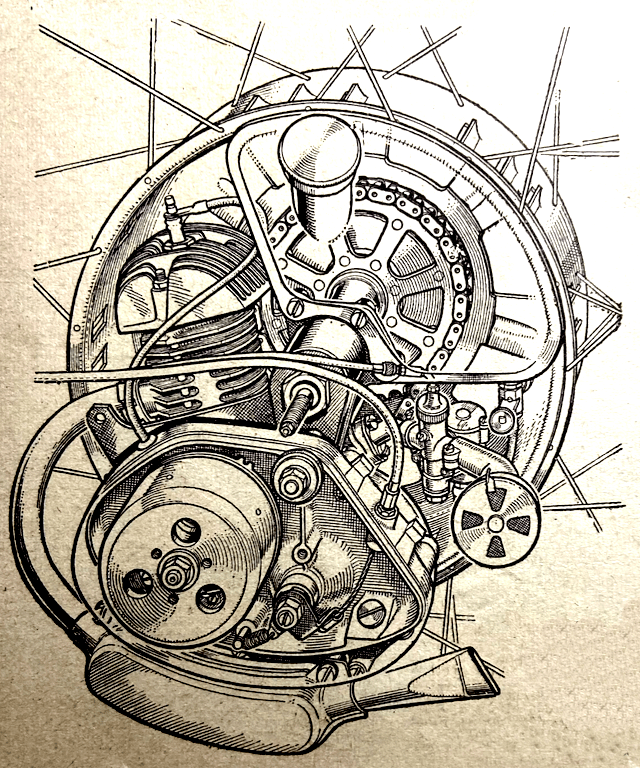

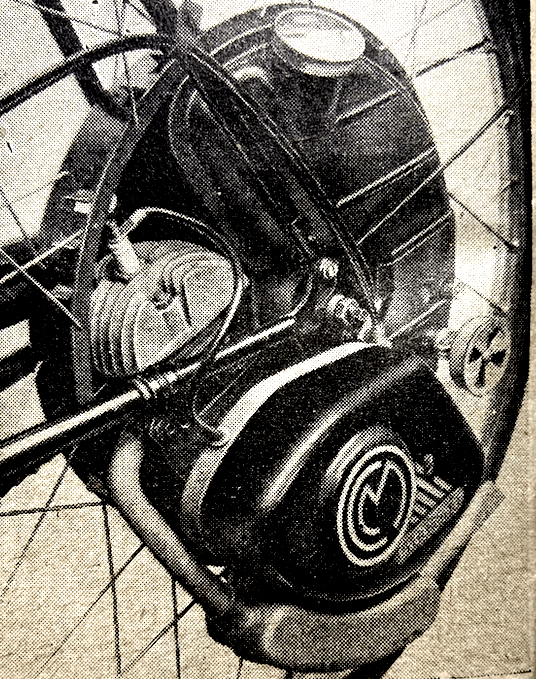

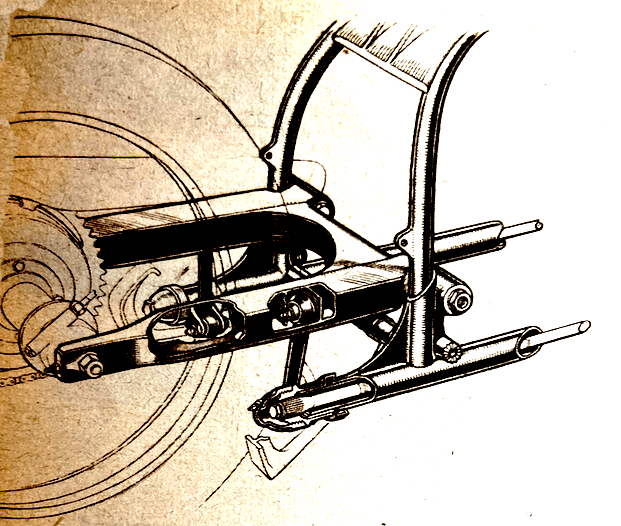

“READERS WILL RECALL an ingenious spring hub designed by Mr AT Clark…the suspension is now available as a proprietary unit. A light steel hub approximately 8in in diameter is spoked into the wheel in the orthodox manner. Bolted to the left-hand side is the brake drum which carries the sprocket; on the right side is a light-alloy flange. Within the hub shell is a two-piece light-alloy body mounted on ball races of 5¼in external diameter; thus the body can move relative to the hub shell…Brake size is 7in diameter with ¾in wide linings. The shoe-plate is a light-alloy casting and a long torque arm is fitted; provision is made for the slight movement of the shoe-plate relative to the hub when the suspension is operating. Two inches of rear-wheel movement is permitted, and the variation in chain tension is negligible. The weight of the suspension system complete with brake and wheel is 39lb, or approximately 10lb above the average wheel and brake fitted to a standard machine. The suspension is sold as a conversion unit which includes the hub complete with all mechanism, the brake, sprocket and wheel; in other words, the standard wheel and brake is removed and the sprung wheel is fitted. Among the attractions is the fact that a purchaser can retain the standard wheel and refit it on selling his machine, with the idea of employing the Clamil wheel with his new model. There are two further noteworthy points. The pillion passenger enjoys the full advantages of the suspension and the mechanism does not hamper the fitting of panniers or other luggage-carrying equipment. Stronger springs are available for heavy-duty sidecar work. Experience on the road showed that this type of spring hub has much to commend it. All heavy road shocks are eliminated and the springing characteristics are particularly well suited to high speeds over bumpy surfaces. There is no pitching—not even on the type of concrete highway with regularly spaced expansions strips. During fast cornering the rear wheel remains in contact with corrugated-type surfaces and there is no tendency for the wheel to chop out. The springing is rigid laterally. Especially noteworthy is the extent to which rear-wheel braking is improved. The brake supplied as part of the conversion unit is progressive and powerful in operation. That apart, however, the greatest improvement lies in the manner in which the rear wheel, under the influence of the springing system, adheres to the road surface during heavy braking. Standard springs were fitted. These are of a strength calculated to be suitable either for a solo rider or for a rider plus a heavy pillion passenger. My impression was that the springing was on the hard side to give maximum comfort at low speeds over minor bumps and that at slightly higher, though not fast, speeds, wheel movement was inclined to be too lively…An experimental type of piston was fitted which provided no depression damping under impact loading as is the-case with the standard piston. Price of the Clamil spring hub complete is £29 10s. Manufacturers are Millars Motors, 363, London Rd, Mitcham, Surrey, under licence from Clamil Suspension.”

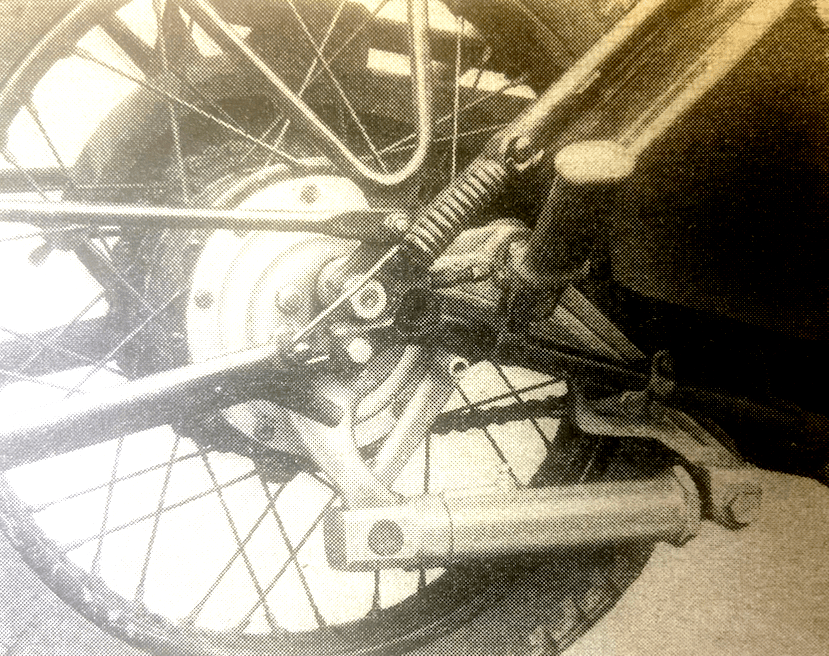

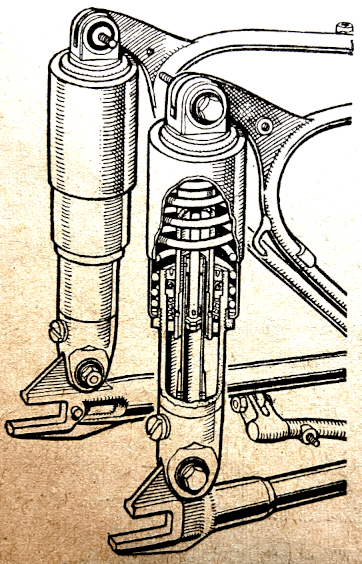

THE SIDDAWAY SPRING HEEL conversion for AJS and Matchless machines [has been available since] 1948. Mr Geoffrey Siddaway has now designed a similar conversion set to fit Triumph 3T, 5T and T100 models. Of the plunger type, the springing has a total movement of 2¾in and is provided with adjustable two-way hydraulic damping. Both compression and rebound damping actions are separately adjustable by means of four accessible metering screws provided with lock-nuts. In tests carried out with a.1946 Speed Twin equipped with this springing, it was found that the damping adjustment can readily be set to suit different static loads and various riding conditions. With two ³⁄₁₆in spanners alteration of the setting took approximately 20 seconds. Half a turn on the metering screws was found to be sufficient for the load difference between solo riding and riding with a pillion passenger. For normal riding between home and office, a screw setting of one turn out from the fully closed position gave soft springing, both responsive to the lesser road shocks and absorbent of the large bumps. In other words, a thoroughly comfortable ride was given over varying surfaces, including South London’s notorious three-ply tram-tracks with their frequent, upstanding inspection covers.”

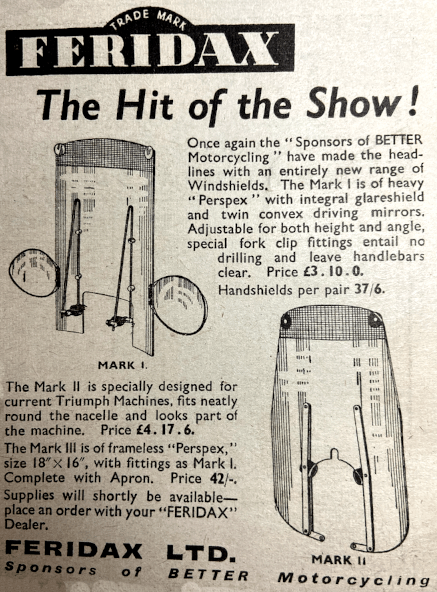

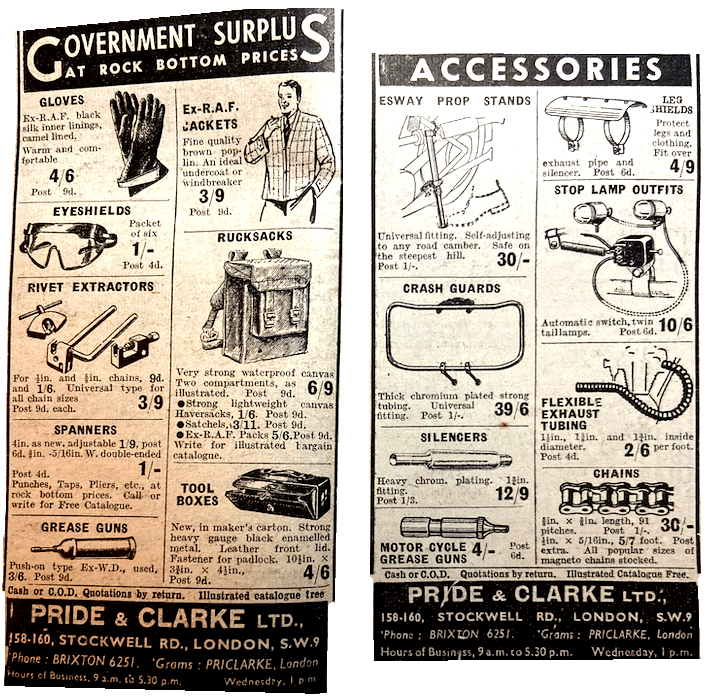

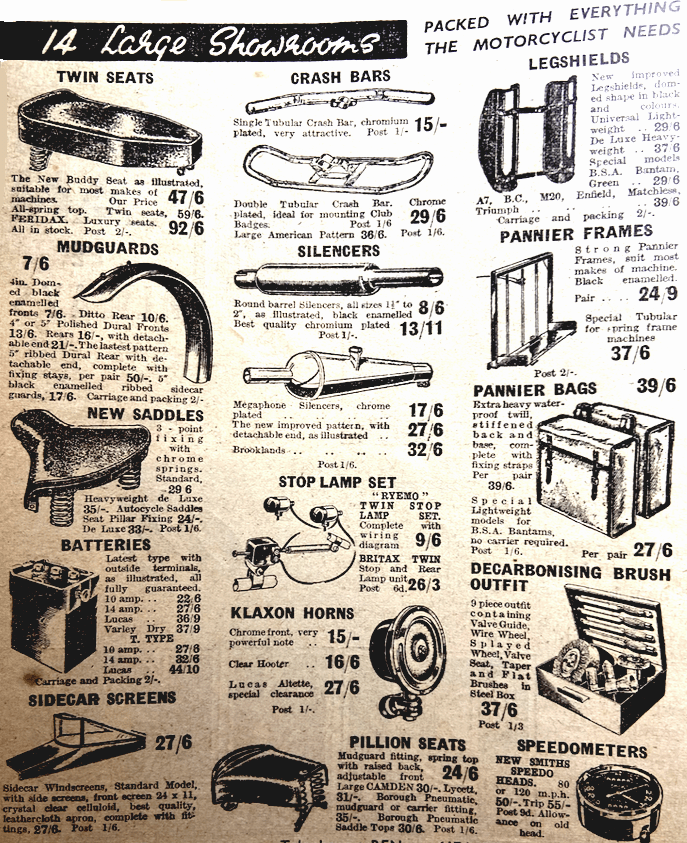

“PLUNGER-TYPE REAR-SPRINGING is shortly to be marketed by Feridax, the well-known accessory manufacturers. The total movement is 2½in. Springs are used on compression, and the rebound is hydraulically controlled. The springing will be suitable for converting any rigid-frame machine. Though the price is not yet fixed, it is said that it will come out at ‘well under £20’. New-type legshields announced by Feridax are for fitting to the Feridax crash-bar. The shields are of steel, chromium-plated, and are of smart appearance They measure 23½in long, and taper from 7½in wide at the bottom to 7in at the top. The price is 35s (the Feridax crash-bar costs 37s 6d).”

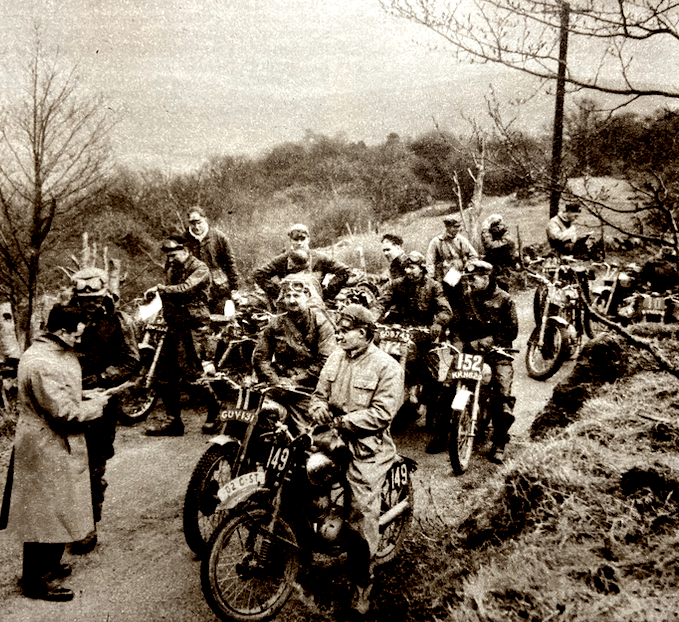

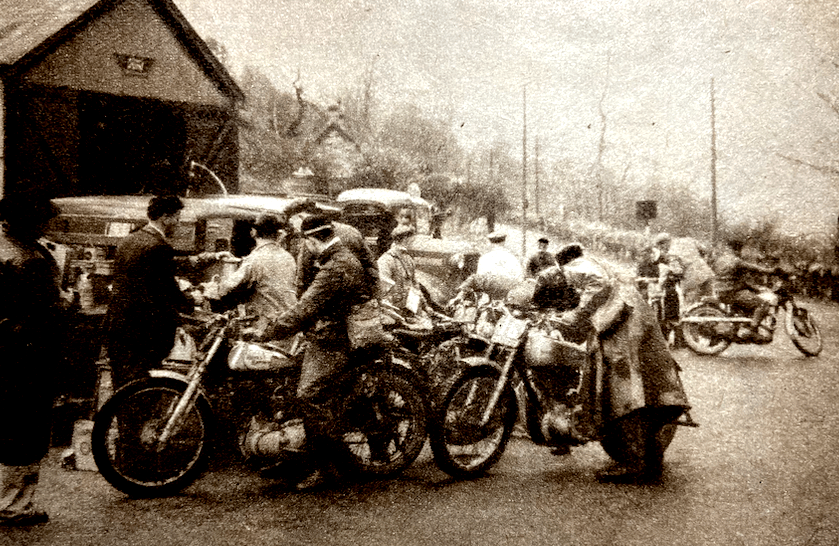

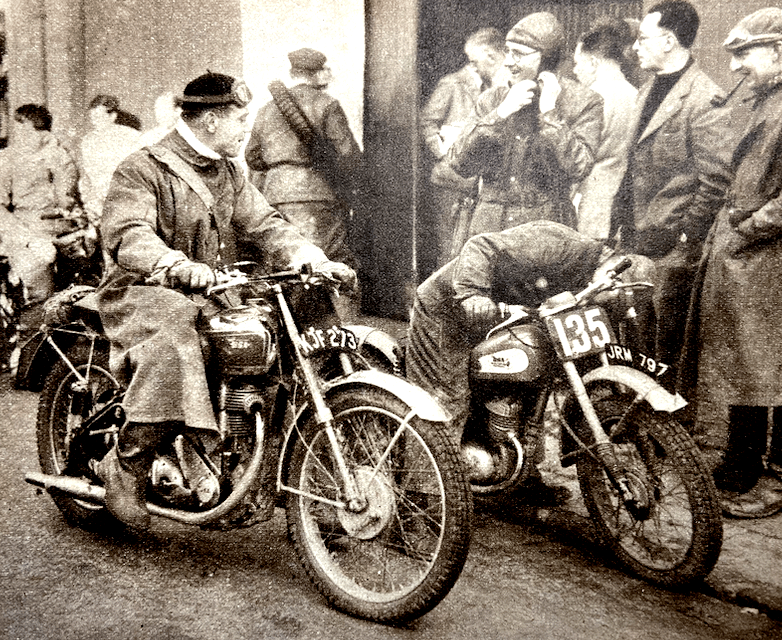

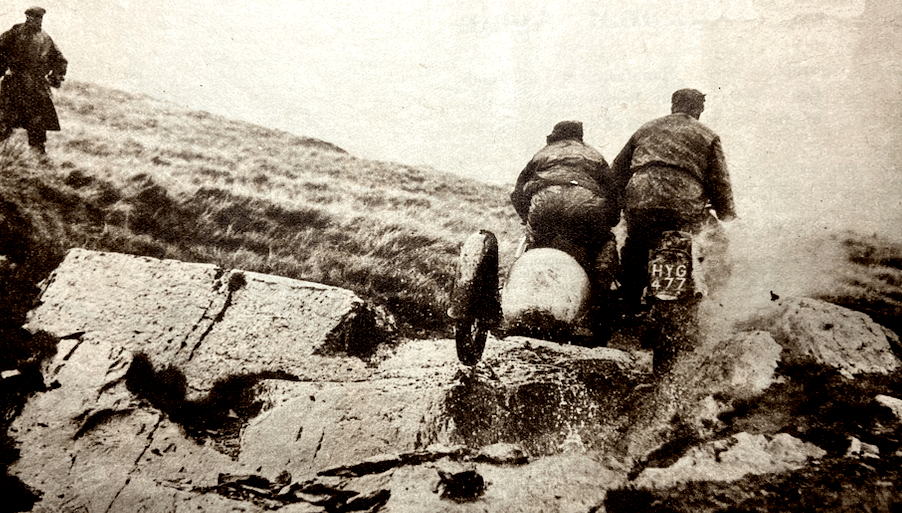

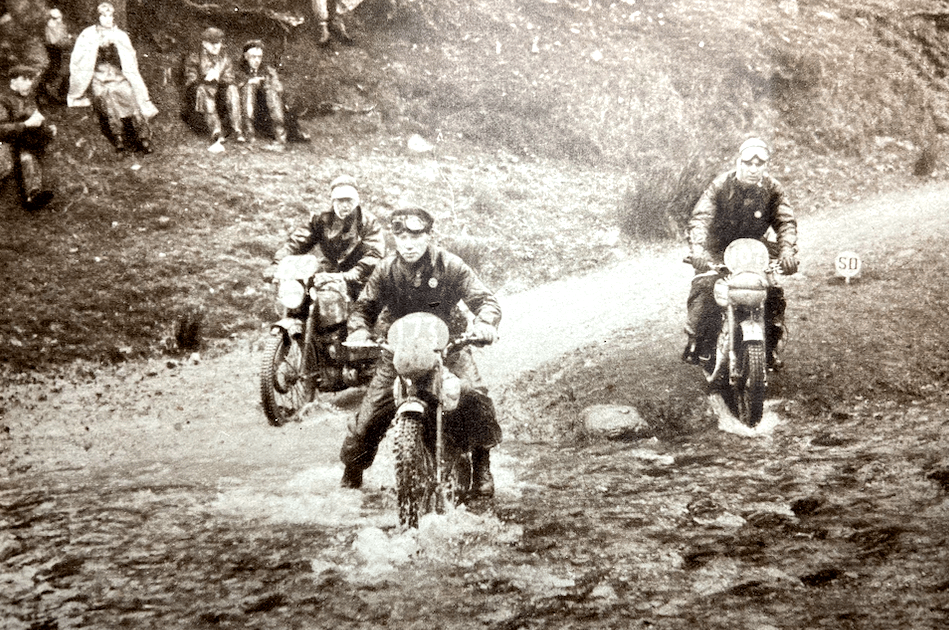

“WHEN PETROL AND, THEREFORE, mileage cease to be rationed, no doubt the MCC’s famous winter run, the Exeter Trial, will revert to type: then will be the long trek through the night—a tiring, rigorous and, sometimes, adventurous prelude to quite a stiff trial course. If there is no snow—shades of the 1927 event which had to be postponed because the route was impassable—but the more usual cold rain or mist or sleet, the trial will still be different. The reason is farm mechanisation. Those who were so fortunate as to have the petrol to run down to last Saturday’s Exeter Trial over one of the usual Exeter Trial routes will need no explanation of the words ‘farm mechanisation’. They saw the mud, the slime and the great lumps of earth which the wheels of the now hordes of tractors had deposited on the highways. Maybe it is impossible for farmers to avoid this (we will not enter into that subject again!) but the fact remains that on the night run there will be a fresh hazard. Although the ‘Exeter’ this time had to be an abbreviated version, it still had character and was great fun. Some competitors had ridden down overnight. All looked forward to tackling famous old hills in their wintry guise, and, as usual, these hills—in winter—were a match for the majority. Instead of the 359 entries for the last full-blooded ‘Exeter’, that of 1939, the total was 96—17 more than in the first event, London-Exeter-London, in 1910. The start was from the city of Exeter, and the course of some 60 miles, which ended at the Peamore Garage and Restaurant, a mile or two outside Exeter, included Windout, Fingle Bridge (the hill of many hairpins), Stonelands (stop-and-restart test), Simms, and a trio of hills in the Ideford-Teignmouth area—The Retreat, Kennel and Coombe. As a trials course, this route sounds easy. It was not very difficult, but the MCC trials have always been events in which a man (and, nowadays, women) can take an ordinary motor cycle or car and, assuming skilful riding or driving, have a reasonable chance of

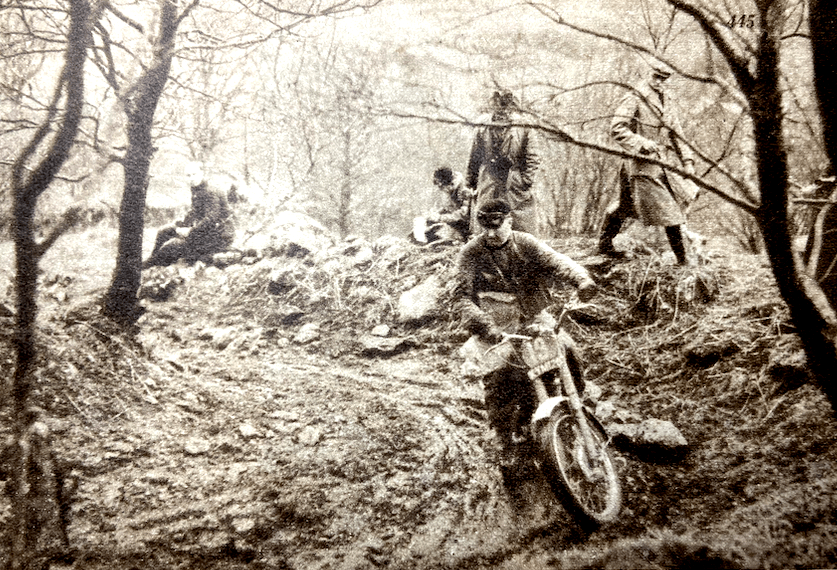

success. They are grand events in which to start competition riding, and far more difficult than the noses-in-the-air are apt to suggest. The awards’ list on this occasion answers this last point…the motor cyclists in the passenger class and a high proportion of the solo motor cyclists failed to bring home the bacon in the form of a first-class award. Those who travelled to Exeter on the Friday from any distance east had a surprise. Early in the day there may have been frost and ice, but down at Exeter it was almost mild and muggy. It was still quite mild when the trial started at 9am on the Saturday. A very few miles, however, and competitors were climbing up the road towards Moretonhampstead and Dartmoor. Hardly had they begun to climb when they were in cloud. The valleys were clear, but, once out of a combe, there was damp mist again. Then into lanes and down a grass-grown track to the watersplash that precedes Windout, a zig-zagging climb of about 1 in 5 which continues for perhaps a third of a mile. Windout is no coined name—coined because of the desirability of low tyre pressures; there is a farm of that name nearby. The first part of the roughish hill had water flowing down gullies between leaves, rocks and leaf mould. Higher up, there were dry leaves hiding stones, water-worn ruts and, occasionally, some patches of loose shale-cum-gravel. The splash at the foot was only inches deep and, as usual, the MCC concentrated on observing the hill, hundreds of yards of it. No 1 rider a was a trials rider of some 30 years’ experience, G Patrick, on a 125cc Royal Enfield. Using specially low gearing (no doubt with Simms Hill in mind) he hobbled up the hill, his back wheel lolloping over the stones and gullies. Then came a lucky lad, EJ Bores (348cc BSA)— lucky in that he slewed round, nearly cannoned, first, the left bank and, then, the right-hand one and got away with it. ‘Jimmy Green’ (an ACU-registered nom-de-guerre) saw the muddy going just round the first bend, made a lightning dart for the clutch lever of his 497cc Ariel and then, all being well, more leisurely wrapped his fingers round the handlebar.

AW Jeffery (347cc AJS) toured up the hill in a most genteel fashion. Then came Mrs Anning (347cc James), secretary of the West of England Motor Club. Just round the bend, she apparently had an attack of stage-fright—it was the first observed hill—for on seeing that she was heading towards some mud, she began to lift her right foot from the footrest to give a dab; but back her foot went. Then a fast ascent, complete with power slide (not so good) by DS Ham (490cc trials Norton). The next man, FW House—entered on a Triumph—was smiling to himself, though the rigidity of his rear view after he had rounded the first bend suggested that his mien became more serious. This however, may not be fair, because on Fingle, too, he had the same smile. FC Bray (490cc Triumph) was fast, somewhat furious and, perhaps, a trifle lucky. So to Fingle Bridge which, as recorded a year ago, is a hill which looks very different now that the woods have been cut down for timber. Further, the timber hacking has altered the hill’s surface to some extent. The latter is now composed largely of loose earth and stones. For a solo, especially a lightweight, the hill is far from easy. For instance, Patrick came unstuck here with his 125, yet later conquered the towering grade that is Simms in spite of its having a slimy, slithery surface. On the latter and worse part of Fingle, the portion where the hairpin bends are both steep and specially loose, DW Jones (348cc BSA), let his speed get to little more than that required for steering way. His engine pinked, there was a nasty gully ahead and he wobbled towards the bank; then it was a case of feet and next, a full stop. GH Burnell, on a BSA of similar size, made amends with a thoroughly workmanlike climb. The next man, W Bray, on a 346cc spring-frame Royal Enfield, seemed to have a sudden attack of nerves just before the gully, but it may be that he, too, was travelling barely fast enough to have steering way. Anyhow, he also stopped, and so did AJ Nichol (Tiger 100 Triumph), but in the latter case the trouble was that Nichol went too wide at a bend and bumped his front wheel over a tree root which protruded from the bank. FT Hosking (498cc Scott) made a good showing at the bend where The Motor Cycle representative was situated, and so did AC Hosking on a Triumph Trophy model, but probably the three best to be seen here were WA White (498cc Matchless), EJ Hain (347cc AJS) and HS Harding (499cc Royal Enfield). Next on the list of hills was Simms, which, although only some 200 yards in length, has an average gradient of 1 in 3½ and a maximum gradient of 1 in 2¾—and a sharp, right-hand bend at the foot. It is thus a hill which cannot be

rushed, and last Saturday it was very slippery, particularly the last third—from the rocky hump-cum-cross-gully onward. All the same, there were some fine climbs by solo motor cyclists. JHS Smith (197cc James) made a particularly good one. He shot up the hill at a speed surprisingly high for his engine capacity and, arriving at the specially slimy part, throttled back, mating the power to the available wheelgrip. WF Martin (249cc BSA) toured up neatly, making good use of the suitable characteristics of his engine. Then another clean climb by HS Harding (Royal Enfield), who skated a little near the summit, but never allowed the skating to attain the figure variety. Sidecars followed. First of the sidecarists was that old hand, SH Goddard (197cc Ambassador). For the restart at the foot he wisely arranged his machine at an angle across the road, sidecar above machine, so as to obtain maximum wheelgrip. He clambered up the first part, displaying remarkable power and speed, but, at the gully-cum-hump, wheelspin set in and the tow-rope had to be used. JW Smith (490cc Norton sc) got but a yard higher. The revs of his engine were so high at the hair-pin bend at the foot that the valves were floating madly. All the sidecars failed, and so did WE Wonnacott’s two-rear-wheel Morgan, though it did get appreciably higher up the hill than any of the other passenger motor cycles. With Simms defeated (or undefeated, as the case might be) there remained a not-too-difficult trio in the Retreat, Kennel and Coombe. However, there was trouble en route. Mrs Anning retired—conveniently within about half a mile of her own home!—owing, she thought, to condenser trouble. Farther on, JW Smith’s passenger was seen searching the countryside for wire with which to fix the Norton’s exhaust pipe. RESULTS First-class Awards—EJ Bores (348cc BSA), AW Jeffery (347cc AJS), ‘Jimmy Green’ (497cc Ariel), DS Ham* (490cc Norton), FC Bray (493cc Triumph), EJ Hain (347cc AJS), WF Martin (249cc BSA). Second-class Awards—G Patrick (125cc Royal Enfield), FW House (349c Triumph), DW Jones (348cc BSA), AC Hoskins (498cc Triumph), WA White (498cc Matchless), WJ Peake (349cc BSA), HS Harding (499cc Royal Enfield), JH Smith (197cc James), AE Cornell (348cc Martin), WE Wonnacott (990cc Morgan). Team Award—DS Ham (490cc Norton), FW House (349cc Triumph), FC Bray (490cc Triumph). *Winner of a Triple Award for gaining a ‘first-class’ in all three events—the 1949 Land’s End, Edinburgh and Exeter trials—the sole ‘Triple’ to be gained in the motor cycle classes.”

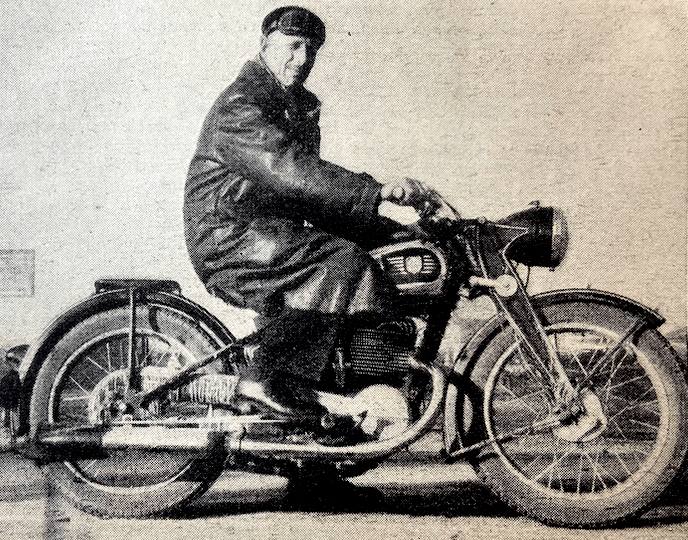

‘TORRENS’ DESCRIBES SOME pleasant days on a journalists’s life: ‘Friday morning, Dorset House; Friday, 6pm, Exeter; Saturday, Exeter Trial; Sunday, return to London, plus writing; Monday, office, press day; Tuesday, office, trip to the West, a call, a dinner; Wednesday, noon, back in office—thus might run the diary, if I kept one, but, in place of some 40 words 4,000 would be necessary to give much more than the bare bones of what could be a misleading story. Take the case of Harry Louis—his trip over the few days previous to my writing this. Extracts from his diary might read: Thursday morning, London Airport; Thursday afternoon, Brussels; Friday and Saturday, Brussels Show, plus writing, plus meeting Belgian officials; Sunday evening, office; Monday, office, press day. In the one case, 700 miles on roads and by-roads in five days, a trial, a dinner, a visit to a factory; in the other, 3½ days, a couple of flips by air, a foreign country visited, examination of a big Continental show. These are ingredients of the life of a motor cycle journalist—the whole life according to the thoughts of many. They are the jam: sticky jam sometimes, in view of the need for conjuring oneself

and, finally, the ‘copy’, to the right place at the right time. Except for the ‘jam’—the trips, the trials, the races, and trying this and that—life, of course, is mainly of the chairborne variety. There is the paper to be devised, made up and ‘put to bed’, week by week; the whole time letters are pouring in, and every office-hour spent away means an hour’s back-log. Last year the total number of letters answered by our technical information department ran well into five figures. Goodness knows what the grand total for the staff as a whole would be if all of us kept count. However, today we are dwelling—in my case, lovingly—on some of the jam: 700 miles in mid-winter on a brand-new motor cycle and no rain. There was the new Four to be tried. It had covered some 520 miles in the hands of the works’ folk, had no doubt had some preliminary running-in on the engine test bench and had been ridden 60 or 70 miles, mostly in traffic, by me. Thus the engine had had an opportunity of bedding down to a useful degree. There was no need to treat it with the care normally bestowed on a new-born babe. On the other hand, I still believe that there is a lot to be said in favour of a little restraint during the early point of an engine’s life…the first thing was to ready the mount for the miles in store. How many times have I read the words, ‘When you gloat over your new mount, do so with a spanner in your hand’? All I did in the time available was to check over the safety aspects, top up the oil-tank, see to the tyre pressures, and arrange a lead for my electrically heated gloves. Oh, yes! I also lowered the footrests so that I could poise on them. If on the machine striking a pot-hole or other bump, one automatically rises on the footrests, one rides the machine—there is no bang on one’s spine via the saddle and no tired feeling at the end of a longish run. At least, this is my belief. Seeing to the ‘safety aspects’ comprised checking the tightness of wheel-spindle nuts, all mudguard fixings, and sundry other nuts, bolts and screws which hold things together. Mudguard fixings are a fad of mine; there is a nick out of my nose caused by a front guard that fractured and locked the wheel. Tyre valves were checked for angle at the time each tyre pressure was adjusted. There was not time to reset the control levers by the trifles that I deemed desirable. The factory had remembered that I consider the place for the hornpush is the left handlebar…So up to the office, where the Art Editor was grisling, as he had expected me there the instant the office had opened and was holding up the annual ‘What I Rode’ article in the hope that I would caption the pictures. Freedom came after an earlyish lunch…'”

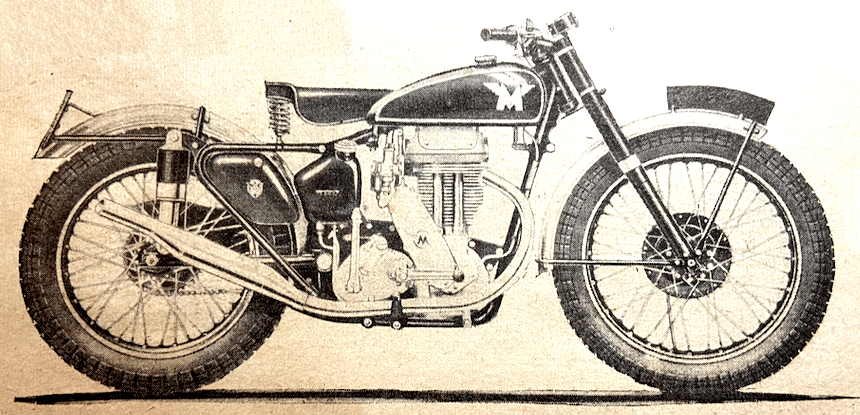

Before Ken Craven gave his name to the ground-breaking fibre-glass luggage gear that became ubiquitous (a pair of Craven panniers adorn the Watsonian QM2 sidecar that’s attached to my beloved GS850; the matching Craven rack and topbox are on the back of my pal Ken’s M21) he and his wife Molly were well known for a series of European tours aboard a series of Matchless singles. Here’s part of his report on a trip through the post-war iron curtain.

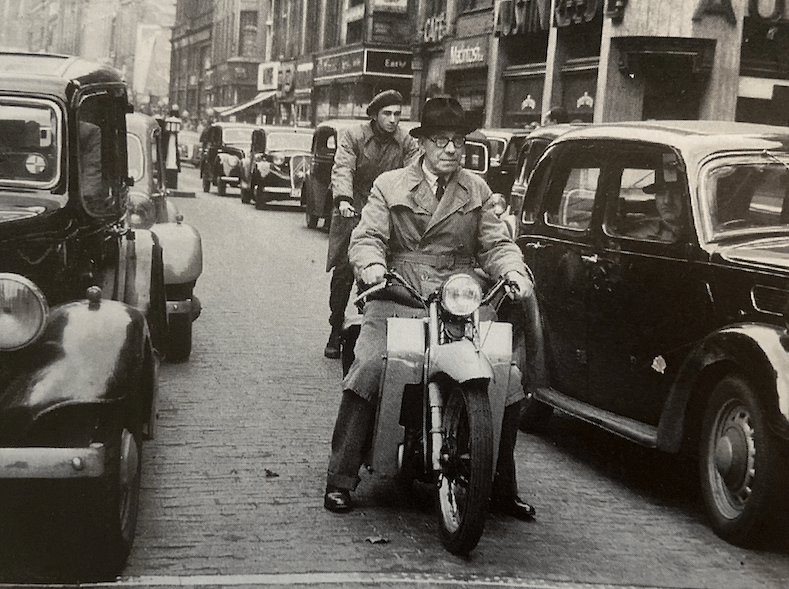

“I DO NOT DOUBT that Vienna was once a very charming city with much to commend it, but now the formal, massively Teutonic facades of the buildings are shabby, and the shrapnel holes have not yet been filled in. For every two blocks which stand structurally intact there is probably one empty shell; looking up through the apertures which were once windows, one sees only the sky beyond. Each is a grim cemetery, for undoubtedly under the rubble the dead still lie, so the grisly reminders of war are still fresh to every visitor. The weather, I will admit, probably had a lot to do with our melancholy impressions. The sky was remorseless, and we had to negotiate wet cobbles and tramlines. After two futile hours’ search for an hotel bedroom we had to hasten round the Ring to visit the British Military authorities. There we filled in a quantity of official forms applying for permission to proceed further through Austria, and to cross the Russian zone to the Czech frontiers. Vienna itself is in the Russian zone, but the central part within the Ring is international territory much as in Berlin and one sees military uniforms of all the Allied nations mingling in the streets. As we left the Military building, we paused on the top of a flight of wet steps to ruminate rather mournfully that the Cravens must be a couple of dim-wits to leave a comfortable home in order to challenge the world—and the weather!—on a motor cycle in search of enlightenment and experience. We noticed poor Hetty III parked across the road, rain-saturated and mud-bespattered, and beside her (as usual, in a Continental country) stood an admirer. This time, however, instead of moving away at our approach, the enthusiast seized us both by the hand and informed us in perfect English that he was a regular reader of The Motor Cycle and knew all about the adventures of Hetty and her predecessors. (She wears a very modest name-plate among her travel badges, and the veteran motor cyclist observers, who inspect a machine from nose to tail, sometimes spot this and recognise it.) This chance encounter made our existence altogether more cheerful, and despite the dampness of my undergarments (for we had travelled through a downpour since dawn that morning), and a pool inside my right boot, I warmed up appreciably. Our acquaintance led us to a nearby café, where the coffee was genuine, and where the cakes were as delicious as they appeared. Being a Viennese himself, he was able to tell us much about the layout of his city, and he made a number of useful suggestions about finding accommodation. He told us that there was the annual Fair in progress, hence the practical impossibility of finding an hotel bedroom. We parted with mutual good wishes, feeling warmer and more confident. Following his advice, we crossed the Danube Canal, leaving the fashionable Ring district behind us, and succeeded in finding a bedroom in a private flat. It was a typical working-class block in a.badly bomb-damaged street near the canal; we climbed several flights of stone stairs to reach it. Hetty was parked among the rubble in the inner courtyard below. Our host and hostess were most hospitable.

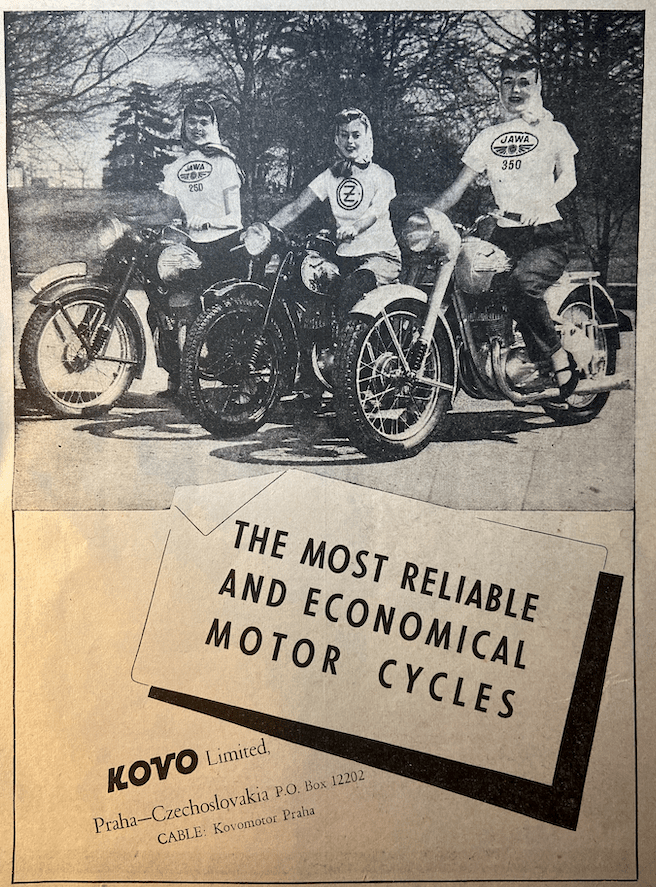

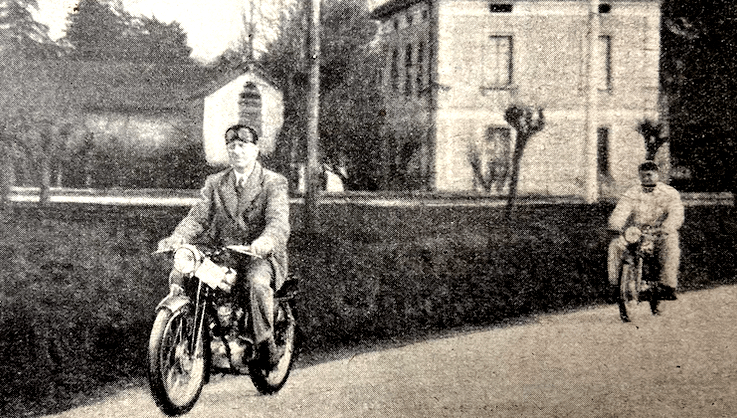

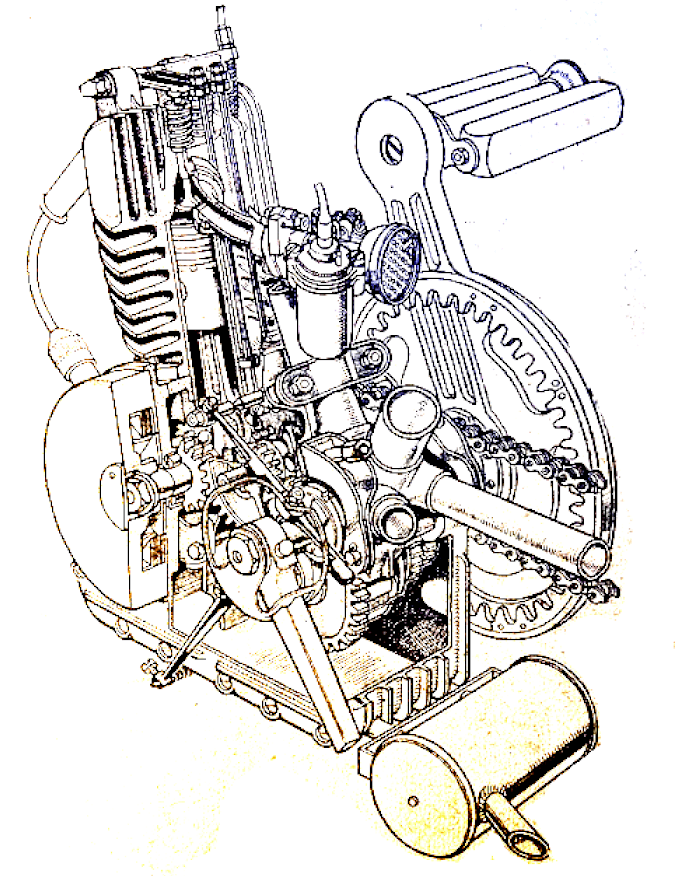

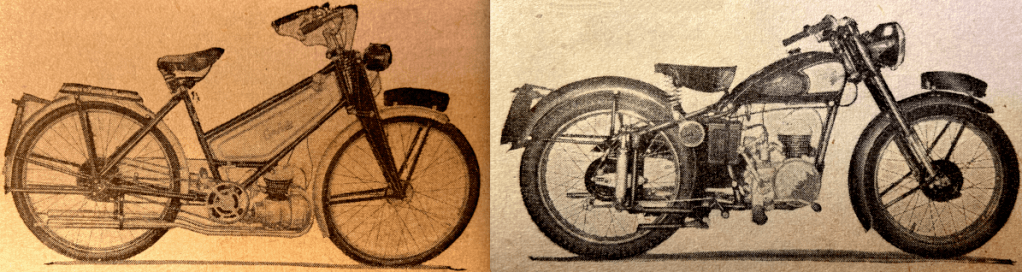

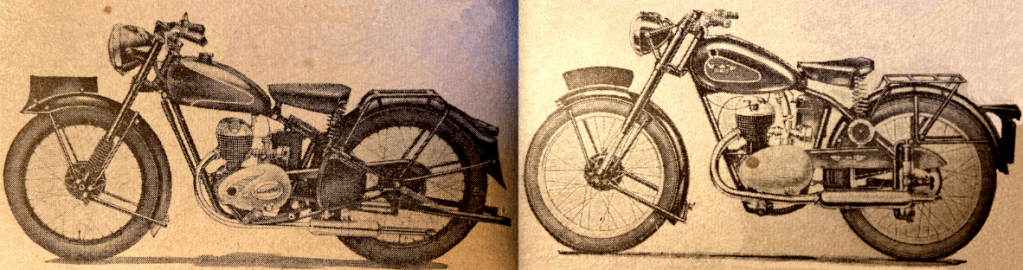

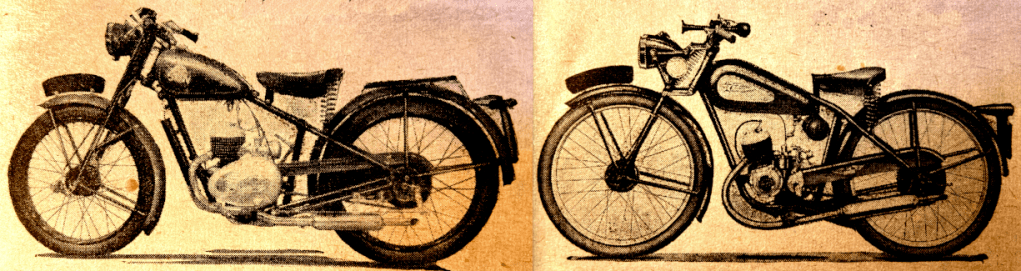

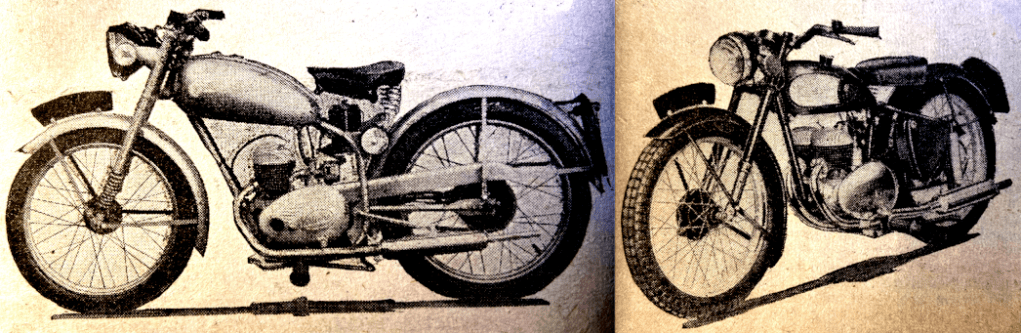

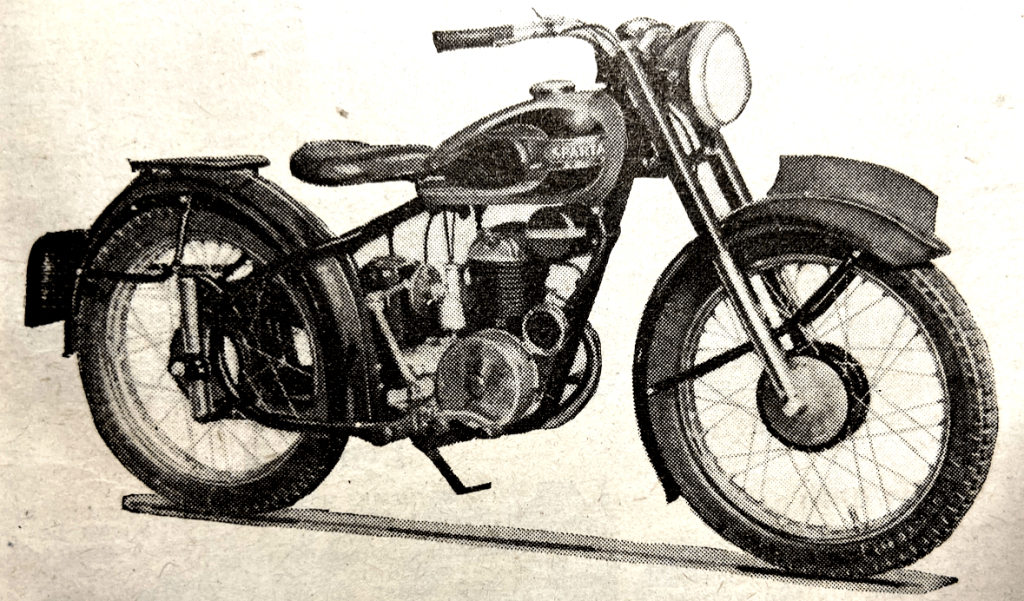

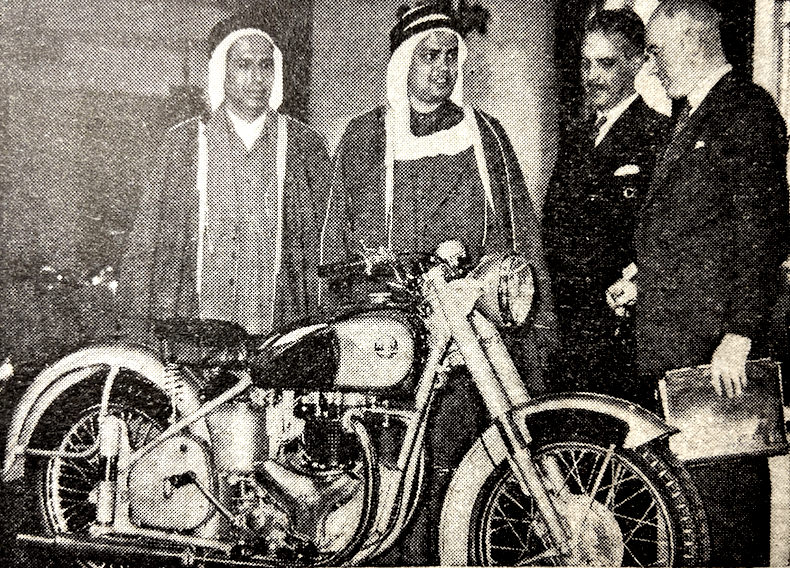

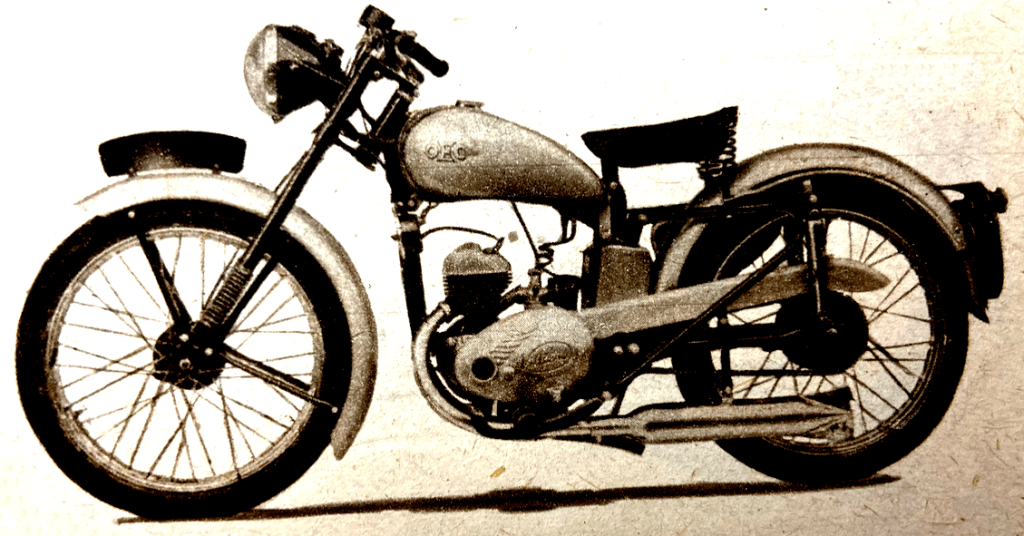

Although fatigued, we spent half the night chatting with them. The fact that they knew no English and that our German is singularly primitive was awkward, but it is amazing how much ground one can cover with the aid of a pocket dictionary and some descriptive gestures! Contrary to the gloomy warnings from British officials on both sides of the Channel to the effect that the Russians would keep us waiting several days in Vienna for our transit permits, our passes came through within 24 hours. After a good night’s sleep in a miraculously ornate bed we packed our kit, persuaded our hosts to accept a very modest charge when they seemed unwilling to touch a shilling, and finally waved them goodbye. The Danube proper is only touched by the outlying fringes of Vienna, and, having crossed over the spans of the long bridge we ambled onward over flattish country, where the well-tilled fields appeared, quite oddly, to be almost devoid of peasantry. Nor was there any other traffic on the smooth surface of the highway except for an occasional ox-cart with the driver sound asleep. The villages seemed drowsy on a September day which was, happily, clear and pleasant. Far from other habitations, we came to the frontier barrier; a couple of gates interrupted the unchanging strip of road. We had to knock at the door of the guardroom to receive attention, for the officials inside were engrossed in a game of chess. Although affable enough they were glad to despatch us promptly so as to cause the minimum distraction from their earnest struggle of wits. The reception at the Czech immigration offices on the other side of no-man’s-land was altogether different, for we were soon to discover that we were in a country where nearly every citizen from the age of about four upward is a keen motor cycle enthusiast; and this will serve as a part-explanation of our many delightful experiences during the two weeks which we spent exploring the Republic. On this occasion, the arrival of a couple of visitors at the frontier with an English motor cycle, of a design which they had not previously encountered, caused a lot of jovial interest. The four officials, with obvious good will, questioned us simultaneously in their Slav language which, even if spoken very slowly by one person, is to us completely incomprehensible. Although there is no defined natural frontier between the two countries, there is an immediate and striking contrast in the village life. Whereas Austrian villages are compact, the ornate steeple of the church protruding from a central cluster of buildings, the communities we saw now were mostly of one-storeyed dwellings of white or colour wash, extending ribbon-wise along each side of the road. Every settlement has its pond or small lake fringed with reeds and willows and forming an attractive part of the landscape, whether glittering. in the sun or dark with shadows. We noticed after entering Czechoslovakia that the roads began to be more populated, mostly by motor cycles. As we neared Prague at mid-day the swarms of motor cycles became quite dense and the hum and popping of two-strokes could be heard down every side-turning. It was a Saturday, and the population was airing itself on Jawas, CZs and Manets. Many of the riders went into a mild wobble of excitement on being overtaken by a British machine—a sight which these enthusiasts rarely see. Modern Prague, that is the city which has grown up since the turn of the century, and where the bulk of the population live and work, is almost uniformly grey and of a somewhat heavy style of architecture. The industrial suburbs are very smoky and the cobbled roads treacherously full of tramlines, over which we, and the swarming Jawas, slithered helplessly. The next day was a Sunday, and we decided to pass our time profitably with a visit to the Prague International Fair. The crowds were dense in the motor cycle section, where the manufacturers had certainly shown imagination in the display of their well-proven, but nevertheless limited, range of models. One of the stands served as a demonstration Service Department where, by appointment, any rider could bring his model in for repair, and, whether it involved electrics or a big-end, the charge was only for the cost of the new components. The manager of the section spoke English, and he pleaded with me to bring the Matchless to the back of his pavilion for inspection. It so happened that when I brought the machine to the door the spring of the prop-stand came adrift. This is a minor, recurring failure which can be remedied within thirty seconds with the aid of a pair of pliers. On this occasion, however, it was a heaven-sent opportunity for the Service Department! Ignoring my protests, they happily wheeled in the model and there, before the multitude, it was heaved on to the repair bench. Whisked up from nowhere, a Press photographer promptly appeared, complete with flash-bulbs, and Mollie and I found ourselves looking into the lens of the camera. We smirked, adjusted our scarves, and twiddled self-consciously with our clothing—only to be put firmly aside with a friendly shove or two, while our place was taken by three mechanics armed with an array of tools! So, when the flash-bulbs recorded the scene, our maligned Hetty was receiving the skilled attention of admiring mechanics, with a back-ground of enthralled spectators. This introduction led to various social engagements with the hospitable Czechs which lasted until late at night. On Monday we visited the Autoklub to claim the post which had been locked up there for us, and found a surprise letter from the Assistant Editor of Motocykl, whose office is in the same building. Hanus, who became our guardian angel on a lavish scale, had come to England as a boy when Hitler invaded his country. We met him at his desk—in shirt-sleeves, hair awry, and surrounded by piles of manuscripts, maps and photographs, together with six used coffee-cups. He made most helpful arrangements for our visit to the Jawa motor cycle factory, fixed up a test-ride on a new machine, and made available for our use a Jawa and a CZ if we should require them. ‘And lunch will be waiting for us in the Club dining-room in half

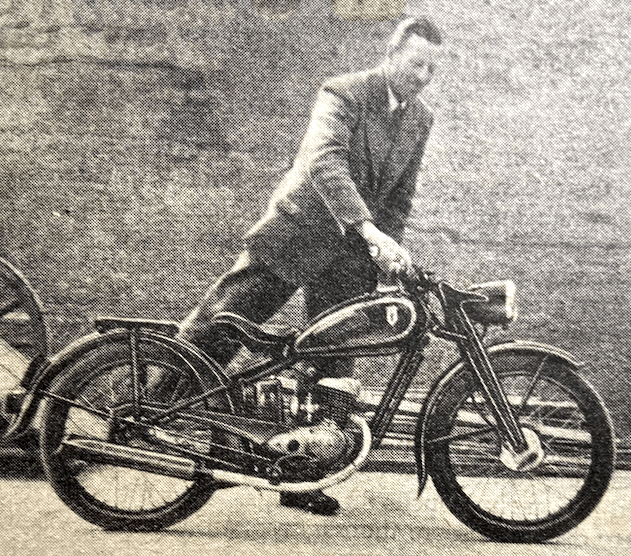

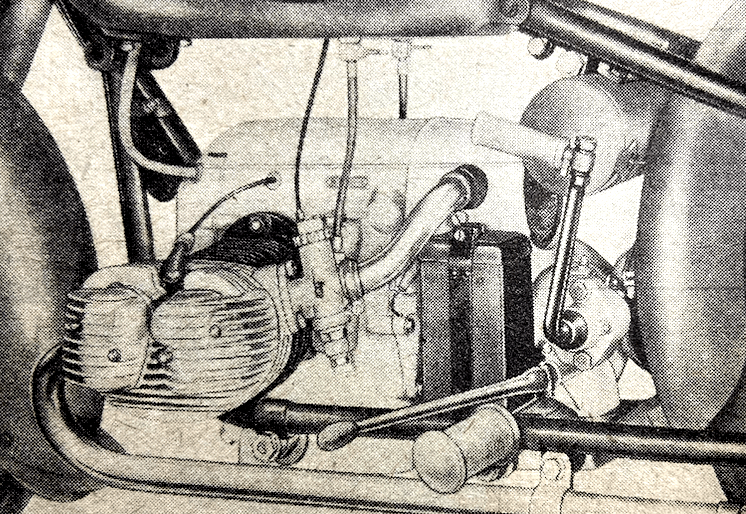

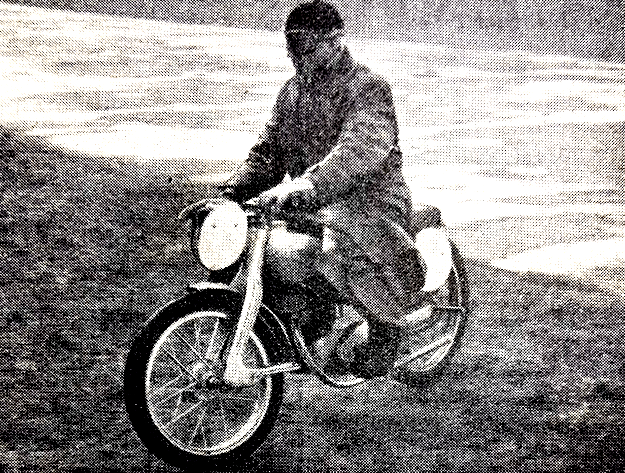

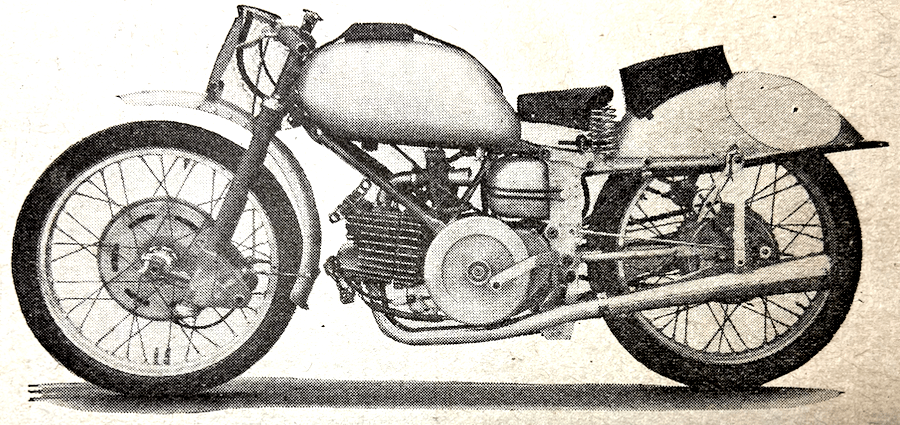

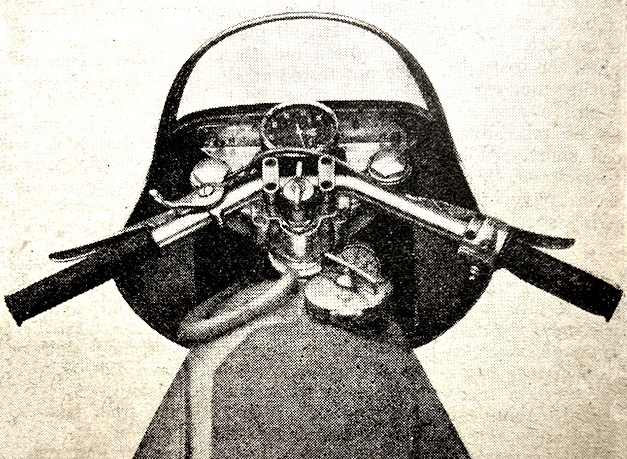

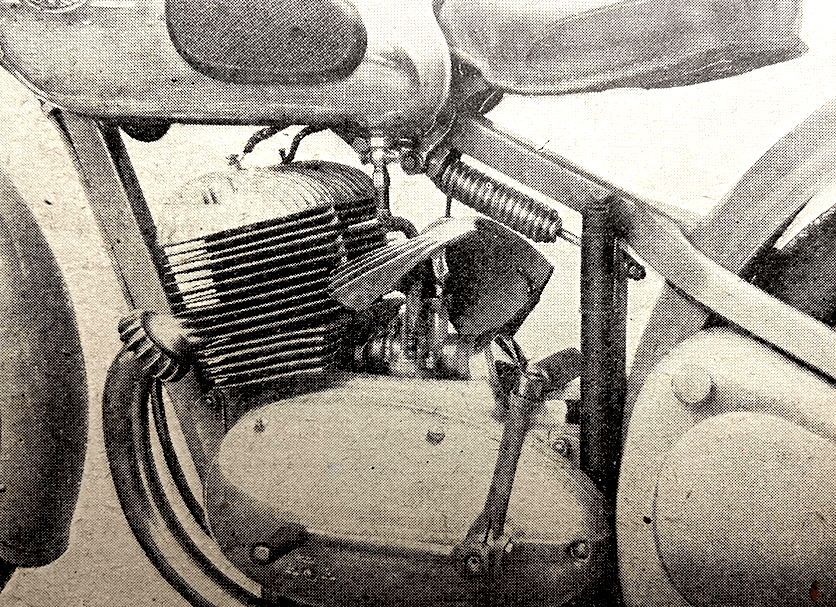

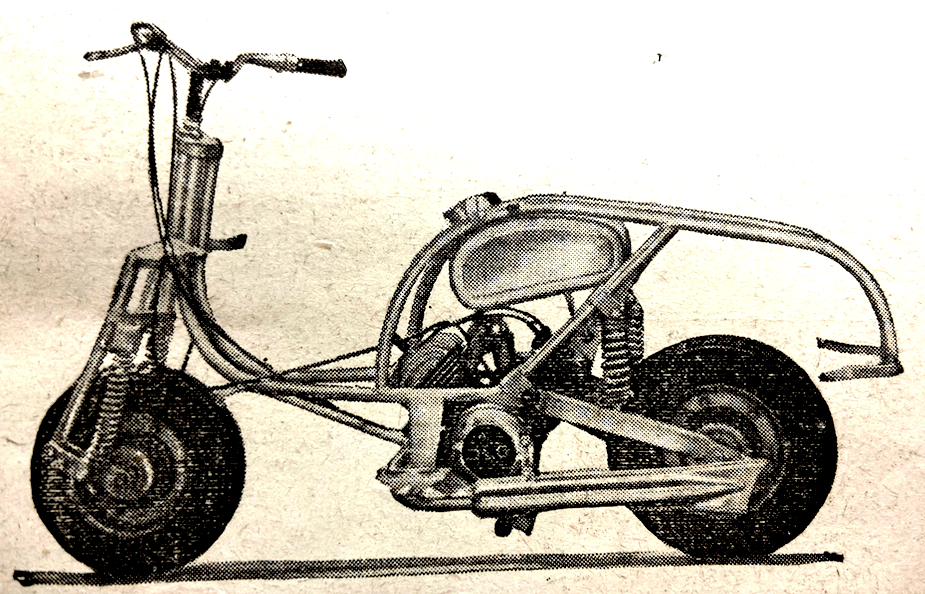

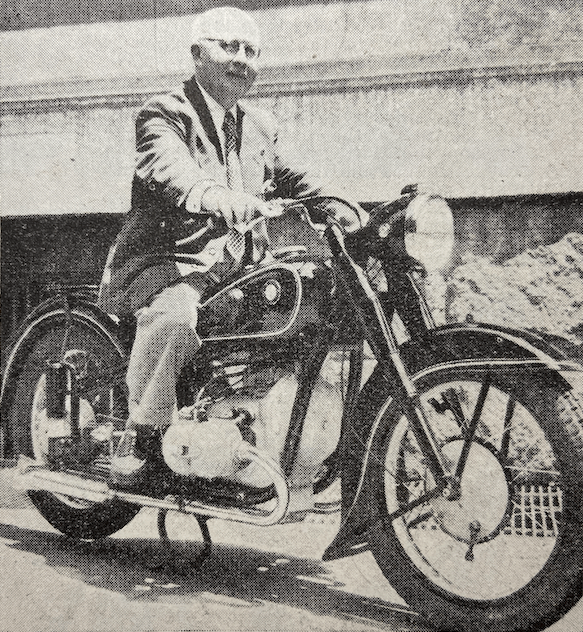

an hour,’ he concluded. The visit to Jawas disclosed that they are not going to sleep on their existing range. I was shown a well-worn sidecar outfit which was one of five versions undergoing a prolonged test. This particular one was an overhead-camshaft 500cc vertical-twin; there was no external indication of the means of transmission to the camshaft. None of the secrets was explained to me, though I could see that the machine was full of interesting points. The power unit conformed to established Jawa practice, with only the cylinders protruding above the neat, egg-shaped crankcase. One of the standard 350cc twins which had just been run-in was wheeled out of the plant, and I was asked to take it out on the road and give my impressions. Despite the fact that I did not feel entirely confident (owing to the foot brake and gear lever being in reversed positions to those on English machines) I found her road-handling to be perfect and the turbine-like power was a revelation. With the engine pulling, the silky exhaust note was most restful, but on deceleration a cackle developed from four-stroking, and I found this unaccustomed sound disturbing. Also, I considered that there should be more movement in the front fork; but apart from these minor criticisms, I had no fault to find with the trim and handy little machine. Since my praise for the model obviously pleased the engineers, my few criticisms were accepted in good part. I was sold the story of how the current 250cc Jawa came to be developed. This, in its way, is one of the great Resistance stories of the Occupation. A handful of enthusiasts met in secret and drew up a tentative design for an ideal two-stroke machine. Partly in defiance of the Germans, and partly to bolster up their own confidence that ultimately the invader would be expelled, they devised a plan to produce a number of prototypes so that a fully tested model would be available for full production when the time was ripe. Most of the Jawa works were producing munitions under Nazi control, but there was one shop given over to major repairs on German DR machines. Here, despite the presence of Nazi overseers, the components were secretly produced, and, one at a time, the models were assembled in the least conspicuous comer of the work-room. In all, five prototypes were built in this way. They were disguised as much as possible with khaki paint and DKW emblems and gadgets. They were smuggled out to different parts of the country, where they were given exhaustive tests (at the peril of their riders’ lives) and returned from time to time for modification. What courage and organisation! The work of those heroes has influenced lightweight design throughout the world.”

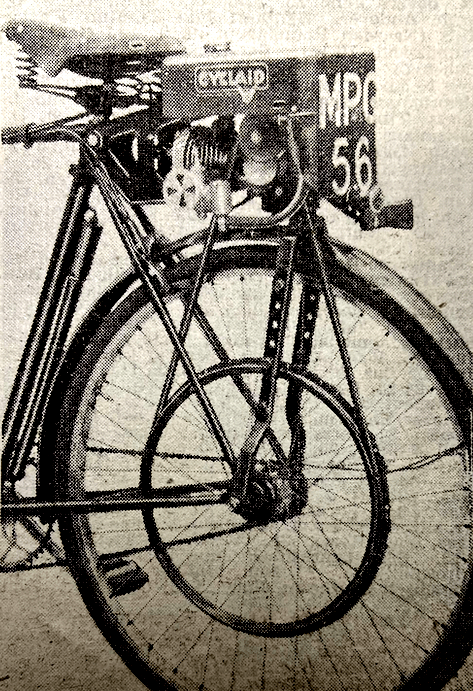

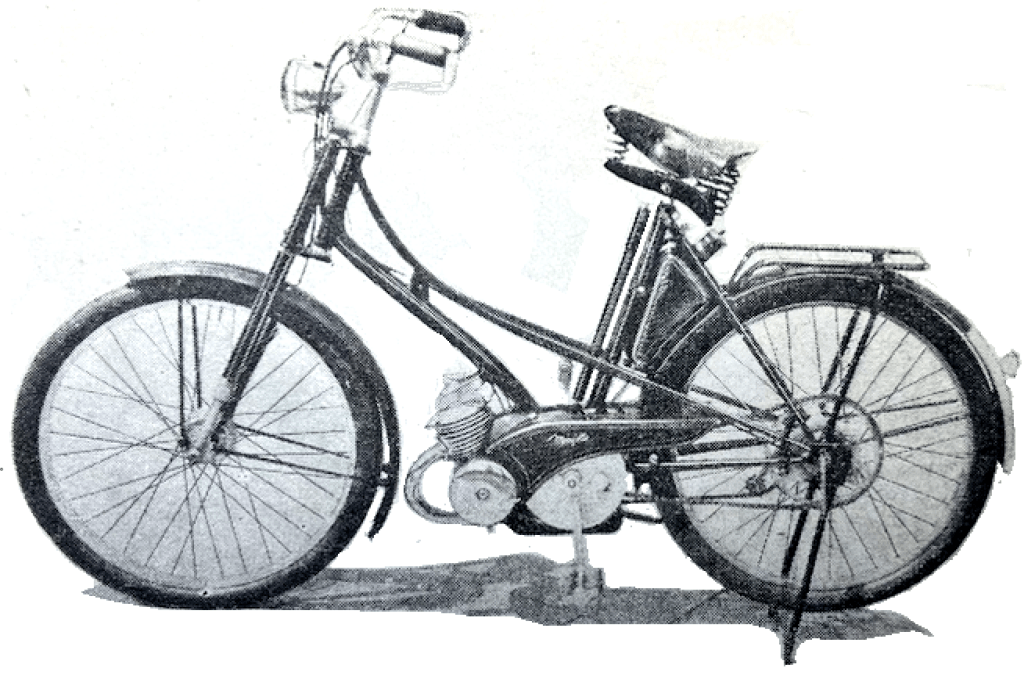

“LAST AUGUST I FITTED a 50cc engine to an old, but sound, lightweight bicycle frame that had seen many years road racing before becoming a hack machine. It had 15swg spokes and a coaster brake. The rear tyre was a new ‘War Grade’ 26×1.25in Tandem. We travelled by ship to Dieppe, and my wife, with about 20lb of luggage, proceeded to ride across France to Switzerland. Our son and I, on a racing tandem, endeavoured to keep pace. This was easily managed on the level, but gradients showed that 50cc are more than the equal of a fit man, and, on the long climb to La Cure at the Swiss border, and again over the Col de Pillon, we were left far behind while the missus with light pedal assistance (it had to be light, as only one lung is working properly) pottered merrily along to wait for us at the various summits. On the sweeping downgrades the engine was used as an additional brake. An enjoyable holiday was spent which would have been impossible without that 4hp assistance. The only mechanical incidents were a choked jet and the silencer knocked off. This did not seem to matter abroad, but I must confess to some uneasiness as we came into London late at night. Fortunately, however, there were no complications. Since then the machine has made several trips to the coast at averages of better than 20mph, and I now use it for visiting out-of-the-way country places in the course of my work, which ranges from Devon to Northumberland. On the longer journeys I go to the base by train, and so for I have only paid cycle rates for carriage. Tyre wear is not excessive, after over 2,000 there is still tread on the tyre and there have been no punctures yet. Sitting still, doing 22-25mph, is very boring; I would rather cycle at 18-20mph or motor cycle at 45-50mph…I am thinking of springing both wheels. For the utility rider, the 50cc engine would appear to be an inestimable boon. One great advantage is that in the rain one can wrap up and sit still. On a pedal-cycle, movement keeps the wet outer garments flapping back, exposing the legs in particular, and the physical effort means, as often as not, that one is as wet or wetter from perspiration as from the actual rain. Full motor cycle kit is necessary for comfort, but one feels self-conscious dressed like a man from Mars on 50cc. Hill-climbing is adequate, and 1 in 9 and even 1 in 8 ascents have been climbed with pedal assistance. Some form of gearing would more than outweigh the extra cost.

HAROLD FB CARTER, London, SE6.”

“IN VARIOUS ARTICLES and letters to The Motor Cycle people have advocated enclosure for neatness and ease of cleaning. Surely this is like sweeping the dirt under the mat, and makes life more difficult and maintenance loathsome? As a motor mechanic I have first hand knowledge of the polished exteriors that hide filthy and forgotten working units (out of sight, out of mind)…enclosure does not mean cleanliness in the correct place, Anyway, why the timidity towards a hose for washing down? My present 5T Triumph and previous Norton have never been any trouble to clean, because I always use a good paraffin wash and a final pressure hosing. Providing discretion is used (you naturally avoid pushing a high-pressure water jet straight into the mouth of the carburettor and into other vulnerable parts), the indirect spray doesn’t cause any trouble as most bikes are storm-proof. One can usually ride off from the wash-place without first tearing the model to pieces to dry it out. The most I’ve ever had to do is to wipe the plug porcelain—a very small amount of trouble to pay for a quick and easy clean-up; and I do mean clean.

TMF969, Cowley, Middlesex.”

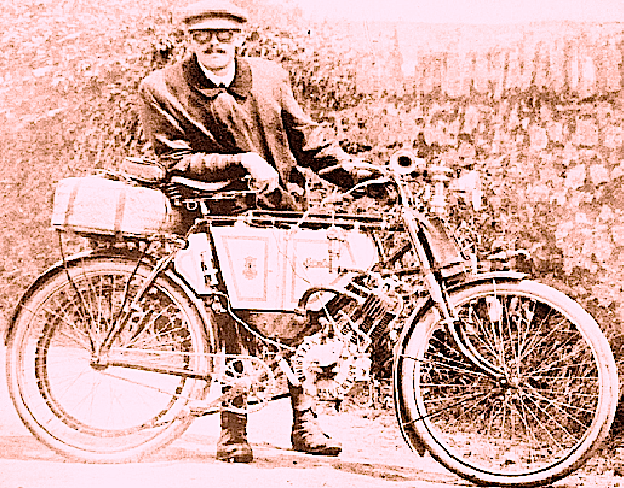

“YOUR CORRESPONDENT Mr G. Wilkinson has evidently no personal experience of motor cycling in the middle ’20s, or he would not be so dogmatic regarding motor cycle deficiencies in those days. To say that a no-trouble run of 100 miles in those days was something of an achievement is, in Mr. Wilkinson’s own terms, the ‘piffle’ in this expression of opinions. I regularly covered such distances, and greater ones, between 1922 and 1929, and I should like to assure Mr. Wilkinson that, as an ‘average’ rider, I not only invariably arrived in good time, but fully relied on doing so. May I quote, by way of example, a .journey of 345 miles in 1927, completed in 11½ hours, including all stops, at an average speed of 30mph on a 500cc sidecar outfit? And a twin, Mr Wilkinson! Could a modern equivalent outfit substantially improve on this performance, which I will, if required, substantiate with full details? (But don’t let’s start an average speed competition.) Yes, the Scotts, James, Douglas machines, and many others of those days, were good machines with almost the reliability of the modern ones. In my opinion, the improvements leading to slightly greater reliability over the past 25 years have been in the adoption of the better metals available to motor cycle design—metals now resistant to fatigue, failure and shock fracture, with consequent lowered risk of a major failure on the road. There seems to me to have been relatively little advance in important details, such as clutch and throttle cables, which detract from any increased reliability of the modern machine compared with those of 25 years ago. This absence of progress in important detail was a surprise to me on resuming motor cycling after a lapse of 18 years; and may I remind the ‘piffle’ purveyor that Velocettes still win races on girder forks? Fundamental improvements there have undoubtedly. been, and all have welcomed them, but do not 1et us decry the performance and abilities of the early and middle ’20s machines, which may truly be described as ‘vintage’

MET, Newcastle.”

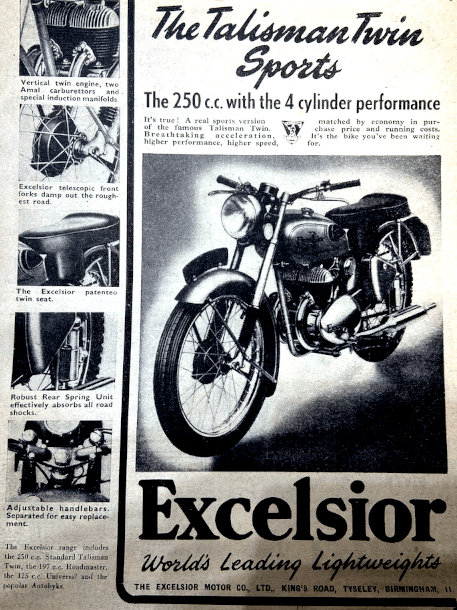

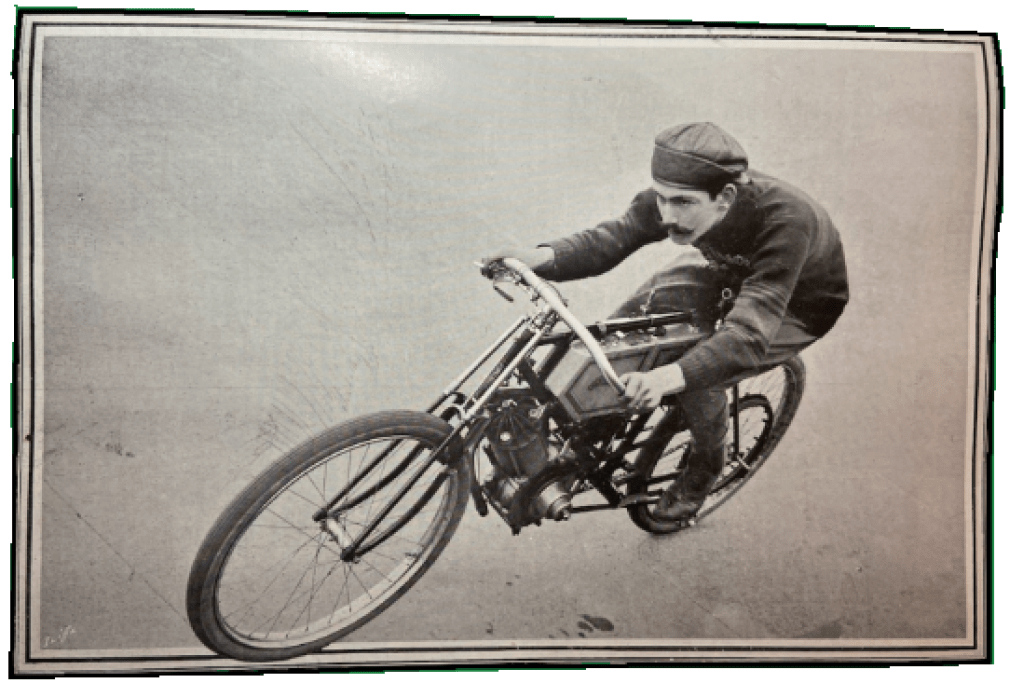

“SPEED WIZARD in the earliest days of motor cycles, and designer, manufacturer and rider, Harry Martin, whose experience in the trade dates back to 1896 and 1897, has joined Excelsiors and will be acting as Liaison Officer visiting dealers in North London, Middlesex, Hertfordshire and Essex. Harry is now in his 74th year and rides an Autobyk daily.”

“HARRY HINTON, the famous Australian racing man, who made such a hit in British and Continental races last year riding Norton machines, won both Senior and Junior Races in the Australian TT and made fastest lap in both. He was Norton mounted in the races.”

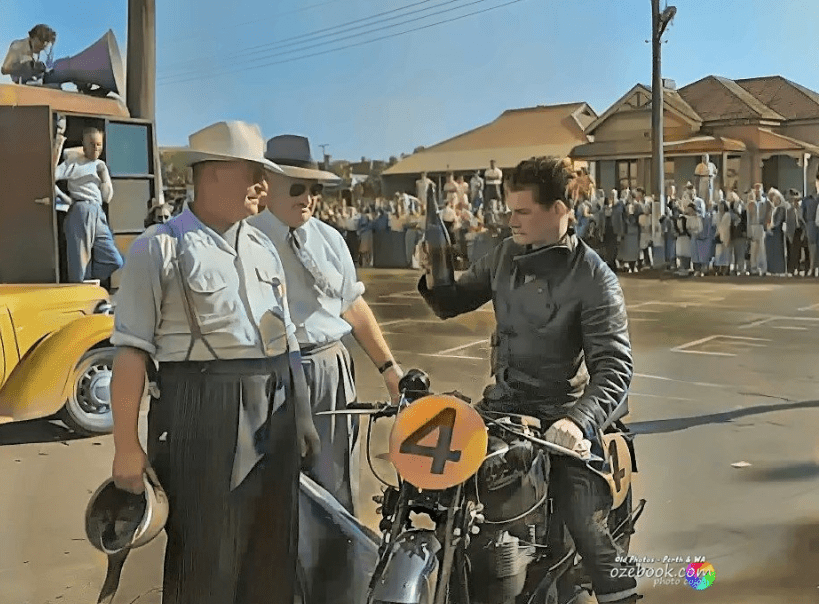

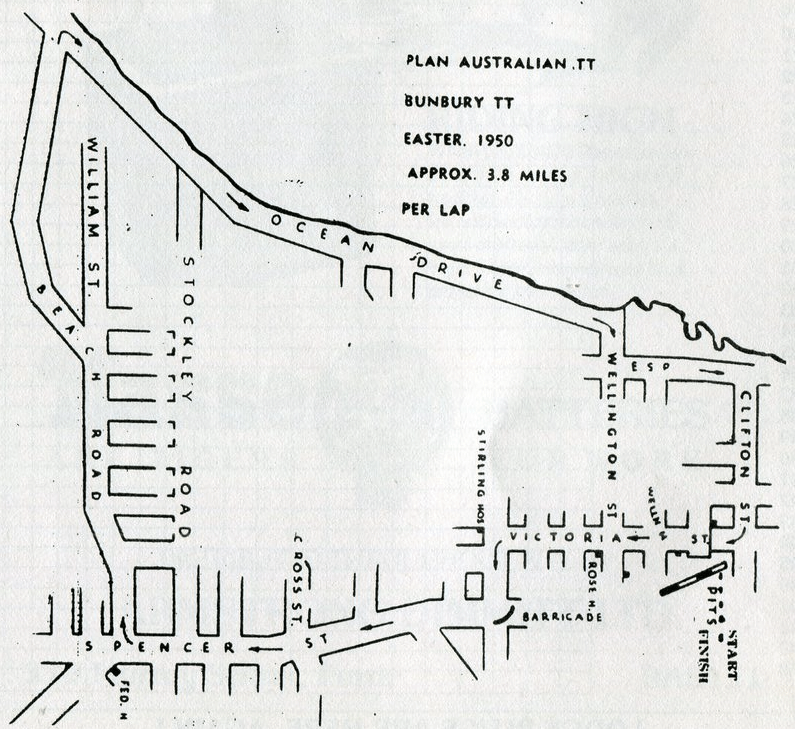

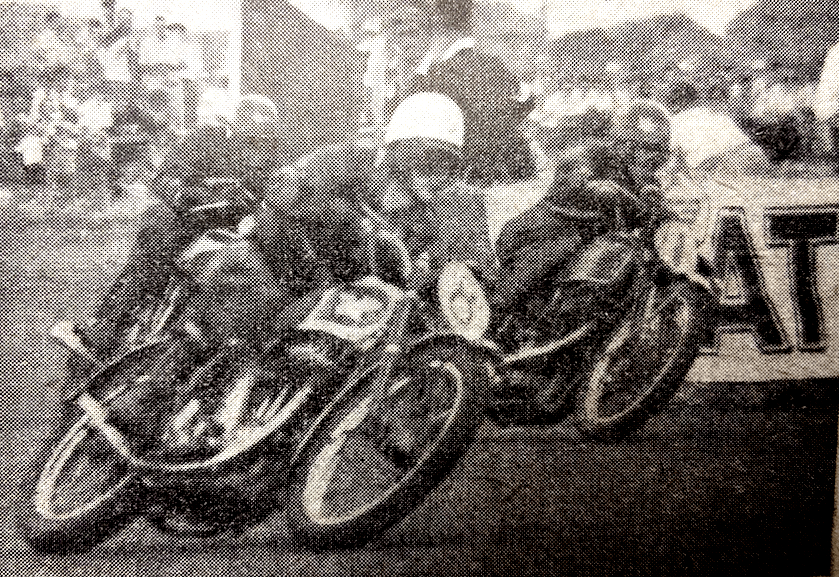

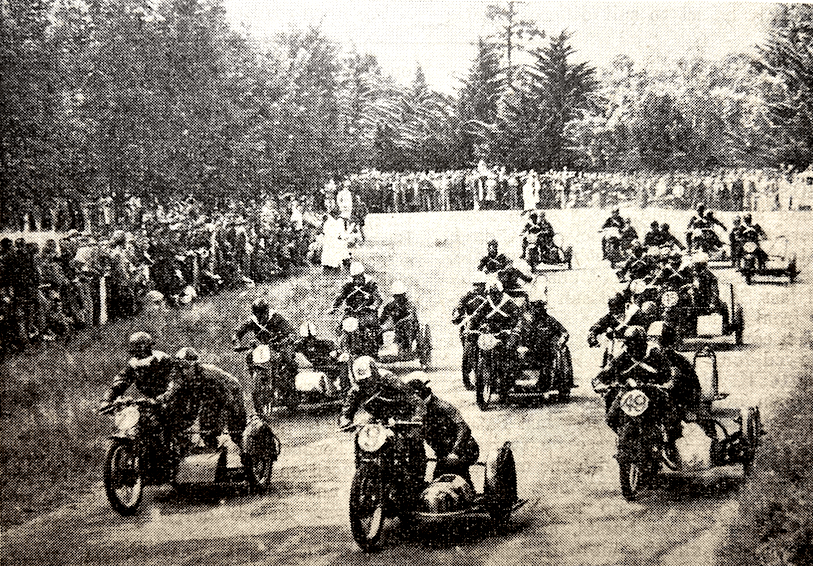

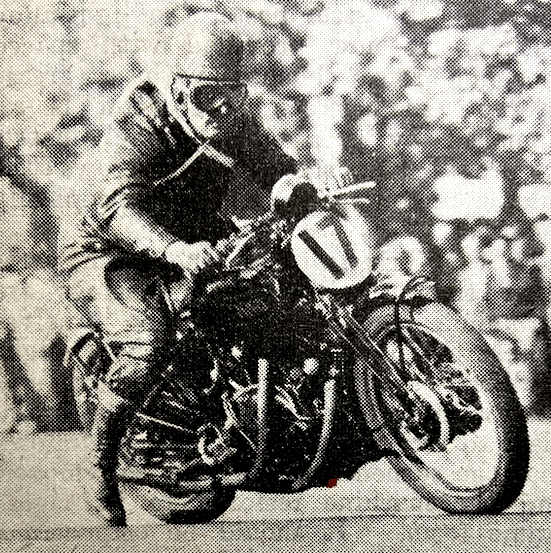

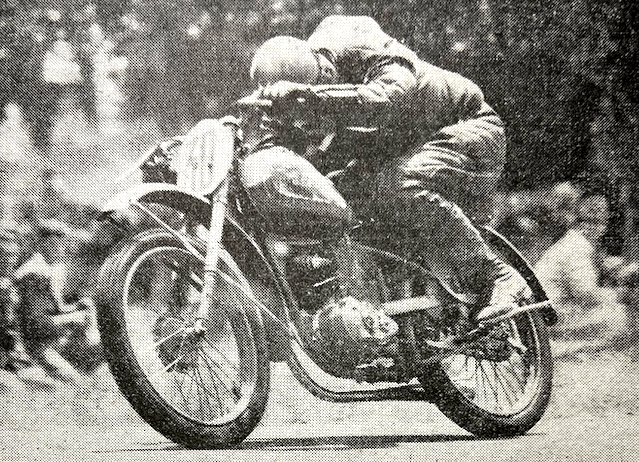

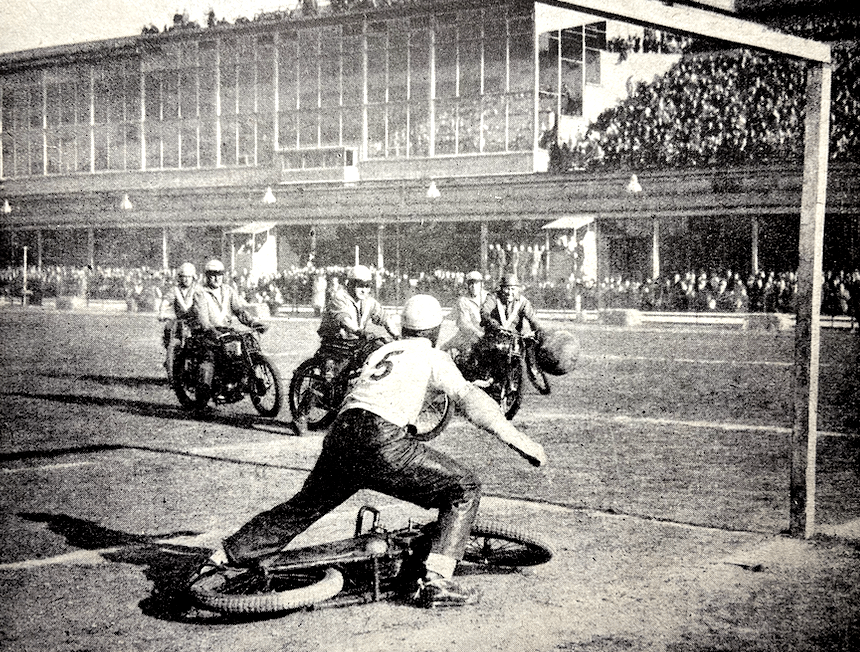

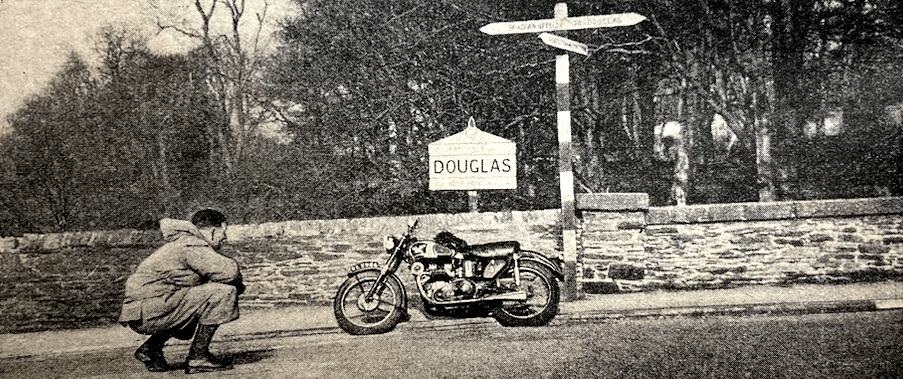

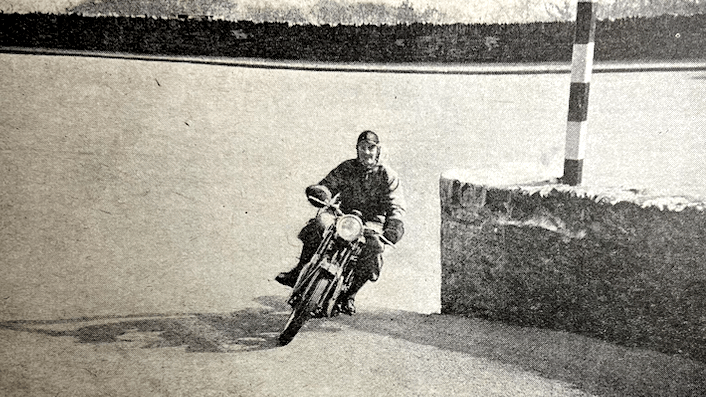

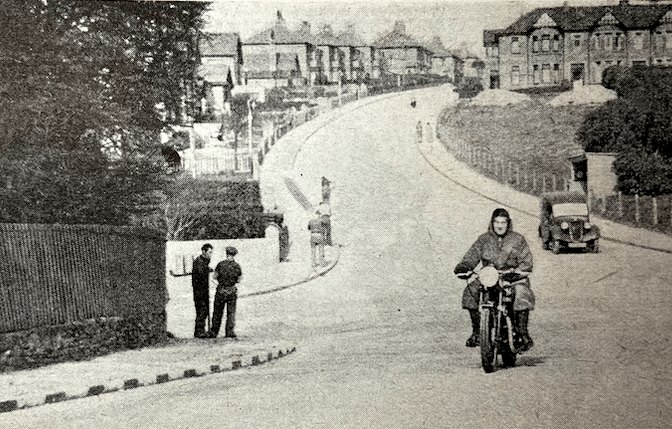

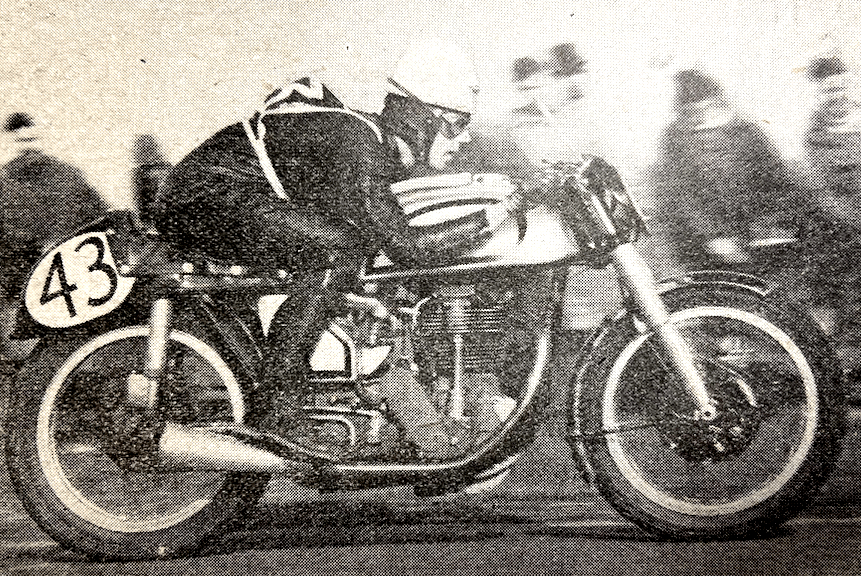

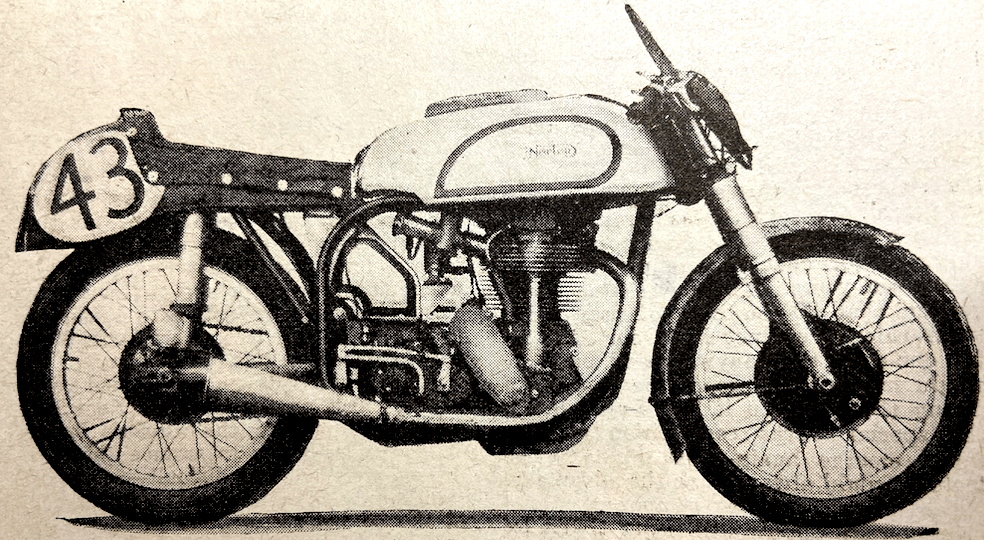

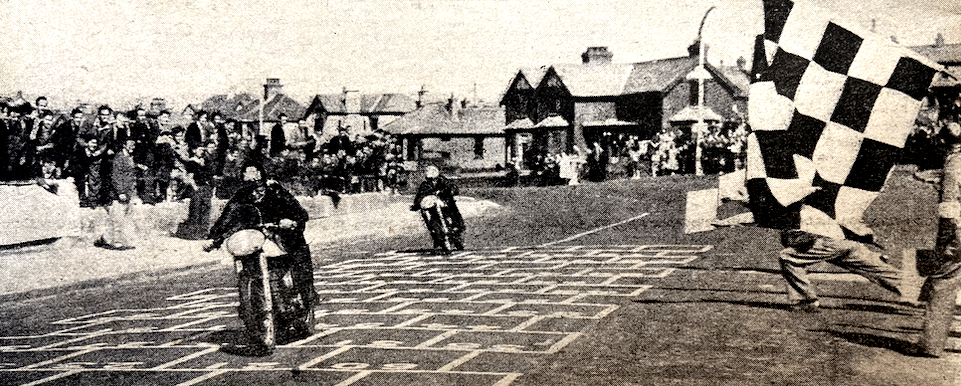

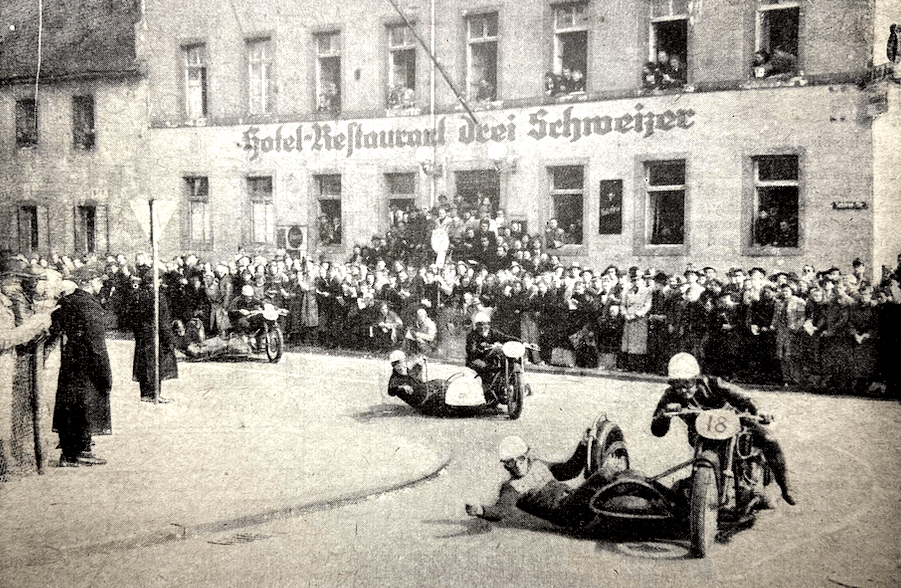

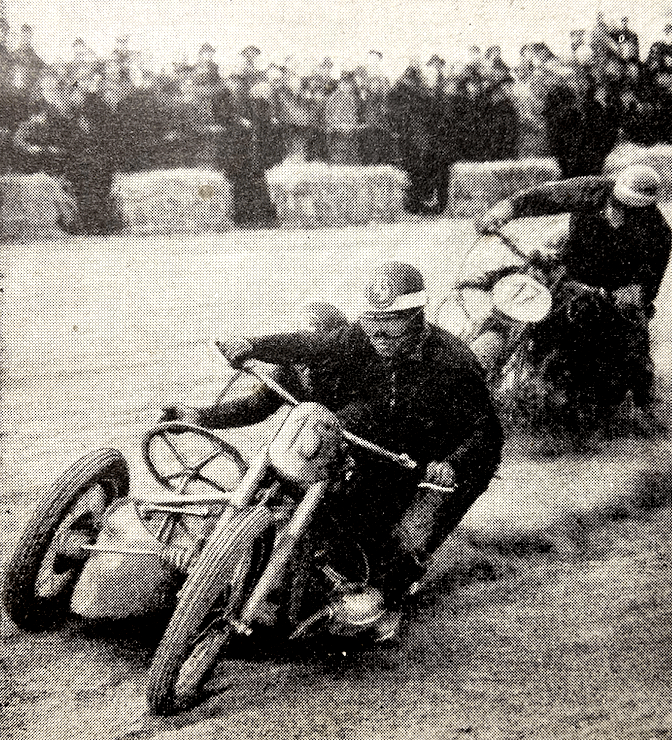

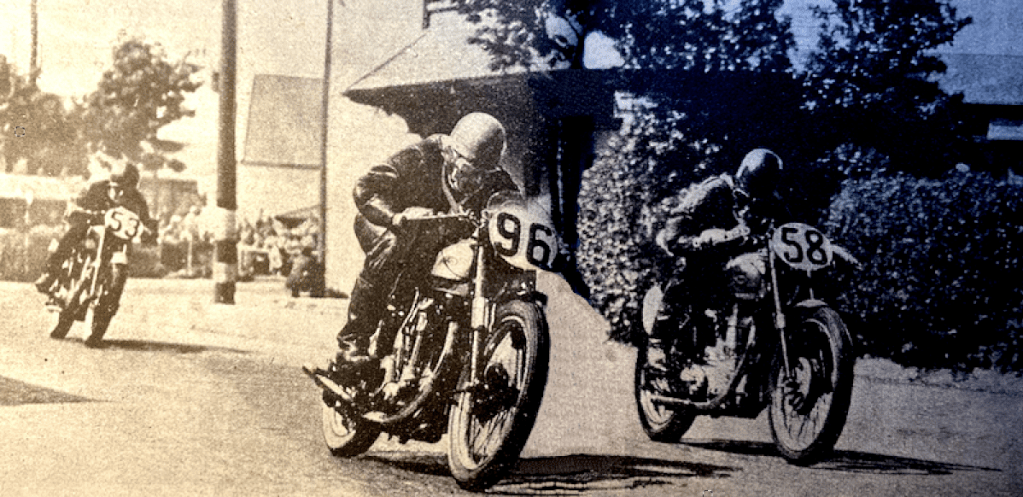

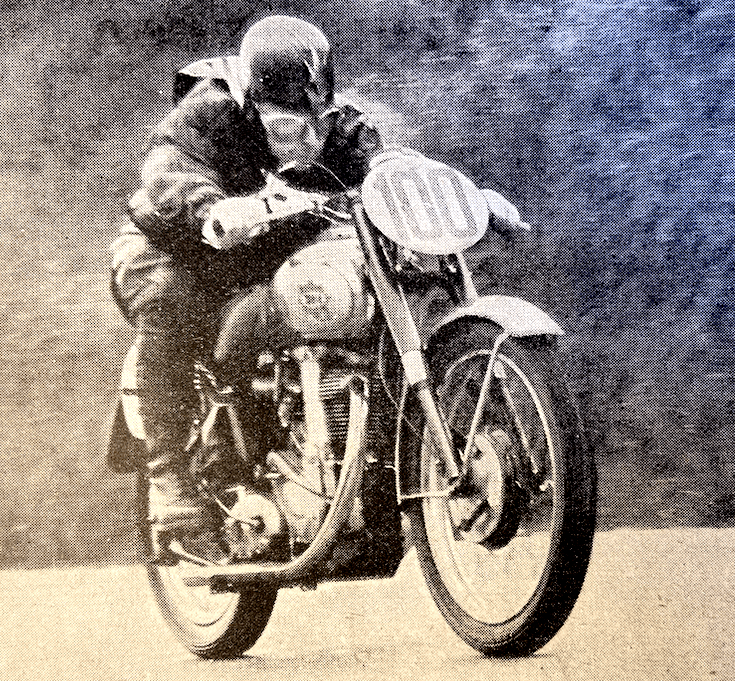

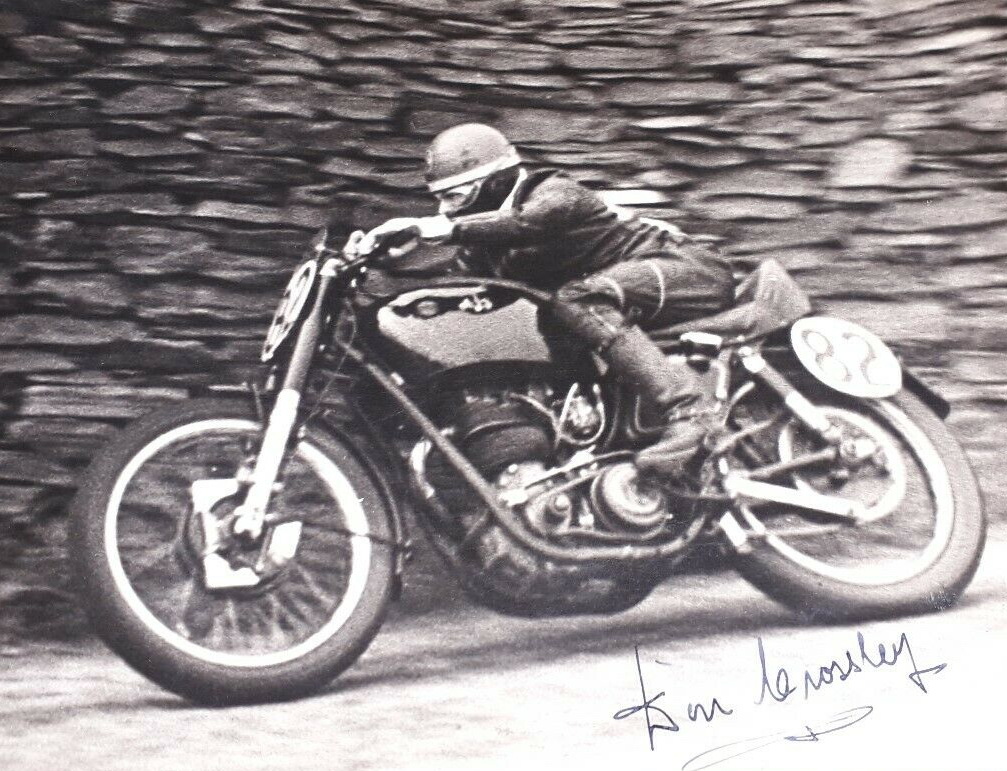

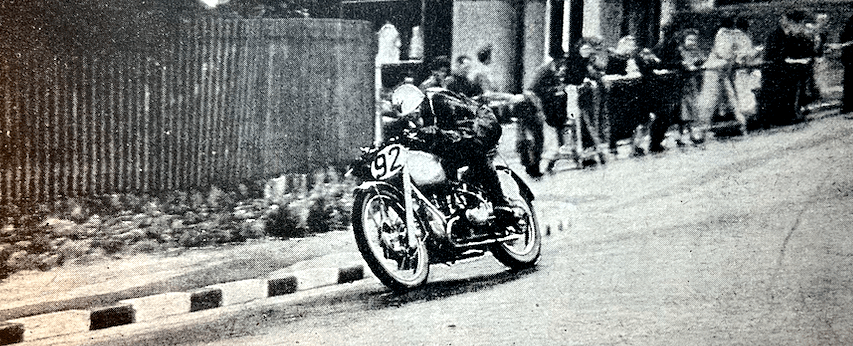

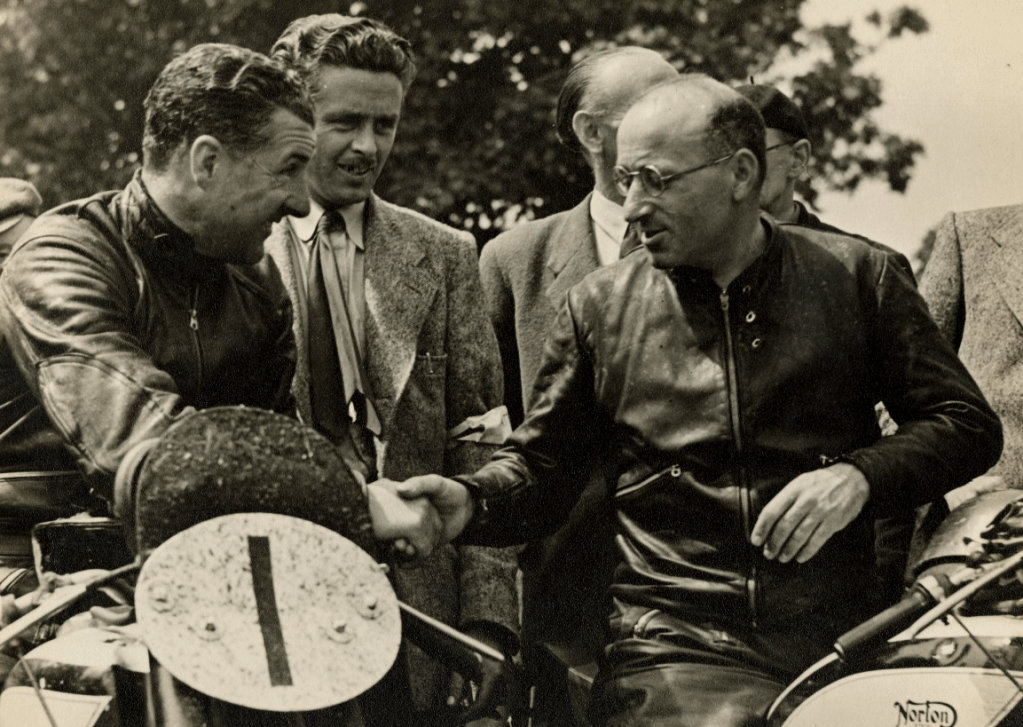

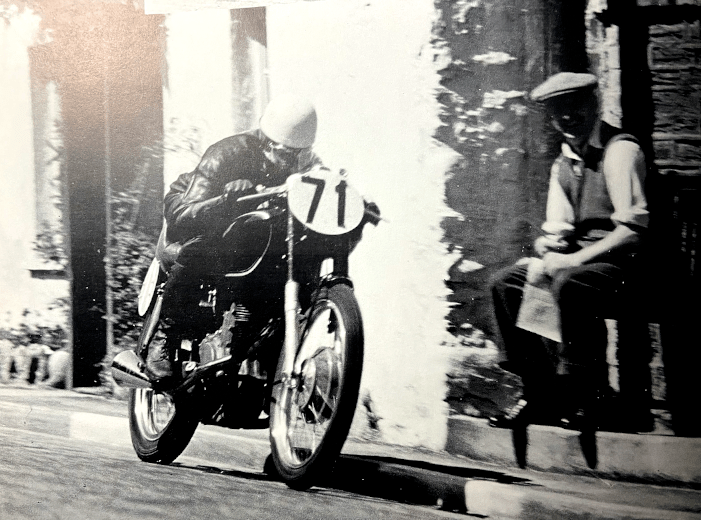

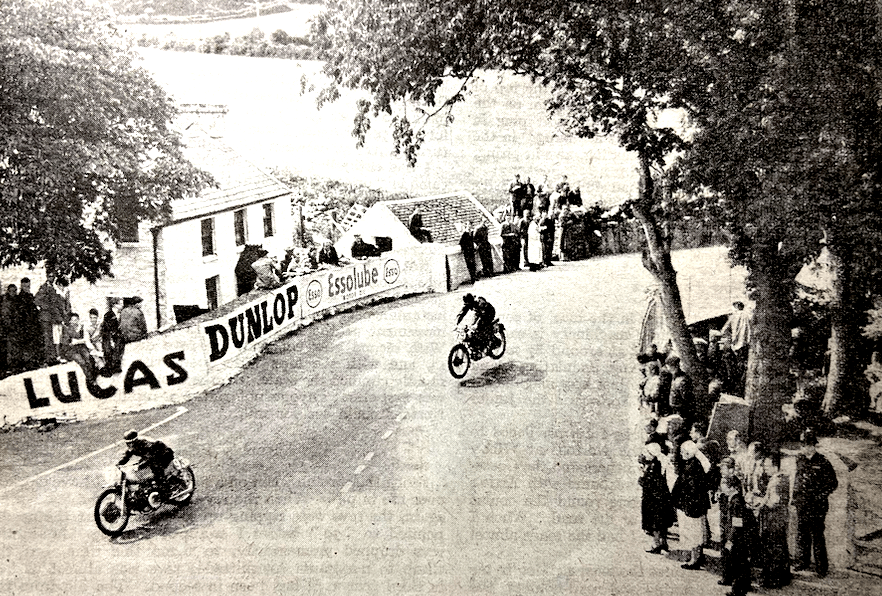

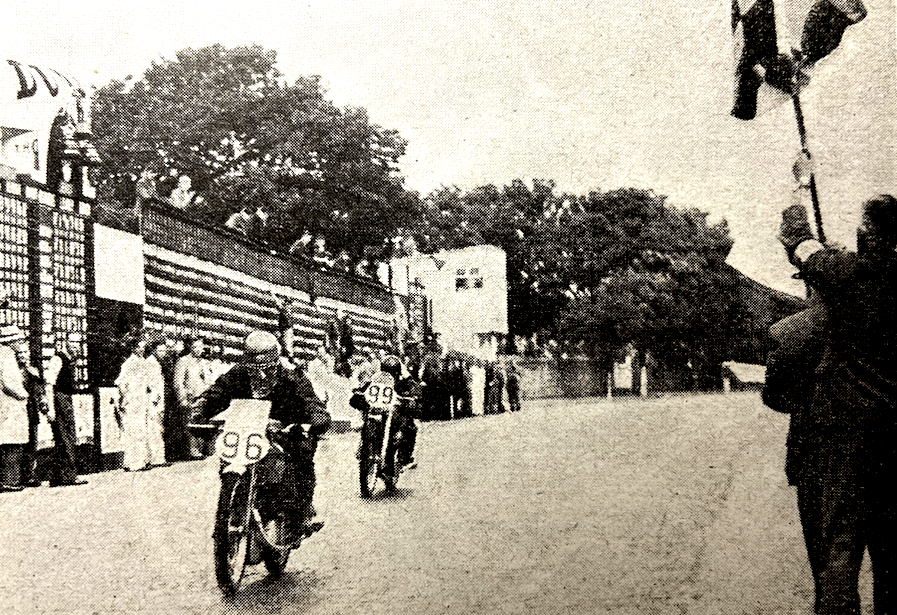

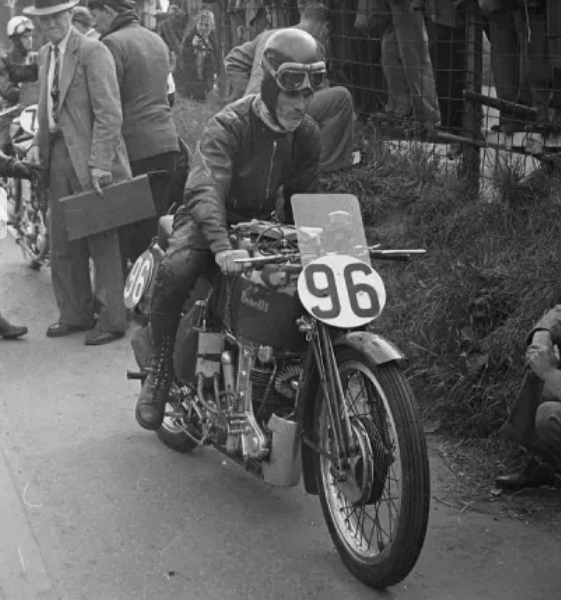

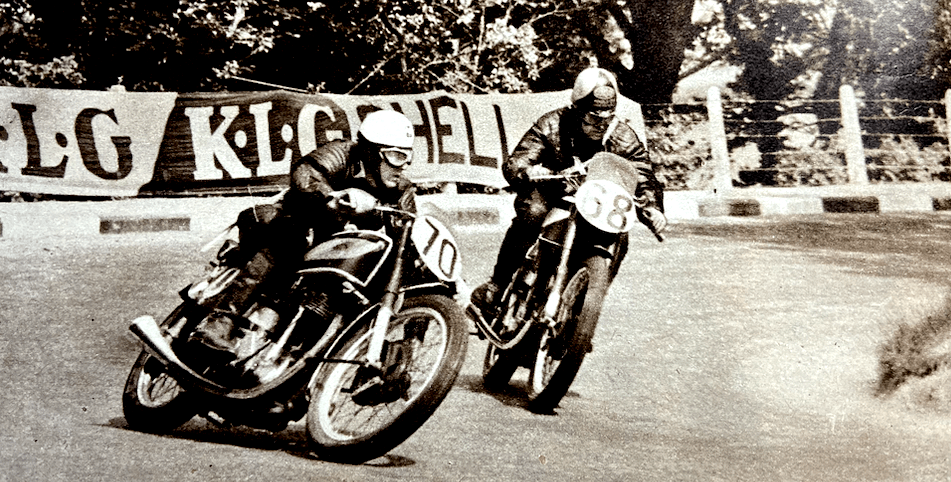

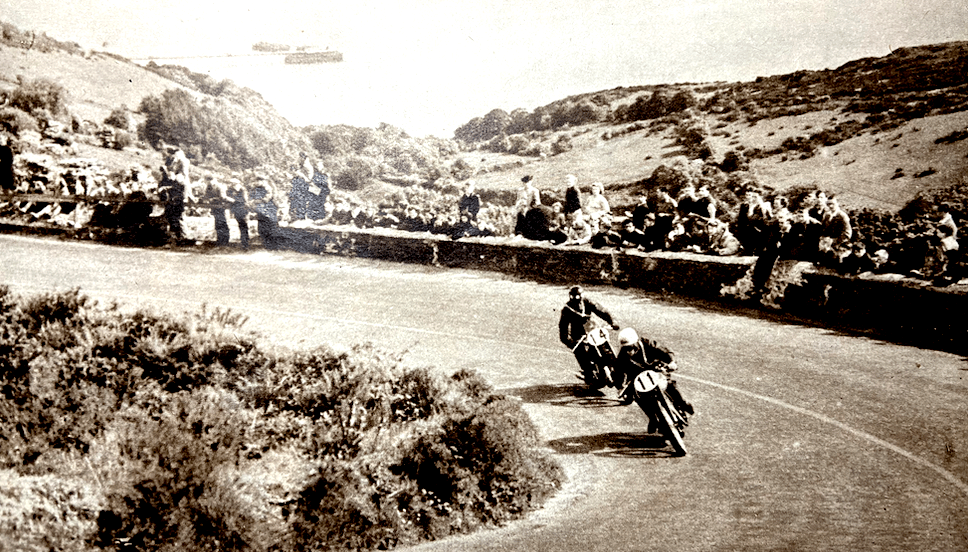

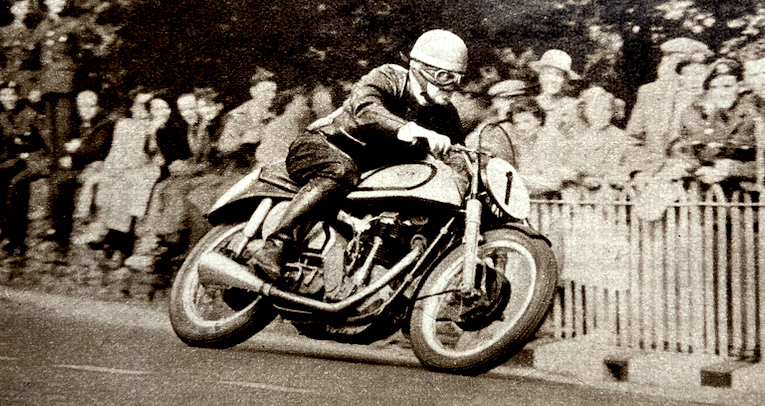

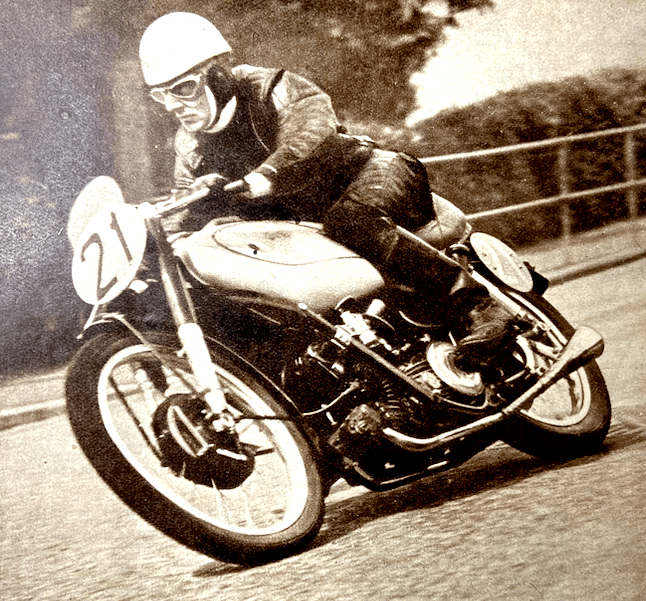

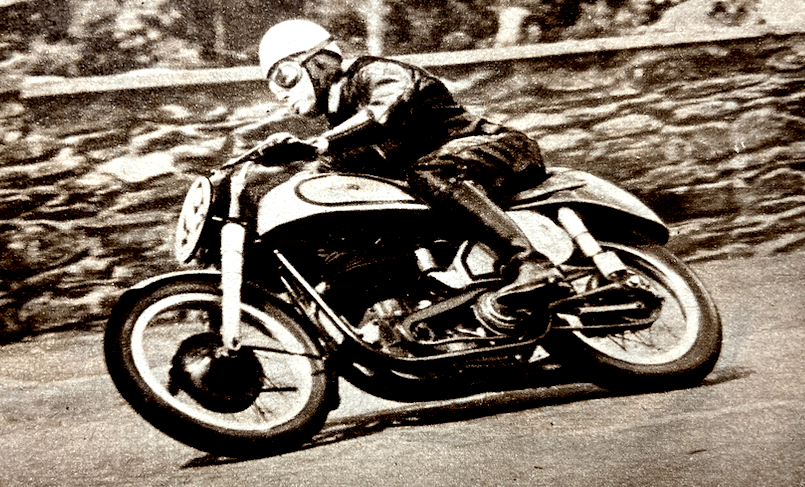

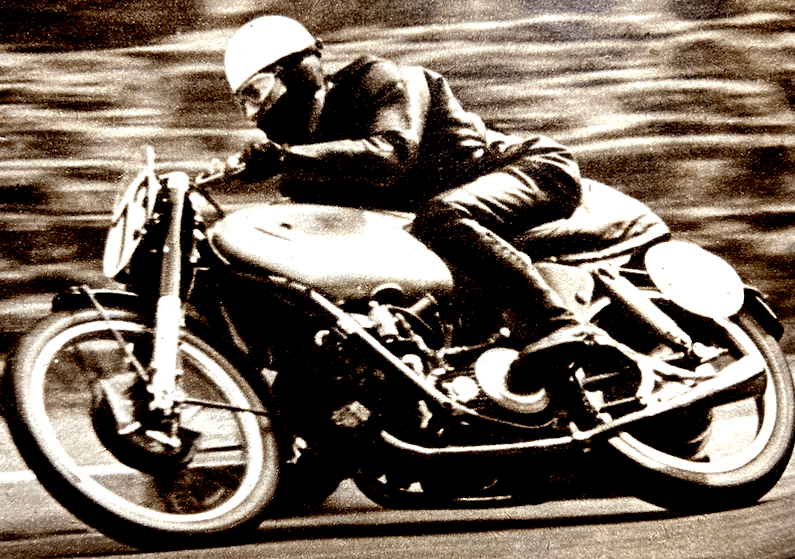

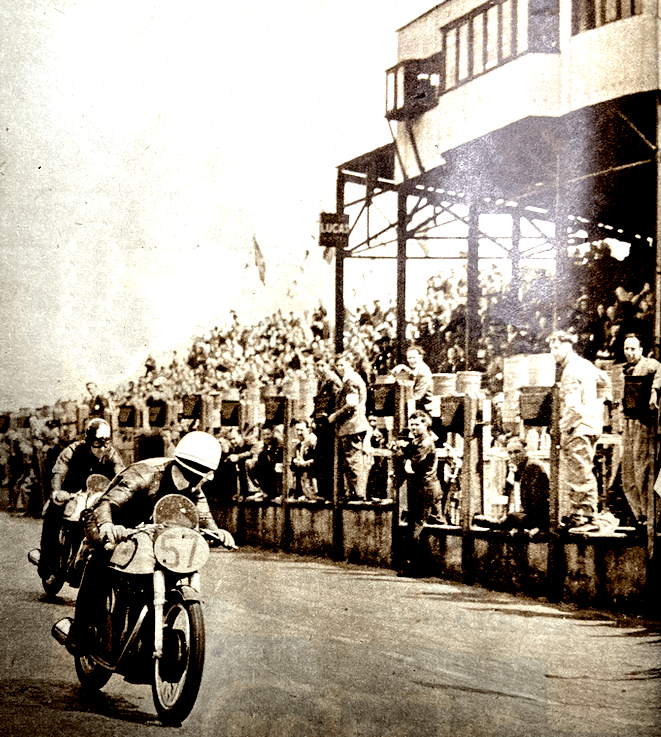

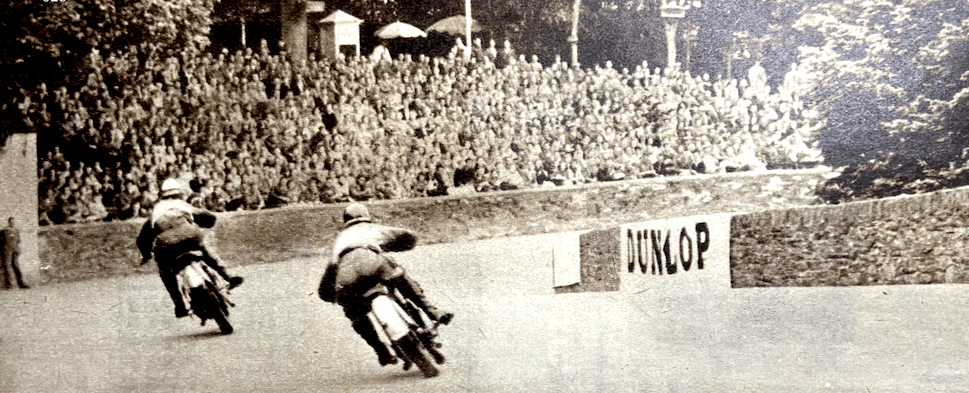

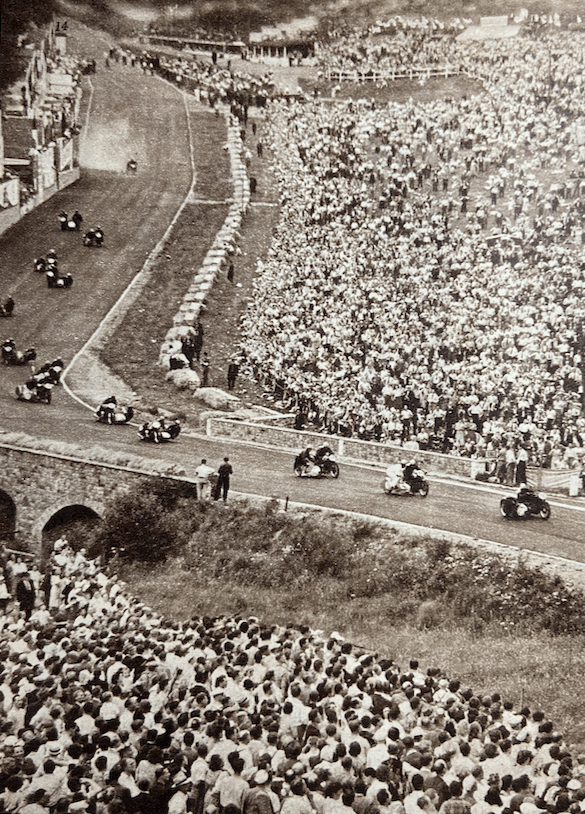

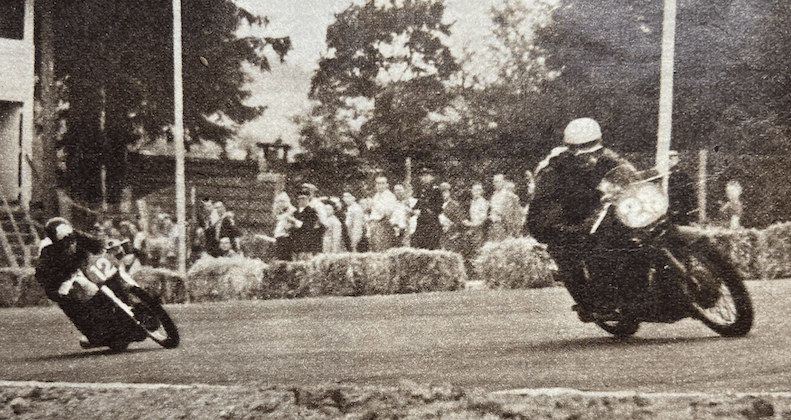

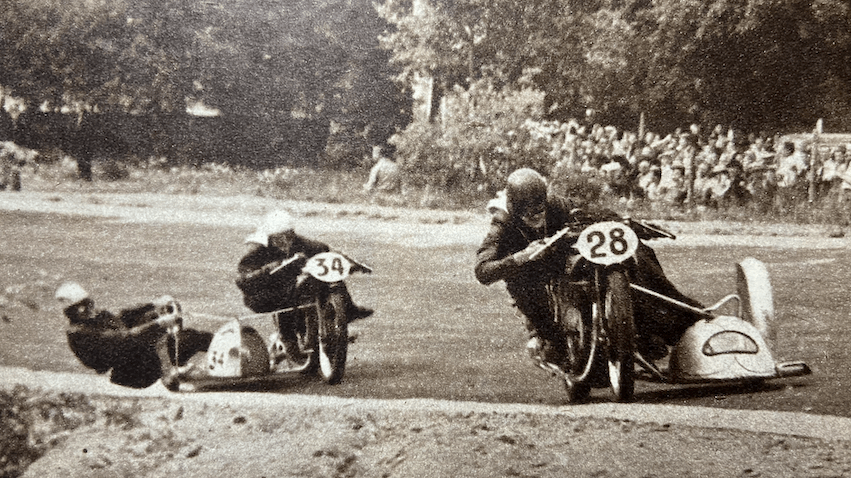

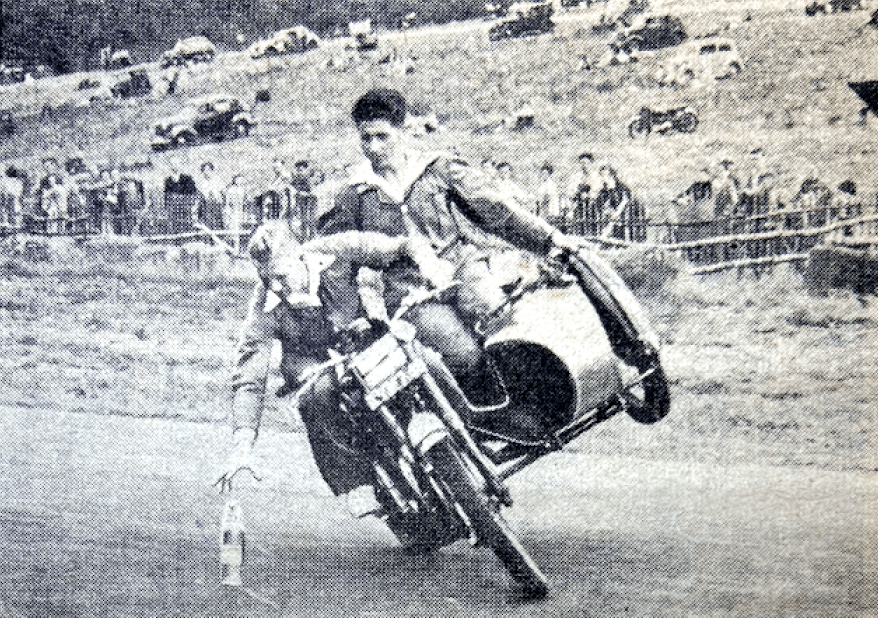

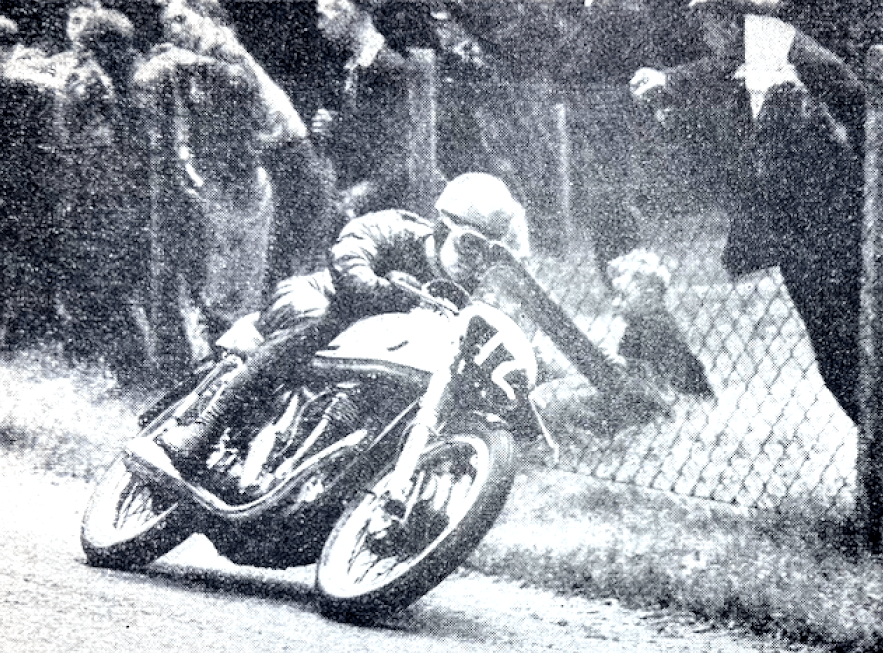

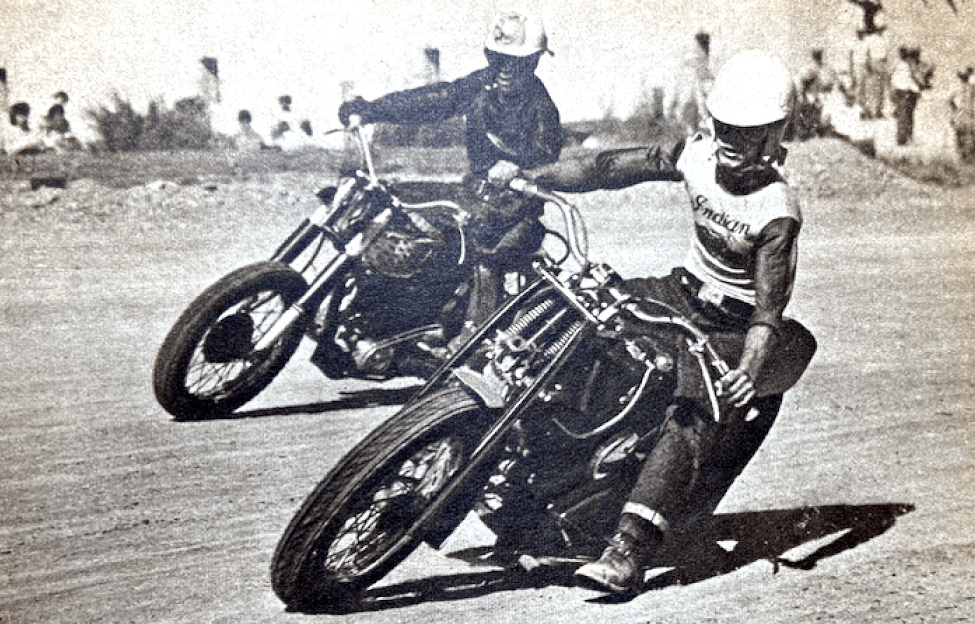

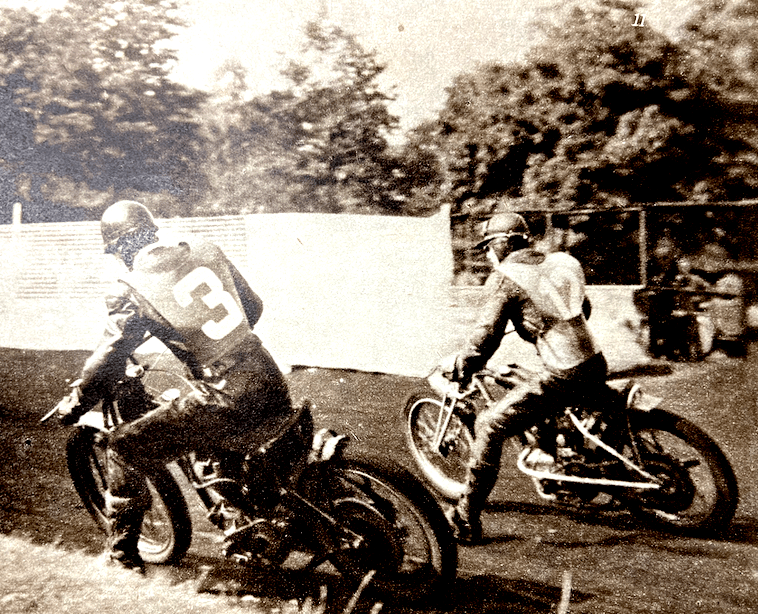

I can only guess that more than one Aussie road race was known as the Australian TT, because within a few weeks the Blue’ Un reported on another Australian TT. And in this case I did a little research (OK I Googled it) and came across some fab pics and the full event programme courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia. What’s more my Aussie mate Murray (editor of the superlative A-Z ‘electronic Tragatsch’ that I refer to on a daily basis) has added colour to some of the race pics. I’ve included a couple pf the pics and a great historical essay from the programme here but recommend checking out the page at http://www.speedwayandroadracehistory.com/bunbury-australian-motorcycle-tt-1950.html

Meanwhile, here’s The Motor Cycle report…