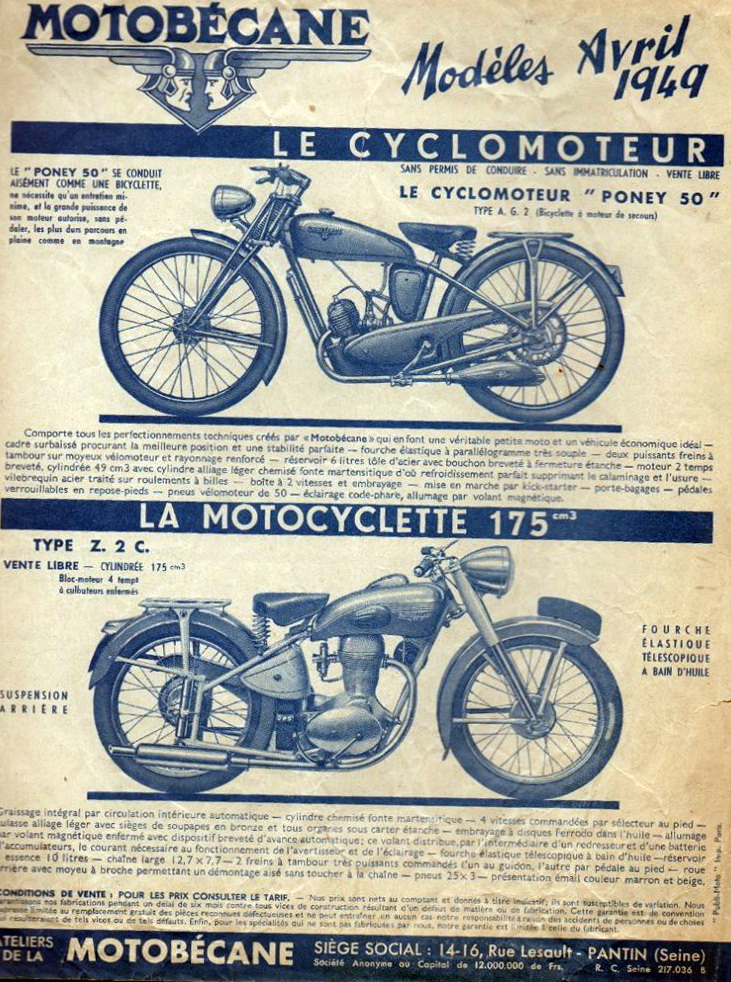

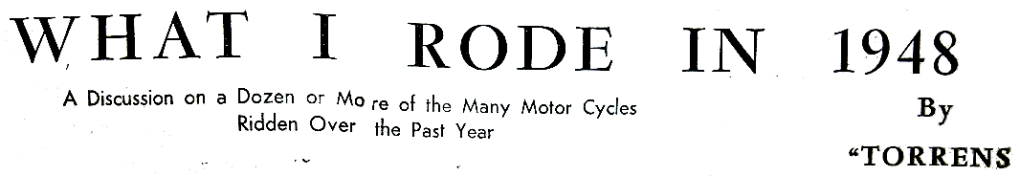

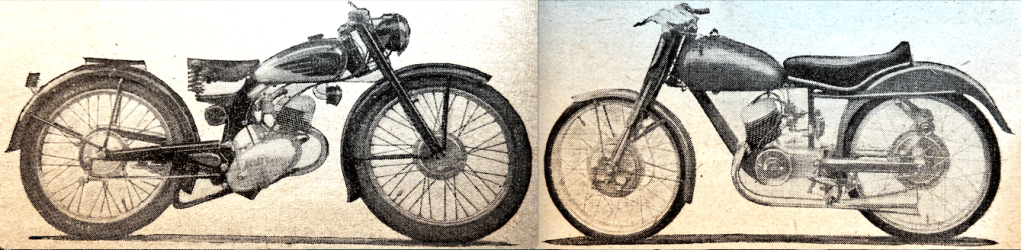

“SOME 40 DIFFERENT MOTOR CYCLES ridden, over 10,000 miles covered—it sounds very peace-time! It also seems that I have been very, very lucky during the year that has drawn to its close. Need it be added that by no means all the miles were in this country? In spite of test machines, there was not a hope of anything like an average of 200 miles a week on the fuel allotted to me at home. What made the odds were visits to the Continent. There has been day after day with its 300 or more miles on the speedometer and then, maybe, a period of weeks when I would be trainborne and chairborne except for the odd flip. However, I am not exactly grumbling! And it has been a not uninteresting year in the matter of machines ridden. They have varied from bicycles with motor attachments and a Corgi with banking sidecar—yes, banking—to racing mounts and 1,000cc twins and fours. Of course, as is so apt to occur, the machine which I class as being as interesting as any is on the secret list. It was built up as an experiment. Perhaps it is the shape of motor cycles to come. I hope so, because I could do with something on those lines myself.

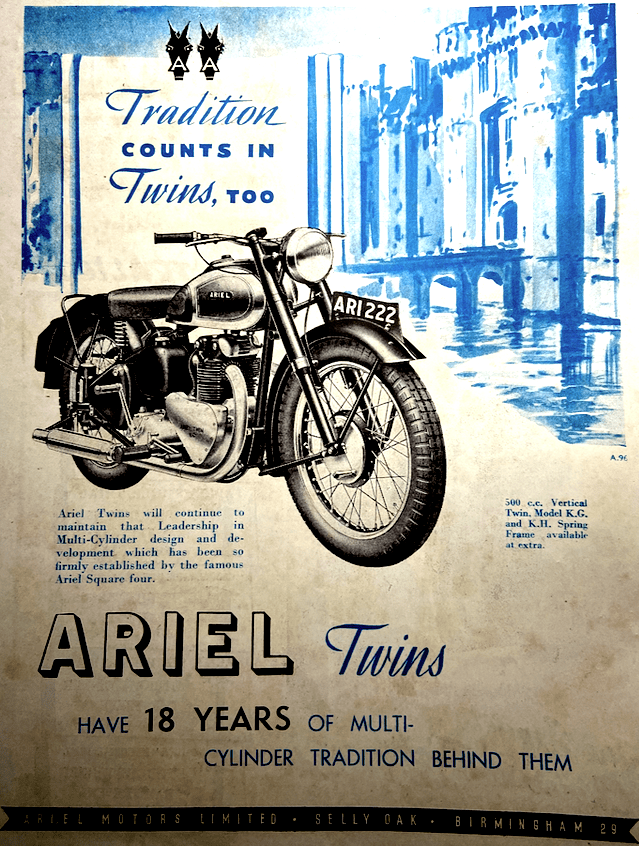

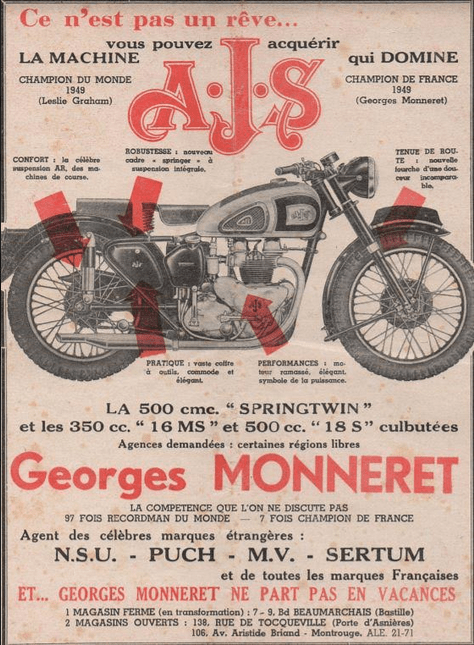

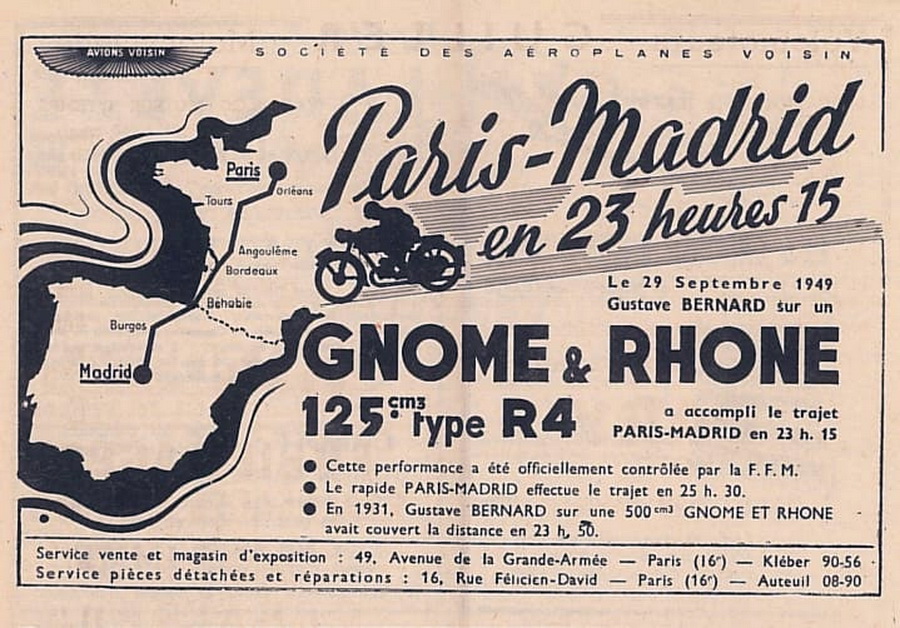

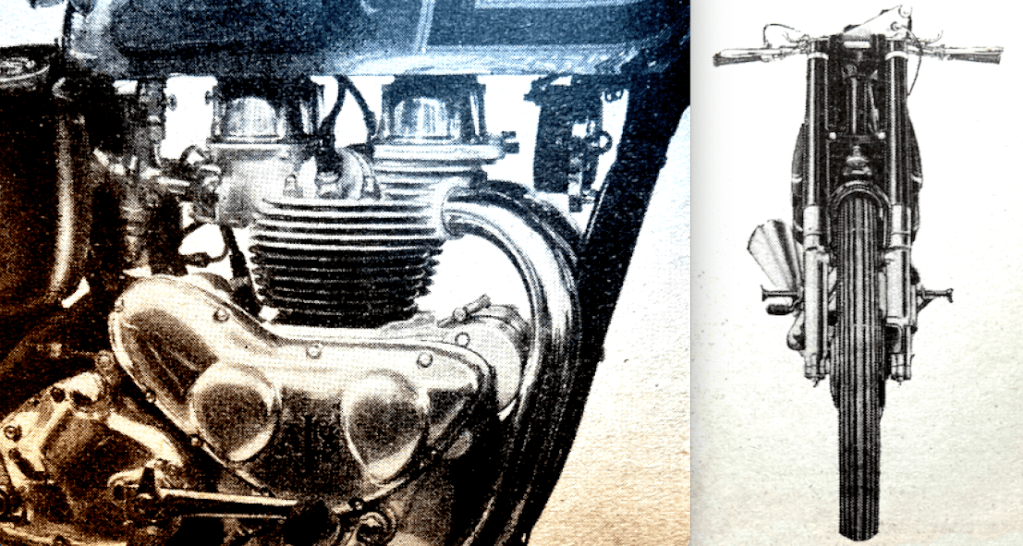

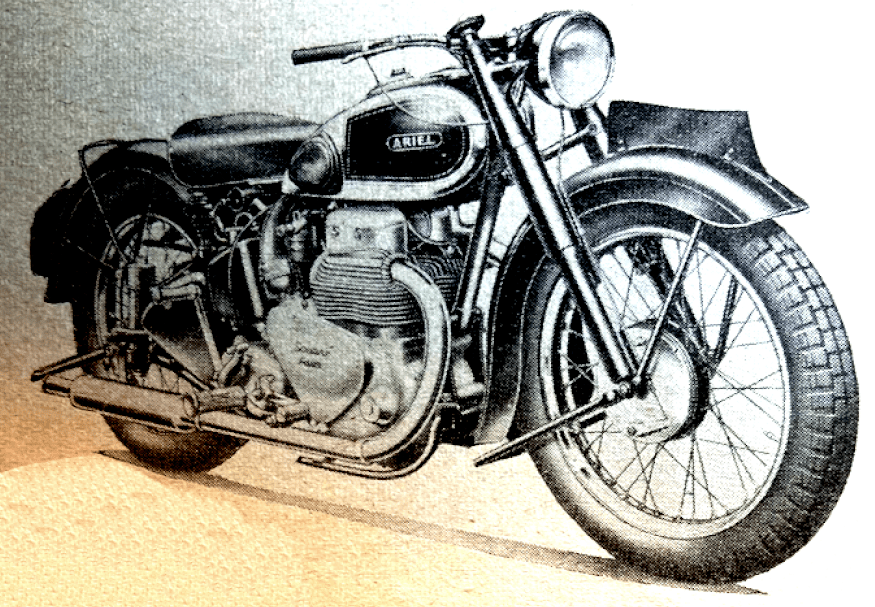

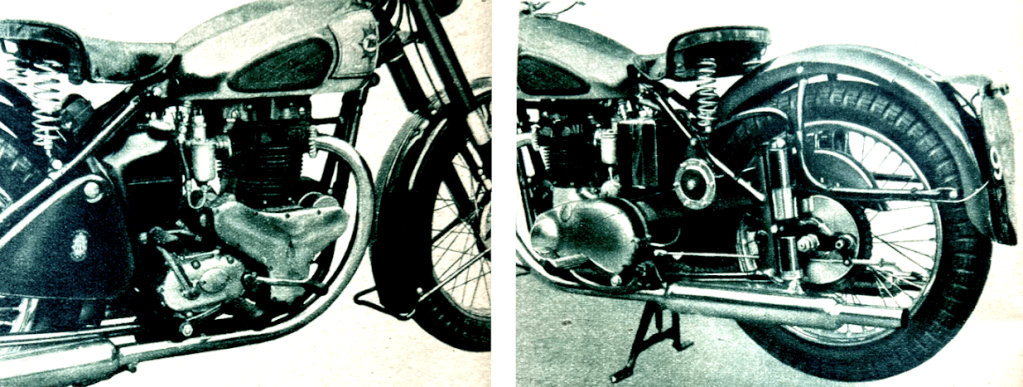

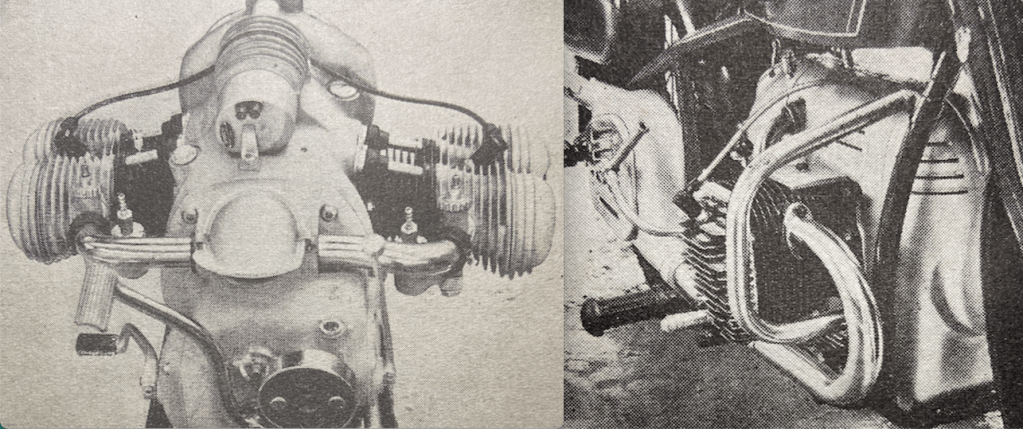

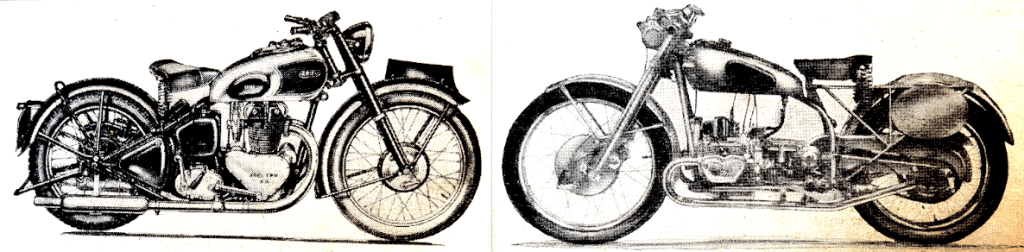

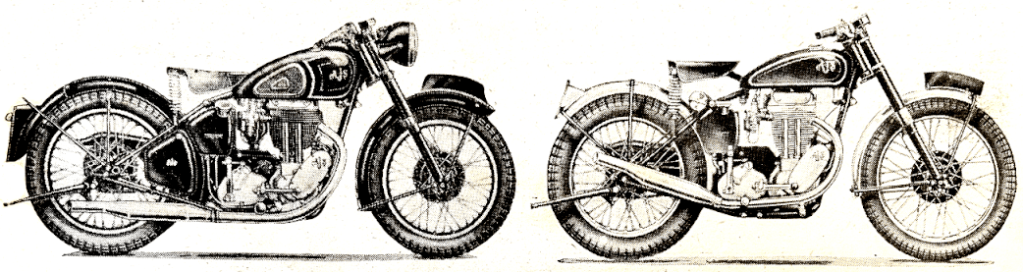

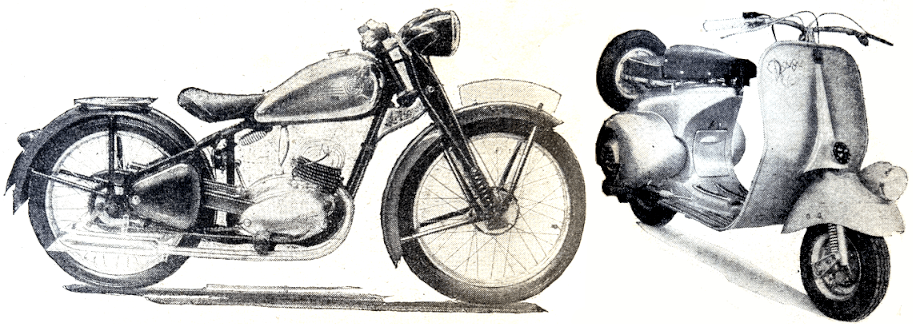

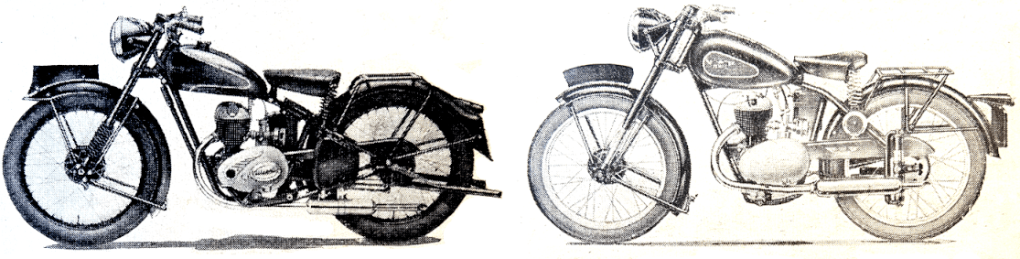

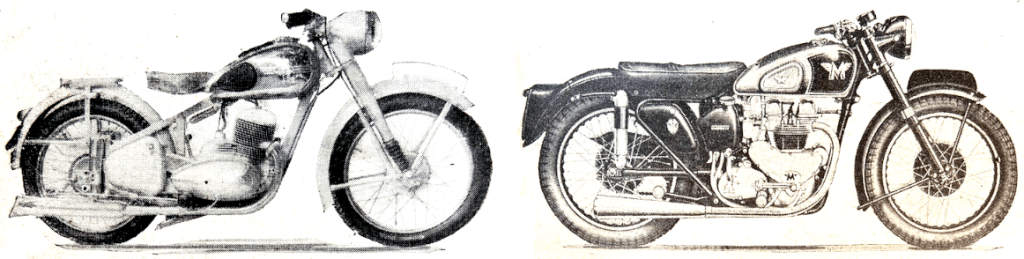

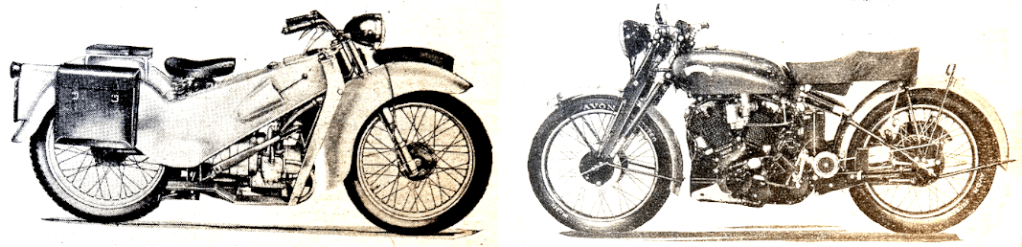

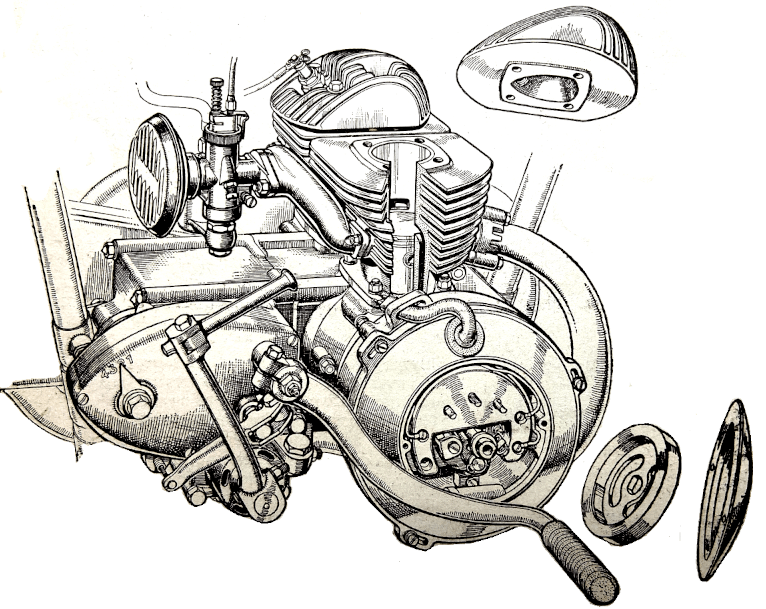

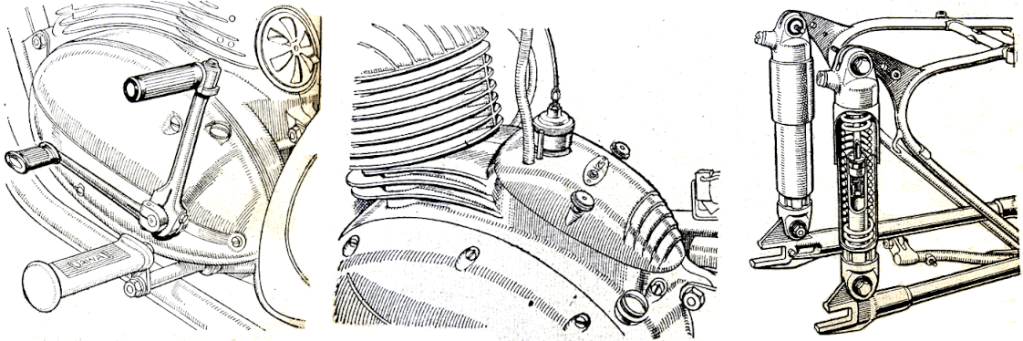

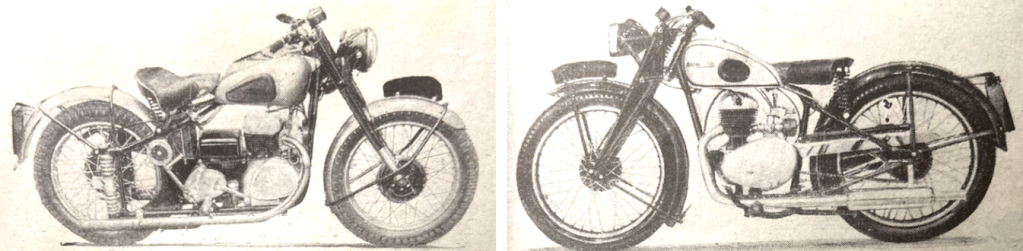

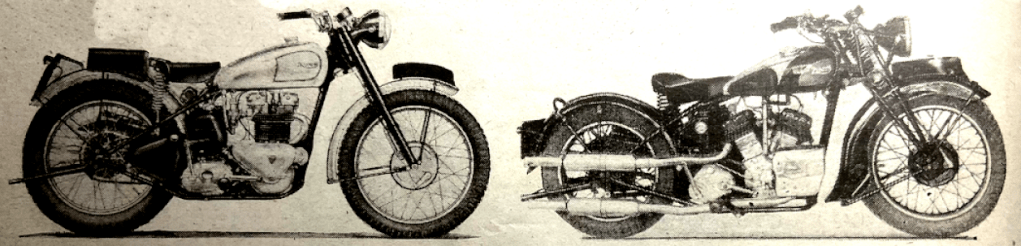

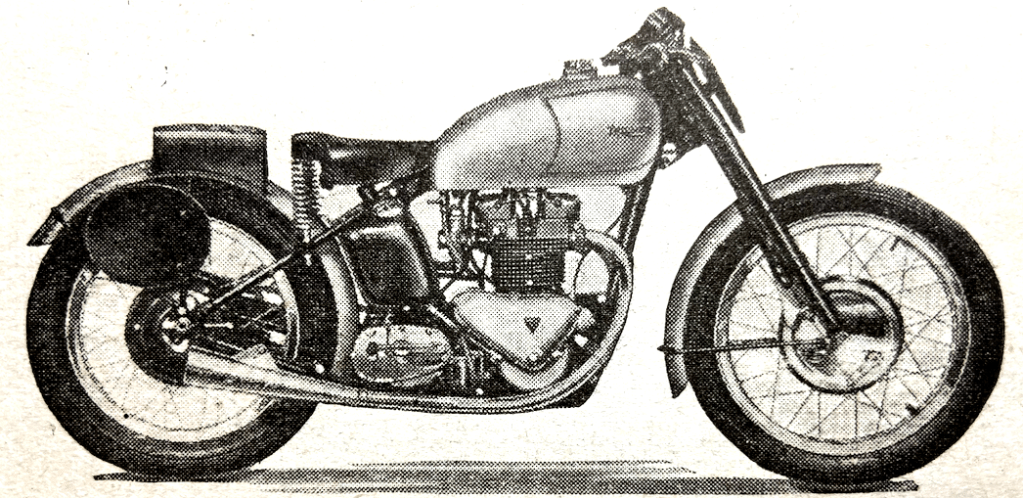

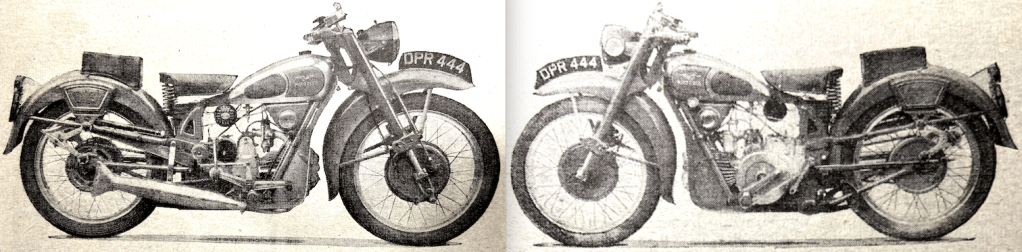

All I can say here is that it has more than one cylinder, it drones, it zooms, it has liquid-cooling. I apologise for being tantalising, but what can I do when it was built secretly as a means of trying out a series of ideas and there are, I understand, no plans for making it even in 1950? But there are at least two mounts no longer secret that were experimental, or rather, were in experimental form, when I originally tried them. These are the new 500cc Matchless and AJS twins. One expects something pretty good from the AMC factory and, if my canters on prototypes give an inkling as to the way the production machines will behave, the new machines will be as lively sports 500s as will be found the world over. One of the prototypes I rode was said to be good for 100mph. Even so, it was far from being intractable in spite of our low-octane value petrol. While new to the market, the twins have been on the go in experimental form for a long time. A glance at my log reveals that I rode one almost exactly two years ago. I like the power unit, with its three-bearing crankshaft, and the rear-wheel suspension lines up with my idea of what tail-end springing should be. A large slice of my mileage, of course, has been covered on my faithful 1,000cc four-cylinder Ariel. It feels a bit cumbrous after a ride on the new light-alloy four which is being marketed for 1949. The half a hundredweight in top-hamper which has been saved by the changes to light-alloy block, light-alloy head casting and coil-ignition unit have made the handling of the new model appreciably better. What are the gains as determined by direct comparison? First, as I have suggested, the machine is altogether more

handleable. There is a conscious effort in laying down the cast-iron model for a fastish bend. With the new mount one swirls round without that cant-her-over thigh work. I cannot say that my own machine has ever been a tiring one to ride. On a number of occasions there have been long days in the saddle and, and even one when it took a big share of a 495-mile day. But your big, heavy motor cycle never seems to tuck quite the expected number of miles into each hour, and the reason, I think, is simply that it is unwieldy on bends and corners. The new Ariel four has lost this failing. Why I, no longer a youngster, ride a machine of this size is because of the power-weight ratio—the way one can cruise along at any speed one likes, even at 80mph, without over-stressing the machine. To be climbing a steepish, main-road hill at 60mph and shoot forward at a flick of the right wrist is joy indeed. And I like the swish that is akin to silence, the genteel performance and the way, if one be in the mood, one can stay in top gear almost all day long. Perhaps, most of all, I revel in the reliability of my machine. It is the most reliable motor cycle I have ever owned. Having made the last remark, it would not be unexpected if the day this article goes to press there were a spot of roadside bother. But even if there were, I could not grumble. My machine has not the enthralling flexibility of the new light-alloy Ariel, which has an automatic advance-and-retard. The latter, I found, has a top-gear speed of a bare 8mph, which one uses automatically since there is no transmission snatch. Therefore the fact that the machine had a better gear change than any Ariel I have ridden over the

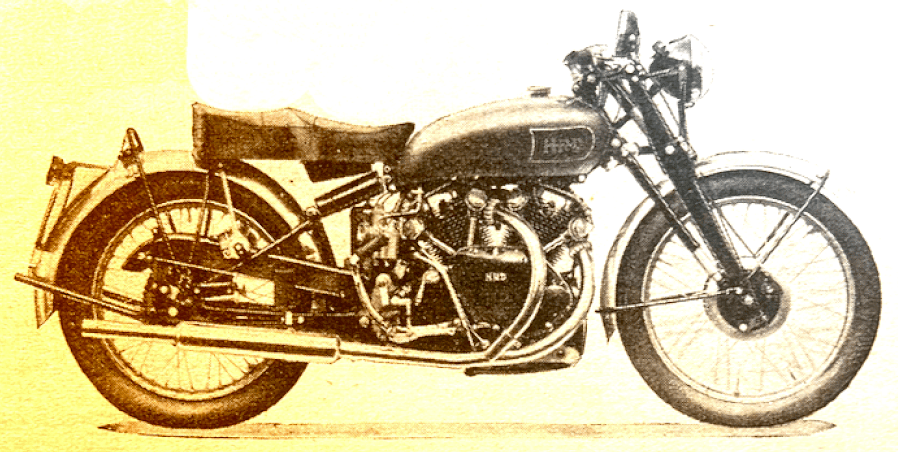

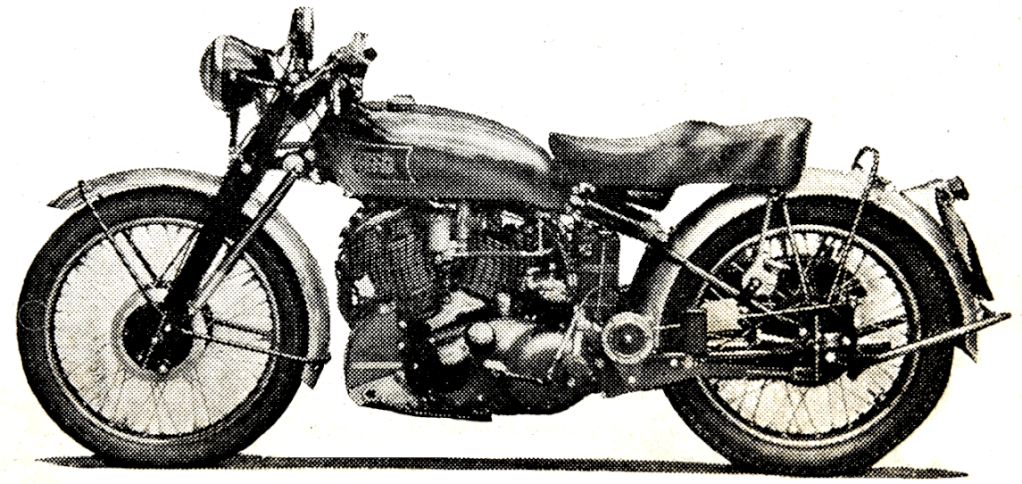

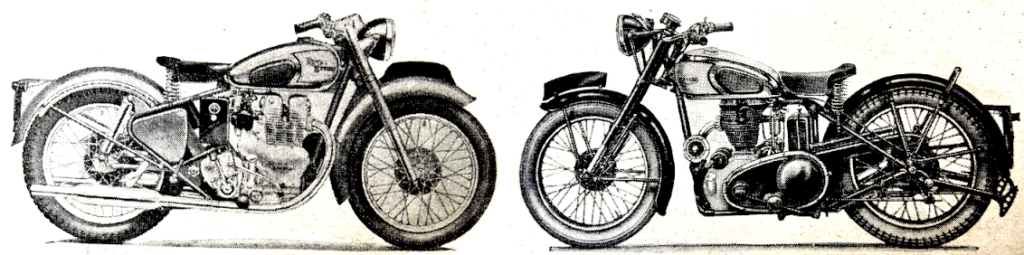

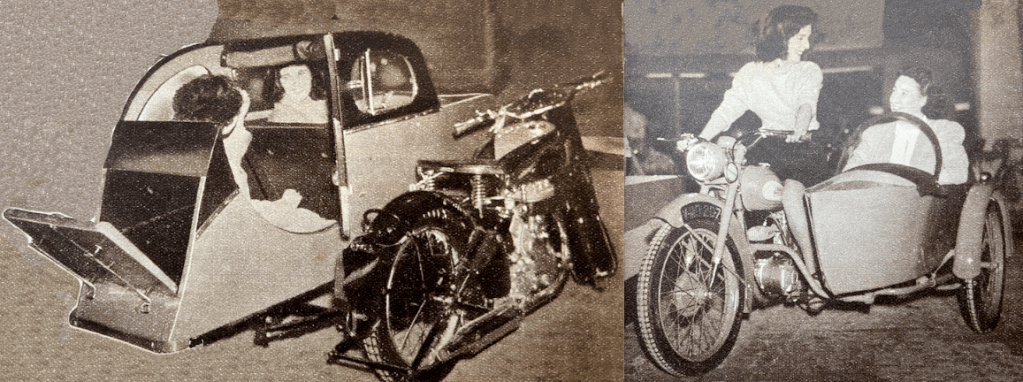

past 20 years carries less weight than it might have done! The engine of the light-alloy job I rode was not so smooth as my own, nor was the fuel consumption as good. I gather that immediately the machine was back at the works the engine was stripped to determine why I grumbled at lack of smoothness, and it was found that the static balance was slightly out. Occasionally, enthusiasts remark that, while I mention my machine, I never give performance data. Do you take out your machine—your own machine—and see what you can do in a tyre-smoking, tarmac-burning, standing start to 60mph? I don’t, and also I have not the slightest interest in whether my present machine will do 90, 95 or 100mph. I know it will keep its so-called ‘Police test’ speedometer at 80 plus on the Holyhead road and have a useful amount in hand; I know it will accelerate up to just on 80mph on my pet main-road climb; I know it betters 60mpg even at averages of 45, so what do I care? Lately the machine has, as you may know, taken unto itself a sidecar which is slipped on and off. I am still using the highest set of solo gears…What will happen if I attempt to restart on a really steep hill I do not know, but for the work so far the plot has worked. In any case, changing from solo to sidecar is a task of minutes, while swopping engine sprockets, particularly with the Ariel chain case arrangement, means more like half a day. The sidecar steering is heavy, there being the standard Ariel telescopic fork and, therefore, solo fork trail. One day, all makers of machines suitable for passenger work will have to do some serious thinking about the needs of sidecarrists; there must be sidecar trail for those who fit sidecars. The brakes, even with the machine solo, require too-frequent adjustment and that undamped rear-springing, while all right on our good British roads, can result, in a bouncing-ball effect if a series of hefty waves in the road is encountered. Let us pass on to another thousand, the Vincent-HRD. This is a very different type of machine from the four-cylinder job we have been discussing; it has been described as ‘rorty and naughty’. There is a great deal to be said for a 1,000cc V-twin pulling a gear ratio of 3½ to 1. There is an easy, loping gait, and the way this machine gathers itself together under one when

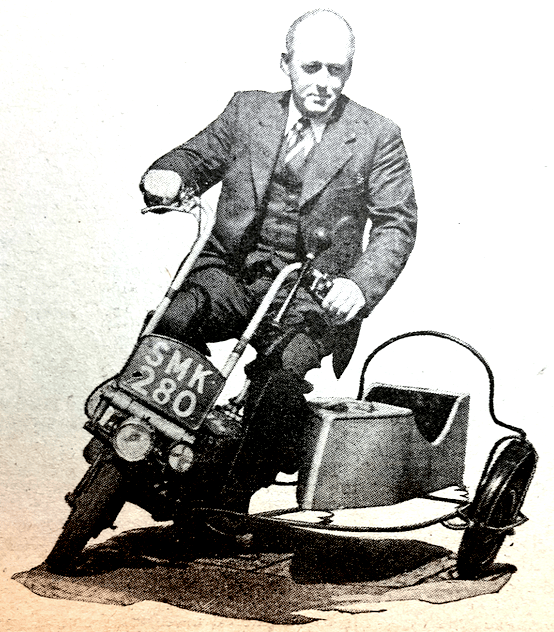

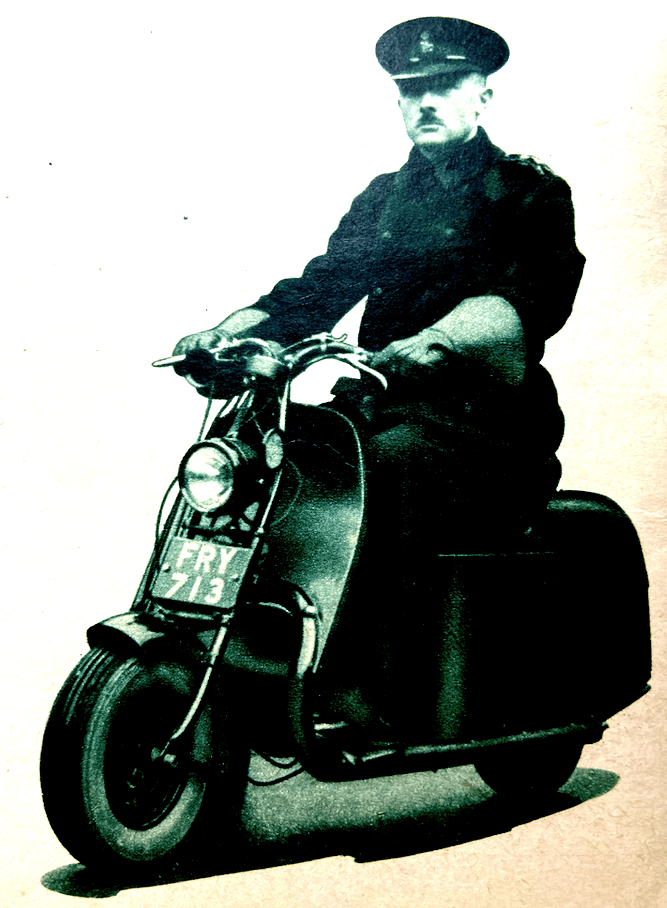

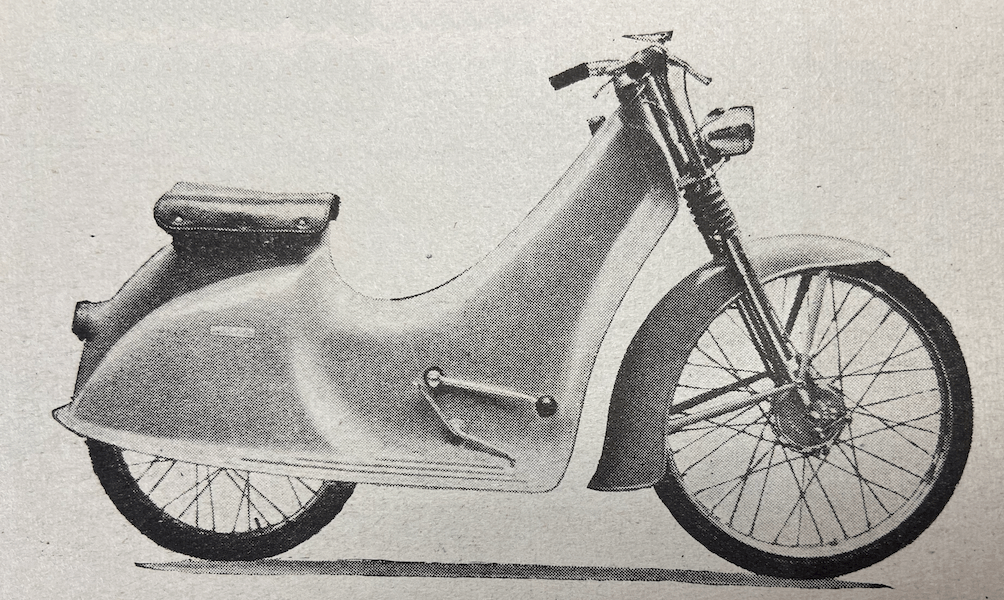

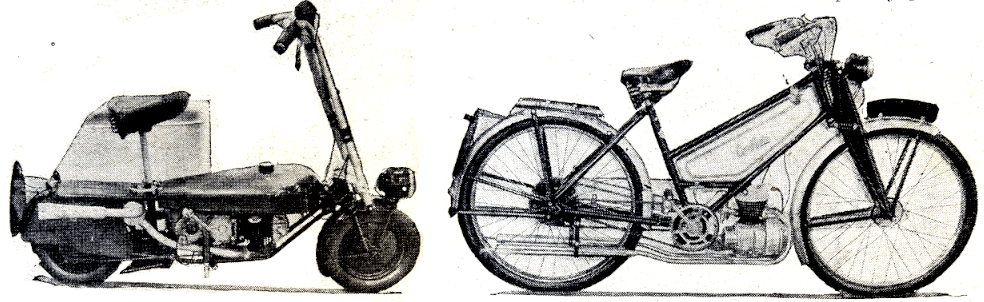

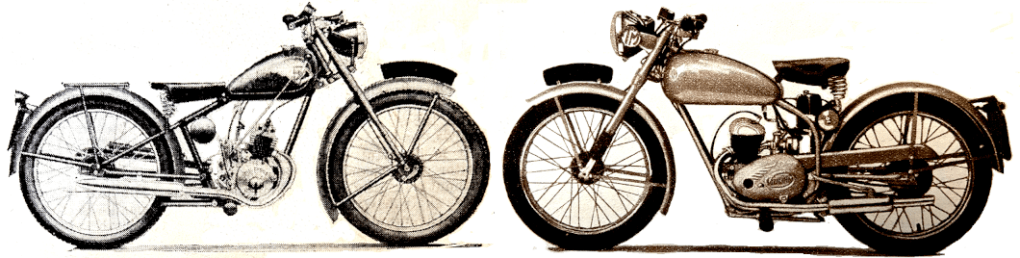

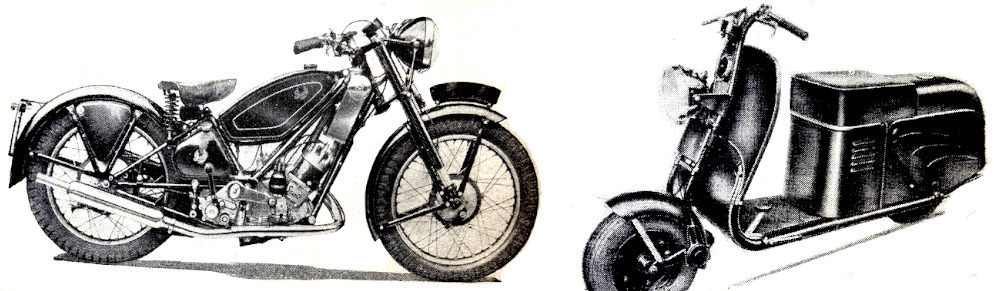

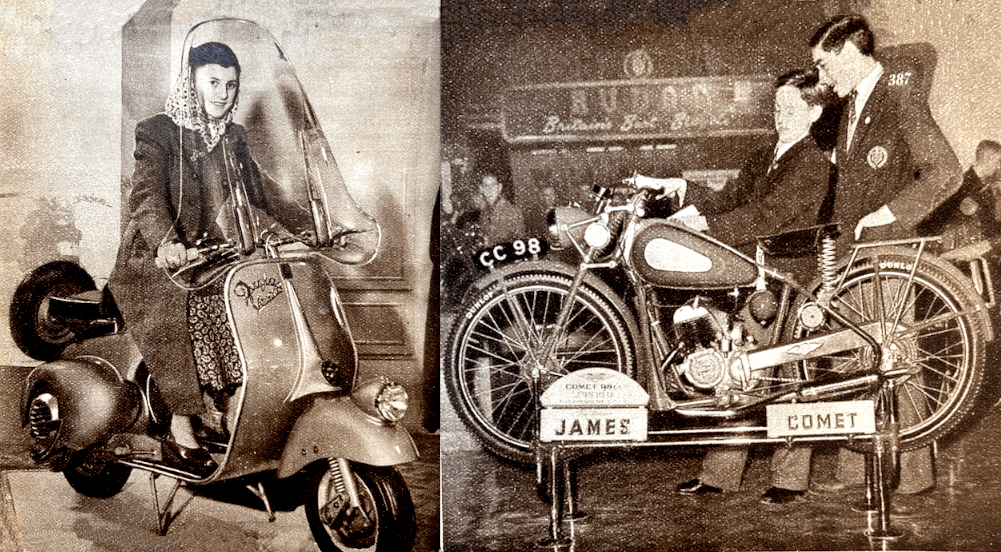

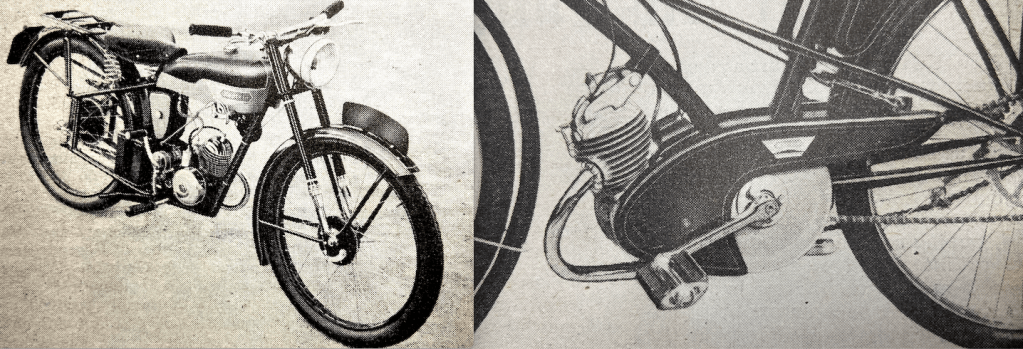

one takes a fistful of grip is great. Here, if ever there was one, is a man’s motor cycle, and it is a machine which is essentially masculine in both outline and behaviour. I was delighted with the flexibility of the machine—the way one trickles along in top gear in 30mph limits—and, of course, in the outstandingly good power output and braking. And the machine is so much more handleable on bends and corners and in the rough than the old Series ‘A’ Rapide. But what about the riding position on which Stevenage prided itself so much, and so rightly, in the past? With the now necessarily high-up foot-rests I, who am no more than 5ft 10½in, find I am hunched on the machine, legs crooked at the knees, and a passenger instead of feeling master. On one occasion, a result of my being thrown about, and not part and parcel of the model, was that on a series of humps I started the steering going from one lock to the other—on a Vincent-HRD, the most rock-like steering machine in the world! There are too many machines to-day which have been designed, it seems, for small men My criticism that the springing could result in the bonny-bouncing-baby act on hummocky going appears to have been met for 1949. Maybe before many weeks have passed I shall have an opportunity of finding out for myself. What I will say here and now is that if you want a thrilling, zestful mount that is unique in performance of the variety that should have a capital ‘P’, the Rapide provides the answer—and a very good answer, too. Now let us shoot to the opposite end of the engine-capacity scale—to Mosquitos, Fleas and that canine, the Corgi. Lately, as you know, the autocycle, which was to have given little more than cycling without effort, has grown up and, except for its single gear and the retention of pedals, has become in general very much a motor cycle. So it seems that it will be a case of starting at the bottom again, and the bottom this time is likely to be an engine unit that you buy in a carton about the size of that for a small wireless set and clamp on your pedal-cycle in 20 or 30

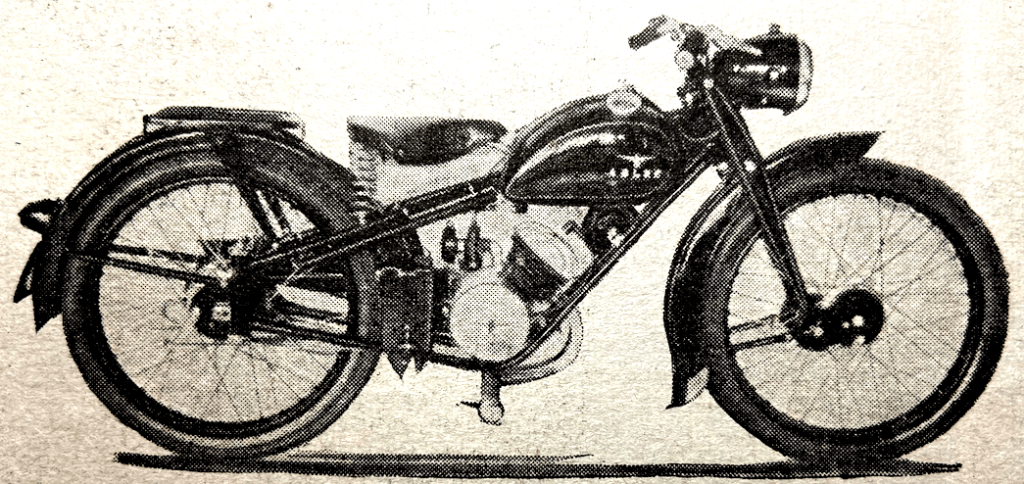

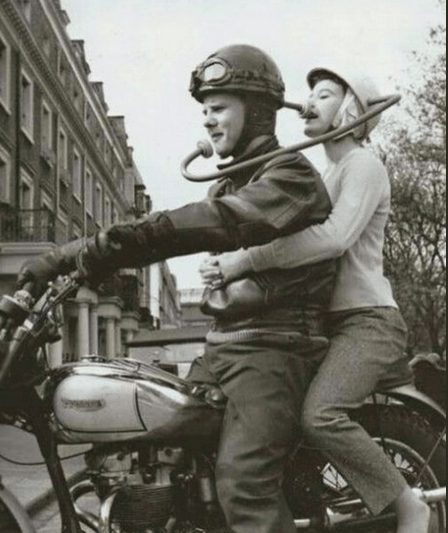

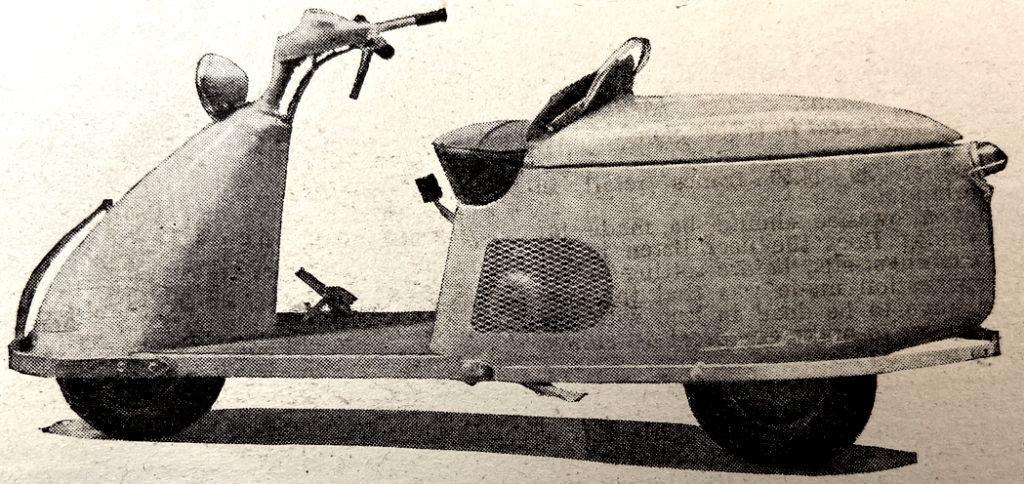

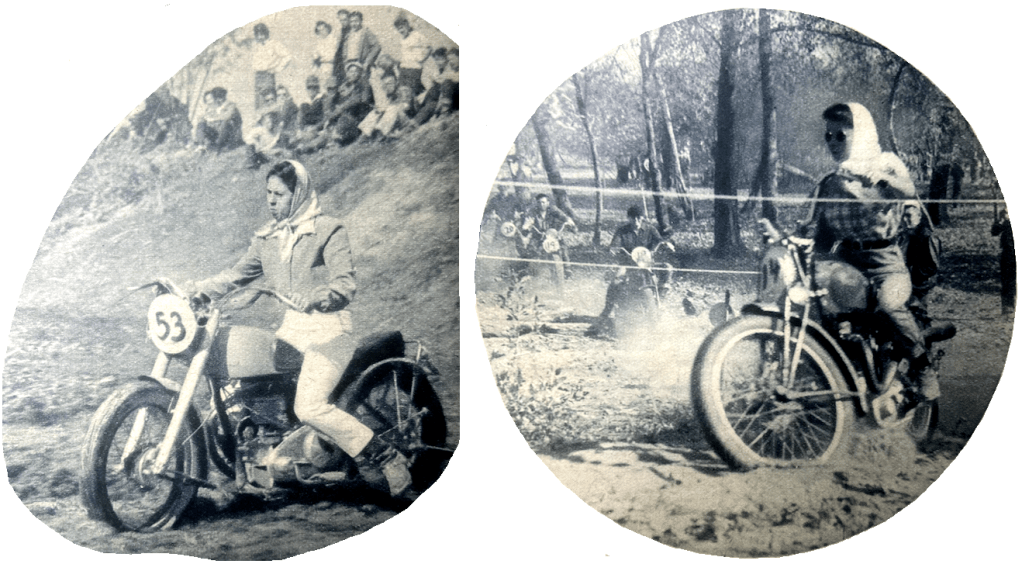

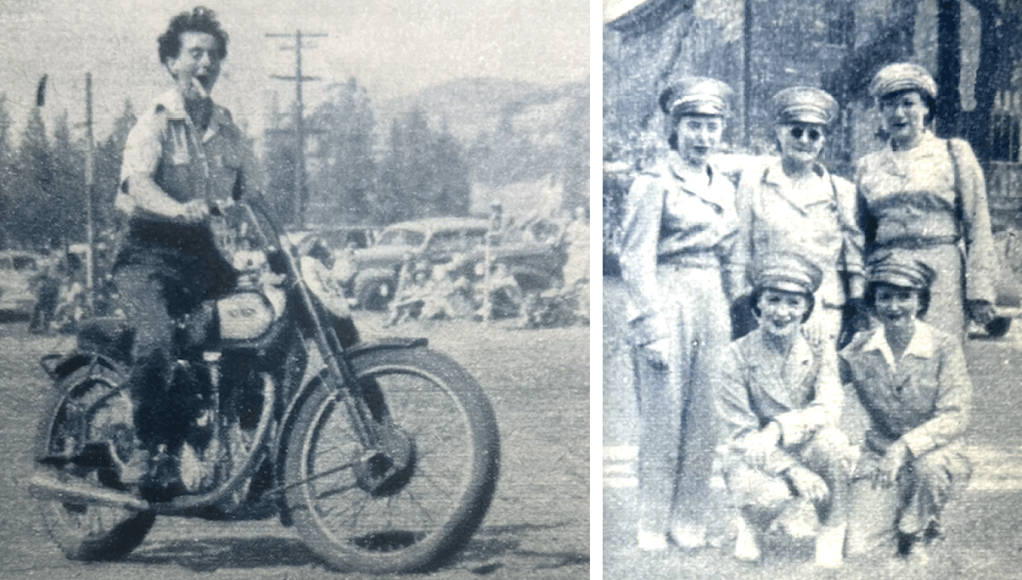

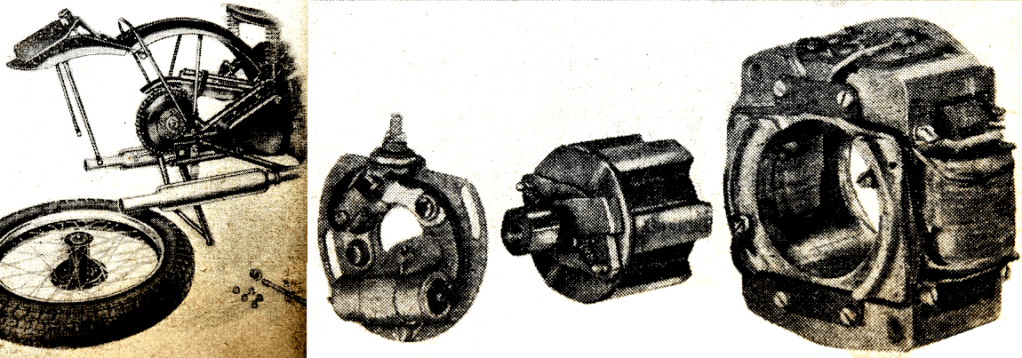

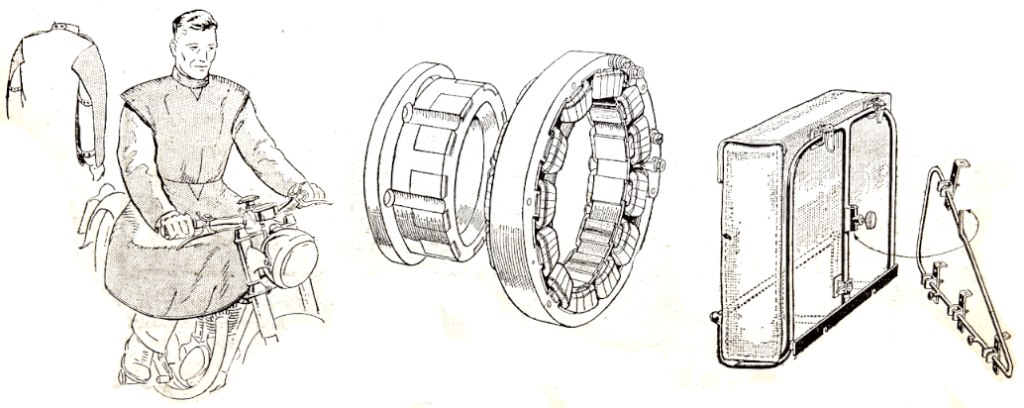

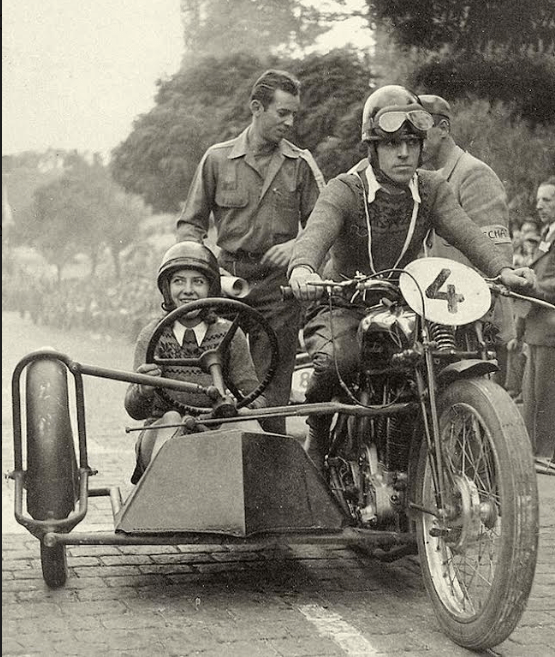

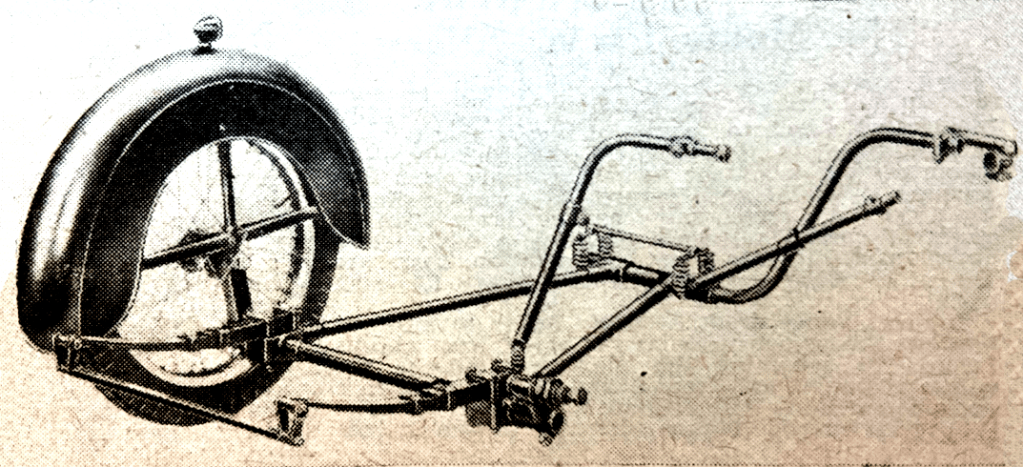

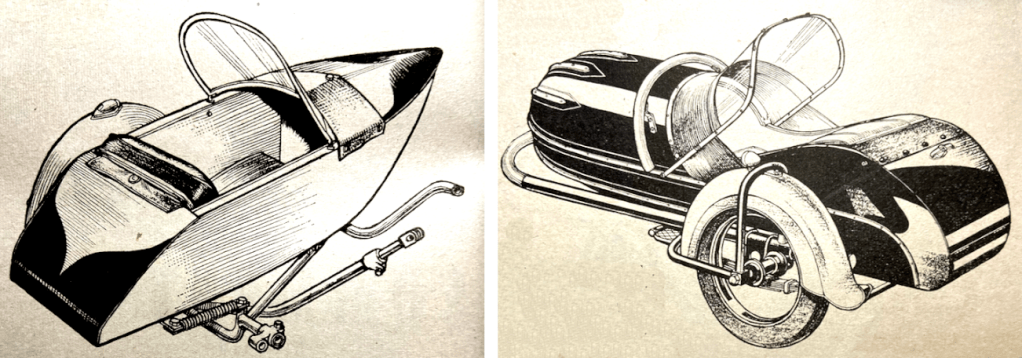

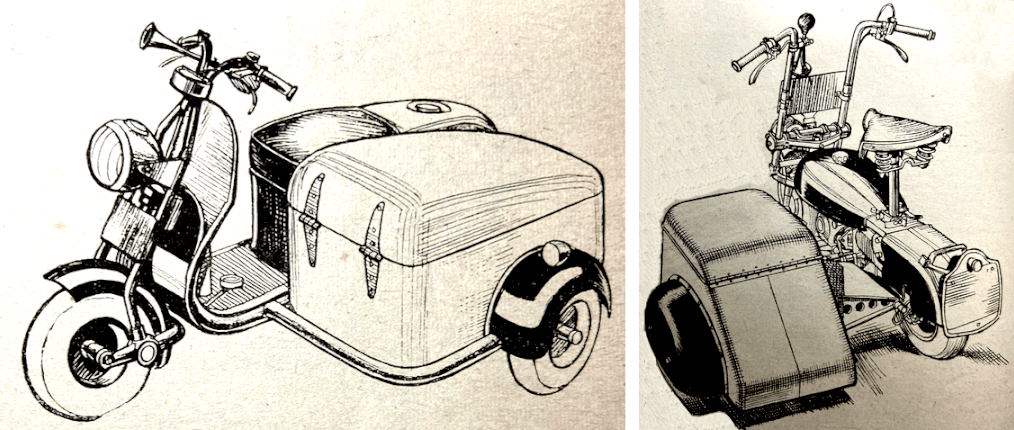

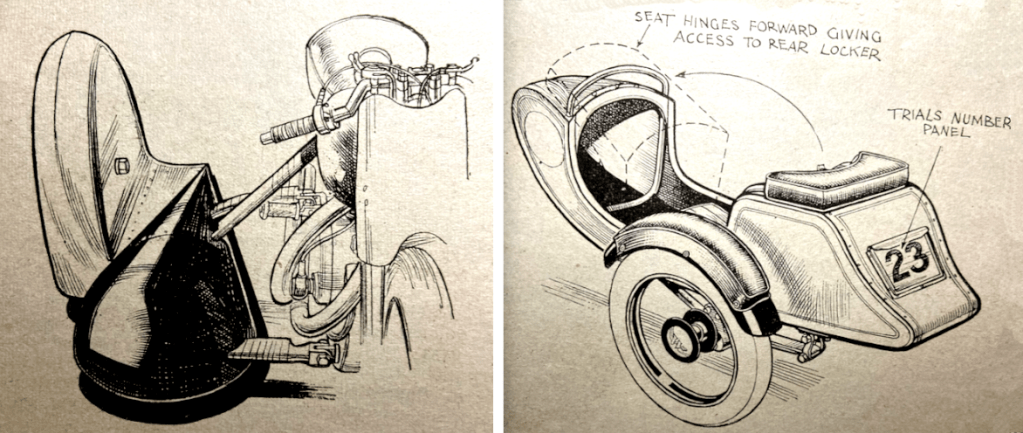

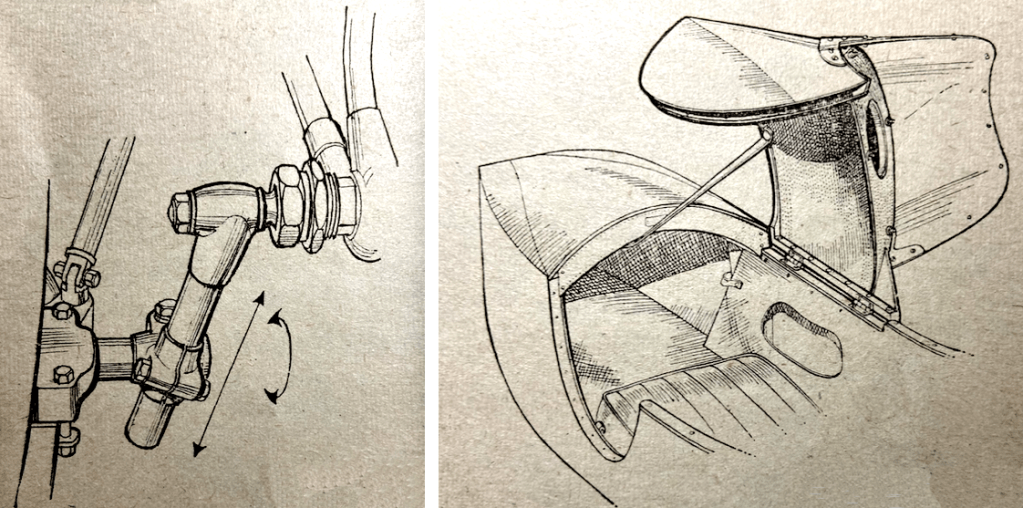

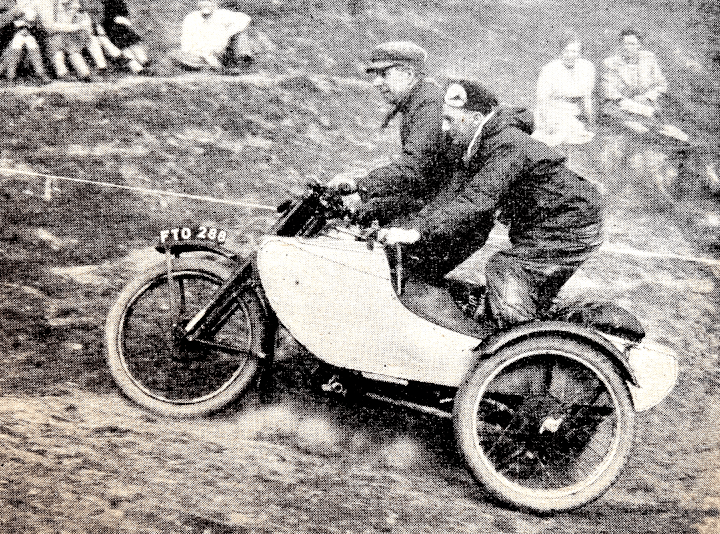

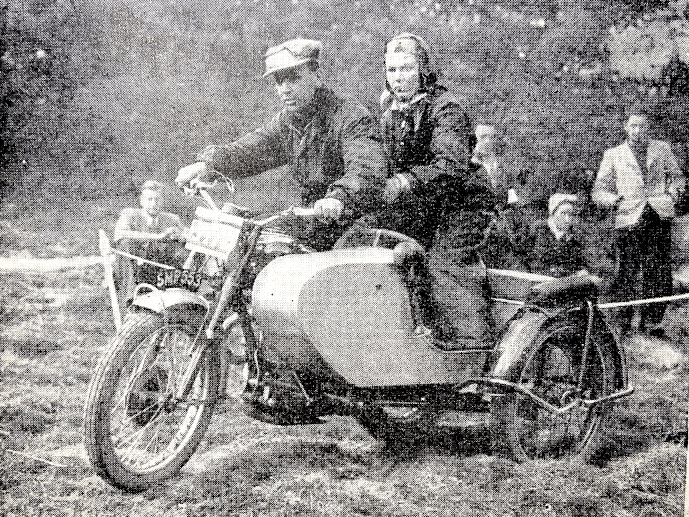

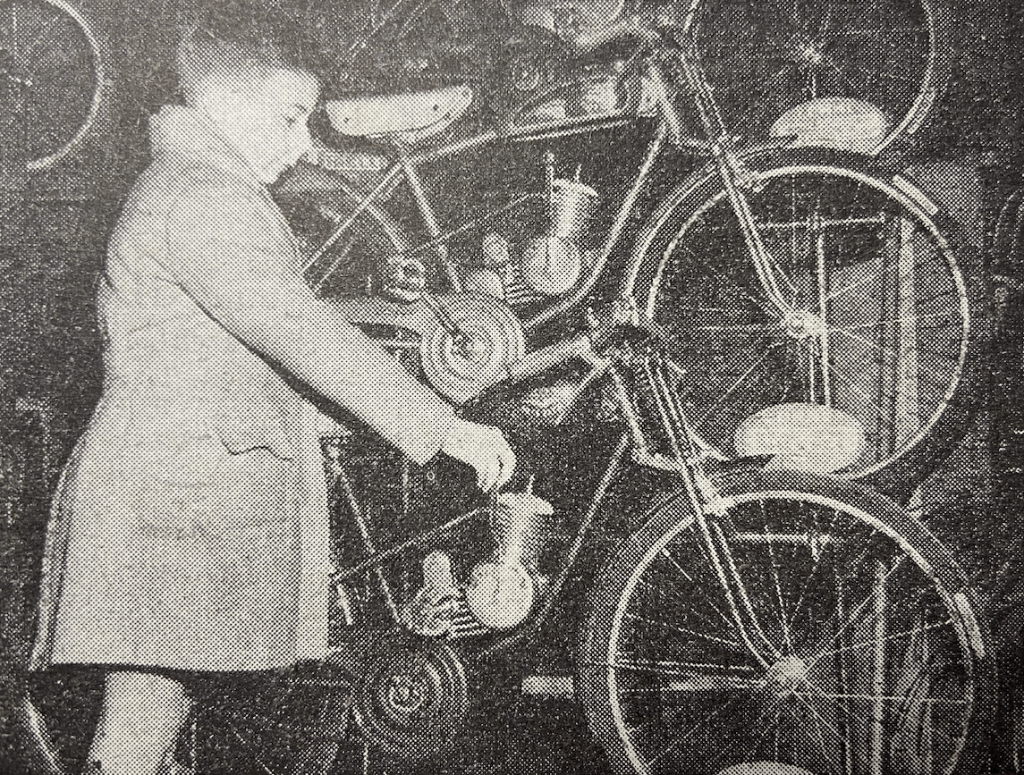

minutes. The idea is as old as the century and some manufacturers are appalled at its resurrection, holding that it is utterly wrong to apply engine power to a bicycle, which was never designed for the purpose and may already be very second-hand. I should be equally appalled were it not that it is possible—has been proved so—to provide satisfactory units which develop no more power than a couple of ordinarily lusty legs and which, owing to smooth torque, are calculated in various directions to stress the bicycle less, and not more, than those legs. The mass market lies in the cartoned unit that will fit on any bicycle; because then alone will the all-in cost be low. Besides, no one wants to have to throw away his or her pedal-cycle and have, in effect, to buy another. Where trouble has arisen in the past is that satisfactory units have not been available and that some who have set about making engines to provide cycling without effort have failed to produce engines that merely give ordinary bicycle speeds. My experience with the 38cc Mosquito, made at the rate of 600 or more a week by the famous Italian Garelli company, is that to-day there is the answer. With such a unit one ambles along at 10 to 15mph, and ordinary main-road grades are surmounted with light pedal assistance to the engine—the pedalling gear ratio remains that of the bicycle so the pedalling really does help the power unit. Mind you, the Mosquito is in every way a real job, and most beautifully made. If there is a criticism it is that the engine turns over at high speeds. Dispensing with a reduction gear would save money, and this has been done with some of the other units developed on the Continent. Considerable interest is being displayed in this country in these motor attachments, which can make a most valuable stepping-stone to a motor cycle. A fear is that some people may rush into production with partially tried units and kill the whole idea, just as happened with scooters immediately after the 1914-18 war. In one of the photographs you see BH Kimberley, erstwhile competition rider, with a prototype of a banking sidecar he designed for a Corgi. Originally he made up the little outfit chiefly for amusement, but so successful did the idea prove that you may be hearing a lot about such chassis. What intrigued me when first I handled the machine was that here was a sidecar outfit that was controlled exactly like a solo; there was no sidecar-driving technique to be learnt and no tipping up. At least, this was the impression I gained, but in the back of my mind was the thought that perhaps I was driving the machine like a normal sidecar outfit, although doing so subconsciously. To satisfy myself I borrowed the use of a friend’s tennis court and threw a Corgi party. The tiny sidecar outfit

was entrusted to my boy of, then, barely eight years of age, to his friends of both sexes, to the parents of the said friends, to a grannie, and to a number of other folk, none of whom had sidecar experience. In every case they were immediately at home with the outfit. Good enough! What I am looking forward to doing now is trying (a) the finalised version of the Corgi banking outfit and (b) a sidecar of similar design on a motor cycle of large capacity. A very different type of machine is the so-called ‘Boy’s Racer’ AJS, the racing 350cc ohc 7R. I happened to be at the AMC factory as the pre-TT batch was coming through and snaffled one that was just back from its road test. Fancy, in these days, being able to pick up a pukka racing 350 with a silencer end to its megaphone and waffle through the streets of Woolwich! Of course, these machines are not being turned out for road work and won’t be—how road-racing they are has been proved in many of the races, here and abroad, that have been held over the six or eight months since the machines reached the market. The remarkable thing about this production racer is its success right from the start. There have been short flips on other racing machines—Nortons, a Velocette and Guzzis. I marvel at these modern racing jobs with all their top-end power, but somehow still hanker for the days when I could, and often did, pick up a TT winner at Euston Station in London, fill up with 50/50 petrol-benzole, and slip off on a 400-mile day to Exmoor—this with the fitting of silencers, number plates, licence, and a smaller main jet as the only alterations from TT trim. However, when your 250 Guzzi twin is as fast as, if not faster than, Charlie Dodson’s Senior TT-winning Sunbeams and Alec Bennett’s 1927 Senior Norton, I suppose one ought not to grumble. What I liked about those old days was that your TT machines were but

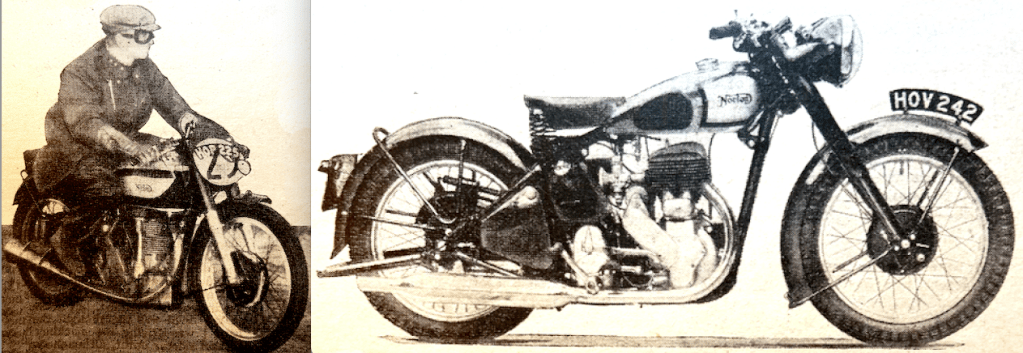

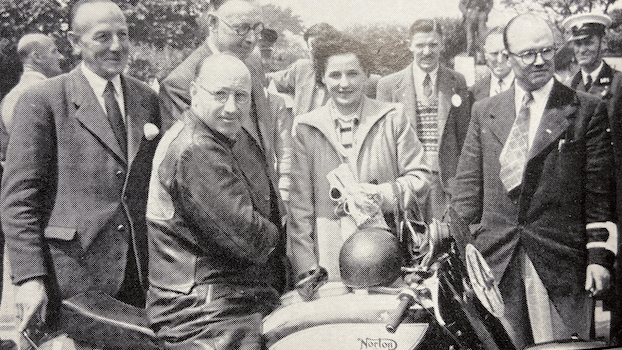

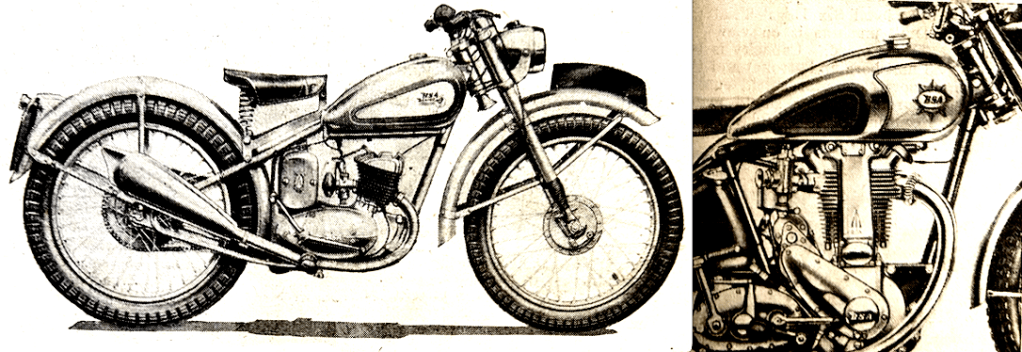

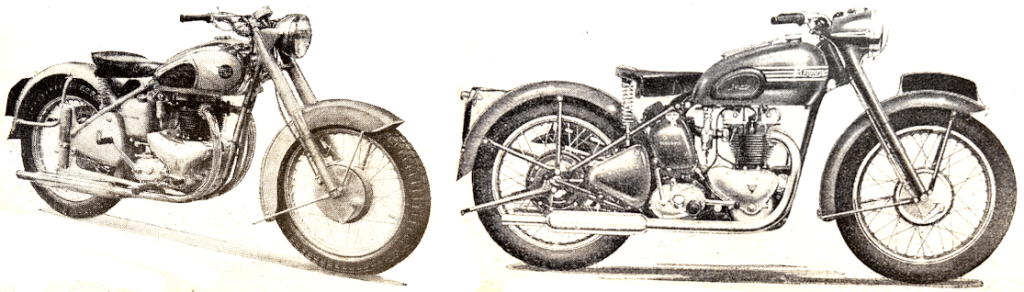

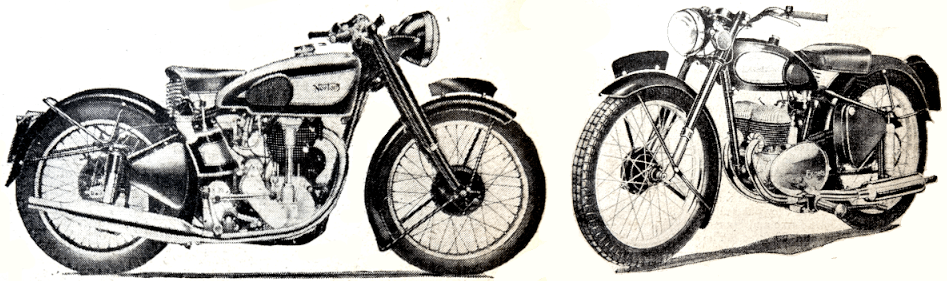

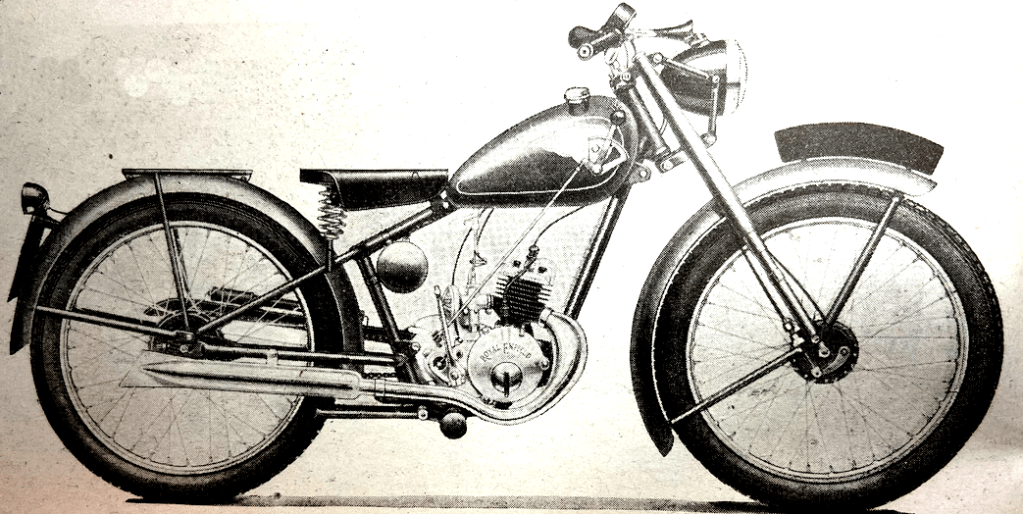

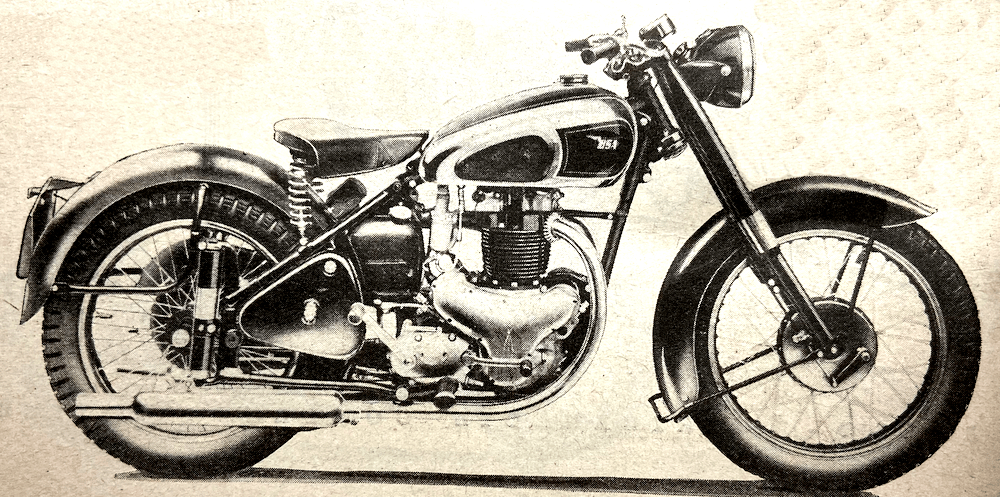

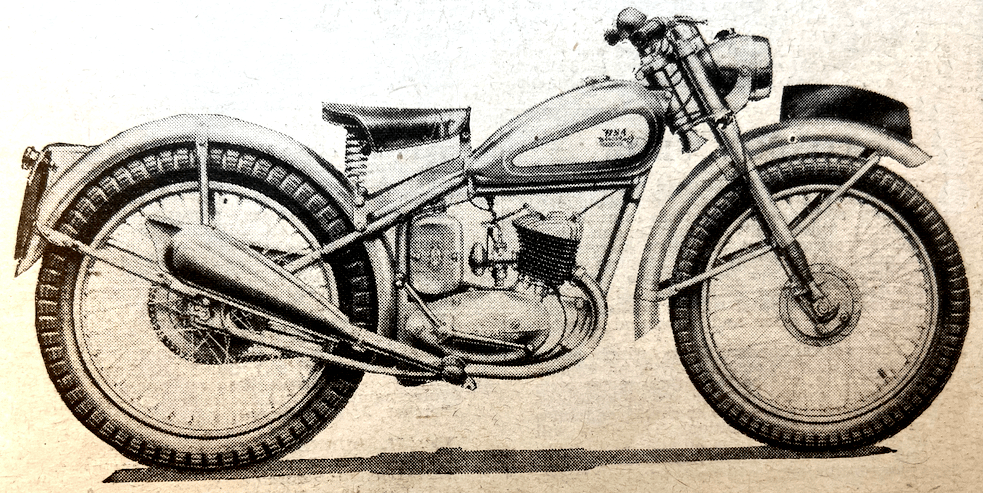

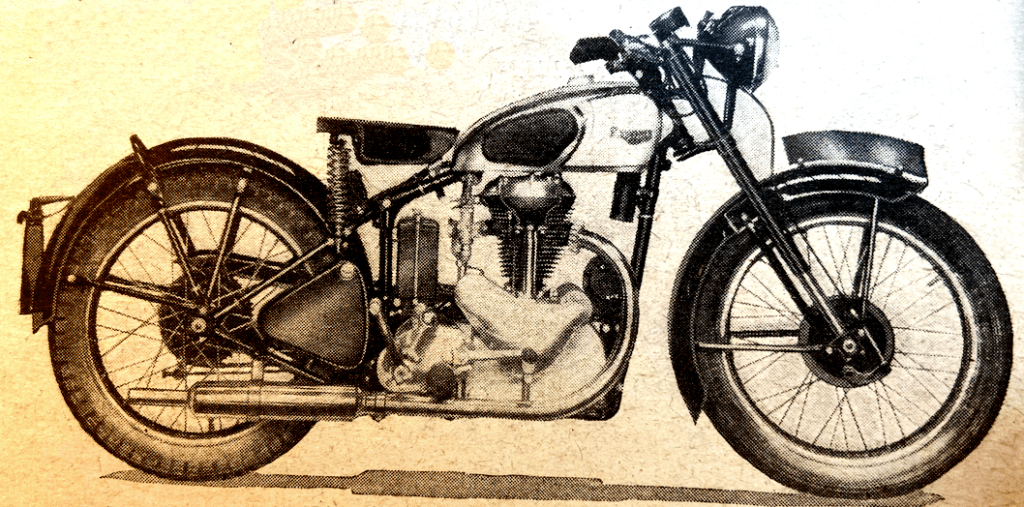

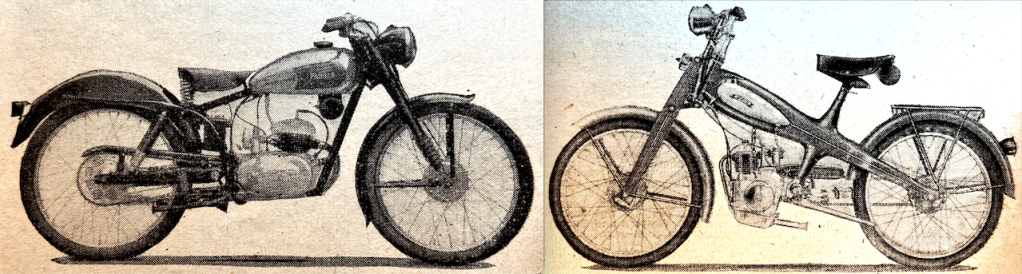

specially tuned and furbished editions of the standard, super-sports roadsters. At Sunbeams, for example, early in the New Year, the racing department would ask the works for a series of specials for the TT, and Mr FT Jones, then Sunbeamland’s works manager, would hand over a number of standard Model 80s and 90s, being keen to know just what the standard production machines would do and could be made to do! A pity the TT has become no specialised…Before this long article is brought to an end there are two other machines on which I want to touch. The first is the Continental-looking 125cc BSA two-stroke ‘Bantam’. Even at a maintained 30mph the machine we had for Road Test did 160mpg and it had a top speed of 47mpg. This is a remarkable motor cycle which promises to become extremely. popular. Like everything else, it is not, of course, perfect. The two crabs I had against the model I tried were that it was much noisier than it should have been, and the transmission was harsh at low speeds. Both failings can be overcome, though transmission roughness is not always amenable to ‘treatment’, by which I mean that one machine which was launched on the market last year was endowed with a whole series of modified transmission shock-absorbers before the works were satisfied (and I was still not unduly impressed!). Lastly, there is a machine which gave me as much pleasure as anything I rode in 1948, namely, the new 490cc side-valve 16H Norton. Perhaps my pleasure was tinged with the roseate hue which can result when one believes something is possible and then personal experience proves it to be so. I, with tens of thousands of miles on side-valve Sunbeams—the 492cc Longstroke and the 499cc Light Solo—and the old side-valve Norton, have known that the side-valve has been a Cinderella and, instead of improving over the years, has become worse. I have not loved detachable cylinder heads, with the resultant break in the heat path, nor the shrouding caused by valve enclosure. The new 16H showed me that a really super, yet modern-type side-valve, can be and is being manufactured—a sweet, supple engine which gives one effortless touring, is economical, and gives one comfortable 40mph averages on the open road. I say ‘effortless’, but there was one direction in which the machine failed, and that was that the balance was not up to modern-day standards. This, I gather, has been attended to and, if the results are what they can be, you have in the latest 16H a most delightful motor cycle. And the new 596cc model ‘Big Four’ is, I am told, equally outstanding. Perhaps I shall know more before this New Year is much older.”

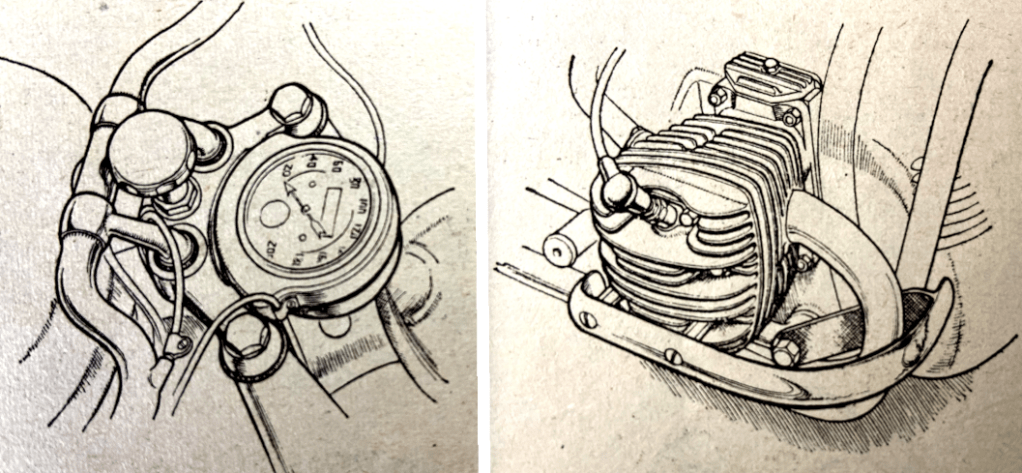

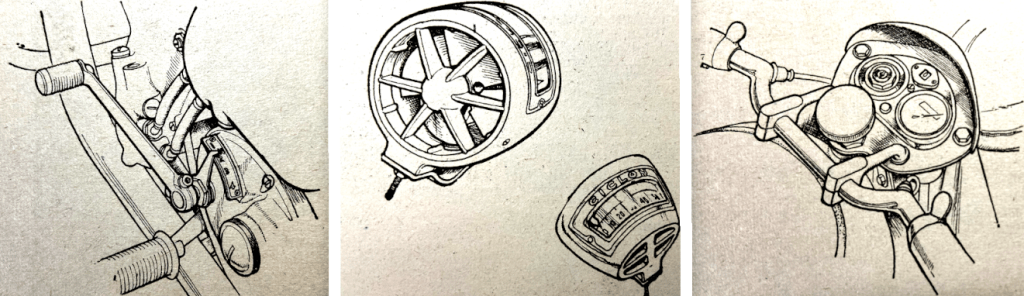

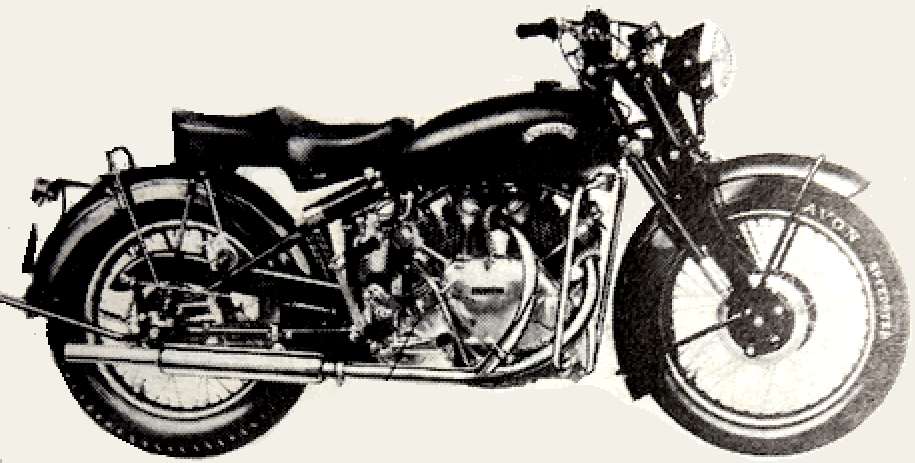

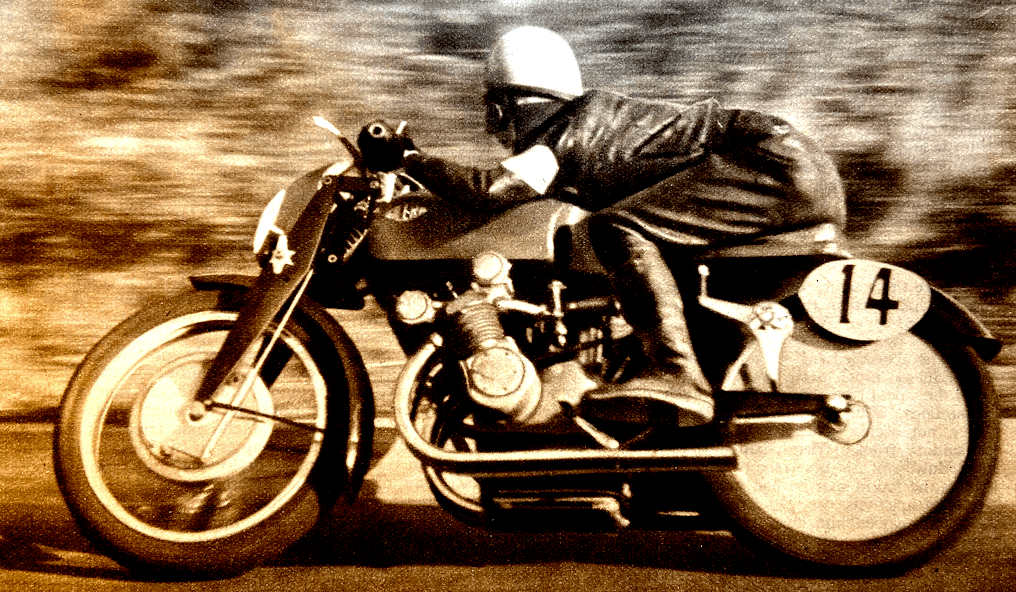

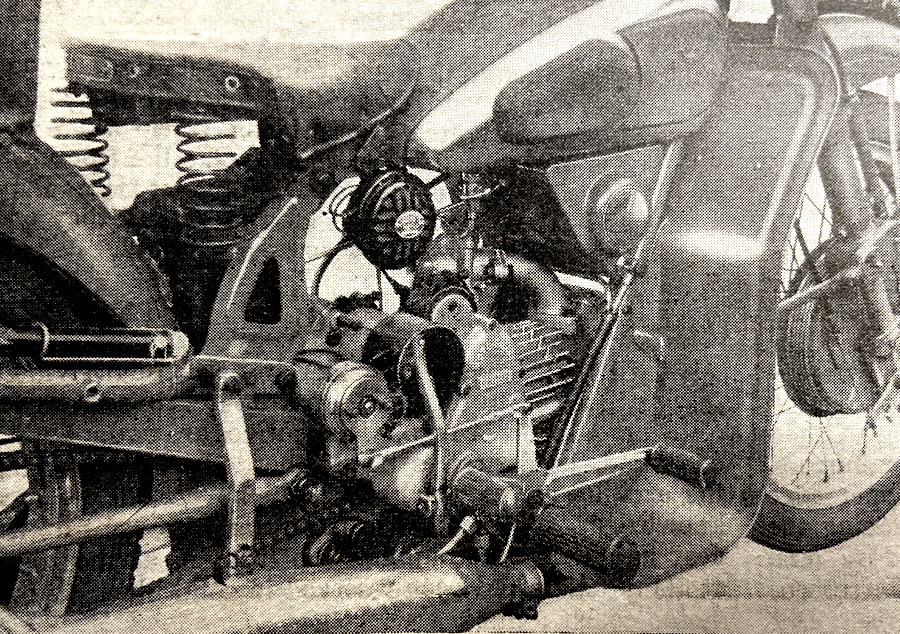

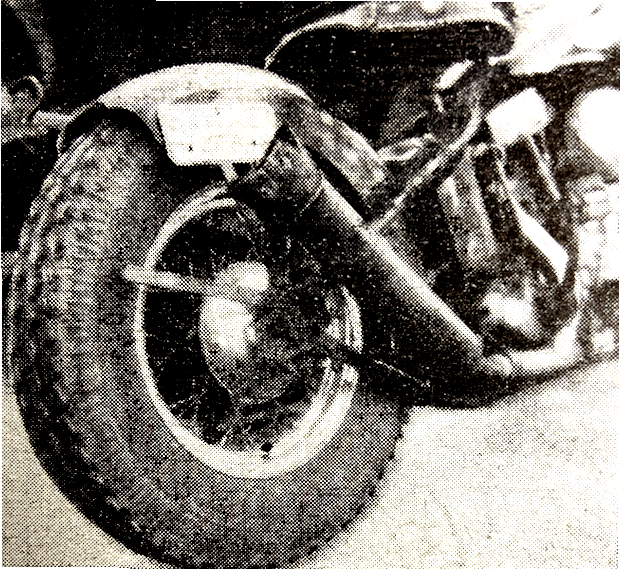

“MERE MENTION OF THE NAME ‘Black Shadow’ is enough to speed the pulse. Since the machine’s introduction last year as a super-sports brother to the already famous Rapide, the sombrely finished Shadow has achieved wide distinction. It is a connoisseur’s machine: one with speed and acceleration far greater than those of any other standard motor cycle; and it is a motor cycle with unique and ingenious features which make it one of the outstanding designs of all time. So far as the standards of engine performance, handling and braking are concerned—the chief features which can make or mar an otherwise perfect mount—the mighty Black Shadow must be awarded 99 out of 100 marks because nothing, it is said, is perfect. The machine has all the performance at the top end of the scale of a Senior TT mount. At the opposite end of the range, notwithstanding the combination of a 3.5 to 1 gear ratio, 7.3 to 1 compression ratio and pool quality fuel, it will ‘chuff’ happily in top at 29-30mph. Indeed, in top gear without fuss, and with the throttle turned the merest fraction off its closed stop, it will surmount average gradients at 30mph. In Britain the machine’s cruising speed is not only limited by road conditions, it is severely restricted. It is difficult for the average rider in this country to visualise a route on which the Black Shadow could be driven for any length of time at its limit or near limit. During the test runs speeds of 85-90mph were commonplace; 100mph was held on brief stretches and, occasionally, the needle of the special 150mph Smith’s speedometer would indicate 110. No airfield or stretch of road could be found which would allow absolute maximum speed to be obtained in two directions, against the watch. Flash readings in two directions of

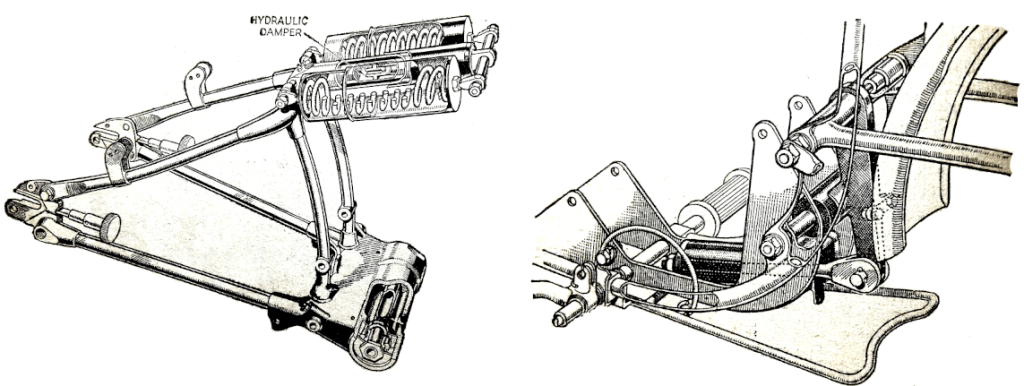

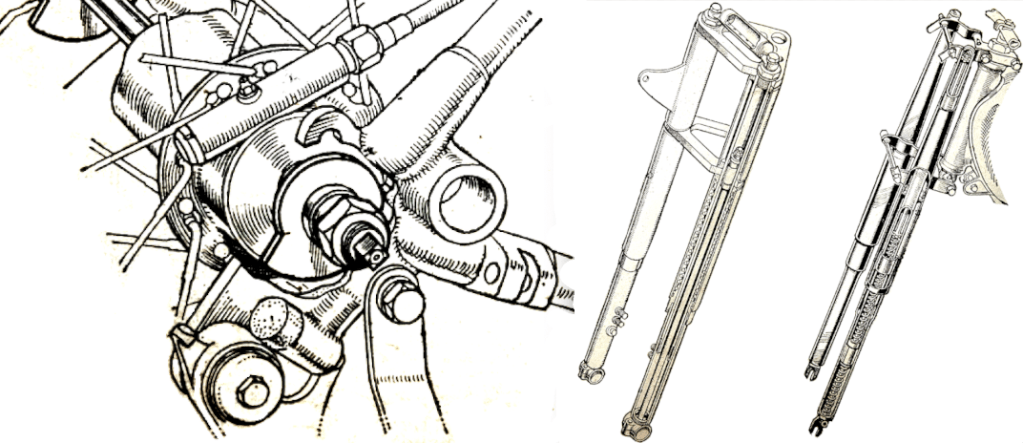

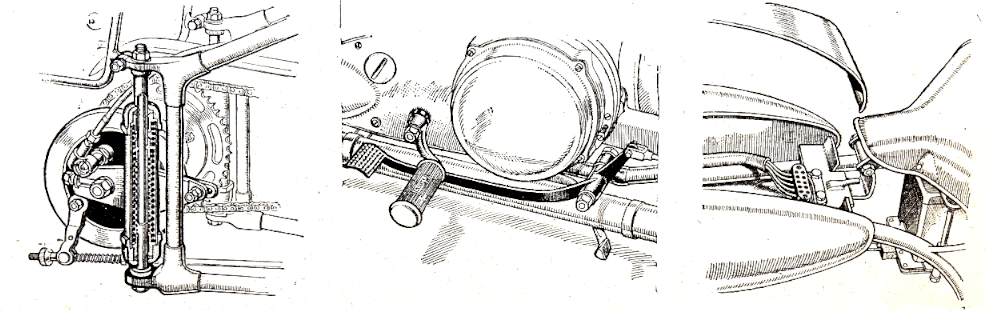

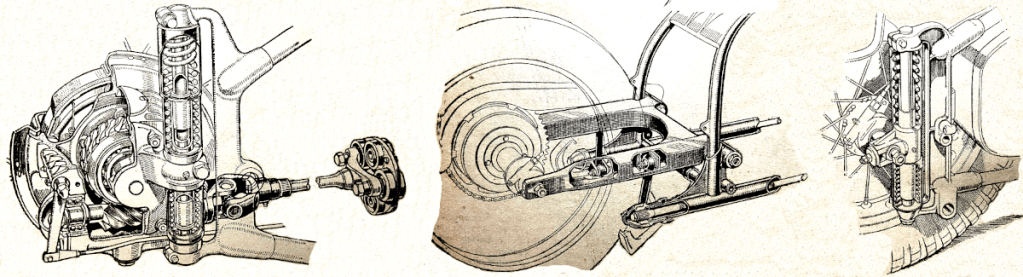

118 and 114 were obtained, and in neither case had the machine attained its maximum. Acceleration from 100mph, though not vivid, was markedly good. The compression ratio of the test model, as has been remarked, was 7.3 to 1. This is the standard ratio but models for the home market and low-octane fuel are generally fitted with compression plates which reduce the ratio to 6.5 to 1. The greater part of the test was carried out on ‘pool’, though petrol-benzole was used when the attempts were made to obtain the maximum speed figures. Steering and road-holding’ were fully in keeping with the exceptionally high engine performance. A soft yet positive movement is provided by the massively proportioned Girdraulic fork. There is a ‘tautness’ and solid feeling about the steering which engenders confidence no matter what the speed and almost irrespective of the condition of the road surface. Corners and bends can be taken stylishly and safely at ultra-high speeds. There was no chopping, no ‘sawing’; not one of the faults which are sometimes apparent on high-speed machines. Bottoming and consequent clashing of the front fork were, however, experienced once or twice. Low-speed steering was rather heavy. Any grumble the critics may have had with regard to the Vincent rear suspension has been met by the fitting of the hydraulic damper between the spring plunger units. So efficient is the rear springing now, that never once was the rider bumped off the Dualseat or forced to poise on the rests. Even at speeds around the 100mph mark, only the absence of road shocks gave indication that there was any form of rear-springing, such was the smoothness and lateral rigidity. Straight-ahead steering was in a class by itself. The model could be steered hands off at 15mph with engine barely pulling or just as easily at 95 to 100mph. The steering damper was required only at speeds over 115mph. Used in unison, the four brakes (two per wheel) provided immense stopping power. Light pressure of two fingers on the front-brake lever was sufficient to provide all the braking the front wheel would permit. One of the front brakes, incidentally, squealed when in use. The leverage provided at the rear brake is small, and the brake operation was heavy. Engine starting from cold was found difficult at first. Cold starting was certain, however, provided that only the front carburettor was flooded and the throttle control was closed. When the engine was hot, there was no difficulty. After a cold or warm start the engine would immediately settle down to a true chuff-chuff tickover. Throughout the course of the test the tickover remained slow, certain and 100% reliable. No matter how hard the previous miles had been, the twistgrip could always be rolled back against its closed stop with a positive assurance that a consistent tickover would result. The engine was only tolerably quiet mechanically. At idling speeds, there was a fair amount of clatter, particularly from the valve gear. But so far as the rider was concerned all mechanical noise disappeared at anything over 40mph. All that remained audible was the pleasant low-toned burble of the exhaust and the sound of the wind. Bottom gear on the Black Shadow is 7.25 to 1. Starting away from rest can seem at first to require a certain amount of skill in handling the throttle and clutch. The servo-assisted clutch had a tendency to bite quickly as it began to engage. The riding position for the 5ft 7in rider who carried out the greater part of the test proved to be first-

class. The saddle height is 31in which is comfortable for the majority of riders. The footrests are sufficiently high to allow the rider complete peace of mind when the machine is heeled over to the limit, and were sufficiently low to provide a comfortable position for the 5ft 7in rider’s legs. Now famous, the 25½in from tip to tip, almost straight, Vincent-HRD handlebar provides a most comfortable wrist angle and a straight-arm posture se. All controls are widely adjustable—the gear pedal and brake pedal for both height and length. Both these controls, incidentally, move with the foot-rests when the latter are adjusted. The gear change was instantaneous but slightly heavy in operation. Snap gear changes could be made as rapidly as the controls could be operated. The clutch freed perfectly throughout the test and bottom gear could be noiselessly selected when the machine was at a standstill with the engine idling. However, because of the pressure required to raise the pedal it was sometimes necessary to select neutral by means of the hand lever on the side of the gear box; and also to engage bottom gear by hand. In the 700 miles of the road test the tools were never required. In spite of the high speeds there was no apparent sign of stress. Primary and rear chains remained properly adjusted. There was very slight discolouring of the front exhaust pipe close to the port and a smear of oil from the base of one of the push rod tubes on the rear cylinder. The ammeter showed a charge at 30mph in top gear when all the lights were switched on and the road illumination was better than average. An excellent tool-kit is provided and carried in a special tray under the Feridax Dualseat. There are many ingenious features of the Vincent-HRD which brand it as a luxury mount built by highly skilled engineers who at the same time are knowledgeable motor cycle enthusiasts. The Black Shadow finish is distinctive, obviously durable and very smart; and only a minor reasons why the Shadow attracts a crowd of interested passers-by wherever it is seen!”

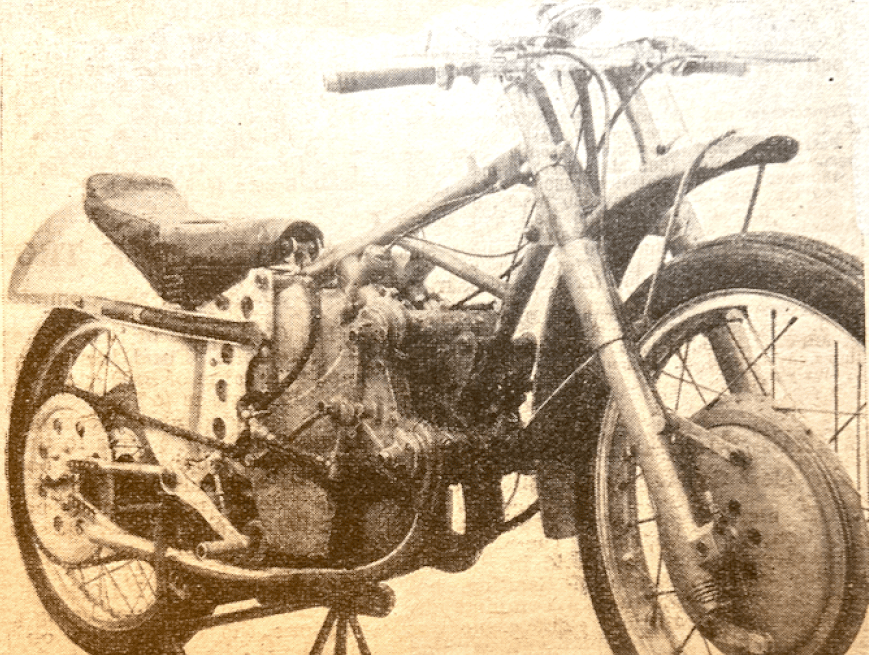

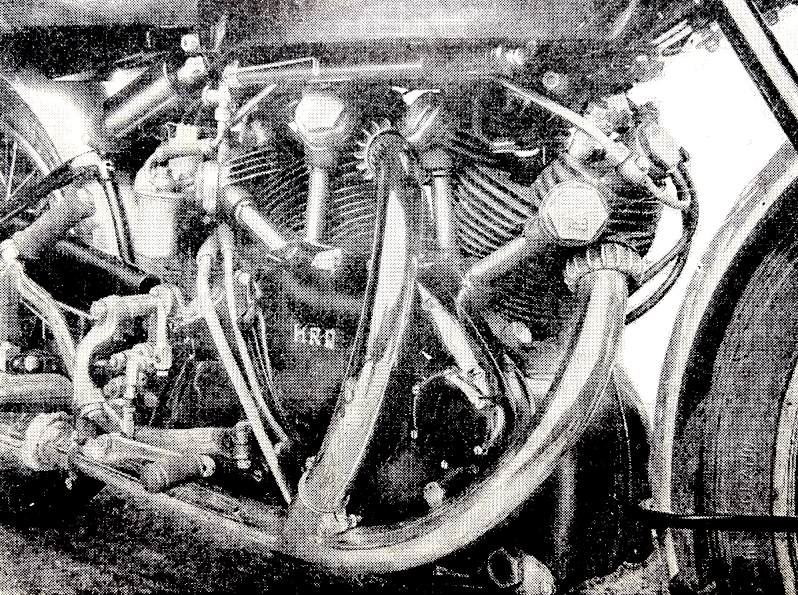

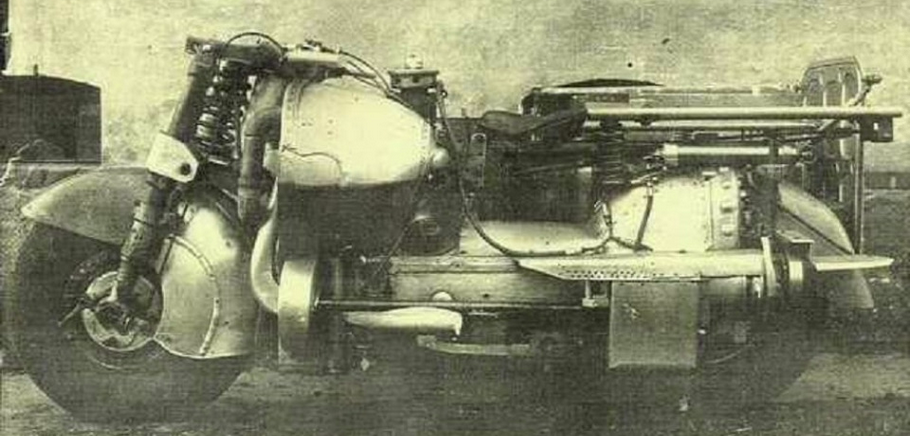

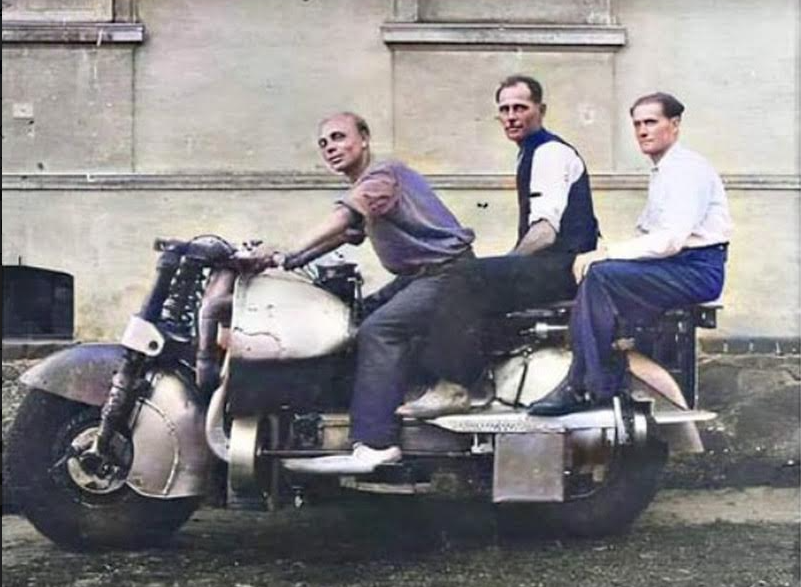

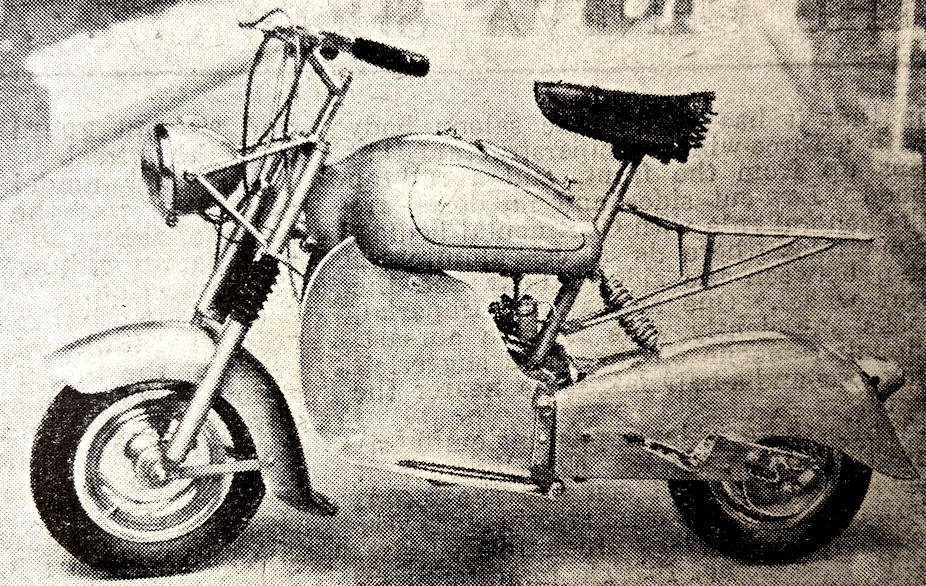

THE MSS (MOTOCYKL STANISŁAW SKURA) was an extraordinary motor cycle handmade by Polish genius Stanisław Skura. He worked at a military airbase and clearly made good use of his access to equipment and materials, particularly aluminium. Power was provided by a V-twin engine with a capacity of some 4,500cc. One source claims that Skura made his V-twin from part of an Me109 engine. If so its capacity would have been nearer 5.6 litres —in either case, Skura clearly wasn’t messing about. It drove through a three-speed box and was designed for eight passengers including the driver (three on the bike, two in the sidecar and three standing on the rear platform). Word has it (on a Polish enthusiasts’ site, and they should know) that the authorities were impressed enough that they wanted to buy the MSS1 but Skura didn’t want to sell the beast until it was legally registered in his name. The cops retaliated by ordering its destruction on the grounds that he’d used military equipment and parts including cylinders (from generator sets), conrods, gears, magneto, headlight, carbs, wheels and tyres (from aircraft), bearings, etc. Many of these parts dated from the Nazi occupation. So I reckon that was a pieprzona hańba. It seems he might well have got away with taking the MSS apart and reassembling it when the heat died down. But, like so many motor cycle obsessives, that wasn’t his style. Skura lost his rag and smashed it with a hammer in front of the Security Service men. Years later he melted down the aluminium and used it cast components for another project, the MSS500. For more on that turn to 1957.

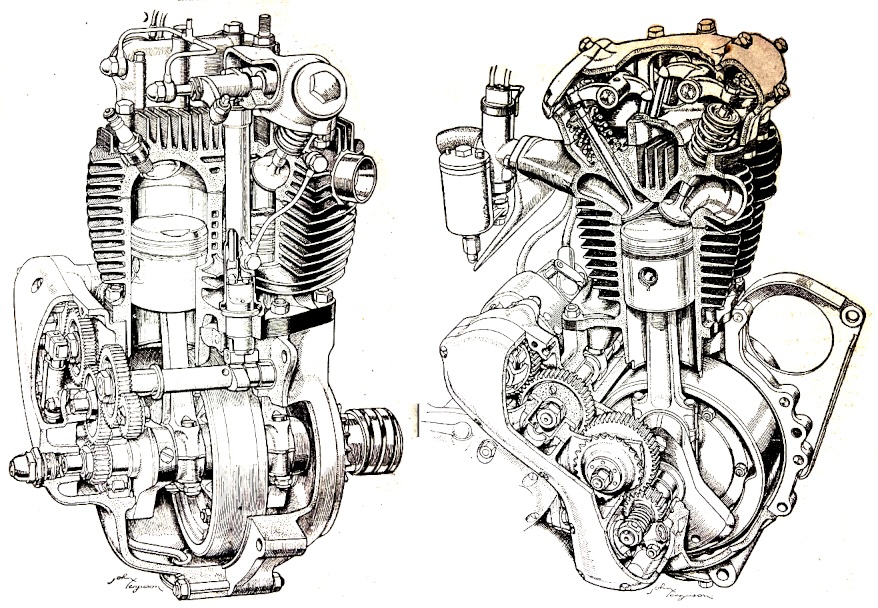

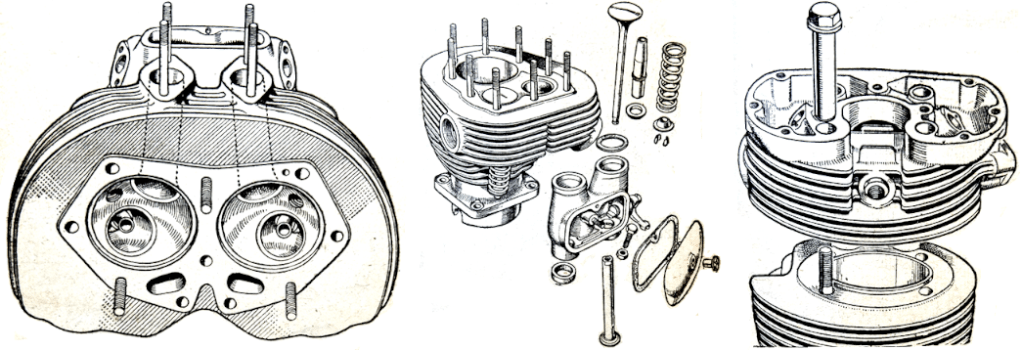

“IF THE VERTICAL TRANSVERSE-TWIN is to dominate the industry for maybe a decade, the pros and cons of the single casting vs separate pots are tolerably obvious. The single casting endows the upper half of the engine with the same rigidity which the lower half obtains from a stiff crankcase and a sturdy crankshaft. But the two-pot type can secure practically equal rigidity, provided its pots are deeply spigoted into a really stiff crankcase. On the other hand, the two-pot type should ensure slightly better cooling. Maintenance and repair should be simplified by separate pots, while a factory may save the cost of new machine tools for handling the more complex casting. It is only fair to point out that there are other methods of obtaining the extra cooling, such as the Norton splaying of the valve chests, or the light-alloy heads used by other firms. All these engines are delightfully accessible—probably more accessible than V-twins, though perhaps slightly less accessible than transverse flat-twins. On the other hand, an overhead-valve 500cc flat-twin makes an awful wide engine to set across a frame; and a 500cc longitudinal flat-twin is neither easy to house nor accessible. Worse still, its carburation is by no means easy to balance.”—Ixion

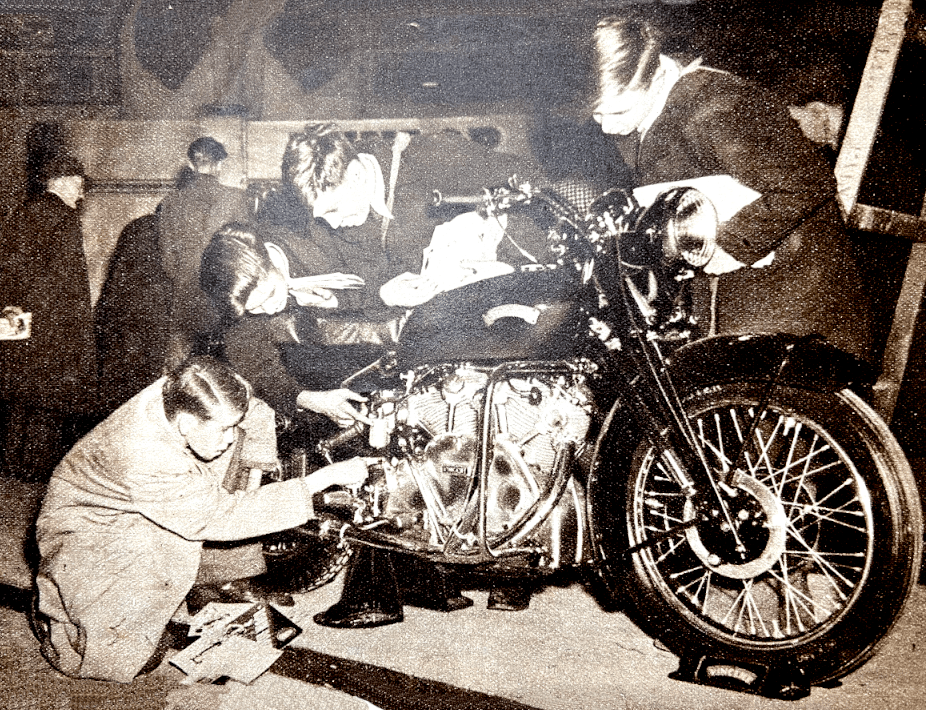

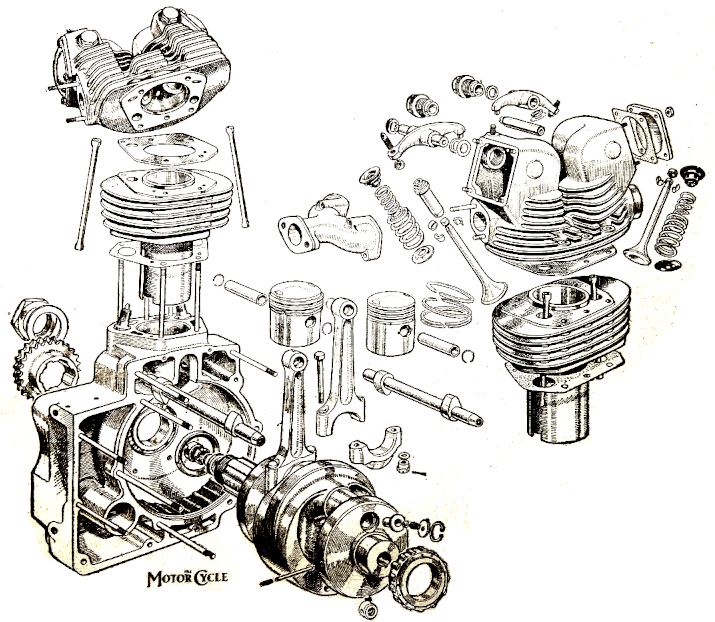

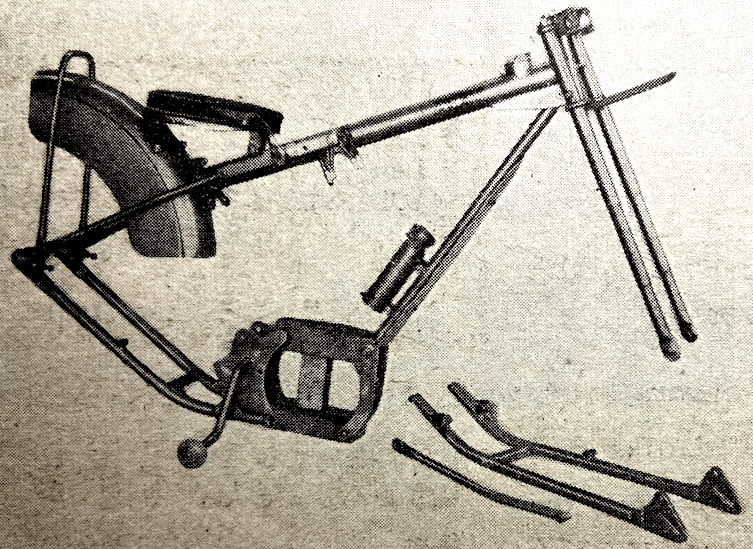

“MY LOCAL PAPER reports that a REME unit contributes a novel turn to Service displays. The squad are handed a motor bicycle reduced to its component parts, down to the tiniest nut. They assemble it coram populo* in precisely eight and a half minutes. (The reporter does not state whether the machine is a Corgi or a Black Shadow.)”—Ixion

*in public

“THE LETTERS ABOUT the BSA Sloper—why was it dropped?—caused myself and several of my friends considerable amusement. One night recently, we were coming home from the Motor Cycle Show. The roads were very wet, and my Sloper was sporting a very bad back tyre. I applied my brakes very cautiously, whereupon the bike fell rather heavily on the deck. After that, she seemed to run much sweeter, and pulled up a fairly stiff gradient at 50mph with no effort. The bike has had more knocks than a tin full of stones, and yet on four separate speedometers I have been clocked at 65mph. In conclusion, I should like to say that I would like to see BSAs make a modern Sloper, as the long-stroke, in my opinion, gives a much better performance; apologies to short-stroke fans.

GA Marskell, Greenford, Middlesex.”

“THE BRIEF LETTER from KOR/A, with its reference to ‘Nickel Tank’ and ‘Ermyntrude’, brought back memories of their delightful correspondence in your columns around the 1920s. It so happens that I was looking through a bound volume of The Motor Cycle, dated 1929-30, just a few months ago, and in it was (if my memory is correct) a letter from ‘Nickel Tank’, in which he said that ‘Ermyntrude’ had gone out to Malaya. All this may be comparatively uninteresting to the younger generation of readers, but to those like KOR/A, these ghosts from the past are very real—breathing, as they do, the great days of motor cycling. Yes, your Correspondence columns of those years were the arena for some titanic battles on average speeds, design, the perfect bike, etc.

W Dennis Griffin, Kenilworth.”

“IXION’S NOTES ARE NOT CORRECT. The wasp, when attacking, does not leave his sting in his victim; the sting is used time and time again. The bee, on the other hand, does leave his sting in his very first victim (and thereby signs his own death certificate!), and the instructions regarding the removal of the sting by means of a knife blade should refer to the bee’s sting only. A razor blade is preferable to a knife blade. Readers interested in the wasp’s methods should read The Hunting Wasp, a most interesting book (recently published) dealing with the different varieties of the wasp family.

Percy W Holmes, London, W3.”

“CAN YOU OR ANYONE prove or refute this claim—that I am present the rider of the oldest taxed and insured motor cycle in general use on the roads of the British Isles to-day? My machine is a 1921 Model SD 550cc Triumph. This machine is still working as well as ever, and has had only one new part in its 27 years service to wit, one exhaust valve. This machine still averages 100mpg. Can anyone better this?

Brian BV Crowhurst, Londonderry.”

“YOUR CORRESPONDENT, Mr Fisher, may be interested to know that the rider of the Vincent he spoke to on the Hull-New Holland Ferry was my humble self, and that I arrived back in Somerset around 11pm. Total, 723 miles since 10am. on the Thursday; 25 hours; petrol consumption, approximately 68mpg; average speed running time only), just under 41. As for the heading to the letter—’Endurance’—it was far from that. Every mile was sheer pleasure, although the trip was actually a business one. The whole point is the comfort and all-round excellence of the Series B Vincent-HRD—’ just the machine for the job’, to quote Mr. Fisher.

GT Takle, Washford, Somerset.”

“I SHOULD LIKE to reply to the detractors of the Sunbeam S7. The Sunbeam works, by putting in production the S8, will meet all the requirements of those who dislike the heavy appearance of the S7. Secondly, I should like to reply to Miss Marianne Weber, of Brussels. I have seen Miss Weber several times in Brussels riding her Ariel. I agree with her on the performance, beauty and speed of the 600cc R66 BMW. But what about the price? In 1939 this model sold in Belgium at twice the price of the Triumph T100 with the girder fork. This young lady had better leave the technical discussions to the technically minded people—the advertisers of a lightweight put it so well: ‘We do the thinking, you enjoy the fruits.’—90% of riders ignore the engines, and, as regards speed, are satisfied with less than 50mph cruising speed. The Rapide is a marvel, but not to be left in anybody’s hands, the same applies to the fast Velocettes and Norton 30 and 40 models. But the Ariel Four is like a car on two wheels, and the makers purposely did not endow this model with a high performance at the expense of good pulling is at low revs. That is all the charm of the Square Four. Nothing could be better, except, maybe, shaft-drive.

JP Simonson, Liege, Belgium.”

“I WAS INTERESTED in the leader, ‘A Neglected Market’. I have been a keen motor cyclist and a regular reader of The Motor Cycle for the past 20 years. I agree, a 750cc vertical-twin is overdue. After visiting the Motor Cycle Show I was disappointed not to find a sidecar machine to my liking. Since the war I have bought two new machines. The first one, a modern 500cc twin, proved unsuitable when in use with my large single-seater saloon sidecar and with my son as pillion passenger. The second machine is a 600cc side-valve, which is able to stand up to plenty of hard work. The first manufacturer that can produce a 750cc modern version of the 500cc twin can be assured of my order. This is the first time I have written to the Blue ‘Un. Wishing you every success.

Gwentlander, Newport, Mon.”

“I AM OF THE same opinion as Mr. Reid and other riders of the S7 Sunbeam. After riding a Model 9 Sunbeam with enclosed chains for 18 years, and being very satisfied with the good service, I placed as order for a S7 without ever seeing one, as I had such good faith in the name ‘Sunbeam’. Last August I took delivery of my S7 Sunbeam. I was delighted with its performance. The comfort, silence and smooth running was unbelievable; the way this model holds the road makes motor cycling a real pleasure. As regards ‘XT80’s’ remarks about speed, the S7 has more speed than I can use on our dusty roads. The air filter, rear-springing and shaft-drive are more important to me than speed. Past experience showed that exposed rear-chain drives soon wear on our dusty roads. During the past 24 years I have owned. two Triumphs and three Sunbeams, the latter Model 9s with totally enclosed chains. And now Mr Wray and ‘Ex-250 Sports’ consider the Douglas and Twin Triumphs better than the Sunbeam. I consider both the Douglas and Triumph are behind the times with their exposed back chains, and this is one of the reasons why in 1928 I changed from Triumphs to Sunbeams. Wishing’ all the best to The Motor Cycle, which I enjoy.

RS Gordon-Hughes, Transvaal, South Africa.”

“AS A FORMER OWNER of a Sunbeam S7, may I contribute to the fray? I covered over 5,000 miles on my model between October 1947 and May 1948, and was left with mixed feelings when I sold it. The S7 was superlative in many respects, but had several drawbacks from my point of view. Comfort, silence, design, ease of cleaning, and finish, were among its endearing features, but at the other end of the scale were snags like the following: Average mpg, 55; maximum speed, 70mph; heavy oil consumption; poor starting in cold weather (due to insufficient kickstart leverage); oil leaks; mediocre acceleration; and poor steering due to the upright angle and staccato action of the front forks. In conclusion, I would say that, in my opinion, the S7 has not been influenced sufficiently, in its design and development, by the views and criticisms of the most critical and knowledgeable of all motor cyclists, the works’ testers.

JR Hawkes, Birmingham, 8.”

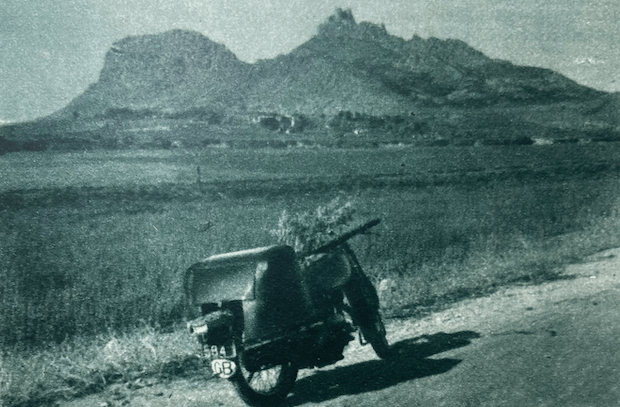

“ONE RARELY ASSOCIATES Turkey with a motor cycle journey. I was fortunate in being able, in the course of some three weeks, to make a complete road crossing of the country from Adrianople, in the north-west, to Antioch, down on the Syrian frontier. The capacity of my mount was only 250cc, but this had the advantage of giving a greater fuel range, a most desirable feature in a country where petrol stations are few and far between. I entered Turkey by way of the Balkan ‘backdoor’. First of all, the frontier guards had to man an impressive fortification, then I had to wait while they patrolled ‘no-man’s-land’, and finally I was given an armed escort with whom I had to travel at walking pace to the customs house. Here an official in immaculate white dress awaited me. I was asked to declare all my gold and silver and valuables. The completion of this operation was almost instantaneous, whereupon I was allowed to continue over the worst road ever, to Adrianople, in order to introduce myself to the police—a most necessary proceeding. A motor cyclist from Bulgaria was a completely unknown factor. I was told that I must continue at once some unspecified distance to a place which would be indicated to me, in order to catch a train which would carry me to Istanbul, as my road route traversed a military area and this was absolutely forbidden. I protested that I had no money or petrol, whereupon a local garage was ordered to supply me gratis. The Oriental spires and domes of Edirne intrigued me, and I sought any excuse which would delay action. But the police were adamant—I must catch the train that night. The journey was a nightmare. I was delayed by other police and military, but this was not so serious as the state of the road; and once I met a lorry driver

who made me understand that I would never reach the railroad that night. I told him of my orders and grimly carried on. A minor track led me into the wilderness. Dogs came rushing at me with savage intent, then, as the light failed, a military outpost stopped me. Trying to convey my mission, I attempted to proceed, but was roughly detained. All my luggage was pulled out and thrown into the road; the men pointed to the unadorned shoulders of my leather tunic. Did they suppose me to be a fugitive from Greece? Then they discovered my camera; it was fortunate that there was no film in it. I was led into the most primitive mud and wattle hut. By this time I was so completely fatigued, having been on the road since an early hour, that I took off my boots and leggings, ate some dry bread, and lay down on a rough bed. No sooner, so it seemed, had I fallen off to sleep than I was roughly awakened and made to dress and proceed. I remonstrated, saying that the train had now gone. So I drove, in a trance, through the silent Turkish night. Night driving was not part of my plan, but the play of light and shadow set up by my head lamp clearly indicated the deeper pot-holes and dictated my course. In the far-spaced villages the police had turned out to meet me. They ceremoniously saluted, waving me on. Still I continued, often considering sleeping by the road. Then suddenly I came upon the railroad and slowed down. Police and a man came running towards me. ‘This way please,’ directed the man, in English. After I had supervised the loading of my machine the man took me into a nearby cafe and treated me to my first Turkish coffee. It was hot and sweet and strong, but the cup was truly minute and one had to be careful not to drink the dregs comprising the lower third of the cup. Once in the train, I had a personal guard who lost no time in securely locking me into my compartment. Not that I wished to escape, for, as my host had smilingly told me, my road—that is the railroad—was unquestionably the best. A faint wisp of beautifully brilliant, Turkish crescent moon, set in the velvety vault of outer space, enabled me to see little of the forbidden wilderness, and next day I was bumped and jolted along the coast of the Sea of Marmara to Istanbul—

Constantinople—star city of the Near East. Here, having passed through the military area, I found freedom again. In this city, which stands between east and west, where Oriental splendour and Western civilisation meet, I had new experiences and made all kinds of contacts. It was a revelation. Soon I met some Englishmen and quickly learnt that if I wanted a gallon of petrol, all I had to do was to point to my tank and say ‘dirt’, or if a litre of oil was required, to point appropriately and say ‘beer’. Here butter became ‘terry air’, and if one wanted eleven of anything one simply said, ‘on beer’. It was all very quaint. The open road lured me on towards the heart of the land of the rising sun—Anatolia. First a tarmac road led me from the Bosphorus peninsula to some low hills. Then there was a shocking stretch of pot-holed track where speed was reduced to some 5mph. But later I entered upon really mountainous terrain, stony hairpin bends taking me ever farther from civilisation. When the light failed I camped for the night. At 5am I was awakened. The police had come to investigate my presence in the mountains. My passport satisfied them, and when we had all shaken hands, the will of Allah was invoked and we parted most friendly. When the sun was still below its zenith I reached Goynuk. Here veiled women still silently walk the narrow, cobbled main street; the mountain setting, the eastern architecture, and the stately spires of a mosque set on a hill, complete the picture of a perfect Turkish village. The colours are vivid, and the contrast between light and shade makes everything stand out in bold relief. Beyond Goynuk one enters upon a tract of and country that is uniquely Turkish, an area where Nature’s artist has, as it were, been given a free hand and man cannot mar his efforts. For entire hills and mountains are splashed with every conceivable shade of colour, and even the scant vegetation harmonises with the wild scheme. The road is no less bold in its convolutions, taking one to dizzy heights only to zig-zag dangerously into the neighbouring valley. Then the traveller sees the silky coats of the famous Angora sheep and knows that he has almost reached the capital. Ankara is a strangely isolated city, like an oasis in the desert, yet it knows no isolation to-day. Flashy taxis glide noiselessly past, electric trolley-buses carry well-dressed city workers to the suburbs, and everywhere the ancient is giving place to the modern. Even the Orient is becoming westernised. Yet the traditional hospitality and the long drawn-out processes of bargaining still linger on. It was hot in July, and I was glad to make for the open road once again. The folds of the mountains soon reclaimed me. Always I travelled with a smoky white wisp, extending to an all-pervading cloud, of dust in my wake. One had to be constantly on the alert for tortoises, sometimes large ones, on the road. I travelled 70km off my route before I discovered my error, due to a signpost being blown out of place; and on the return journey one of my luggage-locker bolts sheared. Only a hundred yards away there was a dead horse now well decayed and, as I struggled unprotected in the merciless sun, a caravan of camels sailed silently past. Out in the wilds, about halfway between Ankara and Adana, my last luggage spring snapped, so I drew into a

small village for coffee. Of course, everyone must see the strange traveller, know his complete history, and handle his passport to see for themselves. I was used to this. The item which interested them most was the fact that I was described as an ‘electrical engineer’. Now the proprietor of the café had a radio which would not function properly, so they indicated that I should repair it. Eventually the set was placed before me, I was provided with food and fruit, and all the village assembled to watch the English engineer perform. I found one or two minor faults, but the reception of Ankara Radio was not greatly improved. So I told them to take down their aerial and to climb up and attach it to the ramparts of some ancient building, which I hoped was not sacred. They carried out my minute instruction, whereupon the strains of Oriental music burst forth with renewed volume, the awed silence of my audience changed to universal applause, and I was invited to become their guest for the night. After a night in a mud hotel with a woven-grass ceiling and an ancient lock on the door, I was bumped and shaken for four hours on my way to Nigde. Then a good tarmac road took me into the snow-capped Taurus Mountains. I stopped to change a plug. I had almost finished putting my tools away when a lorry-load of Turks came to investigate my stoppage, wanted to pack all my gear in quickly and load me on to their lorry without delay, for were we not all bound for Mersin, they reasoned? I protested and showed them that my machine was still very much alive, whereupon they continued, quite crestfallen. Later I became their honoured guest. They stopped me on the road, directed me to a gushing spring to wash, and bade me be seated. They all squatted round, some almost in the river which ran alongside. Bread and tins of delicacies were produced; then apricots, water-melons and grapes. I was pressed to eat until I could take no more. The comradeship, the perfect evening, and the matchless scenery, are experiences never to be forgotten. They were honouring the stranger whom Allah had sent! Next day I met the nomads, then passed through the Cilician Gates, in the steps of Alexander the Great, on the way to ancient Tarsus. As I descended from the heights the heat became almost unbearable, and the uneven tarmac road performed the most unbelievable antics. Suddenly, I was almost hurled down the mountainside. My rear tyre had succumbed to the heat. No sooner had I stopped than a lorry was beside me. Next we were man-handling the heavily-laden machine on to the lorry, which was already loaded with rock from the nearby quarry. I was given a seat in the cab and a slice of water-melon to refresh me. That is the Turkish spirit of the road. While my tube was being repaired I went to see the ruins of Tarsus; then I drove to Adana, Alexandretta, and on to Antioch. My Anatolian adventure had ended.”—R Hunt

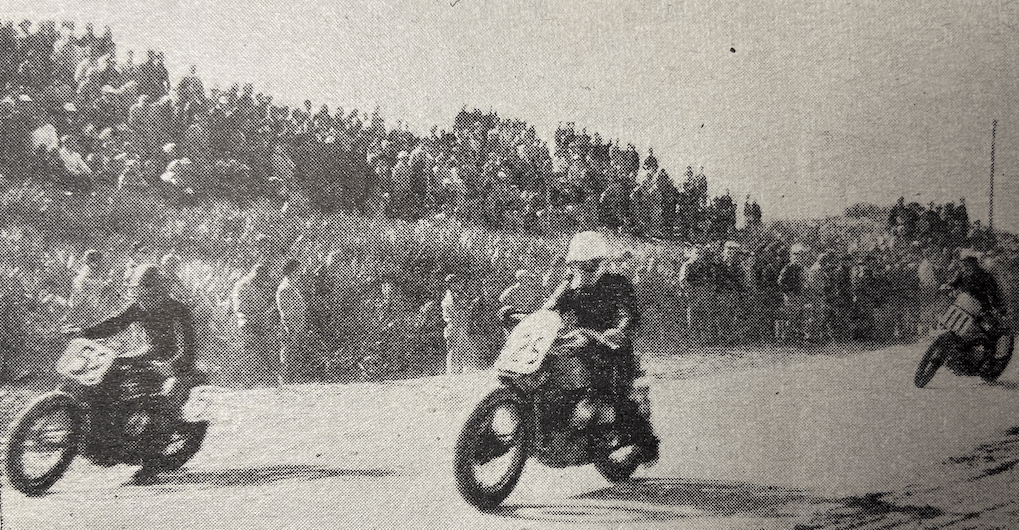

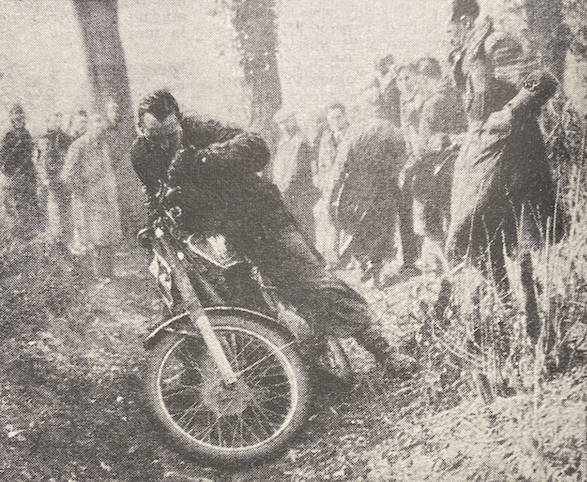

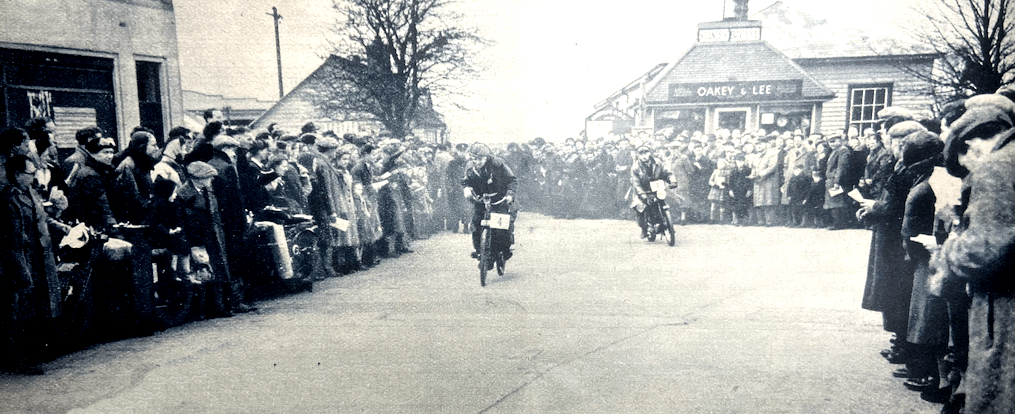

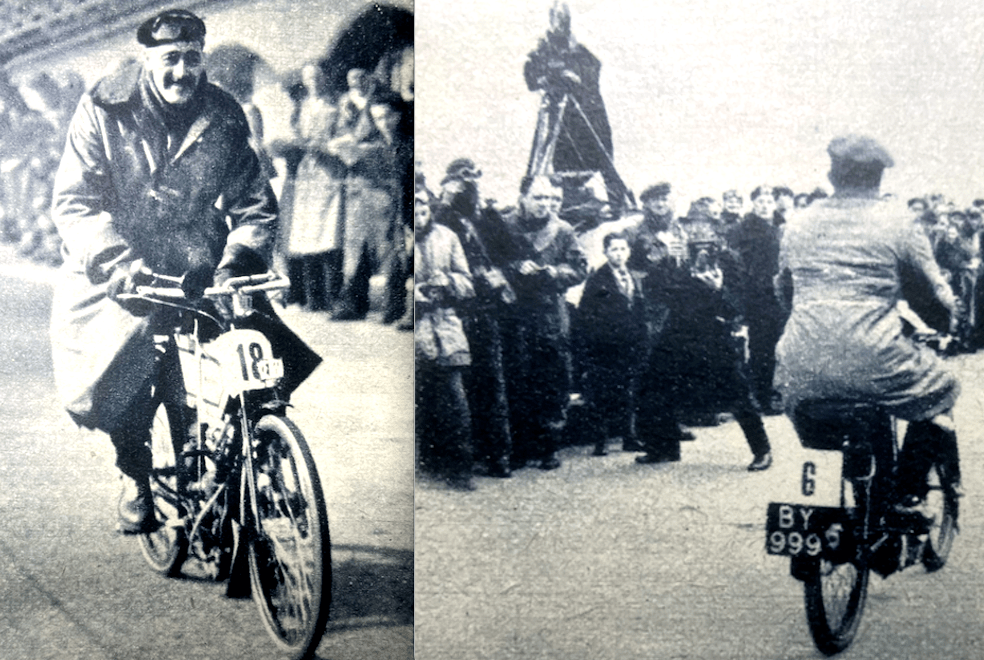

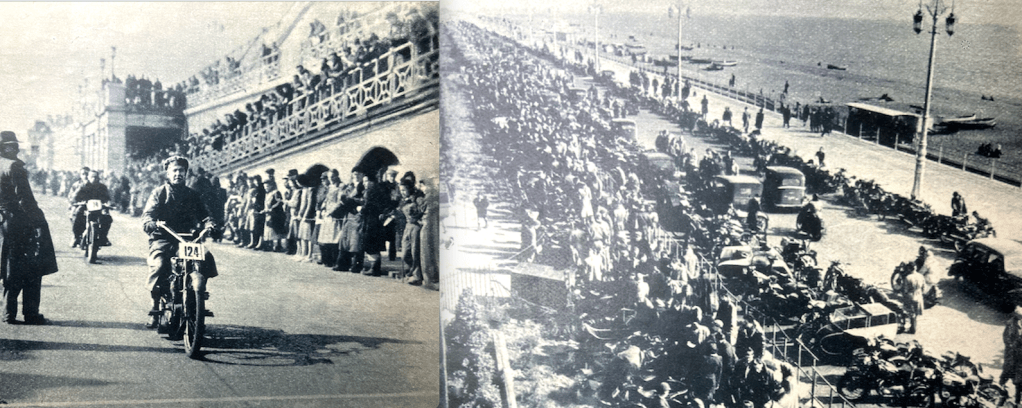

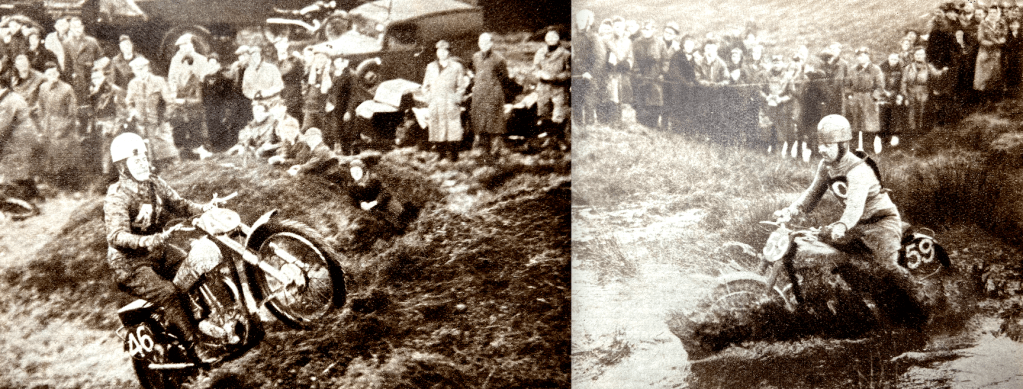

“FOR THE OPEN-TO-CENTRE Tottenham and Barnsbury MCC Team Trial, held over an approximately 16-mile course in the Hoddesdon area of Hertfordshire last Sunday, the New Year weather was pleasantly mild. The course was in ripe condition after the gales of last week. There was mud and to spare and this, in conjunction with the rather flat nature of the countryside, gives a clue as to why the trial was won by a sidecar. There were 131 starters. On Roman Road, one of the choicest sections over slithery three-ply mud, there was little trouble for the three-wheelers. Under the mud there was ample wheelgrip and the third wheel served as a useful ‘prop’. For the solos, however, it was a different proposition. Even BW Hall (350 Matchless), of scrambles fame, had to foot; and, on a 350cc Special, George Brown, intrepid road racer, appeared extremely timid! RESULTS: Tottenham and Barnsbury Trophy (best perf), PC Mead (490 Norton sc), 6 marks lost; Tottenham and Barnsbury Trophy (best opp perf), J Manning (500 Matchless), 6; 250cc Cup, C Pattriek (250 AJS), 15; 350cc Cup, M Banks (350 Ariel), 9; Senior Cup (best over 350cc) and Novice Award, FJ Agar (490 Norton sc), 15; Griffiths Bunyan Cup and Award (best club member), R Leonard (350 Matchless), 34; Team Award, Dunstable (LJ Bowden, BW Hall, CW Wright), 33.”

“AT THE SECOND South African Hill-climb, held on Burman Drive, a crowd of nearly 6,000 saw records fall in the 250cc and sidecar classes. The course, which consists of a mile of 30ft-wide tarmac road, starts on a gradient of 1 in 20. Initially, the road curves gently for one-third of a mile, and afterwards there are four acute right and left bends encountered in about 300 yards. The course then bends gradually round to the left, and the gradient stiffens to about 1 in 15 near the finish. A rolling start of about 75 yards preceded the time section. Competitors were allowed three runs over the course (without any practice) and the best times put up counted for the championships. There were also general handicaps for solos and sidecars, without which no South African race meeting seems to be complete. The first runs were notable for a climb by R Millbank (499 BSA) who ascended in hectic fashion in 1min 8.9sec; he followed by taking up a 495cc Velocette in lmin 9.6sec. The scratch man, W Duxbury of Johannesburg, riding an ex-works 490cc Norton brought back to South Africa in 1936 by Johnny Galway, made an ascent in lmin 10.1sec—an excellent effort in view of the fact that Duxbury had never ridden on the hill before. At the second attempt most riders improved on their first times. Duxbury brought his time down to lmin 8sec which, while good,

was not fast enough to match the adventurous Millbank, who achieved 1min 7.5sec on his Velocette and lmin 7.1sc on the BSA. The third runs were, as might have been expected in the absence of any practising, fastest of all, and Duxbury’s polished ascent in lmin 6.2sec was good enough to secure for him the best time of the day and the 500cc National Championship. Millbank ran him very close on the Velocette, however, and was only 0.2sec slower. An astonishing performance was put up in the 250cc class by RJ Schroeder (248 Velocette), who climbed in lmin 10.2sec, thus winning the 250cc National Championship for the second year running and breaking his own record for the hill in this class, which he set at lmin 11.9sec in 1947. The sidecar record for the hill (held by the late JE van Tilburg) was broken by AE Norcott (490 Norton sc), a scratch man who recorded 1min 10.6sec. For the 350cc National Championship there was a tie between D Sutherland and WA Gwillam, both of whom rode Velocettes and ascended in 1min 8.5sec. In the general solo handicap R Millbank took both first and second places on the two machines he was riding, and in third place was RJ Schroeder on his amazing little MOV Velocette. J Fuller, riding a 1,200cc, Harley-Davidson, won the sidecar handicap. RESULTS: National Championship, 250cc, RJS Schroeder (249 Velocette); 350cc, DU Sutherland and WA Gwillam (348 Velocettes), tied; 500cc, WH Duxbury (490 Norton); Solo Handicap, R Millbank (495 Velocette); Sidecar Handicap, J Fuller (1,200 Harley-Davidson).”

“OFFICIAL RIDERS OF Norton machines in 1949 trials and scrambles will be GE Duke, AJ Blackwell and RB Young, solos, and AJ Humphries, sidecar.”

“SIR MALCOLM CAMPBELL, MBE, who died on December 31st, started his career of speed on a motor cycle. At the outbreak of the last war he was responsible for forming a company of special motor-cycle mounted military police.”

“FOR MANY YEARS that South-Eastern Centre favourite, the ‘Three Musketeers’. has been held in the flat, muddy country south of Reading, but last Sunday’s trial was a complete departure from tradition. The scene was shifted north, to the pleasant, wooded slopes of the Chilterns, and despite an increasingly wet day the move was universally popular. Over 150 competitors converged on the Lambert Arms, Aston Rowant, and the 25-mile route (excellently marked) soon brought difficulty in the form of Icknield Way and Crowell Hill; and neither section was negotiated clean by any of the solos. Later, New Copse, Turville Heath and Pyrton Hill all took their toll, with only about half a dozen clean on each. Despite the rain, the trial was finished in good time, and the South Reading MCC are to be congratulated on an excellent event. RESULTS: Best Solo, GM Berry (499 Royal Enfield), 16 marks lost; Best Sidecar, F. Wilkins (497 Ariel sc), 23; Best 250cc, CH Jennings (249 Velocette), 39; Best 350cc, AF Gaymer (349 Triumph), 23; Best 500cc, AJ Blackwell (490 Norton), 35;Best Novice, K Bond (497 Ariel), 46; Best Team, Weyburn (GM Berry, AF Gaymer and PJ Mellers), 92.

“WHILE I DO NOT WISH to shoot any lines other than those which concern our grand paper and (I was going to say) my even grander model, I do feel someone should refute ‘MP’s’ assertion that ‘very few could ride a machine at over 90’. Although only a ride-to-work merchant, I feel very disappointed if we reach our destination without clocking 90 at least once! Let’s have less namby-pamby adulation of silence and comfort—what’s happened to the post-war rider?

MPA 424, London, W11.”

“I AM CONSIDERING selling my old ‘cammy’ Norton shortly. If DFR, of Blackpool, would care to lend me the speedometer off his Tiger 100, I am sure I could make a better price for my machine!

Douglas Rose, Corby, Northants (Stewarts and Lloyds MCC).”

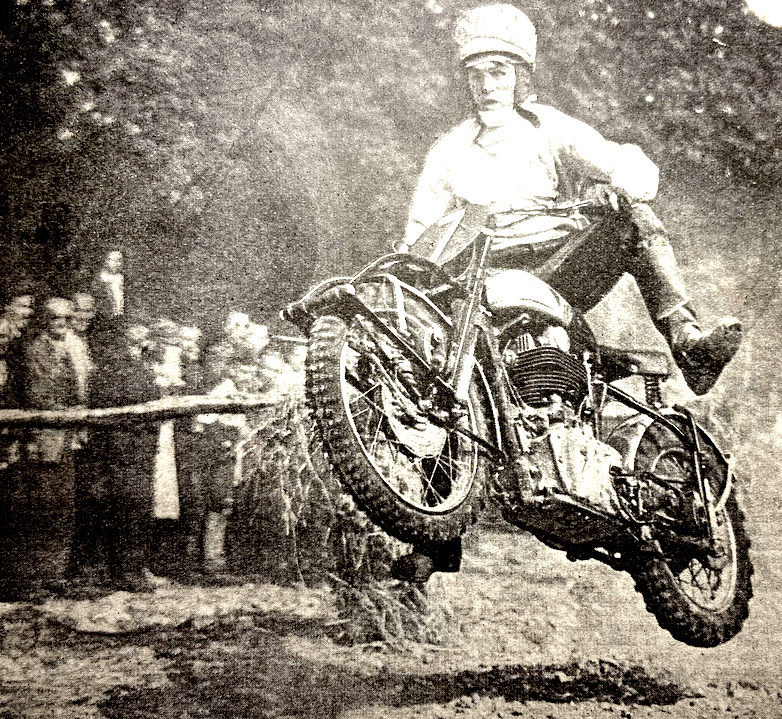

“IN PREVIOUS EXETER TRIALS, right from the first in 1910, if a competitor cannoned into the bank on an observed hill, it was always possible to say, ‘Poor fellow! What else can you expect? He’s tired out after his long ride through the wild, winter night.’ But there was no such ready excuse on last Saturday’s ‘Exeter’. For reasons of petrol economy the trial began and finished at Exeter and embraced barely 60 miles. In that distance there were the two chief ‘teasers’ of the pre-war events, Fingle Bridge, near Drewsteignton, and Simms Hill, near Ilsington, and five lesser acclivities. The entry of 90—53 cars and 37 motor cycles—was made up in large measure by folk living in the West Country. As is usual with the Motor Cycling Club’s (normally) long-distance trials, a fairly big proportion of the entry, to judge from performances on the hills, were comparative novices. And the course, in the condition it was last Saturday, was probably sufficiently difficult, although by modern trials standards, it was easy. Windout was the first hill. At the foot there was a muddy torrent, which, from its appearance, might have been anything up to 18in deep. It was not half that depth and, anyway, was unobserved. Possibly it would have been kinder to competitors if the observed section had started previous to the splash, because, as it was, riders were forced to restart on a muddy upgrade. The hill looked at its worst—first, leaves, soggy mud, small rocks firmly ensconced and others loose; then two hairpin bends with shale, mud and a meandering gully down which water was flowing and, finally, more roughish, muddy going. The first arrival was the ACU-registered owner of the nom-de-guerre ‘Jimmy Green’, on a 497cc Ariel. He was happy in both method and mien, and used the banks at the hairpins. Next came AT Robinson (349 Triumph), who stopped very early on, restarted and was just making a running commentary to the Press about his clutch being finished when he stopped again. Mrs ML Anning (347 Matchless) made a fairly fast climb, but even she with all her ‘local’s knowledge’ (or because of it) dabbed with one foot between the bends. So far there had been one failure, one foot and one clean…A minute later there was another failure, CE Dawkins’ 249cc Rudge being unable to pull what seemed to be a hopelessly high bottom gear. A very old hand on a very new motor cycle came next—SH

Goddard with a 197cc Ambassador. He shot round the first bend with a sideways flick of his rear wheel. So good was he that he caused spectators hurriedly to examine their programmes to find out the name of the maestro. EJ Bores (348 BSA) was also excellent. En route from Windout to Fingle Bridge there was the first of the two special tests—a simple, timed roll-downhill-cum-brake test included in case of ties for the team awards. Fingle has an entirely different appearance from pre-war. Gone are all the big trees that flanked the zig-zag track of many hairpins. Gone, too, are many of the rocks and, for a solo machine, there was a good. hard and fairly smooth track nearly all the way up. Even the ‘loose’ was comparatively innocuous. There were two observed sections with a restart in between. The first included the sharp right turn near the bottom which is apt to fail car drivers—this and the long easy stretch. The only difficulty here for the motor cycle entry was that for a few minutes the sun was out and glaring straight into competitors’ eyes as they approached the hairpin. There were occasional minutes of sun, but a far larger proportion of storm, including gale-borne hail. Higher up, at the succession of hairpin bends, the method was to cross and recross the track so as to round each hairpin on the hard, easy grade outside. Goddard had reason to bless the gap between the observed sections: he was able to stop and tighten up a footrest. Mrs Anning was excellent and so close to the side in places that her riding coat brushed the twigs. A small stone diverted the front wheel of FC Bray’s single-cylinder Triumph. He was high on the rests and, in endeavouring to correct the plunge, smote the bank and fell off. WA White (498 Matchless) was so good that from the ranks of the spectators, in good Devonian, came the remark that he had been up before! DS Ham (490 Norton) also made a neat climb, but took a peculiar path towards the summit, straying into the loose. FW House (349 Triumph) was perfection, and W Bray with his 125cc Royal Enfield had plenty of power in hand, his engine four-stroking at times. AC Hosking (498 Triumph) toured up effortlessly. D Witney Jones (348 BSA) touched the left bank with one foot for no very apparent reason. Then there was a particularly clever exhibition of riding by WG Arthur (498 Matchless). His rear wheel indulged in a trio of sideways hops, which he corrected by deft handling. Two others who were especially good were 0S Jose (498 AJS) and RHB Jones (348 Norton). Next on the list of famous hills was Simms, but in between were three lesser acclivities. The first was Knowle, which accounted for three ‘foots’ and no failures, W Bray, AT Clark (250 Rudge) and HW Tucker (348 Ariel), each putting out a foot. Stonelands, too, was a very easy

proposition, there being a well-washed track down the middle. Even Simms Hill, of 1 in 3½ average gradient was in very easy mood. Pre-war there was usually a good, hard path on the right and to eschew this in favour of the left was to court wheelspin, skids and failure. Now there is grass on the right and, for solos, an easy path on the left with merely one small rock ledge as a hazard (other than the towering gradient!). Goddard, with the Ambassador, again made a good climb, so did ‘Jimmy Green’ and Bray. Mrs Anning got rather too close to the left and had some wheelspin. RW Knox (elderly 584cc Douglas) rounded the bend at the foot very slowly and stopped. Touring climbs were frequent. AC Hosking was an exception—petrol tap off, it seemed! The Scott ridden by FT Hosking ‘wowed’ up, its exhaust rising and falling in thrilling fashion. RH Litton (349 Triumph) stopped after plaintive comments from his engine. A minute or two later the first sidecar arrived—JW Smith (490 Norton), who was both fast and excellent. WAC Goddard (Triumph sc) seemed likely to be equally good, but suddenly his engine cut out, leaving the onlookers wondering why. FW Osborne (592 Levis sc) was good, but neither Morgan exponent, WD Griffin nor WE Wonnacott, escaped the attention of the tractor and its tow-rope. So to Green Lanes, which had hundreds of gallons of water an hour swilling its surface, and was therefore easy, and to the finish just outside Exeter—the finish of an ‘Exeter’ that was ‘different’ but, in spite of all the hail, a most enjoyable trial. RESULTS: Premier Awards, ‘Jimmy Green’ (497 Aerial), Mrs ML Anning (347 Matchless), EJ Bores (348 BSA), WA White (498 Matchless), DS Ham (490 Norton), FW House (349 Triumph), 0S Jose (498 AJS), RHB Jones (348 Norton), JM Bowen (349 Triumph), WF Martin (348 BSA), AN Cornell (350 Martin), JW Smith (490 Norton sc); Team Prize, FC Bray (498 Triumph), DS Ham (490 Norton), FW House (349 Triumph).”

“FOR MANY YEARS ‘spring heels’ has been in common use to describe rear-springing. It has always seemed to me to be a most expressive term for plunger-type suspension, and a slight modification to ‘spring heel’ fitted the pivot-action type, à la Vincent-HRD, with tolerable accuracy. However, now that there are other types such as the Triumph spring hub (or should it be spring wheel ?), the pivoting rear fork with telescopic legs or with torsion bars (or, perhaps later, with rubber in shear), I am beginning to wonder whether we ought to scrap ‘spring heel(s)’ and think up another generic term which is more accurate. Anyone feel like making a suggestion?”—Nitor

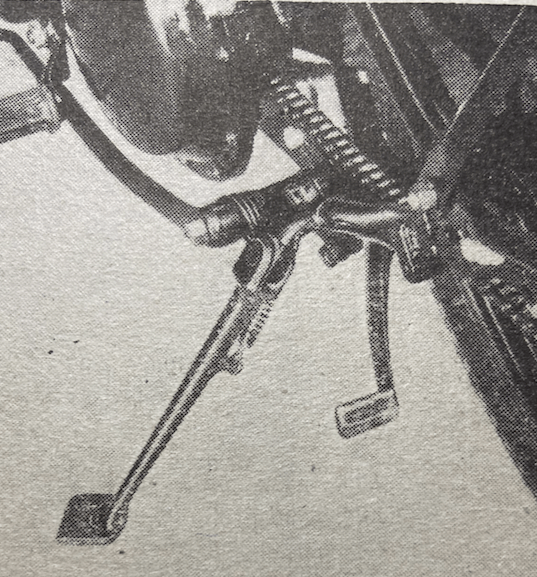

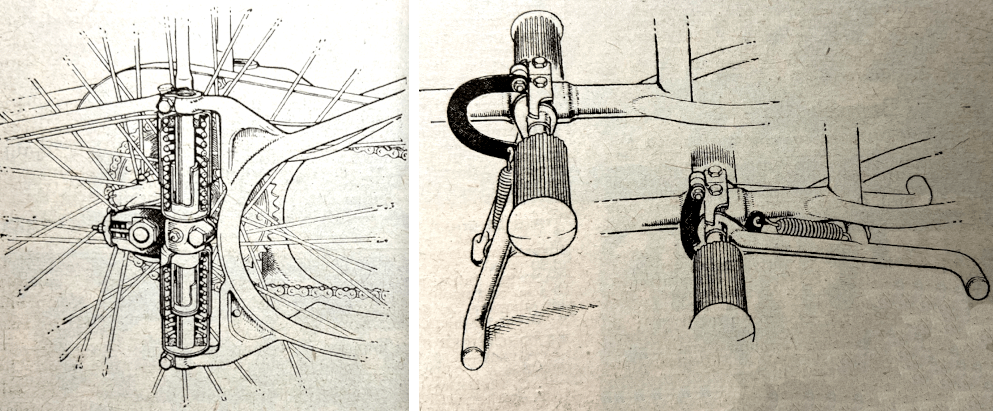

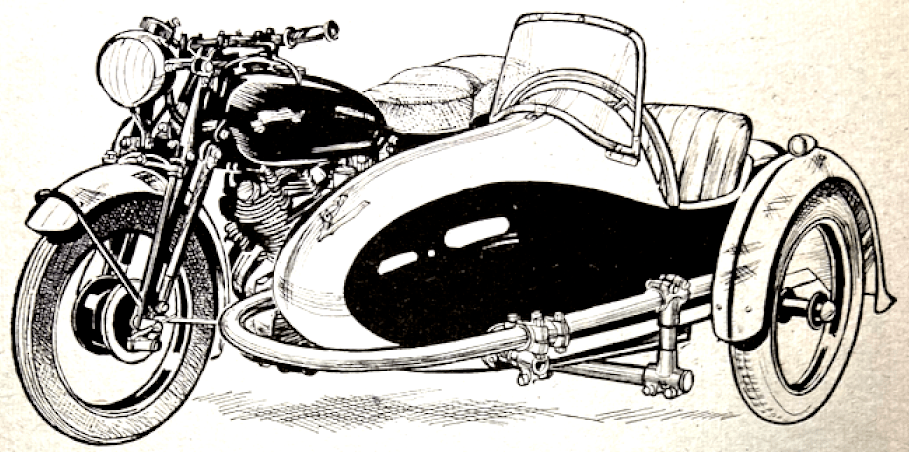

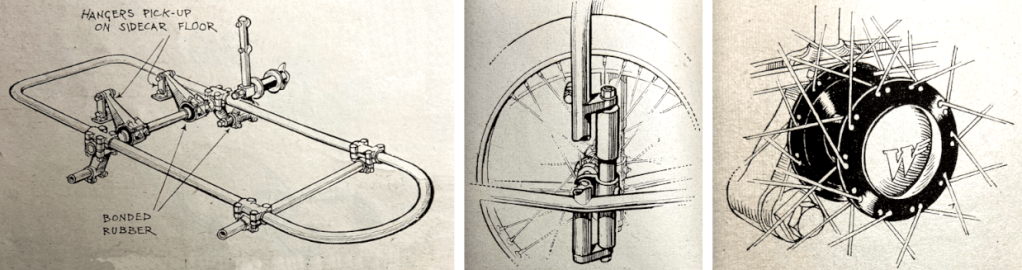

“LATELY I HAVE been very sidecar conscious after a visit to an old friend who specialises in sidecar fitting. He told me many interesting stories about the malalignments he is called upon to cure and, ‘I dunno how the lads drive ’em’, was a frequent interpolation. In the past few weeks I have purposely followed at least a couple of dozen outfits and I should say that some 50% were badly aligned—machine leaning in towards the sidecar was the most common fault. I am sure those drivers do not realise how much more pleasurable their riding would be if their outfits handled properly—for malalignment can always be felt at the steering. The standard recommendation is that on level ground the machine should be vertical or lean away from the sidecar slightly (up to 1in from the vertical measured at the steering head), and the sidecar wheel should toe in ⅜ to ½in—this measurement taken at the front end of boards laid alongside the machine wheels and the sidecar wheel. If difficulty is experienced in obtaining these settings, or if the settings are correct and the handling of an outfit remains below par, then a visit to a pukka sidecar specialist is well worth while.”—Nitor

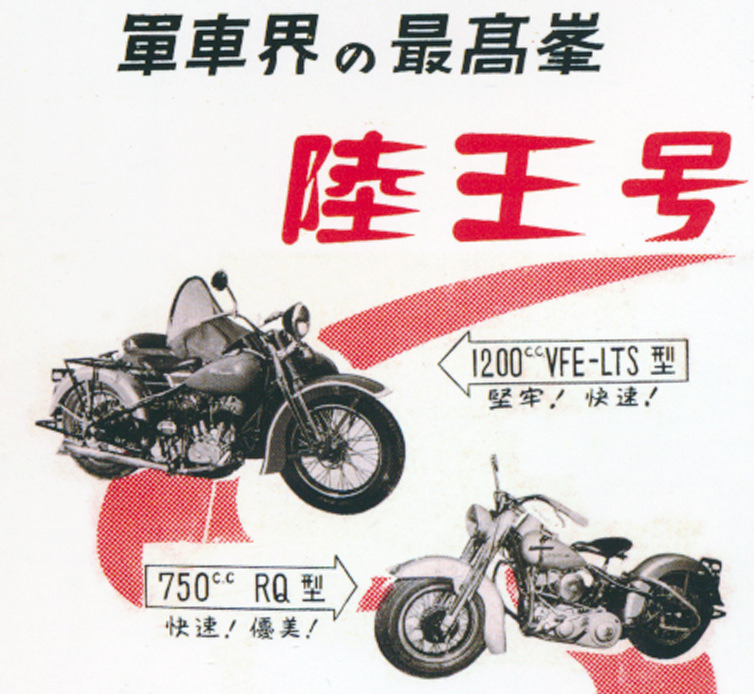

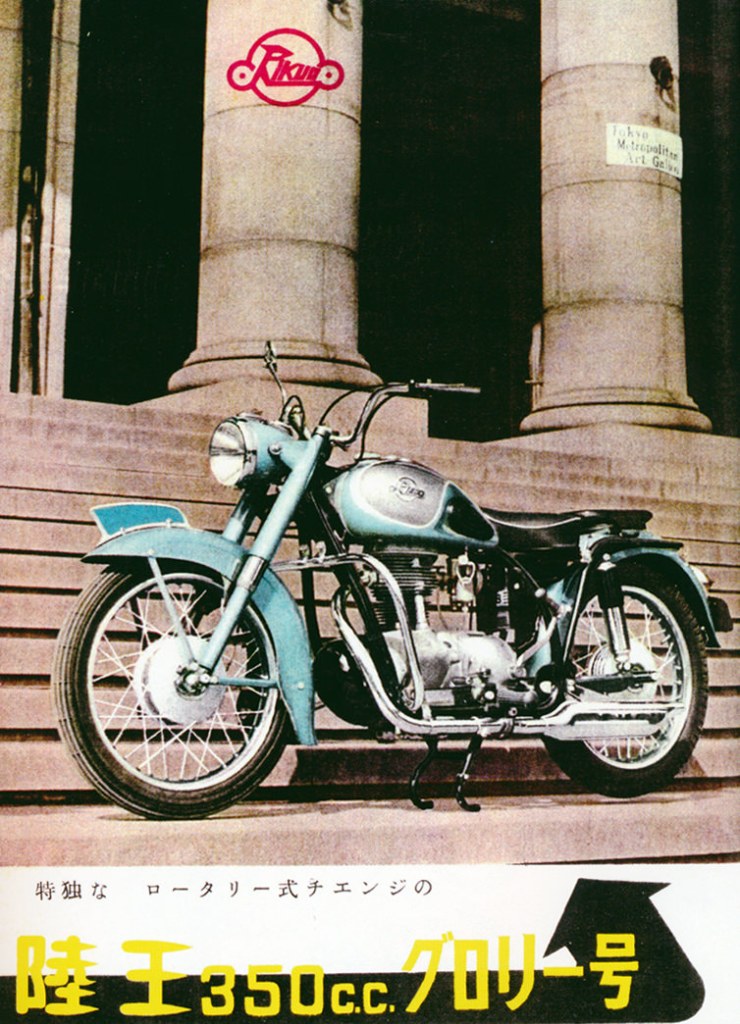

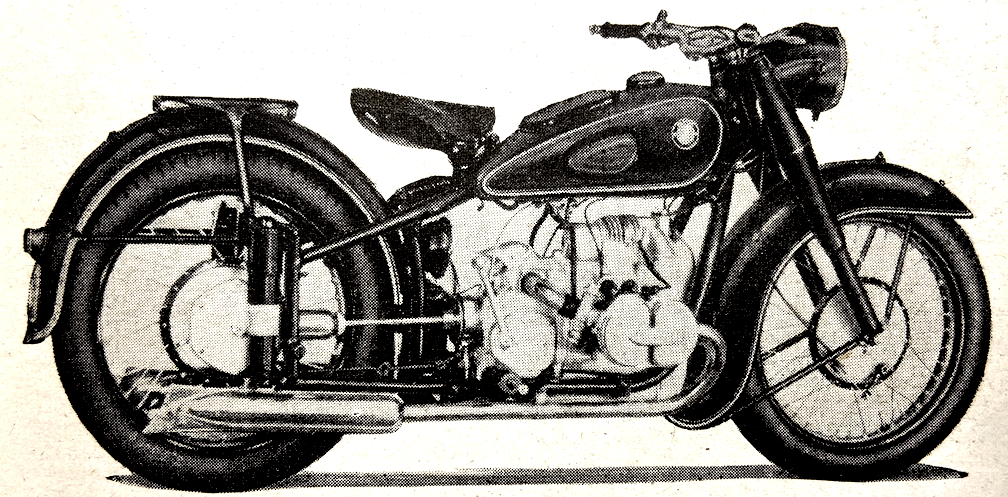

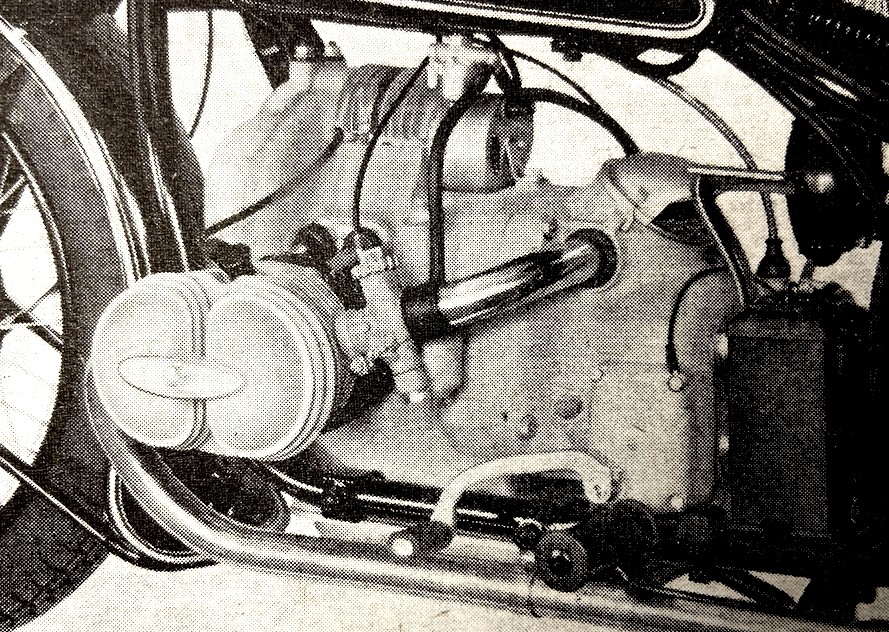

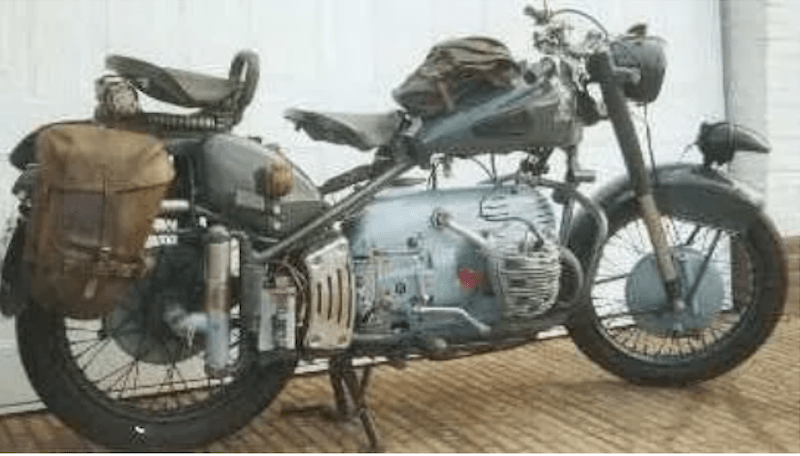

RIKUO INTERNAL COMBUSTION COMPANY, which was producing Harley clones following the Japanese government’s forced buyout of Harley Davidson’s Japanese operation, went to the wall, only to resurface as the Rikuo Motorcycle Co. The big pre-war flat head twins used by the Japanese army as the Type-95, were joined by small one-lungers which was clearly inspired by BMWs and Beezas.

KAWASAKI EXPANDED into motor cycling, initiating devlopement of a 148cc four-stroke engine rated at 4hp.

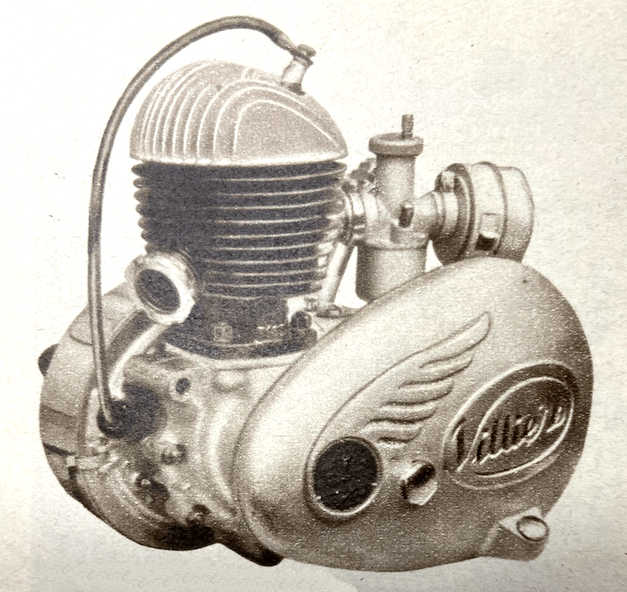

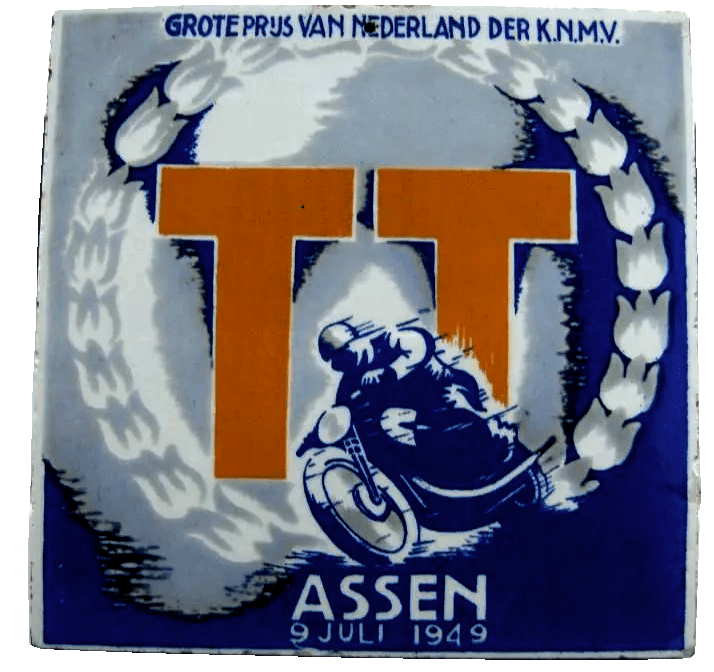

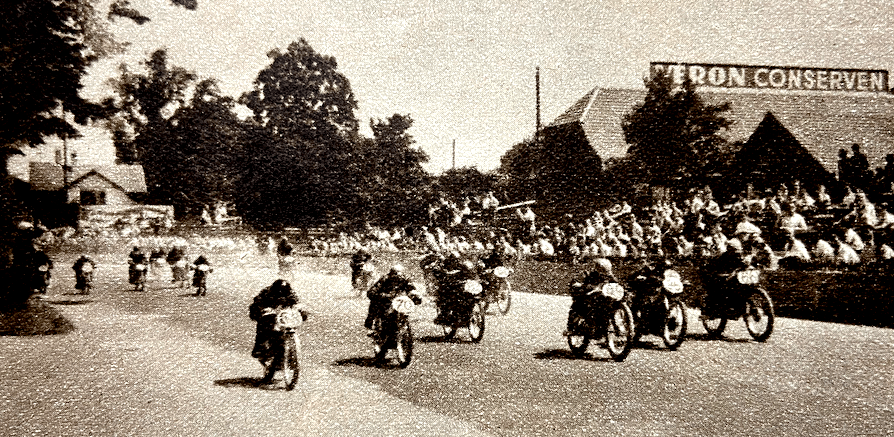

“IT WILL BE RECALLED that at the Autumn Congress of the FICM it was decided to reintroduce the road-racing championships and to scrap the Grand Prix of Europe, which has had no higher status than a name applied to the usual classic races in turn. It now transpires that instead of as pre-war, when the winners in the various classes were called the European champions, the title World’s Champion will be used. It is considered that as an international permit allows entries to be received from any part of the world where the governing body is affiliated to the FICM, the title World’s Champion is justified. Unfortunately, this will not include American riders, because the US motor cycle clubs, controlled as they are by the AMA, are not affiliated to the FICM. The inclusion of the AMA under the banner of the FICM is something that we must hope for; it has been talked about for a long time and nothing would please British sporting motor cyclists more than to have their American cousins rowing in the same boat.”—Nitor The World Motorcycle Road Racing Championships was established with six rounds and classes for 125, 250, 350 and 500cc. The opening round of the new series was the TT, and quite right too.

“ASKED TO NAME the two road improvements that benefit them most, the majority of motor cyclists would refer to the elimination of trams with their tracks and the replacement of wood paving with safer road surfaces. But while many provincial cities have long since discarded their tramway systems and torn up those death traps, the tracks, London has persisted with them, more especially south of the Thames. At long last, there is good news. Lord Latham, chairman of London Transport, stated last Friday that there was now ‘permission to go full-steam ahead’. The conversion from trams to omnibuses is to be a nine-stage project…the total operation should be completed by 1954.”

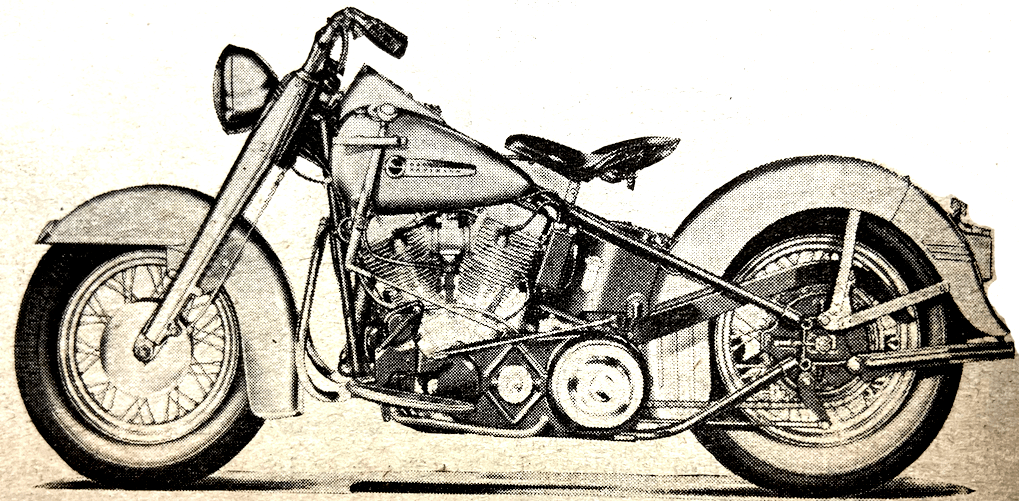

“ANALYSIS OF LETTERS from Canada and the United States reveals a frequent demand for greater machine comfort. The employment of large-section, low-pressure tyres is urged, also the development of more comfortable saddles mounted, American style, on sprung seat pillars. Occasionally a reader on the other side of the Atlantic will mention that swept-back handlebars for fitting to British machines are available from American accessory firms. The last point tends to stress the different outlook on the subject of the best riding position. In Great Britain it is widely held that a motor cyclist should ride his machine—not just sit, with the saddle bearing the vast proportion of his weight. Footrests, it is generally considered, should take some of the weight and the riding position be such that when the machine hits a bump the rider automatically poises on the footrests, the springiness of his legs taking any shock that might otherwise be transmitted to his body. It is an axiom that solid shock on the body, and particularly the spine, soon causes fatigue. Which is preferable—a motor cycle so designed that the man in the saddle rides or merely sits in so-called ‘sit-up-and-beg’ fashion? On the tyre question, many designers maintain that it is ill-advised to employ large, heavy tyres and wheels with their corollary, greater unsprung weight, a far better practice being to have comparatively light wheels and develop still further the front- and rear-wheel springing.”

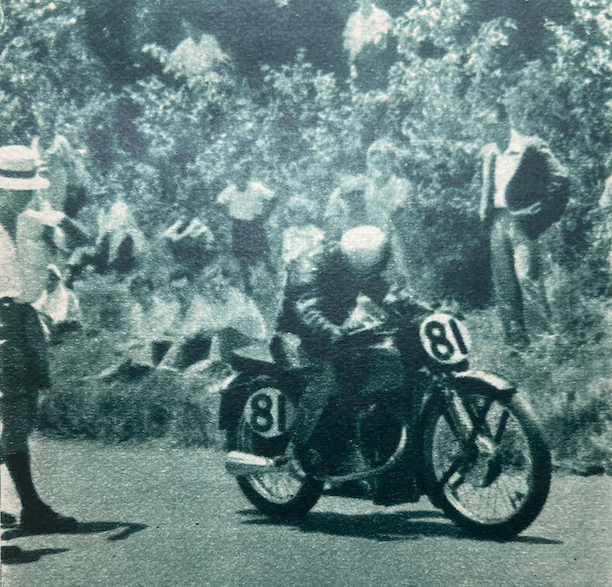

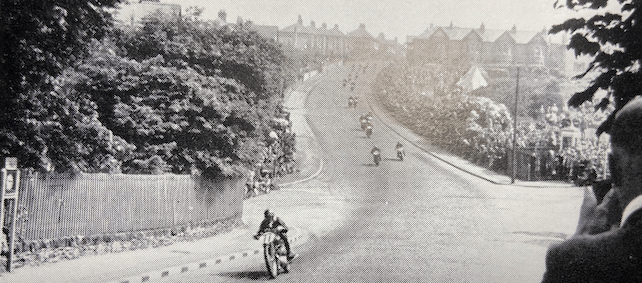

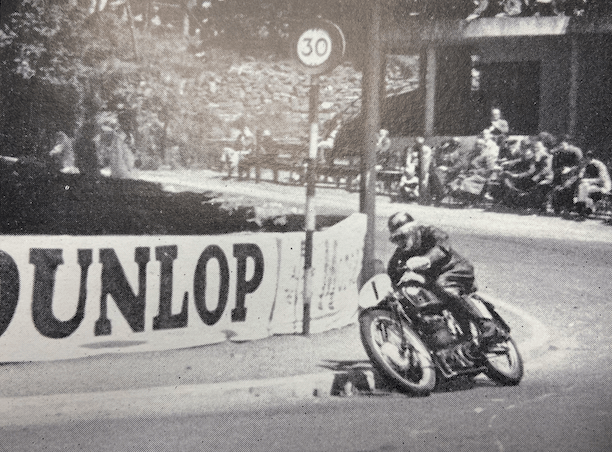

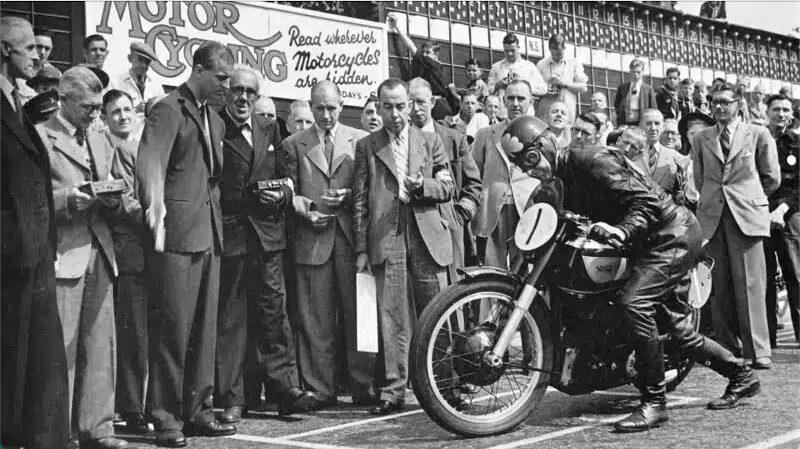

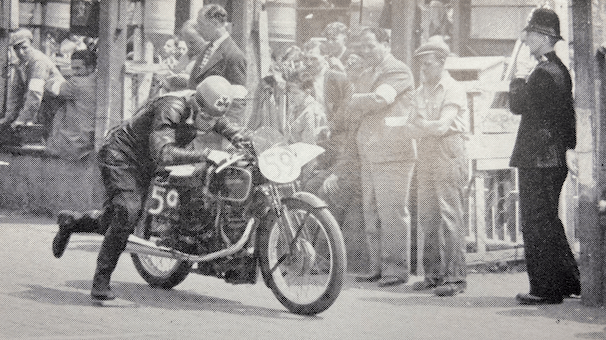

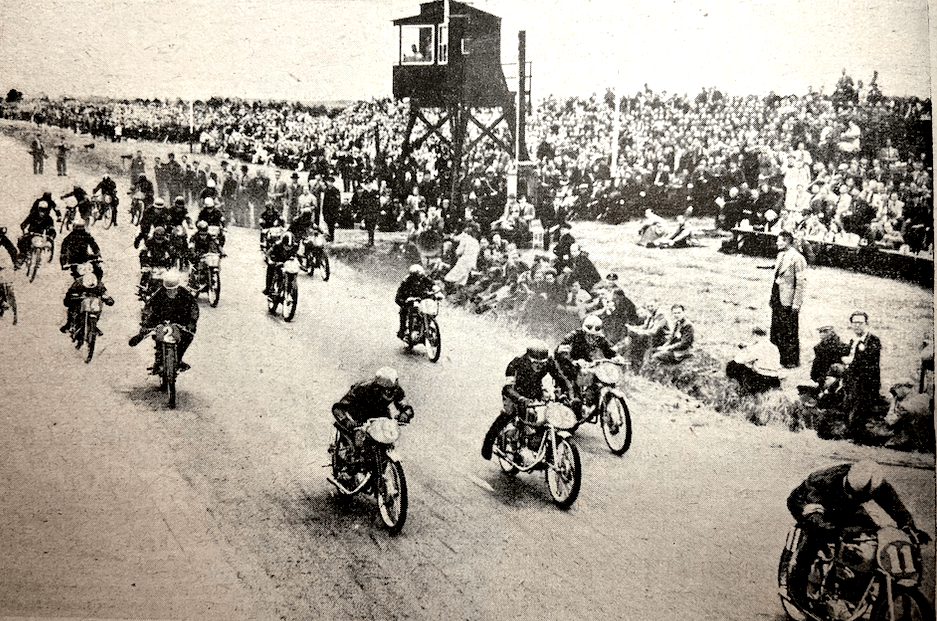

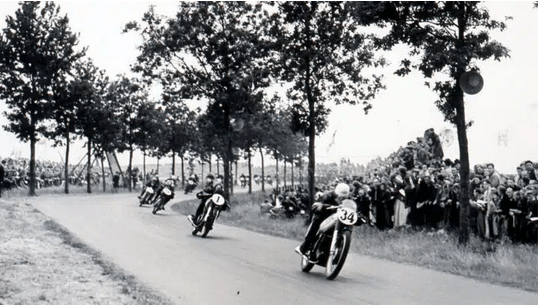

The FIM established the World Motorcycle Road Racing Championships, initially with six rounds and classes for 125, 250, 350 and 500cc. The opening round of the new series was the TT. As always, Geoffrey Davison, editor of the TT Special, was on hand to record the action. Over to you, Geoff:

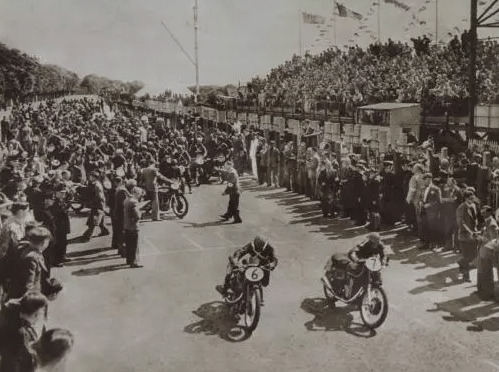

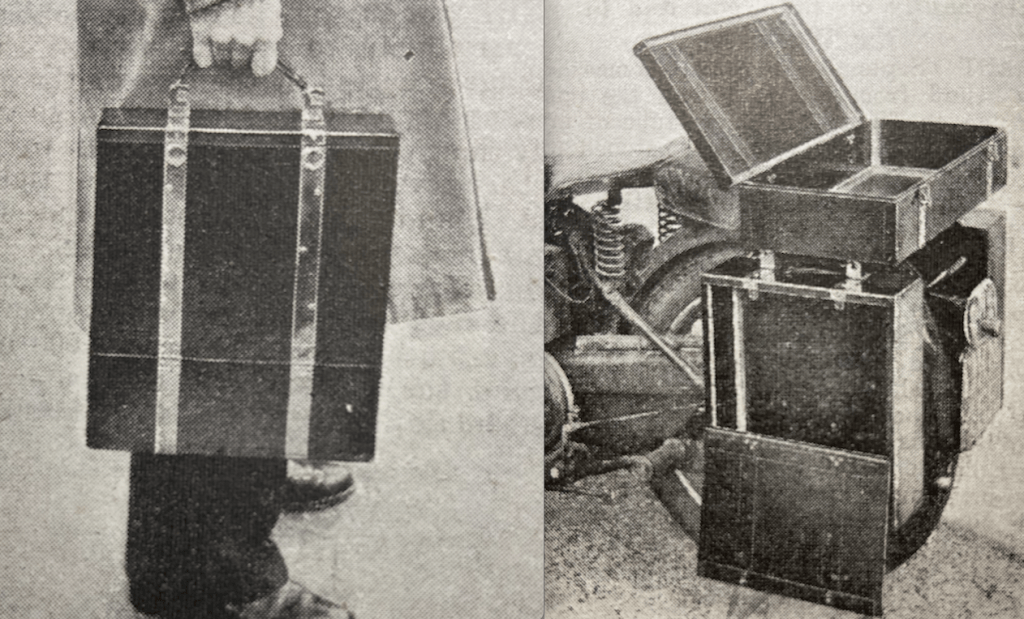

“IN 1948 THERE WAS considerable ‘feeling’ about the Clubman’s TT races. It was urged that more of the boys should be given a chance to have a ride and that 500cc models should not have to compete on equal terms with 1,000s. Much was said and written on these matters and in the winter a meeting was held in Birmingham between officials of the A-CU, prominent personalities from the Isle of Man and a few—a very few—riders. The absence of many of those who had said and written so much was regrettable, but the meeting bore fruit in that for 1949 it was decided that four Clubman’s races should be held, two in the morning and two in the afternoon, with a maximum of 100 competitors in each period—ie, a total of 200 in all as against the 100 of the previous year. The additional race was, of course, for 1,000cc machines. In 1948 the Junior and Senior Clubmen had covered four laps and the Lightweights three, but in 1949, with the two sessions, it was felt that there would not be time for races of this length. The Lightweights, therefore, were required to cover two laps only and the other classes three each…the total entry was 174, made up of 12 in the ‘1,000’ and 85 in the Junior, run concurrently in the morning; with 55 in the Senior and 22 in the Lightweight in the afternoon. The Supplementary Regulations read: ‘Every motorcycle entered for these races shall be a fully-equipped model…according to the manufacturer’s catalogue or a complete published specification, which shall have been published before 24th November, 1948, and a copy of such catalogue or specification shall have been deposited with the A-CU nor later than the 1st March, 1949. At least 50 of each model entered shall have been produced by the manufacturer and sold and delivered to the general public in the United Kingdom before the closing date of entries. No motorcycle manufactured before the 1st September, 1937 shall be eligible. The standard equipment of every motorcycle entered for these races must include dynamo, electric lighting, kickstarter, silencer(s) and fully enclosed primary drive except in the cases of motorcycles having external flywheel(s) or where

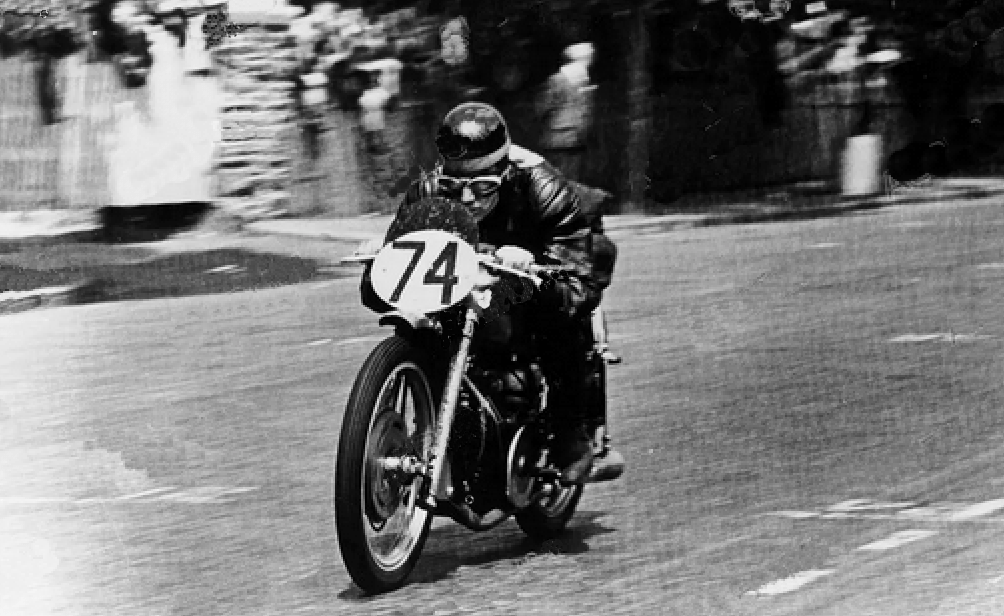

the primary drive is taken from between its crankcases.’ Broadly speaking, therefore, competing machines had to be ‘the same as you can buy’. It was compulsory for lamps, dynamos, accumulators, stands, registration plates and licence holders to be removed, whilst other things such as air cleaners, silencers, speedometer heads, luggage carriers and tool boxes might be removed. ‘Permitted additions to equipment’ included flyscreens, engine revolution counters, steering dampers, security bolts, rear springing, air vents and water excluders to brakes and mudguard pads, and there were 17 ‘optional modifications to equipment’, including any make or type of sparking plug, brake and clutch lining, flexible oil and petrol pipes and any desired alteration to valve and ignition settings, compression and gear ratios. Boiled down, the whole thing meant that machines had to be ‘bought off the peg’ non-racing models with modifications which could be carried out by the ordinary rider. Racing machines such as the 7R AJS, the Manx Norton and the KTT Velocette were barred. THE CLUBMAN’S ‘1,000’ had 10 starters only. Of these, C Howkins rode an Ariel Square Four, all the remainder being on Vincent HRDs. The curious feature about this race was that whereas in 1948, when 500s and I,000s were run in one event, the first 500 to finish—CA Stevens (Norton)—was third at a speed of 4½mph slower than the winner, in 1949 the winning Senior was over 6mph faster than the winning 1,000, while no few than nine Senior riders were faster than the second 1,000! The reason for this, probably, was the regulation which prohibited refuelling. In 1948, every competitor had to make a compulsory stop at the end of the second lap and could take in petrol if he desired. In 1949, however, with one less lap to do, no replenishments were permitted and the tanks of the Vincent HRDs were too small to allow their riders to go full bore for the three laps, or even in fact, to use the desired jet sizes. Two of the Vincent riders had covered three laps in practice, but only on such lean mixtures that the engines tended to overheat. The event was, therefore, more of a petrol consumption test than a race, which was unfortunate. It seems somewhat paradoxical that the regulations should insist that riders should cover the race on a tankful, but should at the same time prevent them from fitting larger or spare tanks to enable them to do so. However, there it was. In perfect weather—indeed the weather was perfect for each of the seven 1949 TT Races—the 10 Clubmen set off, kick-starting in pairs at 20sec intervals. Contrary to expectations, George Brown, the 1948 lap record holder, did not net the

pace, being content to be second on the first lap, 22sec behind C Horn; G Manning, A Philips, J Harding and DG Lashmar, all on Vincent HRDs, completed the first six. In the second lap Horn put in a time of 26min 28sec (85.57mph) which was actually the fastest of the day and 56sec better than Brown’s record of the previous year. George himself had struck trouble and had dropped back to 6th place, Lashmar having picked up to second. Manning, Phillip and Harding had all disappeared from the Leader Board. In the third and last lap Horn paid the penalty for his early high speed he retired—out of petrol—at Glentrammon between Sulby and Ramsey; Lashmar went on to win with Wright and Wilson second and third. Charles Hawkins, 48-year-old rider of the Squariel, was fourth and George Brown, finishing on one cylinder, came in fifth at 49.67mph.—a fraction of a mile an hour slower than the speed at which I completed five laps on a machine of a quarter the size twenty-seven years ago! Yes, the Clubman’s ‘1,000’ was rather a farce. THE JUNIOR CLUBMAN’S. Two minutes after the last of the 1,000s had left, the first Junior Clubman—G Milner (BSA)—was away. Actually, he went off alone for he was paired with No 13 which, in a TT Race, is never drawn. After Milner had gone they were despatched in couples at 20-sec intervals… Whereas in the International Junior TT only three makes were represented—AJS, Norton and Velocette—in the Clubman’s event there were no fewer than eight makes. The 74 starters were headed by 21 BSAs. There were 15 Nortons, 13 AJSs and single-figure numbers of Douglas, Enfields, Matchless, Triumphs and Velocettes…In practice the fastest lap had been made by Alan Taylor (Norton), 19-year-old student, of Oldham, Lancs. The event was Taylor’s first race or competition of any sort but nevertheless his best practice lap of 30min 42sec equalled the record lap put up in the race last year by Pratt on a similar machine. Next best was Harold Clark (BSA), just 2sec behind Taylor, and third was Ray Hallet—also BSA—in 31min 11sec. It looked as if the race would lie between these three and on the first lap Taylor led

the field with a time of 30min 26sec, Haller and Clark being bracketed second in 30min 34sec. In the second lap Clark increased his speed, completed the circuit in 29min 52sec—which proved to be the record for the race—and came into the lead 24sec ahead of E Harvey on another BSA, who had been lying 6th. Taylor had dropped back to third place just one second behind Harvey and John Sinister of Macclesfield on another Norton was 5sec behind him. Haller with a relatively slow lap, had dropped back to 5th. Harvey’s challenge was short-lived, however, for at Handley’s Corner on the last lap he retired with a broken chain. Taylor’s third lap took 30min 53sec—both his second and third circuits were slower than his first one from a standing start—whilst Simister put in a last lap of 30min 15sec and slipped into 2nd place, 50sec behind Clark, who won at 75.18mph. Fifty-eight riders finished the race—over 78% of the starters—and 57 of them were home whilst poor George Brown was still plodding around on his single-cylinder Vincent. THE CLUBMAN’S LIGHTWEIGHT. Like the 1,000cc event, the Clubman’s Lightweight was almost in the nature of a fiasco. This was not because of any lack of entries—there were 17 starters as against 15 I948—but because the event was so extremely short. At Ansty, Haddenham and other short-circuit meetings a 75-mile race would be a long event, but when one is accustomed to thinking in terms of 264 miles, it becomes so short as to be almost negligible. In fact, most of the riders had covered the distance of the race each day in practice. The afternoon session began with the Senior event, the Lightweights following two minutes after the last 500 had gone. This meant, of course, that all the faster machines, who had three laps to do, were out of the way before the 250s set off on their little race. The 17

riders were mounted on a mixed bag of Excelsiors, Triumphs and Velocettes, with one solitary BSA. Forty-six-year-old Cyril Taft—’nine children, never a dull moment!’—took the lead on his Excelsior at the end of the first lap, which he covered at 67.5mph in 33min 33sec, over half-a-minute faster than the previous year’s record. BJ Hargreaves and DA Ritchie (Velocettes) were 2nd and 3rd and GS Wakefield (Triumph) 4th; 14 of the 17 starters completed the lap. Almost forgotten in the excitement of the Senior race, the 14 went off on their second and last lap and 13 of them finished it, the only change among the four leaders being that Ritchie overtook Hargreaves and finished 40sec behind Taft, who put up a new record lap in 32min 57sec (68.7mph) and won The Handley Trophy at 68.1mph. THE CLUBMAN’S SENIOR. There were 44 starters in the Senior event—batches of BSAs, Norton and Triumphs, with one AJS, one Ariel and one Vincent HRD. Allan Jefferies and Tom Crebbin (Triumphs) and Geoff Duke (Norton) were the favourites for the race and true to form at the end of Lap 1 they occupied the first three positions, Geoff Duke leading Allan by 29sec, with Allan three-quarters of a minute ahead of Tom. Geoff’s firs lap from a standing start took 27min 32sec—only 8sec outside the 1948 record lap, established on a 1,000cc machine. The second lap saw no change amongst the riders, but there were wider spaces between them. Geoff had put in a time of 27min 3sec (83.7mph), handsomely beating the existing record. Leo Starr

(Triumph) had moved up from 5th place on the 1st lap to fourth on the 2nd, so a Norton was leading with three Triumphs well and truly after it. They were no match, however, for the imperturbable Duke, who went on riding magnificently to win by over 2min, his last lap in 27min 18sec also being well inside the 1948 record. Allan Jeffries went on untroubled into 2nd place, but Crebbin came off at the Guthrie Memorial, 10 miles from home and although able to continue, dropped back to 5th. Leo Starr (Triumph) was 3rd, over 5min behind Jefferies and Phil Carter (Norton) was fourth, half-a-minute behind Starr. The Junior race was, of course, run by itself as usual, on Monday, 13th June, the Senior and Lightweight being run concurrently on the following Friday. The Regulation went on to read: “Should it be necessary to reduce the number of entries…Priority of acceptance of entries will be in the order, (a) From entrants from overseas, who are in receipt of financial aid from the A-CU…(b) From manufacturers of motorcycles, limited in each case to six of each proprietary make of motorcycle. (c) From entrants or drivers who have been awarded a TT replica in any International TT Race since 1945. (d) From other entrants…THE JUNIOR TT. The 100 machines were all British—AJS 42, Norton 26 and Velocette 32. The only foreign element that was seen in the Junior Race was during the practice period, when Enrico Lorenzetti turned out on a 350 Guzzi. There was, however, no question of him riding in the race itself, for the machine had not been

entered and the regulations definitely prohibited any change in the make of a machine after the closing date of entries…There was a strong wind, but it was northerly and therefore helped on the mountain climb—just the opposite to 1948 when a strong southerly wind upset the calculations of many riders. It was an extremely open race with any one of ten men a possible winner…For the first time in the history of the International Races, since riders were despatched from St Johns on the old, short course in couples, a ‘pair start’ was used…Freddie Frith, winner of the 1948 Junior, was therefore despatched alone, the others following in pairs behind him…First lap saw Les Graham (AJS) in front. From a standing start he lapped in 27min 1sec—27sec and over a mile an hour faster than the post-war lap record of 27min 28sec—and this terrific opening circuit gave him a lead of 19sec on the next man, team-mate Bill Doran. Fred was third in 27min 24sec and close behind him were the three works Nortons—Daniell (27min 29sec), Bell (27min 33sec) and Lockett (27min 34sec). Les Graham, however, was in trouble early in the second lap. He stopped at Ballacraine to adjust his clutch and retired soon afterwards. Bill Doran then came to the front and with a second lap in 26min 55sec—his fastest of the day so far, and a post-war record—led Fred Frith by 16sec, as against 4sec on the first circuit. Artie Bell slipped past Harold Daniell into 3rd place and Ernie

Lyons (Velocette) also passed Harold and ran 4th, whilst Bob Foster (Velocette) picked up to 6th. An AJS first, Velocettes second, fourth and sixth and Norton third and fifth On the third lap, Bill and Fred each took 27min 4sec so there were still 16 seconds between them and both had drawn away from Artie Bell and the others. But on the fourth lap—which included a it stop for each, Fred was 8sec quicker than Bill, so only 8sec behind him. For the 5th and 6th laps there was no change in the placings, except that Lyonsslipped into 3rd place ahead of Bell. On the fifth Bill was 12sec ahead of Fred and on the 6th 11sec, with Lyons 20sec behind Fred. The only manufacturers team left in the race was the Norton, Bell 4th, Daniel 5th and Lockett 7th. On the 7th and last lap Fred really gave it the gun and lapped in 26min 53sec, 2sec faster than Bill Doran’s earlier record. Fred was 8min ahead of Bill on the roads, and stop watches on their indicators at Ramsey showed just eight minutes between them. Fred flashed past the finish before Doran was recorded at the Mountain Box, but that was only to be expected for the stretch from the Mountain Box to the finish was taking them less than 7min. The seven minutes came, however, and the six—and there was no sign of Bill Doran; and then came the news that he had retired at the Gooseneck with gear trouble. So Fred won his third Junior and his fourth TT race, and Velocettes came second too, with Ernie Lyons. Artie Bell, as last year, was third and Harold Daniel fourth, less than four seconds separating the Norton pair. Reg Armstrong, who had gradually been increasing his speed, overtook Foster and drew into 5th place. A gloom was cast over the race by the death of Ben Drinkwater, as the result of a crash at