“THE BASIC FUEL RATION represented 267 million gallons a year. Allowing for the increase in supplementary allowances, the ministry of fuel estimated in November that the net saving will be about 240 million gallons. There is every reason to believe that applications for supplementary have exceeded all expectations. It is thought that when figures can be obtained it will be found that the actual saving of fuel to set against the disruption and discontent caused by the withdrawal of ‘basic’ will be far, far less than the estimates. Let us suppose that the figure is around 200 million. Could that supply of petrol or its equivalent be obtained on an economic basis by encouraging home produced fuel? First thought to come to mind is benzole, produced by the extracting plants at gasworks. In 1946 the output was 87 million gallons, most of which found its way into our pool petrol. How far can this figure be improved upon? Well, the peak was 1943 when 103 million gallons were produced. The gas companies would be only two glad to produce more benzole. It is a by-product in the extraction of gas from coal and in the process they would have more gas, which is what industry and private consumers want. But that means more coal and more special equipment in the gas works—both are scarce. How about the hydrogenation process? First use successfully in Britain in the ’30s, good fuel is produced but unfortunately the process uses a lot of cold and, even whe gn developed to the stage achieved by the germans during the war, the method results in fuel considerably more expensive than petrol from natural oils. Two possibilities hold out at least some hope. The first is that many of the small gas companies do not extract benzole when producing gas because the installation of the plants has not been considered a worthwhile proposition. Whether our present economic position would warrant a change in policy (assuming the plant could be obtained) remains to be seen. The second is alcohol from bread baking…which seems to offer possibilities if tackled and energetically. Nevertheless…we have a long way to go before we could look to home produced fuel to ease our problems.” [Making our own fuel from our own coal…developing bio-fuels…best not to think about it—Ed.]

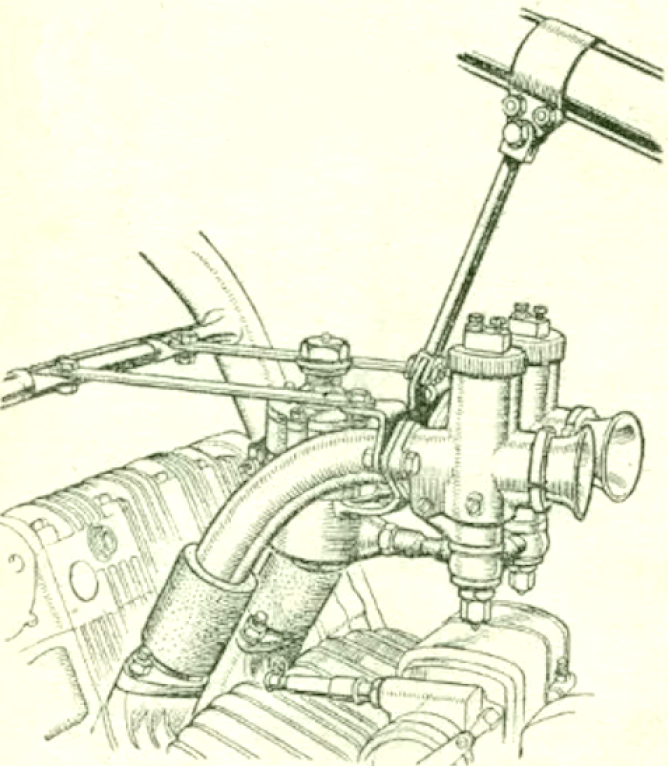

“IN ARTICLES WHICH appear in last week’s and in this issue, practical advice is given on how to obtain more miles per gallon. Figures produced after careful tests on the road with a standard type of twin-cylinder machine show that it is possible to vary the petrol consumption from 75.8mpg to over 150mpg. Extreme though these figures are, they do show in striking fashion that careful maintenance, carburettor adjustments and thoughtful driving can produce an impressive increase in the miles per gallon performance; and in these days of a minute petrol ration the accent is obviously on mpg.”

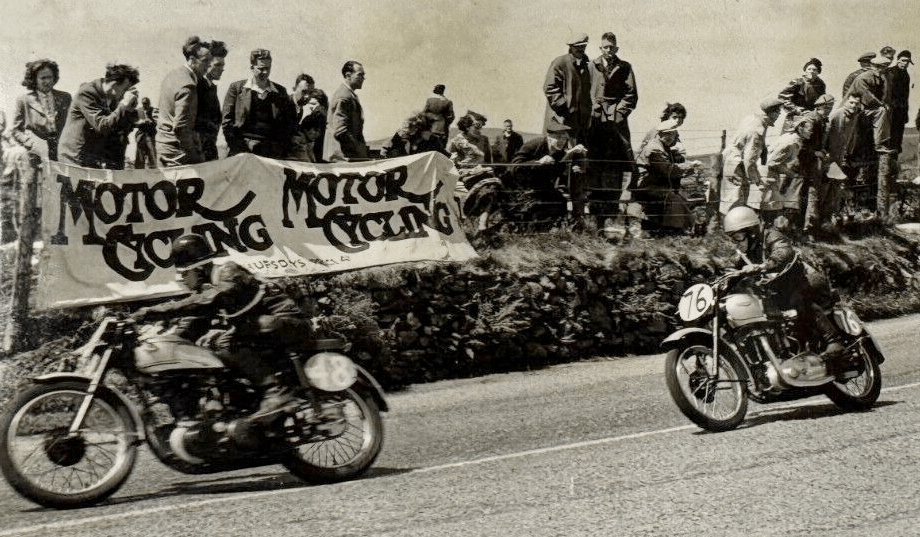

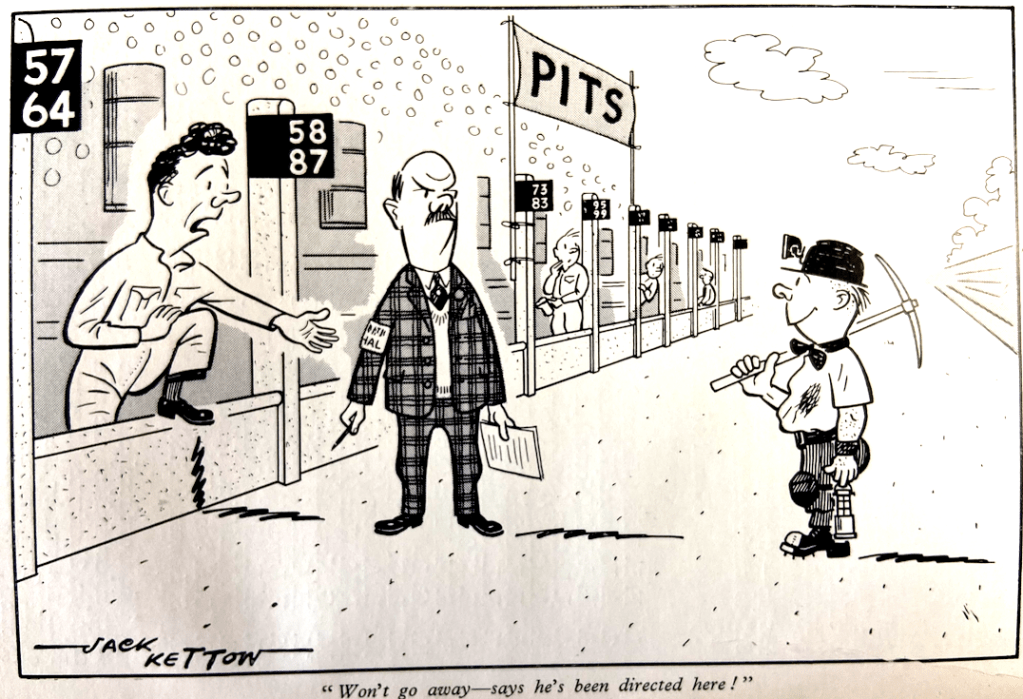

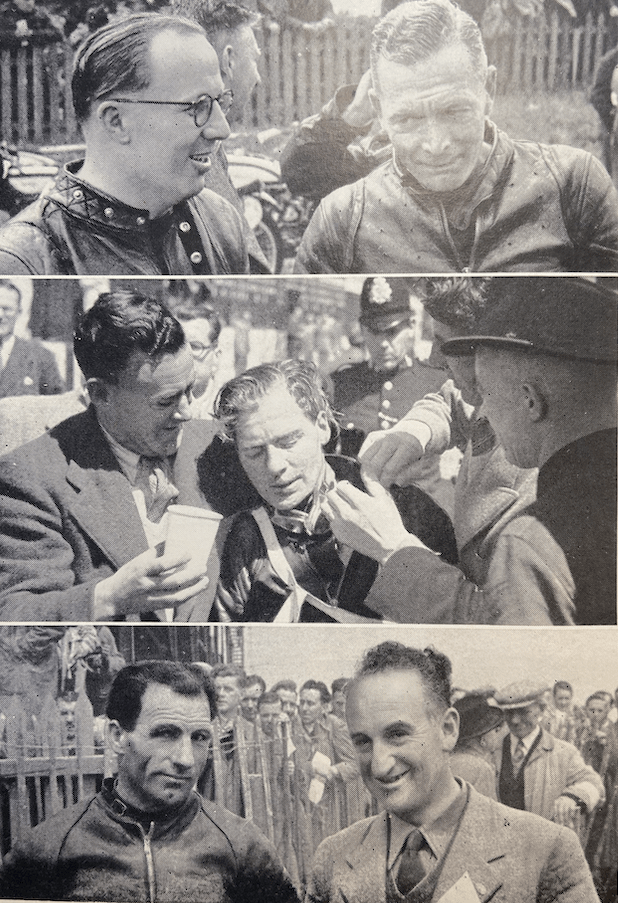

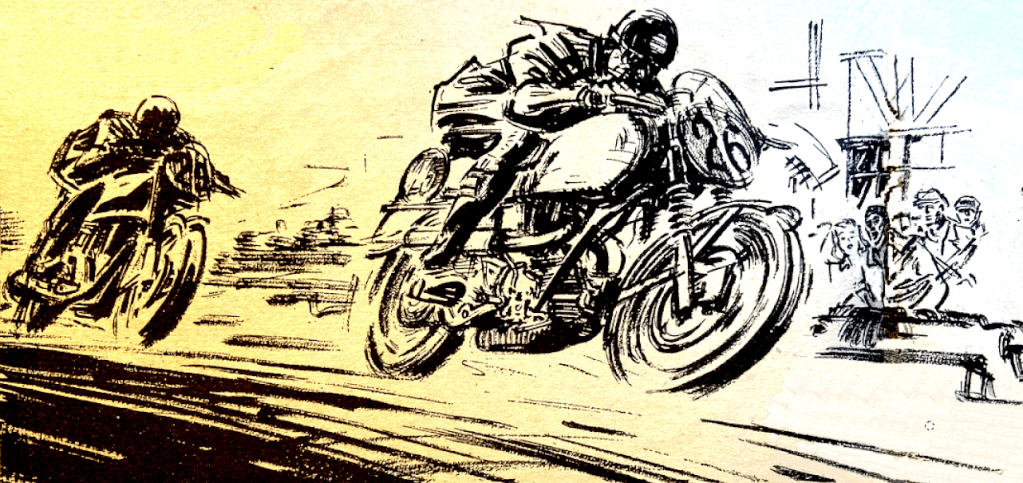

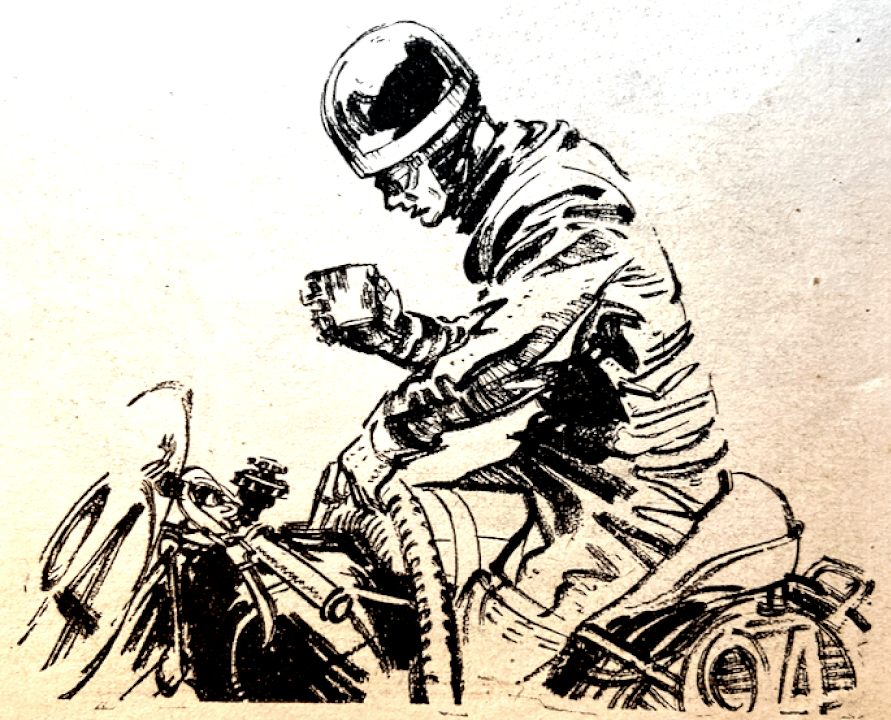

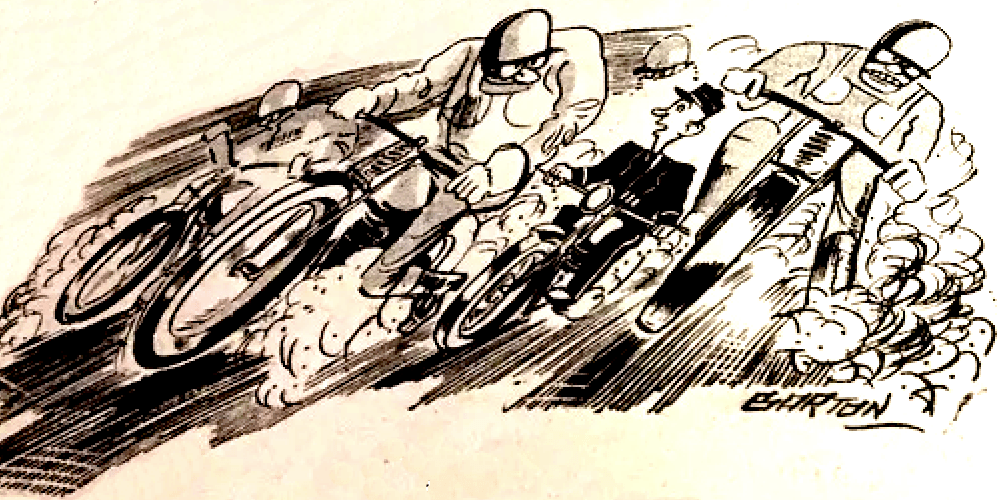

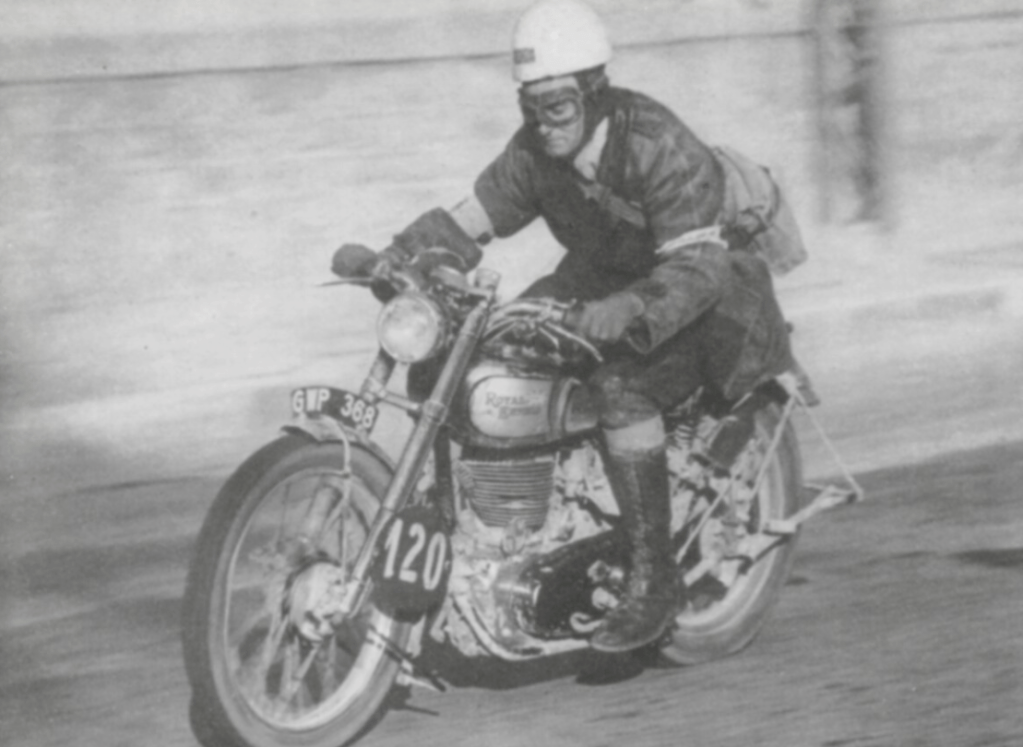

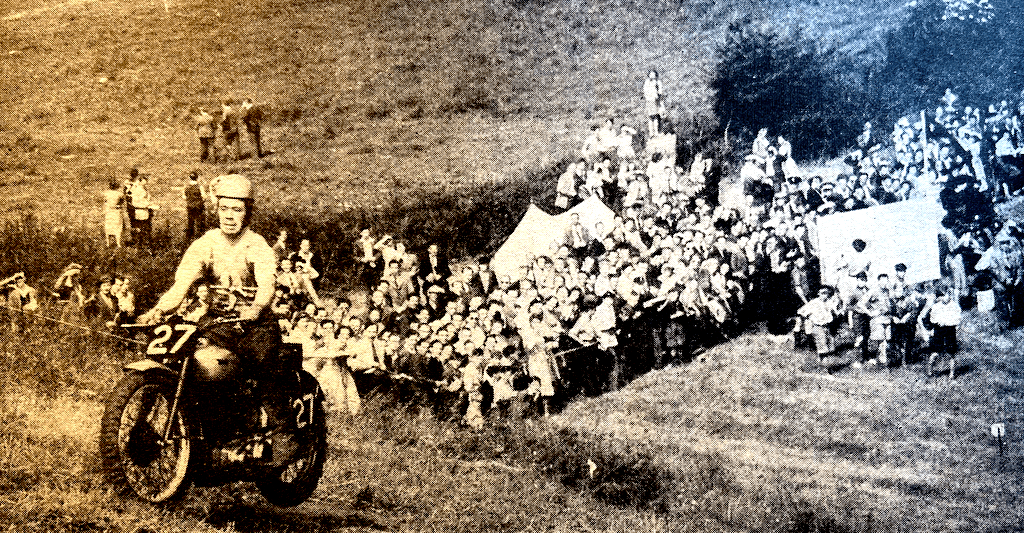

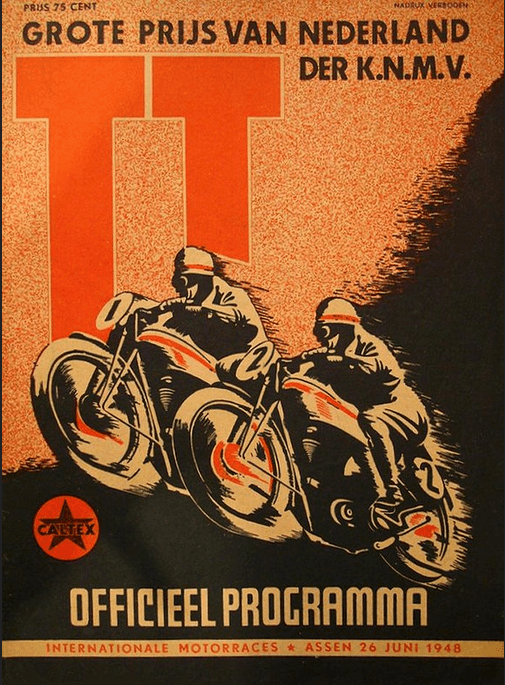

GEOFFREY DAVISON, EDITOR OF the TT Special, was uniquely placed to record the action at the 1948 TT; his passion shines through. Over to you, Mr Davison: “The most notable thing about the 1948 TT Races was the vast number of entries which was received by the Auto-Cycle Union. In 1936, full ebb of the TT tide, there was a total of 85 only; 12 years later over 400 persons over 18 years of age and of the male sex (vide Regulation No 19) wanted to have a go, not to mention a few of the female sex who weren’t eligible anyway. The A-CU decided that this would be too much of a good thing, and restricted entries to 100 on each day’s racing, ie, 100 for the Junior on Monday, 7th June, 100 for the three Clubman’s events on Wednesday, 9th June, and 100 for the concurrently-run Senior and Lightweight on Friday, 11th June. There was much disappointment and much grousing ; many chaps got hot under the collar and many more got up and said things at meetings. And whilst, as in almost every case of disagreement the world

over, there was something to be said on both sides, there was one little regulation which most of the malcontents seemed to have missed. This was Regulation No 7, brief and to the point; as follows: ‘Refusal of Entries: The A-CU reserves the right to refuse any entrant or driver or any team nomination without assigning any reason.’ So there they all were—and that was that. Twelve practice periods were allotted—one more than in 1947—of which eight were for the Internationals and four for the Clubmen. Eight of the periods were in the early morning—4.45am—and four in the evening—6.30pm. Practising for the Clubman’s races was confined to the second week. Their first period was on the evening of Monday, 31st May, the other three being on the mornings of the following Tuesday, Thursday and Friday. The Internationals began practising on the morning of Thursday, 27th May, and had in all five morning and three evening periods. And now to the races themselves. I will begin with the three Clubman’s, continue with the Junior and Lightweight, and end with the piece de resistance of the week, the mighty Senior. The 100 Clubman’s entries were composed of 16 in the Lightweight, 40 in the Junior and 44 in the Senior…In 1947 any rider who was not actually competing in the 1947 International TT was eligible. In 1948, however, any rider who had gained a replica in any International TT, or who had finished in the first three in any

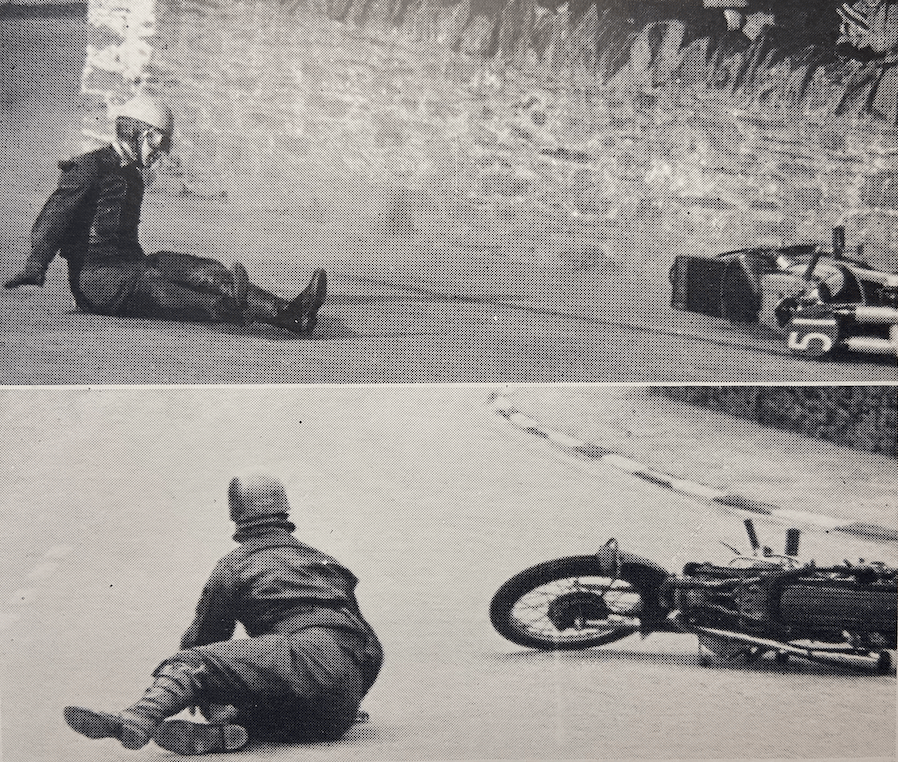

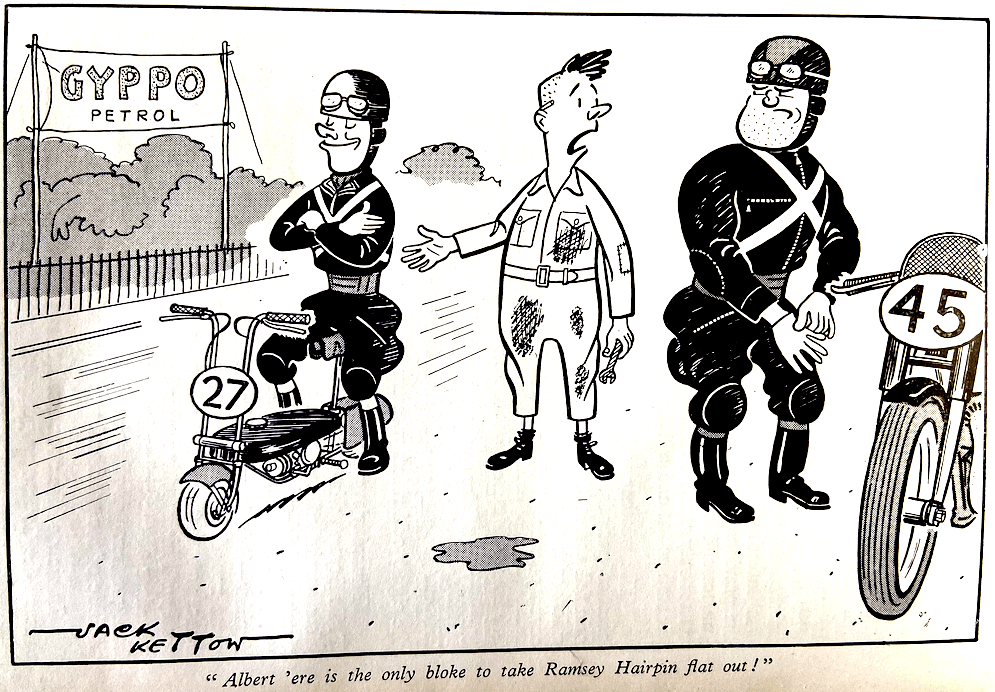

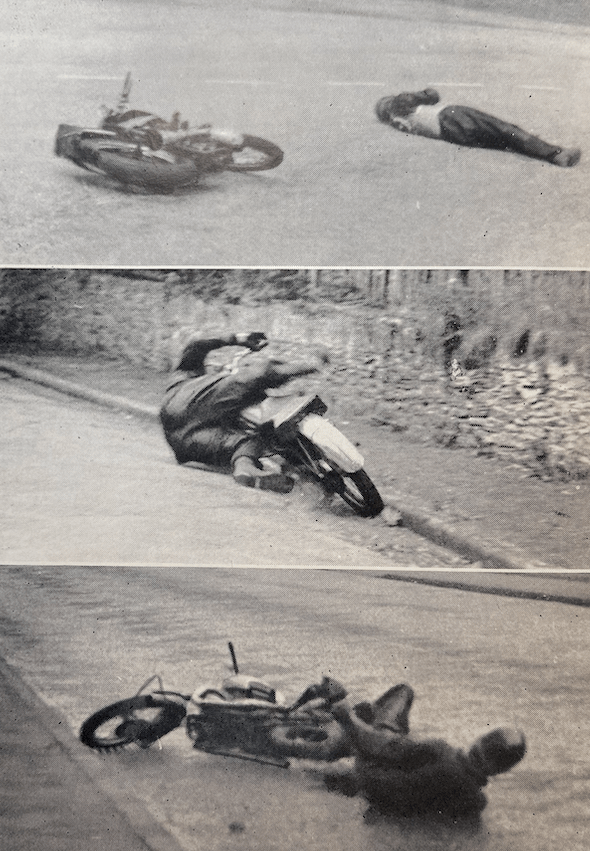

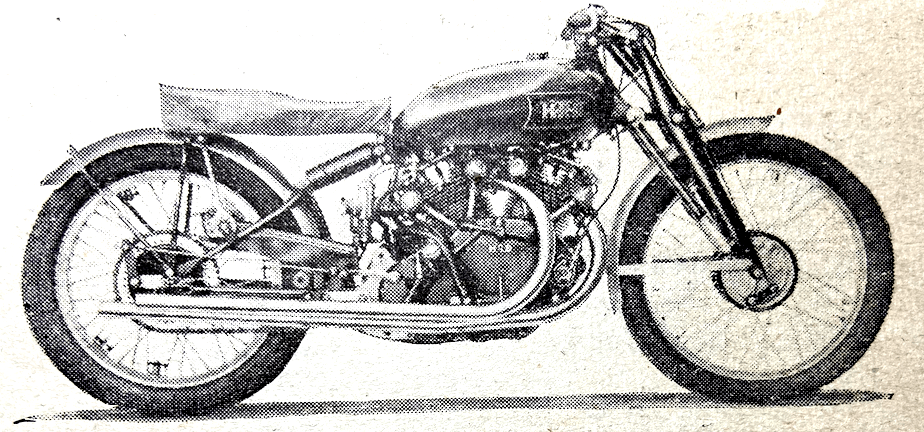

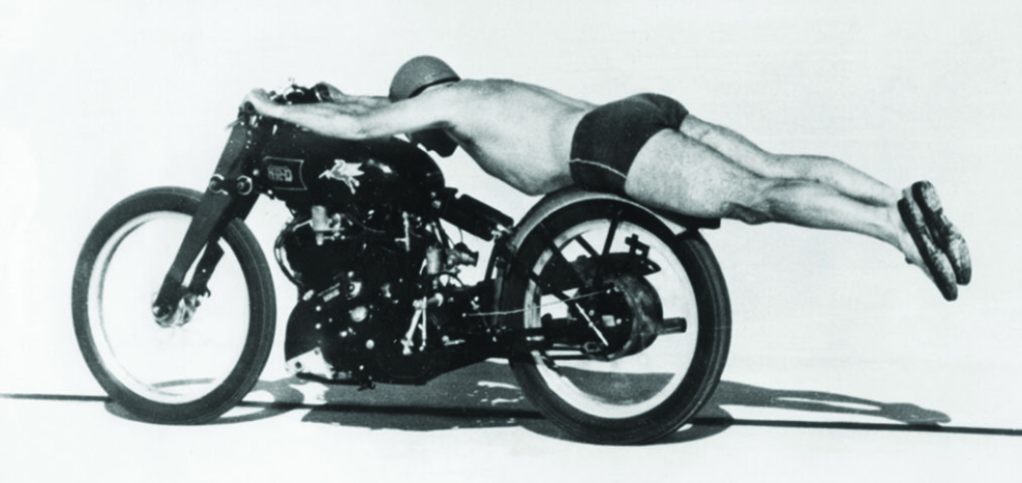

post-war Manx Grand Prix, was barred. The races were over the some number of laps as the previous year—three for the Lightweights and four for the Juniors and Seniors—and machines had to be started by kick-starter only at the beginning of the race and after the compulsory pit stop at the end of Lap 2. The weather was none too good for the four Clubman’s practice periods. On the first—and only—evening, torrential rain fell and it is safe to say that every one of the 79 riders who turned out was drenched to the skin. Nevertheless, 77 of them faced the starter in the rain again next morning—less than eight hours after they had returned from the previous evening’s soaking. Two days later, in clear but blustery conditions, there were 103 on the roads (including reserves), and on the last period the following morning—best weather of all—130 laps or nearly 5,000 miles were covered by the 80 odd riders who turned out. Thursday’s practice was marred by a fatal accident to TR Bryant, who crashed at Brandish Corner and died shortly after admission to Noble’s Hospital. I saw the crash myself through field-glasses from Hilberry, and wrote at the time ‘…a nasty crash visible at Brandish Corner in the distance. A rider—later known to be T Bryant (Lightweight Velocette)—came round fast and wide, apparently touched the right-hand bank, was thrown, and rolled and rolled and rolled down the road with his machine after him. Luckily, he and his bike were just clear of the riding line and a batch of five or six following him got through without incident. Bryant was then drawn to the side of the road and was later taken to Noble’s Hospital.’ In view of the poor weather and the consequent lack of time to learn the Course properly, no spectacular speeds were put up in practice. In the Senior class the best lap was made by Phil Heath (Vincent HRD ‘1,000’) in

30min 7sec, but Allan Jefferies, on a Triumph of half the size, lapped in 30min 20sec. R Pennycook (Norton) was the best Junior, in 32min 42sec and F Fletcher (Excelsior) the best Lightweight in 36min 26sec. All were well outside the Clubman’s record laps of the previous year. The Lightweight race, for which the Wal Handley Trophy was the Premier award, was the first of the three Clubman’s events. Of the 16 entries there was only one non-starter—poor Bryant. As in the other races, competitors were sent off in pairs, at 20 second intervals, starting necessarily being by means of the kick-starter. M Lockwood (Excelsior), whose best practice lap had taken 37min 6sec, surprised everyone by leading on the first lap with a time of 34min 45sec. JJ McVeigh (Triumph) was second in 35min 2sec and F Fletcher (Excelsior) third in 35min 23sec. Lockwood maintained his lead on Lap 2, but the four men behind him slowed down and WG Dehany (Excelsior), who had been 6th on the first lap, drew up into second place over two minutes behind the leader, R Carvill (Triumph) being 3rd. In this order they continued to the end of the 3rd—and last—lap. Only eight of the 15 starters completed the 113 miles. Result: 1, M Lockwood (Excelsior), 64.93mph; 2, WG Dehany (Excelsior); 3, R Carvill (Triumph); 4, AG Crighton (Velocette); 5, J Smith (Velocette); 6, EF Cope (Velocette); 7, HJ Downing (Velocette); 8, A Henthorn (Velocette). The Junior race, which started two minutes after the last Lightweight competitor had got away, was a very different

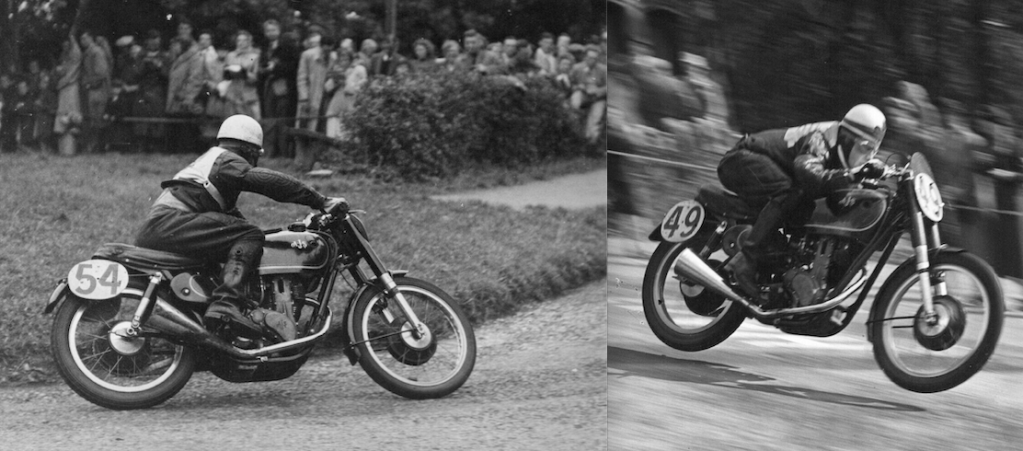

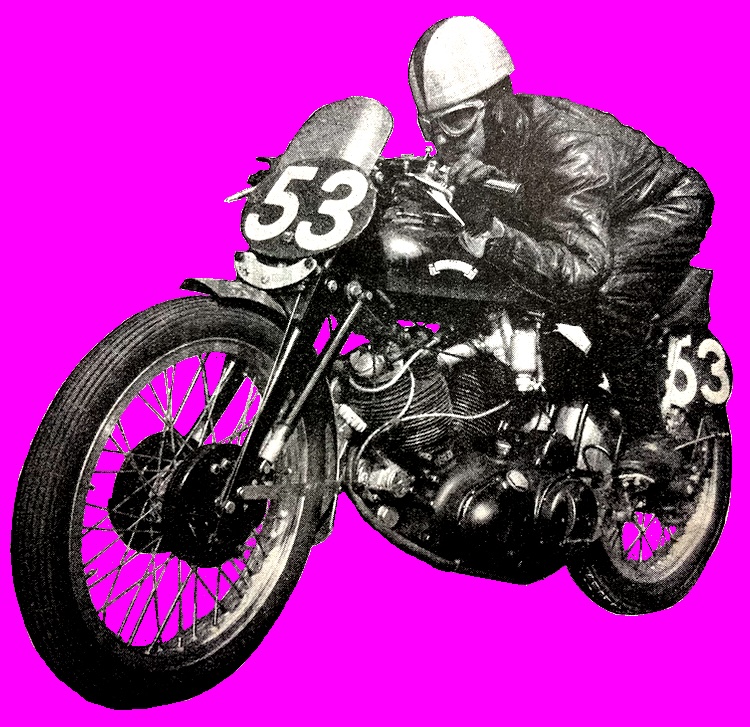

affair. There were five non-starters, out of the field of 40, and the event was obviously an extremely open one. On the whole the 350s responded well to their kick-starters, though not so well, perhaps, as the smaller machines. At the outset it looked as if it were to be a Norton-AJS battle, for at the end of the first lap Norton were 1st, 3rd and 6th, with Ajays 2nd and 5th, a BSA in the hands of J Difazio running 4th. R Pratt, second in the 1947 Junior Clubman’s, led the field with a lap in 31min 43sec—59sec better than the best practice lap, but 40sec outside Denis Parkinson’s fastest of the year before. W. Sleightholme (AJS) was only two seconds longer than Pratt with M Sunderland, on another Norton, 10 seconds behind him. There was not a Velocette amongst the first six—but many things were to happen in this race of surprises. On the second lap, Pratt increased his lead to 21sec over Sunderland, who had beaten Sleightholme into 2nd place. Pratt’s lap time, incidentally, was 30min 42sec, just 21sec faster than Parkinson’s 1947 record, and actually the fastest of the race. Difazio packed up at Hilberry, allowing the 5th and 6th men to move up one, and RJ Hazlehurst brought his Velocette into 6th place. Having run into 3rd place, Sleightholme retired at the pits. Pratt continued to draw ahead and on the 3rd lap had a lead of over 2½min on Sunderland. Hazelhurst, with a lap in 32min 27sec (including the compulsory stop) had drawn into 3rd place, 11min behind Sunderland. And then, on the last lap, as so often happens in a TT race, whether it be

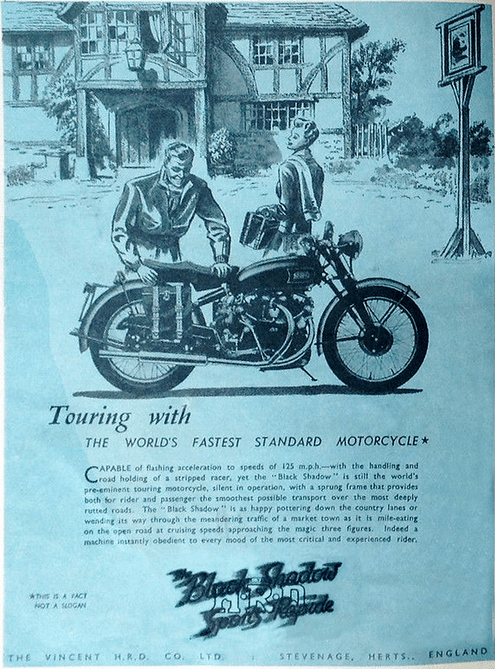

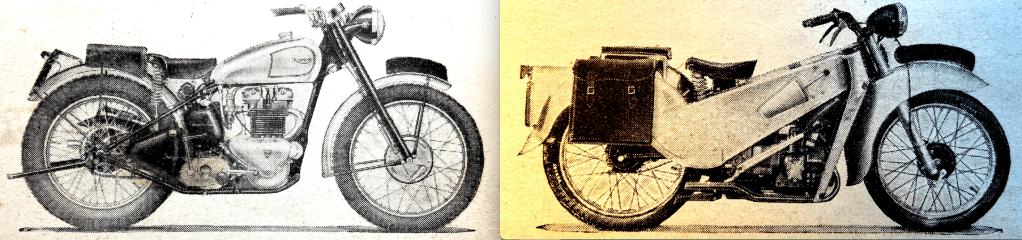

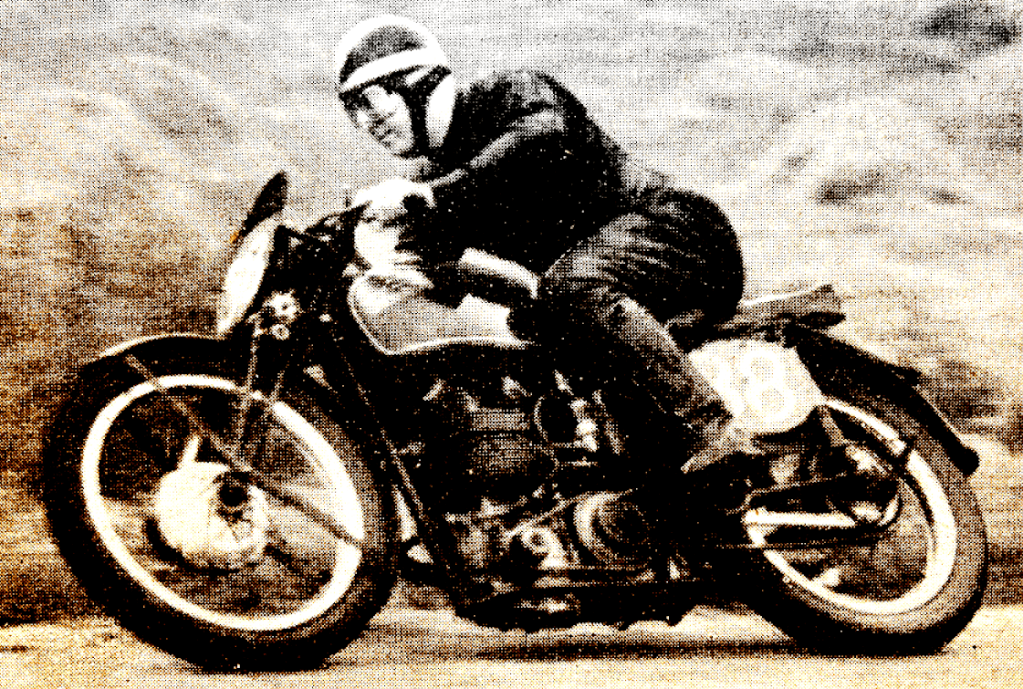

International or Clubman’s, things began to happen. Pratt had gone past the pits with the ‘thumbs down’ signal—although he had lapped in 31min 11sec, fastest 3rd lap of the race—and at Union Mills he retired with a split tank. Sunderland, who then seemed an easy winner, slowed down, his last lap taking 35min 3sec and Hazelhurst, with a lap in 31min 52sec, came home winner by nearly a minute-and-a-half. So although there was not a Velocette in the first six on Lap 1, a Velocette won the 1948 Clubman’s Junior, Hazelhurst having risen from 7th to 1st place in the last three laps. Result: 1, RJ Hazelhurst (Velocette), 70.33mph; 2. GW Robinson (AJS); 3, M Sunderland (Norton); 4, JF Jackson (Velocette); 5, ID Drysdale (AJS); 6, 0P Hartree (Velocette); 7, AF Wheeler (Velocette); 8, C Julian (Velocette); 9, DE Morgan (AJS); 10, L Peverett (AJS); 11, EN Peterkin (AJS); 12, JK Beckon; 13, AS Herbert (Matchless); 14, WM McLeod (AJS); 15, J Fisher (Ariel); 16, H Roberts (AJS); 17, SA Milne (EMC); 18, A. Peatman (AJS);19, J Terry (Ariel); 20, A Broadey (Norton); 21, A Klinge (BSA). Eighteen riders received free entries to the Manx Grand Prix, and 21 of the 35 starters finished the race. The Senior race, which was even fuller of excitements than the Junior, was notable for the large fleet of 1,000cc machines which faced the starter. In 1947 only two ‘big ‘uns’ were entered—and neither started! In 1948 there were 11—10 Vincent HRDs and a Square-Four Ariel, and all of them started. Nine of the Vincent HRDs finished, 1st, 2nd, 5th, 6th, 8th, 9th, 13th, 19th and 26th—90% finishers—a remarkable tribute to their reliability, manoeuvrability and speed. In addition, the only

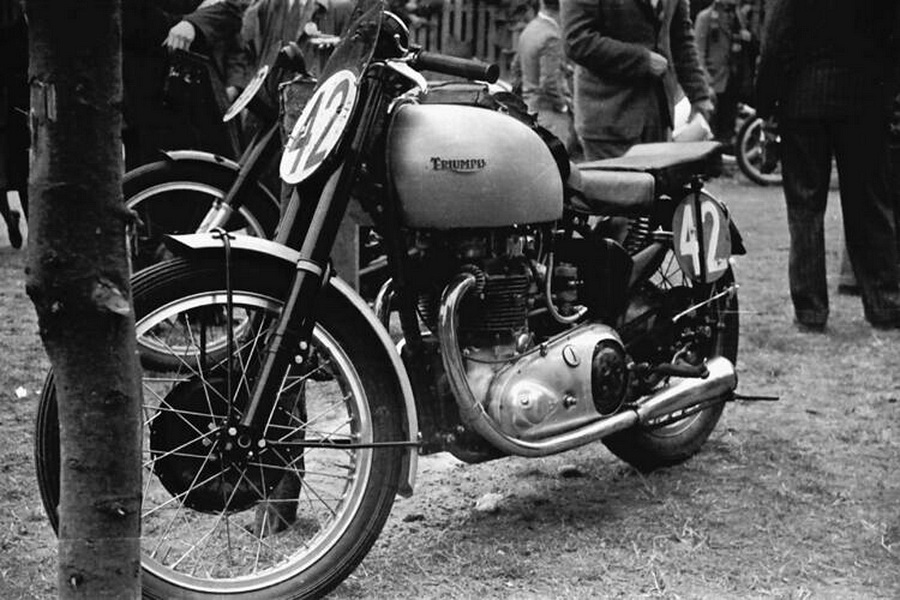

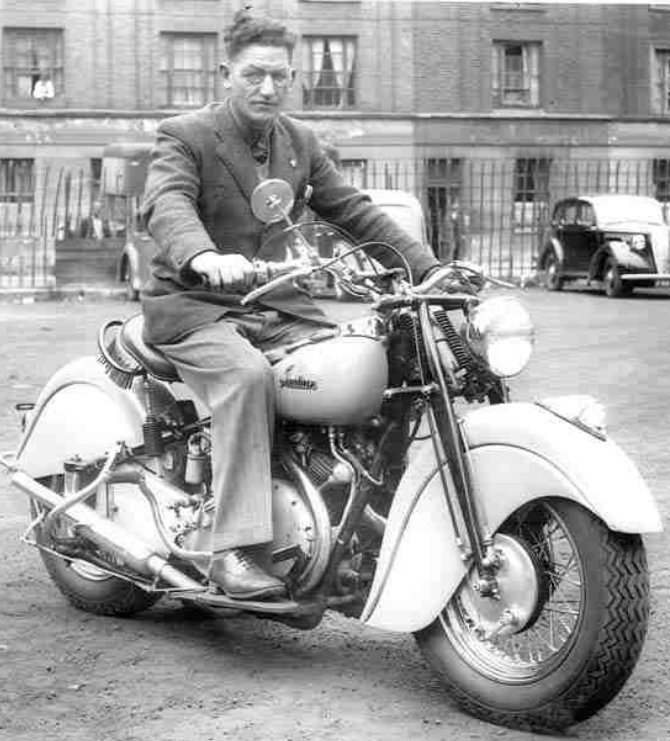

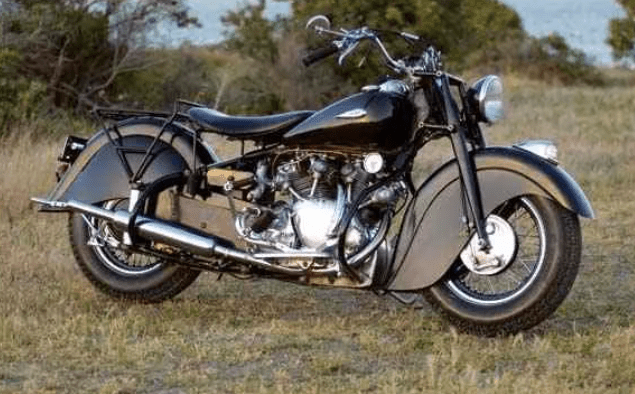

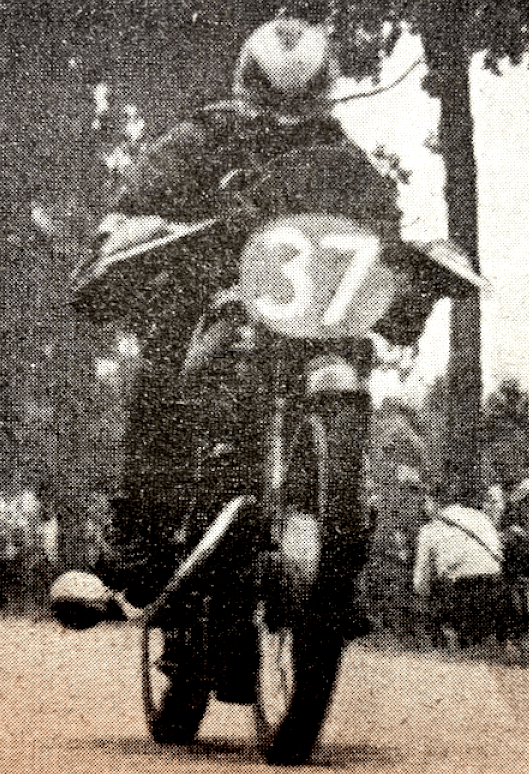

single-cylinder Vincent entered finished 11th, so the Stevenage firm can be congratulated on a real day out. It was a bit tough, of course, on the fleets of Nortons, Triumphs and others of half the size who competed, but there it was. The Rules and Regulations allowed machines of up to 1,000cc, so no one can blame the clubs and riders for entering the biggest machines permissible. And in practice, as already recorded, there did not seem to be much in it, for the first four positions on the practice leader board were divided amongst the big ‘uns and the little ‘uns, with Vincent HRDs 1st and 3rd, and Triumphs 2nd and 4th, and only 41sec between them all. It was quite different in the race itself. George Brown (Vincent HRD), whose fastest practice lap was 30min 58sec, set off with a lap in 28min 10sec and from a standing, kick-start at that! Allan Jefferies (Triumph), most formidable member of the little ‘uns, overtook several riders in the early stages, but he retired with tank trouble at Ballaugh, and JD Daniels (Vincent HRD) was a close 2nd to Brown, with Phil Heath on a similar machine third. Bill McVeigh (Triumph) was 4th, and Norton in the hands of CA Stevens and H Clark were 5th and 6th. On his 2nd lap Daniels beat the 28min mark by 1sec, but Brown was faster still, with a lap in 27min 24sec, at 82.65mph; this was actually the fastest lap of the day and constituted the Clubman’s Senior record, being 54sec better than Eric Briggs’ record of 1947. Brown was therefore comfortably in the lead and there was no change in the positions of the next four men. H Clark, however, dropped back and RJ Vernon, on another Vincent HRD, drew into 6th place. Brown kept forging ahead and at the end of the 3rd lap was over a minute-and-a-half ahead of Daniels who in turn was over a minute in front of Heath. Daniels was No 62, Heath No 68 and Brown No. 93. Daniels came past the pits, the first Senior to finish, whilst Heath and Brown were shown at Creg-ny-baa. Then Heath finished—but there was no sign of Brown. And suddenly came the news from Hilberry that he was pushing—pushing that massive machine up the rise to Cronk-ny-Mona, with the further rise from Governor’s Bridge to tackle, and then the long straight-and-level to the pits. The reason?—too quick a ‘fill-up’ at the end of the second lap, and out of petrol. So from being what looked like an easy winner poor George dropped back to 6th place, with a last lap of nearly forty minutes, as against his best of 27min 24sec. Result: 1, Jack Daniels (Vincent HRD), 80.51mph; 2, Phil Heath (Vincent HRD); 3, CA Stevens (Norton); 4, W McVeigh (Triumph); 5, EJ Davis (Vincent HRD); 6, G Brown (Vincent HRD); 7, H Clark (Norton); 8, C Horn (Vincent HRD); 9, F Fairbairn (Vincent HRD); 10, E Andrew (Norton); 11, JE Carr (Vincent HRD); 12, AA Sanders (Triumph); 13, RJ Vernon (Vincent HRD); 14, RF Walker (Norton); 15, AMS Smith (Norton); 16, DG Crossley (Triumph); 17, WJ Netherwood (Norton); 18, J Harrison (Ariel); 19, WF Beckett (Vincent HRD); 20, JH Colver (Matchless); 21, TG Wycherley (Ariel); 22, TH Hodgson (Triumph); 23, N Osborne (Triumph); 24, JT Wenman (Norton); 25, HF Hunter (Triumph); 26, A Crocker (Vincent HRD); 27, PH Carter (Norton); 28, AR King (Triumph); 29, D Whelan (Rudge); 30, LJBR French (Norton); 31, S. Parsons (Triumph). Twenty-three riders received free entries for the Manx Grand Prix, and 31 of the 41 starters finished the race. The 1948 Junior TT with its entry of 100 riders was easily the biggest Junior up to date, the previous record for entries being 72, in 1923—a quarter of a century before. There were 10 non-starters, but the only ‘possible winner’ amongst them was David Whitworth (Velocette) who had crashed in a Continental race earlier in the season and was not fit to ride. Practice form indicated that the race would be a scrap between Nortons and Velocettes, for these makes occupied the first six positions on the Practice Leader Board…Practice form, however, does not show everything, for there was one who did not even appear in the first six—none other than grey-haired ‘veteran’ Fred Frith (Velocette). After a Sunday when the weather was so dreadful that the Peveril Club’s Scramble had to be abandoned—and scramble promotors usually like bad weather!—the Monday of the Junior race dawned clear and bright, but with a very strong wind. The 90 men who faced the starter were mounted on five makes only—36 on Nortons, 27 on Velocettes, 23 on AJS ‘Boys’ Racers’, three on Excelsiors, and one on an OK Supreme. The ‘Boys’ Racers’, promising as they seemed, were too new and untried to constitute a serious menace to the Nortons and Velocettes, and the Excelsiors and the OK Supreme were in the ‘veteran’ class. A Norton or a Velocette would obviously be the winner—Bracebridge Street or Hall Green—which?…Fred Frith, in his first TT for nine years—he was injured in practice in 1947 and did not ride in race week—riding as well as ever, was 3rd on the roads at Ballacraine and 1st at Kirkmichael, only 14 miles from the start. And whilst Bob Foster and many others of the back-numbers were on the Kirkmichael-Ramsey stretch, Fred tore past the pits, having completed his first lap in 28min 8sec. This was 32 seconds outside Artie Bell’s best practice lap, but the strong wind, blowing mainly against riders on the mountain climb, spoilt all chances of very high speeds. Fred’s time, however, was 6sec better than that of the next man—Bob Foster from the back end of the ‘possibles’ list—and 19sec better than that of Harold Daniell (Norton)…True to form five of the ‘famous seven’ occupied the first five places—Frith, Foster, Daniell, Lockett and Bell. Eric Briggs was 7th, 2sec behind Miller, but Les Archer was obviously in trouble, for when he did complete his first lap it had

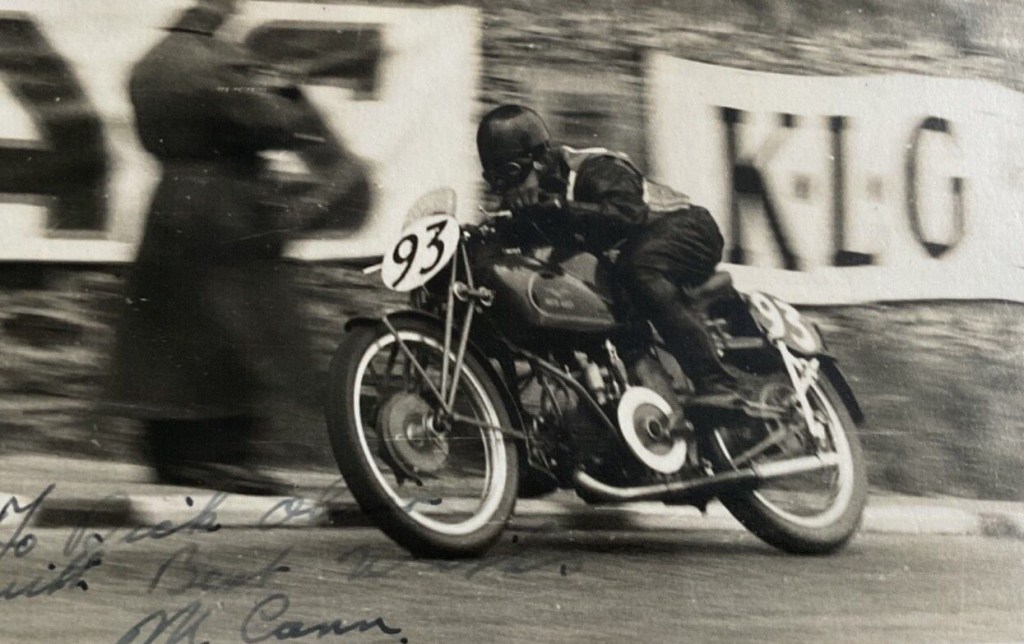

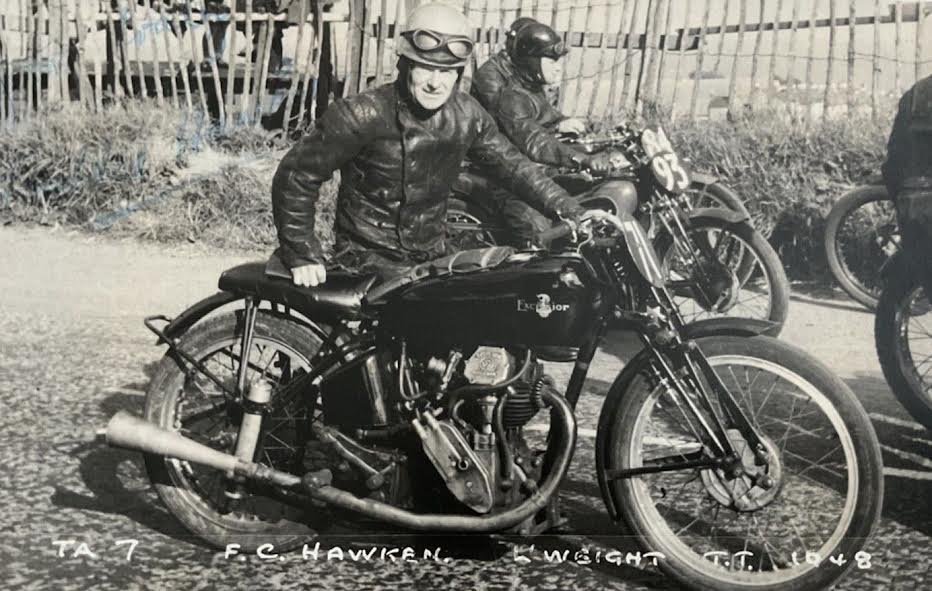

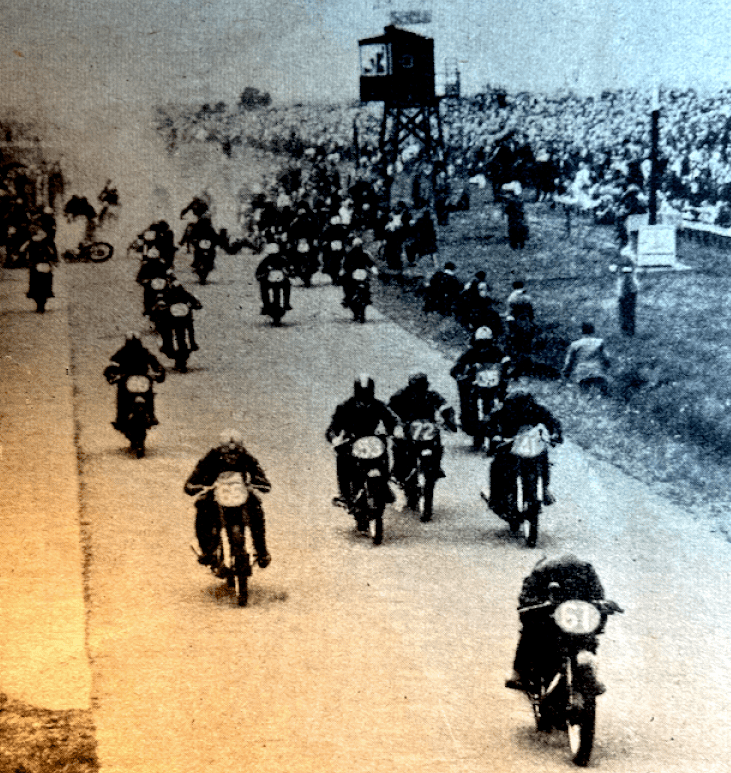

taken him—over two hours! There was no change amongst the leaders on the second lap, except that Briggs displaced Miller. Frith increased his lead on Foster to 20sec and Foster was 35sec ahead of Daniell. Velocettes first and second, the four ‘official’ Norton entries 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th. No change again on Lap 3. Frith came in to refuel, but Foster went straight through. Fred’s ‘slow-down’ for the pit stop dropped his lead from 20sec to 15sec, with Bob one minute clear ahead of Harold Daniell—3min 20sec separated the 1st from the 6th. On the 4th lap Bob Foster came temporarily into the lead—due to Fred’s 3rd lap stop—and Harold Daniell slowed down, to tour in and retire at the end of the circuit with tank trouble. Foster’s position as leader did not last long, for he was filling up at his pits whilst Frith was tearing on somewhere along the far side of the Course. Fred’s 5th lap took 27min 35sec only—fastest of the day so far—whereas Bob’s, including the time spent at his pits, took 28min 44sec. The result was that by the end of the 5th lap Fred had the ‘comfortable’ lead of 55sec. Bell and Lockett were still 3rd and 4th, with only 6sec between them, but Bell was over 3min behind Foster. Maurice Cann, on the ‘Boys’ Racer’, had slipped past Eric Briggs, and was now in 5th position, just over half-a-minute ahead of the 3rd Norton rider. And so it continued to the end, Foster slowed down on the last lap but had sufficient lead over Bell to retain second place. Result: 1, FL Frith (Velocette), 81.45mph; 2, AR Foster (Velocette); 3, AJ Bell (Norton); 4, J Lockett (Norton); 5, M Cann (AJS);. 6, EE Briggs (Norton); 7, RL Graham (AJS); 8, ES Oliver (Velocette); 9, SM Miller (Norton); 10, GL Paterson (AJS); 11, LG Martin (AJS); 12, LA Dear (AJS); 13, JM West (AJS); 14, G Newman (AJS); 15, H Carter (AJS); 16, E Lyons (AJS); 17, AE Moule (Norton); 18, W Maddrick (Velocette); 19, 0S Scott (Velocette); 20, S Lawton (AJS). The above received replicas of the trophy and 28other riders finished the race…The Club Team Prize was won by the Cambridge Centaur MCC, consisting of M Cann and G Newman (AJSs) and AE Moule (Norton). No Manufacturer’s Team Prize was awarded. The 1948 Senior race was actually run and won before the Lightweight held on the same day, but in accordance with my usual practice of finishing with the ‘Big Race’ I will describe the Lightweight first. Entries for the two events, as on the other race days, were limited to a total of 100, these being made up of 31 in the Lightweight, and 69 in the Senior, and for the first time since 1924, when a massed start was used for the Ultra-Lightweight race, and the second time only in the history of the race, the Lightweights were despatched ‘en masse’. The Seniors started at 11am at ten second intervals, the last of them getting away at 11.11½am. There was then a lull of 3½min, and at a quarter past eleven the 26 Lightweights—there were five non-starters—tore down Bray Hill together. There were six makes amongst the 26—five Guzzis in the hands of Maurice Cann, Manliff Barrington, Tommy Wood, Leon Martin and Ben Drinkwater, and 21 nine, 10 and 12-year-old British models—nine Excelsiors, five New Imperials and Rudges, one ‘Ellbee Special’ and one Velocette. The fastest rider in practice had been Barrington, with a lap in 30min 47sec, but Maurice Cann had lapped in only 14sec more, and after these two came four Excelsior riders, Hawken,

Carter, Higgins and Webster. Roland Pike (Rudge) who, as it happened, was the main British ‘hope’, was not even on the Practice Leader Board. Off they went with a terrific roar, and—contrary to the pessimists’ prophecies—there were no ‘fearful melees’ or ‘blood baths’ on Bray Hill. Then at the Grand Stand there was silence, and we glued our eyes on the clocks. Barrington was in the lead at Ballacraine, with Pike second and Carter third. There was no sign of Cann, who must have been missed in a bunch, for it was announced that at Ballaugh—just under halfway round—Cann was on Barrington’s tail. Same order at Ramsey, with Pike and Tommy Wood in close attendance. Sixty odd Seniors passed the pits before the Lightweight riders reappeared, and the order was then seen to be: Barrington, Cann, Wood, Pike, Drinkwater and, 6th, RA Mead (New Imperial). And off they all went again, and once more there was silence except for an occasional straggler. On the second lap the order of the first three was the same, but Maurice had reduced Manliff’s lead from 12sec to nine, and both were drawing away from Tommy Wood. Ben Drinkwater had slipped past Roland Pike and was second ahead of him in 4th place, with Mead still 6th. Guzzis 1, 2, 3 and 4! But things began to happen in the 3rd lap. To start with, Tommy Wood retired at Quarter Bridge; then it was seen that Barrington had stopped, and soon after came the news that he had retired near Kirkmichael; and finally Drinkwater slowed down—his 3rd lap took him about six minutes longer than his first or second—and dropped off the Leader Board. So from holding the first four positions on Lap 2, Guzzis held only one—1st—on Lap 3. British hopes began to rise a little. Maurice Cann, however, had the very substantial lead of 41min over Roland Pike, who was second. Mead was third, half-a-minute behind Pike, and Excelsiors in the hands of Sorensen the Dane, Hawken and Beasley were 4th, 5th and

6th. Cann continued to draw away in the fourth lap…There was no change in the fifth lap, except that Ben Drinkwater came back into the picture, to displace Petty from 6th position. Next lap saw the retirement of Mead, who had put up a gallant show on his veteran New Imperial. This allowed Hawken into 3rd place for a lap, and then he too retired, at Ballaugh, 20 miles from the end. And Maurice Cann, never challenged in the later stages of the race, won by nearly 10 minutes. Result: 1, M Cann (Guzzi), 75.18mph; 2, RH Pike (Rudge); 3, D St J Beasley (Excelsior); 4, B Drinkwater (Guzzi); 5, RJ Petty (New Imperial); 6, J McCredie (Excelsior). Only six riders finished and all received replicas. No Manufacturer’s or Club Team Prize was awarded. As mentioned earlier there was an entry of 69 for the 1948 Senior, as against 33 only the year before. The entry of 69 did not constitute an absolute record, for in 1914 there were 111, but it was the highest since that race of 34 years ago. The original entries comprised six makes, in alphabetical order as follows: AJS (6), Gilera (3), Guzzi (4), Norton (41), Triumph (9) and Velocette (6). The three Gileras, however, failed to materialise, and their numbers were handed over to riders of British machines—one AJS and two Nortons. There were 13 non-starters, reducing the total to 56, made up of seven AJSs, three

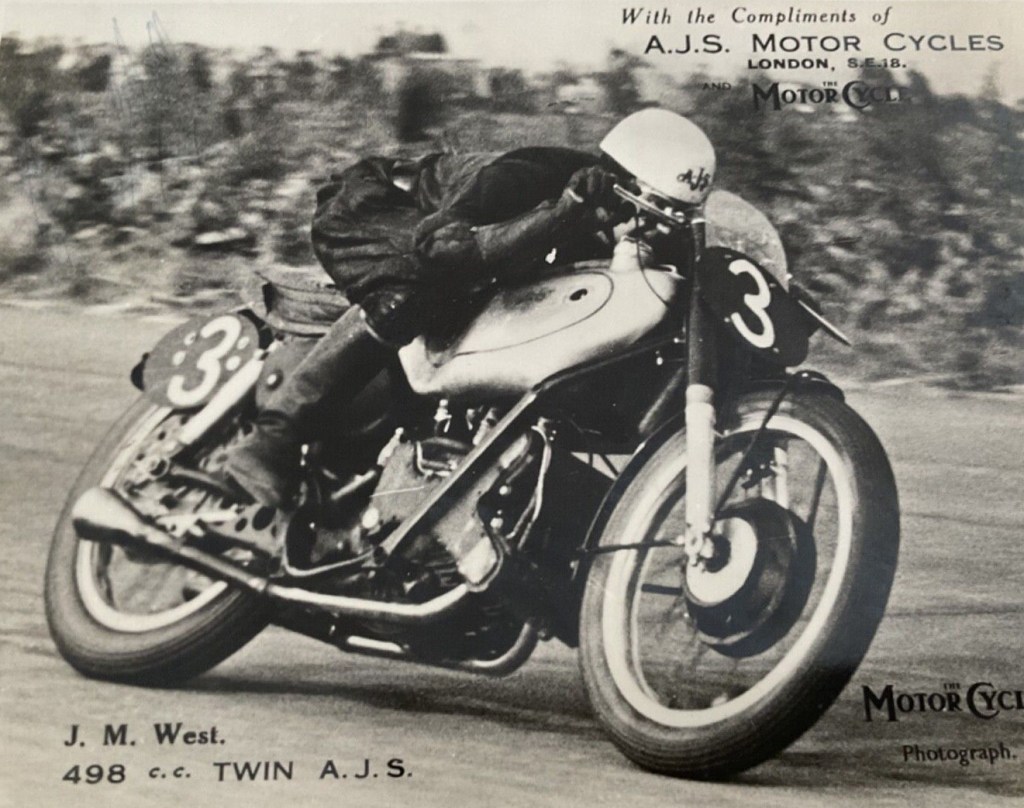

Guzzis, 33 Norton, seven Triumphs and six Velocettes; 16 of them were 350cc models—four of the AJSs, six of the Nortons and all the Velocettes. No one can deny that the favourite for the race was that grand little Italian rider Omobono Tenni, who was killed a few weeks later when practising for the Swiss Grand Prix. By his friendliness, his cheerfulness and, above all, by his terrific riding Omobono endeared himself to all of us, and his loss to motor cycle sport will be felt in the same way as the loss of Jim Guthrie and of Wal Handley. Omobono had put up the fastest practice lap in 26min 44 seconds—12sec better than the fastest 1947 lap, and 11sec better than the next best practice lap, that of Ernie Lyons on another Guzzi.The Practices Leader Board read as follows: 1, O Tenni (Guzzi), 26min 44sec; 2, E Lyons (Guzzi), 26min 55sec; 3, AR Foster (Triumph), 26min 58sec; 4, K Bills (Triumph) 27min 8sec; 5, RL Graham (AJS), 27min 22sec; 6, EJ Frend (AJS), 27min 23sec. Two Guzzis, two Triumphs and two Ajays—not a Norton amongst the first six, though Norton had won the 1947 Senior and, indeed, eight out of the last 10 Seniors! Truly one cannot rely too much on form in practice. In compiling a list of ‘possibles’, however, I must add the four ‘official’ Norton riders—Bell, Briggs, Daniell and Lockett—Jock West, third of the ‘official’ AJS team, and, of course, Fred Frith on his Triumph…Friday, 11th June, 1948, dawned wet and misty, but by 9am the rain had stopped and the clouds were lifting. It was far from an ideal day for the Big Race, but conditions improved and by 10.30am—half-an-hour before the scheduled start—visibility on the mountain was just about good

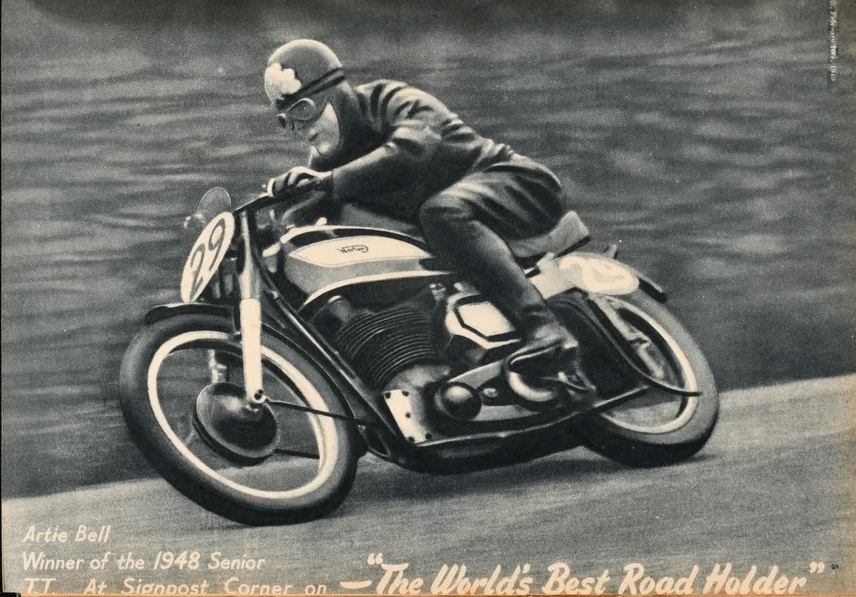

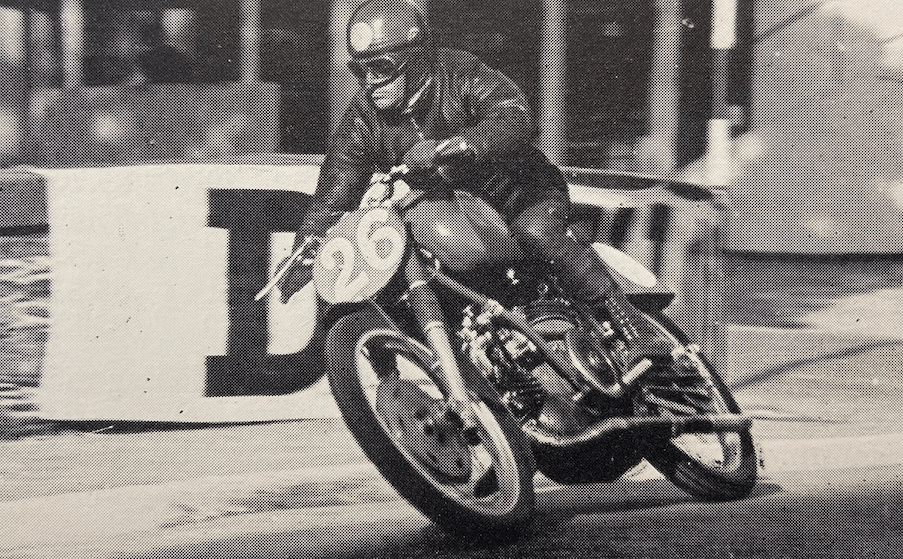

enough. There was no question of a postponement. All the 56 got away without trouble, and Ernie Lyons was leading the field on the Kirkmichael-Ramsey stretch as the last man, No 70, JEC Purnell (Norton), was despatched. First rider to retire was Vic Willoughby (Triumph) as early as Quarter Bridge, whilst W Maddrick (Velocette) crashed at the same spot but was able to continue. Lyons had a substantial lead at Ramsey and at the Mountain Box, but by Creg-ny-baa Tommy McEwan (Norton—No 3) had overtaken him and then there was news that Ernie had crashed at the Bungalow, and had retired…Past the pits at the end of the first lap they came as follows: 1st, No 3, McEwan; second, No 9, Frith; third, No 1, LP Hill (Norton); and 4th, No 26—0mobono Tenni going, as I described it at the time, ‘faster than any scalded cat’. His lap, from a standing start in worse than average weather conditions, had taken 25min 51sec only. This was 1min 5sec faster than 1947’s best, and represented a speed of 87.60mph! Ted Frend retired at Ballig Bridge and Eric Briggs at Barrowgarrow on the 1st lap; Johnnie Lockett and Fred Frith packed up in the second lap. Meanwhile Omobono Tenni kept cracking along. His second lap was not quite so fast as his first—26min 19sec—but it was 10sec better than Les Graham’s, so Omobono had increased his lead to 39sec, with Harold Daniell 10 seconds behind Graham…Except for the fact that the times were widening there were only two changes on the Leader Board. Artie Bell now figured in 4th place and Ken Bills in 6th, Bob Foster, previously sixth, had stopped at Creg-ny-baa, reported tank trouble and continued to the pits to retire. Lots of things happened in the 3rd lap. To begin with, Omobono drew into his pit and spent a long

time refuelling and adjusting—1min 35sec, I made it. This temporarily put Les Graham into the lead, but he in turn retired at Ballig Bridge. Harold Daniell must have been leading for a spell but Artie Bell had got cracking—his third lap, in 25min 56sec, was his fastest of the day—and Omobono was making up for lost time. In spite of a 1min 35sec pit stop, and the time lost in pulling up and restarting, he lapped in 27min 20sec. This might well have been a 25½min lap, had it been non-stop, but even as it was it got him back into the lead at the end of Lap 3, by the margin of just 1sec over Bell…Tenni increased his lead substantially, first because he had a non-stop 4th lap in the post-war record time of 25min 43sec and secondly became Bell had refuelled at the beginning of the lap. More excitement in the 5th lap. That terrific 4th circuit had had its effect on the Guzzi mechanism, for Tenni was forced to stop at Union Mills ‘for adjustments’. Bell, who had started half-a-minute behind the Italian, had caught him on the roads and the pair were signalled at Kirkmichael together—ie, Bell had a half minute lead; somewhere near Kirkmichael Tenni stopped again and at Ramsey the Irishman was signalled fully a minute ahead of the Italian. Starting No. 29 he was leading on the road; Tenni (No 26) was 2nd on the road and Harold Daniell (No 66) 3rd, having overtaken Omobono on time. In the 5th and 6th laps there were two more retirements in the ‘big 12’—Ken Bills at the Bungalow in the 5th and Jock West at Ballacraine in the 6th; and then there were three. And these three were running 1st, 2nd and 3rd. Both Nortons had a fair lead on the Guzzi, but

in view of Tenni’s previous terrific laps it was too early to say that the race was in the bag. The 6th lap, however, decided it—bar accidents. Tenni’s time for it was better than that for his 5th, but even so it was over a minute slower than those of both Norton riders. The Irishman led the Italian by over 31min and Harold Daniell was 2min 50sec ahead of him—too much for even Omobono to pick up, on a clear run, against two such brilliant riders. So the race drew swiftly to its close. A meteoric lap by Harold Daniell might have given him victory again. In 1947, in similar circumstances, Harold pulled up 23sec on Artie on the last lap—but 41sec seemed too much to expect. And as it was, on the last lap, Harold stopped at the Highlander, got going again but finally retired at the 13th milestone; and then there were two; and Artie avenged his 1947 defeat and went on to win his first TT. Meanwhile, what had happened to the 2nd—and last—of the Big 12? Artie had crossed the finishing line whilst Omobono was still shown at Ramsey. Long, long after, he was signalled at the Mountain and finally. at Creg-ny-baa. W Doran and JA Weddell (Nortons) and G Murdoch on a Junior AJS had all overtaken him as also, it appeared, had several others. And then came the news that Tenni was running on one cylinder only—the reason for the touring finish to his brilliant ride. We were proud of our British victory, proud of the fact that Artie Bell scored the 21st Norton TT win; but if it had had to be a foreigner there is no one we would have greeted more warmly than that gallant little Italian rider, Omobono Tenni. Result: 1, AJ Bell (Norton), 84.969mph; 2, W Doran (Norton); 3, JA. Weddell (Norton); 4, GG Murdoch (AJS); 5, NB Pope (Norton); 6, CW Petch (Norton); 7, H Pinnington (Norton); 8, J Brett (Norton); 9, 0 Tenni (Guzzi); 10, ES Oliver (Velocette); 11, SM Miller (Norton); 12, N Croft (AJS); 13, LP Hill (Norton); 14, LA Dear (AJS); 15, B Meli (Norton); 16, WJ Maddrick (Velocette); 17, IM Hay (Norton); 18, RJ Weston (Norton); 19, AA Fenn (Norton); 20, HB Ranson (Norton). The above received replicas. 21, M Klein (Norton); 22, H Hayden (Guzzi); 2,. E Braine (Norton). Fastest lap and winner of the Jim Simpson Trophy, 0 Tenni, 25min 43sec, 88.06mph. No Manufacturer’s or Club Team Prize was awarded.”

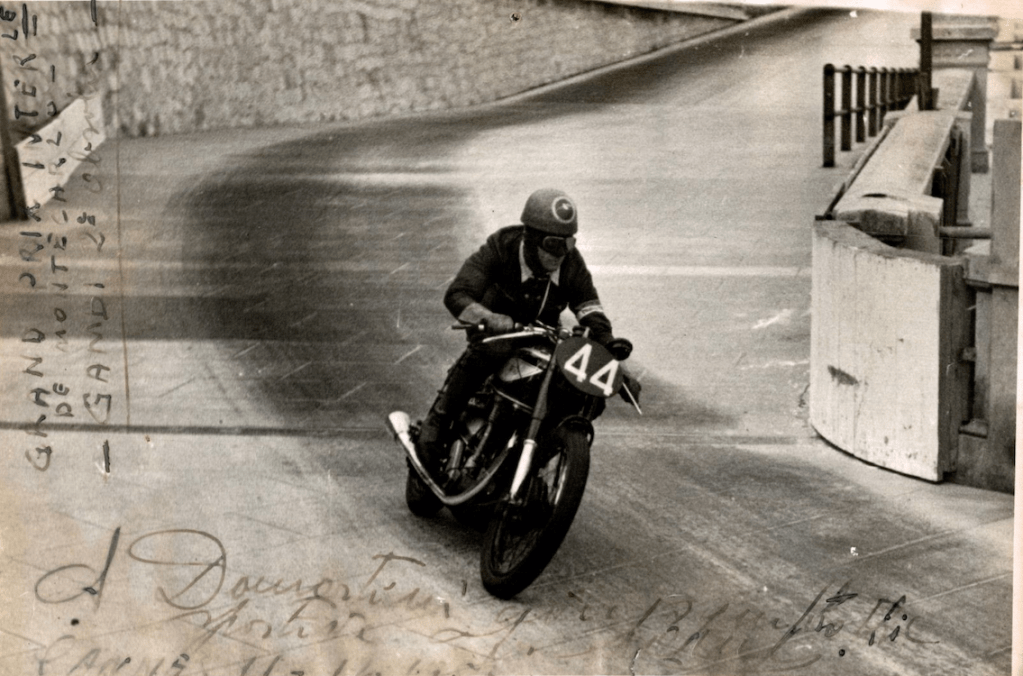

“SUNDAY’S GRAND PRIX Des Nations was the last of the 1948 classic road races. No British manufacturer is officially represented in the entry lists. This might seem strange, bearing in mind that the number of top ranking racing events is far fewer than pre-war. The reasons why our works riders are not competing are worth consideration. In the first place the circuit of Faenza, near Bologna, is not known to most British riders and is very short by accepted standards for classic contests. Secondly, there was no race for 350cc machines. Thirdly, the date was unfortunately placed between the Manx Grand Prix week and the International Six Days’ Trial; both these events make considerable demands on the resources of our manufacturers…It would appear that the time has come for the FICM to require the principal road race of each nation—the so-called classic races—to conform to closer standards than in the recent past.”

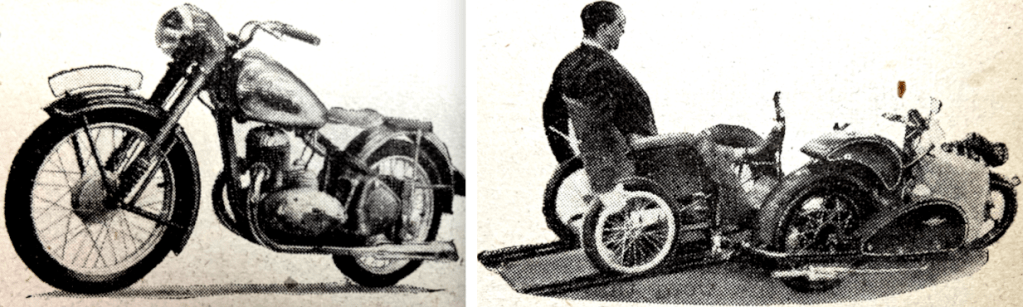

“THERE WAS MUCH about last Saturday‘s Cotswold Cup Trial that reminded one of the 1947 event. Apart from one new section the course was essentially the same and weather conditions gave it very similar characteristics: many easy hazards with one real corker, Henwood. Once again J Nicholson (499 BSA) was the winner and, as last year, he was the only competitor to lose no marks on Saturday. He rode a single-cylinder model for the first time in the open trials; his riding was impeccable throughout and it was an education to watch. In the sidecar class DK Mansell (497 Ariel) was the winner, with 22 marks lost. As this total suggests many parts of the course…were very difficult for sidecars. Mansel lost points only on Henwood, whereas the best of the other sidecar men lost at least eight marks. There were 131 starters.”

“AVERAGING MORE THAN 67mph over a 152-mile course S Jensen of Palmerston North won his second Senior New Zealand Grand Prix at Christchurch on Easter Monday. His riding on the square-shaped course was the greatest thrill for the crowd—he led practically all the way. Almost all parts of the six-mile circuit were lined with spectators; some watching the 46 starters roaring along the straights at over 100mph, others watching them negotiate the tricky sunken bridges where riders were aviated for yards at a time. The racing for the four events (senior, junior and lightweight) justified the enthusiasm evidenced by the crowd. Many machines failed to complete the course which was, in spite of the hot dry windy weather, less dusty than the other races.”

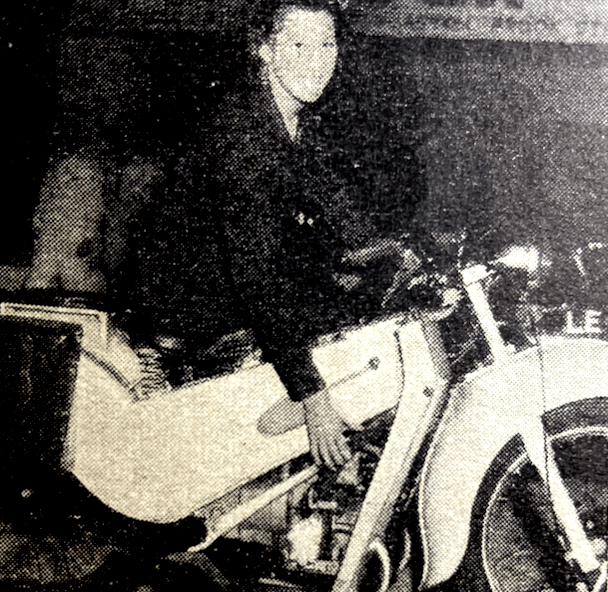

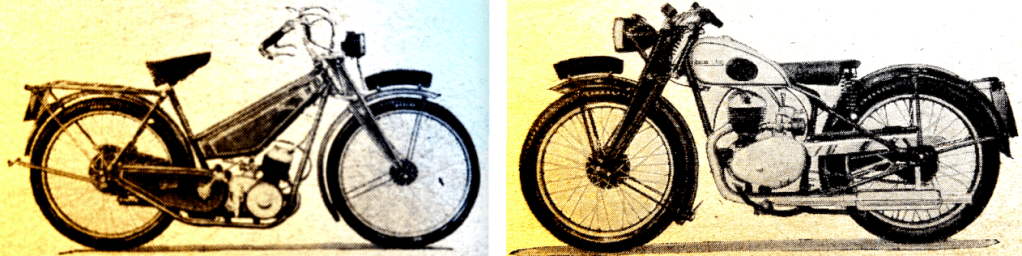

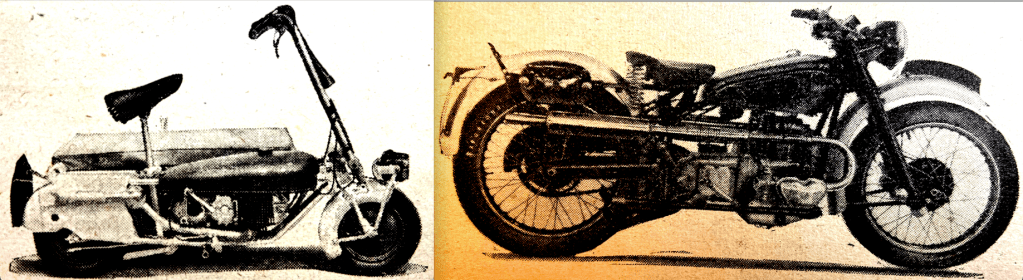

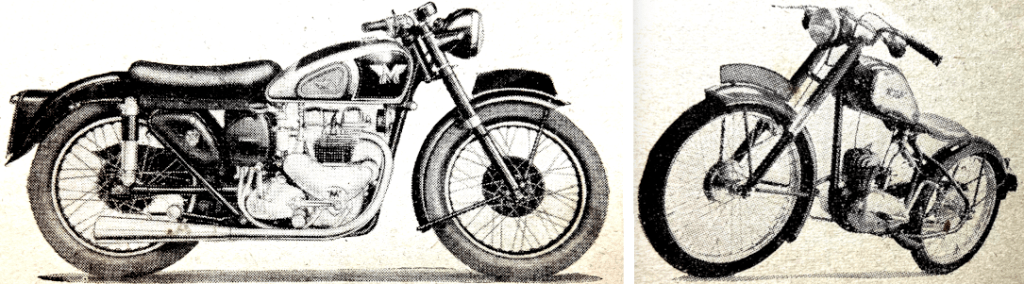

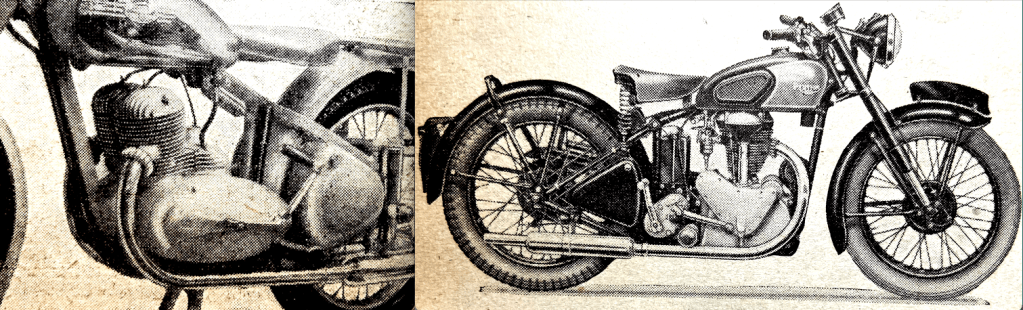

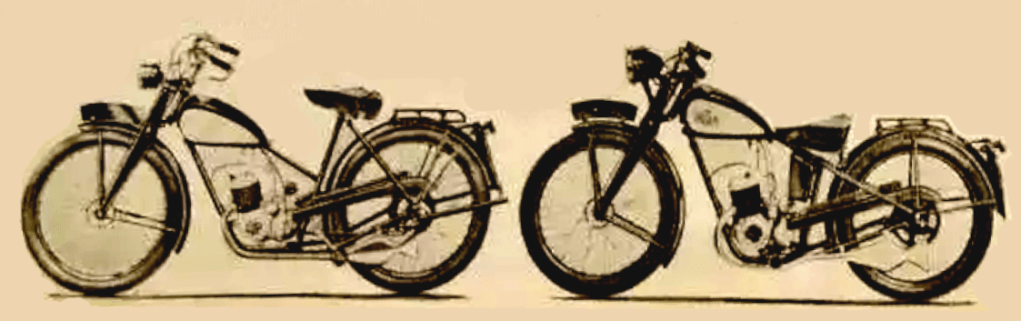

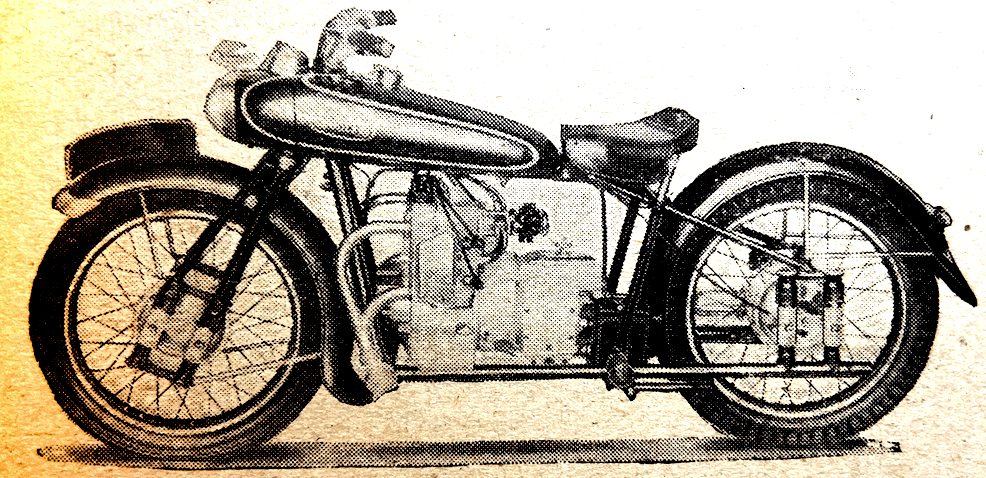

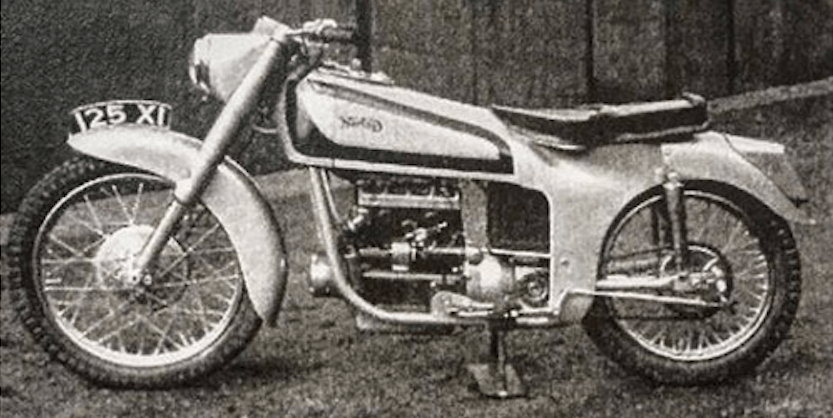

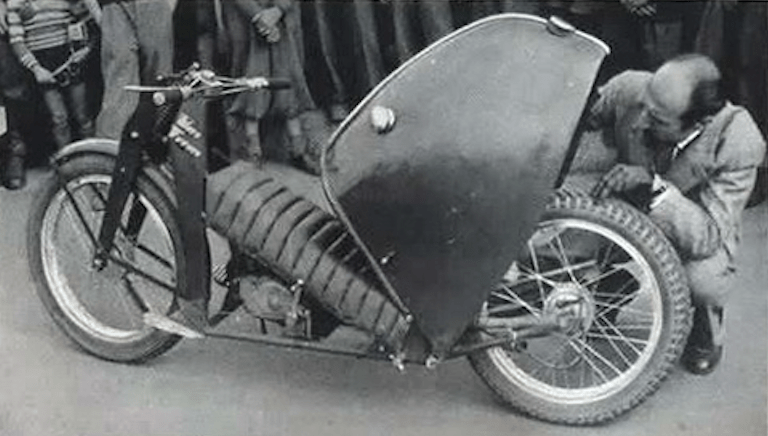

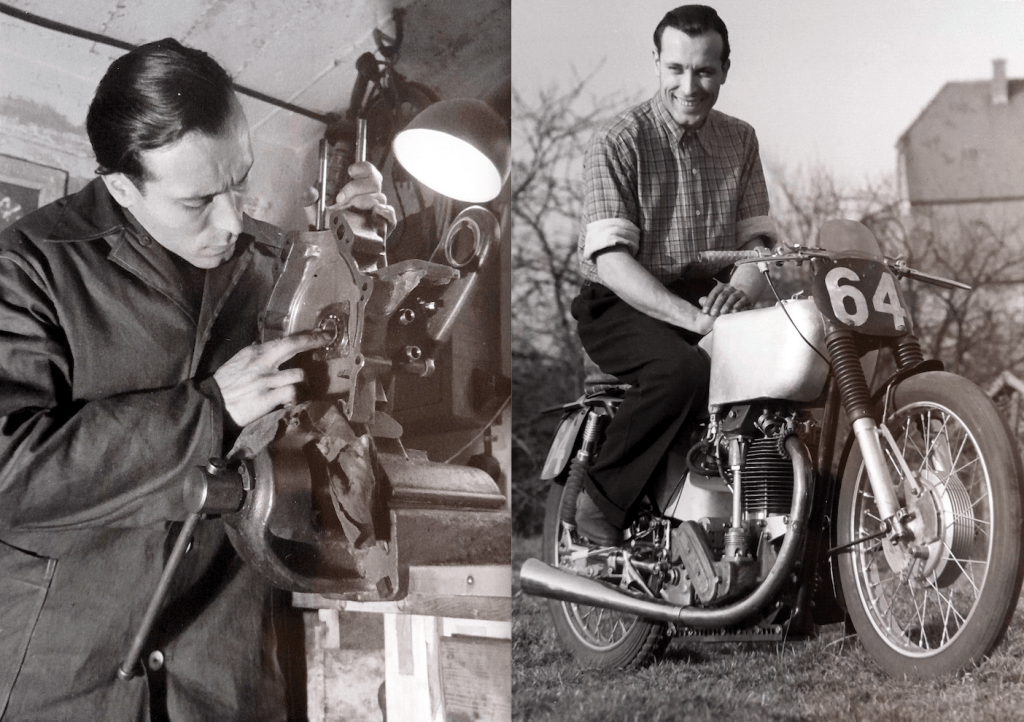

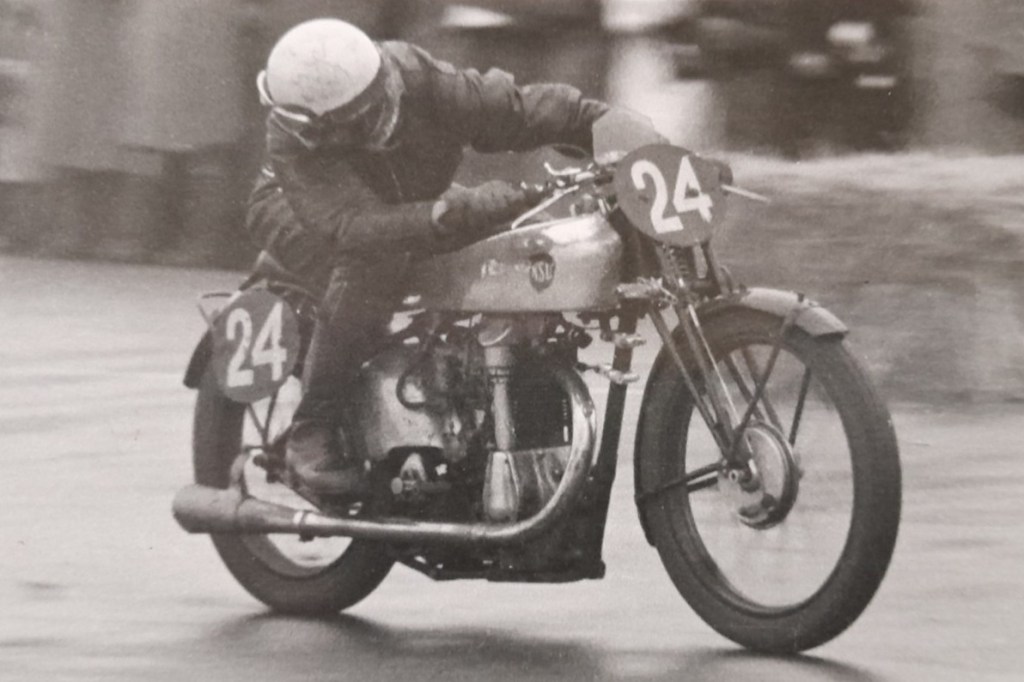

THE 98CC IMME R100 was only made (in Germany, by Norbert Riedel, who had built a starter motor for the ME262 based on the 98cc Victoria two-stroke) for three years which is a shame because this tiddler was packed with innovative features. The two-stroke horizontal ‘power-egg’ engine swung together with the rear wheel, which was connected to the centre of the machine by the exhaust pipe which doubled as one side of the frame. And there was only one fork leg. The single-sided layout facilitated wheel changes; the wheels were interchangeable and a spare could be bolted next to the rear wheel. Just before the factory closed a few 148cc examples were made.

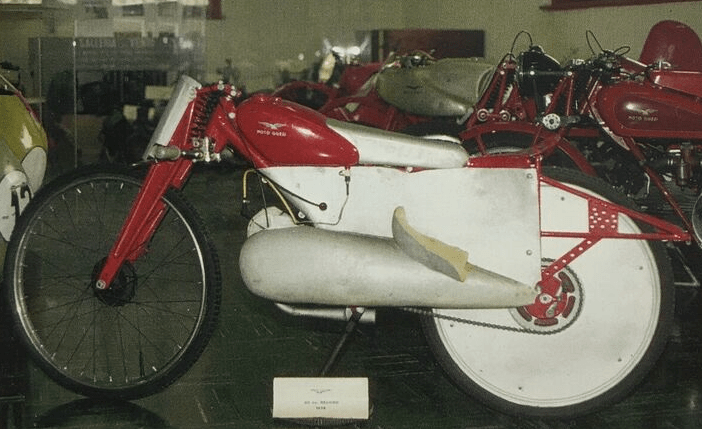

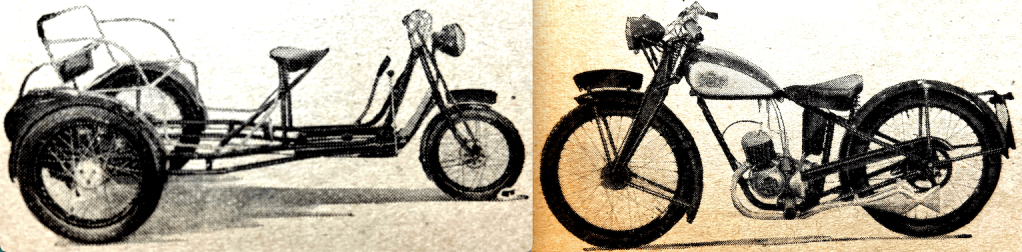

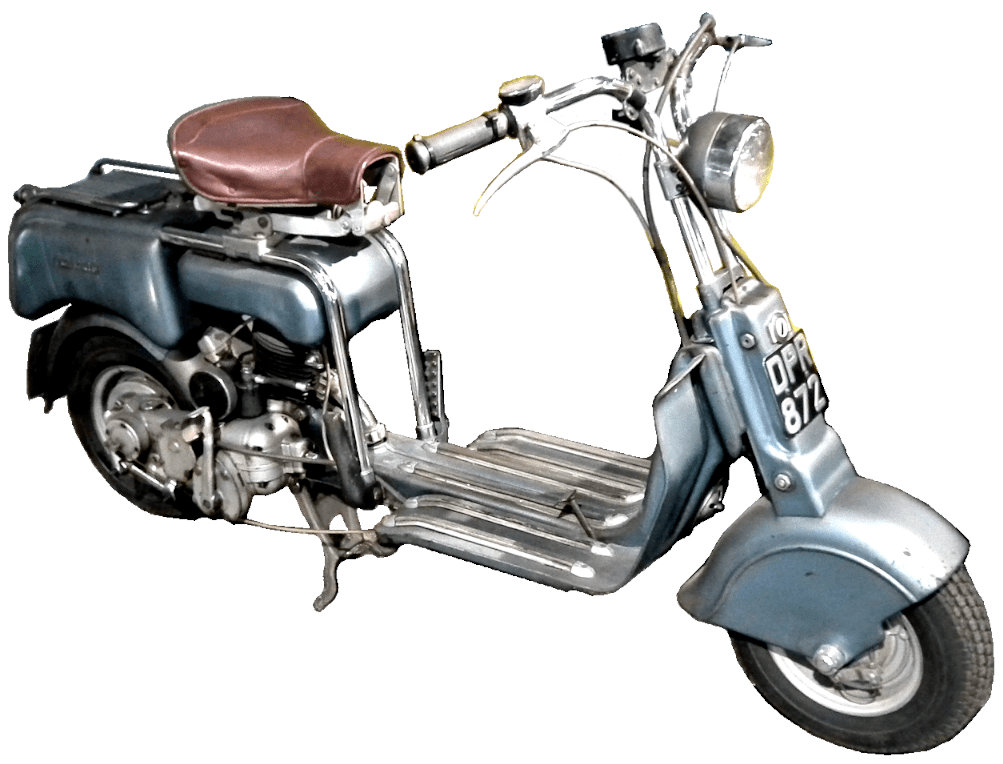

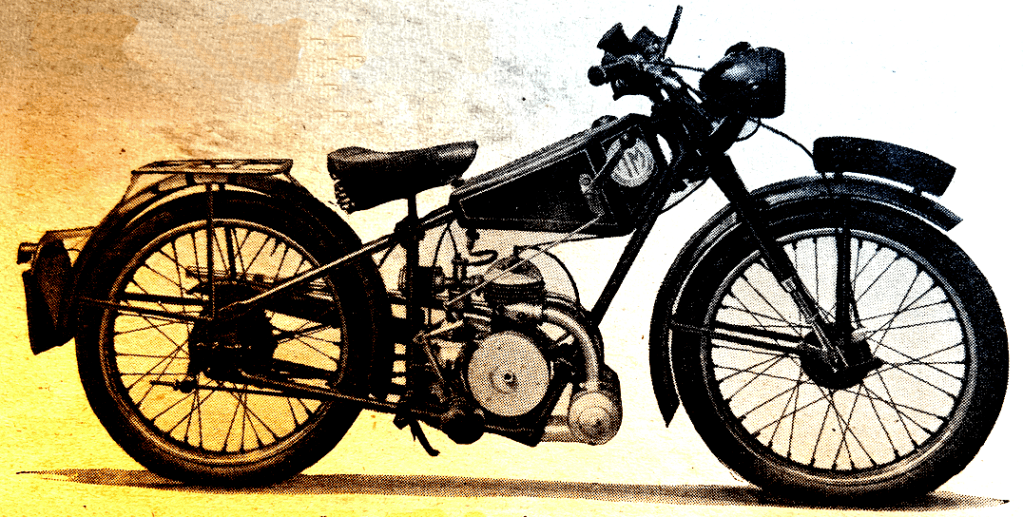

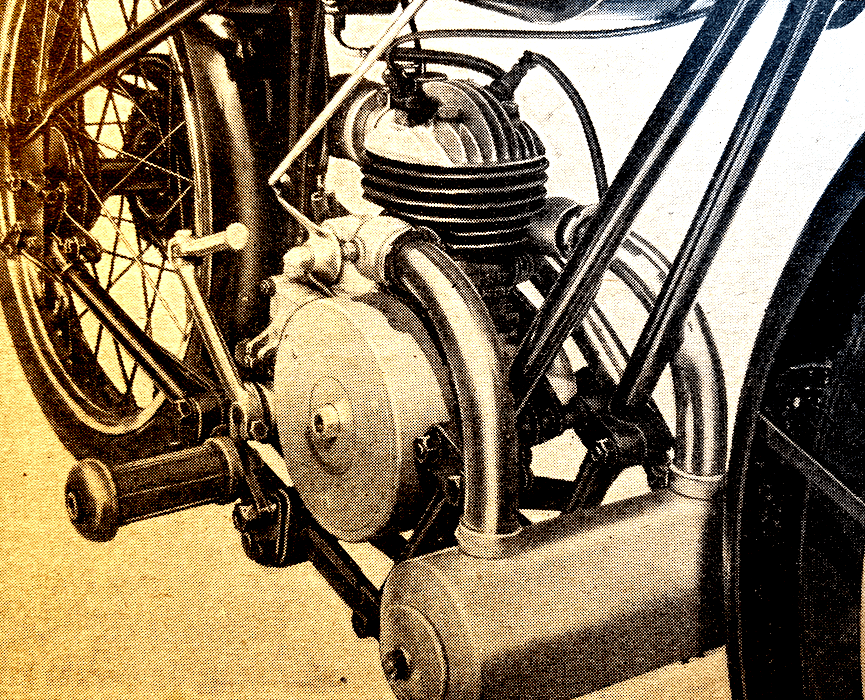

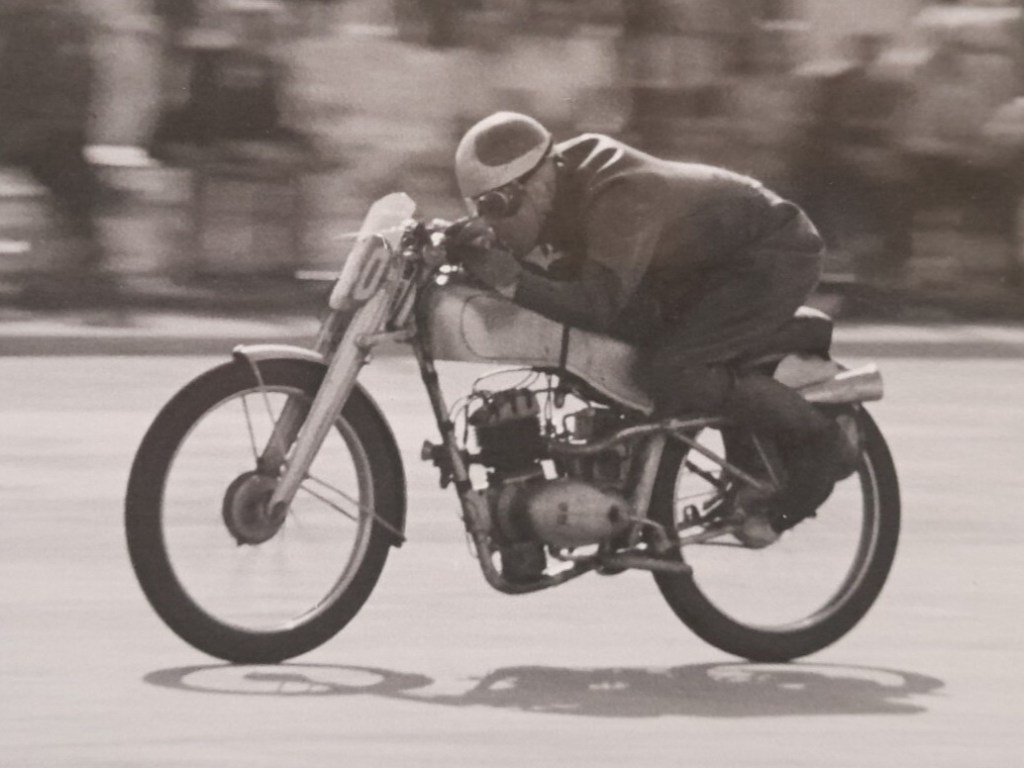

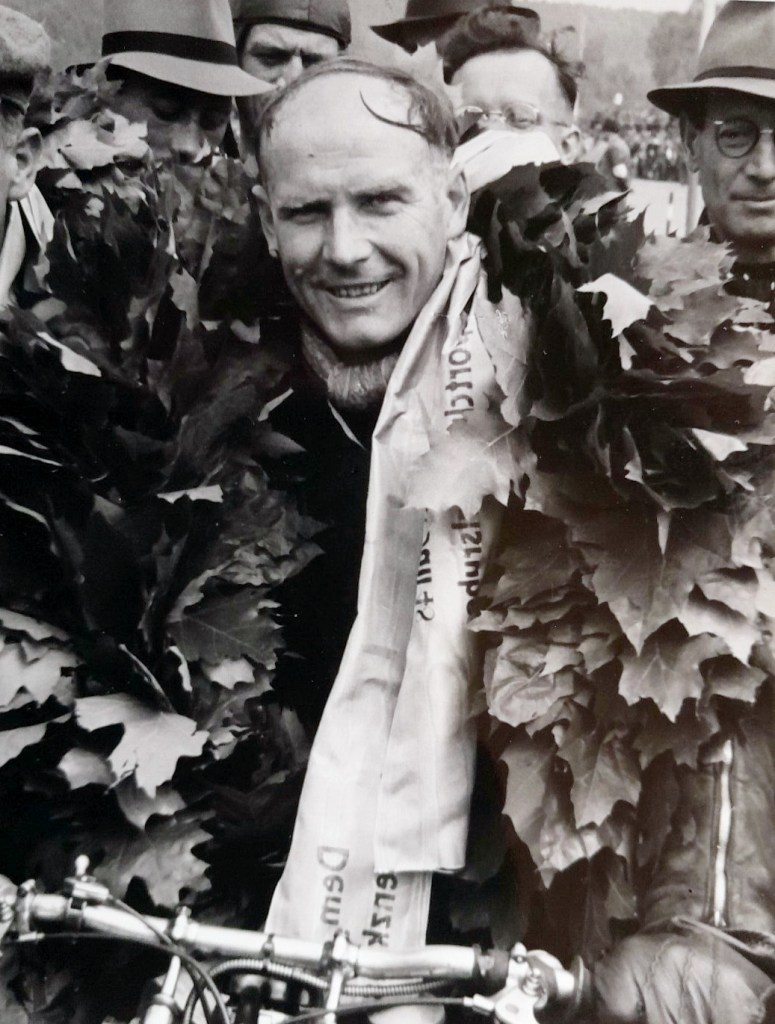

LIKE A NUMBER of British manufacturers Moto Guzzi offered a cyclemotor. Unlike the Brits the Italians came up with a racing version. The 73cc/2hp Guzzino 65 was tuned to produce 3.6hp at 6,300rom. Wrapped in a streamlined shell and weighing just 88lb it topped out at 62mph. Raffaele Alberti folded himself round the diminutive Guzzino to set 19 records at Monza, including a flying kilometre at almost 60mph and 1,000km at 47mph. The Guzzini became Italy’s top-selling tiddler; almost 72,000 were sold.

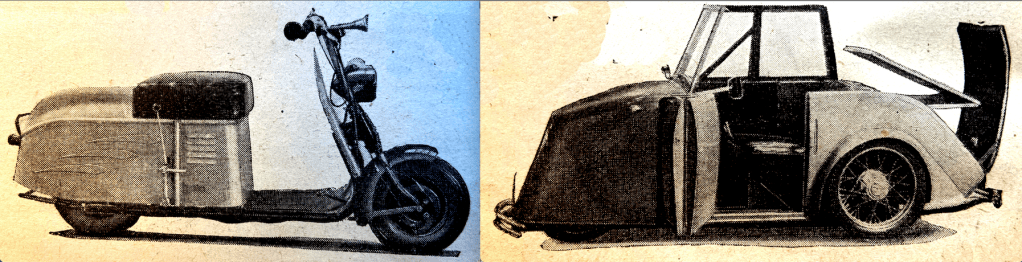

“THE 498cc VESTA UNION racing car…has a four-cylinder in-line engine. The cylinders are cast steel barrels round which are brazed the jackets for water-cooling. The head is integral with each cylinder and has four valves…set pent-roof fashion at 60°. A train of gears drives two overhead camshaft and the crankshaft is in sections bolted together. It is anticipated that with an 8 to 1 compression ratio and normal induction the power output will be 40bhp at 8000rpm. This unit, suitably modified, seems to be the type for racing motorcycles of the not-too-distant future. The supercharged four-cylinder Gilera was quite the fleetest racing machine just before the war. It is now rumoured that an unblown model is likely to make its appearance in the TT next June. If past experience is anything to go by, singles and twins will have a tough task to hold the Italian multi.”

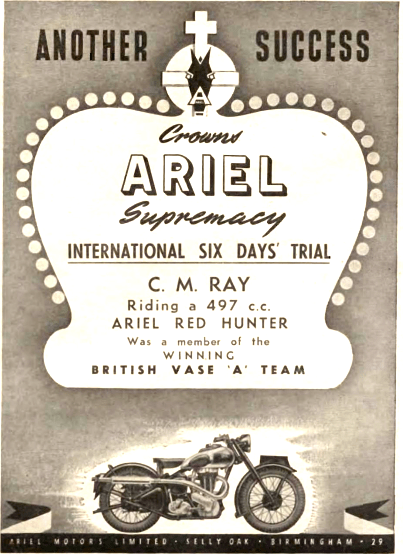

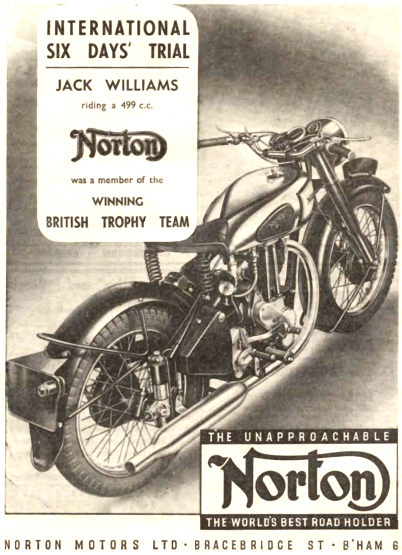

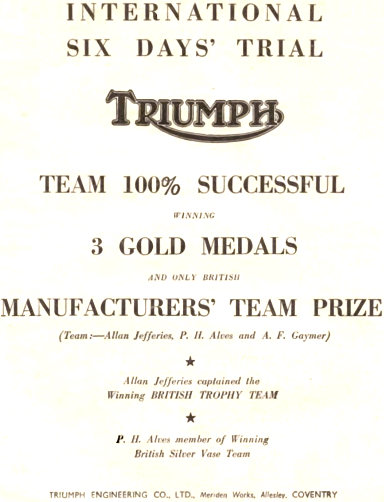

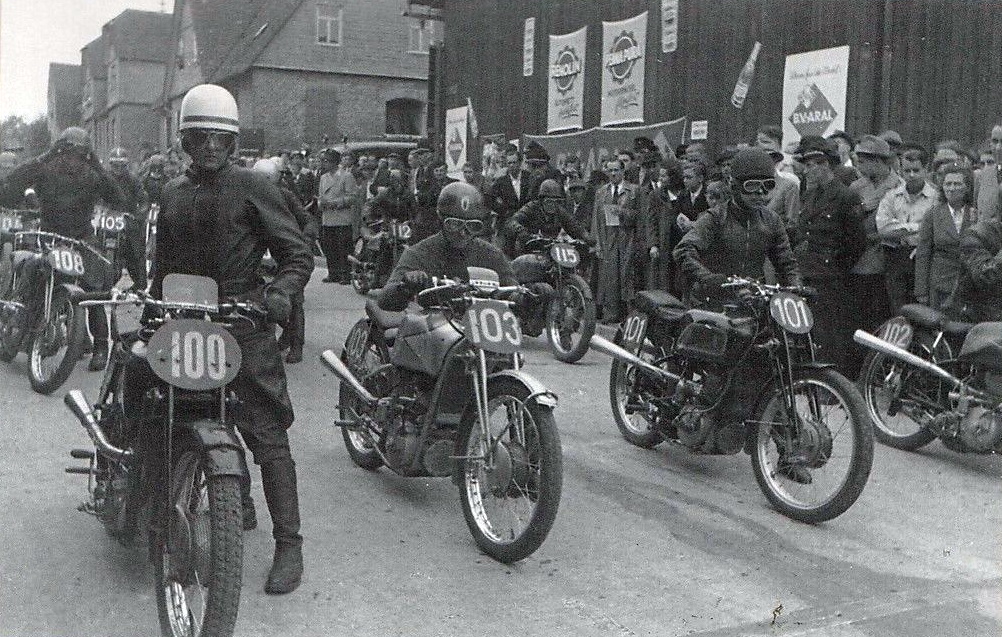

ISDT SELECTION TRIALS at Llandrindod Wells went ahead despite government restrictions on the amount of petrol issued to the ACU. The excellent ISDT website speedtracktales.com reports: “This Mid Wales location had been selected directly since many sections still remained of the 1938 ISDT which had been held there. Course plotter was Harry P Baughan, who built his own trials sidecar outfit with a Stephens motor, called The Stag…[he] had been instructed to plan a course to find weaknesses in men or machines, now bearing things like improved suspension layouts and WD-type air cleaners. Jack Stocker’s rigid frame Royal Enfield J-model seems to have been a link with the past.” The two-day trial was notable for “…neat Triumphs, plunger Ariels, alloy engined BSA, pre-Featherbed framed cammy Nortons, batteries to help lighting…KLG plugs expert Rex Mundy was present plus Dunlop tyres man Dickie Davies. Even a Manufacturer’s Union Director, Major HR Watling was prominent; the ACU’s Harry Cornwell too. Private entries included Miss Olga Kevelos (347 AJS), Australian DB Williams (498 AJS) plus a three-man BAOR team on 498 Matchlesses: Sgts A Hanson and JW Ward, plus Pte J Hall.” Selected for the Trophy were A Jefferies (498 Triumph), VN Brittain (346 Royal Enfield), CN Rogers, (346 Royal Enfield), BH Viney (498 AJS) and J Williams (499 Norton).Vase ‘A’ Team: PH Alves (498 Triumph), CM Ray (497 Ariel) and J Stocker (499 Royal Enfield). Vase ‘B’ Team: J Blackwell (499 Norton), AF Gaymer (498 Triumph), FM Rist (348 BSA). Reserves: EJ Breffitt (348 Norton), G Eighteen (498 Matchless) and TU Ellis (346 Royal Enfield). The Blue ‘Un summed it up nicely: “While there have been International Six Days’ Trials over even

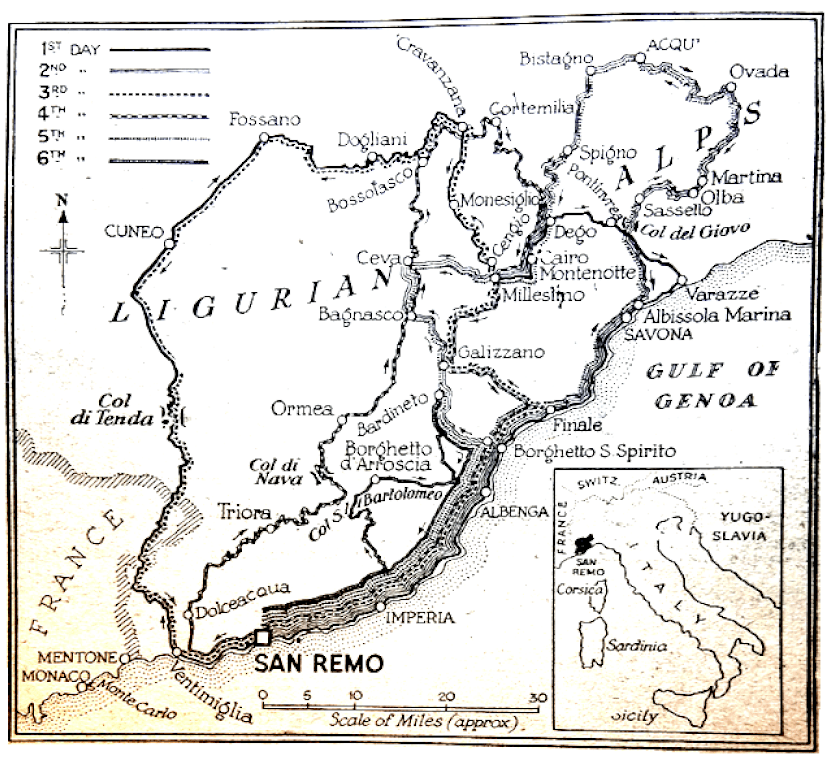

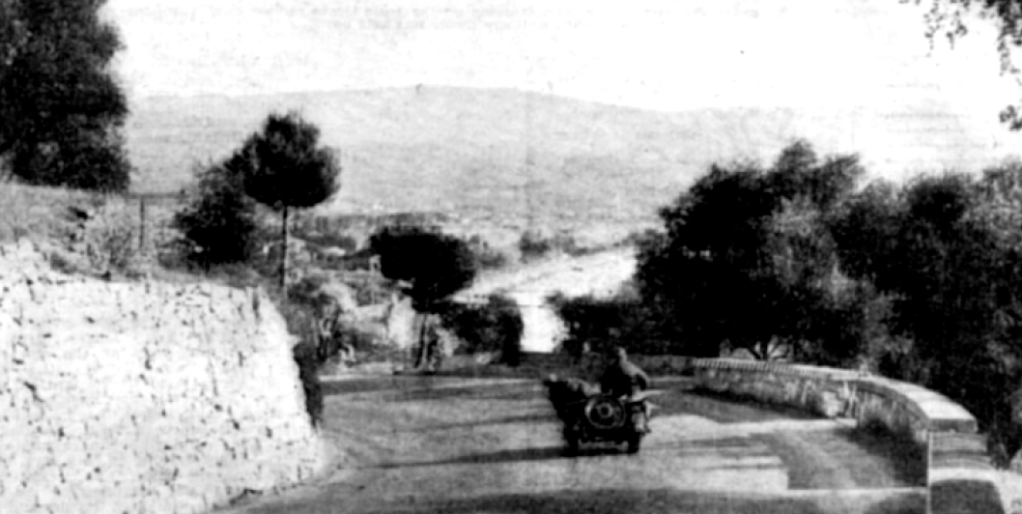

worse road surfaces than those included in the event which ended last Sunday at San Remo, there has never been a more gruelling event. The fact that 81 of the 151 who started retired during the week is a commentary in itself. Any rider who retained a clean sheet and thus gained his gold medal can be very proud of himself. Not only has he shown outstanding skill, but a high degree of courage. The maker of his machine can be proud, too, because the ‘International’ is a test of destruction—just that. What makes it so is the average speeds demanded. Even the most famous riders in the world had the utmost difficulty in achieving the time schedule. They were riding beyond the safety limit over many of the 1,272 road miles. Special congratulations go out to the British Trophy Team which, by losing no marks, won the contest among national teams easily, and to the manufacturers of their machines: A Jeffries (Triumph), CN Rogers (Royal Enfield), VN Brittain (Royal Enfield), BHM Viney (AJS) and J Williams (Norton). No fewer than seven nations competed for this coveted award. In the Silver Vase competition Britain, too, was the winner with her No 1 team which also lost no marks: PH Alves (Triumph), CM Ray (Ariel) and WJ Stocker (Royal Enfield). For this there were eight countries competing and no fewer than 15 teams. In addition a British manufacturers’ team was one of the only two of such teams to finish without loss of marks and the British Sunbeam Club gained the first and second places in the club team contest. Of the 26 Gold Medals awarded to riders who completed the course without loss of marks, 11 of those medals were won by British riders and machines. A word must be said, also, of the many who journeyed from England to help as team officials and assist our riders. Finally, congratulations to the Federazione Motociclistica Italiana whose organisation of the event, while not flawless, was extraordinarily efficient having regard to their being given the task only some four months ago.” ISDT Committee Chairman Harry Baughan kept his own record of the event. ISDT Day 1: All OK other than Jack Blackwell who lost 3 marks and the Czechs were all clear. ISDT Day 2: All start OK before lunch Jimmy Simpson appeared with George Eighteen who had

retired after a crash…also carrying Vic Brittain’s rear mudguard with broken stays reg and GB plates plus lamp assembly. Repair and refit after welding and brazing rapidly judiciously arranged. ISDT Day 3: Vic’s mudguard fixed aboard all away OK, Jack Williams reported to have bent front wheel and forks as result of running into Jim Alves’ rear end at a time check but he can keep going. ISDT Day 4: Charlie Rogers’ rear mudguard stays cracked and bracket needed to support, Blackwell retires with engine trouble, Jack Stocker’s fork broken across head stem lug, Viney, Alves, Rist, Bert Gaymer, and Allan Jefferies going well caring for their machines, Brittain comes in on a flat tyre which gets done without time loss. Czech team loses Pastika! So a clear 18 points lead for Britain emerges over Austria and Harry Baughan warns Teams to take care! ISDT Day 5: Tyres get changed, Rogers reported to have had a serious crash but he and machine do finish even if poorly, Doctor arranged plus car to hotel. Allan Jefferies sends message to Harry via Arthur Bourne to have large hammer and chisel ready when he arrives, message reached Harry 2 mins prior to Allan’s arrival and cussing of all followed whilst the bits were somehow obtained and front fork nuts removed, oil added to undamped teles. Instructions go out not to race the Czechs who have an unpenalised Club Team in the Hunt along with UK’s Sunbeam ‘A’ and Sunbeam ‘B’. ISDT Day 6: Jim Alves finds starting difficult with a slipping clutch! but gets away OK, all continues well. Jack Stocker keeps going with well wrecked forks with a nearside leg BROKEN—a clamp is fashioned to try to hold this by Jack Stocker, Bert Perrigo and Harry Baughan using a similar bike they found in San Remo as a template! Jack had to officially start then fit the clamp, Jack had two sets of leathers on throughout the speed test in case of a crash resulting! He kept going to the average speed required too. Trophy, Vase, and Club Team Contests all brought Champagne and congratulations and a Party became arranged at the Casino.” And here are some excerpts from the The Motor Cycle‘s report, courtesy of ‘Torrens’, aka the editor, Arthur Bourne: “Of the 151 who started the day’s run, only 52 ended with clean sheets and thus were still eligible for gold medals. Sixteen retired, seven finished so late that, under the rules, they were automatically out of the trial, and 66 lost marks. Put briefly and bluntly like this, and given realisation that the trial numbers in its entry many of the finest riders in the world, what other conclusions are possible than that the day had been stiff and that the International is the trial of trials? The first part of the day was a glorious coastal run on a road bordered by cactus, palms, mimosa, and geraniums, through Imperia and Alassio to Albenga.

Then the trial struck inwards towards the mountains. Down in the Riviera of Flowers the weather became sunny and even hot. In the Ligurian Alps it was very different. On the Colla di Casotto there was mist–this on a 25.4 mile stretch which all machines over 250cc had to cover in 50 minutes. Twists, turns, up to 5,500 feet from 1900, down to 2,670, up again, down to 1,450 and mist. Worse still, there was 1½–2 miles of Colmore-like mud: rutted, puddingy stuff. The British team men shot through it at 30mph with one foot out every now and then for safety’s sake. They were riding on the danger line. One toss and they would almost certainly be late at the next check. Also, their machines might be damaged. The Italians, magnificent in the loose, were unhappy in the mud. Lunch, indicated by a fork and spoon on the route card, consisted of three rolls, meat, cheese and fruit in a paper bag, and wine or beer, as the individual preferred. But assuredly it was not the lunch that caused so many, shortly afterwards, to run slap into another relic of Sunday’s great storm. There was some 25 yards of 4in-deep flood-water which looked precisely like the rest of the road. What a day! It began with a 40.6-mile circular tour (!) to the north of San Remo. For this the biggest machines were allowed 1hr 19min, which meant driving on the danger line throughout. Many riders decided that there was no alternative to being late at the check. There were five miles of fast going to Bordighera and then immediately the competitors were on rough, trysting roads that climbed and climbed. Hairpin bend followed hairpin bend, bringing one nearer to a village pinnacled, it seemed, in the sky. Here at Perinaldo there was a rough climb—rocks, earth, a drop on the right—lined by hundreds of cheering villagers. it was sufficiently steep to cause N Biasci (125 Vespa) to get off and run beside his machine. The climb was very similar to some of the hills around Cheshire included in the ACU’s 1925 International. As for what followed there was real Exmore-like track, except that Exmoor does not boast sheer unguarded drops at her roadside. Ugh! The 29.2 miles from Pieve di Teco to Molini di Triora, which machines over 250cc had to cover in 58 minutes, can be described at such a schedule, as being close to madness. As on so much of the International, speeds convey very little—unless one has actually traversed the stretches. Even the fact that on these 29.2 miles there was a climb from 700 feet to 4,000 feet followed by a drop and another climb failed to give an adequate picture. But when it is mentioned that in 5½ miles of zigzag ascent there are 176 hairpin bends, some semblance of an idea is gained that a 30mph average can be almost suicidal. The track was narrow in places; sometimes it was muddy; often there was deep loose stone and at point after point there was a sheer unguarded drop on the left. As Alan Jeffries remarked concerning these frightening stretches, there is no return ticket. Harold Taylor (Vincent-HRD sc) used different words: he said he had never felt closer to Kingdom Come. Riding to schedule

meant riding as hard as humanly possible—brakes, acceleration, sliding bends, applying every trick of the trade and, almost needless to say, thrashing machines unmercifully. The aim of the international was being achieved, but at very considerable risk to the riders. The 250cc machines with their lightness and their lower speed schedule—an additional five minutes —were undoubtedly much better off than the 350s and 500s on such going. However, all Britain’s trophy team and her Silver Vase teams won through. A sad blow was that Ron Watson (Ariel sc) who had not lost a single mark up to this point, one of only three sidecar men to achieve this, had a retire two-thirds of the way through the section owing to a sheared sidecar-wheel spindle sleeve. Another sidecar man, Dr Galloway (Triumph), was out, and so was Capt Beatham of the BAOR, whose clutch was revolving idly on its shaft, the splines having sheared. Of the 151 who had started the trial 114 was still running on the third day and, of these, nearly 46 were unpenalised and, therefore, still eligible for their Gold Medals…British machines were certainly keeping the old flag flying. Incidentally, RJ Harris (500 BSA) was the one British private entry with a clean sheet. The day ended with Czechoslovakia and Britain still equal and leading in the Trophy competition. There were also two teams unpenalised in the Silver Vase contest. These were Holland number 1 and Britain number 1. Fourteen further competitors retired leaving, 96 still running. Over one third of the entry dropped out in the first three days. The nearly three-hours long cavalcade set off in its twos and, owing to retirement, sometime ones, from the starting point at Osnedaletti, with the first, as usual, signalled out at 6am, British time, just before dawn. It was more like sunset than dawn. The sun peeped up above the sea tingeing the clouds and the Mediterranean with all the colours of the rainbow. No picture postcard was ever more colourful. Whether this forecast a good day or a bad one was a matter for the locals. It was certainly a bad day for the Czechoslovak Trophy team which was running level with Britain. At the very first check J Pastika (125 CZ) retired, apparently with gearbox trouble. This meant 100 marks automatically lost for the day, and for each succeeding day, so if only Britain and, in particular, Jack Williams with his damage Norton, could keep going, all should be well…Saturday’s run was more a matter of mileage than of great difficulty. There

were 245 miles to be covered, with nearly 30 of them on the coast road. But with the heat, the dust, and still further hammering of tired bodies, it was very far from a picnic. The one really vile portion was a stretch of some six miles near Monesiglio—hairpin bends roughly 15 yards apart and the road surfaced with what seemed to be cricket balls made of stone. And just before Albenga and the final run home there were downhill hairpins that appeared to be numbered in millions. As one competitor remarked, on this stretch one looked down the chimneys of villages far below and, with glasses, could have seen what the villages were cooking. The day was a worrying one for Britain. Paul Stocker was in trouble with a front fork bridge. Ray found the heat overpowering; like many others, he started to feel sleepy and, cutting things too fine, bent to footrest and his brake pedal in a near miss with a lorry. Cunningham, charging through a crowd, found a car head-on coming from the reverse direction, hit the car so hard that it was turned round and, although writing off his AJS, miraculously was himself unharmed. Worse still, particularly as the British Trophy Team was still leading, Charlie Rogers took a very heavy toss. Cruising at 50mph with hardly a care in the world he shot into a mud patch. There was an unseen hump in it. Machine and rider shot into the air cleared a typically low wall of about 1ft 6in, and ended in a field, where Charlie passed out for a bit. By great good fortune the machine was all right. After a while he carried on and kept to time. At Albenga he all but fainted, and Red Cross nurses plied him with wet sponges and brandy. Such are his guts that he got through to the finish still on time. Breffitt hit the same bump but was luckier…Jack Williams was continuing to nurse his bent machine successfully, but had a nasty gash on his front cover. More work to be done before the final check. Hugh Viny, who spent his spare minutes at Albenga in checking over his machine, found out what was causing the noise that had been worrying him for miles. The front brake cable, with taped up spare, was tapping the back of his headlamp! Incidentally, everyone was now used to the fact that many of the insects at the roadside make a horrid sort of noise suggestive of machine trouble. DB Williams, all the way from Australia and putting up a stout show, allege that his bag to date was two chickens, three cats and one Italian. Frequently in the mountains, villages will be seen watching the trial with the hand safely under each arm. Another who was impressing all was a private owner of an ohc

Norton, RW Tamplin. This was the last and perhaps most dramatic day. What of Charlie Rogers, of Jack Williams’ machine and, in the Vase competition, Jack Stocker’s? Would Alan Jeffries machine handle all right now he had added oil to each fork leg? On the 53.5 miles that were to precede the speed test? A portion of the roots was marked on the official maps—there was no road shown… Rogers was not in good shape but was carrying on. Harold Taylor (Vincent HRD sc) had tummy trouble, a second bout, and had been up all night but was equally determined to have a crack at finishing. The start was at 6:30am (4.30 GMT) in the twilight. There were all the fresh smells of dawn: very different smells from those at home. It was near Radalucco that the bad stretch began—10½ miles of continuous climbing with the road swinging around mountain after mountain, ever upwards. On the left on stretch after stretch there was merely eternity—no wall, but a sheer drop. Go over the edge and unless you were very very lucky you were a ‘gonner’. TU Ellis did go over but landed on a tiny patch of grass, the only patch there was anywhere around….Rist pulled the nail out of his rear tire and was relieved to find that the Dunlop puncture seal caulked the hole…He said gratefully, ‘That’s wonderful stuff, isn’t it?’ Charlie Rogers came in on time, a magnificent show…Harold Taylor looked done in, as well as he might. Then a police jeep arrived with Decat (350 FN), of the Belgian trophy team. Hardly had the car gone than No 34 free-wheeled into the control with his jacket off—E Beranek (125 Puch), of the Austrian Trophy team, the team was second of Britain…Beranek’s rear chain and chain wheel were adrift on the hub. The trial was far from over. There followed 7.1 miles downhill with unguarded precipices for what seems to be nearly the whole way. Yes, downhill. The road surface? It was smoothish but dusty, loose waterbound macadam. Ugh! And then there was the Peraldo stretch again and still more—many more—but safer downhill hairpins. It was on this that Stocker had a fork leg come adrift and held only by juryrigging, yet he finished on time and was complete the speed test. What dauntless courage! You should have heard how the other riders cheered him at the presentation that night. The British riders all went through to the finish of the road section. Since both the

British Trophy and No a Vase teams and lost no marks and all other nations had lost marks there was no question of the speed test being turned into a race, each team striving for bonus marks. It was a matter of keeping going—of trying to keep going—and that, as related, Stocker did, so did Rogers, and so did the only British sidecar driver still in, Harold Taylor, one of only three sidecar men to win through. Harold finished and, on stopping his machine, fainted. Foreign riders around him instantly lifted him to the pathway and he soon came round. And the greatest of all trials ended with Britain gaining all the cherished awards. Mr Nortier, of Holland, when making the awards in the great ballroom at the San Remo Casino that evening, said, ‘You may have thought after the Grand Prix of Europe that British supremacy was over; it is very far from being so.’ Special cups were presented by count Lurani to the Trophy and Vase team members; to Mazzoncini, who, for four days, lost no marks on his 125cc Vespa scooter; to Barrington, who so gallantly finished the fourth day unpenalised in spite of a fractured shoulder; and to Miss Kevelos, who had ridden from England and, the one lady in the trial, carried on until outed by a tumble.” RESULTS International Trophy: 1, England, 0 penalty points; 2, Austria, 125; 3, Czechoslovakia, 500; 4, Italy, 904; 5, Netherlands, 1,014; 6, Belgium, 1,148; 7, Hungary, 2,517. Silver Vase: 1, England ‘A’, 0; 2, Czechoslovakia ‘A’, 2; 3, Netherlands ‘A’, 16; 4, England ‘B’, 320; 6, Hungary, 338; 7, Switzerland ‘B’, 399; 8, Switzerland ‘A’, 516; 9, Hungary ‘B’, 614; 10, Italy ‘B’, 625; 11, Belgium ‘A’, 946; 12, Italy ‘A’, 1,916. FMI Trophy (manufacturer’s team award): 1, Jawa ‘B’ (Czechoslovakia) 250cc; 2, Triumph (England) 500cc; 3, Royal Enfield (England) 350cc; 4, Jawa ‘B’ (Czechoslovakia) 250cc; 5, Gilera (Italy) 250cc.

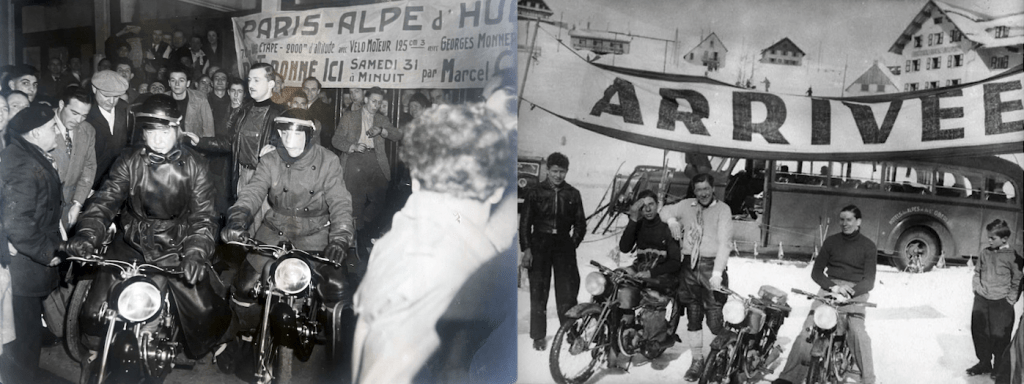

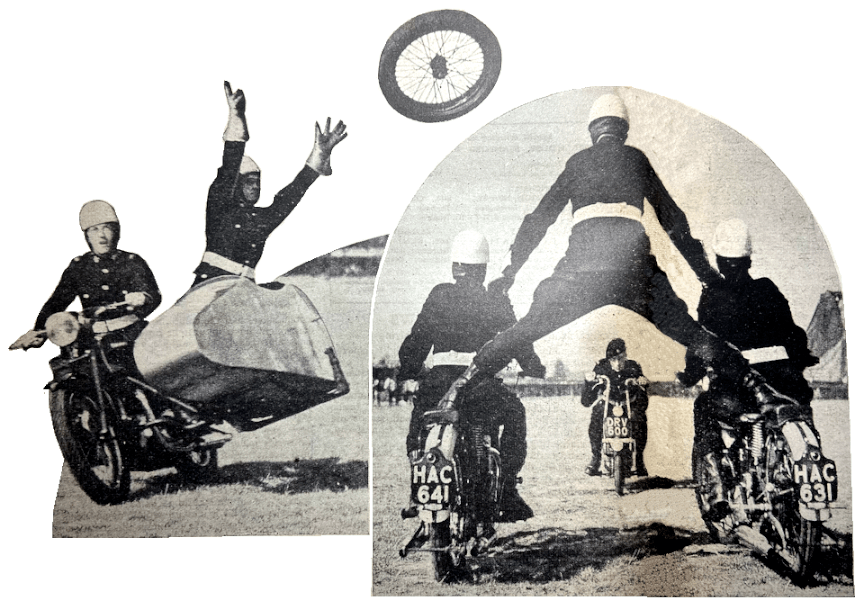

Motor cycle competition was flourishing all over post-war Europe…

THE LETTER IN OUR Correspondence columns from Professor Low comes at an opportune time. Professor Low suggests that as we do not yet know as much as is desirable about supercharging, it is necessary that the testing opportunities afforded by the Tourist Trophy and other races should be used to gain more experience. It is, of course, not impossible that the development of the gas turbine may reduce discussion of piston-engine development down to the academic level in a few years time. Meanwhile, however, nothing should bar the intensive improvement of the type of engine with which we are familiar to-day. In pre-war days, superchargers were permitted in international motor cycle races, and by 1939 multi-cylinder engines with forced induction were making the pace in the classic events. With the start of racing after the war, the FICM decided to ban superchargers and to make the use of commercial fuel compulsory. In 1946, when the decision was made, conditions were such that both rules were in the interests of getting racing under way again. The war years had made it difficult to develop new designs—hence the predominance of pre-war designs in the races of to-day—and, at least so far as Britain was concerned, only commercial fuel was available. It would seem that the time has arrived for further thought to be given to these rules. If racing is to serve its full purpose, development must be given reign and as much knowledge as possible gleaned therefrom. Those who are critical of supercharging on the score that it will entail still greater divergence between racing and the ordinary man-in-the-street models will at least have the satisfaction of knowing that supercharging spells multis. Permitting super-chargers in races may in the long run have a good effect on standard design. Some new racing engines are in the drawing board stage, and others are in the initial prototype form. Designers require to know well ahead the broad rules under which racing will be conducted in the future. It was thought that at the Spring Congress the FICM might give some intimation of the feelings of the represented nations on the question. This did not materialise. Undoubtedly, therefore, the subject should be considered at the Autumn Congress which it is anticipated will be held in London. A lead from the FICM that the banning of superchargers and the insistence on commercial fuel in international racing will be lifted for events in, say, 1950, will do much to help along the plans of technicians. It is, of course, imperative that the rules should not be altered without fairly lengthy notice.”

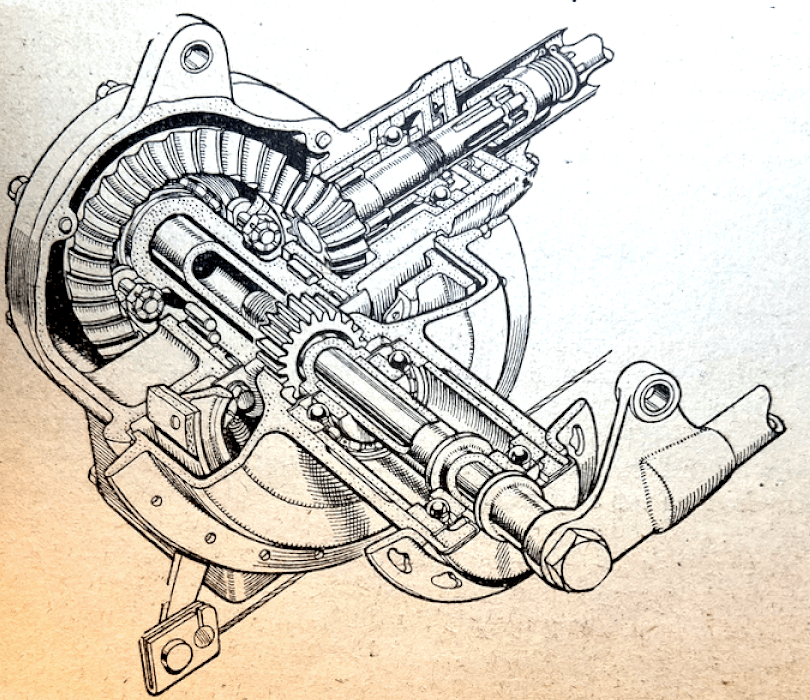

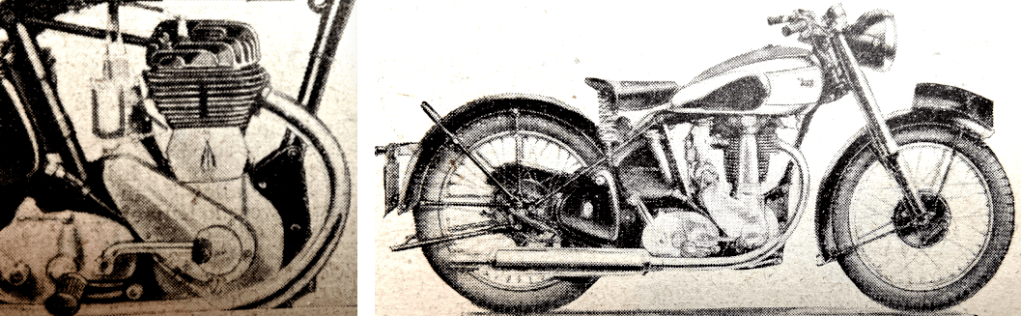

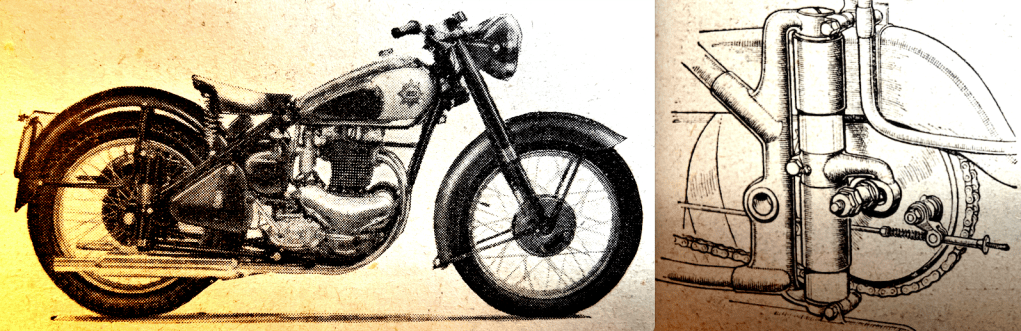

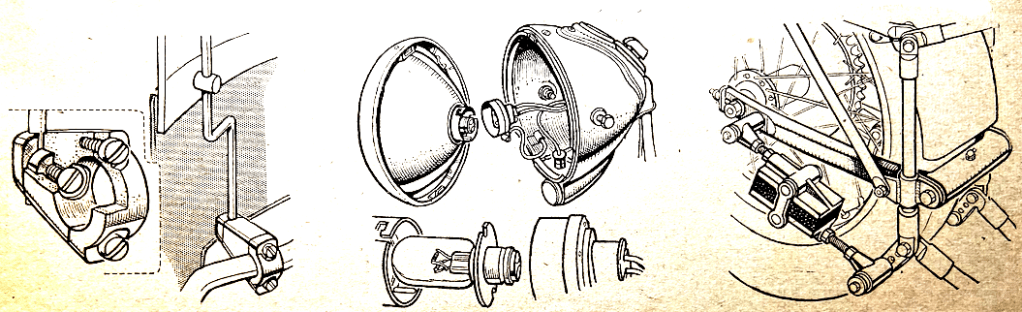

“SEVERAL DETAIL MODIFICATIONS have been carried out on the AJS twin-cylinder racers. Nothing drastic or revolutionary has been attempted, bus a good deal of thought is obviously behind the changes that have taken place. These changes apply to all four machines (there is now a fourth which is a spare). A completely new rear hub assembly is fitted. The two-bolt form of brake anchorage used last year has been replaced by a long Duralumin rod, bolted at the forward end to the chain stay. For the anchor-plate end fixing a ⅜in diameter bolt passes through the anchor plate from the inside. The bolt has a large, flat head which is secured by a series of Allan screws. The rear chain sprocket is drilled for tight-ness. The weight saving, it is claimed, is over 31b. The reduction in size of the chain sprocket (which, of course, raises the gearing) is permissible because of engine modifications which are, as yet, undisclosed. A new and simpler form of rear brake pedal has also been fitted. A new finned oil-filter, which is turned from solid Duralumin, is anodised and dyed black. The oil-tank is similarly treated. A new-type Lucas racing magneto is employed.”

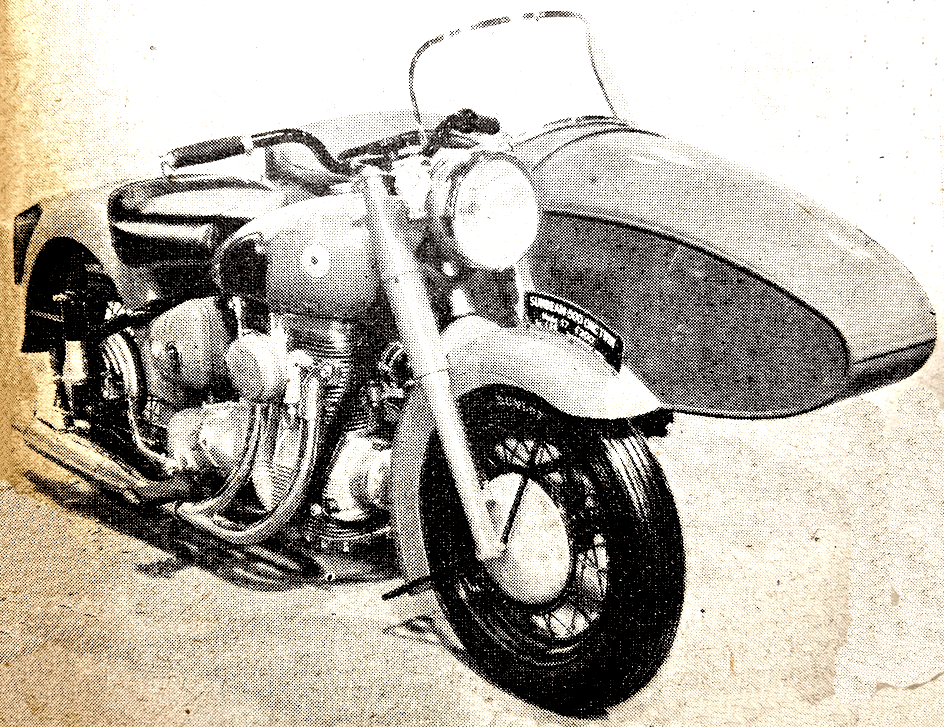

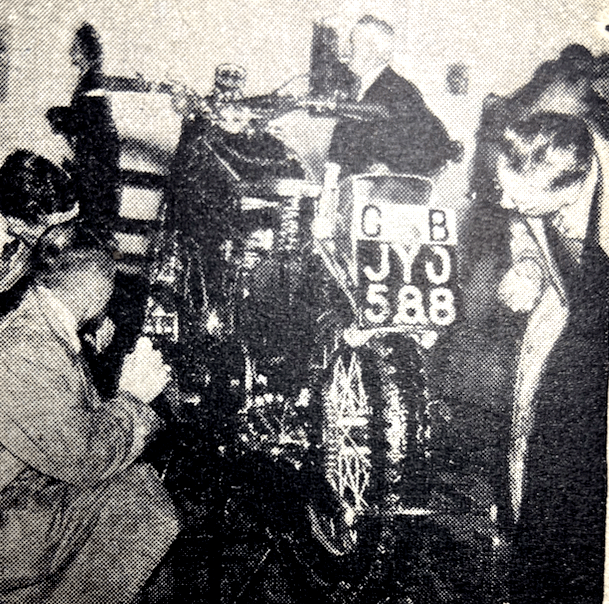

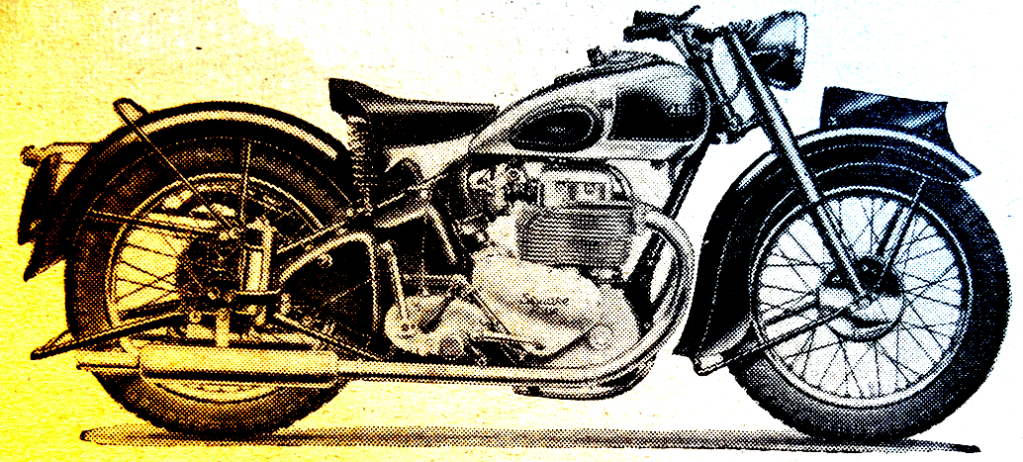

“LAST WEEK’S VISIT to the BSA works by 43 journalists representing the press of the world coincided by chance with a visit of Mr E Friar, Secretary of the AA. Mr Friar was officially taking delivery of the 1,000th postwar sidecar outfit made by BSA. About 60 shining yellow road patrol outfits lined the route from the police gate to the offices. It was an impressive site for the 43 world’s newspaper representatives, among them was a Russian from the TASS agency.”

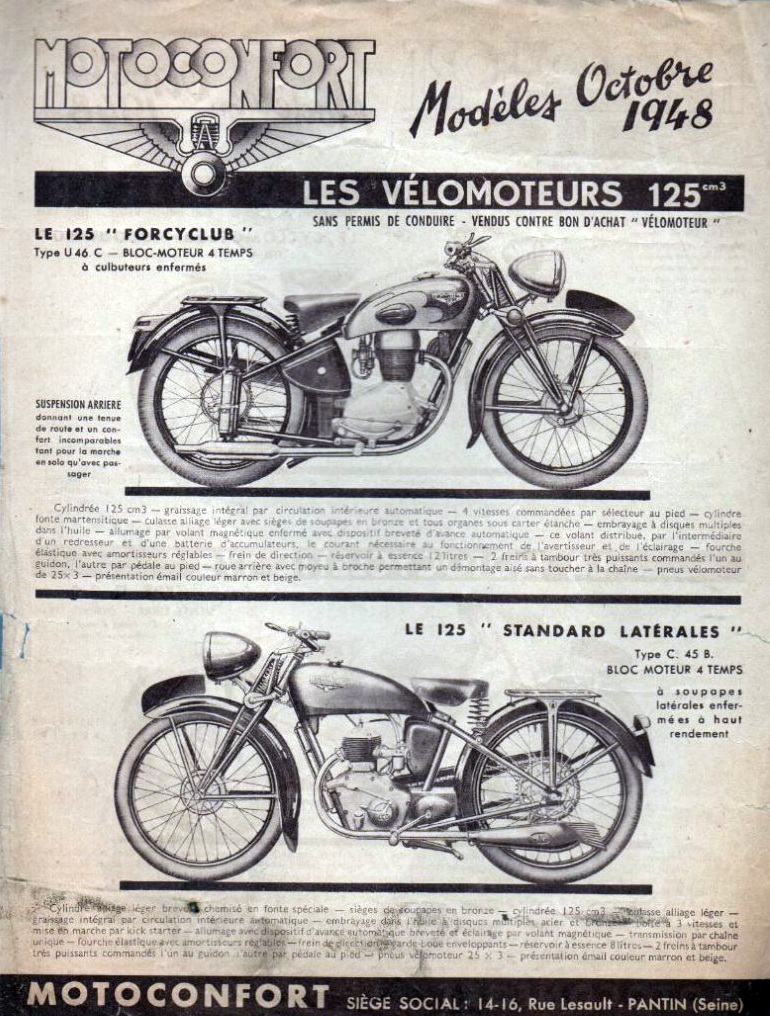

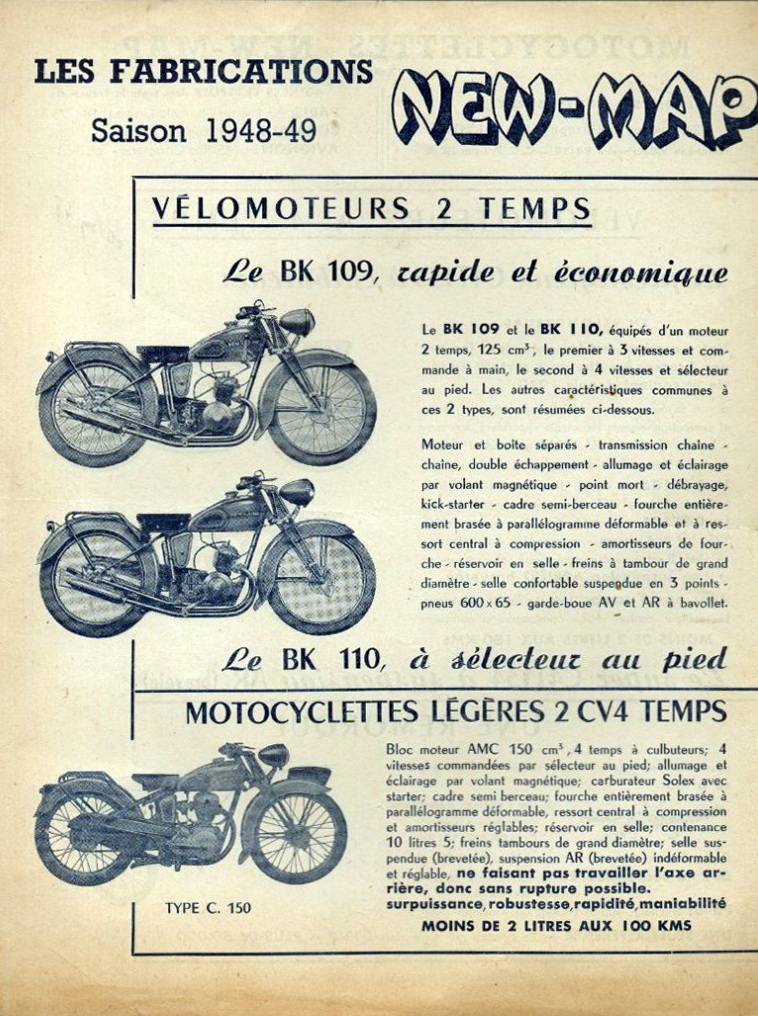

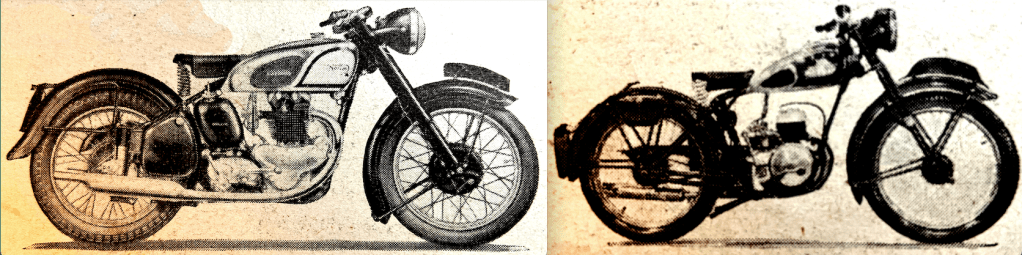

DURING THE WAR occupied France had no use for big bikes and that set a pattern that affected the peacetime industry. Of 21 manufacturers only five made anything over 125cc.

“A CROWD OF NEARLY 3,000 watched exciting sport during last Sunday’s Mortimer Scramble open to Southern Centre riders. The course was slightly over half a mile a lap. It included a very fast straight and two boggy patches which got deeper and more difficult as the programme progressed. Star of the meeting was WJ Stocker, who was again trying out rear springing on his Ariel. He won the unlimited cc and ‘fastest eight’ races.”

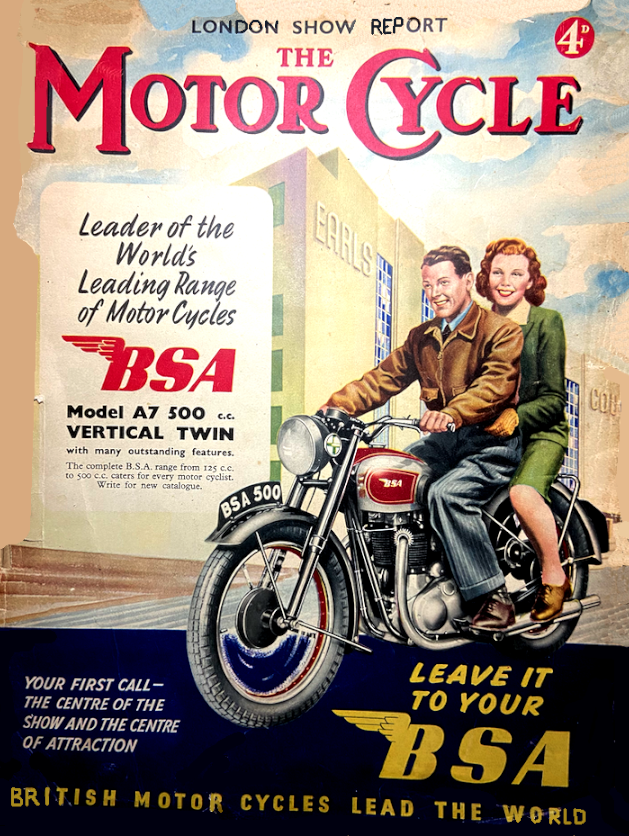

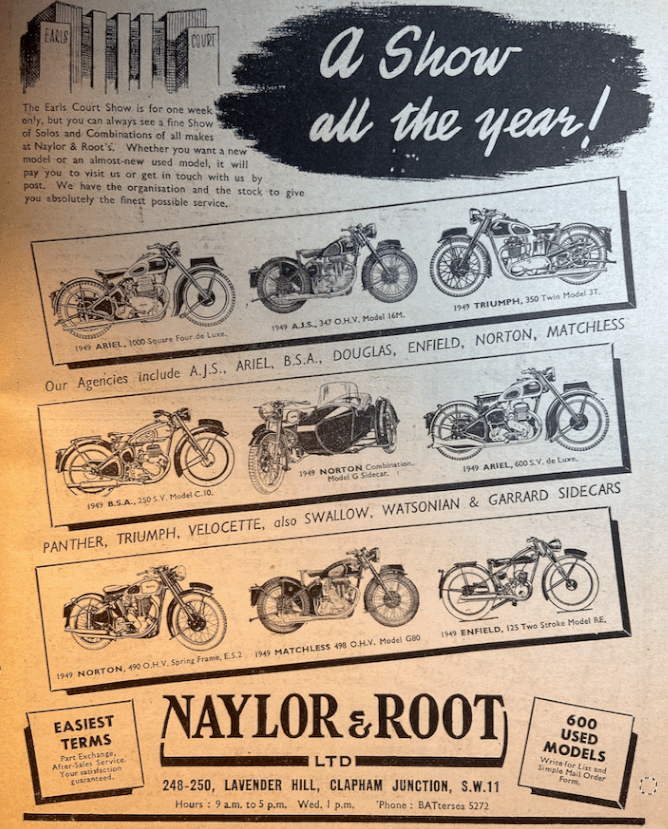

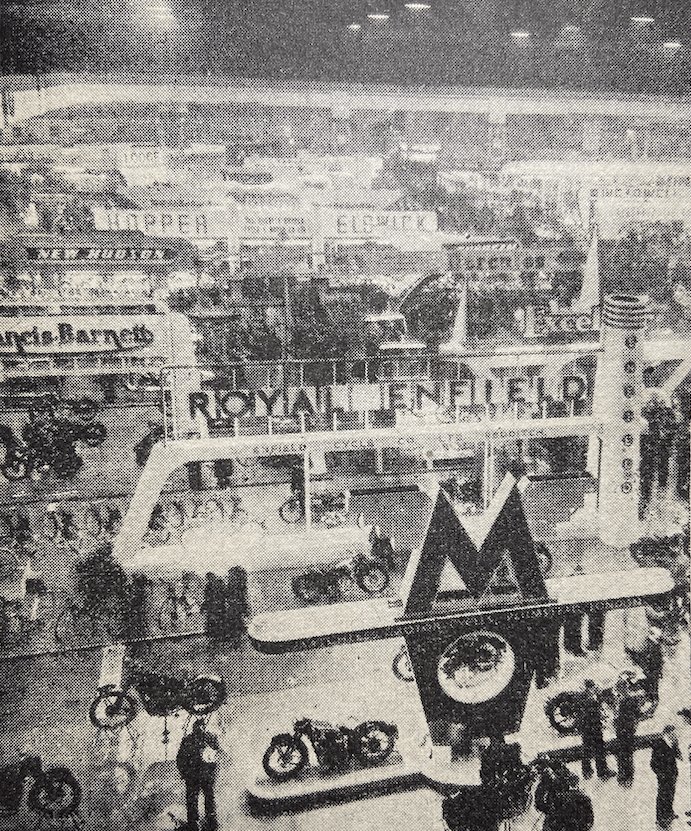

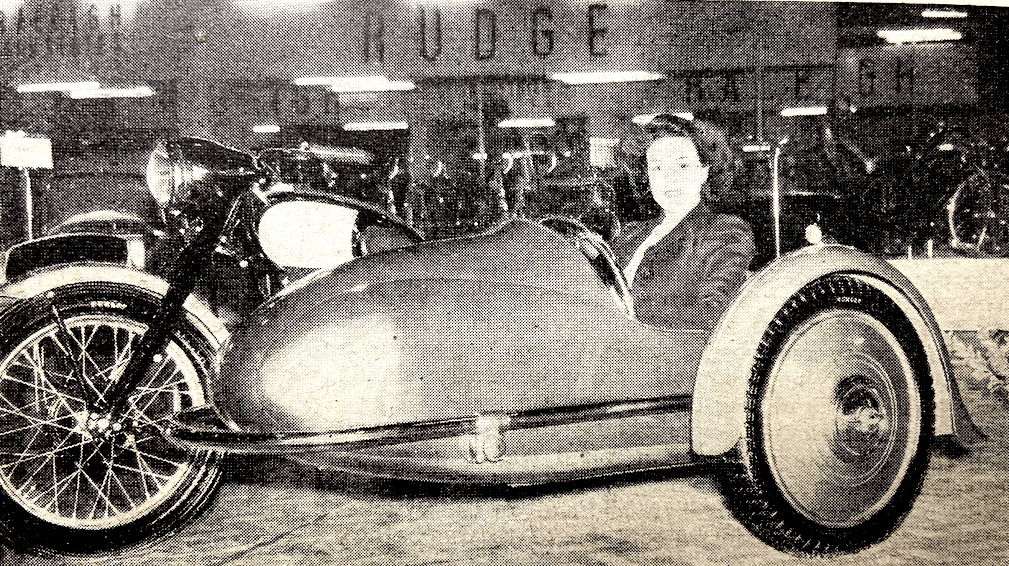

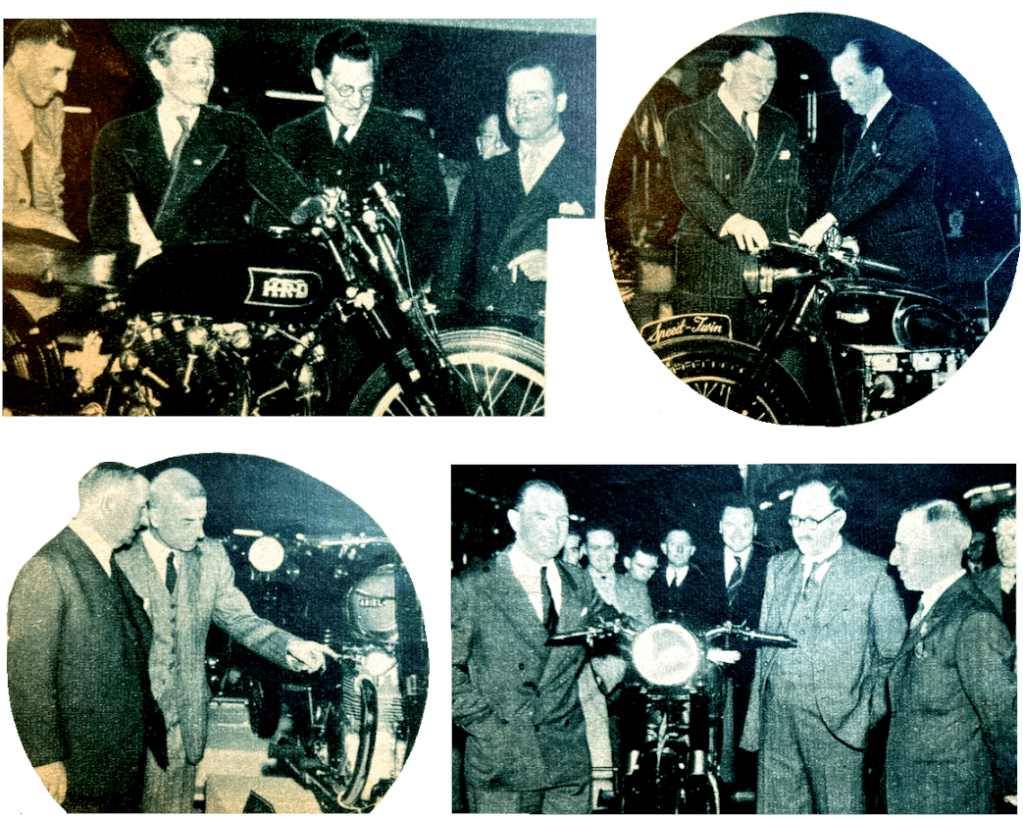

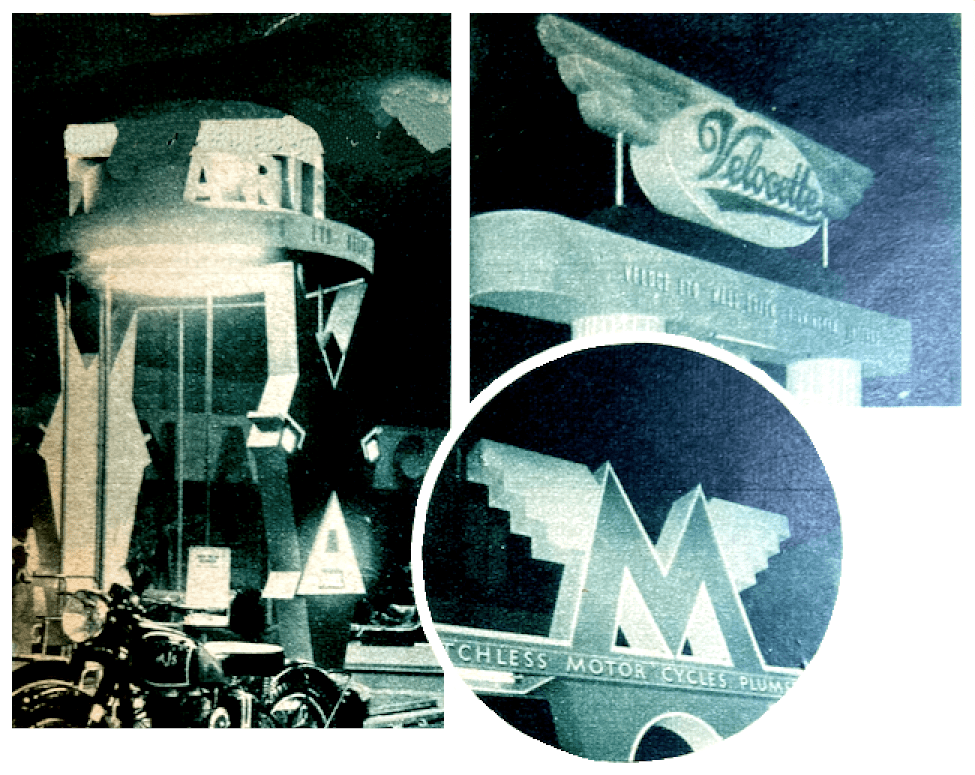

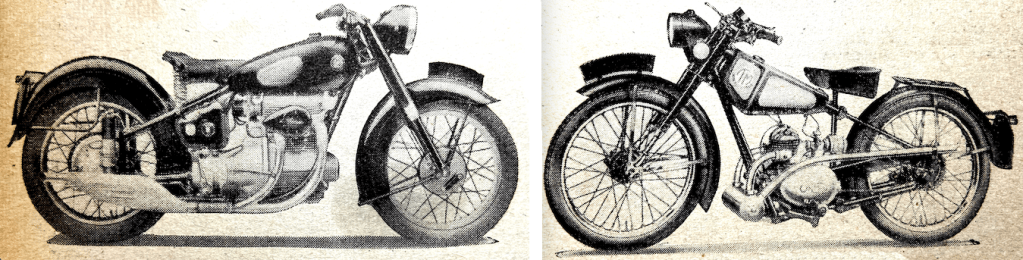

“A SHOW OF SHOWS—Scintillating, Fascinating and Satisfying. The London Show which ended last night achieved much more than merely attendance records. If ever there was a motor cycle exhibition that enheartened, thrilled and satisfied, it was Earls Court of the past week. Right from the turnstiles starting to click last Thursday morning, it was obvious that here was the Show. Inside the great exhibition hall was a variety in both stands and exhibits, and to eyes and minds accustomed to austerity, what a scintillating display! With many enthusiasts, anticipation dated back to war years, to nights in desert, in jungle, or, maybe, fire-watching in Liverpool or London. What thoughts the words ‘The next Show’ conjured up. Realisation, for once, has proved even greater than anticipation. In every sense it has been a great exhibition: in the attendances it has drawn (over 70,000 on the Saturday), the excellence of the latest designs, the variety of types, and in the craftsmanship and finish that were such notable attributes of the exhibits. The Show has revealed that British and best is not just a slogan, but a fact. Of course, a raison d’être of the Manufacturers’ Union’s mighty display is to provide a ‘shop window’—to focus attention on its members’ products and attract buyers, in these days mainly from abroad. Actually, much of the business is negotiated in advance of the Show, but few enthusiasts can have walked around the great hall without noticing many obvious visitors from countries oversea. Considerable unheralded business has resulted. By ill fortune the exhibition coincided with a period of ‘big’ news in the journalistic sense which usurped much of the space in the newsprint-starved daily and evening papers of this country, and prevented the Show receiving the publicity it merited. Nevertheless, the attendances were even greater than many expected, and the thousands who visited the exhibition, unlike those at the recent automobile show, had the comfortable knowledge that, though they might have to wait in order to obtain a particular make and model, they could buy and enjoy a new motor cycle.”

“WHEN OPENING THE London Show, Field Marshal the Viscount Montgomery of Alamein praised highly the motor cycle and cycle industry. He referred to the industry’s splendid contribution to national recovery by its high level of exports, to the excellent standard of workmanship and design embodied in the products, and went on to assert that the nation can be proud of one of the few United Kingdom industries which is recognised throughout the world to be supreme in its particular sphere. Self-satisfaction is a characteristic never strongly evinced among the British. We maintain the tradition of cautious reserve about our own achievements. We are quick to recognise the success of others, while grudging ourselves the slightest liberty in congratulation. It is therefore appropriate that praise for the industry should come from so distinguished a source, a soldier of illustrious achievement, whose profession is highly specialised and ‘remote’ and has no direct connections with commerce and politics. Why praise and even self-congratulation are justified can he stated simply. In 1947 55,367 British motor cycles valued at £4,395,542 were exported in spite of the post-war production difficulties. Our nearest competitor was the USA with 10,159 machines valued at £969,598. British machines are easily supreme in competitive events—witness the results of the classic international road races and the great International Six Days’ Trial. For 1949, British manufacturers offer such a wide range of types of first-class machines that the ranges of other nations do not bear direct comparison. A quiet toast to the industry would certainly not be out of place.”

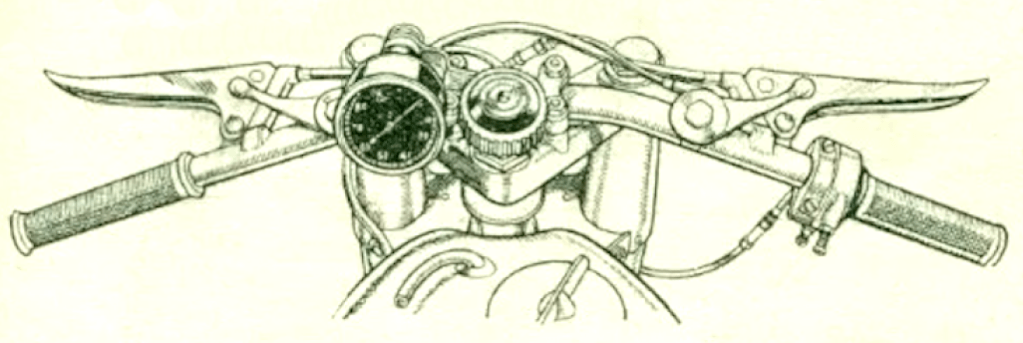

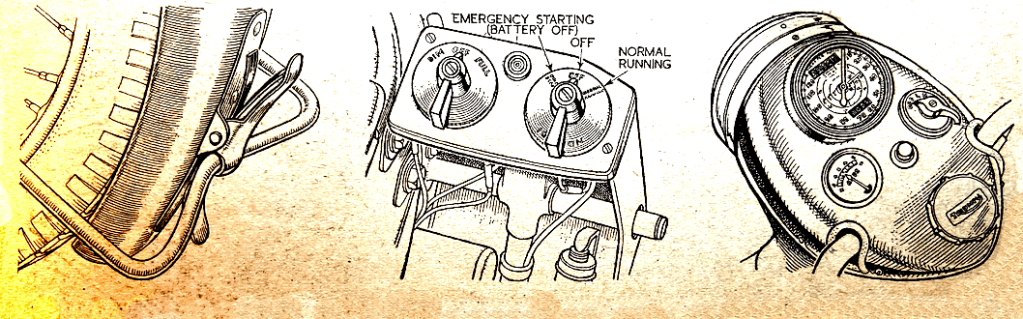

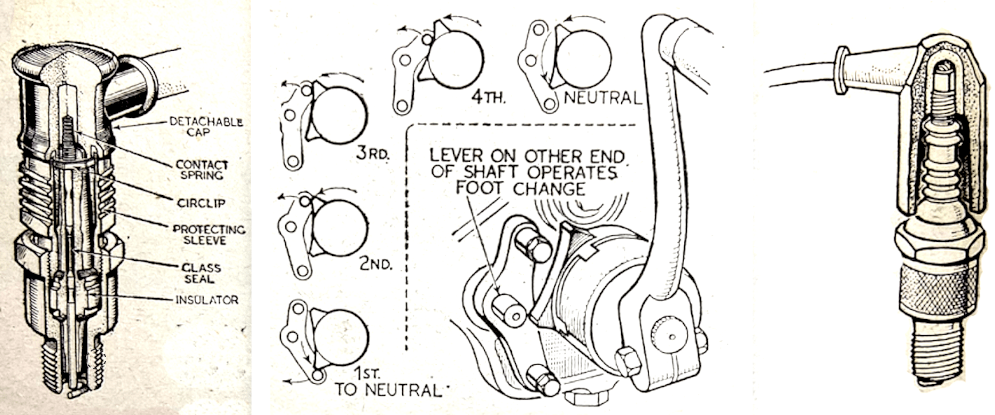

“STUDYING THE NEW VELOCETTE makes me realise how far we have travelled in simplifying motor cycle controls. We shall never know to what extent a horde of spiky levers has scared women and oldish men from joining our ranks. I can recall a day when my earlier machines had three chess bishops mounted on the top tube, a tank float control, a twist-grip ignition switch, an electric interrupter block, a valve-lifter and a couple of brake levers. In time were added a lamp switch, a horn switch and a dipper! Quite a formidable forest to non-mechanical minds, ignorant of the elements of the i/c engine. As the Show reminded us, on modern machine there may not be an air lever, an automatic ignition control is, perhaps, fitted and maybe there will be no valve-lifter. Such design reduces engine controls to the twist-grip throttle once the machine is in motion, plus, maybe, an ignition switch and a choke for starting up. The novice has next to nothing to learn. I have taught a number of novices who actually prefer our controls to car controls. Most of them fall swiftly in love with the manual front-brake control, which is always literally ‘to hand’.”—Ixion

“AN INNOVATION IS AN engine which is not only practically inaudible to others but even to the rider himself. A few years ago, when serious traffic congestion was limited to big urban centres, such inaudibility was both a nuisance and a peril. Folk based their awareness of traffic by ear rather than by eye. This had the result that anyone driving a quiet car had to make much use of the horn, failing which pedestrians seemed.to be bent on suicide. Even to-day most of our pedestrians have many more narrow escapes from being bowled over by pedal cycles than by motor vehicles. However, modern congestion is so formidable that we are all being educated to relying on our eyes more than our ears. Therefore, I doubt if a reasonably silent motor cycle can any longer rank as dangerous. But it is just possible that within a year or so we shall hear clamour for an instrument-panel device to tell us whether our engines are running or not because noisier traffic drowns the quiet breathing of a well-throttled twin. Astonished pedestrians have recently inquired whether a certain motor cycle is propelled by electricity or steam!” —Ixion

“I SPEND a lot of time nowadays in the effort to reconcile startled old-timers to the prices of modern motor cycles. At the moment three temporary and transient factors have steepled all our costs, namely, inflation, purchase tax and the compulsory limitation of home sales by the Government. (In any industry a main basis of cheap products is a large home market—which explains why in normal times American cars are so much cheaper than our own.) When those three passing handicaps go by the board, we shall unquestionably see motor cycle prices heavily slashed. In the interim thoughtless enthusiasts resent being asked to pay up to £250 for a high-class motor cycle. They compare this figure with those of 1938, when there was no inflation, no limitation of home sales and no purchase tax. They ought, of course, to compare such prices with the current prices of non-subsidised commodities, such as beer or Harris tweed. I have just bought myself a jacket and-waistcoat of Harris tweed, plus grey flannel slacks. In 1938 I could have bought this outfit for about £8 from a tailor of medium standing. The flannel trousers would have cost me 2Is. To-day the flannel trousers alone cost me £6 6s! On a similar scale a typical £50 1938 motor bicYcle might well be listed at £300. Certain special commodities display a far worse jump. I can remember being sent to buy my father a bottle of whisky at 3s 6d. To-day it costs nearly ten times as much. In 1938 an autocycle cost-round about £19 I9s. To-day its price is thrice as much. But the industry are not profiteering. We can only hope that the inevitable reductions will come as quickly as they did after the first World War and prices drop similarly. For simple minds the puzzle is not eased by the fact that subsidised foods are not a great deal more costly than they were (unsubsidised) in 1938.”—Ixion

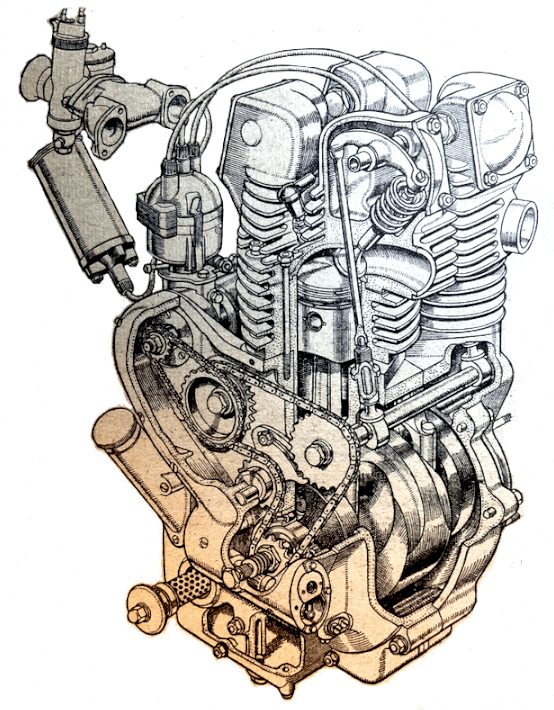

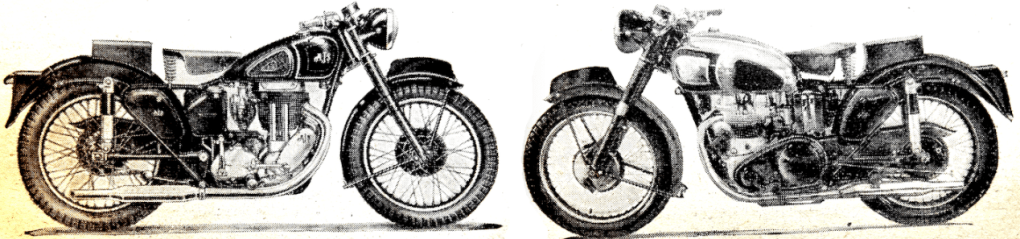

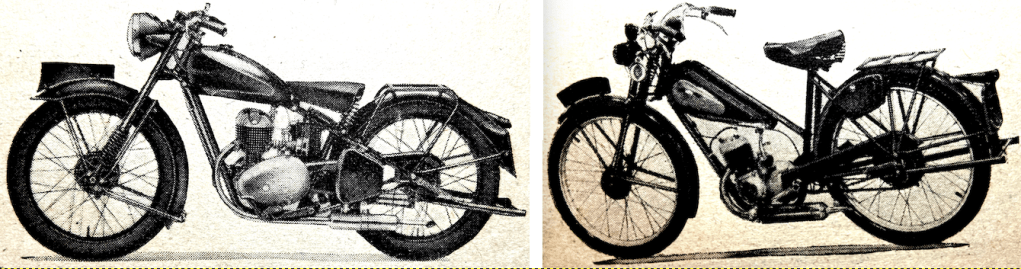

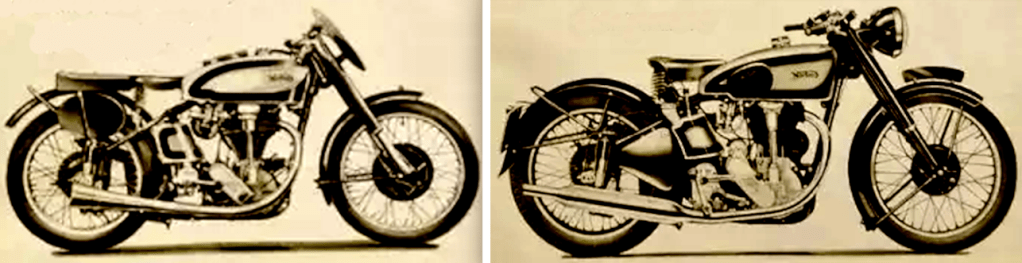

“EVERY BIG MANUFACTURER marketing motor cycles in the larger-capacity classes has a vertical-twin in his range. Thus, 1949 marks at least one major and outstanding development in motor cycle evolution. Eight makes of vertical-twin are available. Seven of these machines are of 500cc capacity only, and the last (though first in the field) is produced in both 350 and 500cc sizes. Since these manufacturers together produce each year a very high proportion of the total of British machines made, there must be important reasons for this marked trend which, incidentally, was forecast before the war and, even discounting the war years, has taken a considerable time to mature. These reasons illustrate compromise rather than technical idealism; compromise with the notorious conservatism of motor cyclists, with the high expense of pioneering, and with production costs. Students of design will propound the advantages of horizontally opposed twins, will say the in-line three-cylinder is approaching the ideal, and so on. But experience has taught manufacturers that the average motor cyclist approves conventional appearance, and he shows, by his orders, that he prefers steady progress to unorthodoxy. The vertical-twin with the crankshaft set across the frame (and all except one design have this arrangement) has an appearance very similar to the single to which motor cyclists have been accustomed for many, many years. Relatively few alterations are necessary to frame and transmission designed for a single-cylinder machine in order to

accommodate a vertical-twin with lateral crankshaft. Hence development and re-tooling can be concerned almost solely with the power unit—a considerable saving over the cost of producing an absolutely new engine, transmission, frame, and so on, necessary for the design the idealist might advocate. More than ten years have passed since the first of the modern, even-firing, vertical twins was placed on the market. With the exception mentioned earlier, in which the crankshaft is in line with the frame of the machine, all the designs that have emerged bear a flattering external resemblance to the originator of the fashion. But detail variations are worthy of close examination. Just as in the development of single-cylinder engines, so in the vertical-twins, more and more emphasis is put on rigidity of the flywheel assembly. Some designs incorporate a one-piece crankshaft and one has its shaft supported by three bearings. Another interesting aspect of crankshafts is that in two engines the material employed is cast-iron, whereas the others use steel forgings. The attractions of cast-iron are largely related to the fact that a fairly complicated design can be moulded, whereas with forgings the limitations are more severe. For example, with the forgings, a bolted-on flywheel is employed; castings can include an integral flywheel. Cooling between the cylinder bores of the vertical-twin type engine is given much thought by designers. Some employ a single-block casting embracing the two cylinders and others go the whole keg and have two separate castings with a clear gap between them. In the former layouts, however,

exceptional care is taken to ensure air inlets and outlets through the block and between the bores and also round any masses of metal such as push-rod tunnels. In one design the cooling between the bores is facilitated by having four separate cast-in push-rod tunnels at the ‘corners’ of the cylinder block. Though separate cylinders have attractions related to cooling, the top-half rigidity automatically obtained with a cylinder block is lost. Hence the separate cylinders are deeply sunk in the crankcase mouths and, in one design, the cylinder heads are tied by a plate above the exhaust ports to balance the constraining effect of the manifold at the inlet ports. A single camshaft operating both inlet and exhaust push-rods, as against two camshafts, one for inlets and one for exhausts, offers the advantage of a simplified timing gear and saves space. But it is usually easier to get cooling air round smaller push-rod tunnels than round one larger tunnel. Owing to the greater heat conductivity, lower running temperatures can obviously be obtained by the use of light-alloys in place of cast-iron. However, cast-iron is less costly, mainly because light-alloy cylinders need iron liners and light-alloy heads require hard metal valve-seat inserts. One design with light-alloy cylinder heads has cast-in iron hemispheres for the combustion chambers, a practice rarely encountered outside racing power units. Before the war, it seemed that there would be a fairly rapid changeover to chain-drives for timing mechanism and for driving auxiliaries such as magneto

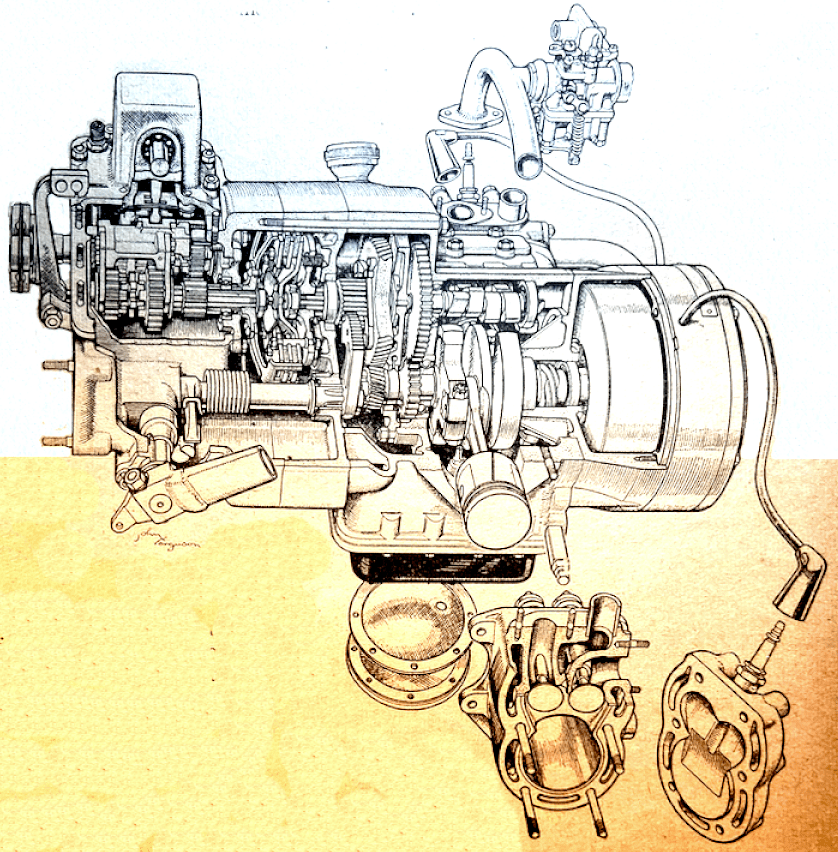

and dynamo. This, however, is still no more than a tendency, and both chain and spur-gear drives appear on the new designs of the vertical-twin. Chain-drive has the attraction of quietness achieved without the higher cost of the precision work necessary though it is none too easy to design a neat timing-gear layout for all-chain drive. The vertical-twin rightly claims much attention, but the new designs, of course, are by no means all of this type. The most enterprising design of the year is a horizontally opposed twin. Better balance is obtained with the cylinders opposed, yet the advantage of even firing is retained. Furthermore, the crankshaft disposition encourages integral unit construction of engine and gear box as well as shaft drive to the rear wheel. An unusual feature (on motor cycles) of the new horizontally opposed twin is the use of water-cooling. This has the merits of deadening mechanical noise and keeping temperatures down, thus lengthening decarbonisation periods and, in some respects, reducing wear; finally, water-cooling demands no intricately finned castings to ensure that the cooling medium gets to the right places. Many technicians maintain that water-cooling for motor cycle engines is overdue and would come if buyers were known to be ready to accept it. Yet another newcomer, at least to public gaze, is an opposed four-cylinder with a rocking beam interposed between the connecting rod big-ends and the crankshaft. The attractions are near-perfect balance and economy in overall width of the engine—the latter a powerful consideration with an engine of largish capacity and overhead-valve gear. Most British two-stroke engines are, of course, made by one proprietary manufacturer. The entire range of engines has been redesigned and

they now give more power. There is a comparatively new engine of this type from a very famous factory which, although already sent overseas in large numbers, is for the first time available to the British public. It was thought that some attention would be given by two-stroke engine manufacturers to carburettor enclosure, with the purpose of concealing the oiliness inseparable from petroil lubrication and of protecting the rider, but this step has not yet been taken. There are no indications of renewed interest in side-valve engines. Comparatively few engines of this type are made and no real clamour for more is discernible. A widespread view among manufacturers is that modern ohvs are so reliable and quiet mechanically that there is little to recommend the side-valve which, while produced in comparatively small numbers, cannot be much cheaper to buy than an ohv of equivalent capacity, and will usually be heavier on fuel. The query arises whether our designers could not with advantage give more attention to the development of side-valve engines. It is not without significance that the designers of the new horizontally opposed water-cooled twin decided to employ side-by-side valves. Though two designers responsible for engines with the crankshaft in line with the frame have taken advantage of the fact and provided the natural corollary, full unit construction and shaft final drive, all-chain drive remains far and away the most popular. This form of drive is likely to continue while engines with the crankshaft across the frame predominate. There is, however, a steady trend towards providing fixed centres between engine and gear box. If the crankcase and gear case are not an integral casting then, in a number of instances, separate castings are bolted together. Primary chains may then be of the non-adjustable type, or have a manually or automatically adjusted slipper. Duplex chains are employed on a few engines and a triple row chain on the only I,000cc twin at present marketed. Integral and bolted-up unit construction might seem an obvious and worthwhile development. But sometimes noise accentuation and too much heat transference to the clutch provide the designer with problems which, while not insuperable, can take time to overcome. Gear boxes and clutches have reached a stage of such high reliability that they are often taken for granted. Four gear ratios are provided on all except small-capacity machines, and gear-changing by a foot-operated positive-stop mechanism is almost universal. Development is likely to be directed to