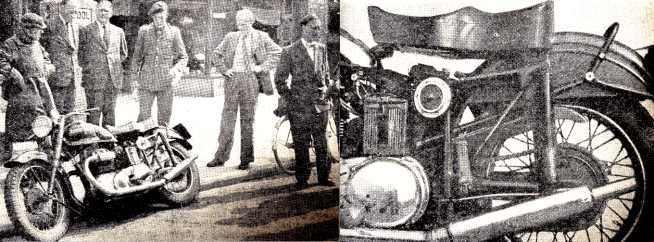

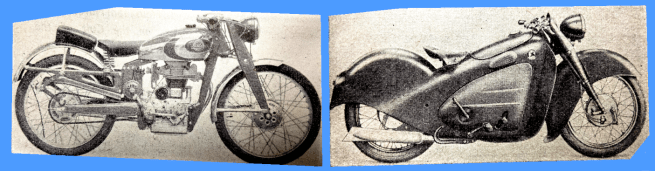

THE MOTO MAJOR 350 WAS A futuristic monocoque streamliner designed by Turin engineer Salvatore Maiorca and funded by aerodynamic research specialist Fiat Aeritalia. It was part of Fiat’s exploration of the motor cycle market (just before the war Fiat had produced a prototype scooter). The radical streamliner was designed for a 350cc water-cooled vertical twin featuring two radiators in the fairing. The prototype had to make do with a 350 single but an extra dummy exhaust was fitted. To save space the suspension was built into the wheels, harking back to the ‘elastic wheels’ that appeared briefly at the turn of the 20th century. Fiat planned to collaborate with Pirelli in a purpose-built factory; the Major created a stir at the Milan Show but the project fizzled out though the prototype survives at the Hockenheim Museum. (There’s a report on the Milan Show further down the page.)

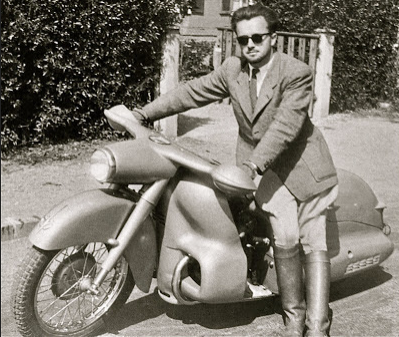

ANOTHER MIGHT-HAVE-BEEN STREAMLINER: this time based on a 1935 BMW R12 750cc sidevalve flat-twin. It was designed by French-born but German-based industrial designer Louis Lucien Lepoix who bought the Beemer at an auction held by the French Military in Baden-Baden. This one remained only a concept vehicle, but Lepoix went on to work for majopr manufacturers including Kreidler, Hercules, Horex, Puch, Maico and Triumph.

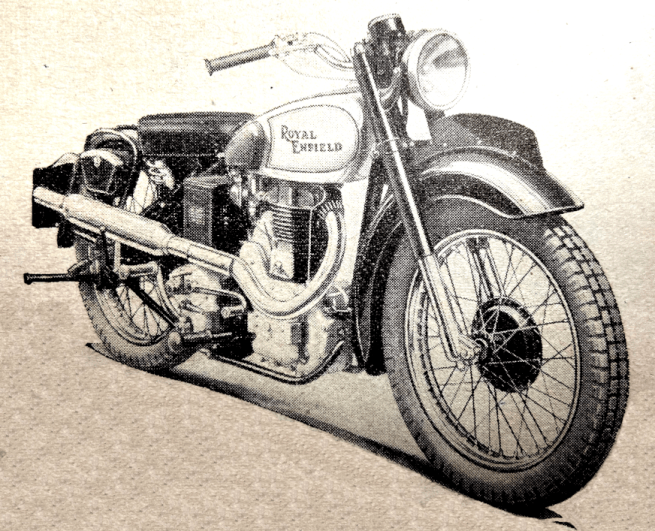

“READERS OFTEN DECLAIM about the shortage of new machines. What are the facts? In spite of the British motor cycle industry in 1946 almost trebling its 1938 exports—the percentage was no less than 270 and the White Paper figure for 1947 is 140—more new (and ex-WD) motor cycles were registered in Great Britain during 1946 than in any year since 1930. The figure was 75,274, which has only been exceeded five times since the 1914-18 war. An interesting point is that immediately following that war, although there were almost literally hundreds of motor cycle manufacturers and assemblers, the 1946 figure was exceeded but once and that was in 1920, when the total was 84,00. When the many difficulties of 1946 are recalled, the industry’s achievement is very remarkable indeed. Analysis of the figures reveals that of the 1946 total almost exactly 14,000 were machines of under 150cc—mainly motor cycles of 125cc, the so-called ‘Flying Fleas’ which earned fame during the war. These greatly outnumbered the motor cycles in the 250cc class. The latter totalled 8,248. Of course, the bulk of the registrations were of 350cc and over—a total of no fewer than 47,645. Sidecar outfits numbered a bare 4,000. The smallness of the number was, of course, due to the difficulty of obtaining sidecars. The ratio of 1 in 20 between sidecars and total new registrations is very different from the pre-war 1 in 5, which was the position the sidecar occupied in relation to all the motor cycles on the road. To-day’s prices of cars place a great, premium on the sidecar machine, a fact that the industry might well bear in mind.”

“A CHESHIRE READER, unable to obtain factory-made legshields for this past winter, designed and made his own. His principle may appeal to readers who plan to do ditto next autumn. He bolts footboards over the standard footrests. His shields, of approximately U-section, are made of patent leather, stiffened with steel wire, and fixed to the footboards. They are steadied at base and summit by very light stay rods attached to the frame. Legshields, he maintains, are illogical with footrests, since if there is enough liquid filth about to make shields desirable, the entire foot needs protection. The weight is low; and when summer tardily appears five minutes with a spanner detaches the entire caboodle.”—Ixion

“SOME SURPRISE IS being expressed at the ACU decision to run the Senior and Lightweight Races concurrently. It is urged in some club circles that the Manx course bristles with tricky corners on which a precise line must be taken to maintain a winning average of 90mph, and in any case the presence of many slow machines will be a nuisance and a handicap to the 500cc aces. (The approximate averages of the three Races are Lightweight, 75; Junior, 85; Senior, 90. Since by previous decision three races have to be crammed into two days, the interests of the greatest number must be considered, and opinion is that Junior entries will be numerous, with Senior and Lightweight entries comparatively small. Will the presence of 75mph Lightweights among the 90mph Senior leaders really bother the big ‘uns more than a crowd of second-rate entrants on 500cc machines have done in previous races confined to 500cc and securing a huge entry?”—Ixion

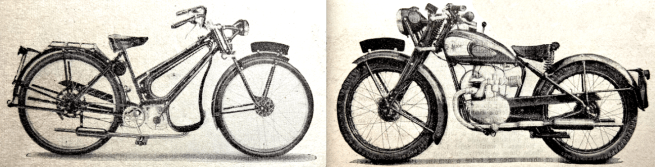

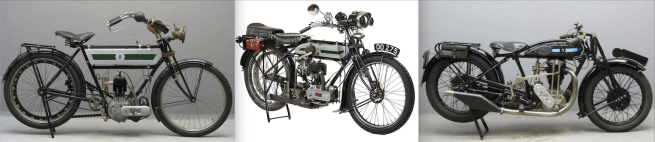

“A VETERAN READER asks me to compare the typical modern 98cc autocycle with the small single-cylinder Minerva and Kelecom motor cycles of 1902 or thereabouts. If he refers to reliability, the modern wins by streets. In speed and climb there is probably no substantial difference. The pioneer engines wore much faster. The lack of clutches and the crudity of the carburation were serious defects. Modem transmissions stand in a far higher class. Financial contrasts are difficult, seeing that at the moment we suffer from inflation. In 1939 a good autocycle cost round about £20, whereas I seem to remember paying £45 for a 1¾hp Ormonde and for a 2hp Minerva.”—Ixion

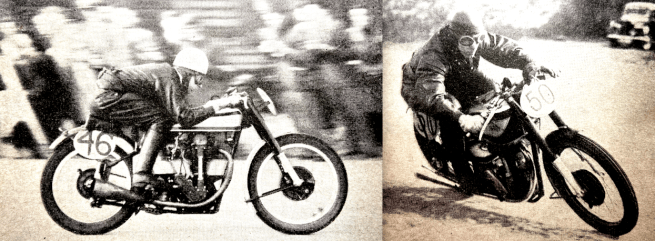

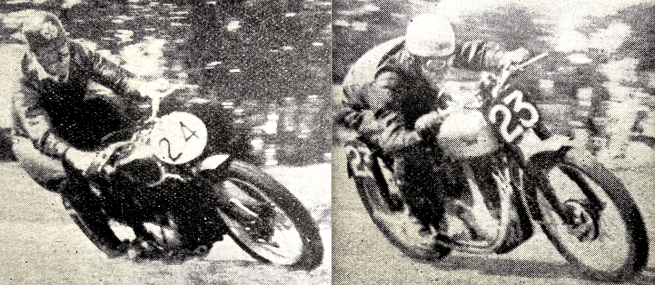

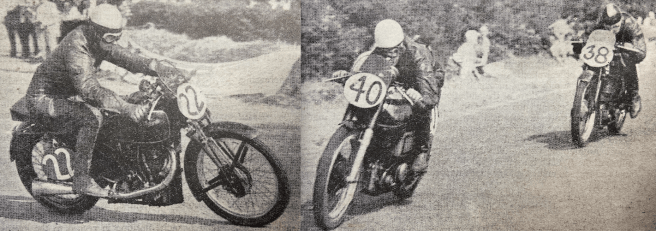

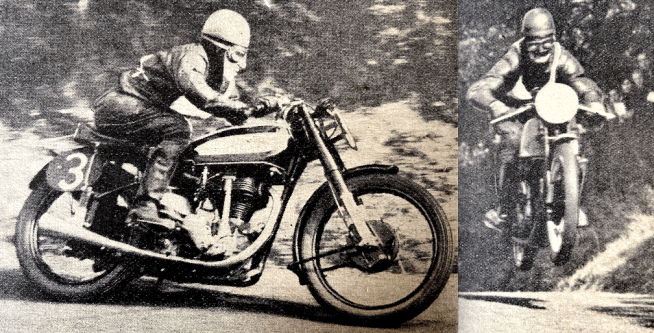

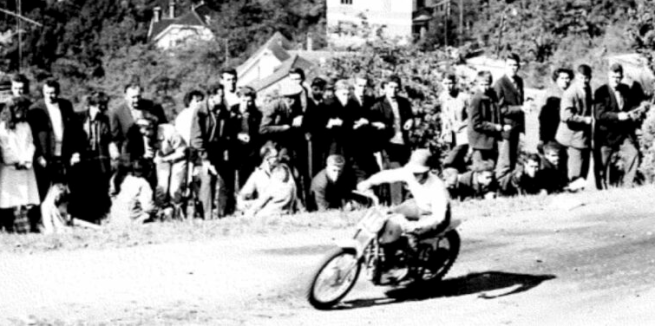

“RACING AT STAPLEFORD Tawney Airfield, near Abridge, last Saturday, was scheduled to start at three o’clock. Yet at 3.25 vast crowds were still flocking into the airfield. The weather was truly spring-like and the atmosphere distinctly Cadwell-like as the North-East London Club worked to get the spectators into the inside of the racing perimeter, where the only possible parking space was available—nearby fields had become flooded. In the pits, eager, perspiring competitors were working furiously, and some very interesting motors were to be seen. Many were disappointed to learn that RL Graham’s push-rod AJS was to be a non-starter. He had broken a valve spring in practising, and as it was of the enclosed hairpin type, a replacement could not be obtained in time. As usual, a trio of Rapides was a focus of interest. The course, shaped roughly like an egg with one flat side, proved to be almost a natural road-racing circuit. The surface on the far side from the timekeeper’s table was rather bumpy, and the wide curve culminated in a goose neck, before swooping downhill to the right-hand turn and into the finishing straight. The first race—a four-lap novice event for solos of unlimited capacity—started at 3.30. Competitors’ machines were lined up diagonally along one side of the track, and at the drop of the flag the riders ran to their machines and were off. A laugh was raised when D Gregory was found holding his Norton, and his mechanic was lined up with the riders! Girder-forked machines seemed to pre-dominate in this event, and with a roar and a bellow LR Archer (250cc Velocette) was first off the mark. He was hotly pursued, and when riders came round on Lap 2, D Gregory (490cc Norton) was the first to be seen. He was followed by L Peverett (498cc

Triumph). Fighting hard for third place were J Medlock (500cc Ariel), G Monty (499cc Norton) and RH Buxton (490cc Norton). Speeds seemed to be very high. On the next lap Gregory was leading by a considerable distance, and with a roar Peverett and Monty flashed past together. DH Glover (249cc Rudge) seemed to be a shade overgeared. Gregory was the first man home at 56.8mph with Monty second (56.5mph and Peverett third (56.3mph). The second event was of six laps for solos under 250cc. Rudges were very much in evidence at the start, but JH Colver (247cc Matchless) was first away. At the end of the first lap RH Pike (249cc Rudge) was using every inch of the road as he swept into the straight in the lead. Riding with great skill, he maintained his lead throughout and won easily, at 57.87mph. A Hiscock (248cc Velocette) was runner up at 57.2mph—LR Archer (250cc Velocette) was third at 56.4mph. The third race was run in two heats, and was a six-lap event for under-350s, the eight fastest in each heat qualifying for the final. In the first lap S West led all the way. With his DKW howling its ear-splitting war-cry he was riding in masterly fashion, but he was hard pressed by CE Beischer (350cc Norton)—the ultimate winner. West came off on the gooseneck, and Beischer’s win—at nearly 2mph faster than the second man—proved his riding ability to the full. Third place went to CW Petch (348cc Norton). The second heat was closely contested. TL Wood, on his old 348cc Velocette, made—in comparison with his usual rapid get-away—a leisurely start. When he came round later, however, he was obviously in a hurry, and led WT O’Rourke (348cc Velocette) and D Parkinson (348cc Norton), who were very close. The telescopics of the leading machine on Lap 2 were obviously not Wood’s; no, Parkinson was leading. The winning pair were scrapping hard, but the Norton was a shade too fast for Wood’s Velocette; Parkinson won at 59.82mph.The final was delayed to allow TL Wood to change a tyre. Then, at the starting signal, his 348cc Velocette streaked away and was first into the bend before the gooseneck. He was leading the field until

the fourth lap, when he hit a nasty hole while heeled over on the bend leading to the straight. He was only shaken, but his untimely exit allowed Parkinson an easy win at 60.64mph ahead of EE Briggs (348cc Norton) at 59.73mph and O’Rourke (59.5mph). Wood made the fastest lap at 65.45mph. The fourth race was for solos up to 1,000cc, and a stir of interest was caused when George Brown wheeled his Rapide to the start. He was first away, but close on his tail was D Gregory (490cc Norton), who was leading on the second and third laps. Throughout the race there was nothing between the leading trio—D Gregory (490cc Norton), G Brown (1,000cc Vincent-HRD) and EE Briggs (490cc Norton). But it was the Rapide that was first to get the flag (61.52mph) with Gregory second (61.51mph) and Briggs (61.1mph). The second heat was as exciting as the first, with J Lockett (490cc Norton) dominating the whole race and Crow scrapping with Heath for second place. Lockett won at 63.93mph, followed by Crow 60.72mph and Heath (58.05mph). A sidecar event, not on the programme, was run before the final of the 1,000cc class. There were four starters; the most notable were Surtees, with a Rapide and Oliver (596cc Norton). Surtees retired to the pits after only one lap, and Oliver, ahead of the others the whole way, won at 56.4mph—almost as fast as some of the solos. The final of the 1,000cc class was fast and furious. Brown got away clean and fast, but was closely pursued. The Rapide locked solid on the gooseneck (Brown was uninjured). Lockett made a lap record at 67.14mph and increased his lead rapidly to win an exciting race at 65.22mph with D Gregory second at 63.1mph and Crow third at 62.62mph.”

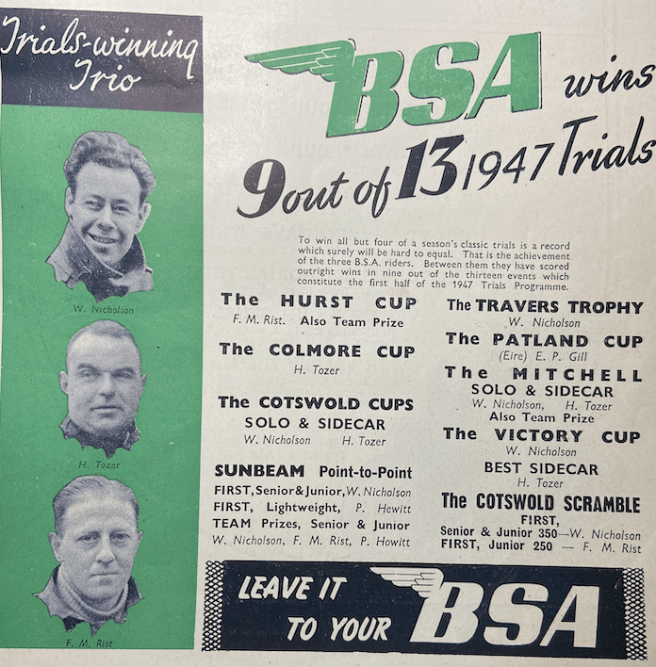

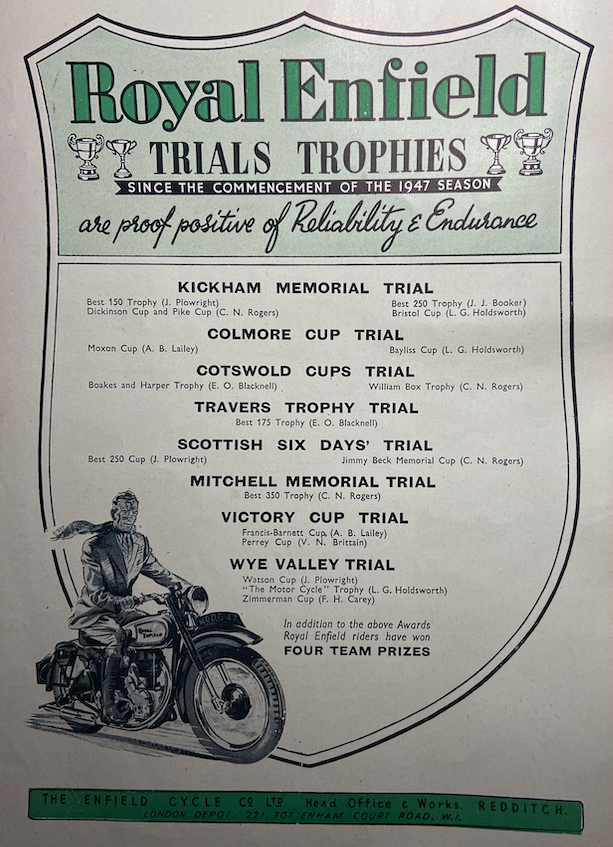

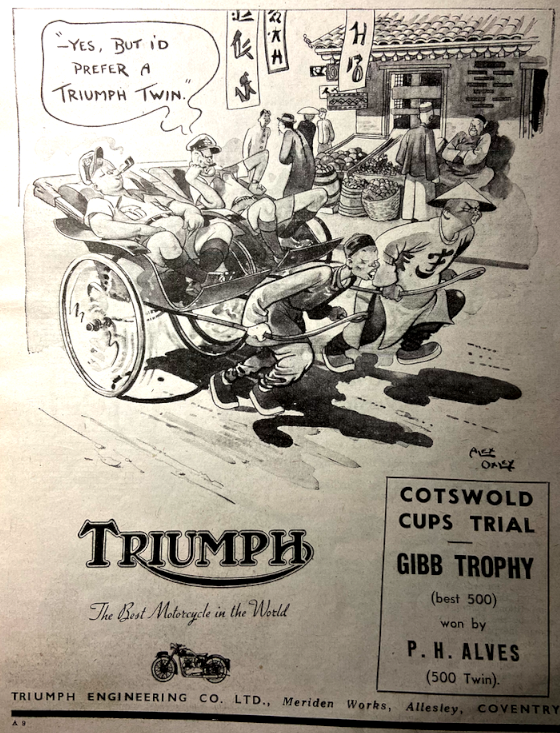

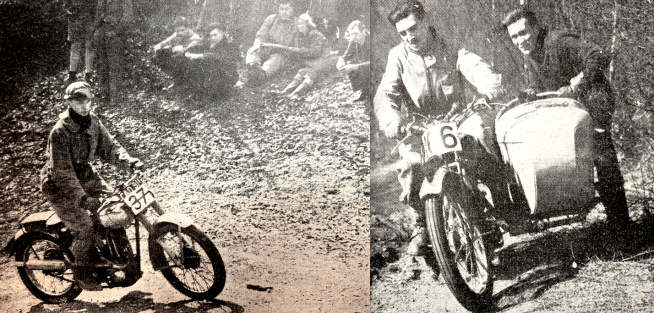

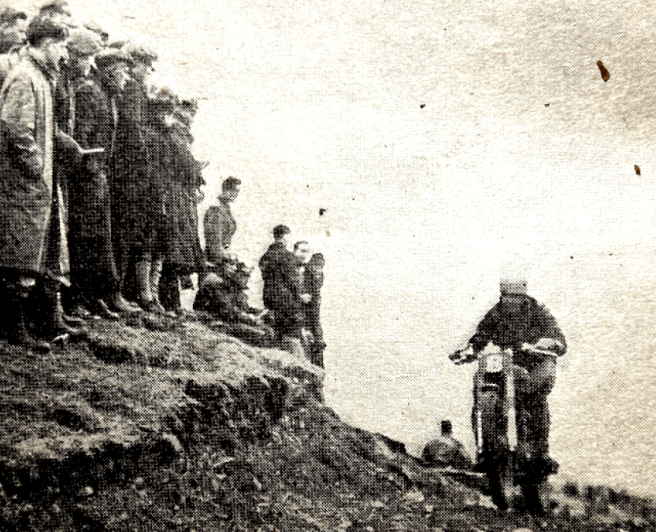

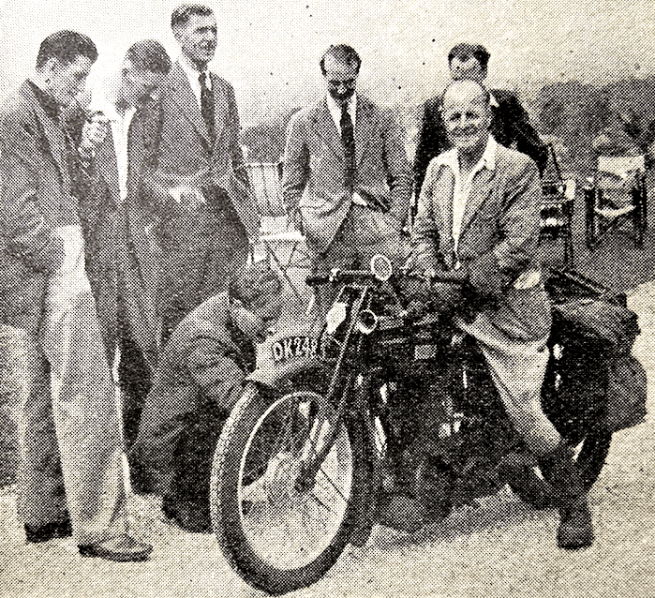

“NO EVENT COULD HAVE been a more fitting fiftieth for the Clerk of the Course, Mr HP Baughan, than the Cotswold Cups Trial. First, the winners were decided entirely by performance without resort to the special tests; second, the course was rideable clean throughout, except for sidecars in one sub-section; third, there were no delays and, finally, even the weather co-operated to provide the first ‘all-sunshine’ open trial of the year. So delightful was the weather that, however inconvenient at the time, no one could possibly have regretted the postponement—enforced by the snows—from March 8th; indeed, the thought was inescapable that perhaps the April-May period would be a more suitable time of the year for the important ‘opens’ than the habitual earlier months. In winning the solo cup, W Nicholson (348cc BSA) rode confidently and skilfully to remain unpenalised throughout the course; he was the only competitor to do so. The sidecar winner, H Tozer (496cc BSA), continuing to ride in the first-class style he has shown post-war, was a clear six marks—one stop or three foots under the marking for this trial—ahead of the next competitor in this class. Sunbeam MCC, represented by J Blackwell (49cc Norton), BHM Viney (347cc AJS) and CM Ray (497cc Ariel), won the team award, thus proving superior not only to other club entries, but also to manufacturers’ teams. The bright weather of the few days preceding Saturday had taken the sting out of some of the sections. Ham Mill, though rarely severe was a meek and mild first observed section on the route card, but it served the very good purpose of a setting for the special tests to decide ties. Similarly, Leigh, which followed, was innocuous except for a mud hole in the second sub-section. Here the mud was of watery consistency and the run-out of surprising slipperiness. It was a matter of fine judgment to gauge the highest safe speed through the liquid mud in order to pass over the three yards of ‘slither’ without undue wheelspin. M Laidlaw (347cc Matchless) was not quite fast enough and, while fighting wheelspin valiantly, had to dab just once. Afterwards he ran back to warn his team-mate, AW Burnard on a similar Matchless, who zipped through without trouble. Surprisingly, Colin Edge, on another Matchless, was caught out; he had a front wheel slide so severe that to avoid climb-ing the bank he had to foot in most determined fashion. JE Breffitt (490cc Norton), though he seemed fast enough, was almost stopped by wheelspin, and Jackie White (248cc Ariel) who tried slow, body-leaning tactics, fell in the deepest of the mud. Loud applause from spectators followed B Holland (349cc Triumph Twin), who gave a consummate exhibition of throttle control, and E Wiggall motored his 348cc BSA through with equal skill. Frank Fletcher’s spring-frame 125cc Excelsior buzzed gaily, but he had to bounce in the saddle, and later to foot, to keep going. The long climb which constitutes Camp 1 and 2 was difficult only in the deep ruts of the three-ply towards the end of the former. Rider after rider had to dab occasionally for balance as front wheels refused to remain down on the hard base of the middle rut—that selected by almost everyone. In roughly the first 50 competitors to arrive only Burnard, TV Ellis (498cc Matchless), CN Rogers (250cc Royal Enfield) and NE Vanhouse (347cc Ariel) were feet-up throughout Camp 1. Later numbers had to contend with a rut that got deeper and deeper as the base was worn down by biting tyres—RW Sutton had to foot forcefully as be footrests of his 497cc Ariel grounded.”

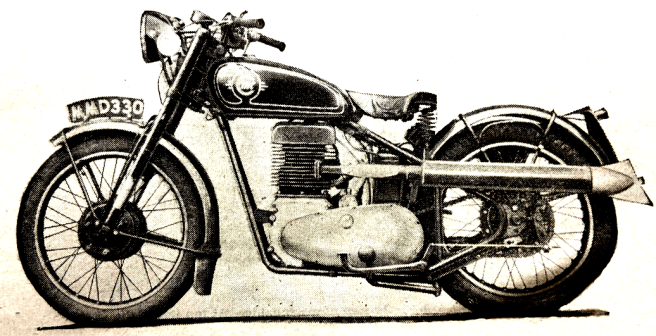

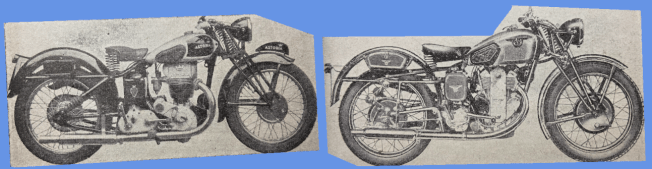

“TRIALS ENTHUSIASTS will be pleased to learn that there is a new 499cc competition model BSA, to be known as the B34. Deliveries of the machine are not expected to begin until about June of this year. Very similar in looks to the 350cc trials mount (B32), the new 500ohv single has a larger carburettor; this is the only obvious-to-the-eye point of external difference between the two trials machines. Bore and stroke of the B34 are 85 and 88mm respectively, and the compression ratio is 6.8 to 1—in fact, the engine is the same as that of the recently announced standard 500 B33. Gear ratios of the new competition model are naturally lower than on the standard 500, being 5.6, 7.3, 11.1 and 15.9 to 1. These are identical with the ratios on the standard 350 B31. Tyres are 4.00×19 rear and 2.75×21 front. An upswept exhaust pipe is fitted. A brief flip up the road, on a prototype, revealed that the B34 is a lively, extremely pleasant machine to ride, handles well, and has an excellent riding position. The brakes on the model ridden were particularly impressive, being spongy, yet powerful and progressively smooth in action. Price of the machine, fully equipped except for a speedometer, is £134, plus P[urchase] T[ax] £36 3s 7d, totalling £170 3s 7d. Makers are BSA Cycles, Birmingham, 11.”

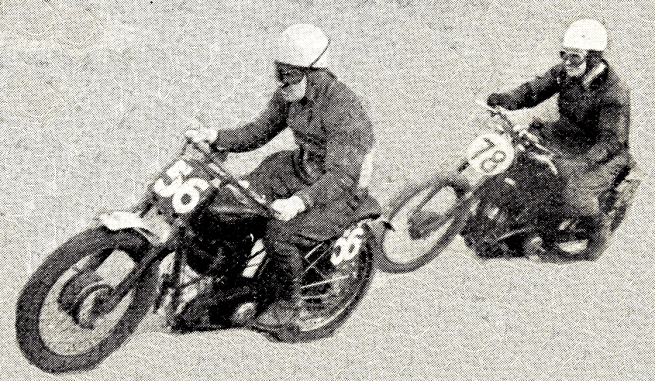

“THERE WERE 30 entries for the Stamford Bridge April Scramble on Bagshot Heath last Sunday, a programme of four races being run off with commendable efficiency. The course, just over a mile in length, was almost all visible from the starting point, and an unusually large crowd enjoyed an afternoon’s sport in perfect weather. High-spots included George Eighteen’s doggedly holding the lead from Bessant throughout the first half of the Unlimited race, and a neck-and-neck finish by Hall and Cullford in the Non-winners event.”

“NEWS FROM BELGIUM is that in national scrambles not more than five foreign riders may compete, and in national road races there may not be more than six foreign entries with a maximum of two from any one country. On the face of it this new ruling is reasonable enough, but it does preclude a party visit on the lines of the Sunbeam Club’s trip to the Grand Prix du Zoute last July. That is a pity, I think. Much of the fun and much of the encouragement to ride in Continental events is wrapped up in an organised visit with fellow enthusiasts. It is no answer that there is no restriction on the number of foreign entries in International events. Many of the riders who would join a party to support a Belgian race are still anxious to retain their eligibility for the Manx Grand Prix. Last year our friends in Belgium were most anxious to get British entries and I know the new rule will strike a dull note in many quarters.”

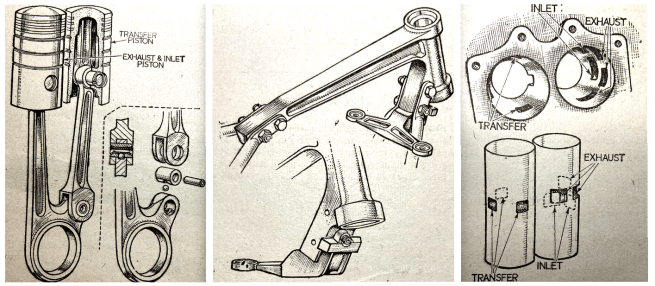

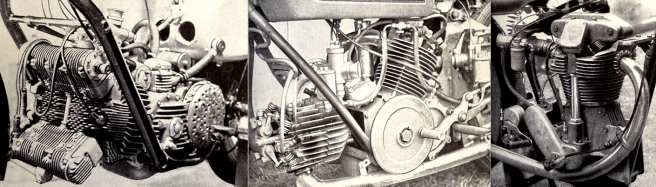

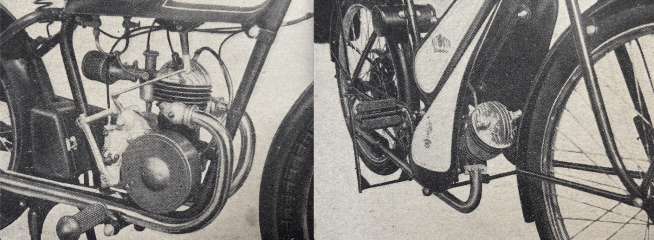

“TWO-STROKE ENGINES of the ‘double-single’ type have been used successfully by Puch and TWN (German Triumph) for a number of years. There is now being produced in England a machine, the EMC, with a 350cc engine employing the familiar layout of two cylinders with a common combustion chamber and a forked connecting rod. Two of these machines, one with a side-car, competed in the Land’s End Trial at Easter. Running in single ball races, the steel flywheel assembly has a 1³⁄₁₆in diameter crankpin that is a press-fit in the fly-wheels. Caged rollers ½x¼in are used in the big-end of the steel connecting rod, which is forked just above the big-end eye and fitted at this point in the front branch of the fork with a wristpin. It will be remembered that the German engines use a rectangular gudgeon pin and a sliding small-end eye to accommodate the variation in gudgeon-pin centres which occurs during each revolution of the fly-wheels. Exceptionally long—in comparison with a bore of 50mm—Specialloid aluminium-alloy pistons are used; in point of fact, the rear (exhaust, and inlet) piston is 111mm. and the front (transfer) piston is 99mm. Each piston is fitted with three pegged compression rings and has, between the lower ring and the gudgeon-pin boss, situated well below the midway point, three circumferential oil grooves.

The bottom groove feeds oil to the gudgeon pin through the piston bosses. The gudgeon pins are 16mm in diameter, are located in the pistons by circlips, and operate direct in the small-end bosses of the connecting rod. The cast-iron cylinder block is retained…The duplex cradle frame has a manganese-bronze backbone embracing the steering head and the steering stops; bolted to the backbone is a casting in similar material which forms the front tank supports. The twin front down tubes of the frame and the two seat stays are joined to the backbone by being strengthened with inserted smaller-diameter tubes, flattened at the ends and bolted in position. The frame has no seat pillar, but has vertical supports between the rear fork tubes. Heavyweight Dowty air-suspension forks are fitted. The front wheel has twin 7x⅞in brakes, compensated by an arm anchored on a stay. This stay is, of course, bolted to the unsprung tubes of the forks and curves above the mud-guard. A single brake of similar size is fitted to the rear wheel. The tyres are Dunlop 3.00x20in on the front, with a ribbed tread, and 3.25x19in studded tread on the rear. Journal ball bearings, 47×20 mm, are used in the aluminium-alloy wheel hubs. The welded steel petrol tank is fitted with a reserve tap and has a capacity of three gallons. The oil tank holds three pints. Footrests and handlebars are adjustable. Other features are a centre stand, a Lycett saddle and a 6in Lucas headlamp incorporating the switch and ammeter. Speedometer drive is from the rear wheel. A short road test of the EMC showed that its steering and road-holding qualities are of a very high order, and the Dowty forks eliminate road shocks with a noticeable absence of pitching. The twin front brakes are extremely powerful, with light action. The engine starts easily, has a ‘well-oiled’ quietness at all times, and pulls so well that a three-speed gear box would be perfectly adequate. Under all conditions except very low speed idling, the engine two-strokes and is free from vibration. The general finish is black enamel with silver tank lining; wheel rims, exhaust system and other bright parts are chromium-plated. It is stated by the makers, the Ehrlich Motor Co, Twyford Abbey Road, NW10, that the power output is 18bhp at 4,000rpm, that the top speed is 70-74mph, and that petrol consumption is better than 100mpg. The price, including speedometer, is £150 10s, plus £40 10s Purchase Tax. The machine described is the Mark I touring model. Later a Mark II sports model and a Mark III super sports model will be introduced; both will have water-cooled engines.”

“SEVEN CLUBS—CHELTENHAM, Antelope, Stroud, Cotswold, King’s Norton, Castle Bromwich and Union Auto—have indicated that they are definitely playing motor cycle football this season. Friendly matches between these teams are now being arranged. Since the Antelope meeting last month, Vernon Muslin, the secretary of the general committee, has got cracking and Bulletin No 1 has just been issued. The Referees Panel has been formed, the suggested amendments to the rules of the game have been ratified by the ACU Competitions Committee. A happy gesture has been made by the Cheltenham Club. To foster enthusiasm among inexperienced teams Cheltenham is willing to provide a challenge cup for ‘B’ teams and others just starting the game to be won in a knock-out competition. Another trophy is the Antelope vice-president’s cup to be awarded to the runners-up in the final of the ACU Challenge Cup competition which will be decided later in the season. I should like to see more clubs get interested in motor cycle football, because it offers good, clean sport and is easily staged.”

“POLICE MOTOR CYCLISTS are not eligible for the Services trial on April 27th. However, in co-operation with the CSMA responsible for organisation, members of the Surrey Joint Police are to follow the Services entry and have their own training trial; they will be riding in uniform and on Police models. Such keenness deserves consideration—would it not be possible for the Police to be recognised as a ‘Service’ by the time next year’s event comes round?”

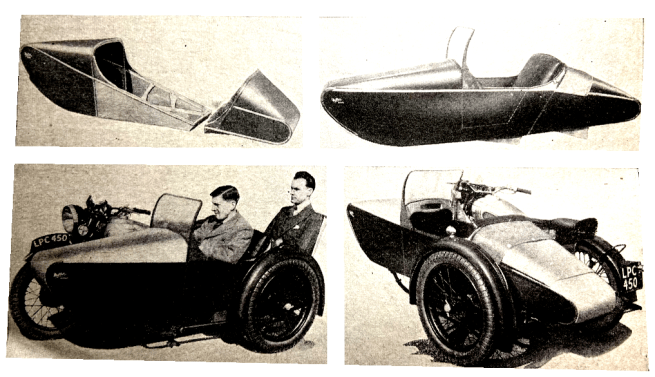

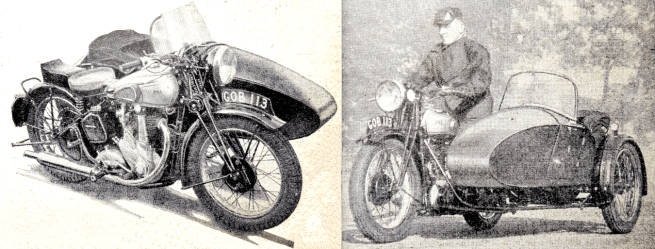

“IT WILL BE RECALLED that in the autumn of last year Millar’s Motors introduced a sidecar body with frame-work and panels in aluminium alloy. The range has now been extended to five bodies; there are the Competition, the single-seater Sports, the single-seater Tourer, the Occasional Two-seater, and the Adult Two-seater. All these bodies are constructed on the now well-tried principle of using 1x¾x³⁄₁₆in extruded angle-section aluminium alloy for the framework with castings in similar material for all main supports, door frames, dash frames, lid frames and windscreen frames. Panels are in 20-gauge sheet aluminium attached by Chobert self-expanding rivets, and fluted sheeting is used for the floors. Seat squabs are spring upholstered and Rexine covered; body lining is board-backed Rexine. The makers are Millar’s Motors, 365, London Road, Mitcham, Surrey…Standard finish is polished aluminium; anodised colours, black, red, blue and black and silver at an extra charge.”

NORTON’S POST-WAR RACERS appeared under the Manx banner: the Manx 30 (500) and Manx 40 (350). They featured light-alloy top-ends and plunger (‘garden gate’) rear suspension with ‘Roadholder’ teles up front. (No need for a pic here; you’ll find Manx Nortons in the TT report which follows.)

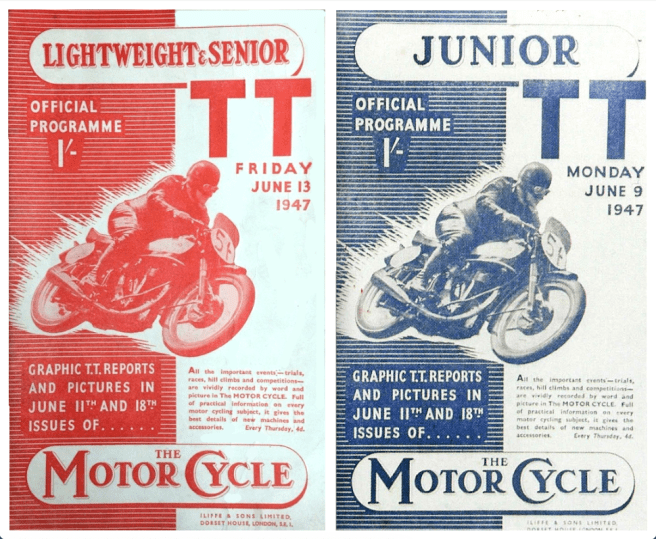

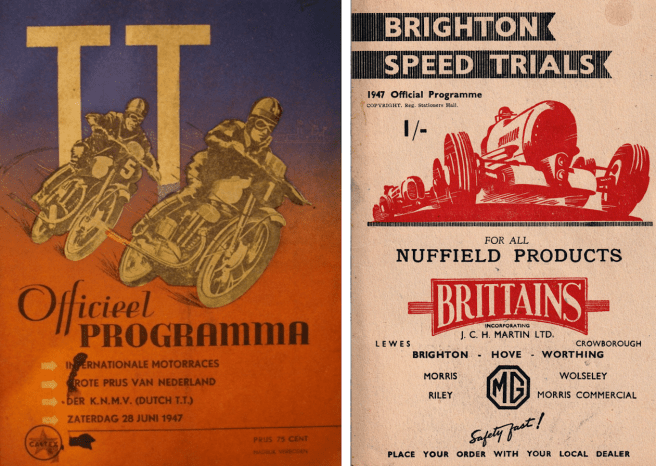

Having been so rudely interrupted the TT bounced back and, as so often before, we can do no better than turn to Geoff Davison, editor of the TT Special, for an insider’s report. Mr Davison, you have the floor.

“PEACE BROKE OUT in 1945. But, as in the case of the previous peace, it was not found possible to run the TT in the year which immediately followed it. Manufacturers had discarded their racing designs and had been concentrating on the production of sturdy, go-anywhere motor cycles for Services use. By 1947 we were ready and the A-CU, fresh after eight years’ leave of absence, returned to the game with an energetic programme. During the 14 pre-war years—1926 to 1939—there had been three annual TT races; for 1947—perhaps to make up for lost time?—there were to be six. The three old-stagers, Senior, Junior and Lightweight, were continued as in the past, but three ‘new boys’ had joined the TT school—Clubman Senior, Junior and Lightweight [the Clubmen bikes were essentially roadsters stripped of their lights and silencers—Ed]. Clubman Senior was a really ‘big boy’—the biggest in capacity that the TT course had ever seen. Brothers Junior and Lightweight were limited to 350 and 250cc capacity, as in the International races, but in the Senior machines of up to 1,000cc could compete. Actually only two of the real ‘big ‘uns’ entered and, as it happened, neither started, the largest machine in the race being a 600cc Scott. But back to the beginning…When the A-CU. announced the 1947 Clubman’s races, there were many misgivings and shakings of heads. Very wisely, separate practice periods were allowed for clubmen, so that their slower machines and presumably less skilled riders should not get in the way of the real racers. Unfortunately there is a limit to the number of days on which the Manx roads can be closed and the clubmen had therefore to be content with four periods only. These, however, passed off without serious mishap and the pessimists, finding that their worst hopes had not materialised, became gloomier than ever. Before starting to describe the Clubman’s races, I must make some mention of the rules which governed them. Generally speaking, the regulations were similar to those of the International TT races, but there were a number of important exceptions. Chief of these was that which applied to the specification of the machine. The paragraph in the supplementary regulations which defined eligibility of machines—ironically enough, it was No 13—read as follows: ‘Definition and Specifications. Every motor cycle entered for these Races shall be a two-wheeled vehicle propelled by an engine and shall be a fully equipped model according to manufacturer’s catalogue which shall have been published before the 28th February, 1947, such catalogue to be submitted to The Union by the entrant not later than 3rd May, 1947. At least 25 of each model entered shall have been produced by the makers and such motor cycles shall include in their equipment, kick starters and full lighting equipment.’ The essence of this rule was that Manx model Nortons and KTT Velocettes were barred. Although machines had to be catalogued with electrical equipment, head and tail lamps, horns, wiring harness, wheel stands and registration number-plates, it was compulsory for these to be removed both for the practising and the races. It was also permissible (but not compulsory) for accumulators, luggage carriers, speedometers and dynamos to be removed and riders were allowed to alter the positions of footrests and brake operating mechanism to suit their requirements. The lightening of the machine by filing, drilling or by the substitution of lighter metal was barred and exhaust-pipes had to be ‘approximately the same diameter throughout’, ie, megaphones were barred. As in the TT proper, Pool petrol only was available. One of the biggest differences between the

Clubman’s and the International events was in the matter of kick-starters. All Clubman’s machines had to be started at the beginning of the race by the kick-starter—not by pushing. There was a compulsory pit-stop at the end of the second lap, after which the engines again had to be re-started by kick-starter. Run-and-jump starts were only permitted after a voluntary or involuntary stop during the race itself. The Clubman’s TT was in no sense an amateur event, for cash prizes were offered and any rider was eligible provided that he was not competing in the 1947 TT itself. Incidentally, the cash prizes in each event were as follows: First, £50; Second, £40; Third, £30; Fourth, £20. In addition, all entrants, including the above, whose drivers finished within six-fifths of the winner’s time, received a free entry in the 1947 Manx Grand Prix. Note that it was the entrant who received this free entry, not the rider. Actually no rider could enter himself, for entries were restricted to clubs of the Auto-Cycle Union or Scottish Auto-Cycle Union. Stanley Woods would have been eligible to ride as a member of the club entering him, but, had he finished within six-fifths of the winner’s time (as would have been highly probable!), he would not have been eligible to ride in the Manx Grand Prix owing to the rules and regulations of that event. The free entry would therefore, presumably, have been given to another member of the club. The three Clubman’s races were scheduled to be run off concurrently, this being the first time in TT history that more than two races have been run together. Senior and Junior riders had to cover four laps of the course (150.92 miles) and Lightweight riders three only (113.19 miles). The A-CU reserved the right to restrict the total number participating in the Clubman’s races to the maximum of 80, but actually this number was not reached. There were, however, 64 entries—a very satisfactory number for a ‘new boys” event—33 in the Senior, 23 in the Junior and eight in the Lightweight. Competitors were started at 15-second intervals, with the Lightweights first, the Juniors second and the Seniors last. Doubtless this was arranged in order that the races might present more of a spectacle, ie, so that the winners might come in more or less together, but my own view is that it was the wrong way round, for the juniors had to overtake all the Lightweights, and many of the Seniors had to overtake the whole field of Lightweights and Juniors. It would be safer, I think—if less spectacular—to start the fastest machines first, so that they had more or less clear roads, as was done in the Manx Grand Prix of the following September. However, the Lightweights started first and, as they only had three laps to cover, they finished first. I will therefore describe the little race—little in entries as well as in capacity—before turning to the two more keenly contested events.”

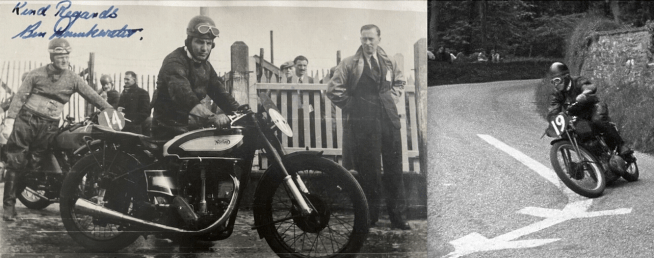

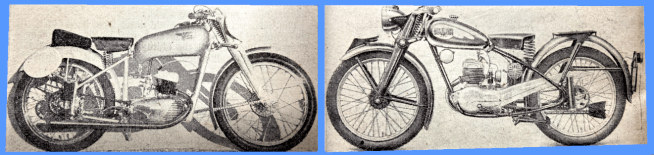

Clubman Lightweight

“THE EIGHT ENTRIES in the Lightweight race were composed of an AJS, a Triumph, three Excelsiors and three Velocettes. All eight riders presented themselves at the final examination, but one of them, RJ Edwards (Excelsior), was not allowed to start as he had not covered a sufficient number of practice laps. The 1947 Clubman’s Lightweight, therefore, ties with the 1925 Ultra-lightweight, which also had seven starters, for the doubtful honour of being the smallest TT race in history. LR Archer (Velocette), W McVeigh (Triumph) and BE Keys (AJS) had made the best times in practice, all having lapped in under 37 minutes, and it was they who occupied the first three places at the end of Lap 1. McVeigh was in the lead, with a lap of 34min 31sec (65.61mph)…the first four riders were all on different makes of machine. McVeigh increased his lead in the second lap, as did Keys, but Wheeler retired, letting DG Crossley (Velocette) into fourth place. Whilst the Juniors and Seniors were still chasing round on their fourth laps, McVeigh completed his third and last in 1hr 44min 2sec. He was therefore acclaimed the winner, with Keys second and Archer third. Four hours later came sensation, for the following announcement was made: ‘The Stewards have decided with great regret to disqualify No 2, W McVeigh, entered by the Pathfinders Club for having an engine with a capacity greater than permitted for the Lightweight race…’ Keys was named the winner, with Archer second and Crossley third, and at the prize distribution that night the appropriate cheques were duly handed out. McVeigh, however, was not satisfied. Apparently his engine had been rebored and was therefore a shade over the permitted capacity. He appealed to the Stewards of the RAC, who reversed the decision of the TT Stewards and awarded the race to McVeigh. Results: (not known until over two months after the event had been run): 1, W McVeigh (Triumph), 65.30mph; 2, BE Keys (AJS); 3, LR Archer (Velocette); 4, DG Crossley (Velocette); 5, RW Fish (Velocette); 6, WJ Jenness (Excelsior); fastest lap, W McVeigh, 34min 20sec, 65.96mph.”

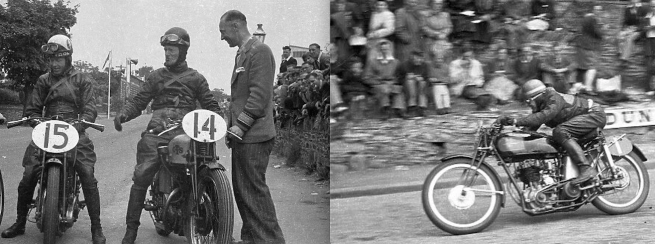

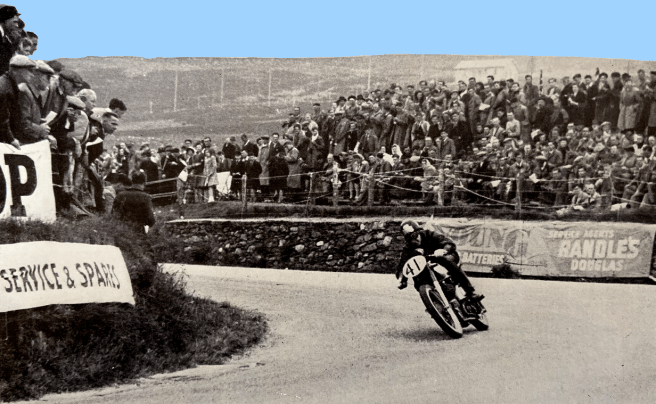

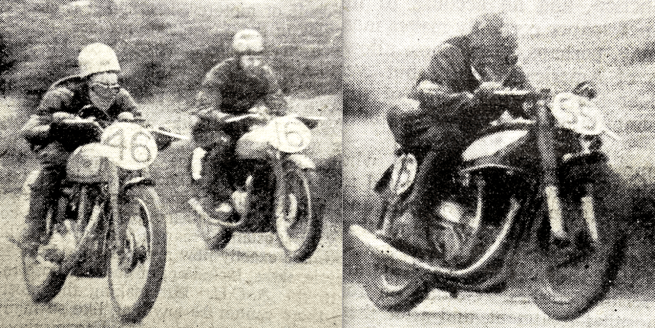

Clubman Junior

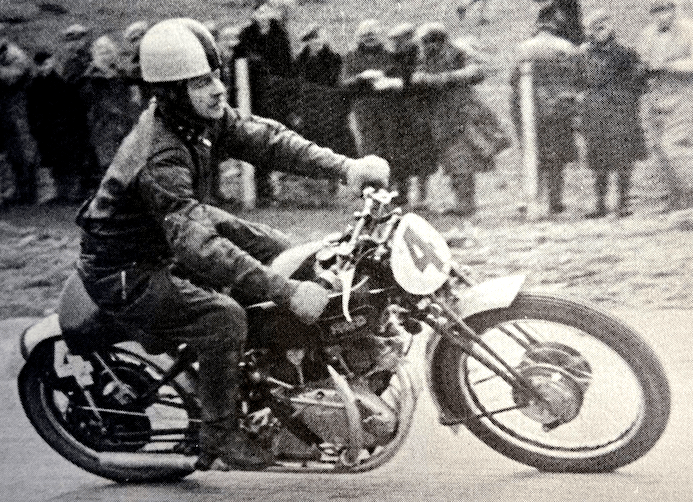

“THE JUNIOR WAS a somewhat more interesting race than the Lightweight, for 21 of the 23 entries started, and eight makes were represented—AJS (1), Ariel (2), BSA (4), Excelsior (2), Matchless (1), Norton (7), Triumph (3) and Velocette (1). Denis Parkinson (Norton) had put up the best practice lap in 31min 40sec, nearly two minutes faster than the next best, ET Pink (Norton). Denis was therefore a hot favourite,

and from the very start he proved that his supporters’ confidence was not misplaced. The first lap showed Denis in the lead by 1min 2sec. Next to him was JW Moore (BSA), third was W Sleightholme (AJS) and fourth W Evans (Matchless)—all different makes in the first four, as in the Lightweight race. In the second lap, however, Parkinson slowed down slightly, and Moore drew to within 34sec of him. Evans displaced Sleightholme in third position, and it looked as if it might be anyone’s race. The excitement, however, was short-lived, for Moore retired two miles later with gearbox trouble, and Evans broke down at Ballacraine. R Pratt (Norton), who was lying sixth at half distance, put in a third lap in 32min 55sec (including the compulsory pit-stop and kick-start) and ran through the field into second place, which he held to the finish, but, except for Moore’s challenge in the second lap, Parkinson’s lead was never really disputed, and he won by the comfortable margin of three-and-a-half minutes. Results: 1, D Parkinson (Norton), 70.74mph; 2, R Pratt (Norton); 3, W Sleightholme (AJS); 4, J Simister (Norton); 5, F Purslow (AJS); 6, R Pennycook (Norton); fastest lap, D Parkinson, 31min 3sec, 72.92mph;13 of the 21 starters finished the race.”

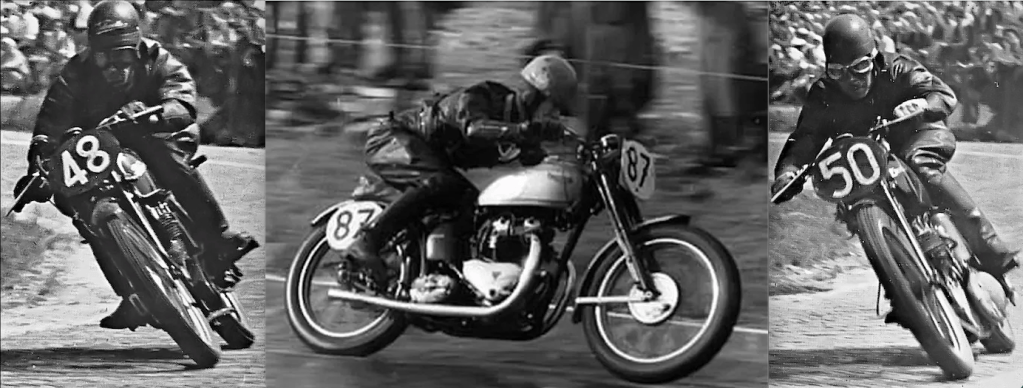

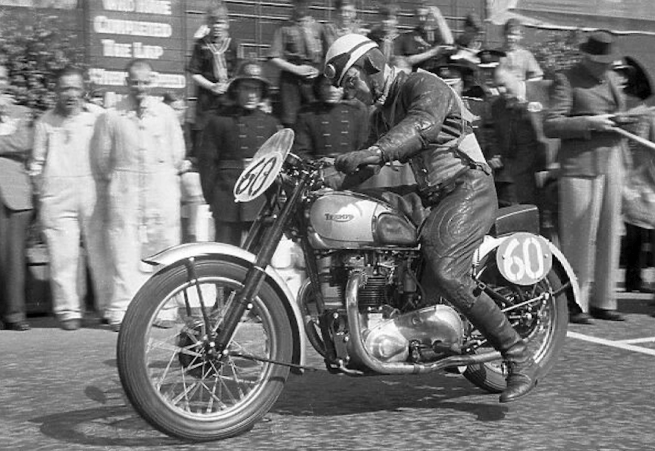

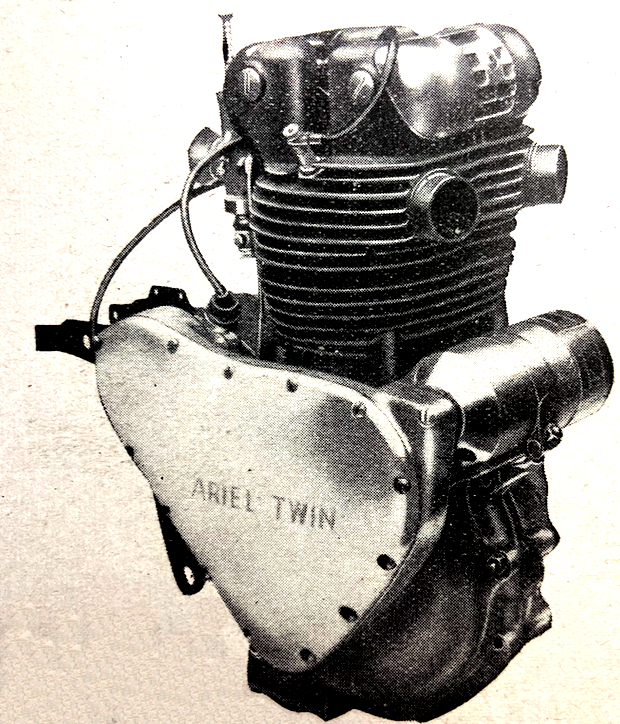

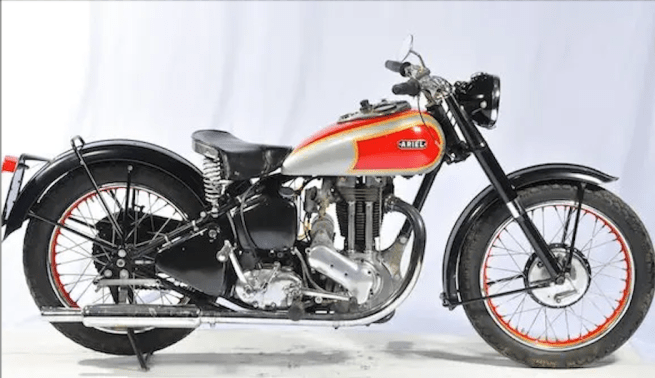

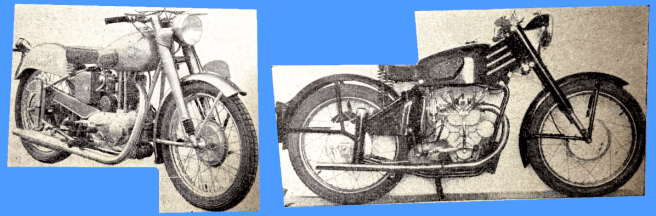

Clubman Senior

“THE ‘BIG RACE’ was not so big as had been hoped, for of the 33 entries there were no fewer than 10 non-starters. As already mentioned, these included both the ‘1,000’ Vincent HRDs, so that the only machine over the ‘International’ limit of 500cc was JH Marshall’s 600cc Scott. Still, a field of 23 was not so bad, particularly as there was a representative entry of makes—nine of them, in fact, composed of six Norton, five Triumphs, three Ariels, two AJSs, BSAs and Rudges and one Excelsior, Scott and Sunbeam. Perhaps weight tells, but that was the way they finished—Norton, Triumph, Ariel and AJS! Jack Cannell and Allan Jefferies (Triumphs) and Eric Briggs (Norton) were the joint favourites, Jack having put in a practice lap in 29min 90sec—the only rider to have lapped in under the half-hour. But one swallow doesn’t make a summer, and one fast lap doesn’t make a winner. Particularly in the big race, brakes would count almost as much as engines. Would the brakes hold out? That was the question we were all asking, for catalogue-type brakes, though sound enough for ordinary road use, had found the TT course a little trying! Curiously enough, the three favourites were each separated by three minutes on starting time, for Allan was No 36, Eric No 48 and Jack No 60, and riders were being despatched at 15sec intervals. Jack was soon in trouble—a broken petrol pipe at Ballacraine, first lap—but Eric showed that he had been keeping something up his sleeve by lapping in 28min 38sec. FP Heath (Norton) was second in 30min

22sec and Allan Jefferies third in 30min 32sec. The next three places were occupied by JE Stevens (BSA), R Tolley (Ariel) and S Lawton (Rudge)—five different makes in the first six. To make things more exciting, the three leaders were now very close together on the roads. At Kirk Michael, on the second lap Jefferies (No 36) was recorded two seconds ahead of Heath (No 39), who in turn was three seconds ahead of Briggs (No 48). (This meant, of course, that on time the order was exactly reversed, with Briggs a comfortable leader.) At the Mountain Box, Briggs was three seconds ahead of Jefferies, but Heath had dropped back, letting Allan into second position. In the second lap Stevens (BSA) and Tolley (Ariel) retired, Lawton (Rudge) moved up into fourth place behind Heath, another Ariel rider (GF Parsons) was fifth and PH Waterman (AJS) sixth—still five makes in the first six! There was no change of positions on the leaden-board in the third lap, but Eric Briggs was steadily increasing his lead, and was now 4min 1sec ahead of Allan Jeffries, over 10 minutes dividing the first six men. By the beginning of the fourth lap it was clear that, barring accidents, Briggs was the winner, with Jefferies second and Heath third. Eric made no mistake about it, and nor did Allan. But Heath ran out of petrol at the Bungalow, Lawton was delayed and Parsons brought his Ariel into third place, with Waterman (AJS) fourth. Poor Heath pushed his machine in—a distance of over seven miles—and finished—last. Results: 1, EE Briggs (Norton), 78.67mph; 2, A Jefferies (Triumph); 3, GF Parsons (Ariel); 4, PH Waterman (AJS); 5, GE Leigh (Norton); 6. F Fairbairn (Norton). Entrants of the first nine qualified for free MGP; 15 riders completed the course. Fastest lap: Eric Briggs, 80.02mph.”

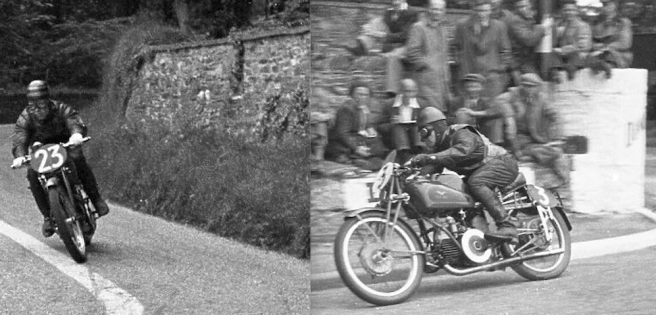

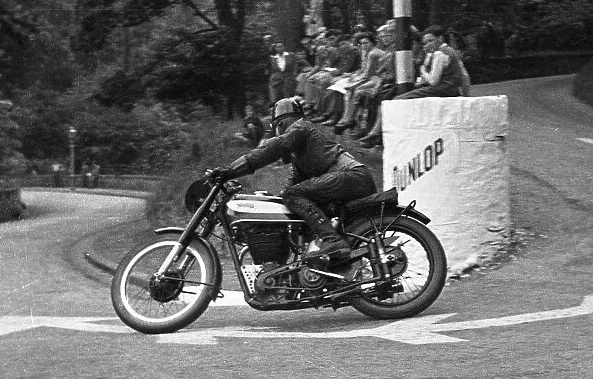

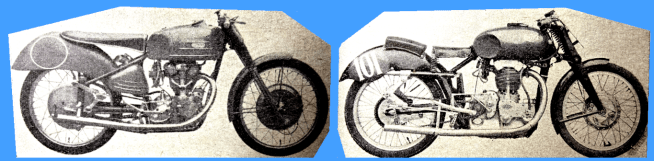

Junior TT

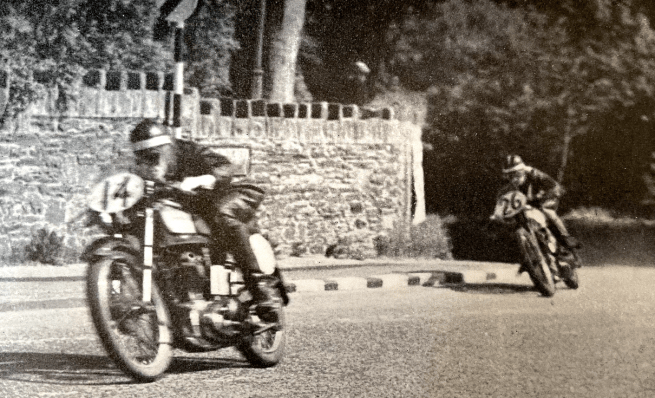

“‘BRIGHT SUNSHINE, A FIERCE Sou’ Westerly wind, perfect visibility.’ That was the weather for the 1947 Junior, the first TT race to be run since 1939. Despite gloomy prophecies that the race would be poorly supported, there were no fewer than 50 entries, mainly composed of Nortons and Velocettes. It was, in fact, a two-make TT apart from the entries of one AJS and one Excelsior. There were 28 Nortons and twenty Velocettes. The practice period had shown that any one of the leading Norton and Velocette riders might be the winner. No fast laps were put up the first morning, but on the second day out Ken Bills (Norton) recorded 29min 53sec, the only rider to do the lap in under the half-hour. This stood until the fourth period, when Bob Foster (Velocette) clocked 28min 26sec, with Harold Daniell and Artie Bell (Nortons) bracketed second at 29min 25sec, Bob’s lap being, indeed, the fastest junior of the whole practices. In the fifth period came a lap by MD Whitworth (Velocette) in 28min 38sec. Bell and Daniell were then bracketed third, while Maurice Cann and Ernie Lyons (Norton) were fifth and sixth with laps of 29min 33sec and 29min 41sec. Velocettes first and second, Norton third to sixth! In the sixth period Artie

Bell became undisputed third with a lap of 29min 13sec, but Freddie Frith and Peter Goodman (Velocettes) lapped in 29min 15sec and 29min 18sec, so pushing Harold Daniell into sixth place. Cann and Lyons were seventh and eighth. There was no change in the seventh and last practice period, so the eight fastest Juniors were Velocettes at 1, 2, 4 and 5 with Nortons at 3, 6, 7 and 8. Bob Foster led the field at 28min 26sec. It is old history now that Foster’s luck held and he had a run-away win; and, in fact, that Velocettes’ luck was in and Nortons’ was definitely out. But though Foster held the lead throughout, the race was by no means a procession. Whitworth did not reach second place until halfway through the race, while the third, fifth and sixth men home had not been within the first eight in practice. At the end of the first lap only three of these eight were on the leader-board. They were I-2-3—Foster 28min 31sec, Daniell 28min 51sec, and Cann 29min 6sec. Then came FW Fry (Velocette), T. McEwan (Norton) and J Brett (Velocette). What had happened to the other Velocette and Norton stars? Whitworth had stopped for adjustments at Ballacraine; Bell had retired at the Bungalow with chain trouble; Frith was a non-starter, due to a practice crash; Lyons had crashed at Waterworks Corner; Bills and Goodman were seventh and eighth. So in the first lap Foster led Daniell by 20 seconds, and there was just one minute dividing the first six men. In the second lap, Maurice Cann put in a time of 28min 4sec, the fastest of the day so far, and 22sec better than Foster’s best in practice. But Bob pipped it two minutes later with a lap in 27min 58sec, and for the two laps had a lead of 41sec over Maurice. Harold Daniell lay third, 18sec behind Maurice, and Fry, Brett and McEwan came next—2min 14sec between the first six men. Meanwhile Whitworth was making up for lost time, and with a terrific third lap in 27min 45sec was on the leader-board for the first

time. And not only on it, but third, out of the blue! Harold had picked up on Maurice and lay second, 1min 43sec behind. Cann was fourth and Brett was still fifth. Fry and McEwan had faded out and Peter Goodman was sixth. There were more surprises in the fourth lap. Nortons’ hopes, which lay in Daniell and Cann, were shattered when both of them packed up—Harold at Kirk Michael and Maurice at Creg-ny-Baa. Whitworth automatically moved up into second place, and third, through the field, came Scotsman JA Weddell on another Velocette. Peter Goodman was fourth—Velocettes 1-2-3 and 4. The Norton banner was taken up by Les Martin and FJ Hudson, who figured on the leader-board for the first time. And in this order they finished, without further incident except that Goodman displaced Weddell on the fifth and sixth laps, only to drop back to fourth place again in the last lap—and I had drawn him in the Hotel Sweep! Foster won by over four minutes and nearly 17 minutes separated the first six. Whitworth’s third lap in 27min 45sec (81.61mph) was the fastest of the day. Results: 1, AR Foster (Velocette), 80.31mph; 2, MD Whitworth (Velocette); 3, JA Weddell (Velocette); 4, P Goodman (Velocette); 5, LG Martin (Norton); 6, FJ Hudson (Norton); 7, G Newman (Velocette); 8, TL Wood (Velocette); (the above received first-class replicas); 9, ES Oliver (Norton); 10, GG Murdoch (Norton); 11, A0 Roger (Velocette); 12, H Hartley (Velocette); 13, R Pike (Norton); 14, HB Waddington (Norton); 15, SA Sorensen (Excelsior); 16, GH Briggs (Norton); 17, F Juhan (Velocette); 18, JW Beevers (Norton); 19, LP Hill (Norton); 20, AG Home (Norton); 21, K Bills (Norton); 22, CW Johnston (Norton); 23, F Shillings (Norton); 24, SH Goddard (Velocette); (the above received second-class replicas); 25, NB Pope (Norton); 26, WM Webster (Norton); fastest lap, D Whitworth, 27min 45sec, 81.61mph. No team qualified for either the Manufacturers’ or the

Club Team Prize.”

Lightweight TT

“ALTHOUGH THERE were only 22 entries for the 1947 Lightweight TT, five makes were represented. Exactly half the field were on Excelsiors, the remaining eleven machines being made up of four Rudges, three CTSs, two Guzzis and two New Imperials. There were two Excelsior non-starters, so of the 20 machines which started 18 were British and two were Italians. These two, however, ridden by Manliff Barrington and Maurice Cann, were undoubtedly the fastest in the race. In practice Barrington had lapped in 31min 20sec, slow by comparison with Kluge’s 1938 Lightweight record of 28min 11sec, but 59sec better than the best British lap—put up by Roland Pike (Rudge). Cann, also, had lapped in 42sec less than Pike, and, as both their machines had seemed reliable in practice, it looked as if, barring accidents, the Lightweight Trophy would once again go to an Italian machine. And so, of course, it did, but when it comes

to saying which Guzzi rider won it, I can only refer to the official records which state ‘1st M Barrington…’ The argument as to which man really won will doubtless continue as long as the TT races are remembered. The story of the race is the story of Cann and Barrington, and the also-rans. Mind you, they ran well—magnificently, some of them. I think I am right in saying that every one of the 18 British machines was at least eight years old, and that many were 10 years old and more. Against them were two superb pieces of Italian engineering, in the hands of two fine riders who knew they had the heels of the field. The only hope for the British machines was for Maurice and Manliff to break each other up—and they were for too wise to do that! Cann set off with a lap in 31 minutes dead, with Barrington 10sec behind and Les Archer (New Imperial) 58sec behind him. In the second lap Barrington was 7sec behind Cann, and in the third lap 3sec. But by the fourth lap he was 18sec behind and at the fifth lap 46sec. Les Archer was still running gamely third, but by then he was over 7min behind the leader. Then in the sixth lap, Cann had a stop, during which he fined a new valve-spring. His lap time was 31min 53sec, as against Barrington’s 31min 5sec. This let Manliff into the lead by the narrow margin of two seconds. Last lap, Maurice, to make up time lost by his stop, turned up the wick, but was recorded as lapping in 31min 31sec—only 22sec better than the sixth lap on which he stopped and, apart from this sixth lap, his slowest of the day—slower, indeed, than his replenishment lap All very odd…Barrington lapped in 30min 49sec, bringing his total time to 44sec less than Cann’s. Meanwhile Les Archer and Ben Drinkwater (Excelsior) were battling for third place. Les held it right up to the sixth lap, when he was leading Ben by 59sec. But Les was slow on the last lap (33min 15sec) and Ben was quick (31min 11sec). So Ben slipped into third place and Les dropped back to fourth. Results: 1, M Barrington (Guzzi) 73.22mph; 2. M. Can (Guzzi); 3, B Drinkwater (Excelsior); 4, LJ Archer (New Imperial); 5, WH Pike (Rudge); 6, GL Paterson (New Imperial); 7, SA Sorensen (Excelsior); 8, CW Johnston (CTS); 9, LG Martin (Excelsior); 10, J Brett (Excelsior); the above received first-class replicas; 11, WM Webster (Excelsior); fastest lap, M Cann, 30min 17sec (74.78mph).”

Senior TT

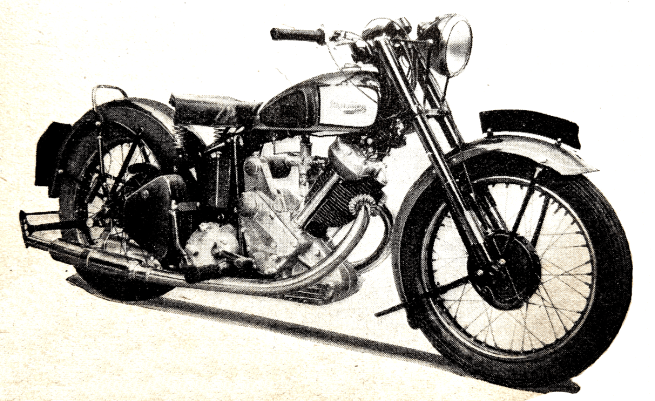

“AND SO TO THE HIGH-SPOT of the TT week—the 1947 Senior. There were only 33 entries, but we have had many fine Seniors with fewer than that. In fact, except for 1939, when there were 51 Seniors, the entry of 33 was the highest since 1935. So even the fact that there were no non-starters did not seem to matter very much. The entry of 33 was composed of 26 Norton, four Velocettes, two of the new AJS ‘parallel’ twins and Freddie Frith’s Guzzi. Unfortunately, Freddie was a non-starter, having crashed in practice. Further, two of the Velocettes were 350s. But Jock West and RL Graham on the ‘Ajays’ and Bob Foster and Peter Goodman on the pukka Velos could be relied upon to make a good race of it with the formidable Norton team, Bell, Bills and Daniell—Ernest Lyons being another non-starter, due to his crash in the Junior of the previous Monday. This was indeed a blow, for Ernie had put up fastest practice lap in 27min 8sec—forty-one seconds faster than anyone else. The practices leader-board showed the following times: 1, E Lyons (Norton) 27min 8sec; 2, AJ Bell (Norton), 27min 49sec; 3, K Bills (Norton) 27min 54sec; 4, AR Foster (Velocette) 28min 6sec; 5, JM West (AJS) 28min 9sec; 6, FL Frith (Guzzi) 28min 25sec. No sign of Harold Daniell? No, but Harold had put in a lap in 28min 43sec and had done several in under the 29min, so was obviously well in the picture. For a description of the 1947 Senior I can do no better than use the report from the TT Special, which I wrote myself on that ‘Friday the 13th’ when the leaders were changing places lap by lap, with seconds only dividing them. What a race at was, that first post-war Senior! This is what I wrote: ‘The Press Box, Friday. Since early morning the TT fans have been arriving. At 6am the weather was clear and fine, and large queues of night-voyagers were forming at the doors of restaurants.

Now they have established themselves at all the main vantage points around the course, where record crowds are reported. 10.30am. Three blasts of the klaxon—a roar of engines from the enclosure, and one by one the riders set off on their warm-up ride towards Governor’s Bridge. A glance at the list of entries shows what terrific dog-fights (I hate the phrase, but can’t find anything better!) may be expected. For example, Nos 45 and 46—Jock West and Bob Foster—and Nos 62, 63 and 64—Bills, Whitworth and Graham. 10.45am. More blasts from the klaxon. The engines are silent now, and the riders are lined up and down the road, waiting for the signal to move forward to the Start. Now an announcement about the weather: General conditions excellent—roads dry, good visibility, a slight wind. Certainly everything seems excellent from here. The mountain is not so clear as it was on Wednesday, but that is due to a slight haze, which will not worry the riders in the slightest. ‘Friday the 13th’ looks as if it would be one of the finest days the Senior has ever had. 10.50am. The riders file forward to their squares at the Start—Lightweights to the fore. All of them will be despatched before the Seniors, the first of whom, No 40—ER Evans (Norton) will not be off the mark until 11hr 9min 45sec. The Seniors can be expected to lap four to five minutes faster than the Lightweights, so the Senior should finish well before the 250 class. The Governor of the Island is starting the first post-war Senior. He takes Ebby’s flag—raises it—drops it—and Evans is away. Artie Bell next off, to the accompaniment of loud cheers. Jock West’s AJS takes a bit of starting, and Bob Foster passes him whilst he is still pushing. Groans from the crowd—and then cheers. He’s off. But his slow start has cost him 25sec at least. All get away well, then, Bills and Whitworth (Norton) being particularly quick starters. Graham’s AJS starts much easier than Jock’s. What’s happened to Jock West and Bob Foster? They’ve both been overtaken by Beevers, Myers, Christmas and Newman before Ballacraine. Obviously both the stars are in early trouble. Then comes news of Foster—he has retired at the Highlander with a “broken piston”—bad luck, Bob. Here come some more at Ballacraine—Weddell (61) and Bills (62) are there together, with Whitworth (63) and Graham (64) only a few seconds after them. Meanwhile Jock West has also reached the first station, but some time behind Graham. Stop watches now on Weddell, Bills, Whitworth and Graham at Kirk Michael. Here they are—Bills first, Whitworth next, 18sec after, then Weddell, 20sec, and then Graham, 31sec. If the clocks are correct, Bills is leading Graham by one second, on time, and Whitworth by three seconds. A close thing, this! Now how are the leaders on the road faring? Evans, Bell and Pope are all at Ramsey, but Bell is there first, so is leading the Seniors, 70sec ahead of Evans, and obviously getting close to the back numbers of the Lightweights. Bills has retained his lead in the 62, 63, 64 trio, but Graham has closed in on Whitworth, for he is shown at Ramsey only 3sec after him. Bell is at the Creg, while Harold Daniell, the last starter, is at Ramsey. Now Artie Bell flies past at the end of his first lap, having covered it, from a standing start, in 27min 16sec—83.05mph. This is only 8sec over the best practice lap, made by Ernie Lyons (Norton). Temporarily, he is first on the leader board, and it is reported that the pit signal given to him is “Go Easy”. It seems early, yet, for signals such as these—but perhaps the announcer has got it wrong. Nortons know their job! No 55, G Newman (Norton) Hallens’ entry, is going well, for he comes past close to No 48—Bill Beevers. Jock West is reported as suffering from a slipping clutch. Bad luck, Jock. Harold Daniell has put in a good lap, for he flies past us in

front of several men who started in front of him. Here are some more times—Bills 27min 35sec, Graham 27min 37sec and Whitworth 27min 56sec. Now for Harold’s time—here it is, 27min 20sec. So Bell is leading the field by four seconds—and Norton are at it again, with 1-2-3, and only 42 seconds dividing the first six men…News from Ballaugh—Clift (Norton) has passed through, presumably slowly, and says that he will be retiring at Ramsey. Ramsey reports that Waddington has proceeded off the course towards Laxey. Obviously he has retired and is coming home by the coast road. Bell is still leading the field and is now well amongst the Lightweights—in fact he is now third on the roads, for only Nos 1 and 3 in the Lightweight race are shown at the Mountain when Artie reaches it, nearly 3min ahead of Evans, who started 15sec ahead of him. Now Artie is at the Creg, having overtaken all the Lightweights except Maurice Cann (No 3), and is lying second on the roads. Then comes news that Graham (AJS) has come off at Glen Helen, but is proceeding and that Gregory (Norton) is trying to repair a trailing exhaust pipe. Here’s Artie at the end of his second lap, motor sounding fine, whilst Harold, who started 7¾min behind him, is at the Mountain. Bills is at the Creg, having drawn away from Whitworth. Artie’s second lap was done in 27min 28sec—so presumably that notice did say “Go easy”. Ken Bills (62) whizzes past as Harold (72) is shown at the Creg. And here’s Harold giving the OK sign as he passes. Bill’s second lap time is 27min 11sec—83.30mph—the fastest to be recorded so far…Only nine seconds separating the three “official” Norton riders…Graham’s crash has put him off the leader board…Meanwhile Bell must now be leading on the roads. He was recorded at the Mountain at the same time as Maurice Cann (No 3) on the Lightweight Guzzi, and should pass him by the Creg. This will be a distinct advantage to him, and if he knows that Harold has pipped him on the second lap we can expect some Irish fireworks! Here he is at the Greg—seven seconds ahead of Maurice, and has dear roads. Now Artie is at the pits for replenishments, mechanical and human, and is off again smiling, in 50sec…So Artie is back in the lead, and only five seconds separate the three now…News of Whitworth—he has retired at Ramsey, and is riding home via

Laxey. Jock West comes in after a first lap in 1hr 24min 19sec, but after a longish stop at his pit sets off again. No hope, of course, but perhaps he’s going to make the most of the TT course for test purposes He says he’s going to have a run for his money, anyway. Now back to the leaders—Artie is at the Mountain and Ken and Harold are both on the Kirk Michael-Ramsey stretch. Clocks on Ken and Harold at Ramsey. As they are Nos 62 and 72 respectively there is, of course, two and a half minutes between them on time. Here’s Ken—click the watch—and here’s Harold, 2min 27sec after him, so leading him by 3sec at Ramsey as against 2sec at the end of the third lap. Some race, this ! Norton 1, 2, 3, and 4, Velocette 5, and AJS 6. Bell flies past the its at the end of his fourth lap, and is shown at Ballacraine as Bills comes past the pits. Bills is now lying third on the roads find—wait for it!—he is leading Bell on the four laps by two seconds! Meanwhile, Harold is at Governor’s Bridge—and here he is, thumbs up. Nortons are certainly avenging themselves to-day! What a race! Harold, partly due to his quick pit stop, is in the lead again, 18sec ahead of Ken, with a fourth lap in 27min 57sec, including a pit stop! Artie Bell’s fifth lap is the fastest of the day so far—26min 56sec—at 84.07mph. George Formby in the officials’ box: “It’s chompion up here!” ” Did they go as fast as you did, in No Limit “Oh, no, not quite.”…and lots of back chat. George was introduced in person whilst one of his own records (You’ve been a terrible, terrible long time gone) was being played. His last crack was—”I’d better let myself carry on singing!” (Roars of applause.) Ken Bills tears past—Harold tears past—only about 2min behind him. So Harold is leading Ken by half-a-minute odd—and—here’s news, Harold is leading the race by 9sec, with Artie in second place. Jock West is having a ride for his money! His third lap took 27min 5sec—second fastest of the day, so far. Good enough, Jock! Peter Goodman (Velocette) is coming up. He is now only 27sec behind the third Norton rider. Whereas on lap 4, when lying fifth, he was 1min 9sec behind. His last lap, 27min 7sec, is third fastest of the day, according to our reckoning. Here’s Artie at the end of his sixth lap. He draws in for supplies and is away in 30sec. And here’s Ken Bills—stop—fill-up—and off—in 17sec. And here’s Harold—13min after Ken, and even quicker on the getaway! So Artie is leading Harold by one second! And the point is—does Harold know? If he does—if his pit attendant has worked it out from Creg-ny-Baa times, and got it over to him—we can expect fireworks on the last lap. Artie’s at Ramsey, Harold’s at Kirk Michael. Stop watches on them at the Mountain Box. Here’s Artie—and, meanwhile, news that Ken Bills has retired at Union Mills with engine trouble. That puts Peter Goodman in third place. And here’s Harold at Ramsey. Wait for him at the Bungalow. Here he is just over seven minutes behind Artie, according to the clocks, and as he started 7¾min behind him he has half-a-minute’s lead. Here comes Artie—first man to finish a post-war Senior TT race. So it’s a Norton win—whether it’s Artie or Harold. And it looks like Harold! Anyway, it’s Norton’s 20th

International TT victory! Here’s Harold’s red light at Governor’s Bridge, and here he is now flashing past the pits. According to our reckoning he’s the winner, but we wait anxiously for the official news. And when it comes—Harold has won by 22sec, at 82.81mph. His last lap, including a pit stop, has been covered in 27min 14sec. Results: 1, HL Daniell (Norton) 82.81mph; 2, AJ Bell (Norton); 3, P Goodman* (Velocette); 4, EJ Frend (Norton); 5, G Newman (Norton) 6, ER Evans (Norton); 7, N Christmas (Norton); 8, JW Beevers (Norton); 9, RL Graham (AJS); 10, LA Dear (Norton); 11, TL Wood (Velocette); (above received 1st class replicas); 12, FW Fry (Velocette); (above received a 2nd class replica); 13, HB Myers (Norton); 14, JM West (AJS). Fastest lap in the Senior was shared between Bell (Norton) and P Goodman (Velocette) with 26min 56sec (84.07mph).’ That ends my report of the race, written whilst it was being run. But a later review of the official results reveals some interesting facts. For example, Jock West’s third lap, mentioned in the report as “second fastest of the day so far”, was, in fact, the fastest of any up to and including the third lap. This was because Jock was so far behind, due to his very slow first lap, that Artie Bell had completed his fifth lap (in 26min 56sec) before Jock had completed his third! Jock’s fourth lap was better than his third—26min 59sec—and was the fastest of any up to the end of lap four. Again, Peter Goodman had a “slow” first lap—28min 16sec—if one can call 80mph on Pool petrol slow! But it was exactly a minute slower than Bell’s, and it put him out of the running for the trophy. Actually, Peter’s last six laps were the fastest six of the race—7sec faster than Harold’s and 33sec faster than Bell’s. Then it will be noticed that although Daniell, Bell and Bills occupied the first three places to the end of the sixth lap, they changed positions each lap, and indeed there was a change of leader each lap except in the fourth and fifth, which Daniell held until Bell displaced him in the sixth by one second; and that whereas they were 19sec apart on the first lap, they had closed up to 9sec on the second and only 5sec on the third—5sec between three riders after 113 miles at over 82mph. Truly it may be said that the 1947 Senior—run 40 years after that very first Senior—was a magnificent race, as vivid and exciting as any of a magnificent series.”

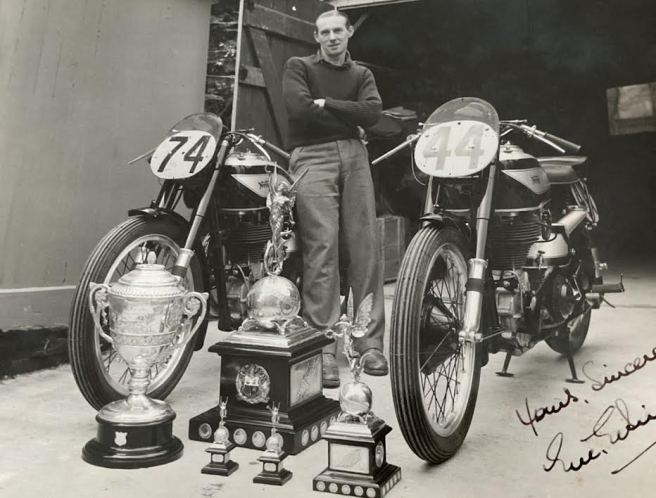

THE ONLY FOREIGN BIKE entered for the Senior TT was Freddie Frith’s Guzzi twin, which crashed out during practice, but three Guzzi singles entered the Lightweight, all with British riders. There were no foreign bikes in the Junior, though Czech ace Frans Juhan rode a Velo. The Senior, Junior and Lightweight TTs were run together (four laps for the 500s and 350s; three for the 250s). The Italians took over where they’d left off in 1939 with the wonderfully named Manliff Barrington and Maurice Cann riding their Guzzis to 1st and 2nd spots in the Lightweight TT, followed home by Ben Drinkwater’s Excelsior. It was also business as usual in the Junior with a hat-trick for Velocette, courtesy of Messrs Foster, Whitworth and Weddell. In fact there were six Velos in the top 10, with four Nortons to ram the home the British-is-best message. BMW, having won the 1939 Senior with its blown twin, was conspicuously absent leaving Harold Daniel to lead the 500s home on his Manx Norton with TT debutant Artie Bell just 22 seconds behind him on another Norton. Also racing on the Island for the first time was Peter Goodman, grandson of Velocette’s founder, who was third on his KTT. Nortons filled the rest of the top 10 places, apart from an Ajay in 9th spot. Brits also dominated the Clubman’s TT. First three home in the Senior were Norton, Triump and Ariel; Junior, Norton, Norton AJS; Lightweight, AJS, Velo, Velo. Clubman’s Senior TT winner Eric Briggs had a good year; he returned to the Island for the Manx where was managed a Senior/Junior double to win three Mountain Course races within three months.

* Peter Goodman, with a creditable third place in the Senior in his first TT appearance, was a grandson of Velocette’s founder.

TT STARS WHO DIDN’T survive the war included aircrew Walter Rusk and Wal Handley; the blitz had done for Zenith Gradua rider Freddie Barnes, whose first race on the Isle of Man was the 1905 trial for the International Cup Race.

KIYOSHI KAWASHIMA BECAME the first Honda employee to boast an engineering degree—not that Honda could afford a salary to match his qualification. Years later Kawashima recalled: “Well, frankly, it was 1947, wasn’t it? It was the peak of unemployment. At that point, I didn’t care what the pay was. Just so I could do the work of an engineer, the company didn’t matter to me. The Old Man was a famous engineer in Hamamatsu, and this was a chance to work at his place. Also, my home was…only a five-minute walk to work…Then, when I came in, my first job was modifying wireless radio generator engines. About ten of them would be hauled in on Monday every week, and I would take off the generator mechanism and dismantle the engine. On Tuesday, I would clean all the pieces. On Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, I would work on the parts, and on Saturday put them together. Saturday afternoon, I would attach the engines to the bicycles and take them for test rides. I say test rides, but all I did, really, was ride them up a hill in the neighbourhood…About the time that was done, a large group of peddlers…and even some very suspicious-looking black-market-type brokers would be waiting there. They would stuff about two engines each in their rucksacks and carry them away to Tokyo, Osaka, and all over the country. After paying in advance. I would see a wad of bills and think to myself, it looks like I’ll get paid this month, my wages won’t be delayed, and I’d feel very happy…”

FUEL SHORTAGES RULED OUT running the traditional long-distance trials so the organisers ran truncated events with the London-Land’s End starting at Taunton and the Scottish Six Days Trial was based on Fort William rather than Edinburgh (Hugh Viney scored the first of thee consecutive SSDT victories for AJS).

“AS A MOTOR CYCLIST of 20 years ‘wheeling’ it is my considered opinion that the well-used expression, ‘Racing improves the Breed’, is 100% true. I have, with one or two small breaks, ridden Rudges since 1928, and my present mount, a ’37 Ulster, is the best of them all. It has inherent in its design all those attributes which proved their worth in the Island, and which are no less necessary on the road in all weathers for the average enthusiast. Roadholding, steering, braking and mechanical reliability are not just advertisements, they are the things which make all the difference between a motor cycle and a race-bred mount. Living in industrial Lancashire and travelling daily to Manchester, Salford or the surrounding districts, demands ‘handleability’ for peace of mind, and, believe me, a Rudge makes such tranquillity commonplace. What a tragedy that these grand machines are no more! What of the future? After seeing Ernie Lyons doing a spot of fast motoring last September on a Triumph, surely the Triumph Co are not going to rest on their laurels? This machine is good. Given that little extra, which can only be acquired in the IoM, it should become absolutely superb, and there is no doubt that the days of the single are numbered in the 500cc racing field. I believe that it is not necessary to win a TT for a make to be successful. The very fact that they are entered is sufficient to show that the manufacturers are alive to the benefits which racing can bestow on their products. And so I say to all British manufacturers—support a racing policy, end let us see once again annually that welcome copy of The Motor Cycle which had at the top, ‘British Supremacy Number’.

T Roy Pearson, Chadderton, Lancs.”

“I CANNOT RECALL having seen any letters on the subject of sidecar acrobatics from the gentleman mostly concerned, ie, the passenger himself. Well, apart from the possible effect on sidecar design, etc, which the banning of such a practice would have, I reckon that the sporting side should not be neglected. As an ex-performer of these acrobatics I say let those who want to do it, do it! I know I enjoyed every second that I spent in (and out!) of the the ‘chair’, and the thought of myself being replaced by sandbags horrifies me. However, perhaps other passengers will be taking up the pen soon in support (I hope) of my plea—keep it as it is! After all, these passengers needn’t do it, so they must like doing it. as I did.

V Morton, Tunbridge Wells.”

“I own a 250 side-valve, but at some time in the future I most certainly want a bigger machine. But it must be a side-valve. So I gaze longingly in shop windows looking for a new 500 or 600cc side-valve, and I am disappointed. Now I do not ask for much. I do not demand side-valve twins. But how about a few comfortable side-valves for those of us who do not take a joy in spending hours mucking about with valve-gear and suchlike?

D Reed, London, NW1.”

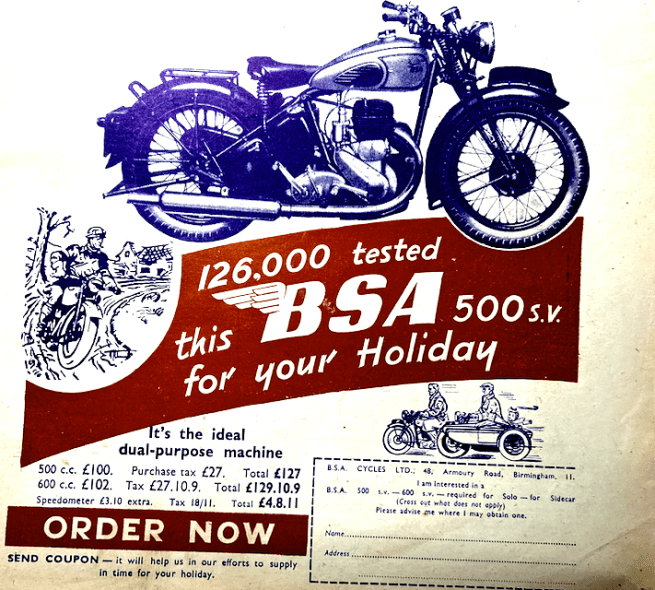

“PRICES OF BSA models have been increased: C10, 250cc sv, £107 19s 0d; C11, 250cc ohv, £114 6s 0d; B31, 350cc ohv, £142 4s 10d; B32, 350cc ohv, £157 9s 7d; B33, 500cc ohv, £154 18s 10d; B34, 500cc ohv, £170 3s 7d; M20, 500cc sv, £142 4s 10d; M21, 600cc sv, £146 1s 0d; A7, 500cc ohv Twin, £177 16s 0d; Speedometer, £5 1s 8d.”

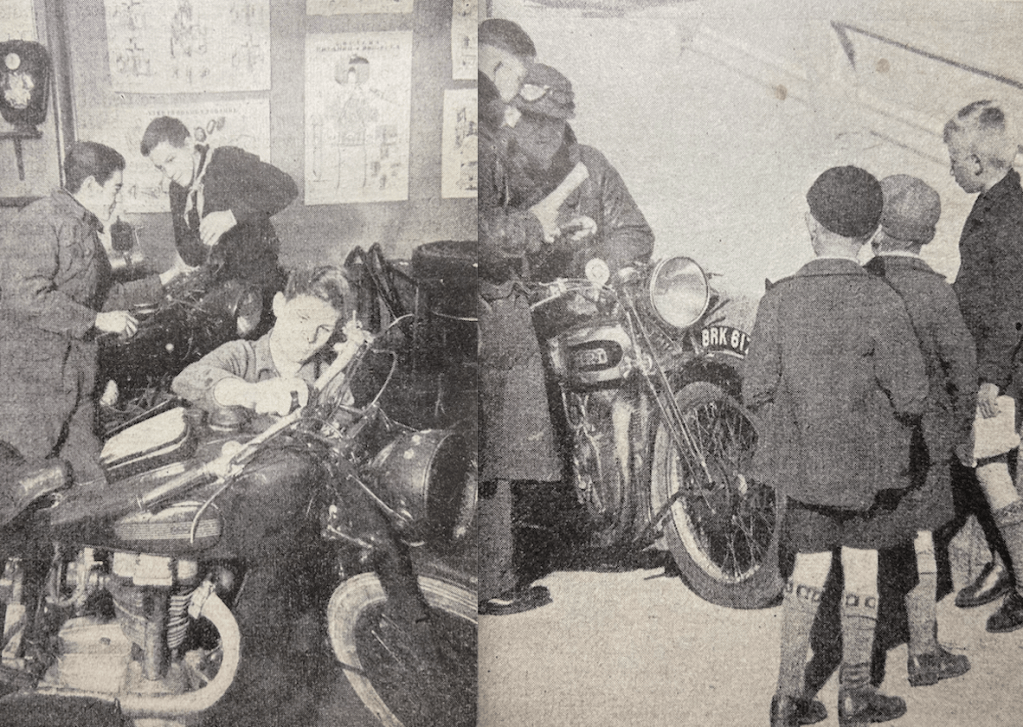

ANY WELL-HEELED 16-YEAR-OLD with a provisional licence could slap L-plates on a ton-up big twin so there was clearly a need for some form of rider training. The RAC-ACU Learner Training Scheme was set up with money from the government and the RAC but the training centres that sprang up all over the country were operated by local ACU clubmen. Novices were taught machine control, often on out-of-hours school playgrounds, using their own bikes or lightweights donated by an industry keen to be seen doing its bit for road safety. The enthusiasts who staffed the RAC/ACU scheme also brought newbies up to speed on everything from roadcraft and riding gear to basic maintenance.

AND JUST AS THE keen trainees were looking forward to their first taste of two-wheeled freedom the paltry petrol ration was withdrawn. Motor cycles being recommissioned by riders home from the war went back into storage unless their owners were lucky enough to qualify for ‘essential use’ petrol coupons. With no petrol it wasn’t easy to sell bikes and competition ground to a halt.

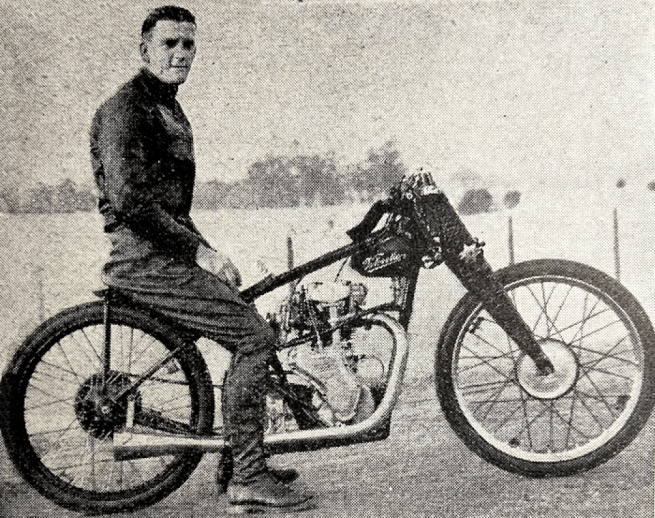

ICE RACING WAS REVIVED in Scandinavia but Russia took the lead in developing the sport, switching events from frozen lakes to pukka stadiums which were flooded and frozen for events. Initially they used modified road bikes but as the sport evolved specialised ice-racers were adopted powered by JAO and later Czech-made ESO lumps.

“THE CUMBERLAND COUNTY MCC organised their annual Easter open scramble on Lazonby Fell, near Penrith. In the final of the 350cc race over seven laps of the fast, undulating moorland course, EC Bessant (Matchless) streaked into the lead at the start, closely followed by E Ogden (Triumph), RB Young (BSA) and Sgmn RF Croft, of the R Sigs, riding an Army-type Matchless. Bessant held his lead of some 150 yards to the finish, although Ogden did his best to challenge him. The seven-lap 250cc race proved to be the most exciting event of the afternoon. AA Todd (Velocette) took the lead at the start, with J Carruthers (Velocette) and J Forster (Velocette) gradually forcing the pace. At half distance Carruthers passed Todd, who had an anxious moment in the deep, boggy section. Todd swept past both of his rivals on the straight section after the quarry. 250 Cup: AA Todd (Velocette); 2, J Forster (Velocette); 3, J Carruthers (Velocette). 350 Cup: 1, EC Bessant (Matchless); 2, E Ogden (Triumph); 3, RB Young (BSA.). There were 45 entries for the unlimited cc race over 12 laps but many entrants failed to turn up for the first two heats over three laps. In the final everyone was surprised to see Cliff Holden’s white crash helmet leading a howling bunch of machines towards the bog. Bessant, for once, made a bad start. E Ogden passed Holden after the first lap, and the crowd murmured with excitement when Bessant, going like the wind, passed 12 riders in the first lap. At quarter distance Bessant’s red-and-white chequered helmet was right behind Ogden, who desperately strove to resist the challenge. Bessant passed Ogden on the sixth lap, and steadily increased his lead to the end. Ivan Carr Cup and Unlimited Cup: EC Bessant (Matchless); 2, E Ogden (Triumph); 3, RB Young (BSA). Best Performance by Cumberland County Member: WH Millburn (BSA).

Most of the material in this timeline is culled from the pages of The Motor Cycle but I’ve also accumulated issues of Motor Cycling, whence comes the following:

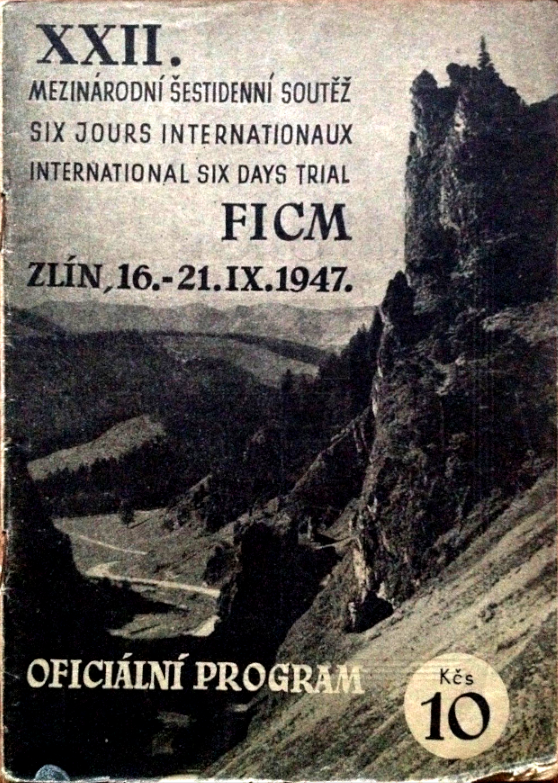

“OUR MANUFACTURERS HAVE unanimously decided, albeit with regret, to withhold their support from the 1947 International Six Days’ Trial. Their regret will be shared by all sportsmen in this country for the decision implies the absence of a British team from the Trophy contest…In a statement issued by the Manufacturers’ Union it is made abundantly clear that its members had as their only alternative the production of machines which could not be adequately prepared in the time available. The decision will almost certainly be misinterpreted on the Continent. That is unfortunate, but the truth is the organisers have themselves to blame for the absence of official British entries. Had the Czech Auto Club refrained from modifying the basic regulations agreed upon last April at the FICM San Remo conference, or even had notification of the intention to make such modification been sent to the Auto-Cycle Union by a reasonably early date, all would have been well. Instead, an inexplicable delay in delivery of those regulations has placed the British industry under an unreasonable handicap and one which it has rightly declined to accept. It may be asked why absence of trade support should deny Great Britain official representation in this important event. The answer is simple; the Trophy competition by its very nature has always been regarded as a contest between national motorcycles rather than national motorcyclists [trivial typographical note: the Blue ‘Un saw ‘motor cycle’ as two words; the Green ‘Un saw ‘motorcycle’ as one word. As a former staffer of Motor Cycle Weekly, which was The Motor Cycle under another name, I have stuck to the old style that gave us MCC rather than MC; another seemingly trivial difference that has attained unexpected importance…but that’s another story, which traces its roots to the next story—Ed]. Thus it is essential that any team representing this country should be mounted upon the best machines we can produce most suited to the regulations. Therein lies the reason for our manufacturers’ decision. The modified regulations favour the 250cc mount and there is insufficient time to produce the best possible British machines of this capacity. To gain a true appreciation of the position it is only necessary to imagine that Great Britain had organised the trial and had evolved a set of rules favouring the 350cc machine. Had this been the case we believe that neither Czechoslovakia nor Italy would have found it simple to produce in the time available models comparable to our own, as machines of this capacity can be regarded as the Cinderellas of the Continental factories.”

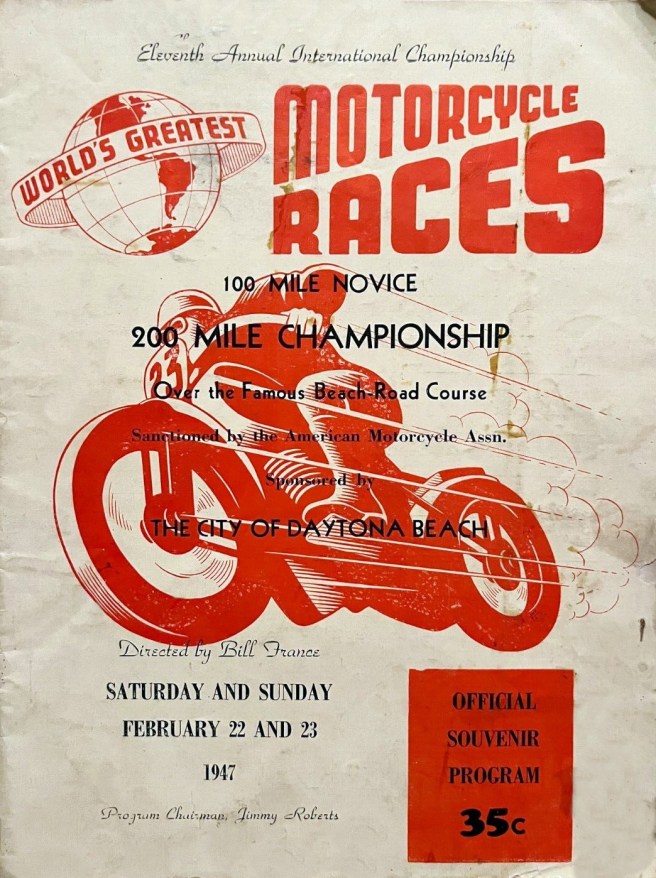

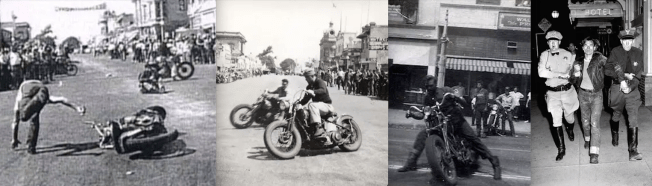

“THE AMERICAN MOTORCYCLE ASSOCIATION is the A-CU’s opposite number in the United States. Apparently there was something sadly lacking in the way in which it handled the organisation of its 1947 Gypsy Tour. So much is strongly suggested in a report that has lately been sent in by one of our readers in California. This annual event, which is very roughly the equivalent of our own National Rally, although run on somewhat different lines, is a very old-established fixture, and the name was, no doubt, inspired by the Motor Cycling Gypsy Club, which was in its heyday in the period immediately preceding the 1914 war. This year, it seems, the Gypsy Tour finished at a town called Hollister, somewhere in the neighbourhood of San Francisco, and an account of the affair published in the local newspaper certainly makes most remarkable reading. One may, perhaps, make some allowance for the sensationalism of American reports, but even after doing so, it seems clear that the final stage of this event was allowed to degenerate into an orgy that was both disgusting and disgraceful. What appears to have happened was that the riders, who came from all over the United States, and are estimated to have numbered about 4,000, got completely out of hand and terrorised the entire town. Bars were wrecked and that kind of thing, while some enthusiasts thought it funny to ignore completely the local traffic regulations, which naturally led to a number of serious crashes. Getting on for 60 people had to receive hospital treatment, and after they had regained control of the situation the police made a number of arrests. One youth committed an offence which landed him in the county gaol for 90 days, which is just one indication of the kind of things that allegedly went on. The inevitable result of this affair will be that motorcycling will be branded as a rough-neck sport so far as that locality is concerned, and the news will doubtless spread to other parts of the country. Unless the AMA takes effective steps to tighten up its organisation, particularly as regards the discipline of competitors, it must expect severe repercussions from this outburst of hooliganism.”

SEEMINGLY WELL-INFORMED US sources indicate that during the 1930s Hollister had hosted AMA sanctioned races organised by the Salinas Ramblers MC. Spectators participated in the ‘Gypsy Tour’ organised by the AMA and, as attendance grew, the Memorial Day races became as important to the local economy as the Hollister Livestock Show or the Hollister Rodeo. The races were discontinued after America’s entry into the war. When they returned in 1947 local merchants welcomed the event. Many more motor cyclists than expected poured into Hollister and things did get out of hand. About 60 riders were treated for injuries at the local hospital; 47 were charged with minor offences such as public drunkenness, disorderly conduct and reckless driving; most of them were held for only a few hours. There were no destruction of property, no arson, no looting; no citizens were harmed. On the Sunday 40 California Highway Patrol officers arrived with threats of tear gas; the motor cyclists went home. A City Council member stated, “Luckily, there appears to be no serious damage. These trick riders did more harm to themselves than the town.” It couldn’t have been that bad, five months later the town agreed to let the AMA and the Salinas Ramblers host the races again. But the San Francisco Chronicle used the headline “Havoc in Hollister”. Legend has it that he AMA released a statement saying that they had no involvement with the Hollister riot, and, “the trouble was caused by the 1% deviant that tarnishes the public image of both motorcycles and motorcyclists” and that the other 99% of motorcyclists are good, decent, law-abiding citizens”. The AMA denies saying any such thing but myth has overtaken reality and ‘bikers’ around the world wear 1% badges for no apparent reason. Six years later Marlon Brando and Lee Marvin starred in The Wild One which helped spread the image of the ‘outlaw biker’. Films, books, magazine all jumped on the bandwagon, doing incalculable harm to the image of motor cycles and motor cycling. Enough said; let’s get back to motor cycling.

“UNTIL OUR OWN TIMES any road recognised as public was open to the use of all and sundry, by whatever means they cared to travel, and quite irrespective of its nature or condition. In recent years moves have been made, sometimes successfully and sometimes not, to close highways altogether, if not to the general public at any rate to motor users. Now the thing has started it is not easy to see where it is going to stop, unless every attempt of the kind is resisted to the utmost. Countless footpaths all over the country have been lost to ramblers for ever in the course of the past half-century or so, simply because people did not realise just what was happening, or did not care. Unless road users keep a watch on their privileges they are in danger of being barred from the use of many other pleasant by-ways.”

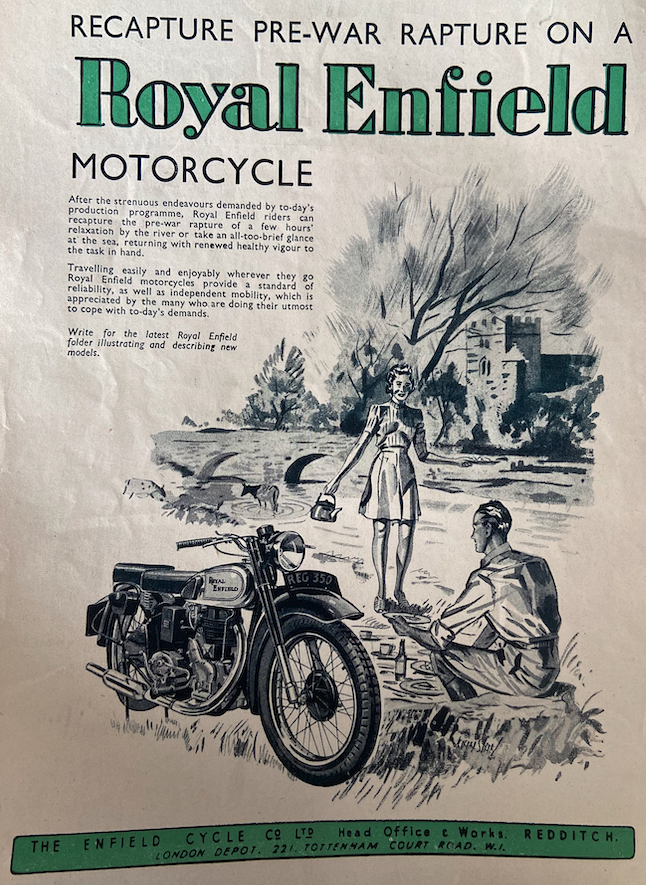

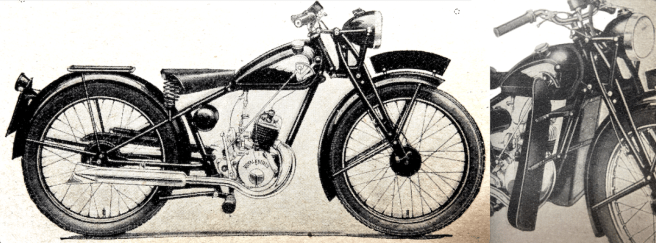

“THE ENFIELD CYCLE CO has produced a magnificent brochure containing a record of its war effort. The whole thing is done in photogravure in two colours, and to many of its recipients it will no doubt come as a revelation of the ramifications of the Redditch firm, and the variety of its wartime products. It had no fewer than five factories in operation, including one 90ft below the ground, away in Wiltshire, and besides cycles and motorcycles and engines of various types, it turned out such things as predictors for anti-aircraft work and gyroscopic sights for various guns, including the Oerlikon.”

“OCCASIONALLY ONE SEES registration numbers containing an unconscious element of humour. Recently, in London, I noticed an autocycle bearing plates with the letters LPA as part of the index number and to complete the picture the proud owner had his feet on a pair of old-style auxiliary footrests, fitted well forward, and was wearing one of those caps with the peak at the back. For the benefit of the uninitiated, of course, I had better explain that the letters quoted used, in the early days, to signify ‘Light Pedal Assistance’—which was, more often than not. anything but light.” [Ixion believed that the heating caused by LPA uphill, followed by rapid cooling on the reverse slope, wrecked the health of many pioneer motor cyclists—Ed.]