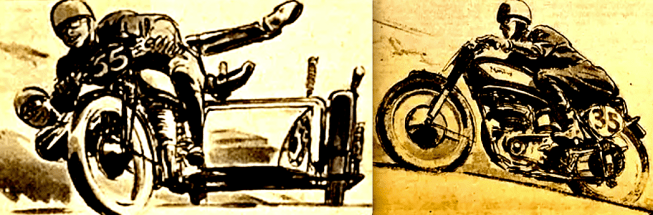

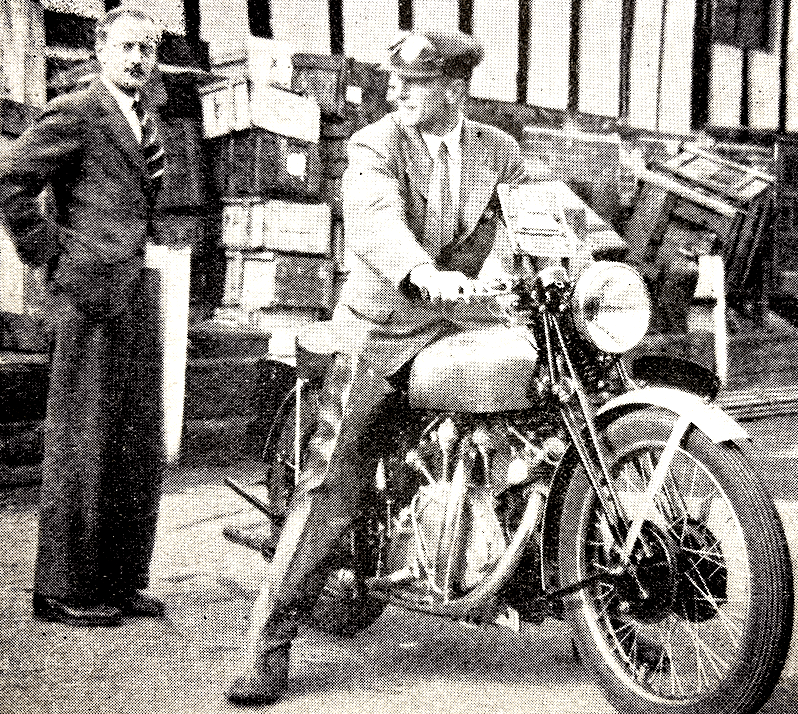

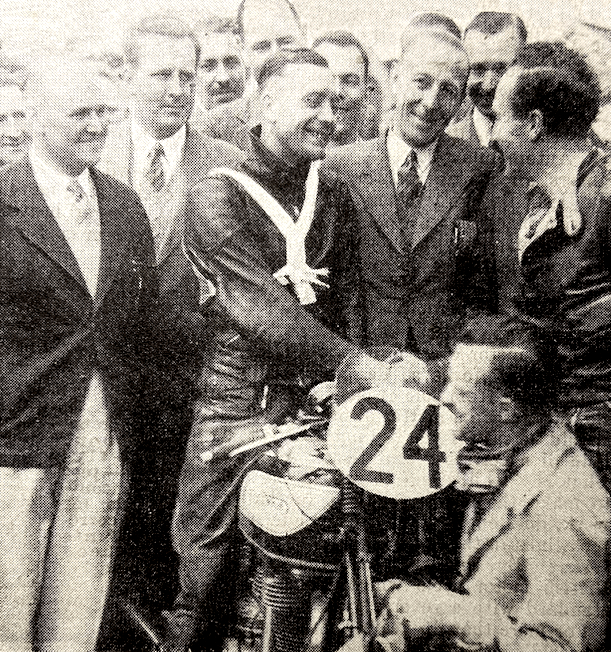

“LAST THURSDAY I SETTLED down to run through the New Year’s Honours…As my eyes roamed through the awards of the OBG (Military Division) to the members of the Royal Air Force I came to a halt. What brought me to a stop was the award of the OBE to Wing-Commander JM West, RAFVR. There could be more than one JM West with that rank in the RAF but it seemed very unlikely. Jock West, second in the last TT, new sales manager of Associated Motor Cycles, OBE—cheers! The Editor ‘phoned Jock to congratulate him. He had not heard—was completely taken aback. Just like Jock, he told no one about the honour At the AMC victory party and dance last Saturday evening—a mighty and cheery get-together of those who work at the factory, run by the AMC Entertainment Committee—no one knew until the Editor mentioned it. Incidentally, what an outstanding get-together that party was! And what an excellent band AMC boast. Why don’t more big firms have their cheery off-moments?”

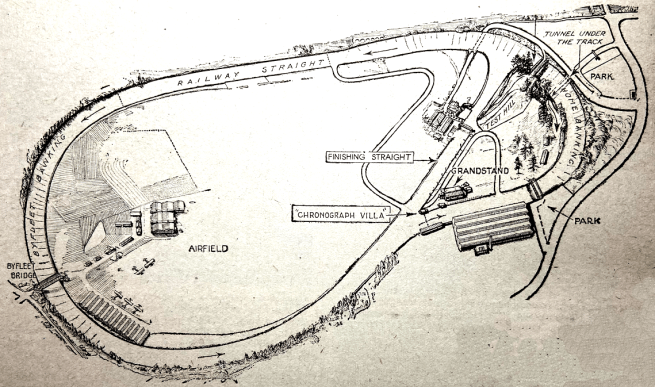

“SHAREHOLDERS OF BROOKLANDS (Weybridge), Ltd, last Monday approved the sale of Brooklands to Vickers-Armstrongs for £330,000. A proposal to adjourn the meeting in order that other lines of action might be explored was defeated The chairman, Mr CW Hayward, stated that the Ministry of Aircraft Production had declared that the present requisition would be continued for an indefinite number of years up to a maximum of five, and that they would feel bound during that period to consider compulsory acquisition. He was, he said, satisfied that there was no chance of Brooklands ever coming back to the company as a motor-racing course.”

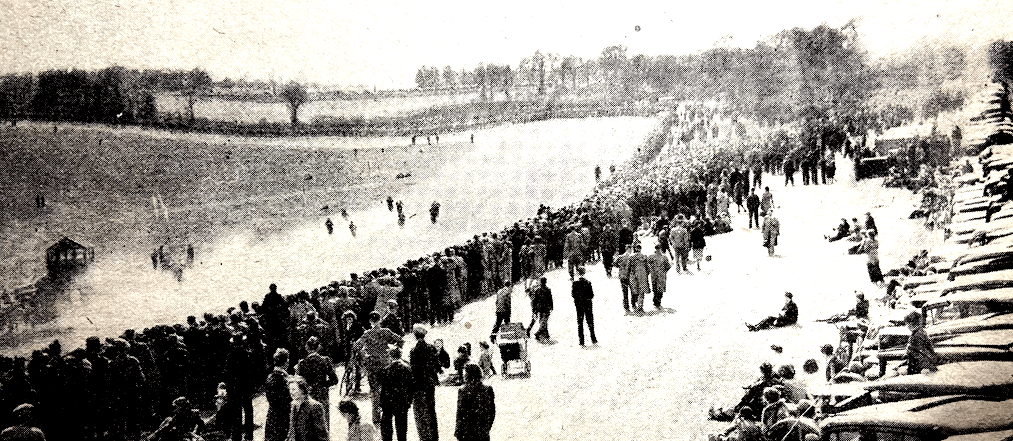

“WITH BROOKLANDS SOLD and the track presumably no longer available, where will the British motor and motor cycle industries be able to carry out necessary research? In the past Brooklands has been Britain’s only track—the sole place where it has been possible to test vehicles at speed unimpeded by corners, bends and traffic. The sale and loss of the track therefore cannot be regarded with equanimity from the national aspect, especially to-day, with post-war designs in the offing. The fact that a great sporting venue will be lost is secondary and can weigh little, though even in that connection there can be grave regret, for Brooklands has been a great training medium, developing men—real men—as well as machines.”

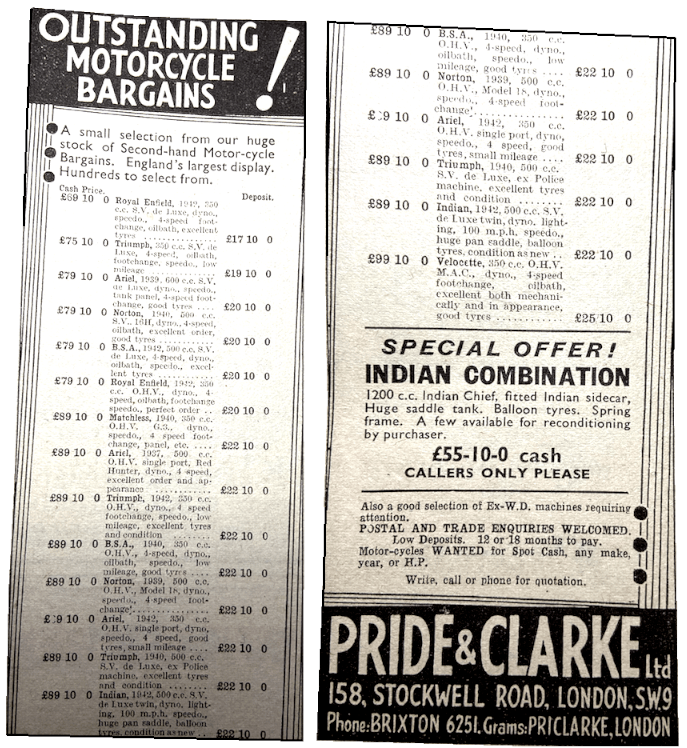

“PERHAPS THE QUESTION which agitates most of us is whether the towering prices of 1945 are going to be permanent or not? We have lived so long in an era when £65 was a typical price for a tolerably good 500cc that we gasp and worry when the figure sticks at nearer £150. After the 1918 armistice prices steepled for a year or two but in due course slid down again until we could say we got better than pre-war value for less than pre-war prices. Will that process repeat itself? No man knows. Purchase tax will assuredly disappear in time. For the rest, prophecy is probably more of a gamble than at any time in our history. The American loan discussions have prepared us for a certain doubt, or even pessimism, concerning our financial future. For the moment only two remarks are sound and relevant. The first is that price and wages stand in a definite ratio. The symbol ‘£’ is in a sense a mere convention. A £50 bike when Jack’s weekly wage was £3 was no cheaper than a £100 bike when Jack’s weekly wage is £6. On paper we earn more to-day. On paper we spend more. The second is that if as a nation we work hard, are well governed, and are led by competent industrialists, we shall unquestionably emerge from the slough of being a ‘debtor’ nation, so embarrassing after many long decades as a world creditor. But those three ‘ifs’—work, government and technical leadership—are the conditions of prosperity. Them are no other conditions. As a profound believer in Britain, I expect to see a good £50 bike return (or its equivalent at some other financial level). But I do not expect it by to-morrow about this time. And as a buyer, I shall not wait so long to pick my post-war mount.”—Ixion

“IN THE FEW STARTLED DAYS since the sale of Brooklands was announced, three separate reactions have been noticeable amongst motor cyclists. The leading engineers bemoan the loss of what one of them called ‘the best test bench in the world’ available to the motor cycle industry at absurdly low cost. Riders feel bereft of the one place in the British Isles where on almost any day in the year they could travel as fast as all but freak bikes are capable of travelling. The general public, though not many of them visited Brooklands more than once or twice a year, regarded it affectionately in much the same light as Epsom or Lord’s or Wembley Stadium. In these three senses we all feel an acute sense of loss. On the other hand, if we assume that Britain’s recovery will ultimately include an even better track, more suited to ‘laboratory’ work, better adapted for pure sport, and designed with a shrewder eye to the spectacular side, our period of mourning would be definitely eased. One thing is certain. Britain cannot afford to remain trackless while Italy has Monza, France has Montlhèry and Germany has Avus and the Nurburg Ring.”—Ixion

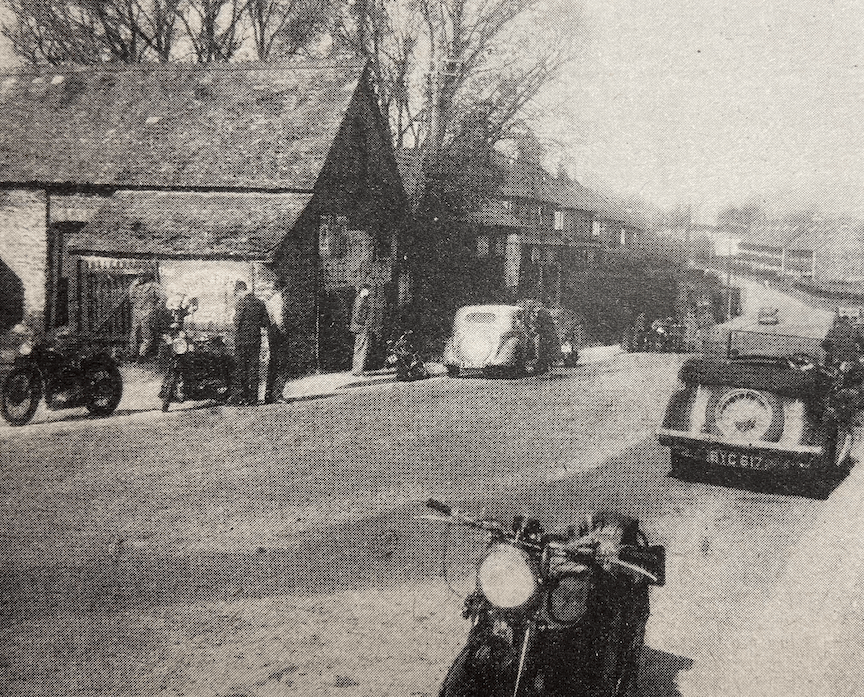

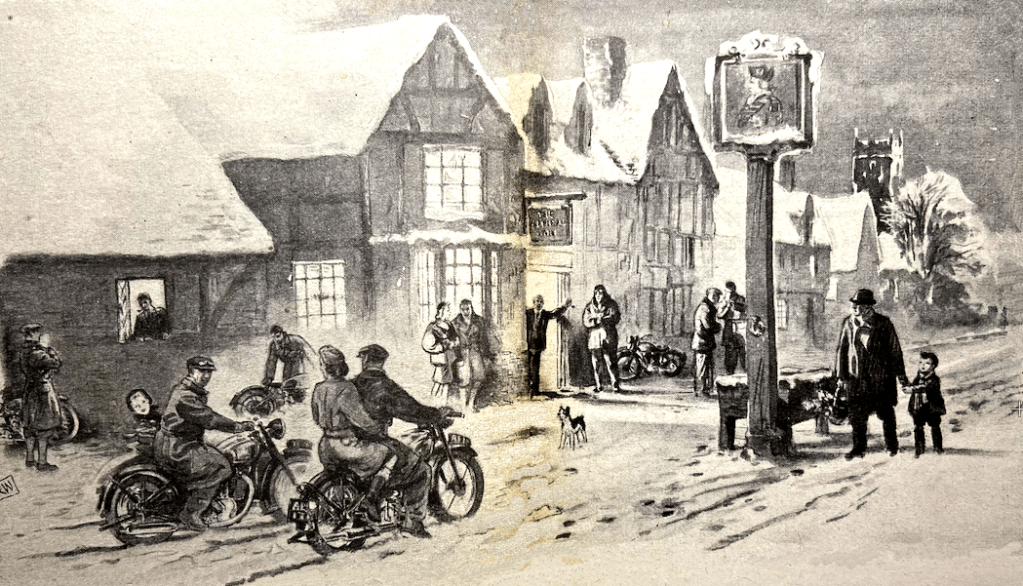

“SO BROOKLANDS IS NO MORE! I trust an abler pen than mine will write a suitable lament, but just in case nobody else thinks of it, I’d like to say that here is one who will be everlastingly grateful to the track, and all connected with it, for presenting motor cycling at its best. I would hesitate to say that even the TT has given me more enjoyment—though more thrills, perhaps. At Brooklands you could (1) study the machines in the paddock to your heart’s content; (2) get a splendid view of the racing from half a dozen different places without taking up position long beforehand; (3) see the fastest machines in Britain. The Mountain formed a natural grandstand for the Campbell and Mountain circuits, and for another kind of thrill you could mount the stand at the paddock and look down on the rider’s bobbing heads as their handlebars swept the paint off the woodwork beneath. The ride to and from the track, too, could be very pleasant, taking one perhaps over rhododendron heaths or pine-clad hills, past half-timbered cottages and through typically bright south-country villages—even Chobham and Byfleet, quite close to the track, I thought very charming. Latterly I found admission quite cheap, but in the twenties it was well worth 3s charged, for those were the days of Le Vack and Temple, O’Donovan and Pullin, Horsman, Judd, Emerson, Marchant—when even scratch races were well supported and when nearly all world’s records were broken at the Track. Southern racing men will miss Brooklands. I hope it won’t be long before a new track is planned (with the co-operation of the car people)—one permitting two-wheeled speeds of 200mph or more.

Footboard Ferdie, Newport.”

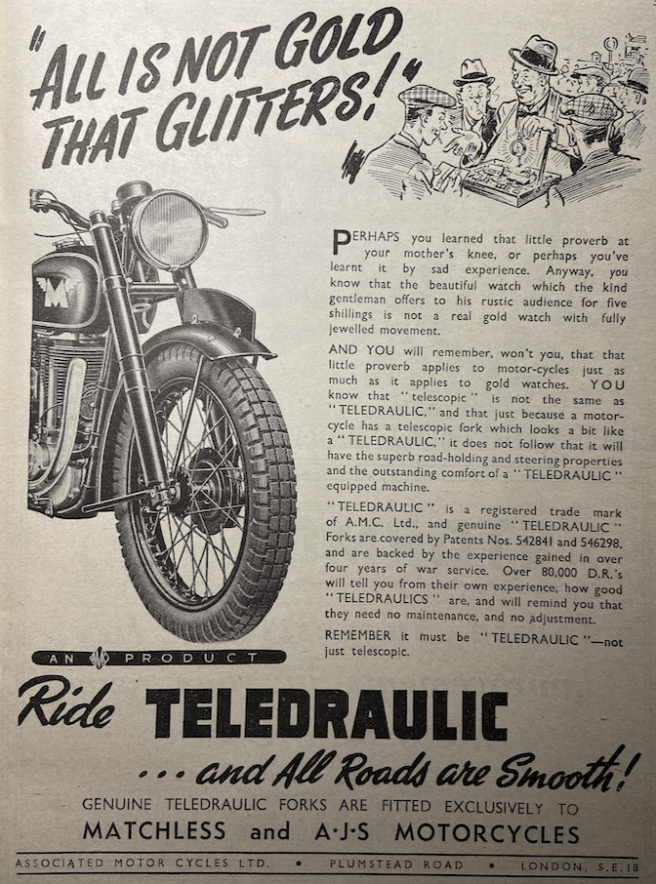

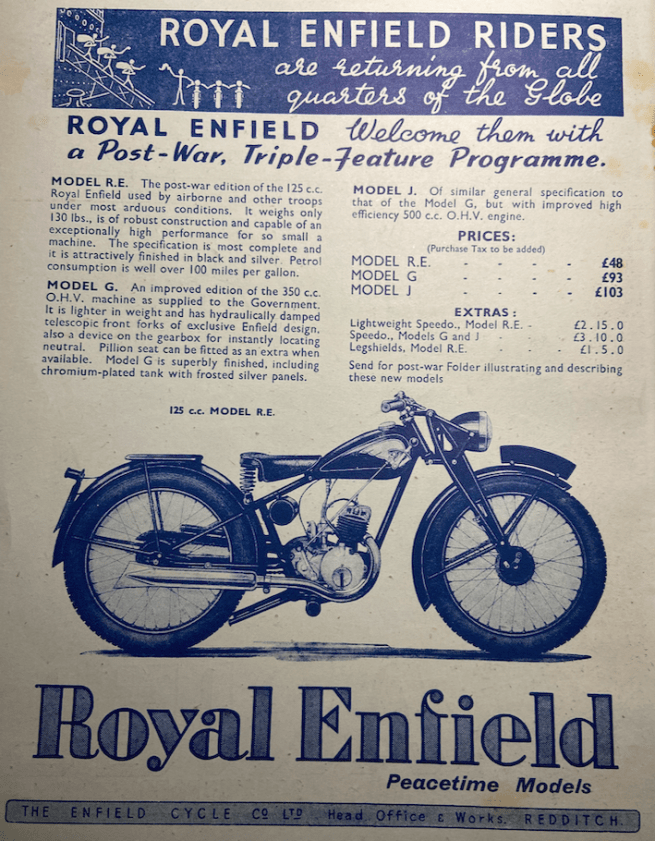

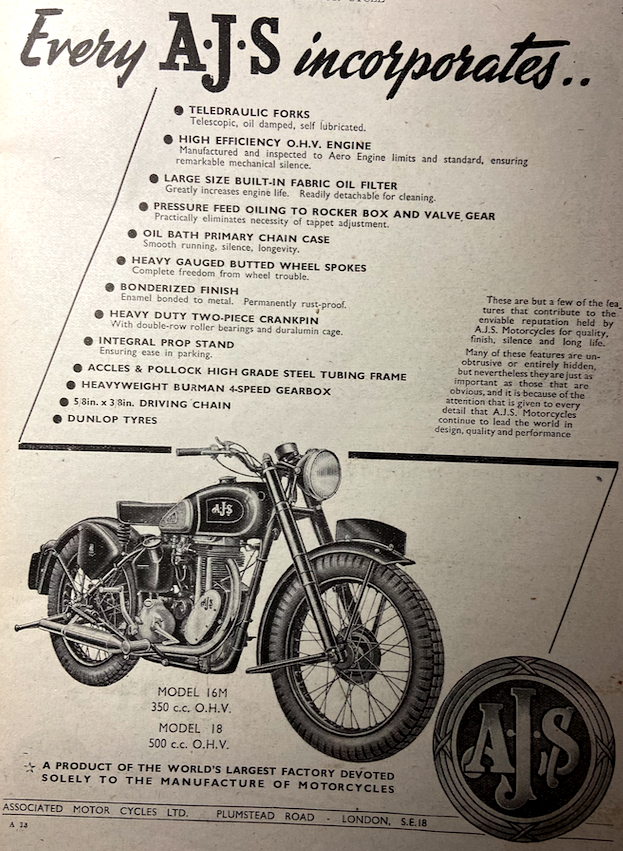

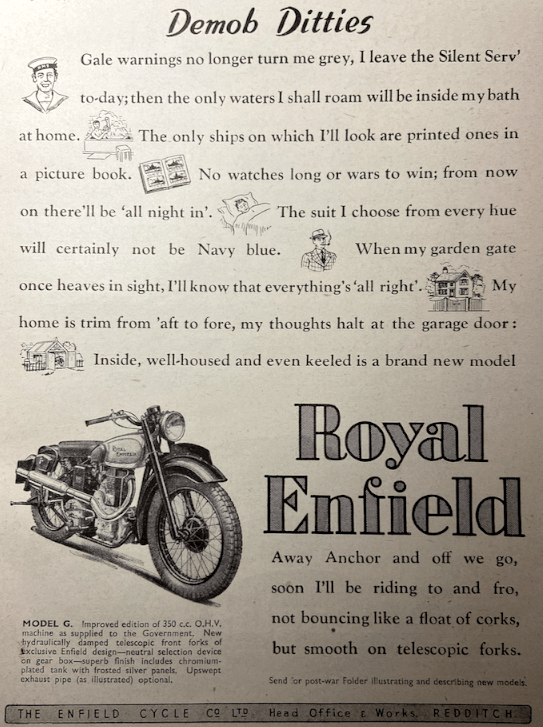

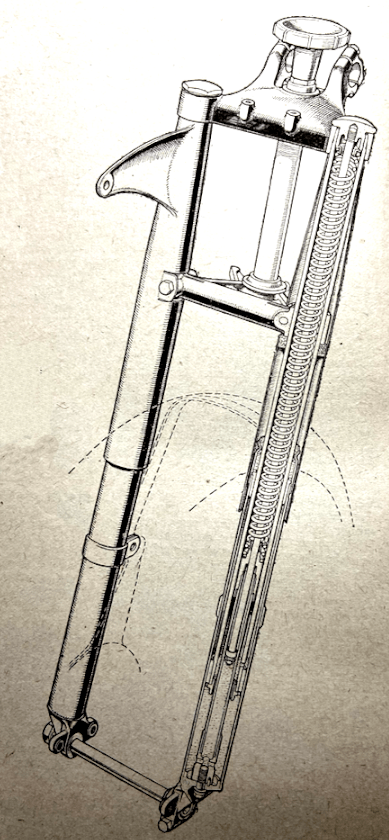

“AS A VERY KEEN enthusiast in civilian life you can imagine my feelings when I was put in charge of the Inspections Repair of most of my Company’s motor cycles. What more could an enthusiast want but to be steeped in motor cycles every day? We have every one of the Army models on our strength so have plenty of opportunity of studying the good and bad points of each make. One thing stands out a mile—electrics certainly need redesigning. The number of batteries, dynamos and voltage regulators required to keep machines on the road is terrific. To find a machine which charges is an exception. With girder type forks, spindles and bushes constantly require renewing. The advent of the Teledraulic fork is a boon in this respect. It is peculiar how each make has its faults which crop up in every model, and one wonders how much Mr Manufacturer tests his models not to have corrected them before thousands are made. A lot can, of course, be put down to the terrible condition of the roads over here. Oh! Why has not that lovely Triumph Twin got shaft drive? What a bike if it had! And what a boon the Enfield neutral-finding device is. I am sure in a few years British motor cycles will he at the top for design and performance—a position they held for so long.

NJ Payne, Bromsgrove.”

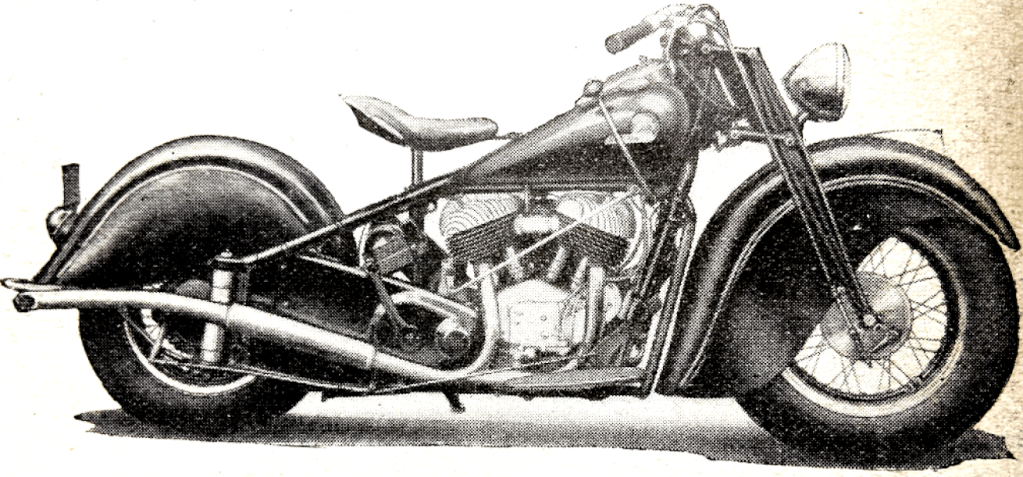

“I WAS VERY INTERESTED in Brigadier TCW Bowen ‘s article, ‘Riding Position for Solo Work’ in which he mentions danger and discomfort. There will always be these factors while riders are forced ,to adopt the ‘monkey-up-the-stick’ position, and consequently get cramped and stiff and dither about feeling for the brake in an emergency. Out of a total of 20 machines, there were two only on which I could sit and ride comfortably and be sure of stamping rapidly on the brake. They were an Indian Scout and a Ner-a-Car. Both these machines had footboards well forward and ample leg-room unimpeded by kick-starters, gear boxes, battery cases and oil tanks. Most of the weight was taken on the saddles, which left the legs and feet free to move about and ready for an emergency. Incidentally, the saddle of the Indian Scout was mounted on a spring seat pillar and could be adjusted backwards and forwards and vertically. With the exception of speed, the modern machine is basically the same as the machine of 1912. Its high saddle tank makes it more top heavy, and its weather protection is still nil. How can it be reasonably safe? What impressed me during the war was the ease of handling and controllability of the American twins used by the Americans and Canadians. In spite of their immense weight and power they were as easy to handle in traffic as the smallest lightweight. Makers here might do well to study the American layout regarding comfort, handling, and weather protection.

Comfort, London, N4.”

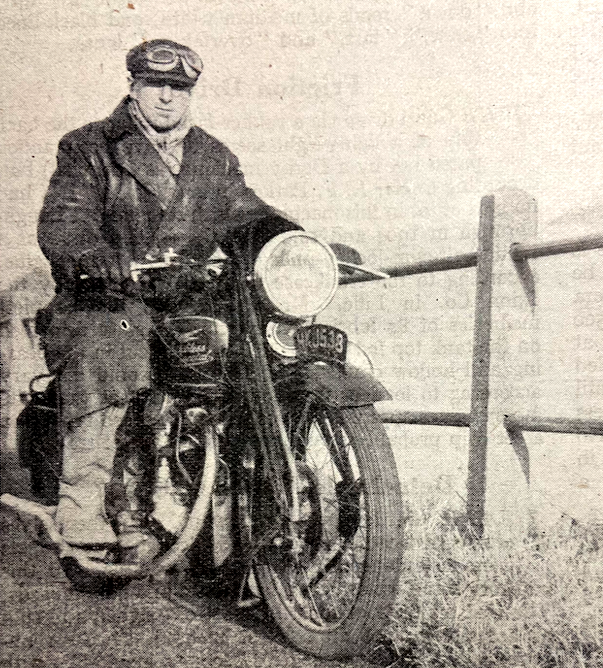

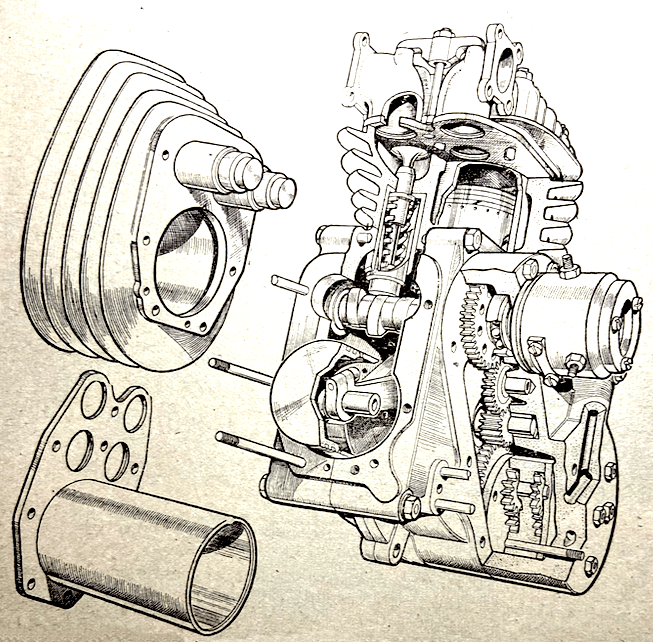

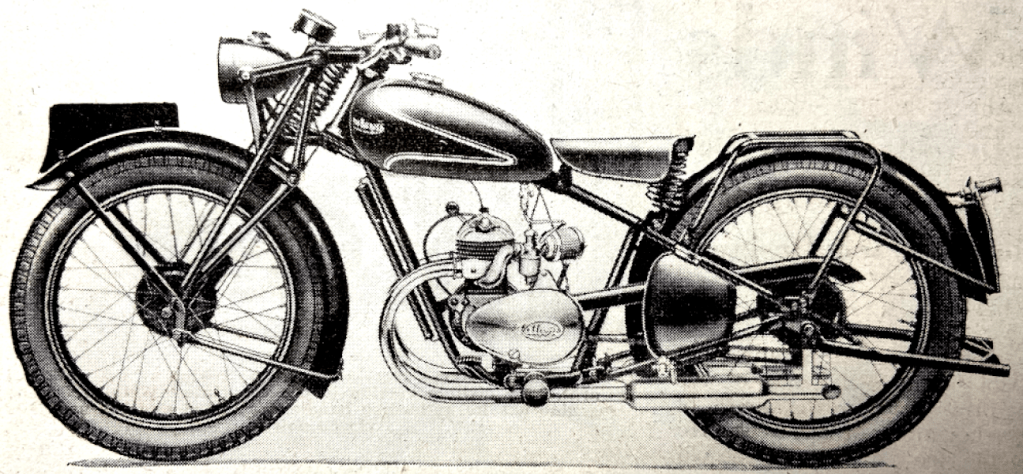

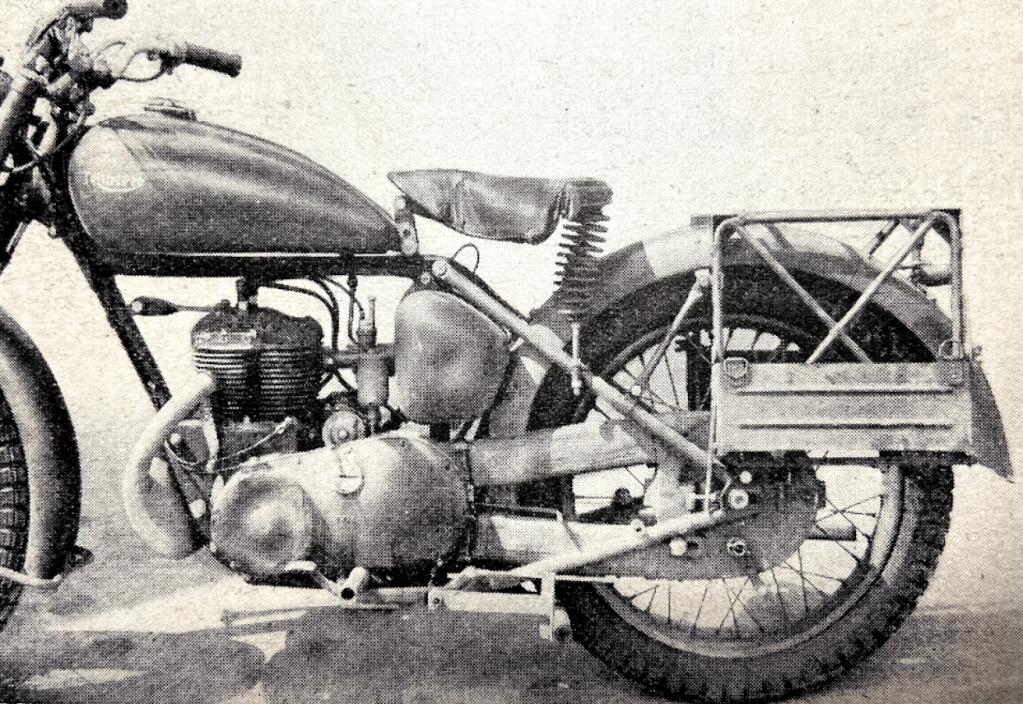

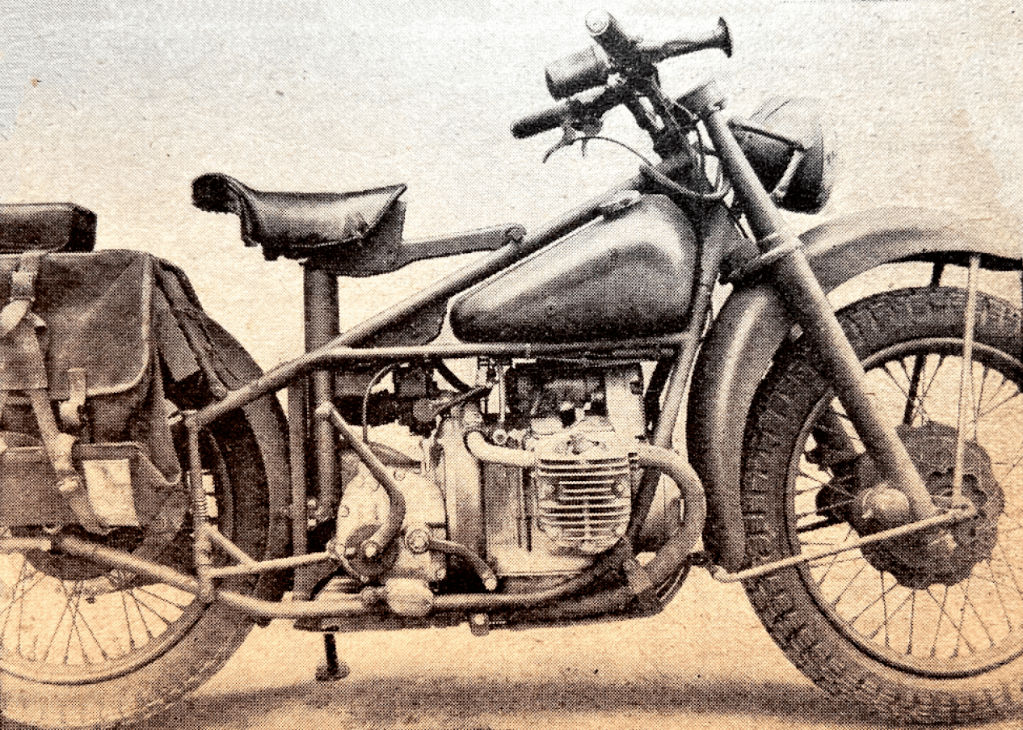

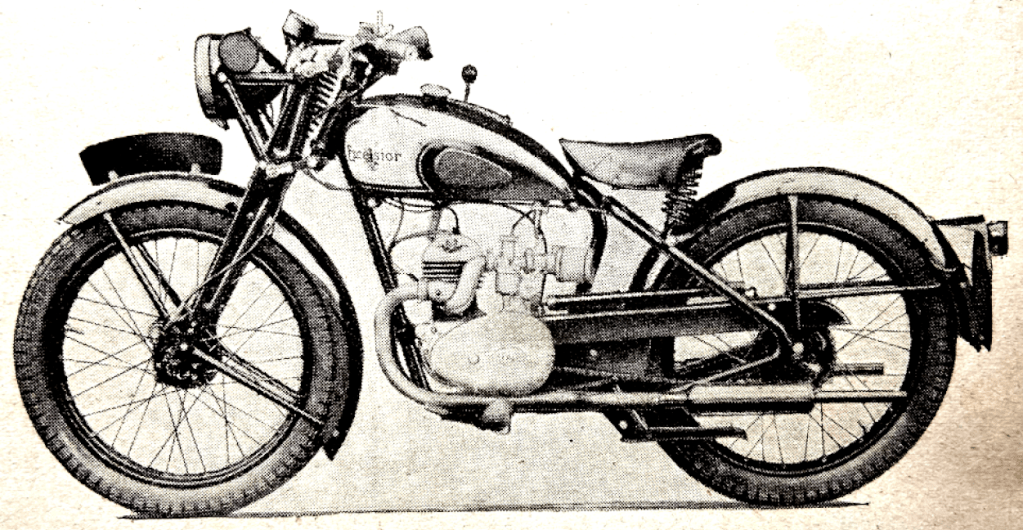

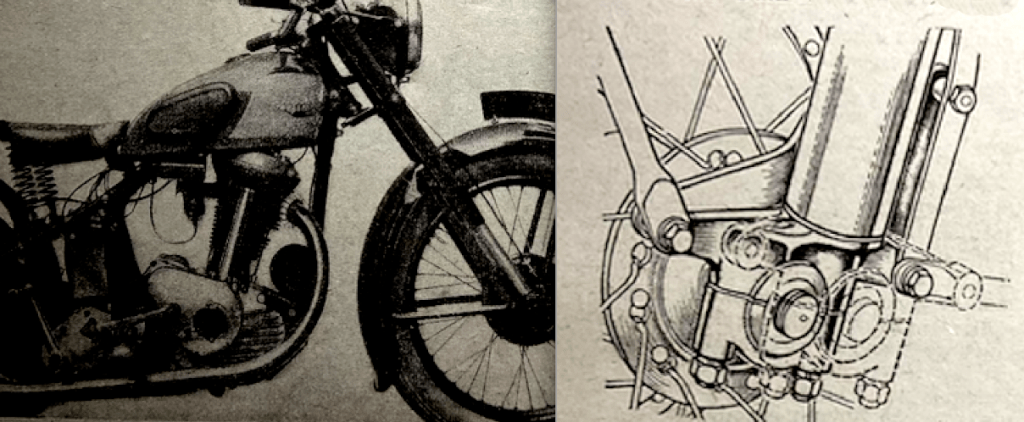

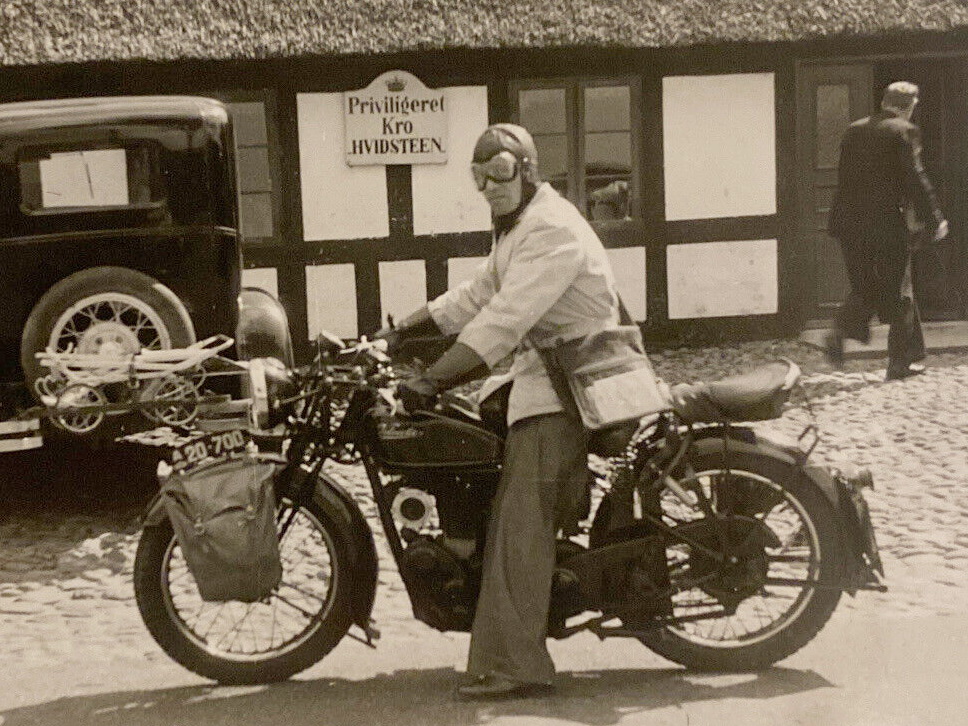

“HE WOULD BE a poor motor cyclist who could not reflect with pleasure on a year that had included rides on a blown Scott, a special narrow-angle V4, a trio of new vertical twins, a ‘Civvy Street’ Guzzi, a Benelli, various Flying Fleas, sundry experimental models which should make their bow in production form at the next Show, a sidecar-wheel-drive Zündapp, and a score and more other motor cycles. In number and variety of machines I must class 1945 as a thoroughly good year, and—lucky me!—the mileage has been very nearly that of a true peacetime year. What shall I touch upon first? Those captured from the Hun and Itie machines I have discussed in a whole series of articles, so little need be said here. I do not rate any of them very highly. Nothing is perfect in this imperfect world (says he ponderously), and while the foreigner, in a few of his models, can show us a thing or two, he can ‘blob’ at least as much as we can, and generally does so in a greater number of directions. The Benelli, a 250cc overhead-camshaft single, I give many marks to on the score of its engine. It proved a superbly balanced single, and, while it delighted in revving, it was also endowed with beefy pulling power. It reminded me very much of the original Model A Levis engine, a 350 single-port job that was as sweet and as lively as any power unit marketed. The steering

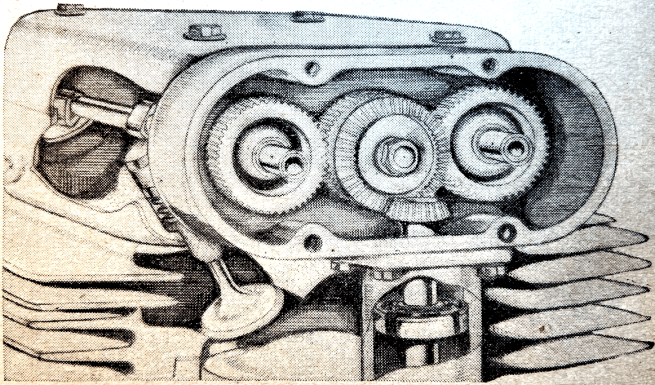

department was not too good, which is a failing of all the Italian machines I know. Of the BMWs two things may be said. The first is the patent fact that they have been designed as a whole instead of being a collection of bits and pieces. No 2 eulogy is that they do not leak oil—except that, in so far as those captured machines are concerned, oil had got into the rear brake from the bevel box and put paid to the brake linings. I have never had this trouble on civvy models, so it may have been a case of the German Army’s maintenance. My hope is that before many years are out we shall have a number of sleek, built-as-a-whole jobs, but one realises that there are snags. I am not referring to the fact that one may not be able to get at one’s clutch and at various other internals of a unit that is designed as a unit. Given the right design, the best possible material and high manufacturing skill, parts can be tucked away without it mattering. The snags, as I see them, are that once one has embarked upon the design one is hampered as regards making any serious changes. Secondly, such designs are expensive from the manufacturing aspect. The number of BMWs sold to Germans in pre-war days—sold to private owners—was small, in the same way that the number of Brough Superiors sold here pre-war was small. The reason was not that motor cyclists in this country did not yearn for Bruf-sups nor that Germans did not want BMWs, but that few could afford them. However, already I have ridden two built-as-a-whole British designs that incorporate just about everything the idealists have sought in the way of features, so we shall see. I am sorry if I am tantalising in this remark, but you will realise that discussing experimental machines is taboo. A reason why a motor cycle journalist is given prototypes to ride and comment upon, and thus has the opportunity of suggesting directions in which alterations seem to him desirable, is that those responsible for the model are sure he won’t go around talking. I love being asked along to try something new when it is in its initial stages, for then one can proffer criticisms and suggestions before things have gone too far. So often in the past, with the Show in the offing, it has been a case of ‘Sorry, but we can do nothing about it now; we shall have to see what can be done for the following year.’ Incidentally, it is not generally realised what a long-term process true development work is. With one factory I have an appointment every three

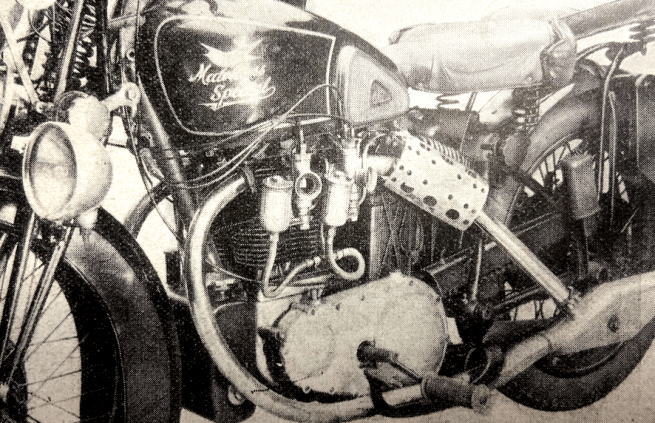

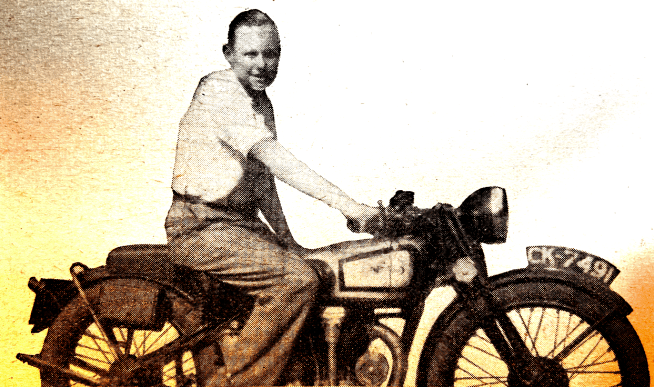

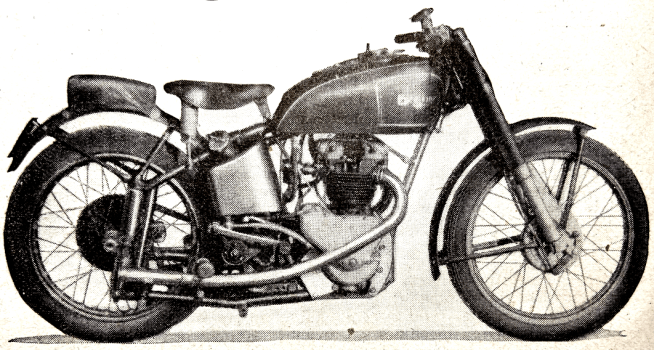

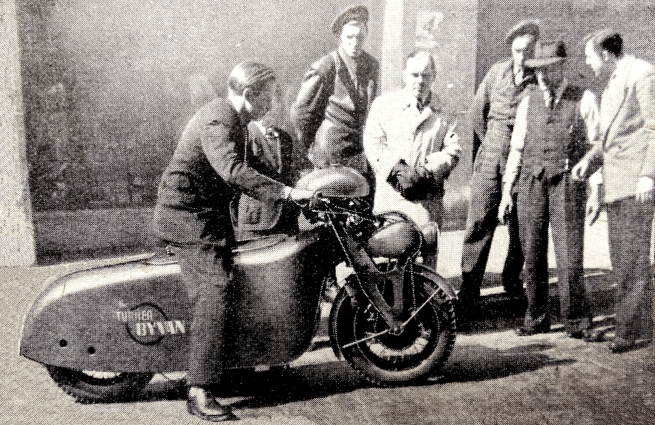

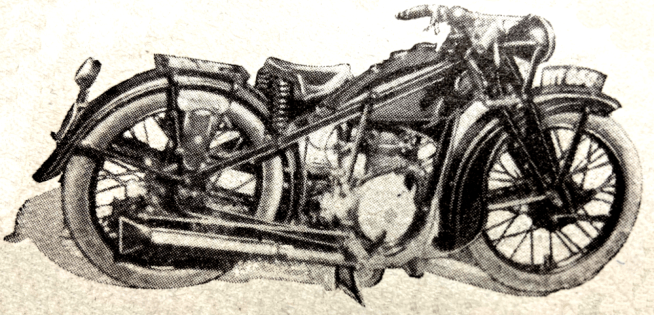

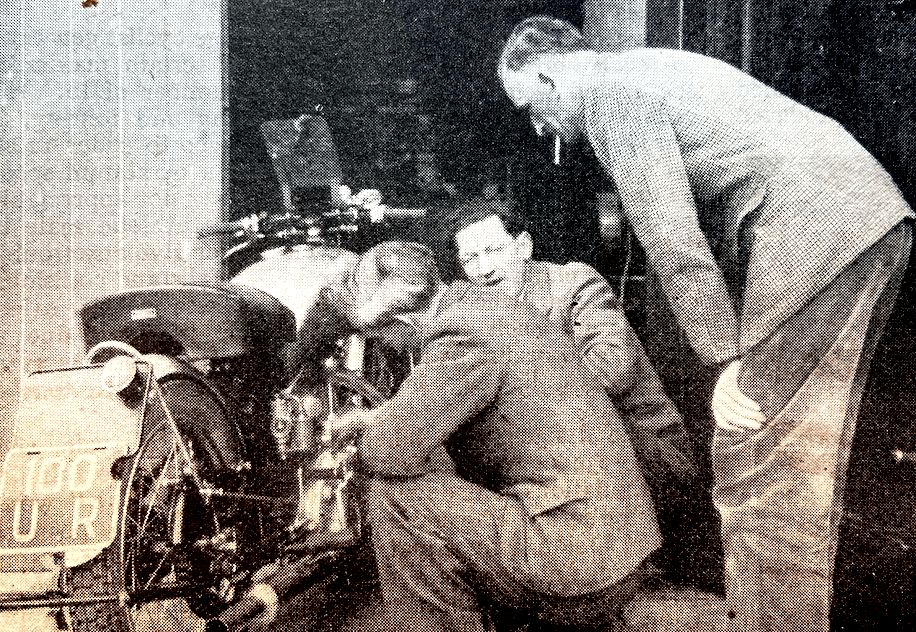

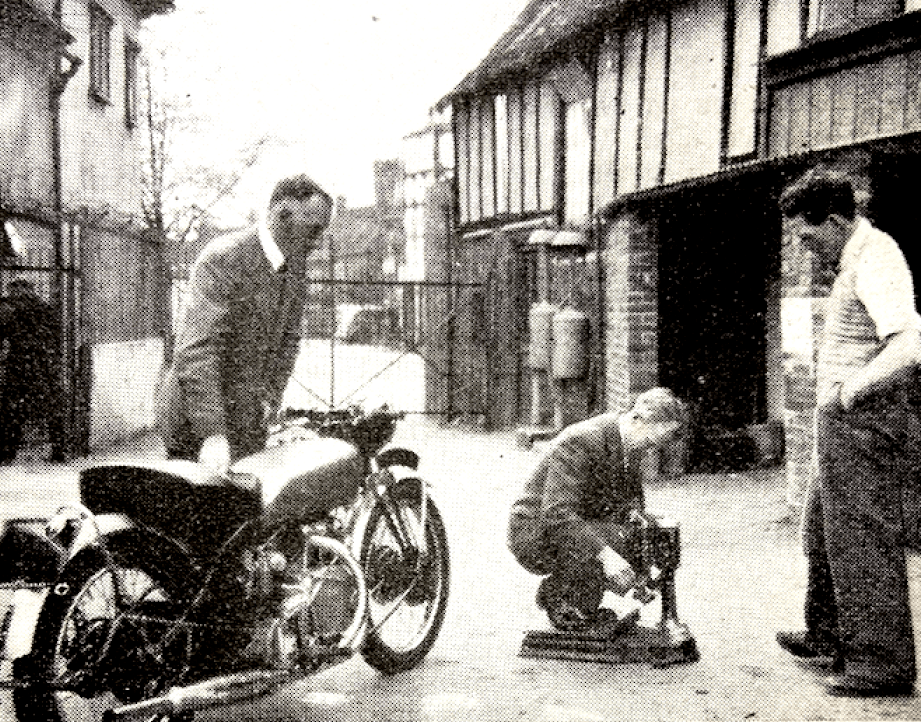

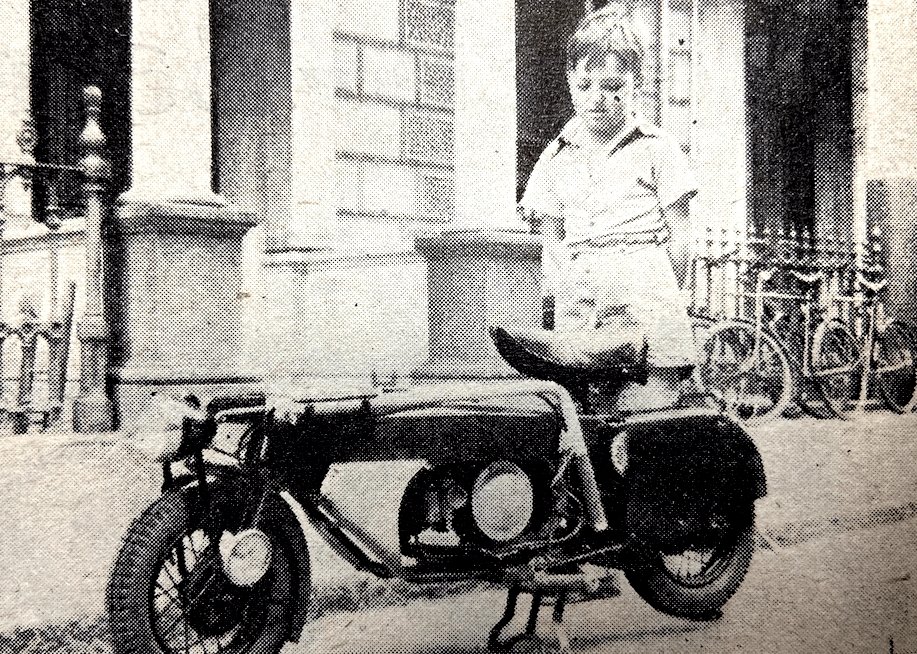

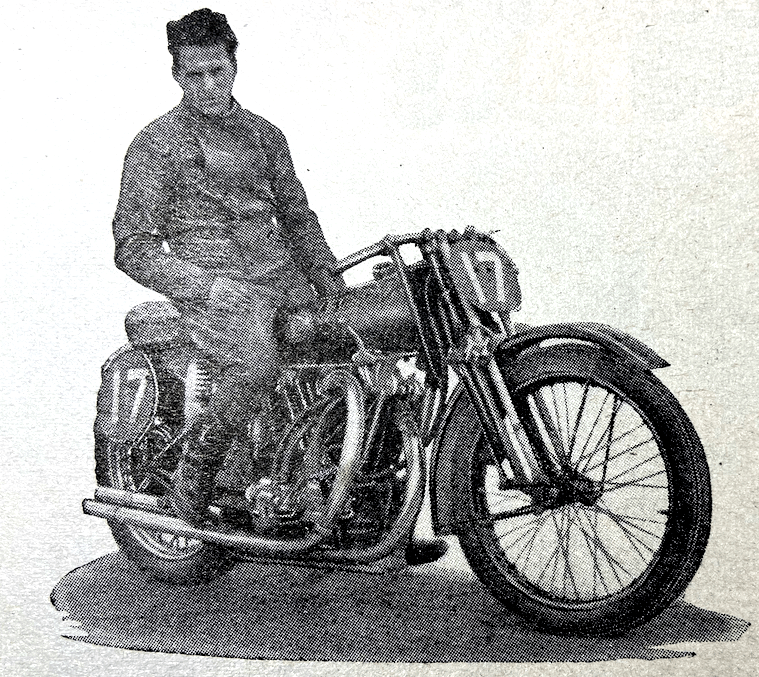

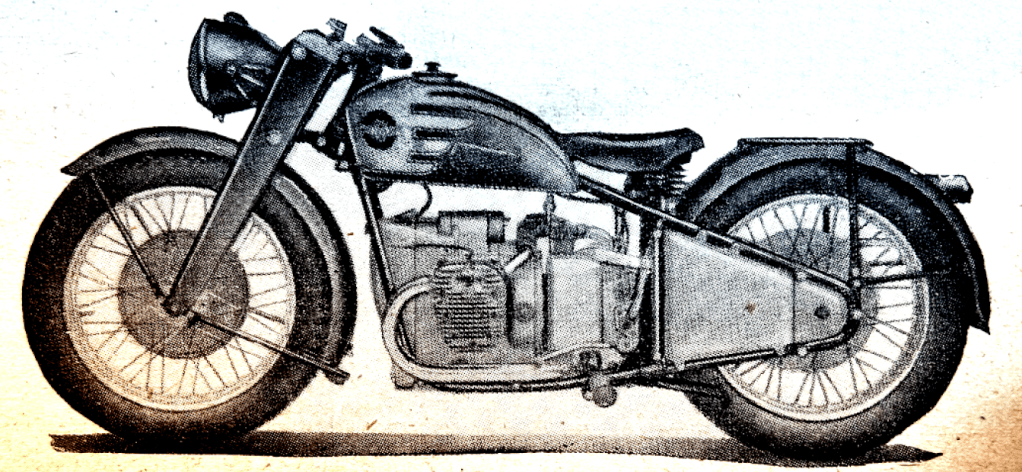

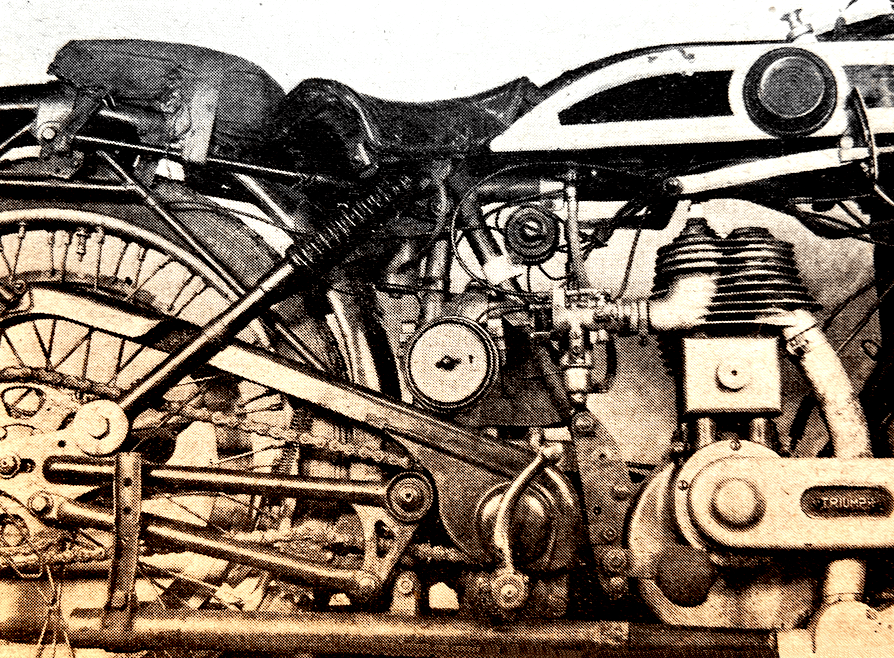

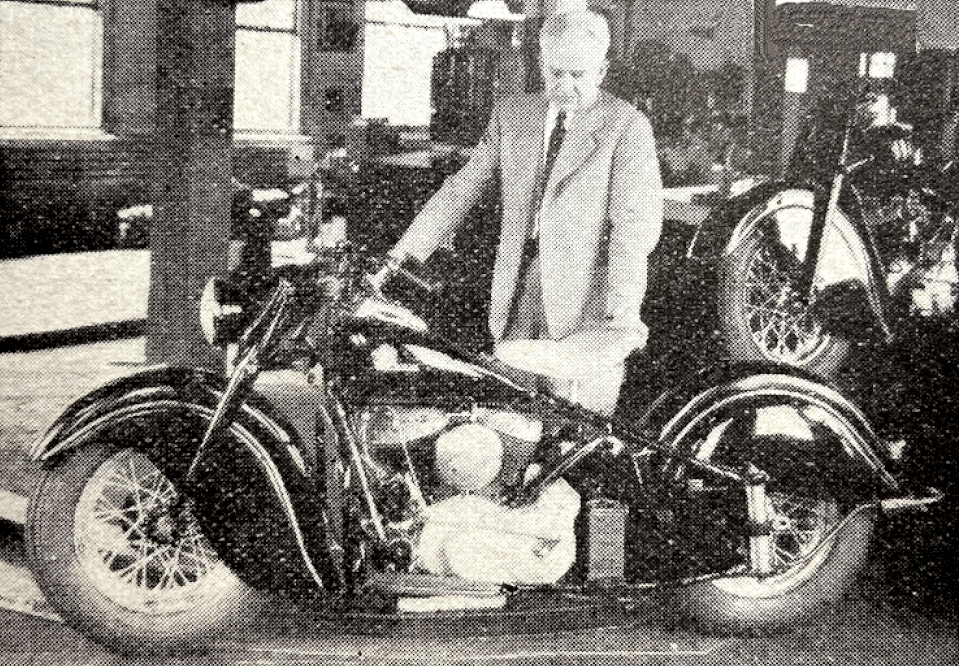

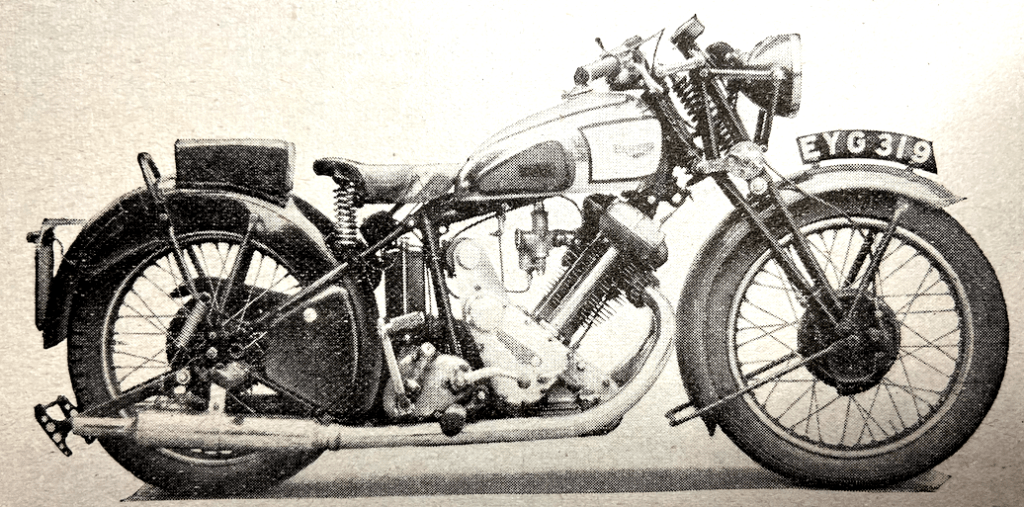

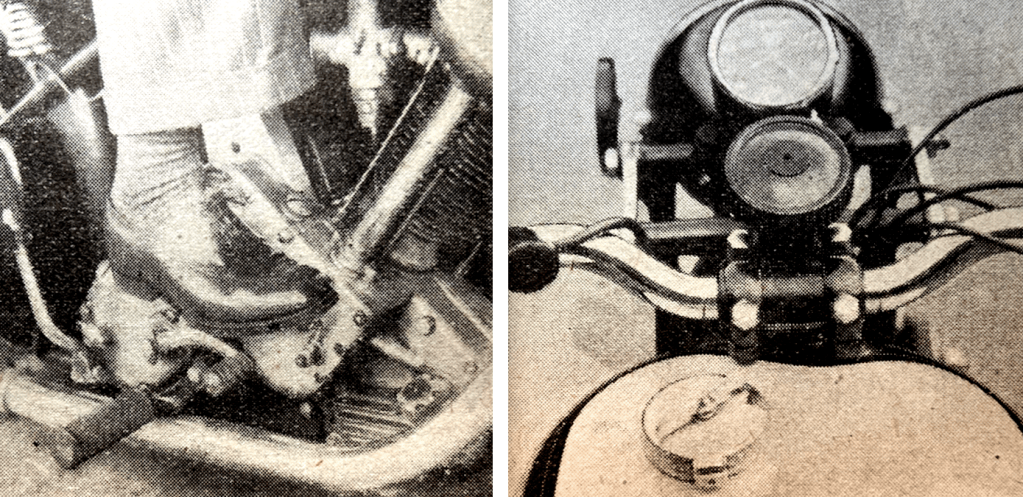

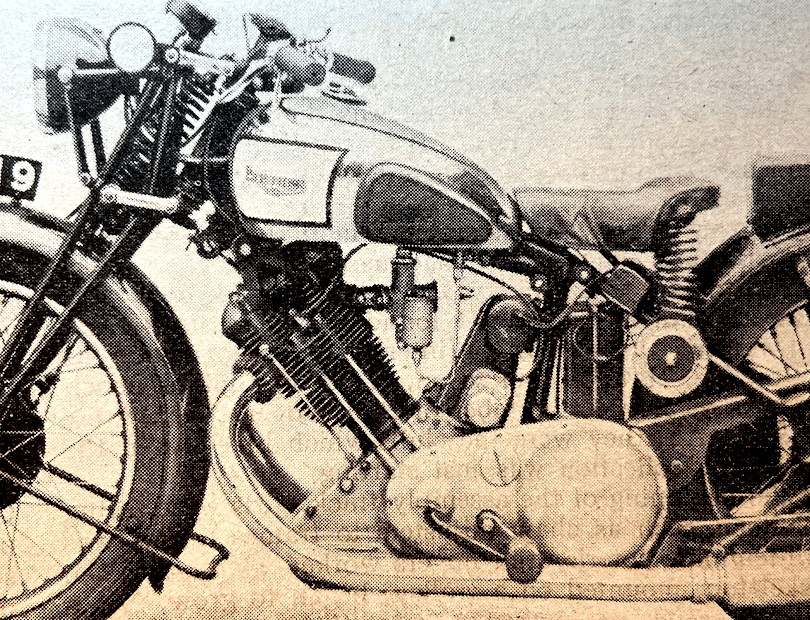

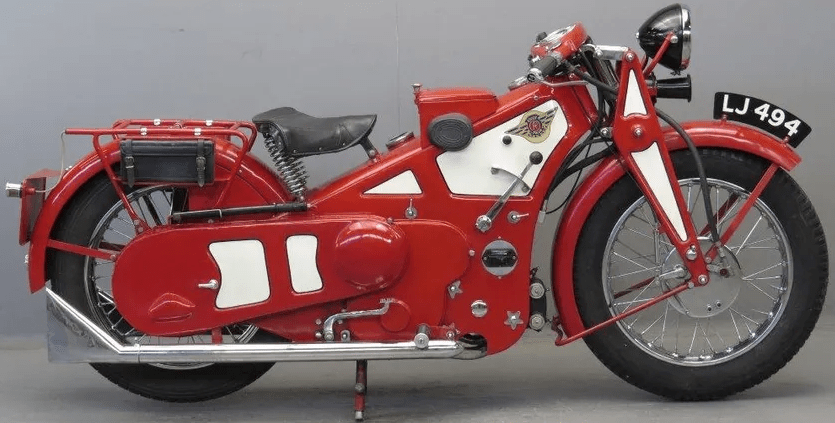

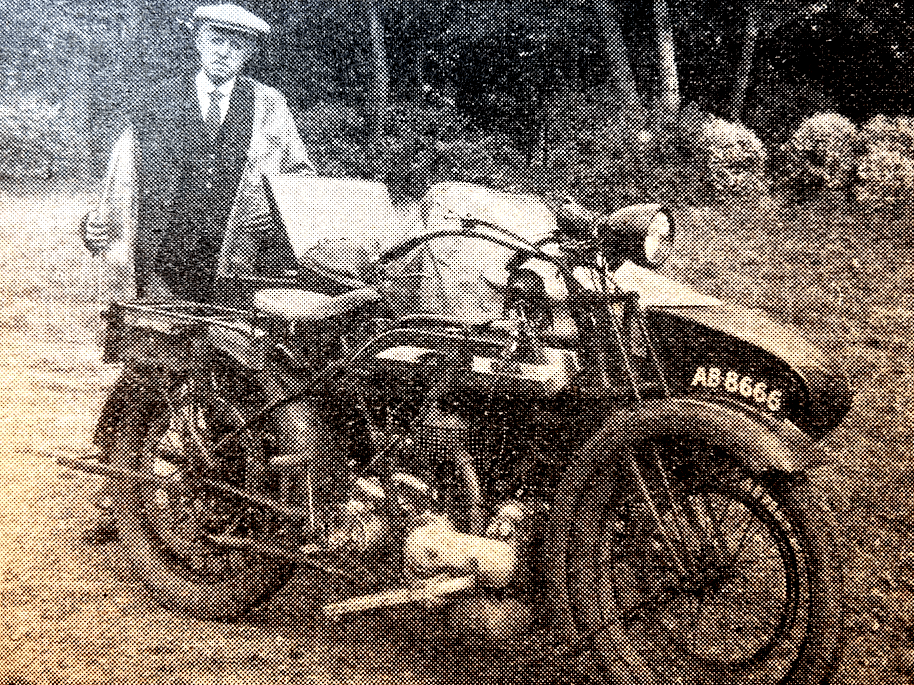

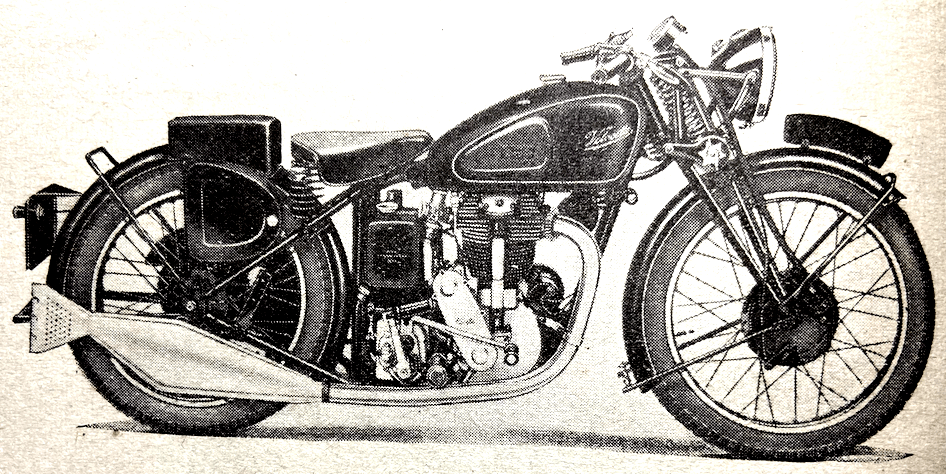

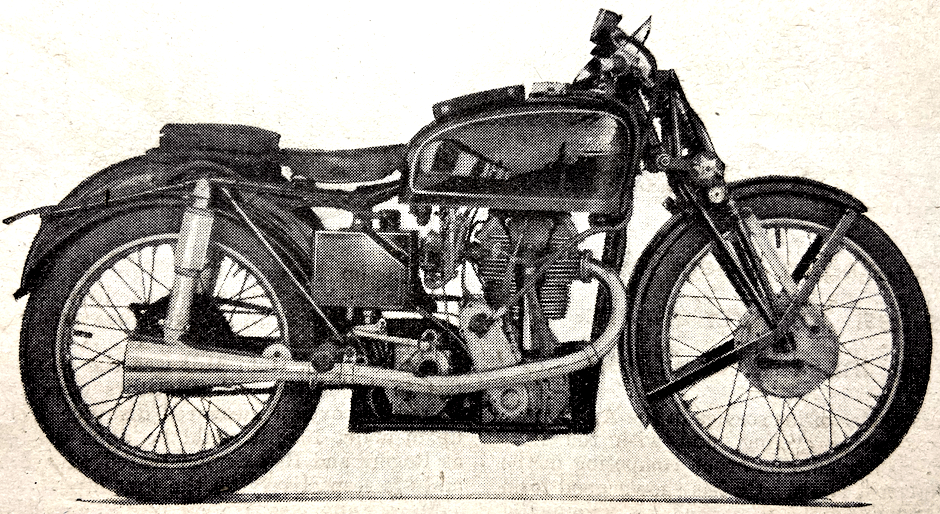

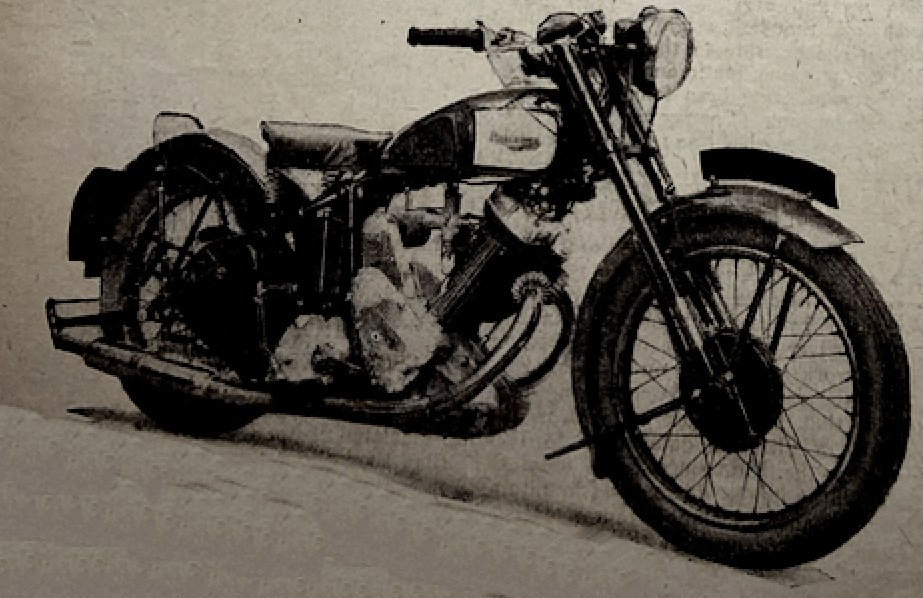

months to try out the new multi and see how far they have got. Each time, so far, there has been a marked improvement in the machine. When will it be ready for the motor cycle public? On the last occasion that I raised the matter, the answer was that it might be announced in some twelve months’ time. Thus I am likely to pay several more visits! The narrow-angle V4 I mentioned at the outset is a machine which, I understand, was once the property of Mr R0 Mitchell, who took it over to Merano, in Italy, for the 1932 International Six Days. Unless my memory is at fault, Mr Mitchell had the late Count Zborowski’s mechanic. Do you remember that famous car with a Zeppelin’s engine, ‘Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang’? Anyhow, Mr Mitchell was a great enthusiast with a fleet of super cars and this Four, a 593cc overhead-camshaft Silver Hawk Matchless that was much modified and generally hotted up. One of his favourite hobbies, I recall, was to slip down to Yeovil from London and back again just for the joy of a fast ride. And even on a standard Silver Hawk one could tuck many miles into the hour. My first experience on one was a trip exploring the Land’s End Trial course and tackling West Country hills that lasted the Saturday afternoon and the Sunday and involved 630 miles. So enthralled was I with the machine on this occasion that I bought a Silver Hawk—indeed, had one in 1932 and another in 1934. Although only of 593cc and gentlemanly withal, these machines gave me the highest averages of my life. They are the only machines on which I have found more than sixty miles went past in sixty minutes. Averages of over 50mph were almost commonplace, and I have often wondered why automatically one put so many miles in an hour. More than once I have urged Matchlesses to get hold of a really good Hawk and put it through its paces to-day. I would love to be taking delivery of a brand-new Silver Hawk to-morrow—would love to have a good second-hand one if only there were spares available. However, I have done the next best thing and had a ride on this two-carburettor, four exhaust pipes, special. You see the machine in a couple of the photographs. Mr. Babson, a metallurgist and very knowledgeable engineer, bought the machine in bits and spent a lot of time and money building it to his own ideas. I will not run through all the changes he made. They include the fitting of Webb front forks, a Burman four-speed gear box, new brakes—he shrunk stiffening-cum-cooling fins on the rear-brake drum—a modified lubrication system, and so on. Before he sold the machine he kindly brought it along to Dorset House for it to be examined. In addition, I rode it round the houses. He followed up by suggesting I had it for a week-end. We compromised by my dropping down to his home in Kent on Boxing Day and taking the machine out for a run. I found the two-carburettor engine had a snarl and a degree of snap about it that was thrilling. There is a very great deal to be said in favour of the narrow-angle V4. It is a compact engine and nicely balanced. There may not be the smooth

purr of, say, the straight four, but the exhaust is pleasant. In this case it was decidedly noisy—very super-sports-car—but what joy taking the machine up the scale in the gears! Maybe I have been spoiled somewhat by the steering of the very latest motor cycles, but there did not seem to me to be the light, yet thoroughly safe, feeling I had with standard Hawks, and the rear springing, instead of absorbing every road irregularity, large or small, gave a somewhat hard ride. On this latter point Mr Rabson mentioned that the pillion-seat arrangement was introducing a certain amount of solid friction—was imposing some pre-loading of the friction dampers. Also, there was a 3.25in-section rear tyre in place of the standard 4.00in. By the way I have remarked on the light, safe-feeling steering of the standard Hawks, that was true until the front-fork spring started to close up, whereupon the trail became on the small side and the steering might be rather too light. Whether it was the after-effects of Christmas or merely the fact that people were out for a pleasure run, I do not know, but those who were using the roads were not so punctilious in their road behaviour as to encourage one to go fast. Further, the brakes seemed a little on the spongy side. The standard Hawk brakes were on these lines. All I did, therefore, was to use around 60, employ the gears and once flick up to around 70. The run was sufficient to make me long to be taking delivery of a new Hawk. Of course, the most out-of-the-ordinary mount I lave ridden over the past twelve months is Mr Graham Kirk’s Scott, with its Colette blower and mighty SU carburettor. The final job is so simple-looking

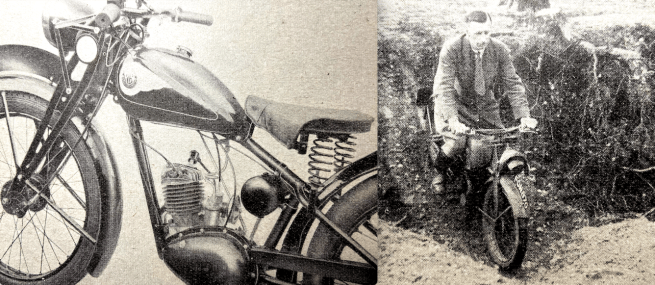

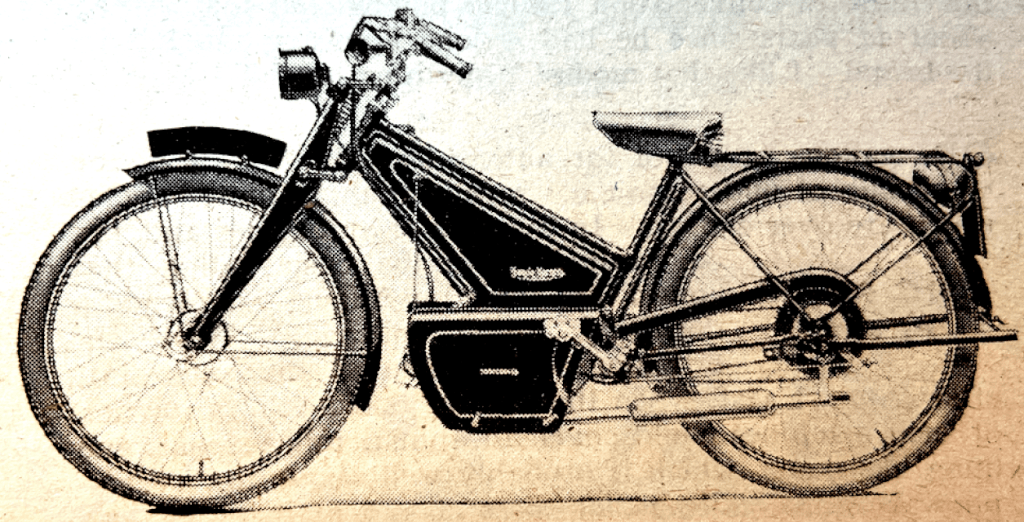

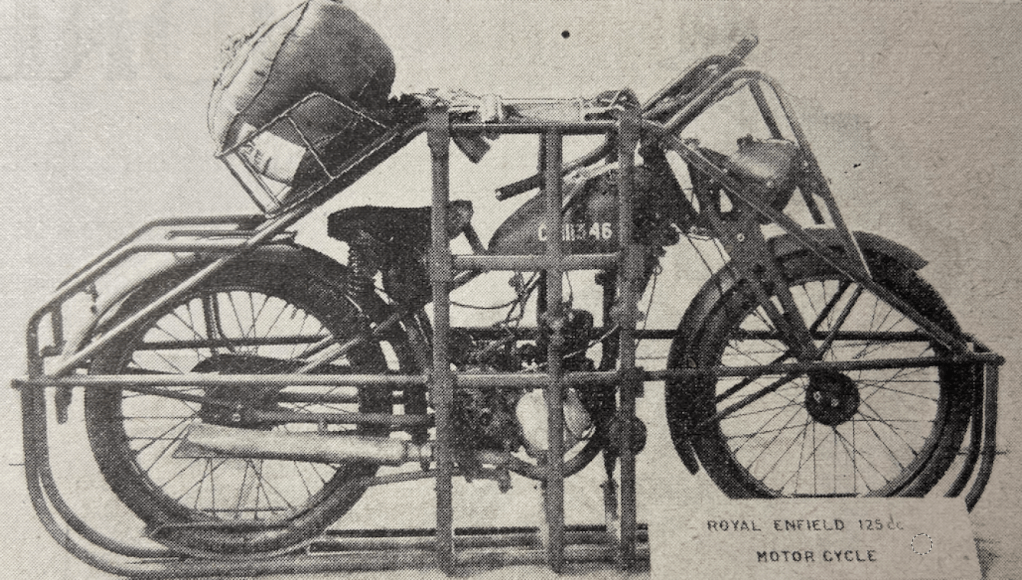

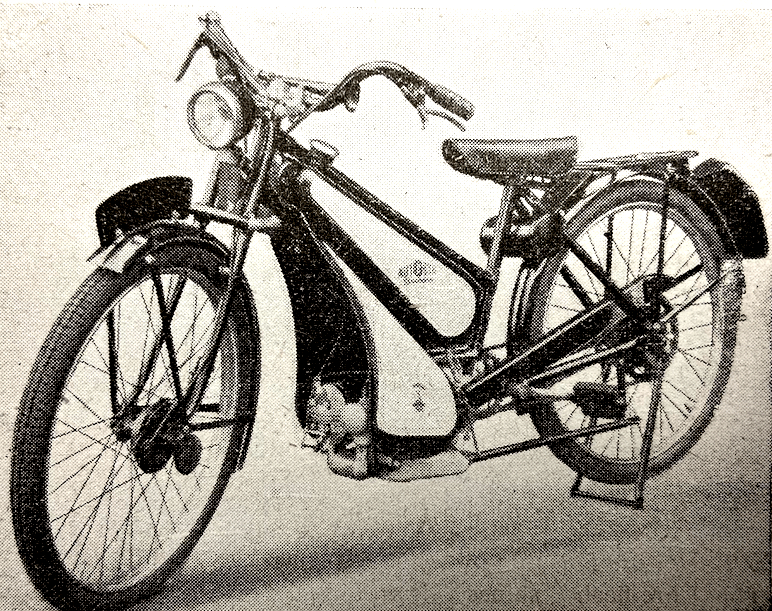

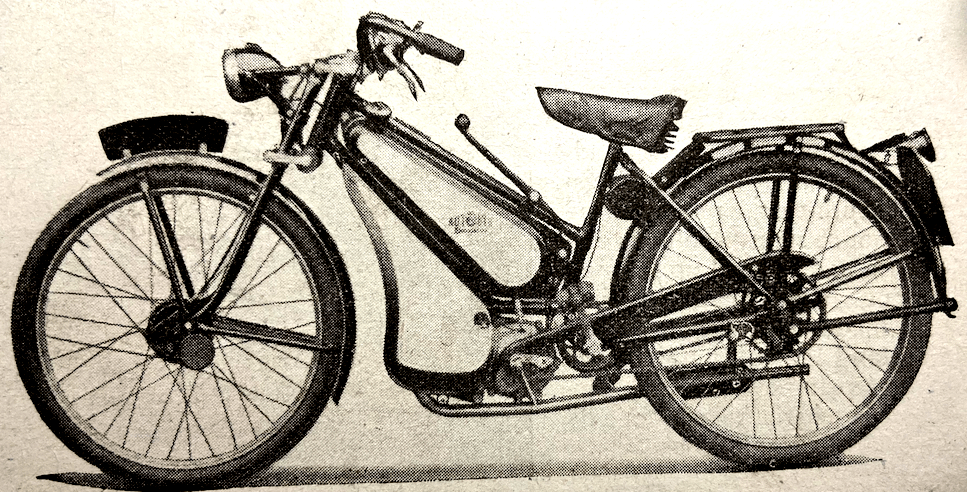

in its conception that one marvels at it the more. Here is a rorty machine if ever there was one. ‘A thrilling, breath-taking beastie,’ I dubbed it. What Mr Kirk has done, you may recall, is to fit a blower of the positive-displacement type with a capacity of 560cc to his Stott which, at the time of my visit, had a 596cc engine. The kick-starterless machine, I found, started without difficulty; it two-strokes and does not four-stroke and is mild enough to be taken through traffic and winding lane without any difficulty. But open the throttle and the mild manners disappear with the increasing revs. The power builds up and builds up, and one has a sensation totally different from any I have had previously or since. And Mr Kirk told me that, with all this, he had had reliability. On trying the machine I wondered why more folk had not worked on similar lines; then I thought of the years Mr Kirk has been busy with two-strokes and the time spent before he developed this apparently simple layout. Shall we go from one extreme to the other? Over the year I have covered some thousands of miles on lightweight two-strokes. Often I have had my 1,000cc Ariel Four and a 125cc James or Royal Enfield out on the same day. I enjoy these Flying Fleas and have bought one as a runabout—as a sort of tender to the big machine. I shall not use it for long-distance work, but it will be useful for many a short journey and for rough stuff. Incidentally, I have a 40-tooth rear chainwheel which will give me a bottom gear of 25.7 to 1, which should be amusing in the rough, though with a top gear of as low as 8.9 to 1 I shall not want that ‘rough’ to be very far from home. Where these machines score is that one can take them out much as one would a bicycle. They are always ready, it seems, and cover over 100mpg even with the hardest driving. When the roads are treacherous there is nothing to equal these really light lightweights. As you know, they will average 30 and more miles an hour, and that means on runabout work that there are very few minutes’ difference between these machines and big ‘uns. They do not two-stroke so well as they might, and I consider that such machines, for runabout work, need built-in legshields that harmonise with the design. However, you will gather my feelings about them from the fact that I have invested in one of them—have done so after experience which now amounts to well over 6,000

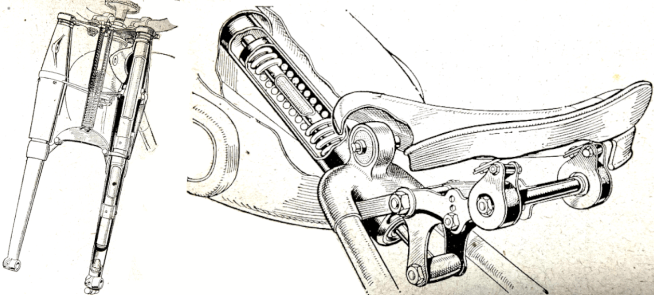

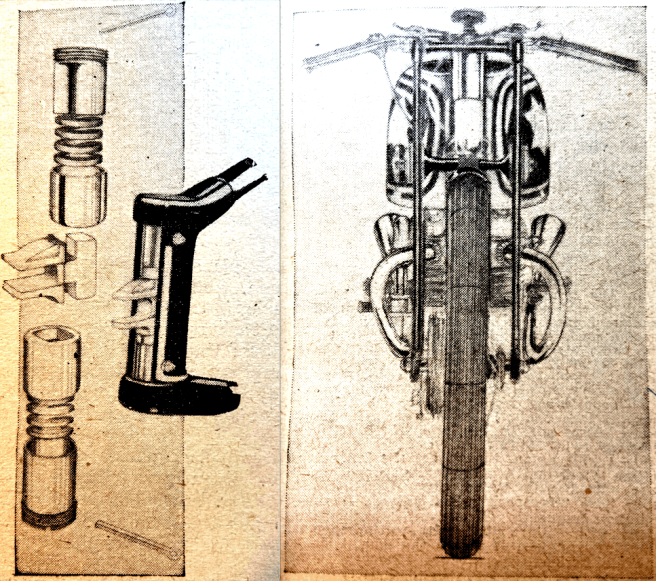

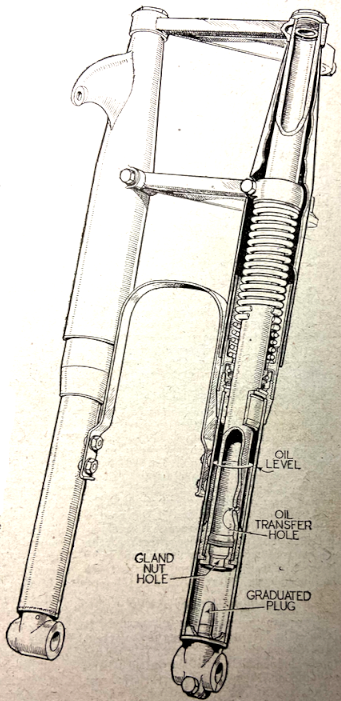

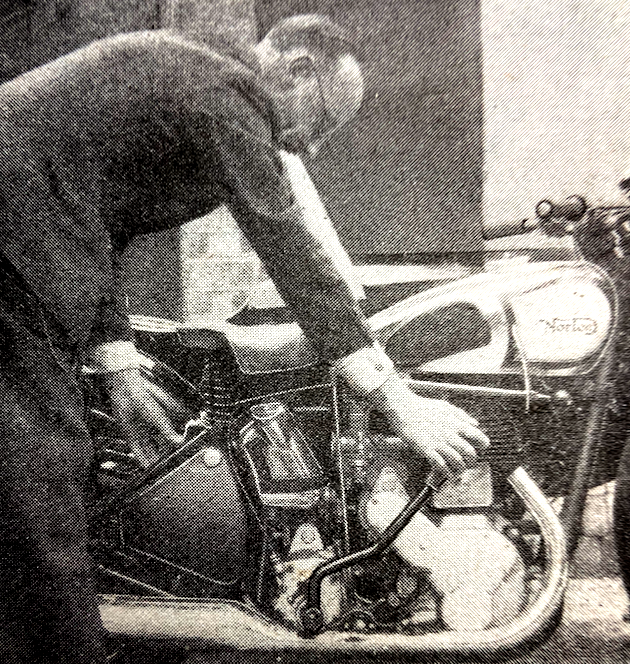

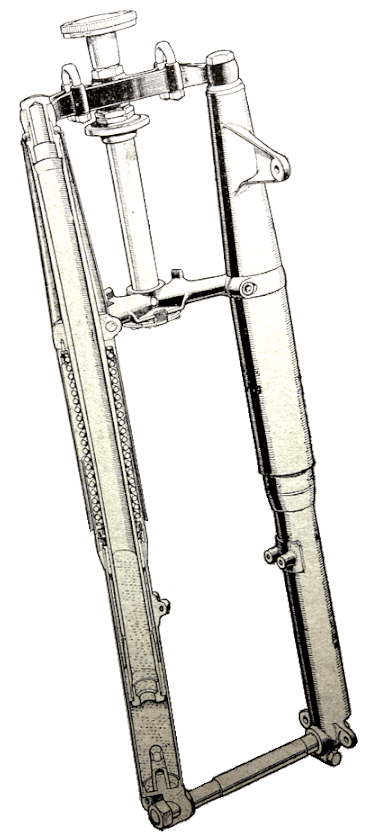

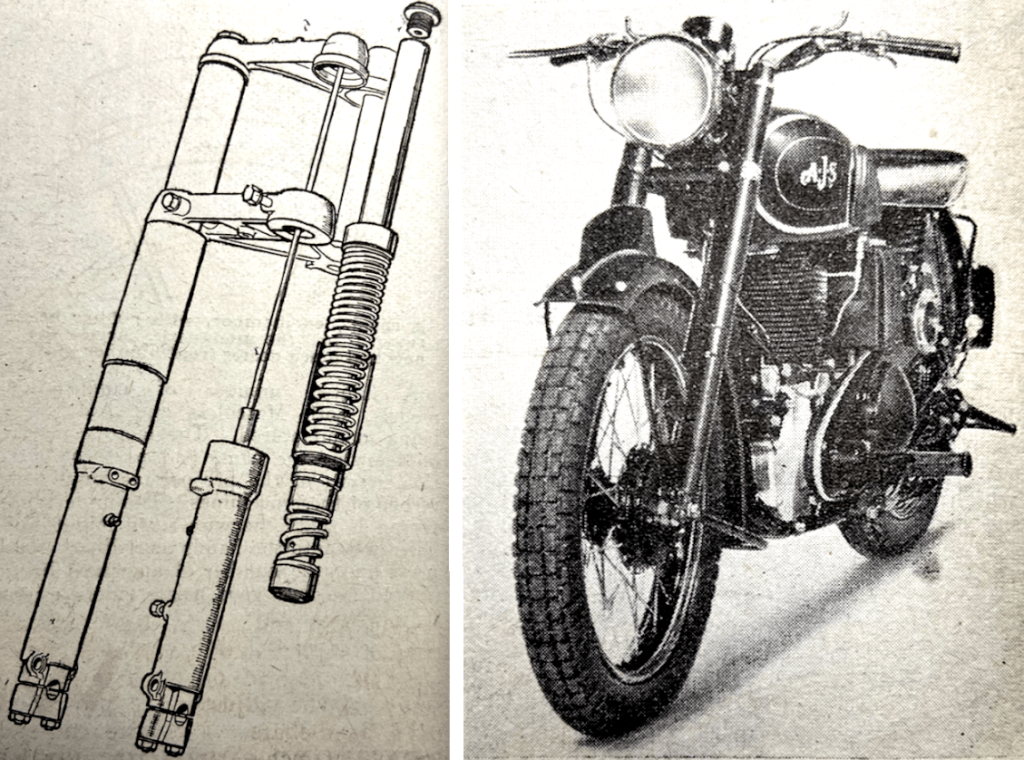

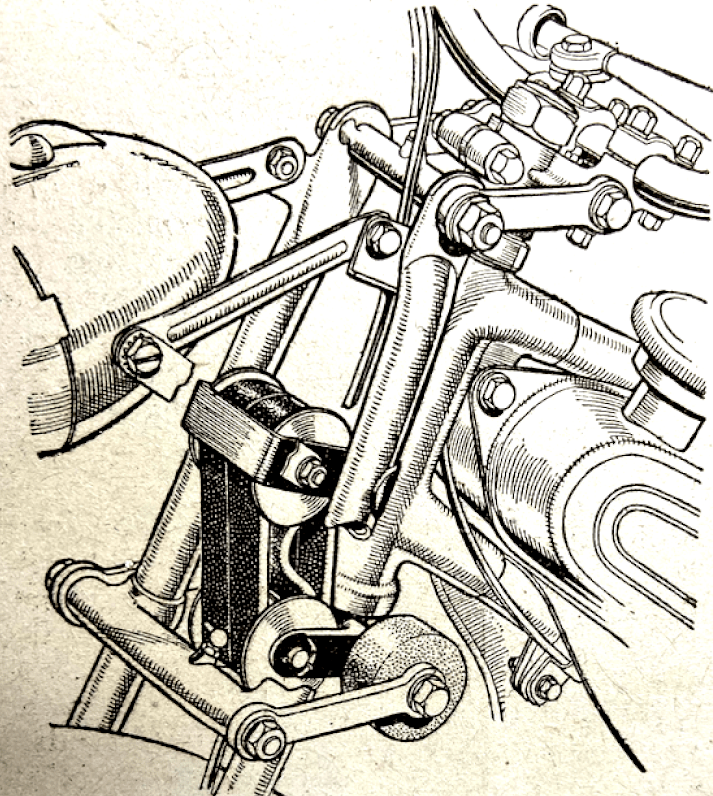

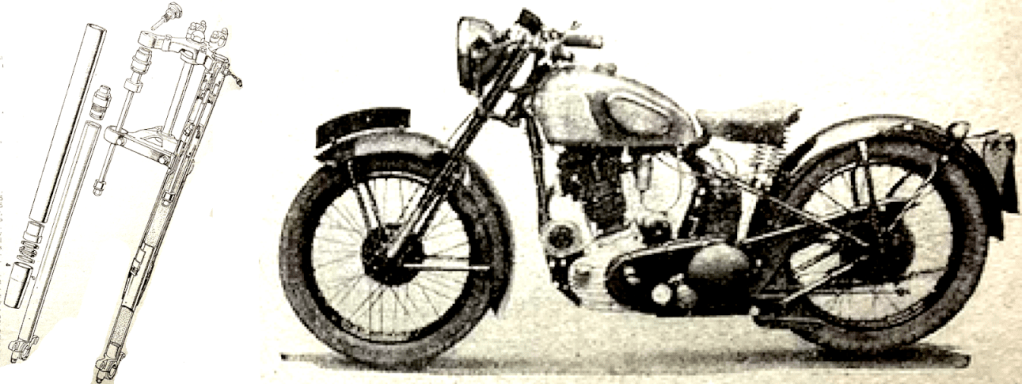

miles. By the way, I am keeping the Army riding position, ie, the saddle set high. That Civvy Street Guzzi was a recently imported 500cc overhead-valve horizontal single. There was the mighty outside flywheel that gives, I believe, something like thrice the flywheel effect of the average single. It results in outstanding pulling and flexibility. The engine characteristics are very much those of the old ‘Sloper’ BSA, but without the latter’s delightful silence—far from it! Both mechanically and as regards the exhaust the Guzzi was decidedly noisy. The steering was a trifle wavering. With the close-ratio gears the gear change was not too much of a crash type. What pleased me a lot was the rolling-type central stand. One merely placed some of one’s weight on the protruding ‘ear’ and automatically the machine was on the stand, rear wheel in the air. One day, if life becomes a little less hectic, I am going to make up some-thing similar for my own mount—for the Thousand. Whenever I get on this latter machine following experience with something else, I revel in it. The previous occasion on which I rode it I may have felt critical, but coming back to it I praise its smoothness, its exhilarating surge of power and the effortlessness of its behaviour. Recently the Naval captain who bought my 1937 Square Four from the man to whom I sold it was in touch reminding me that I had promised to sell him the present one when the time came. I had to tell him that I had no idea when that time would be for there is nothing to wean me from it. It has now covered over 30,000 miles and soon, I suppose, I must decide whether to have the cylinders rebored or to fit ‘Simplex’ piston rings. The oil consumption is not wildly heavy—about 800mpg, at a guess—but the off-side rear cylinder has a fair amount of wear at the top of the travel of the upper-most piston ring and one day that ring may, of course, break up. So many enthusiasts of late have written to me about the Matchless ‘Teledraulic’ front forks fitted to my machine that I had better relate their history. These forks are one of the two pairs of special heavyweight ‘Teledraulics’ which Associated Motor Cycles made in 1941. They are not the forks fitted to the WD Matchless, nor those of the recently announced civilian Matchless and AJS models. One of the two pairs Associated Motor Cycles used themselves for test purposes and the other they fitted to my machine with the idea that I should have extended experience with ‘Teledraulics’. The mileage the

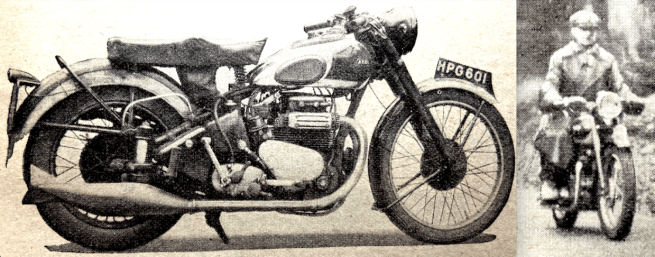

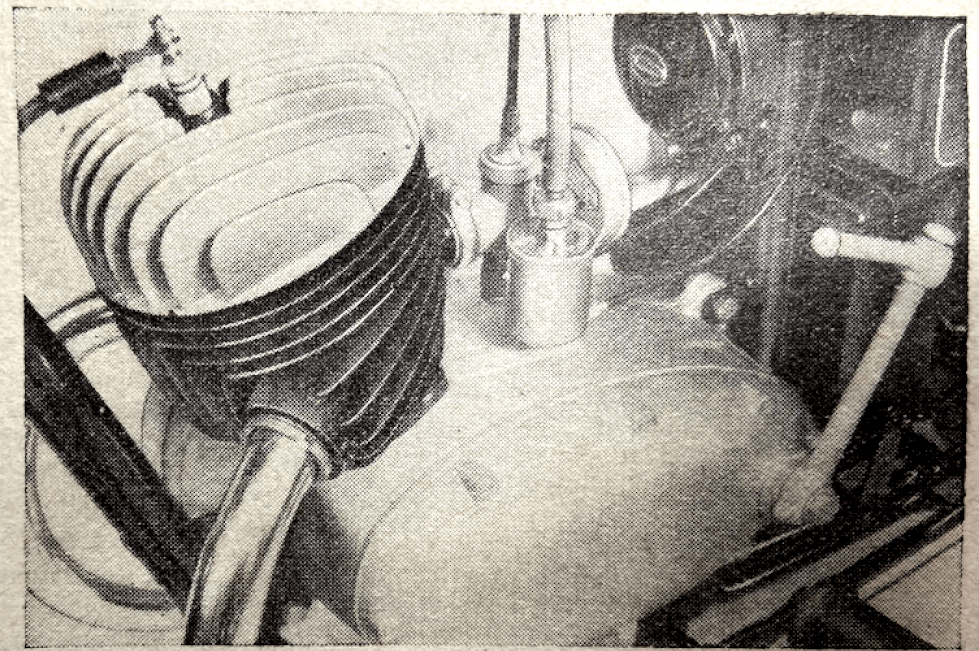

Thousand had covered when the forks were fitted was 10,350; the mileage now is 30,508. Thus the forks have been in use for just over 20,000 miles. During that period the forks have not been topped up with oil—there has been no leakage at all—nor have they been touched except for the fitting of a new light-alloy head clip. With these forks the steering has been something of a revelation. Contrary to a statement I read recently, I have found that the tyre wear with these telescopic forks is more even than with girder forks. With the long ‘soft’ movement the road-holding is super. My whole experience of telescopic forks is that they mark a big step forward, improving the steering, road-holding and safety in marked degree. How marked this is one finds when one tries out two machines that are similar except in regard to their forks. You may recall that I did this in the case of the 350cc Royal Enfield. The machine with the new Royal Enfield telescopics was almost incomparably superior. That it was an exceptionally nice 350 I had realised, but it was only when I swopped machines that I realised what a change the forks had wrought. Incidentally, the balance of the new Royal Enfield with its light-alloy con-rod is single-cylinder at its very best. A telescopic front fork with which I have had over 300 miles’ experience is the Ariel. These, I believe, will be available before very long. They were announced in connection with the 1945 Ariel programme. I have tried them in their final form; they, too, are the goods, so are the BSA ones….An interesting point

about the Triumph forks, which are delightfully soft in action and responsive, is the effect they have had on the rear end of the machine. One of the criticisms of the Triumph twins of the past was that their rear wheels were apt to hop. They now stay on the road to an almost spring frame-like degree. I tested the 350cc vertical-twin Triumph—the roadster type, the 3T, not the Tiger 85. It is a mount with magnificent traffic manners, yet really lively. After testing the machine I wrote to Mr. Turner, saying ‘I congratulate you.’ He has often said that one of his aims is to endeavour to give pleasure to youth; this machine, to judge from the one I had, is going to give immense pleasure and satisfaction to both the young and the not-so-young. My main hope is that Mr Manufacturer will provide a riding position that is as good as the remainder of the machine. From twins, let us pass to a single—to the latest 500cc overhead-valve AJS. When I took over the machine I was very much expecting an AMC 350 of the type I know so well, but with 150more cc and, consequently, rather more urge. I found that in the 500 there was a delightfully sweet engine, with a liveliness at medium revs I had never known in the 500cc models. The impression gained was that this was an engine built by some tuning wizard, every part fitted by a craftsman who proposed using the machine in competitions. The machine rustled along, eating up the miles in a most satisfying manner and even in the sixties darted ahead on the throttle being opened. A very nice motor cycle. That, since I must keep quiet regarding experimental models and experimental suspension systems, must, I suppose, be that. Altogether, from the machine angle, it was a most satisfying year. I wonder by how much 1946 will beat it.”

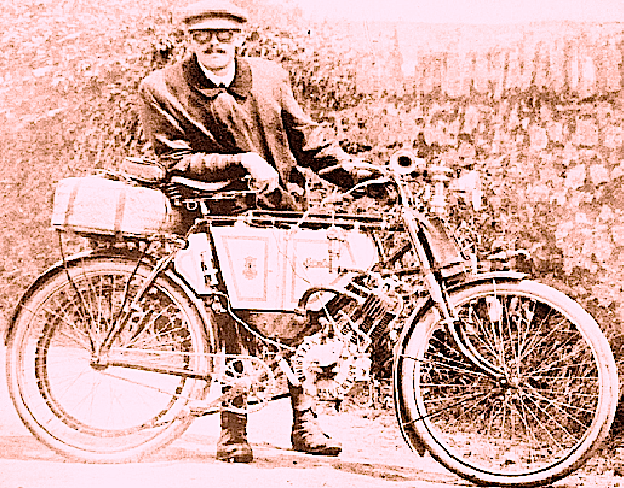

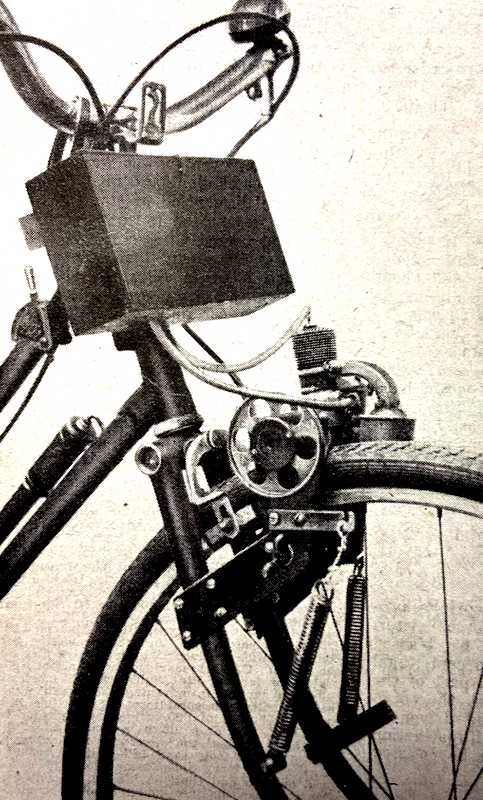

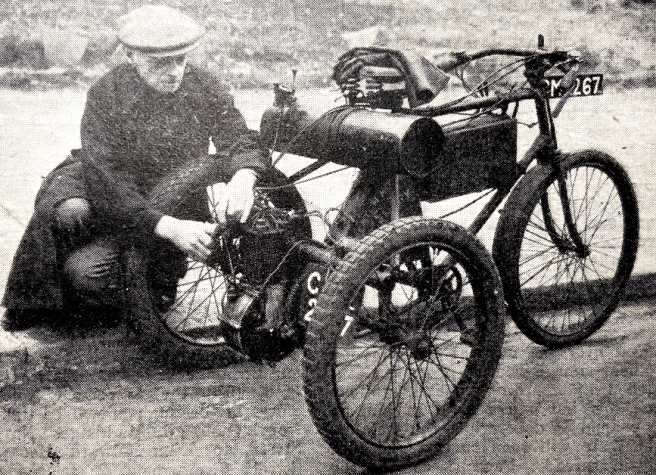

“THE GUZZI DRIVE via a rubber-faced roller to the back tyre of a lightweight seems to have been anticipated not by a Derby machine (as I fancied) but, according to Mr LF Parkes, by an ‘Ixion’! I had no part or lot in this machine, which was built at Loughborough in 1904 and sold with the friction drive or a round-belt-cum-jockey-pulley tensioner. The engine, according to the crankcase transfer, was made by the Ixion Co in Lille. Mr Parkes has the happiest memories of its lubrication system. A glass drip feed on the tank top fed the engine via a slot cut in the bearing and hollow crankshaft. This feed would not vary according to load or throttle opening, but at that date most engines approximated to the single-speed type, and a set drip probably served most conditions of travel.”—Ixion

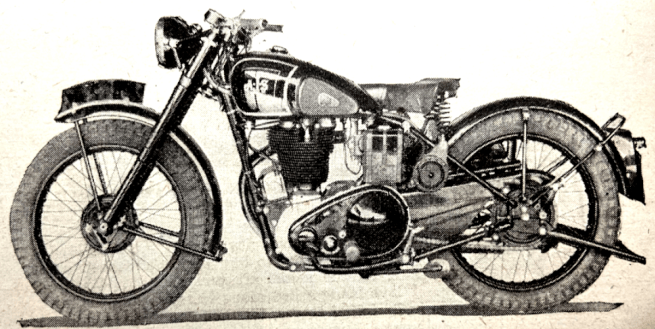

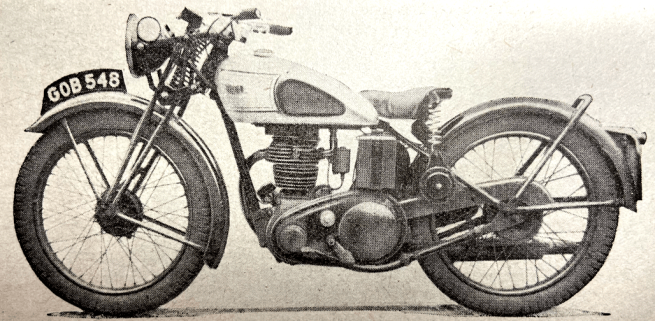

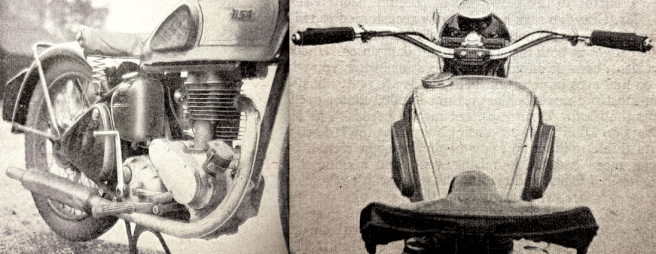

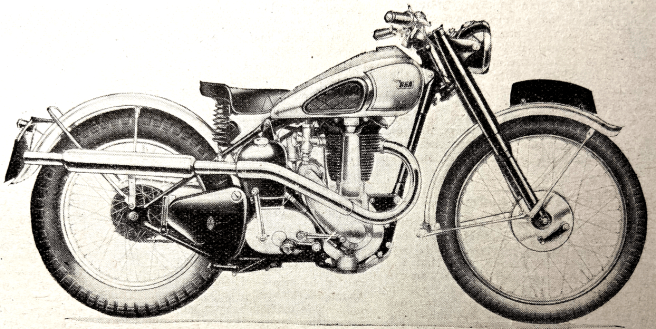

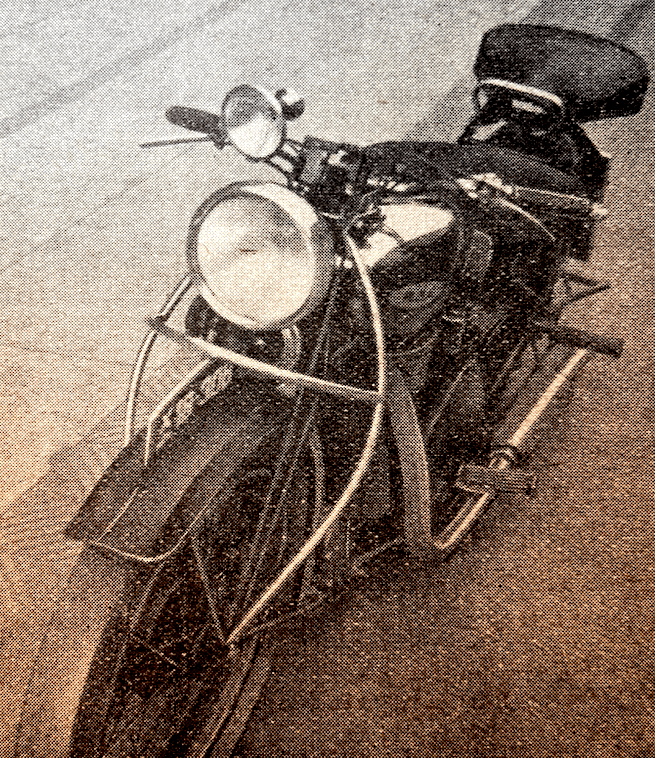

ROAD IMPRESSIONS: BSA C11

RIGHT FROM 1924, when the ’round-tanked’ two-speeder was introduced, BSAs have made first-class 250s—machines which invariably have been outstanding. To-day they are among the few making 250cc four-stroke motor cycles. There are two models, the side-valve, which is termed the C10 and the ohv mount, the C11. Except for the engine the specifications are the same. The machines are man-sized—built obviously with the fact in mind that large men are likely to ride 250s as well as small ones. On the C10 and C11 there is a wheelbase of some 52in, and a saddle height of approximately 29in, and the design is such that a man of a full 6ft can feel thoroughly comfortable. The machine I tested is a robust straightforward mount on which much care has been lavished in regard to the detail design. It is fitted with the BSA-Lucas coil-ignition set, which employs a combined contact breaker and automatic advance-and-retard mechanism, skew-gear driven from the timing gear. No air-control lever of any sort is employed, and there is no exhaust-valve lifter. Thus the controls of the machine are the twist-grip throttle, the clutch, the front-

brake lever, the rear-brake pedal and the foot change of the three-speed gear box. Hence it is a machine to which a novice can count upon becoming accustomed very quickly indeed. Control is particularly easy, and the steering and cornering are such as to give the rider a real feeling of confidence. In the course of the test I rode from one side of London to the other on a day when road conditions. were bad owing to grease and also covered a number of miles on roads which here and there were coated with ice. Starting proved very good. Even when there was frost the lack of any air control was not felt. With the coil ignition it was not necessary to indulge in long, swinging kicks on the starter pedal. Push the pedal down with an approximately correct degree of throttle opening and the engine would start. It idled well and proved reasonably quiet both mechanically and in regard to the exhaust. An interesting little point about the silencer is a small hole at the bottom close to the rear end to enable condensate to drip away instead of remaining inside the silencer to cause corrosion. The machine is a lusty performer. Acceleration is good, and there is beefy pulling on upgrades. The maximum speed is comfortably up in the 60s and, at the other end of the scale, the machine would trickle along in top gear at any speed above about 14mph. Not until approximately 50mph on the very slightly pessimistic speedometer (a good fault!) is reached does the engine seem to be hard at work. And this speed is one which can be maintained, if desired, up main-road inclines. Moreover, there is the very useful speed of 40mph obtain-able in second gear 9.8 to 1). Thus this is a motor cycle which can be counted upon to put up very useful averages. With its liveliness, nippiness and ease of handling, there is no question of having to ‘remain in the queue’. Like the steering and handling, both brakes are very good indeed. The front brake is smooth, powerful and easy to operate—everything that it should be in these respects. The rear also proved powerful and smooth; it requires a fair amount of pressure to apply it hard, which, in my view, is as should be the case on such a machine. On wet, grit-laden roads, several times a speck of dirt got between the drum and the water-excluder of the front brake and caused a tinkling, scraping noise. Riding position is of the upright, touring type, with the ends of the 29in-wide handlebars set back. The footrest hangers have hexagonal holes that mate with hexagonal portions on the ends of the footrest rod. The Terry saddle is non-adjustable, but the bars can be swivelled in their clip. The foot-change pedal is serrated internally and, therefore, also adjustable. I found the riding position of the machine as it arrived very good indeed, and the brake pedal came exactly where it was wanted. My view has long been that BSAs have studied riding position better than almost anyone. Fuel consumption at 30mph over an undulating, give-and-take road worked out at 102mpg, while checked over a distance of 199 miles, which included almost every conceivable type of work and of weather—not excluding bottom-gear crawling in dense fog—the consumption was approximately 84mpg. Oil consumption was of the negligible variety, and what pleased me immensely was that there were no oil leaks from the engine in spite of it being at times driven really hard. At the end of the test there were merely two very small smears around the timing-case joint, shown up by dirt collecting there. The 7in diameter head lamp gave a first-class driving light—powerful, if a trifle narrow for cornering, on the main

beam and well diffused, and without any obvious straying upward beams, on the ‘dipped’ filament. The weight of the machine, with roughly a gallon of petrol in the tank, was 294lb. It is an easy machine to wheel and to manhandle. It is also easy to put on the central stand if one sets oneself facing forward, one hand on the handlebar end, the other on the rear of the saddle, and, with the stand leg pressed on the ground with one foot, thrusts backwards on the cheek of the saddle, using the thigh for the thrust. Then there is no lifting nor any serious effort. Having regard to novices, a really easily operated stand seems desirable. Only one other point have I: the ignition warning light is rather too sombre in daylight, and may result in owners leaving the ignition switch on by mistake. There is no reserve tap for the fuel tank, but with no U-pipe between the two halves a small reserve is afforded—sufficient for two or three miles in my experience. To sum up, in the latest C11 ohv 250cc BSA there is a machine which one would use with pleasure and satisfaction on a lengthy, strenuous tour, for going to and from work, for pottering about the countryside or for putting up good averages of the A to B variety. It is economical, lively, robust and comfortable (the Dunlop tyres are 3.00-20, incidentally)—a machine one can very strongly recommend, as, indeed, I have done ever since these 250s were introduced.” —Torrens

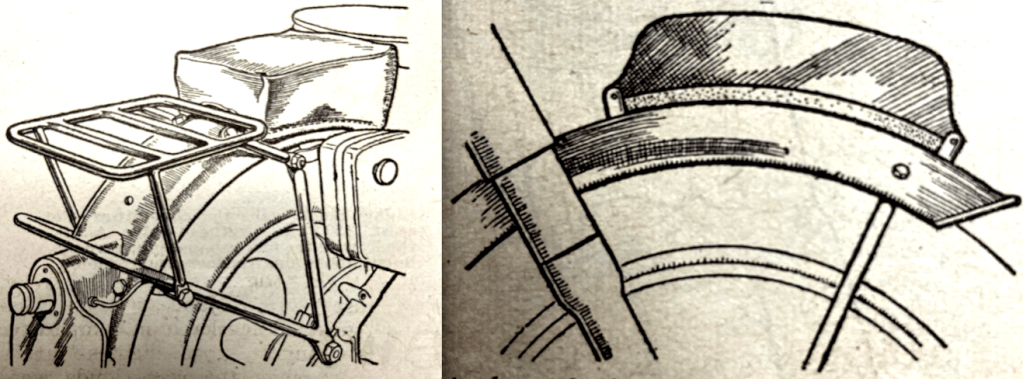

“I FANCY THAT far more riders would avail themselves of special weather protective devices if these gadgets were instantaneously at- and de-tachable. In this category stand windscreens, legshields, and hand guards. The vast majority of such fittings are designed and sold as accessories—not an efficient method, since an unnecessarily wide range of clips becomes inevitable, with so many makes of machine to be fitted. But supposing that a large manufacturer worked hand-in-glove with an accessory firm, standardised a complete set, and built his machine with incorporated lugs for the several mountings? A rider could then whip the gadgets on and off to suit his fancy and the weather of the moment. Moreover, the gadgets would be firmer, since a multitude of clip-on items will never remain tight without regular attention. I am quite, quite sure that this prescription is invaluable for windshields. The demand for legshields and hand guards is less clamorous.”—Ixion

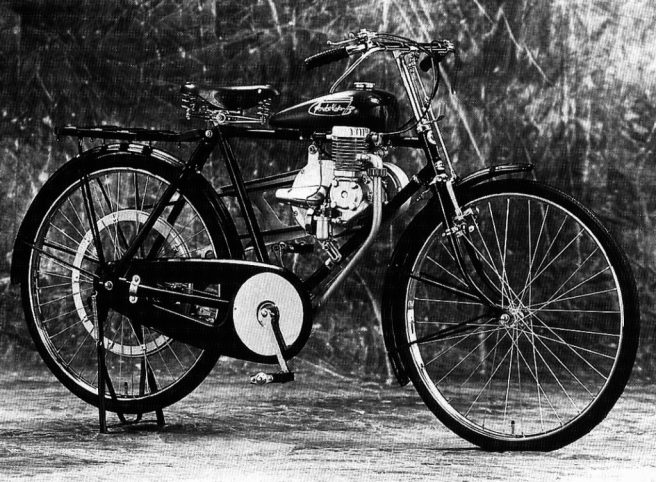

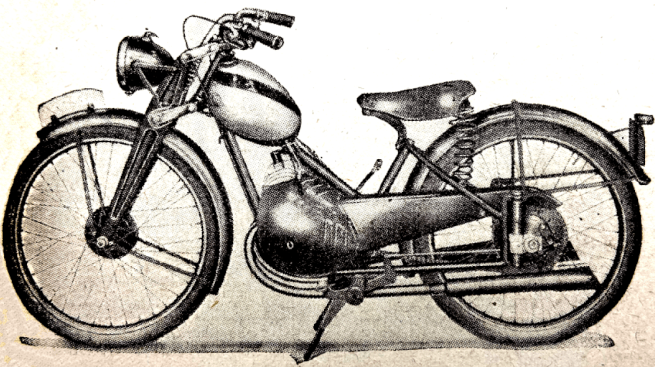

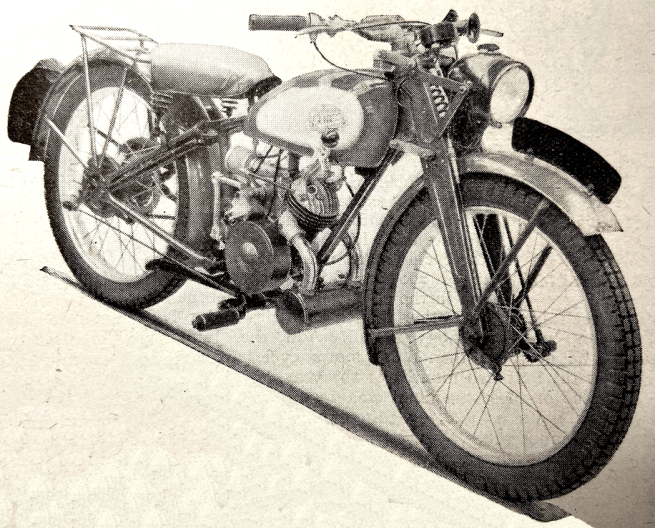

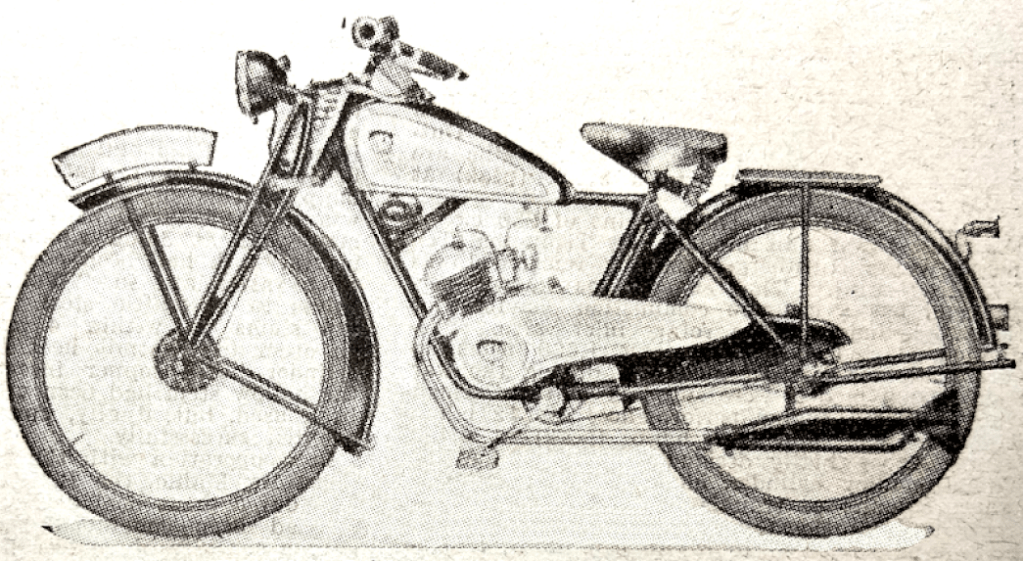

GARELLI RESUMED PRODUCTION of powered two-wheelers after an 18-year break. Instead of sporty 350cc two strokes the firm churned out diminutive clip-on ‘micromotori’ better suited to the needs of post-war austerity.

‘ORDINARY DAY DRESS for men on this occasion’. Thus runs a sentence in the Motor Cycling Club’s announcement of its dinner and dance to be held at the Porehester Hall, Bayswater, London W2. Why do not more clubs make a clear-cut statement on what one should wear? All too often the words on the ticket are ‘Evening dress optional’. It may be said that this leaves those who have evening dress and would like to wear it the opportunity of doing so and that those who do not possess it are thus told that it does not matter. My view is that where the statement is that dress is optional the thing is not to wear evening dress if you have it but to go in ordinary clothes—that is, I do not regard it as an option at all, at least in these days. Am I right or wrong?”

WITHIN A YEAR of its foundation Montesa won the 125cc class of the Grand Prix of Barcelona and went on to win theSpanish 100 and 125cc Championships.

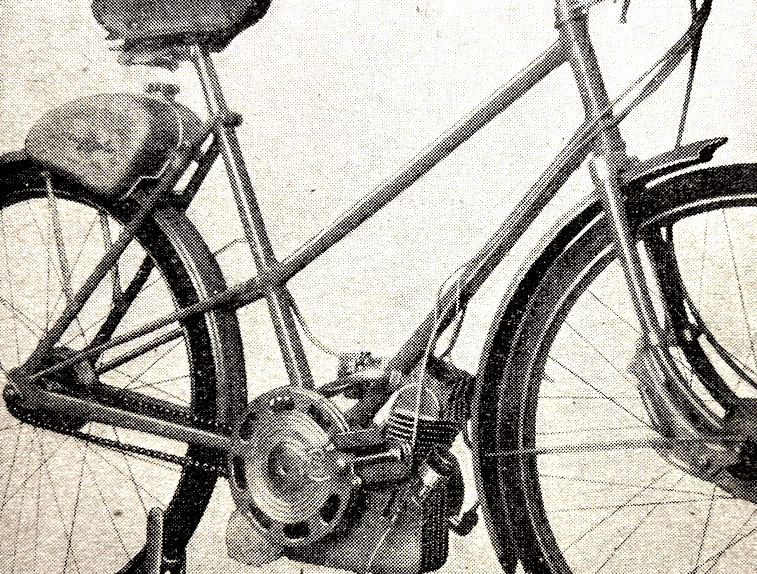

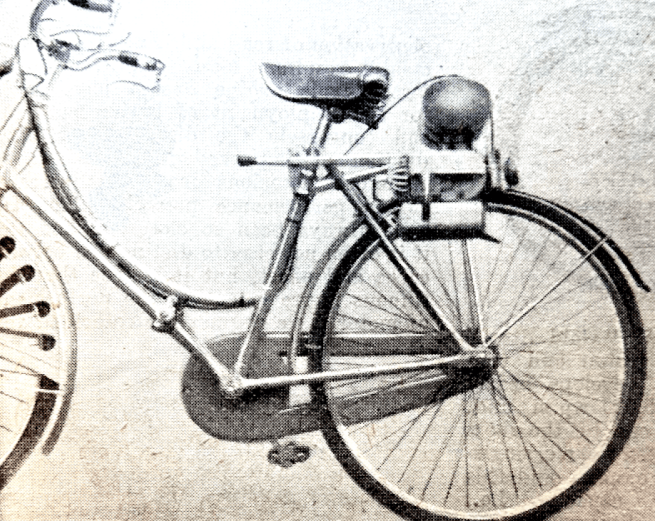

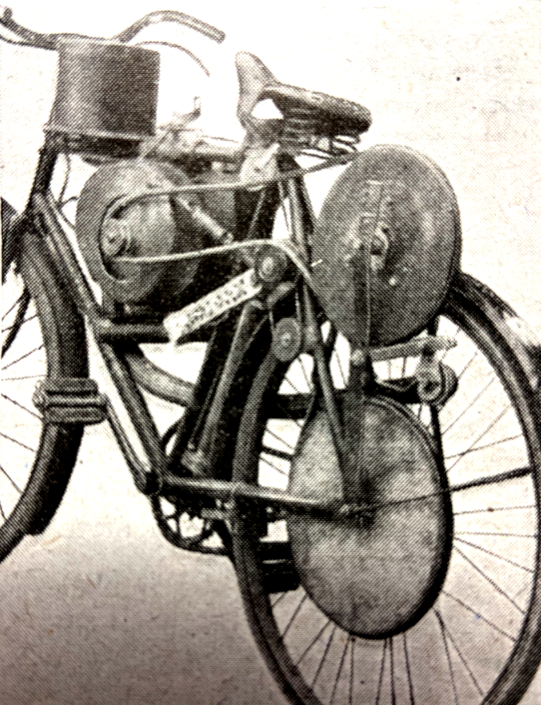

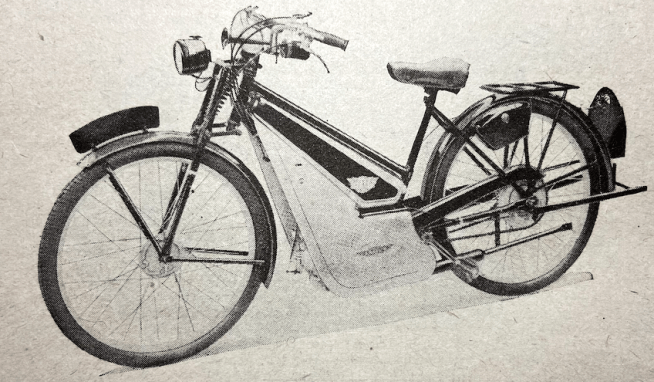

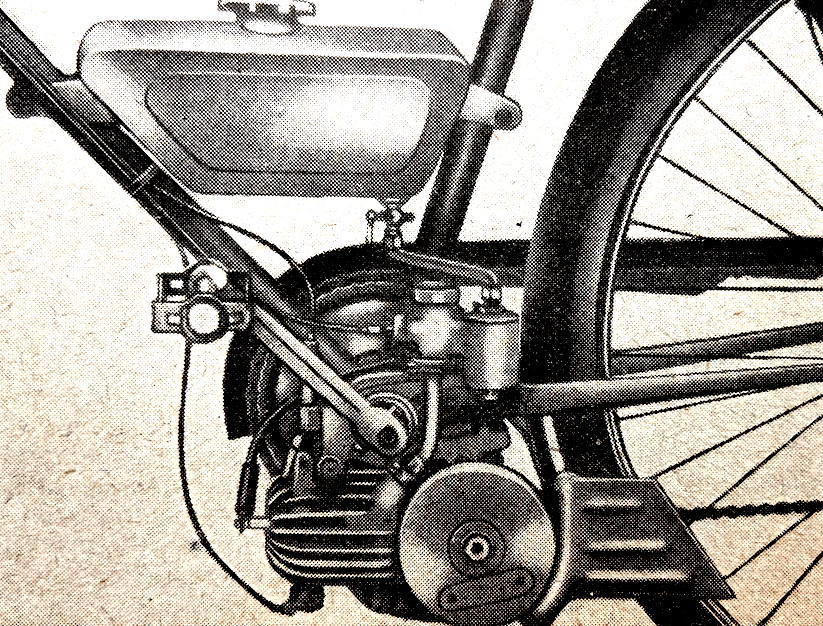

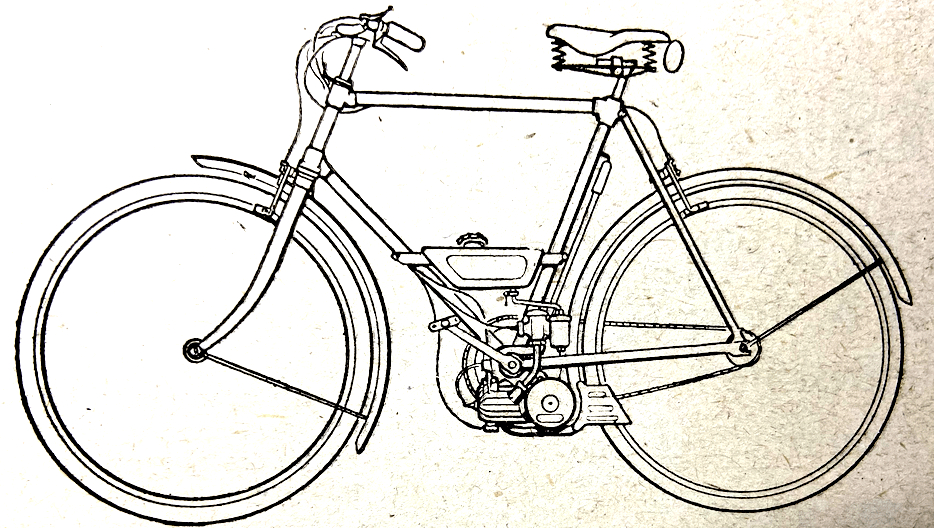

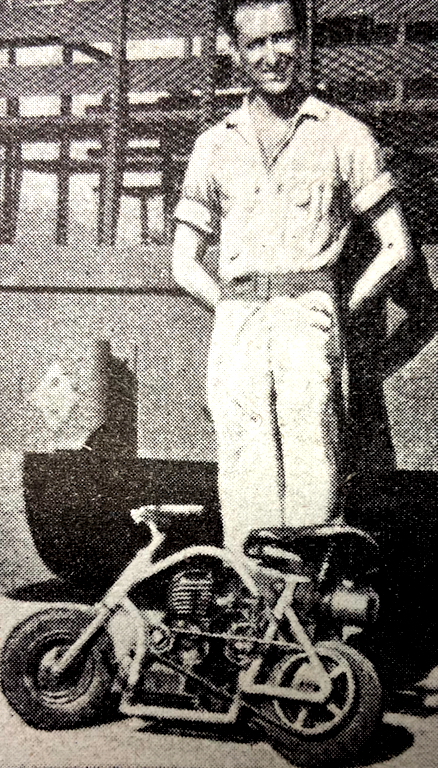

SOICHIRO HONDA acquired a batch of 500 ex-Japanese army 50cc two-stroke generator engines (designed to power radio sets) and fitted them to bicycles. The engines were produced by Mikuni Shoko which was, and is, famous for its carburetors—every engine was stripped, checked and reassembled before fitting. The prototype sported a hot water bottle as a fuel tank (legend has it that Soichiro found the bottle at home; it does not record Mrs Honda’s reaction). The engine was fitted over the front wheel which was driven via rubber friction roller a la French Velo Solex. The poor quality tyres available in post-war Japan couldn’t stand the strain so Honda quickly adopted a conventional engine layout with a V-belt driving the rear wheel. Soichiro Honda’s wife, Sachi, recalled: “‘I’ve made one of these, so you try riding it.’ That was what my husband said when he brought one of his machines to the house. Later, he claimed that he made it because he couldn’t stand to watch me working so hard at pedaling my bicycle when I went off looking for food to buy, but that was just a story he made up afterward to make it sound better – although that might have been a little part of it. Mainly, though, I think he really wanted to know whether a woman could handle his bike. I was his guinea pig. He made me drive all over the main streets that were crowded with people, so I wore my best monpe (baggy trousers worn by farm women and female laborers) when I took the bike…After riding around for a good while, I went back to the house, and my best monpe had gotten all covered with oil,” Mrs. Honda continued. “I told him, this is no good. Your customers will come back and scold you. His usual response was, ‘Oh, be quiet. Don’t fuss about it.’ But instead, this time he said, ‘Hmm, maybe so.’ He was unusually submissive about it.”

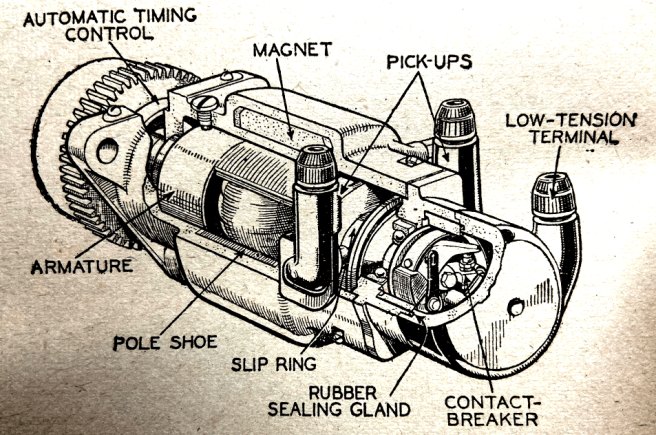

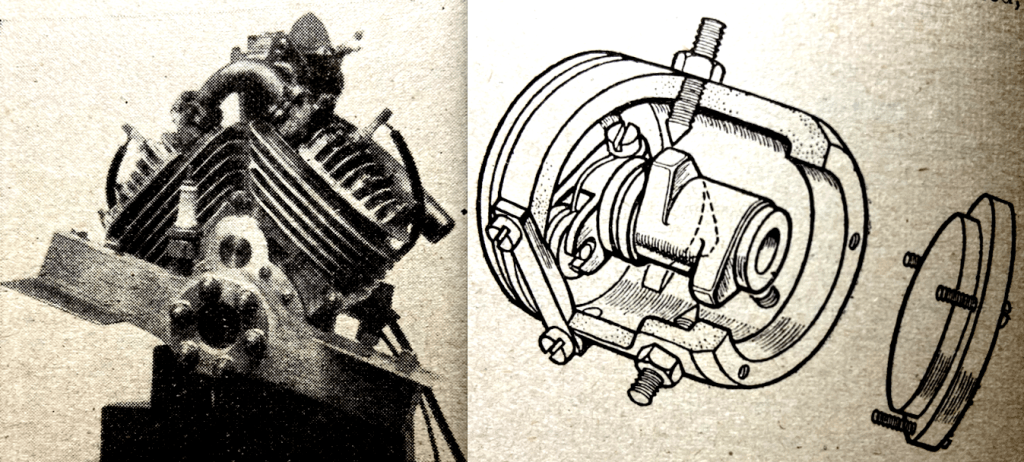

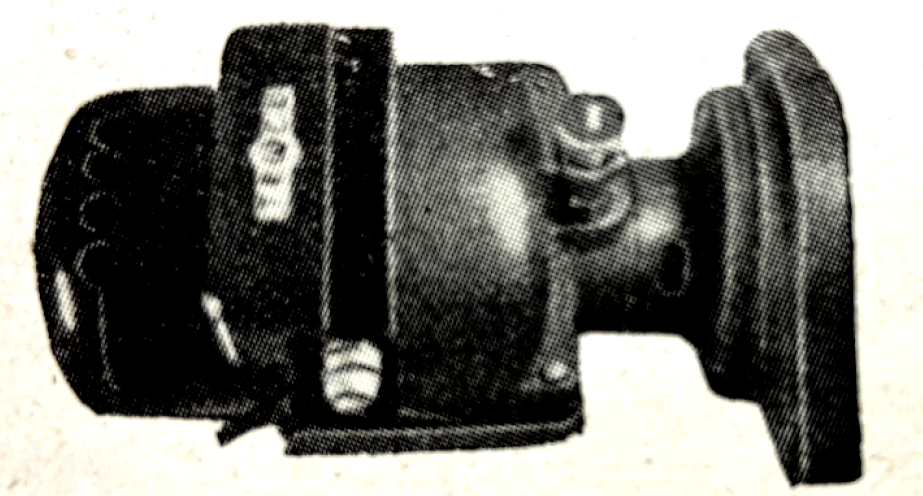

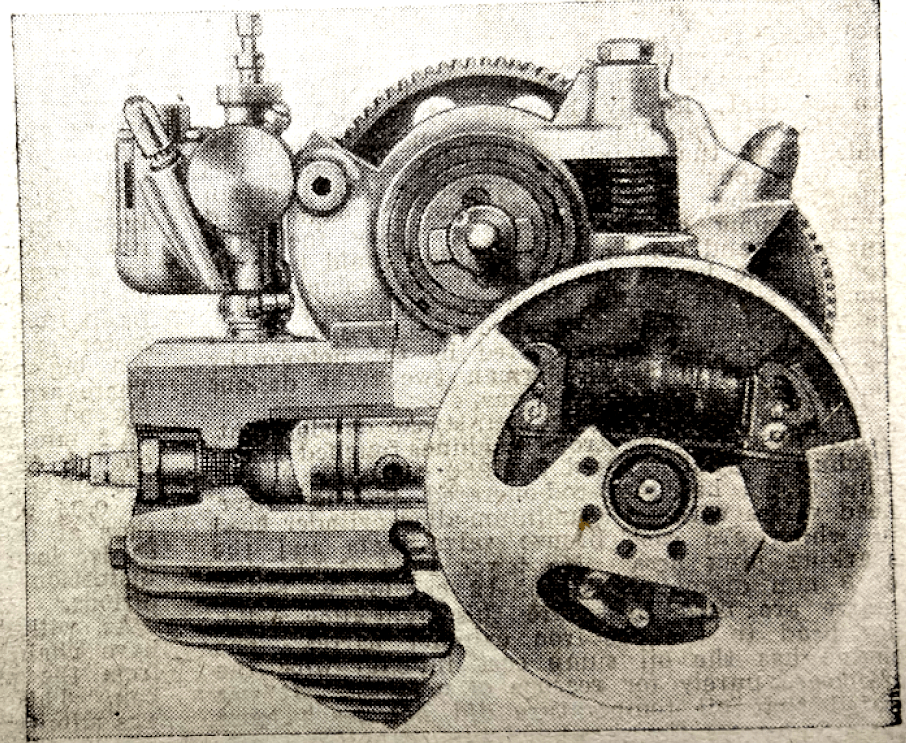

“OPINION IS VEERING in favour of automatic ignition controls. A number of those who maintained that manual operation was preferable are now admitting that even the most expert rider cannot hope to compete with an efficient automatic advance-and-retard. The emphasis should be on the word ‘efficient’. All automatic controls we have sampled to date have been of the centrifugal type. A few have conformed to the requirements of the engine with remarkable accuracy, which reveals that with some power units, particularly multis, such a device can be extraordinarily satisfactory—far more so than hand control. And it is an interesting fact that timed tests show an improvement in acceleration. Undoubtedly ‘auto-advance’ will become usual, and it is important that it should be widely realised that it is a device which ought never to call for any excuses. In short, something close to perfection has already been achieved by certain manufacturers and there is thus a standard to which others need to work. Over coil ignition, notwithstanding the promised sets that will enable the engine to be kick-started with the battery fully discharged, or with no battery at all, there are still grave doubts in many motor cyclists’, minds. Thoughts of the past are the reason. We favour coil ignition, believing that it has big advantages and that in its latest form, well made and properly fitted, it can be entirely satisfactory. Coincident with all the proposals for coil ignition, however, there have been important developments in magnetos…”

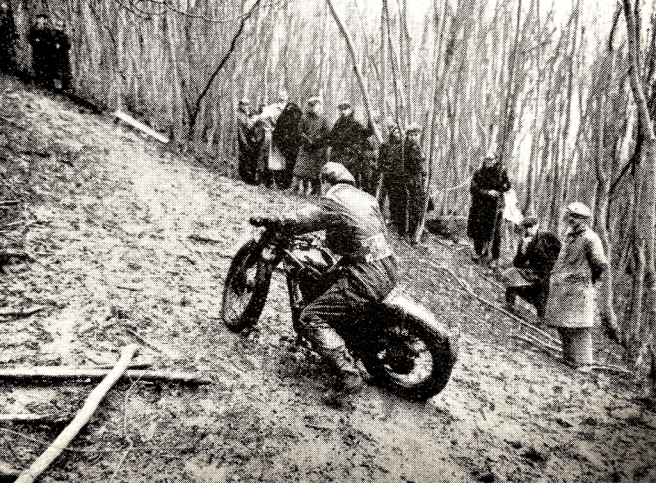

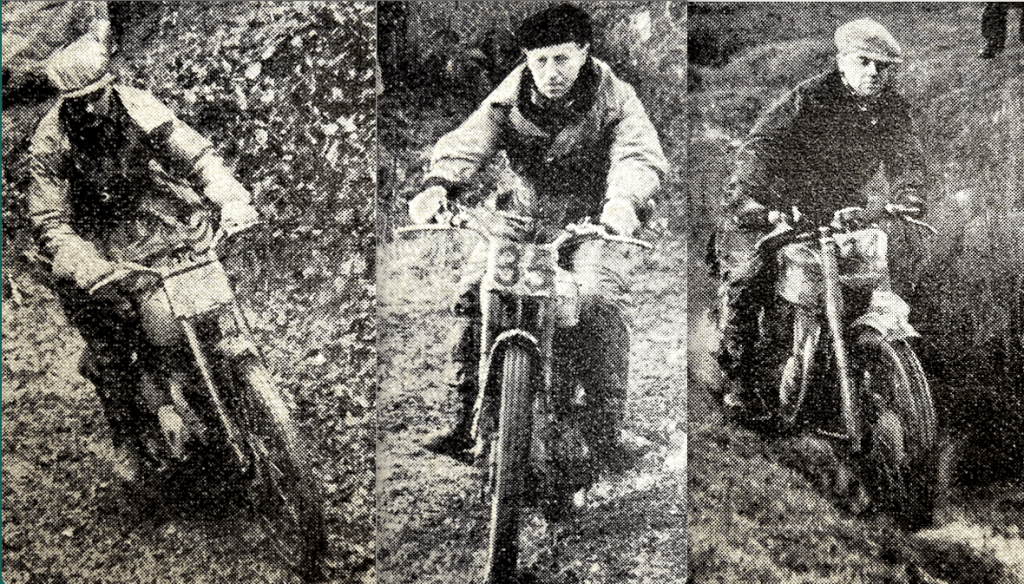

“A FEW MONTHS AGO in discussing machines for trials the Editor remarked on the fun to be obtained from riding a Flying Flea in competitions. It seems that quite a few intend to have a crack at trials on 125cc two-strokes. I have not seen the entries for Saturday week’s Colmore Trial yet—they do not close until to-day—but I heard the other day that AR Taylor was intending to use a 125cc Excelsior, and now I learn that Barry Smith, son of Major FW Smith, TD, JP, the managing director of Royal Enfields, will ride a 125cc Royal Enfield in the Colmore if he is still at home. Barry has taken a Flea through several trials of late, and on the Antelope MCC’s event the report was that no one enjoyed the trial more than he did. Apart from the kick there is to be obtained in piloting a machine of small cc through a trial, there is the fact that one’s trials model is inexpensive!”

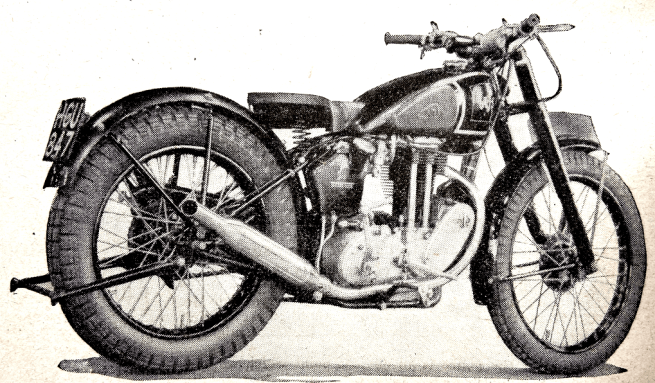

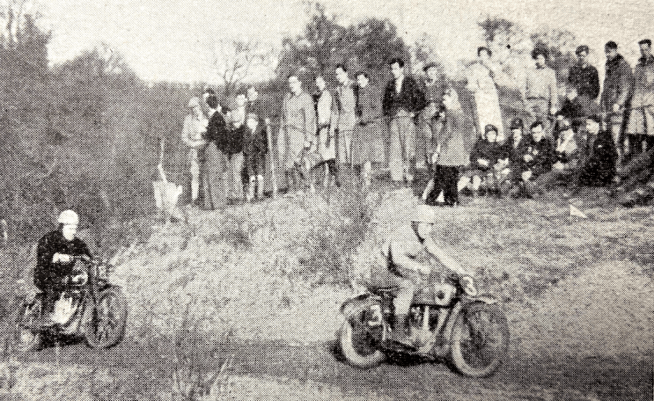

THE CLASSIC ONE-DAY TRIALS resumed in February with the Colmore Cup Trial; Fred Rist and Bill Nicholson came first and second, both riding competition versions of Beeza’s new B31 (effectively a pre-war B30 with Ariel telescopic forks. Judging by the popularity of the Matchless G3L, its Beeza counterpart would have made an excellent military mount. The B31 proved itself a dependable, lively all-rounder). Before the end of the year the British Experts Trial was back too; solo and sidecar honours went to Bob Ray (Ariel) and Harold Tozer (BSA).

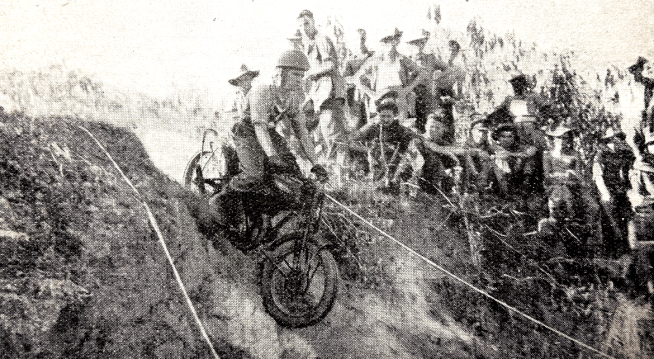

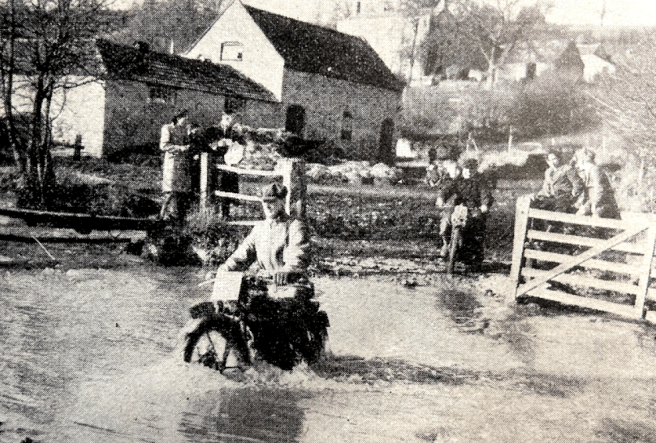

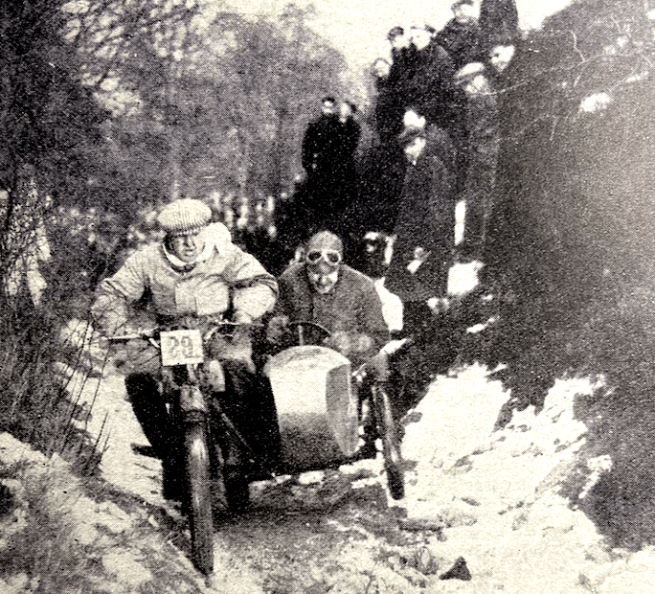

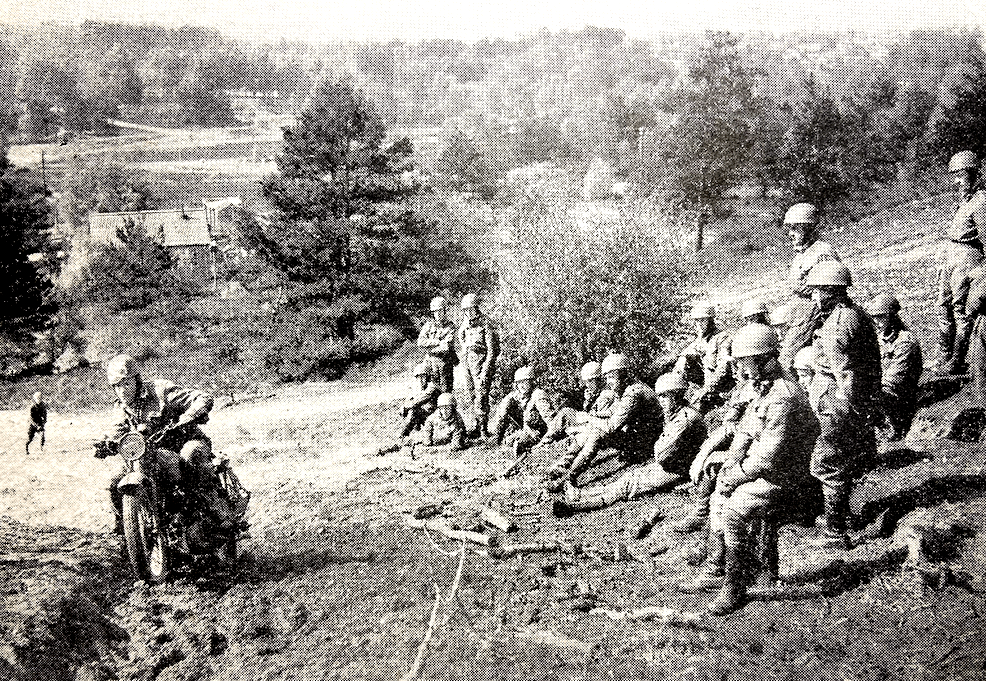

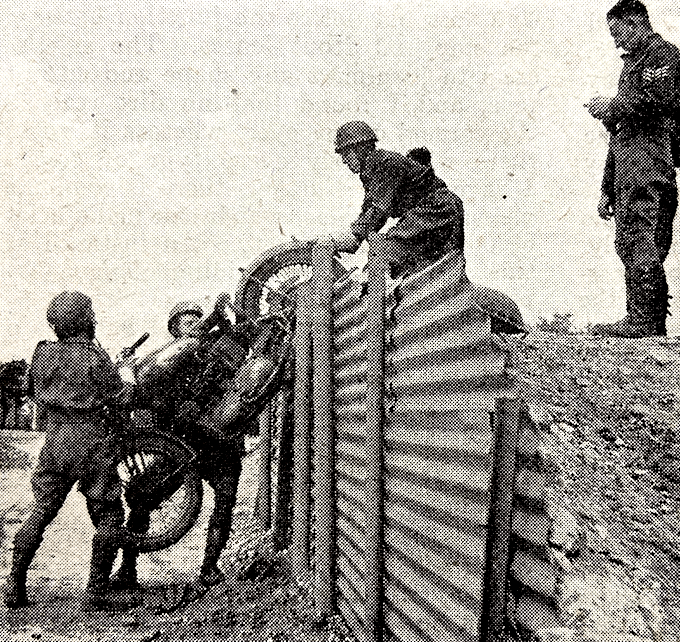

“ALTHOUGH NOT STRICTLY of the ‘North’, being more truly of the East Midlands, the Bemrose Trial nevertheless has a distinctly northern flavour. The Derby &DMCC takes the Bemrose route well up into the Peak District, and since that ‘North’ which comprises West Yorkshire. East Lancashire and East Cheshire is rather starved in the matter of classic open trials there is always a good ‘local’ entry both from those quarters as well as from the many clubs in the Derby and Nottingham districts. Hence the entry list of 160 last Saturday—a total that could easily have been exceeded had Mr Secretary Fred Craner dared to have accepted all who offered. But because it is not possible to get enough marshals and observers on a Saturday morning the start cannot be before 1230pm and the available daylight precludes the acceptance of a bigger number of competitors; as it was, the intermediate time checks were eliminated in order to save delay. But with the best will in the world, time loss extended the string of riders. A minute or two here, a quarter of an hour there, and a cumulative delay became apparent. The early members were on time according to programme at the many observed sections, but the later the numbers the later their appearance and the longer their passage through any one section. At the finishing point at Hartington O/C Craner was getting quite worried as the day went on. Messengers were sent out. ‘Could this or that hill be washed out?’ And each time the answer came back ‘No’, because already some of the early number. had been up and had been credited with clean performances. So it had to be. Only the last section of all, half a mile away from the finish, was cut out. And the upshot was that most of the late numbers climbed Pilsbury when the light had gone and they could not clearly see the path to follow. Naturally they finished well after the time when lights were put on and many without lamps were in a quandary about getting home. There was a run on the available stock of pocket torches in the village garage at Harlington. The contingent from West Yorkshire, always ready to throw a party. were speculating where to carry out such a project, while a team from Cambridge were speaking bravely of riding through the night to that home of learning. Nobody could quite weigh up why the lateness had crept in. Delays on any one hill had not been excessive, except perhaps at Hunger, early on. Route marking was excellent and marshalling on observed sections was generally expeditious. It just seemed that the entry was too big for the time allowed and tint the moving finger moves, and keeps on moving on. Starting from Cromford, near Matlock, on a bright and sunny, the prospects were only marred by the sight of snow on the hill tops and the thought that the deeply frozen ground might be thawed to a fairly treacherous state. The first section, Dethick Lane, confirmed the dread. Its mixture of semi-solid slime and rocks proved difficult. Fortunately for the many who had to foot, and much to the annoyance of the few who were clean, no observers turned up, so both failure and success went unrecorded. Twelve miles from the start, Hunger Hill, at Holymoorside, near Chesterfield, was reached. Hunger is not perhaps no difficult as it used to be, but the acute left bend on a shop gradient, with step-like rock ledges ‘running away’ from the line of travel, provide a fine test of steering control and engine pulling power from low revs, because the steps are too deep to take at speed with any certainty, although an occasional rider, if the luck is with him, may make a fast ascent. One thing differing from prewar trials was the outstanding superiority of telescopic forks in dealing with a rock staircase!”

“BEING DISINCLINED TO ALLOW themselves too much opportunity to become soft, the Bradford &DMC ran a decidedly sporting event at Altar Lane, Bingley, and sampled some astonishing observed sections all within a very small distance of the starting point. Few districts can he much better placed than this part of Airedale for rough and rugged hills, bleak and barren moorlands and the comforting thought that one can almost literally jump down off any piece of high ground and land on a bus route with the chance of getting home for twopence, no matter how the model has been bent. Altar Lane, the starting point, was itself once used as an observed section in the distant days, but now it merely provides a means of approach to certain rocky paths that wind through the woods that flank it. There were two parts of the first of these paths that spoiled most of the clean sheets within the first ten minutes…”

“HERE IS YET ANOTHER item which profoundly affects our individualistic passions anent motor cycling. I can remember a time when the number of firms exhibiting motor cycles at the annual Show climbed far into three figures. That was the age of the small shop and the tiny output. Henry Ford quickly taught the world that the day of the small craftsman was past, and that efficiency and cheapness pivoted on mass production by machinery. In the motor cycle world we have not quite reached the stage at which the British production is confined to a few factories, the Big Five, the Big Seven, or what you will. But we are getting quite near that stage. Such epochs are unwelcome to the sturdy individualists. Options and variations are anathema to the mass producer—they create eddies in the smooth flow of his output. He aims at a single standard model, and no options. This annoys his public and he is driven to a mild compromise, maybe lists more models than suit real efficiency, and catalogues a number of bolt-on options at the tail of his booklet. Hence mass production has its drawbacks for a faddy enthusiast. But let him not forget that thanks to mass production he is buying an extraordinarily good machine for about half what it would have cost him under the old ‘small shop’ regime. What we lose on the swings in respect of variety we more than recover on the roundabouts in the shape of value and economy.”—Ixion

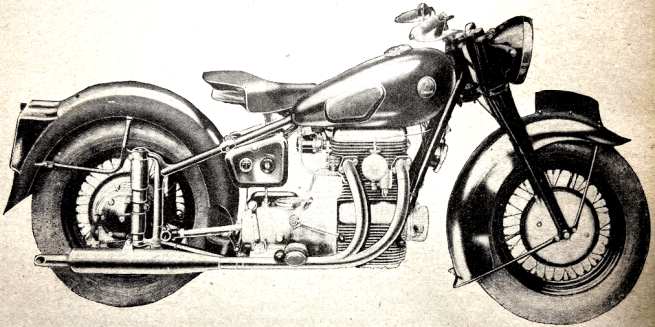

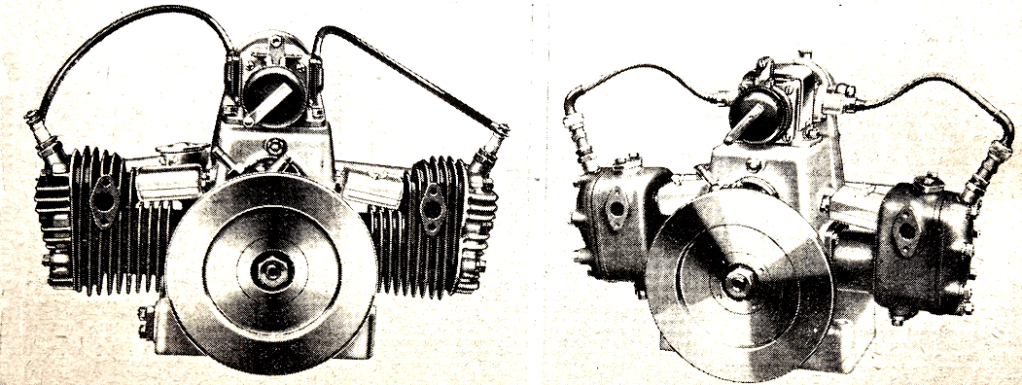

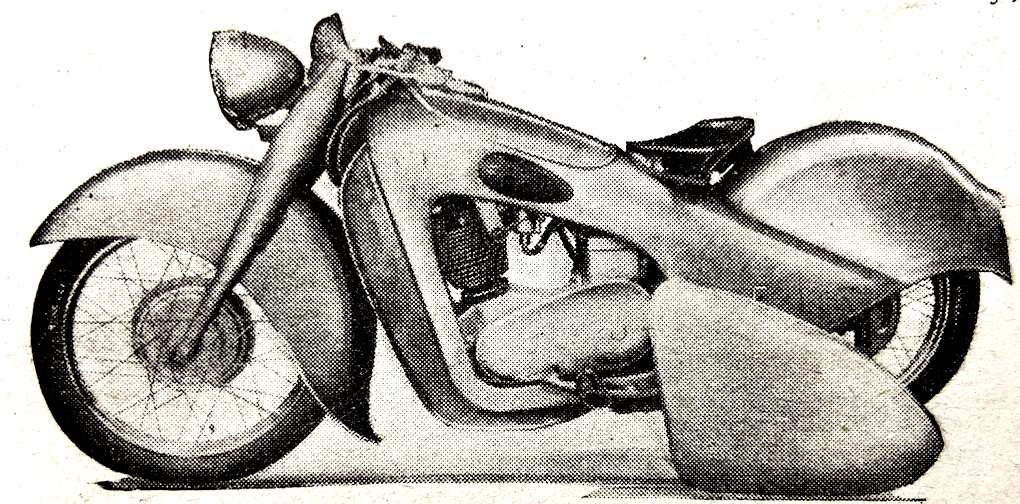

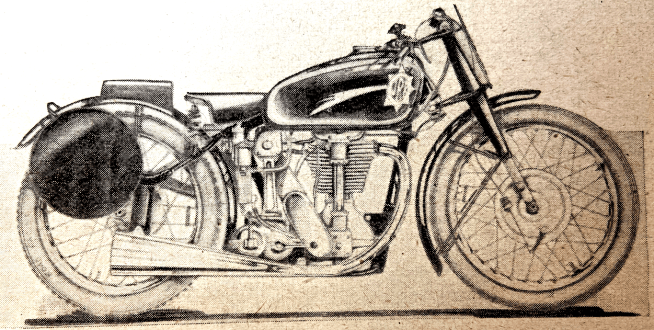

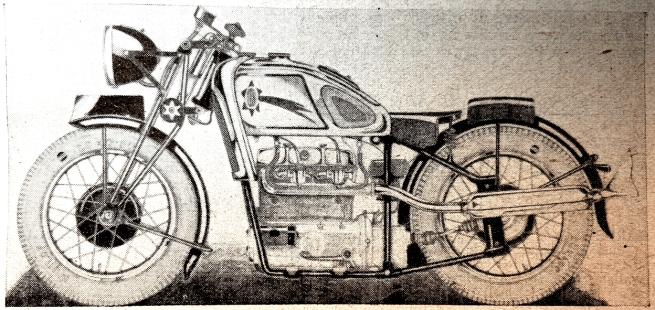

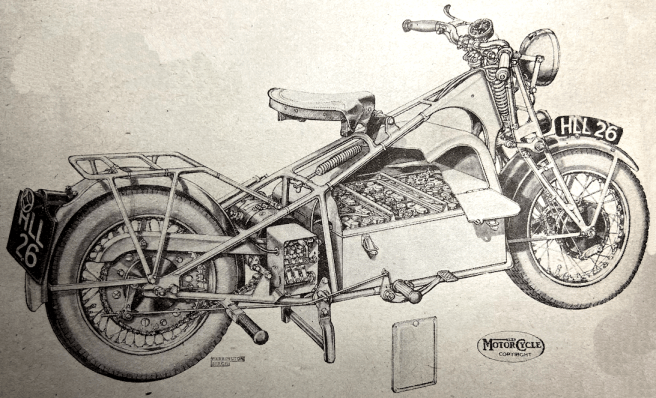

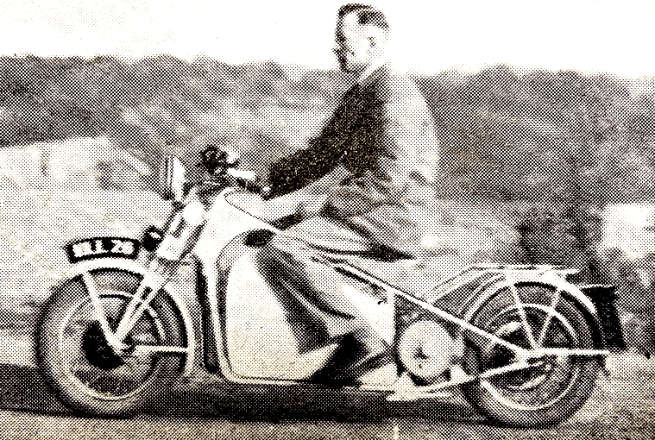

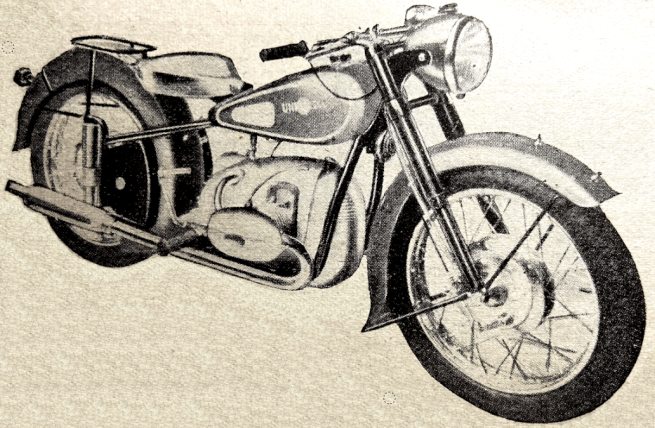

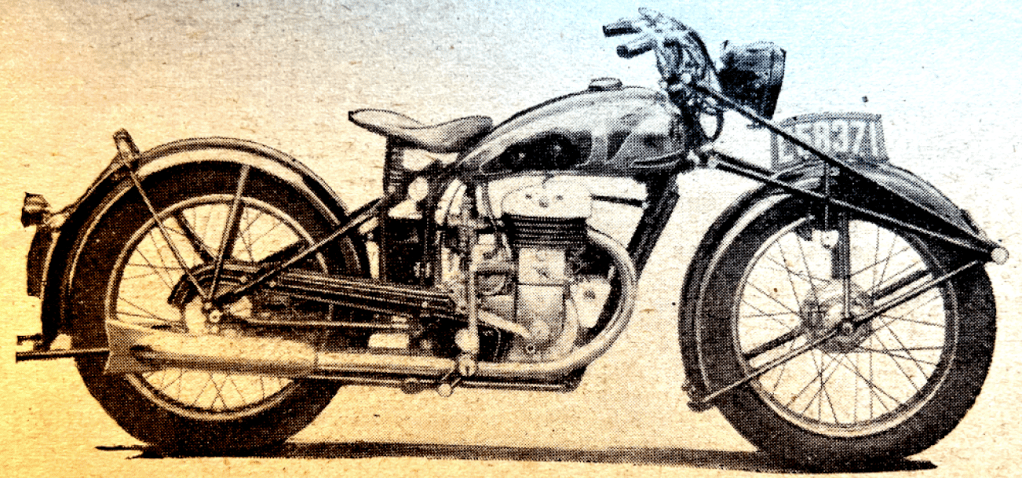

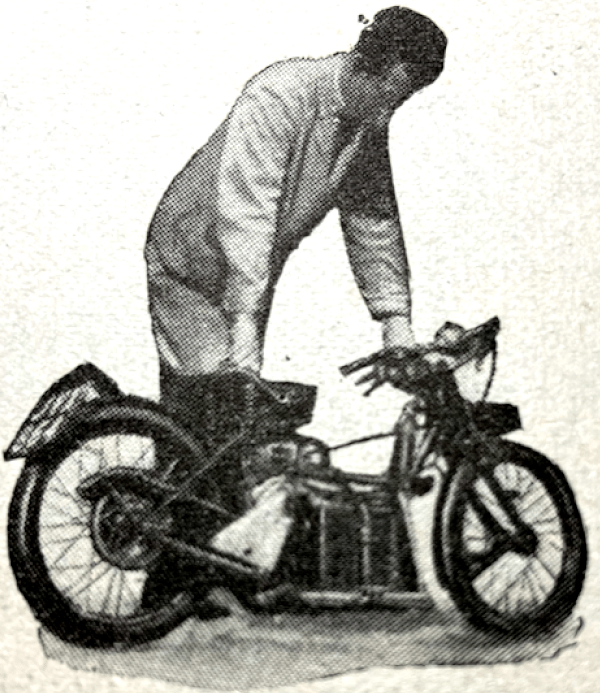

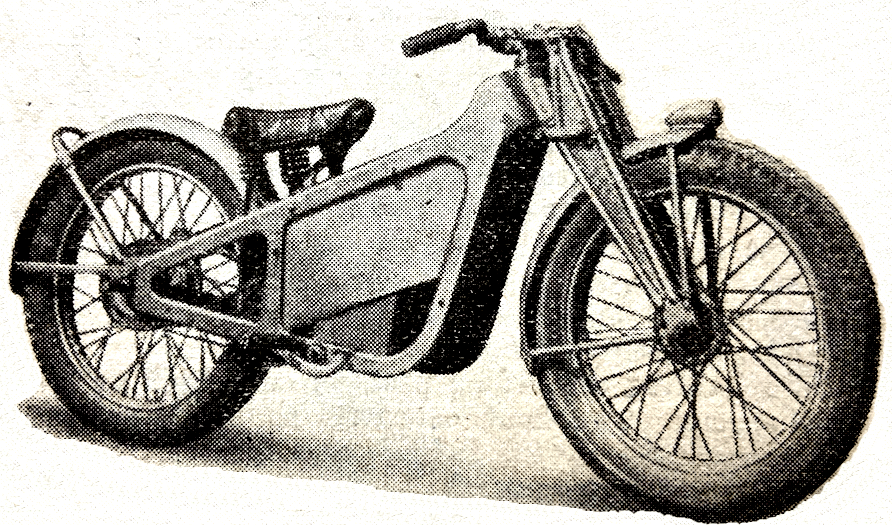

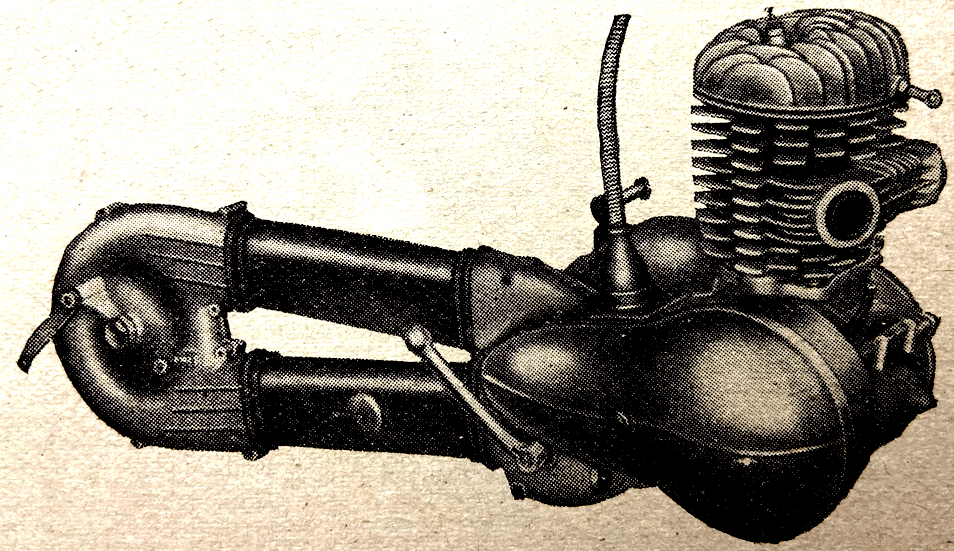

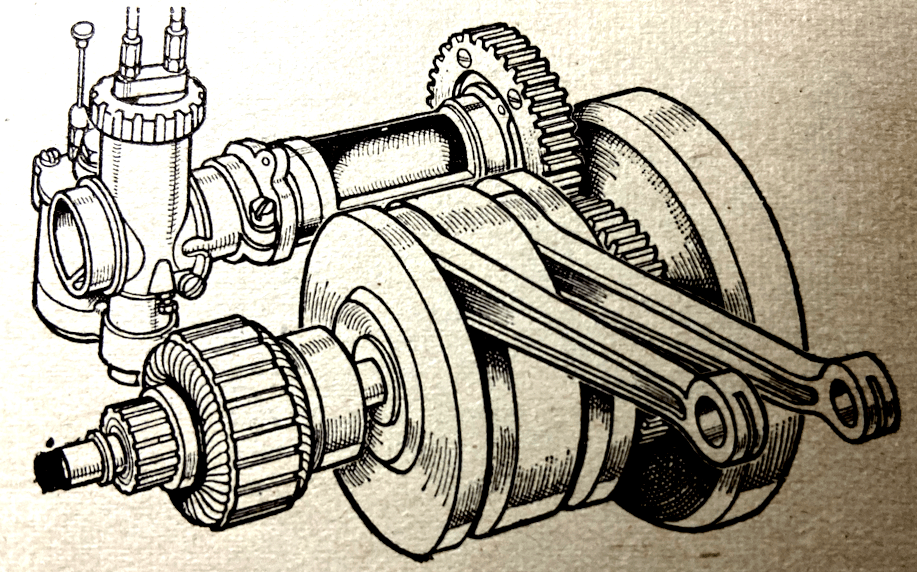

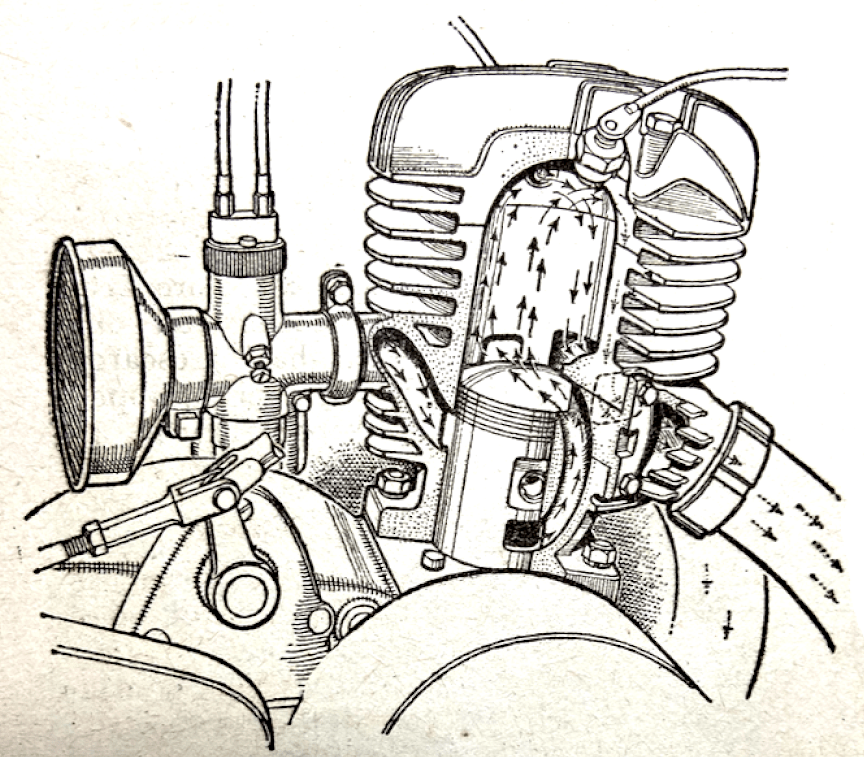

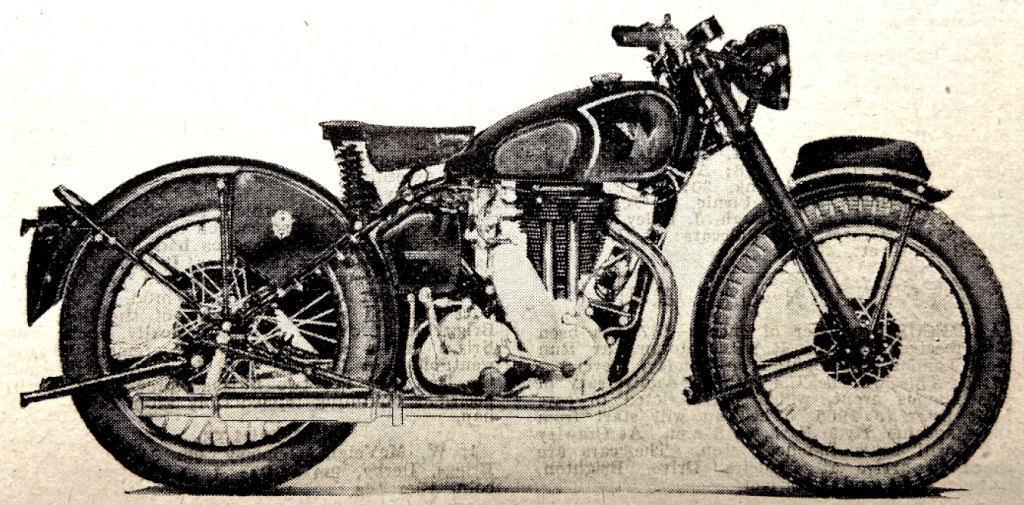

BSA CASHED IN ON ITS acquisition of Sunbeam with the launch of “a new kind of motorcycle”, the Sunbeam S7, built in the firm’s wartime ‘shadow’ factory in Redditch. The rolling chassis was pure BSA, including the latest telescopic forks and plunger rear suspension; rider comfort was further enhanced by 5.00×16 ‘balloon’ tyres. But the Erling Poppe-designed driveline comprised a unit-construction ohc 500cc in-line twin with car-style clutch and four-speed gearbox. The Blue ‘Un was impressed: “On the road, the new models display fresh and delightful characteristics. The gear change of the engine-speed gear box, for instance, is perfection: as good as, if not better than, the best that is provided by any countershaft gear box of to-day. The flexibility of the machine, too, is outstandingly good. In the recent past. harshness

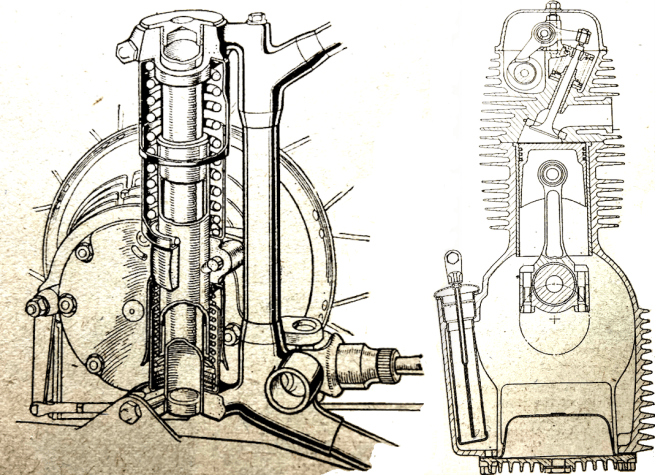

has been accounted inseparable from shaft drive. With the new Sunbeam a speed of 10mph in top gear can be used without a semblance of thrash or flutter. This is so with the prototype, which has now covered some 18,000 miles, ten thousand of them a duration test…Behind the design is that great driving force who has been seen on the recent big trials, and, incidentally, has ridden the prototype himself, Mr James Leek, CBE, managing director of Sunbeams. The engineer responsible for the conception of the sleek design with its many ingenious features is Mr E Poppe, the chief development engineer. No fewer than 30 patents are pending in regard to the whole machine. What were Mr Poppe’s aims? He has sought to produce a really reliable, smooth-running and comfortable motor cycle, which will have a long life, call for a minimum of attention and be clean to ride, a machine which has all these features without being in any way freak-ish. A civilised motor cycle, he says. A first glance at the machine suggests massiveness and great weight. The spring-framed 500cc model will come out at just under 400lb, it is expected. This is with the big tyres. The prototype weighs 4251b…The machine incorporates just about eery feature for which enthusiasts have been clamouring, plus many more. The brief specification is: Vertical twin

overhead-camshaft engine with the crankshaft in line with the frame, unit construction of the engine and gear box, shaft drive, telescopic front forks, plunger-type rear springing and quickly detachable—really quick to detach—wheels. No bald statement such as this, however, can do the slightest justice to the new design. One of the aims, implied in the word ‘cleanliness’ used by Mr Poppe, has been to ensure an engine that is oiltight and remains so. There are no oil pipes inside or outside the engine unit and no joints which, if broken during overhaul, are likely to seep oil later. A single finned light-alloy casting constitutes the cylinder block and crankcase. Beneath, there is a finned light-alloy sump plate, while above are the one-piece Y-alloy cylinder-head casting with its ten protruding-downwards, fixing studs and, at the very top, a polished-aluminium rocker-box cover…The engine, in its touring form, develops 23-24bhp at its peak, namely, 6,000rpm. It gives a very flat torque curve. Maximum bmep is 128psi at 4,000rpm…The front forks are not, as might be expected, hydraulically controlled, but they are, of course, telescopic forks. They are telescopics with the springs arranged centrally just in front of the steering head, which takes the load direct. In the spring box there is a variable-rated compression spring, with a rebound spring inside. The damping inherent in a plunger system has been found adequate, and this applies also to the rear suspension…Great attention has been paid to the electrical side. Beneath the saddle, mating one with the other, are two separate boxes. On the near side is a ventilated lead-lined box which contains the battery. A

special arrangement of rubber buffers is used to support the latter. In the other box are the coil, regulator and cut-out, and on the outer face of it are mounted the ammeter and the lighting and ignition switch. This last will have a Yale lock. Since the distributor is on the rear end of the camshaft a very compact wiring arrangement results, and there is, of course, complete weather protection. A central rolling-type stand is fitted. This will be provided with a trigger release behind the tool-box. At present the ratchet which prevents the machine rolling forwards is operated by the initial movement of the brake pedal, but operating brake pedals, it has been decided, is something which holds a fascination for many! How does the prototype perform on the road? Already, something been said about its exceptionally good top-gear performance, the delightful gear change and the quiet running. Starting, idling, braking—all are first-class. There has been some roughness in the original engine, a matter that is being investigated. The handling of the machine can be judged from the fact that within minutes of taking over the model The Motor Cycle man was in the 70s. A rider lying down to it can obtain over 80mph. This is with the standard or touring engine. With the rider sitting up tourist-style the machine will hum along at a full 70mph. In view of the discussions on large tyres, the fact that the machine handles so excellently at high speeds is particularly interesting. The 4.75in section tyres…are special motor cycle ones and the rims wide. At low speeds the steering is a little heavier than usual; on the other hand, there is the superb feeling of confidence the large tyres give on icy or greasy roads and the comfort. The machine, with its fore-and-aft springing, is delightfully comfortable. Altogether, the new Sunbeam is a most remarkable design—a thrilling design.”

The first batch off the production line were sent out to the South African police who but returned them with complaints of vibration problems; BSA duly rubber-mounted the engine.

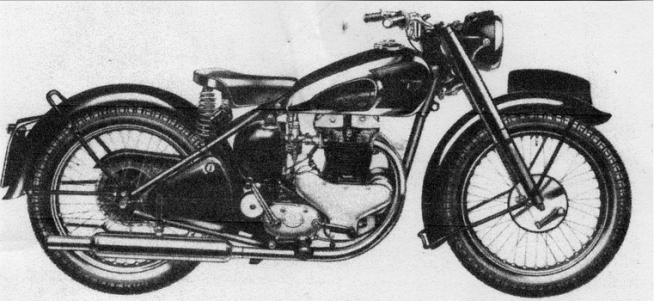

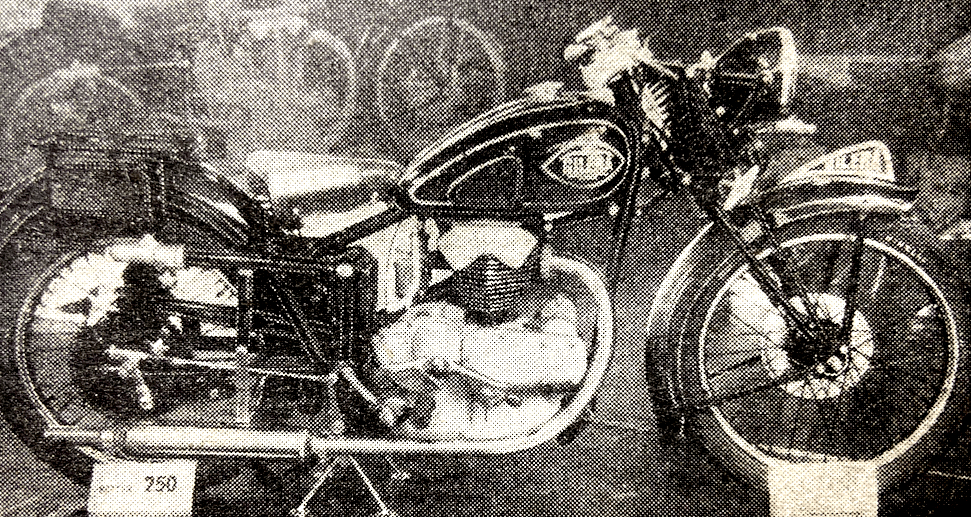

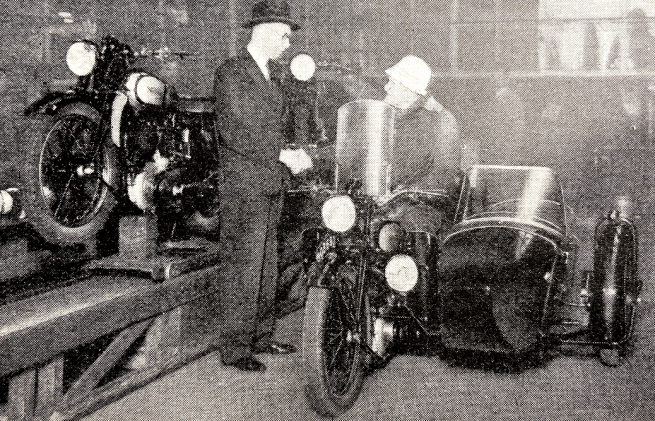

ALSO NEW FROM BSA was its reply to the Triumph Speed Twin: the 500c ohv vertical twin A7. Designed by Val Page, it had a number of features in common with the Triumph 6/1 he had built for Triumph in 1933. Having been delayed by the war, the A7 was launched in the autumn at the first major postwar show, the Paris Salon, where the Beeza twin was seen by more than 800,000 enthusiasts. Inevitably most of the exhibits were pre-war designs though FN did come up with an unusual front fork suspension incorporating steel springs and rubber bands.

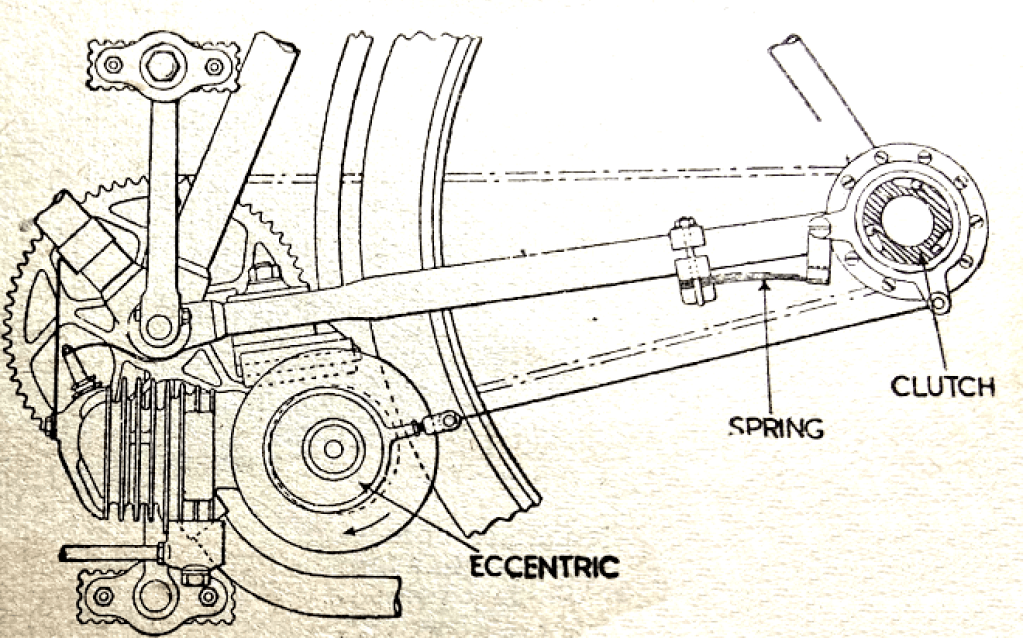

TRIUMPH HAD LED the way with its vertical twins; now it led the way again by offering them with sprung-hub rear suspension. It was a clever way of incorporating rear suspensioninto a rigid frame but with only a couple of inches of undamped springing it was a blind alley (and stripping down a sprung hub has ben known to send springs through shed roofs).

TITCH ALLEN CALLED A MEETING of enthusiasts to form the Vintage MCC, dedicated to the appreciation and preservation of old bikes. They classified machines as veteran (made before 31 December 1914) and vintage (made before 31 December 1930).

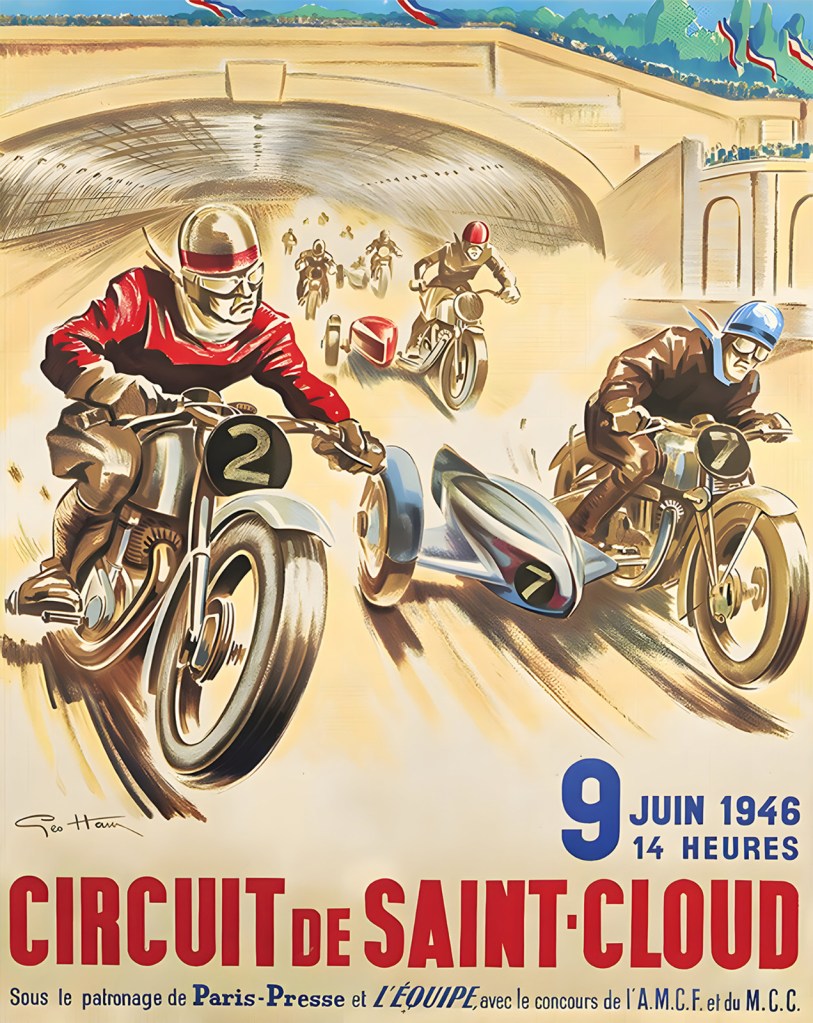

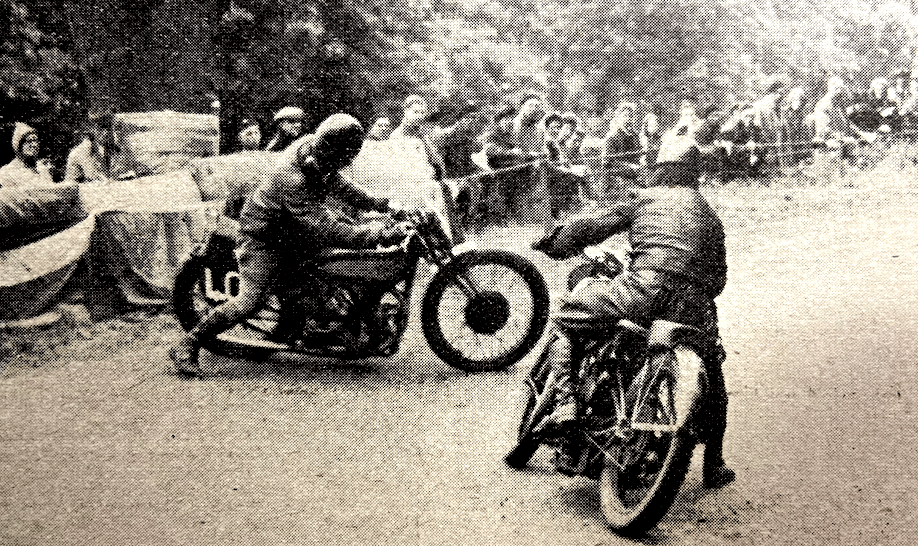

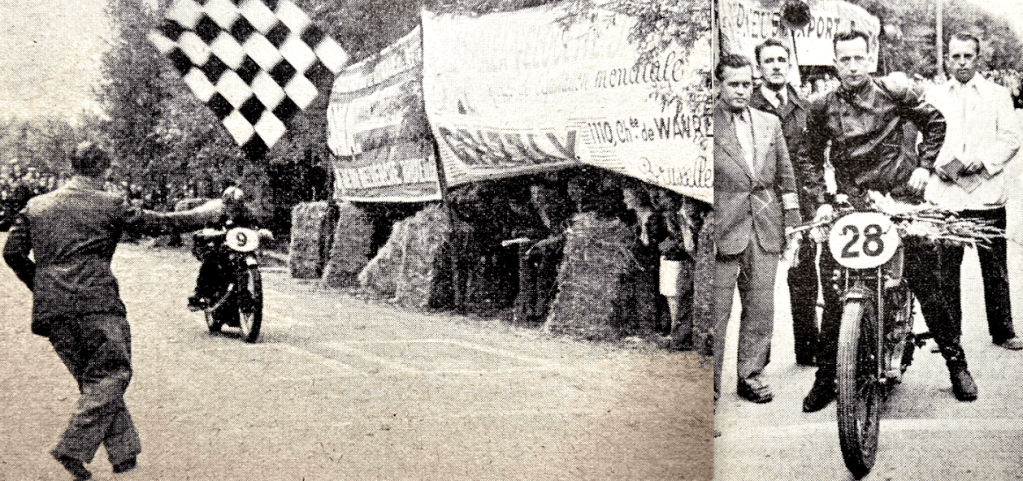

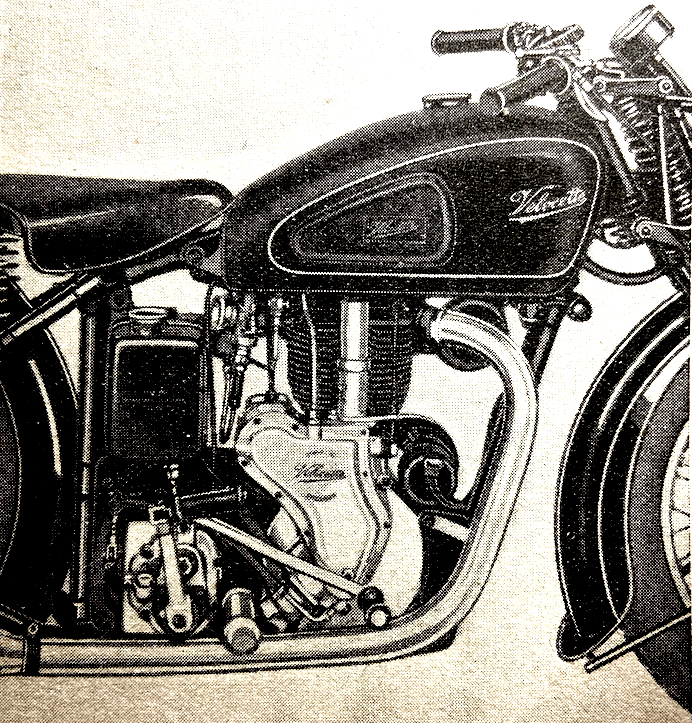

THE SUNBEAM MCC TEAMED up with the Belgian Motorcycle Federation to resume Continental road racing with a meeting at Le Zoute. A dozen Brits crossed the Channel and dominated the proceedings. Jack Brett headed the 250s on an Excelsior; Peter Goodman took 350 honours for Velocette (he was the grandson of the company’s founder) and Maurice Cann rode the fastest 500—but it was a Moto Guzzi.

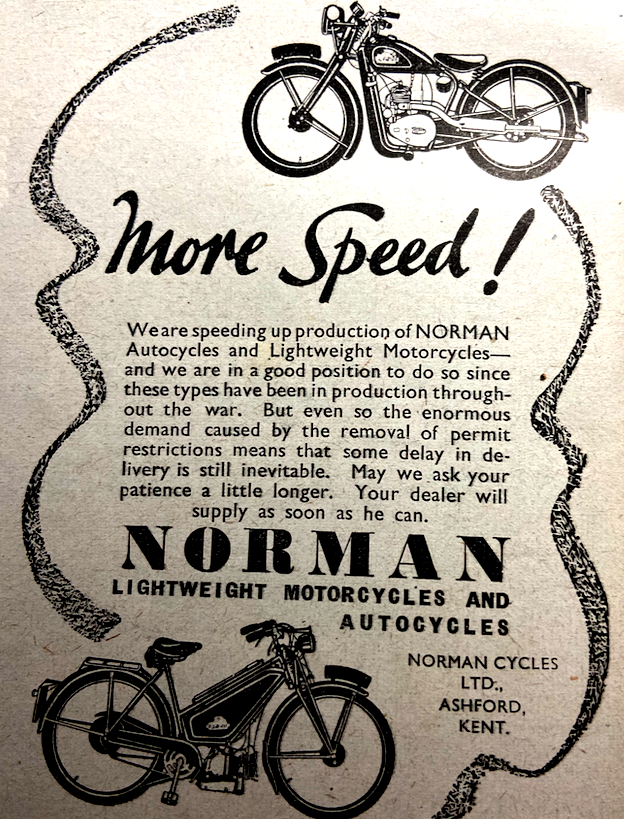

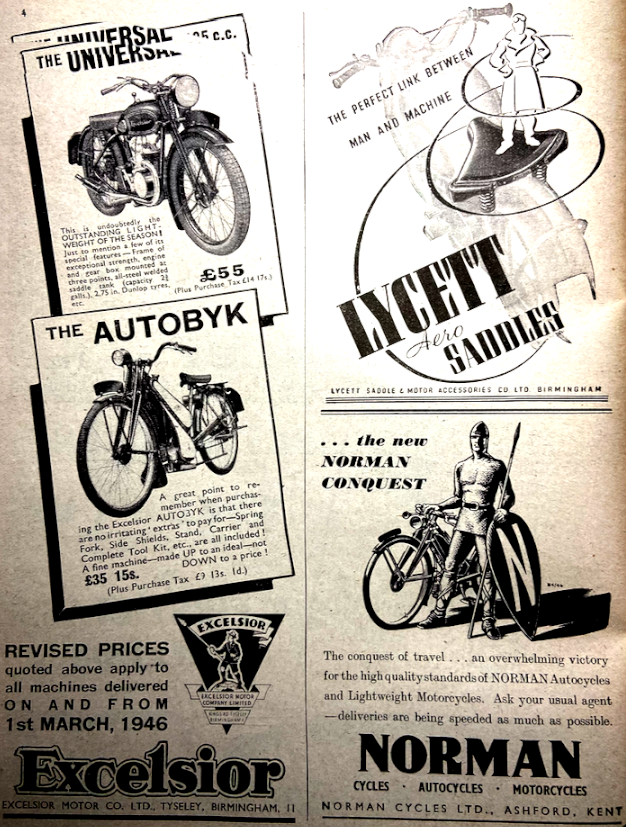

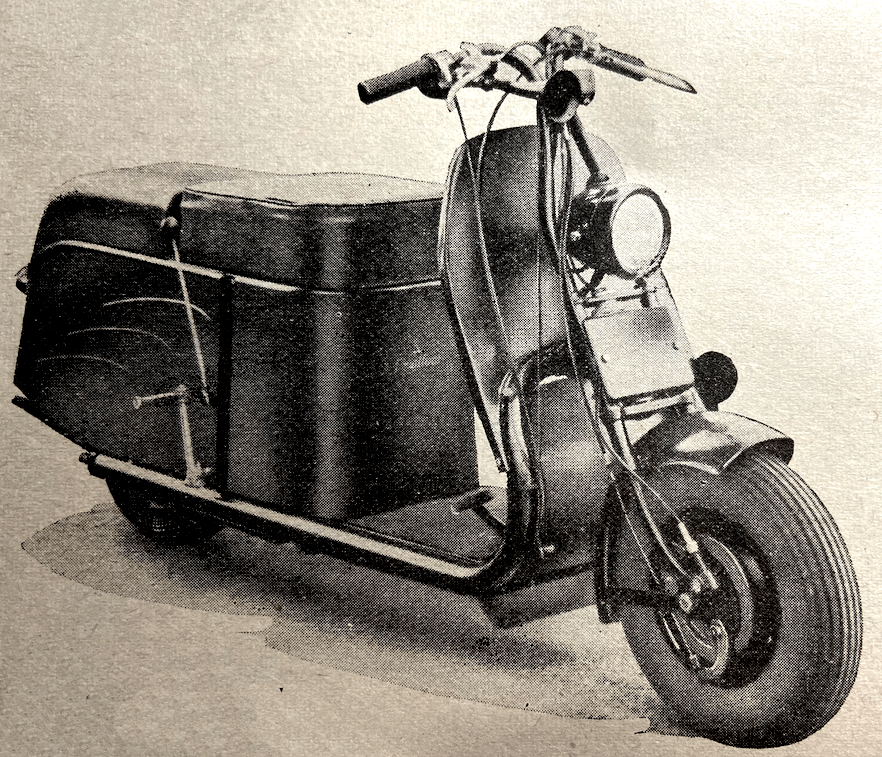

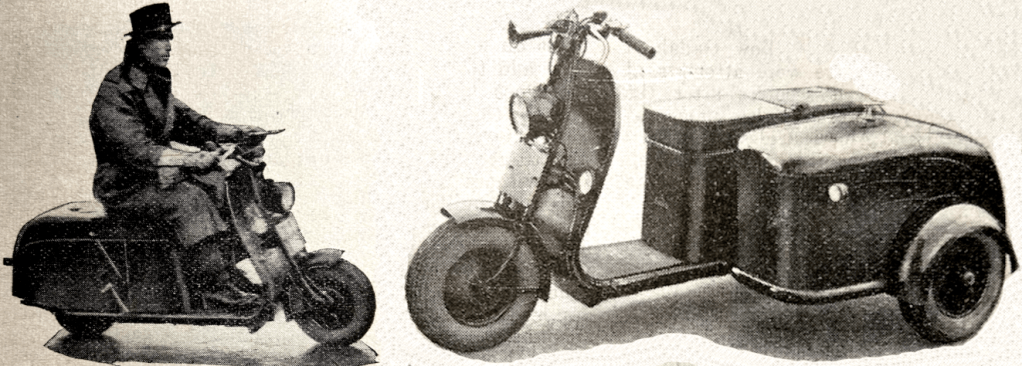

THE NORMAN RANGE, launched in Ashford, Kent, used Villiers power; also new was the Swallow Gadabout scooter, with 4.00×18 tyes, made by Heliwells of Walsall, West Midlands.

IN THE US THE MONROE Auto Equipment Company was offering hydraulically damped telescopic forks; between them Indian and Harley Davidson snapped up the factory’s entire output.

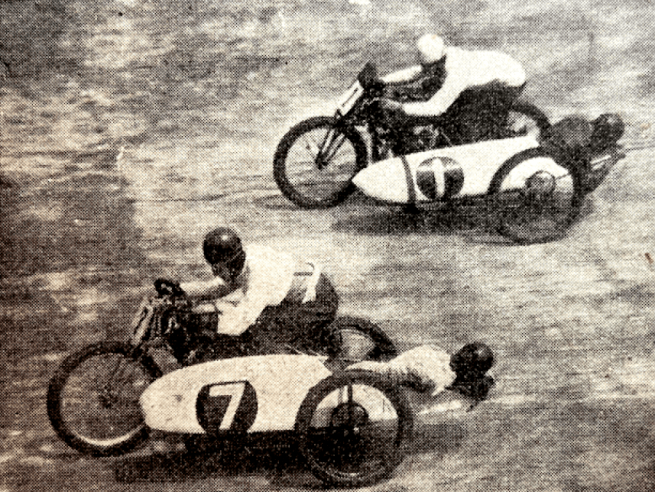

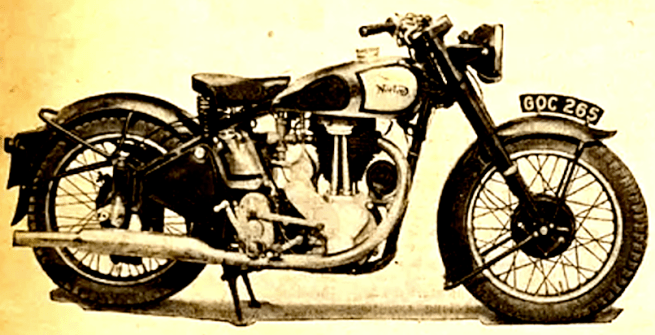

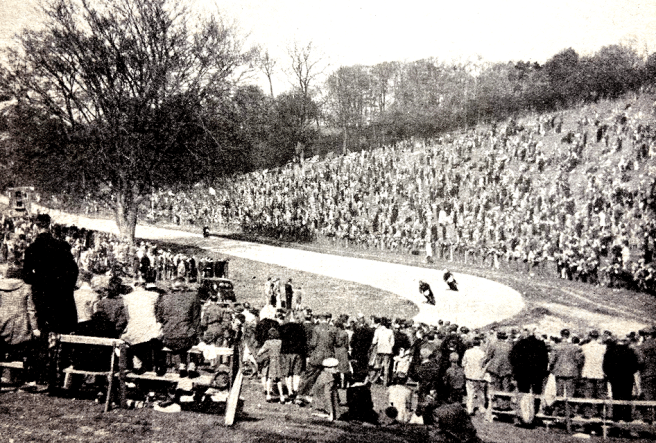

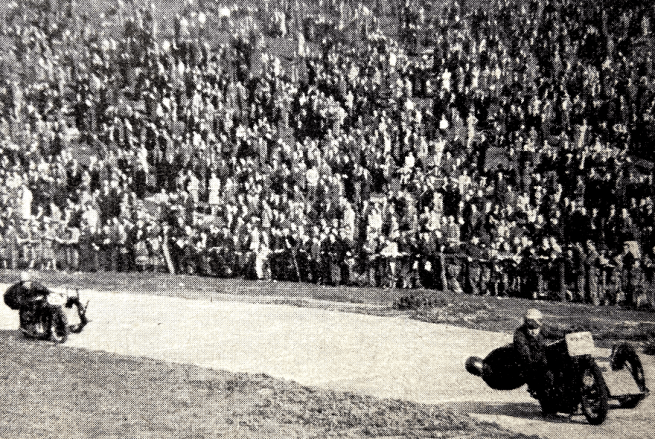

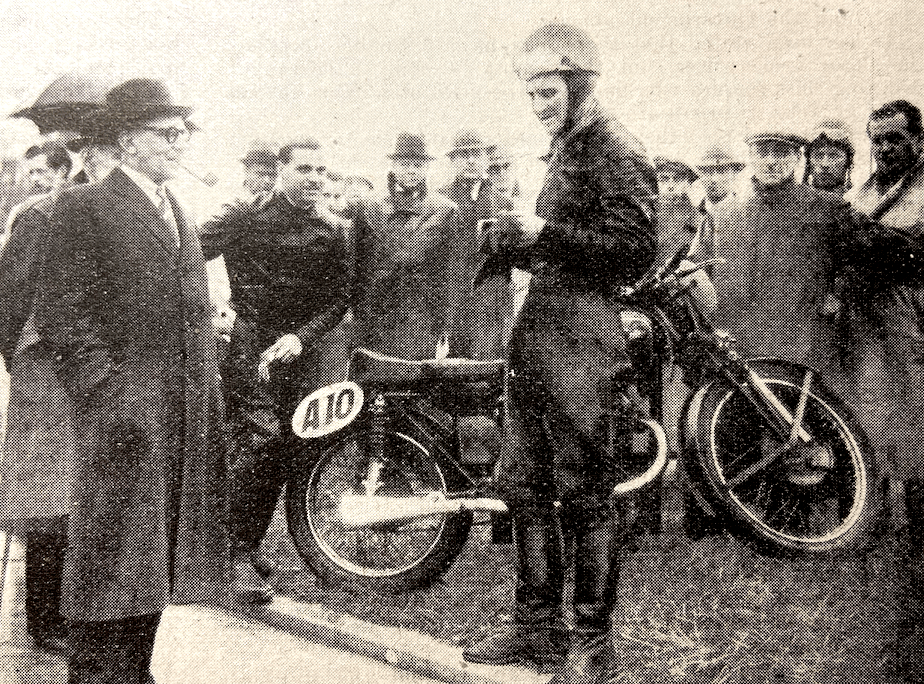

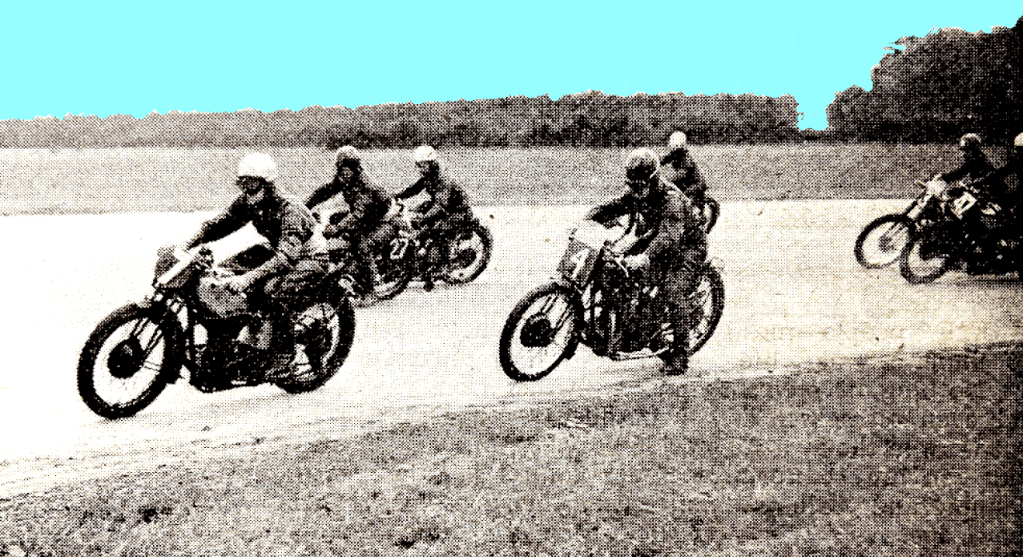

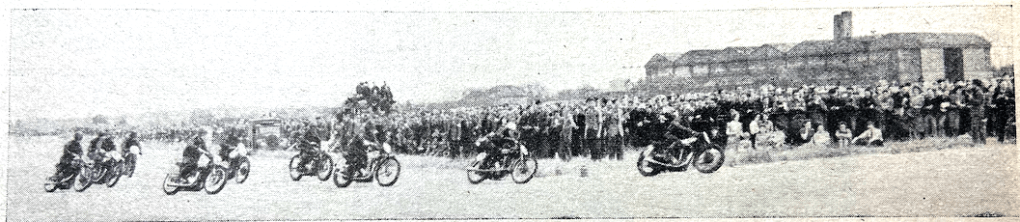

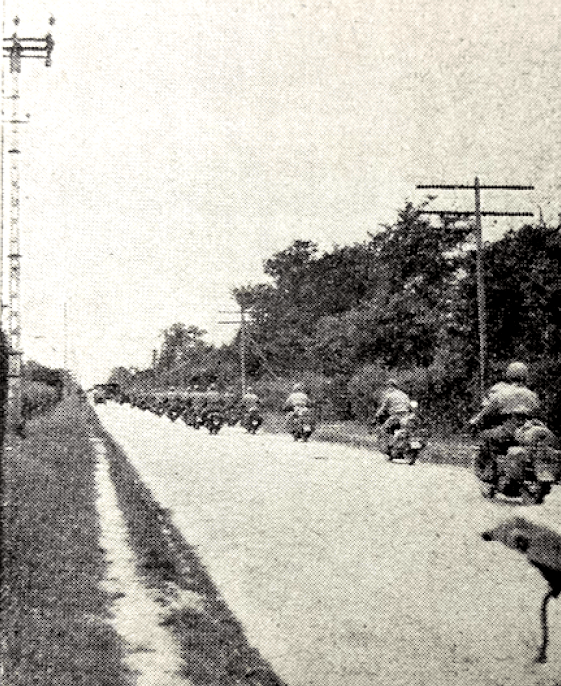

BRANDS HATCH, STILL A grass track venue, hosted an Anglo-Irish match courtesy of the Bermondsey MCC. England’s honour was upheld by the likes of Eric Oliver and Jock West; Irish stars included Ernie Lyons, Artie Bell and Rex McCandless, who was using the swinging-arm frame he’d designed with his brother Cromie. The English scraped a 19-17 victory but the McCandless frame would win renown as the Norton Featherbed.

“THE BOARD OF TRADE are to issue ten additional clothing coupons to a wide range of manual workers in industry and agriculture. How about the motor cyclist with his often worn-out riding kit? Isn’t it time he was favoured with a few extra coupons? After all, motor cycles—and motor cycle kit—are necessities to many essential workers in the country.”

“‘WE HAD OUR FIRST SIGHT of a real post-war motor cycle at the Leinster trial, when Cromie McCandless turned up on a 350 Triumph Twin, complete with hydraulic plunger forks,'” reports the Dublin &DMCC.”

“SHOULD LADIES BE ALLOWED to join the Motor Cycling Club? You may say, ‘Why bring up that old, old question—hasn’t it been discussed time and again and the answer been, “No”?’ The fact is that the matter is to be debated again. Mr FG Eckett has put forward the motion that the ban the Club placed on ladies in 1918 be rescinded and a decision, one way or the other, will be reached at the MCC’s annual general meeting at the RAC next Saturday. Many, I believe, feel that, especially after their work in the war, ladies should very definitely be admitted. Other matters on the. agenda are two recommendations—one that the MCC should affiliate to the ACU in these days when the great need in the sport is unity, and the other that it should become an RAC associate club.”

“FOR A TRUE ASSESSMENT of the importance of the decisions reached by the Motor Cycling Club last Saturday it is necessary to know a little of the Club’s history. The MCC, as it is generally termed, was founded in 1901. Even to-day, with its activities curbed by petrol restrictions, it has over 1,000 members. Thus, in addition to being one of the oldest clubs—if not the oldest—in the country, it is among the largest purely sporting car and motor cycle clubs. To the public at large its fame comes from the big Bank Holiday week-end events, the London-Exeter, London-Land’s End and London-Edinburgh trials. Being older than the Auto Cycle Union, which was founded as the Auto Cycle Club in 1903, the MCC did not take kindly to the idea of being ‘governed’ by the ACU. For a period of nearly forty years there was antagonism, which at times flared up into open warfare, even to the extent of the MCC having a ban imposed on a London-Edinburgh Trial. At last Saturday’s meeting the seemingly impossible happened. The MCC decided—not by a snap vote but with the matter announced far and wide well in advance—that it will affiliate to the ACU. The decision was unanimous, and all that remains is to settle minor points. An obvious question is why has there been this remarkable change of front? The answer is simply that all thinking men and women connected with the sport know that it is imperative that all sections of it pull together. On this small crowded island the probable alternative is that there will be no motor cycle sport except that confined solely to private property. That the MCC, in spite of its strength and its 45 years’ history, is no slave to tradition is further emphasised by its decision to admit lady members to its trials. This ban has been in existence since 1918—well. over a quarter of a century. However, the really important matter is the lead the MCC has set the sport by deciding to affiliate with the ACU.

“THERE HAS BEEN TALK of electrically heated clothing, naturally so in view of its employment for flying. A question that has always worried me, however, is whether with our small dynamo outputs there was any hope of adequate heat. Already at night—which is generally when one wants the electrical heating most—the average dynamo set does not provide more than a sufficiency of amps for a good driving light. If we add current-consuming circuits in our garments…A friend who has been into the matter of electrically heated clothing points out that it is not necessary to provide heating elements which keep one hot, but merely to arrange that one does not get cold. He maintains that very few amps are needed for this.”

“WEST AFRICA HAS HAD its first scramble, thanks to that old-time TT rider, Tommy Spann—now Colonel Spann. There were 97 European and African entries from the Gold Coast, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and the Gambia. Primarily it was an Army event, but the Royal Navy and the Gold Coast Police entered two teams each. Four laps of a l¾-mile course were covered…An all-African team, Nigeria’s ‘B’ team, made the best team performance, while Gold Coast won the Inter-Colony aggregate shield. Best individual performance was made by Capt JW Nelson (Sierra Leone), while Lieut W Blake, RN (Sierra Leone) made best time in 11min 36sec. The best African performance was by Sgmn Jabita (Nigeria). When distributing the awards, Lt-Gen Brocas Burrows, C-in-C, West Africa, stated that the event would be held at least once a year and that French competitors intend to take part next time.”

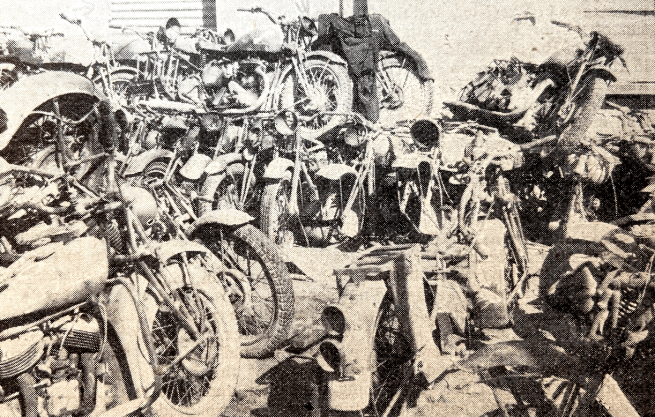

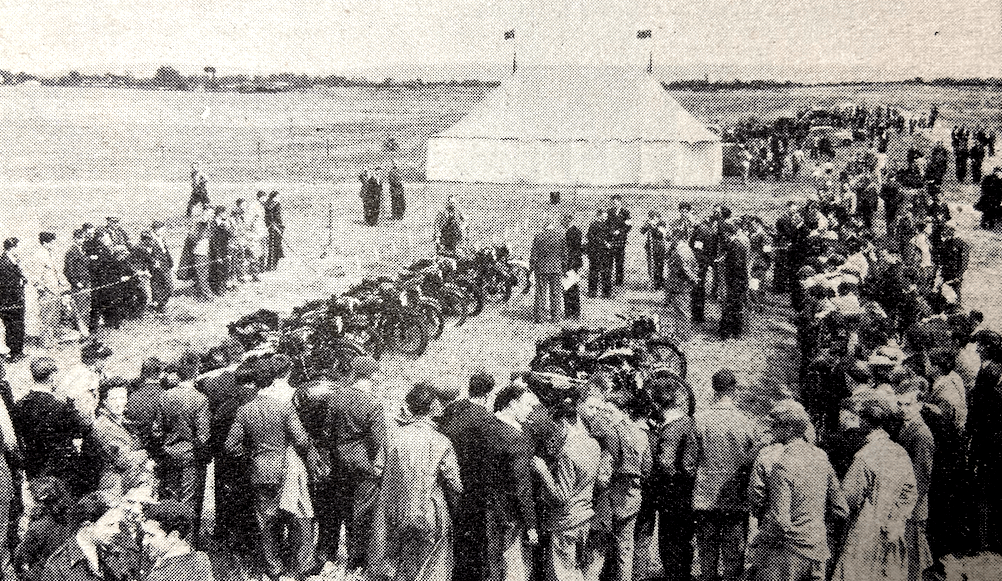

“THE SALE BY AUCTION of surplus vehicles at Great Missenden Depot, Bucks, which begins at 11am next Tuesday, is expected to last four weeks. Approximately 1,000 motor cycles are included in the 7,000 vehicles to be sold, but present indications are that the motor cycles will not come under the hammer until near the end of May or beginning of June; not, at all events, within the next fortnight.”

“CAIRO HAVE ASKED Mr C McEvoy to act as United Kingdom secretary of the famous Bar None MCC. Mr McEvoy (27, Kingsway, West Wickham, Kent) is endeavouring to contact old Bar None members now back in the UK, the idea being to hold an initial meeting as soon as possible. Among the proposals are a London area branch of the club. Possible clubrooms in the vicinity of Croydon have been found.”

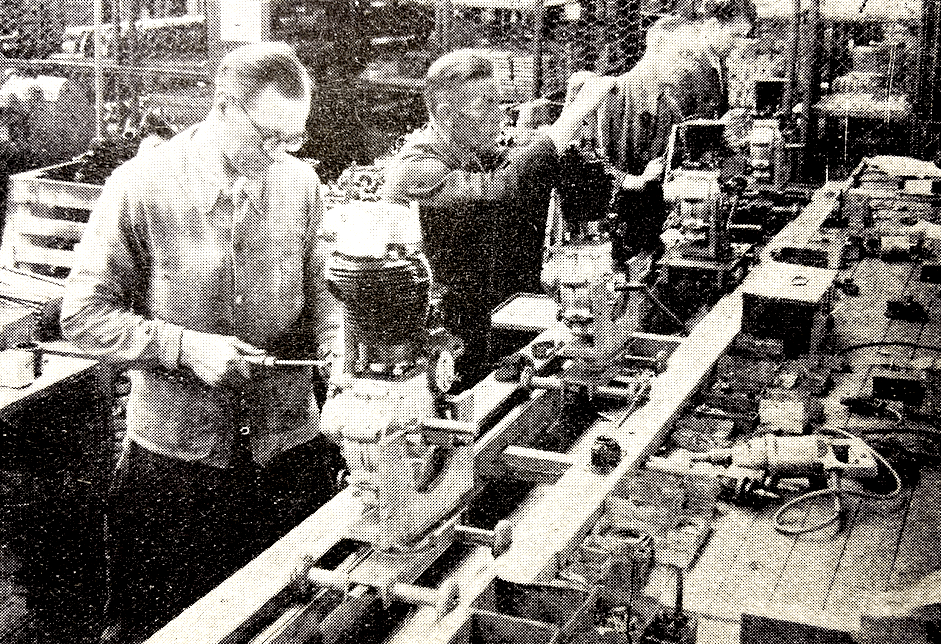

“COME HAIL, COME SNOW, come shine, the testing of experimental models goes on. You know as well as I do the hard weather we have had at times this winter, and how treacherous the roads have been. But during the whole of that time motor cycles have been out on experimental test covering their 200 and 25o miles in the day. A manufacturer remarked last week that even in the worst weather his man had been putting in 250 miles per day. Under good-weather conditions the mileage is around 300. It is extraordinary when you think of a normal working day as opposed to the very long day you and I normally make of it when we cover a big mileage. Three hundred miles a day, over 1,500 a week, 75,000 or more miles a year…”

CARS, HOUSES, AIRCRAFT—no matter what the amenity of life, excepting possibly in the realm of pure sport, the aim is to provide the maximum in comfort and convenience. Such is the age-old trend, and it is to be seen in motor cycles even as in the examples just cited. To-day motor cyclists are finding new front forks which call for no attention at all, not even lubrication, new brakes with click-type adjusters that can be operated in a moment, automatic ignition controls which vary the ignition timing as efficiently as, if not more efficiently than, the most expert can handle the old type of lever. The list can be lengthy, but it is questionable whether there is still sufficient realization by designers that motor cycles are not solely vehicles used for sport and that ownership is not merely the prerogative of the athletic youth in his late teens or early twenties. In these days a large proportion of motor cycles are owned by the middle-aged and others who seek a pleasurable form of transport within their means. The field of ownership has broadened considerably. Whether this is but a passing phase depends upon the industry; it depends upon whether manufacturers study convenience in use in all its aspects. Apart from producing motor cycles which will cover large mileages without calling for maintenance, providing accessible oil fillers, making engines quiet mechanically and as to their exhaust—directions in which big strides have been made—there are such matters as weatherproofing and easily operated stands. Can any motor cycle be termed modern which cannot be parked without effort and be counted upon not to fall over? And how is it that machines which are designed as runabouts are provided merely with narrow ineffective mudguards? It is high time that such machines were offered with efficient leg-shields that look part of the design. It is time, too, that there was a little research in the matter of mudguards which are eyeable yet efficient. If motor cycles are to make a long-term appeal to the many, less dressing-up by the rider is essential.”

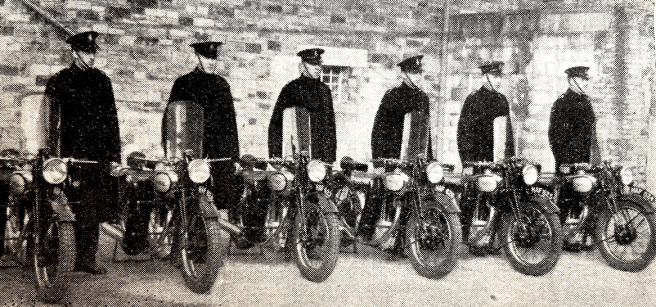

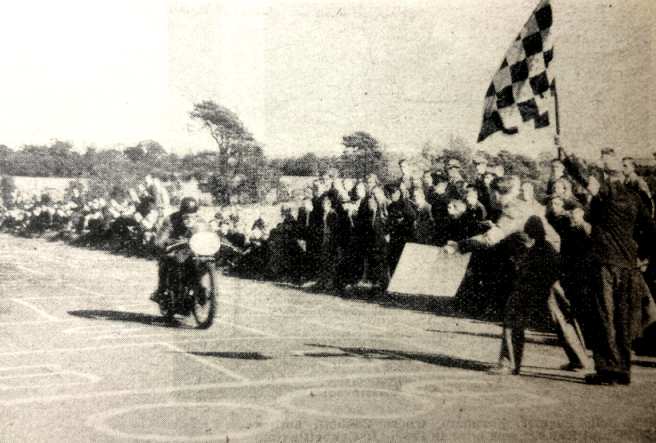

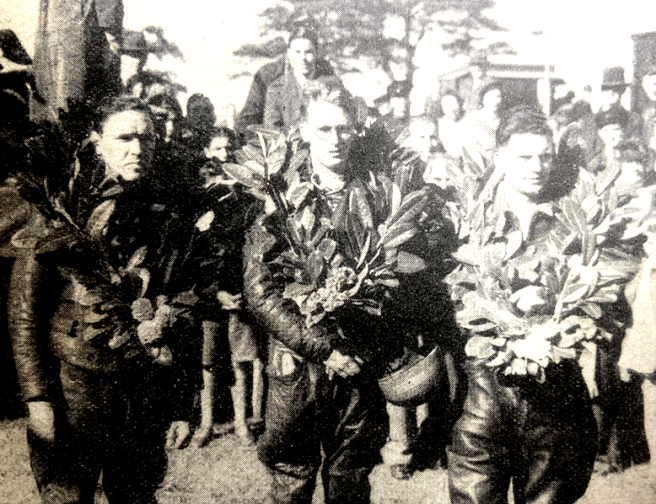

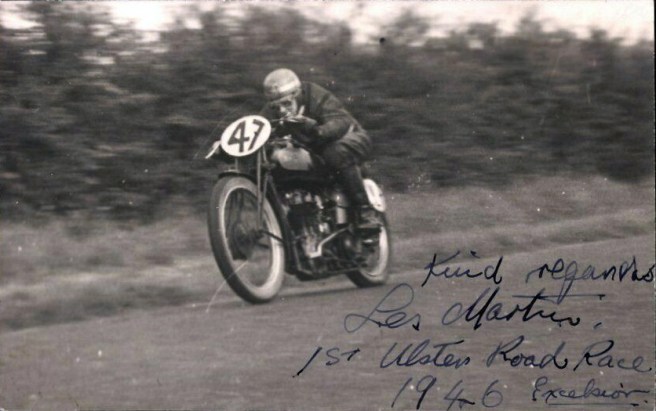

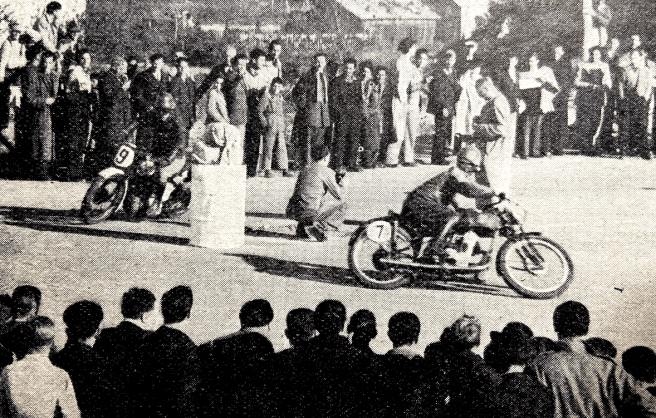

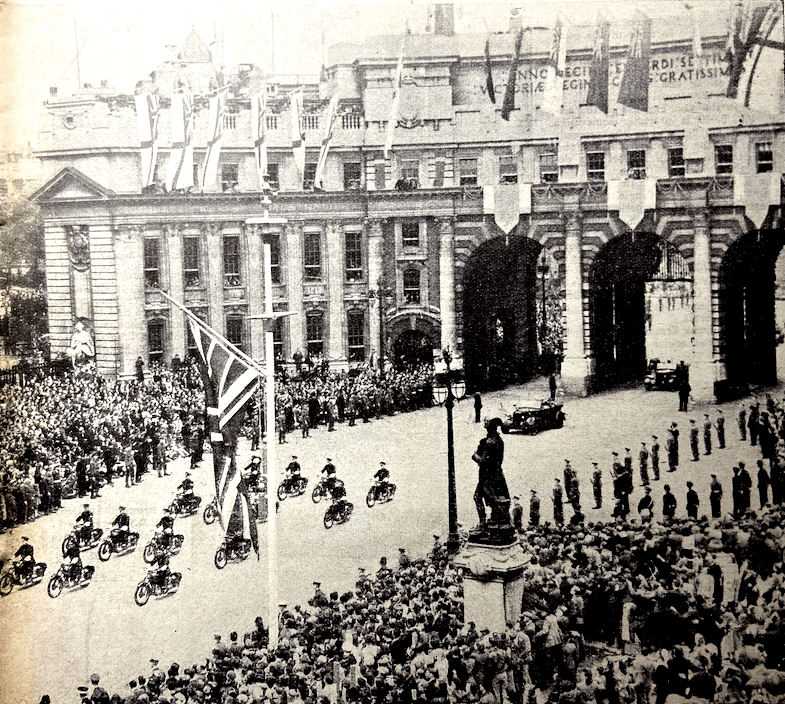

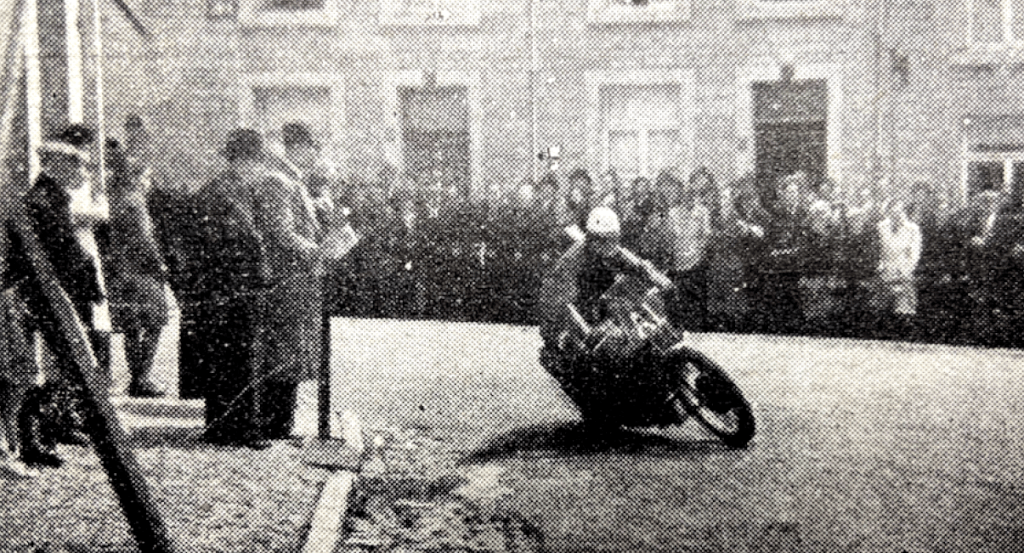

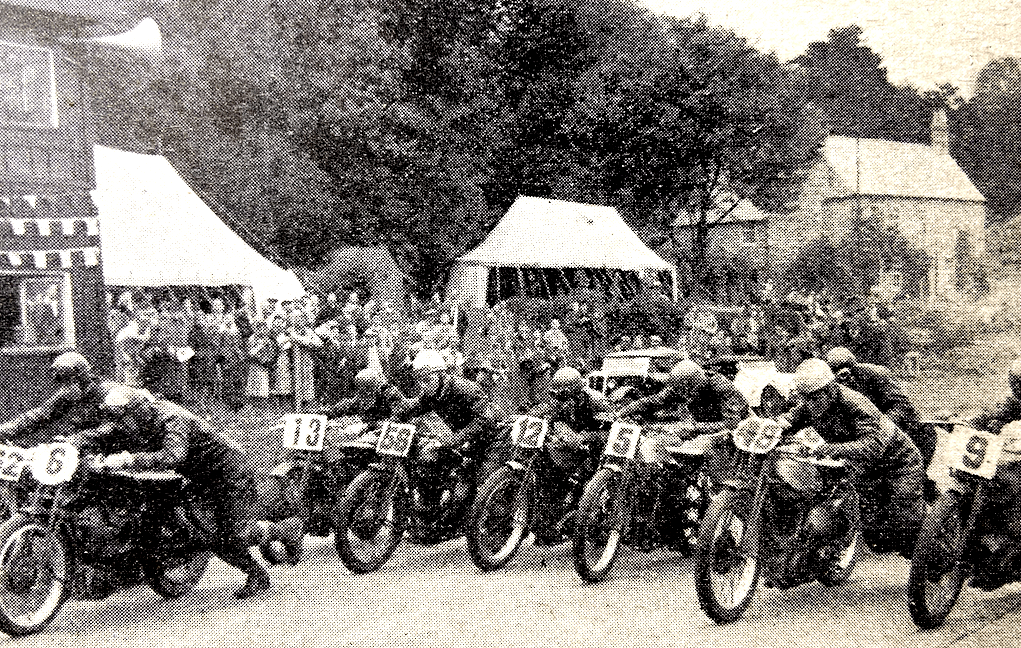

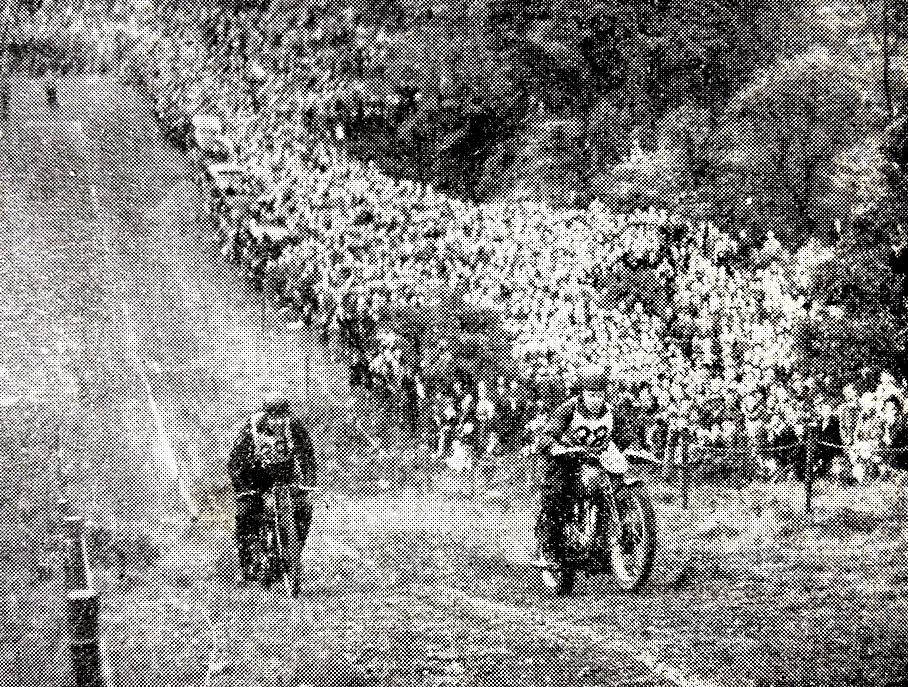

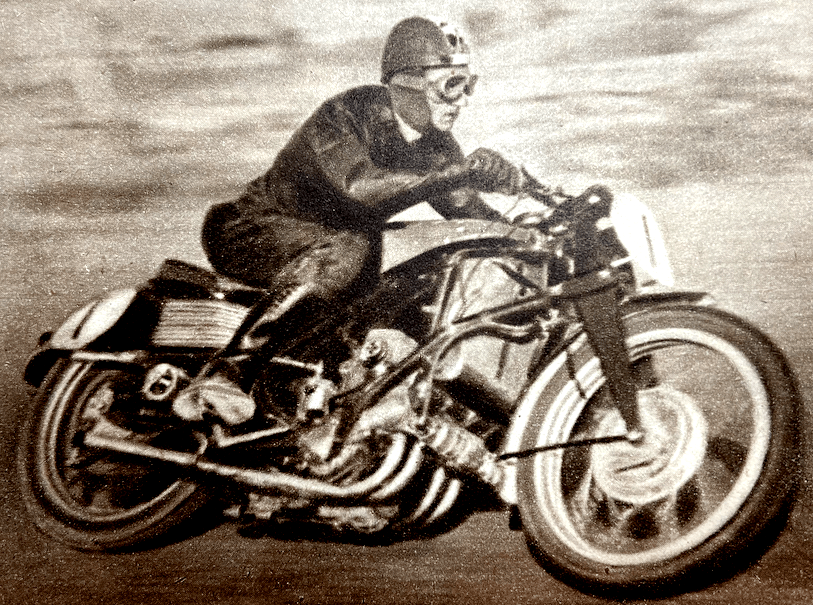

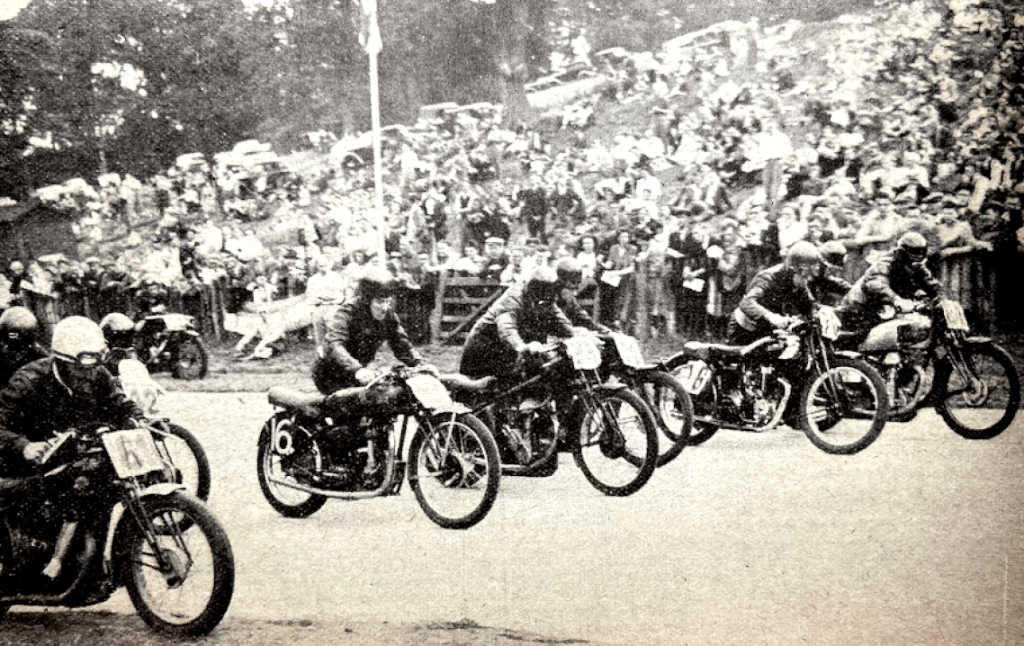

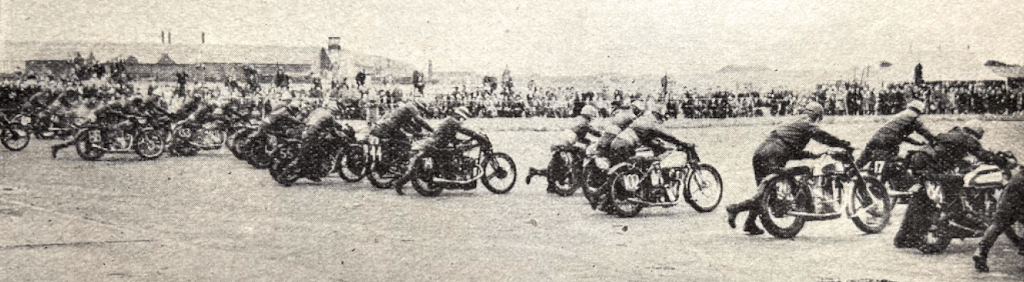

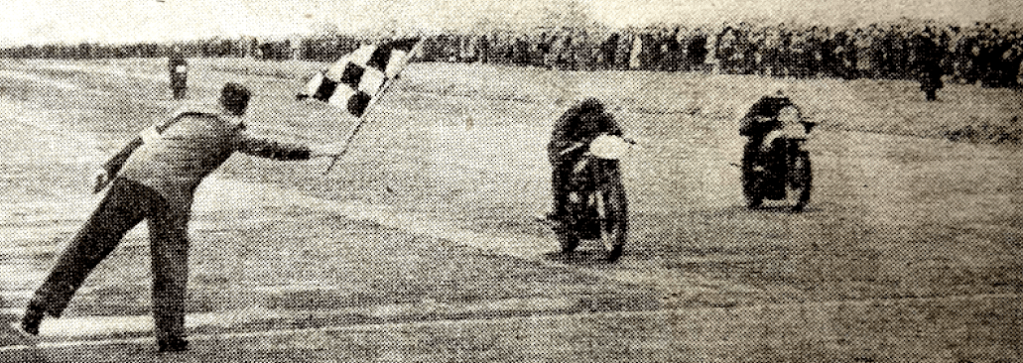

“AFTER A LAPSE of seven years, the Ulster MCC staged its famous road race over the Clady circuit last Saturday. The race had a different name and a different course, but there was enough of the former Grand Prix spirit in the air to suggest that probably by next year the event will regain all its past glories. The new circuit turns to the right at Nutt’s Corner on the straight between Ballyhill and Thorn Cottage and leads up to Muckamore by way of Tully and Killead Bridge. From Muckamore the seven-mile straight to Clady Corner, one mile from the start, is included. The resulting 16½-mile circuit was thought to be as fast as the 20½-mile circuit used for the Grand Prix which in 1939 was lapped at over 100mph. But practising indicated that the halving of the fast straight from the start at Carnaughlis to Thorn Cottage, by the turn at Nutt’s Corner, and the comparative acuteness of the many bends in the Tully, Killead and Rectory area had resulted in the new circuit being appreciably slower than the Grand Prix circuit. Even if an entry of the calibre usual in pre-war days had been competing, it seems doubtful whether a ‘century’ lap would have been reached. Saturday’s race was notable for the retirement of all competitors except one in the 500cc class, and for the excellent riding of VH Willoughby, who won the 350cc class at a higher speed than the

winner of the larger class and who also won the Governor’s Trophy for best performance on handicap. In the 250cc class, LC Martin, from the Isle of Man, repeated his 1939 win in this class. Crowds of spectators lined the course well before the start at 3pm. At mid-day there was a slight shower of rain though not enough to make the roads wet. Nevertheless, billowing clouds moved malevolently across the sky, blotting out the sun and promising rain for the race. By 2pm the sun peeped between the clouds occasionally and raised hopes that the threatened wetness would keep away. Keep away it did, and by late afternoon, when all racing was finished, the sun shone from a clear sky. After the Governor, HE the Earl of Granville, had chatted to riders, the hushed tenseness could almost be felt as the minutes ticked towards 3pm—a hush interrupted only by riders as they made certain bottom gears were engaged and carburettors were flooded. Zoom went the maroon and, after a short patter of boots, the 500s screamed away. One minute later, the 350cc class pushed off, and, after a further minute, the 250s started. As the sound of the last machine died in the distance, a flag-draped Norton, No 50, ‘entered’ by the Ulster MCC, was wheeled slowly past the start in memory of notable motor cyclists who had died on war service. THE 500cc RACE: 13 riders faced the starter, with R McCandless (Triumph), AJ Bell (Norton) and RT Hill. (BSA) in the front row. Hill’s engine fired instantly, and he shot away about two yards ahead of Bell and RLGraham (Norton). The rest went off in a screaming bunch, except J Hayes, who had to push some 50 yards before his Rudge finally got going. Within five minutes came news that RL Graham led from Bell. But at the end of the lap, Bell, riding to expected form, had passed Graham and was a couple of yards ahead. Bell’s time for the standing start lap was 11min 30sec (86.13mph), which promised well, and Graham was announced as

taking one second longer. Well over a quarter of a mile behind came JW Beevers (Norton) and Hill, separated by about 100 yards; then followed S Dalzell (Norton), Hayes, who had made remarkably good time after his tardy start, and R McCandless on his much-modified Triumph. Already retirements—which were to be the curse of this race—had started. S Brand (Triumph) was out within 10 miles due to a seized engine—poor recompense for spending the previous night fitting a replacement cylinder block. E Lyons took his Triumph into the pits after a slowish first lap to fit harder plugs and to make carburettor adjustments. His new Triumph, received less than 24 hours before the race, was fitted with the experimental Triumph spring hub and was on ‘Pool’ petrol. ‘Where are all the 500s,’ everyone asked as Bell streaked through to start his third lap—he was out by himself, which meant that RL Graham had been delayed. Something like two minutes elapsed, during which Willoughby, leading the 350s, passed and faded into the distance before Hayes and RL Graham came through in quick succession. As the hubbub of inquiring excitement mounted the loud-speakers blared, ‘Marshals—stop No 11—he has shed a piece of tyre tread.’ And No 11 was Bell! He was flagged off and forced to retire with only the minor mitigation that his second lap in 11min 9sec (88.84mph) was a record which remained unbeaten during the afternoon. By half-distance, RL Graham had retired, and only six riders were still going strong. Dalzell now led Hayes, and well behind came BM Graham (Norton)—far away were JJ McGovern (Norton) and B Meli (BMW). Hayes dropped out of the running with a flat rear tyre, which left BM Graham second some 3min behind Dalzell. These two were the only riders left in the race with any chance of finishing officially. But no; Dalzell was not to finish—on his last lap he retired with, it was said, a seized engine. THE 350cc RACE: As the sound of the 500s mellowed in the distance, 15 riders in the Junior race pushed off. Though not in the front row on the grid, RA Mead (Velocette) got the best of the start by about 10 yards from TH Turner (Norton) and FJA Nash, who was riding his streamlined Velocette. But it was not long before VH Willoughby (Velocette) had overhauled those who got the beat at the start. He led by 24sec at the end of Lap 1, and in the process of a standing start lap at almost 84mph he had passed many of the larger machines which went off one minute ahead. Second was Mead, and third Nash, followed closely by WS Humphry (Norton), R Lee (Velocette) and TF Tindle (Velocette). Humphry displaced Nash in third place on the second lap, and Lee also overtook the streamlined Velocette. JG Dixon (Norton), a local rider, retired with engine trouble. Meanwhile Willoughby, riding his very quick Velocette in extremely good style (Stanley Woods said so!) and lapping at well over 85mph, was out by himself and, indeed, had disposed of all the 500s to lead the entire field. At three laps he had almost 3min over the leader in the bigger class; and on the next lap, Mead followed Willoughby’s example. In the pits and changing a plug was TH Turner; and also there, but retired from the race, was H Taggart (Velocette). After holding eighth place on the second and third laps, R Armstrong (Norton) toured in to retire. Engine trouble at Tully was reported to have stopped Tindle. Willoughby was going faster and faster. At five laps his average speed was 85.96mph, and his fifth lap speed was 86.89mph—his fastest up to that time. Three minutes behind came Humphry, who had just caught Mead, and both were lapping at rather more than 82mph. Lee was fourth. Nash was fifth, and F Rogers (Velocette) and J Williamson (Norton) were close. Lee passed Mead, who had slowed appreciably, and took third place. Willoughby was still drawing ahead, and one lap from the finish had nearly 4min in hand over Humphry. As five minutes after the first man had crossed the line other competitors would be flagged off, it looked as if there might be no official placemen. With a time of 11min 21sec (87.27mph), Willoughby made his sixth the fastest lap of the race, and his last lap took only 1sec longer. Humphry came home second, and Lee third. Mead, Nash, Rodgers and Williamson followed. THE 250cc RACE: From his front row position, LG Martin (Excelsior) immediately took the lead a few yards in front of H. Hartley (Rudge), G. Dummigan (Rudge) and WM Webster (Excelsior). Long after the field had

disappeared, W George (Excelsior) was still at the start changing a sparking plug. He got away eventually, but his engine sounded none too healthy. In what seemed to be quick time, but which was in fact 13min 37sec, Martin came through with one lap completed and a 16sec lead over Hartley. C Astbury on his MD Special—mainly New Imperial—was third. Dummigan was fourth, Webster fifth, and JA Dickson (Excelsior) sixth, the last three in very close company. On his second lap (which at 75.61mph was the fastest of the race) Martin had increased his advantage over Hartley to nearly a minute, and Astbury remained third. Dummigan, Webster and Dickson, in that order, were so close together that the order was of no importance. Actually Dummigan led the trio at three laps, and then Dickson was in front on the fourth lap. By then Webster had lost about 200yd, and the scrap ended with the retirement of Dummigan, who was reported to have fallen at Tully. On the fourth lap, too, Astbury stopped near Tully with what was probably a holed piston, and Dickson became third. Martin, Hartley and Dickson remained in that order till the end. Though continuing to slow, Webster finally finished fourth. RESULTS. 500cc Race—8 laps (132 miles): 1, BM Graham (Norton), 75.33mph; fastest lap, AJ Bell (Norton), 88.84mph. 350cc Race—7 laps (115½ miles): 1, VH Willoughby (Velocette), 86.32mph; 2, WS Humphry (Norton); 3, R Lee (Velocette); 4, RA Mead (Velocette); 5, FJA Nash (Velocette); 6, F Rodgers (Velocette); 7, J Williamson (Norton); fastest lap, VH Willoughby, 11min 21sec (87.27mph). 250cc Race—7 laps (115½ miles): 1, LG Martin (Excelsior), 74.71mph; 2, H Hartley (Rudge), 71.64mph, 3, JA Dickson (Excelsior), 67.91mph; 4, WM Webster (Excelsior) 66.31mph; Fastest lap, LG Martin, 13min 6sec (75 61mph). Ulster MCC War Memorial Trophy (best performance by a novice rider): F Rodgers (Velocette). The Wilson Trophy (best Ulster MCC member): FJA Nash (348cc Velocette).”

“WE MOTOR CYCLISTS are commonly supposed to be somewhat solitary and individualistic. Yet what do we find in the South Eastern Centre? Its small though populous territory now contains not far short of 65 separate clubs, all of which despite the heritages of war are at this moment alive and kicking strongly. Nowhere in the whole world has there ever been such a happy, intelligent and vigorous organization of so many motorists in so small a space. Organization of car owners is weak and pallid by comparison. Hats off to the men who run the SEC.”—Ixion.

“A MOTOR CYCLIST accused of dangerous driving was stated to have said when stopped, ‘That’s how I was taught to drive in the Army.’ He was fined £10 at West Ham court.”

“LOSING ONLY FOUR POINTS out of a possible 120, Sgt Syd Hufton gained the Middle East reliability championship title at the Services Bar None MCC reliability trials. This event was held on the desert at Abbassia, near Cairo. Although the course was not one of the toughest, perhaps, the 12 observed sections included some typical rough country stuff—rocky gullies, steep soft sandy inclines, and real snorting hairpins. Hufton lost his points for footing when turning a sharp hairpin bend on to a loose rocky incline of about one in two. The field of about 70 experienced Army riders included men from the 6th Airborne Division now in Palestine, the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy.

“THE TWO DUTCH TEAMS which are to compete in the Newcastle &DMC’s Travers Trial will be mounted on two Triumphs, two Velocettes, an Eysink and a BMW sidecar.”

“ONE MP’S OPINION of the new Highway Code: ‘It is quite obvious that this pamphlet has been written by a rather intelligent office boy in a kind of language with which he is not quite familiar.’ In point of fact, the new Code is a workmanlike document, though the English could be tightened up here and there. A Welsh MP has asked for a Welsh edition of the Highway Code. He states, quite accurately, that many Welsh people do not understand English.”

“DISMANTLED PLANT will soon he coming from German factories to Britain. The procedure for disposing of this German reparations plant will normally follow the lines of the existing Government surplus disposal schemes.”

“TWENTY-SEVEN BOMBED SITES in Westminster, capable of accommodating more than 1,000 vehicles, are to be requisitioned by the MoT so that Westminster City Council can quickly turn them into temporary parking places.”

“IF RUBBLE IS DEPOSITED on a public highway it is a legal requirement that the use of the highway by the public should be safeguarded. Ordinarily this requires the provision of lights at night.”

“MISS PHYL COOPER, of the London Ladies’ Club, was recently mentioned in despatches. She went into a minefield and rescued a badly injured man. She was in Austria.”

“A KENT PARISH COUNCIL has decided to ask the local Chief Constable to replace the village policeman’s motor cycle with a pedal-cycle. The chairman of the council thought that a burglar would lie low if he heard a motor cycle approaching. The constable, according to report, has other ideas—he wants to keep his machine.”

“SCORES AND SCORES of lads back in Civvy Street from the Forces are finding that owing to the paper rationing they cannot get their copy of The Motor Cycle even now that they are back home. We are receiving letter after letter from such lads begging us to help. Until the paper ration increases it is, of course, quite impossible for us to help except with your help. Will you act the good Samaritan—will you do a real good turn by letting one of these lads have your weekly copy after you have read it? Just as with our Servicemen’s scheme, all you have to do is to drop me a postcard at Dorset House, giving your name and address and saying ‘I will’, and, after we have given you the address of a lad, put wrappers round the copies and post them off. The postage on a single copy open at the ends is 1d.”

“MR EDWARD TURNER, of Triumphs, considers that Great Britain manufactures a good 75% of the world output of motor cycles, now that France and Germany are no longer grinding out motor-assisted bicycles by the tens of thousands. Oddly enough, we are the biggest consumers (in a good sense), as well as the biggest producers. Still more interesting is the fact that of Britain’s exports few are intrinsically so beneficial to the nation as motor cycles. The ideal export is one which brings in the largest amount of cash for the smallest loss of raw materials. A small car brings in as 7d per lb of raw material. A motor bicycle brings in 5s 5d per lb of raw material. Naturally we are making hay while the sun shines, but a day is not far distant when all our motor exports will show marked shrinkage. These foreign markets are not insatiable. I wonder how home prices will fare when the brakes go on to exports?”—Ixion

“TWO HARROW BOYS pleaded guilty at Missenden (Bucks) court to stealing £10 of motor cycle parts from the surplus dump at Great Missenden. The cases were dismissed under the Probation of Offenders Act.”

“MR SHINWELL (MINISTER OF FUEL) said recently that the only forged petrol coupons in circulation were basic coupons, and the number was insignificant. During a forged coupon case at Hove, it was stated that a large number of forged petrol coupons were circulating. Asked whether he could improve the petrol ration, Mr Shinwell said: ‘With the greatest of pleasure, if circumstances justify it.'”

“A READER SENDS us an extract from a letter received from his brother in Burma: ‘Mother sent me The Motor Cycle in her parcel, and after I finished reading it I laid it on my bed and went to tea. On return, I found four or five Japs all reading it, and, by the excited chattering, I imagined they were very interested!’ The Japs were working on the Burma to Siam railway.”

“WHEN A MOTOR CYCLIST was fined £1 at a London court for riding a machine in a dangerous condition, a police officer stated that the clutch cable was broken and one end was held by a pillion passenger. When the rider wanted to change gear he shouted to the passenger. The Clerk: ‘Quite a Heath Robinson affair.'”