“AFTER YEARS OF drab khaki it seems strange indeed to see a line of brand-new motor cycles finished in chromium and colour—more than strange, highly encouraging. Today there are various colourful new mounts. They are the prototypes of the models which their sponsors hope to set about producing just as soon as the war ends and controls permit. In some cases the machines may be (and are) merely mock-ups—that is, their beauty is little more than skin deep, for instead of being complete motor cycles they have been schemed and fashioned solely for the factory executives to decide whether they approve the proposed external appearance. Some of the schemes we have seen strike us as colourful, to say the least. Possibly it is that, after all the khaki and now rather bedraggled civilian models, such machines, bright and spotless, come as something of a shock. Maybe we would feel similarly if it were possible to put back the clock and step into the last Earls Court Show, that of November, 1938. We raise the matter now because design, appearance—everything—is still open to discussion. It is usual for a pendulum to swing: do motor cyclists want to go from khaki to the other extreme? We fully agree that it will be joy to have civilian-type finishes again, and that pride of possession is praiseworthy and should be satisfied, but we sincerely hope that the pendulum will not swing to such an extent that the finishes will be—to use motor cyclists’ customary term—’Promenade Percy’. Let there be smart, attractive finishes. Not least, let them be really durable. ‘British is best’ must be no catch-phrase after this war, but the simple truth resulting from inbuilt excellence, not mere flashiness.”—Ixion

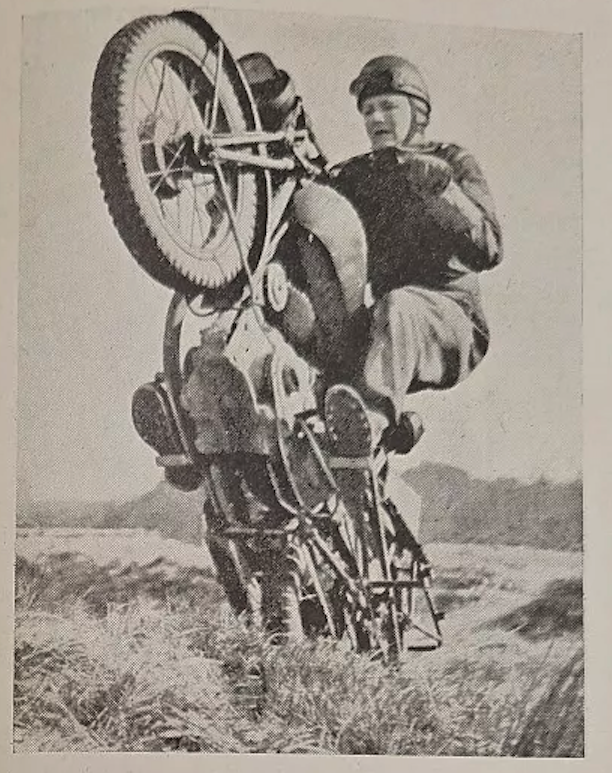

“I WAS VERY INTERESTED in Torrens’ remarks about riding through gales because during the war I have had the opportunity of riding various Service machines over some of the most northerly of the British Isles, where the wind blows like a thousand devils and shelter is rare. Most of this riding has been done away from the excellent main roads and has been confined to rough hill tracks and peat roads. Under these conditions the technique in a really strong wind appears to be to, go as slowly as possible, and to keep fighting the front wheel over to the windward side of the track, so allowing plenty of room for recovery after the gusts. It is fatal to open up, for one very soon finds oneself exploring the neighbouring countryside. A stern gale is quite exhilarating, but plenty of time has to be allowed for braking. On the other hand, a head wind can be quite a struggle, and many a time I have had to go down into bottom gear to force the machine downhill or round an exposed bend. Probably the most trying manoeuvres are (a) riding on slime with a fierce and gusty cross wind, and (b) negotiating a sharp hairpin of loose stuff with a gale following one into the bend—getting round and back into the wind is a considerable feat of balance. One afternoon a couple of Winters ago the local met office recorded 95mph steady, with gusts of over 100. During the short time that this lasted I took out a Service 350 to climb a winding track up a nearby hill—just to see what it felt like. The gale was blowing into the face of the hill, and at one place the track curved round through an 18in cutting. It was here that the wind took me sideways into the bank and I stalled the engine. No room to turn; and every time I stood on one leg to attempt a restart, over we went. It was difficult to hold the machine, up even with both feet braced against the foot of the bank. What should I do? It took 20 minutes of furious wrestling to get on the move again. For several months 1 had the use of a 1929 Flying Squirrel, and it was a revelation on this rough going. The sliding front forks gave a fine long easy movement, and the way the back wheel stuck down to the road was almost uncanny. What a marked contrast to the back wheel hammer of the Service machines!

BG Wilkinson, Knaresborough.”

“WE HAVE READ with great interest ‘Don R DGW’s’ letter dealing with the foot-change versus hand-change controversy and can say from experience that we are wholeheartedly in agreement with him. Conditions out here are far from ideal, with congested roads which, when free from traffic, have an abominable surface to contend with, due to the passage of many tracked vehicles, making use of the gearbox a very frequent procedure. Hand-changes just would not do when both hands are needed for control of the machine. Conditions also change very rapidly. When it is hot and dry, clouds of dust are thrown up by the myriads of transport, and when it rains the roads are a sea of liquid mud. Needless to say, these conditions are playing havoc with our machines, resulting in buckled wheels and fractured tyres. This could be eliminated by the fitting of a spring heel. Incidentally, most of us favour using motorcycles instead of jeeps for DRLS, as the use of the latter generally entails long delays in traffic columns, whereas the motorcycle can easily get by. We are fortunate enough to get Motor Cycling regularly each week, to the great enjoyment of all.

Sigmn GA Peters

Sigmn D Guidery.”

“NITOR HAS DESCRIBED a colonel who has made himself a marvellous pair of waterproof gloves. It is common knowledge in the services, especially out East, that in the early years of the war enormous wastage was experienced with every type of store…which deteriorated if it got damp…Two methods of protection were improvised by the chemists. One was a sort of waterproof cellulose fabric, the other an easily removable dope. The colonel’s experiment in glove-making with the former indicates great. possibilities for post-war motor cycling.—Ixion.

“FROM A SHORT biography of William Murdoch, the man who invented gas lighting and so paved the way to efficient street lighting [he also built a working model steam trike in 1784—Ed], we cull tho following gem. When interviewed for a job by Boulton, Murdoch accidentally dropped his top hat. It made a clatter on the floor. ‘Very odd,’ said Boulton, and Murdoch had to explain that it was made of whitewood end had been turned out on a lathe!”

“THE MIDDLESBROUGH MCC discussion on motor cycling for Everyman missed a point of importance. They were informed by their speaker—with perfect truth—that the average 1939 artisan family disposed of no great surplus. An expenditure of £14 per annum on the instalment system was all it could normally manage for a piano, bicycle, or other not-wholly-indispensable article. Such figures place even a new autocycle outside the grasp of such a household. The inevitable deduction was that unless Britain attains a mighty leap in prosperity, no motor cycle can over belong to Mr Everyman. Yet the fact remains that before this war thousands of artisans owned motor cycles and some of them were not foremen or highly skilled craftsmen working at special pay rates.This puzzle is easily explained by two facts. First, many—probably most—of such machines were bought second-hand—and for £14 you could get an extremely usable bus of that class (I have known innumerable working men who paid no more than single-figure poundage.) Secondly, a good many more were purchased neither out of savings nor from income, bet with windfalls. Such a windfall may be a legacy, a price in a newspaper competition (crosswords, bullets, or what not), a bet, a good guess in a football pool, and so forth. It has always been obvious that an artisan working at low rates cannot afford to motor cycle, however regular his employment, except under the two special conditions outlined in this paragraph. For a steady and assured market in new machines the industry must seek higher up the wage scale.”—Ixion

GERMANY CEASED PRODUCTION of 750cc shaft-drive military BMWs and Zündapps to concentrate on 125 and 350cc DKWs.

THE UK PRODUCED more than 100 million gallons of benzole from coal.

THE USA REGISTERED 157,496 motorcycles. California led the way with 22,309; Nevada came last with 170.

UK ROAD ACCIDENT casualties soared, due mainly to the blackout, peaking at 4.1 deaths per 1,000.

PIAGGIO ENGINEERS RENZO SPOLTI and Vittorio Casini designed a motor cycle with bodywork fully enclosing the 98cc two-stroke engine and transmission and forming a tall splash guard at the front—along the lines of the Everyman concept developed by The Motor Cycle. The design included handlebar-mounted controls including a twistgrip-controlled gear change, forced air cooling and small (8in)-diameter wheels and a tall central to be straddled by the rider. Officially known as the MP5 (Moto Piaggio no 5), the prototype was nicknamed ‘Paperino’ (‘Donald Duck’).

“AMERICAN ADVICES REPORT the debut of a novel form of petrol gauge. It threatens to be a shade bulky for two-wheelers, but as it is to be marketed in combination with a standard speedometer, it may adorn the postwar Harleys and Indians. Electrically coupled to the speedometer, it is really a flowmeter, and registers the consumption continuously, as well as the amount of juice remaining in the tank. I dare not prophesy that it will be standardised on many motor cycles, but it will certainly enable owners to check their consumption pretty accurately. It claims to be correct to a limit of one drop per minute.”—Ixion

Here are some snippets fro the USA, courtesy of Motorcyclist magazine…

“SOMEWHERE IN THE PACIFIC—’Here’s the loot for my subscription. How about digging up some old pictures, etc and putting them in the magazine? I’m getting corny with those letters to the fellows from babes the majority of us only heard of. Besides you’re not indebted to Harley or Indian so why not get some good articles on British bikes. If anyone were to ask me, which they won’t, American companies will face stiff competition from the foreign makes after the war. . . . (censored.) After the smooth handling and acceleration of the British models, Triumph, especially, I’m sold. That Tiger 100 is a real sport machine. So help me, if you print this, I’ll wring your neck. My best pals used to be Indian and Harley riders and if they found out I turned traitor—well, just don’t print this with my names—(Name withheld by request.)”

“‘WATERLOO, IOWA—I am enclosing my renewal, and wish to extend my compliments on the splendid way you and the staff have carried on the magazine…This year numbers my 26th since I first threw a leg over a sputter-bike, but the acquaintances made with real old timers like JJ O’Connor through the pages of the Motorcyclist make me feel like I am still a youngster at the sport…Keep up the good work.’

Paul Brokaw, H-D Dealer.

In January 1943 Paul Brokaw as Secretary of the Black Hawk MC, Waterloo Iowa, sent in a story on the death of the five Sullivan brothers, all members of the Black Hawks, who were lost in the sinking of the USS Cruiser Juneau in waters off the Solomons. All members of the Black Hawks, including Paul Brokaw, subsequently entered some phase of military service. After a serious illness and a critical operation at Mayos, Paul is back on the job as Harley dealer in Waterloo. He writes, ‘I just pulled through my operation by the skin of my teeth. Hell is so full of Japs and Huns I guess there wasn’t any room for a minor sinner like myself.'”

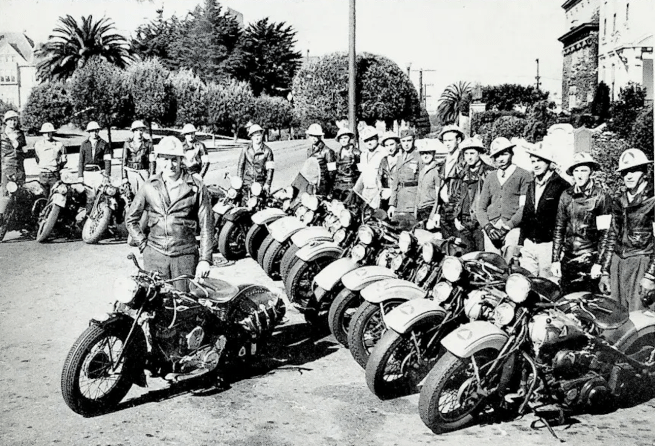

“BAY CITY MOTORCYCLE CLUB. San Francisco—There was fun aplenty on our club run to Stevens Creek. While enjoying ourselves at the inn there, a party of 15 members of the San Jose Dons happened along. They saw our bikes parked and stopped and joined us and added greatly to the merriment of the party. Sorry that rain prevented us accepting their warm invitation to visit them. Lots of old timer and ex-members whom we had not seen for a long time came out for the annual crab feed and cub pictures. Our members in the services, of whom we have addresses, all received holiday greeting cards, signed by our membership, to show that we have not forgotten our absent brothers. In these days of mechanic shortage we are lucky to be getting such fine service on our motors from ‘Dud’ Perkins shop…Lots of nice letters come in from our members in the service and we read them at the meetings and acknowledge them, telling the absent pals what the gang is doing.

Mary Binkley, Secretary.”

“TORRENS’ SUPERB ARTICLE on coil ignition deserves the closest attention from all readers who still nourish prejudices against the coil. Its tail contained a small sting worthy of extraction. He has converted more than one sulky starting motor cycle into a tickle-starter by substituting a racing type of magneto for the ordinary touring or roadster standard instrument. The additional cost will, of course, always remain fatal to the fitting of racing mags on standard machines sold under keen price competition. But the existence of this luxury is not as well known as it might be. Certain types of rider may be glad to know of its existence and to specify it on their post-war machines if—for irrelevant reasons—they refuse coil ignition. It is, so far as my experience goes, better than the ‘booster’ mags which a few of us used after the last war for similar reasons.”—Ixion

“IF NUMBERS OF DIFFERENT motor cycles ridden were a true criterion, 1944 would be one of my best years. It was far from uninteresting, for there was a useful number of experimental models to be tried. I love being brought in when a model is in the chrysalis stage—when designers have translated their ideas into reality and seek critical analysis. Design is then entirely fluid. So often by the time one is asked to try a new model and comment the most that can be altered is a minor detail, for the Show is in the offing and it has been essential to press ahead with arrangements for the machine’s production. Even when one is invited along in August, ready for the Show in November, one may find, to quote an actual instance, that an item like the rear stand cannot be altered—its improvement must wait until towards the end of the next year. Why one is called in is simply that the motor cycle journalist rides most machines—has a wide knowledge of the behaviour of contemporary designs and should, because of this, he able to analyse and suggest. Of course, he would not be invited to try these machines if as a result the whole motor cycle world would be reading about them the following week, However, there are some things which I can say in consequence of my 1944 experiences; they let no cats out of bags, but may interest. For instance, it is no secret that manufacturers have been expending much drawing office paper and a considerable number of miles on the problems of navigation. I was highly amused at the interest displayed in my Teledraulic-equipped Ariel at one factory and how a very knowledgeable member of the staff, just before I left, proceeded to compare the steering of their mount with that of mine. I was glad that the old hand in question had had a flip on the latter—there was some of his factory’s handiwork on the machine, anyway, so it was only right that he should check the result—but I could not help feeling that what he and his colleagues were interested in was how the model handled! They learnt something, and it saved me having to explain that, while the straight-ahead steering with their new layout was super, the steering in traffic and at low speeds in general was—shall we say?—wavy. Another direction in which quite a lot of experimental works needed to get results, which instead of being rather better than those of the past are really outstanding, is automatic ignition advance. If I say that it is surprising how bad auto advance can be you may say, ‘Yes, and we don’t want it, anyway,’ and I should hate you to condemn it out of hand, for I know from my experiences with it in 1944 that it can be really good and that, for all my love of riding as opposed to mere driving, it is something I want to have myself. It has got to be ‘right’, though, and I have yet to ride a motor cycle fitted with an auto advance which I regard as dead right. Since it seems certain that much will be heard and seen of such devices I trust there is going to be some very whole-hearted collaboration between the electrical folk and motor cycle manufacturers—on the road and not just on the test bench. Rear springing is a subject on which designers have widely differing opinions. A motor cycle is far from easy as a proposition. I have learnt nothing fresh over the year that has passed, except, perhaps, that there are more ways of approaching the problem than I should have imagined. Some people seem to me to have tended to lose sight of the basic requirements. My whole experience is that if you are going to have real comfort and leech-like road-holding you must have a system which reacts to really small road irregularities. If the wheel has to receive a hefty bang before the springs deflect there will never be a proper degree of comfort, nor that superbly safe steering and braking that are possible. In addition, of course, the system must be such that it accommodates equally happily the mighty shock resulting from a deep pot-hole. ‘Yes, one designer will say,’ and really absorbs the rebound.’ Personally, I have little use for the type of suspension which leaves the tyre to look after the minor irregularities and only comes into operation when the wheel receives a mighty clout. In the past some have suggested that this is all that can be expected with a vehicle such as a motor cycle. Methinks that if they have not changed their minds already they will do so when they have an opportunity of trying some of the systems that have been developed. (Developed is the word.) Somehow the suspension must be made to move for the undulations and not merely the bumps. Then, and only then, incidentally, does a sprung driving wheel get real grip: all and, I imagine, more than the grip obtainable on a slithery trials section (or ice-coated road) with a rigid-framed job. Spring frames with the characteristics I have quoted have given me a greater feeling of, safety under vile conditions than I have had with any other machines. Two experiences make me add that the system must be designed so that a run over dirty roads cannot step up the amount of solid friction—turn the suppleness of the frame around the ‘dead centre’ position into suspension that calls for hammer blows…For me to say, ‘What has happened to our fuel consumption over recent years?’ may seem stupid,

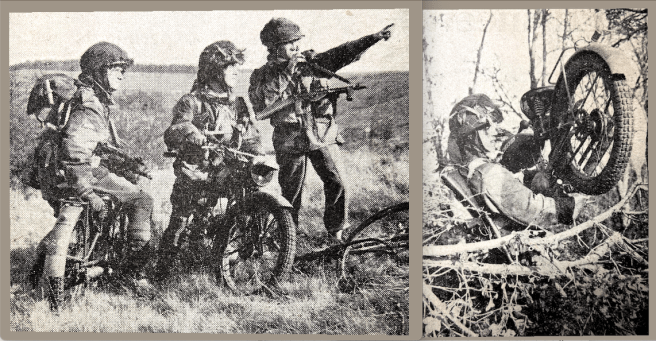

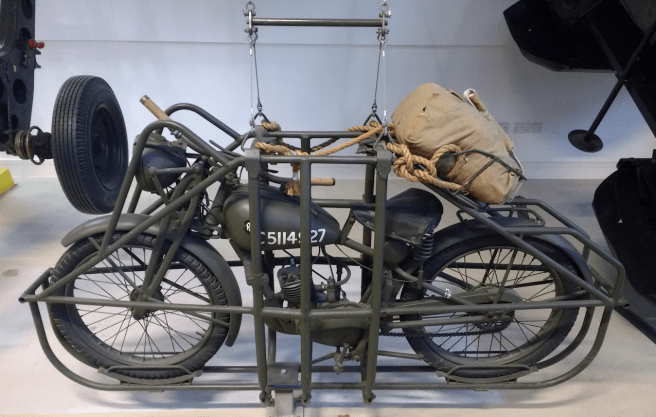

for I should know, but this is a question which every manufacturer might well put to his design staff. In a ‘Workshop’ article a short time ago I mentioned a 420-mile day on a 500cc motor cycle which involved the use of only five gallons. The greater part of that distance was covered at an average speed of well over 45mph. Under similar conditions how many modern machines would do the day’s journey on less than seven gallons? A fact that escapes many is that at one time it was the rule for 500cc solos to do over 100mpg. And those were days when compression ratios were low and engines, allegedly, inefficient. Few of us needed huge tanks then. Of those machines one can talk about, I suppose the most interesting was Mr. Connell’s special Scott, the ‘Victor’. I regard the article on the two-stroke that would not four-stroke as one of the most important I have had the opportunity of dangling before motor cyclists. To get all two-strokes two-stroking right from tick-over—a 600rpm tickover—is not going to be easy. A lot of research is required, and only in part on the sparks side. The spark and the very wide range of advance-and-retard, preferably ingeniously controlled automatically, are important, but it is, I believe, hardly possible to over-emphasise the importance of the silencing system design. The silencing system can make all the odds over two-stroking. It has got to be designed for the engine. A side-line which interested me a lot was that the ‘Victor’ refused to smoke. This was surprising and pleasing. You may remember that following the article I heard from an enthusiast with unique experience of tiny two-strokes used in model aircraft and boats and that he said in reference to engines of 4-9cc running on a petroil mixture of 3 petrol 1 oil (!)—’With four volts passing through the coil there is quite a blue haze, but with six volts these little engines produce vastly increased power and the blue smoke is almost eliminated.’ I know that there are some who can hardly credit the results. The facts, however, speak for themselves. Apart from my own Four, the Victor and hush-hush models, I rode over the past year WD Ariels, Nortons, BSAs, Matchlesses, Ariels and Royal Enfields, a Vincent-HRD Rapide, 125cc James, 125cc Royal Enfield—yes, and an autocycle or two. The majority of the non-specials were WD jobs. I will not go into detail, but make merely a comment or two. The first is what a weight the general-purpose WD models are. They have got to be sturdy, one knows, and there is sundry equipment necessary, but all-up weights of around 400lb are excessive and I, for one, hope that after the war the pendulum is going to swing. Weight is often said not to matter when one is on the move, but weight strangles performance and does not help the brakes, the hill-climbing or the cornering. For an Army man under bad conditions weight can be ‘killing’. Why the Army’s 125s can be used successfully under conditions impossible to other motor cycles—sometimes to all wheeled vehicles—is because they are so light. Even they could be and should be appreciably lighter. And in my experience the reason one hears reports such as ‘they were our only vehicles that were mobile throughout the Normandy campaign’ is that, being so light, they do not get battered to pieces. I have done much riding of these ‘Flying Fleas’ over the year—thousands of miles. The pleasure they have given both on the road and in the rough, has been immense. There have been no breakages and, other than plugs cutting out owing to the lead bromide of MT80 fuel and lamp contacts and cables, I have had no trouble. I am forgetting one thing: a rivet in the saddle of the James sheared, which was not surprising in view of all the almost fantastic rough-stuff. Where the Fleas have been improved by their adoption for Service use is in their riding positions. The raising of the saddles has made a lot of difference to the comfort. Incidentally, I still swear by the rubber-band suspension of the Royal Enfield front forks; it is the goods. The 998cc Vincent-HRD Rapide was mentioned in a ‘Workshop’ article—mentioned in regard to its experimental, free-from-slipping clutch. Of all machines I have ridden over the past year only the Rapide had handlebars which I regard as 100%—narrow and with the ends set at exactly the right angle. Nearly everyone who has tried Vincent bars swears by them; why cannot all other makers provide bars which call forth similar eulogies? There is a lot in getting the bars just right, from both the bodily comfort angle and that of perfect control. Already a hint or two has been dropped by the makers about there being a still cobbier and lighter Rapide after the war. A 1,000 that is a 500 in weight and wheelbase—a Rapide like this—what a thrill for after the war! My experience with side-valves has been limited to the WD jobs—the 16H Norton and the M20 BSA—and to a mile or so on a 1,140cc Royal Enfield sidecar outfit. Is the side-valve dead, or shall we find in this country someone who, like, say, Jonghi, decides that the most has yet to be made of the side-valve? I have a very soft place in my heart for this type of engine. It has something the others haven’t got, and it usually is the most certain of starters. Technical folk declare that they can provide ohv jobs with all the desirable attributes of the side-valve—several others besides—and none of the vices, but they do not seem to translate such schemes into practice. However, there is the prospect of new side-valves in the form of twins, so maybe if there is not too much latter-day over-head-valve technique we shall be seeing the side-valve to the fore again. What else is there to relate? Only this, I think: that in common with all of you I am yearning to try some real civvy-street jobs—hoping that 1945 will be a never-wozzer in the matter of interesting machines ridden, and that 1946 beats even 1945 into a frazzle. Hope springs eternal…”

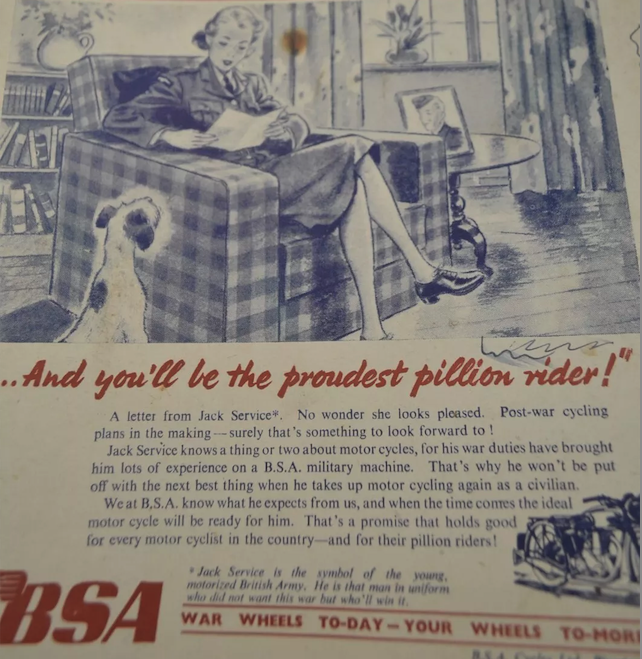

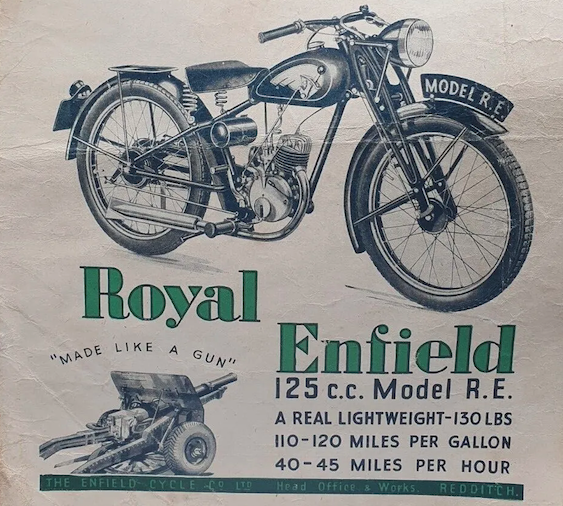

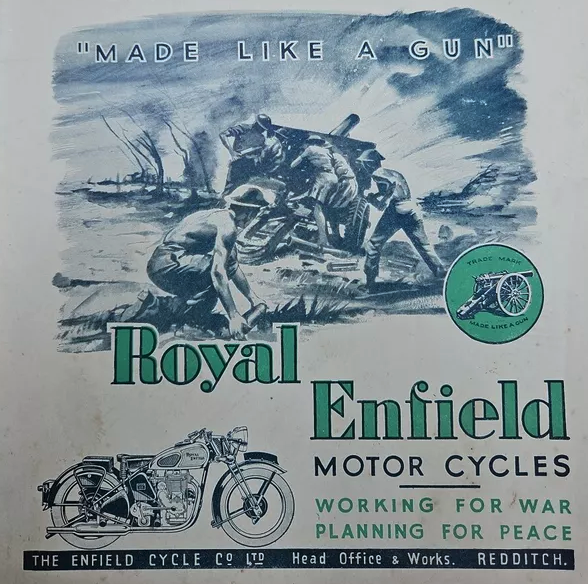

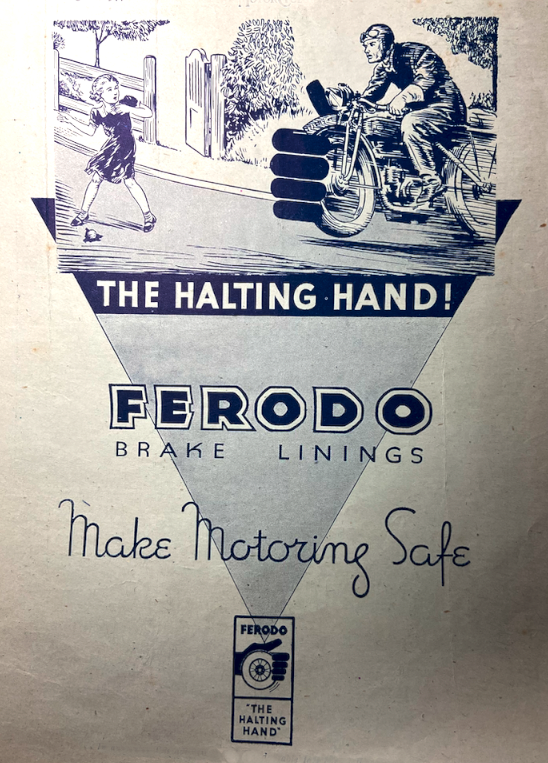

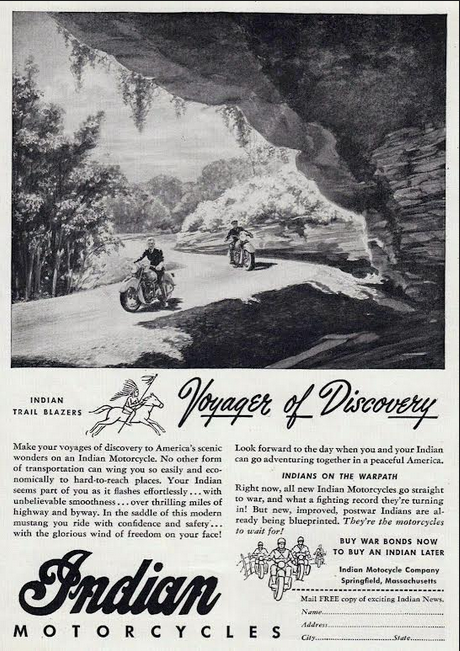

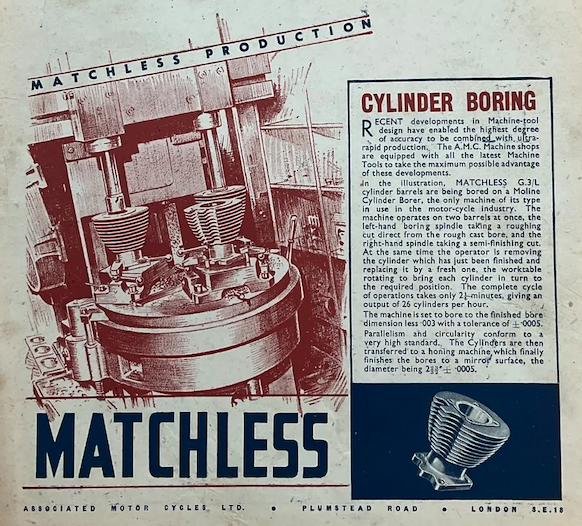

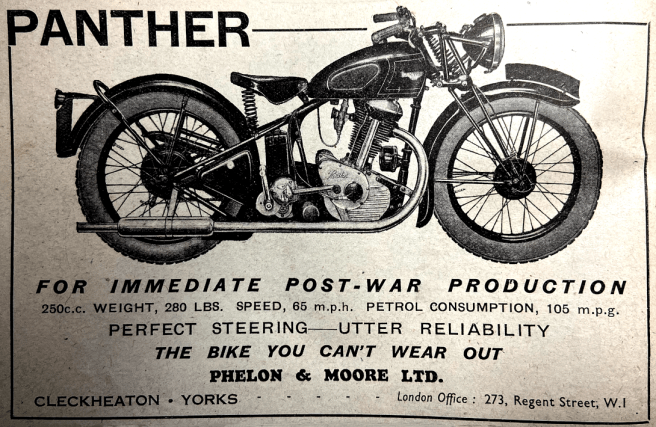

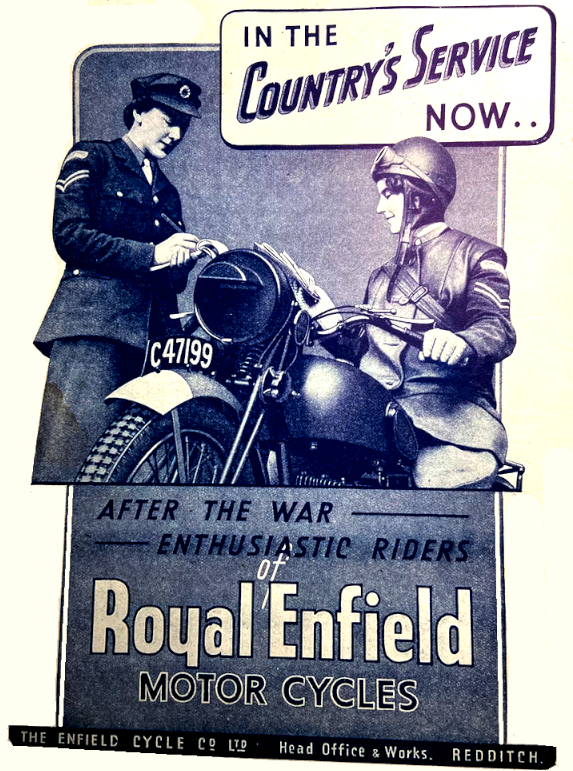

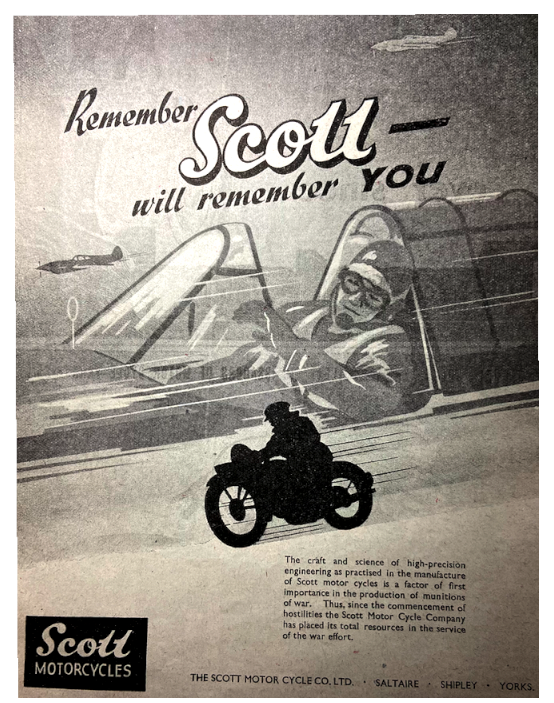

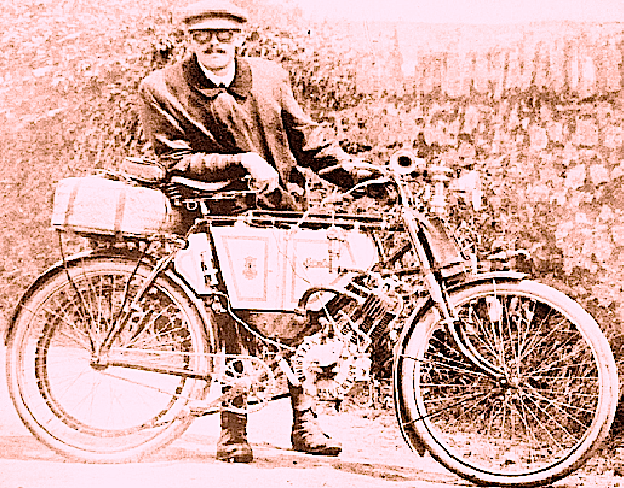

As usual, here’s a batch of contemporary ads.