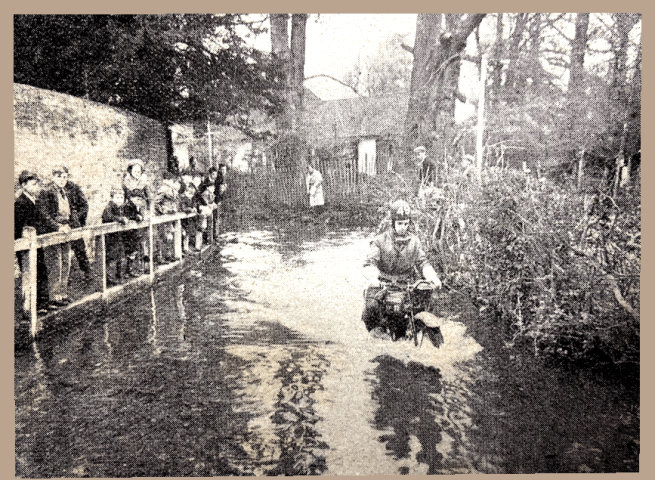

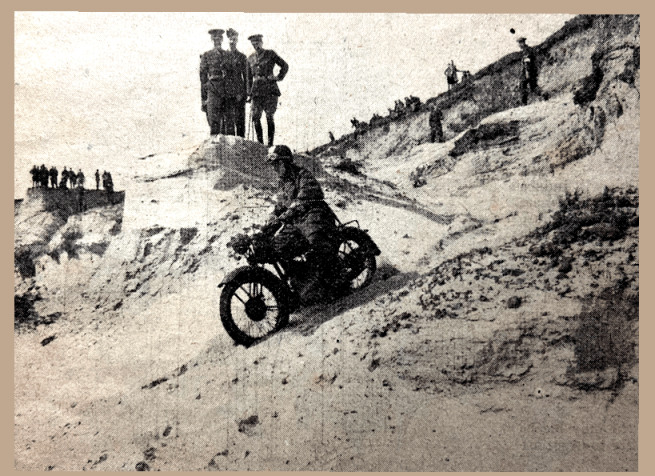

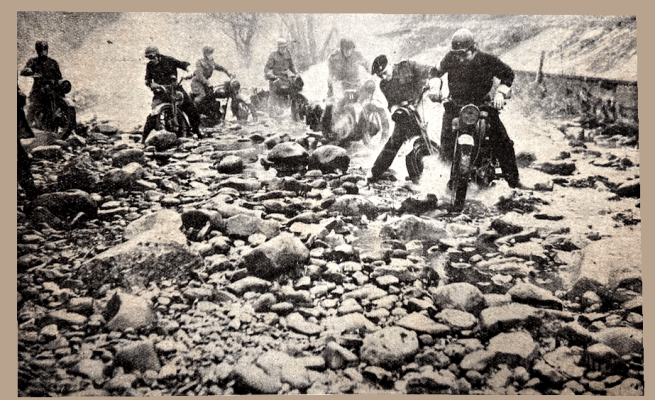

“ON SUNDAY RIDERS from various companies of a divisional RASC in the South-East competed in a trial, the object of which was ‘to afford riders an opportunity of putting into practice lessons of cross-country riding learnt in previous instruction, and, as a result, to improve the standard of cross-country riding.’ Most of the competitors were drivers, with a sprinkling of officers. Most of them knew little or nothing of cross-country riding until comparatively recently; their only instruction had been virtually in their spare time—a few short evenings devoted to various types of hazard, with the usual procedure—lecture, demonstration, plus personal attempts, with mistakes pointed out and corrected. Primarily a team event, the Medway Challenge Cup Novices’ Trial, as it was officially termed, had much of the delightful atmosphere of an inter-club competition, with friendly rivalry between the various units. The Medway Challenge Cup was put up by Major GLM Smith-Masters, who was responsible for the organisation and general direction of the event, ably assisted by Capt JR Gilder and Capt HP Clayton. The competitors, 66 in all, were started at intervals; every one of them was similarly mounted-on standard 350cc side-valve WD Royal Enfields. Some of the machines were said to be about three years old, which, with the kind of life led by the average WD machine, spells a rather ripe old age! The 11 observed sections were on a commendably brief course, mainly short and very well chosen. Among notes on the route sheet was the following: ‘On observed sections think what you are going to do before you try them and remember what you have been taught.'”

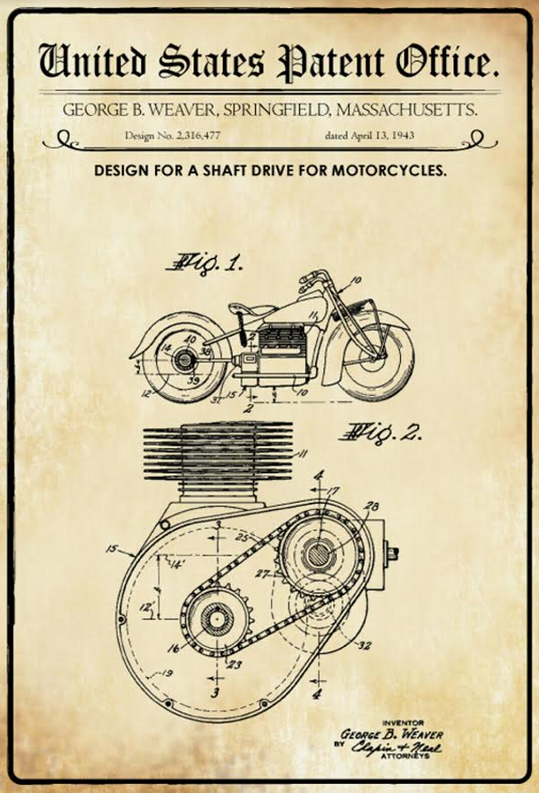

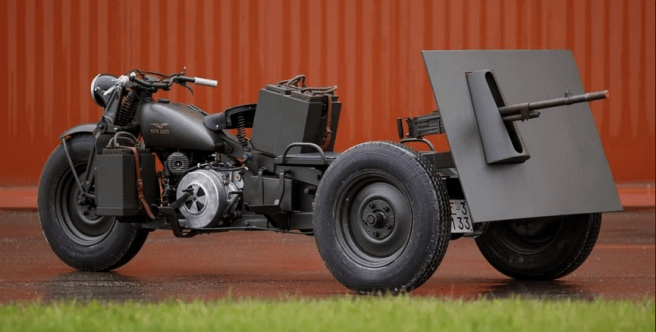

“CRITICISM OF THE BRITISH Army’s motor cycles following the Middle East and Tunisian campaigns is probably inevitable. Not only have there been semi-official comments that Axis machines are better than ours, but also eulogies of German and Italian motor cycles from motor cycle enthusiasts in our Forces, officers and other ranks, who have been fortunate enough to lay hands on captured machines and use them as their personal ‘hacks’. We do not say, and do not consider, that the present WD motor cycles are the best possible for military use. On the other hand, sober analysis does not suggest that the Axis has excelled itself. In all discussions of relative worth it is necessary to think in terms of ‘fitness for the purpose’, and the purpose in this case is purely military. The question, surely, is whether British despatch riders would be better served by Axis machines than their own, whether traffic control motor cyclists are better equipped in the enemy’s ranks than our own, whether German or Italian motor cycles are better than ours for convoy work, and so on. It is not a matter of being intrigued at being provided with a spring frame, or relishing the trouble-free nature of shaft drive. The whole question is ‘fitness for its purpose’, and in the case of Britain it has been a matter of considering the battle-fronts of the world. The Axis has issued its motor cyclists with machines of types which comparatively few German or Italian civilians could afford before the war. Certain of those motor cycles are extremely good and possess features which every motor cyclist must belaud. But nothing we have seen to date leads us to believe that those responsible for Axis military motor cycles are in any way super-men. To quote one point regarding the solo machines, there is their weight. Features there are is which are worthy of close consideration by our authorities at home (and we trust the responsible authorities will examine, test and analyse), but it would be a pity if this country blinded itself to the only thing which matters, namely, that the motor cycles shall be the best possible for the work for which they will be employed. The motor cycles with which the British Forces are equipped are very ordinary machines of inexpensive type; basically, they are, in the majority of cases, not specially modern, civilian-type models. As readers will recall, it was not until the time of Dunkirk that the General Staff were aroused to the fact that motor cycles possessed any great value other than for carrying despatches. Then there was the cry for more motor cycles and still more motor cycles ; the War Office even issued an appeal to the general public to sell their machines to the Government. It is a matter of history that in the early part of the war the majority of motor cycle firms, with no Government orders for motor cycles, had to turn over to other work, and, when the call for motor cycles came, there were not the necessary production facilities. In the interim it has been difficult, if not impossible, to change to new types of machine; to do so would upset production, and any decrease in output was unthinkable. Lately, however, there have been changes in all manner of directions, and the question arises as to whether the present may not be an opportune time to review the whole matter of the military uses of motor cycles and, at long last, produce machines which are the ‘best possible’.”

“PSYCHOLOGISTS aver that smell can stir our emotions even more powerfully than sight or hearing. Be that as it may, a Detroit cinema began in 1942 to experiment with smell as an adjunct to its movies. Cartridges packed with various odours were discharged by compressed air through the theatre’s ventilation intakes. A seafaring film was screened against a tarry background, Marlene swung her million dollar legs in a strong Coty atmosphere…A pungent whiff of cordite floats through the house when the FBI man plugs the gangster in the stomach. And, of course, in all speed shots of motor cycles, a quart or two of Castrol R are evaporated, and a bit of synthetic rubber is frugally singed. I must confess that these two last smells would certainly inspire me with an intolerable nostalgia in the present famine of fast motoring.”

“A LITTLE REMARK was let slip the other day; it was that among the types of Brough Superior there are (or have been) ‘two three-cylinders (Bradshaw-designed), rotary-valve and side-valve’. There have been rumours that Mr Brough was interested in three-cylinder engines; it has also been known that he and Mr Granville Bradshaw have been in conclave. The inference from the recent Brough Superior announcement is that the ‘Threes’ are the latest designs. To date nothing has been vouchsafed. Even past comments about three-cylinders constituting a not uninteresting proposition failed to extract much more than the remark that they are! We shall see.”

“BETWEEN 1922 and 1928 you were kind enough to publish a number of articles and letters of mine, the later of which mostly dealt with sundry modifications to the design of a 1923 Triumph Ricardo rebuilt with a two-valve head, and the results thus obtained. I should like to put it on record that this veteran, after some years of retirement prior to the war, was still going strong until laid up in December last, and that her petrol consumption has averaged 106mpg and oil consumption about 2,500mpg, a pillion passenger often being carried. On one long double journey in company with a friend riding a modern Tiger 90, his petrol consumption was about 85mpg while mine was up to its average. Due probably to the Tiger’s 100lb greater weight, my acceleration up to 50mph was as good as his; my advanced years discouraged me from exceeding 55mph, which could be reached with lots more throttle available. The one and only mishap during this war period (apart from some tendency of the elderly saddle to come adrift) was the breakage of an outer valve spring—of my own design!—but this caused no delay on the road, for 45mph can be held on the inner spring only.

Kenneth H Leech, AMICE, BSc (Engineering), Chippenham.”

“IT IS NOW ALMOST as dangerous to ask any knot of young men whether a piston stops as to mention the Pope in Londonderry. The latest dictum is that ‘stop’ means a ‘period of time’, and not a ‘point in time’. Will those who hold this extremely revolutionary view of the King’s English please proceed to define a period? Apparently they mean that an hour is a ‘period’, but that one-fifth of a second is not a ‘period’. What authority do they adduce for this dogma? Actually, both sides are surely quibbling? Motion may be arrested for such an infinitesimal period of time that for all sensory or measurable purposes the arrest may be ignored. I would like to complicate the dispute by asking what happens at both ends of the stroke to a piston with a badly worn gudgeon pin bear-ing, plus a ditto on the big-end of the rod? Does it perform a miniature tap dance?”

“I SHOULD LIKE to enter this piston-stopping argument. I look at it this way: Revolve the flywheels at, say, 66rpm and the piston will definitely be seen to come to rest at TDC. Now double the rpm and the stationary. period will he halved; double it again and the stationary period is once again halved. You can go on doing this up to thousands of rpm, but that stationary period will always be there, no matter how many decimal places you halve it to. So the piston does stop.

RWRW, Warwick.”

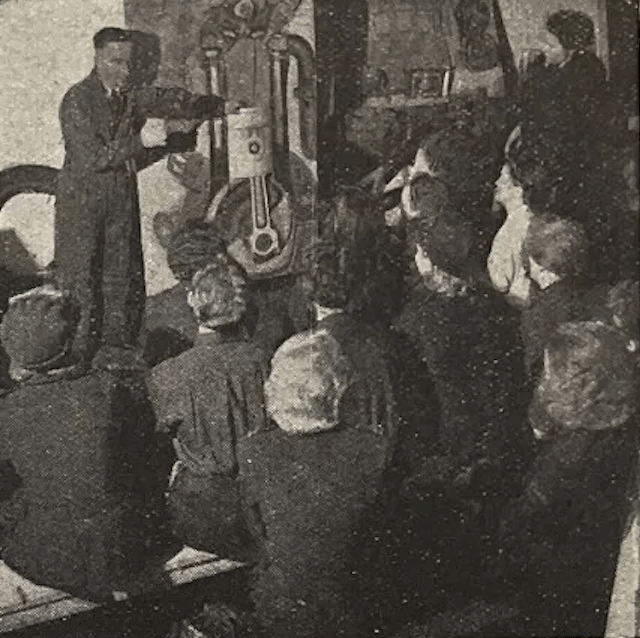

“AFTER READING the article from an officer who says that the piston does not stop, I have decided to give you my experience and settle the question once and for all. It was very nice the way he worked out that the piston travels in an arc, but this is not so in practice, although it sounds good in theory. We have here several cutaway engines for demonstration, and if they are turned over slowly you can actually see the piston stop both at the top and bottom of the stroke; in fact, we held the piston still at TDC, and it was possible to move the crank a few degrees in either direction without moving the piston. If anyone still doubts this I can only advise them to try to find a place where they have an engine with half the cylinder cut away and see it for themselves. Good luck to the Blue ‘Un, and keep it going.

CVX194.“

“THE LETTER FROM Mr F Parker is rather amusing in that he considers it an ‘elementary’ problem as to whether the piston stops at TDC and BDC. I would like to ask him a question. Assuming it is admitted that the piston only stops for an instant, an infinitely short space of time, what is his definition of ‘stopping’? Surely it is that the piston shall occupy the same position for more than an instant. How, then, can we say that it stops ‘only for an instant’?

HD Pinnington, Home Forces.”

“‘OUR CLUB IS CARRYING on although our membership is dwindling (owing to members joining up), and we will continue to meet just as long as there is one member left.’—Pennsylvania motor cycle club’s report.”

AMC SOLD THE SUNBEAM marque to BSA which also acquired Ariel from Jack Sangster, who wanted to concentrate on building up Triumph Engineering (where Edward Turner had become managing director). Ariel stayed on at its Selly Oak base.

“COLD, WET RIDES were under discussion. The man who spends his life carrying out mileage tests of WD motor cycles mentioned the pleasure he obtained from long, hard runs in the winter: how he might arrive at his destination cold and not entirely dry, yet he had thoroughly enjoyed the day. Every enthusiast knows the sense of achievement to be gained from battling successfully with the elements. At one time this arose from the completion of any journey—those early days of which Ixion writes so amusingly. With the growth of machine reliability, much of the romance of riding a motor cycle disappeared according to some, though it is noticeable that the same old hands are seldom backward in suggesting shortcomings in the modern machine. Now that (on peaceful runs) only Nature can provide the odds, it is not surprising that the virile sportsman rebels at the thought of built-in legshields and windscreens. He feels that in losing the wind on his face and the lashing of rain he is relinquishing an essential part of his pleasure. Much the same was said of gear boxes and clutches; and so spoke enthusiastic car drivers when saloon bodies were mooted. The latter were not forced to purchase closed cars when they were introduced, but the vast majority changed to such cars before very long. Motor cyclists will not have to buy machines with better weather protection after the war, but there are many who are compelled to use their motor cycles irrespective of the conditions (which is not always so with those in the enthusiast class), and who, if provided with efficient, built-in shielding after the war, will find it a boon. Even if such shields eventually become standard, presumably there will be something left for the enthusiast, for what provides a sense of achievement to equal that of making a good showing in a difficult sporting trial or scramble? ‘Yes,’ some may say, ‘but that would be impossible on a machine with shields.’ The answer, of course, is that it depends upon the nature of the shielding. The oft-mentioned 398cc ABC was no less suitable for sporting trials because of its legshields and under-shield. Assuredly, greater protection from the weather will be introduced and sooner or later become the rule.”

“HOW MANY MOTOR cycles there are on the roads of Great Britain after the war depends not so much upon the types of motor cycle offered to the public as upon whether the Government encourages the use of motor cycles. Such is the view of manufacturers. They say that if there were no driving tests, licences and insurance required for autocycles and other small motorcycles—if the treatment of motor cycling was similar to that accorded on the Continent pre-war—there would very soon be over a million motor cyclists in Britain, a home market which would greatly assist them in selling motor cycles overseas. There is no doubt that had Germany, for example, not removed restrictions from 200cc motor cycles she would never have built up her great motor cycle movement…Henceforth Britain must be prepared: there is no hobby sport which provides such valuable training for peace or war as motor cycling.”

“IF SURPRISE AND EXCITEMENT accompany a meal abroad, the high notes of an unfamiliar table at home are usually either solid satisfaction, or—occasionally—disappointment, when a bad meal is dished at an inn where unimaginative owners are content to line their pockets from the bar and chuck poor food at their clients. Surprise may not be absent, as when a Cotswold inn serves a huge Spanish onion, piping hot, with a grilled kidney mysteriously sheathed in the onion’s heart. But surprise is rare. I wonder what English meal stands out most clearly in my readers’ memories? Mine was a simple meal, served in a simple roadside inn. Three of us had driven far north in a Riley tricar to test its paces on Sutton Bank. We had travelled all night, and the night had been cold. We stopped at Osmotherley in Yorkshire for breakfast. Our hostess served a huge dish of grilled ham and eggs. Four eggs per head! Great succulent slabs of ham, an inch thick at the centre, as tender as blancmange. Or again, when a Zenith Gradua and a Rudge Multi had both elected to give us day-long trouble. We had tasted nothing since lunch, and we ran into Bridport starving at nine. The innkeeper regretted that dinner was long since over. He would ask the cook to do her best. Anon he returned to say his son had just come in from a fishing trip, and he served the largest grilled sole I have ever met. It was as large as a tray, and was followed by a pie of Morello cherries. No complaints, thank you! Or when similar roadside troubles delayed us, and a Berkshire inn served a dish of freshly caught grayling. Is the grayling our finest fish, or was it just hunger-sauce that rendered them so delicious? Not every surprise is all it threatens to be. Four of us once blew in to the Cartwright Arms at

Aynho for lunch. The landlord informed us that it was our lucky day—they’d just been thinning out the apricots, which are a feature of that lovely village. But the apricot tart was a shock. Baby apricots are all stone and no pulp. It is hard work to chip the pulp off them with a spoon, unless his cook had tripped up. We spanged them all over the carpet with our ineffectual spoons. But surprise works both ways. Once in an ACU Six Days at Taunton I found every pub full, and was put to sleep out at a local railway worker’s. I sulked about it, as I had booked my room weeks in advance. But at 5am next morning Mrs Railwayman brought me up a quart mug of steaming tea, and a mighty jug of boiling water to shave in, preliminaries which nobody enjoyed at the official hotel. There is usually a lot of crowding at the hotels on a Scottish Six Days. The menus display a certain monotony —you can almost bet on cold salmon with cucumber, cold roast lamb, and apple tart. But the Scottish salmon and lamb take the sting out of monotony. Often the tables are already spread for the hungry horde which bursts in at midday; and I have seen an Edinburgh official arrive early, and imitate the Mad Hatter’s tea party in Alice in Wonderland, by moving round the laden board and emptying six plates of cold salmon before the boys got in. This same worthy once shared a two-bedded room with me, and when we rose at 5am he silently offered me his flask. I had no stomach for whisky at that hour. He only knew one reason for refusing whisky at 5am, viz, that one had drunk too freely overnight. But he knew a cure for that, and offered me flask No 2. On my enquiry, he explained that it contained Kümmel, which North of Tweed ranks as an antidote for overmuch whisky. When I refused the Kümmel, he struck me off his visiting list. At another Scottish hotel, trouble en route caused me to arrive

after all beds were let. I slept on a sofa under an open window in the lounge, and developed acute lumbago. Next morning I was lifted into the saddle and completed the trial to earn a gold medal. As those were the days of single gears and LPA (‘light pedal assistance’) any reader who has ever had a bad go of lumbago can imagine my agonies during the day. I know quite a lot of motor cyclists who cherish warm memories of a Lyons mixed grill, which for years ranked as a sort of standard midday meal at the Olympia Shows. But to my thinking the best mixed grills in the world used to be served in the Danum Grill at Doncaster. I have already indicated that the quality of a chance meal in this country, even in peacetime, is something of a gamble. But even gambles come off now and then. During the last war I rode down into Devon in midwinter, and put up at the Bedford Arms at Tavistock. The head waiter was dubious. Rationing was in force, the hotel full and the hour late. He came back presently—did I fancy a devilled bone? Now a devil bone is a rarity in the present century. For some mysterious reason it went out of fashion with Beau Nash. One occasionally meets it in a private house, where the wife knows her job; but at hotels and restaurants it is as defunct as the dodo. Well, I agreed, and presently the ‘bone’ arrived. They’d had a Norfolk turkey at dinner the day before, Christmas being just over. It must have been a 30lb. bird, and had evidently died in its prime. It was the very best eating in the meat line that I have ever struck; and I live in hopes that some day some hotelier will offer me another to match it. Beat it, he could not. Ever since that late supper my definition of ‘waste’ has been ‘a turkey leg undevilled’! Very few women know how to organise a picnic meal. Most of them pick sandwiches as the main dish, though they ought to know that the bread of sandwiches dries stale in an hour or two. I except one lady of my acquaintance, and accept her picnic invitations at sight. She comes from Kegworth—ever been there? In Kegworth there is a pork butcher who makes pork pies worthy of at least equal esteem with those hailing from Melton Mowbray. I think they’re the best in the world. Now a fat slice of pork pie is perfect for a picnic. It doesn’t stale, it doesn’t drop crumbs, and it is first-rate eating. Fun and games are associated with many famous hotels in motor cycling minds. There is usually some kind of a rough house at least on the last night of a Six Days.

Indeed, there are quite a few British hotels at which motor cyclists en masse became either temporarily or permanently unwelcome. One landlord overcharged us and treated us very casually. He woke one morning to find that during the night all the chairs and tables had vanished from the tea garden which was the pride of his life. Some time elapsed before his staff realised that the entire outfit had been transported during the night and was festooning the trees in his garden, where they were securely wired. Another landlord excommunicated us because some bright spirits, deeply imbued with the spirit of speed, organised a sweep for the fastest time from the basement to the attic in his lift. In rather a different category stand the before-breakfast bridge parties which once occurred at certain Liverpool hotels. Some of us found it necessary to return to London as soon as possible after a TT. This entailed catching the night boat out of Douglas on the Friday—usually that ‘peerless ocean greyhound, ss Fenella‘, the old Fenella which took about eight hours for a trip which the Ben-my-Chree could do in under three. Reaching Liverpool towards 3am or so, we would start a bridge game in our hotel until it was time to wash and breakfast ready for the express to Euston. Many world-famous men have won and lost money at these early bridge games, and the hotel staff naturally thought we were all quite mad. Well, well, some day the British hotel and the British cook will return to their own, and I hope handle their job even better than they did before That Man came into power and laid a pleasant world in ruins.”

“THE SECOND LEADING article last Thursday mentioned the new motor cycle clubs that the despatch riders of Home Guard and Civil Defence units are determined to constitute when the day dawns. Last week-end the Editor had an invitation: the DRs of his local Home Guards, he was told, had decided to form their club now, the Commanding Officer had accepted the presidency; would he become vice-president? A name has been chosen for the club, a banking account opened for the weekly sixpences the Don Rs have been paying, and the aim is to get in touch with all the lads who had been despatch riders in the battalion and passed on to the Regulars, and to get everything taped for the future. The name is ‘Syx Don R MCC’, meaning the 6th Surrey Battalion Despatch Riders’ Club. Is this the first of the new clubs to be actually formed?”

“HOW MANY MOTOR CYCLES there are on the roads of Great Britain after the war depends not so much upon the types of motor cycle offered to the public as upon whether the Government encourages the use of motor cycles. Such is the view of manufacturers. They say that if there were no driving tests, licences and insurance required for autocycles and other small motor cycles—if the treatment of motor cycling was similar to that accorded on the Continent pre-war—there would very soon be over a million motor cyclists in Britain, a home market which would greatly assist them in selling motor cycles overseas. There is no doubt that had Germany, for example, not removed restrictions from 200cc motor cycles she would never have built up her great motor cycle movement. Why this was done is obvious, and it may be alleged that there is no parallel here. This is not so. Henceforth Britain must be prepared; there is no hobby sport which provides such valuable training for peace or war as motor cycling. But official encouragement—sweeping away, or even reducing, the difficulties in the way of motor cycle ownership—is not likely to occur automatically. It must he proved conclusively that this is in the best interests of the nation. A brief must be prepared setting forth the benefits that would accrue. This should not be difficult. Figures showing what removal of the fetters has meant to other countries in home sales and exports are available; innumerable facts as to how motor cycling, and knowledge gained from it, has helped this country—in the Services, on the home front, in the manufacture of munitions, etc—can be collated; above all, concrete proposals must be adduced by the industry itself. It must be shown that the trade can and will play its part; it must take the authorities into its confidence in the matter of plans and reveal that it fully realises its responsibilities and obligations. Among these latter is, first and foremost, the question of noise…Achievement of a greater degree of road safety by reducing vulnerability and perhaps even providing initial training in riding are ether points. Also, there are such matters as estimates of the employment and sales that can be achieved under stated conditions. We repeat: If motor cycles are to be encouraged, instead of discouraged, as in the past, it must be (and can be) proved that this is in the best interests of the country. There must be a cast-iron case, stressed and restressed.”

“SOME DISQUIET HAS been caused by the recent discussions on future design. That they have been interesting, all agree, but a number of motor cyclists have gained the impression that their personal needs and desires are likely to be overlooked in the post-war programmes. One criticism which is widespread is that manufacturers have their eyes focused on expensive types of machine—that sound, simple motor cycles of the sort which ex-Servicemen will be able to afford will be non-existent. Others take the opposite view: that the discussions reveal a singularly uninspired and conservative outlook among designers and the industry as a whole. Where is this ‘brave new world’ we are promised? they ask, in effect. Some add that they yearn for outside firms to enter the motor cycle industry—concerns untrammelled by thoughts of the past designs and past failures. One such firm, it is suggested, could bestir the whole industry. What is the truth? First, we will agree that the industry is conservative and mindful of the past, but the recent discussions cannot be taken as a true indication of manufacturers’ intentions. How many readers in business on then own behalf would inform their competitors what they proposed to do immediately the war was over? On the face of things, those discussions revealed no fresh spirit of endeavour. Our belief, however, is that motor cyclists will not be dissatisfied when the day comes that the true post-war designs are launched. There will be many surprises of a type to give real pleasure, while, so far as sound, inexpensive motor cycles are concerned, our industry has never been one to forget the ‘bread-and-butter’ market. It knows full well that there are more people with short parses than long ones. We feel that there need be few doubts in either direction.”

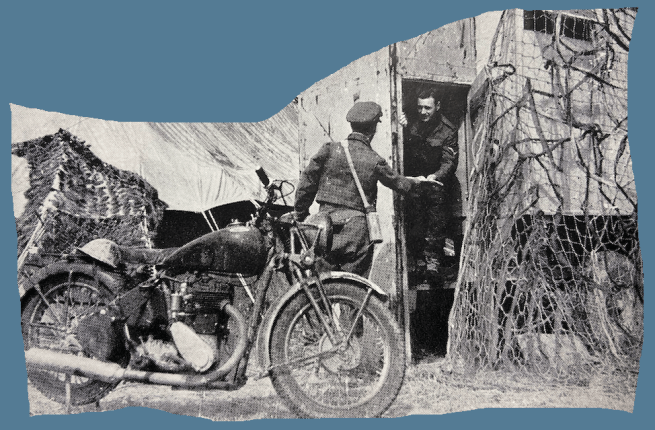

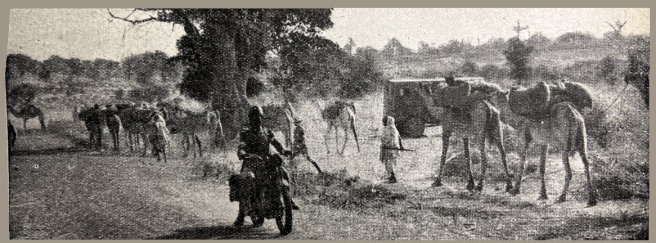

“WITH THE RAF despatch riders in the Western Desert: RAF motor cyclists, unknown to the world at large, provide the vital point-to-point link: desert conditions, speed of advance, hazards of war—often these preclude any other method of communication. The DR, as usual when his job is toughest, comes into his own. The glimpses here are of an RAF motor cyclist who, before the war, was a London shipping clerk.”

“THAT THERE IS NO special need for motor cycles of over 350cc—not, at least, solo motor cycles—is a view that has gained considerable currency of late. The basis for it, apparently, is that many a 350cc motor cycle of the past was capable of a maximum sided of over70mph and would ‘cruise’ indefinitely at 55 to 60mph—speeds which, it is suggested, were quite as high as road conditions in Britain permitted and appreciably higher than than used by motor cyclists in general. It is also urged that the weight of a 350cc machine is not excessive, and while taxation is not favourable the insurance cost is. Some, it would seem, desire almost to force 350s on to the motor cycle public! It may be wondered whether such people have any experience with larger motor cycles—whether they realise the appeal of effortless performance. Of two machines of equal power output, the one with the larger engine is generally much more pleasant to ride and, given equally good design, material and workmanship, likely to last longer and require less attention. The weight and the fuel consumption can in each case be almost exactly the same. Because the sporting world, with its trials and races, is ruled by cc no sound reason why the mass of motor cyclists should be forced to buy on a basis of engine capacity. The important factors in any tourist machine are ‘what it does and how it does it’—not whether it conform to the engine size for Classes A, B, C, etc, in the world’s record list.”

IN OCCUPIED FRANCE regulations were introduced restricting motor cycle manufacture to three classes: ‘motorcyclettes’ over 125cc; ‘velomoteurs’ of 50-125cc; and ‘bicyclettes with auxiliary engines under 50cc. With the economy under seige conditions no-one was buying big bikes so the remnants of the industry concentrated on velomoteurs and motorcyclettes. A pattern was set that would have a lasting effect on the post-war industry.

“A MINISTRY OF INFORMATION booklet sings the praises of motor cycle despatch riders acting as messengers during air raids on this country. Obviously, when a heavy blitz cuts the wires, communications depend mainly on motor cyclists. The author says: ‘The troubles of driving a car through the rubble, water and clay of a bombed area are multiplied many times on a motor bike. You have greater mobility, but greater discomforts. The compensating factor is that, owing to the acuteness of these discomforts. you quickly lose most of your capacity for apprehension and develop a certain bitter relish for setbacks.’ ‘Bitter relish’ is good, and typically British. The proverb says we Britons take our pleasures sadly. Playing scrum-half behind a weak pack in a blizzard is fun to us, because the job is full of ‘bitter relish’. So is motor cycling on other occasions besides air raids. That is one of the reasons why we love it—with apologies to Promenade Percy.”

“SM GREENING, OF JAP, sends me a good tale of an Ormonde twist grip of the type formed from a spiral cut inside the grip, coupling with a grub-screw in the handlebar. About 1908 Greening lent his machine to his sailor brother for a ‘run round the block’. On the third lap the sailor yelled out that the engine ‘wouldn’t turn off’. Greening Senior yelled to him to make for Stag Hill, near Cockfosters, and Senior would follow. Senior leapt on a pushbike and pedalled like mad to find his brother pale and trembling halfway up Stag Hill. But it hadn’t worked out quite as Senior had planned. He calculated on the engine conking out on the hill, but the Ormonde actually stopped with a broken belt.”

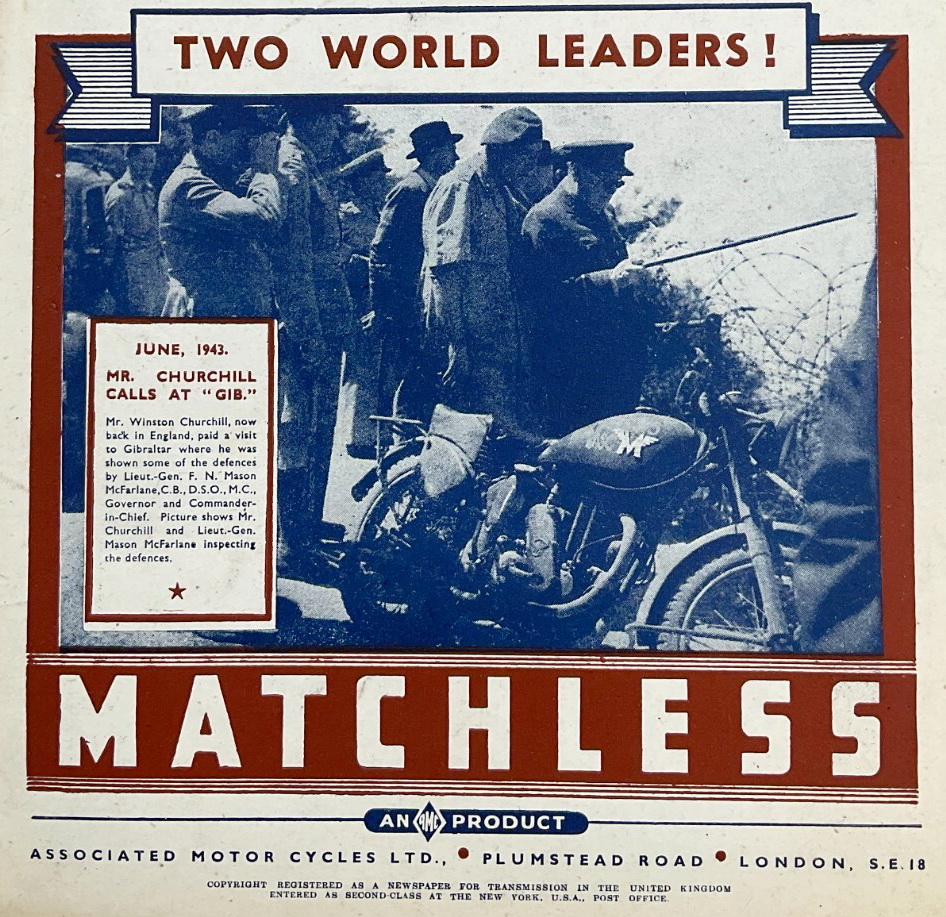

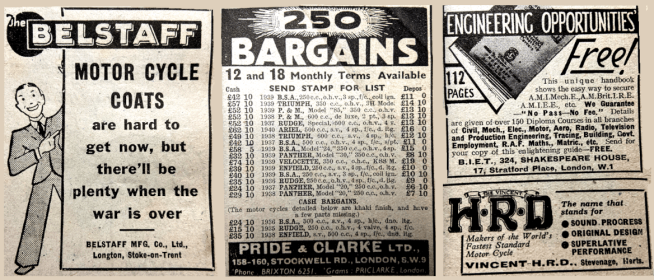

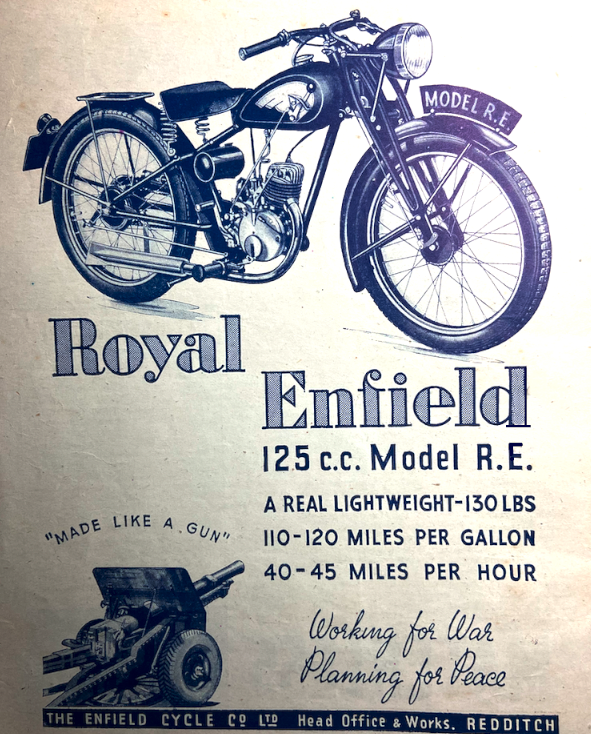

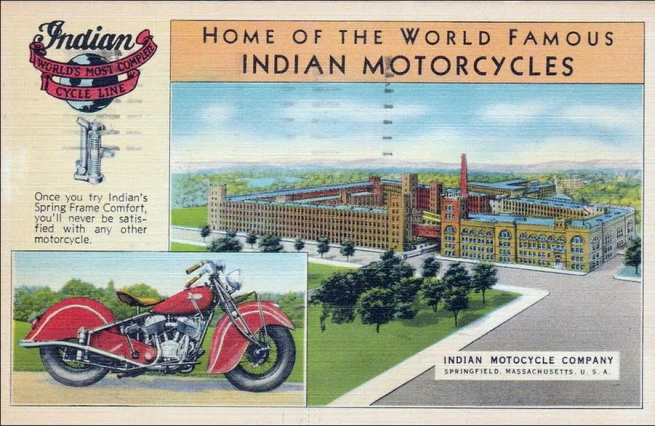

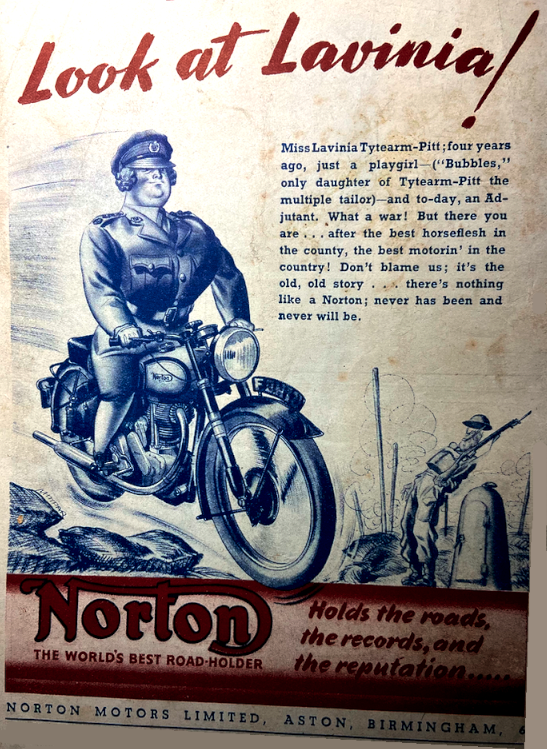

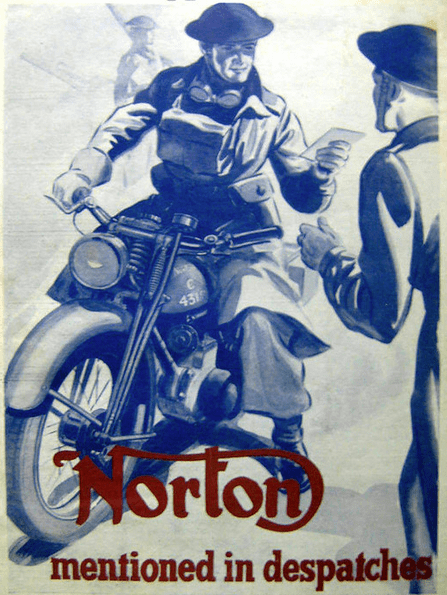

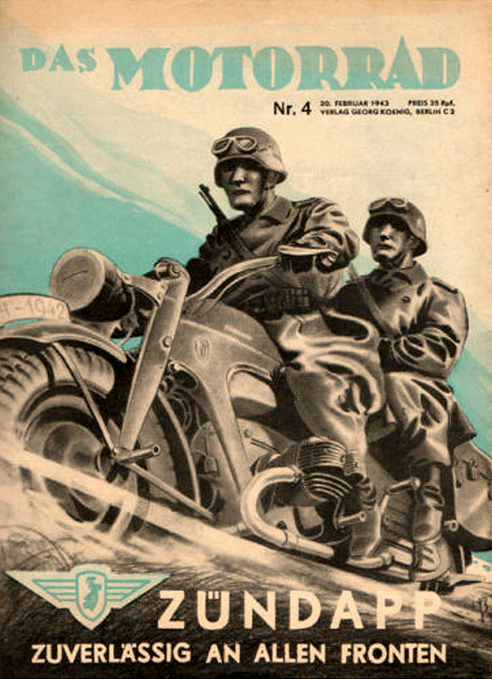

You find more 1943 pics in the World War 2 Gallery; here are some contemporary adverts.