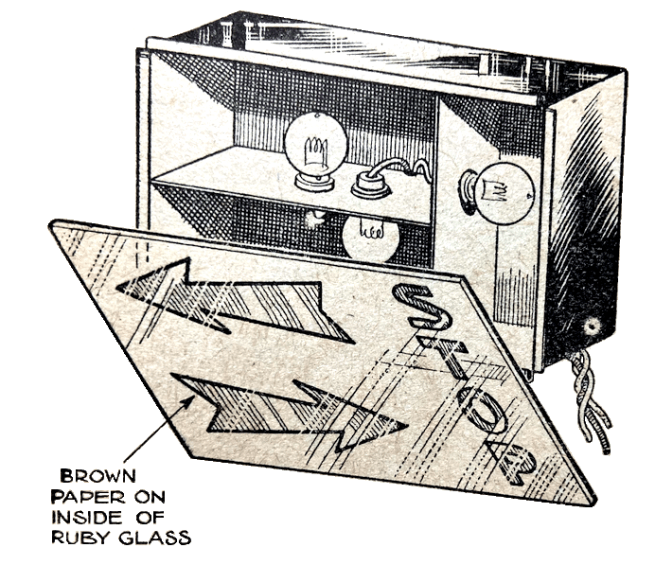

“TO HAND, A LETTER from an enthusiast enquiring whether the TT will be televised this year or next now that the Boat Race and a Rugger international have been televised. I am credibly informed that the technical problems in the way of televising a Manx race from Alexandra Palace are quite insuperable. I did not personally ‘view’ the Putney and Twickenham transmissions, but I watched the Harvey vs McAvoy fight televised from Harringay. (Incidentally, I ‘viewed’ it at a range of 70 miles from Alexandra Palace, which is more than double the guaranteed range.) But it did not rouse me to a passionate desire for the TT to be televised. The screen was so small and the figures so tiny that swift movement was tiring to watch, and it was not very interesting. Motor cyclists’ objection to the news-reel film presentation of the TT is that they get only a few feet instead of a solid hour’s entertainment. If and when a televised TT becomes possible, I do not think it will satisfy enthusiasts any more than the news-reels do—at any rate, not until a far larger screen is available and programme considerations permit plenty of the race to be transmitted.”—Ixion

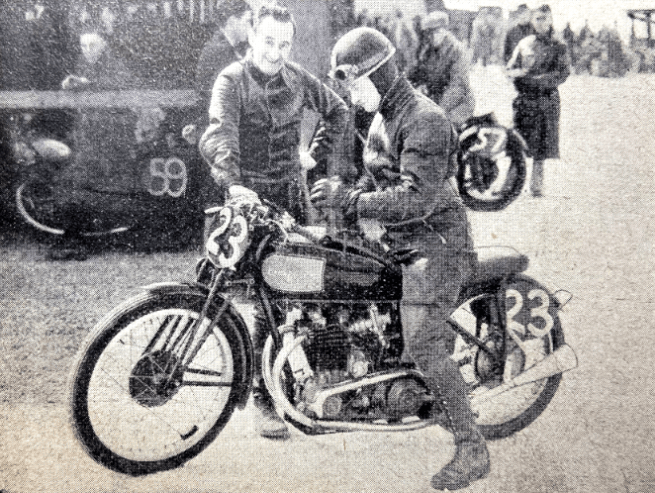

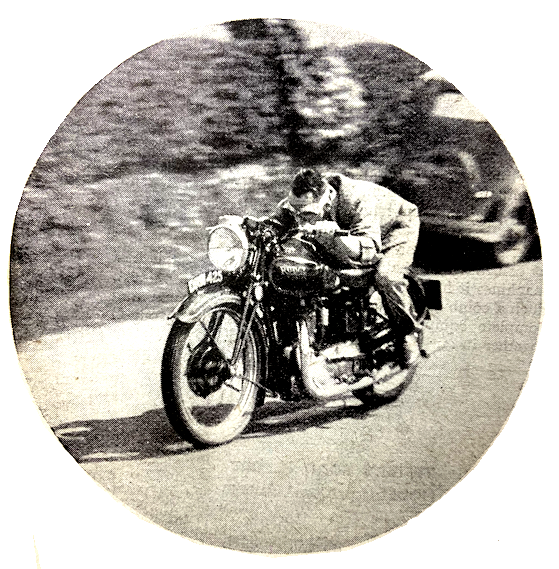

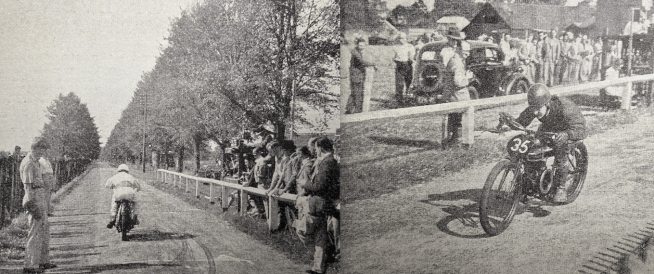

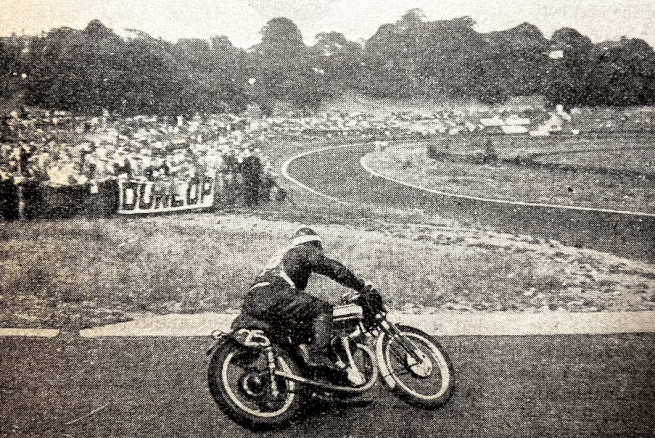

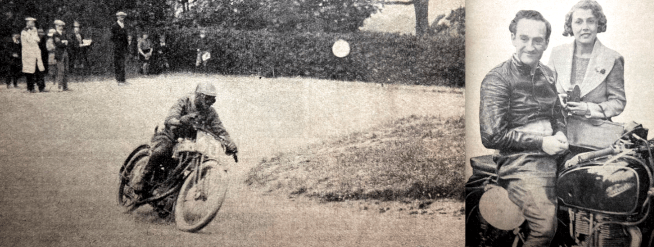

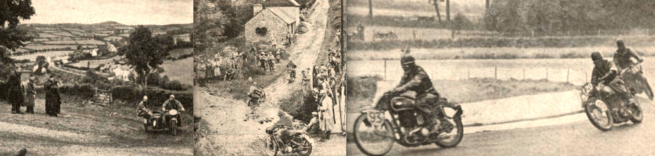

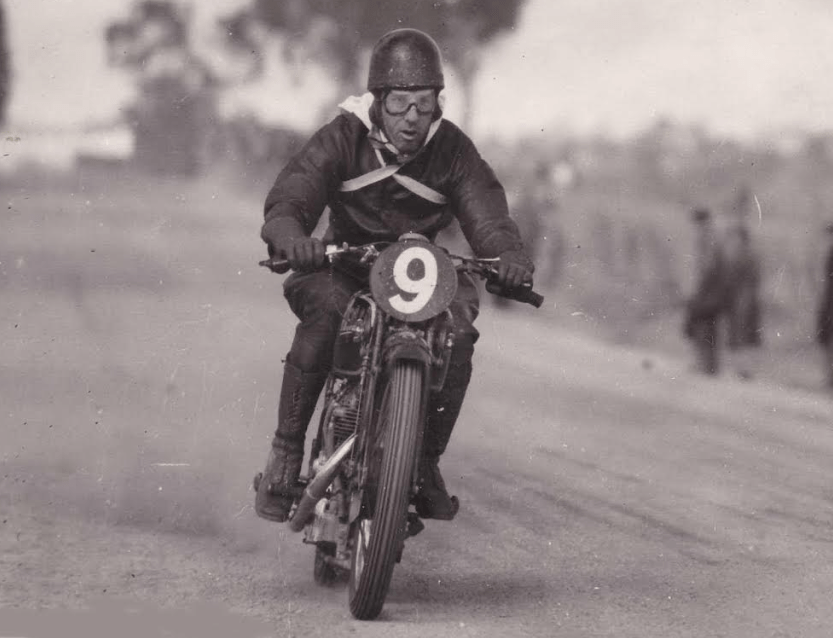

“NEARLY 6,000 PEOPLE filled the Park Hall grounds at Oswestry on Good Friday for the Oswestry Club’s miniature road race meeting. They saw racing by some 70 competitors under splendid weather conditions, although no records were broken and there were only a few thrilling finishes. There were five heats of six riders in the novice event, which, according to custom, was run off as the first item. There is no final for this event, the result being decided on the recorded times of all competitors. C Morris (349cc Rudge) won with a time of 4min 54.8sec; R Brassington (348cc Velocette) was four seconds slower; and H Waddington (348cc Norton) was a further five seconds behind him. The 350cc event produced only one heat that was really thrilling, this being the one in which Roy Evans (349cc Rudge) and Jack Wilkinson (348cc OK Supreme) had a real scrap all the way, Evans finishing under two seconds to the good. This heat was so fast that it not only placed the first two in the final, but FH Worrall (349cc Rudge), the third man, as well.”

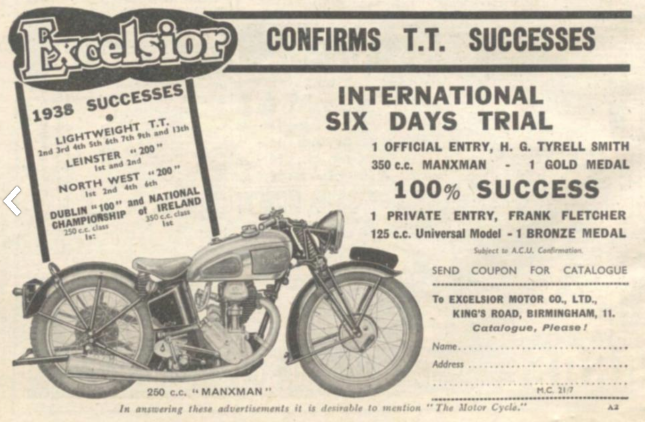

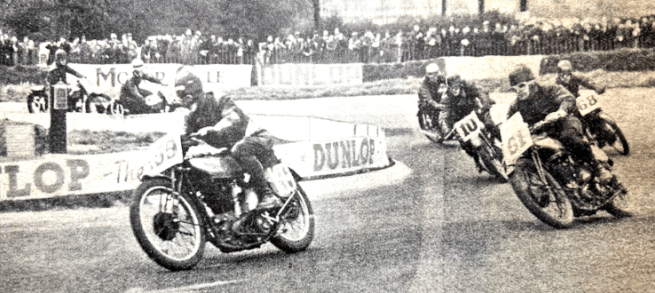

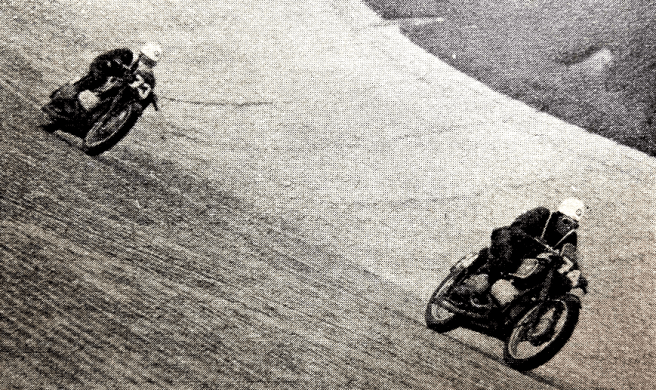

A GLORIOUS morning greeted riders and spectators at Donington on Easter Monday. All roads to the famous track were packed with traffic, and it certainly seemed that a record attendance would be the result. The weather was cold but beautifully bright, and good racing seemed assured. This was the first occasion on which the extended circuit including Melbourne Corner, and the hill approaching it, has been used for motor cycle racing, and, from the outset, it was obvious that speeds would be much higher than on the old circuit. There was an excellent line-up for the first race for 250cc machines, and LJ Archer (New Imperial) set a cracking pace. He was followed by AL Cann (Moto Guzzi), S (Ginger) Wood (Excelsior) and JJ Booker (Royal Enfield). Archer had things all his own way from the word go’, and he piled up a lead which held off all opposition. The positions of the leaders remained unchanged until the very last lap, when, surprisingly, and to the disappointment of everyone, Archer failed to appear. This gave Cann the lead, Wood second place and Booker third place. On their heels came D Parkinson (Excelsior) and R Harris (New Imperial), and, following them, RH Pike (Rudge) and DH Whitehead (Rudge). These two had

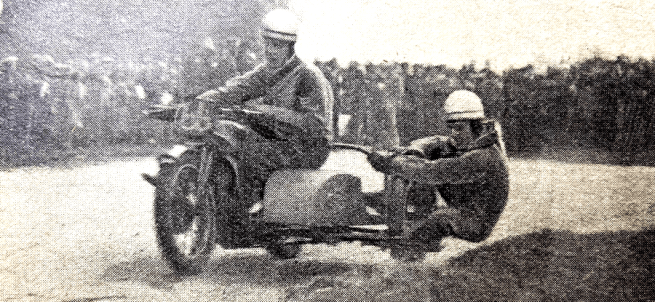

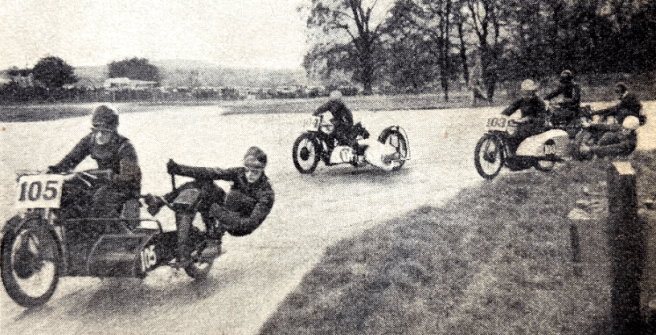

had a lovely scrap all the time and seemed thoroughly to enjoy themselves. Heat 1 of the 350cc race promised well, but it promised nothing like so much as it gave. It was ding-dong racing all the way, with one man, J Lockett (Norton), riding the race of his life to snatch victory in a most spectacular manner from J Moore (Norton) and Stanley Woods (Velocette). At first, Moore dominated affairs and obtained a formidable lead, being trailed by JB Moss (Norton). During the third lap, however, Moore fell at the hairpin, but recovered remarkably quickly. This let Moss into the lead, but Moore soon had it back again. Then Lockett got down to it and did battle royal with Stanley Woods and J Moore. A blanket would have covered these three as they shot down the straight, and it looked as though Stanley would win. But it was Lockett who finished first, with Moore second and Stanly third. There was only three-fifths of a second between the three as they crossed the line! Heat 2 was much slower and was in the nature of a procession, with R Harris (Velocette) leading handsomely all the way. D Parkinson (Excelsior) was second all the time, and the third man, who also held his place throughout the race, was J Sandison (Norton). The leader’s speed in this heat was 66.69mph. The third heat was a spirited event and very well contested. The lead changed hands half way through the race when JRT Upton (Norton) displaced B Gibson (Velocette). On the last lap Upton had a lead of about 100 yards, but Gibson, riding extremely well, reduced this to a couple of yards as the finishing line was crossed. The first sidecar race was uneventful, and although J Beeton (490cc Norton sc) took a commanding lead at first, LW Taylor (596cc Norton sc) was not to be denied. Driving in his usual polished style, he went ahead and gradually increased his lead until he was so far ahead that nobody had a chance of catching him. Beeton held second place for six laps, but was afterwards passed by W Bibby (596cc Norton sc) and WG Tinsley (596cc Norton sc). All eyes were on Stanley Woods when the first heat of the 500cc race assembled. He had already put up the best time in the 350cc race with a lap at 70.75mph. Badly placed at the start, and ninth at the end of the first lap, Stanley had two remarkably fast men out in front of him. They were Maurice Cann (Norton) and J Moore (Norton). Cann set a very hot pace and passed Moore early in the race. Then Moore dropped back, but took the lead again when Cann fell at the hairpin. Stanley was now creeping up until, finally, only Moore was in front, with N Croft (Norton) coming up a good third. In this order the heat finished, with Moore too far in front for Woods to hope to catch him. In this heat Cann put in a lap at 72.02mph. In the second heat J Lockett (Norton) went for all he was worth, and was, in fact, fast enough to relieve Croft of his third place. Lockett’s speed was 68.65mph, and he was chased home by JR Upton (Norton), who averaged 67.26mph. Apart from Lockett’s effort, the heat was not really interesting nor was Heat 3, although the latter was enlivened by the appearance of a Scott, a Douglas and a BMW. The second sidecar race was more eventful than the first one. Once again J Beeton (490cc Norton sc) took the lead, but was closely chased by LW Taylor (596cc Norton sc). AH

Horton (596cc Norton sc) put on a wonderful spurt, and went on ahead of both men. Taylor hung on to him grimly, but Horton was in a winning mood. His passenger lay flat on a padded platform and enjoyed himself hugely. Taylor could make no impression on the leader, but W Bibby (596cc Norton sc) ran past Beaton into third place. It was an excellent race and a close finish, and Horton had reason for congratulating himself on a really stout effort. Several competitors, including. Stanley Woods, JB Moss and M Cann, did not turn out for the first heat of the to 1,100cc solo event. Nevertheless, it was a hotly contested race, with J Moore (Norton) leading from start to finish. In the later stages, Norman Croft (Norton) made an effort, passed H Havercroft (Rudge), and set off after Moore, who was not passed, and Croft had to be satisfied with second place and Havercroft third. In the second heat Lockett again made a great effort, but just failed to come within reach of the first three in the first heat. He went wonderfully well and was miles ahead of his nearest rival, H Taylor (348cc Norton). Lockett’s speed was 69.02mph as against 65.98mph by Taylor, which gives an indication of the effort Lockett made. The third heat was uneventful and not anything like fast enough to cut any ice. All the way through, DL Jones (OK Supreme) made the running and finished ahead of everybody else at a speed of 67.73mph.”

“OPPORTUNITIES FOR THROTTLE-twisting on a flat stretch of concrete do not occur very often in Scotland. It was not surprising, therefore, to find nearly 40 machines entered for the acceleration tests organised by the Renfrewshire Eagle MCC on the private track of the India Tyre Company at Inchinnan. There were 250cc, 350cc and 600cc classes, non-expert and expert, and the only class that was poorly supported was the 250cc non-expert. Each rider was allowed two runs per class. In the 350cc non-expert class J Thomson (Norton) was best with 11.78sec on the first run, but on the second J Weddell (Norton) recorded 11.70sec and won the class. In the 600cc class J Weddell (490cc Norton) made a fast run in 11sec dead, and of the other nine in the class J West (Rudge) was best with 11.46sec. Weddell reduced his time on his next run, with 10.64sec. This time stood as the best recorded until the 600cc experts came on the scene. J Valente (Norton) put up a time of 10.7sec, which looked as if it might win the class. Then came A Marr (498cc Douglas), who cracked along to the tune of 10.15sec—a course record and best time of the day.”

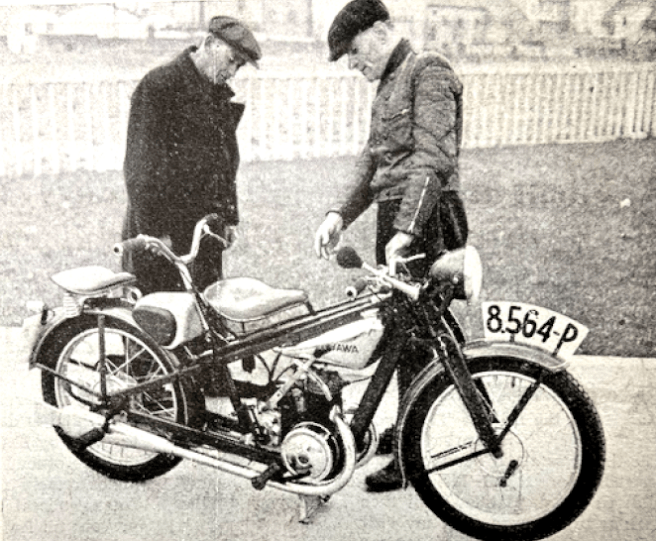

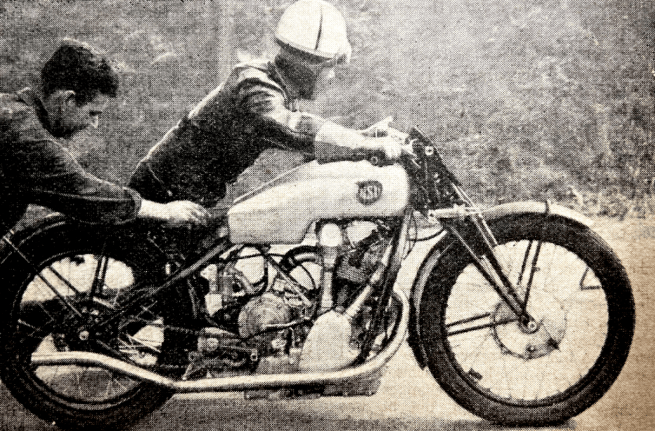

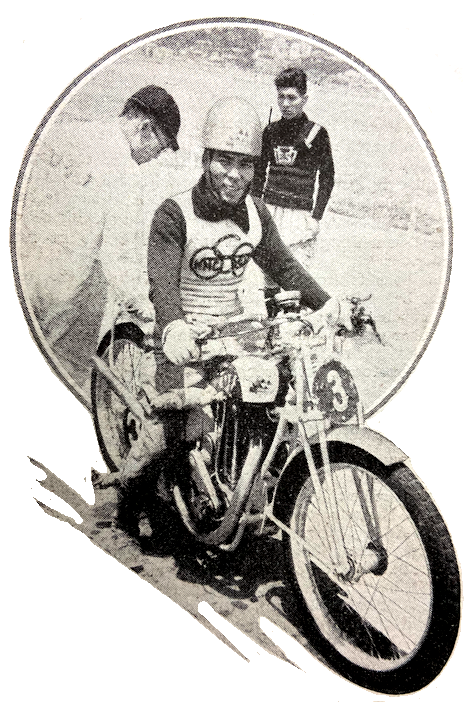

THE MIYATA 175CC TWO-STROKE Asahi, which we last encountered in 1935, had been out and about. Following a gruelling run from Tokyo to Fukuoka it was taken to Manchuria to see how it stood up to operations at -20°C. The military were interested and production topped 150 a month including the Asahi Special with a chromed frame. For the first time Japanese vehicles were exported to the Americas—Asahis were taking to the roads of Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela. Other export markets included China, India, Korea and the Dutch East Indies; company sales reps went as far afield as Africa, Sungapore and Central and North America. On the domestic market Asahi owners clubs sprang up. At which point Japan’s militaristic government restricted motor cycle production and diverted Miyata’s state-of-the-art Kamata factory to aircraft components. Undeterred, Miyata started work on a 350cc four-stroke “joint army-civilian motorcycle”.

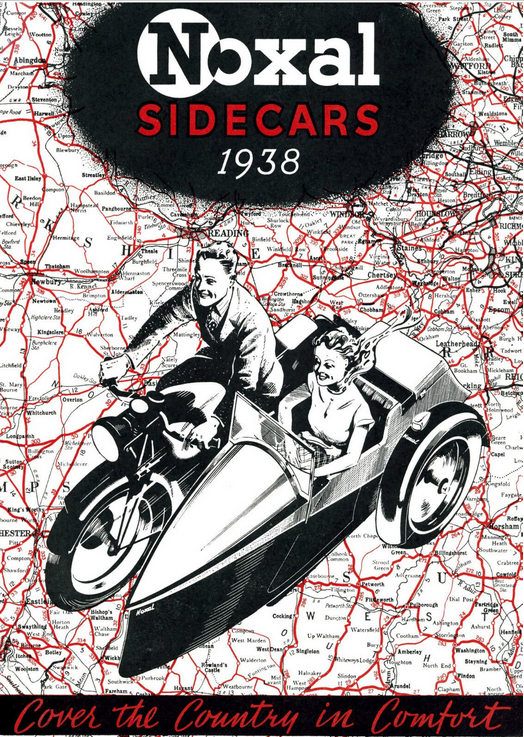

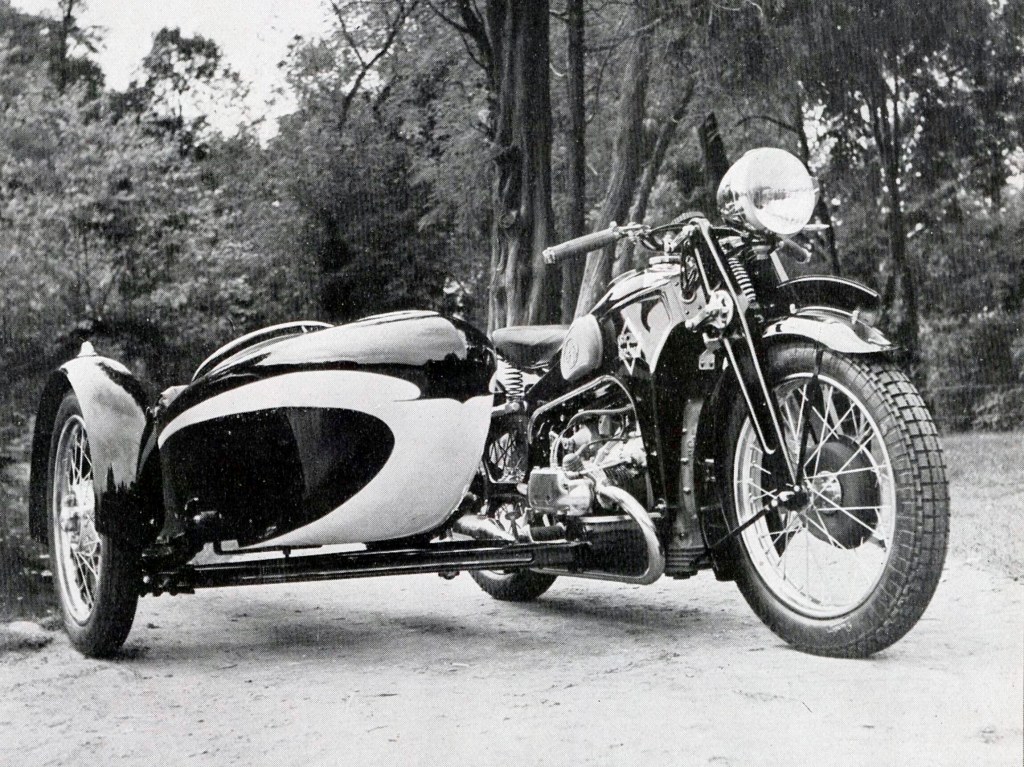

“OFFICIAL REGISTRATION FIGURES just issued by the Ministry of Transport show that the number of new sidecar outfits registered during February was 315, as compared with only 281 in the corresponding month of 1937. The total number of new machines registered during the month was 2,864. Of this total, 313 machines were in the under 150cc class; 800 between 150 and 250cc; 1.374 over 250cc; and there were 315 sidecars and 62 three-wheelers.”

“A TOTAL OF 949 motor cycles was imported by India in the last nine months of 1937, as compared with only 554 machines in the corresponding period a year previously.”

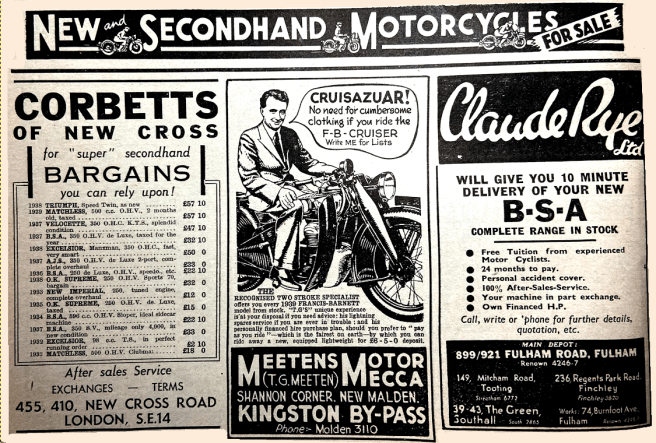

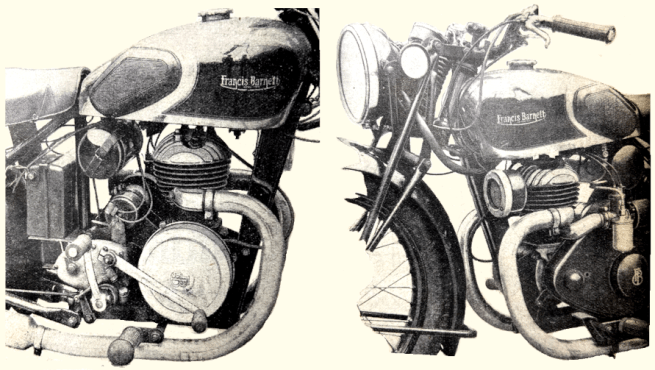

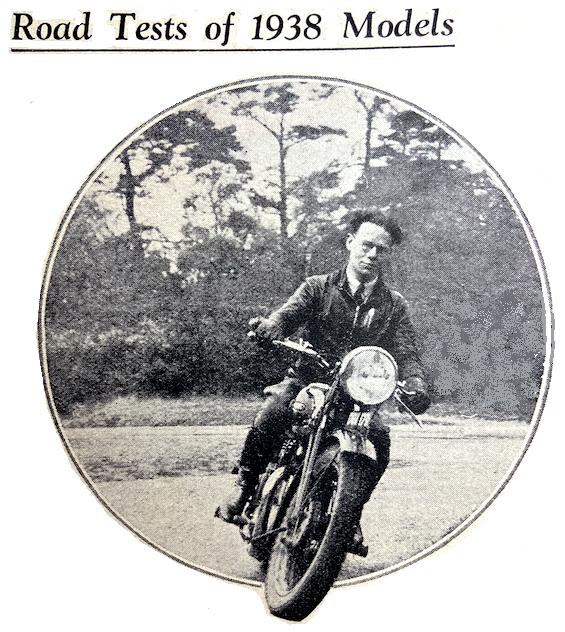

“A ROAD TEST OF THE Francis-Barnett H47 Seagull is especially interesting because the machine has a 249cc Villiers deflectorless-piston engine. Its general performance was excellent; it was flexible, lively, and had a surprisingly good turn of speed. In traffic the machine would run happily at under 20mph in top gear (5.2 to 1), and would accelerate cleanly without the rider having to change down. Unless the engine was pulling, four-stroking would occur at these low speeds in top gear, but this was not unpleasantly noticeable and could be obviated by careful use of the throttle—by closing it when the engine was not pulling. Actually, the machine could be throttled down to 10mph in top gear without snatch, and could be accelerated slowly away from this speed on the level. Out of town the machine could be cruised at quite high speeds, and one of its outstanding features was that it would stand really hard driving for long periods without ‘fussing’ or showing signs of stress. No 1 petrol was used throughout the test, together with oil in the proportion of one pint to two gallons. With this mixture the engine at no time during the test either pinked or knocked. On main-road hills the machine held its speed well, and when the rider was baulked by slower traffic the excellent performance in third gear was found exceptionally useful. In top gear the mean timed speed of four runs over a quarter mile was 60.8mph, and the best speed was nearly 65mph. These speeds were obtained with the rider sitting on the carrier and streamlining himself along the tank, but even so they are very creditable. Throughout the maximum speed tests and during the acceleration tests the machine behaved splendidly, and at no time did it show any signs of drying-up.

During one of the acceleration tests the air-filter on the carburettor intake worked loose. Acceleration from a standing start was very good indeed, the machine on each occasion reaching 57mph at the end of a quarter-mile—only 3mph short of the maximum. Consumption of petroil at a steady 40mph worked out at 65mpg. As is to be expected with a modern two-stroke engine, starting was extremely simple. After closing the air slide and flooding the carburettor, one dig on the kick-starter was sufficient to start the engine when cold. It was found important to keep the throttle nearly closed when starting the engine under these conditions. When the engine was warm it was merely necessary for the rider to push down the kick-starter gently, when the engine would immediately fire. Mechanical noise was not noticeable at any time, and the exhaust note, while healthy at wide throttle openings, was never unduly obtrusive, and under traffic conditions was pleasantly subdued. So much for the engine performance of this excellent little machine. The word ‘little’ is used in the sense of lightness only, for although its total weight, fully equipped, is only 254lb, the machine has that solid feel associated with much heavier machines. The road-holding, even at high speeds, was excellent. The steering damper was not found necessary at any time during the test, and the steering always gave the rider an immense feeling of safety. On bad roads the front forks dealt efficiently with road shocks, and the rear wheel was not inclined to hop. On fast corners the machine was rock-steady and could be leant over as far as the footrests allowed with perfect safety. At low speeds the steering was positive without being heavy, and no great skill was required to ride feet-up at less than walking pace. This feature, combined with a good steering lock, made the machine extremely pleasant to handle in dense traffic. Ease of control is, in fact, one of the many pleasant features of the Francis-Barnett. Only three of the four controls on the handlebar are used at all frequently, for the air lever is required only when starting from cold. These controls were light and smooth in use. The clutch was particularly pleasant, being positive and at the same time very sweet when taking up the drive. Both brakes were well up to their work and were pleasantly ‘spongy’. Either would hold the machine on a gradient of 1 in 5, and used together they would bring the machine to rest from 30mph in 42ft. The positioning of the footrests, handlebars and saddle is good, for although the Seagull is a small machine it will accommodate a tall rider comfortably. The handlebars give a natural, low position for the rider’s hands and arms, and the saddle is high enough to allow a comfortable leg position. One criticism can be applied to the position, viz, that the rider’s leg is inclined to foul the carburettor. Obviously the makers have given a good deal of thought to the Seagull. The machine is not expensive, yet the equipment includes a 6-volt lighting set, four-speed gear box with foot change, three-gallon fuel tank, and a carrier. To sum up, the machine is easy to handle under all conditions, has a good all-round performance, and useful maximum and cruising speeds.”

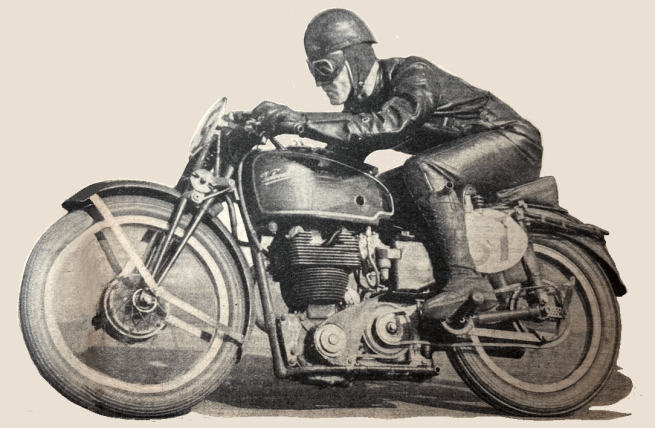

“IT IS WITH THE DEEPEST REGRET that Motor Cycling records the death of Eric Fernihough, who was killed at Gyon, in Hungary, on Saturday last when attempting to regain the world’s motorcycle speed record on his supercharged Brough Superior. At the time of going to press details of the tragic accident are still vague. All that we know is that when travelling in the region of 170mph the machine suddenly swerved off the road and catapulted Fernihough over the handlebars. He was rushed to the University Clinic, but died without regaining consciousness, of a severe fracture to the base of the skull. And so passes a brilliant rider-tuner, who has done more than any other individual to keep the British flag flying right at the top of the record-breaking sphere.”

“GREAT BRITAIN HAS SUFFERED a most grievous loss, for Eric Fernihough, her fastest motorcyclist, is dead. He met his fate in Hungary whilst striving to regain for his country the ‘World’s Fastest’ motor cycle record. Thus ends an heroic struggle against apathy and adversity, for ‘Ferni’ fought a lone battle against the organised might of Continental countries. Fired by the flame of a burning patriotism, his life was dedicated to the furtherance of British motor cycling prestige. And now that life has been sacrificed. But it has not been sacrificed in vain, for although Fernihough the Man has passed on his name will be handed down through the generations of motor cyclists to come as an example of all that is best in sportsmanship. Denied by his own country the use of a suitable road, financial assistance or official recognition, Fernihough did not despair. A Crusader in the true sense of the word, he spared neither himself nor his substance in his endeavours to make Great Britain supreme, his only reward the unstinted praise and admiration of his fellow motor cyclists. In victory or defeat he remained always the perfect sportsman and a most worthy ambassador for his country. He will be hard to replace, but British history records that the sacrifices of her sons make the heroes of to-morrow, and the man will be found who will don the armour of that very gallant gentleman Eric Fernihough. Whilst we convey to his widow our sincere sympathies, we are proud to write beneath his name the epitaph: ‘Killed in action in the service of Great Britain.'”

ROLLIE FREE WENT to Daytona to pick up a number of US records, including a 111.55mph run on an Indian Chief he tuned himself.

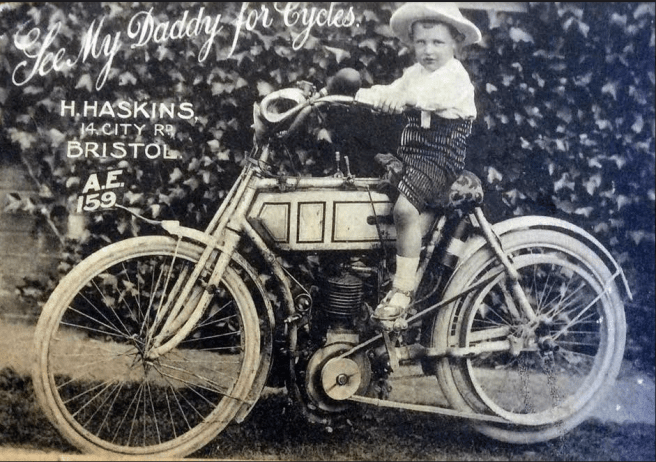

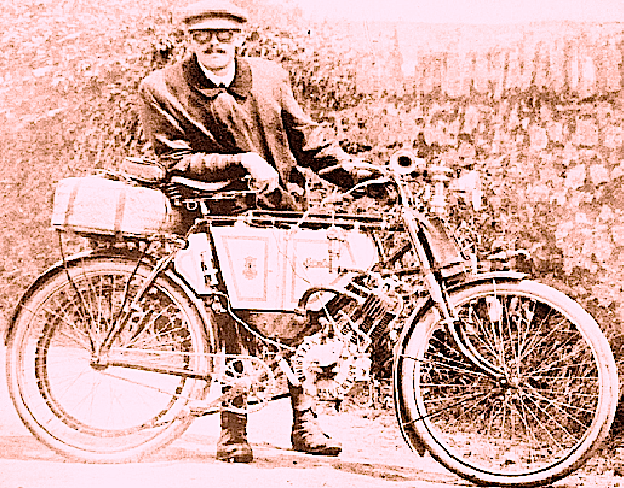

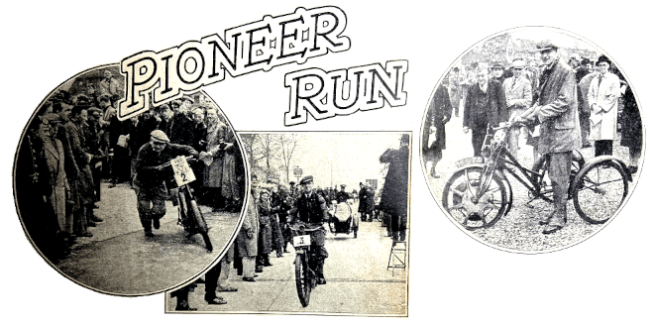

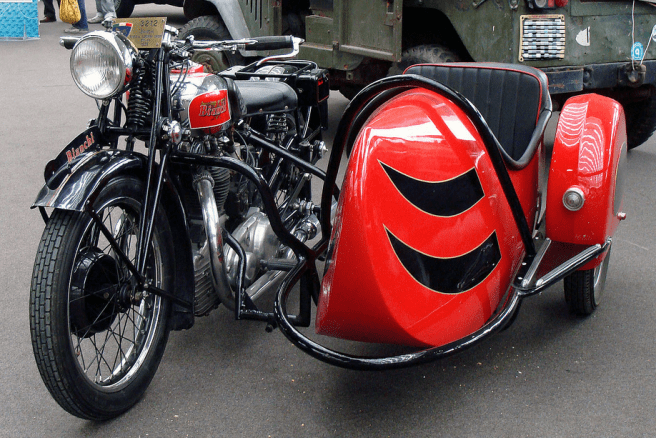

“CROWDS CAME FROM far and near last Sunday to watch the Ninth Annual Sunbeam MCC Pioneer Run pass by…not one of the machines among the 38 entrants was built after the end of 1914, and, in fact, eight of them were built prior to 1905. Of the ‘pre-1905’ models two did not even belong to the present century. The route lay from Tattenham Corner, on Epsom Downs, to the Devil’s Dyke Hotel, in Brighton’s hinterland, and passed through Reigate, Crawley and Bolney. For those machines built later than 1904 the whole run had to be carried out non-stop, but in the cases of the earlier mounts, the ‘non-stop section’ finished at the famous Pylons, a few miles before the Devil’s Dyke. The regulations, while permitting no adjustments en route, allowed the older machines to refuel without penalisation in consideration of their diminutive tanks. Each rider was accompanied by an observer, mounted on a modern machine, whose job it was to record the progress of his companion. The scene in the starting paddock on Epsom Downs would have brought joy to the heart of any old-timer; wondering groups stood around almost every ancient model while the ‘phut-er-phutter-phut’ of the aged engines, wheezily struggling for breath, would have struck music in his ears. The comments of the crowd were varied but nearly always appreciative. They would gaze at some spidery, high and flimsy machine, built long before many of them were born, and admire the skill and pluck of those who had ridden them in those far-off days of bad roads and public prejudice; then they would express wonder at the sight of an elaborate motorcycle incorporating many of the details in a specification which they, themselves, long for, but which is denied them, even to-day—the handiwork of some long-forgotten engineer whose ideas had been too far ahead of his time…For example, there was S Jess’s 1912 Wilkinson combination, an 800cc outfit having a water-cooled straight-four engine, shaft drive and a spring frame—a specification which, to-day, could be called ultra-modern. The oldest mount there on Sunday was Rex Judd’s 990cc ‘opposed-four’ Holden, built in 1898 and having its crankshaft in the rear hub! The runner-up for longevity was a beautifully kept Ariel tricycle, circa 1899, entered by EA Marshall, which had a water-cooled head. Other interesting mounts included C Bullen-Brown’s 1902 Clement-Garrard—a real lightweight of 142cc—the 1901 Singer tricycle ridden by NCB Harrison and having its 200cc engine mounted in the front wheel, the 1914 unit-construction Calthorpe entered by HR Nash and ridden by CK Mortimer, and CR Southall’s 1912 AC Sociable, which he drove all the way down from Birmingham. Another rider who came a very long way to compete was Norman Cox, who brought his 1912 Triumph from Yorkshire. The weather, as is usually the case where a Sunbeam Club event is concerned, was eminently suitable for the occasion, for, although no rain fell, the temperature was low enough to help the doubtful cooling of the old machines. At a minute after 10am, No 1, C Bullen-Brown, pushed off his Clement-Garrard and began his run to Brighton; next the Holden ‘four’, Rex Judd up, went into action, and very queer it looked, its tiny big-ends twinkling round each side of the back wheel as it got up speed. And so the veterans began their task and not one of those who had arrived failed to start. C. NV. Rowe’s 1914 NUT twin sparkled in new paint and plate and hummed along with scarcely a sound: both he and FW Clark (1911 Scott) forced the pace up to between 50 and 55mph, and soon discovered the poignant truth that, except for short stretches, the speed of pre-war machines is still much too high for 1938-pattern roads! NCB Harrison (1901 Singer) had a warm time, notwithstanding the weather, for when he was not pedalling to assist his unwilling pair of horses, he was extinguishing the flames which frequently threatened to engulf his machine. Being without pedals proved a severe handicap to Rex Judd (1898 Holden), and he had to assist his Victorian model in scooter fashion until one shoe was nearly worn through. Nevertheless, he got to Brighton with only one unofficial stop, to refill his water tank. In remarkably few cases did Anno Domini take full toll, and one of the real hard-luck retirements was that of HW Bullock, the rear-wheel bearings of whose 1909 Triumph disintegrated although his engine was full of ‘urge’; then another machine of the veteran Pioneer supporter, HE Cooke (1902 Kerry twin), whose magneto gave out. Cooke, incidentally, was the only ‘pre-1905′ entrant not to finish. Such bothers as belt-slip, due to oil getting on to the drive, stuck valves and choked fuel supplies caused most of the few stops which occurred, and one could not help but he impressed by the reliability and speed of the competitors’ machines. The first man to arrive at the finish was FW Clark, whose aged Scott, followed by a yowling string of its descendants, had clipped off the run in 61 minutes!”

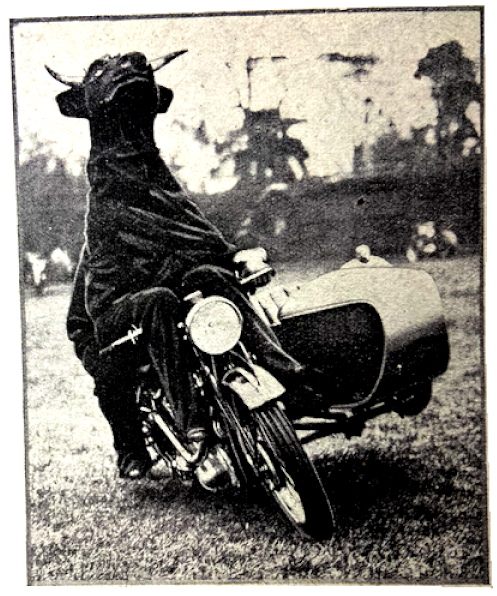

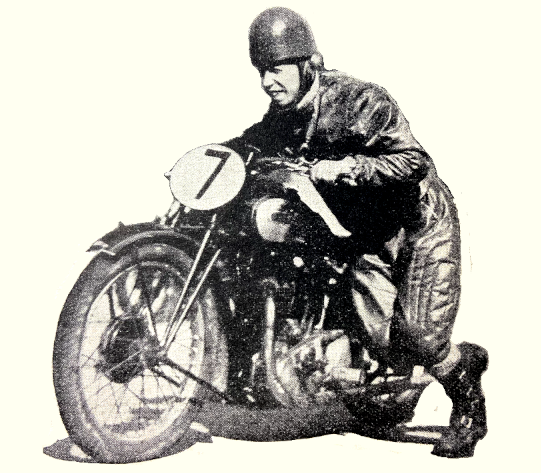

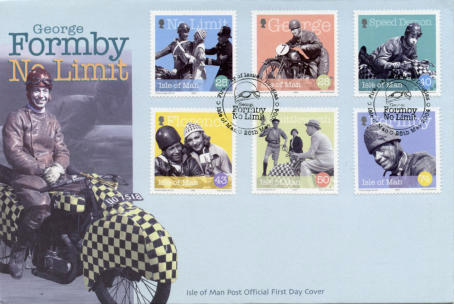

“WHEN NEXT YOU SEE, in gleaming lights, that famous name ‘George Formby’ glowing on the front of your cinema theatre, take more than a film fan’s interest because it is the name of a real, keen motorcyclist like yourself; it is the name of a man who, despite the fame which outstanding talent and originality have brought him, still hankers after the thrill of a fast 500, and would like nothing better than a day’s tinkering with an engine. At the top of his profession, George Formby, who has achieved that aim of all theatrical folk, to appear before our King and Queen, holds dearest his memories of the days when, riding a not-too-good side-valuer, he travelled from theatre to theatre doing his ‘shows’—and he still thinks that the best way of getting about town is on a solo. I found George in his dressing-room at a well-known London theatre, and the fact that I had come to talk to him about motor cycling ensured me a war and rapid reception. As a matter of fact, I gathered that he had put off one or two other visitors who had been worrying him for interviews. Before I had a chance to ask him questions George was putting me through quite an inquisition about the model I used; what was this trial or that trial like; had I seen So-and-So or What’s-his-Name lately, and it was quite a while before I could get him to talk about himself. Naturally we discussed that marvellous TT film of George’s—No Limit. What motor cyclist has not seen it, or at least heard all about it from enthusiastic friends? I won’t attempt to reproduce George’s broad Lancashire accent—suffice it to state that when you hear him on the air, or on a record, or in a film—well, that’s the way he talks in real life ‘and no kid’. “Do you know,” said Formby, “I’d have played that part for nothing—just to have a ride on a fast machine on the actual TT course. I’d have liked to have entered the race in reality, but as I can’t do that, well, I did the next best thing. When the producers were looking for a subject for a film in which I was to star they asked me what I thought. So I told ’em that nobody had ever filmed a TT race. They fell for it at once, so we got in touch with the Manx Club, obtained their advice on details, and we found their help invaluable. Particularly did we have to thank the Howell brothers, who rounded up all the fast riders in the Island for group shots. The IoM people were fine and gave us all the help they could. Where necessary, we used shots taken in the 1935 Senior race, when Stanley Woods won on the Guzzi at eighty-four-six-eight, but we actually used very few of these. As a matter of fact, we found that the real racing didn’t have enough crashes to suit us, so we had to stage a few for good measure! To fill the grandstands, we got a crowd of holiday-makers from Cunningham’s Camp to come along, and didn’t they enjoy themselves! Between shots we kept them amused with music and distributed lunch baskets, for we had them there all day long.” I asked George whether he had used a ‘double’ for any of the fast-riding scenes. He was scandalised. ‘What!’ he almost shouted. “Me use a ‘double’ for motor cycling? I’d have crowned anybody who had wanted to ride my bike! As it was, an ‘extra’ borrowed it, went too fast, scared himself out of his wits and ran into a car. He bent the model so badly that we had to send to Birmingham for another!” George’s face was amusing as he registered the horror which he had, evidently, felt when his pet machine had been reduced to scrap in his absence. I sympathised with him, for I have had a similar experience…Like most laymen, I held the opinion that much of what we see in films is faked, and asked whether there was any faking about No Limit. “Practically none at all,” said George. “A dummy or two was used when really serious crashes wore shot, but, for instance, when a machine ran on the bank, burst into flames at the top and came down ablaze, that model was well and truly burnt out. We saturated it in petrol and sent it up the bank where a couple of men were hidden at the top with torches.

They touched it off, so that when it came down it was burning like a bonfire. On the other hand, we had several unrehearsed incidents which we kept in the film. There was one, which very nearly brought my career to a sudden and definite finish. You remember how, when I am supposed to be flat-out, you get, a close-up of the front of the machine and I let go with one hand to wave to a girl in the crowd—Florence Desmond, of course? Well, we obtained those shots in this way. We used a very special fast car with the camera at the back; behind them trailed a cable with a white disc at the end. I had to keep my front wheel just behind that disc so that the cameraman could keep me in focus, and in that fashion we marched along with the throttle very near full open. When the time came for me to wave to Florence, I went just a shade too fast and my front wheel went over the disc…I had only one hand on the bars and, of course, when the disc got under the wheel it pulled it out of the straight and let me in for the father and mother of a wobble…! I don’t know now how I saved the plot, but when we saw the shot it was so realistic that we made use of it.” There was one thing which he told me about the TT film which, more than anything else, impressed me with the seriousness and painstaking care with which it had been produced by Mr Monty Banks and his merry men. It concerned the finish, when George pushed his machine over the line to win by a split second before the ‘villain of the piece’ flashed by (‘Ah-ha! Foiled again!!’). It seemed that, in order to get just the right effect, George had to run from Governor’s Bridge to the stands—nearly a quarter of a mile, in full leathers and pushing his heavy 500—no fewer than seven times before they got the shot they wanted. The rival would either be too far ahead or too far astern at the line—it was all a matter of timing, and everybody, George included, wanted to get it right, whatever it cost in perspiration. Apart from his famous TT film, Formby has done a lot of motor cycling, including racing at Southport. Since 1920 he has owned an amazing number of different machines, ranging from a 1913 hub-geared Humber, on which he taught himself to ride and which he bought for £20 and hotted up so much that he ‘burst’ it, to a ‘very, very’ Ulster Rudge, on which George distinguished himself at a grass-track meeting near Burnley, Lanes, by winning several races and put up the fastest time of the day. On another occasion he rode at Post Hill. Other models which Formby has possessed at one time or another include a 350 Blackburn, a Matador (remember those sleek little red motors?), a Levis, an Ivy, a Royal Ruby, an OK-Villiers, a Francis-Barnett, a brace of sv AJSs, a Rudge Multi and a Zenith Gradua, a Harley-Davidson (with a cut-out which George used to keep off dogs), a 7-9 Indian, the first ‘Riccy’ Triumph to appear in Warrington and to which he fitted a sidecar, a very quick ohv Douglas, a long-stroke Sunbeam and a twin NUT. That a solo motorcycle is the best wear for town travel is George Formby’s firm conviction and, to quote the words of this experienced rider: “The vulnerability of the motor cyclist that we hear so much about is, I think, mostly eyewash. If you handle your machine properly you should never have a crash and, if you do, the chances are that you will be chucked clear. Which fact, to a great extent, cancels out the much-vaunted ‘security’ of a car, where you are boxed in.”

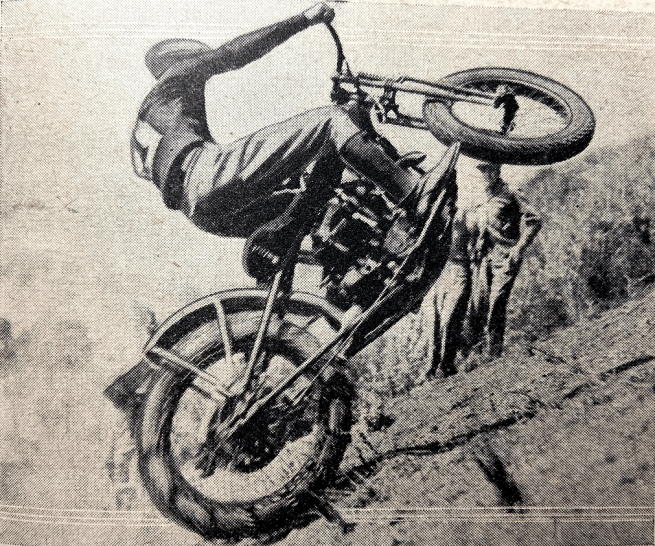

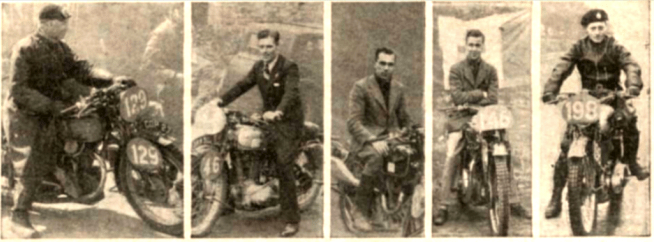

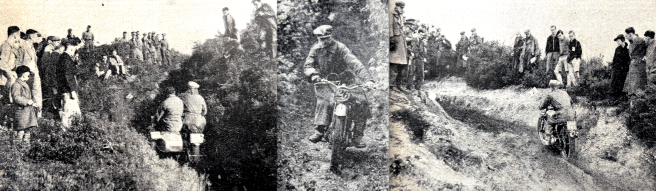

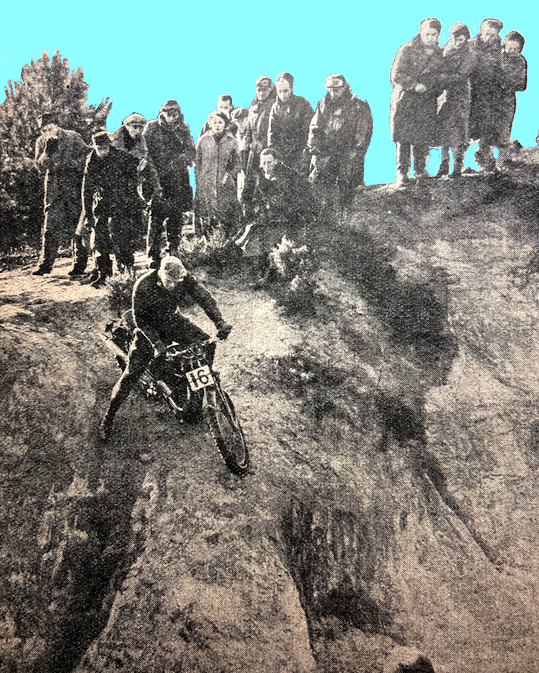

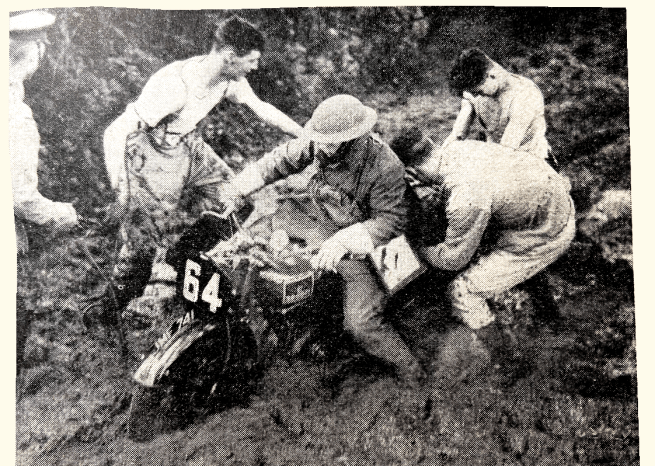

“THIS YEAR’S ILKLEY Grand National was rather a disappointment as a super-sporting event because the prolonged spell of dry weather had taken all the sting out of the course. Compared with last year’s event, however, there is no doubt that the competitors much preferred last Saturday’s conditions, for in 1937 it rained in torrents all the time and the course was feet under mud in places. This year mud was conspicuous by its absence, but the Ilkley &DMC officials managed to introduce enough ‘trickery’ into the circuit to cause everybody to lose marks—even the winner, Ken Wilson (498cc Matchless), lost as many as 25. The starting and finishing point was the Royalty Inn, on Chevin Top, overlooking Otley, and the circuit of some 20 miles had to be covered three times. It embraced a number of well-known sections, commencing with Danefield Steps and Pool Crags, which had to be descended on the first circuit and climbed on the last lap.”

“SOAP CAN BE a useful means of finding top dead centre. Screw an old plug body into the plug hole and bring the piston to the top of the cylinder on compression stroke. Smear a film of soap lather across the top of the plug body and rock the crankshaft so that the bubble increases and decreases in size, the maximum bulge on the bubble indicates TDC.

Dudley W Hearn.”

“HUNDREDS OF BABIES. Three hundred and thirteen machines of under 150cc capacity were registered during February. This compares very favourably with the figure of 252 recorded for the same period last year.”

“A CARBURETTER(OR) MATTER. The question of the alternative methods of spelling the word ‘carburetter’ has been causing a certain amount of heartburning to a number of entrants in Motor Cycling’s latest competition. To clear up the matter, competitors can rest assured that the word in dispute has not, and will not be used in this connection.”

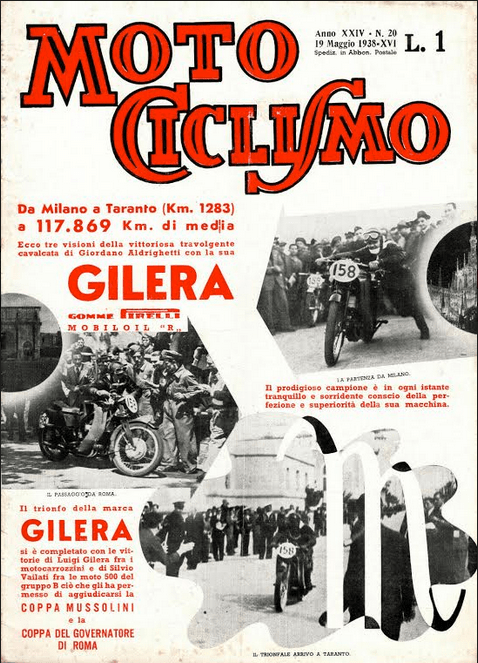

“AUSTRALIAN TT RACES. Norton machines occupied the first and second places in the Australian Junior TT and first, second, third and fourth places in the Senior event.”

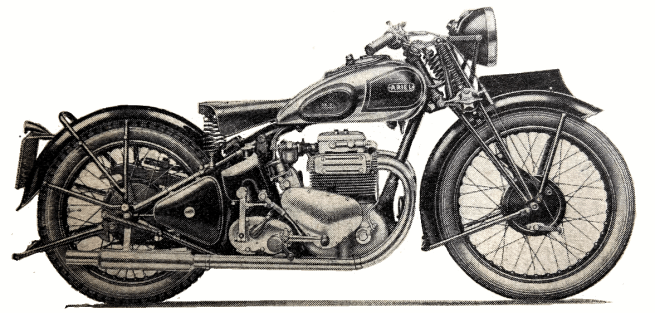

“IN THESE DAYS OF ultra high-performance motor cycles it is apt to be forgotten that most manufacturers list a model or models intended purely for touring use. One of the best machines of this type, a 350cc ohv Model NG Ariel, has just completed more than 1,000 miles in the hands of Motor Cycling’s testers and it proved itself a most likeable and pleasant mount. Many machines of various makes have earned reputations for their individuality, and this Ariel should definitely have a place in this class. Its characteristics are comfort, quietness and a wonderfully docile power unit. The Ariel at once gives an impression of smartness. It is finished in black and chromium and the work is excellently and thoroughly carried out. The power unit is neat, the valve gear and all moving parts being totally enclosed, and there being a minimum of external ‘plumbing’. Seated in the saddle, a rider of average height is given a feeling of complete control and comfort, the body being practically upright when the hands are resting easily on the handlebars. One small detail criticism relates to the footrests, which were placed rather high and when adjustment was attempted it was found that the offside rest could not be lowered any further owing to the position of the exhaust pipe. Starting was a feature of this 350 which cannot be too highly praised. Almost without exception one kick was sufficient to get the motor ticking over quite easily and slowly. When the engine was warm no particular care had to be taken of the positions of the controls to obtain this very fine starting, but when cold it was found that the best results were obtained with the magneto about one-third retarded and the air lever fully closed. Very little throttle opening was necessary and, in fact, it was best to keep the twist grip nearly shut for a moment or two after the engine had fired, as otherwise it might ‘fluff out’ if the throttle was immediately opened. The controls, which are of the grouped type, were all very well placed, and the clutch was delightful—smooth and light in action. The exhaust valve lifter and the magneto control are of the lever type mounted together on the left handlebar.

When under way the machine was found to be delightfully controllable; it steered well and could be placed just where it was required, and for pottering about in London traffic this ease of handling was much appreciated. On the open road, too, the general handiness of the Ariel was remarkable. It is not intended to be a sporting mount and, in consequence, the engine performance is not outstanding, but the road holding and cornering at cruising speeds made it easy to put up good averages over long distances. As a touring mount this 350 Ariel lacked none of the qualities which are so desirable for this class of riding. The engine would pull quite comfortably at a very low rate of rpm and at times gave the impression that it was more like a side-valve than an ohv in this respect; on the other hand it had real ohv acceleration. For the rider of an exploring turn of mind the handling on real colonial going would inspire confidence and it is here that the trials breeding for which Ariels are famous is demonstrated. Through thick mud and over rutty lanes the model could be handled with ease without any need for foot slogging, and the tester formed the opinion that, fitted with a couple of competition tyres, this would be an excellent go-anywhere mount for the countryman or for colonial use. The actual maximum speed proved to be 65mph, which is a very reasonable figure for this type of machine. At this speed it was found advisable to have the steering damper in action, and over rough surfaces a certain amount of fore-and aft pitching was noticeable. Nevertheless, fast bends could be taken flat out with a perfect feeling of security on ordinary surfaces. When dealing with performance the matter of brakes immediately comes to mind, and in this department the Ariel was far above the average for its class. The anchors were really awe-inspiring in their efficiency; not only would they stop the machine in a very short distance but they would do so without any fuss or bother, smoothly and powerfully. Really hard pressure on the front brake lever would make the front tyre squeal on a dry tarred road, and although the rear wheel could be locked by heavy pressure it was possible to tell to a degree when this would happen, with the result that the maximum braking efficiency could always be utilised. The excellent arrangement of the controls has already been dealt with; but the machine has a tank-top instrument panel and the speedometer is mounted here. In this position it was rather difficult to keep a constant check on one’s speeds as it was awkward to look quickly from the road in front to the instrument mounted almost between the rider’s knees. The gearbox was pleasant and quiet, and the foot operating lever required a very short movement to effect a change of ratio. In third gear (7.3 to 1) a maximum Of 55mph was obtainable, but at this speed the valves were commencing to bounce. In the second ratio (5.7 to 1) a maximum of 41mph was reached. These speeds were obtained with the rider crouching down in the saddle. At all times the exhaust note was very subdued, little more than a burble emanating from the twin fishtails whether the throttle was opened wide or the model just touring along at a leisurely pace. Because of this very high degree of exhaust silence a certain amount of mechanical noise from the tappets could be heard, but the transmission and timing gear were quite quiet. Incidentally, the fishtails project well to the rear of the machine, and some care is necessary when lifting the model on to its rear stand to avoid getting one’s legs in the way as the machine comes back. Riding at night behind the large-diameter Lucas head lamp was very pleasant. The beam given was well diffused and had a very long range, and the dipping switch on the left handlebar was in such a position that it could be operated very easily. Some long night rides were undertaken, and it was found that the average speeds were very little below those attained in broad daylight. Economy of fuel consumption was a good feature of this Ariel. For country running it was possible to cover approximately 85 miles to one gallon of No 1 fuel, and for town work approximately 70 miles. In this connection, although the motor would run very well on any standard fuel, it seemed to prefer one of the Ethylised brands, and with this type of petrol in the tank it was practically impossible to make the engine pink, however ham-handed the rider was with the throttle. The consumption of oil was not quite up to the same standard, as one gallon was required approximately every 1,100 miles. This may be in part due to the fact that there was a certain amount of leakage from the oil-pipe unions on the timing case, and also that lubricant seeped out in small quantities from the rocker housings and the oil-bath primary chaincase. The chains themselves were well supplied with lubricant and did not require any adjusting whilst the machine was in our possession. Most of the adjustments of the various components were found to be readily accessible, but it was difficult to get a feeler gauge between the rocker and the valve stem to measure up the actual clearances. This was due to the fact that the screw-on cap did not allow of sufficient room for the feeler gauge to be inserted. The detail work throughout the machine is excellently carried out and the manufacturers must be congratulated on producing a really first-class de luxe 350 with a good performance, excellent handling and a docile and pleasant motor for the very reasonable figure of £55 10s.”

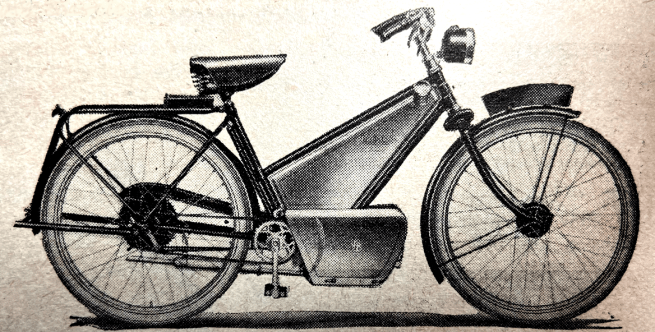

“THE RECENT ARTICLE on motorised cycles reminds me of some interesting details I have collected. I get a great deal of fun out of studying the various aspects of motor cycling and the potential use of the motor cycle to the ‘world’s workers’. I made a dip check of some 300 members of the BMCA, as to the occupations of the riders. There were 66 different occupations concerned. Some were plumbers, fitters, builders, electricians and decorators. Clerical workers were also prominent, not omitting labourers, whilst secretaries, school teachers and shop assistants occupied a ‘place of honour’. There was another group of people whose normal occupation is that of professional transport men, such as chauffeurs, taxi-drivers, lorry and bus drivers, and the like. The old doggerel comes to mind, ‘Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Sailor’, when you consider ‘motor cycles with pedals’, which may well be the best friends of every worker and indeed of professional men like doctors and parsons. I profoundly hope that the manufacturers will produce the goods and ‘tell the world’ and, in spite, of the Jeremiads of the industry, there will soon be 1,000,000 registered motor cyclists in Great Britain. The process is that of graduation; that is, a gradual step from the pedal cycle or the pedestrian to a small motor-cycle, followed by the graduation to the large types of motor cycles. Upon the success of the graduation process. the makers of small-type machines will get customers from the recruits and pass them on to the famous makers of the 500s and over, who over a period of years have expended great energy and expense in making the British motor cycle pre-eminent in the World and deserve to reap a rich harvest. Make Great Britain ‘motor cycle conscious’ and you will make her fitter and more efficient.

SA Davis, Organising Secretary, BMCA.”

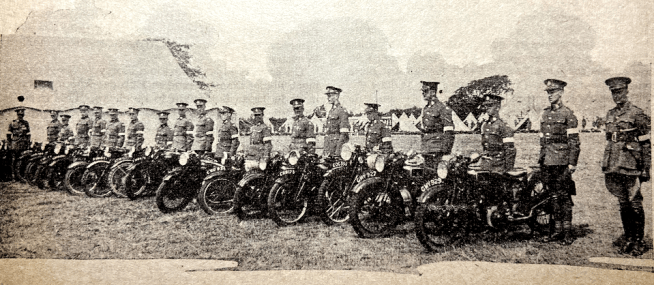

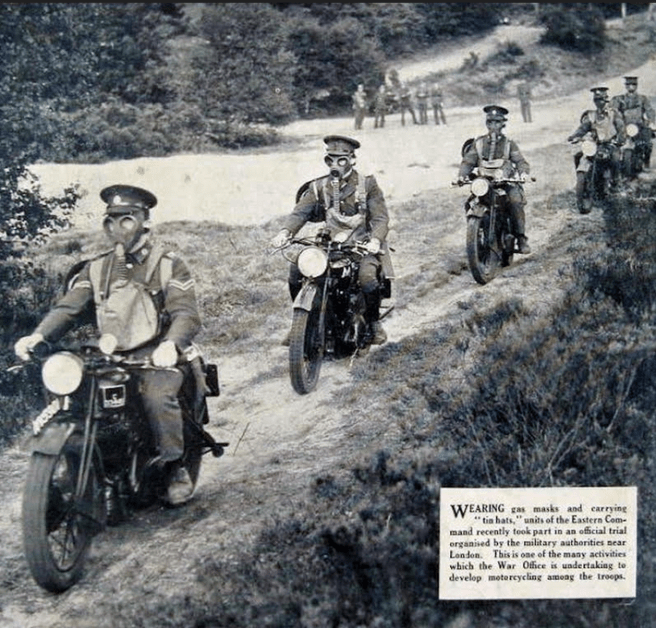

“THE MUSINGS OF A Mid-Victorian Magistrate. When fining an 18-year-old motor cyclist at Epsom recently, the Chairman of the Bench said: ‘Anyone who gives up motor cycling is to be commended.’ This statement, coming from a man in a privileged position, at a time when the Army, the Territorials and the police are appealing for motor cyclist recruits, is nothing short of amazing. A prejudiced remark of this nature can hardly imbue motoring technical offenders with a respect for the justice to be anticipated from the bench of this horse-conscious township. It is the duty of a magistrate to dispense the law; he is not entitled to interlard his findings with his personal and irrelevant opinions. Presumably he has forgotten the services rendered by motor cyclists in 1914-1918. There may yet come a time when the Chairman of the Epsom Bench will have cause to be grateful for similar services. Whilst we cannot commend his common sense, we can only hope his legal decisions are wiser than his published comments.”

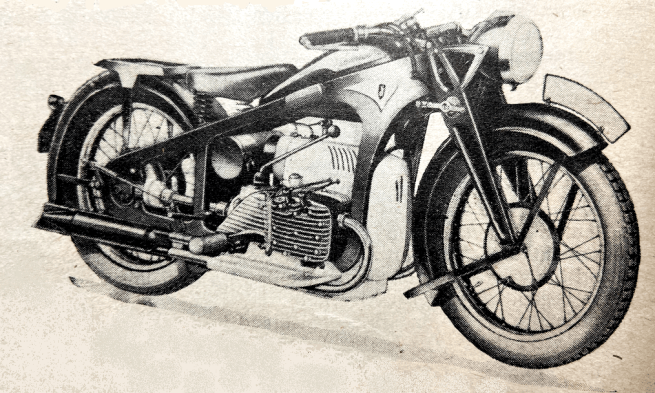

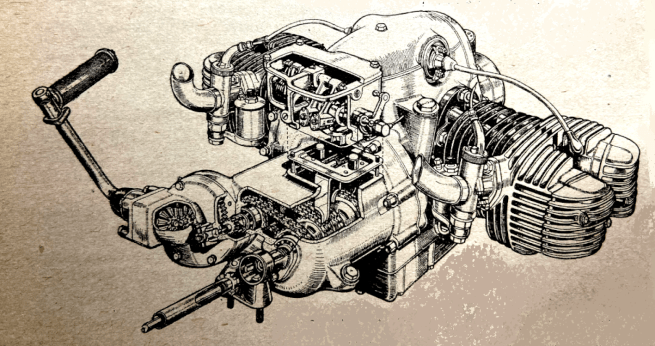

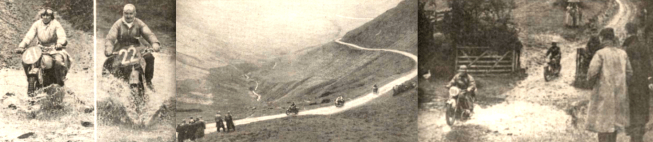

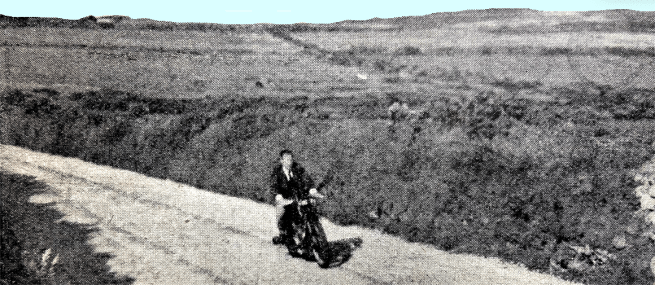

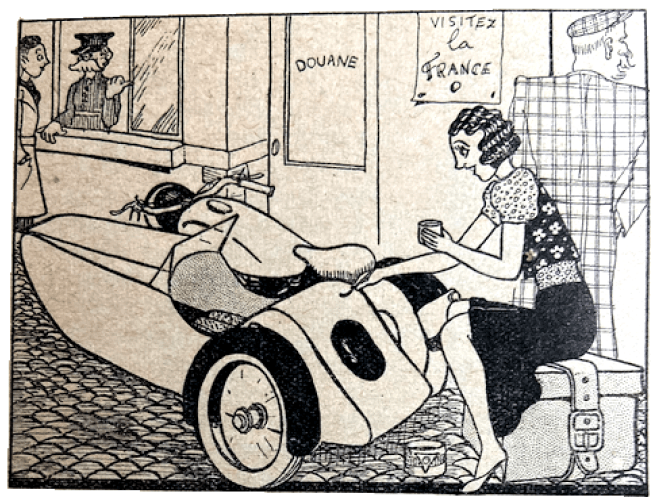

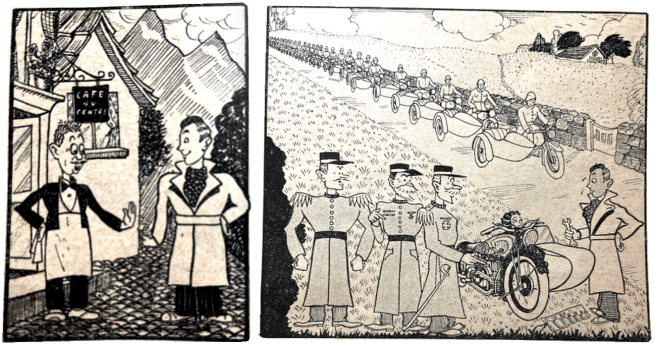

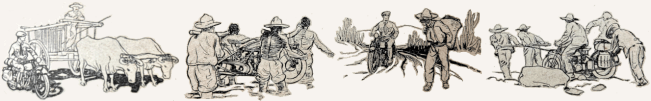

BELGIUM, THE NETHERLANDS AND GERMANY jointly organised what Motor Cycling dubbed the “International Three Days”. Out of an entry of 150, 108 were Germans. They took on 24 Dutch and 14 Belgians; teams for the “International Challenge” comprised three solos under 500cc and an outfit under 750cc.Most of the Germans were riding BMWs but one team was evaluating DKW 250 solos. There was no British team but Green ‘Un correspondent PS Chamberlain hitched a lift on Joe Heath’s Squariel/Watsonian outfit that was one of three British entries. They joined Gordon Wolsey (Triumph Speed Twin) and Jack Garty (350cc Ariel). Chamberlain reported: “Arrived at Spa, we were well looked after by van Maldegem, who drove a Norton sc in the last Llandrindod ‘International’, and has been the moving spirit in the Belgian part of the organisation, found our pension, and renewed acquaintances with German and Dutch friends. Next day the little town of Spa, familiar to English racing men as a past centre of the Belgian Grand Prix, hummed with the activity inseparable from the start of a big international event.

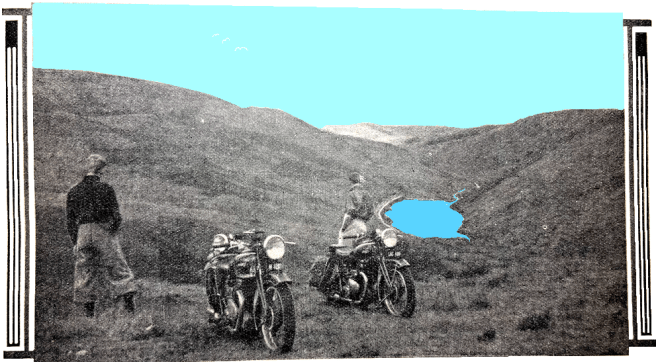

Everywhere could be heard the characteristic, hard bark of BMWs, and everywhere were Germans and German machines, much the same riders and machines—super-sports BMWs contrasting with 98cc two-strokes—as those which came to Wales last summer, accompanied by fleets of service lorries and sidecars, and swarms of managers and ‘headmen’. Probably their ultra smart military contingent, with blue-grey leathers and long coats, outnumbered the others, but one has now learnt to recognise their various units: the SS, on, it seems, somewhat older models; the NSKK [National Socialist Motor Corps], crack motorised brigade, in black leathers, with a sprinkling of works riders from the Triumph and NSU factories… In a teeming down-pour the weighing-in progressed in rather a scramble—a few marshals would have improved matters—and so to bed to be ready for the 6am start, rather anxious about the possible severity of the course, though, perhaps, much of the talk was ‘Scottish wind-up’…On Thursday morning it was still raining, cold and miserable, and within a mile of Spa, it became plain that this event was in a class quite different from what we understand for modern ‘Internationals’. A steep, greasy, stony hill, prefaced by a sharp hairpin, led through the woods, and here considerable excitement occurred, the failures being pounced upon by Belgian soldiers and pushed to the summit. Joe Heath made a really splendid climb on the 1,000cc Ariel add earned a loud cheer, and our solos were also very good. H’m, I thought, this is going to be pretty exciting. Too exciting, for almost immediately we were directed into

Denton Moor itself, or its exact replica. [Denton Moor was a feared section of the Scott Trial; word-search ‘Denton’ in 1929 for a detailed description and a heart-rending poem—Ed.] For what seemed miles we charged through horrible mud baths, occasionally sticking and having to heave the outfit along. Forgotten completely was the ‘International’ axiom of no outside assistance. Everyone helped everyone else, and spectators willingly lent a hand. Emerging at last, we at once entered an even longer and fiercer slough of despond. Although we gained a vicarious pleasure in becoming bogged just behind ‘Il Maestro’, Kraus, who had started 2min ahead of us, we were in bad trouble, for our chassis was far too low, and again and again we dug into a morass, or sank in enormous ruts. Heroically, Joe hauled and lifted and heaved again, virtually, I fear, unassisted by myself. Heavens knows I am no athlete, and very soon I was completely all in. Wolsey, who had taken a toss—how he longed for ‘comps’ back and front instead of ‘standards’!—and had had to change plugs, arrived at the check just within his allowance, approaching the village at a solid 85mph! Garty, an earlier number, less troubled by the general shambles, did very well indeed, but we—together with 75 others—were sadly late. Nor did matters greatly improve. There was one vile section, of only 11km, in which we again and again assumed curious angles in the pit-like ruts; frequently we had to hoist our heavy outfit back to a level keel, and the clutch was on the point of burning out. A chassis member was knocked into the wheel; the sidecar began lovingly to nestle against the Ariel. We were running later and later, and eventually were forced to retire, although no blame attaches to Joe, who motored an outfit which, fine for an ‘International’, was too near the floor for such Scott Trial stuff, marvellously well. Had he had a ‘one-day type combination—and a ‘real’ passenger: every German ballast appears an acrobat—no doubt he would have got through…Meanwhile the frightfulness proceeded. Just before lunch, at Beauraing, the Dutch Harley-Davidson, driven by the hefty Wuys, became so hopelessly bogged that a team of horses was necessary to extricate him; while when a rider like Fijma (Ariel) can retire through exhaustion, after a section which clogged front wheels with trials guards, it can be gathered that conditions were ‘formidable’ indeed, and several hills would have been regarded as finds by the Edinburgh club itself…Friday’s run was an anti-climax. The course went into Holland, but, alas, route marking almost entirely collapsed in the early stages—partly, it was said, because signs had been torn down for ‘political’ reasons—and everyone became hopelessly lost. Parties were arriving at the Valkenburg check from all sorts of directions, at all sorts of times, and everything was chaos. After considerable fireworks, the organisers did the only possible thing, ‘washed out’ all time before lunch, where an extra hour was allowed to sort things out. After, the run back to Spa was uneventful and, at last, the sun shone.

Another victim of the lack of marking was poor Garty. Riding in a block of direction-card-searching competitors, the man in front suddenly applied his brakes and Jack rammed him well and truly, pancaking the front wheel of his Ariel. So ended a very stout effort by a most competent performer, which left Gordon Wolsey, speaking most highly of his Triumph, the only British runner, albeit, a runner of the first order, for on all sides praise was heard of his fine riding. Saturday’s trip into Germany was expected to be severe, and severe it most certainly was. Practically the whole of the distance was over greasy lanes, fields and rough cart tracks, negotiating which, in torrents of rain, allowed even the best riders little or no margin at the checks. In contrast to yesterday, however, the organisation was superb. At Monschau, the frontier, a double rank of storm troopers cheered every rider as they passed the special Customs post established for the trial, and all along the way the marshals accorded the riders a Nazi welcome…After a really arduous morning, with never a moment’s relaxation, a morning of slipping off the step camber into ditches and off sliding off on greasy bends, a splendid lunch was ready at the famous Nurburg Ring, where the special attendant delegated to Wolsey looked after him splendidly, even drying his soaking clothes. After a circuit of the Ring, more he-man rough stuff had to be tackled. Mercifully, the, weather cleared, but it was a weary and bedraggled brigade which returned to Spa. To the delight of our party, Wolsey came through with flying colours—though in one check he had fallen five times. As his Triumph is cracking splendidly, there seems no reason why he should not successfully complete the final speed test to-morrow, Sunday morning. Poor Pé, the Belgian Gillett rider who had been doing so well, hit a lorry coming into Spa, and kaput went his clean sheet. Only 20 were still unpenalised and nearly 70 had retired, 19 of them to-day—figures which tell their own story! The BMW ‘Trophy’ team was placed in an unassailable position when Fruth, the driver of the sidecar in the other leading German team, pushed his outfit into the depot late. Next morning he did not appear at the speed test at Francorchamps—and that was that. The speeds required for this were quite easy for all classes, but the weather, especially during the second heat in which Wolsey ran, was vile, a cold, steady drizzle falling from a leaden sky. However, Gordon did his time satisfactorily and won his Gold with no marks lost. Far the fastest were Meier and Forstner on their BMWs. International Results. International Challenge: 1, Germany ‘B’, G Meier, J Forstner, P Struwe and L Kraus (sc) (all on BMWs). Coupes des Trois Federations: NSKK Sachsen, R Schertzer, W Fähler, R Dernelbaner (all on DKWs). Manufacturers’ Team Prize: NSU team, F Walter, H Dunz, P Ottinger). Gold medals were awarded to the best 20%; 24 went to Germans. None went to the Belgian or Dutch contingents but Gordon Wolsey brought one back to Blighty.

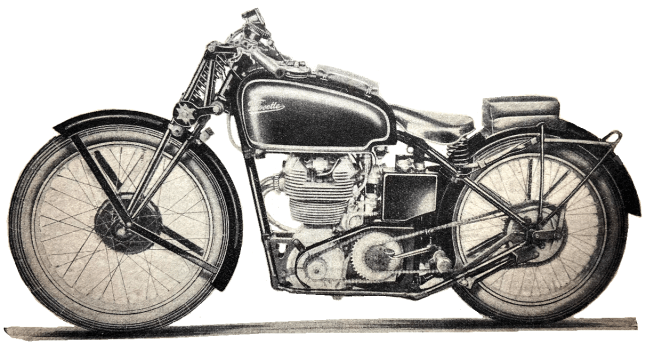

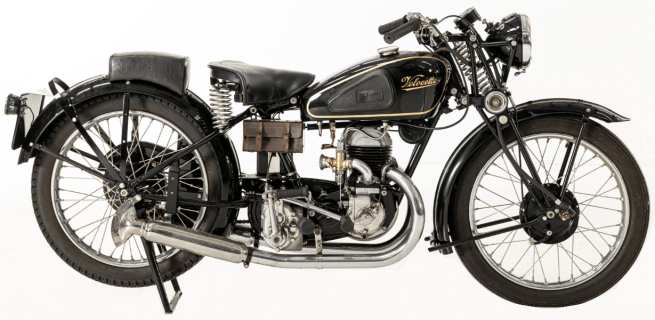

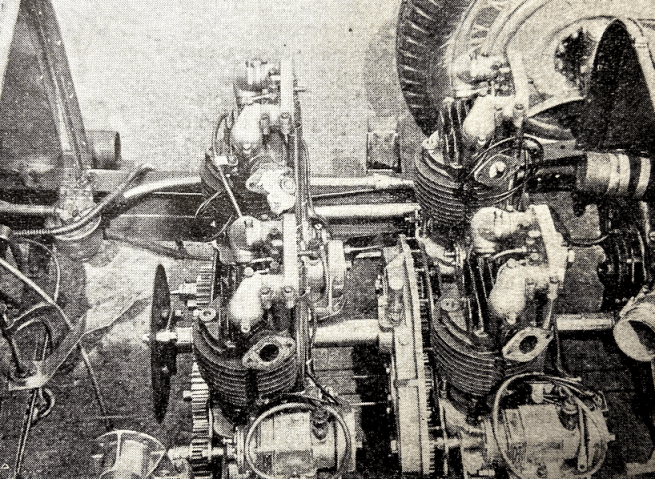

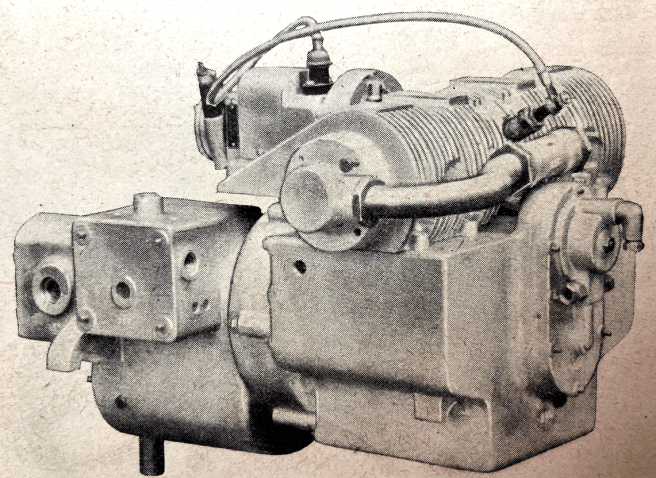

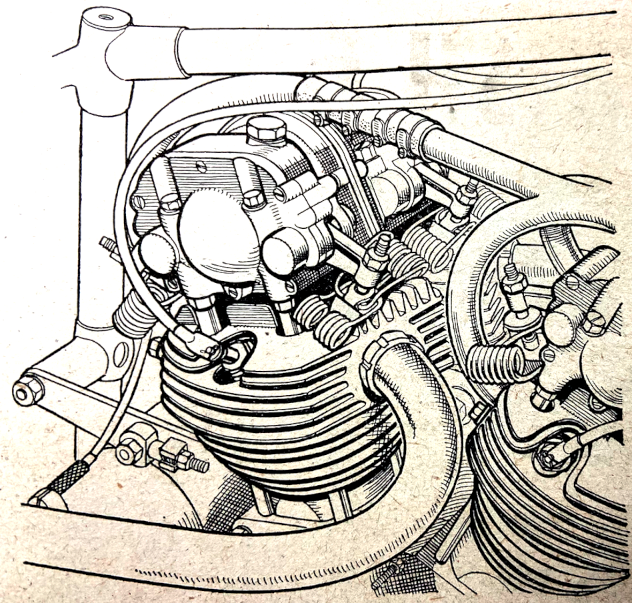

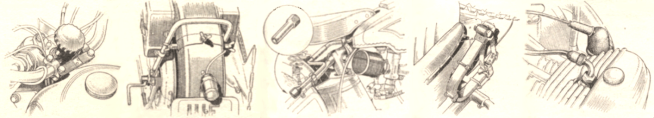

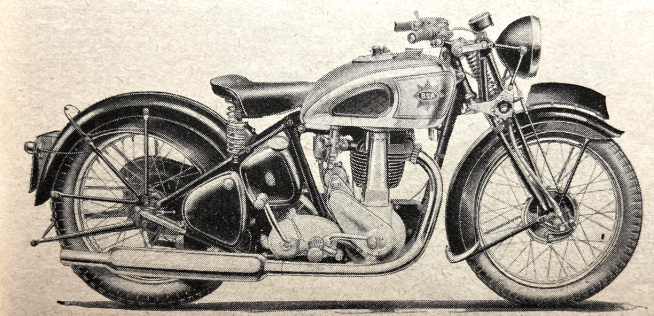

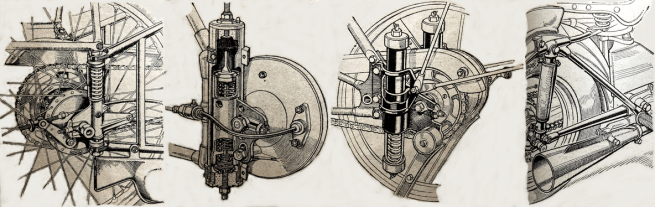

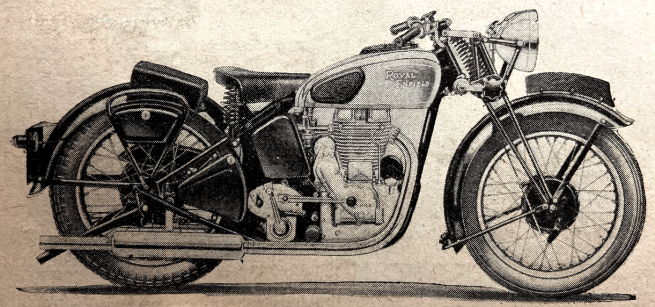

“THE NEWS THAT THE KTT Velocette is to be re-introduced will be welcomed by many motor cyclists, for this famous model was, in its old form, a favourite among racing and sporting riders alike. The new KTT is based on last year’s racing machines, and to all intents and purposes the engine and gear box are identical with those used in the machines which Stanley Woods and EA Mellors rode in the TT last year. The engine closely resembles the TT job, the only difference being that the cylinder head fins have rounded instead of square corners. The new engine is produced in the 348cc capacity only. It has a bore of 74mm. and a stroke of 81mm, and its compression ratio, for use with a 50/50 petrol-benzole mixture, is 8.75 to 1. An aluminium-alloy cylinder barrel with a special iron liner is employed, and the slipper-type piston has two compression rings and a slotted oil-control ring. The steel connecting rod, which is heavier than formerly, has the small-end bronze bushed. As in the TT engine, the cylinder head is of aluminium alloy with an integrally cast rocker box and inserted valve seats. The overhead camshaft is driven by bevel gears and a vertical shaft, and the entire valve mechanism, including the hairpin valve springs, is fully enclosed. Incidentally, the inlet valve is of larger diameter than the exhaust. Adjustment of the tappets is carried out by rotating the rocker spindles, which are eccentrically mounted. Oil is fed by a pump to a filter situated behind the magneto chain cover and thence via three jets to the main bearings, the upper camshaft bevels and the cams.”

“WE LIVE AND LEARN. I have a couple of tyres which have worn rather smooth, though still devoid of cuts and serious wounds. Realising that the long spring drought would certainly be followed by plenty of rain, and that these conditions create special risks of skidding, as the roads after a drought carry lots of rubber dust and oil, I decided to have these covers ‘sliced’, and to test for myself whether sliced treads grip a greasy surface as adhesively as their devotees claim. I am happy to report that the grip is Al. But to my perplexity and surprise the sliced treads in conjunction with certain types of wet road surface emit a curious whistling noise, quite unlike the sizzle of any standard tread.”—Ixion

“BEDFORDSHIRE POLICY ARE making increasing use of photographs as corroborative evidence in proving cases of dangerous driving and other traffic offences, but in some quarters it is being questioned whether, such photographs really do tell the truth. Half a dozen patrol cars in this county are fitted with cameras which enable photographs to be taken at speed.”.

“THE FOLLOWING RESOLUTION was adopted unanimously by the General Council of the RAC recently: “That this Council is of the opinion that in order to reduce the toll of road accidents it is desirable that positive obligations of a reasonable character should be imposed on all types of road users, including pedal-cyclists and pedestrians, and, in particular, that all pedal-cyclists should be registered and should carry rear lights and be subject to penalty for careless, riding, and that the movement of pedestrians across the roadway at controlled crossings should conform to traffic signals.”

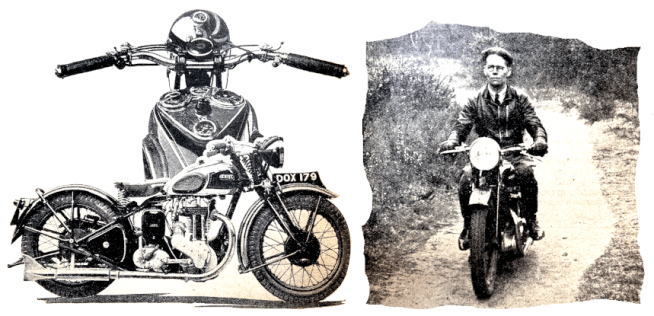

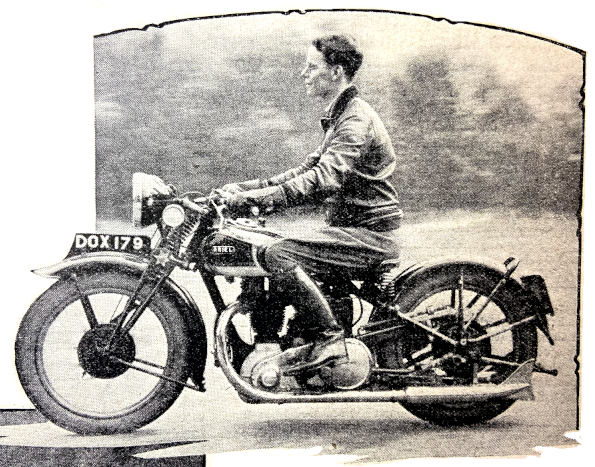

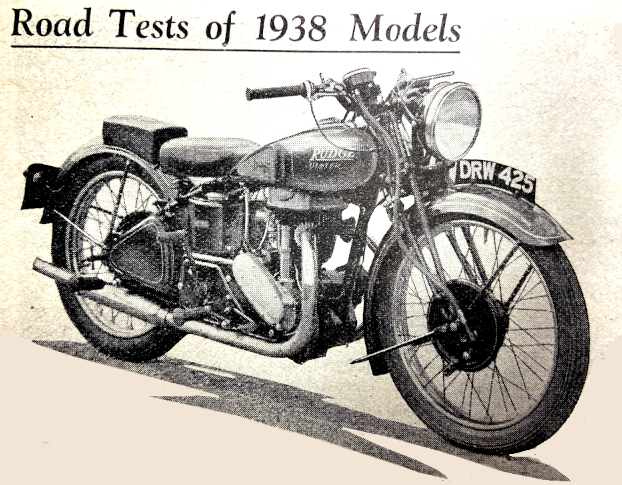

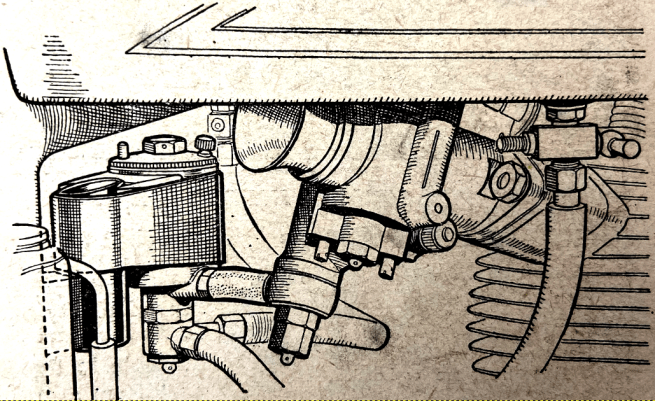

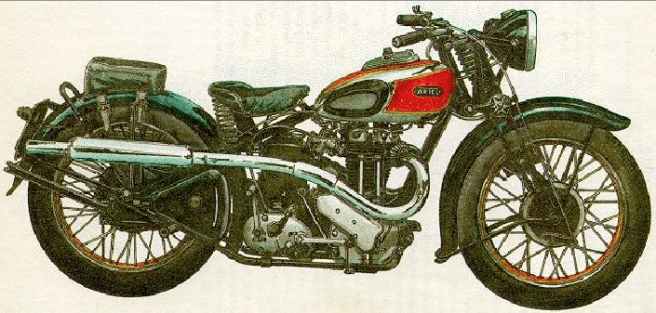

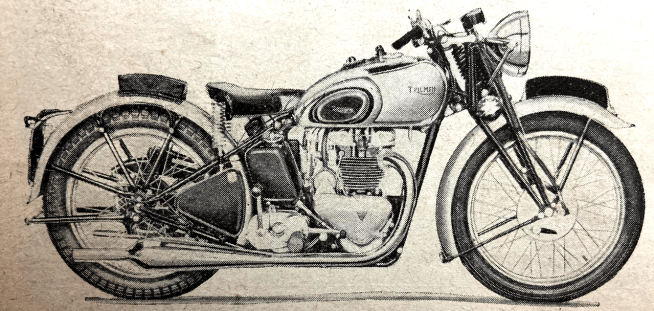

“IT IS HARDLY NECESSARY to make any introduction to the Ulster Rudge. Famous for years as one of the highest performance production machines, the 1938 edition still lives up to this enviable reputation and, in addition, has a number of refinements and modern improvements, which make it a most likeable mount to ride. Perhaps the most marked of these is the high degree of silence, both mechanical and exhaust, and the complete absence of any oil leaks after 350 miles. Coupled with this the Ulster produced a mean speed of 89mph and the speed for the standing quarter-mile of 51.72mph is the fastest yet obtained by Motor Cycling during the 1938 road tests on a 500cc machine. Seldom is such a combination of good qualities to be found in any one machine, and our tester reports that it is a difficult matter to offer any criticism. During the time the Ulster was in our hands it was used for fast main-road runs and a fair quantity of town work; two widely different duties which proved it to be a real dual-purpose model. Comfort was of a very high order, the controls, footrests and saddle position being adjustable to suit riders of all sizes. All the above-mentioned items were set correctly for the tester before leaving the Rudge factory, only one small modification being made subsequently to the foot change. This is mounted on splines and can be set to a very fine degree, which gives real nicety of control. The saddle was large and produced no feeling of fatigue even after a 200-mile spell. Handling under all conditions was superb; a really strong point in favour being the way in which it could be slung round corners of all types; fast, slow, rough or smooth, the Ulster always retained the ‘on rails’ feeling. Very little damping was necessary on the front forks, in fact, no damping at all produced about the best result under normal conditions. If the damper was ‘nipped’ up at all the tail end seemed inclined to bounce, and a certain amount of shock could be felt through the handlebars. Even when travelling flat out the steering damper was found to be unnecessary and accordingly remained right off the whole time. Mere mention of this machine brings the word ‘performance’ to any motorcyclist’s mind, so we will give some of the facts and figures which were obtained when a visit was paid to the measured ¼-mile. A maximum speed in top gear of 92mph, and a mean timed speed of over 89mph leave little to be desired. In the gears the results obtained were equally good. Third and second gears returned 84mph and 74mph respectively. At both these speeds the motor was turning over pretty quickly for a 500, but throughout the speed range no vibration could be detected.

We have made a brief mention of the acceleration, which was outstandingly good. At the bottom end of the scale, the motor, with the aid of the transmission, gave a really woolly feeling and in spite of the high gear ratios the minimum non-snatch speeds were uncommonly good, 18, 15 and 12mph being the figures in top, third and second respectively. When discussing the high maximum the touring point of view is apt to be forgotten. On a good main-road run the most comfortable cruising speed lay round about 65mph. This enabled some very high average speeds to be put up, for with a further twist on the throttle this rate of knots could be maintained up main-road hills. For normal fastish travel it was best to change up from second to third and third to top at 40 and 60mph respectively. Naturally, when indulging in ordinary slow-speed touring these speeds were considerably lower, but the engine was so smooth and flexible at all times that the cruising speed could only be determined by the rider’s frame of mind, the scenery, or the general road conditions. Riding as stated above the fuel consumption remained very consistent at about 70mpg. Separate and accurate tests were made in town and country conditions which showed 66mpg and 74mpg; all of these figures are markably good for a really high-performance 500. The oil used was negligible, the level dropping only about ¼in. after 3OO miles; further-more, any oil which was used was certainly not due to any external leaks. The whole engine and gearbox were spotlessly clean, the only leak at all being from the oil tank filler cap due to the level being too high; when this had been reduced to about an inch below the neck, all the leakage stopped. From the quietness point of view the Ulster deserves full marks. Mechanically, it was one of the quietest engines we have had on test, and the exhaust silencing has been dealt with in such a manner that it is really quiet except when the ‘urge’ is turned full on; even then there is no bark attached to the noise, and it is doubtful whether anybody could possibly take umbrage. The gearbox was silent on all the ratios in addition to being very pleasant to use. When first taken over the change down was a shade uncertain, but after some real usage this appeared to wear off and then worked well. The change up was always beyond criticism. Starting was very easy both hot and cold. In either case the ignition had to be set at about half retard, and when cold the carburetter gave the best results after being flooded. When hot this was unnecessary, and one good hearty kick produced the

desired result after easing the compression with the valve-lifter. First thing in the morning using the decompressor enabled the valve-lifter to be left alone. The well-known Rudge coupled brakes were delight-fully smooth in operation and very powerful. On the actual brake test it was found possible to stop from 30mph in a matter of 32ft. The additional front-brake lever was used to obtain the above figure. Ease of maintenance is obviously a matter which has received the close attention of the manufacturers. The valve clearances are set through the inspection cap in the off side of the valve enclosing cover. The adjusters themselves are placed at the push-rod end of the rockers. Easy, adjustment is provided for the primary chain by moving the gearbox with a cam; this principle is also employed to tension the rear chain, both operations taking a very short time. Another feature is the quickly detachable rear wheel which can be removed while the chain and brake drum remain undisturbed. Easy access is provided to this with a detachable rear mudguard. The hand-operated central stand was delightfully easy to operate and at the same time gave a really firm support even when the model was propped up on rough ground. The sensible dimensions of both the oil and fuel tank filler caps made the easiest possible job of replenishing: also the extended gearbox filler was very conveniently situated. With the days as long as they are very little night riding was indulged in, but one short journey was sufficient to show that the head lamp possessed a powerful beam. also that the dipper switch was well placed and positive in action. There was no cause to use the tool kit during the test, but it it was examined and sundry spanners applied to some of the most commonly used nuts. They appeared to be amply strong for their job. Talking of equipment, it would be as well to remind our readers that the Rudge is a fully equipped machine with no extras. Standard specification includes an illuminated 120mph Smith’s chronometric speedo-meter, lights, licence holder, horn and rear mudguard pad. At the conclusion of the test we can say without fear of contradiction that the Ulster is one of the best machines it has been our good fortune to have on test. Such a combination of good handling, performance, and complete equipment is seldom to be found grouped together in one model. The price is £82.”

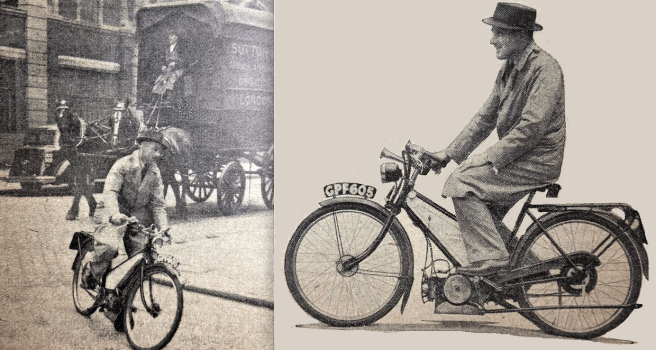

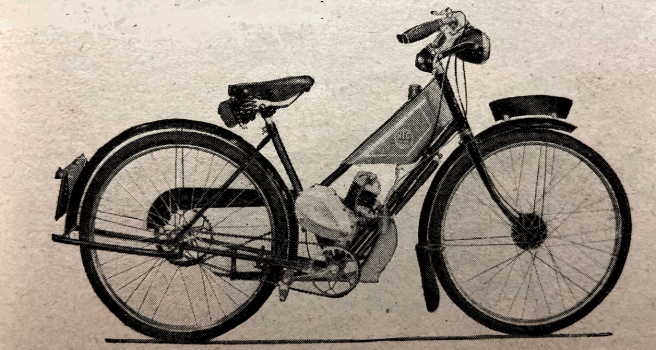

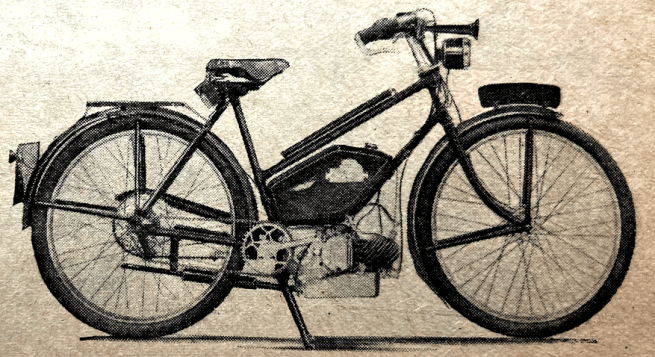

“THERE ARE NOW SEVERAL different types of motorised bicycle on the market, most of which it has been my good fortune to ride. During the last few weeks I have had in my stable a 98cc Villiers-engined Raynal—and a very interesting little job it is. It has several unusual features, chief of which is a sprung front fork. There are also a clutch, normal pedalling gear and a back-pedalling brake which is designed to avoid accidental application when the engine is in use. On machines of this type a spring fork is generally considered a luxury, but at the speed of which the Raynal is capable, it is very nearly a necessity. A short, laminated spring is employed, which allows a fore-and-aft movement of the fork blades. This movement can, to a certain extent, be adjusted by tightening or slackening the shock absorbers. A back-pedalling brake is an advantage on a motorised bicycle because it reduces the number of handlebar controls. However, this type of brake normally has the disadvantage that the slightest backward movement of the pedals applies the brake. On the Raynal, a hub-type brake is fitted, and this is operated by lever and rod from the pedals. The lever, which works on the ratchet principle, engages with the pedals only when the offside pedal is just past the horizontal position behind its crank. With this arrangement it is possible to ride many miles and shift the position of the feet without fear of the brake being accidentally applied over bumpy surfaces. Another feature of the Raynal is its open-type frame—an obvious advantage for riders of the fair sex. The handlebar controls consist of a clutch lever, with a trigger lever to keep the clutch out when required, a decompressor for starting and stopping the engine, a throttle lever and a front-brake lever. Attached to the fuel tank is a small knob, which operates a simple form of carburettor choke to facilitate starting from cold. There are two ways of starting the Raynal. One can either pedal off and, after gaining sufficient speed, let in the clutch, or one can paddle off—both ways are equally simple. When starting from cold it is both necessary to flood the carburettor and to use the choke; after 100 yards or so the choke can be taken out. The 98cc Villiers engine pulls away from walking pace to its maximum without a trace of snatch, and the drive is taken up so gently that the veriest novice need have no fear of the machine running away with him. Such flexibility, coupled with extremely smooth running, inspires confidence at the outset. And, above all, the little engine is exceptionally quiet. The drive from the engine is taken through a counter-shaft and clutch to the rear wheel by a chain on the near side of the machine. On the off side is the normal pedalling gear. The two methods of transmission are quite independent. In many respects the Raynal handles in exactly the same way as a cycle. With the drive disengaged by leaving the clutch withdrawn, the machine can be ridden as a cycle. The pedalling gear is not unduly low—in cycle terms the gearing is 60, or in other words one revolution of the crank turns the rear wheel through two complete revolutions. Because it resembles a cycle in many ways, the Raynal is extremely manoeuvrable in traffic, either with the engine or without. When traffic or other conditions demand, the engine can be throttled down to walking pace; if a slower speed is desired the clutch may be slipped slightly while the pedals are used. Even from a standing start the Raynal will accelerate without the rider

pedalling. On steep hills it is sometimes necessary to assist the engine with a little light pedalling, but for the most part the pedals can be forgotten. The maximum speed of the Raynal is between 28 and 30mph and it can be ridden on full throttle for mile after mile without the engine showing any signs of tiring. I have ridden the Raynal on several occasions be-tween my home in North Surrey and the office, through some of London’s densest traffic. By train this journey takes me 45 minutes from door to door. By road, a distance of 13 miles, it usually takes me 35 minutes on a fast solo. On the Raynal it takes only five minutes longer. On these journeys I was able to appreciate the advantages of the sprung front forks. But I should have welcomed a larger and more comfortable saddle. Another small criticism that can be made against the Raynal is the absence of a chain guard on the off side. A guard is fitted over the transmission chain, but when the machine is being pedalled the off-side chain is apt to trap the rider’s trouser leg. From an economical viewpoint the Raynal is an exceptional little machine. It covered just over 105 miles on one gallon of petrol mixed with half a pint of oil. This fuel consumption was measured on the runs to and from the office, ie, under traffic conditions. Throughout the time the machine was in my possession the engine remained clean except for a slight film of oil in the vicinity of the carburettor; this was probably due to blow-back, which was noticeable when accelerating from a slow speed. The Raynal is just as happy on full throttle on the open road as it is pottering round town streets. At all speeds the engine is remarkably free from vibration. Restarting with a dead engine on a steep bill calls for a certain degree of skill, but on account of its exceptional manoeuvrability (the machine can be turned in its own length) it is far simpler to start the engine down hill and then turn the machine round, pedalling when and as required. The brakes are in keeping with the excellent standard of the rest of the machine. They are both light in application and efficient in use. The rear brake in particular is surprisingly powerful; it is applied with the right foot through the medium of the pedals. Incidentally, a feature of the Raynal is that the chains can be adjusted independently. The equipment includes Villiers flywheel-dynamo lighting, 26xl¾in Dunlop tyres, ‘Shockstop’ handlebar grips and a fuel tank with a capacity of 1⅛ gallons. Yet the price of this efficient and economical little machine is only £18 18s.”

“JAPAN NOW HAS approximately 57.000 motor cycles in use.”

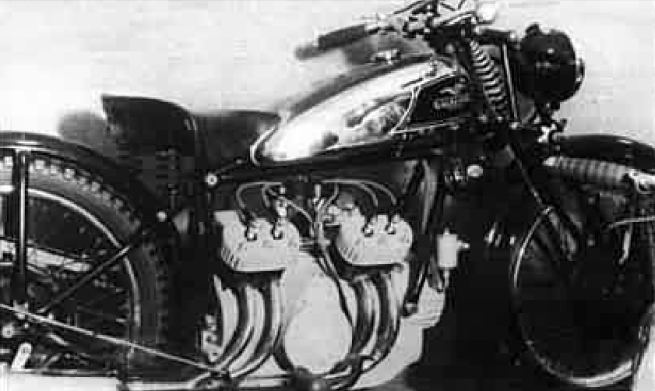

“A MANUFACTURER OF a famous multi-cylinder machine reports that sales of the model are 61% higher this year than last.”

” A CAR CLUB RECENTLY held its annual ‘criminal hunt’, in which competitors sought for clues putting them on the trail of a gang of American desperadoes.”

“MOTOR CYCLES WERE involved in only 14% of the road accidents in the Isle of Man last year, the lowest percentage for 12 years.”

“IT IS REPORTED that riders buying new machines in Germany are now asked to sign an undertaking that they will surrender the machines at military depots in the event of mobilisation.”

“THE ARIEL COMPANY ships its machines to no fewer than 68 different nations. This means that catalogues have to be printed in many different languages, ranging from Lithuanian to Siamese.”

“Five-hundred AA patrol men have joined a Supplementary Reserve of the Corps of Military Police.”

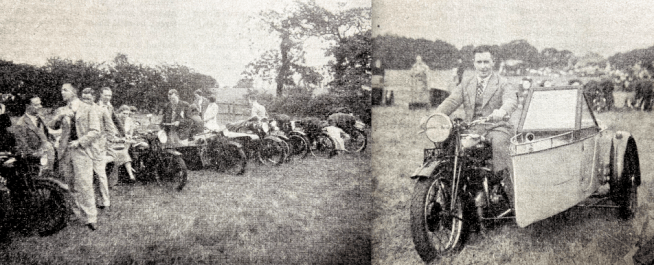

“NO MORE GLORIOUS day could be imagined than last Sunday, when the Scott Rally was held, and members of the London, Manchester and Sheffield Scott Clubs converged on Donington Hall. There was a representative gathering, and nearly every type of Scott motor cycle was to be seen by the time the assembly was complete. Old Scotts, young Scotts, little Scotts and lordly Scotts were there. Some were resplendent in modern chromium and coloured enamels, and others were—and the owners will forgive the description—a rather dingy black, tinged with the stains of thousands of miles of travel. But all were the pride of their riders. and the older the machine the greater seemed the pride. The prize for the oldest machine in its most original form went to Mr Reed, of York, with a 1919 two-speeder; the only change from the original equipment was to be found in the front wheel, which now boasts an expanding brake. As an instance of the enthusiasm possessed by all motor cyclists (and Scott owners, perhaps, in particular), the prize for the rider travelling the farthest distance to the rally went to Mr Short, who had come all the way from Eire. His total mileage was 323. For ingenuity in devising and including gadgets in the equipment of a motor cycle the palm went to Mr Jones, of Liverpool. His extra fittings included the spring frame, the rear mudguard valance and stop light, tiny parking lights front and rear with an independent switch, wire stone guards on his head lamp, a fog lamp, bumper bars, a fire extinguisher and a radiator thermometer. During the afternoon a gymkhana was held. All the events were hotly contested. Frank Varey was there, and he put in some good work. He thrilled the crowd with an unusually hectic and rapid demonstration run. After tea the prizes were distributed at the Hall.”

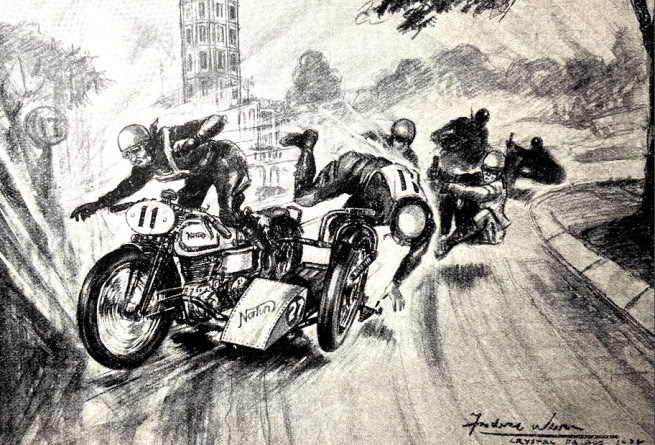

“I AM WRITING to correct a wrong impression that has been created by the newspapers re my crash at the recent Crystal Palace meeting. The cause of the trouble was another competitor who ran into my passenger on the Link Bend, when the latter was hanging out over the sidecar, nearly knocking him off. The front wheel of this machine then hit my sidecar wheel, causing me to get out of control and I hit the wall surrounding the pond. The rider of the machine in question approached me in the Paddock after the race and told me that he had been unable to stop and could not help hitting me. The machine is badly folded up but fortunately my passenger and myself are not seriously hurt.

AH Horton.“

“DO MEMBERS OF THE Government motor at week-ends? We cannot believe they do—at all events not on fine Sundays in the summer. How otherwise can be explained the present road policy? The Ministry of Transport took over the trunk roads in April of last year, yet what has been done? The answer from the car owner’s and motor cyclist’s point of view is, ‘Little or nothing!’ Progress is painfully slow. It the reason is that all available money is required for re-armament, the Government should say so and the motoring world would endeavour to be patient until such time as there is the money. On the other hand the Minister of Transport himself has said that there is no question of lack of money. Then why is there the delay? Parliament has risen; can we hope that members will make a point of motoring at week-ends—of learning at first hand the congestion their constituents suffer?”

“THE 250cc brigade should read, mark, learn and inwardly digest our recent leaderette based on the Bentley engineers’ maxim that 75-80mph is the highest safe continuous speed of a car which can touch 100mph. No commercial engine is built to run continuously at or near its maximum revs. This moral was hammered home in Italy when the first autostrada was opened. Bright lads went on to it, hooted with glee, put their foot right down and kept it there; and the towing gangs were requisitioned daily to haul dead cars off the concrete. I don’t know if the wee 98cc brigade have learnt this lesson yet, but I have often noticed that when a novice gets the real hang of his first 250 and starts scrapping hard on it something snaps.”

“YOU KNOW, OF COURSE, of the present search for crude oil in the British Isles. After Anglo had made their first boring in Sussex and been rewarded merely by a deep, dry hole, the machinery was moved to Scotland. Traces of oil and gas were found at various depths, and drilling continued to 3,857ft in the hope of finding something better. Oil was found a 1,733 to 1,760ft and the well is found capable of producing 8 to 10 barrels of crude oil a day—oil that contains some 12% petrol and 12% kerosene.”

“AT MANCHESTER ASSIZES, damages amounting to £5,500 were recently awarded the pillion passenger of a motor cycle against a car driver, sequel to an accident.”

“RUSSIA PURCHASED British motor cycles over £1,050 last year.” But some were home-brewed…

“A PROPOSED round-the-world tour for car drivers has been abandoned owing to lack of entries.”

“THE AUSTIN SEVEN racing engine can attain a speed of 10,000rpm on the track, and it has been bench-tested up to 14.000rpm.”

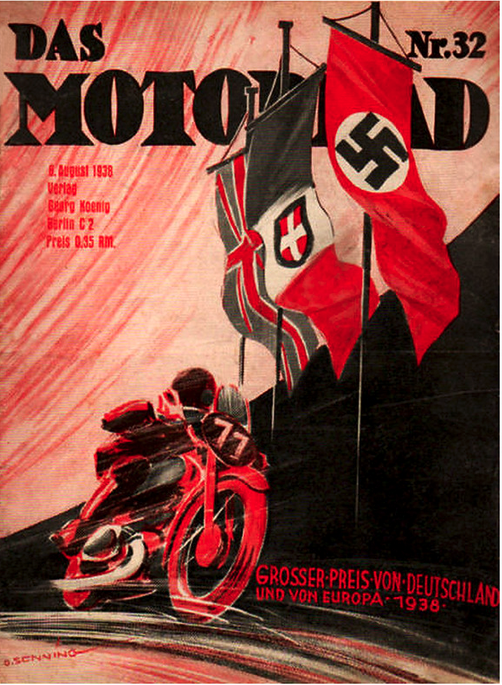

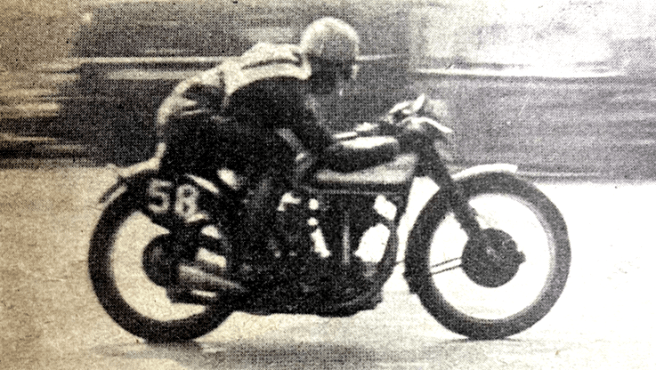

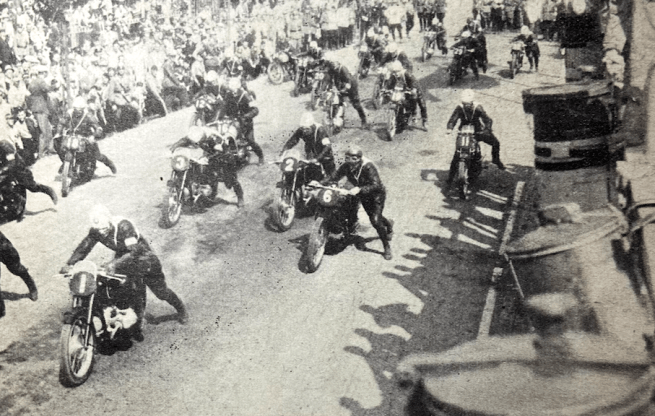

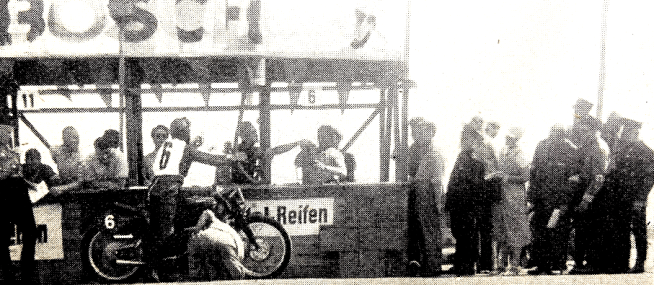

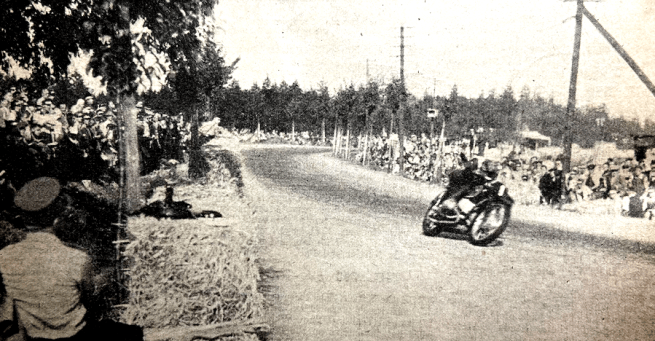

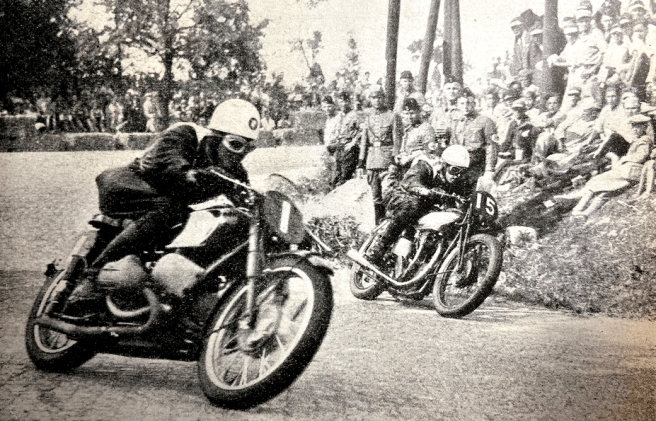

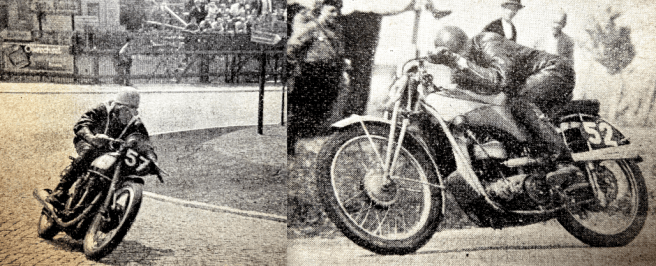

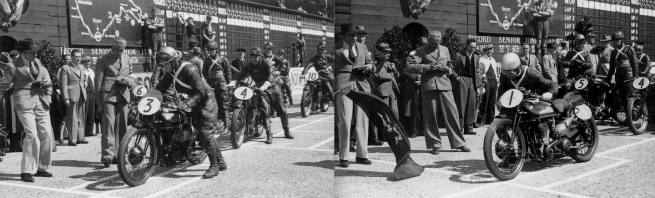

“GREAT BRITAIN AND GERMANY shared the victories in the Grand Prix of Europe, held at Hohenstein-Ernstthal, in South-eastern Germany. The racing was inclined to be dull, for the winners of each class established themselves from the first lap in all three races and were never seriously challenged. Nevertheless, the vast crowds of Germans (some 300,000) who thronged the sides of the road remained enthusiastic throughout a long day in broiling sunshine. They had come to the course from all parts of Germany, and in the temporary vehicle parks on the autobahn skirting the circuit there were thousands of motor cycles. The course has been slightly altered from previous years. The start-and-finish is on the straight which runs alongside the autobahn, and the acute hairpin bend by the old start has been replaced by an easier, banked turn. This course in Saxony is a very sporting one, for it contains many tricky and twisty sections, and is far from flat. In view of their recent successes, it was not surprising that the DKW 250s were present in force on their home ground. But it was disappointing that only two other machines of different make came to the starting line. At the last moment the Italian Benellis had

scratched, leaving only the DKWs and two private entrants. The race was almost a foregone conclusion, and when Kluge (DKW) came round at the head of the pack of DKWs everyone nodded their heads, After seven laps the order was Kluge, Petruschke, H Drews, and E Thomas, all on DKWs. When Thomas passed through the start he was heartily cheered, for the crowd were quick to appreciate foreign skill. But on the next lap he retired with clutch trouble. After Thomas’s retirement Kluge and Petruschke drew ahead of the rest of the field, and Petruschke, by magnificent riding, gradually overhauled Kluge. On his 12th circuit he broke the lap record, and soon overtook Kluge to take the lead. On the pit stop, however, he lost it again, for Kluge was slicker by several seconds, and from then on Kluge, now with the European Championship well in his pocket, was never troubled. When the field had been flagged in, the winner and the first private owner to finish were driven round the course in the new German ‘Volkswagen’ cars, together with Herr Hühnlein and FICM stewards Nortier and Ball. For the 350cc race there a larger and much more varied field. JH White and Walter ‘Snow White’ Rusk were hot favourites on the Nortons, but Winkler and Wünsche, with their DKWs, also had their supporters. Other stars competing includes Mellors (Velocette), Fleischmann (NSU) and Grizzle (Sarolea). They were lined up on the road in nine rows of four, with the DKWs and Nortons in front. Red, amber and green lights and a maroon were used for starting, and as the lights changed there was a terrific struggle for leadership among the huge field.