“THERE IS ONE NEW YEAR’S resolution at least that will be welcomed by London motorists. We refer to the instructions issued by the Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis to police officers to caution persons who behave carelessly or without regard to their own and other people’s safety. The edict applies to all road users, whether motorists, cyclists or pedestrians. Why will the new campaign specially benefit motorists? Because, we suggest, it marks the beginning of the end of that system of petty persecution that has threatened to estrange motorists and those who should be their friends—the police.”

“MY CHRISTMAS-JANUARY 1st mail always packs a thrill, because it is sure to contain warm-hearted letters from exiles of whom I have never previously heard. The 1936-7 change over was no exception. For instance, two pals in Western Australia; one has just got married, and the other elects to stay single. The married one can only run to a 1925 350cc side-valve Douglas, which cost him one pound. The bachelor pal has a 1929, 680cc Brough, which cost him £65. (Woman, what sacrifices are not borne for love of thee!) Then another from Sask, which I assume to be short for Saskatchewan. This letter might be summed up as ‘100° to 40°’, which is not a bookmaker’s odds, but the range of temperature in the writer’s year, varying from 100° in the shade at mid-summer to 40° below zero in midwinter. Add to these extremities of heat and cold ‘dirt’ roads, gravel tracks, deep sand, ice snow and floods, and you can easily see that only a he-man will invest in a form of transport which resembles a cowboy rodeo in the summer and threatens you with frost-bite all the rest of the year. Yet there are many out there who are passionate students of The Motor Cycle, are as well versed as our staff in the sporting history of the motor cycle and the merits and demerits of this machine and that; and almost without exception they yearn to return to he old country and to watch a TT!”—Ixion

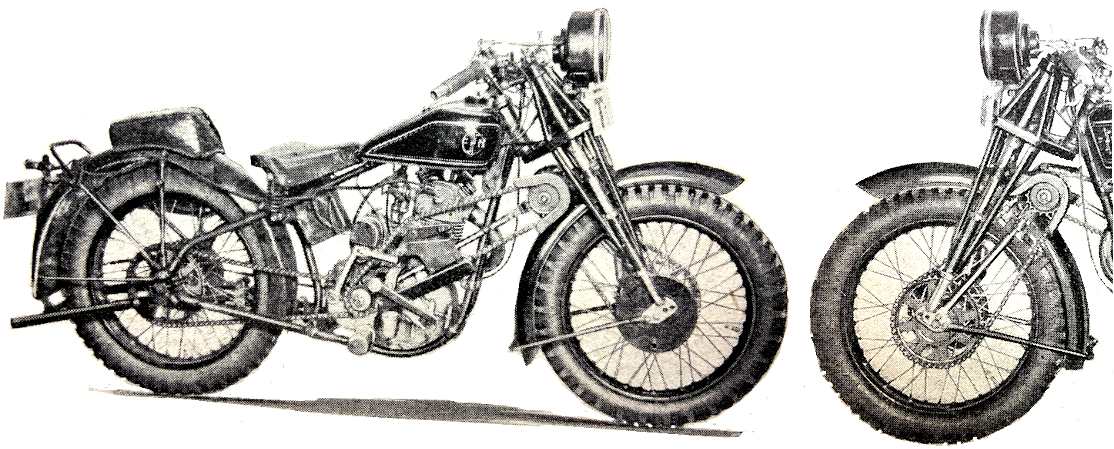

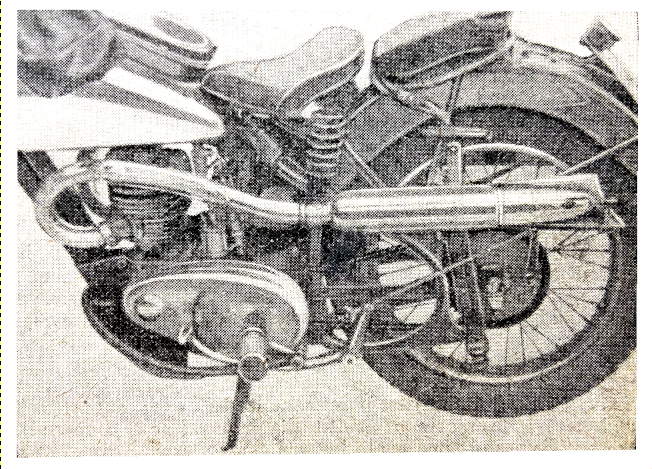

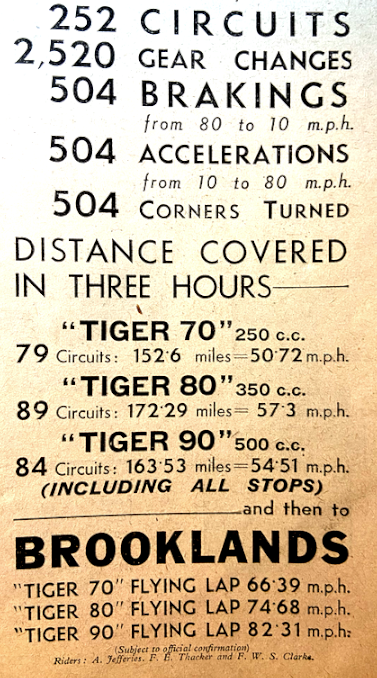

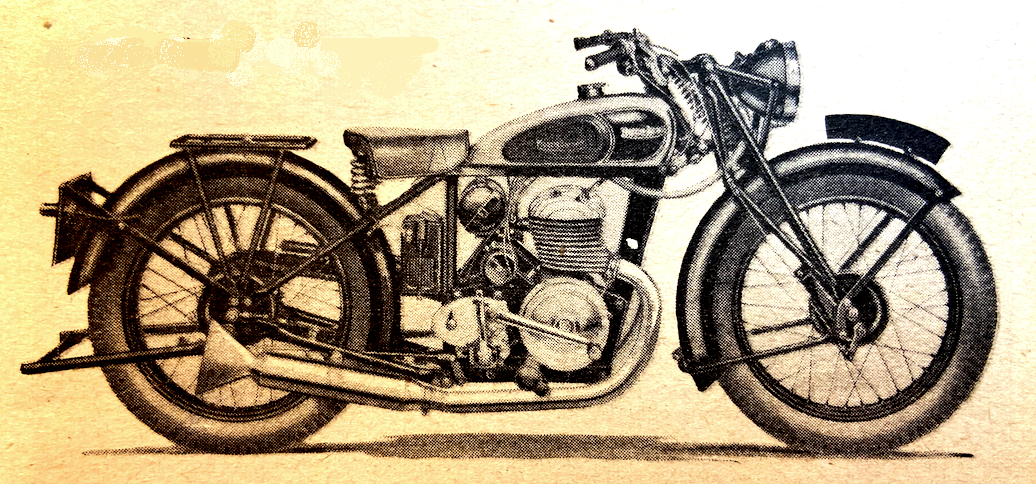

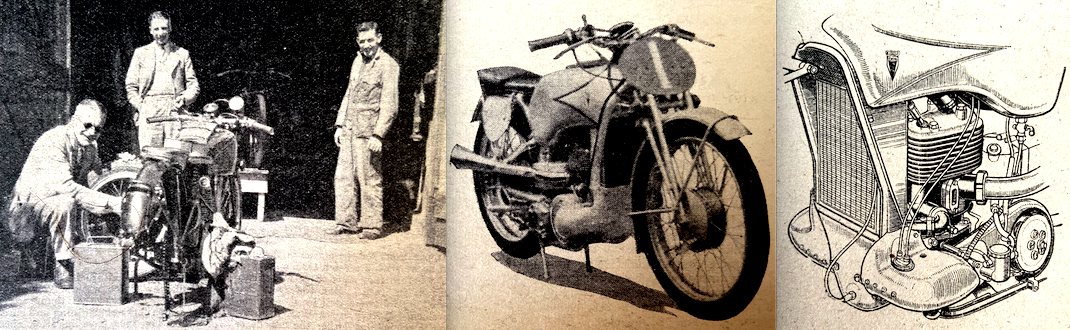

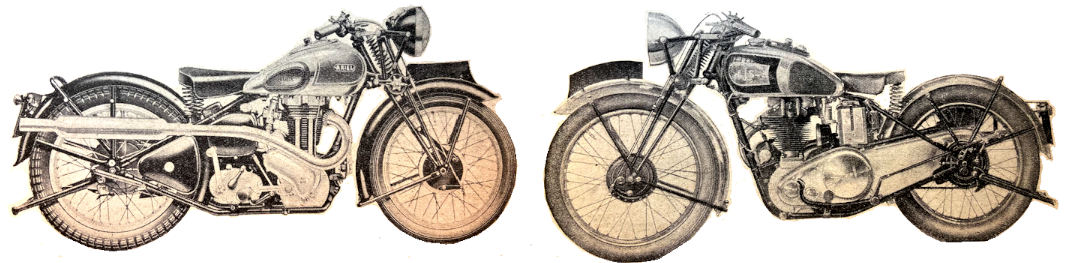

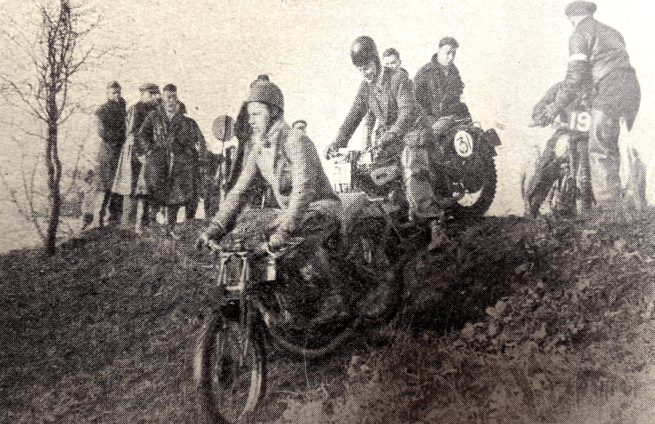

“TRIALS ENTHUSIASTS WILL BE interested in the range of Triumph Tigers in competition form which have just been introduced. The new models are based on the existing Tiger range, and are obtainable with 249cc, 349cc and 497cc ohv engines. Special wide-ratio four-speed gear boxes are fitted, and a variety of ratios is available. With a 17-tooth engine sprocket, ratios of 6.46, 9.36, 14.83, and 19.82 to 1 are obtainable. At the other end of the scale, ratios of 4.78, 6.93, 11.00 and 14.7 to 1 are obtainable with a 23-tooth engine sprocket. Other interesting features of the new competition Tigers include increased mudguard clearance, a sturdy crank case, undershield, and a special front fork spring. The engines are specially tuned, and designed to develop plenty of power at small throttle openings. In this connection particular care has been taken in tuning the carburetter. Either high- or low-compression pistons are available.”

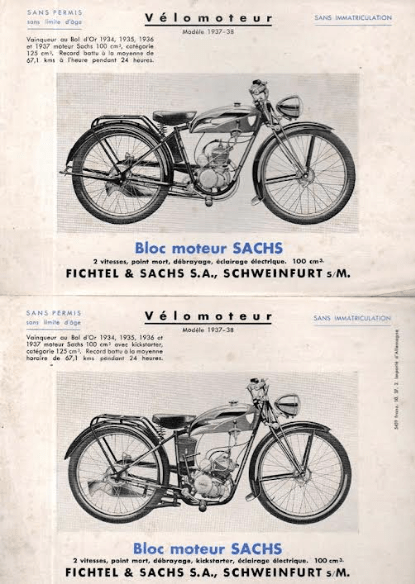

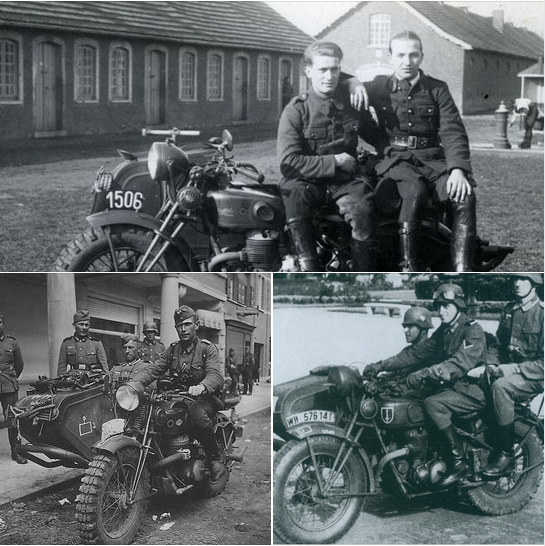

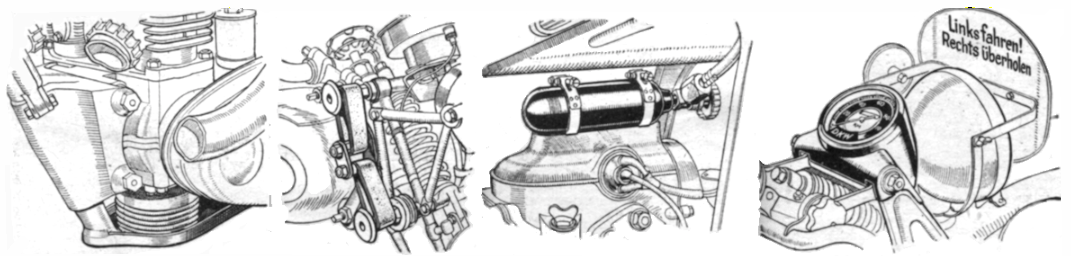

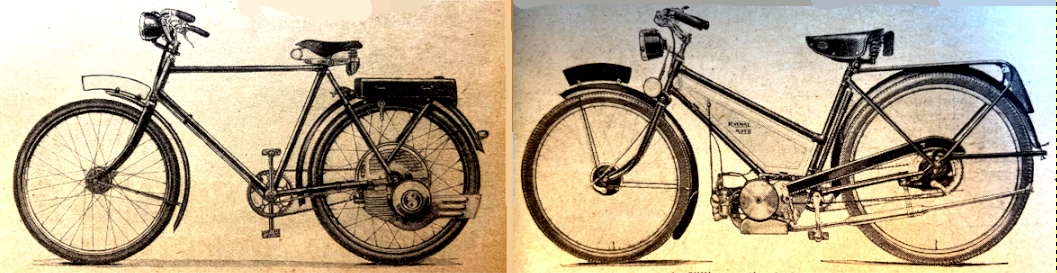

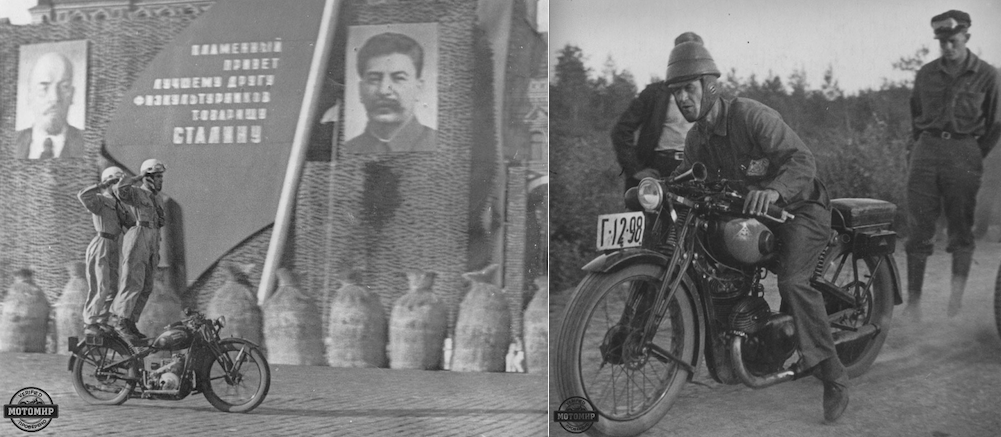

“THE INFORMATION PRINTED in this brochure anent motor cycling is tantalisingly sparse, but it is sufficient to indicate how the Government policy in Germany surpasses that adopted in Britain. For example, number, of motor cycles in use: Germany, 1929, 610,000; 1934, 936,000=plus 53.4%; United Kingdom, 1929, 732,000; 1934, 548,000=minus 25.1%. Germany registered an increase of over 50% in these five years in spite of her general economic condition being so bad that she is still short of certain vital foodstuffs. She accomplished this feat by eliminating vexatious governmental interferences, such as imposing heavy tax and insurance charges on lightweight machines in the British manner. This courageous policy has produced the following results, which can only be regarded as extremely beneficial from a purely nationalist standpoint: (a) It has increased employment by selling 25,000 additional machines in each of the five years. (b) It has enriched Germany by a large number of skilled mechanics. (c) It has rendered German labour much more mobile. (d) It has improved the physical standards of a substantial section of the youthful male population. We might have enjoyed similar benefits had we been blessed with more intelligent and far-sighted rulers. Germany is now easily the largest user of motor cycles in the world, although we still retain 60% of the world’s export sales.”—Ixion.

PS IXION REVEALED that he had picked up his first speeding ticket after 40 years and 750,000 miles.

“THE steady increase in the value of British motor cycle exports that was a feature of the first 10 months of 1936 was maintained in November, the figures for which month have just been issued. Machines to the total value of £64,869 were exported, of which £32,173 was spent by Australia. The total value of machines and parts exported during the 11 months of 1936 amounted to £1,004,135. Once again Australia heads the list as Britain’s best buyer, with a total of £240,346. Of the foreign countries, Holland purchased motor cycles to the value of £47,503 during the 11 months.”

EIGHT BELGIAN MARQUES were producing about 35,000 motor cycles a year.

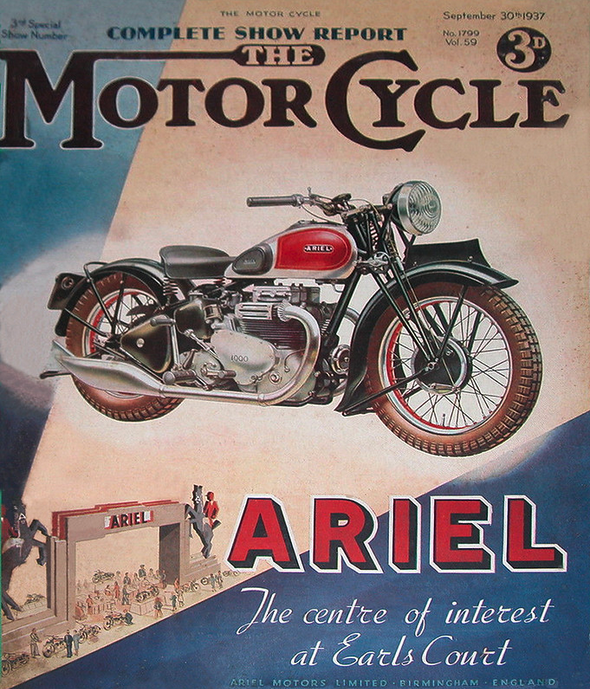

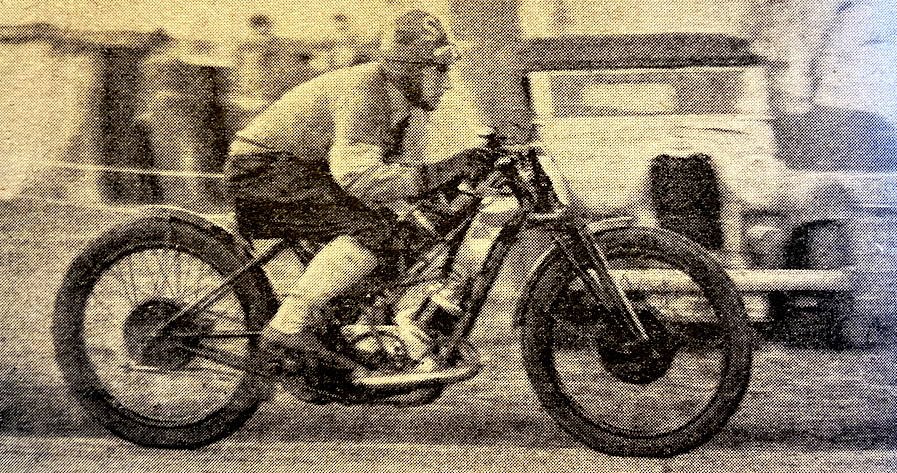

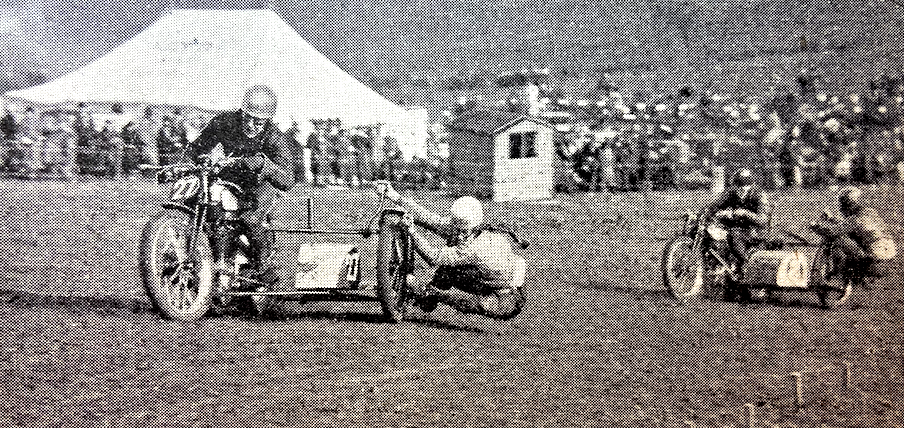

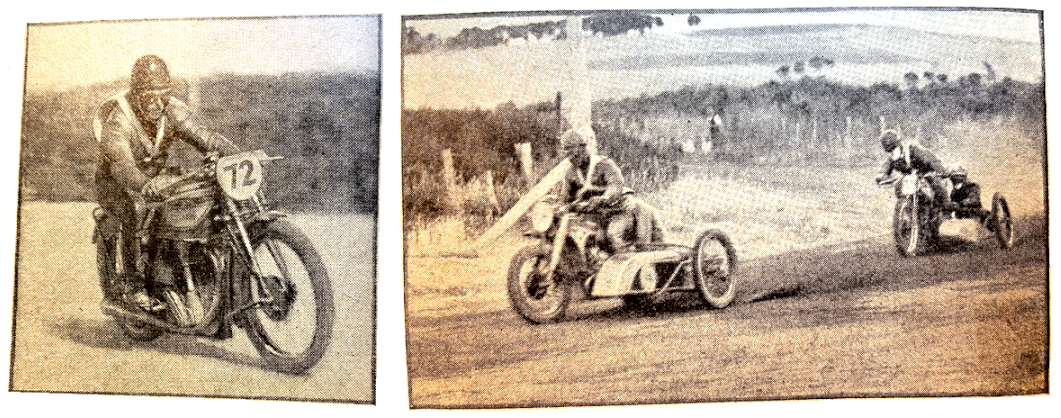

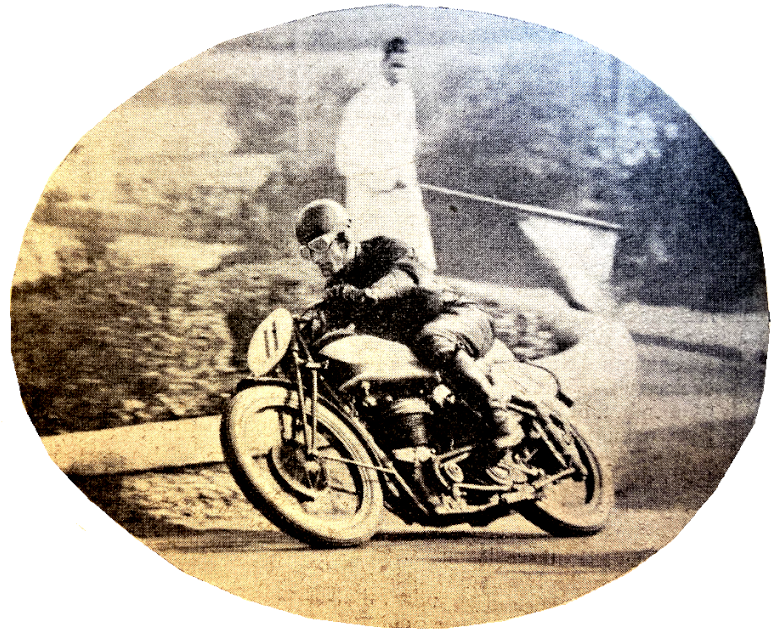

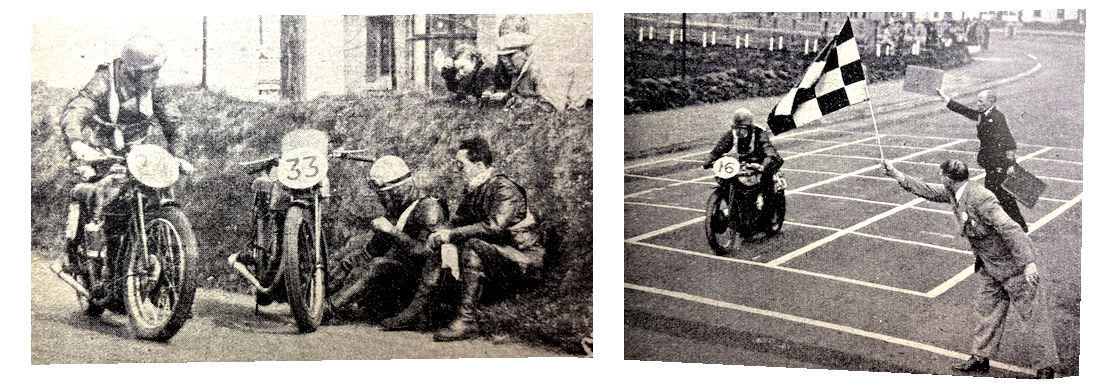

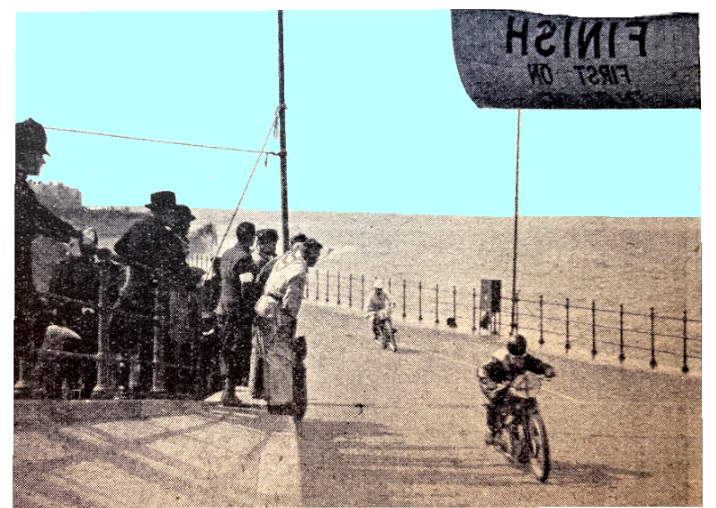

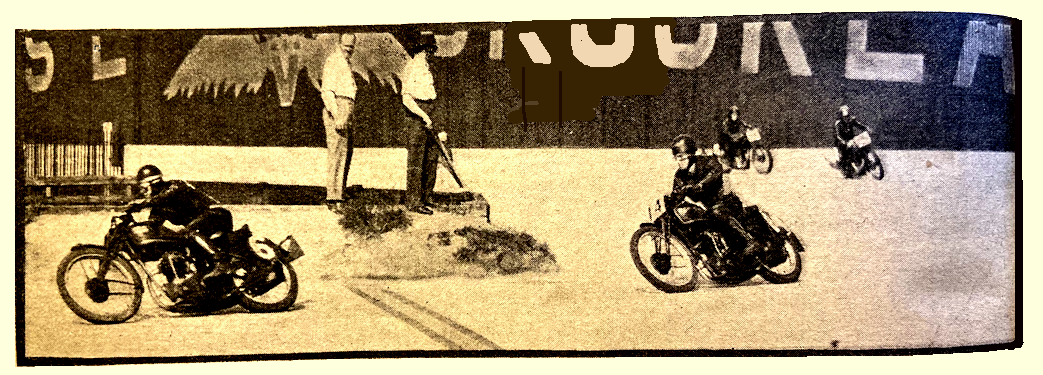

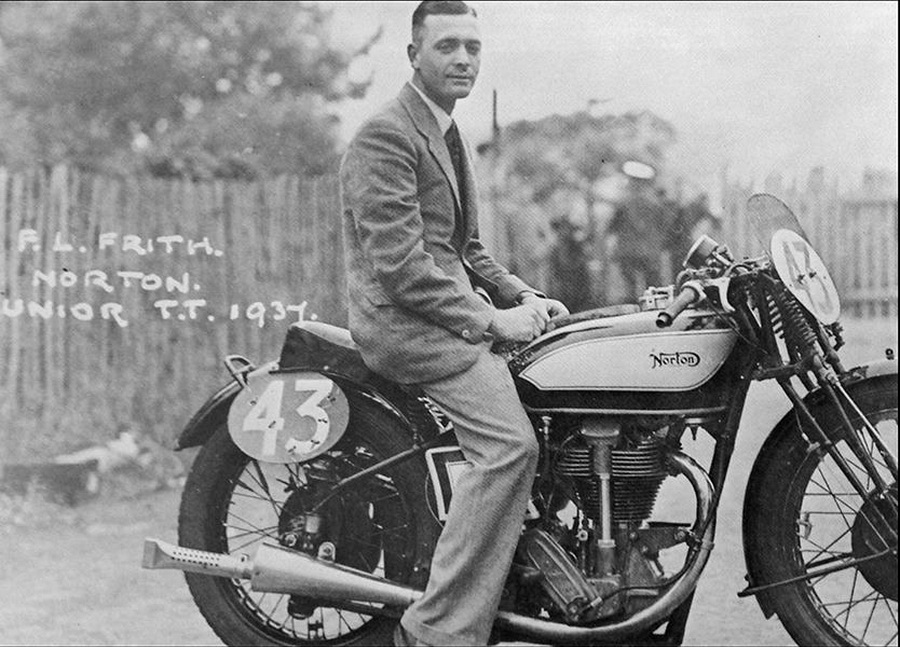

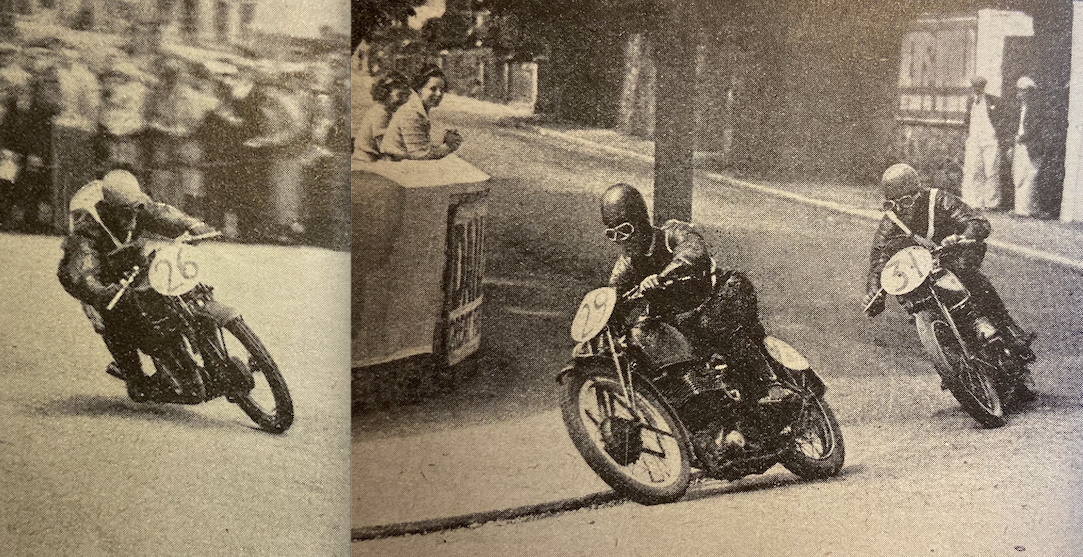

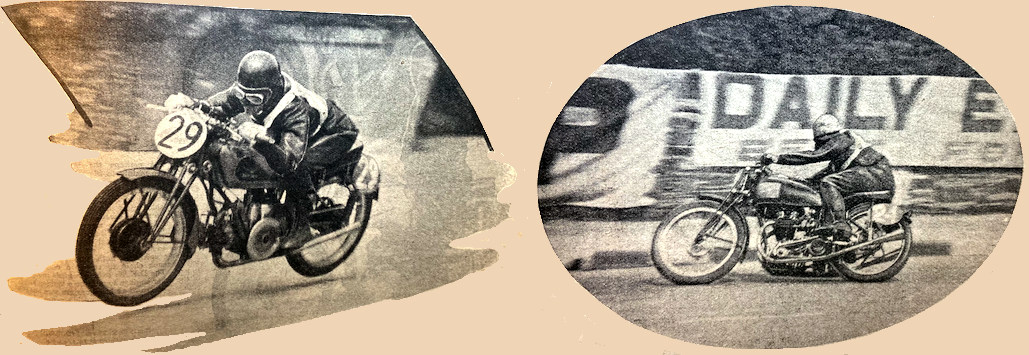

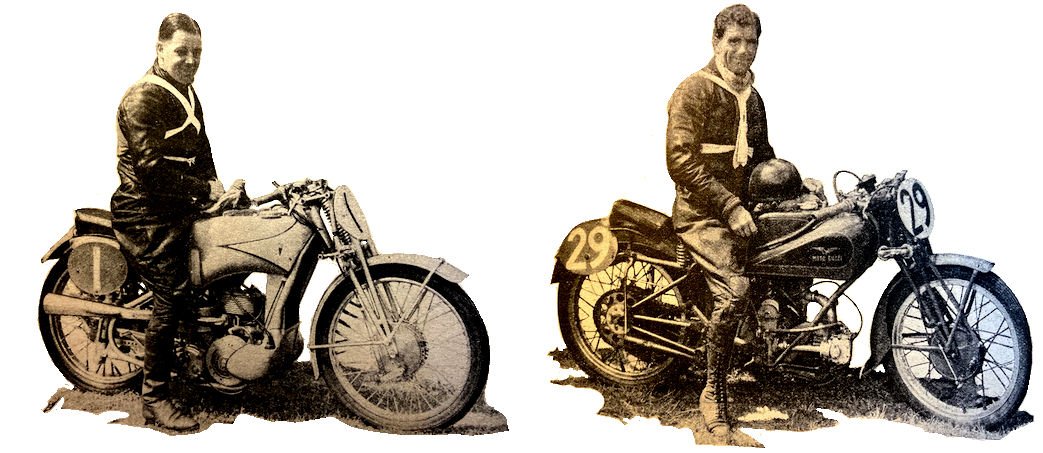

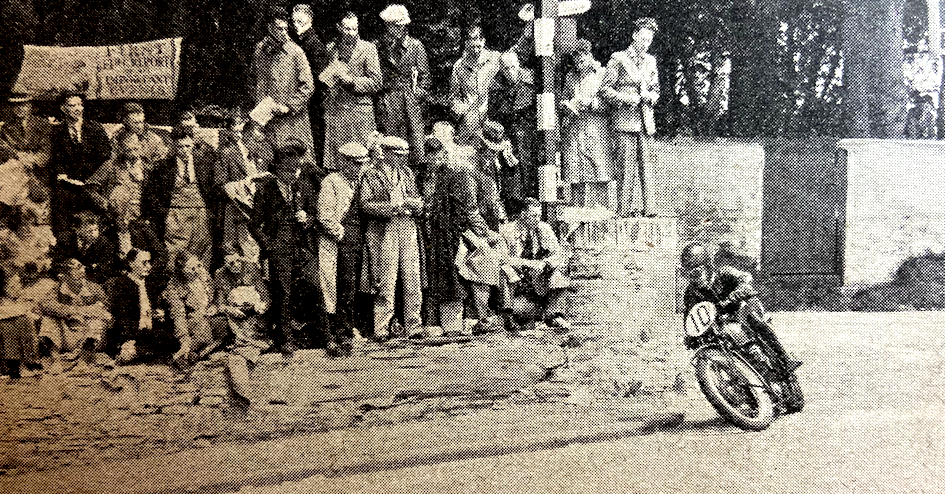

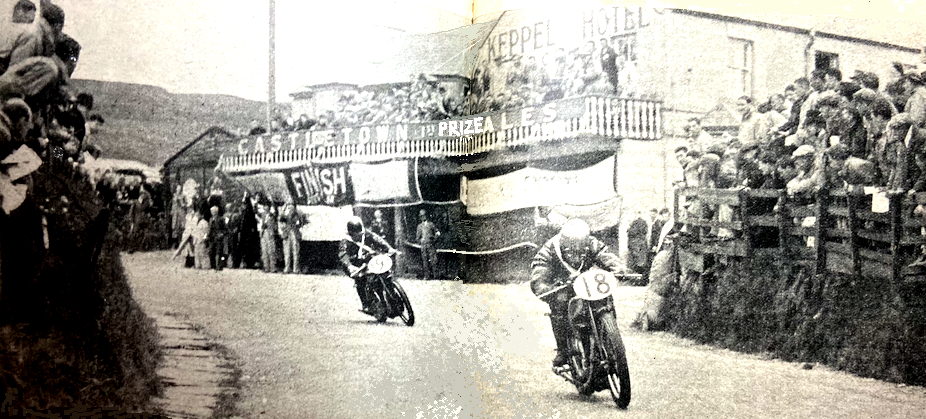

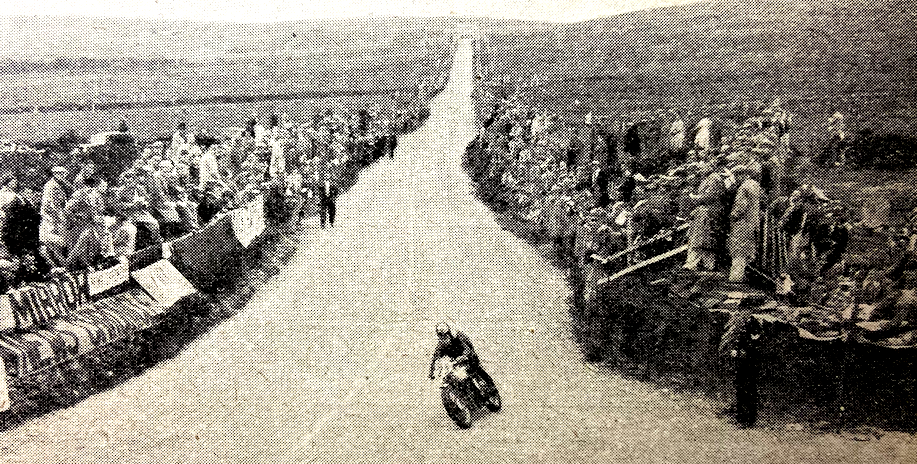

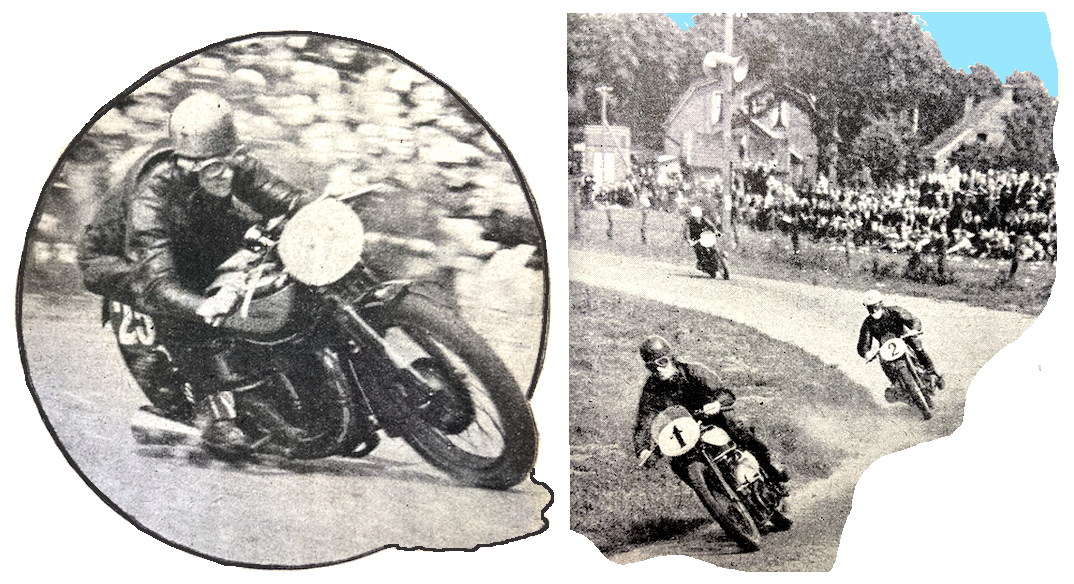

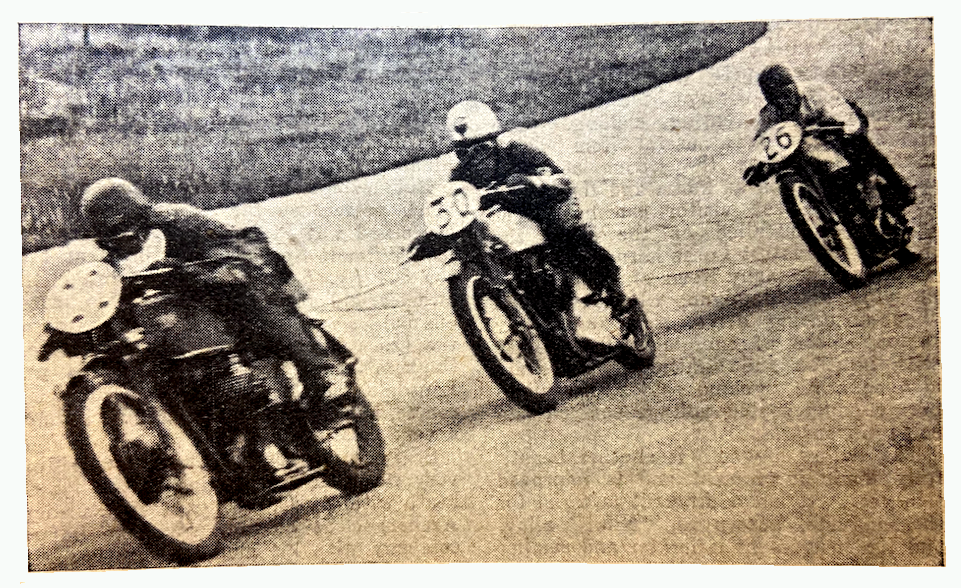

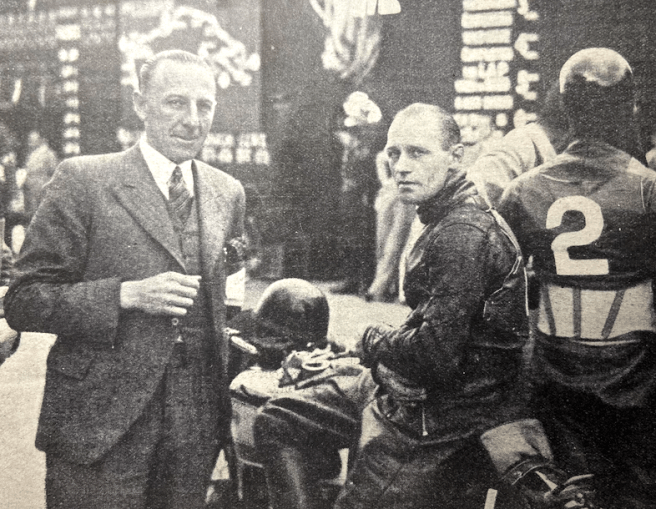

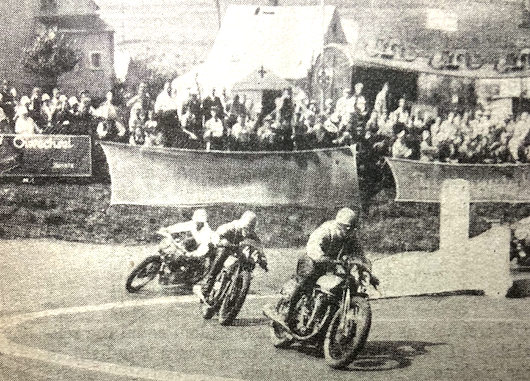

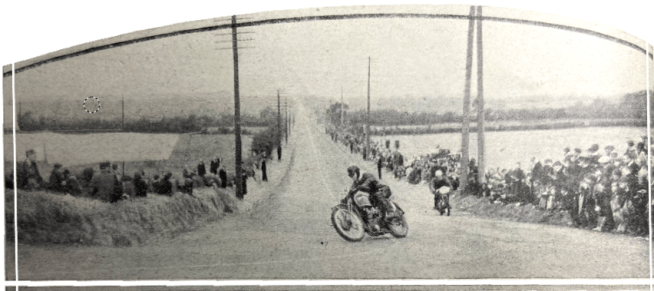

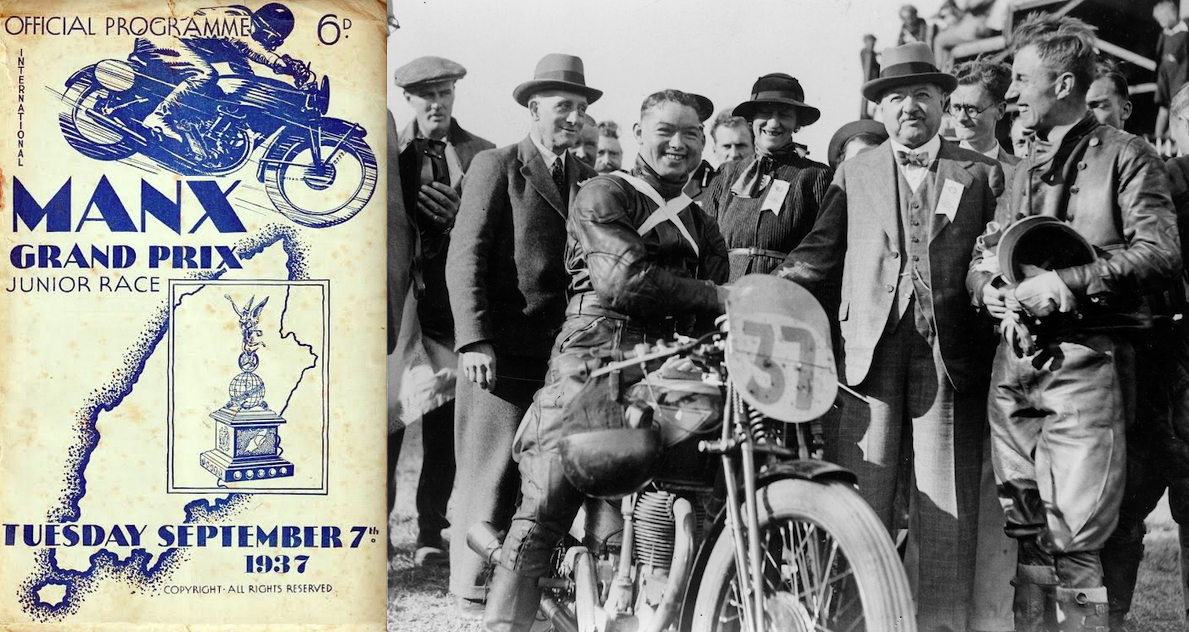

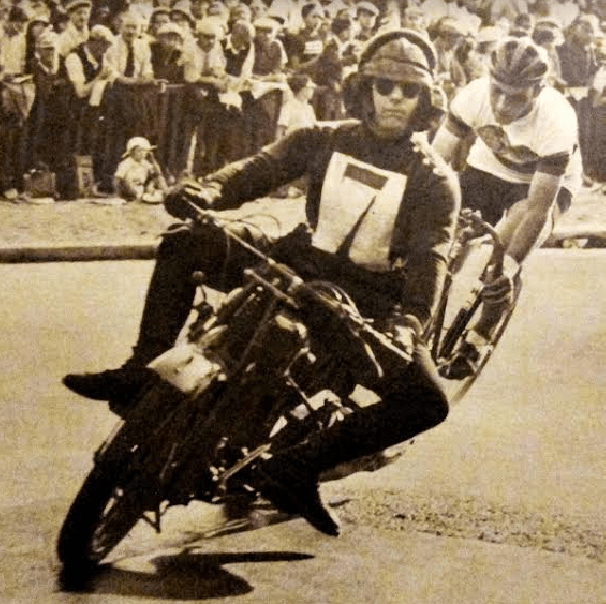

“STANLEY WOODS (VELOCETTE) won the Junior race in the South Australian Centenary TT at a speed of 79.9mph. Clem Foster (Norton) won the Senior race at 83mph…a 1,000cc Ariel Four and sidecar driven by R Badger won the sidecar class at 71mph.”

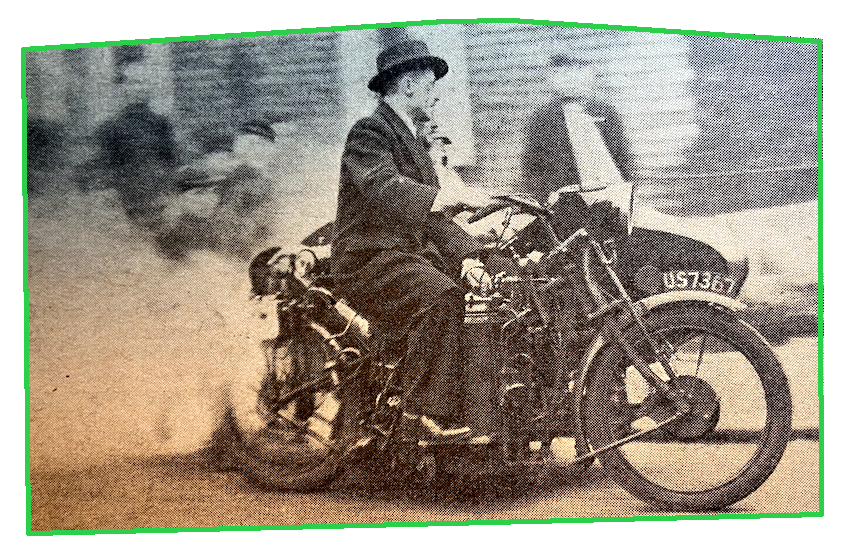

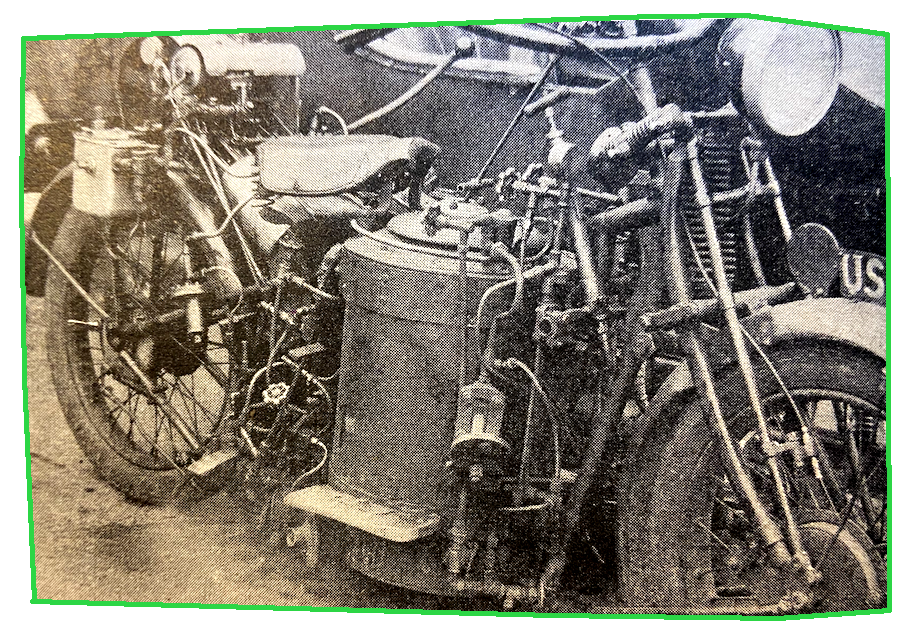

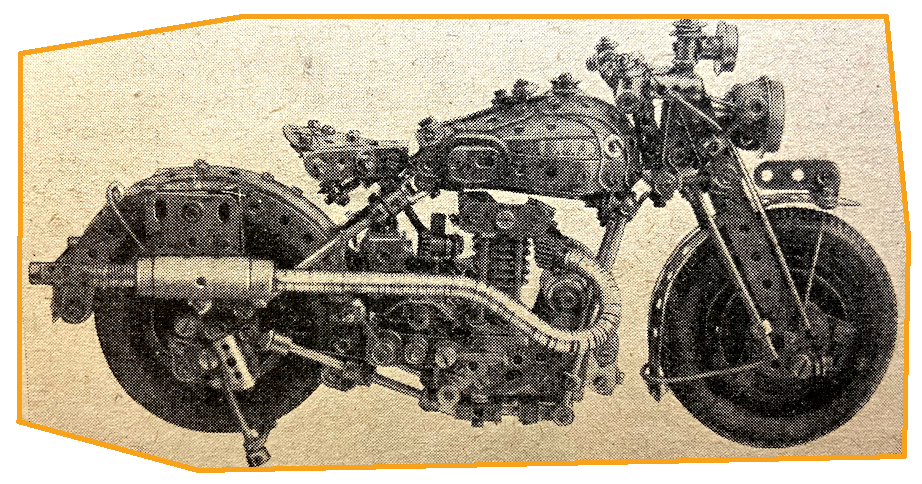

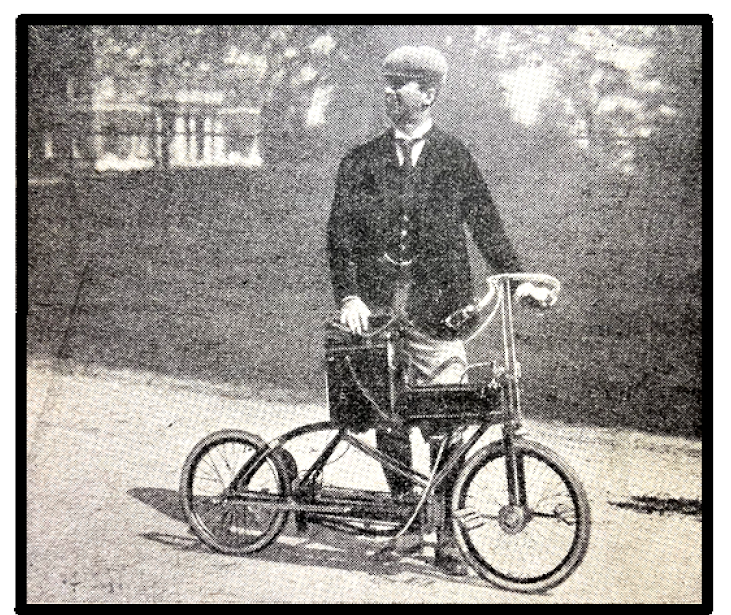

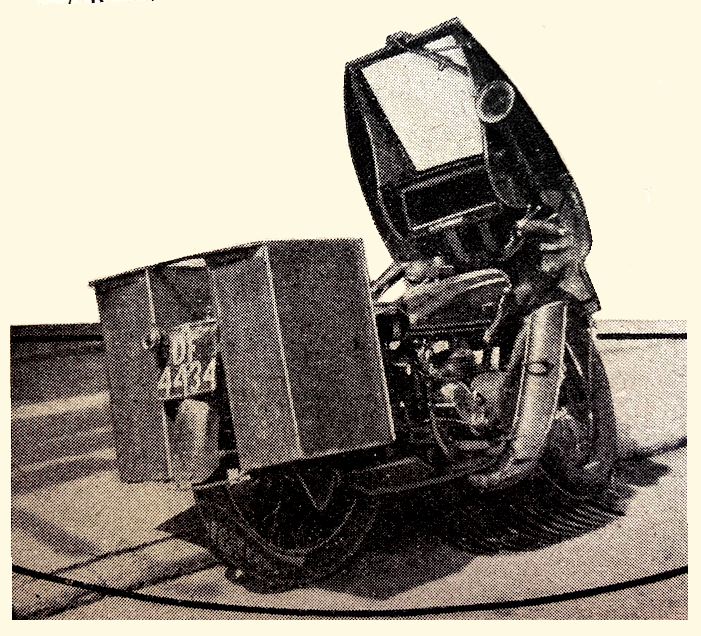

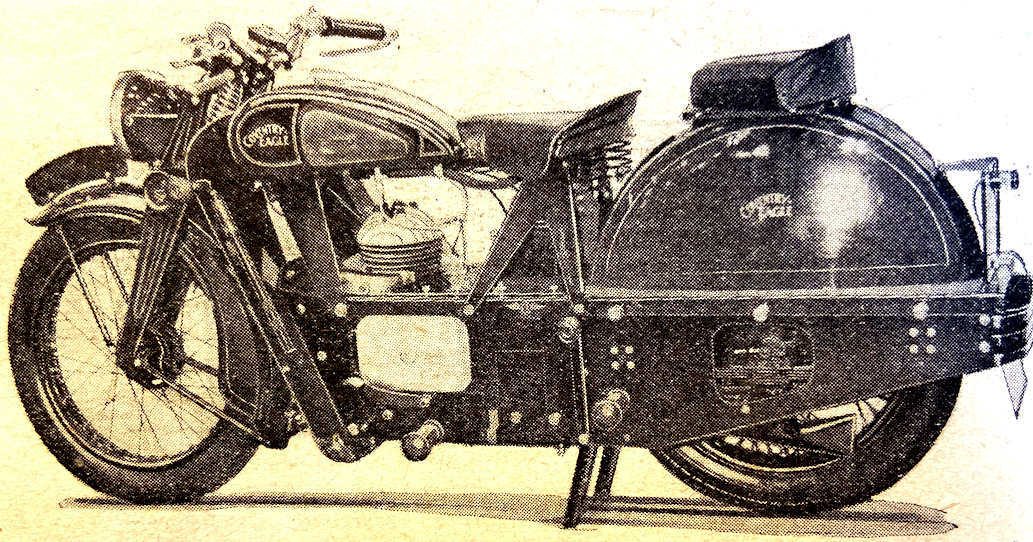

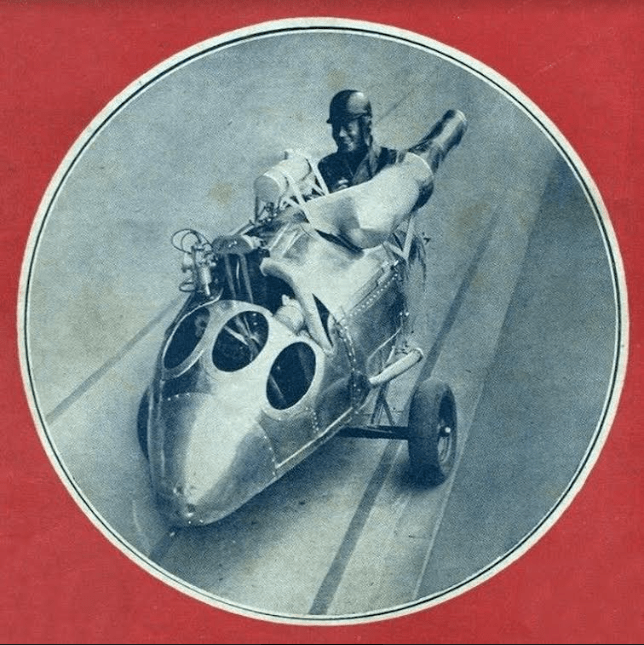

“SOME TIME AGO a picture appeared in The Motor Cycle of a steam-driven sidecar outfit built by Mr James Sadler, a Glasgow engineer. It had been designed, after a series of experiments, purely as a hobby. Last week-end it made its bow to London under the auspices of Marble Arch Motor Supplies at their Camberwell showrooms. When the offer was made last Monday to go out on Mr Sadler’s outfit I was more than thrilled. Time did not permit an extensive test, so I had to be content with a ran round the houses in South London. Nevertheless, although the machine is only a hobby, and an experiment at that, I left it with feelings of regret that steam has been so neglected as a means of comfortable motoring on three and even two wheels. After a brief description of the general layout, Mr Sadler jumped into the side-car while I found a way into the saddle over a maze of pipes, valves and gauges. Between my legs was the high-pressure tube boiler, with a head of something like 200psi of superheated steam inside it. Behind me, over the rear wheel, was the twin-cylinder double-acting engine, coupled direct to the rear wheel by chain. Slightly behind any left arm was the forward-and-reverse lever, while in the middle, on top of the boiler, was the steam valve, or throttle control. To start, all one had to do was to set the lever to the forward position and then manipulate the steam valve. Quite gently, but with a feeling of extreme power, we surged forward. That feeling of terrific power at 1mph or less was most extraordinary. No juggling with clutch, throttle and brake controls—one just operated the outfit on the steam valve alone. The outfit accelerated rapidly in a delightfully smooth and effortless manner. If one wished to stop, one simply reversed the lever and braked on the engine. Incidentally, I found the outfit quite easy to drive in reverse.

As regards actual speed, something like 30mph could be attained with a 4001b pressure in the boiler. The outfit is built up from old motor cycle parts in a more or less orthodox frame. The boiler, carried in the centre of the frame, is of the fired tube type, designed to work at 400psi. It is fired by a controlled paraffin burner, fed from two high-pressure cylinders running at nearly 200psi. The pressure in these cylinders is maintained automatically by steam. The steam from the boiler is super-heated by means of a seven-foot spiral pipe running in the flame of the burner. It then passes to the high-pressure twin-cylinder, double-acting engine mounted horizontally on a sub-frame over the rear wheel. The engine has a bore and stroke of 64×89.5mm, and is of the normal slide valve type. A steam lubricator sees to the lubrication of the pistons. Another essential fitment is the donkey pump that injects water into the boiler. Should the water level in the boiler drop, the burner is automatically shut off. A four-cylinder high-speed miniature steam engine with a bore and stroke of 25.5×25.5mm drives the dynamo mounted on the front of the sidecar chassis. Under the seat of the sidecar are situated the paraffin tank (8gal) and the water tank (10gal). On a long run the consumption amounts to approximately 25mpg for both water and fuel, so that the outfit has a range of roughly 200 miles.”—Ambleside

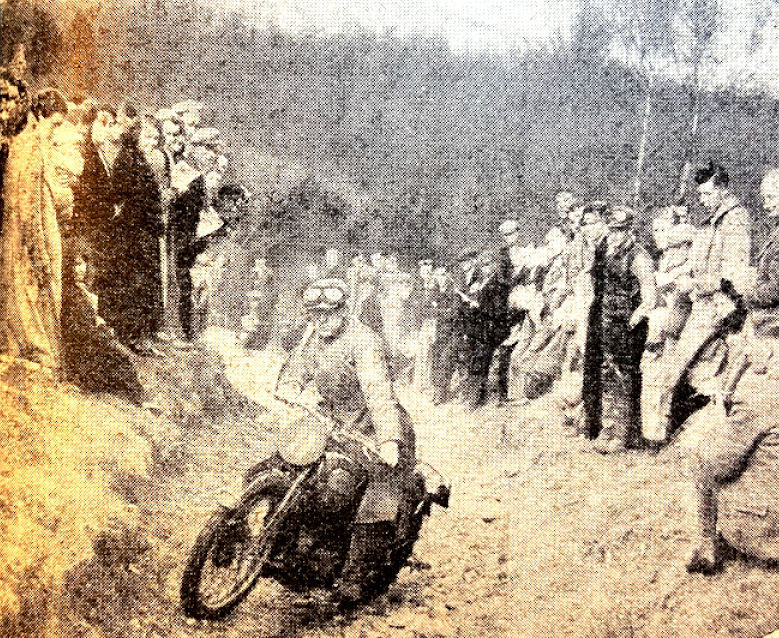

“‘SPECTATORS WILL NOT BE allowed on the course this year; competitors will only be admitted to the grounds on the production of a printed pass.’ Thus runs an official statement covering the Sunbeam Championship Trial to be held at the end of this month. The reason for the decision is the amount of litter left on the course—a private one—when the event was held last year. Unfortunately the club concerned is by no means the only one to suffer at the hands of spectators. It is a regrettable fact that much of the prejudice that has arisen over trials is the result of thoughtless actions on the part of spectators. It is merely a few black sheep who cause the trouble. How can their activities be curbed? The Sunbeam Club is adopting a method which is simple in cases where enclosed ground is used, but it means that the orderly as well as the unruly are debarred from watching the sport they love. We suggest that much good might result if organisers pressed into service some of the spectators, making them officials for the day and giving them as their sole job the task of controlling crowds.”

“LITTLE BIRD WHISPERED to me last week that the Ministry of Transport is going to construct a giant motor road along the east and south coasts from Bournemouth to Cromer. Alleged motive, to furnish a free run in time of war for motor lorries mounted with anti-aircraft guns. Hope it’s true; we could do with a coast road right round these islands, always provided it was pushed inland half a mile or so where the coast is really lovely, and only allowed to hug, the beach where the coast is dull. But I don’t believe the little bird; I doubt whether a motor lorry would ever form a satisfactory mounting for a gun which will have to fling a shell up to 25,000ft.”—Ixion

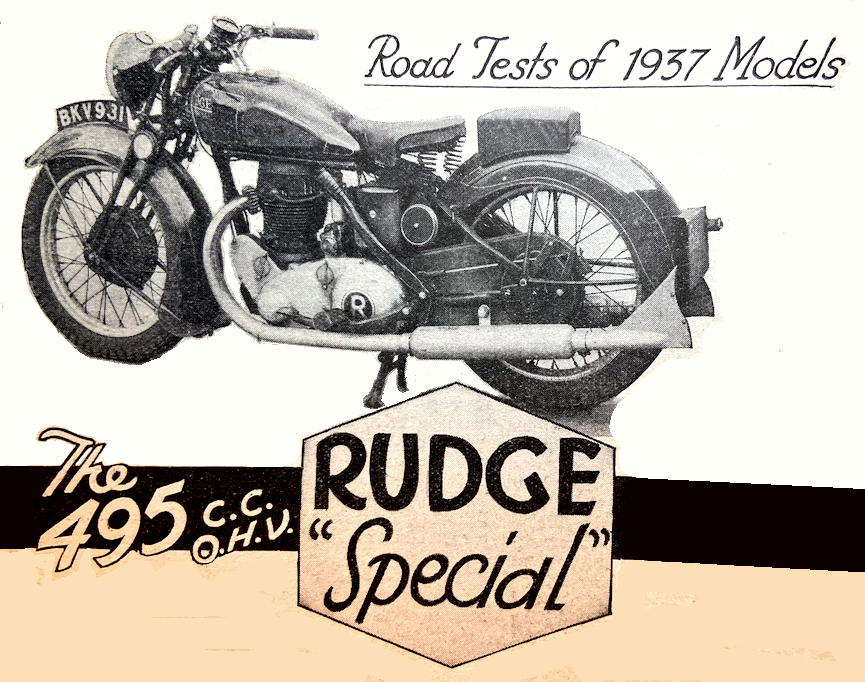

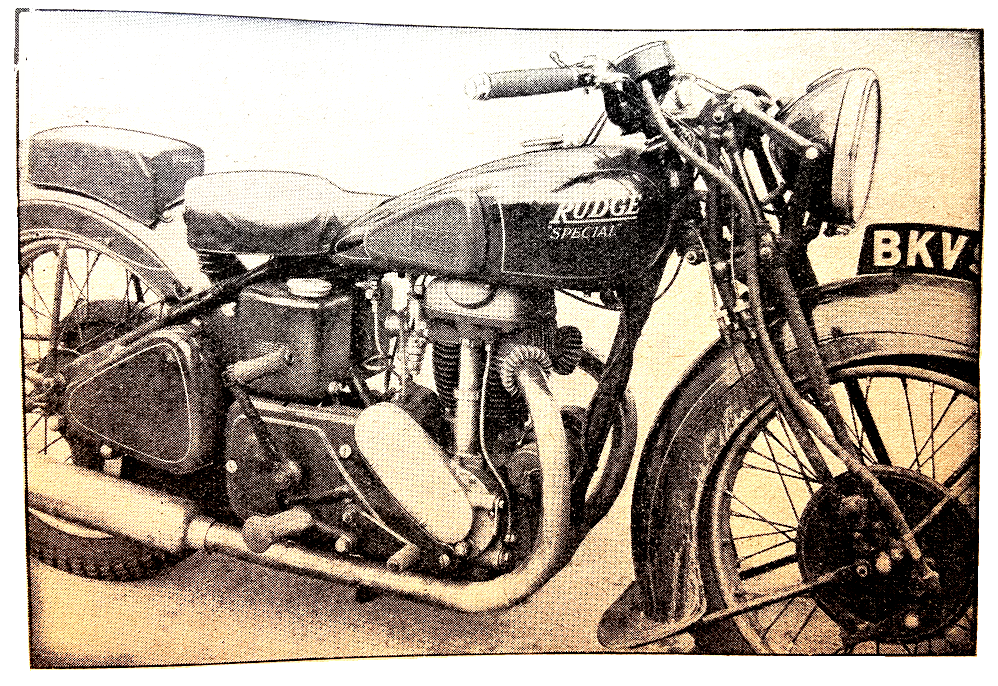

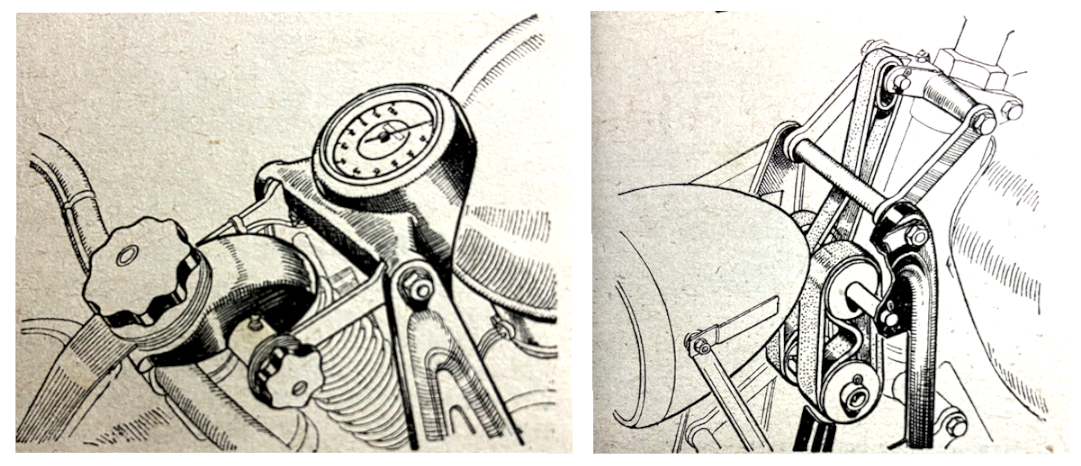

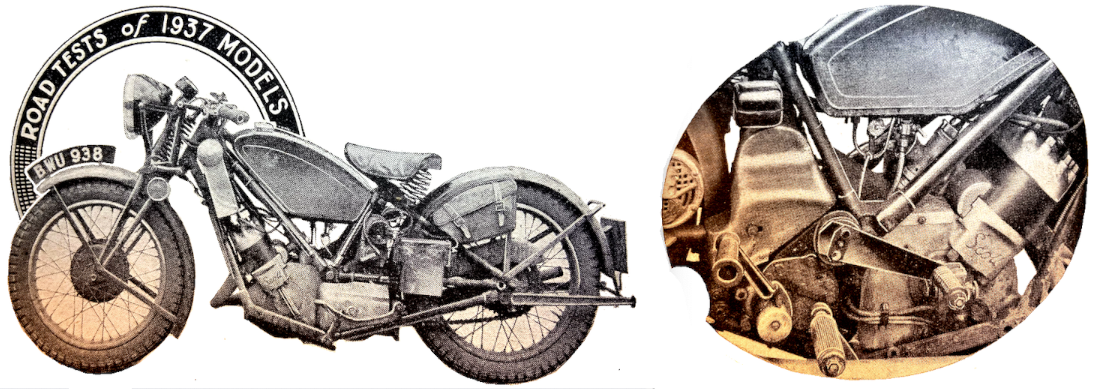

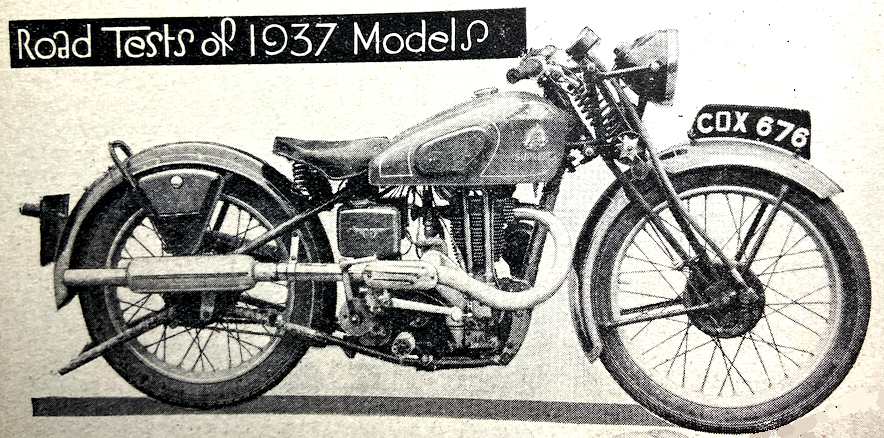

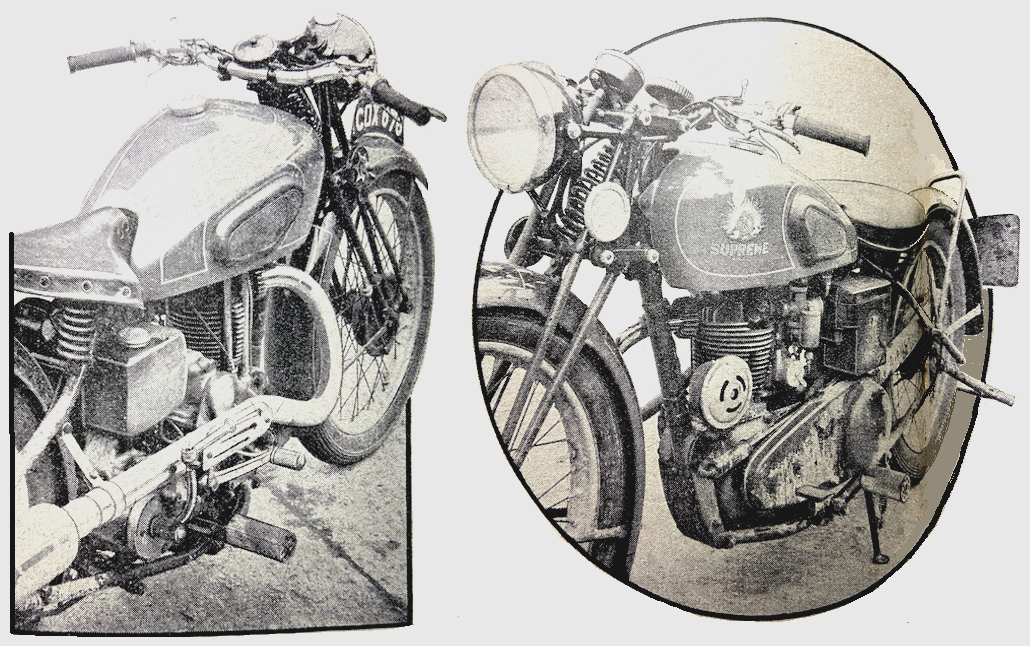

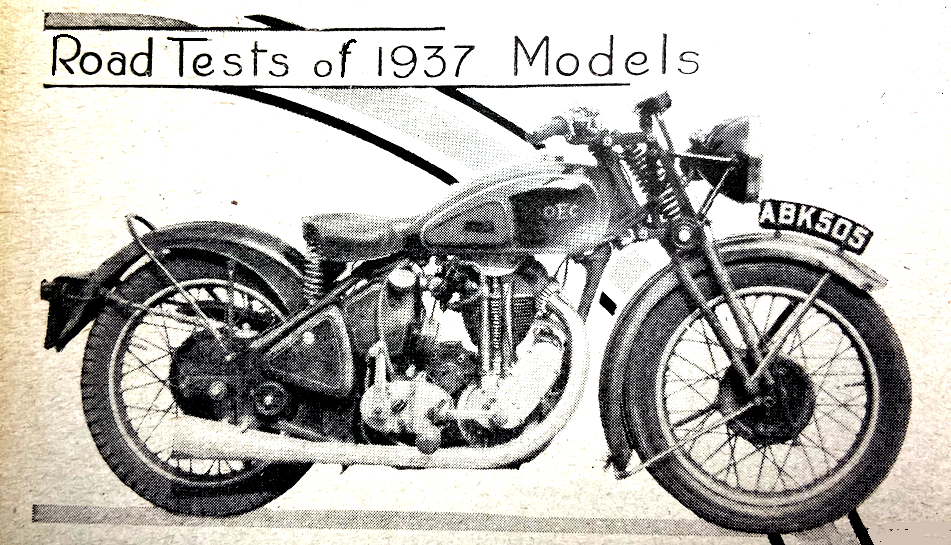

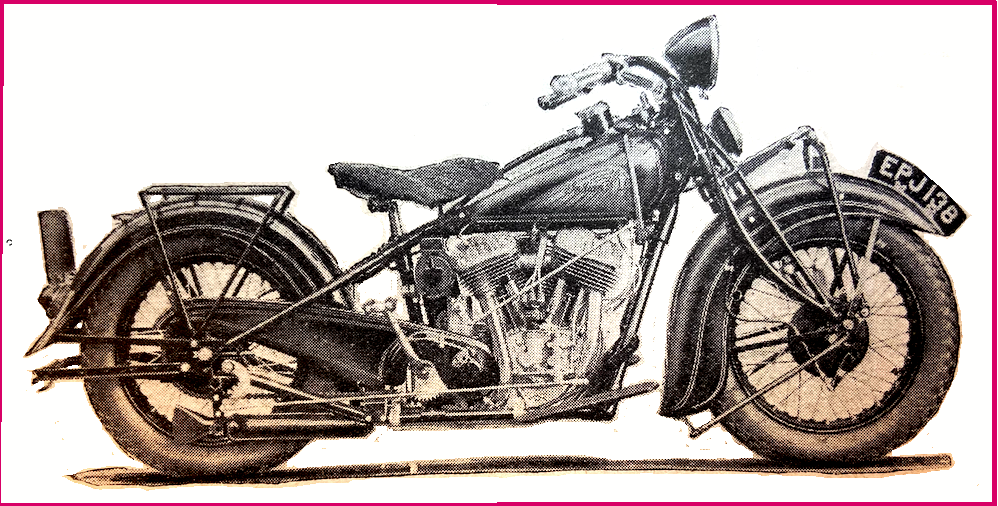

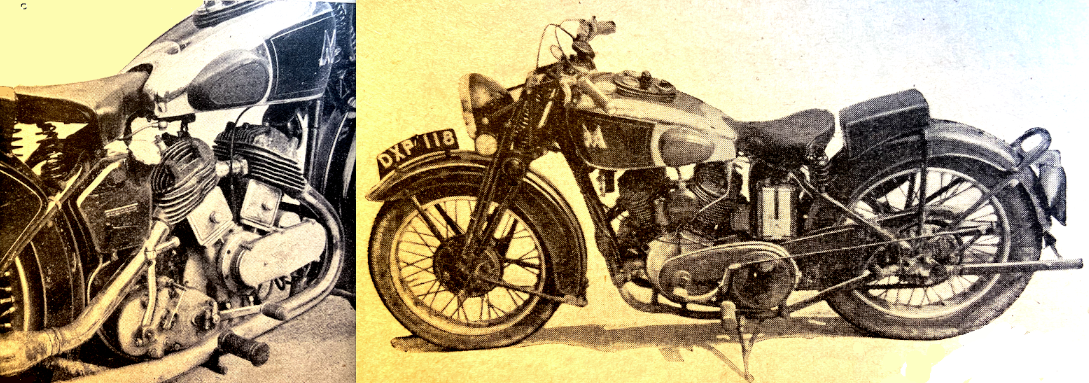

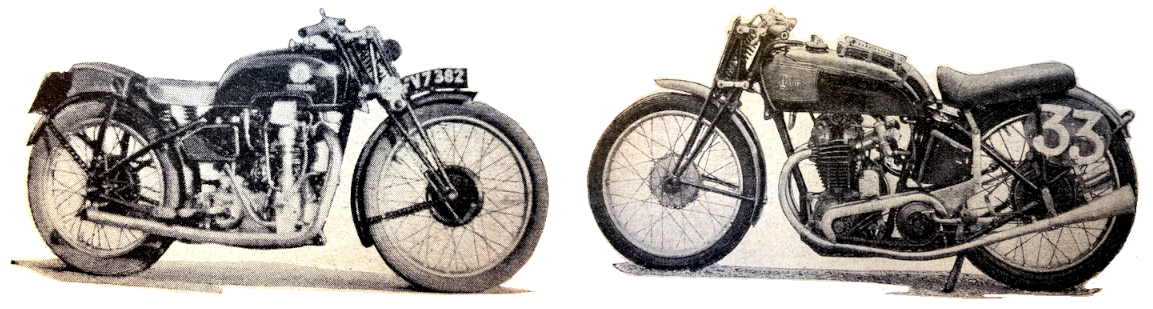

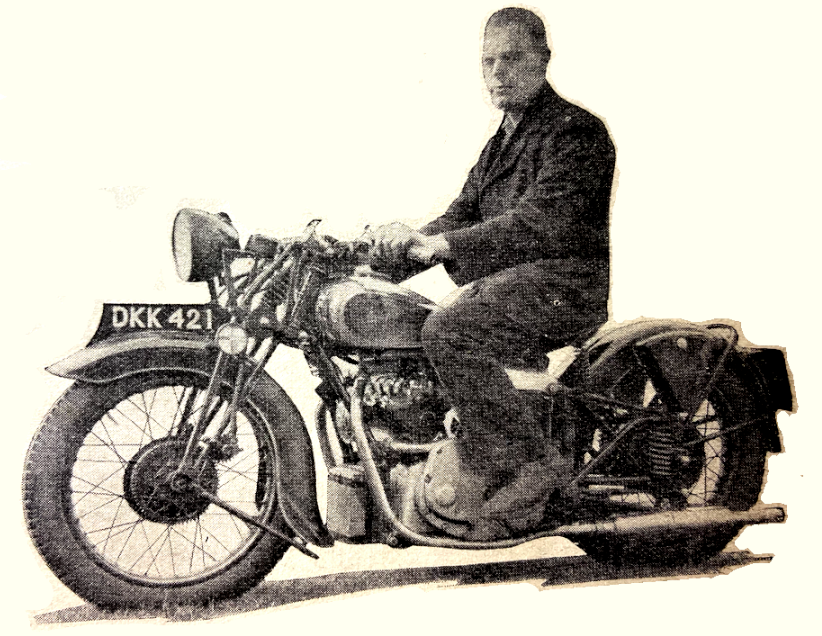

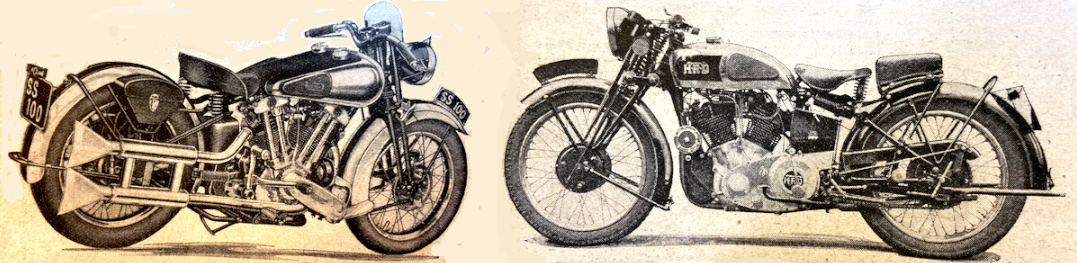

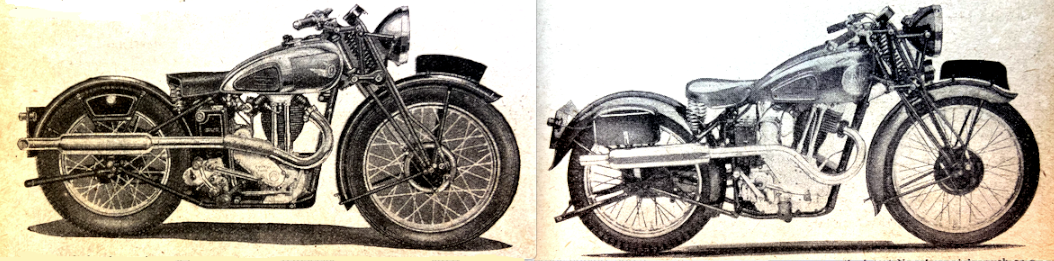

“THE RUDGE SPECIAL has many of the good points of its speedier prototypes that have won fame on road and track. It has excellent steering at all speeds, as well as superb brakes and road-holding. It is also exceptionally silent, both mechanically and as regards the exhaust. This year the riding position has been altered slightly, with the result that comfort has been considerably improved. The footrests, pedals and handlebar controls are all well placed. Starting was a comparatively simple matter if the decompressor was used. Otherwise the kick-starter was liable to kick back viciously. The engine balance was of the highest order, vibration being almost completely absent. All the controls worked smoothly and lightly, and in this connection the clutch deserves special mention. On the other hand, while gear changing was easy between second, third and top gear ratios. a silent change from bottom to second or vice versa is difficult on account of the big divergence in the ratios. Bottom gear is sufficiently low to enable trials hills to be tackled successfully, while the remaining ratios are particularly suitable for fast riding over main roads. The engine seems to revel in high revs, yet at the same time it will slog without complaint. The maximum speeds of 25, 49, 63 and 70mph in the various gears were obtained under adverse conditions against a stiffish wind, and while valve bounce would probably preclude the speeds in the three lower gears being improved, there is no doubt. that the top gear reading could have been bettered by two or three mph. On good main roads, clear of traffic, it was possible to maintain a steady 65mph, winch is unusually having regard to the machine’s maximum speed. The engine would stand any amount of hard driving, both at high and low speeds. At all speeds the steering was outstandingly good. It is of the light variety without being unduly so, and at high speeds imparts a feeling of great security. The road-holding was also admirable, particularly on fast corners. The Rudge gives the impression of deciding for itself the right amount of bank necessary for each corner. On greasy and loose surfaces there was a minimum of wheel hop—a point for which the Dunlop Universal tyres were no doubt partly responsible. Following the usual practice of the Rudge company, the Special is fitted with coupled brakes. Whether the front brake was used on its own or in conjunction with the rear brake, braking was at al1 times smooth and certain. Indeed, such confidence was inspired by the brakes that even on skiddy surfaces their application called for no special caution. After a prolonged test the various joints in the upper half of the engine remained free from oil leaks; a certain amount of seepage took place though the case joints. Particular mention should be made of the mudguarding. After many miles of wet roads covered at high cruising speeds, the engine and various other parts remained remarkably free from mud and grit. A 6-volt Miller dynamo, driven by separate chain running in an oil bath, is fitted, and the head lamp provides a narrow beam of unusual length. At all times the Rudge Special gave the thrill of smooth, silky power. On light throttle it was unusually quiet, while even on full throttle there was very little increase of exhaust noise. The oil consumption was negligible, a remark which almost applies to the petrol consumption! At a maintained speed of 40mph the Special’s consumption amounted to 91.2mpg. Towards the end of the test there was evidence of a weak mixture, a fact which undoubtedly- affected the acceleration figures in the various ratios. A special feature of the Rudge is a hand-operated central prop-stand. It requires very little effort to operate and can be used by the rider when sitting in the saddle. Care must be taken if the machine is ridden off the stand, for the hand lever is liable to come down and trap the rider’s left foot. The Rudge Special is a very interesting ‘standard’ machine, since it possesses numerous sporting traits. The very complete specification includes a mudguard pad and a speedometer. A small but interesting refinement is that all the major nuts on the machine are domed. Altogether the machine forms a very workmanlike and desirable roadster. “

“WE REGRET TO HAVE to say so, but the whole tendency in the trials world is towards what may be described as ‘softness’. Except for MCC events there are now hardly any long-distance trials. ‘Make them short and snappy’ has been the cry. We know that there have been good reasons for this, particularly during the lean years of the recent past, but we have seen with regret that many of those taking part in trials are not motor cyclists in the proper sense of the term—they come to the start by train or in cars and, when the event is over, return in similar fashion. True, trials have developed motor cycles which are none too good for ordinary road work, but there is also a proportion of present-day trials riders who have grown soft; they are not motor cyclists, but jockeys. Some of these will say that they live only for the actual sport of riding through and up observed sections. The fact is that present-day trials are breeding this type of man—the jockey as opposed to the true enthusiastic motor cyclist, and it is a very great pity.”

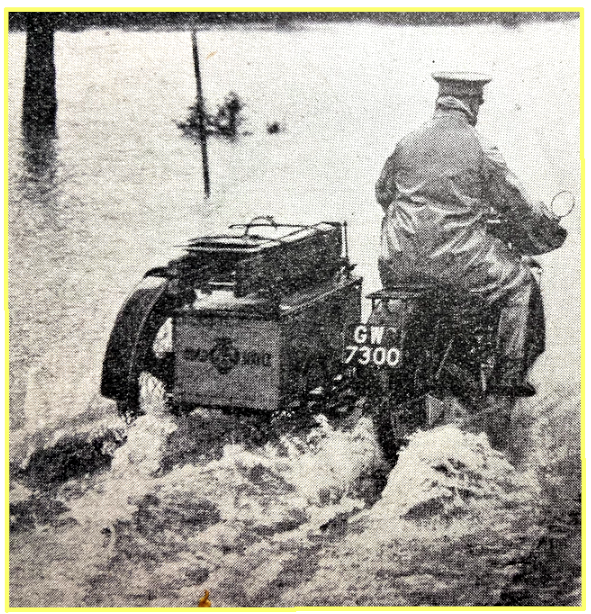

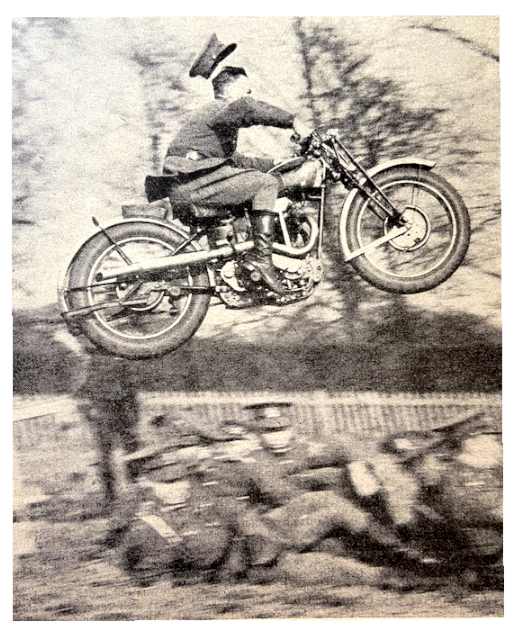

“STRIKING PROOF OF THE inherent safety of the motor cycle and its value in police work is given by figures quoted in the December issue of The Garda Review, the official organ of the Irish Free State Police Force. The motor cycle patrols were introduced in June 1926, and from that date until October 1936, a total of approximately 1,680,000 miles were covered without a single accident for which the drivers were either directly or indirectly responsible. The patrols were on the road every day from 8am to 12pm, and their duties ranged from chasing speedsters to directing traffic. A record to be proud of!”

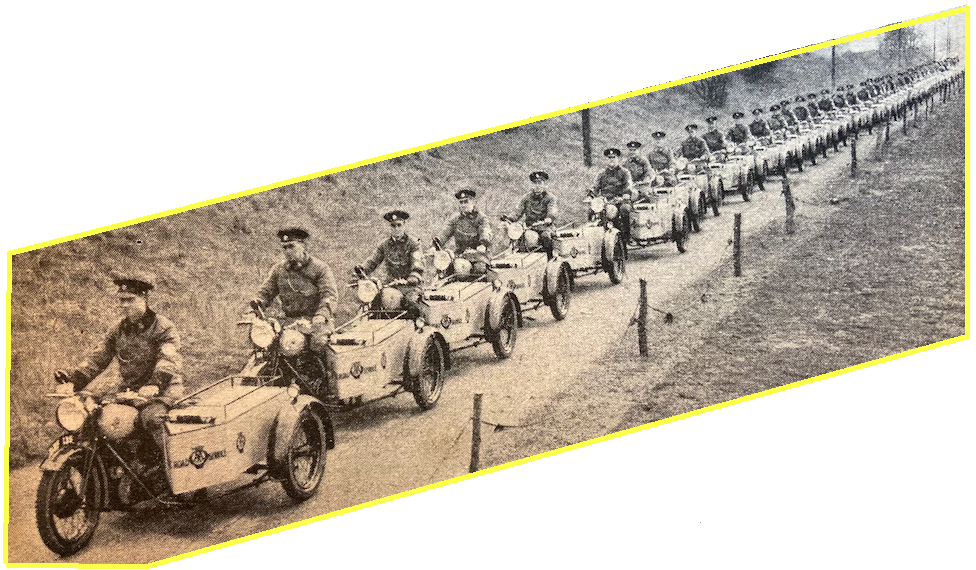

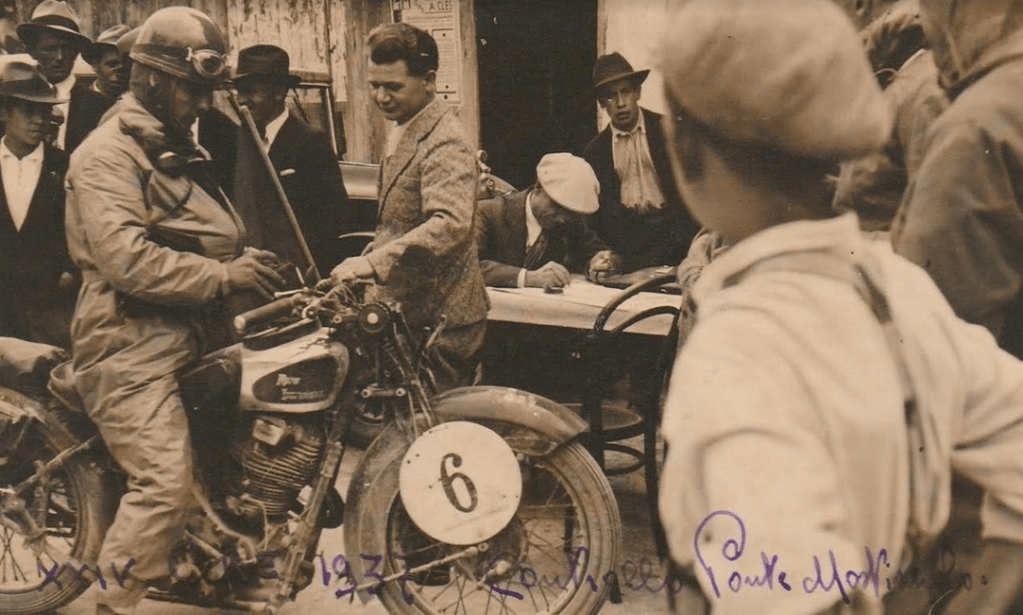

“THE FRENCH MILITARY authorities have purchased 1,000 750cc sidecar outfits.” That’s all The Motor Cycle had to say about the order but there’s a good chance they were the latest WD model from the Belgian company Gillet Herstal. The Gillet Herstal 720 AB was powered by a 728cc two-stroke engine producing 23hp and driving through a four-speed box with a reverse gear and sidecar-wheel drive; fuel consumption was a dismal 14.2mpg. the ‘AB’ stood for Armée Belge; there was also an AF model for the French army—France ordered a total of 1,500 720AF solos to be fitted with French-made Bernadet sidecars. Fewer than 800 ABs and AFs were produced; following the German invasion of Belgium they were requisitioned by the Wehrmacht.

“THE HUNGARIAN GOVERNMENT has introduced legislation designed to stimulate the production of home-produced petrol from coal.”

“A NEW PETROL-FROM-COAL plant is to be established at Pencoed, Bridgend (South Wales) by the Low Temperature Carbonisation Company.”

A GERMAN FIRM won a £600,000 contract to build a coal-from-oil plant in Manchuko, a Japanese puppet state in China. .

“THE DUKE OF KENT is to open a new oil-from-coal plant at Bolsover (Derbyshire) on April 14th.”

LOW TEMPERATURE CARBONISATION Ltd opened a factory able to produce 12 million gallons of oil and petrol and year from coal. The company claimed to be able to meet 1% of Britain’s oil and petrol needs.

“LAST YEAR, 112,000 tons of petrol were produced from British coal—about 2½ to 3% of the total consumed.”

“‘£60,000 WOULD PROVIDE enough plant to carbonise the whole of the domestic fuel used in this country. From this amount of coal we should derive about 5,000,000 tons of oil and petrol.’—Colonel WA Bristow.”

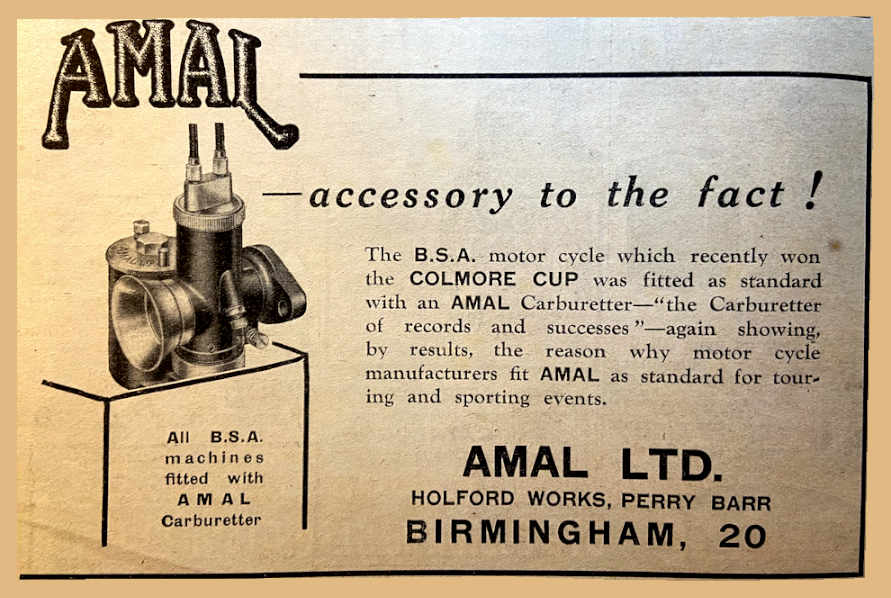

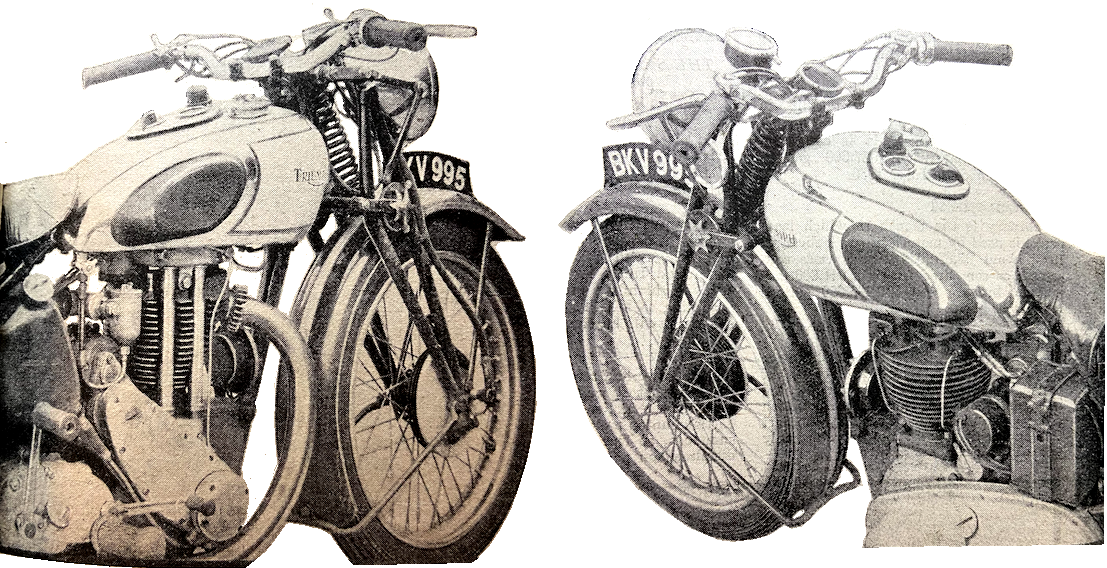

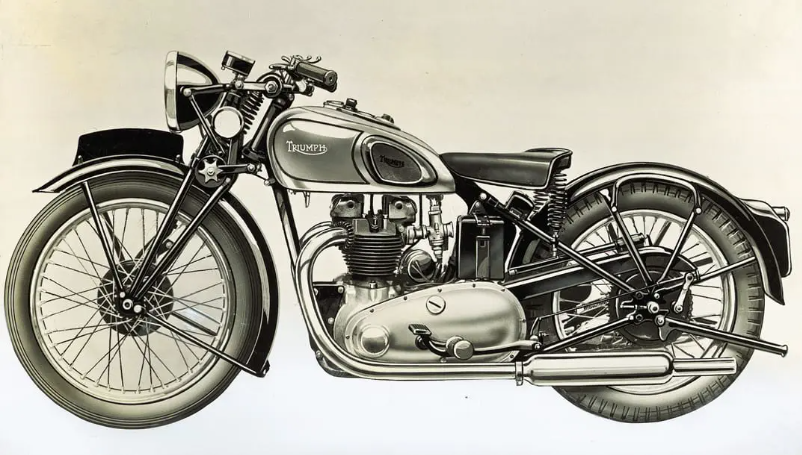

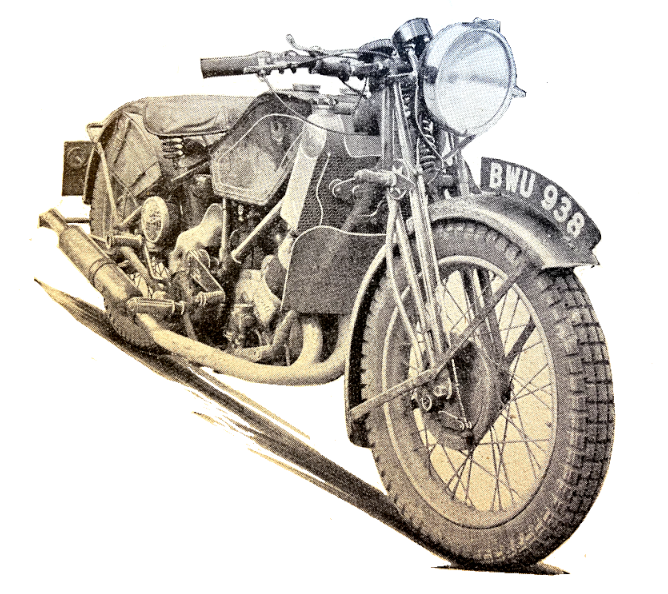

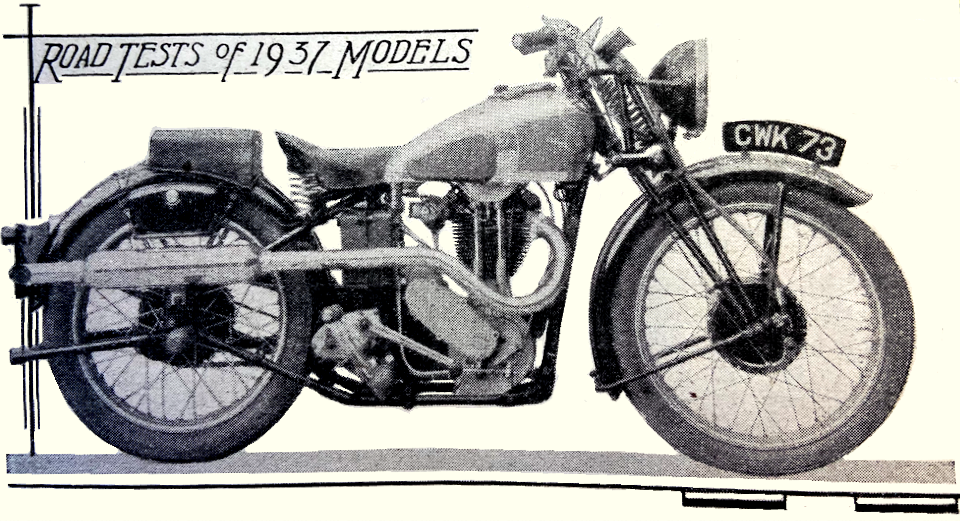

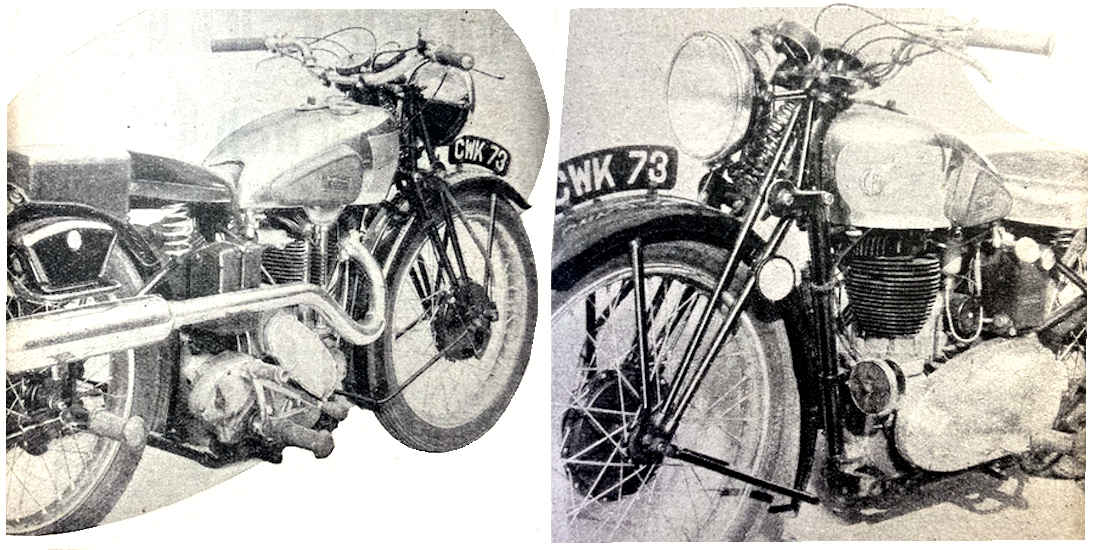

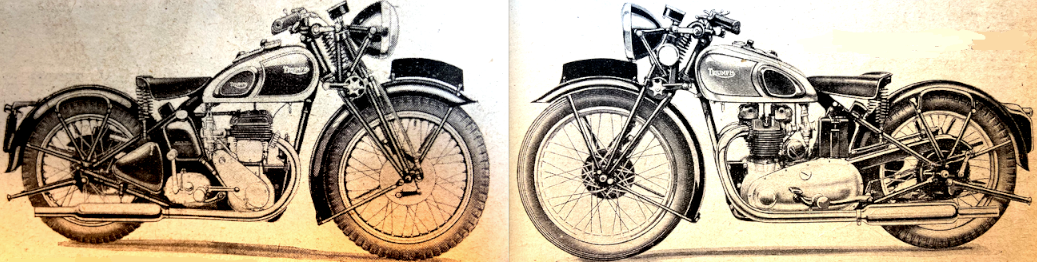

“EVEN IN THESE DAYS, a single-cylinder motor cycle with a genuinely high performance wedded to the smoothness and docility of a side-valve is some-thing of a rarity. Such ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ qualities are a feature of the latest Triumph Tiger 90. Since its introduction last year the Tiger 90 has come to be looked upon—and rightly so—as a specially tuned machine designed for the connoisseur and the hard rider alike. It is unusually swift, and yet at the same time it is extremely flexible and docile. Starting is a comparatively simple and effortless matter, thanks to a suitable kick-starter-engine ratio. Even when started from cold the engine idled perfectly, but there was a slight trace of a weakening of the mixture just off the pilot jet, and this at times caused spitting back and even stalling of the engine. To remedy this, the needle valve of the horizontal-jet Amal carburetter was raised one notch, and the slight richening of the mixture resulted in more even running with the throttle just off the tick-over setting. The riding position is designed for a person of normal height. The footrests, pedals and handlebars are correlated to a nicety, although the handlebars are a trifle wide for long-distance work. They are, however, rubber mounted, and all the controls are exceptionally well finished. Both clutch and front brake levers are of the racing type, and are conveniently placed on the bars. The large but graceful 3¼-gallon petrol tank, with its moulded-rubber knee-grips, does not interfere with the rider’s comfort. In fairness to the high-efficiency engine, the Triumph was run on an Ethyl fuel throughout the test. No doubt a mixture of 50-50 petrol-benzole would have given even better results, but at no time did the engine show signs of distress. On the contrary, it seemed to revel in hard work for mile after mile, without a trace of a knock. In fact, on fast main roads it was difficult to refrain from letting the Tiger have its head. The gear ratios are ideal for fast main-read work. All the ratios are suitably spaced, thus permitting a neat and fast change when required. Some riders might find the foot-change a trifle disconcerting at first. It works in an upward direction for the higher gears and downward for the low. This operation was a little uncertain when changing from third into top gear at speeds in the neighbourhood of 70mph. However, the selector mechanism is very precise and positive in action, and no one should have any difficulty after a few hours’ riding. Throughout its range the engine was delightfully smooth and remarkably free from vibration. It was lively without being unpleasantly so. The power output seemed to improve noticeably at speeds of over 50mph in top gear. At high speeds the Tiger gave the feeling of exceptional power without being unduly noisy. However, the exhaust note did change from a burble to a healthy but not obtrusive crackle when the throttle was well open. Because the power is more apparent at high speeds than is usual, the acceleration may not seem

outstanding. The best acceleration was obtained at speeds of over 50mph, and only began to tail off after 75. Third gear is an extremely useful ratio for fast work, and was a pleasure to use. Circumstances at the time of the test did not permit a two-way run for the timing of the maximum speed in top gear. The speed of 82mph was the mean of four runs against a stiff wind, and them is no doubt that the Tiger, fitted as it was with full electrical equipment, silencers, etc, was good for a genuine 85mph, if not more. At these speeds wind resistance plays a big part, and for this reason the Triumph’s performance was all the more creditable, because the rider had only limited opportunities of ‘getting down to it’, since no mudguard pad was fitted. While the bottom gear ratio is high enough to permit speeds of 35-40mph, it was.low enough to permit an effortless restart on a 1 in 5 gradient. In spite of a slightly weak mixture at small throttle openings the machine pulled admirably at slow speeds. In top gear it was possible to trickle along at 14mph without a trace of snatch. Naturally, when accelerating from this speed, the engine was liable to pink, a little if you throttle was opened it too quickly. As befits a model with a really sporting performance, the steering and roadholding were beyond reproach. The steering was of the positive type—very firm at low speeds, but becoming lighter higher up the speed range. At all times there was a complete absence of any pitching motion, even when the rear break was fiercely applied. Corners could be taken with a feeling of immense confidence. In fact, the whole machine inspired confidence. All the controls worked smoothly and lightly, calling for a minimum of effort. In this connection mention should be made of the clutch, which, although running in an oil-bath, suffers little from drag, even when the machine has been left overnight. It is exceptionally light, is very positive without being fierce, and requires little movement of the lever for complete withdrawal. Both brakes are of the ‘spongy’ type, and consequently very pleasant in action. The front brake could have been a little more positive—it was comparatively easy to bring the racing-type lever almost against the twist-grip. Both brakes were very safe in use at high speeds. At one period of the test the roads were ice-bound, but so excellent were the steering and road-holding of the Tiger that any natural nervousness was quickly allayed. Over this type of going the brakes were undoubtedly ideal, and this point should be remembered when considering the braking figure from 30mph. On wet roads the cleanliness of the engine testified to the efficiency of the mudguarding. The engine, too, with its enclosed valve gear, remained completely oil-tight. No signs of seepage at any of the crank case joints were present. To sum up, the Triumph Tiger 90 is a most attractive machine. It has a really first-class performance, coupled with excellent docility and flexibility.”

“TWO OR THREE YEARS ago if one wanted a motor cycle which was fast one had to put up with harsh running—that is, unless one bought a four-cylinder job. Inflexibility, poor slow-running, and lack of slogging power were what one paid for snap and speed. A change has been wrought. To-day there is quite a number of hot-stuff singles with Jekyll and Hyde characteristics. You get freedom from pinking, good top gear climbing and tick-tock running with a hyper-sports performance available at command. A year or two back I could name only about a couple of makes that combined the cart-horse with the race-horse. Now, to judge from other models I have ridden, there must be at least half a dozen.”

“THE Ministry of Transport avers that only 3% of accidents are due to road defects. The Oxfordshire surveyor avers that 60% of accidents could be prevented by eliminating elementary defects in the roads, and that if we modernised our entire road system, some 80% of the accidents could be averted. By ‘elementary defects’ he means blind corners and such like. Now the difference between 3 and 60% is fantastic, and off-hand one would judge that the county surveyor, in arms against a national authority, was wrong. But this surveyor has a definite title to respect. During 1936—a period when every other authority was registering an increased number of accidents—he halved the accidents in his area! Moreover, he halved his accidents by altering the road layout at points where experience showed that faulty road layout had produced crashes in the past. So we are driven to ask why the Ministry blames faulty road layout for a mere 3% of accidents. The answer is that it estimates on the basis of police reports. Now the police are trained to think in terms of people and guilt. They are nosing out criminals all the time. But the surveyor is thinking in terms of in material—skiddy surfaces, blanketed vision, and the like. So when the police report on a smash they are prone to talk of some failure of the human factor, which may or may not amount to criminal recklessness. But the surveyor asks why the human factor failed, and scans the road for a reason. I suspect that the Oxfordshire 60% is far nearer the truth than the Ministry’s 3%; and I hope we shall hear more of this dispute.”—Ixion

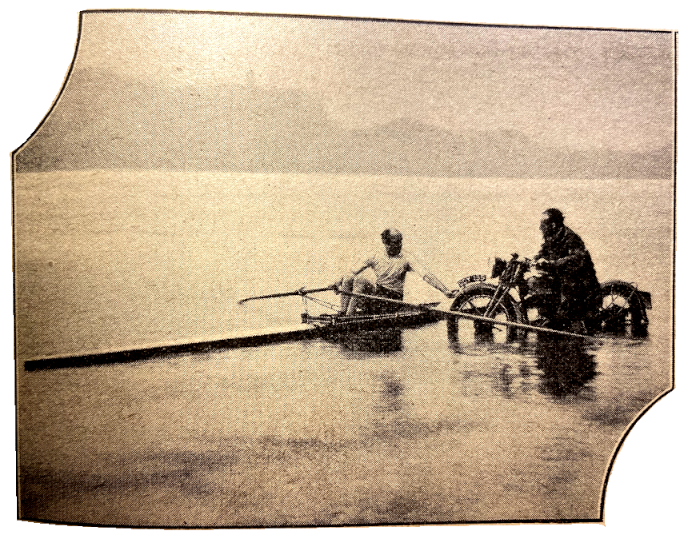

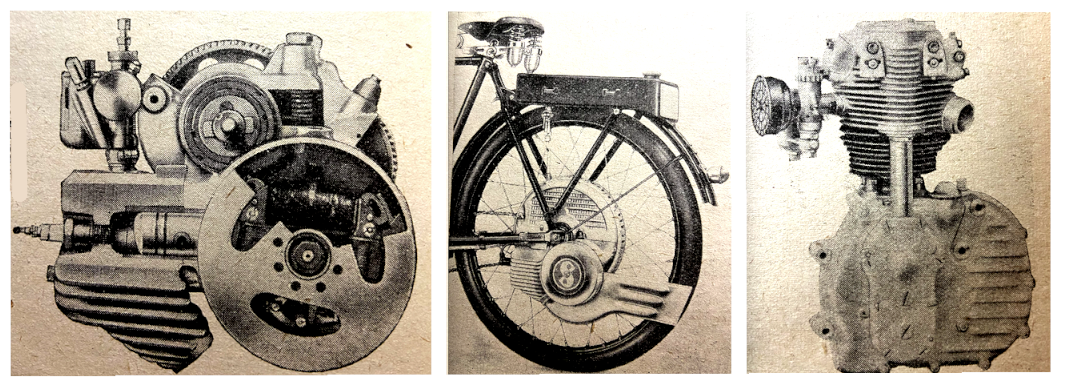

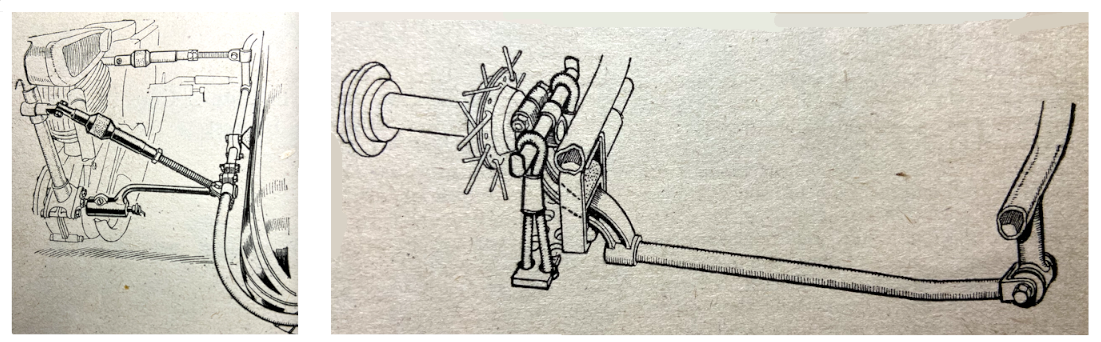

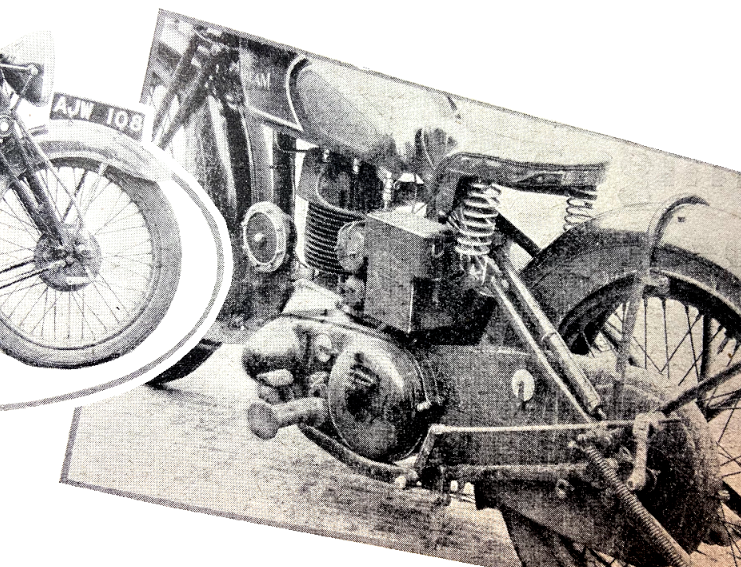

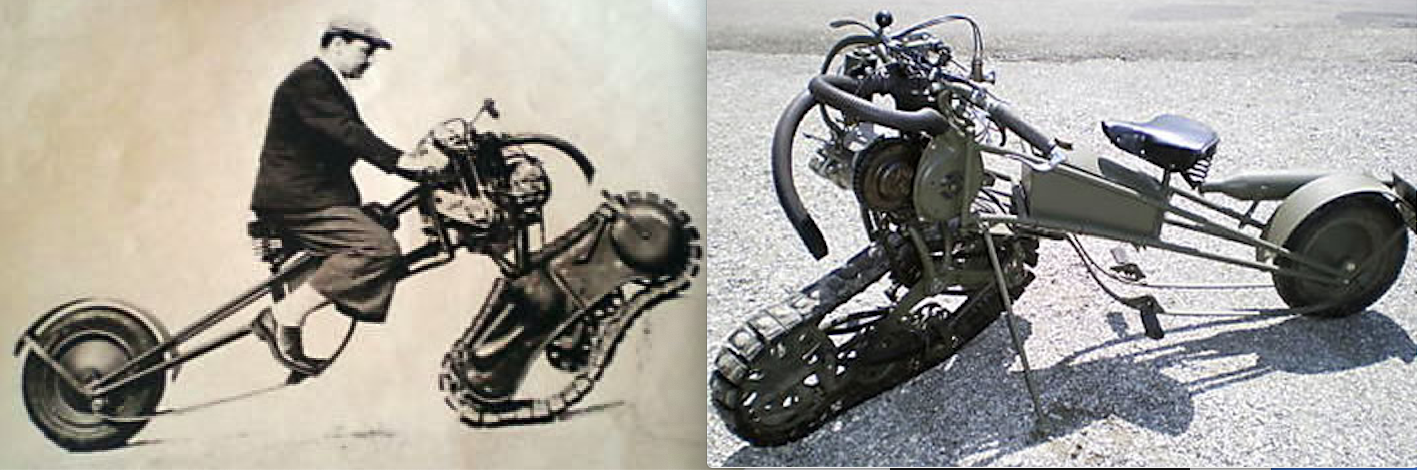

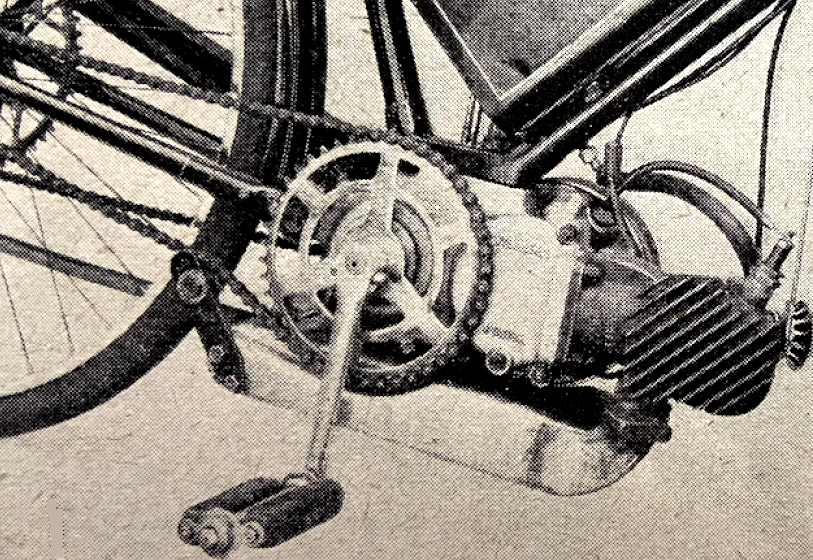

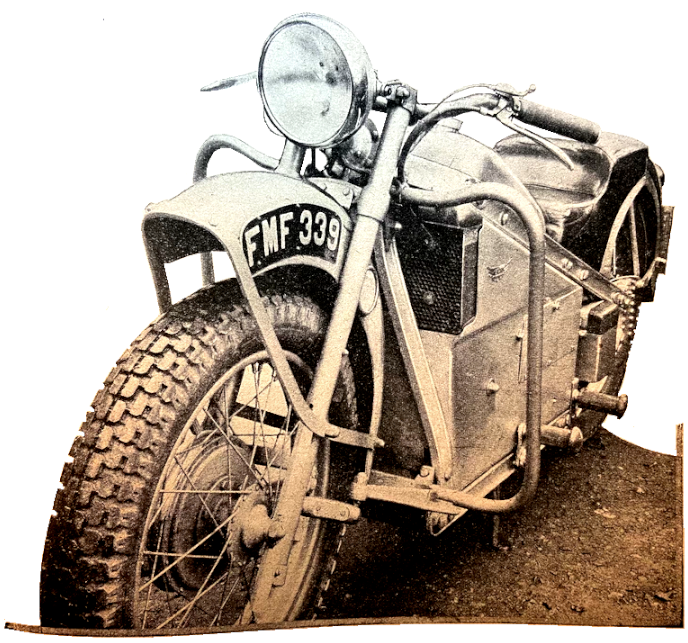

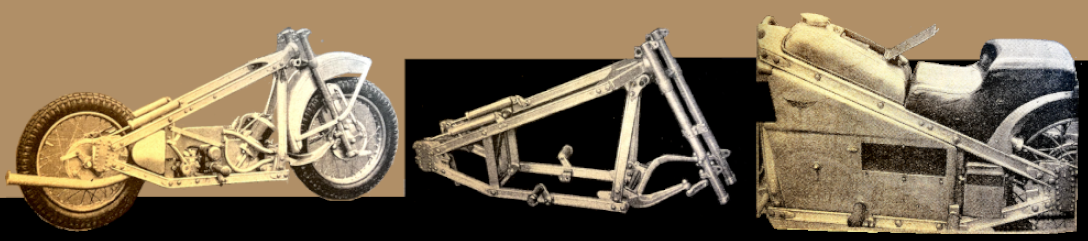

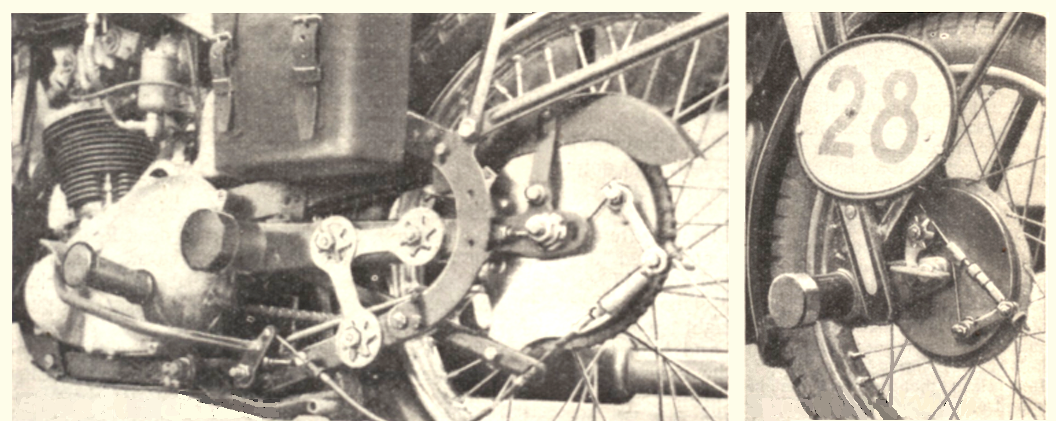

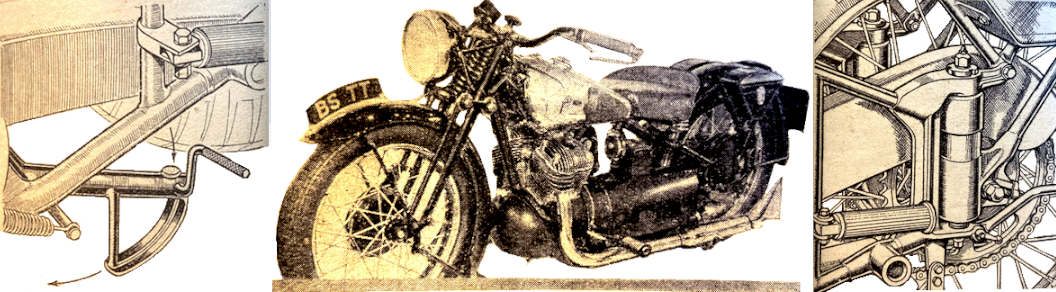

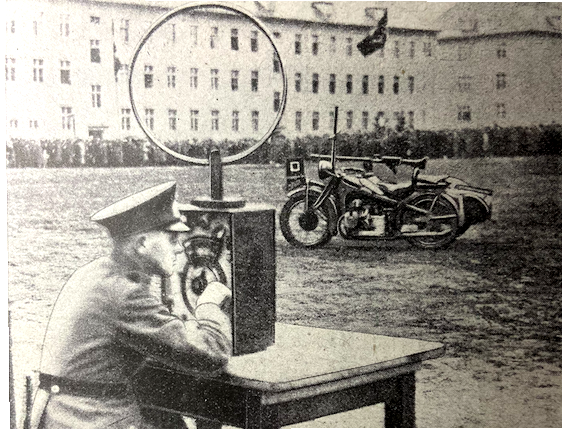

“THERE IS NOTHING NEW in the idea of driving both Wheels of a solo motor cycle, but there is room for some discussion as to the desirability of such a development. As long ago as 1924 The Motor Cycle published a photograph and a short description of a Raleigh machine which had been converted to two-wheel drive by a Yorkshire engineer for experimental purposes. The results were most interesting, for it was stated that the machine would climb anything, and would continue to travel over any surface which was firm enough to support it. Further, on straight roads the stability of the machine was such that it was positively difficult to fall off, even under provocation. Some force, however, was required to turn the machine on a corner, as it had a tendency to keep straight ahead. It is quite possible that this tendency could be eliminated, or at least minimised to such an extent that it becomes innocuous. But even so the question remains, is the additional complication worth while? The average motor cyclist would answer ‘No” quite definitely. The competition rider might think rather longer before answering, and if his final answer was ‘Yes’, there would arise very knotty problem for trials organisers. There can be little doubt that the addition of a front-wheel drive would revolutionise competition work! The idea, however, might be of considerable advantage for military purposes, since the scope of the motor cycle despatch rider would be far wider owing to his ability to progress over surfaces which are now regarded as impossible. The Raleigh machine mentioned had an extra sprocket behind the clutch from which a chain ran to a sprocket under the tank. A second chain led forward to a sprocket on a universally-jointed shaft below the steering head, and a third chain ran from this shaft to the front wheel. Re-member that this was a conversion applied to an existing machine, and might easily be carried out more neatly and simply on an original design. Now comes Mr JE Stormark, of AB Bofors, Bofors, Sweden, with a similar idea. He suggests either chain or shaft drive, the universally-jointed shaft being positioned under the’ steering head by suitable radius rods, which differ slightly according to whether parallel link forks or sliding fork members are employed. Mr Stormark has the courage of his opinions, and has converted several machines to his ideas, one of which, a racing sidecar outfit, won the Swedish hill-climbing championship in 1935. He states that machines fitted with his device will continue to travel on snow and ice when others are helpless. His original machine was most ingenious and embodied a universal joint in the front hub and certain features reminiscent of the Ner-a-Car and 0E . Mr. Stormark specifies as his ideal a narrow-angle V4 with geared cranks parallel to the frame line. The four-speed gear box would be driven directly from the engine, and the final drive to each wheel by shaft. There would be a differential between the two drives, capable of being locked in the event of wheelspin. The rear wheel would be spring suspended, and the front wheel final-drive shaft concealed in pressed-steel forks. Although the underlying idea should have many advantages for difficult going, the machine might be expensive, and possibly noisy since it must include not less than four pairs of bevels and an additional pair of spur gears.”

“I NOTICED THAT ONE OR two of your correspondents have related their activities during last summer, so I felt that I should like to mention a run which I consider—well, enthusiastic. It took place last Easter (which was every bit as much ‘summer’ here as July). During March I had been doing my usual 100-150 miles every week-end (besides evening runs), and when the long Easter week-end came under consideration I thought I would like to do something different. After some thought I remembered I had some friends in Blandford, Dorset. 1 decided to pay them a visit. So the route was planned and ‘Bubbles’ (my 250cc Red Panther) prepared. I left Glasgow at 6am on Good Friday, and with fair weather arrived at the Shap at 11am where I endeavoured to appease the ‘aching void’ and had an hour’s rest. My next long stop was at Bath, when I had an hour’s doze. The last lap—and I reached Blandford (and bed) about 1.30am on Saturday. Approximately 420 miles in 19½ hours on a 250—not no bad! Saturday and Sunday I spent visiting old haunts in the neighbourhood. Now for the return journey. About 8pm on Sunday it began to snow! I had visions of leaving the bike and going home by train. But pride (false or otherwise) put that idea out of my head. So at midnight I left for home. The first 100 miles took me five hours. But by this time it was getting light and progress became better. I reached Lancaster at 3pm on Easter Monday (still snowing), after a thrilling time on the tramlines round Wigan. And so for another last lap. I arrived in Glasgow, which I saw faintly through sleet, at 9.30pm. Another 400-odd miles, this time in 21½ hours. Now I know why ‘Torrens’ likes spring frames!

Matthew L Dickie, Glasgow, W2.”

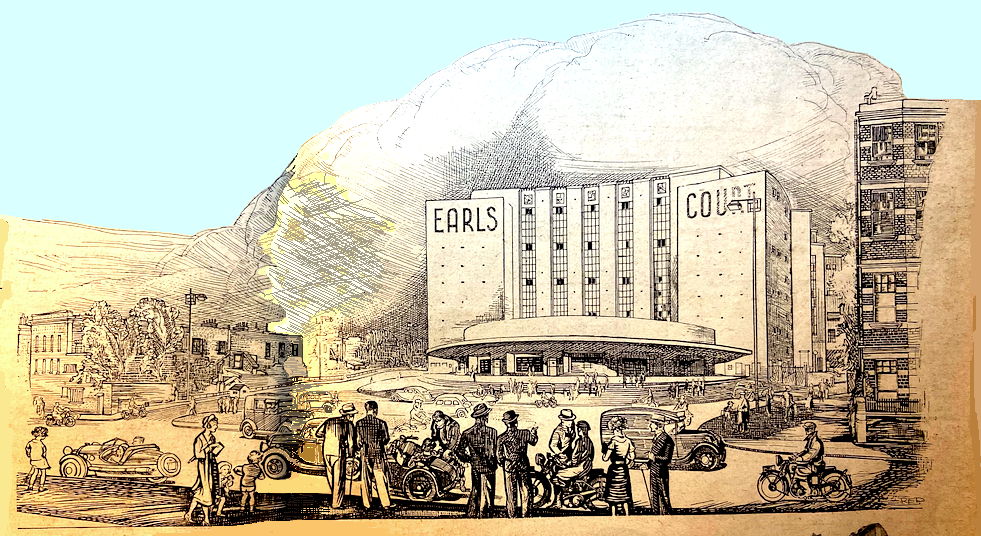

“AFTER THE SUCCESSES of spring-frame machines in the last TT, it was assumed that a number of new motor cycles would appear at the Olympia Show with rear-wheel springing either standard or an optional extra. It was not a case of the wish being father to the thought, because hardly had TT week ended than designers were at work laying out spring frames suitable for production purposes. That the Show revealed nothing new is a matter of history, and the fear now is that the whole idea of rear-wheel springing may be shelved for years. There is a very real danger of this: we know of spring frames which were designed months and months ago, and are still in the paper stage, not even a single experimental model having been produced. Manufacturers, in our view, are unwise not to press ahead. It is easy to say that rear-wheel springing is not necessary in view of the smoothness of modern British roads. Admittedly, too, it is difficult to produce a spring-frame that is neat, cheap and efficient. Our experience of British and Continental spring frames is probably unique. We know that rear-wheel springing must come, and that the industry, by its adoption, can add to both safety and the usable performance of their productions. Spring frames should be standardised on all except low-speed machines and those whose sales appeal rests largely upon their low price.”

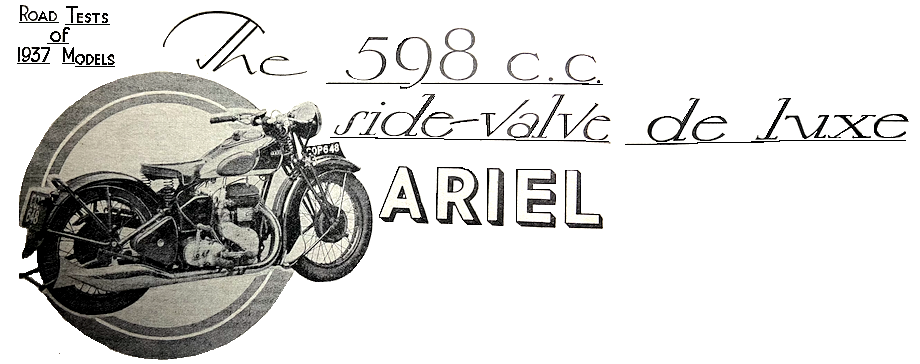

THAT YOU CAN’T FRIGHTEN motor cyclists with a mere war is proved by the fact that recently Ariels received a perfectly normal enquiry for a catalogue, prices, and so on from a private resident in Madrid, who is making a choice of machine. Can it be that the terrors of Franco’s bombs are overstated, and that everyday life in Madrid is nearer to normal than some would have us believe?”

“IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS last week Sir Arthur Michael Samuel asked the Home Secretary whether, in response to complaints by a public authority, he was taking steps, with the help of the local police, to abate the nuisance arising from the stream of motor cyclists at motor cycle trials on some of the public roads and lanes in Surrey. Sir John Simon said that he had been in communication with the Chief Constable of Surrey, who informed him that the police paid close attention to these trials, and took appropriate action to deal with any infringements of the law. Sir AM Samuel asked if the Home Secretary was aware that at the present moment in the lanes of Surrey these motor cycle trials were actually imperilling the lives of pedestrians. The Home Secretary said he was sure that the police would have the consideration in mind, but if the matter was one of regulation of traffic he thought it must be under the Road Traffic Act or under the local by-laws, and not under the Act dealing with general offences. Sir AM Samuel then asked if the Home Secretary would get in touch with the proper authorities. Sir John Simon replied that the fact the hon gentleman had asked this question would call attention to it. He had no doubt that the matter was being considered.”

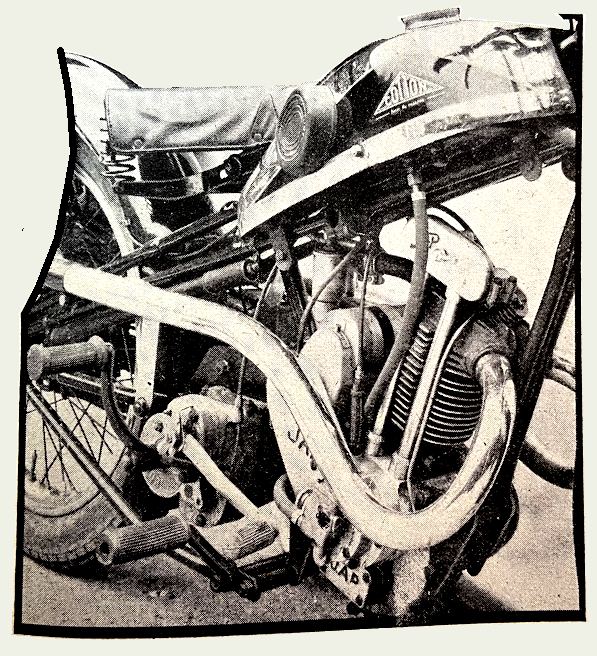

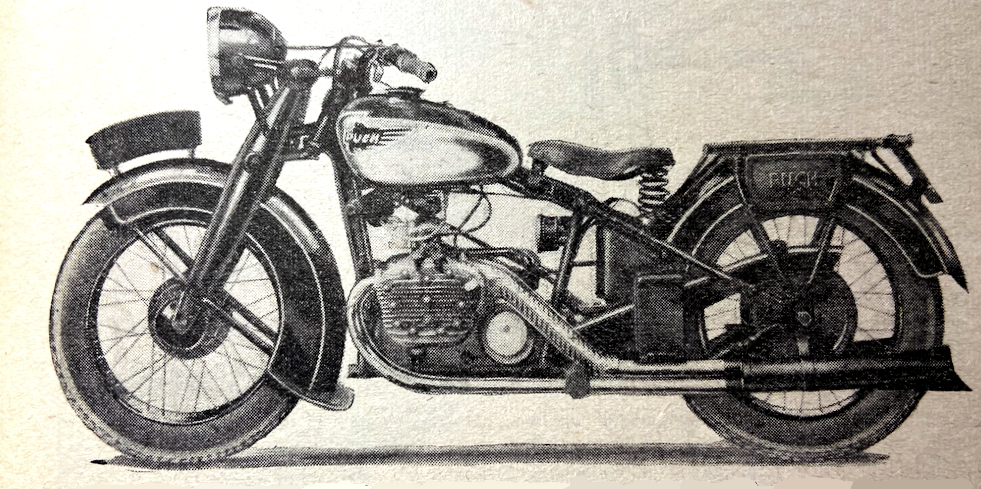

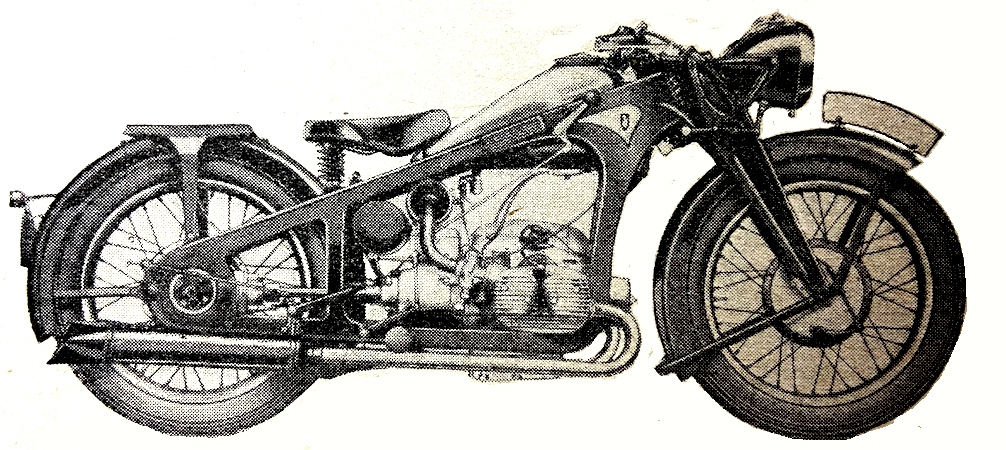

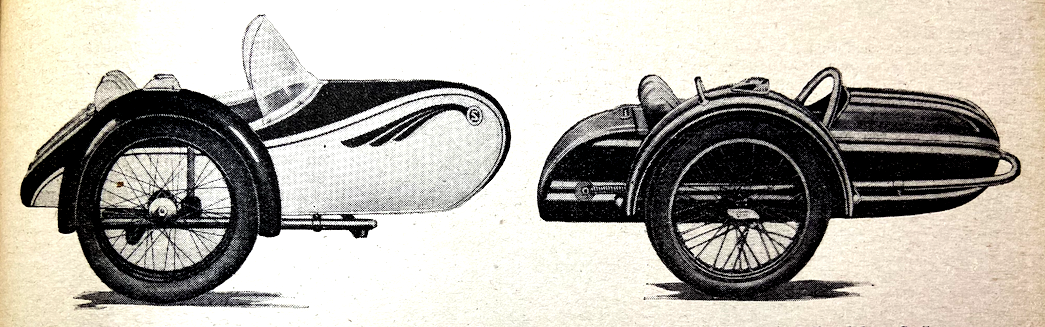

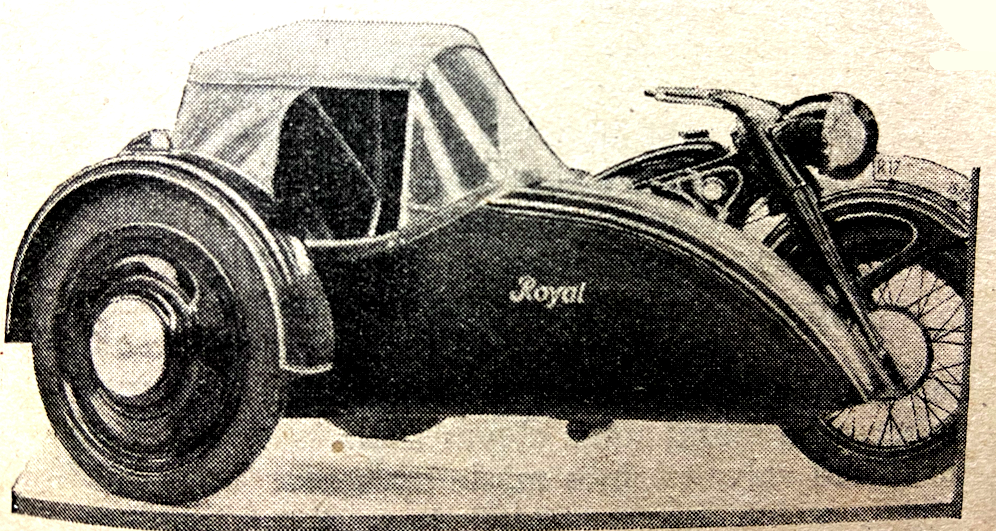

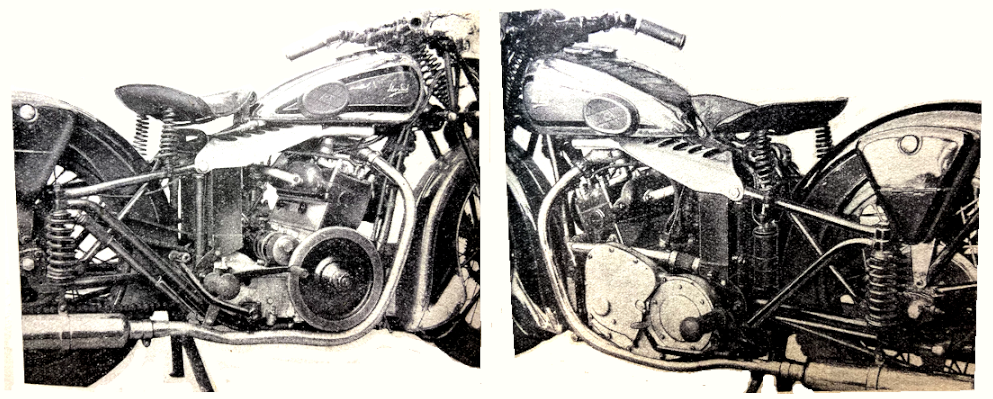

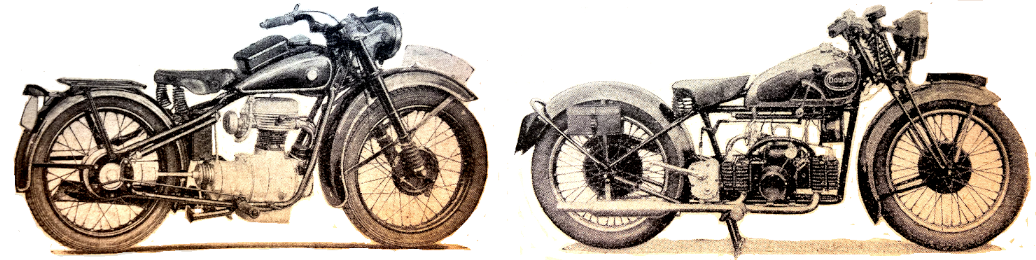

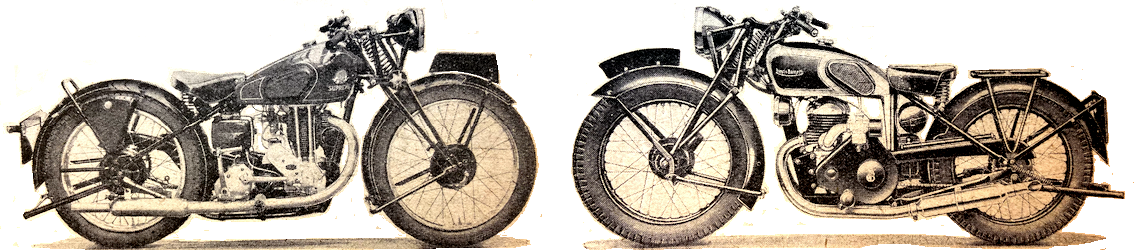

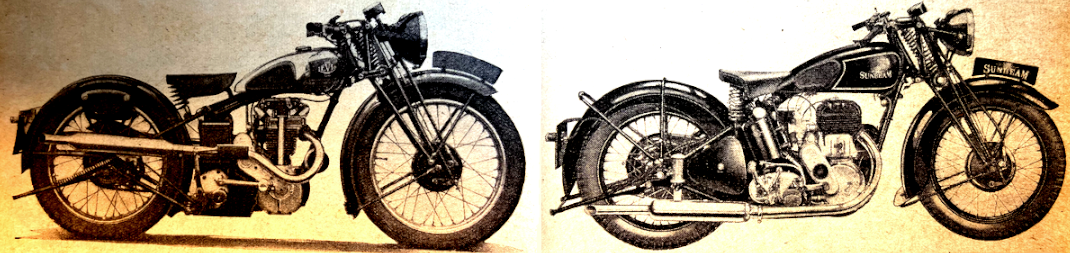

“WHILE NO STRIKING DEPARTURES from orthodox design were to be seen at the Brussels Show, there were several interesting Belgian machines on view. In addition, a number of motor cycles well known to British riders, including BSA, Norton, Triumph and Harley-Davidson, were exhibited. FN, probably the most important of the Belgian motor cycle manufacturers, showed a wide range of machines, all of them employing unit construction. Interest focused around the 1,000cc side-valve transverse flat-twin touring machine, which has the final drive by shaft. In engine layout the machine is reminiscent of the German BMW and Zundapp transverse twins. The machine has a four-speed and reverse gear box, with hand change. Another new FN series model, the Super-touring Type II, which is available with a 500cc or 600cc side-valve engine, is remarkable for the lavish use of aluminium in its construction. The cylinder itself is of aluminium, with a screwed-in steel liner and a hard bronze plate in the head to provide valve seatings. Detachable cover plates allow the crank chamber or gears to be readily inspected. In addition to a comprehensive range of utility models, Sarolea were showing new 350cc, 500cc and 600cc sporting models. Four speeds are standardised, but the separate engine and gear box construction is retained. On the Ready stand was a range of utility models. One of the two-stroke models has the hand-change lever so arranged as automatically to operate the decompressor when changing gear. Many of the Belgian motor cycles exhibited employed British proprietary engines and gear boxes—JAP, Blackburne, Villiers, and AJS engines were seen, together with Burman and Albion gear boxes. Other British fittings, including Lucas lighting, were also fitted to some models.”

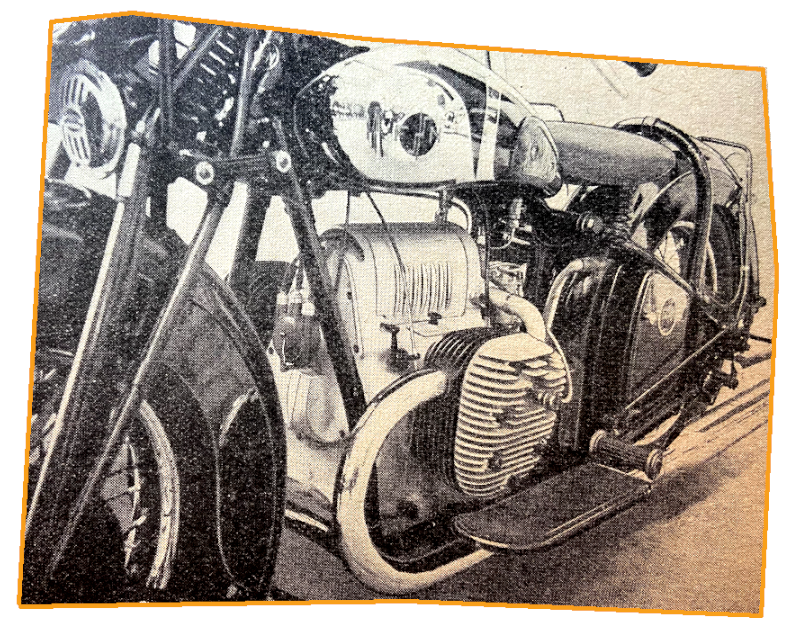

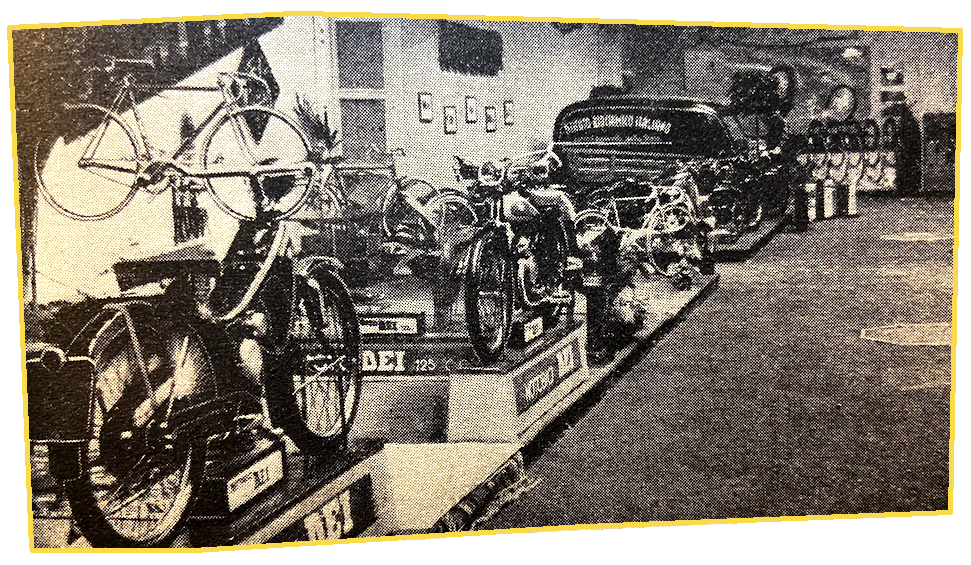

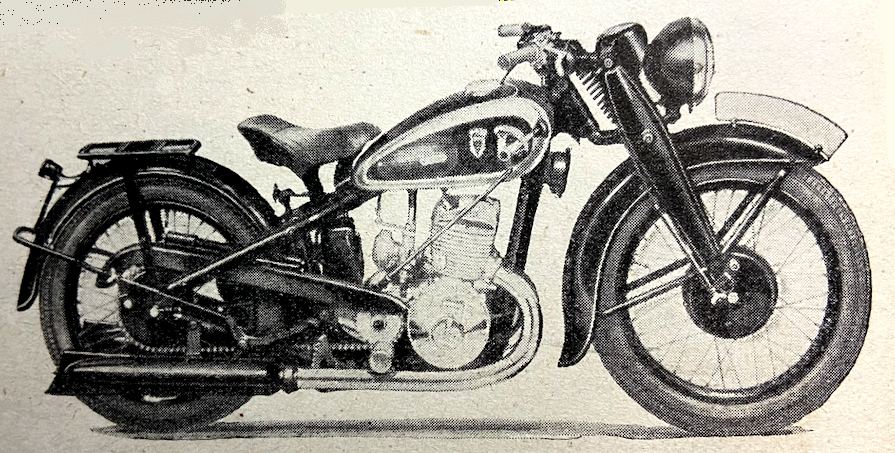

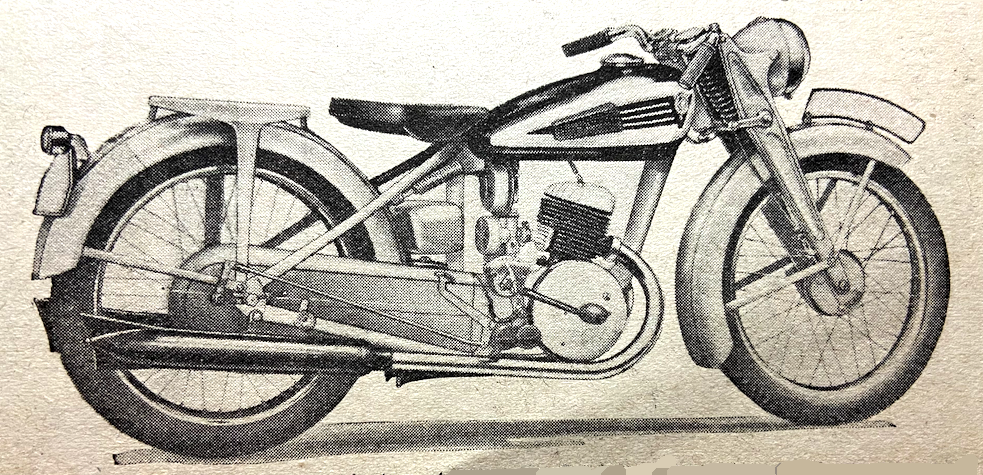

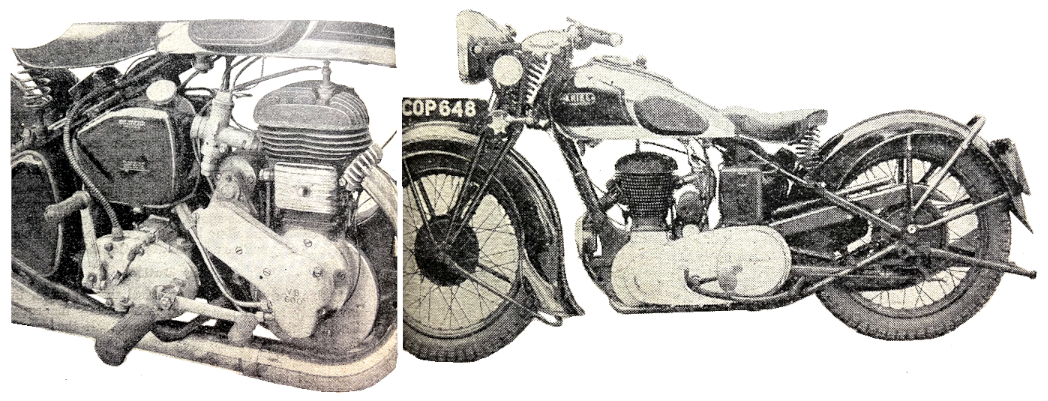

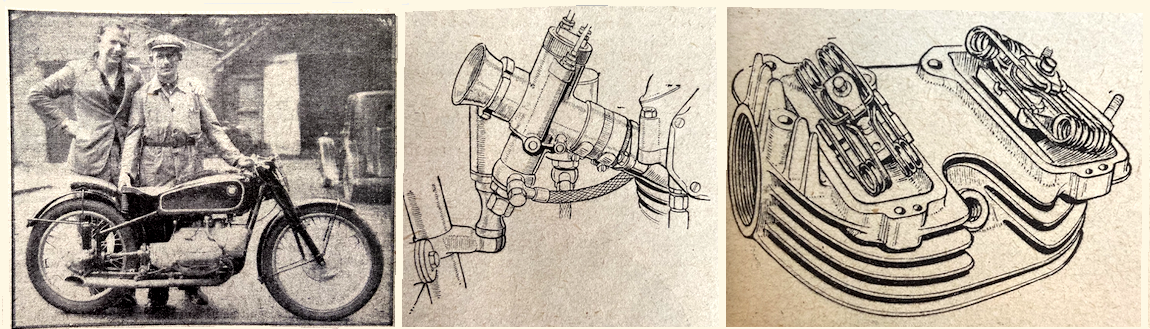

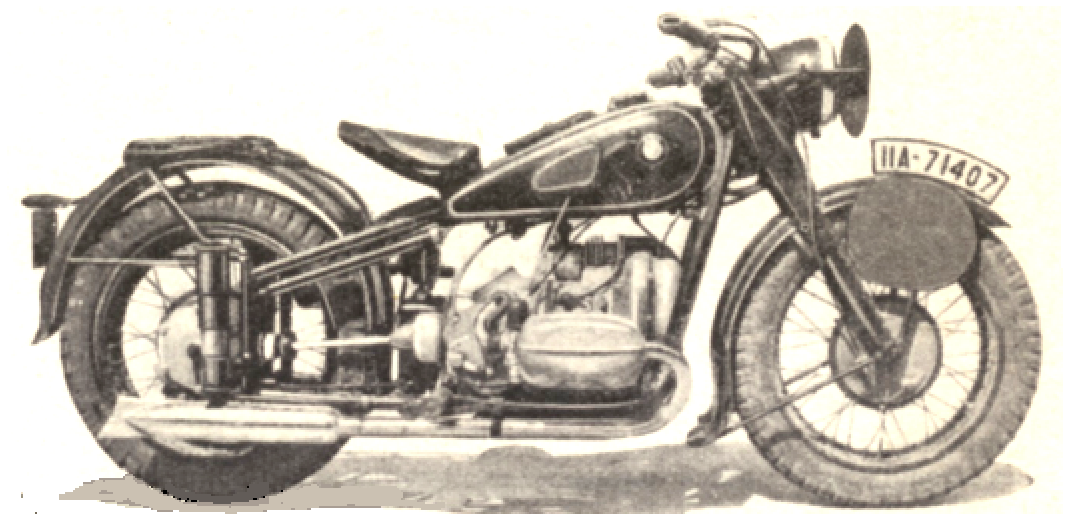

“ALTHOUGH THERE WERE 140 exhibitors at the recent Milan Show, mostly Italian, it was a British machine—the 1,000cc Ariel Square Four—that provided the pièce de resistance. On the same stand was shown a single-cylinder Astra (a replica of the Ariel), while several of the Italian machines on view were fitted with British proprietary engines, gearboxes and accessories—JAP, Villiers, Amal and Burman being the firms mainly concerned. The Italian-made Matchless engine (known in Italy as the Mercury) was also shown in various types and sizes. Germany was represented by the BMW and DKW. On the former’s stand were single- and twin-cylinder models from 200cc to 600cc, including the latest Model R6. This a super-sports machine with a 600cc horizontally-opposed ohv engine mounted in a tubular frame. It has four speeds, and employs the well-known BMW telescopic front forks. In comparison the DKW exhibit was small, consisting only of 100cc and 300cc two-stroke machines, and a 300cc engine for delivery van work. The only other ‘foreign’ country represented was Belgium, with examples of the Gillet and FN. Among the Italian machines considerable interest centred around the Dei, which was shown fitted with 250cc and 500cc ohv JAP engines, and with 125cc and 250cc Villiers two-stroke engines. A good example of an Italian sports machine is the CM, which has a 490cc ohv engine with hairpin valve springs and a four-speed gear box. This model has the engine inclined in the frame, but the 244cc and 340cc ohv models and the 498cc side-valve have vertical engines. Spring frames are increasing in popularity in Italy, and an interesting design was to be seen on the Simplex stand. Two springs are employed, and these are housed in telescopic tubes, while their action can be controlled by the rider. Another make which has acquired a spring frame is the Bianchi. Guzzis, surprisingly, show no change for 1937. The Ganna range consists of side-valve, and touring and racing overhead-valve, models. Previously either JAP or Blackburne engines have been employed, but this year they were shown fitted with the maker’s own engines. Among the other well-known makes at the show were Gilera, Benelli and MAS, but these have been modified only in minor details.”

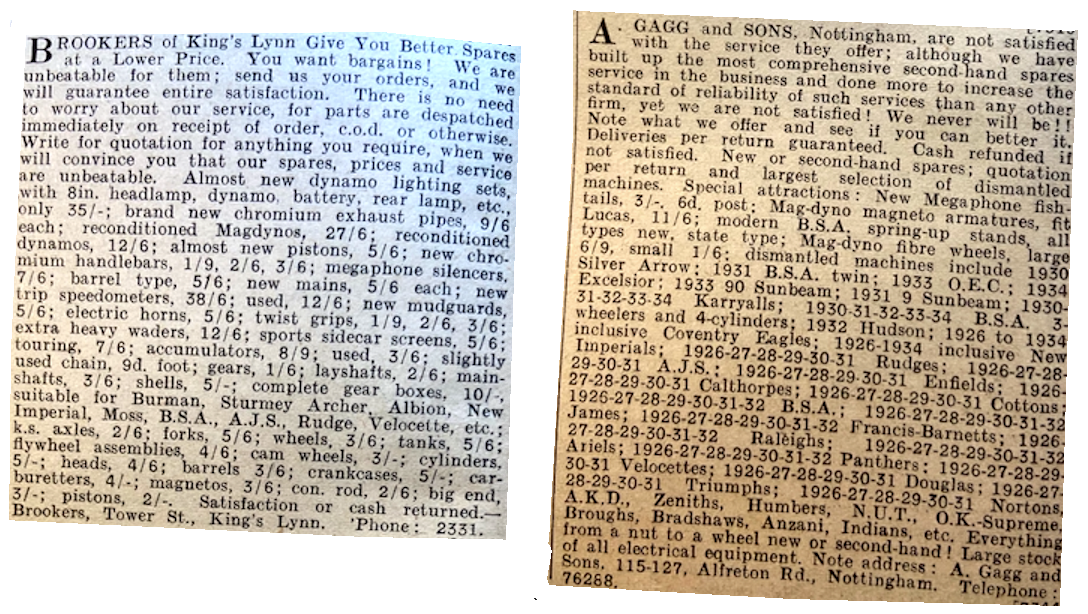

“CARBURETA, my eldest daughter, unpardonably owns a 15th-hand baby car, cost price £8. On January 1st it became legally undrivable, as it had not got a safety-glass windscreen. She made love to our local chief cop, and suggested that if she gummed cellophane over it, it would satisfy the law, but he was adamant. As a new safety-glass screen would cost about a third of what the antique car is worth, she took me forth into the wilds in search of a second-hand safety screen, and introduced me to a new world. This indefatigable damsel had unearthed the addresses of sundry car breakers in the wilds of the Home Counties, where rents are nominal. They buy up any old car, and either sell it as it stands as a going proposition, or if it be past praying for, strip it down, and sell the bits as replacements. Eventually, we floundered through deep mire to a derelict farm, where some 400 decrepit cars stood parked in the mud, and several very dirty youths were busy seckaydeeing them (‘CKD’ equals ‘completely knocked down’). Piles of aged dynamos, head lamps, back axles, chassis springs, gear boxes, magnetos and every conceivable part, all neatly sorted, lay in the mud under tarpaulins. And there Carbureta picked up a piece of Triplex just nicely too large for her windscreen frame. It cost her 7s 6d, but what it will cost her by the time she has had it cut to fit I cannot guess. This expedition has met one of my unanswered questions; I knew what happened to motor bikes when they get past use, but not their bulkier brethren, motor cars. I must have owned some 200 motor cycles in my time, and I haven’t been able to trace the ultimate fate of any of ’em, but I can make the shrewd guess that a considerable number reached the various firms who advertise second-hand motor cycle parts.”—Ixion

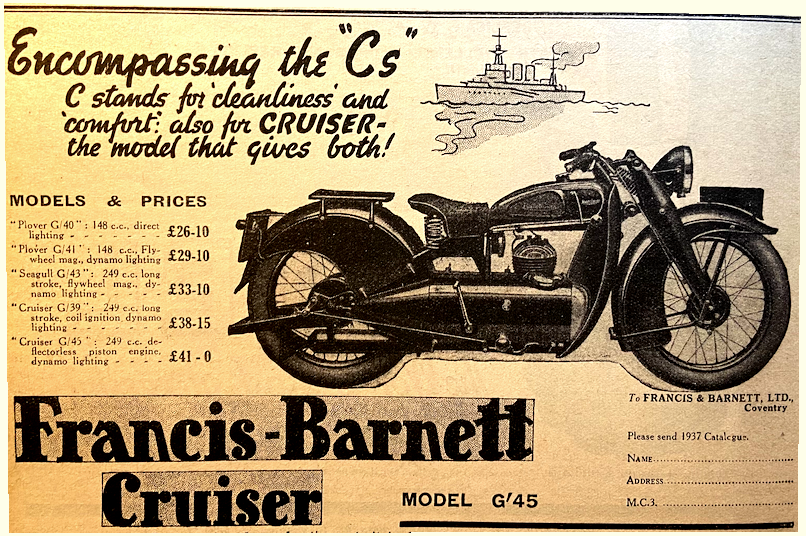

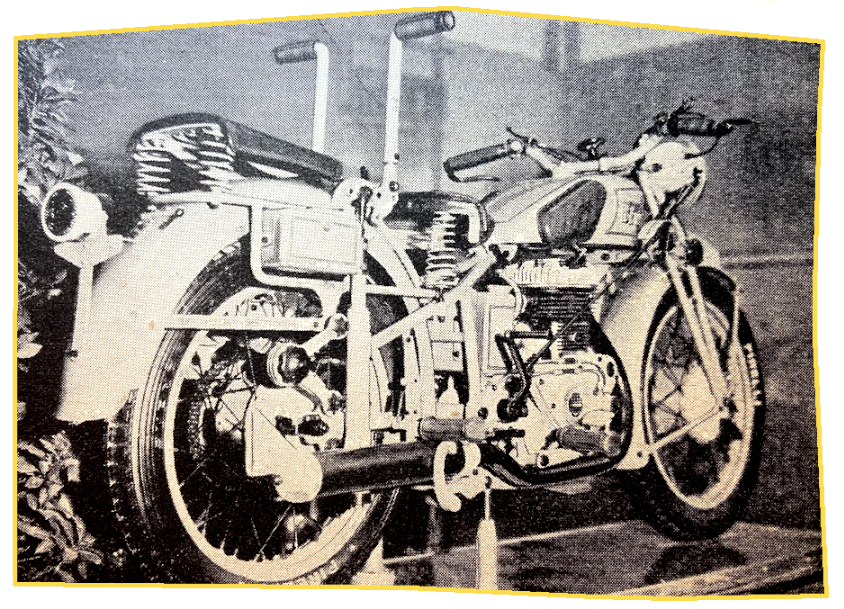

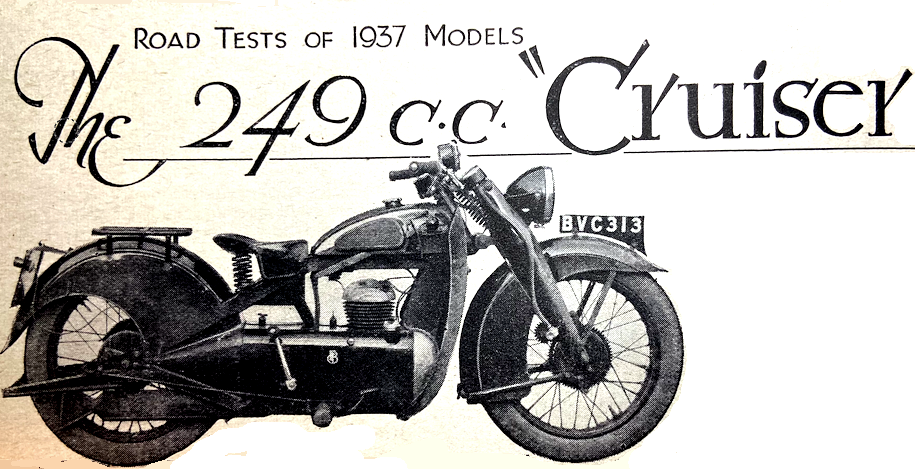

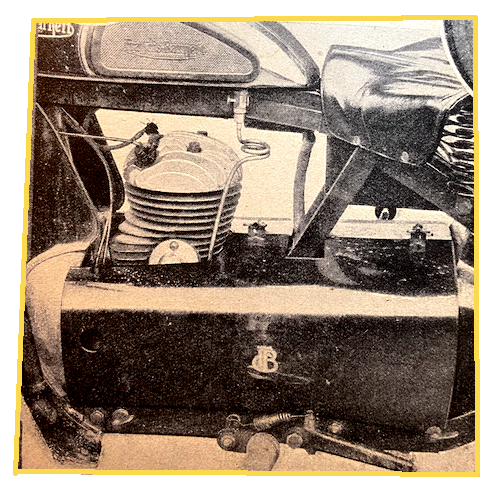

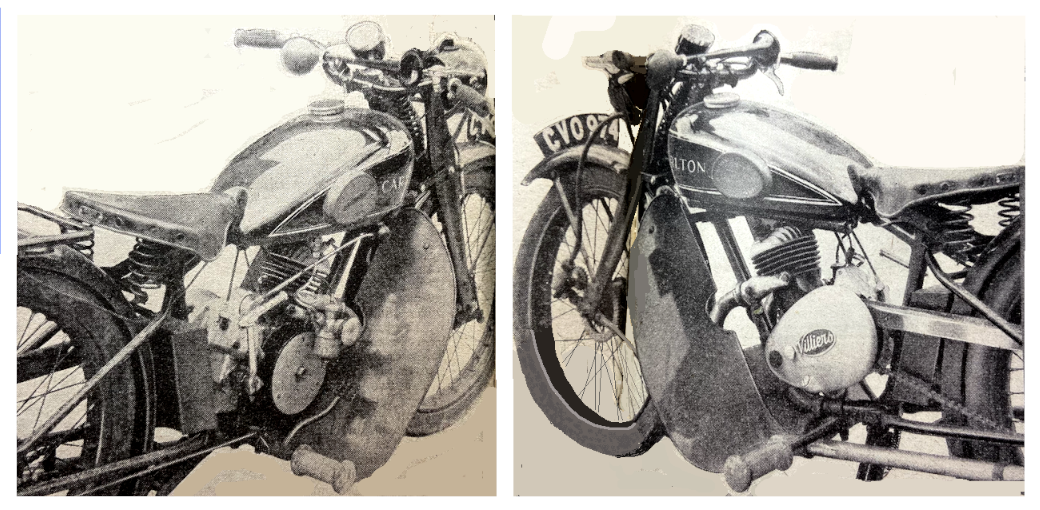

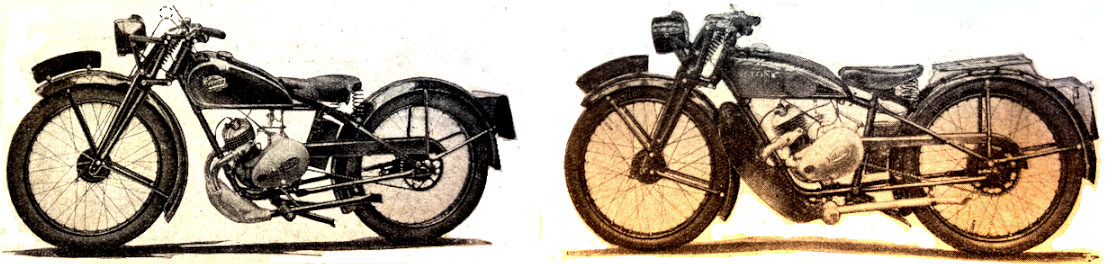

“‘GENTLEMANLY’ IS PROBABLY THE only adjective that faithfully describes the appearance and the performance of the 249cc G/39 Cruiser Francis-Barnett. It looks a gentleman’s motor cycle. There is no flamboyant exhaust system, and not only is everything neatly tucked away, but there is total enclosure and weather protection to a degree that is exceptional. How efficient the shields are can be gathered from the photographs, which were taken immediately after the machine had been used for some of the muddiest going imaginable. To state that no mud can reach the rider’s legs would be an exaggeration, because vehicles which overtake or are overtaken are apt to throw mud splashes sideways, even as they often spray those walking along the pavement. Experience proves, however, that the Cruiser really is a machine that can safely be ridden in ordinary clothing; it also brings to light these twin facts: first, that the shields do not drum, and, secondly, that removal of the panels enclosing the engine and gear box is a task occupying little more than seconds. Kick-starting the Villiers engine, which in the case of the G/39 model is of the deflector-piston type, required so little effort that it can truly be said, ‘A child can do it.’ With the mixture control, which is mounted on the right handlebar, set to ‘Rich’ the engine almost invariably fired at the third gentle dig at the kick-starter pedal. Incidentally, coil ignition was fitted to the model tested. This form of ignition is standard on, the G/39. The engine showed no tendency to stop once it had started, and there was no spitting back. Good slow running was a notable feature of the machine tested. In traffic blocks the engine idled quietly and effortlessly, and there was never any need for the rider to keep blipping the throttle. With the machine under way there was extremely little four-stroking, even when running light, and because of the exceptionally efficient silencing the little four-stroking that occurred was in no sense of the word objectionable. Outstandingly good road manners are a feature of the machine as a whole. The clutch of the Albion gear box proved light to operate and absolutely smooth in action. In addition, the gear box was completely silent on all ratios. Gear changing is by hand, and proved simple and straightforward. No special care was needed to effect perfect changes either from a high gear to a lower one or vice versa. More often than not it was desirable to move the machine forward an inch or two in order to engage bottom gear from neutral so that the dog clutches might be in the correct relative positions for engagement—either this or the clutch could be let in again and the operation repeated.

Assuming an ordinary amount of attention to the setting of the mixture control the machine performed effortlessly under all conditions. Flexibility is such that the machine, if desired, can be treated as entirely a top-gear mount. The engine would pull sweetly away even from speeds as low as 10 or 12mph in top gear and accelerate up to just over 50mph. While the engine would slog with almost cart-horse persistency up main road hills, it also would hum along the open road. Often speeds of 45 and 48mph were kept up for mile after mile. The machine is a gentlemanly mount, but there is nothing of the slowcoach about it. In second-gear the engine takes the machine quickly up to a useful 40mph; by using his gears the rider has an interesting sports-like performance. Both brakes are excellent—powerful, yet absolutely smooth and safe in action. The figure of 39ft from 30mph shows the ‘iron’ that lies beneath the velvety smoothness. The only possible criticism of the brakes is that the front brake lever involves rather too a stretch to grasp it. The riding position is of the sit-up, touring type, and is uncramped even for a rider of 5ft 11in. Except for the control just mentioned all controls are well placed. A good point in this connection is that an adjuster is provided for the rear brake pedal so that it may be set to suit an individual rider. An unusually large (18in wide) ‘stubby’ Terry saddle is fitted, while the tyres standardised are of 3.25in section, and therefore need not be pumped up very hard. The engine is smooth throughout its range. An expert might point to a period at a speed of roughly 40mph in top gear, but this is so minute that really it cannot be termed a period. It is unlikely that any but men out to find ‘points’ would detect it; there are no ‘pins-and-needles’ anywhere in the speed range. By modern standards the steering is unusually light even for a machine of 249cc. The machine can be ridden feet-up at exceptionally low speeds—it can be ridden almost to a complete standstill. This is an excellent feature so far as traffic riding is concerned. Greater confidence would, however, probably be evoked under gusty, wet conditions if the steering were somewhat heavier. On one occasion, when a 500cc machine of more normal design was being followed, it was noticed that the Francis-Barnett, in spite of the large area the front wheel assembly presents to a side wind, swerved less under the influence of the strong gusts than the machine that was just in front. Nevertheless, the machine could, it is suggested, afford a greater feeling of security under these conditions. Under all normal conditions the steering is of the ‘guaranteed to an inch variety’, and the cornering excellent. In spite of many miles of city streets traversed under slippery conditions, never once did the machine skid. The Miller head lamp provided a long, narrow beam with a fair degree of side illumination. To sum up: here is a machine that proved so good that it is next to impossible even for a motor cyclist who rides dozens of different motor cycles a year to offer criticism or make suggestions.”

“A UTILITY MOTOR CYCLE capable of covering 10,000 miles without calling for a single adjustment is the dream of one of our best known designers, He maintains that this is a feasible proposition to-day. The machine would. be a four-stroke, but on lines radically different from those of the modern motor cycle. He avers that although ‘different’, the machine could easily be made pleasing to the eye. What checks him is the cost of getting into production and the question whether the demand for such a machine would be adequate. He cannot afford to ‘back a loser’, and the cost of tooling up in readiness for production would run into thousands of pounds. It is easy to sympathise with all who are faced with decisions affecting the livelihood of workpeople and the pockets of numerous others. Nevertheless, we consider that the sands are running out; that unless manufacturers make a bid for the utility market soon the motor cycle will be looked upon only as a vehicle of sport. As yet the industry has merely touched the fringe; the number of motor cyclists should be double what it is to-day—it could be if suitable designs were available.”

“THE OTHER DAY I gained an insight into the way the United States of America exploit the gruesome in order to prevent road accidents. The means in this instance was an article. It did not just describe accidents, but gave pen pictures of the victims, their injuries, and their actions in the moments immediately following the collisions. ‘Gruesome’ is certainly one word, and ‘nauseating’ is another. Much as I dislike the method, I can well believe that in small doses it is effective. All the same, I should hate to see it employed over here.”

“THE MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT’S recently published registration figures covering the ‘peak’ months of July-September 1936 show that of a total of 505,779 motor cycles in use, no fewer than 125,499, or nearly one in four, were sidecar machines. Surely an adequate answer to those who aver that the day of the sidecar is over. The figures also reveal the popularity of the under-250cc machine—an increase of 5,247 over the corresponding period of 1935. And it will probably interest many to know that of the 505,779 motor cycles in use a England, Wales and Scotland, the share of London and its neighbouring counties was 117,559—an interesting fact since it reveals that in spite of the area being so densely populated the motor cycle retains its popularity.”

“RECENTLY I spent an evening with a man who has designed a number of well-known models. Our conversation turned to a matter I have never seen discussed in print: the way a model if left unaltered for a long period generally grows steadily worse—apparently, the machines produced are exactly like those manufactured, say, a couple of years previously, yet their performance is nothing like so good. We discussed an actual model with which he had been associated. After a while not only did the speed of the latest productions not compare with that of the earlier ones, but their engines were decidedly coarser. Investigation showed that certain of the castings were being supplied by a different concern and the patterns were no longer in accordance with the original design; consequently, the cylinder head shape—to take an example—was not as it should have been. In addition, there was no longer the same care taken by the assemblers in building the engines; they had become so accustomed to the job that they did it automatically. Various jigs and tools were also not so good as they might have been. After a complete investigation and a general overhaul of the supplies and production methods the machines turned out were once again the equal of the first models. I know two makers who have recently carried out investigations on these lines—to the marked benefit of the purchaser.”

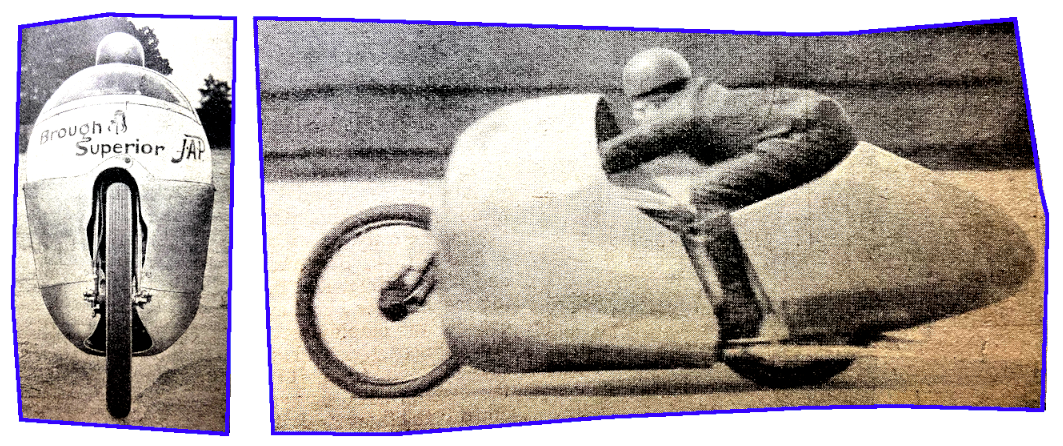

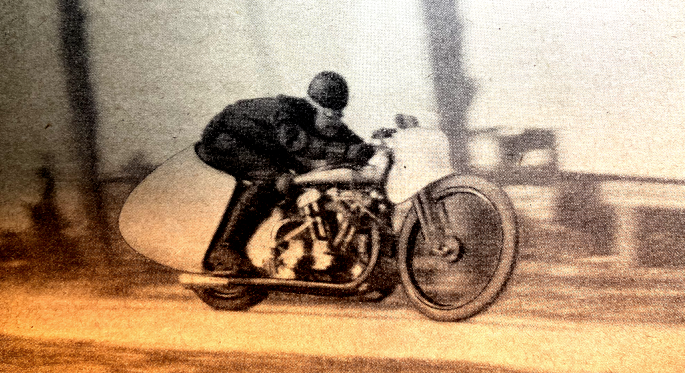

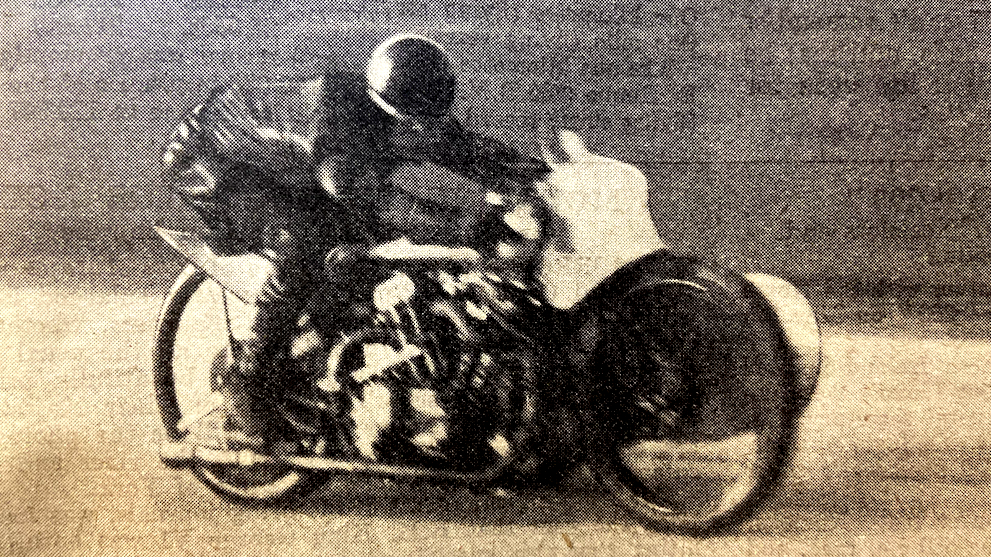

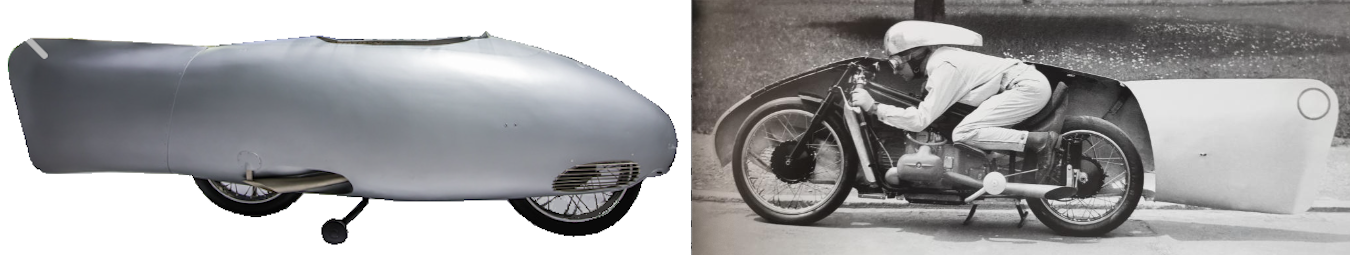

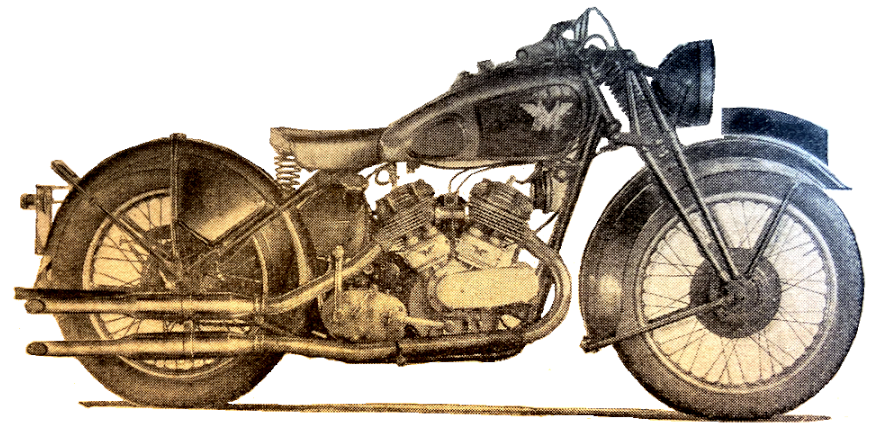

“‘RIDING A LARGE STREAMLINED motor cycle, Joe Petrali, the Milwaukee dare-devil, roared over the smooth beach at an average of 136.18mph; a new world’s record for two-wheeled bikes.’—American newspaper.”…”That well-known rider, Joe Petrali (Harley-Davidson), has been adjudged Champion of America for 1936.”

“THE LATEST OFFICIAL registration figures show that there are 2,768,606 mechanically propelled vehicles in use in Great Britain.”

“GEORGE PATCHETT, THE English designer of the Czechoslovakian Jawa machine, escaped with bruises in a serious motoring accident near Davos. His wife, who was with him, also escaped with bruises.”

“THE MAN WHO WAS responsible for Leeds being the first city to install traffic lights—Mr RL Matthews, Chief Constable—has resigned owing to illness.”

“‘NOT MORE THAN 50% of drivers take the trouble to give properly the signals which the law and prudence both require.’—Letter in a London newspaper.”

“ONLY A FRACTION of 1% of United States main roads begin to approach the fundamental requirement of ‘automatically correcting the driver’s mistakes’, says an American magazine.”

“‘THE COLD FACT is that traffic to-day is a combination of an 80mph car in the hands of a 20mph driver struggling to adjust itself to a 30mph road.’—Fortune, American magazine.”

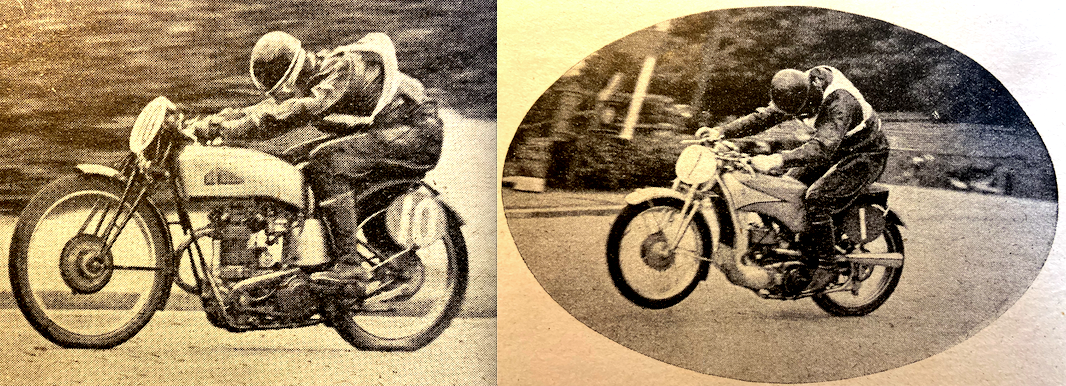

“MILHOUX AND CHARRIER (FN sc) were forced to abandon an attempt on the 12-hour sidecar record after 20 minutes’ lapping at Montlhéry, owing to a broken crank case.”

“A CHINESE PROFESSOR, visiting London, criticised the traffic lights as follows: ‘We have some street signalling lamps like yours, but they are giving way to the single searchlight, with an arrangement for changing colours.'”

“DER DEUTSCHE AUTOMOBIL-CLUB, the ‘RAC of Germany’, has established 60 stations where German pedal cyclists may have the rear mudguards of their machines painted with phosphorescent paint free of charge.”

“‘OFTEN I HAD NOTICED the large number of iron manholes and other plates on the road between Archway Tavern, Highgate, and Barnet. Recently, I decided to count them. There are 229, excluding drains.’ Correspondent in The Autocar.”

“ALLOW ME TO ENDORSE your editorial remarks on the subject of trials and riders generally. The riders of to-day may be able to ride ‘feet-up’ through the deepest of mud, but with few exceptions they make a fetish of this type of going and practise on:every available occasion. Thus, riding in these ‘snappy’ trials has become a circus balancing turn almost requiring a special machine. A large proportion of amateur trials riders and their mounts do not show up too well on the road parts of the course or in the muddy lanes connecting sections. All-round riding skill must suffer in consequence.

A Paul, London, N2.”

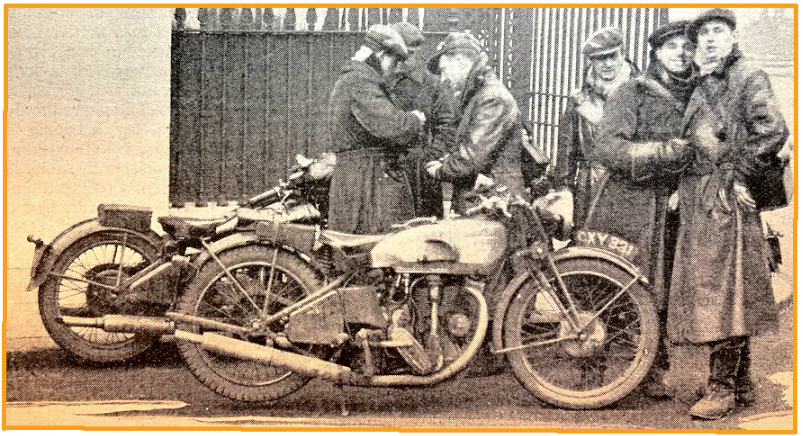

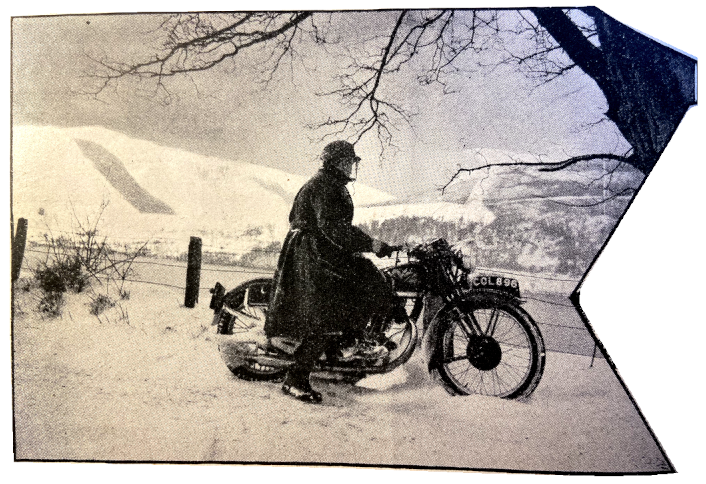

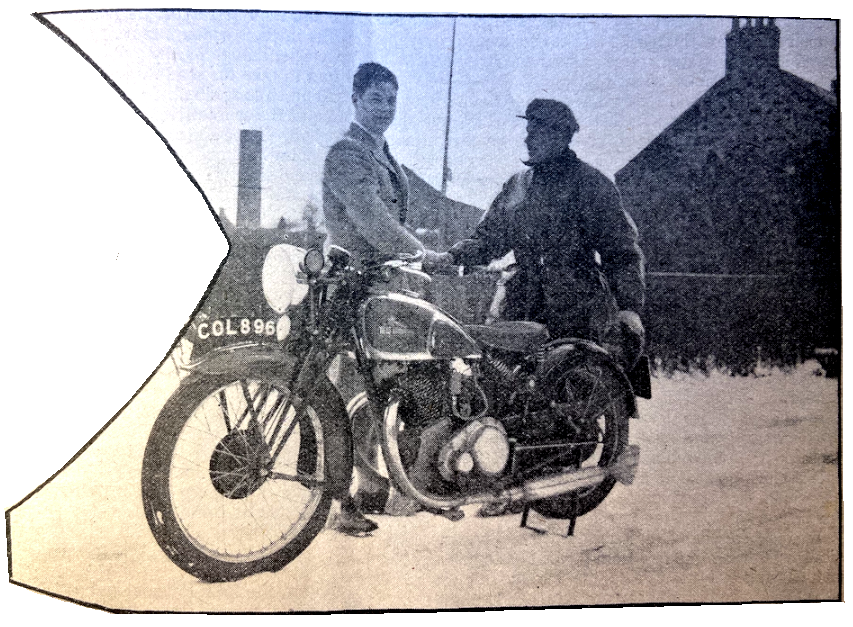

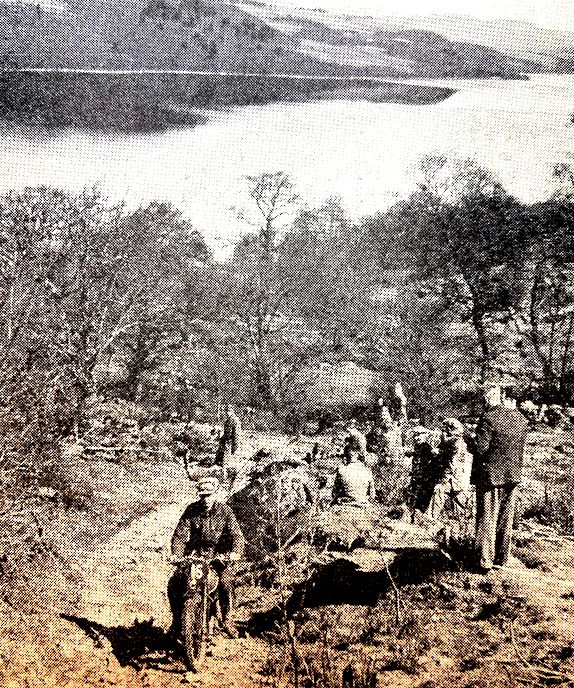

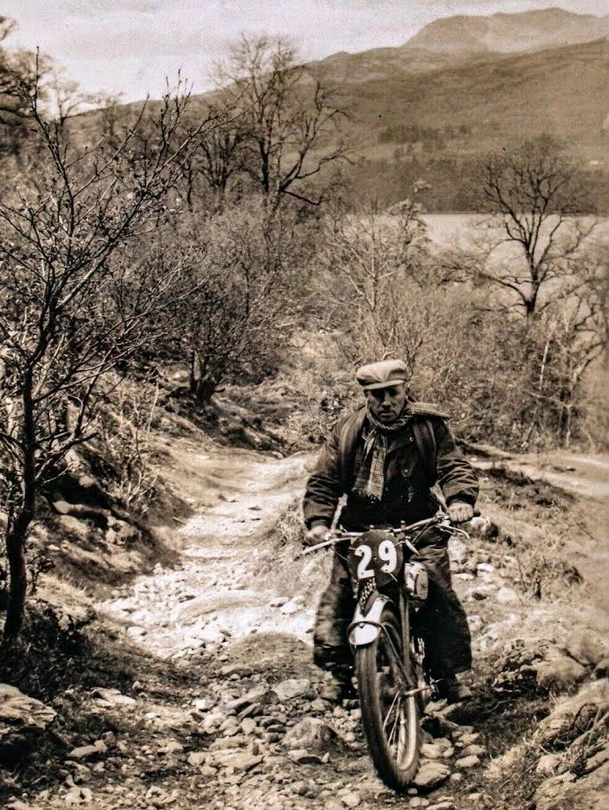

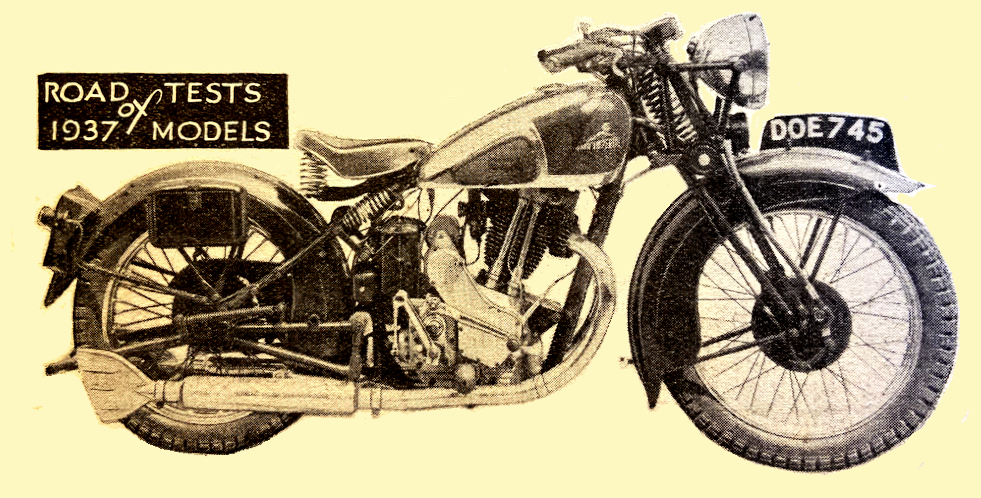

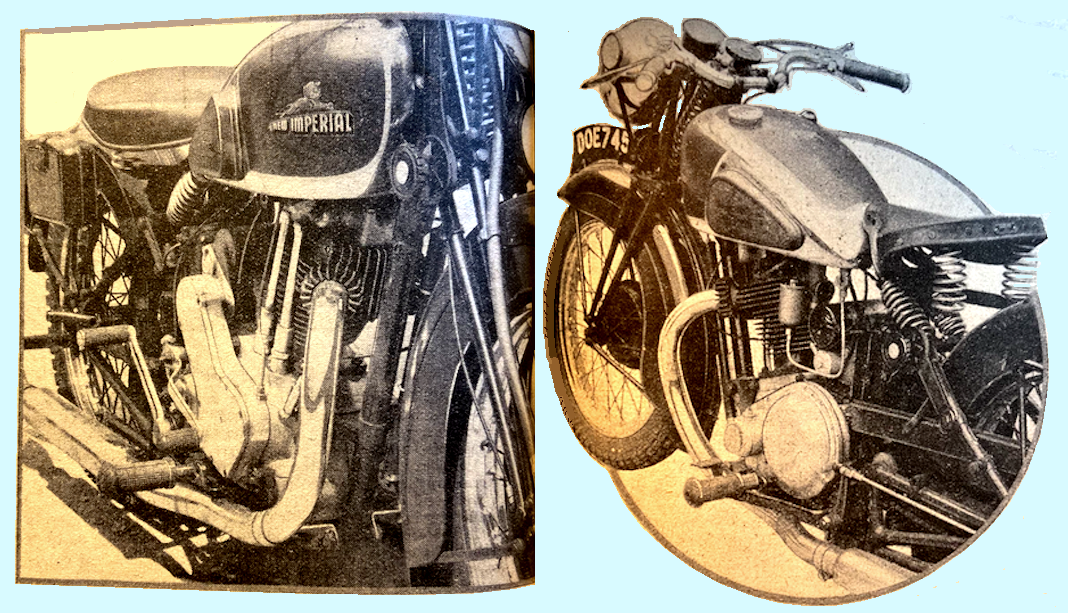

“LAST WINTER THERE APPEARED in the correspondence columns of The Motor Cycle a letter under the nom de plume. of ‘Manufacturer’. This letter inaugurated a competition, open to all motor cyclists, to find the design desired by the majority; and the winning entrant was to be awarded a machine built as near as possible to his design. Now, as many readers will recall, this competition was sponsored by the New Imperial company, and the lucky; winner proved to be an Edinburgh University student whose home is at Abernethy, a few miles outside. Perth. Of course, it took time to produce the actual machine evolved from the design submitted, but late last November ‘Torrens’ described his experiences with the model after riding it for a few days. Afterwards the machine went back to the works, previous to being handed over to Mr A McDougall, the fortunate winner. Last week it was my happy experience to represent The Motor Cycle and ride the machine up to Abernethy, there to hand it over to the winner on behalf of New Imperial’s. For weeks I had been looking forward to this run. Unhappily, when all was ready, I fell a victim to a puerile, but highly contagious, affliction. However, after three weeks’ quarantine, I was fit and ready for the trip. And so it was that soon after noon on the Wednesday the New Imperial and I were to be seen threading our way through. London’s traffic, and on to the Barnet By-pass, en route for the North. 1 had some slight misgivings on account of the weather forecast threatening snow and gales ahead. There was already a stiffish side wind, but the New Imperial bowled along the monotonous Great North Road at a steady 40mph. The machine had covered a number of miles since ‘Torrens’ had ridden it, and the engine was running with that sweetness and silkiness which denote careful running-in. However, because the model was still very new and also because it was not my own, I had not the least intention of flogging it. Nevertheless, the engine seemed to revel in almost any speed, so it was not long before the speedometer needle was pointing to 50. I did not attempt to exceed this speed, but was content to enjoy the comfort of the spring frame—I had the dampers, both fore and aft, slacked right off. Mile after mile was reeled off. At Grantham, after 110 miles, I stopped for a rather late lunch. It was then that I noticed a tell-tale stain of Ethyl on the primary gear case. But the leak thus indicated was caused by nothing more than a slackened

petrol pipe union nut. When 1 went to open the tool-box, I found the ‘cup-board was bare’. Not a single tool—and here was I on a 500-mile journey! I was not dismayed, I borrowed a few spanners at a garage and tightened up any nuts that might conceivably slack off. By the time I reached Doncaster it was getting near lighting-up time and also becoming very cold. We were in Yorkshire and the hotels by the wayside looked very tempting. But I had aimed at getting past Scotch Corner at least, so I kept in the saddle although my hands were getting more and more numb with the intense cold. Boroughbridge and Catterick slipped by—it is curious how short the miles seem in the dark—and eventually we turned left at Scotch Corner for the Carlisle road. It was here that I first encountered the snow. Although the road was free from it, the fields and trees lay hidden under a beautiful white mantle, all the more fairylike in the beam of the powerful head lamp. I decided to stop at Bowes for the night, for it was 7.30pm and I had no desire to continue by night over that wild moorland road that rises to over 1,400 feet before dropping into Brough. When I was awakened next morning I heard the wind howling through the eaves of the old hotel. On looking out I saw that the snow of the previous night had not melted. On the contrary, it was beginning to snow again. Outside it was really bitter, while the wind had risen almost to gale force, driving the snow fiercely before it. In these cheerful conditions I left Bowes for the long ascent up to New Spital, followed by the drop into Brough. Very soon I was riding over ice. In addition, there was a strong south-easterly wind blowing, and the combination of slippery ice and strung wind resulted in the rear wheel constantly sliding over to the crown of the road. Meanwhile, the snow came down so thickly that visibility was reduced to a bare ten yards in places. It was altogether eerie—but not exactly pleasant! Only two vehicles did I see, and one of them was in the ditch! At last we started the descent into Brough, where the carpet of snow on the road was beginning to melt. With the better conditions I was able to ride at a steady 40, and Appleby and Penrith were behind us in a short time. Just outside Penrith I came across a large six-wheeler and trailer lying on their sides in the hedge, a long way off the road. Quite how they got there I do not know, for I did not stop to enquire. All was plain-sailing through Carlisle and on the long, fast road to Lockerbie and Beattock. Ahead I could see the high peaks of the South of Scotland gleaming white in their winter’s coat of snow. It was a beautiful spectacle, though hardly a pleasant thought to know that I had to take the road through these mountains! Another long climb to Abington, where I found the force of the wind-driven snow most unpleasant—almost like hail. Time and again I saw roadside telegraph wires and poles which had been blown over in the gale. Carefully and slowly I rode the New Imperial along the slippery roads through Lanark and the many mining villages en route for Stirling. Conditions gradually became worse. It began to snow harder, while the roads were coated with ice. What was worse, it was now getting dark. How I loathed and hated that road from Callander to Lochearnhead. It winds and twists along the shores of Loch Lubnaig—and last Thursday, with such a high wind blowing…But if conditions were bad at this point, they were infinitely worse over the Glen Ogle Pass Irons Lochearnhead to Killin. Here a virtual blizzard raged, and in the rapidly falling light it was an enormous relief to drop down, or rather slither down, into Killin, where it was my fortune to find my good friend Bob MacGregor, the well-known Rudge rider, at home. A warming glass of whiskey—the real McKie—made me quite certain that at Killin I must stay. And at Killin I did stay!So far, the New Imperial had performed wonderfully. Nobly had it stood up to the slogging in high gear that I had been forced to use in the snow. But conditions on Friday’s run along Loch Tay, through Aberfeldy to Perth, were infinitely worse. It had snowed steadily all night, and the roads were inches deep. That was just the trouble—sometimes the snow was a mere two or three inches deep, and then there would be drifts a foot or more deep. Because of the difficulty of spotting these drifts, I was forced to proceed with great care. It often surprised me how the Universal rear tyre obtained a grip up some of the slopes which I was forced to climb slowly. Still, I enjoyed the run immensely. I followed the south road along the shores of Loch Tay, and was impressed by the extraordinary way in which the sun occasionally shone through the clouds ahead of me while it was still blowing almost a blizzard everywhere else. I passed on my right those ‘Scottish’ favourites, Cambussurich and Ardtalnaig, both snow-covered and almost unrecognisable. Near the end of Loch Tay I stopped for a cigarette and a photograph, and was joined by a passer-by, who was an enthusiastic photographer. He was justly proud of his pictures showing a frog waiting outside a beehive to make a meal of a bee or two. In spite of the snow-bound roads, the New Imperial steered perfectly, my only difficulty being to check the violent side gusts of wind, which must at times have reached at least 60mph. Normally, such side winds cause little worry, but on snow and occasional patches of ice it was a different story. However, we reached Aberfeldy and then Birnam without trouble. So far I had been on more or less virgin snow, but from Birnam onwards I joined the main road. Heavy lorries and buses had transformed the snow into a

highly polished form of ice, forcing me to use both hands on the bars—up till then I had been riding with my left hand hanging loosely behind in the slipstream, where it kept comparatively warm. I toured through the slushy streets of Perth, only to find the roads even more icy on the far side—Abernethy lies about eight miles south-east of Perth. To make matters more unpleasant, the gusting wind was blowing broadside across from the left, and several times I found the model sliding towards oncoming traffic. At last we reached our destination. No one Was there to greet us—probably because we were not expected on such a day! But when a knock on the door did call attention to our presence, we were given a right royal Scottish welcome. After an unofficial ‘presentation of awards’ we wheeled the faithful New Imperial to a shed, and soon I was sitting down to a Welcome repast of hot broth and other Scotch tasties. Mr McDougall, only recently out and about after over a year in hospital with an injury received while playing Rugger, was itching to go out in the cold to give his machine the once-over; he resisted the temptation until I had finished. But he was out in a trice as soon as I went upstairs to change, and for the remainder of the afternoon we spent most of the time admiring the machine. It was scarcely wise for him to attempt to ride it just yet, particularly in a snowstorm. In the meantime friends popped in to congratulate him, and it was a cheery party that sat down to a high tea. It was still snowing hard, but I had a glowing feeling of having set out to do something in the face of adverse conditions and having accomplished it. And I liked to think that the New Imperial, outside in the cold shed, was feeling very much the same. We had stuck together for over 500 arduous miles, and now I was to bid good-bye—both to the machine and to my new-found Scottish friends.—Ambleside”

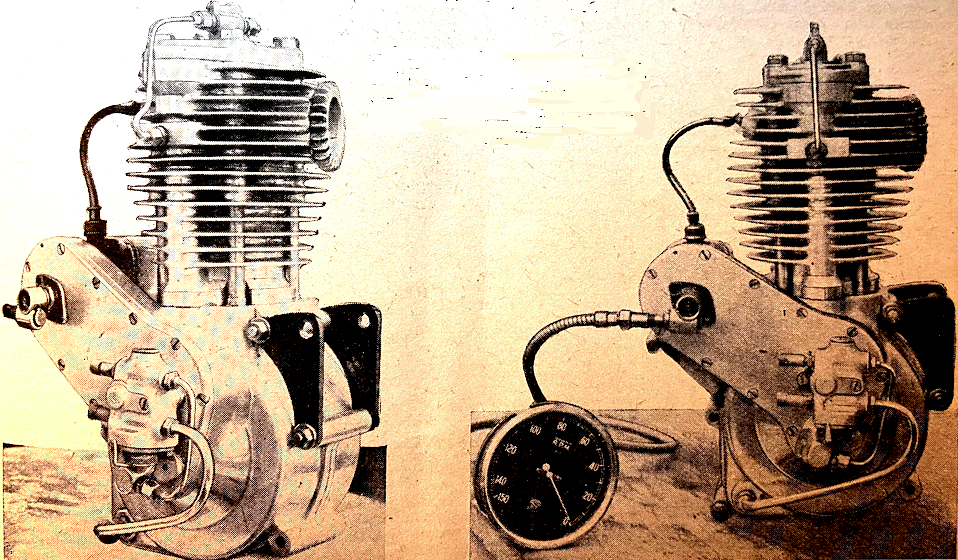

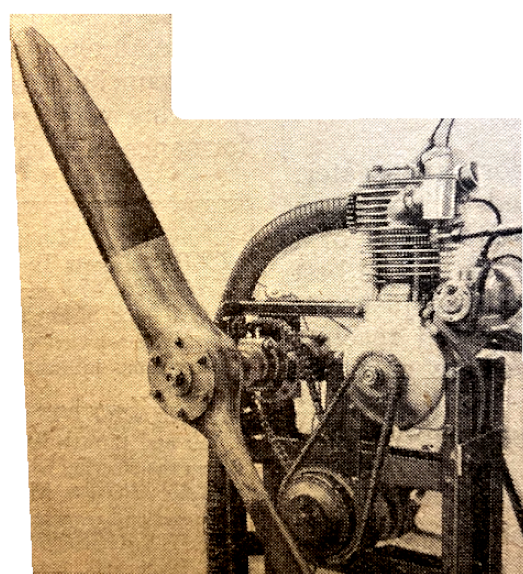

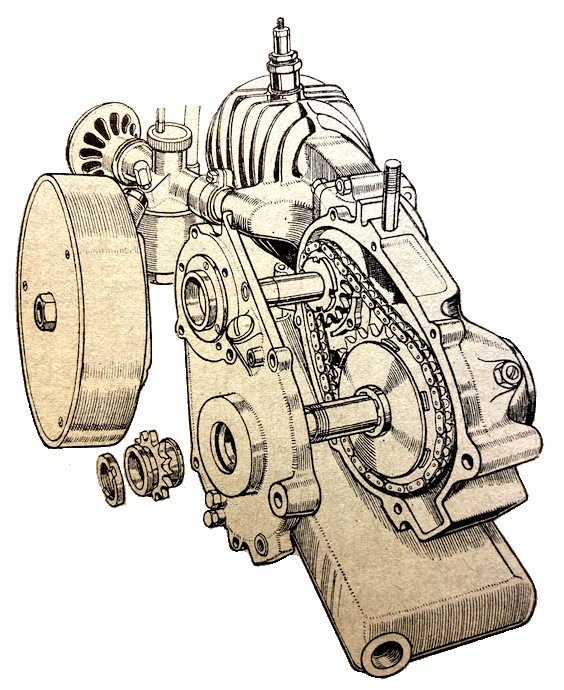

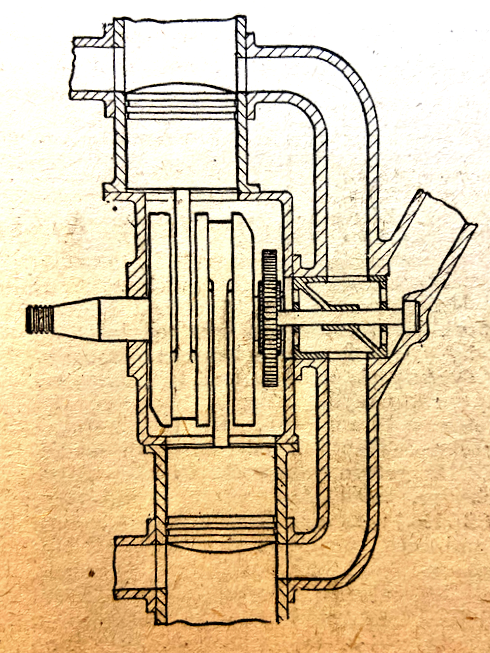

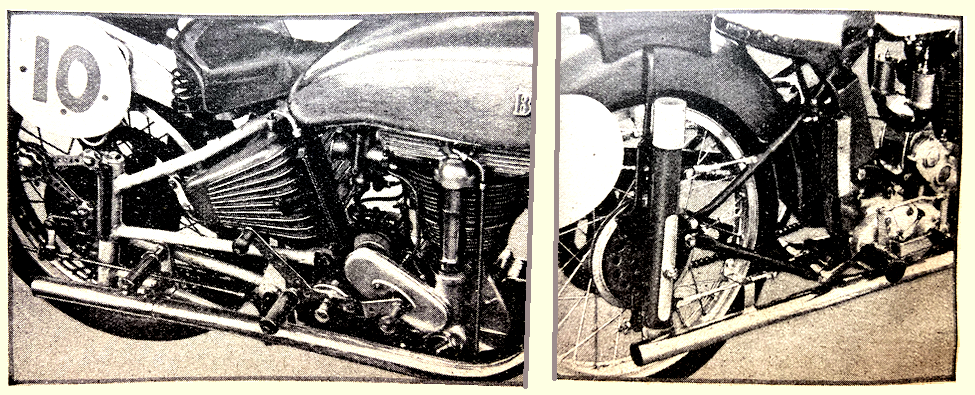

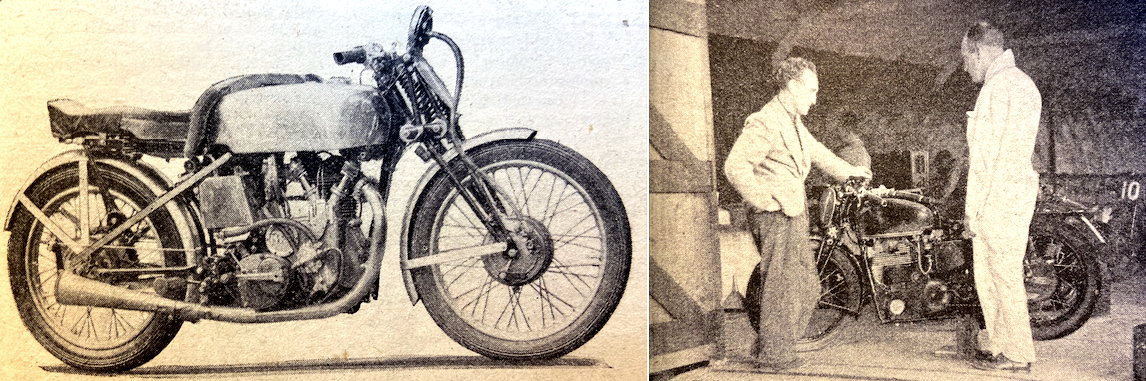

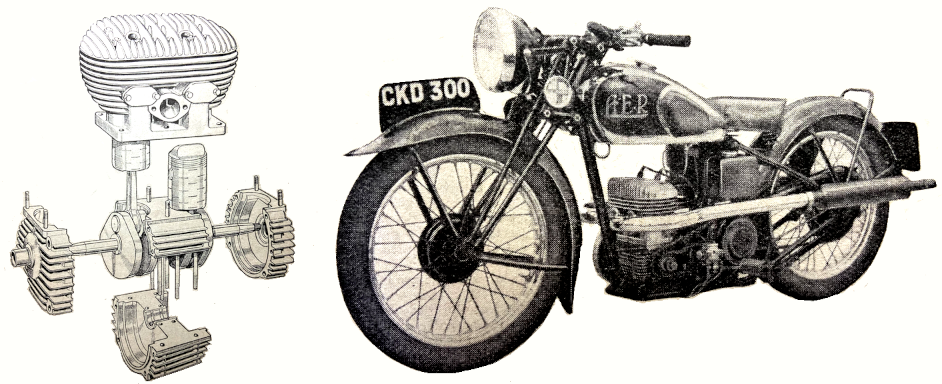

“AN ENGINE OF ORIGINAL type for which phenomenal performance is being claimed has been undergoing development during the past few months. The new unit is the design of FM Aspin, and development is being undertaken by FM Aspin, Egyptian Mills, Elton, Bury. So far the work has been carried out on a 250cc motor cycle engine, but the principle is being applied to car, lorry and aero engines. Unfortunately full details cannot be published at this stage, but an examination of the drawings and component parts confirms the soundness of the ideas on which the claims are based. Briefly, the claims are as follows: The engine will have a range of rpm up to 10,000 or more; compression ratios of over 12 to 1 are possible without the use of special fuels; the scavenging of the cylinder is so complete and the turbulence of the charge is so controlled that the fuel is used about twice as effectively as in a normal engine (therefore the engine does not overheat); even when using commercial grade fuel on a 10 to 1 compression ratio it is possible to use ordinary porcelain insulator sparking plugs; the inlet and exhaust areas are quite unrestricted at full aperture, and are of enormous size in relation to the cylinder bore. Those are the claims. Constructionally the engine is built almost entirely of light alloys, and although its big power output (for the size of cylinder) demands an exceedingly robust crank case, the weight of the experimental 250cc engine is only 48lb, of which 18lb is flywheel weight necessary to secure good tickover with the high compression ratio. At present the engine is working on a 13 to 1 compression ratio, but it has been run at slightly over 17 to 1. The power developed, it is stated, is in the region of 25-27bhp, comparable with a 500cc super-sports engine of normal design. The alloy cylinder barrel has a. nitrided hardened liner and an alloy head. There are no external working parts and nothing to adjust. Valve gear in the accepted sense is eliminated, but the mechanism that controls the inlet and exhaust is enclosed in the cylinder. head. Once assembled it is quite inaccessible, and automatically provides its own compensation for heat and wear. It absorbs no more driving power than a magneto, and in consequence the mechanical efficiency of the engine is very high. A normal engine, as used in the TT, was converted to the Aspin system some time ago. Since then it has covered a big mileage, in addition to running 280 hours on the bench at between 8,000 and 11,000rpm. The only trouble experienced was due to the T.T. crank case failing to stand up to the power output from the small Aspin. cylinder. An unusual feature of the engine is that with very small modifications it can be operated on either the two-stroke or four-stroke cycle. If used as a two-stroke it develops nearly double the power of the four-stroke at equivalent rpm. Although the engine is capable of such high revolutions it is not dependent for its useful power on this fact alone, for at any given rpm its advantages over existing types are equally apparent.”

“MOUNTED UPON A STAND in the works, [a 250cc Aspin engine] is driving a 5ft 3in propeller through a motor cycle gear box at a speed of about 1,500rpm; the engine is developing about 18bhp at 5,000-5,200rpm. Exhaust noise is not excessive, even with an open exhaust port, for there is no high-pitched crackle such as results from a normal ohv engine with racing valve-timing. One of the claims for the Aspin engine is that combustion is as nearly complete as can be attained in practice and that the exhaust therefore is free from flame, heat or excessive noise. That a ‘cold’ exhaust has been achieved is a fact, because the hand that wrote these words was passed across the open exhaust port at a distance of two inches when the engine was doing 5,000rpm, and the effect was much the same as the warm breeze that wafts from a barber’s electric hair drier. Look ing straight into the exhaust port, not a sign of flame or colour of any kind could be observed. An ordinary three-point Lodge touring plug is used, and the compression ratio is 14 to 1. More remarkable still, the fuel used is Shell-Mex commercial spirit with a 30-40% addition of ordinary paraffin! The consumption is 0.34lb per bhp hour—only a little over half that of normal engines. When the engine was seen recently it had done 620 hours at 5,000rpm without attention…”

“I READ WITH INTEREST the details of the Aspin engine. No doubt this is yet another experiment which, though vastly superior to any commercially obtainable engine, will be completely ignored by the manufacturers. Surely some method can he found whereby such revolutionary engines may become obtainable as standard productions? Maybe our ultra-conservative manufacturers would begin to take notice if one of these engines won the TT or Manx GP. It seems fairly obvious now that the present-day engine has reached the limit of its performance, and unless something is done very shortly our precious prestige will be collared by the Continental firms who do, at least, show initiative. But no; the manufacturer prefers to effect ‘detail modifications only’ and continues to produce the same machine year after year. Of course it is sold—because the buyer has no alternative—so the state of affairs continues indefinitely. , There was once a time when aero engine designers looked to motor cycles for inspiration. No longer is that so; motor cycle engines are where they were 15 years ago, except, of course, for ‘detail modifications’.

Cynic, Amersham, Bucks.”

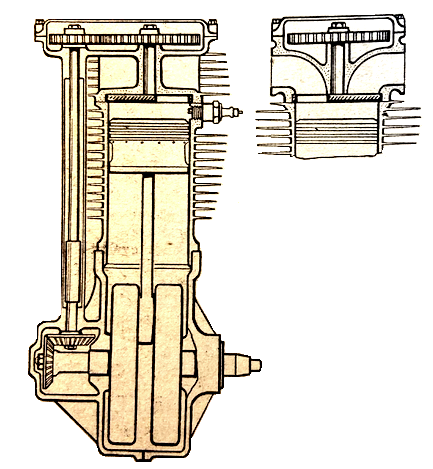

“UNORTHODOX ENGINES—A Hollander’s Design. ‘With regard to the engine described in The Motor Cycle, perhaps the following would be of interest to others: Some years ago I designed an engine with as far as I can see from the photographs, exactly the name method of operation. The two sketches roughly illustrate my design. Instead of valves there is a rotating disc. This disc is fixed on an axle which has a cam wheel, and the cam wheel is driven by the same mechanism as used on ohc machines. On the rotating disc there are large inlet and exhaust ports of special shape and dimensions. The sketches are not quite correct with regard to the relative positions of the inlet and exhaust apertures. The light disc will permit high revs and the large apertures provide good filling and scavenging. I should like to congratulate Mr Aspin on his excellent design, the more as I realise that years of hard work and deceptions must have preceded this new engine. Cordial greetings to all English motorists.

CS1 Norton, Amerstol, Holland.”

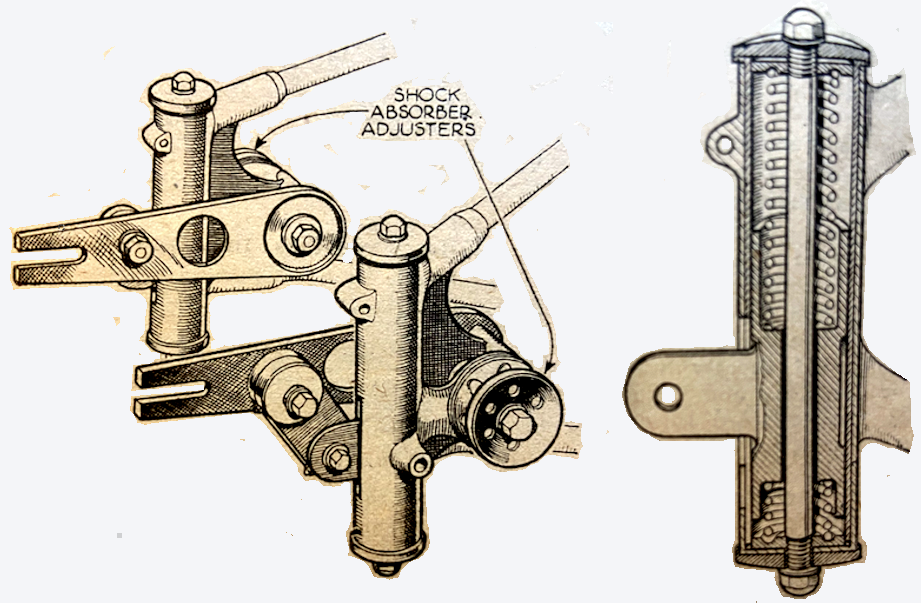

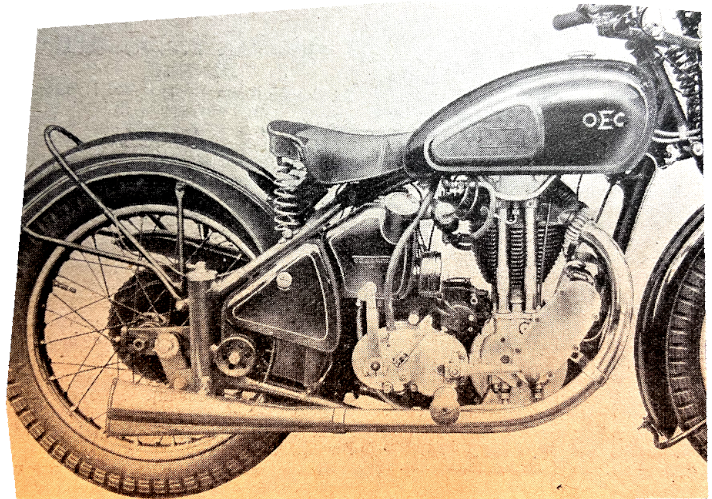

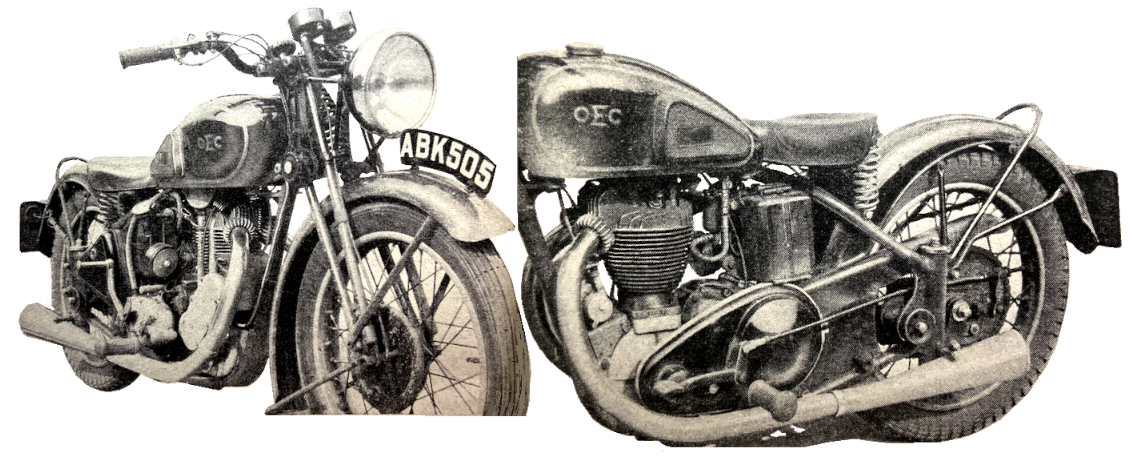

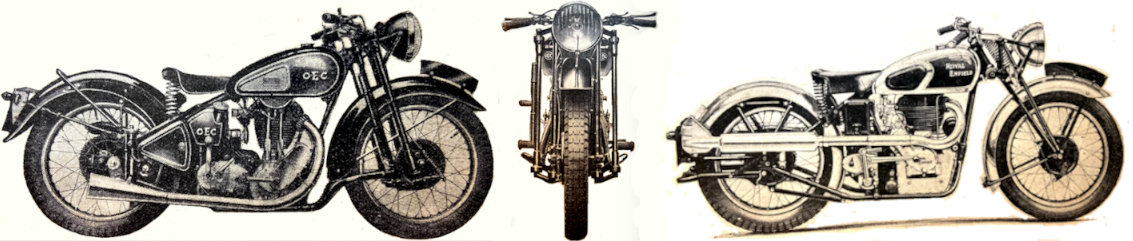

“THE PROBLEM OF producing a spring frame that is neat and efficient, yet which does not add appreciably to the cost of the machine to which it fitted, appears to have been successfully tackled by the OEC concern. More than that, they have introduced an entirely new range of machines which in design and appearance reach a very high level. There are four models in the range—two-port ohv singles of 250, 350 and 500cc, and a side-valve 1,000cc twin. All have engines specially made for OEC by the Matchless-AJS factory. For the purposes of description the 500cc model may he taken as typical, although in the case of the 250 the construction is lighter. The new frame, which is of the duplex cradle type, is particularly sturdy. It has a l¼in diameter front down tube and a 1in. single top tube (instead of the twin tubes used previously), while the seat stays are also of lin diameter. It is, however, in the system of rear wheel springing that the most interesting development is to be found. For instance, the spring boxes are of larger diameter (2¼in externally) and much shorter, and they are now fitted with detachable liners. Internally, the system comprises in the case of each spring box one long upper spring and one short

lower one, with a piston-type plunger interposed between the two springs. An arm attached to the piston protrudes through a slot in the spring box and is connected to the fork-end by a short toggle. The phosphor-bronze bearings in the connecting arm are adjustable to a slight extent as regards end-play. The springs are retained by detachable end caps that are secured by means of a long ½in. bolt that passes right through the spring box. Thus it is a simple matter to dismantle the boxes and effect any renewals. The fork-ends themselves pivot on large-diameter phosphor-bronze bearings formed in the spring-box castings, immediately in front of the boxes. These bearings are provided with adjustable hand-controlled dampers. Throughout the system the bearings are of unusually large diameter and are provided with grease nipples. Another important feature is that the chain tension remains practically constant. As regards the general features of the new models, all have black tanks with gold lining, and embossed makers’ initials. Capacities are 250cc, 2½ gallons; 350cc and 500cc, 3 gallons; and 1,000cc, 4 gallons. All-black handlebars and chromium-plated wheel rims further enhance the neat appearance of the machines.”

“TWO LENGTHS OF roads at Oxted (Surrey) have been freed from the speed limit. The speed limit has been imposed on a length of the London-Eastbourne road near South Godstone School.”

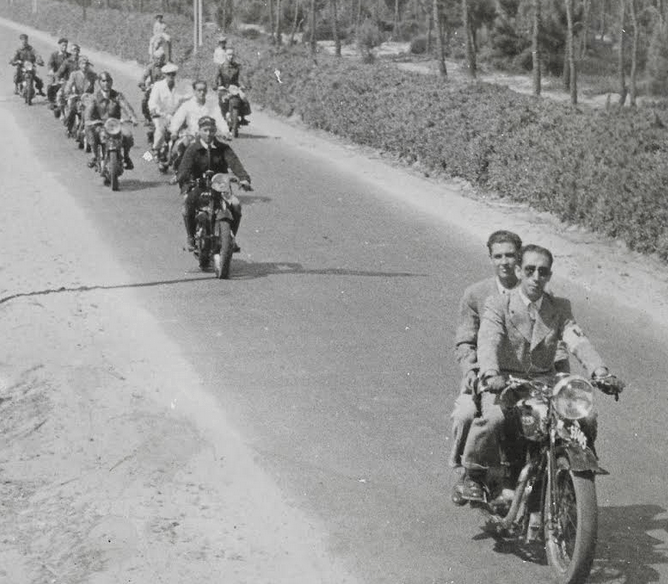

“NEARLY 2,400 ITALIAN enthusiasts took part in the recent Winter Rose Rally, held in connection with the Milan Show.”

“SUMMONED AT ROMFORD (Essex) for careless driving, a motorist pleaded that a sunset over the Thames Estuary distracted his attention.”

“ADVICE CENTRES FOR MOTOR cyclists are to be arranged by the BMCA. These centres will be open to all motor cyclists and advice will be given free of charge on all motor cycling matters: They will be attended by an official of the BMCA and a member of the Metropolitan Committee of Motor Cyclists. The free advice service also covers queries sent by post. This service has always been available to members, but now non-members are invited to take advantage of it, providing they include a stamped addressed envelope for reply. The BMCA is not, however, prepared to give technical advice to non-members, or to involve themselves in expense on their behalf; this would obviously be unfair to members.” The British Motor Cycle Association was concerned by the strength of public prejudice against motorcycles and motorcyclists. Asserting that “the motor cyclist handles his mount with greater skill than any other type of road user” the BMCA issued (for five bob a year) machine badges indicating the number of years the rider had escaped prosecution for any motoring offences.

“A NORTHERN READER, newly returned to his birthplace from the south, urges me to demand why that typical north-country dish of ham and eggs (a) cannot be obtained south of Lancashire, and (b) why, to use an Irishism, if you insist on it being served, the ham is never really eatable? Southron readers, for the most part, have never sampled this excellent viand. The ham I should explain, is no measly, waferlike rasher such as first-class southern hotels substitute for the genuine article, but approximates more to the dimensions of a chump chop, and may be a good 1½ inches thick if callipered at maximum bore. My northern friend asserts, with some justice, that after one has covered 100 miles in the saddle on a cold day this dish, washed down by beer or tea according to your liking, is infinitely preferable to the usual hotel menu, and can be prepared by a cook in a very short time if the traveller arrives when the set meals of the house are ‘off’. Perhaps some sonsie* north-country wife will send the Editor directions for cooking the ham properly, so that it melts on the tongue and doesn’t need champing† like an old boot sole; and then south-country eating places might take notice, and serve to order.”—Ixion

*Sonsie (sonsy), according to the OED, equates to “Plump, buxom; of cheerful disposition; bringing good fortune”. †Champ: “Munch (fodder) noisily; work (bit) noisily in the teeth “qv “champing at the bit”.

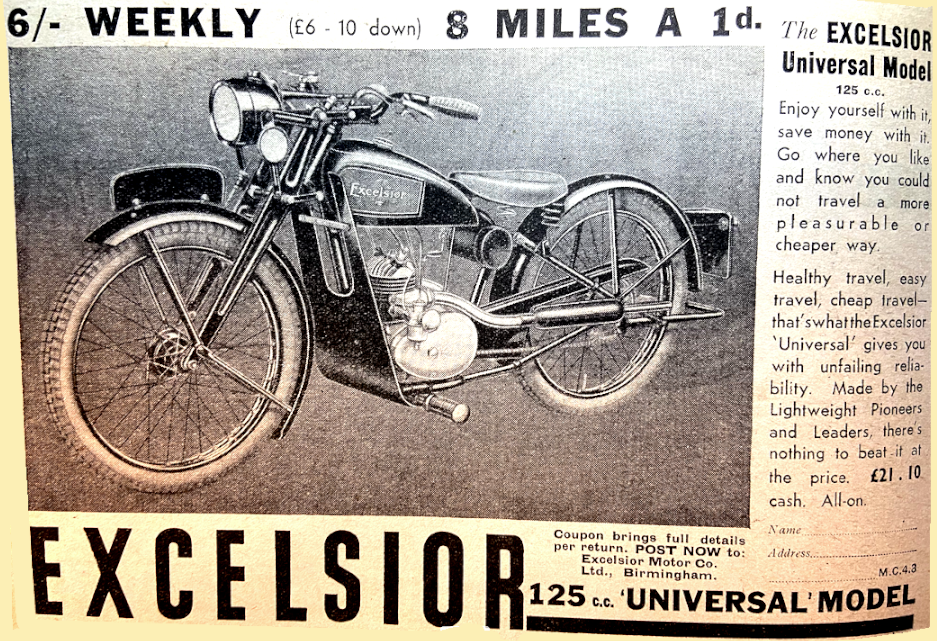

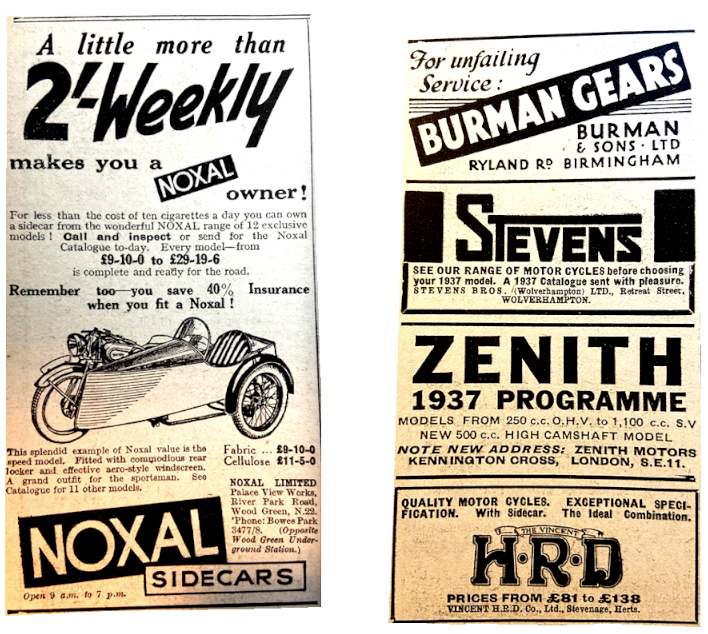

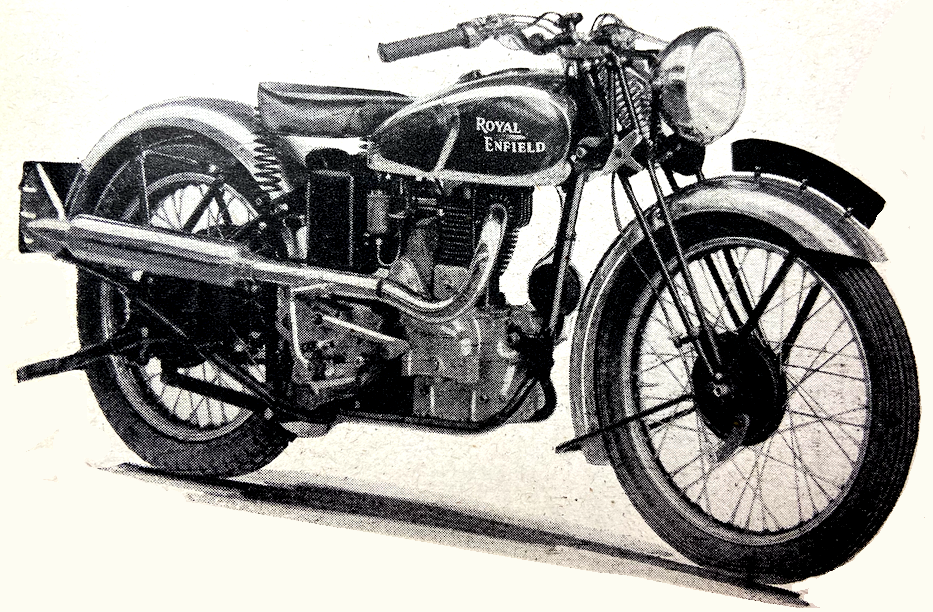

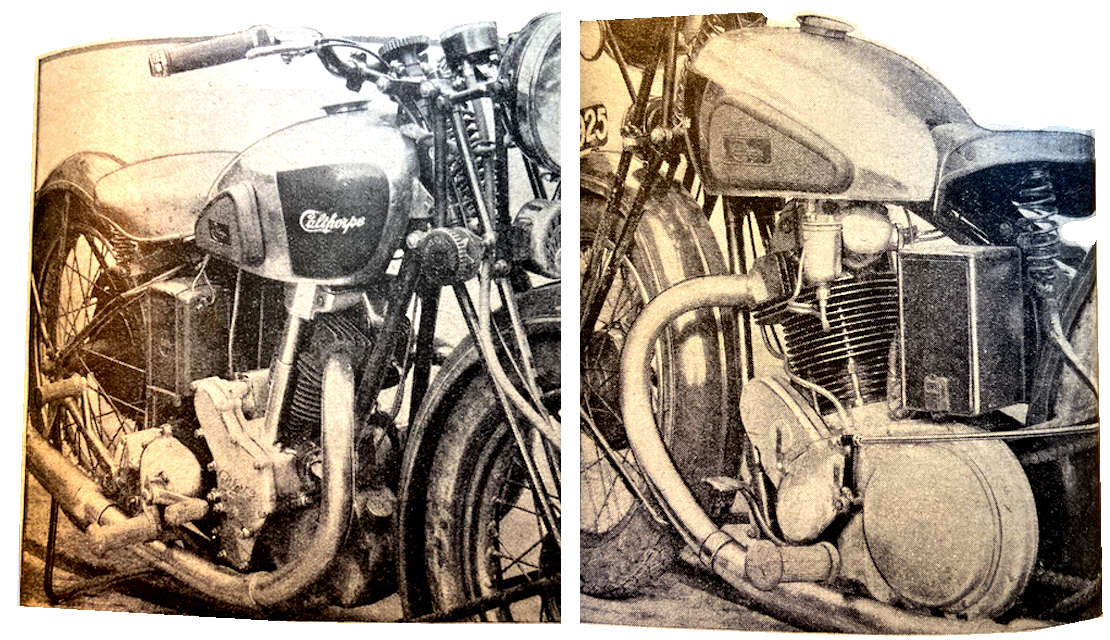

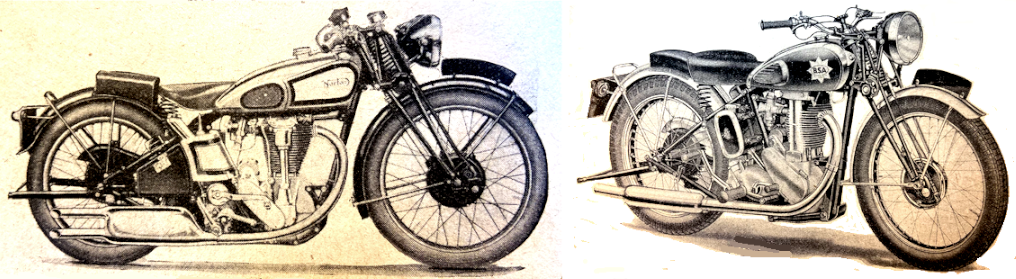

The Motor Cycle Buyers’ Guide listed every marque on the British market: AJS, AJW, Ariel, BSA, BMW, Brough Superior, Calthorpe, Chater-Lea, Cotton, Coventry Eagle, Cyc-Auto, Douglas, Excelsior, Federation (made by the Co-operative Wholesale Society), Francis Barnett, Harley Davidson, Indian, James, Levis, Matchless, Montgomery, New Imperial, New Gerrard, Norton, OEC, OK Supreme, Panther, Rudge, Royal Enfield, Scott, SOS, Stevens, Sunbeam, Triumph, Velocette, Vincent-HRD, Wolf and Zenith.

WANDERING THROUGH A motor cycle factory always makes me wonder what proportion of the cost of a new machine goes in what one may term non-essentials. You come to a press busy turning out steering damper plates, another machine drilling the holds in oil-bath chain cases, a third producing bits used in rubber-mounted handlebars…Not so many years ago a motor cycle consisted of a diamond frame, a pair of forks (without dampers), a simple three-speed gear box, two wheels and an engine. This is not quite the whole story, but very nearly so. Now we have four-speed boxes, separate oil tanks, square feet of chromium plating, enclosed overhead valves, electric lighting, fork and steering dampers, much more elaborate brakes, force-feed lubrication of the dry-sump type, quickly detachable wheels in some cases and all manner of other things. On my recent visit to a factory, half the work seemed to be in connection with items we did not have a dozen years ago. Now, I suppose, these self-same parts have become essentials!”

“A THING WHICH SURPRISES me is the small number of motor cyclists who have their speedometers illuminated at night. Perhaps it is because I ride so many different machines per annum that I look upon speedometer illumination as essential. Maybe the majority of motor cyclists who ride one machine and one machine only, can tell by ‘fee’ whether their mount is doing 28 or 30mph. I have my doubts, and suggest that if no speedometer light is provided by the manufacturer, and the machine is ever used at night, it is advisable to buy and fit a speedo lamp and thus be on the safe side.”

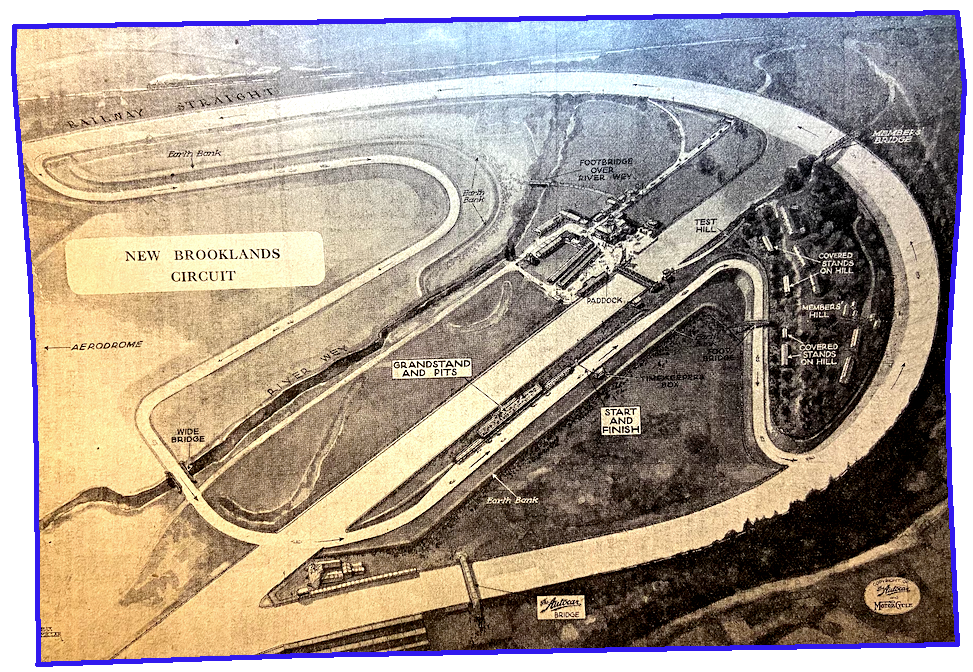

THE SHORT REIGN of Edward VIII is of no interest to us as he took no interest in motorcycles. But when he abdicated to marry an American divorcee he was replaced by his Brother George VI who, while still Prince of York, had owned a Douglas and sponsored Brooklands ace SE Wood.

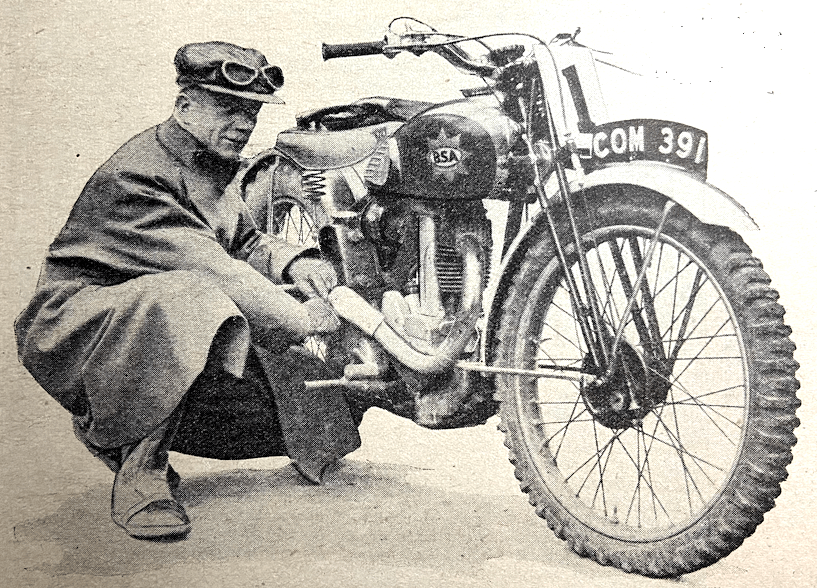

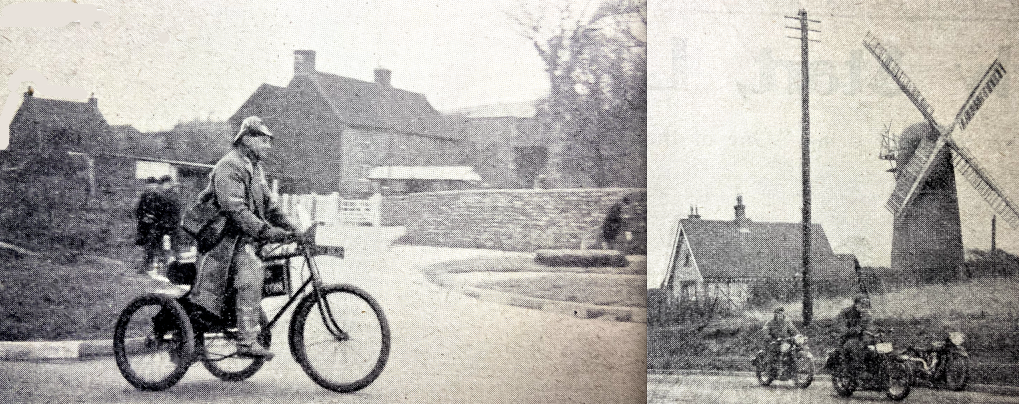

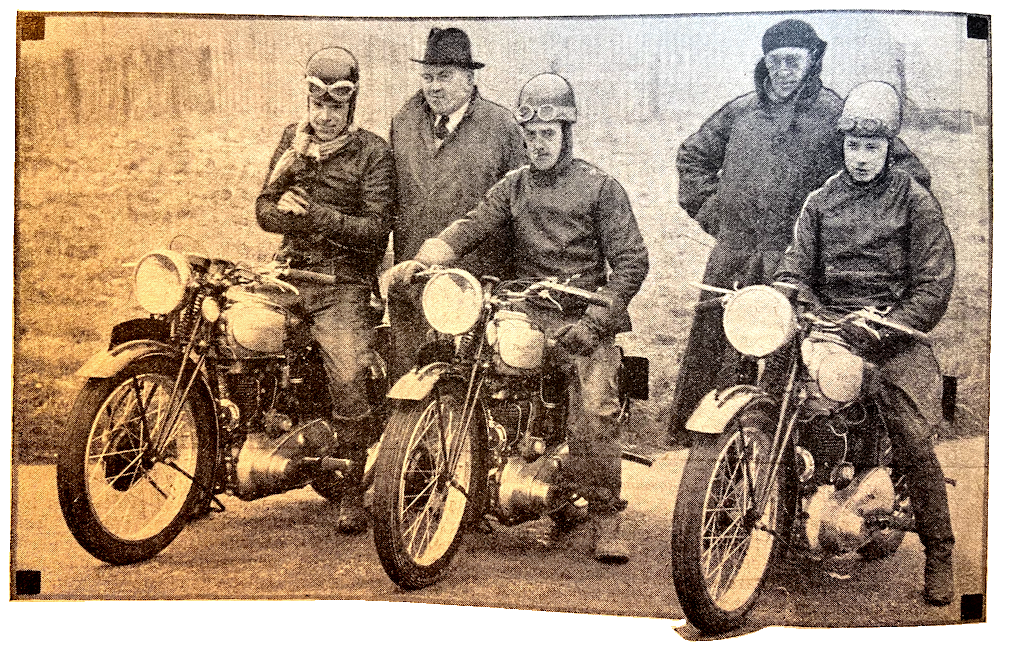

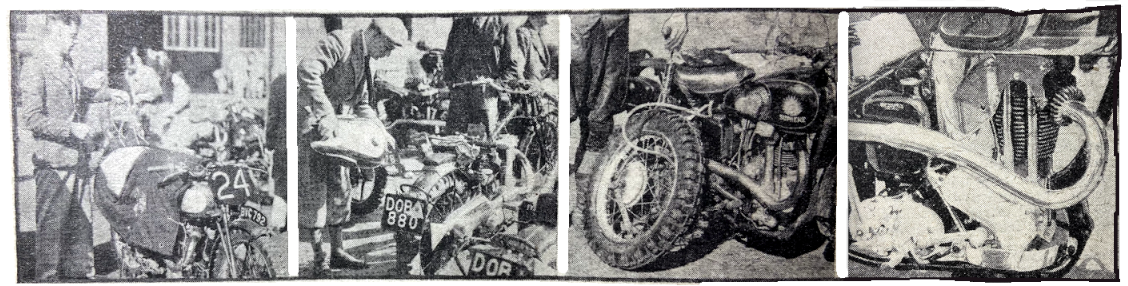

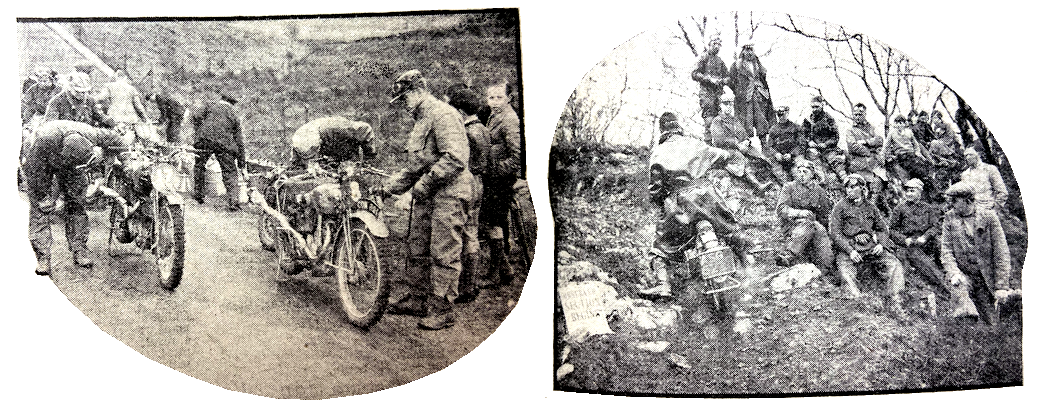

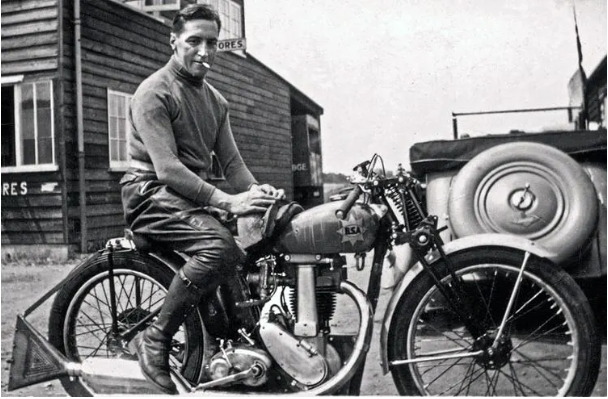

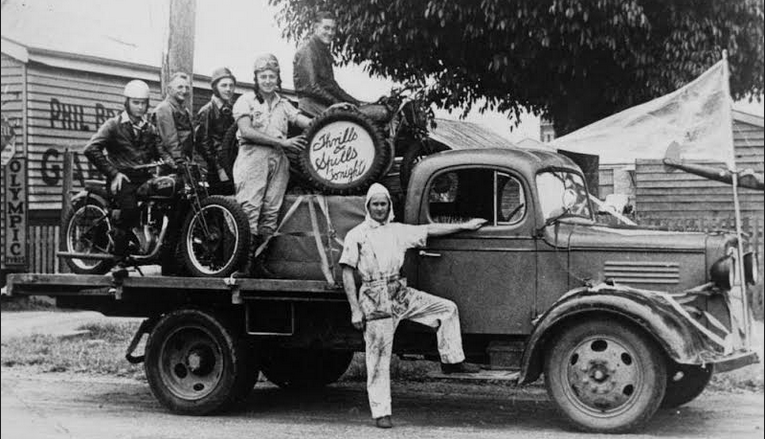

“LAST SATURDAY AE PERRIGO (348cc BSA) won his first Colmore Cup. For some time he has not met with much success, but last week-end, following up his win in the Lister Trial, he found all his old form and beat Len Heath by a narrow margin, the issue eventually being fought out in the brake test. Perrigo ‘s seven marks were lost on one hill, Sainthury, whereas Len Heath (497cc Ariel) dropped a foot on three hills, Meon, Saintbury and Warren. These two were run very close by George Dowley (246cc AJS) and Alan Jefferies (348cc Triumph), who on observation tied with eight marks lost, and it is a tribute to George’s riding that on a machine of so small a capacity he finished so high in the list—and a tribute to the machine! It would be unfair to pass over individual performances without mentioning DK Mansell (490cc Norton sc). With only one failure and three marks lost for footing, his effort ranks very high indeed. The gales and blizzards of the previous week had been forgotten, or almost so, when last Saturday dawned, and the Cotswolds basked in the welcome sunshine of a perfect day. There had, however, been sufficient bad weather to make the course difficult, and competitors found their work well and truly cut out on Meon, Saintbury, Warren and Camp hills. At Stratford-on-Avon, Sunbac officials, headed by the president, were going cheerfully about their work, large cars drawing trailers drove up in quick succession—some people even arrived on motor cycles—and the Trade was well represented.”

The Blue ‘Un devoted an issue to recruiting converts to motor cycling, including anecdotes of how youngsters found their first bikes. Here are two examples; one charming, t’other…not so much.