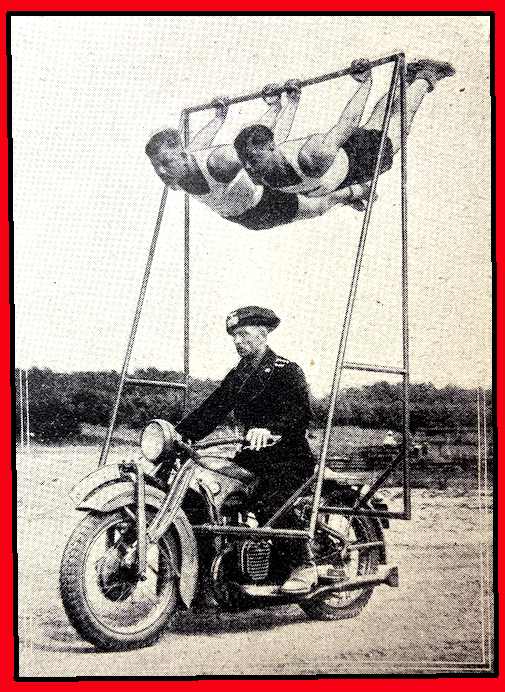

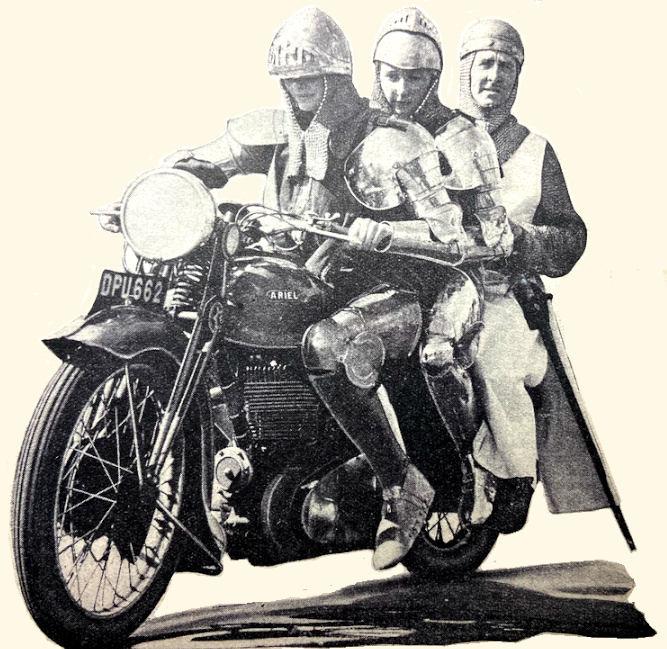

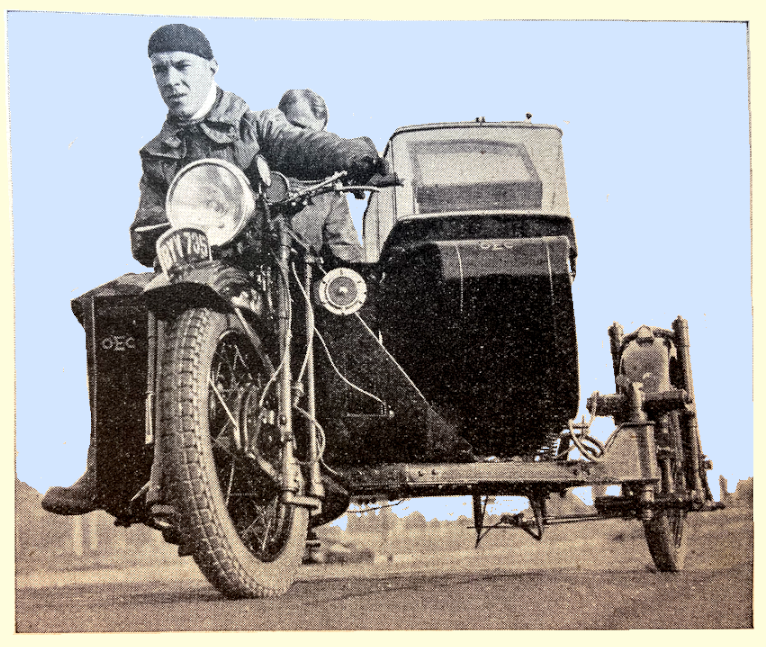

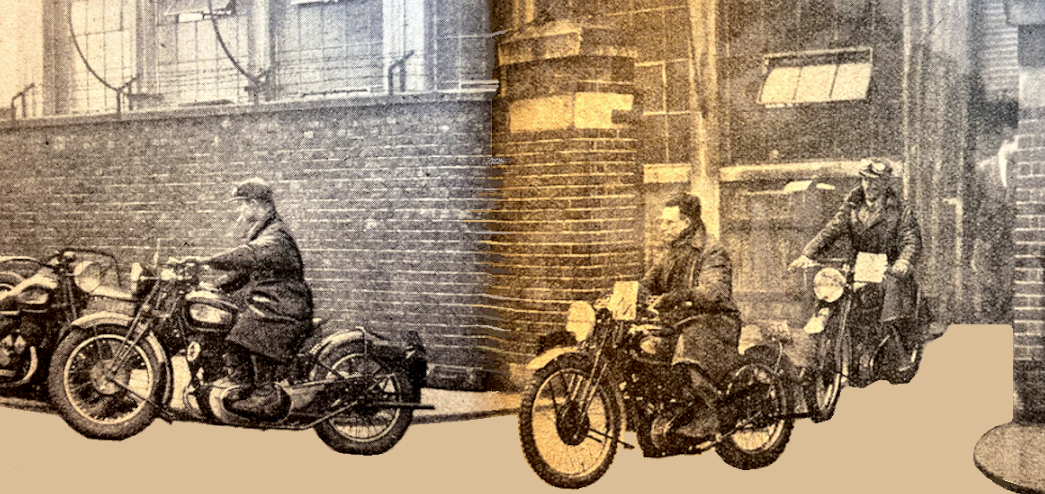

“MORE MOTOR CYCLISTS are using their machines all the year round…Three out of four motor cycles in August of last year were still in commission at the end of November…the number for last February was over 63% of the figure for August—and was 30,000 greater than that of the previous year. That a large proportion of motor cyclists now use their machines winter as well as summer is testimony to their good sense and, more particularly, to the stability of the modern motor cycle. Even on the recent days of snow and ice many motor cyclists were to be seen on the roads. To-day the stability of the two-wheeler is little short of extraordinary, while as for the sidecar outfit, as the world knows, this has long been proved to be the safest mechanically-propelled vehicle of all.”

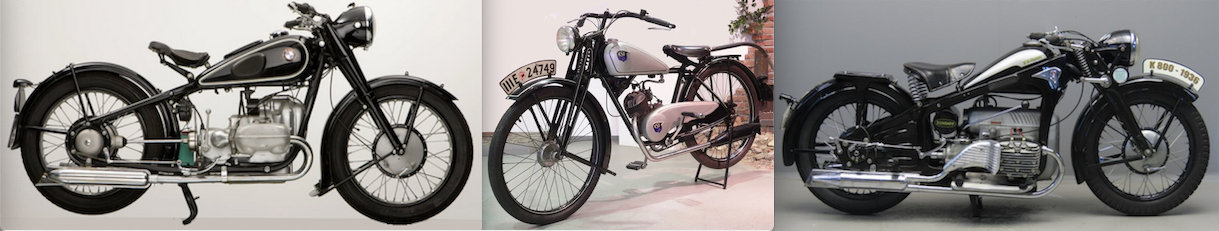

HITLER PROMISED THAT within 18 months Germany would no longer need to import petrol and that within four years it would be making enough synthetic rubber to meet its needs. There were sustained calls for similar moves in Britain where it was said our vast coal reserves could have made us self-sufficient in fuel.

A COAL-TO-PETROL PLANT opened at Erith, Kent. Each ton of coal was said to produce 15gal of petrol, 20gal of diesel and 15cwt of smokeless fuel. Japan also built a coal-to-oil plant.

OBSCURE BUT TRUE: for the first time all automotive bulbs had to be marked with their wattage; headlights over 7W had to be turned off as soon as the vehicle stopped moving.

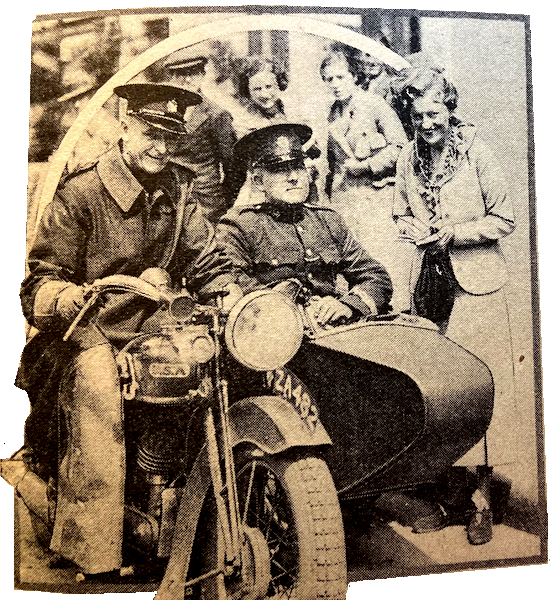

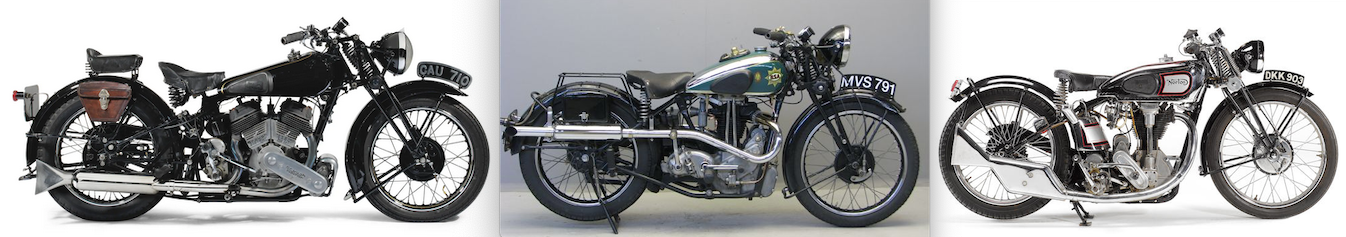

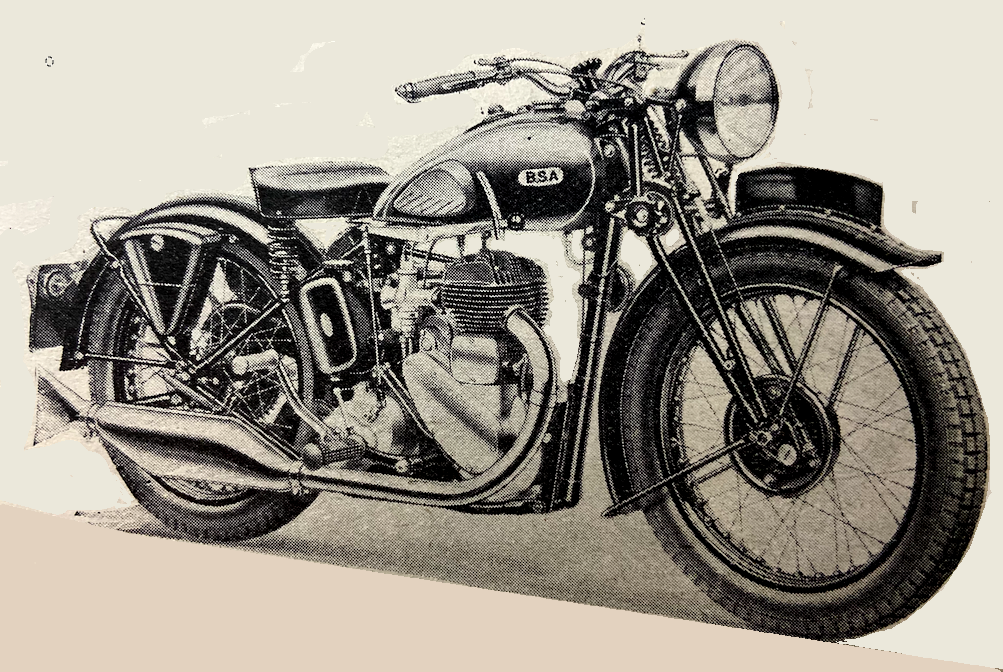

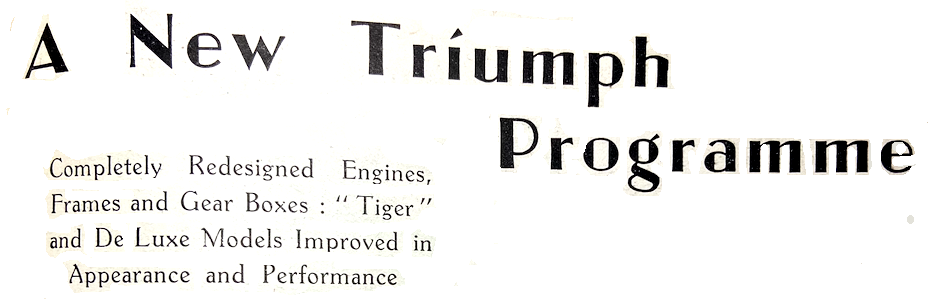

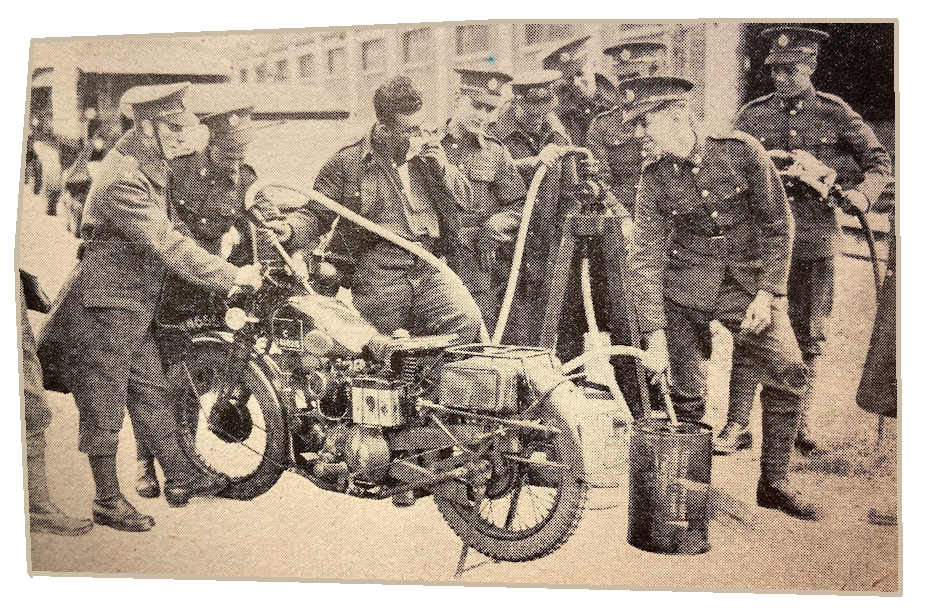

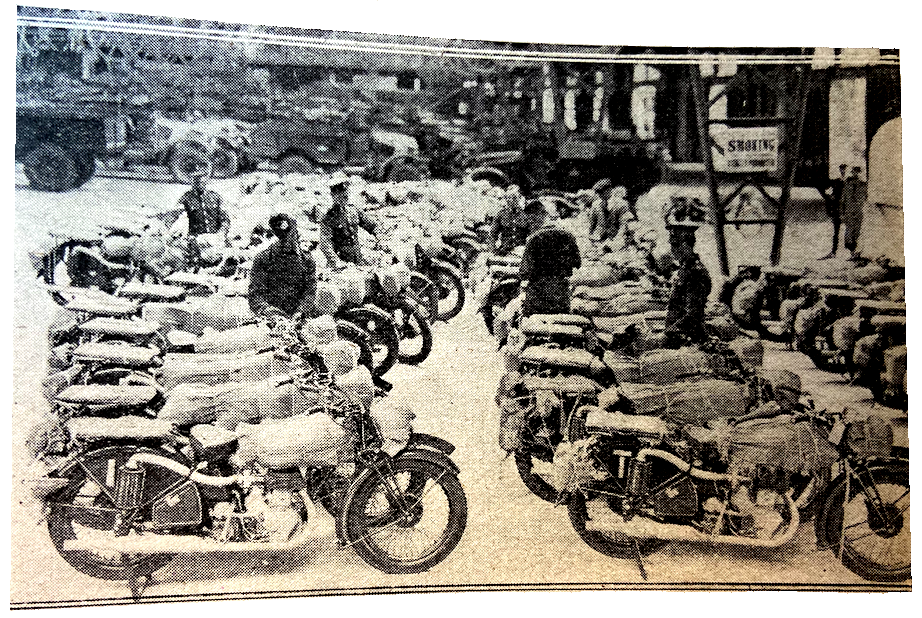

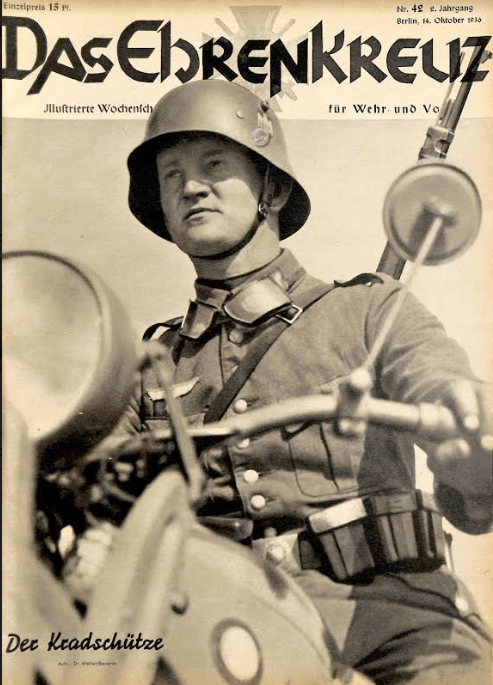

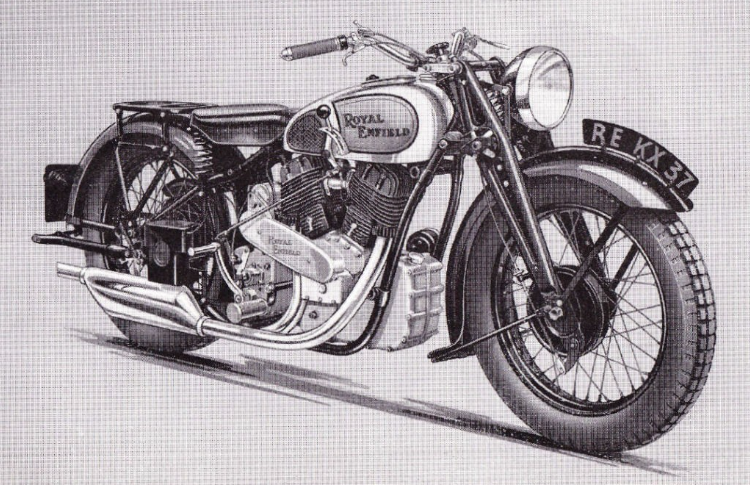

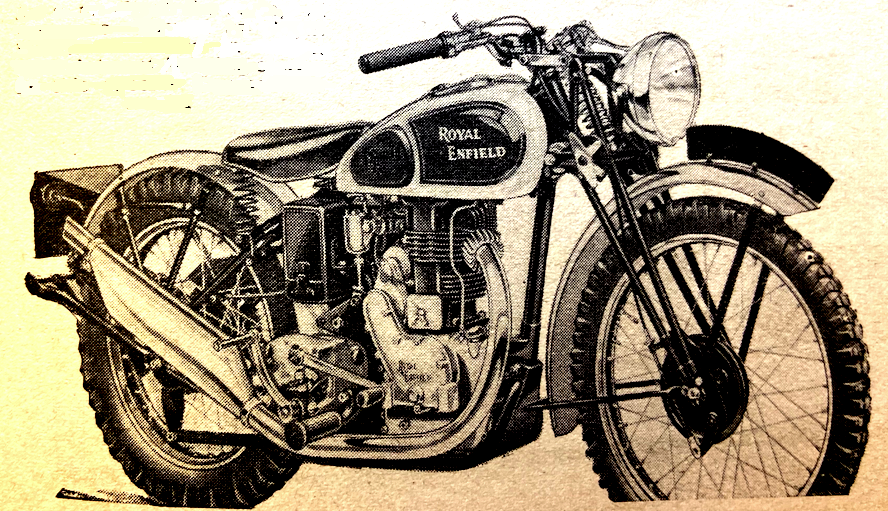

THE GOVERNMENT NEEDED MONEY for re-armament and decided roadtax no longer had to be spent on the roads. Part of the diverted Road Fund would be spent on motorcycles: the Army was keen to standardise on a bike to replace its V-twin Beezas, sidevalve Triumphs and flat-twin Douglases so BSA, Norton and Rudge were invited to submit machines for a 10,000-mile evaluation. Norton’s well-proven 500cc sidevalve 16H won the day and 100 were immediately ordered to equip troops en route to Palestine. The war office decided a lightweight was need for training and bought a batch of G7 250cc Matchlesses as well as a batch of G3 ohv 350s.

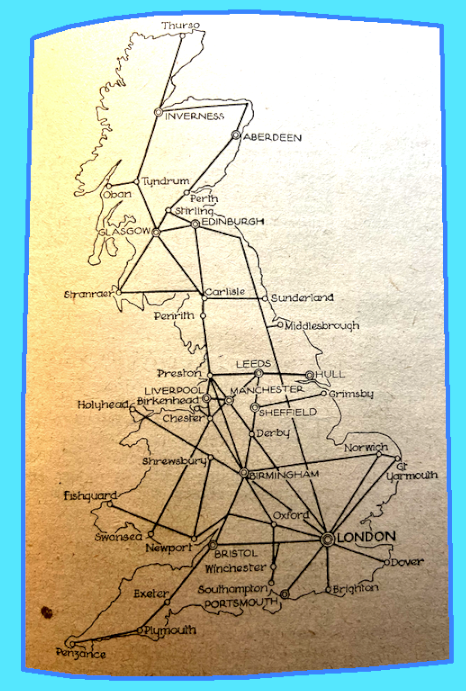

AS THE FIRST step towards establishing a national road system the Trunk Roads Act transferred responsibility for 4,500 miles of main roads from local authorities to the Ministry of Transport. But with more than 1,400 independent road authorities looking after 180,000 miles of roads there was a long way to go.

TRANSPORT MINISTER Hore-Belisha noted that 500 motorised vehicles had been registered ever day since he took office two years before (a total of some 183,000). He announced plans to ban L-riders from taking pillion passengers and appointed a corps of Divisional Accident Officers to investigate accidents. They were all experienced road users; at least one rode a motorcycle to work.

THE BRITISH Motor Cycle Association drafted a Motor Cyclists’ Grand Charter including a proposal for police courts to sit in the evenings, allowing misbehaving motorcyclists to face the music without the added penalty of losing pay by attending court. Its case was put to the Home Secretary by Captain Strickland MP who, as a committee member of the BMCA, gave motorcyclists a voice in Parliament. But to no avail: the courts remained firmly closed outside office hours.

MANY RIDERS had been fined for trickling over the line at the new ‘Halt’ signs when the road was patently empty of all other traffic but their complaints came to nought—a High Court judge decided that signs meant just what they said. Even on an empty road every vehicle had to come to a standstill.

THE METROPOLITAN Committee of Motorcyclists (MCM) was formed by a collection of London bike clubs “to campaign agains the increasing injustices which the motorcyclist has to bear”. These included the Police Court practice of forcing riders to pay court costs even when they were found innocent of any wrongoing—and the fact that a single copper’s allegation was usually enough ‘evidence’ to secure a conviction.

LORD NUFFIELD DENOUNCED the “persecution” of motorists: “No matter how law abiding a motorist is, he must have luck on his side of he is to avoid trouble with the police.” He called for specialist motorists’ courts, staffed by magistrates with some knowledge of motor vehicles. Not all cases were contentious—a cop giving evidence in the Highgate Police Court solemnly told the magistrate: “At the defendant’s request I showed him our stopwatches. He said, ‘Tick tock tick tock, old chap’.”

A FRENCH RAILWAY company was using a fleet of 250cc combos set up to run on road and rail for track inspections.

A CROYDON motorist convinced traffic cops he was sober enough to drive by writing his name and address backwards and performing tricks with three matches and two glasses of water. Things were less flexible in Germany, where any driver or rider involved in an accident was bloodtested for alcohol abuse.

IN THE US an inner tube was marketed with a two-year ‘no-puncture’ guarantee.

THERE WERE 22,395 bikes on Kiwi roads.

AT A DINNER to mark the centenary of roads pioneer Macadam, the great man’s great great grandson called for roads to be paved with rubber.

FANCY THAT DEPT: A one-armed Bradford vegetarian set an English record by covering 36,000 miles in the year on his bicycle.

AT YEAR’S END 516,567 motorcycles were registered in Britain. January-October registrations were up 17% year-on-year to 49,820. Exports rose 22% to 16,399 despite tariff and currency restrictions. Leading importers of British bikes were Australia, South Africa, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland. However a large batch of Triumphs went to Iraq; King Ghazi was a confirmed Triumph enthusiast.

ANYONE WHO committed three motoring offences in New York was automatically jailed.

RUDGE, NOW BACK on a sound footing, was bought by music company His Masters Voice (still in business as EMI).

AN ENGINEER proved, with the aid of graphs, that a 100mph TT average was a physical impossibility.

A FILLING STATION attendant in Miami builT a petrol-fuelled steam bike that returned 50mpg.

THE ITALIAN industry was building some exquisite lightweights for road and track.

GLOUCESTERSHIRE County Council fitted some green kerbside mirrors to help cut accidents in fog.

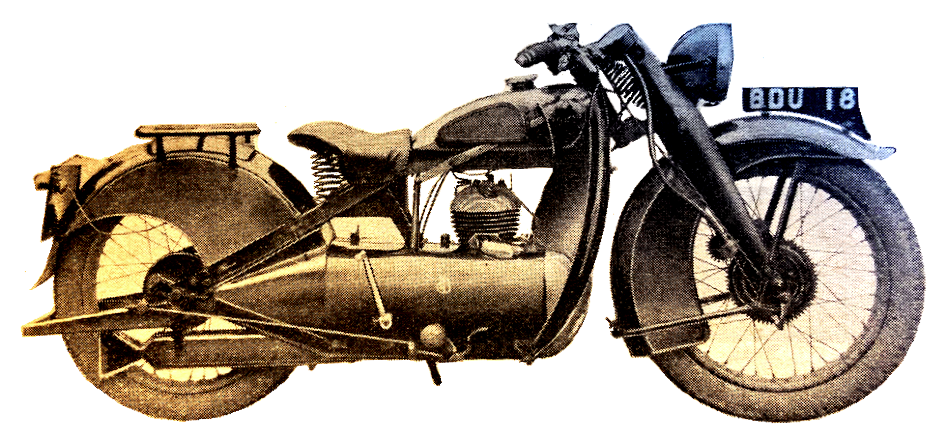

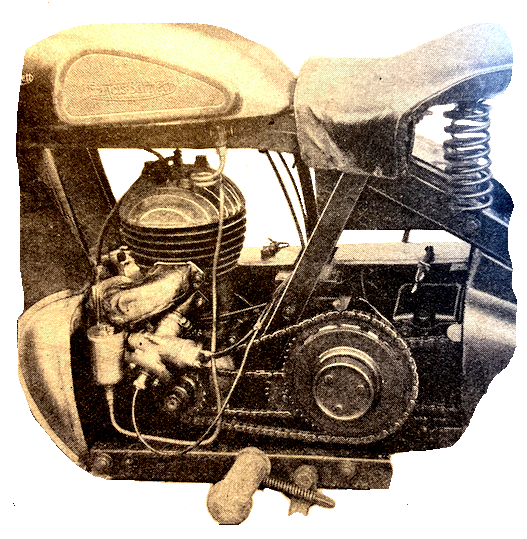

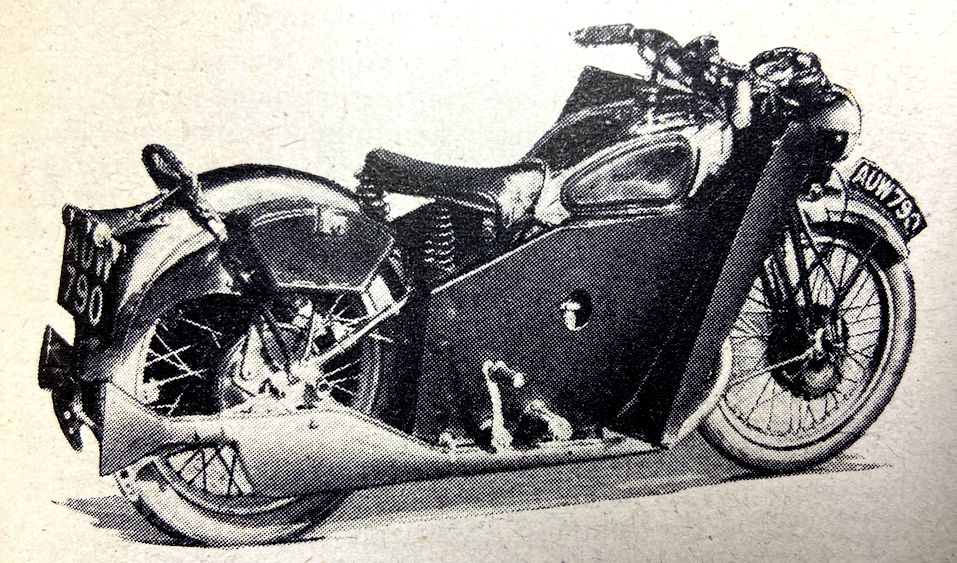

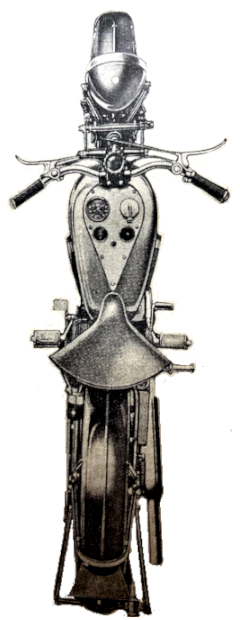

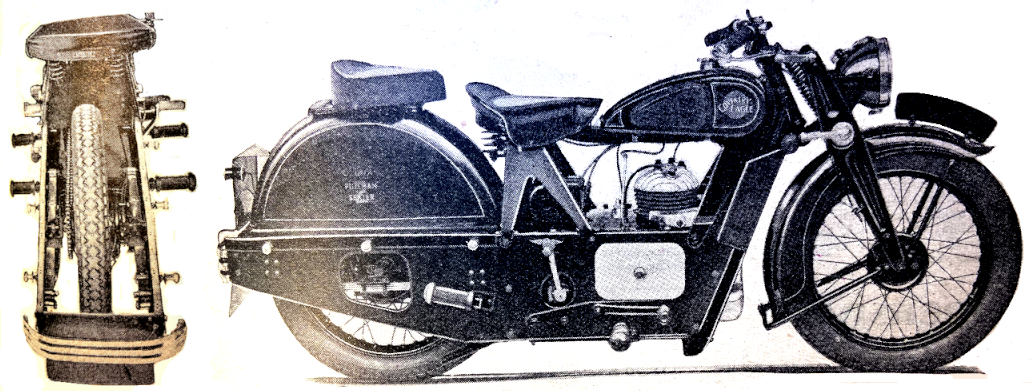

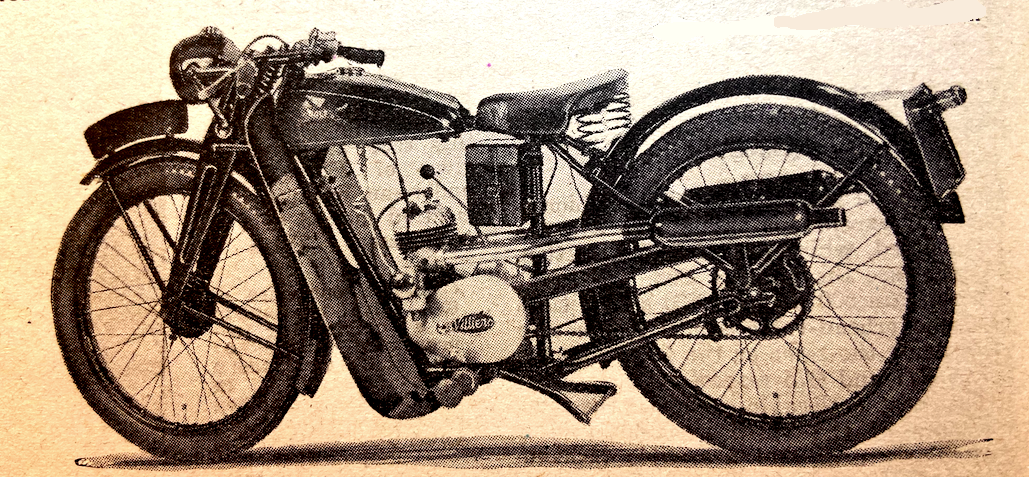

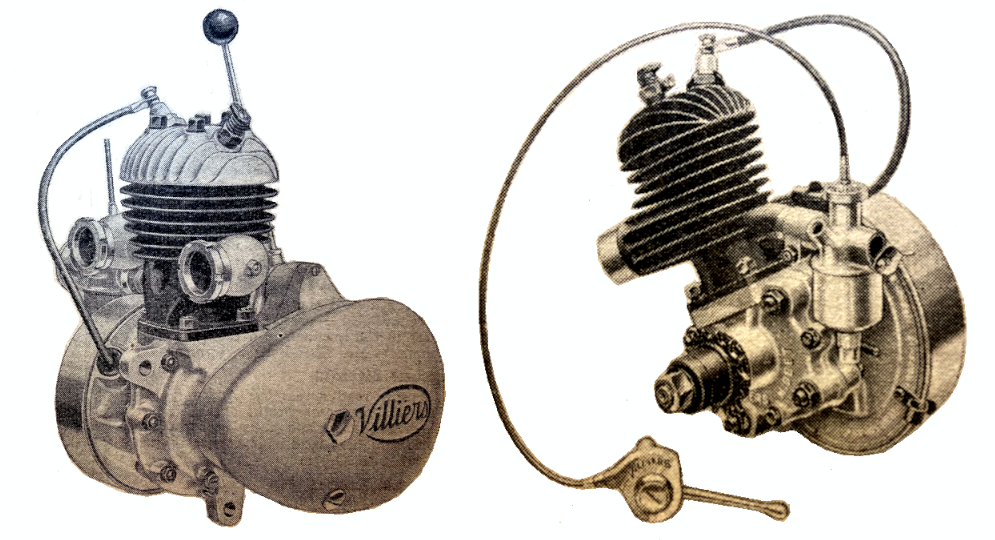

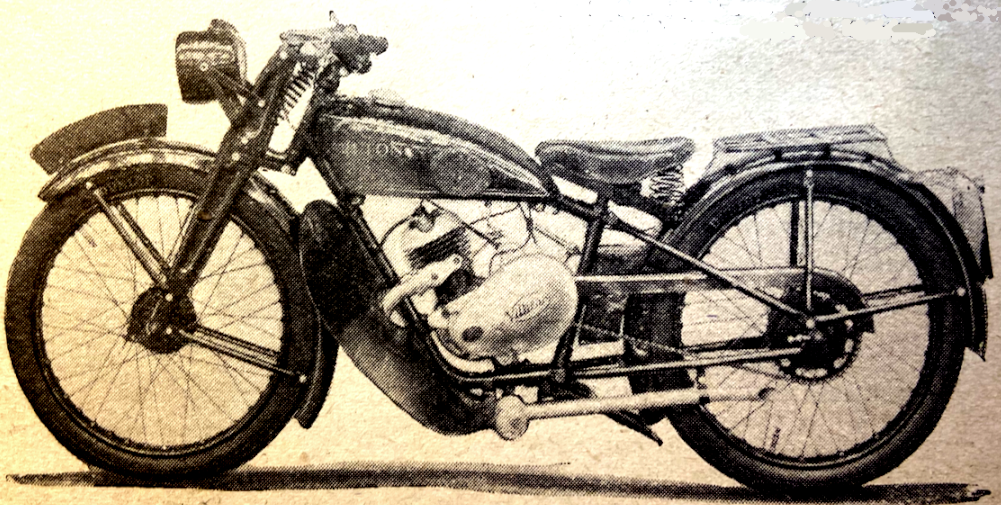

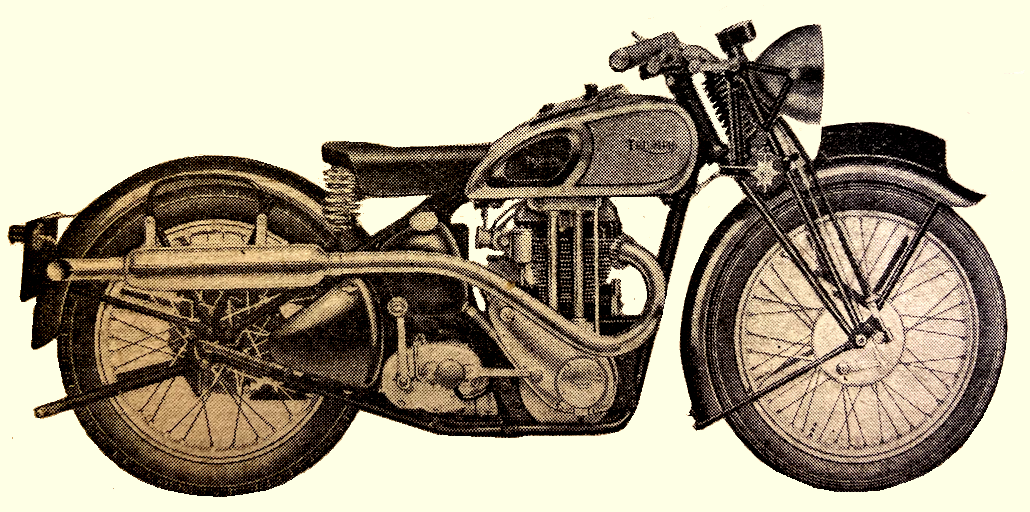

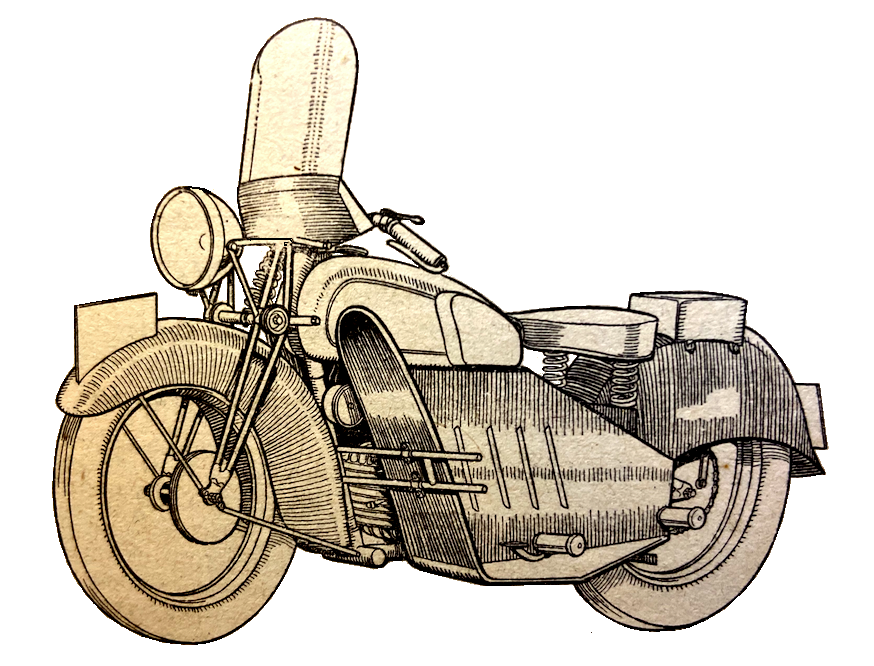

“WHEN THE FRANCIS-BARNETT CRUISER was introduced in 1933 it was immediately recognised as one of the outstanding models of the day. Subsequent tests showed that the performance of the model was well in keeping with its looks, and it rapidly gained an enviable reputation. This reputation is more than uphold by the 1936 edition of the Cruiser fitted with the 249cc Villiers deflectorless-piston engine. The most outstanding features of the model are the comfort and cleanliness that it affords the rider. Handlebars, footrests and saddle are well placed in relation to one another and really do give ‘armchair’ comfort. The pan-type saddle is exceptionally wide and has long supple springs, while the handlebars are of such a shape that the hands rest comfortably upon them. No oil or dirt from the engine can reach the rider’s clothing, while the legshields and heavily valanced mudguards are very efficient. Leggings or waders are unnecessary for town work or on short runs in wet weather; and it is only when the rider drives through deep puddles at speed that any splashes reach his legs. After long runs on wet and muddy muds the machine can be cleaned in a few moments, and it is no idle boast of the makers when they say that the machine can be washed down with a hose. Starting at all times proved exceptionally easy. When warm a light dig on the kickstarter was sufficient to set the engine ticking over, and when cold the engine could be relied upon to fire on the first or second kick if the strangler was closed and the carburetter flooded. At no time during the test did the engine stall, and although four-stroking would occur when running light or on the over-run, this was never unpleasant because of the very subdued exhaust note. At all other times the engine was smooth and re markably free from vibration. Flexibility is another of the Cruiser’s strong points. At all speeds above 10mph the engine was quite happy in top gear and from this speed would accelerate

smoothly even if the throttle were snapped wide open. Naturally, to obtain the best acceleration it was necessary to use the gears, and the engine proved lively, particularly in second gear. In third (7.7 to 1), the machine took 13 seconds to accelerate from 20 to 45mph, which is, particularly creditable when it is considered that the maximum speed in this gear was 47mph. In top gear, between the same speeds, the time taken was 20 seconds. Maximum speeds were: bottom gear (16.78 to 1), 27mph; second gear (10.26 to 1), 41mph, and top gear (5.7 to 1), 56mph. These figures were taken with the rider heavily clothed; by lying down the maximum speed in top gear was increased to approximately 59mph. The engine appeared happy at all speeds and on long periods of full throttle failed to show any signs of dis-tress—45mph could be maintained over give-and-take roads without effort or without the slightest tiring of the engine. The steering of the Cruiser is very light and at first there was a tendency to oversteer the machine on corners. Once the rider had become accustomed to this the steering proved to be above criticism. There was no sign of wobble or wander, although the machine was driven over bad roads at various speeds. An exceptionally wide steering lock makes the Cruiser very easy to handle, and it could be ridden round in a complete circle on a secondary road.without removing the feet from the footrests. On greasy city roads the machine was as much at home as on rough surfaces and inspired confidence. During the test many miles were covered on ice-covered roads, but the machine never showed any inclination to skid, although deliberate liberties in the way of cornering were taken with it. Both brakes are powerful and well up to the work required of them. The rear brake pedal is situated conveniently beneath the rider’s right toe, but the lever for the front brake requires rather a long. stretch of the hand to operate it. The same criticism can be applied to the clutch lever, but the clutch is delightfully sweet in action and does not tire the hand even when the machine is used continuously in traffic. To obtain the best gear changes it was found necessary to let in the clutch as the gear was engaged, this being so either from neutral or when on the move. The gear change, however, is very light and the lever is placed so that it does

not foul the rider’s knee. At a maintained speed of 35mph the consumption of petroil was 78mpg. On a run of 170 miles the consumption was only slightly heavier, although the run included many miles of full-throttle work, hill climbing, and much stopping and starting. With the petroil lubrication the oil consumption worked out at 1,300mpg. At the beginning of the test there were two rattles in the machine: one from the toolbox and the other from the front mudguard, which had been damaged in transit. Both were quite easily cured. No rattles emanated from the bonnet sides or legshields. With the bonnet sides removed, the machine becomes more accessible than most, and such items as cam lever adjustment of the primary chain and a quickly-detachable rear mudguard considerably simplify maintenance work. Mounted on the steering head is an instrument panel which houses the lighting switch and ammeter. The Miller lighting equipment proved powerful enough for all normal use, although for fast touring at night a better head light beam would be desirable. During the course of the test the bracket carrying the horn broke away from its fixing; this was the only component with which any trouble was experienced. The makers of the Cruiser have achieved a very high standard of silence with the model. At normal speeds the subdued exhaust note renders the machine quite unobtrusive, and this, combined with the smoothness of the engine and the comfortable riding position, makes the machine a delight to ride under all conditions.”

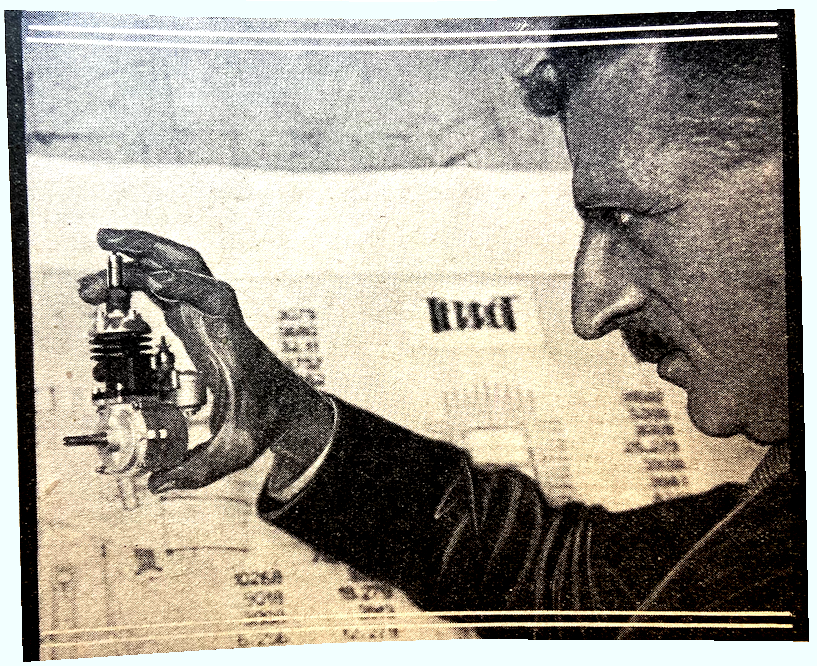

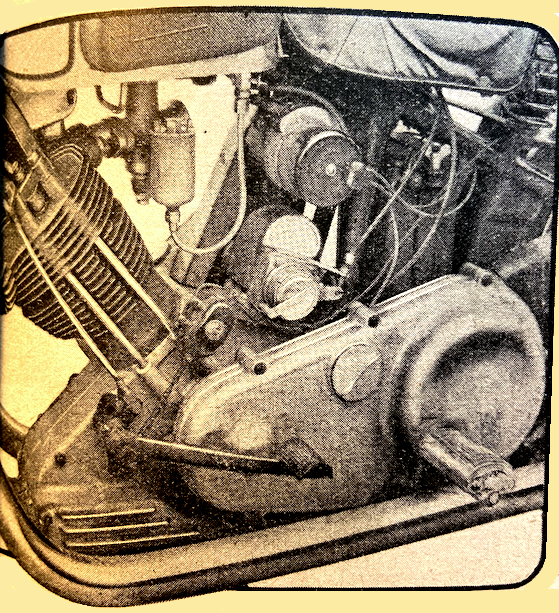

“BEHIND THE SCENES there have been moves with the idea of ensuring that motor cycles are easier to start. The difficulty some riders experience in this direction has been brought home to certain manufacturers. One famous maker admitted the impeachment and added that in his opinion the chief cause of the trouble has been that magnetos were not what they used to be. He had, he said, gone into the matter and felt that once again starting could be construed as easy. Personally, I feel that coil ignition should be developed to a greater pitch of perfection. Given a battery that does not let one down—to which various users have been replying ‘the nickel iron battery'”— there is no reason at all why coil ignition should not be much better than a magneto for normal work. After all, the coil is stationary and does not rotate as is the case with a normal-type magneto, and it can be tucked away in a position where it is completely protected. As for the contact breaker, there is no difficulty in making this absolutely reliable, nor in providing a 2 to 1 gearing in the case of a four-stroke. That leaves the wiring—which should be substantial and armoured and have proper connections at its ends—and the dynamo, which we pretty well have to possess in any case. For myself, I cannot see why the coil set should not become more reliable than the magneto. Then we should have really fat sparks when we press the kick-starter pedal down—irrespective of the position of the ignition control.”

“THIS IS A TRUE ‘human story’ and is recounted by a Glasgow motor cyclist. He was returning home from his garage at about 2am after a night run. Then he saw something which quickened his steps—a police constable flashing his torch in a darkened shop-window and peering intently inside. Were some dangerous safe-breakers about to be apprehended? He hastened to the side of the constable, ready to help if need be. Crouching forms of burglars? No; the constable was playing the beam of his torch on an ‘International’ Norton in the window!”

“HERE is yet another striking testimony to the value of motor cycles. Maybe you read it in your paper earlier this week. A special service of motor cycle despatch riders ran between Buckingham Palace and Fort Belvedere, near Sunningdale, King Edward’s private residence, where he was spending the week-end. For such work motor cycles are invaluable, and it is good to find the King—the first monarch to fly—makes -use of another modern boon, the motor cycle.”

“DURING a recent week-end I made a trip of 26 miles each way under particularly bad, ie, icy, conditions. So bad, in fact, that many cyclists were ‘walking’ their machines down hills, and there were very few motorists out on either two or four wheels. In those few miles I met no fewer than three cars and four motor cycles bearing that large and significant red L, and two of the motor cyclists had pillion passengers at that. It is true they had the roads very much to themselves, but if those learners had the nerve to practise on roads which were, literally, sheets of ice, it speaks well for their determination, and even more for the modern motor cycle as a safe means of transport under all road conditions. I gave them plenty of room, but they all appeared to be blissfully contented with the conditions, and to be riding with the utmost confidence. May they all be passed off with flying colours when their exams. come.”

“ALL THE YEAR ROUND there is a steady influx of newcomers to the large army of seasoned motor cyclists. Some of them are proud owners of shining new models; others are equally proud of their somewhat dilapidated and very second-hand mounts. One and all would be in the seventh heaven of delight but for one thing—the Driving Test—that is unless they were in possession of a driving licence before April, 1934. Last year I went in for a driving test myself. Very probably I was one of the first motor cyclists to be tested, and, although I have been a rider for many years, I can honestly say that there is little to worry the tyro. However, there are three things that are essential. First, the rider must be absolutely at home with his machine. Secondly, the Highway Code must be learnt—but not parrotwise. The third requirement is common sense. What are the steps to be taken previous to going in for the test? Well, the beginner must first apply to the local licensing authority for a provisional driving licence. His nearest money-order office will provide the necessary form and the name and address of the licensing authority. After filling up the form he must take or send it to the licensing authority together with five shillings. The licence received, the tyro can ride his machine for a period not exceeding three months, during which time he can become fully accustomed to his machine and take his driving test. The red letter ‘L’ must, of course, be displayed on the front and back of the machine until the test is passed. A copy of the Highway Code will be issued with the licence and should be read carefully before the new rider takes to the road. When he has become confident the beginner should fill up a driving-test application form—obtainable from the licensing authority—and send it, together with a fee of 7s 6d, to the nearest authority controlling his area. For this purpose a list of driving test authorities printed on the back of the application form. In due course he will hear from the authority, fixing an appointment with an examiner—in my case I was offered several alternative times to suit my convenience. Be at the appointed place in plenty of time, and if there is an office there walk straight in—don’t expect the examiner to be waiting for you beside the kerb. If the applicant is ‘ploughed’ in the examination, and the probationary period of three months has elapsed, a further provisional licence (cost 5s) must be taken out, for a month has to elapse before the driving test can be taken again. Remember, there is nothing to worry about in the test, provided it is tackled seriously and in the right spirit. When I undertook my test I was on a solo machine. This is what happened. First, my driving licence was inspected. Next I was asked to sign my name in the examiner’s book, so that the signature could be checked with that in my driving licence. Then the insurance certificate was perused. I was next tackled on the subject of the Highway Code. My examination, if you could call it that, was carried out in the manner of an ordinary conversation—a method calculated to give confidence. Now the questions were obviously designed to see if I had not only learnt the Highway Code but, more important, knew its application. For newcomers I cannot stress this point too much, and so that they may he guided I am roughing out a short list of questions of the type which they will very likely be asked. Just see if you can answer them correctly: (1) What is the number of driving signals that a motor cyclist should give? Give also a brief description of them. (2) What do you understand by the traffic lights? What is their sequence? (3) When can you turn left against a red traffic light? (4) What steps would you take to turn into a road on the right? (5) When would you overtake on the left? (6) What do you understand by traffic lanes and how would you drive along a road so marked? (7) What is the principal law with regard to pedestrian crossings? (8) If at a cross-roads a policeman fails to notice you, what should you do? (9) What is the High-way Code and what is it for? When answering an examiner it is always advisable to show a genuine interest in the answers. Attempt if possible to enlarge on the points raised. It will help to convince the examiner that not only do you know the Highway Code, but that you also understand its application. In my particular case the examiner questioned me before asking me to perform a few manoeuvres on the road. Then, having proved I knew my Highway Code, I was requested to proceed to a certain road. There I was asked to ride down it, turn round at the end and come back. Although the road was free from other traffic, I was told to regard it as a busy thoroughfare. In a case such as this the learner must take the greatest pains to give all the necessary signals. It might even be to his advantage to pull into the side of the road, stop, and look round before turning round. His chances will also be considerably enhanced if he keeps his feet on the footrests whenever he is in motion. Likewise, riders using machines with a hand gear control would be well advised to refrain from looking down at the gate. After all, it is fairly easy for an examiner to assess the ability of a rider simply by watching him start off and stop. Obviously if he wobbles into the centre of the road, as some beginners are apt to do, he will lose one or two marks. He most be able to use his clutch in conjunction with his brakes, and for this purpose applicants are frequently asked to stop and restart on a hill without slipping backwards or leaping forwards. Sometimes a pre-arranged signal is given in order to see how the motor cyclist can pull up in an emergency. In this instance I was asked to pull up immediately my examiner raised an arm. In the case of passenger machines the examiner frequently accompanies the driver, who might, in these circumstances, be called upon to stop when he least expected it. In the case of a three-wheeler fitted with a reverse, the examiner would in all probability request the driver to turn round, using a side turning for the purpose…Really, the whole test is very simple and free from any ‘catches’, but it must not be taken lightly. It is not a test of skill. It merely shows the examiner that you are a safe and proper person to be in charge of a motor vehicle, and that you are capable of coping with the traffic conditions of to-day. I can only reiterate that there is nothing to cause the beginner any worry. If he should have the misfortune to fail—and I can assure him there is very little chance of this—he can console himself that the errors he made were in a test and were not the real thing, in which case the results might have been very different! The following are the answers to the questions on the Highway Code: (1) The number of driving signals is four. To slow down or stop, the right arm should be extended sideways and moved up and down from the shoulder, keeping the wrist loose and the palm facing downwards. To turn to the right, the right arm should be rigidly extended to the right, with the palm facing forwards. To turn to the left, the right arm should be extended and rotated from the shoulder in an anti-clockwise direction. To indicate that other vehicles can overtake, the right arm should be extended below the level of the shoulder and moved backwards and forwards. In this connection it is well to remember that the onus rests on the driver of the overtaking vehicle. (NB—All signals must be given with the right hand.) (2) The sequence and significance of the traffic lights are as follows: Red means stop and wait behind the line on the road. Red and Amber still mean stop, but traffic should prepare to go. Green means proceed, but with • particular caution if turning to left or right. Amber means stop at the line, unless it has already been passed or you are so close that to pull up might cause an accident. (3) It is permissible to filter, ie, turn left against the red signal, when a green arrow is shown at the same time as the red signal; traffic can then proceed only in the direction indicated by the arrow. (4) To turn to the right, the right arm should be extended to the right. Filter towards the crown of the road well before the turning. (5) Overtake only on the right, except when a driver in front has indicated his intention to turn right. This a rule does not necessarily apply in one-way streets. (6) In the majority of cases where traffic lanes are employed, the road is divided down its length into three equal pacts by two white lines. The centre lane should be avoided except when overtaking another vehicle. Otherwise the left-hand lane only should be used. (7) Where a pedestrian crossing is not controlled by police or light signals, drivers of vehicles must give way to any pedestrian actually on a crossing. (8) Wait until he does notice the vehicle. On no account must the horn be sounded, except in the case of emergency, when a vehicle is stationary. (9) The Highway Code is a standard of conduct for British roads. Its provisions are intended to make the roads safer for all classes of road user.”—Ambleside

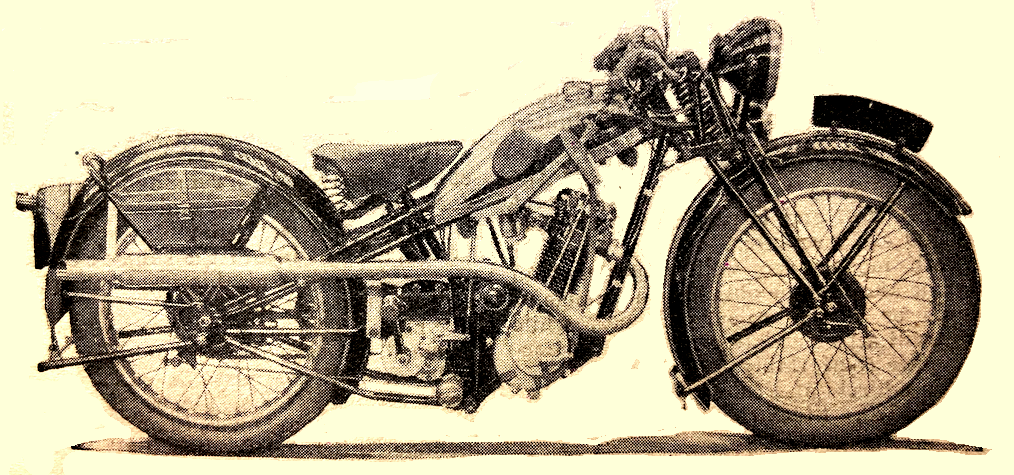

“MUCH HAS BEEN WRITTEN lately on the subject of mudguarding. Certain manufacturers have found that narrow front mudguards are a sine qua non; their customers will not accept wide and really effective valanced guards—they do not look sufficiently sporting! From this it might be assumed that protection from mud and dirt and sporting lines are as poles apart. That this need not be so is proved by at least one of the 1936 models. The enclosure and shielding in this case, instead of detracting from the lines of the machine, improve them considerably. It is not a big step to visualise sports mounts in which the shields blend to give a streamline effect—that fulfil the dual function of making the machines to which they are fitted look still more sporting and at the mine time affording almost complete protection to the rider. No one thought that forerunner of the various foreign transverse twins, the old 398cc ABC, in any way unsporting. Quite the reverse in fact, yet it was a motor cycle that could be ridden anywhere without the rider having to don waders.”—Ixion

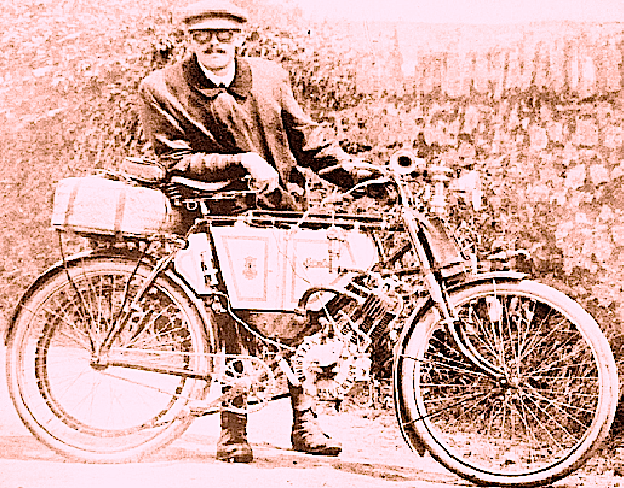

“JOE VAN HOOYDONK, who died the other week, was a great man in the early days, and embodied Minerva engines in bicycles bristling with all sorts of practical little gadgets. He first achieved real fame as the apostle of the tricar, with his Phoenix Trimo. How he used to grin at meets of the MCC, when the rest of us sprinted along the road on a hot day in our leathers, attempting to get our engines firing, whilst he coolly extracted a starting handle from his tool-box, wound up the engine of his Trimo, and glided away on the clutch! So in revenge we pinched his handle, and poor Joe had to sweat and strain to push off. He once teased me to death at the end of a Land’s End-John o’ Groats trial in which his Trimo scored a non-stop gold, and I scraped up a gold by the skin of my teeth, reaching Groats at the last possible second with my bike falling to bits. I dumped it in the stable at Groats, and begged a lift back to Thurso in a car. Half way to Thurso my car was sitting on the Trimo’s tail when the Trimo’s back wheels suddenly folded outwards as the rear axle snapped. Joe advertised that gold medal for months afterwards, and I used to carry a copy of the ad in my vest pocket, and show it to him whenever we met.”—Ixion

“T0 LET YOU INTO A SECRET, I don’t intellectually approve of anything for which Hore-Belisha is famous. I hae ma doots whether the 30 per has reduced casualties. I note that except when a cop is around motors ignore pedestrian crossings, and pedestrians expect motors to ignore them. But he has produced a genuine miracle in effecting a substantial reduction in road deaths and injuries for 1935, when previous tendencies, plus the increased traffic, threatened a heavy increase. I don’t know how he has accomplished this. He probably thinks that speed limits and pedestrian crossings and such like are the main factors. I think the decrease is mainly due to (a) educating, and (b) frightening road users. Nobody can prove which of us is right, but anyhow, hats off to the man who saved more lives and limbs in 1935 than many hospitals! Incidentally, do you know that although until 1935 the total road casualties were ‘increasing’, yet the fatal accidents blamed by the police on to motorists have been ‘less’ for four years than the 1930 figures? Who, then, was to blame for the rise in the totals of those four years? Cyclists? Hush—Mr Stancer* may be listening. Pedestrians? Hush—the Pedestrians’ Association will annihilate you at sight.. To put sarcasm on one side, the police deal only with the motor as a ‘direct’ cause of smashes. It can also act as an ‘indirect’ cause. For instance : Aunt Maria crosses the High Street avec parcels. In 1906 motors were few, and she stalked across. In 1936 motors form an almost continuous stream, and Aunt Maria hesitates and scutters. She pirouettes in front of a motor bus…The police hold the motor bus not guilty. So it is—in a direct sense; but if there had not been such a lot of motors in the High Street Aunt Maria would still be alive.”—Ixion

* George Stancer OBE was a racing cyclist who became editor of Cycling magazine and president of the Cyclists Touring Club.

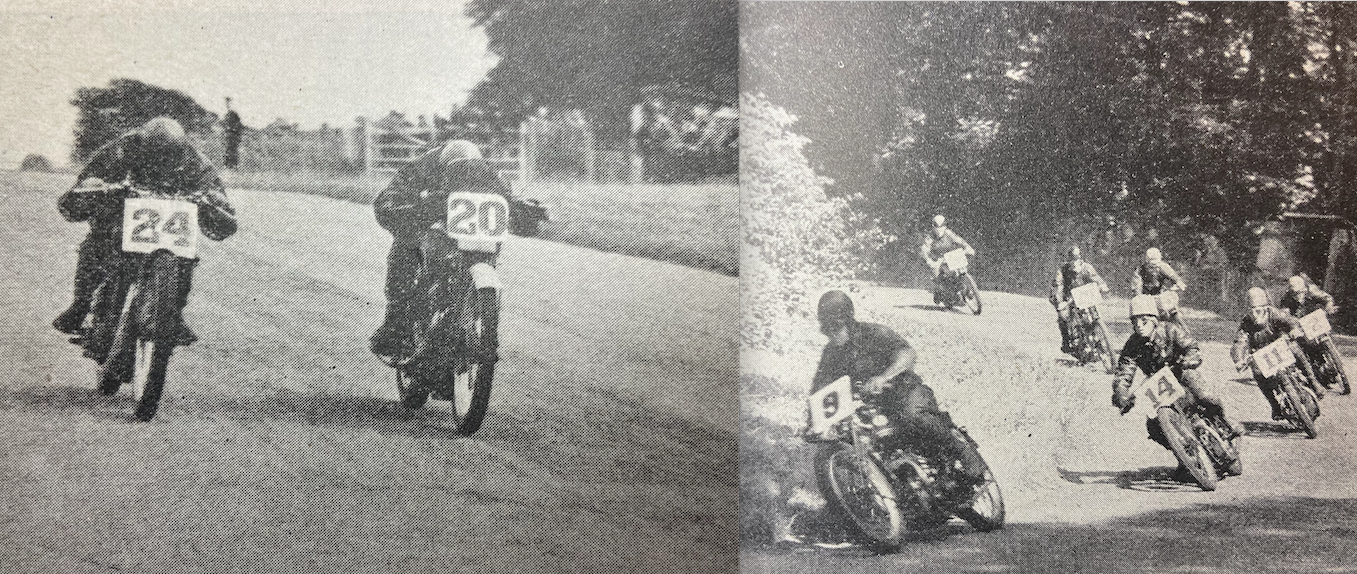

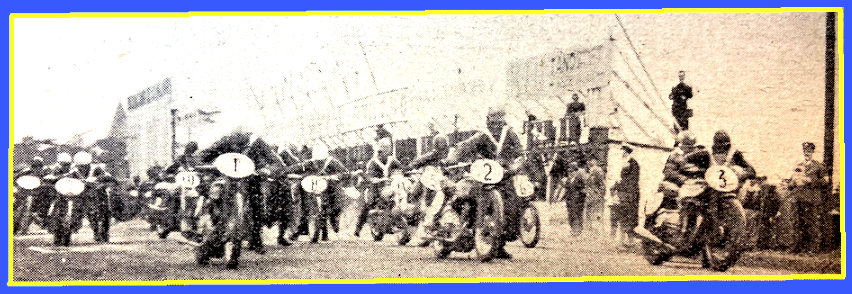

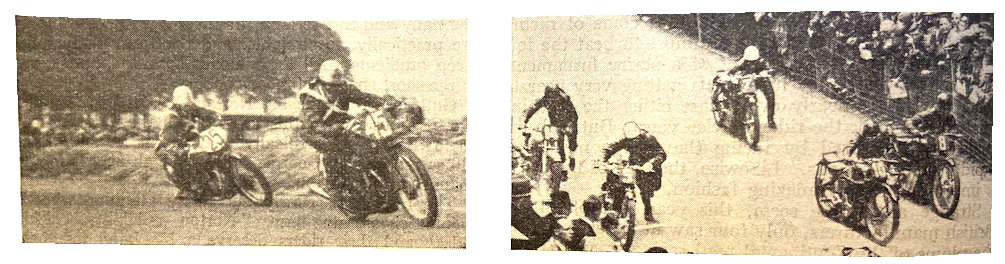

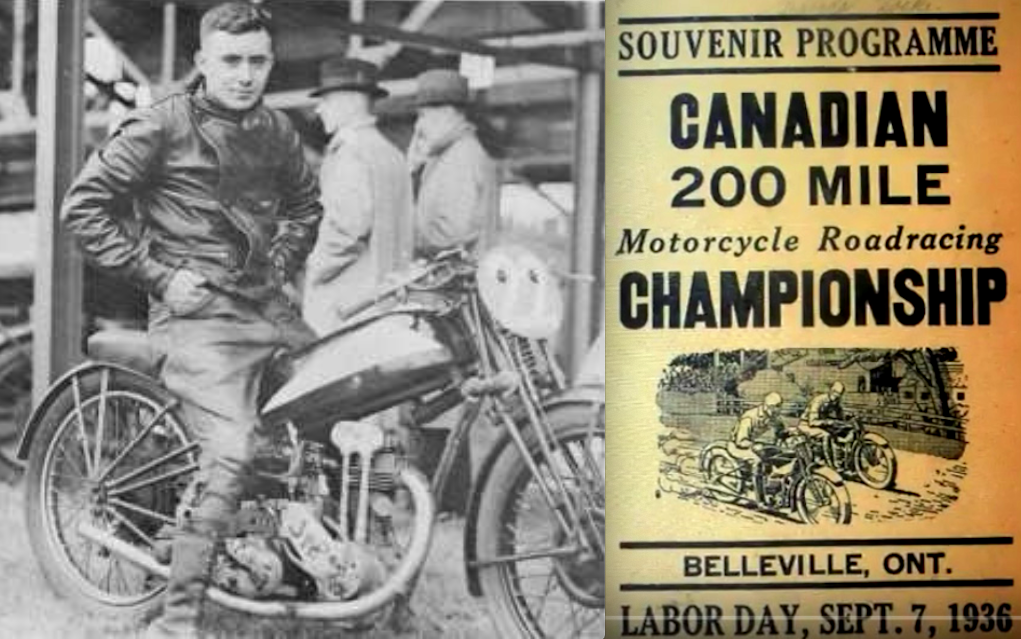

“A CROWD, OFFICIALLY estimated at 60,000, witnessed the first Port Elizabeth (South Africa) ‘200’ road race field recently. The event was won by HJ Brook (348cc Velocette) at an average speed of 75.5mph. There were 26 starters, including J Sarkis and JC Galway—the latter the winner of the last South African TT.”

“OVER 1,000 PEOPLE witnessed the 1935 Grass-track Championships of Victoria (Australia), which were held under ideal conditions on the Warragul racecourse, about 65 miles from Melbourne. In the big event of the day Reg. Hay (Coventry-Eagle), the veteran Tasmanian rider, retained his title of solo champion. Hay rode a hectic race to win by four seconds from Gordon Wilson (346AJS). Les Darby was third, three seconds behind. In the sidecar events Bill Longley (Excelsior-JAP) won both the 500cc championship and the All-Powers event breaking the class record by 11seconds in the former event.”

“FOUR THOUSAND GAS street lamps in the Borough of Camberwell, London, are to be superseded by electric lamps.”

“THERE ARE 178,507 miles of public highway on Great Britain. About 75% of the total—133,229 miles—is in England; 18,607 miles (about 10%) in Wales; and 26,411 miles (about 15% in Scotland. Britain has gained 7,016 miles of first-class roads in the past 13 years. Britain now has 26,779 miles of Class I main traffic arteries and 16,837 miles of Class II less important traffic routes—a total of 43,616 miles. In 1921 the total length of classified roads was only 36,000 miles.”

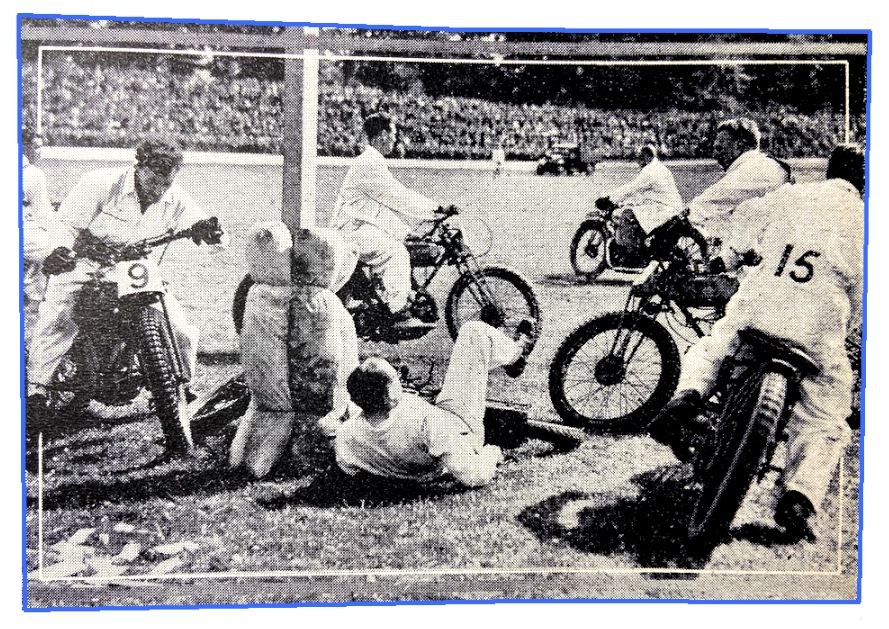

“MOTOR CYCLE BASEBALL, a new game in the United Stets, is said to be very popular with spectators.”

“YOUR CORRESPONDENT ‘ARDUPP’ complains of poor mpg, and requires tips in this respect. I am of the opinion that he has been riding a very bad machine, for there is nothing in obtaining over 100mpg with a two-stroke engine. Perhaps any own experience will support this. I have two machines; one a 1929 196cc Francis-Barnett-Villiers, which has been on the road continuously for the last six years and still gives me 125-130mpg. It is a perfectly standard machine in every way, and, beyond the usual running adjustments, has not been overhauled in any way. The other is a 1923 799cc twin-cylinder with heavy adult two-seater sidecar; this outfit is used throughout the summer months for week-end jaunts and holidays. It is in perfect mechanical condition and often takes four up on long runs. It has the usual de-coking every spring, but nothing else (for it does not require anything else); this outfit regularly gives .an average of 68-70mpg carrying four adults. Perhaps your correspondent will think this is an exaggeration, but the agent for AJS and Francis-Barnett machines in Chester will bear out what my machines do.

RHG Hankinson, Chester.

I WAS INTERESTED IN A letter from ‘Ardupp’ regarding petrol consumption. From my own somewhat small experience I can state quite definitely that it is necessary to coast down hills, and also one must not exceed 30mph for any distance if a decrease in petrol consumption is aimed at. This is obviously true for all capacities and makes of machine. I have a 150cc overhead-valve BSA which is 18 months old and has done 14,500 miles. I use it for business daily, and regularly get a fuel consumption of 150mpg. The road I use is fairly curly and awkward, and 30mph is rarely attained anywhere en route.

Ralph W Smart, Carshalton, Surrey.

“I HAVE READ with interest the letter in the ‘Blue ‘Un’ from ‘Ardupp’ concerning petrol consumption with the two-stroke he owned. I think his 50mpg was very poor. I own a 596cc two-stroke fitted with a two-seater sidecar, and my mileage is in the region of 70mpg. ‘Ardupp’ won’t catch me coasting down hills, and if he gets behind me he won’t find me doing a steady 30mp. I think if your correspondent had looked after his two-stroke, both inside and out, he would have found it much more economical.

‘Sludge’, March, Cambs.”

“FROM Mr AE Cooke, organiser of tomorrow night’s Combined Motor Clubs’ Charity Ball at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, I learn that the attendance will exceed 2,500, which I think you will agree is a staggering figure. Sir Malcolm Campbell has promised to attend, while Elsie and Doris Waters are to perform on the stage. There will be cabaret shows at 11.15pm and 12.15am. For the benefit of those who might wish to get in touch with him, Mr. Cooke’s address is 91, College Road, Kensal Rise, London, NW10.”

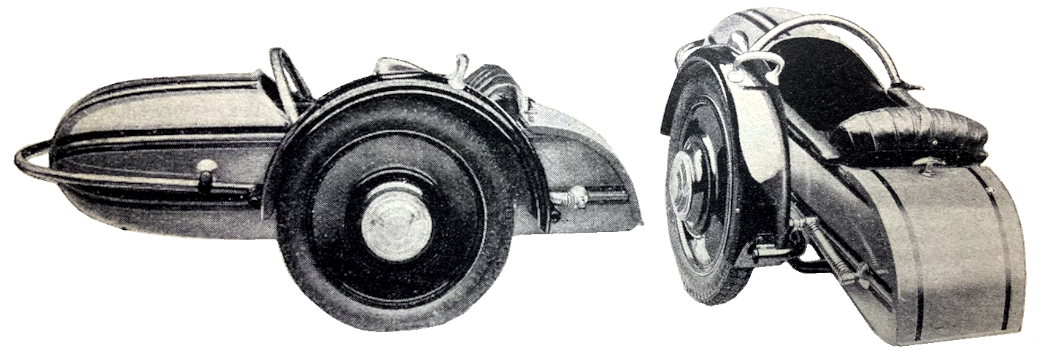

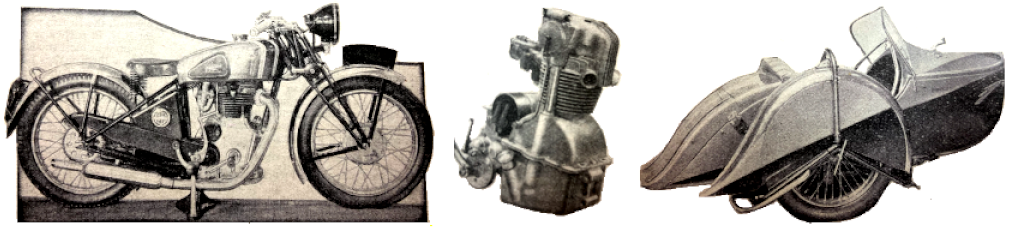

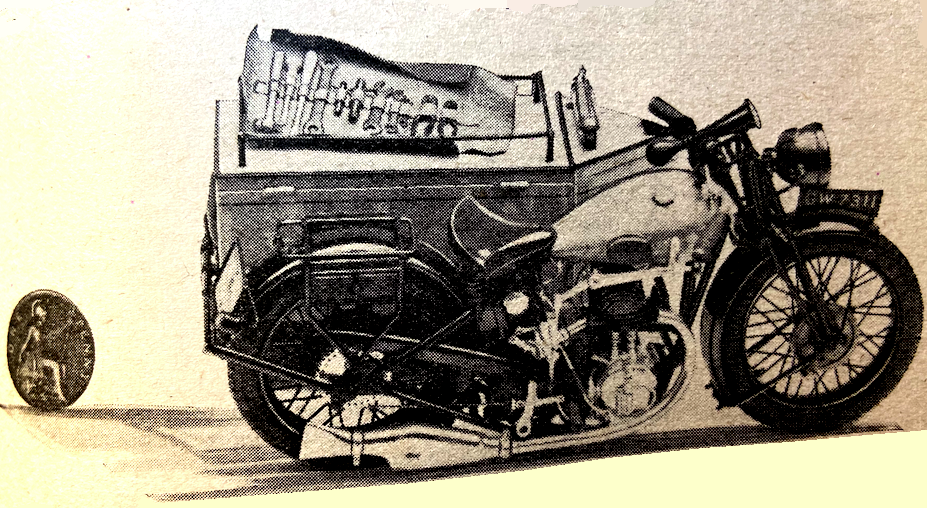

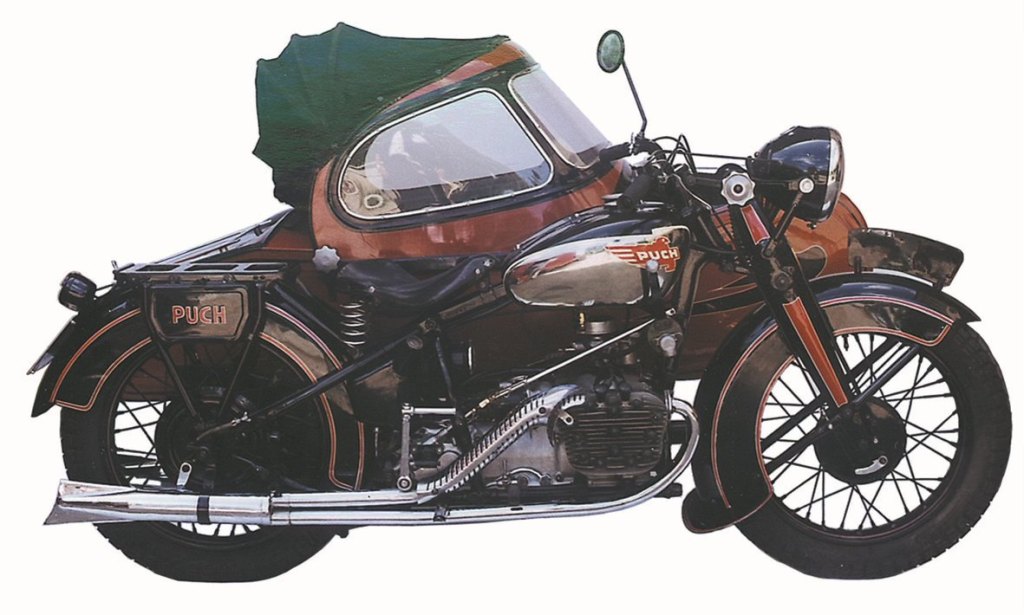

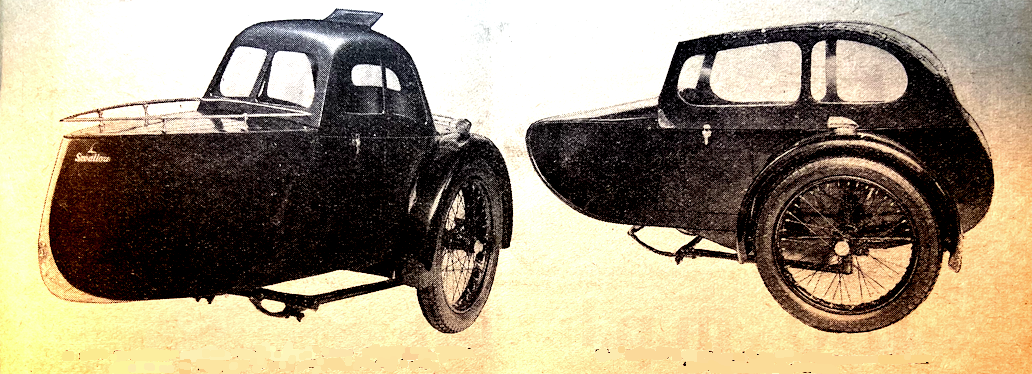

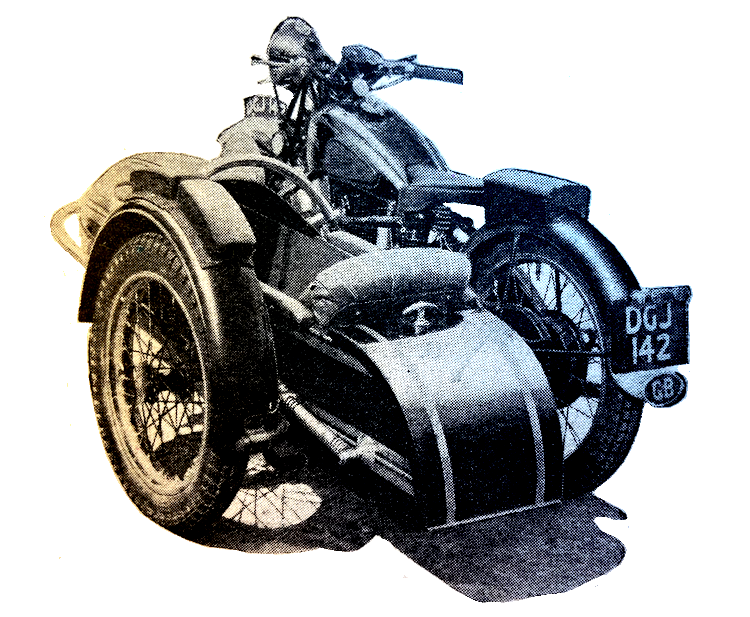

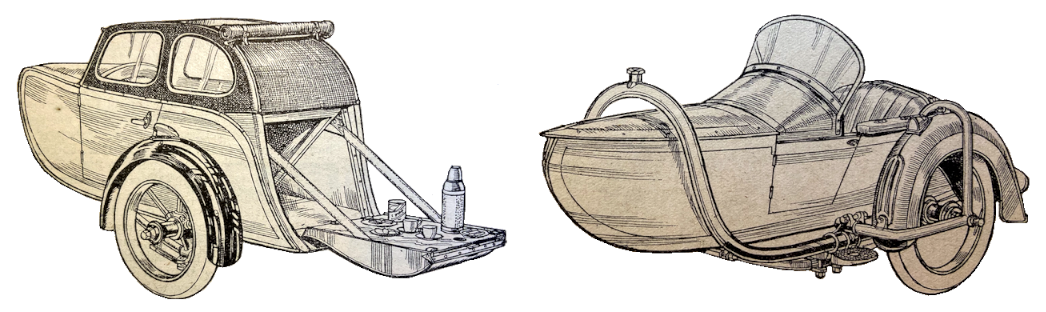

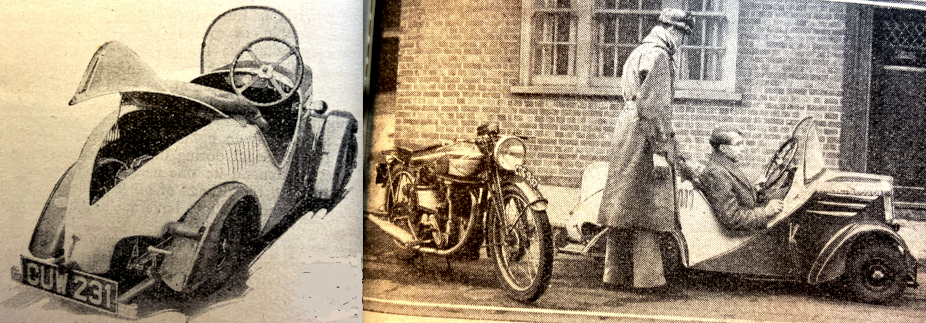

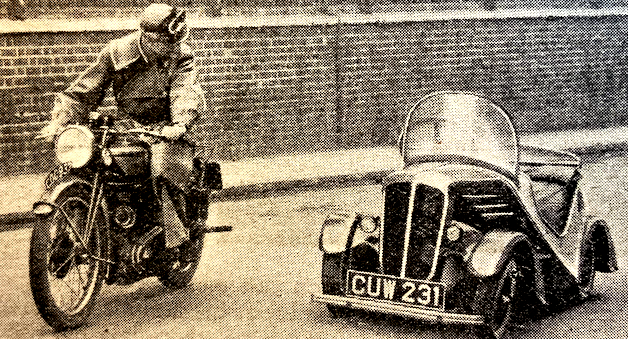

“DURING THE PAST FEW years there has been a tendency on the part of German sidecar designers to break away from the more orthodox style as regards both the bodywork and chassis. Different methods of production have resulted in sturdy, accurately-built sidecars, suited for hard work over the by-roads of the Continent. Now comes the news that one German make, the Steib, is to appear in England. For the time being only two models will be marketed. Both will be of the sports type, differing only as regards the bodywork. To British eyes the Steib sidecar sparkles with unusual features, the most interesting of which concern the chassis. The main chassis member consists of a single tube in the form of a long fiat U, with the open end at the back. Linking the open end is a shallow U-shaped bar, which is welded at each end. The wheel is carried on a long spindle which is clamped to the main chassis member. It is worthy of note that all parts of the Steib chassis, except the cross-bar, are bolted into position and not welded or brazed. An unusual method of suspension is employed for the all-steel sidecar body. The forward end of the body is attached on each side to lugs rigidly mounted on the chassis. The sidecar is, however, free to pivot on these lugs. At the rear are two horizontally placed tension springs, one on each side of the body. The forward ends of the springs are attached to adjustable lugs situated at the ends of the main frame member, and the other ends of the springs are connected to lugs at the rear of the sidecar body. In view of the part played by the side-car body in its own suspension, it is interesting to note that there is no actual body framework. Throughout the bodywork a method of skin-stressing is used in conjunction with steel panelling. The nose of the body is built-up with pressed-steel panels, spot-welded together. The lugs at the four points of suspension are backed with large-diameter steel plates, which distribute the stresses over a wide area. The bodies are well upholstered, with spring seats and backrests, while wide footrests are provided. Both models available in England have quickly detachable wheels with a tommy-nut fixing. The wheels run on large-diameter roller races which come away with the wheel when the latter is removed. The Standard Sports model is fitted with a clip-on disc wheel, whereas on the Luxury Sports the wheel is chromium-plated and the disc is an extra. The Luxury Sports model has a roomy locker, the lid of which hinges backwards. and when open is supported by two chains sheathed in rubber. Incidentally, the locker lid is of particularly sturdy construction, having an inner panel of greater radios than the outer. The two panels are spot-welded together at the top and bottom, while in the centre are two steel strips, which form stiffening ribs. The Standard Sports model also has a locker, but in this case access is obtained by hinging the backrest forward. These interesting sidecars are being handled by the sole concessionaires for Great Britain, Pride & Clarke, 158-160, Stockwell Road, London, SW9. The price of the Standard Sports model in this country is £20 10s., while that of the Luxury Sports model is £21 10s.”

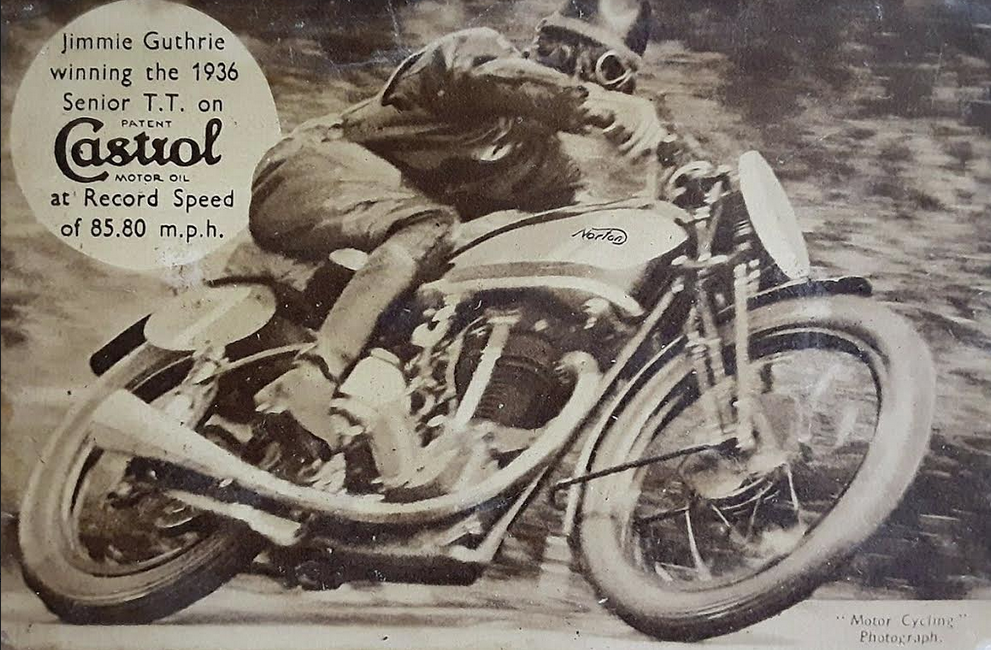

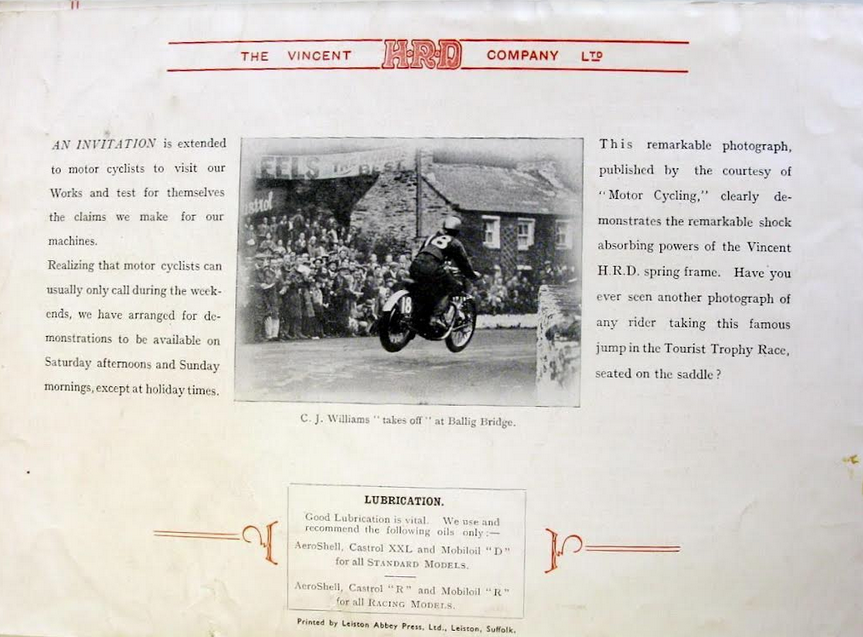

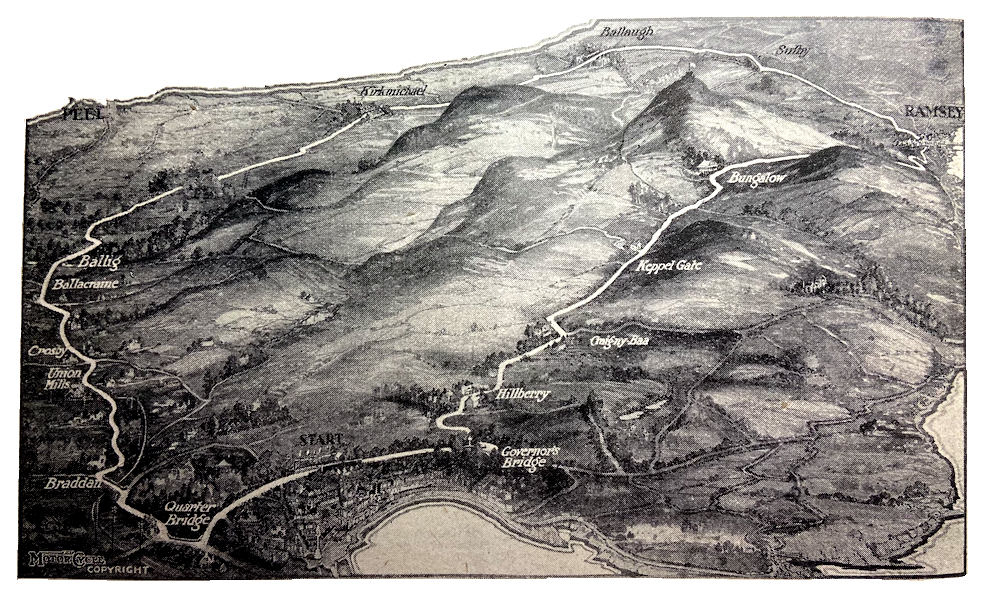

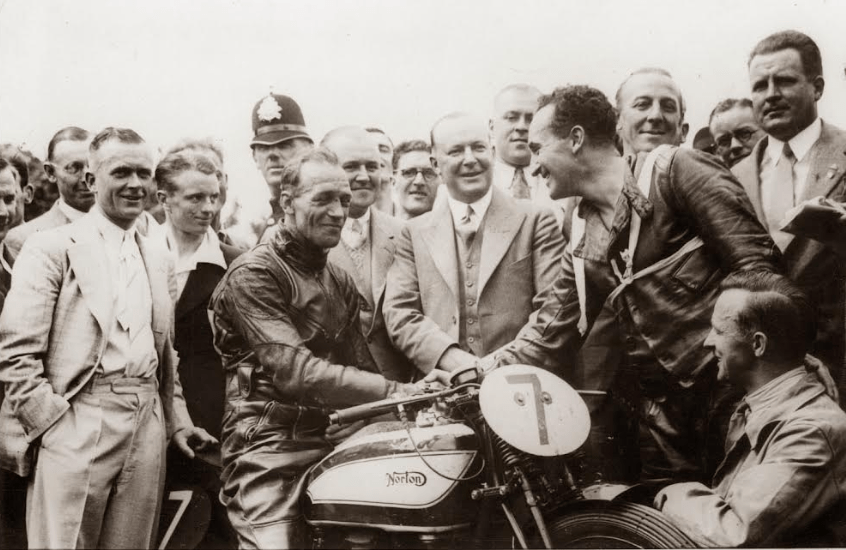

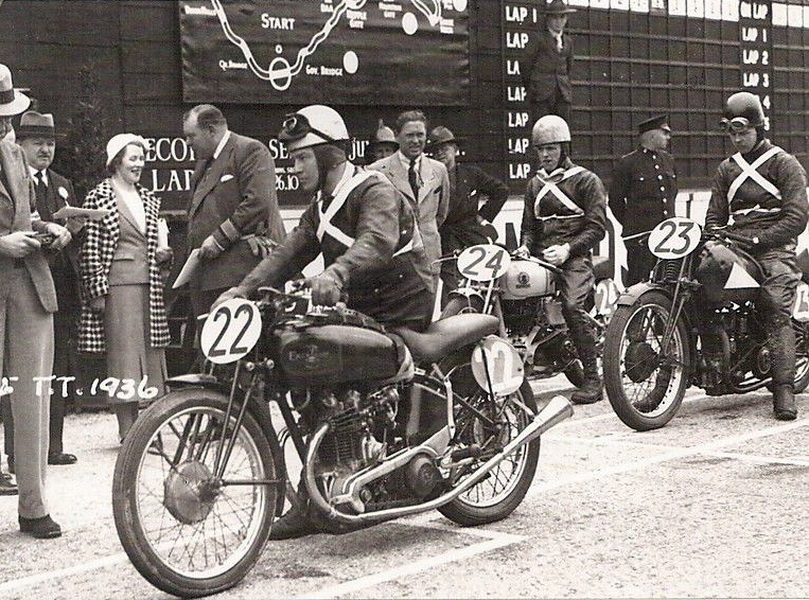

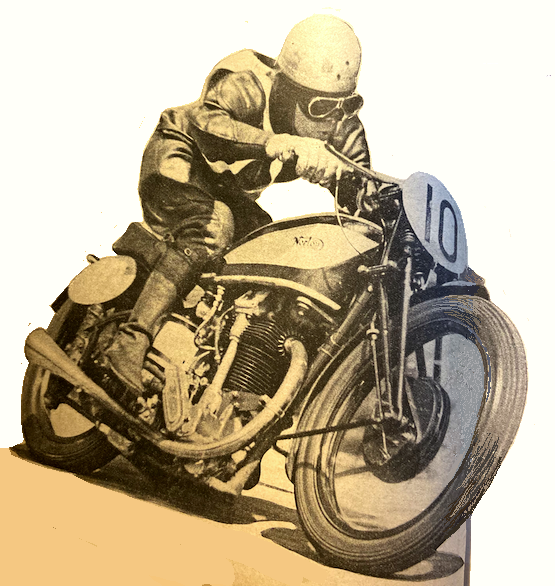

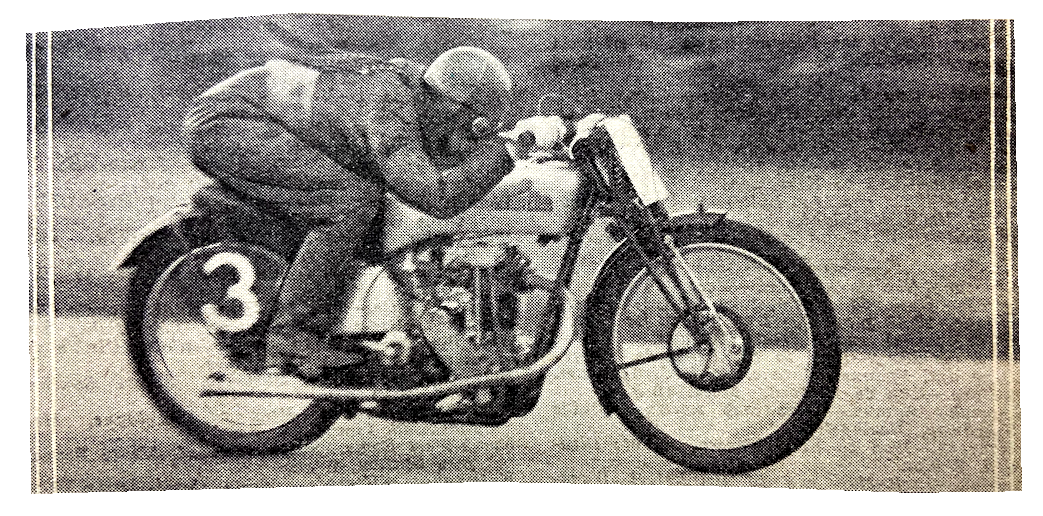

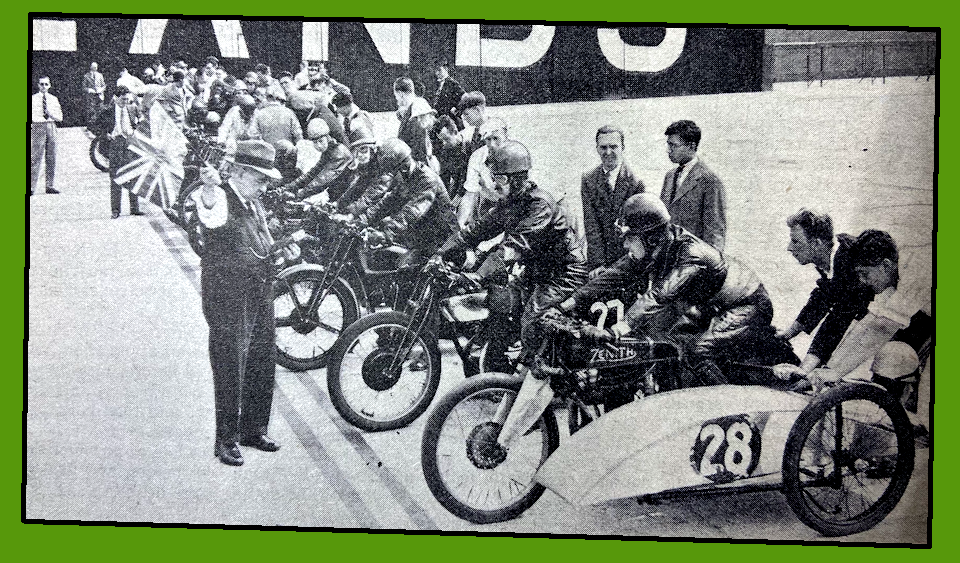

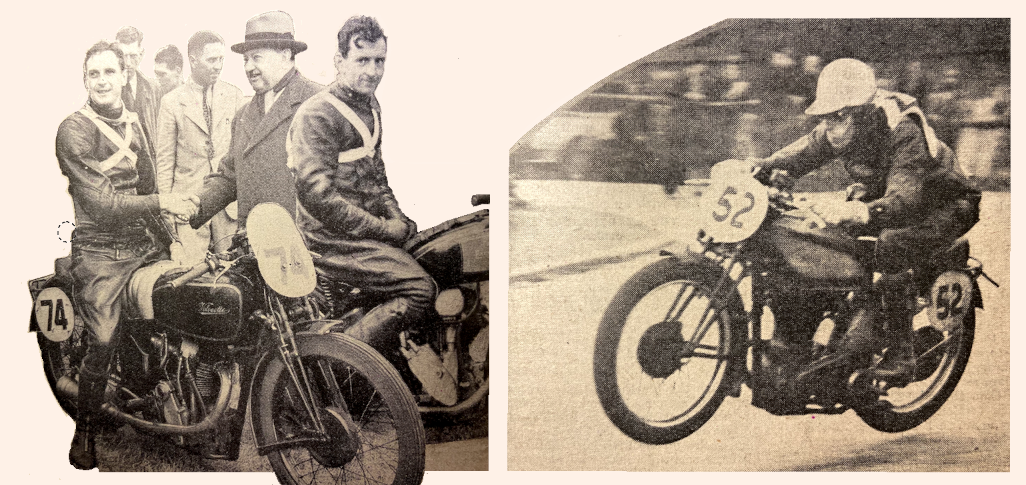

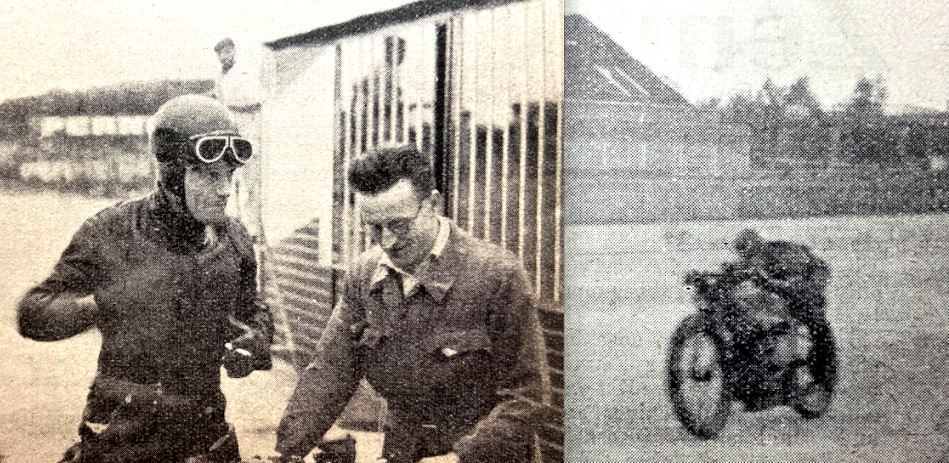

WITH MUSSOLINI’S FASCISTI attacking medieval Abyssinia the British government did not want Moto Guzzis anywhere near the Island so Stanley Woods rode for Velocette in the Junior and Senior races. Having become used to the spring-frame Guzzis he must have appreciated Velo’s innovative air sprung, hydraulically damped ‘pivoting fork’ (swinging arm) frame. Not for the first time, here’s a contemporaneous report from the man on the spot, TT Special editor (and TT rider and staffer for the Green ‘Un) Geoff Davison [the notes in italics are mine—Ed]. “Right from the beginning of the race the 1936 Senior was a Guthrie-Woods duel, and Jim made no mistake about it this time. He led Stanley from the very beginning of the race by 19sec on the first lap, 27 on the second lap, 23 on the third lap and 18 on the fourth. On the fifth lap there were 25 seconds between them, which Stanley had reduced to 22 by the end of the sixth. During that lap both of them broke the record, Guthrie with a lap in 26min 5sec and Stanley with one in 26-2. In the Grandstand we were in a fever of excitement. In 1935 Jim had led Stanley by 26sec at the end of the sixth lap—and Stanley had won. This year Jim had a 22sec lead—was history to repeat itself? Jim made sure that it didn’t. His last lap in 26-22 was not his fastest, but nor was Stanley’s, which was four seconds better than Jim’s but had nothing of the 1935 fireworks in it. Jim won by 18 seconds and so wiped out his defeat of the year before. Stanley, however, had put up the record lap,

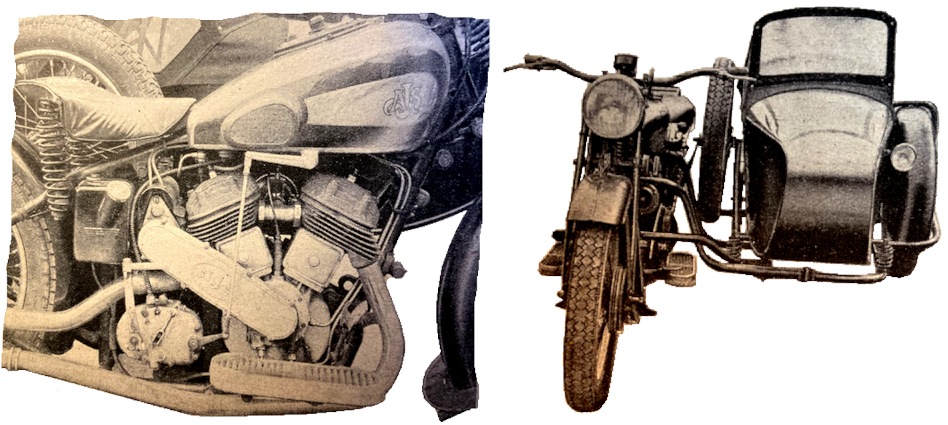

Norton won the team prize—so all was square. [Harold Daniell and George Rowley were out on the new AJS ohc V4s complete with superchargers but both retired with mechanical problems.] There had been no minor ‘gefuffle’ in the Junior race held on the previous Monday. Stanley Woods retired early on [his cammy Velo had engine troubles at Sulby] and Jim Guthrie led the first lap, closely pursued by a newcomer to the Norton team, Freddie Frith [who was recruited after winning the 1935 Manx GP]. At the end of the fifth lap Guthrie was delayed at Hilberry [to replace his drive chain]. He had taken 31min for the lap, as against the 28min odd of his others, and had dropped to third place. He carried on, however, and picked up to second on the sixth lap. Then came news that after his stop at Hilberry he had received the assistance of a marshal in re-starting his machine. It was announced that he was to be excluded from taking further part in the race and orders were sent out by telephone for him to be stopped at Ramsey. Immediately he was stopped he got on to the telephone to the Start and was told the position. He then re-mounted and carried on at speed to the end of the race, finishing, so far as I remember, fifth on time, although this was not officially recorded. Guthrie and the Norton firm at once put in a protest. This was upheld, the following announcement being issued during the evening: ‘The stewards have considered a protest from Norton Motors Limited on the exclusion of No 19, J Guthrie. After a careful sifting of the evidence, and from voluntary reports by independent witnesses, together with a personal inspection of the ground, they are now of opinion that they were originally misinformed. The protest is therefore allowed. The official placings cannot be disturbed, but in the circumstances they recommend that the value of the prize attaching to the second place, which, in all probability No 19 would have occupied had he not been flagged off the course, be granted to the entrant. No l9 will be recorded as a finisher, and Messrs Norton Motors Ltd win the Manufacturers’ Team Prize.’ The whole affair, was, of course, extremely unfortunate, for, as the stewards had agreed, Guthrie would probably have run

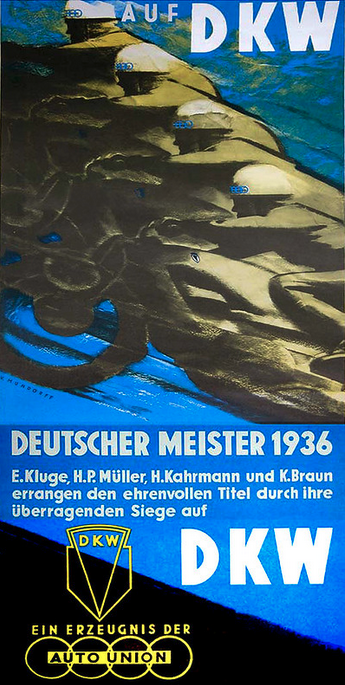

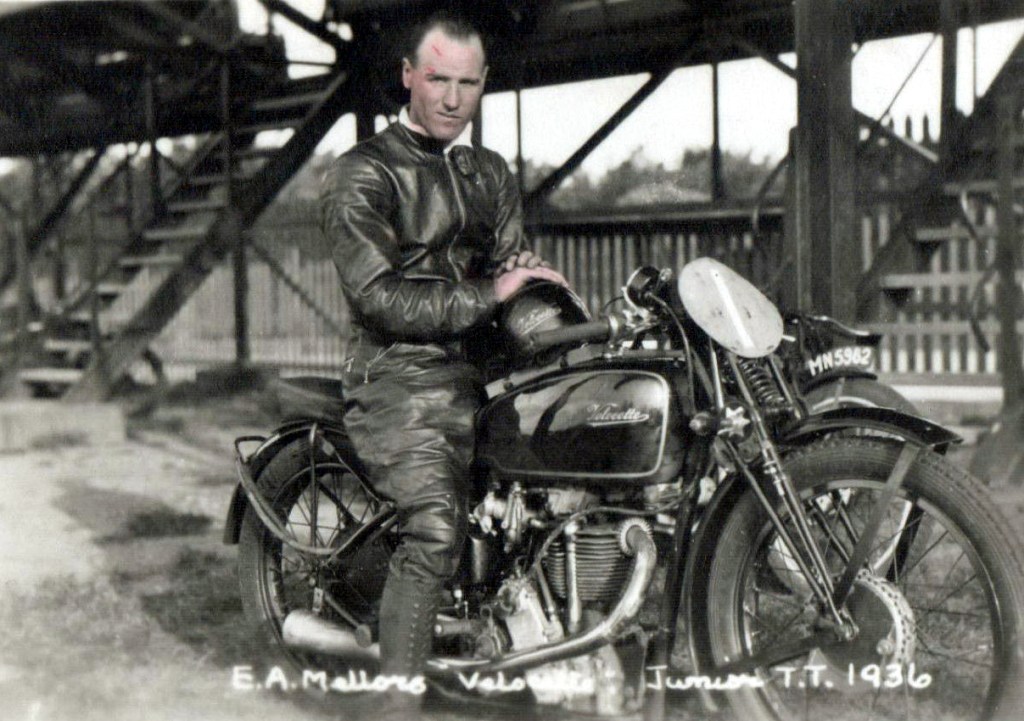

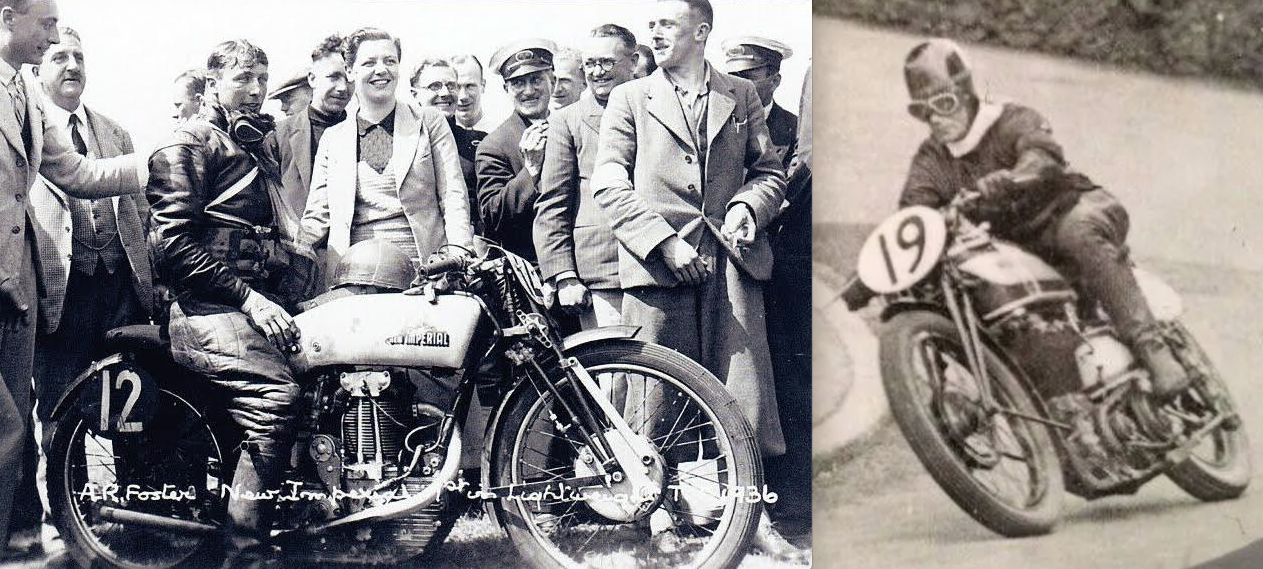

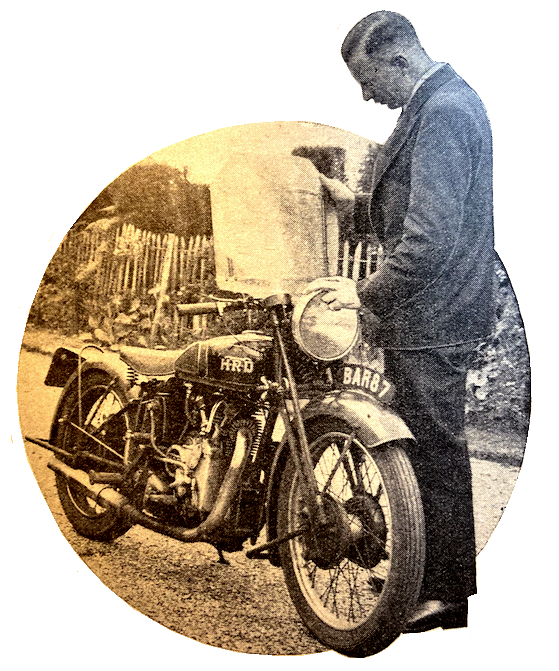

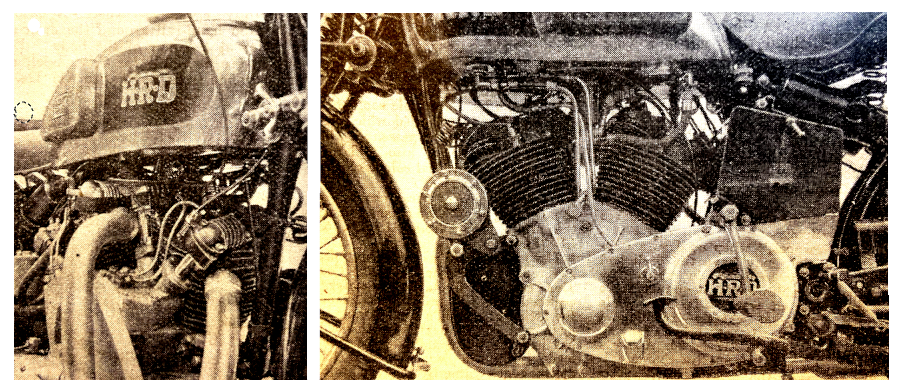

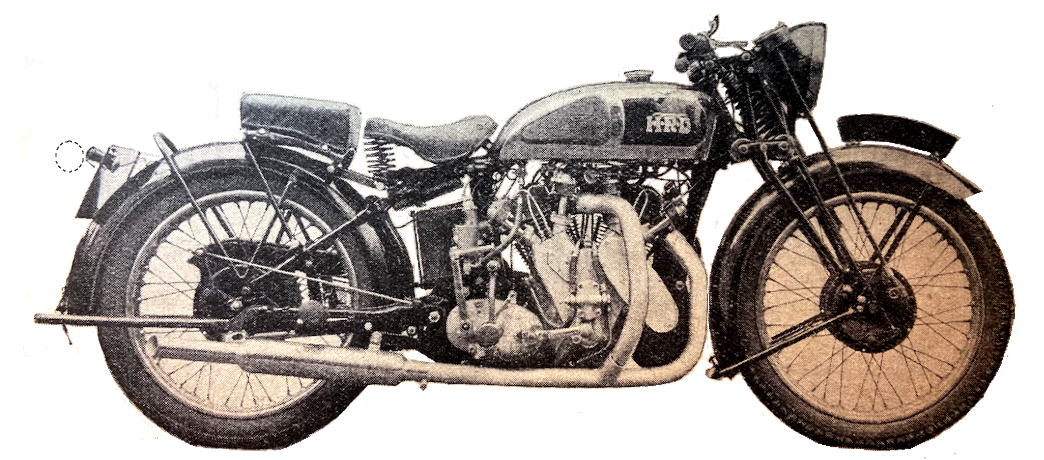

second to Freddie Frith, with Crasher White third. This would have given Norton a 1-2-3 victory. As it was, they had to be content with first, second and team prize. The results of the Lightweight race [delayed for a day because of mist and fog on the mountain] cheered us up a bit. Stanley Woods on the German [three-cylinder supercharged] DKW led on the first two laps, but in the third Lap Bob Foster (New Imperial) overtook him, only to lose his place on the fourth lap. In the fifth lap the positions were the same, with Stanley 14sec ahead. On the sixth lap Bob Foster overtook the Irish-German combination again and led by 35sec. Then Stanley retired near The Bungalow on the last lap [with an ignition problem] and Bob regained the Lightweight Trophy for Britain His speed of 74.28m.p.h. was nearly 3mph faster than that of Stanley’s Guzzi the previous year.” Foster owed his win to a gamble: company founder and MD Norman Downs cancelled a scheduled pitstop to take on oil. The New Imp had a notorious thirst for oil; Foster didn’t call his mount the Flying Pig Trough for nothing. It was the last TT win by a British 250 and the last solo TT win by an ohv engine. Foster, by the way, was a newlywed; his bride’s reaction to her TT honeymoon destination is not recorded. Tyrell Smith, riding for Excelsior, was runner-up and Woods German DKW team-mate Geiss was 3rd—if Woods’ Deek had lasted a few miles longer…RESULTS: Senior: 1, Jimmie Guthrie (Norton), 85.8mph; 2, Stanley Woods (Velocette); 3, Freddie Frith (Norton); 4, John H White (Norton); 5, Noel Pope (Norton); 6, C Goldberg (Velocette); 7, WT Tiffen Jnr (Velocette); 8, Jock West (Vincent-HRD); 9, JC Galway (Norton); 10, Bill Beevers (Norton). Junior: 1, Freddie Frith (Norton) 80.14mph; 2, John H White (Norton); 3, Ted Mellors (Velocette); 4, Ernie Thomas (Velocette); 5, Jimmie Guthrie (Norton); 6, Oskar Steinbach (NSU); 7, Heiner Fleischmann (NSU); 8 D Hall (Norton); 9, Harold Daniell (AJS); 10, George Rowley (AJS). Lightweight: 1, Bob Foster (New Imperial) 74.28mph; 2, HG Tyrell Smith (Excelsior); 3, Arthur Geiss (DKW); 4, DS Fairweather (Cotton); 5, Charlie Manders (Excelsior); 6, EW Corfield (Excelsior); 7, Harold Hartley (Rudge); 8, Svend Aage Sørensen (Excelsior); 9, HC Lamacraft (Excelsior); 10, JC Galway (Excelsior). Competitors came from Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, the USA, New Zealand and South Africa.

“I WONDER HOW MANY people watching this year’s Lightweight TT realised that but for Snaefell the DKW would probably have won. This is only a speculation, but we all know that the DKW is practically invincible for sheer speed in 250cc events on the fiat Continental courses, where it usually scores a non-stop win. In the Island it fell far short of achieving even one ‘non-stop’ with three entries; and, if I am correctly informed, the main reason for stops was plugs. The probable cause of this unparalleled plug trouble is to be sought in the high temperatures generated by racing up a high mountain, with a minimum head draught and high rpm, on indirect gears. The No 8 hats must decide whether the technical value of a mountain section in a road race (plus the concomitant stresses) is a first-class asset or not. As we all know, there is a movement afoot to establish a new, shorter, and flatter course. If that movement succeeds, we shall have a tough job to defeat the DKW in 1937. ‘Died on the Mountain’ must be its epitaph for last TT week.”—Ixion

“HITHERTO there has been some competition for the honour of being ranked as an ACU steward in the Island. Stewards. are big pots. They wear gorgeous brassards. They have the entrée everywhere. They get the first low-down on everything. But 1936 I was an unlucky year for them. Having made that original bloomer of excluding Guthrie, they wriggled and wobbled down a host of logical lanes, found it quite impossible to straighten out the mess resulting from too hasty reliance on imperfect information. And wasn’t fate unkind to them on the Wednesday? Mountain swathed in impenetrable mist at noon. Mountain bathed in glittering sunshine at 2pm. In 1937, I imagine they will have to bribe men to act as stewards, for this year’s issue hardly dared enter a bar by the end of the week, such roastings awaited them.”—Ixion

“WOULD YOU PURCHASE A TT machine to-morrow if you could prevail on your pet firm to sell you one, and if you had the necessary dibs? Loud, envious, enthusiastic affirmative chorus of answers, I suppose. No doubt we all would. But should we get our money’s full worth? Where could we unleash its 110mph (?) more than perhaps once a summer? What should we have to pay for spares if we broke one of its special light alloy bits? How long might we have to await delivery of said spare? Apart from probably un-canny road-holding, would it be so very much better than a standard roadster at roadster speeds? How much should we drop when selling-time came? The sane answer probably is that we should be quite wise to buy the machine on condition that we intended to do some speed competition work, but that if we are mere fast tourists we might actually be better served with a standard sports model.”—Ixion

“NOT FOR YEARS HAVE I heard the manufacturers in the Island for the races talk so comfortably. The long depression had set some of them wondering whether motor cycling had in part lost its appeal for British youth. Now that a wee boom is beginning to mutter in all-round trade, they find that orders are rising fast. It is clear that the motor cycle is as popular as ever, but that financial stringency forbade many an enthusiast to invest. Did I pat ’em on the back? Not me! I said, ‘For five years you have refused to produce new models because you couldn’t afford it. Now that you are once more making money you will say it isn’t necessary to produce novelties—you can sell what you’ve got. That’s how an industry gets groovy.’ One maker got quite waxy with me. ‘Why,’ he ejaculated indignantly, ‘I list 14 models for 1936.’ ‘True,’ I replied, ‘and not one of ’em shows any radical alteration from 1930.’ He reflected, grinned, and began talking Fours. Within the next two years the trade as a whole will have a golden opportunity to launch out into novelty.”—Ixion

“NATURALLY INFORMATION RE THE ‘also rans’ in the Senior TT is bound to be meagre, with the epic Guthrie-Woods fight for supremacy taking place. (Hats off to both!) From receiving Ebby’s ‘Go’ to my retirement, an increasingly troublesome oil misfire spoiled the twin New Imperial’s chances of really moving. (Last year’s engine and ‘heavy’ tanks were used, incidentally!) The alloy brake shoes in the rear hub ‘fatigue fractured’ and collapsed early in the fourth lap! Again, on the fourth and fifth laps, four plug stops were made. (Don’t we have fun!) Mysterious and sudden periods of seizing now became apparent, culminating in. a locked rear wheel at Glen Helen on the last lap. The chain jumped the sprockets but did not break. And in fairness to Messrs. Hans Renold, Ltd, I should like to say that chains were not the cause of my retirement in the Senior. The rear hub, bearings and remnants of the brake plate were fused together! And as the wheel was immovable, I retired. Lightweight Day I distinguished myself by only reaching Greeba on the first lap before I was forced to change a burnt-out plug. My rev counter had shown me 500rpm down in third, up from Union Mills (plus nasty hot ‘tinkling’ noises from the ‘urge’ dept!) I fitted another plug and got cracking as Arthur Geiss came into view. We did battle, I played on the air-control with a wary eye on the re. counter, Arthur stealing a look every mile to see if he was ‘shaking’ me. He ‘plugged’ on the Mountain on the second lap. That was the last chuckle I got. Fifty yards later the ‘Imp’ expired for good and all at the Bungalow bend. So, dear friends, ‘thatter was thatter’!

‘Ginger’ Wood, Birmingham.

“AFTER GOING TO SEE last year’s Senior TT and having to return owing to its postponement, I wrote to you and said that I should never go again—and at the time I meant it. I have just returned from seeing the Lightweight and Senior Races, and the inconveniences on the boat and the absolutely unnecessary postponement of the Lightweight are enough to make anyone say the same again—that is, if there were to be another real TT. With two friends and their Norton outfit I caught the 1am boat on Wednesday morning from Liverpool. On arrival at about 6am we found no means available to get the outfit off the boat. RAC officials and ship’s officers alike turned a deaf ear to us, and we could hardly manhandle our outfit up about 30 stone steps, as the solo owners bad to do, unaided by the seamen, [The RAC guides are not allowed to handle vehicles.—Ed.] When we eventually got the machine off at about 8am with ramps obtained from the pier we found the RAC men gone and had to push to the nearest garage On Wednesday morning we were on the Mountain near the Bungalow and at 12.30pm visibility was over 100 yards. By 1pm the mist had cleared completely. Everyone, including marshals, was astonished at the postponement to the following day, and one rider expressed his opinion in no uncertain terms. To crown this conics the astonishing decision of the ACU concerning Guthrie in the Junior. How they can possibly justify their inclusion of him in the awards I would like to know. Th rules definitely state that anyone receiving outside assistance will he disqualified. The rider must be capable of starting his machine unaided, and to state that Guthrie did not receive assistance on the course is begging the point. One cannot help feeling sorry for Guthrie, but what about Thomas on the Velocette? It seems to me that the Velocette directors would be far more justified in appealing for the time taken to examine his machine plus a reasonable allowance for the stop and restart to be deducted from his time. After all he received no outside assistance and these one-sided decisions must leave s nasty taste in the competitors’ mouths, particularly after the Guzzi disqualification from second place in 1926 for using a different make of plug. Alter having let off steam, may I say that I really enjoyed the races, particularly the magnificent riding of Woods and Geiss. Woods in the Senior on a slower machine than the Nortons was marvellous. Also, may I congratulate your paper on the splendid reports it published, but most of all for its unprejudiced opinions?

AJ Mohr, Streetly, Staffs.

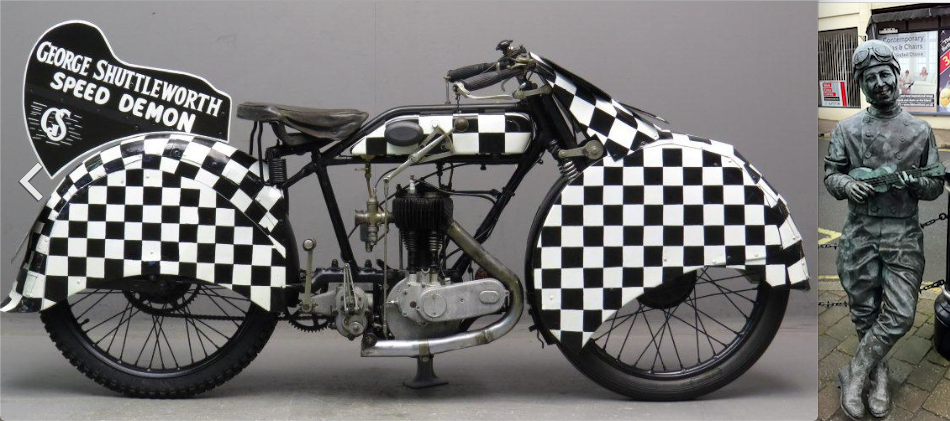

FORGET THE WILD ONES. Forget Easy Rider. The best motor cycle film of them all was No Limit, starring motorcycling ukulele maestro George Formby who was far cooler than Brando or Fonda. Brando was looking for something to rebel against on his Triumph Thunderbird. Fonda was looking for America on his Harley panhead chop. Our George was looking for a fiver to get himself and his bike, the Shuttleworth Snap, to the TT. He falls off the Mona’s Queen, sets a lap record because of a jammed throttle, pushes his bike over a cliff, wins a works ride, punches a bullying competitor on the snoot, pushes his bike over the line to win the race, wins the girl and wins a Sprocket dealership. The film features real TT action and an unforgettable song. All together now: “La la la la la-la going to the Teeee Teeee ra-ces!” If you still need convincing you can see highlights of the film at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ukCc3c6RVo4 and sing along with George at youtube.com/watch?v=eayllywNxUw./ Eeeee! Turned out nice again!

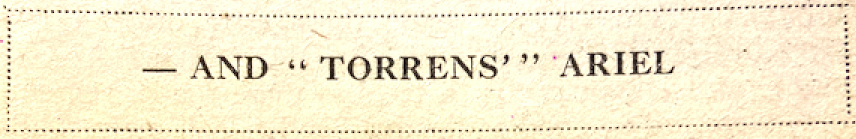

“FRITH IS GLORIOUSLY DIFFIDENT about saying anything concerning riding methods, so I turned to the question of the parts of the TT course he likes best. ‘Kirkmichael to Ramsey,’ he replied. ‘Always have done. You seem to tear through there, going so much quicker.’ As he said this I went with him in spirit around the course—those glorious sweeps, much of the going either under or beside trees: just imagine it all on a really fast mount! His pet aversion is Quarter Bridge, with its more-than-a-right-angle turn, approached downhill. It feels like ten miles an hour, and there is an adverse camber on the far side; I rather think that his wholesome dislike of the corner is shared by others! ‘How much gripping of the bars do you do?’ I asked. He replied that it is only on the straight bits of the course that his hands are merely resting on the handlebars; for the rest they are ‘gripping’, and on S-bends one hand is pushing—first one, of course, and then the other; the riding position is such, remember, that the rider’s arms are nearly straight. Frith marvels at the Norton riding position, and the way Joe Craig has got it dead right; it suits every member of the Norton team.”—Torrens.

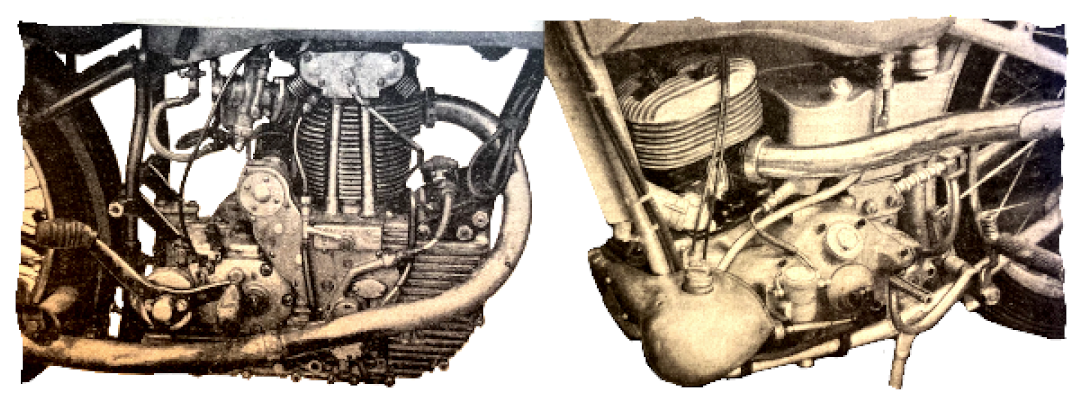

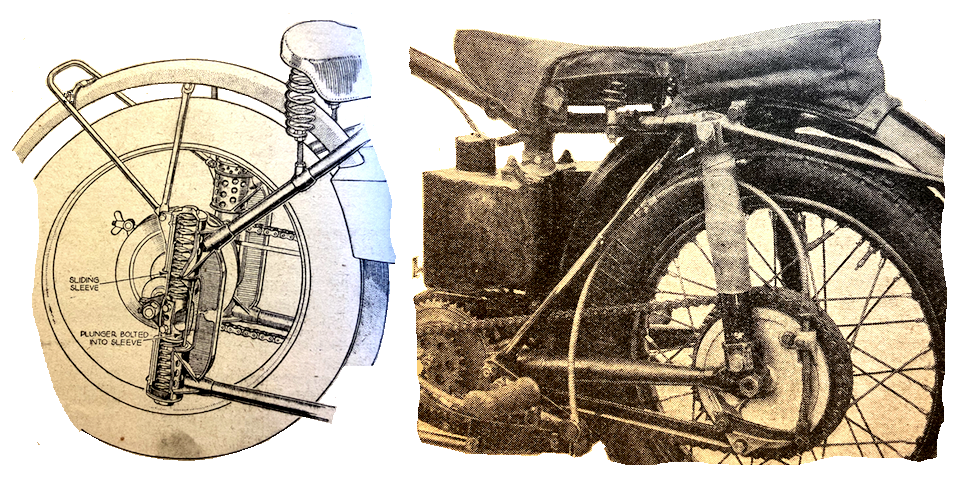

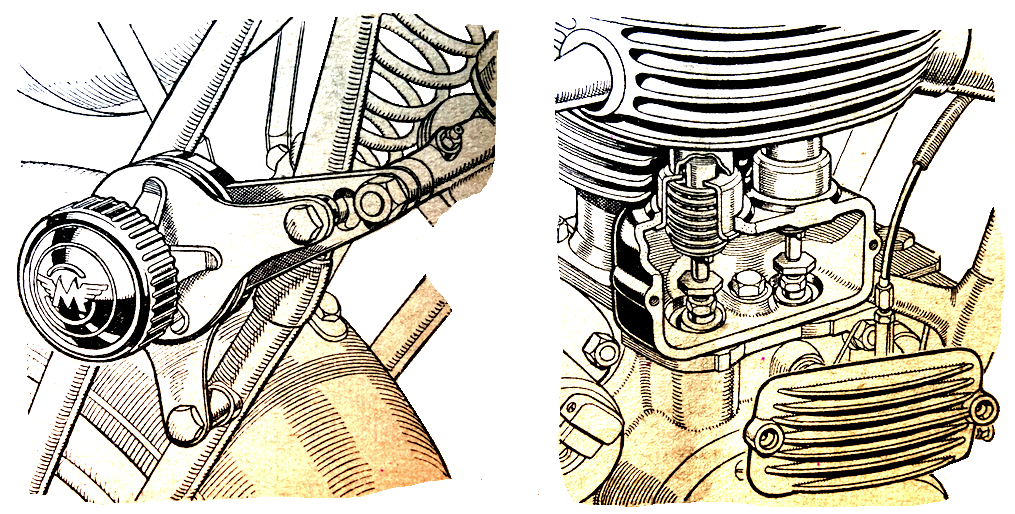

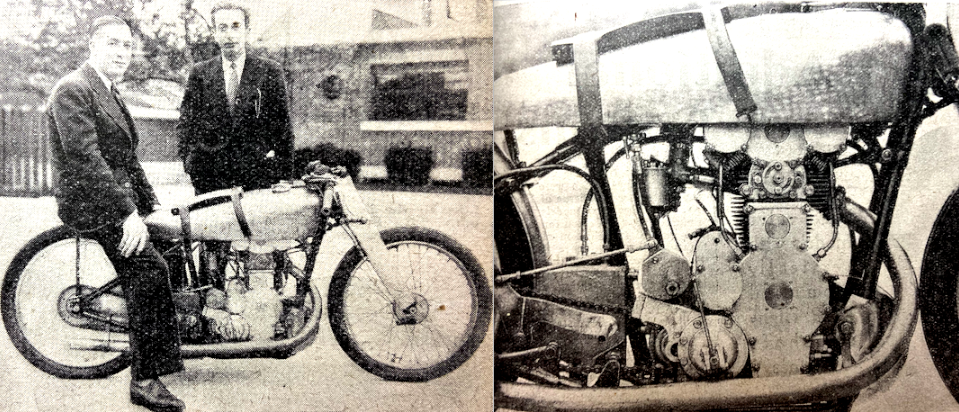

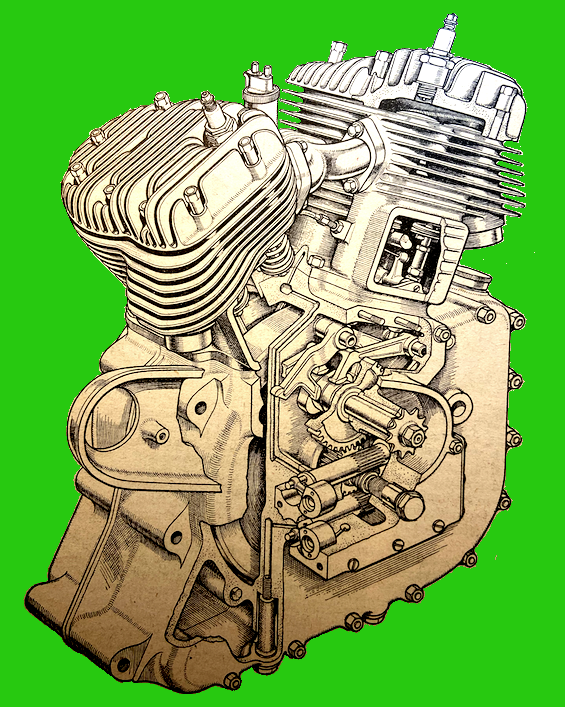

‘UBIQUE’, THE BLUE ‘UN’S de facto technical editor, had clearly spent a lot of time in the paddock: “There have been many changes in design which are of technical interest; some have been highly successful, some have been less so, but all should be chronicled…The first point of interest is the adoption of spring frames by the racing Nortons and Velocettes, in addition to the Vincent-HRD design, which remains substantially unchanged. The Norton frame consists of a pair of spring-loaded, light-alloy pistons, one on each side of the rear frame, coupled by a long and very stiff axle. The design is extremely simple and robust, and although-small changes in the length between chain centres are inevitable (actually the maximum change in centres is ⁵⁄₆₄in), they are of minor importance. I have heard criticism on the score of the stresses imposed on the spindle, but these may be discountenanced, since the point is so obvious that the manufacturers would be the first to ensure adequate strength and stiffness. The Velocette rear suspension is entirely different, and there are no springs whatever included in the design. The chain stays, pivoted at the front end, consist of very large diameter tubes tapering rearwards and splined in front to a large-diameter cross-member. The weight is taken by cylinders of air pumped to a pre-determined pressure, and the action is controlled damped by a flow of oil (contained in lower cylinders into which the air chambers telescope) through small controlling jets or orifices. The device, in fact, resembles an aircraft landing gear, and it is extremely efficient. It is obvious that the air chambers can be pumped up to suit the weight of the rider. New Imperials did not use their spring frame, purely because they had insufficient time to prepare a machine for the race. Next in order of interest comes the question of superchargers. Vincent-HRDs have carried out a lot of experimental work, but decided before the race that still further experiment was needed and raced without compressors. This does not necessarily mean that they have abandoned the idea altogether, but it is a curious feature of the supercharger—at least as regards its application to this particular engine—that the machine appears to run equally well with a wide range of mixtures and ignition settings. On the other hand, it is vital that the mixture should not be so lean as to cause overheating, nor so rich as to cause excessive fuel consumption. As regards the blown four-cylinder AJS, the pressure was reduced before the race, and it is not unlikely that further experiments will produce much better results. At the moment it would appear that more data is required before a supercharged TT winner makes its appearance. The case of the DKW two-stroke, with its piston-type compressor, is somewhat different. The makers have a wide experience of the type, which was designed in conjunction with the engine, and they had already registered many success.. It remained only to see if a compromise could be reached between sheer power output and reliability sufficient to complete the course. In this they are helped considerably by water-cooling and—this year—by ribbed aluminium head jackets. In engine design there has been more change than meets the eye. Compression ratios have gone up with a bump, and, since a designer is always likely to employ the highest ratio possible consistent with reliability, it is clear that changes must have taken place internally to permit of the increase. More than ever before there was a tendency for designers to withhold particulars of the compression ratio in use, but when I state that ratios of up to 9 to 1 on Senior and over 10 to 1on Lightweight machines were tried, and tried successfully, on petrol-benzole mixtures, it will be realised that there must have been considerable advance in cooling to enable such ratios to be used The vital point lies in the cylinder head, and more particularly in the neighbourhood of the exhaust valve. New methods of head construction, improved materials, increased fin area, careful port design, and other less obvious devices were employed with success. High-conductivity alloys are the rule rather than the exception for cylinder heads, and these range from aluminium-bronze heads, such as those on certain Velocettes, JAPs and Excelsiors, through composite aluminium-bronze and light-alloy heads, such as the Norton and New Imperial, to aluminium-alloy heads with inserted valve seats—as on Velocettes and AJSs. In some cases the inlet seats were of bronze.”

“IT LOOKS AS IF TECHNICAL developments have butted up against a terminus, so far as existing designs of ohc single-cylinder engines are concerned. It is true we did not get one day in the three which was ideal for record breaking. The stars they want dry roads, no wind, perfect visibility, no sun, and no flies in order to scrape the last split second off the course. These pluperfect conditions were not offered this year, worse luck. But the fact is that machines were only faster than in 1935 by the very tiniest fraction. If there is an exception to this it can only be sought in the theory that Guthrie s never drove any faster than he was compelled to drive, and that in the Senior he always had a scrap of throttle up his sleeve. I doubt it. Guthrie won by 18 seconds. If Woods had been mechanically able to ride his last lap in the same time as his sixth lap, Guthrie would have won by two seconds. Guthrie does not consciously run matters as fine as that. Woods’ engine misfired for a long spell along the back of the Island. Guthrie’s last lap was a smasher. On the clock it took him 26min 22sec, but from that we have to deduct (a) 15sec stationary at his pit while he sloshed in a few pints of juice; (b) slowing for his pit; (c)re-starting; (d) accelerating from rest up to maximum for Bray Hill. Total loss, at least half a minute. Deduction: Guthrie did his last lap in under 26min, ie, at an average of well over 87mph. Why did he not let out an 87 or 88mph lap earlier in the race? Because he dared not. Why didn’t he dare? Either because he did not want to smash himself to bits or because he was afraid of bursting his engine. Machines were only fractionally faster than in 1935, or, allowing for road improvements and spring frames, no faster!”

“‘IT IS NOT A PICCADILLY CIRCUS machine, you know.’ With these parting words from Joe Craig, I walked over to the spare machine—the fourth of the four new 500cc spring-frame Nortons. Alec Bennett, who had been trying it, handed it over and told me which way the gear lever works. He also told me a lot more, for he was fairly bubbling over with enthusiasm. The point of my run was not to try any funny business, to endeavour to emulate a TT star, and that sort of thing, but to learn what the spring frame is like in ordinary hands. Brief though the trip was I learned a lot. That spring frame adds immeasurably to the machine. No longer is the rider thrown about; the machine sits the road almost like the tarmac that surfaces it, and, in the words of Jimmy Guthrie, on corners you can pick any line you like. It will go exactly where you want it to go. As 1 have said several times before, a good spring frame is one of the greatest safety factors imaginable. Some people stress the comfort afforded by a spring frame. I look upon this as of secondary importance. The great point is that first-class rear-wheel springing spells safety by improving the road-holding and by enabling the rider to steer to a millimetre. Half the so-called steering troubles that are experienced result solely from the rider being thrown about; it is he who causes the machine to do strange tricks, generally through thrusting and heaving on the bars. The Norton steering is superb—there is no other word for it. The rider can concentrate on riding. For myself, I learnt that the road-holding of the spring-frame job is cent per cent. better than that of the racing Norton I rode a couple of years ago. Because of this magnificent road-holding, the steering and braking are both greatly superior. Really there is no comparison, and now with the spring frame the rider has a really comfortable ride. Witness how Freddy Frith after finishing in the Junior handed his machine to a marshal and ran—yes, ran up the road to the Paddock!—Torrens.

VELOCETTE’S RETURN TO the 500cc sector with the ohv MSS was clearly worth waiting for. The Motor Cycle’s roadtester reported: “Throughout there is evidence of good workmanship and accurate assembly…it would be difficult to find a more charming motor cycle. Excellent engine balance and a silky transmission rendering the machine equally pleasing for town riding or the open road. At speeds up to 30mph the Velocette was markedly caner as regards its exhaust, and bearing this point in mind the mechanical silence was exemplary. In spite of the fact that the top gear ratio is 4.4 to 1 it was unnecessary to change gear continually. There is something fascinating about a machine that will pull a high gear successfully. High averages can be accomplished without fuss or noise so that the journey becomes less fatiguing. It will tour all day at 60mph. The steering was faultless. Hands off riding at 70mph…was automatic. As regards fuel consumption the machine was good: a gallon of fuel being enough for 88 miles…Oil consumption was negligible. The prop stand was a boon—the finishing touch to a very fine machine.”

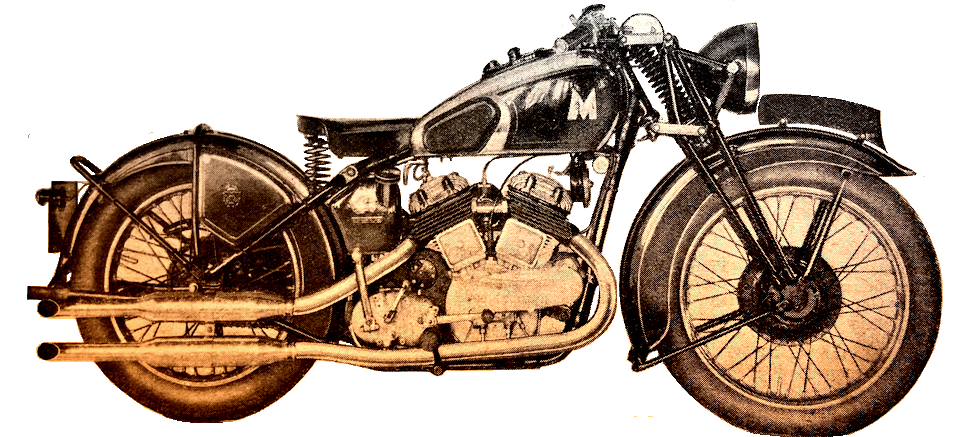

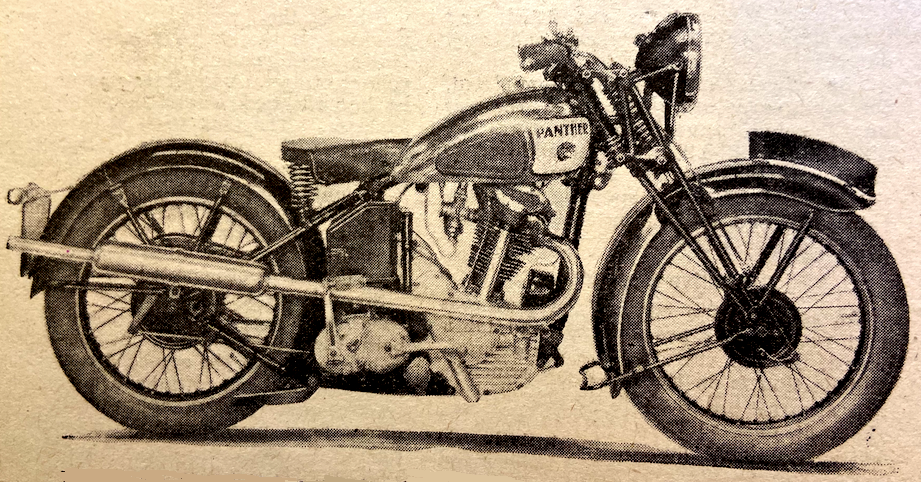

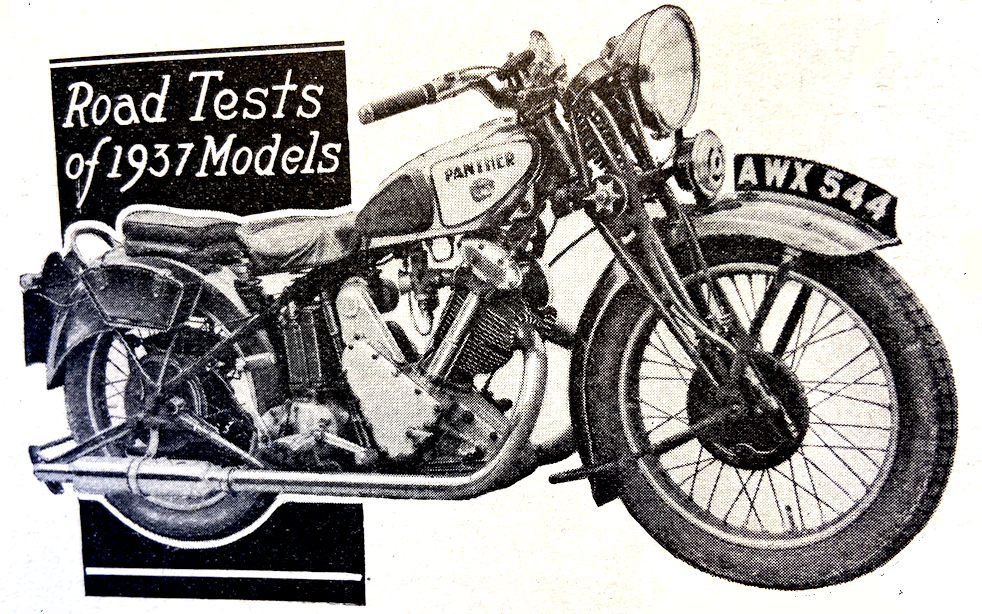

…AND HERE’S AN EXCERPT from the Blue ‘Un’s test of the 600cc Panther M100: “…a most imposing machine…the Burgess silencing system was so effective…the mechanical silence of the engine too was an admirable feature…road-holding at all speeds was excellent…cornering was excellent, and under greasy conditions the steering was such as the impart every confidence…the engine kept perfectly oil-tight…under give and take road conditions the petrol consumption worked out at 103.2mpg.” Panther claimed a top speed of 80-85mph solo or 65-70mph with a chair.

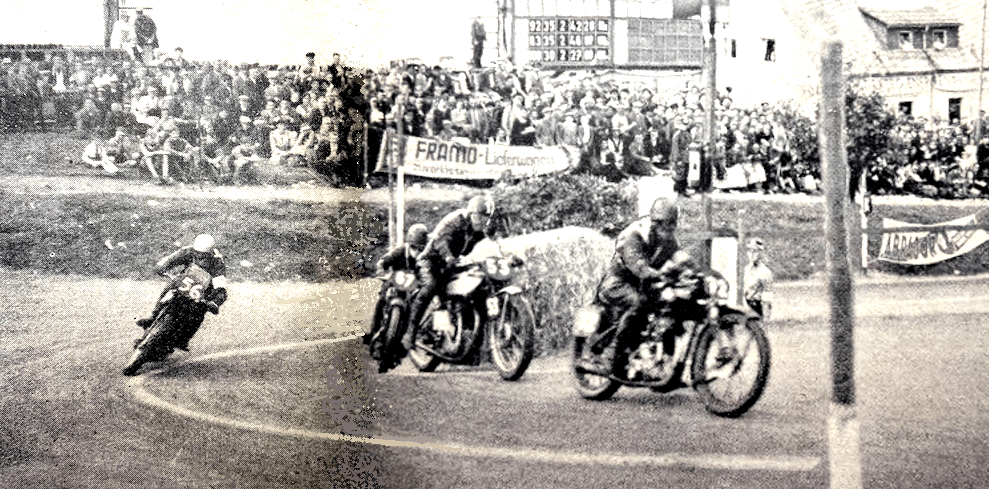

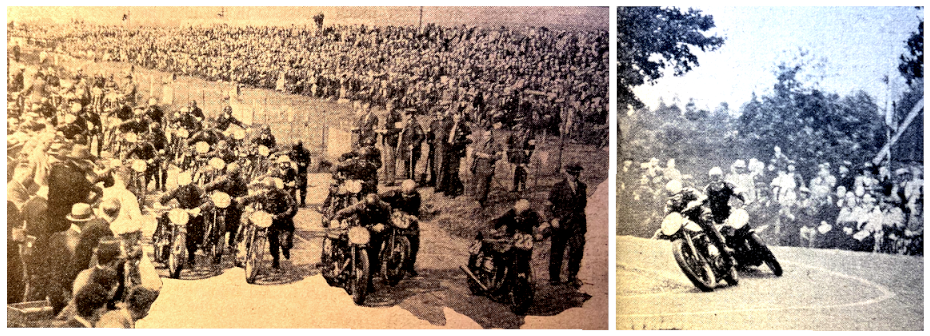

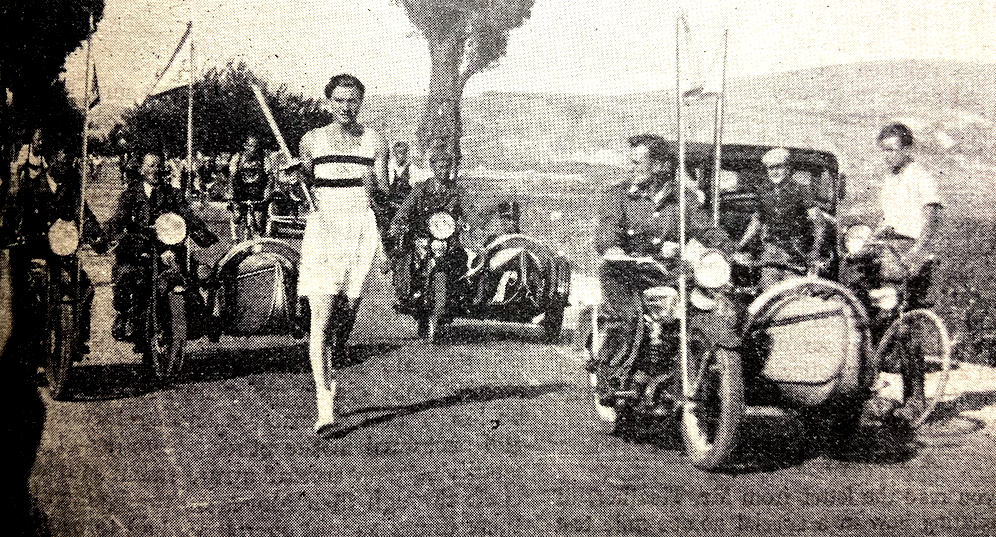

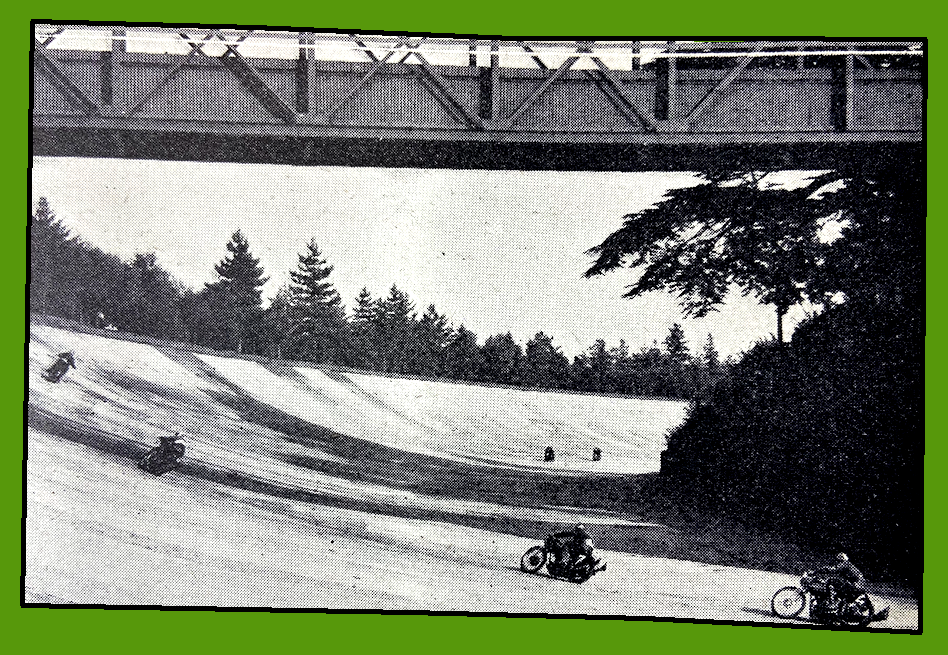

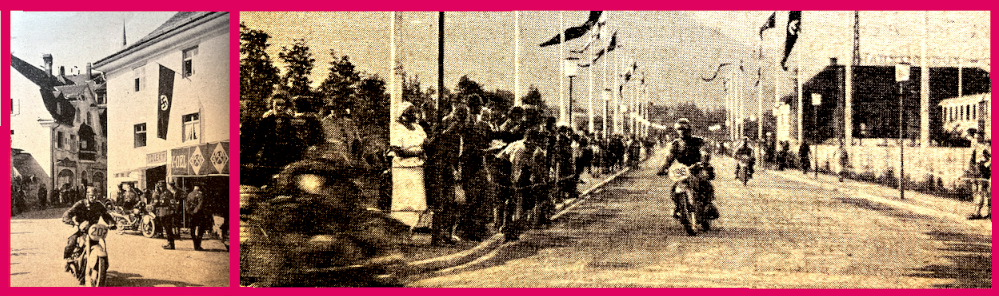

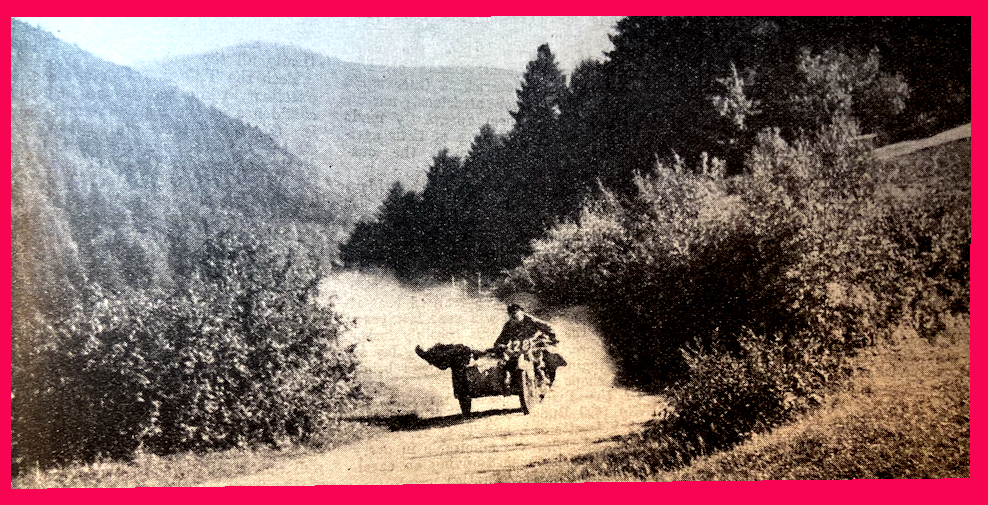

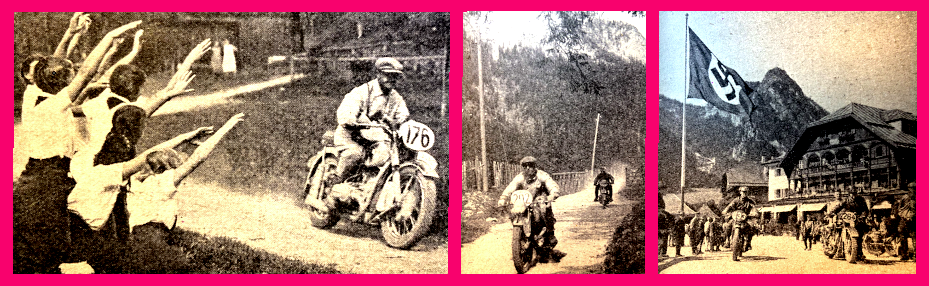

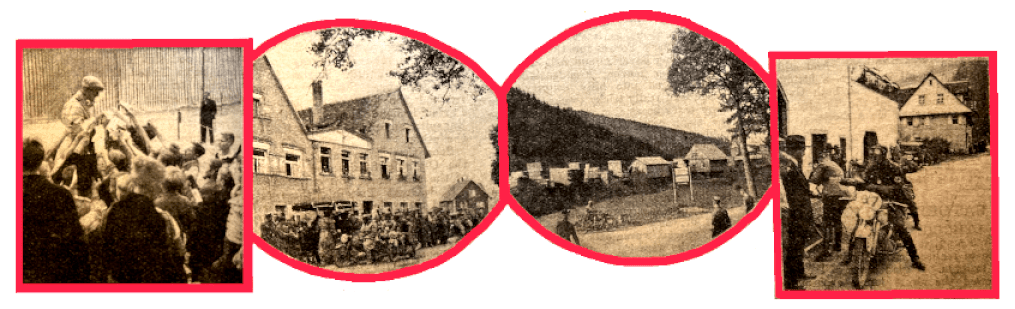

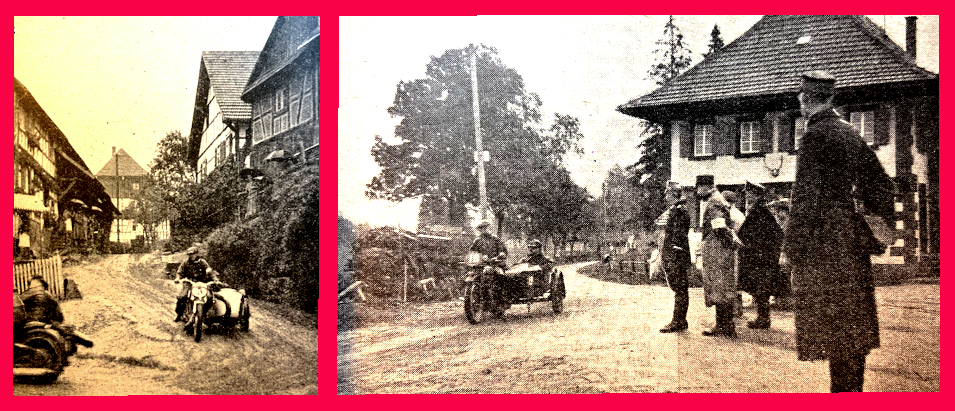

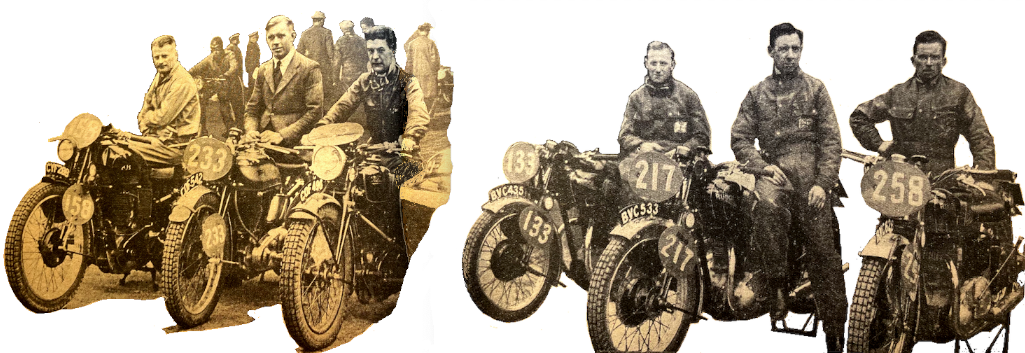

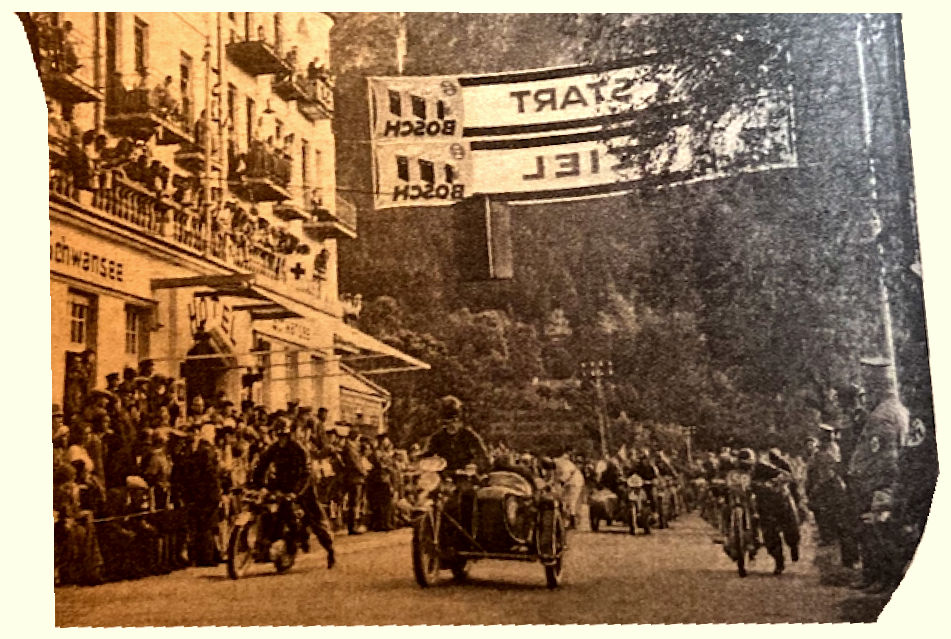

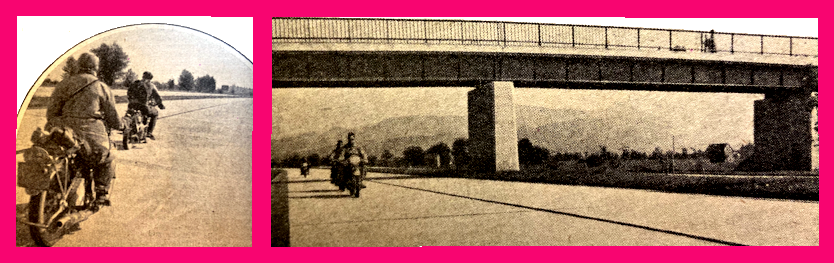

“LAST WEEK-END, IN THE FICM Grand Prix of Europe, held in Saxony, British machines swept the board in the three major classes. J Guthrie (490cc Norton) and JH White, on a similar machine, were first and third respectively in the 500cc race, while FL Frith (348cc Norton) won the 350cc race, with EA Mellors (348cc Velocette) and ER Thomas (348cc Velocette) respectively fourth and fifth. The 250cc event was won by HG Tyrell Smith (248cc Excelsior), with a German rider, B Port third on a 249cc Rudge. No one succeeded in finishing in the 175cc class [Eric Fernihough was leading four German riders on MMs when his Excelsior-JAP dropped a valve—Ed].The race attracted a huge crowd—over 240,000 people paid for admission, and they had come from all parts of Germany, many of them arriving the evening before with the object of sleeping near a vantage point on the course. Throughout the night Army searchlights from a hill-top swept the ground looking for people trying to avoid theadmission fee. Racing was due to start at 9am, and as there were three separate races it was going to be a long day. The triangular five-mile course, situated outside the picturesque Saxon village of Hohenstein-Ernstthal, near Chemnitz, was lined, inside and out, three, four and five deep with spectators. It a difficult course, full of intricate bends (with IOM-type warning signs) and steep gradients. The pits and chief stands are situated on the southernmost leg of the course. Above the starting grid is a ‘traffic’ light, which shows red, orange or green according to the requirements of the starter. ” Here’s the Blue ‘Un’s blow-by-blow account of the main event: “It is nearly 3.45pm before the 500cc class is despatched. Through nearly 200 loudspeakers around the course, a deep, Teutonic voice announces ‘Achtung, achtung! Rotes licht! Noch eine minute bis zum start!’ (Attention! The light is at red!

Only one minute until the start!) A few seconds later the light is at yellow, and then simultaneously with the nerve-shattering explosion of a maroon the green light appears and they’re off. The rain has ceased, but it is very dull and overcast. In spite of the weather the vast crowd, which has patiently stood all round the course since 8am and possibly earlier, is all agog to see the riders off on this the most important event of the day. It is going to be a terrific race: The Guzzis are known to be exceptionally fast. The BMWs are possibly a shade faster, while the senior DKWs, judged on their practice form, are something to write home about. All this is a knotty problem for the Norton camp to tackle; White and Guthrie (Nortons) are the only British riders in the race. However, at the end of the first lap, with all the riders in a bunch, the flying Scotsman is in the lead. Close behind are Steinbach (DKW), HP Müller (DKW), JH White (Norton) and Fleischmann (NSU). On the second lap the positions are unchanged, but the next sees a gradual thinning out of the field. Guthrie is clear 20 seconds ahead of Müller (DKW), who has overtaken Steinbach (DKW). White is sitting on the heels of the DKWs, obviously riding to orders. But where is Tenni and the Guzzi? At last over the loudspeakers comes the news that he has crashed beyond Hohenstein, though without serious results. Then Gall (BMW) drops out, leaving 0 Ley to carry on the name of BMW alone. Six laps later Guthrie has definitely. established a lead over Müller’s DKW, while Steinbach has a grand tussle with the DKW rider for second place. Lap after lap they fight it out; first it is Steinbach, then it is Müller, while White (Norton) holds a watching brief just behind. Fleischmann (NSU), in fifth place, struggles to keep away from the ever-pressing Ley (BMW). Half distance sees Guthrie come in for a pit stop, while White proceeds to overtake the DKWs and lie second. Then the two DKWs come in. By an unfortunate accident Steinbach gets the full force of the boiling -water from his radiator in his face and all over his leathers. With the consequent pain he drops his machine and nearly knocks Müller over at the same time while fuel goes gushing over both of them. As a result their pit stops, instead of taking 30 seconds, last for nearly a minute and a half. This slip rather spoils the excitement of the race, for Guthrie and White are well ahead. Ley (BMW) comes in for his stop and likewise makes it rather a long one; he appears to change a plug. The delay lets Fleischmann into fifth place. The order of the leaders remains unchanged until the 32nd lap, when Mansfeld (DKW) comes into the picture, displacing Fleischmann from fifth place. Meanwhile Müller (DKW) has been creeping up to White (Norton) and by the 37th lap—only two more to go—he is just eight seconds behind White, the latter having come off on the bend in Hohenstein. How tho crowd loves the scrap! Müller was actually level with White as they passed the stands—everyone went delirious with excitement. The end of the last lap sees Guthrie (Norton) cheered to the echo—an easy winner. But actually the crowd is much more interested in who is going to come out on top in the White-Müller duel. At last these two can be heard, then seen swooping down the dip to the last bend. White is ten feet in front! The excitement is terrific, with the crowd yelling itself hoarse. Then comes the real climax. White goes wide and strikes the hay barrier on the last corner, while Müller nips round on the inside and is away before White can get going again. More amazing still. Muller on his last lap has broken the record for the course, at 82.63mph. Just as there was a battle for second place, so is there another for the fourth position, between the DKW riders, Mansfeld and Steinbach. It looks like a victory for the latter, but on the last lap Steinbach falls and lets H Fleischmann (NSU) and Sunnqvist ( Husqvarna) into fifth and sixth positions. Once again it has been a British victory, and once more the crowd stands motionless with arms upraised for the British National Anthem—and how they cheered when Guthrie received Herr Adolf Hitler’s prize and a special message of congratulation.”

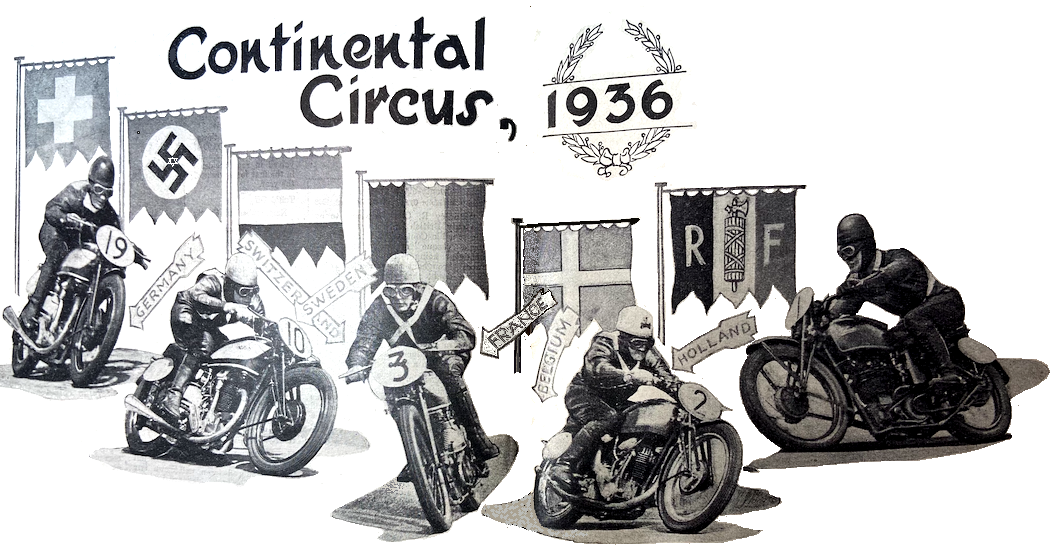

And here’s Ixion’s penn’orth: “Last Sunday saw the first performance of the ‘Continental circus’. This term ‘Continental circus’ may seem strange to some; it is one used by road-racing enthusiasts to denote the annual tour of the Continental races that as a rule follows immediately after the TT. Actually this year one of the big events, the Swiss Grand Prix, was held before the Isle of Man Races. However, last Sunday there was the German Grand Prix or Grand Prix of Europe, as it is called this year, next Saturday the Dutch TT will be held and on Sunday, July 26th, there is the Belgian Grand Prix. The handful of British representatives go from one race to the next, renewing their TT battles and endeavouring to display their own prowess and that of British machines. The first fruits have fallen to Britain with a vengeance. In the Grand Prix of Europe last Sunday, held on German soil against the pick of Germany and other Continental nations, British riders of British machines won three major races. Norton, handled by Guthrie and Frith, won the 500 and 350cc races respectively, thus these two brilliant riders with their superb spring-frame machines repeated their Isle of Man successes. Guthrie, incidentally, won at the record speed of over 80mph. The 250cc race was won by Tyrell Smith with the new four-valve ohc Excelsior. Thus, once again, has the skill of British riders and the excellence of their mounts been demonstrated to the world.”

“A MOTORIST FINED 10s at Bristol for failing to stop at a ‘Halt’ sign declares that he would go to prison for six days rather than pay.”

“TRAFFIC WAS HELD UP in a street in the West End of London recently when a large poisonous tarantula spider escaped from a crate of bananas.”

“IT HAS BEEN SUGGESTED in Parliament that large bomb-proof underground parking places should be built in large cities, thus also providing sanctuary to civilians in the event of war.”

“A NUMBER OF 250cc motor cycle side-car outfits adapted to ran either on the road or on rails are now being used by inspectors employed by the Paris, Lyons and Mediterranean Railway Company.”

BRITAIN PRODUCED SOME 11,000,000 gallons of Benzole.

“A PEDESTRIAN WHO twice jumped in front of a motorist’s car, the second time also striking the motorist’s face, was sentenced to one month’s hard labour at Castle Hedingham (Essex). The pedestrian was summoned by the RAC.”

“AT THE ANNUAL GENERAL meeting of the British Granite Whinstone Federation in North Wales, it was suggested that bigger Road Fund grants should be given to highway authorities who lay down non-skid roads. May we suggest that no grants at all be given to authorities who do not lay non-skid roads?”

“THE CONSTRUCTION OF a network of 120-150ft wide main trunk highways, dead straight, was suggested by David Edwards, Brighton’s Borough Engineer and Surveyor, at a conference last week. Vehicles would attain 100mph, perhaps, for pedestrians would be permitted to cross only at bridges or subways.”

“I THINK THE ACU have made a big mistake in increasing the mileage for the road test part of the National Rally. I have taken part in the last two events, and thoroughly enjoyed them, but I will not be able to do so this year because of the long mileage—it would more than double the expense through having to put up overnight, and my ‘fairy’ would find it too uncomfortable to do 500 miles in little over a day. We both very much regret this, as we look forward to the Rally very much.

A Patterson, Liverpool.”

FOUR THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED miles of main roads are to be taken over by the Government, according to an important announcement made by the Minister of Transport earlier this week. The highways concerned comprise the more important trunk roads, used largely by through traffic. Thus we have the first step towards the nationalisation of the roads—a policy we have urged consistently over the years. The roads are a national asset. The present system whereby there are no fewer than 1,400 road authorities is patently out of date, uneconomical and, from the motorist’s point of view, totally unsatisfactory. All main roads should come under the control of one central body. Then, and only then, shall we have roads of uniform safety—a road system designed as a whole, instead of piecemeal, and surfaces that are standardised and skidproof. A start is being made, though 4.500 miles is but a fortieth of the total length of British roads and but a sixth even of the main highways. We sincerely hope that the Government will press onward and bring all main roads under State control—those in towns and cities included. It is the urban roads that present the greatest danger. It is on these roads that the most accidents occur, and it is these roads that have the most dangerous surfaces.”

“BRITISH RIDERS AGAIN upheld the the prestige of their country by winning the two larger classes of the Belgian Grand Prix, which was held over the Floreffe circuit in the South-East of Belgium. J Guthrie and JH White (Nortons) were first and second respectively in the 500cc class, while in the 350cc race EA Mellors (348cc Velocette) won comfortably from R Renier (FN). This is the first time that the course at Floreffe has been used for an international event. It is approximately 10½ miles long and roughly triangular in shape, consisting of one short leg and two long stretches to the apex at Floreffe.”

“THOSE hundreds of motorists who at one time or . another have been ‘gonged’ for exceeding the 30mph speed limit—and consequently relieved of a portion of their hard-earned cash—will no doubt learn with glee that a private motorist had the temerity to charge the driver of a police patrol car with a similar offence. The police—in the way the police have—promptly retaliated by issuing a summons against the car owner for exceeding the limit while following them! But they reckoned without the AA solicitor, who successfully contended that whereas in the case of the police car there was no excuse for excessive speed, the defendant was within his rights in exceeding the limit, since his car was really being used for ‘police purposes’ within the meaning of the Traffic Act! Needless to say, the police authorities are appealing against the decision to a higher court. All motorists will await the result with interest, and in the meantime they can amuse themselves by trying to find the not-too-difficult moral of this little story.”—Ixion

“VISITED BEXHILL ON MY HOLIDAY, and was delighted to hit a burg where originality replaces the usual demure kow-towing to central road authorities. Only encountered one set of robot traffic lamps. Did not notice a single pedestrian crossing. Found an absolute minimum of those too-popular warnings and notices which are mounted on the kerbs of wide roads, and function chiefly in distracting drivers’ attention from the obstacles in the roadway. This town contains several traffic vortices which are capable of provoking blunders by road users. In every case the necessary warnings and instructions are placed in the proper location, ie, in or on the carriageway., Sometimes they assume the fairly common form ‘Dead Slow’ painted in enormous letters on the actual road surface. Sometimes the wide spaces are split up into obvious lanes by small islands with big bright boards bearing the words, ‘Keep Left’, etc. It was a very pleasant change to ride with my eyes focused on buses, cyclists, old ladies and other obstacles, instead of developing the usual appalling squint by aiming one eye at the actual traffic and the other 45° left or right for kerb notices. If Mr Hore-Belisha survives much longer we shall develop a race of Britons with a permanent 45° squint, and feminine beauty will evaporate off these islands.”—Ixion

“ON A RECENT WEEK-end I met eight motor cycles exhibiting L plaques and carrying pillion passengers. Some of these fair pillionistes may not have been so brave as appearances indicated, for some ‘L’ drivers have been on the road a very long time, being unable to secure their test appointments. But at least three of these ‘L’ drivers struck me as very ellish indeed. So ellish that I was glad to read Mr Hore-Belisha’s promise that motor cycle learners would shortly be forbidden to drive with an occupied pillion.” —Ixion

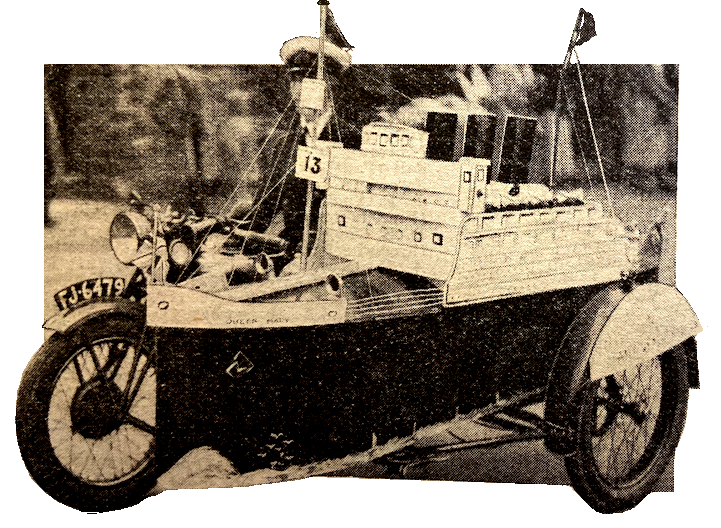

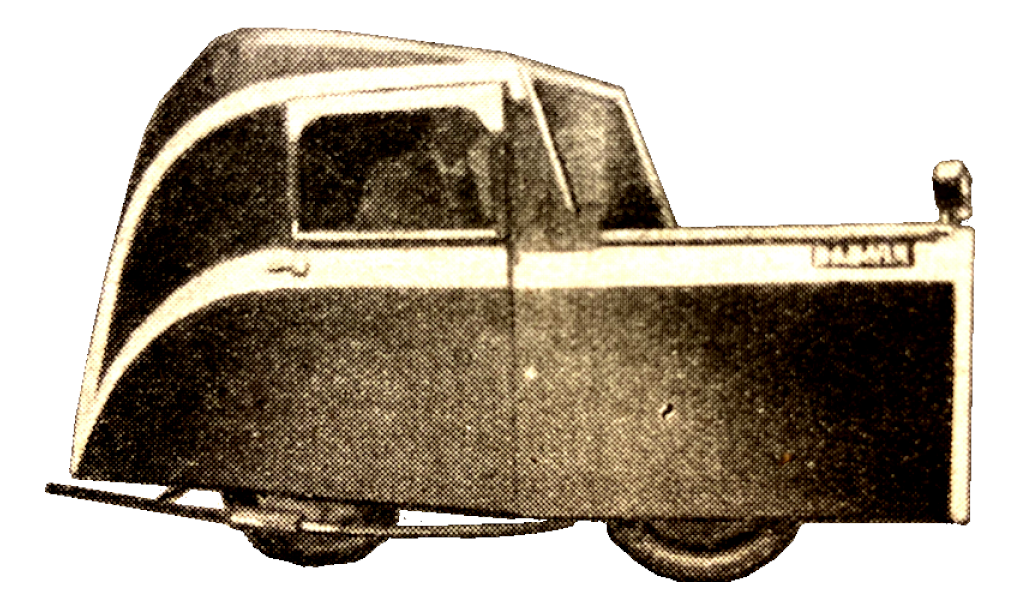

“LAST SUNDAY THE WATSONIAN Sidecar Company held another of its annual rallies for Sidecarrists—at Maxstoke Castle, Warwickshire. And the number and variety of sidecar outfits present were-evidence of the ever-increasing popularity of the event. Cups and prizes were awarded to the winners of the various classes. One of the most interesting classes was that for home-built sidecars. In this category the first prize was won easily by EH Lock, who had an enclosed sidecar on an Enfield machine. It was a beautifully made job and had taken ten months to build. A notable winner was M Harrington, who had covered 636 miles in order to he present. He was followed closely by C Harris, who had ridden 612 miles—two very stout efforts.”