LOOKING FORWARD TO THE new year, Motor Cycling’s pundit Carbon wrote: “1934 will undoubtedly be a good year for motor cycling. National prosperity is on the upgrade and with improved conditions generally, thousands of would-be riders will acquire the wherewithal to invest in machines. Our top priorities must be to win back the world’s fastest record [held by Ernst Henne and the blown BMW] andto regain the International Six Days Trial Trophy [also held by Germany].” Germany had become the most motor-cycle minded country on earth with more than 750,000 riders; motor cycle competition was booming with major events attracting crowds of over 100,000.

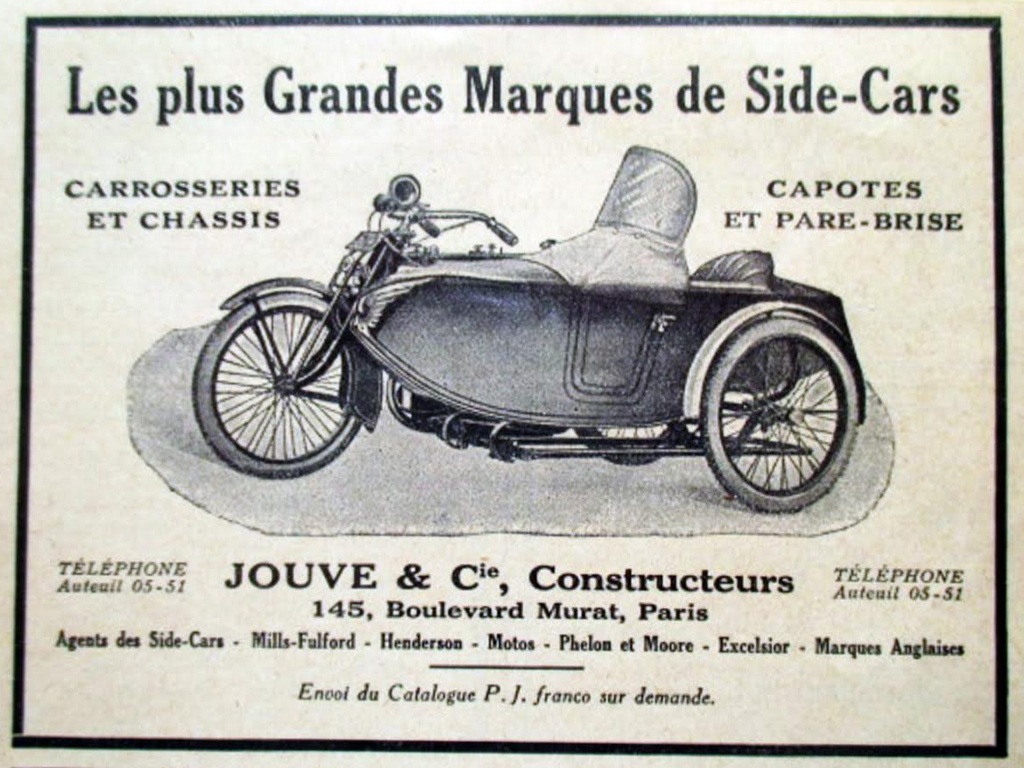

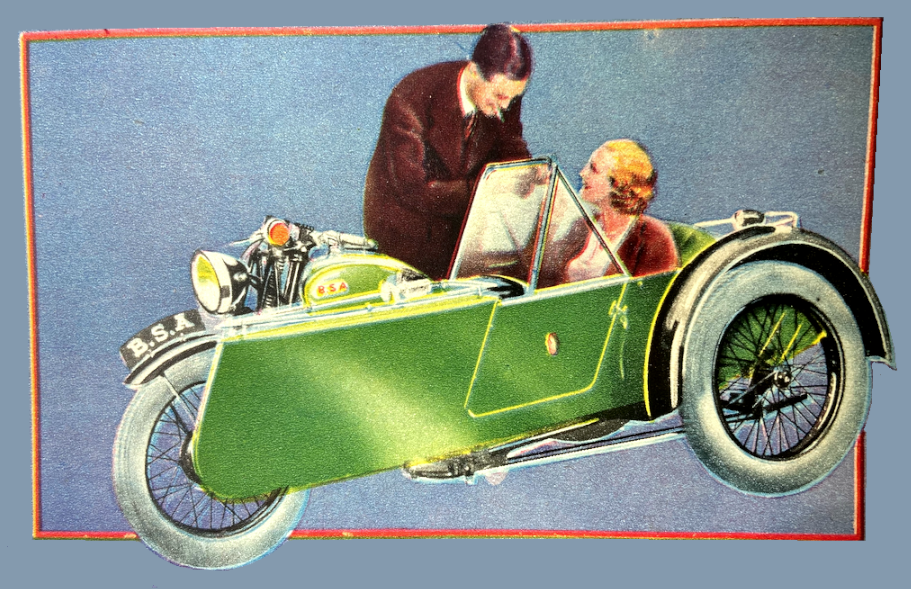

“FIGURES, IT IS ALLEGED, can prove anything. Last year 50,072 new motor cycles were registered for the first time while at the peak period of 1932 the number of machines in actual use was 599,904. Thus we have the fact that roughly one in every twelve machines in use was new. Does this prove that the average motor cycle lasts for 12 years? A slide-rule enthusiast might maintain that it does, but as we all know, the life of a motor cycle, given due care, attention, and, now and then, new parts, is everlasting. What the figures for 1932, which have just been issued, do prove beyond all doubt is the popularity of 15s tax and passenger machines. A total of 8,902 light motor cycles of under 150cc was registered in 1932 together with 8,981 passenger motor cycles, consisting of 4,105 three-wheelers and 4,876 sidecar outfits.”

“REGISTRATIONS OF NEW MOTOR cycles for December last show an increase of no less than 34% as compared with the corresponding month in 1931. The figure is 2,428, as against 1,807. According to a recent return, there were 56,875 motor cycles in use in Switzerland at the beginning of the present year. The total of motor cycles registered in New Zealand as at November 30th, 1932, was 36,314.”

“NO HUMAN BEING CAN expect comfort from a rigid position occupied for six continuous hours,” Ixion wrote, “that ideal is a physical impossibility, unobtainable in a first-class carriage on the Flying Scot. It is equally true that no motor cycle can furnish several changes of position, all compatible with comfort and control. Hence, the designer is up against it in this respect. He is further hampered by the variations in riders’ physique. ‘Torrens’ has the luck to be of normal dimensions, in which he resembles the typical TT rider; so, when he roadtests a winner for us, he feels topping. But if I, scaling fifteen stone, and standing 6ft 3in, take out a TT winner, I am miserable. I have to fake my own buses for my own riding, and often experience a great difficulty in wangling a decent position; if I succeed, most of my pals exclaim with horror when they try my buses round the block. No standard machine fits me at sight, and the chief problem is to accommodate my legs (trousers, 35in inside leg-length measurement), so that they can (a) keep cramp at bay on long runs, and (b) operate the brake pedal quickly, naturally, and powerfully. All of which shows that the factory designer has a tough furrow to hoe when he plans one riding position to suit all and sundry; and each new invention—super saddle, steering damper, and clean handlebar—complicates the job of providing a good range of adjustments. To quote a single example, my long legs have never been really comfortable since saddles were dropped to their present height—or should I say ‘lowth’?”

“THE SUGGESTION HAS BEEN put forward that a motorist involved in two serious accidents within a year should have a yellow disc attached to his car and be subject to a 25mph speed limit. Further accidents would entail the carrying of more discs.”

“A ROUNDABOUT SYSTEM of traffic control is to be tried out at Hunters Bar, an important junction in Sheffield.”

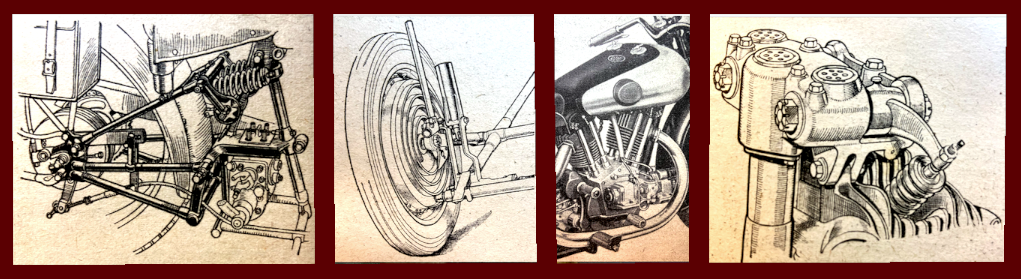

“EACH WHEEL TO ITS OWN BUMP. Car designs for 1934 in America will tend towards the elimination of the front axle, the front wheels being independently sprung, it is predicted in an American contemporary.”

“A £420,000 SCHEME to reconstruct and widen Chelsea Bridge to take four lines of traffic has been approved by the London County Council.”

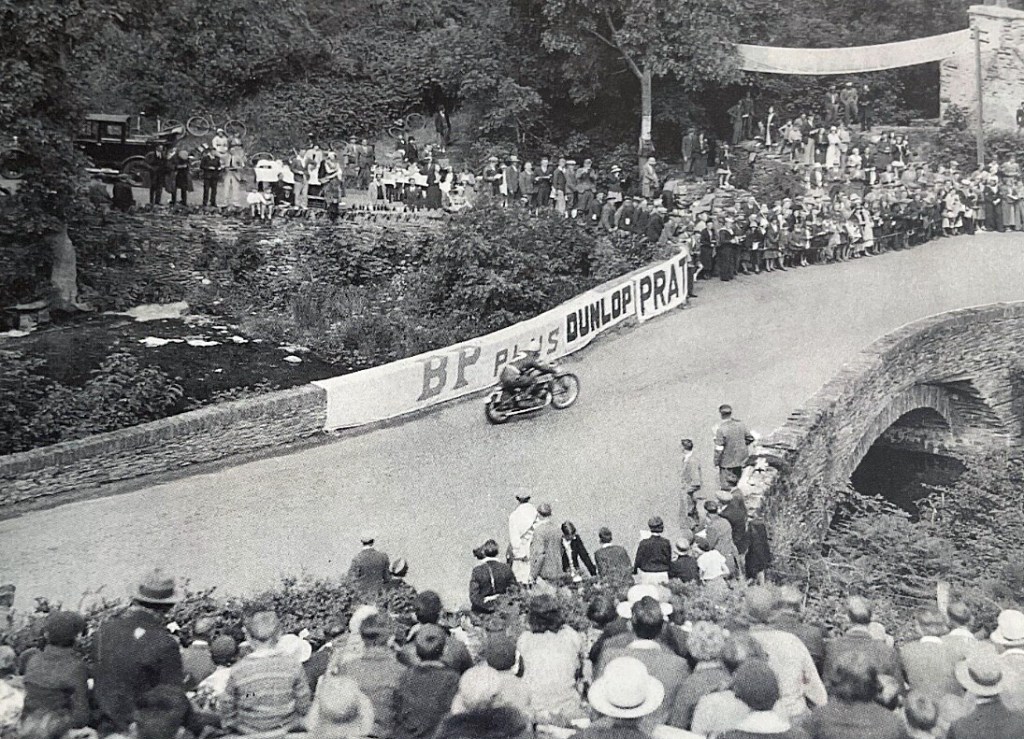

“FOLLOWING AN ACCIDENT, alterations may be made to the road at Ballig Bridge, in the Isle of Man, but it is said to be unlikely that the famous hump, responsible for so many TT thrills, will be removed.”

“SILENCING THE GAY CITY. The ‘zones of silence’ scheme in Paris has proved so successful that the period during which drivers must not use any loud warning instrument in certain districts has been extended to operate from 11pm until 6am.”

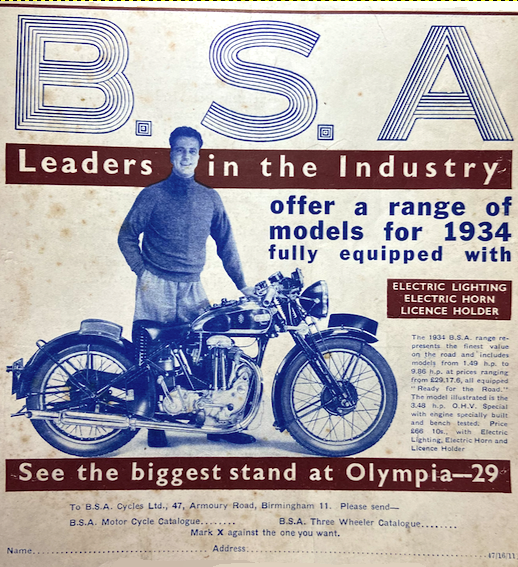

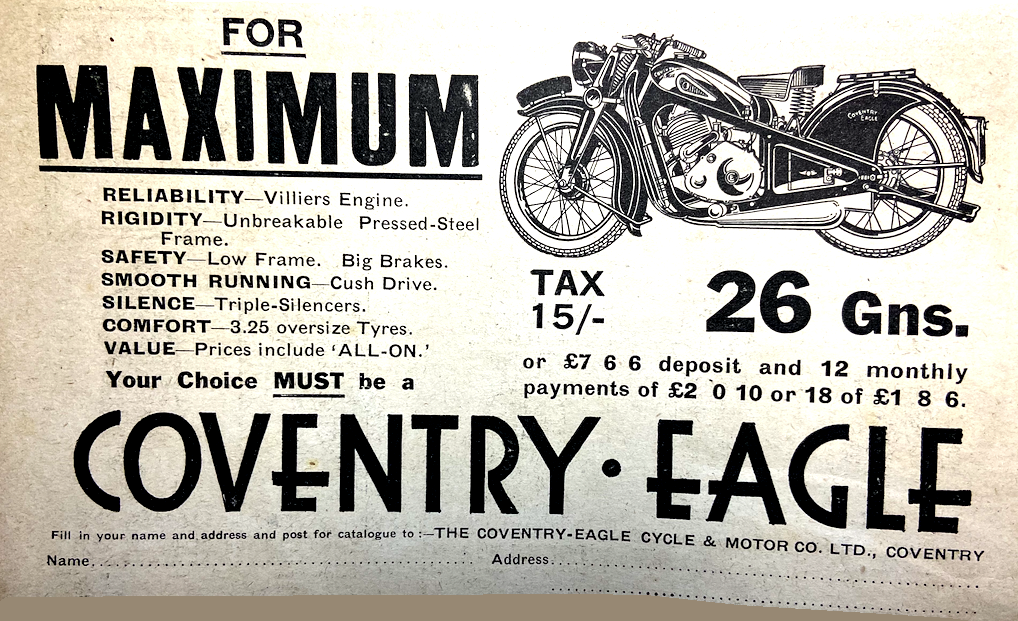

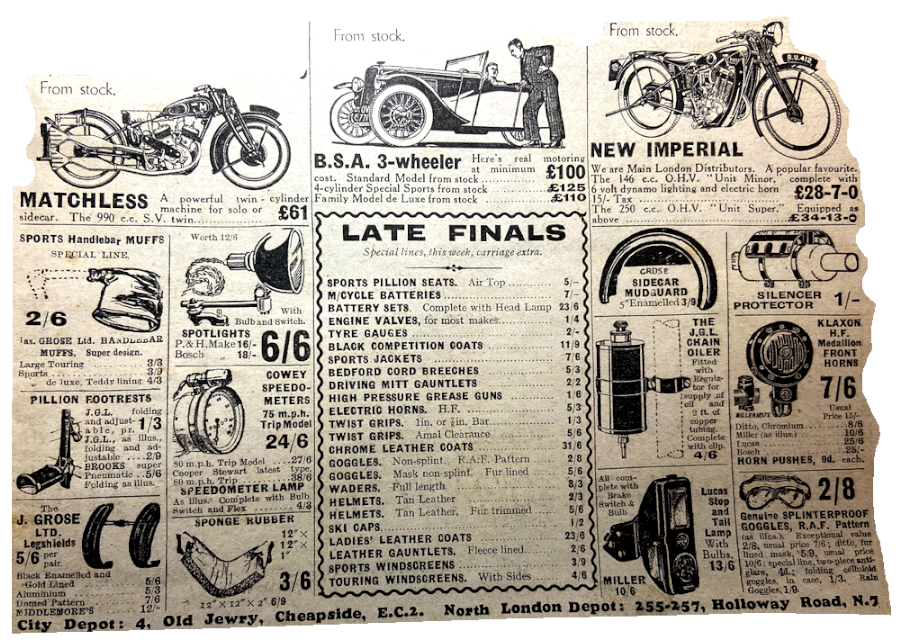

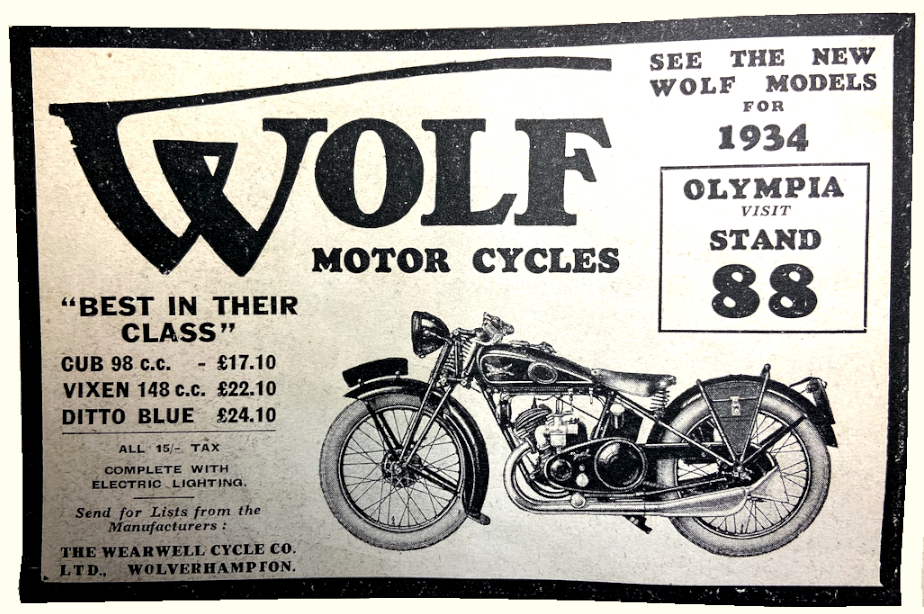

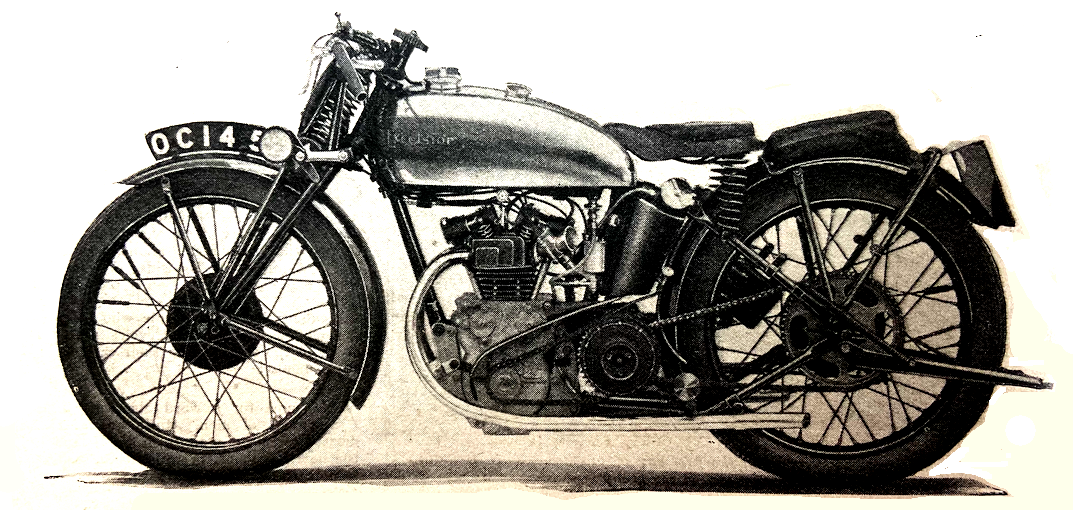

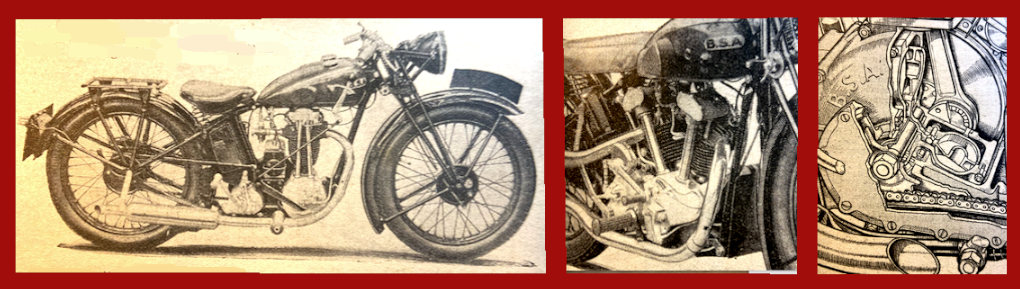

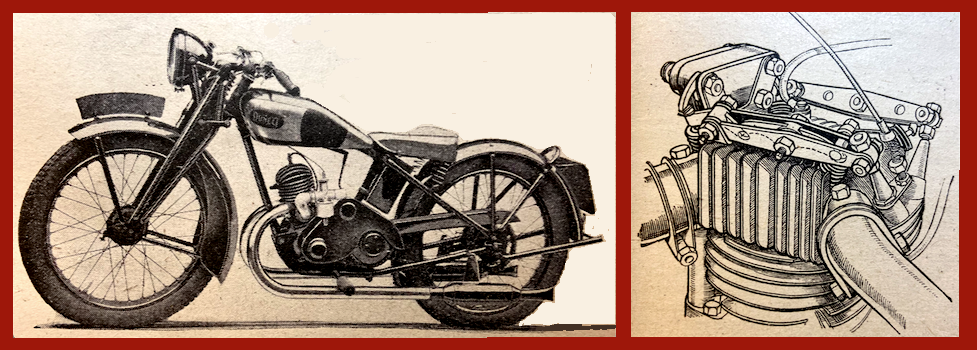

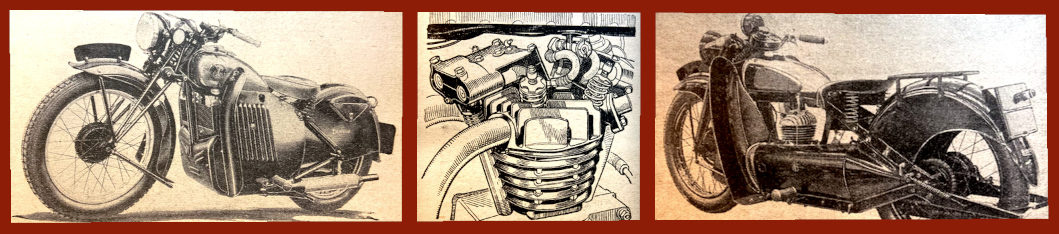

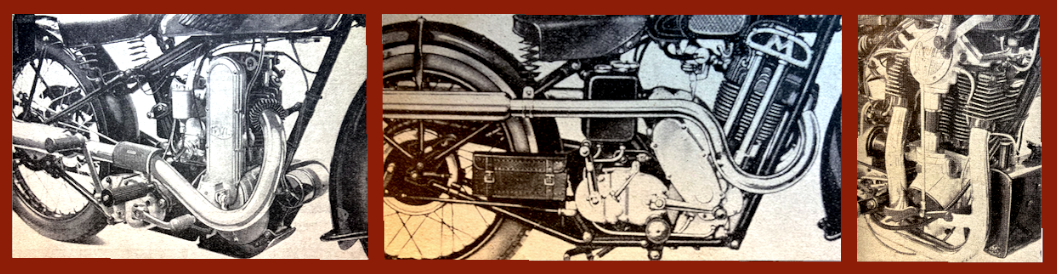

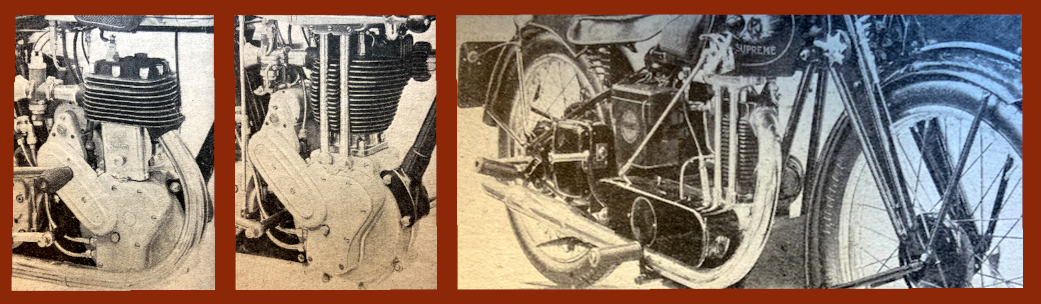

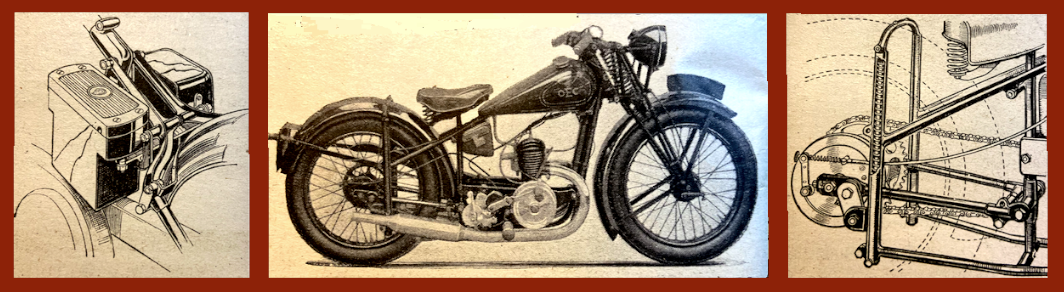

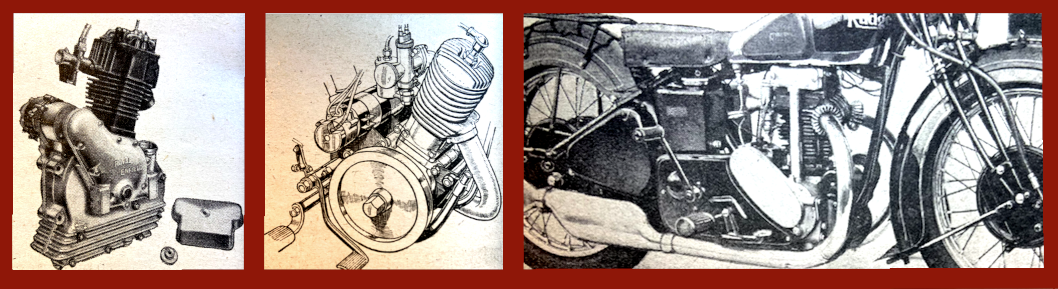

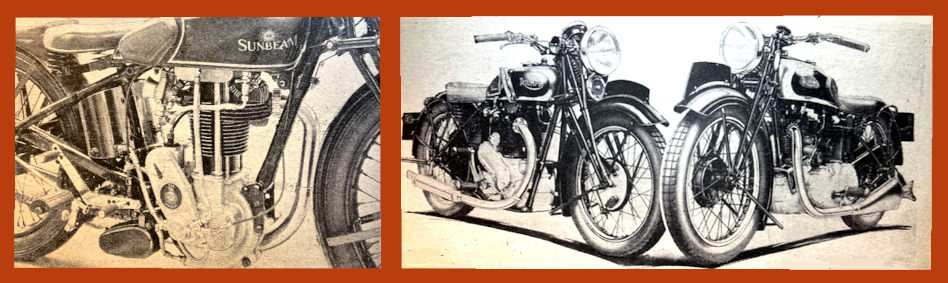

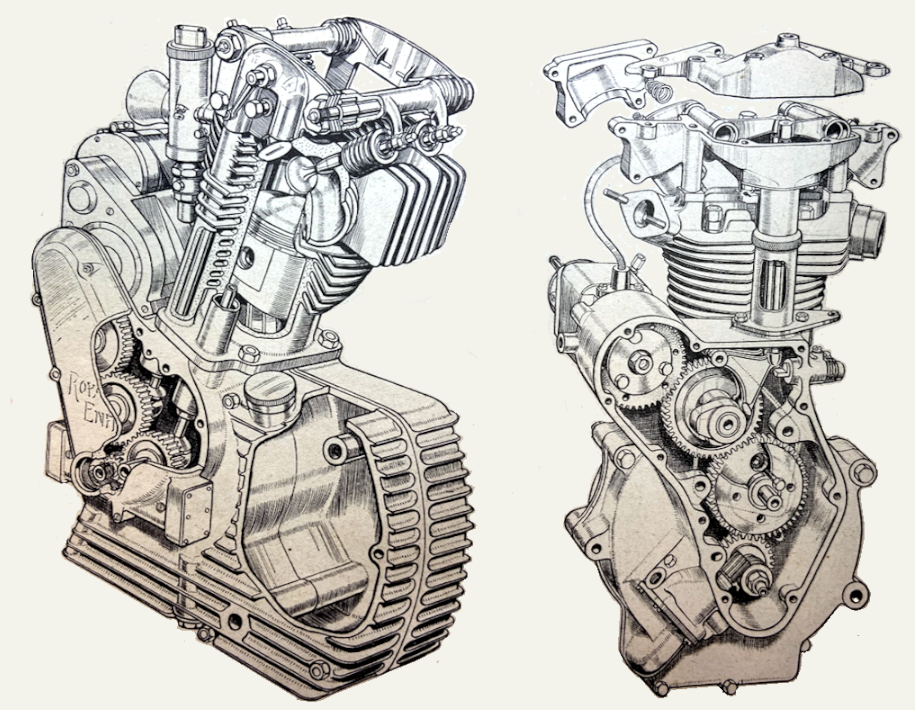

THE ROADTAX SYSTEM CHANGED AGAIN, and from now on it would be based entirely on capacity rather than weight. Bikes up to 150cc paid 15s (75p); 150-250cc, £1 10s (£1.50); and over 250cc, £3 (£3). A whole class of 150s poured onto the market—more than a third of British manufacturers, from AKD to Wolf, jumped onto the 150cc bandwagon. Many of them, including Wolf, used Villiers engines but a number, including AKD, BSA and Royal Enfield, made their own.Cheap road tax for 150s was designed to help low-paid workers afford powered transport as well as boosting demand during a recession and many 150s were utility transport. But New Imperial’s 150cc Unit Minor was among those to show how much motor cycle could be squeezed into the 150cc package. Dorking, Surrey dealer Harry Nash sleeved down a Unit Minor to 125cc, fitted it with partial streamlining and lapped Brooklands at a shade under 73mph.

“THERE HAS ALWAYS BEEN a tendency among the hard-bitten riders of ‘big stuff’ to consider that anything with under 250cc in its cylinder barrel is unfit for consideration. At one time the thick black line was placed higher in the scale, but during the last few years the 250 has proved itself to be more than satisfactory for strenuous road work—a result largely attributable to track- and road-racing experience. The two smaller classes, 150cc and 100cc, have been left to themselves and to the tender mercies of the average rider for development. Actually, the most startling feature of these sizes is an ability to stand up to unlimited hard work without tiring. Your 98cc machine may not provide an extravagant performance, but it will do its work well and without complaint, and it will give you full value for the extraordinarily small capital outlay. Its running costs, too, are ridiculously low. Excluding depreciation, and allowing for a 5,000-mile year, it works out at something in the vicinity of ⅖d per mile. This figure is based on a tax of 150s a year, a third-party insurance premium of 30s, a petrol consumption of 130mpg, and an oil consumption of 2,000mpg. These consumption figures are not just imaginary, but are those actually obtained from a machine which was being given all the hard work I could give it. This particular model was, of course, a two-stroke—a very good example—and would hum merrily along at 28mph, with a sustained maximum on the level of 36mph. It had a low top gear and would take all normal main road hills in its stride, while the two-speed box provided a low ratio for really heavy going and for getting away. A single-lever carburetter and fixed ignition reduced the control work to a minimum of gear lever, clutch, throttle, and brakes. These last were more than adequate, despite their small size. The machine was not silent, but the exhaust note was pleasant, and the engine two-stroked regularly except when running light. Mechanical noise was confined to a primary-chain swish and to slight piston rattle when the engine was cold. Such a light machine—it weighed little in excess of 100lb—was ridiculously easy to manhandle in and out of a normal house gateway, and it was on two occasions lifted right round bodily without excessive physical effort. Its lightness was reflected in the steering, but this was perfectly sound, and at the low cruising speed the machine clung quite miraculously to the earth. Neglecting a short scamper on a real racing job, and a long tour on one of the fastest of fast big twins, my most interesting and instructive ride last year was in the saddle of an ohv 150cc model. I set out with the intention of covering a minimum number of miles on what I expected to find a dull affair, and finished up, after various test runs, with a more-than-200 miles’ week-end jaunt, with luggage, in hilly country, Cruising, to start with, at a meagre (?) 35mph, the little mount was finally driven mile after mile at a figure within one or two miles of its maximum, which was 48mph. I took it up freak hills, thrashed it in its intermediate gears, and entirely failed to make it turn a hair of one of its control cables. In every way it conformed, with its sound layout and smooth performance, to one’s idea of what a big machine in miniature should be. A petrol consumption of better than 110mpg was more than challenged by an oil consumption so small that a measured beaker was necessary for its calibration—something like 4,000mpg, as far as I can remember. Mechanical noises consisted of a faint middle-gear whine, a negligible primary chain swish, and the inevitable valve patter of the type. Mudguarding was sound, the standard legshields neither rattled nor got in the way of normal adjustments, and the whole machine, fully equipped, cost a good deal less than £30. When I remembered the slow and unreliable hacks on which I had expended any sum up to £50 six or seven years ago, I rather wished that I had been born that much later. In those days its tax would have been 30s a year, against the plain 15s for which we have to thank Viscount Snowden.

Then, too, there was no compulsory insurance; but all sensible riders insure the safety of other people, and it now costs somewhere between £1 and 30s a year to do this with a 150cc machine. Using those figures, allowing for a regular change of oil in the sump, and using the Technical Editor’s slide rule, I find that a 10,000-mile year, again excluding depreciation, comes to £11—a matter of ¼d per mile. The additional mileage which has been allowed, you see, removes any difference in running costs between this and the smaller machine. The racing machine I mentioned a little while back was of the 250cc size, and its maximum was rather better than 85mph, but it would be fairer to deal with the performance of a more normal and much less expensive machine of the same capacity. This had a toned-down ohv engine, but the fact that the make has done well in road racing proves that all the firm’s engines need not be toned down. How-ever, if I mentioned one interesting mechanical feature round which swings the rest of the design I should be giving away the identity of the machine. Two features stand out in my memory. One was its firm, ‘large machine’ steering and roadholding, and the other was its mechanical quietness. It sat on the road, in fact, a great deal more comfortably than most of the ‘large machines’, and was an almost ideal bicycle for long-distance touring on a light purse. Not only is its tax 30s and its insurance against third-party 40s at the most, but the petrol consumption tinder normal running conditions was better than 100mpg—in fact, 132mpg was obtained with a rather weak mixture on one occasion—and, the oil consumption, so far as could be me small mileage, and allowing a change every 1,000 miles, was 2,000mpg. Here we have a ‘per mile’ sum of ⅓d in a 15,000-mile year—and it would be easy enough to cover this distance on such a comfortable machine. The machine costs well below £35 in a fully equipped condition, so even the dreadful bogy of depreciation need not loom largely on the otherwise rosy horizon of a prospective rider. A checked maximum speed of 56mph was obtained on the level, but, more important, a cruising speed of 50mph could be held indefinitely, up hill and down dale. The engine pulled easily enough to cope with any main-road hill in top gear when the ignition control was used with discretion, and the low ratio of 18 to 1 put real trials hills on the map for the adventurous tourist. Its handling under trials conditions was perfectly straightforward, and, for that matter, a light machine, provided that its steering is faultless, is much more easily dealt with in most freak going, though weight and pulling power assist under certain conditions, notably in deep mud. There is no doubt at all that the present-day light-weight not only does its job thoroughly, but can give a performance that will surprise and convince the experienced rider of heavier metal. It is no longer to be regarded with polite amusement.

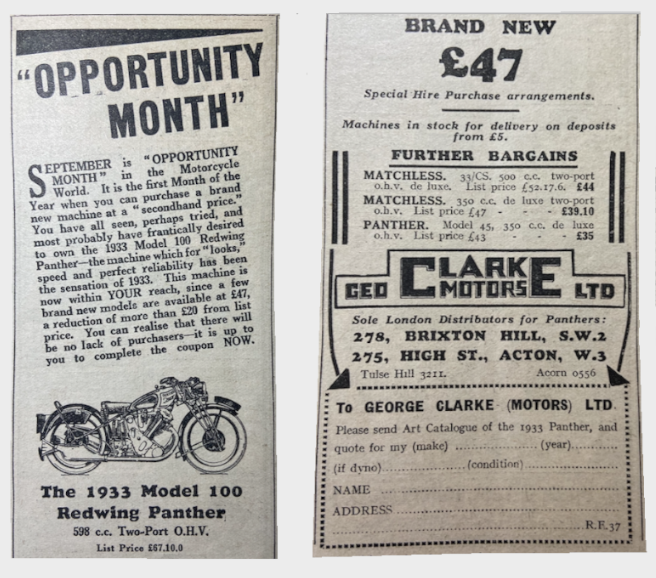

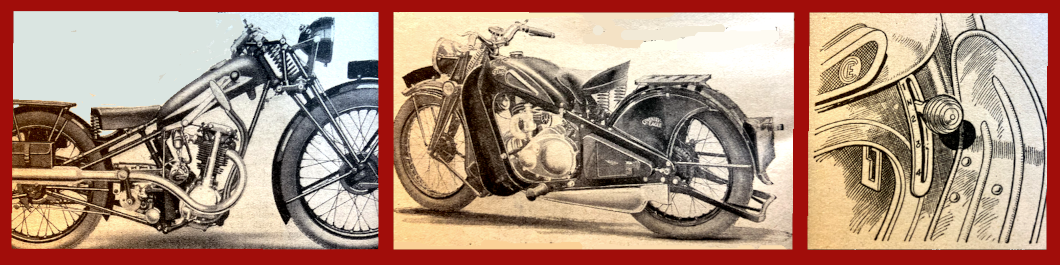

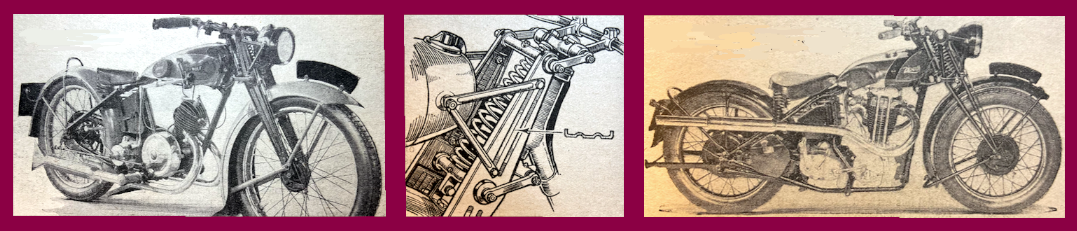

WITH UTILITY 350s TAXED AS heavily as luxury big twins demand rose for 250s while 350s were soon being sold off at knock-down prices. Price slashing was not so much the order of the day as the order of the decade.

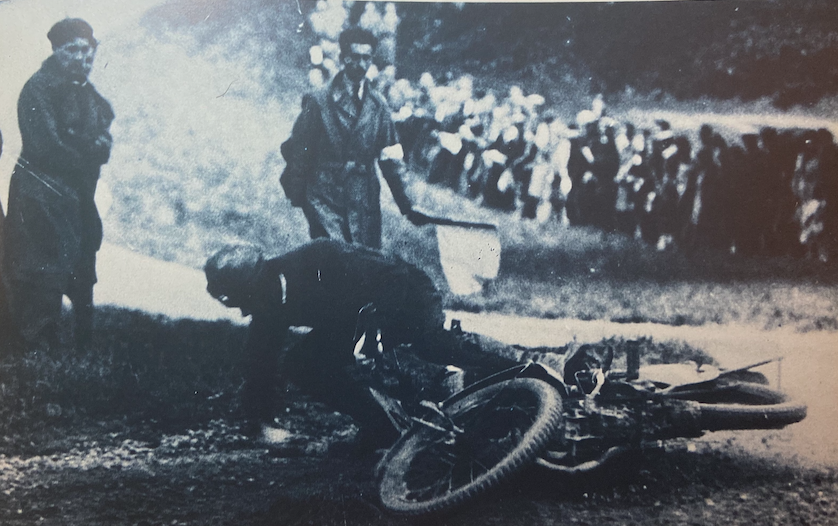

“LAST SATURDAY’S COLMORE TRIAL, organised by the Sutton Coldfield and North Birmingham AC (‘Sunbac’), the first open event of 1933, gives a splendid send-off to the open competition year. For the past two or three years the Colmore seemed to have settled in a groove and was, perhaps, in danger of losing some of its popularity. This year a great effort was made to provide something different, and the venture was an unqualified success. For some reason a new spirit surrounded the event; the atmosphere was changed—the sporting, rather than the serious, side was uppermost. Again, there was a new course. Very few of the competitors knew anything. about it, but they realised that it was going to be a little more difficult to keep a clean sheet, and they were all ‘on their toes’. Out of an entry of 76, only six riders, all on solo machines, completed the course without loss of marks, and, considering the nature of the new hills, these enthusiasts can congratulate themselves on their riding ability. Some of the hills were especially difficult for passenger machines, so, in dealing with the results, the stewards decided to disregard Camp Hill as far as sidecars were concerned, and Camp and Kineton hills for three-wheelers. There were several ‘Snowden’ models in the trial. They performed very creditably, and in some cases showed wonderful power, but none of them qualified for a first-class award. A 350 carried off the premier award and made the best solo performance—in the list of solo first-class awards, outside cup winners, 250, 350, and 500cc machines shared the honours evenly. Only one sidecar obtained a first-class award, and it was fitted with sidecar-wheel drive! The day previous to the event was a perfect example of early spring weather, and the Cotswolds were bathed in delightful sunshine. February, however, is notoriously fickle, and Saturday morning dawned upon ice-covered roads and snow-clad hill-tops. Had there been en early start conditions on the observed sections would have been easy, but by the time the hills were reached the sun had got to work and had succeeded in thawing out much of the frost. Although the riders were compelled to travel between tapes on Lark Stoke—the first hill—few

experienced any real difficulty, and all carried on gaily to the brake test. Here WT Tiffin (348cc Velocette) showed the best figure’ of merit—4,225. He was followed by LG Holdsworth (346cc New Imperial), with 4,230, and J Sinclair (498cc Calthorpe), 4,270. Of the sidecars, WS Waycott (352cc Velocette sc) was the best with 4,780, and DK Mansell (490cc Norton sc) next with 5,110. Fish Hill, the next test, was a new hill under an old name. It runs close to the main road hill of that name which rises from Broadway. First there was a 1 in 4 grass descent with a right-angle turn through a field gate, with both the descent and the turn observed; then a straightforward ‘stop-go’ test on a 1 in 4 track—an up-grade—with a hardish surface that included a tree root or two; next a leaf-strewn narrow track, and finally, a very snappy, taped-off left-hand hairpin. As a test of riding, ease of handling, and engine power, Fish Hill was really excellent. The fastest of all off the mark in the restarting test was Jack Williams, in 2.4sec, on his new love—a very ‘hot’ 348cc Norton. The 150s, as was to to be expected, found the task of restarting on so steep a gradient a tough proposition. S Jones (146cc New Imperial) had to to paddle his way out of the section, while LA Welch (148cc Francis-Barnett), who followed the copy-book and put his feet on the rests as soon as his clutch bit, came to a hurried stop which a little pedal assistance might have obviated. Another 150, a Triumph in the hands of T Robbins, got going well with the aid of a few lusty foot-slogs. Harsh throttle and clutch work caused WT Tiffen (348cc Velocette) to topple over. Then three perfect descents and ascents by RC Cotterell (348 Velocette), N Hooton (348cc Norton) and HJ Breach (348cc BSA). Both W E. Cook (249cc Rudge) and GF Povey (499cc BSA) snaked a bit, as they accelerated off the mark. The latter’s acceleration was magnificent, and so was that of AE Perrigo (348cc BSA), who blipped his throttle once to aid wheel grip. Quite one of the best of the small machines in the restart was the 148cc Francis-Barnett ridden by TG Meeten. With another 24cc, LH Vale-Onslow, on a water-cooled SOS, was also masterly. L Crisp (493cc Triumph) dropped down the slope with his back wheel locked, and, skidding round, nearly started going up again! Mounted on the make he is to ride in the Junior TT, HG Tyre11-Smith (348cc Velocette) made an excellent show, and so did another TT star, VN Brittain (Sunbeam). S Slader, on a 150cc Triumph, re-started in magnificent style. Another Triumph rider, JH Amott, on a 249cc model, was particularly good. The left-hand hairpin higher up caught a few, but the majority, like GE Rowley (496cc AJS), TF Hall (246cc Matchless), and AA Chinn (146cc New Imperial) took it in their stride. For sidecars and three-wheelers the re-start.test was a real problem. DK Mansell (490cc Norton sc) was using his sidecar-wheel drive, and, no doubt thinking of his clutch and the load on his transmission generally, got away gingerly and safely. One after another the sidecars

failed with wheelspin W Nichols (349cc SOS), GV Scott (348cc Velocette), RGJ Watson (498cc Ariel)…With bouncing, WS Waycott, on EF Cope’s Velocette outfit, all but got away. HS Perrey (493cc Triumph) stopped. RU Holoway (498cc Dunelt), however, managed it, and so did NP0 Bradley (599cc Sunbeam), who shot straight off the mark; they were far and away the best of the passenger-machine men, taking only 4.2sec. Great things were expected of GH Joynson (599cc Sunbeam), in view of his sidecar-wheel drive, but his engine momentarily lost its urge and he went down instead of up. For three-wheelers, too, wheelspin proved the stumbling block. Only GC Harris (1,096cc Morgan) succeeded—due not merely to twin rear tyres, which two others had, but also to using his throttle to perfection. Warren Hill was next, and proved rather troublesome. It winds through woods, has a mud-surface—not deep and a sharp bend at the foot and a considerable gradient subsequently. It was anything but easy, but L Heath 499cc Ariel) and G Stannard (493cc Triumph) did it without fault. A 246cc New Imperial was handled admirably by AR Foster, and AN Foster (346cc New Imperial) was even better. Yet another New Imperial (246cc) was ‘clean’, but its rider, S Rigby, had to call on all his skill in order to keep his feet up. New Imperials were much in the picture, for the, next faultless ascent was made by LG Holdsworth, on a 346cc model of that ilk, the ultimate winner of the Colmore Cup. Jack Williams (348cc Norton) was, perhaps, just a little better than anyone else at this point, and Tim Robbins, despite an absurd cap, took his 147cc Triumph up with just one little dig with his foot. WT Tiffen was quite ‘at home’ and rode splendidly, and FE Vigers (348cc Ariel) swerved about a lot, but got away with It. On a 246cc Matchless, FW Clark was another of the clever ones, while two more splendidly judged climbs were made by AE Perrigo (348cc BSA) and GF Povey (499cc BSA). After a long absence from competitions, HS Perrey (493cc Triumph sc) was as good as ever, and other successful passenger machines were those driven by RU Holoway (498cc Dunelt sc), WS Waycott (352cc Velocette sc) GC Harris (1,096cc Morgan), and SH Creed (1,096cc Morgan). Camp Hill, the next point, was much worse than it looked. It was very greasy and the two bends were difficult to negotiate. Perrigo and Povey took it in their stride; after that, one after another rider failed or only just managed to struggle to the top. Two perfectly outstanding efforts were made by KR Bott and GE Rowley on 495cc ‘Trophy’ model AJS machines. They swept up the hill, when it was in its worst state, in a manner that was a joy to behold. Another who appeared to be faultless was SH Goddard (249cc Excelsior); he cut the corner at the bottom—a quite legitimate act. Everybody thought he knew about Kineton. It turned out to be not the ‘old’ hill, but another just to the right, strewn with boulders and things. There were 12 clean solo climbs. They were made by L Heath, AR Foster, LG Holdsworth, RC

Cotterell, GF Povey, FE Vigers, D Cooper (344cc Excelsior), AE Perrigo, VN Brittain, L. Crisp, KH Bott and GE Rowley. DK Mansell, With his sidecar-wheel drive, was the only sidecar driver to get up without touching, and most of the other sidecars failed altogether. As already stated, the hill was ‘washed out’ for three-wheelers. Lower Guiting hill was hardly worth observing, but Gipsy Lane, near Winchcomb, was quite another story. The mud was just hard, chawed mud—so hard and so rutted, particularly towards the end, that the use of feet was definitely the better part of valour. Probably the but climb of the day was that of Rowley, who, not deigning to adopt the modern trials rider’s artifice—standing on the footrests—sat in the saddle and sped up the hill with hardly a wobble. Another star solo climb was that of Bott, who kept his feet up and corrected every plunge. For sidecars the hill was easy, and fast touring was the rule. W Nicholls (349cc SOS), L Simpson (497cc Ariel), and HS Perrey (493cc Triumph) were all particularly good; while WS Waycott (348cc Velocette) was outstanding, in that his gear jumped out and he got it back again before the outfit had time to do more than think about slowing! The driving chain for his sidecar wheel had disappeared from Joynson’s Sunbeam outfit; nevertheless, he was excellent over the worst part, though he found trouble—apparently the bank—higher up. NPO Bradley (599cc Sunbeam sc) had bad luck. He came to a hurried and momentary standstill as if a stone had caught in his driving chain. Good luck, on the other hand, favoured CS Rigby (493cc Sunbeam), who fouled both banks and yet got up non-stop. ‘Sawing’ on his steering wheel to aid the grip of his front wheels, GA Norchi (1,075cc BSA) made a fastish climb. H Laird (1,096cc Morgan), too, was excellent, leaping up the hill at speed and hopping to such an extent that his passenger pulled her woolly cap off for fear it would tumble overboard. Then came Mill Lane, once a terror, but on this occasion perfectly easy. West Down, too, was comparatively simple, and produced nothing really outstanding, apart from the spectacular manner in which Jack Williams and George Stannard extricated themselves from difficulties. The finish came at Winchcomb, where everybody declared that this had been the best Colmore for several years. Keep it up, Sunbac! Provisional Results: Colmore Cup (for best performance), LG Holdsworth (346cc New Imperial), marks lost, nil; figure of merit, 4,230. Cranmore Trophy (next best solo performance), J Williams (348cc Norton), nil, 4,315. JM Moxon Cup (best performance under 150cc), S Slader (147cc Triumph), 20, 5,300. Calthorpe Cup (best performance 150-250cc), AR Foster (246cc New Imperial), nil, 4,600. Norton Cup (best performance 250-350cc), AE Perrigo (348cc BSA), 4, 4,280. Kershaw Cup (best performance 350-500cc), GF Povey (499cc BSA), nil, 4,430. Watson Shield (best sidecar performance), RU Holoway (498cc Dunelt), 11, 5,950. Hassall Cup (best performance 350-500cc sidecar performance), WS Waycott (352cc Velocette), 16, 4,780. Carr Cup (best three-wheeler performance), GC Harris (1,096cc Morgan), 11, 4,950. Phosphor Bronze Team Prize, Sunbac 11, AE Perrigo, J Amott, LG Holdsworth.”

“ON THE COLMORE ON Saturday I ran across Graham Oates, who, while over in Manxland, his island home, had a look at the TT course to see if it was still there. Apparently it is, but with a difference—a big difference: the bend at the notorious thirty-third milestone is being altered and will be ten feet wider, while all the way from Windy Corner to Keppel Gate there are big ‘improvements’ afoot. These modifications which the Manx Highway Board makes year after year, while they may be improvements from the Island’s viewpoint, seem to me to take quite a lot of sting out of the TT course. As a result, one can never be sure how much of the speed increase in any one year is due to the machines being better and how much to the course having been made faster.”

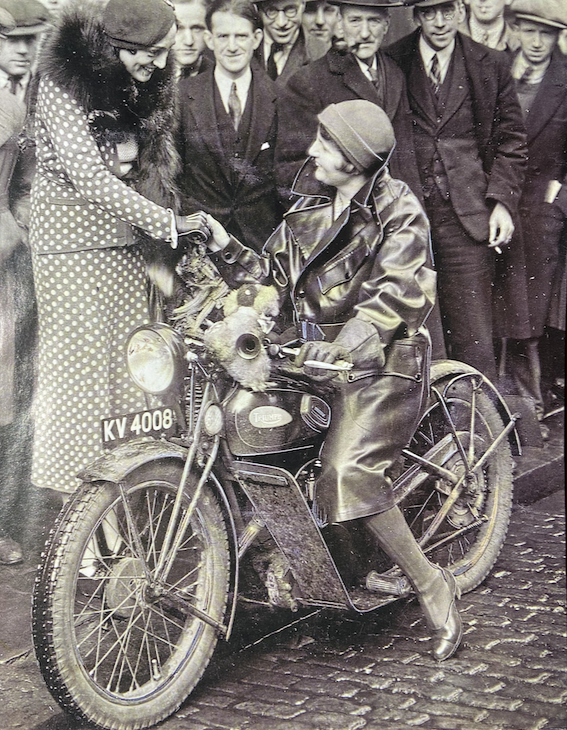

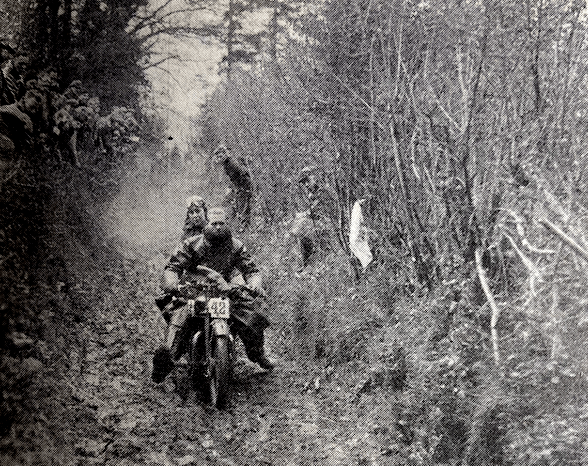

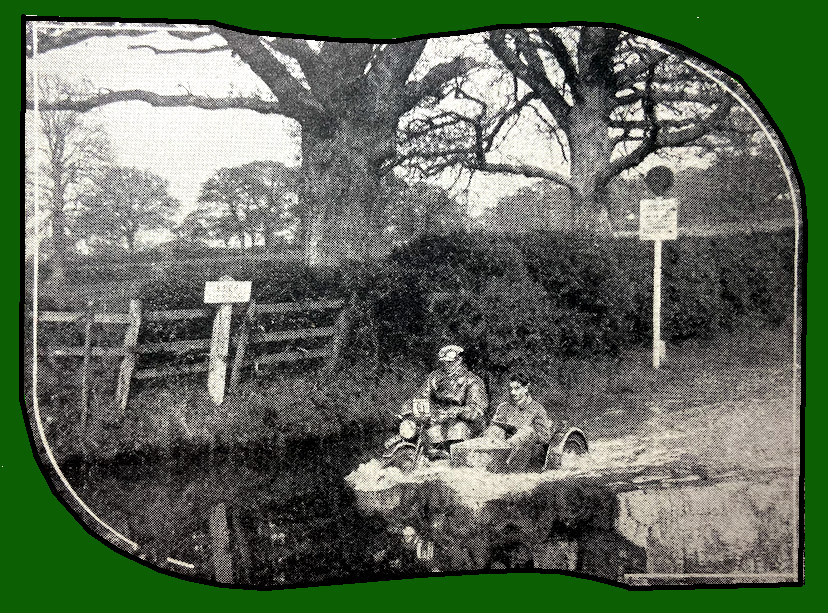

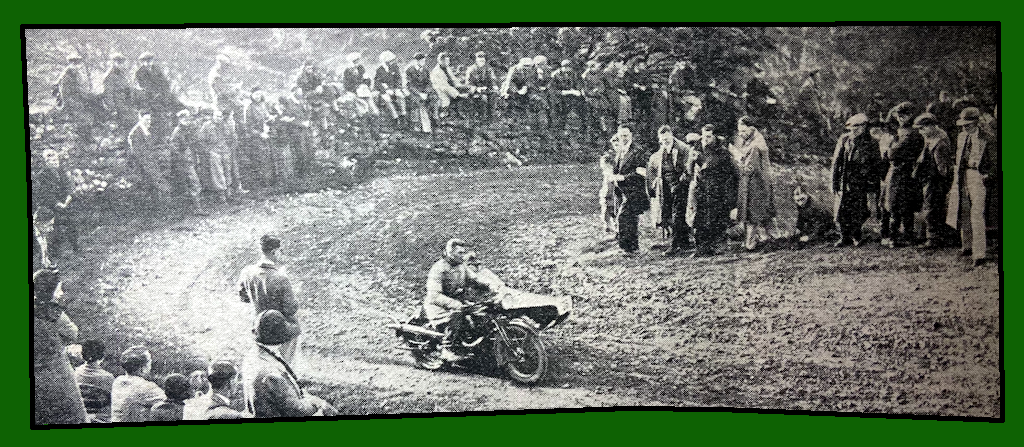

“THE VERY IDEA of plodding up a leaf-mould galley while hampered by a pillion passenger might horrify today’s trials riders; but in pre-WW2 days, one of the most popular events in the Surrey calendar was the Carshalton MCC’s annual Pillion Trial. The eighth trial in the annual series attracted a very good entry of 79—among them quite a few well-known names, such as Karl Pugh, Bernard Matterson, Mike Riley, Len Heath and Teresa Wallach. Starting at the Barley Mow, Betchworth—with the scars of the Box Hill quarries prominent in the background—the 49-mile route was laid in the Dorking-Guildford area. Because there had been no rain for several days beforehand, the course was ideal for pillion-trialling, though if the day had been wet there could have been much bother. Opening section was Goat Track, on the side of Box Hill, where a stop-and-restart test was held. Other hazards on the route card included Old Westcott, Oristan Lane, Prohibition Alley (sticky mud and a water-hole, where Len Heath’s 497 Ariel, and Mike Riley’s 498 Levis, were outstanding), then on to Buckshee, Last Straw and Coldharbour. Worst section of the day was Claypits, where the crowds lining the sides of the track were so thick (take that as meaning what you will) that competitors were forced to stick to the muddy slot in the middle. That led to a protest or two, and some riders were allowed a re-run. Overall winner was Len Heath, and although passengers’ names were not quoted in the programme, we do known that on this occasion (according to Motor Cycling’s report) the chap keeping the rear end of the machine down was KR Bott. The Carshalton Pillion Trial had been instituted as something of a propaganda exercise, to show that pillion riding, even under arduous conditions, was perfectly safe (a vociferous parliamentary lobby had been trying to get it banned). However, it would appear that 1935 was the last year the event was held; perhaps the Carshalton lads felt they had made their point.”—Bob Currie

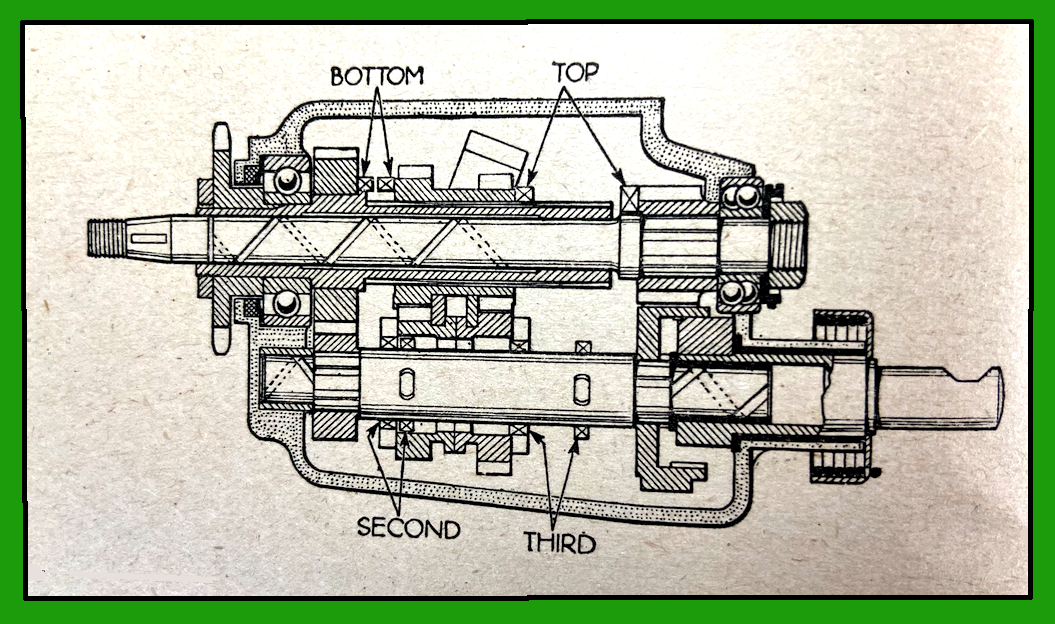

“IT IS NOW GENERALLY RECOGNISED that the lower-powered mounts need four speeds even more than do their more powerful brethren. To meet this need a new Albion lightweight four-speed gear box, suitable for use with engines up to 150cc, is to be marketed. The gears are of similar design to those in the heavier four-speed boxes, and the ratios are 1, 1.35, 1.8 and 2.9. The box is identical in size with the Albion lightweight three-speed box, except that it is ⅝in wider. Fitted with a single-plate clutch, the gear box weighs 12lb 10oz, top fitting. The Albion Engineering Co, of Tower Works, Upper Highgate Street, Birmingham, 12 are the makers.”

“OVER 600 MORE NEW motor cycles were registered last December than was the case a year before. The total number of machines registered for the first time in December was 2,428, as against 1,807. The total of 2,428 consisted of 1,089 under-224lb solos, 572 over-2241b solos, 276 machines of under 150cc, 20 under-224lb. sidecar outfits, 176 over-224lb. sidecars, two under-150cc sidecars, 292 three-wheelers and one motor-assisted pedal cycle. All told, 50,072 new motor cycles were registered in the whole of 1932. Of this 8,902 were under 150cc, 32,188 larger capacity solos, one a motor-assisted pedal cycle, 4,876 sidecars and 4,105 three-wheelers. The previous year the total was 52,562.”

“SEVERAL CHANGES IN DIRT-TRACK rules were decided upon at a recent meeting of the ACU Council. Like the already instituted clutch-start rule, they have as their aim the speeding-up of programmes. In the first place, a rider will not be allowed to change his machine for another once it is out on the track. A second new rule is that no restart will be allowed in match races if a rider falls or has machine trouble. The first rule, says the Union, will ensure that the rider gives proper attention to his machines in the paddock. The second cuts out the right that a rider had in previous seasons of claiming a restart if he fell or had mechanical trouble in the first lap of a match. It has been stated that the privilege has been very much abused, and it is felt that its elimination will not prove any hardship. Match races, incidentally, will be decided with a flying start, and not with a clutch start as in League races. Another new regulation empowers stewards to impound unsafe or ‘un-official’ crash helmets, with a view to preventing riders from using such helmets, once they have been banned, on other tracks in the hope that less observant stewards will not notice them. Helmets thus impounded may be destroyed with or without the consent of the owner.”

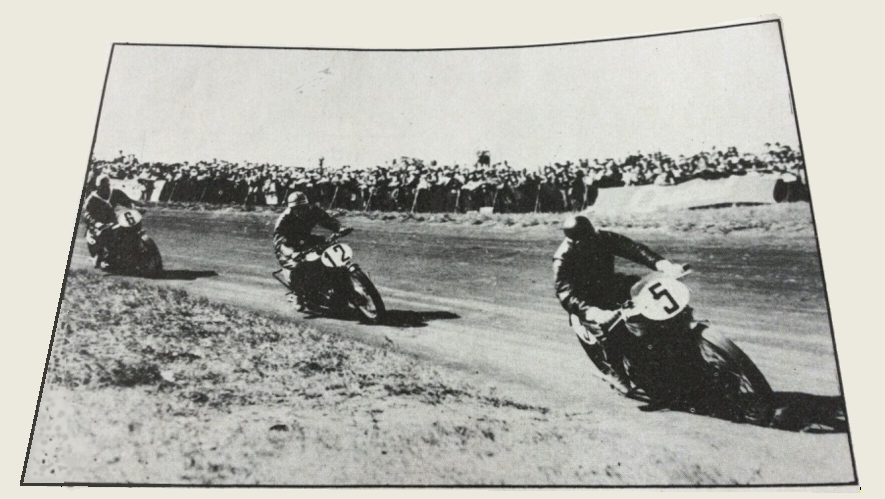

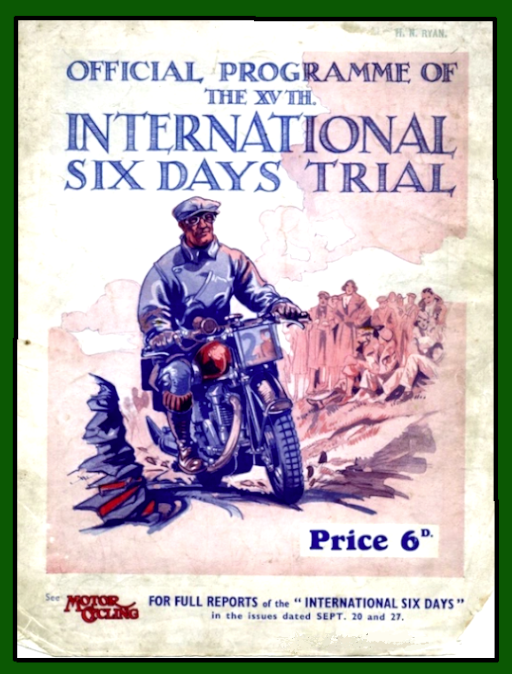

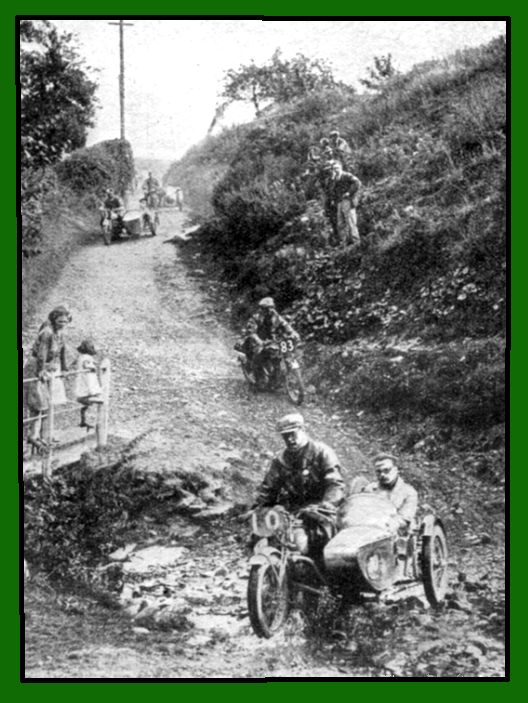

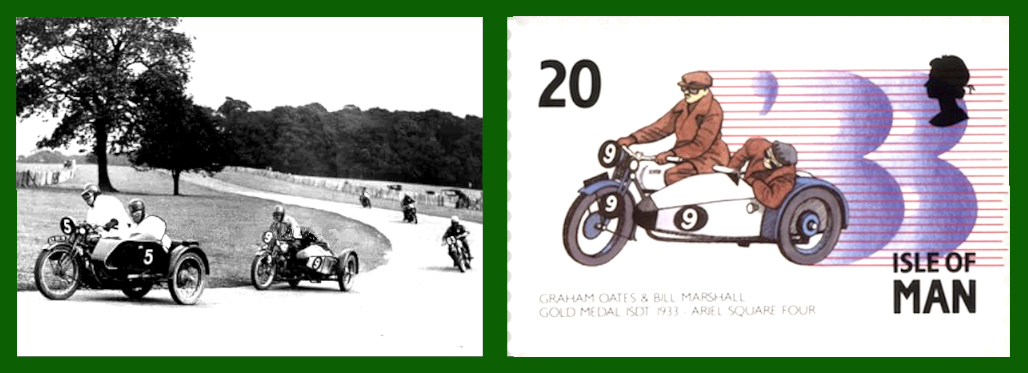

FRED CRANER, A GARAGE OWNER and secretary of the Derby &DMC, reckoned that the British mainland needed a full-sized race circuit to match the big Continental tracks. He got together with the owner of a private estate named Donington Park; they staged a series of races to try out a 2.19-mile circuit. Facilities were almost non-existent and the track was barely wide enough for combos (too narrow for cars) but riders and spectators flocked to Donington, encouraging the organisers to invest in it for the following season. Meanwhile, as you’ll see if you can be bothered to read through the year, Donington Park was used for the ISDT speed test—and a sidecar was named after it.

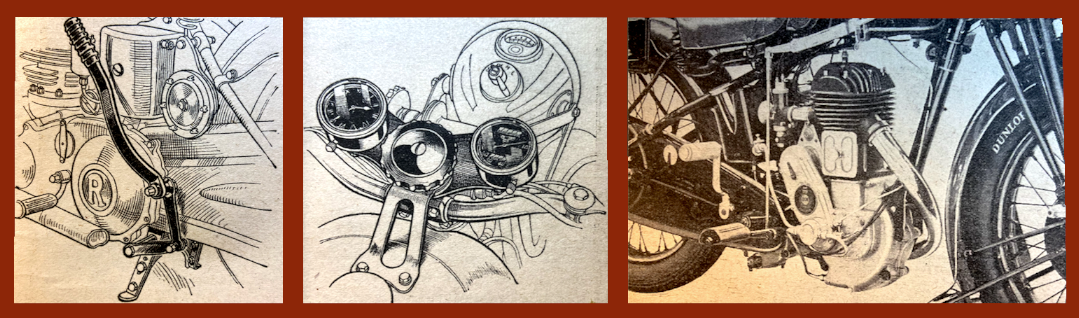

“LESSONS OF THE TT: How They Are Sometimes Lost, Not Upon the Manufacturer, but Upon the Ordinary Rider: Four days hence the first of the three TT Races will be held, with its tale of success, of defeat, and of ill-luck. In the brief span of a few hours designers will have their theories proved or disproved, and one and all will come back from the Isle of Man with fresh knowledge; but how much of this knowledge, an outside observer might ask, will be applied to the improvement of motor cycles? This side of the TT is liable to be overlooked. The Tourist Trophy provides such a great sporting week, and, for those with eyes to see, such a fine spectacle, that the true significance of the Races is sometimes missed. Each year there are lessons to be learned. Them are some which, we suggest, stare motor cyclists and designers in the face, yet are never fully heeded. Take, as an example, the foot gear change. This type of gear control is universal in the TT. In our experience with all types and makes of motor cycles it affords a quicker change and a better change, and, because both hands are retained upon the handlebars, it is altogether a safer method of control. Yet something like 90% of the motor cycles sold to-day are fitted with hand control. Why? Because the average motor cyclist is conservative—because, not having had lengthy experience of a foot change, he does not realise its several valuable advantages and prefers to keep to the type of control he knows. Then there is the question of tyre sizes. Every single rider in the TT uses a small-section front tyre because of the improved steering it affords. On all machines of the sports type there should be a similar arrangement. This is seldom the case.”

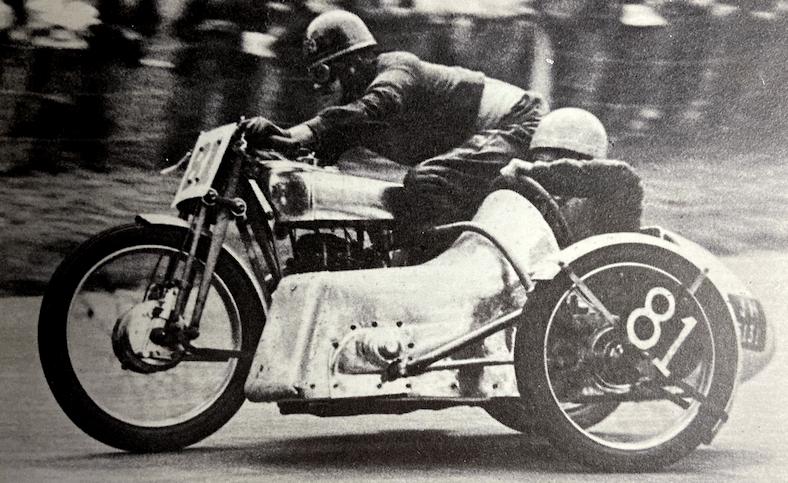

“I[XION] REGARD THE ABOLITION of the Sidecar TT as most unfortunate. The one serious drawback to motor cycling is its solitariness. Man is a gregarious animal. From 17 to 70 he is also an amorous animal. Limit him to two wheels, and you limit him to a pillion passenger. The range of the feminine pillion passenger is obstructed by the cost of silk stockings, and the publicity afforded by the pillion to serious ‘ladders’ in same. So the sidecar is the best solution for the motor cyclist who hates solitude, and who, for any reason, is not enthusiastic about pillions. But we are doing little or nothing to boost the sidecar; and I had hoped that an all-in sidecar and three-wheeler TT would fill the gap. Is it too late to suggest that during the Amateur GP week an event should be staged open to amateur-owned three-wheelers of all types, including Morgans, BSAs, Coventry Victors, and the like.”

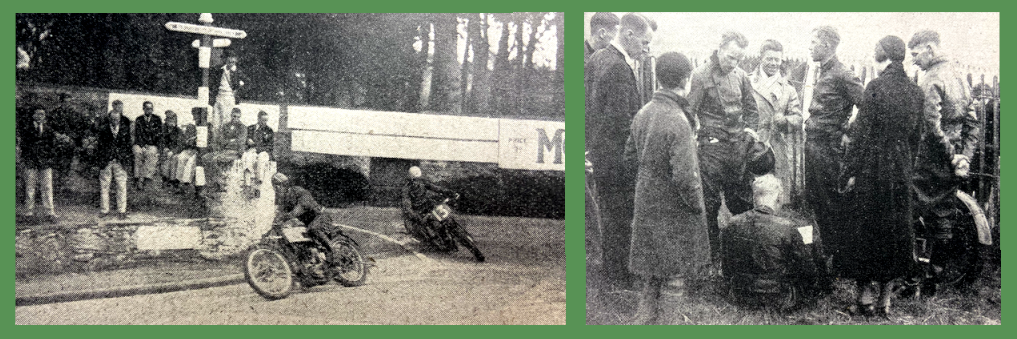

“DOUGLAS, FRIDAY, JUNE 2ND. Heavy rain, thick mist blanketing even Onchan Head, and something resembling a rough sea—one of those mornings when only someone with a job to do would turn out at 4am. There were 29 heroes out with their machines to see how well they had memorised corners they could not possibly see. Doing 90 into an impenetrable wall of mist is no sinecure. The fastest lap was 34min 41sec, done by local talent, to wit, that of WA Harding (Velocette). Perhaps he likes heavy rain, because be put in three laps while most people were more than content with one. His knowledge of the course must have helped him a whole lot, because, even up at Signpost Corner, the mist completely blotted out the bends in either direction. At this corner a little bunch of people waited with water running down their necks for the crackle of the first rider’s exhaust, and the Motor Cycle man wondered whether it wouldn’t be a good idea to purchase an editorial gamp for this sort of thing. [‘Gamp’ was slang for ‘umbrella’, inspired by the Dickens character Sairey Gamp, a drunken nurse who invariably carried an umbrella.] At 5.15 the first man, Pringle

(Junior Norton), came through, looking miserable. No excitement followed—just a steady stream of hunched-up riders waiting for the tricky bits to loom up and thinking of hot drinks to be dispensed by Mr. Dunlop or Mr Cadbury. Even Wal Handley slowed right up as if to read the signpost, looked as if he was going to visit Onchan Village, and then suddenly swung his Velocette round. CS Barrow was out on his first conducted four with the Mechanical Marvel, the new Excelsior, and it certainly sounded terrifically hot. The Jawa camp was the only one out in force—Ginger Wood going quite quickly, Brand, who is getting to know his kinks, and Tommy Spann of the wasp jersey. George Patchett handed in his checks at Ballacraine and one can hardly blame him—it was horrid. Even if Van Hamersveld is not placed he and his mechanic deserve very special praise for the incredible tidiness of their small depot. Every spanner is hung on its own nail and all the bits are laid out on clean paper to await use. The Eysink machine is of conventional but clean design, has nice lines and is powered with a Python engine driving through an Albion gear box. Van Hamersveld has done great work in Holland, but he has still to learn the Manx course and is taking things sensibly. Regrettably The Motor Cycle man over-slept to the extent of half an hour, and reached the Craig with his stop-watch after ten racers had

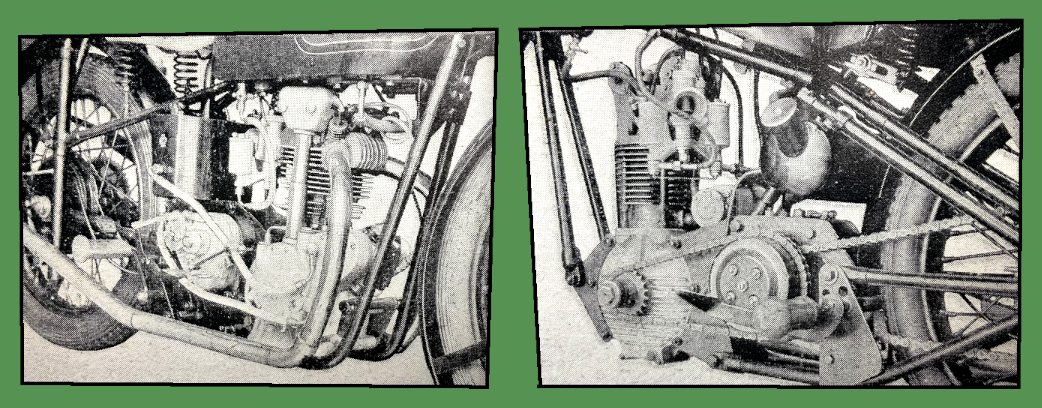

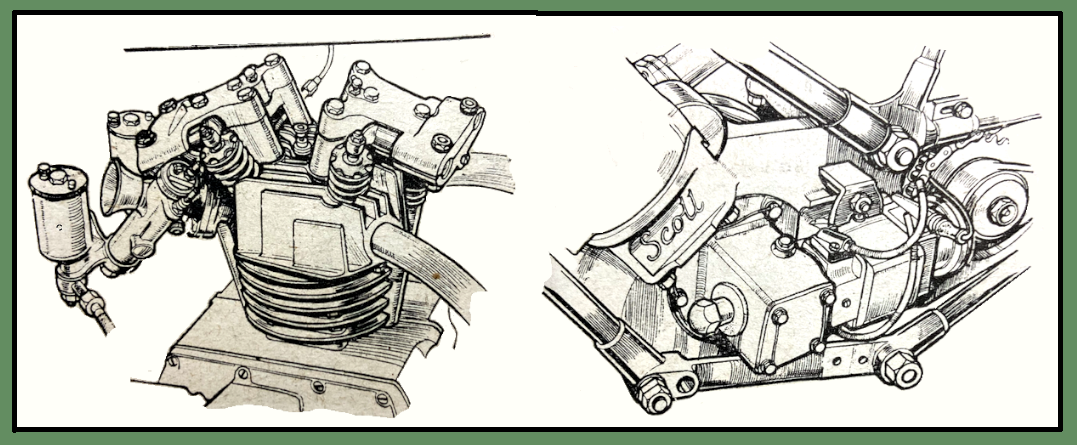

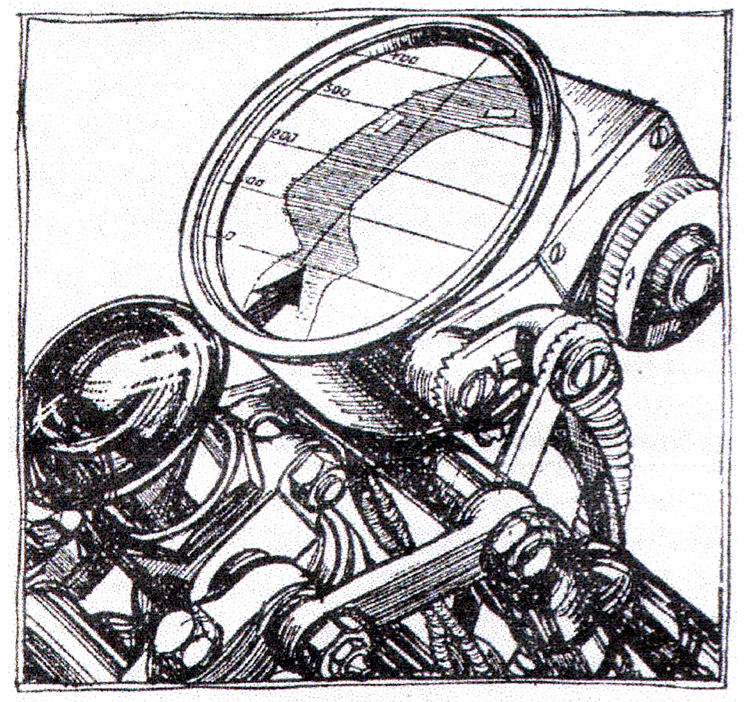

rattled by. The ends of the two straights could just be seen and he amused himself by taking a few times from the top to the bend. The sole representative of that famous breed of twin two-strokes that has made Manx history in past years is TL Hatch’s Reynolds Special. The frame, which, of course, is of the duplex triangulated type, has been strengthened and modified to give better weight distribution having regard to the amount of petrol to be carried—very nearly five gallons. Improvements have also been made in construction of the radiator, which has a larger cooling area and incorporates a steam valve; the latter enables the engine to run at a higher temperature and conserves the water supply. A striking feature is the enormous petrol and oil tanks; the former, as indicated above, carries 4⅞ gallons, and the latter 1⅓ gallons. The power unit has been considerably redesigned, as a result of intensive experimental work. An Elektron crank case is employed, differing considerably from the usual construction, and employing larger diameter bearings. Scott owners will also be interested to note that in the new design the cranks are a parallel fit in the flywheel instead of a taper, and that the familiar crank case doors have been replaced by the new Scott multiple-plunger (swash-plate-operated) type of oil pump on the right side and a magneto-drive housing on the left-hand side. This arrangement allows the magneto to be bevel driven from the engine, and dispenses with the usual driving chain. Included in the magneto drive is a neat revolution counter.”

“THE COURSE—264 miles 300 yards is the official length of the course in all three races, Junior, Lightweight, and Senior. The world-famous and gruelling Isle of Man circuit is lapped seven times, each lap being 37 miles 1,300 yards.”

“THE AWARDS—First Prize: The entrant of the wining machine will receive the Tourist Trophy (Junior, Lightweight, or Senior) and a cash award of £200. Second Prize: To the entrant, a cash award of £125. Third Prize: To the entrant, a cash award of £100. Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Prizes: The entrants will receive, respectively, cash awards of £75, £60, and £45. Finishers: Each finisher, other than the above, who completes the course within a time not exceeding that of the winner by more than one-eighth, receives £10. Replicas of the Trophy will be awarded in each race to every entrant winning an award.”

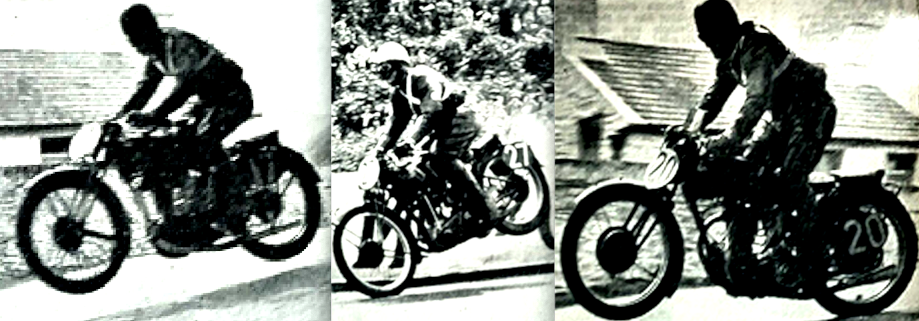

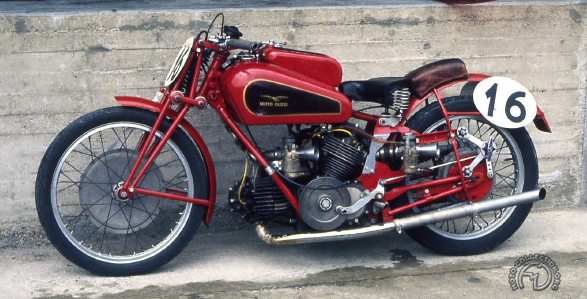

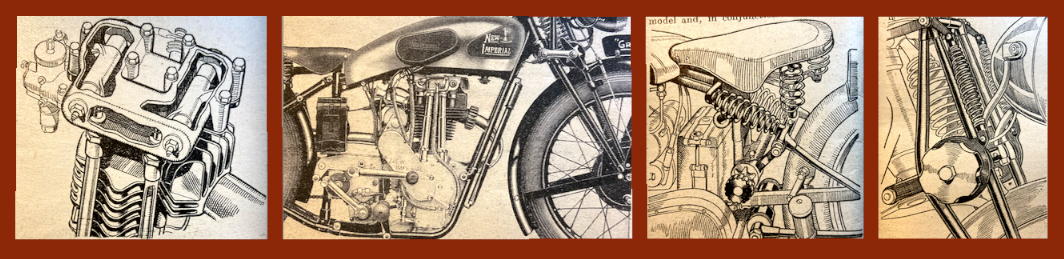

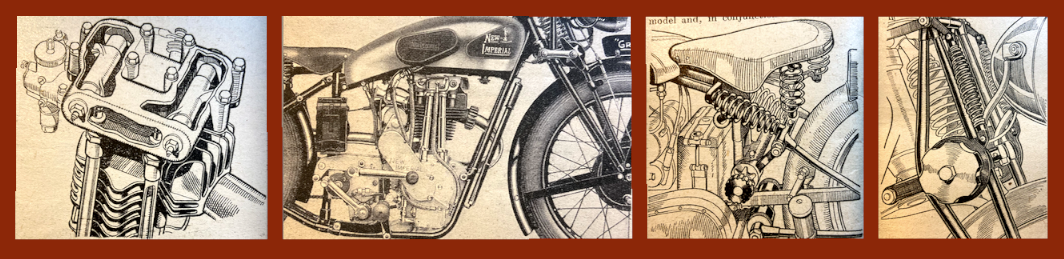

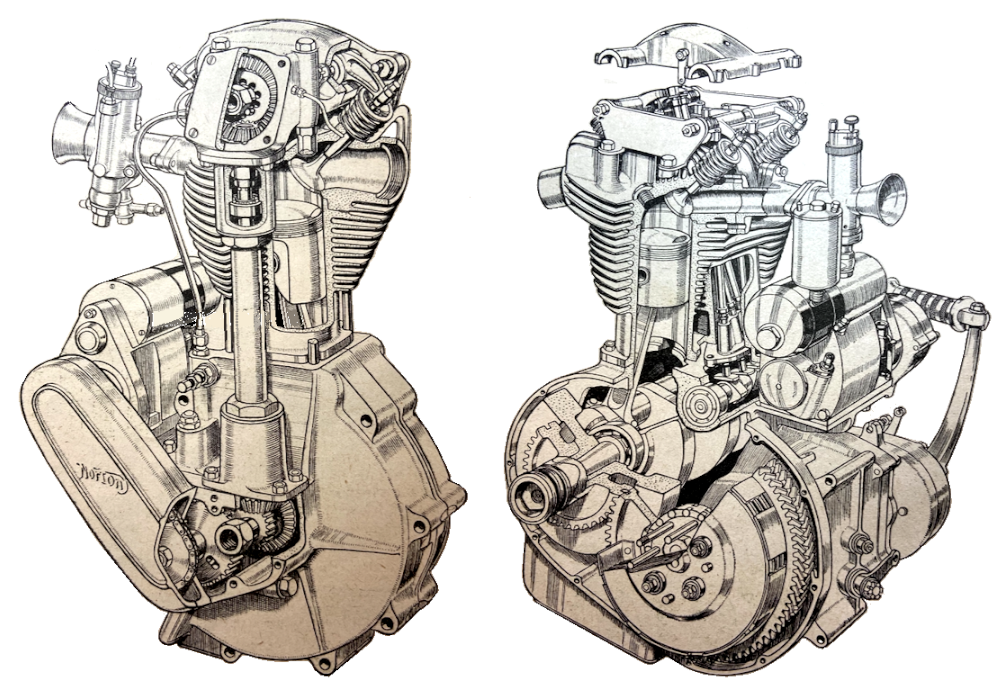

NOT FOR THE FIRST TIME in this timeline I am indebted to Geoffrey Davison, editor of the TT Special, and a TT rider of some note, for details of race week. In this case his report is a model of concision: “Nortons definitely had it all their own way in 1933, Stanley Woods winning both Junior and Senior for the second year in succession, backed up by Hunt and Guthrie in the Junior race and Simpson and Hunt in the Senior. Stanley’s average speed for the latter event was 81.04mph, the first time the race had been won at over the 80 mark. He led all the way through in each race and it seemed that this brilliant Irishman was invincible. The amazing thing, too, was that he never seemed in such a frantic hurry as most of the others—he just went round and round, getting faster and faster and winning all the time! An interesting feature of the Junior race was the strong entry of Velocettes. Whereas previously this event had been a Norton-Rudge duel, this year Velocettes took the place of Rudges. There was, indeed, only one Rudge finisher—Fernando Aranda, from Spain—but after the winning Norton trio came seven Velocettes [Velos finished 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 13th, 14th, 15th and 16th—Ed]—no mean demonstration of reliability. As in the previous year, the Lightweight event was much more ‘anybody’s race’. Excelsiors, New Imperials, Cottons and Rudges all had a go, with Wal Handley and Sid Gleave now riding Excelsiors. Walter led on the first lap—I almost wrote ‘of course'”—but Sid Gleave overtook him in the next lap and led from then onwards to the finish. The race was marred by the death of Frank Longman, winner of the 1928 Lightweight, who crashed near Ramsey.” RESULTS Junior: 1, Stanley Woods (Norton) 78.08mph; 2, Tim Hunt (Norton); 3, Jimmy Guthrie (Norton); 4, AG Mitchell (Velocette); 5, HGTyrell Smith (Velocette); 6, GL Emery (Velocette); 7, Wal L Handley (Velocette); 8, HE Newman (Velocette); 9, D Hall (Velocette); 10, ER Thomas (Velocette). Lightweight: 1, Sid Gleave (Excelsior) 71.59mph; 2, Charlie Dodson (New Imperial); 3, Charlie H Manders (Rudge) 4, Leo Davenport (New Imperial); 5, Syd A Crabtree (Excelsior); 6, M Ghersi (Moto Guzzi); 7, Ted Mellors (New Imperial); 8, Les Martin (Rudge); 9, CB Taylor (OK-Supreme); 10, DS Fairweather (Cotton). Senior: 1, Stanley Woods (Norton) 81.04mph; 2, Jimmy Simpson (Norton); 3, Tim Hunt (Norton); 4, Jimmy Guthrie (Norton); 5, Ernie Nott (Rudge); 6, AG Mitchell (Velocette); 7, JG Duncan (Cotton); 8, Ginger Wood (Jawa); 9, HG Tyrell Smith (Rudge; 10, J Williams (Norton).

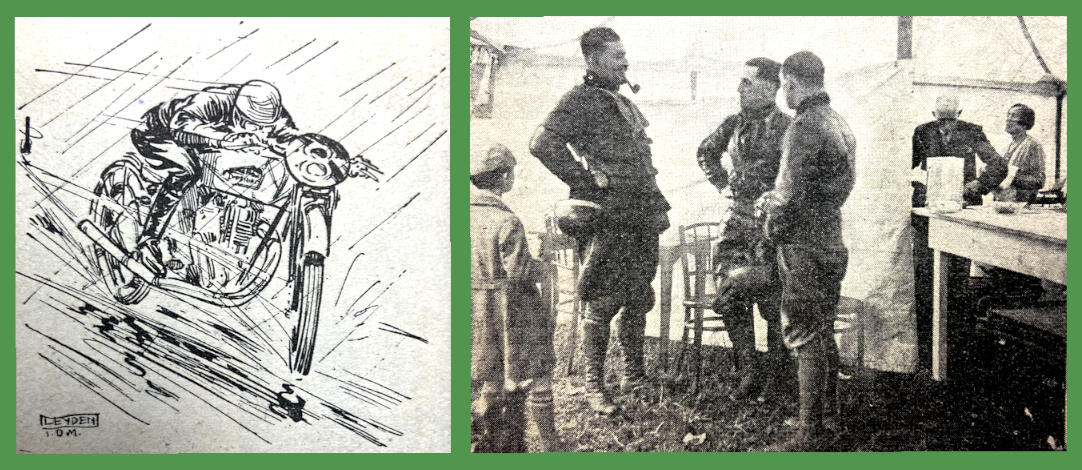

MOTOR CYCLING’S MAN ON THE ISLAND turned his purple-prose knob up to 11—these excerpts from the Green ‘Un’s reports of the Senior and Lightweight races are a joy: “The fingers of a watch pointed to 11 hours, 14 minutes, and 30 seconds. A man said, without too much enthusiasm, without much excitement, without much interest, even, just one word: ‘Right!’ The motorcycle, which was labelled ’29’, was put forward a few paces, the engine fired, and a valuable piece of machinery weighing a couple of hundredweight and more, went roaring away towards Bray Hill. Crouching over its tank was Stanley Woods, 28, red-faced, curly haired, Irish. He had set out grimly, purposefully, to travel over 264 miles, 300 yards of Manx roads in less time than any other man would need…And he succeeded. No man of the 29 there present, pick of the world road-racing stars, could overtake him; of the motorcycles they rode, none could approach his Norton. And so he rode for seven laps of that terrible Manx course, always leading, the despair of those behind. Of these none challenged his Norton with such measure of partial success as the other riders of the same brand. A Norton led, a Norton was second, a Norton was third and (from the second lap onwards) a Norton was fourth throughout the race. Of such ingredients, a thrilling contest is not made. At least it would appear not. But stay. Forget, for a moment, the machines, and think of the man who is/them. Think of JH Simpson—hard luck Jimmie as they call him, lean-faced victim of so many of the Wheel of Fortune’s sideslips, breaker of many a record lap-speed, winner of never a TT race.

Think of him, the disappointed, the determined, the dauntless, and the dashing, hanging as close as he might tot he Irishman’s tail for seven full laps, always striving to go faster…never succeeding. Once he had thought he had Woods beaten, for he broke the lap record. But Woods broke it again. Once Simpson was only 16 seconds behind Woods; he could not better that. When there was Guthrie, James o’ that ilk, a dour Scott. Winner of third place in the Junior, he remained in the same position throughout six of the seven laps, only to drop to fourth place on the last lap of all. And the man who stole Guthrie’s third place from him: Percy Hunt, called Tim, for some odd reason. Tim made a bad start; he had to change the plug when the race was only a few seconds old! And then he rode like mad, annexing fourth place on the second lap and holding it until the last lap of all, when he forged ahead of Guthrie! Of a truth, we must think of Friday’s race as a battle of men, rather than of the machines. From such a viewpoint it was an exciting race; from any other angle it was—a mere procession. As anticipated, Wednesday’s Lightweight race proved exceedingly interesting. There was a battle royal between S Gleave (Excelsior) and CJP Dodson (New Imperial) for first place. At the finish the former, who had led since the second lap, was 2min 26sec ahead of his rival. He averaged 71.50mph and beat Leo Davenport’s 1933 record made on his New Imperial by exactly 2¼min. Dodson also bettered last year‘s figures. WL Handley (Excelsior), who’s terrific scrap with Dodson, for second place was a feature of the race, was unfortunate enough to retire with engine trouble on the last lap. He it was who set the pace on the first circuit. Another make–Rudge–occupied the third place. It was piloted by the Irishman CH Manders, a performance which is all the more creditable when it is realised that his was entirely a lone-hand effort, without works support. New Imperial, and Excelsior machines occupied the next two places, with Mario Ghersi, the Italian challenger, on the Guzzi, a plucky sixth.

The other six trophy replicas were divided between New Imperial, Rudge, Okay-Supreme, and Cotton. The last mentioned make had been well in the picture until JG Duncan retired with engine trouble. The New Imperial Trio carried off the Manufacturer’s Team prize, but Handley‘s record lap, made 12 months ago on his Rudge, remained unbeaten, perhaps, because of a strong breeze. The day, which had been dull in its early stages, soon cleared and a warm sun shone in a blue sky. A fatal accident marred the day. Frank Longman, riding a somewhat old Excelsior, broke his forks when descending Bray Hill on his second lap. He stopped for 20 minutes at Braddan and effected a temporary repair, pluckily, refusing to withdraw. He told an onlooker that the forks were not safe for high speeds and so he was presumably riding at a reasonable speed when he crashed at Glen Tramon, on the road to Ramsey. Although he was rushed to Ramsey hospital, he succumbed to his injuries—a fractured spine—within a short time. Longman, who leaves a wife and two children, was a veteran racing man, having frequently ridden at Brooklands, on the Continent, and in the TT, winning the lightweight event in 1928. He has been closely connected with the trade in Ealing for some years. This death was the result of a gallant attempt to finish on a partly disabled machine. Extraordinary scenes were witnessed at the conclusion of the race, when the A-CU’s organisation for once slipped up badly. Nearly half an hour before the official time for the termination of the race a road opening car came from Craig-ny-Baa to just short of the timekeeper’s box. Smart work to some extent stopped the crowd on the grandstands and Governor’s Bridge from overflowing on the road, but three men had to finish on roads officially open to the public. Nor is this all, for at approximately 3:40pm Crash! Went the maroons and quite a thousand people must have been strolling about the finishing straight when Tommy Span (New Imperial), the last man on the course, arrived! It was a truly amazing spectacle to see a man finishing a TT race well within time yet having to force his way through crowds of spectators. Somebody had blundered badly.

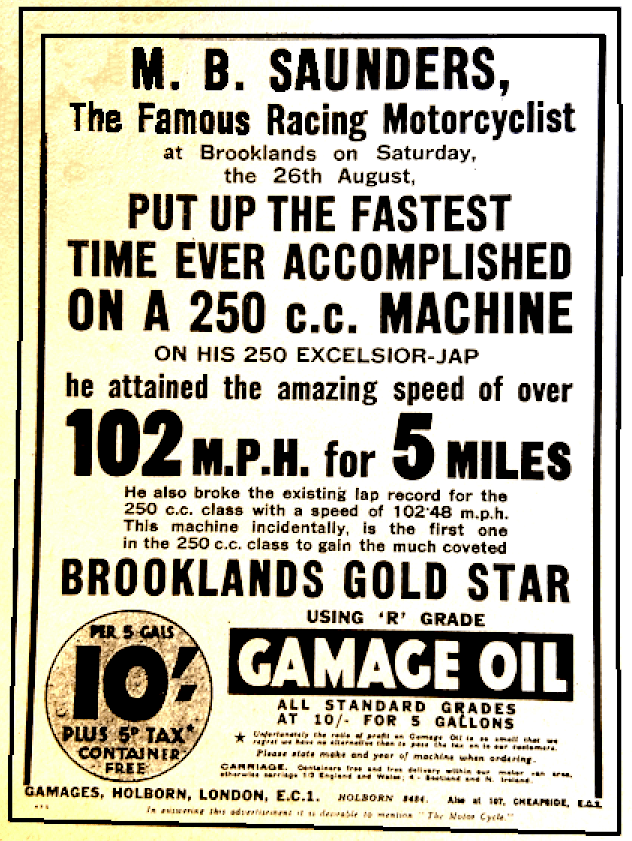

FOLLOWING VELOCETTE’S IMPRESSIVE showing in the Junior TT Les Archer rode one to victory in the Brooklands Hutchinson 100 at an average 100.6mph; the first time 350 to cover 100 miles in an hour in Britain.

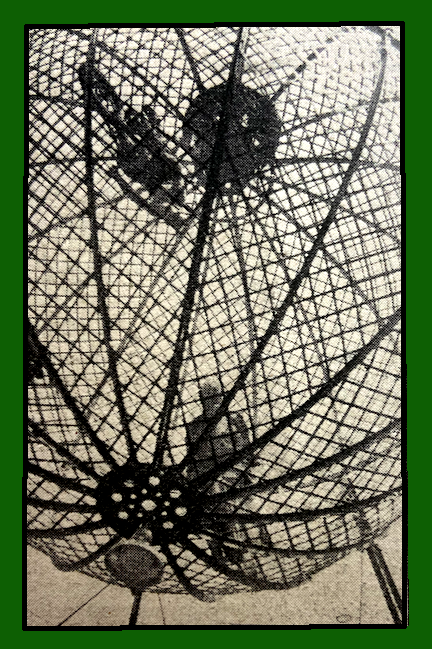

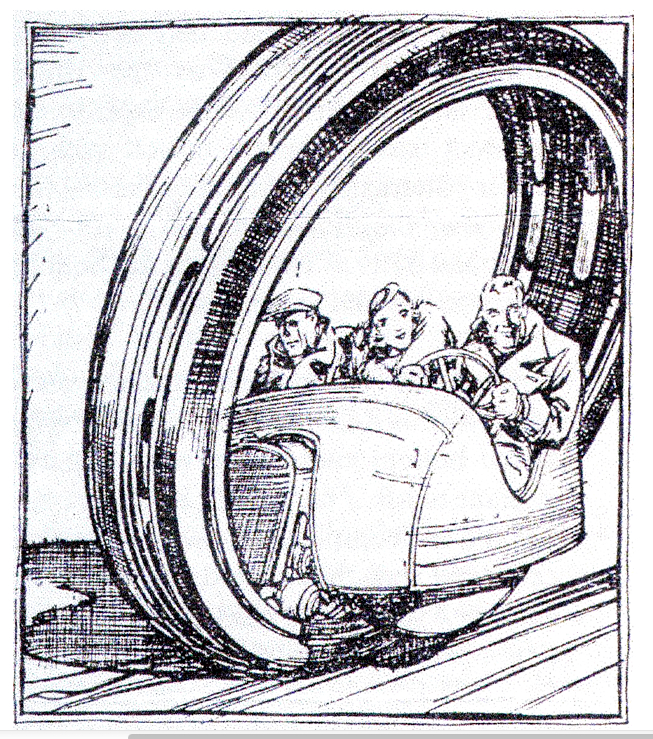

ALSO LAPPING BROOKLANDS THAT YEAR was the Dynasphere monowheel, built by Douglas (who contributed a 500cc flat-twin) lump and the British Aluminium Co to the design of Dr John Archibald Purves, who claimed it was the “high speed vehicle of the future”. What about visibility? “The solid portions of the lattice work spherical shell pass before the eyes so fast that they become invisible,” he claimed. “Only the picture of the country in front affects the eye.” Its commercial failure, according to Popular Science magazine, was a tendency to ‘gerbiling’—passengers sometimes spun inside the wheel when braking or accelerating.

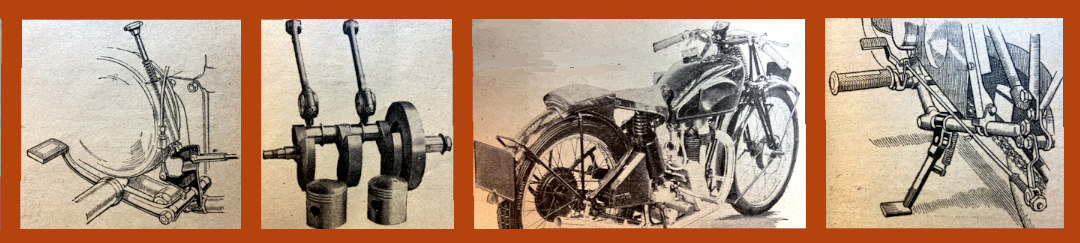

“DURING THE LAST YEAR or two a big improvement has been noticeable in the important feature of accessibility and ease of adjustment. Many machines of the 1926-1930 era were very bad in this respect, but since that time great strides have been made. We would, however, urge manufacturers to continue the good work, while there is time, in the production of their 1934 models. There is still room for improvement, particularly in lower-priced machines, on which one bolt or similar fitting is often made to serve a variety of purposes; there are still too many mounts on which half a dozen parts have to be dismantled or removed before one part can be reached. Particularly is this true of primary chain cases. Bearing in mind that nowadays almost all motor cyclists do their own maintenance work, designers might do worse than to hand over to a non-expert a new model equipped with only the standard tool-kit, and make a study of the time and trouble he expends in dismantling and assembling various parts.”

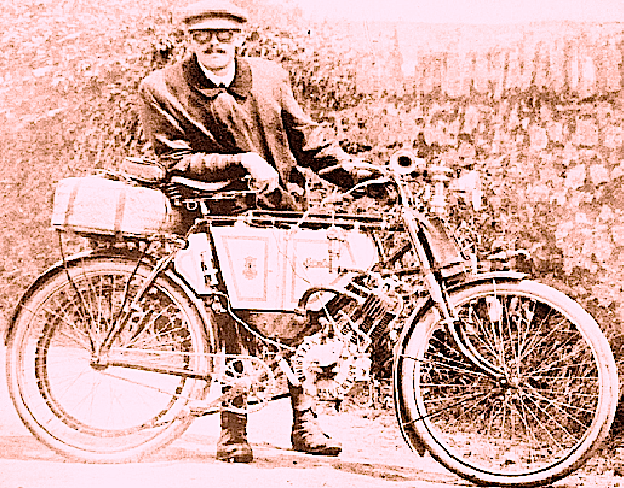

“THIS YEAR’S PIONEER RUN (‘ motor cycle old crocks’ run’) of the Sunbeam MCC has attracted over 50 entries. The oldest machines include WT Mansbridge’s 1898 149cc Werner, which has front-wheel drive—and twist-grip control! It is alleged to have acted as a stop-gap in a hedge since 1922.”

“A THOUSAND MILLION gallons of petrol were used in this country during 1932. Petrol is consumed in Great Britain at the rate of 30 gallons a second, day and night. Its cost is 2½d a lb, of which 1d. represents taxation.”

“GREAT ADVANCES ARE BEING made in the treatment of coal for the production of oils and petrol. Hydrogenation and low-temperature carbonisation will be very much in the public eye in the ensuing months.”

“AN IRON COMPOUND is, it is reported, being used successfully on the Continent as an anti-detonating agent for fuels.”

“DESPITE THE FACT THAT whole sections of the concrete have been relaid in an endeavour to eradicate it, the ‘Birkin Bump’ under the Members’ Bridge at Brooklands is still very much in evidence, according

to a rider who has sampled the track on a fast 500.”

“OF THE 5,876 MOTOR CYCLES imported into Holland during 1932 no fewer than 3,937, or over 67&, are credited to the United Kingdom, as against 958 to Germany, 396 to Belgium, 311 to the United States, and 223 to France.”

“THE SOLO MACHINES WHICH took part in the recent Bavarian winter trial—which involved climbs of mountain roads deep in snow—were fitted with a ski on each side.”

“‘ROADCRAFT’—WHAT IS IT? ‘Ambleside’ Explains How and Why it is Road-sense plus a Little Something Else…

One thousand eight hundred women are killed in this countspery every year by falling downstairs and by tripping over buckets and broom handles. This startling disclosure was made by Miss Margaret Bondfield, an ex-Cabinet Minister, at the National Safety Congress last year. But that is not all. It was also announced that 2,000 children are killed in their homes every year through similar accidents. This makes very startling reading; in my view it also has a very significant bearing on the fact that road deaths occur almost every hour of the day. If 10 people lose their lives every day while still in their homes, obviously through carelessness or forgetfulness in the majority of cases, how many thousands of similarly negligent individuals are abroad on our pavements and roads? I ask this question because I am certain that well over 90% of the accidents and tragedies that occur on the roads of to-day are due to sheer carelessness, either on the part of the pedestrian or of the motorist (ourselves included). Over 98% of the fatal road accidents which occurred in England and Wales during two months of last year were classified as avoidable. You will see that I am not going to blame the much-maligned pedestrian by himself, for we who are motor cyclists are all basically pedestrians, though with the advantage of a little knowledge of road traffic and its ways. In spite of this knowledge, most of us have experienced a little draught behind the ears when we have suddenly found ourselves ‘jay-walking’ across a busy street

or crossing. Bearing this in mind, how can we blame those who are unable to enjoy the open road in the way that we can? The pedestrian proper never has the same chance to acquire that mysterious quality commonly known as ‘road-sense’. If he had, then I am convinced that the toll of the road would be more than halved. However, since we must accept the position as it is, what can we do to minimise the accidents which do occur? I have just mentioned the term ‘road-sense’. I look upon it as a misnomer, for to me it suggests a kind of sixth sense—something which is born in an individual and not bred. So I prefer the word ‘roadcraft’, for it implies an art or a craft which can be learnt, pride being taken in its very learning. It is in roadcraft that I believe we have the solution of the tragic accident problem. If we—and I include pedestrians as well—were all experts in the art of road-craft, then accidents would be reduced by at least 50%. How can we learn? To begin with, each of us most be something of a psychologist; we must be able to understand the way most people react in moments of emergency. Does this seem very ‘deep’? Let me give a common example. If two people are walking across a road arm in arm, and perhaps talking, and they are suddenly taken unaware by a motor vehicle, what will they do? I can guarantee that, in the large majority of cases, they will immediately separate; one will perhaps stay where he is, while the other will dive for the nearest pavement. In any case they will both ‘fill’ the road. Why is this? The reason, I suppose, is the automatic reaction to Nature’s law of every man for himself. Together they are liable to obstruct one another, so they naturally separate. Yet, had they not been surprised, they would have walked across as they had started. Obviously, the good rider or driver, in such circumstances, takes every precaution to prevent the element of surprise. By that I mean that he does not sound his horn if he is less than 20 yards away. As trouble is to be expected he uses his brakes instead. In other words, the good rider, using his knowledge roadcraft, has anticipated trouble before it has overtaken him. Here is another little example which I witnessed only the other day while riding in London. About 100 yards ahead, on the near-side kerb, was a middle-aged woman, surrounded by children. Judging by her agitation I presumed she was about to cross the road. The only other traffic was a lorry approaching from the opposite direction. The woman took a hasty glance in my direction and then looked to her left to study the slow progress of the lorry, which was at least 50 yards away. Then, never for a moment realising that by that time I would be in danger of hitting them, she pushed the children in front of her and dived for the other side, still worrying about the lorry. But experience had taught me that the average pedestrian concentrates too much on a slow-moving vehicle, usually on his left, to be able to realise the difficulty in estimating the speed of a vehicle approaching from his right. In fact, they normally ignore traffic coming from this direction, perhaps because the almost dead-ahead view of such vehicles does not give any true idea of their speed of approach. The foregoing remarks apply to only one branch of roadcraft as I like to see it. We all know that a moving shadow behind a stationary vehicle usually indicates that some careless individual is about to dash across the road without dreaming to look out for approaching traffic. But do see all realise the significance of the local delivery van which shows signs of slowing up in the middle of the road? Having been once ‘bitten’, I always regard such vehicles with the gravest suspicion. To the uninitiated I would offer the suggestion that this slowing-up is an indication that the vehicle is going to turn suddenly down a road on his off side,

and therefore it is highly dangerous to overtake in the circumstances. It is of no avail to sound one’s horn, as the driver is in all probability doing the same thing and will not hear yours. Incidentally, he usually pokes a couple of fingers out of the side of his cab the moment he begins to turn. Upbraid him afterwards, and he will smilingly reply that he put his hand out and blew his horn—little consolation for the hectic moments that one has suffered! If you are travelling along one of the main roads to the coast at night and the road surface gradually becomes worse and worse it is often an indication that the surface is being attended to a little farther on, so look out for a violent bump as the road level goes up three or four inches on to the remade stretch. It was not very long ago that I struck such a ramp at speed and without any warning. Luckily, I was on a model which steered perfectly. Talking about roads, there is one little point well worth mentioning. Buses, like the majority of motor vehicles, are liable to deposit grease, so beware of bus stops, particularly in busy city centres. Incidentally, while in a big town during a rush hour, a good rider proceeds cautiously, for he remembers that pedestrians have a dangerous habit of stepping into the road with their backs towards the traffic. If pedestrians pause when about to cross a side street, it is a sure sign that something is going to emerge—another reason for immediate caution. Finally, remember that big motor buses and mammoth lorries, when turning down or emerging from a narrow side turning, have to swing out wide by reason of their length; it is true that the operation is usually heralded by ample warning. The foregoing remarks are but a mere indication of all the little points which a good and experienced rider is able to absorb instantly, realising their significance and using them to promote his own safety and those of other road-users. A knowledge of roadcraft is something of which to be proud; for myself, I am proud that I am still willing to learn and symphathise.”

“I AM SOMEWHAT ALARMED after reading ‘Veteran DO 357’s’ statement that he has spent less than £1 on necessary replacements after 300,000 miles—alarmed to think that I have been ‘done’. I actually spent £7 on replacements after 65,000 miles, patrolling for one of the road services. Possibly the figures given by your correspondent are erroneous, a decimal point having, been omitted. I sincerely hope ‘Veteran’ will not scrap his machine; I will gladly exchange my present magneto and one empty Castrol can (the cap will do for a medal) for his super spark-box. Joking apart, I should very much like to know how his original tyres are wearing.

Extravagant, London, SE12.”

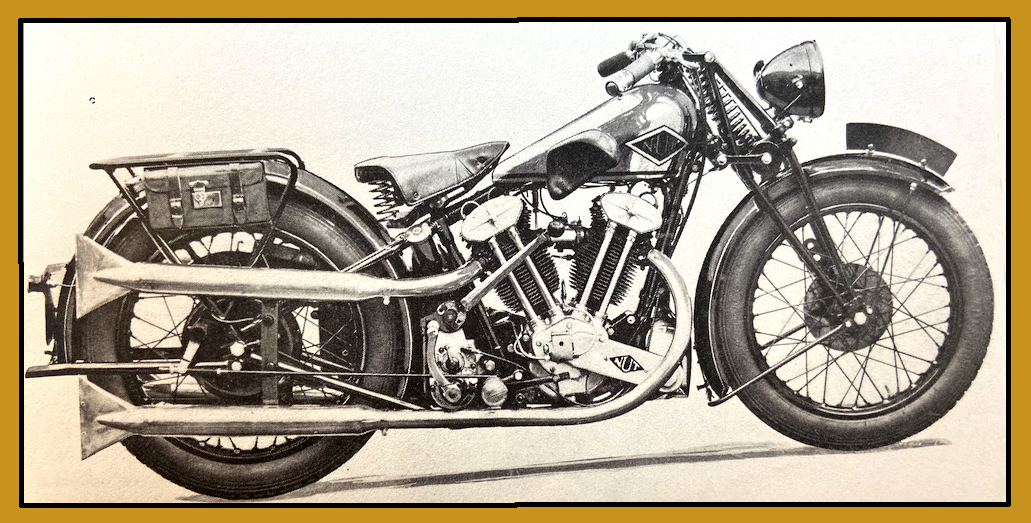

“FROM TIME TO TIME attention is drawn by motor cyclists to the bargains obtainable in the second-hand market. Most of the machines thus acquired, however, seem to be used for riding round a field (with the silencer removed) or some such travesty of motor cycling. My own experience in this direction may, therefore, be of interest, as I bought my old crock with the idea of working it hard—and I have. I told a dealer in South-West London that he would not get a better offer for that 1926 700cc NUT than the £3 that I had in my hand. He replied, No, he supposed he wouldn’t, so that was that. The price included six weeks’ tax, a horn, a pump and an electric head lamp. I rode it home (I was subsequently fined 5s. for excessive noise for this little trip) and spent £6 3s on the following: Two covers, one inner tube, rear chain, gear box, rear-drive sprocket, fork spindle, two hub cones, set of balls, two plugs; four valve springs, one valve, four piston rings and two Flexekas attachments. Of these, only the plugs and the valve were essentials. What was essential was to cut the induction pipe in such a way that it did not foul the inlet valve guides, since in the condition in which I found it it was, I imagine, impossible to make an air-tight joint. I now have a machine that has covered 750 miles in England and some 2,500 in this country (Nigeria). Not an enormous mileage, certainly, but the conditions have not been exactly ideal, and the cost, apart from petrol, oil, and tax, has been two-pence for a silencer bolt; moreover, there appears no reason why the expenditure should be any greater in the next 5,000 miles. I can guarantee a first-kick start every time, hot or cold, and at a steady 40mph burble a gallon of petrol of doubtful quality lasts at least 90 miles. And the long wheelbase, 4¼ to 1 top gear and vibrationless engine provide comfort not met with on many more pretentious bikes. The native of this part of the country is a keen trader, and the second-hand market is full, but I could sell to-morrow at a handsome profit over the original cost, plus cost of replacements. The eleven previous owners (if any of them should are this) might be interested in the subsequent history of 0N 7636.

‘OYIBO’, Abeekuta, Nigeria.” .

“I HAVE JUST READ ‘Steamboat Bill’s’ remarks about high mileage and petrol consumption; perhaps he would let us into the secret of how the figures he quotes were obtained. The best performance of my last machine—a 172cc two-stroke—was 70mpg, and this could not be improved upon without overheating. At that time the machine was under one year old, and I spent many hours of labour and changing of needles, but without avail. I now have a 1932 model 3½hp side-valve machine, and have just overhauled for my holidays. I have never had more than 66-70mpg, and during the overhaul the carburetter was checked against the makers’ instructions, but the performance could not be improved without impairing the efficiency of the engine. Apparently, ‘Steamboat Bill’ is the man I am looking for to tune my carburetter: perhaps it may be the Devon air. I shall be down that way shortly, so maybe I shall find the answer.

‘Petrol Complex’, Croydon.”

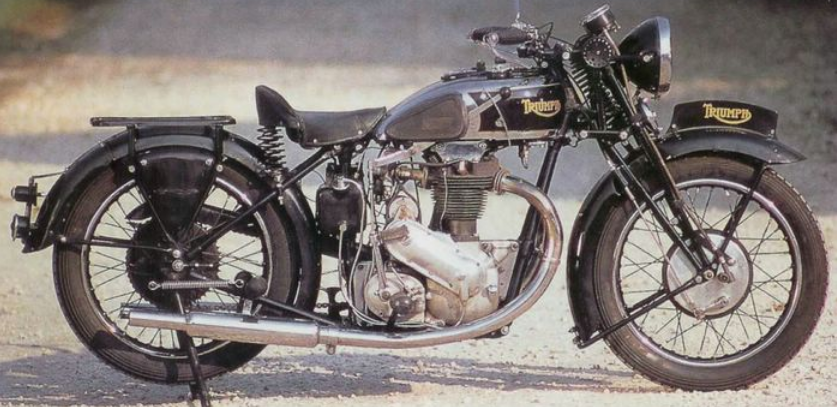

UNDER THE HEADING “New Machines to Suit All Purses” the Blue ‘Un compiled a comprehensive price list of something like 500 models. They ranged from an Excelsior 98cc two-speed two-stroke for £15 19s to a Brough Superior four-speed 988cc ohv twin with spring frame for £159 10s. Which, according to a CPI inflation calculator, translates as £1,500 for the Excelsior and £15,000 for the BruffSup. But a further trawl through the net revealed that a few years later, in 1938, a three-bed semi in Edgware sold for £835; a similar house now costs around £700,000. By this measure the Brough’s 2023 cost would be nearer £115,000—or, as the Brough sold for about a quarter the price of a semi, maybe £170,000. Which is about what you’d have to pay for a restored Brough today. George Brough’s bikes have been likened to Rolls Royces, and the saying goes that if you have to ask the price of a Roller you can’t afford it. Enough said.

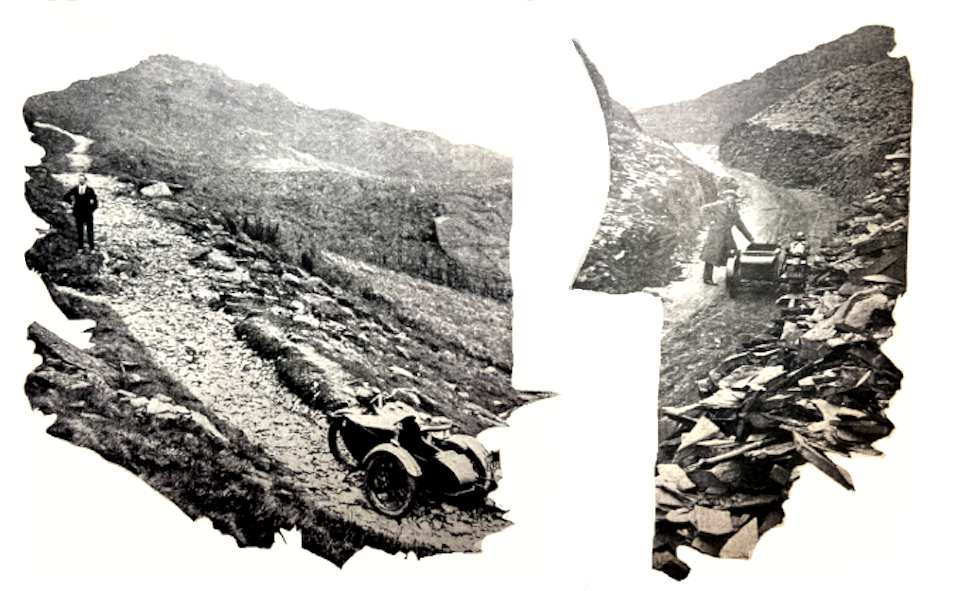

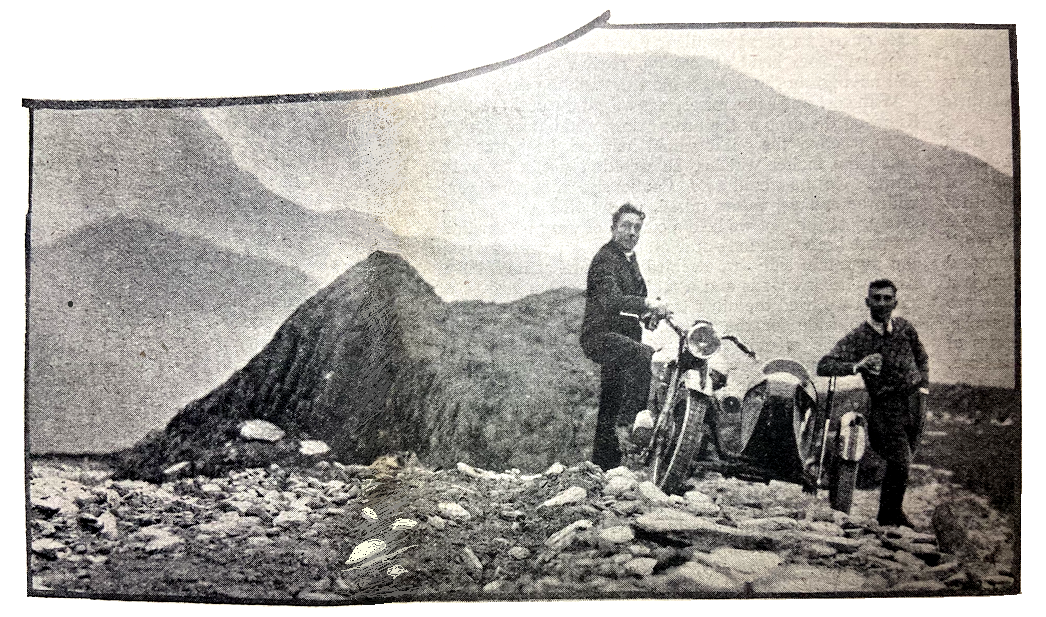

“THIS IS A TALE OF DEFEAT, some would say of folly. It is the true story of an attack upon the wrong hill, of a sheep that sent a baa-a-a echoing across the mountainside to coincide with our admission of defeat and of a side-valve sidecar outfit with the average-speed capabilities of a hyper-sports solo. The cause of everything was a manufacturer writing to the effect that he had digested all we said some time ago regarding oversize twins for the Canadian police, that he had gone ahead and produced such a machine and would we please try it out, putting it to a really strenuous test. And—oh, yes!—the maker would come, too, and sit in the sidecar. Now, gentle reader, remembering that the accent is upon the word ‘strenuous’, what would you do in like circumstances? Given the pleasant task, and having read about Walna Scar in the Lake District, I decided that an innocent inspection was indicated plus a little open-throttle motoring. So one recent Friday evening saw me making Nottingham, the home of the said maker, to wit George Brough, by way of the Great North Road. I arrived soon after ten to find Mr Manufacturer at home, the last of his men having just gone after much overtime turning out new models, and ready and waiting the new 1,150cc JAP-engined Brough Superior with a monster sidecar designed to accommodate 6ft 2in 16-stone (and more) policemen. Praise be! the sidecar was attached to the left, though perhaps you’ve never driven a right-hand outfit; believe me, for one used to the English arrangement it is ** *!!!†††. Footboards there were, also a hand clutch and a foot gear change. Later I learned that the four ratios were of TT closeness with a 4.2 to 1 top and 8.75 to 1 bottom. Shades of Walna Scar, and that bottom gear! Next morning, at the highly respectable hour of ten, we hit the highway. It rained; it teemed. For the first 80 miles it did nothing else, and the maker had come too—without even a windscreen. We were heading for Southport so that we might take a look at the Southport ‘100’ en route. Just north of Warrington we turned into the new East Lancashire By-pass; the mighty road that leads as straight as a tee-square into Liverpool. Never have I seen such a highway. It looks twice as wide as the Great West Road—so wide that I can foresee people getting hopelessly ‘at sea’ on it when there is a fog. On the way the Brough, with its huge side-valve engine and mighty sidecar, had already shown its paces—65; 68; 70; 72; 75…78. This last was with the aid of a slight downhill swoop. The honest maximum was around 75, and the great, wide outfit would cruise—yes, cruise—with the speedometer needle around the 68 mark. But would the engine stand up to wide-open throttle work for anything more than a short burst? On the by-pass we were faced by a strongish wind. The intention was that we turned off and went into St. Helens. We missed the turning—we were in Liverpool. The engine would stand up! At

the Liverpool end of the road a bus driver decided to thrust me out of the light. I refused to be done down, being, I considered, on the main road. Unfortunately, my path thereafter lay towards Robert; his away from Robert, who had turned round in time to see us having words. Politeness pays, I decided, and Robert, who did most of the talking, incidentally, went to great pains to explain the best way to Southport. So to Southport and on to the Lake District, with a cheery encounter en route with some Northern lads who objected to being passed by a sidecar outfit. On we went to Kendal to arrive beside Lake Windermere soon after sunset, just as the greys of night came down. At one bend, where the road overlooks the lake, I coasted and stopped to drink in the glories of nightfall beside the lake. Neither of us spoke, except to pass some remark about what lucky dogs we were, and why did not more motor cyclists, making full use of their buses. employ their week-ends similarly. Before finding an hotel at Ambleside we tried Kirkstone Pass from the Ambleside end. Second gear—6.75 to 1. Then a four-course meal in spite of the late hour, and BED. Next morning a dutiful journalist was to be seen in his bedroom, up before breakfast, writing his report of the Southport ‘100’. At ten we were off again; this time for Coniston and Walna Scar. The road to the Scar from Coniston is a pukka trials hill in itself . Right at the start there are twists and turns and hummocks and gullies and rocks. There was also mud. However, with a short series of rushes, the Brough got safely up. If it’s like this here, what on earth is it like when we get to the hill proper? For a bit it flattened out, and after going through two gates we decided to look at the map. It was not too clear, and the pukka road seemed to go to the right, so we went to the right. At first it was roughish, but reasonable. We rounded a bend to find, partially hidden by mist, one of the finest panoramas I’ve ever seen in Lakeland. The hill became steeper; we rounded a rough right-hand bend, literally fighting our way. Steeper, still steeper; the Brough, with its 8.75:1 bottom gear, was on full throttle. Upward we wound, to come to a scene of wild desolation—rock shale everywhere. A sharp turn left, with a horrid rock-strewn roll, bowl or pitch on the right. With the rough surface, our inability to get up speed and so keep up the revs, I was already resorting to slipping the clutch. Round the bend was a stretch of shale-covered roadway rearing skyward with a gradient of 1-in-3. The five-plate clutch became odoriferous—we stopped. One huge rock was placed behind the back wheel, with another behind it to act as a strut. A photograph; then we walked upwards for some two or three hundred yards, finding en route a slate quarry, in 2⅓ gradient (measured), and a rock-strewn hairpin bend almost too narrow for the outfit and having, on the right, a most devastating drop. With care and some misgivings we

got the outfit round. Knowing the drop at the bend below, and having doubts as to whether the outfit would hold on the surface, I asked the maker whether he wouldn’t prefer to walk down. No. he would not! Cautiously, in bottom gear, with the exhaust valves raised, we set off downwards—safely. At the foot we held a council of war; we decided we were beaten—a long, drawn out ba-a-a-a floated down the mountain side—we decided to return again with a narrow-track chassis and a really low bottom gear. Then we tried the other track. The 52in track outfit was too wide for the rutted, narrow road, and after bending the off-side footboard and the sidecar mudguard, and much heaving, we returned. Ba-a-a-a again! Then some motor cyclists arrived, and later some hikers. The former were out to see the Scar, haying read the correspondence in The Motor Cycle. The latter pointed out which was the. Sear—it was the narrow track that was too narrow—and told us that the road we had been on was out of the question. Defeated, we went back to Coniston, made rapid strides with eggs and locally cured ham, and, full of plans, set off for Nottingham, and in my case London, to call it a day. The Second Expedition. A date was fixed some 10 days later. Again an evening run to Nottingham. Again an outfit was ready. This time it was an 1,150 with a narrow-track (39in) banking sidecar—Freddy Dixon’s famous TT design—and a 15.2:1 bottom gear. At 6am next morning we were up. It was fine. Soon after 6am we were off, with FW Stevenson trailing us on an 1,150 solo. The maker was not to operate the banking lever until I got the feel of the outfit. Then I gave the signal. We were going into a left-hand bend. Our actions did not coincide. As he let the lever forward the whole machine leaned in on the sidecar; round we went at 50 or 60—I feeling not too happy about the leaning business. Soon we were working in unison. It was uncanny; bends normally taken at 40 could be negotiated at 60 and more. Once, on a tight-hand bend, I entered the turn hurriedly, and signalled. Nothing happened…I used the camber, the bend was an open one, and all was well. Later I found that with the one joystick fitted (Dixon used two in the Isle of Man) it was real hard work pulling the sidecar up for a right-hand bend, so generally we only banked for left-hand ones. Given a passenger you can count on, such as I had, and assuming you are on a route which you both know by heart, this banking sidecar is a masterpiece. Even in my untutored hands it put miles an hour on our average speed, but beware of turning the outfit to the left in the belief that your passenger will bank the outfit for you when the correct route lies to the right and your passenger, not unnaturally, is expecting you to go right. Such an occurrence happened near Weatherby, and I nearly had the maker round my neck. One other contretemps occurred on the way to the Lakes. The first 40-something miles out of Nottingham were covered in 40-something minutes. Life was good, and the roads wide and clear. Then I had a suspicion that the outfit was slowing. I looked down: instead of 68 to 70 the speedometer showed 65. I tweaked the throttle to see if the engine really was ‘catching’. There was a hiss and a shushing, plopping noise, and

we coasted to a standstill. An experimental high-compression light alloy cylinder head had a hole in it, burnt through around the plug, so new standard heads were procured hurriedly by ‘phone and sidecar outfit from the works. These fitted, all was well, and we made the Lake District, devoured more ham and eggs, and set off for Old Man Coniston again. This time the rough lower section, owing to the narrowness, high centre of gravity, and lightness of the sidecar, was not so easy, and once, after a more than usually vicious gully, I kecked the sidecar up and had to foot it down with the aid of a convenient portion of bank. Then over the level section, and off to the right for the road into the mountains. Instead of being dry and hard the lower section was slimy and muddy. Upward we wound—now with the rear wheel spinning, now with the outfit kangarooing, its front wheel lifting owing to the combination of the rocks, steep gradient, and rearwardly set sidecar body, so arranged to assist wheel grip. We passed the 1 in 3 section, where we stopped the previous time; up the part which we measured as being 1 in 2⅓; then the rocky, narrow hairpin with the drop on the right…Yes, the front wheel came up, we slewed, we stopped. Three or four attempts, and we were safely past this danger spot. Then the track divided into two; we went right, and soon found ourselves marooned amid rocks. It was useless; we tried the other track. That, too, was hopeless. The surface was smoother, but we could not get sufficient wheelgrip on the steep gradient, so we prospected on foot. Stevenson, by herculean efforts, had got his big solo within two or three hundred yards of where we stuck, and leaving his bus where it halted, perched on its crank case, helped us in our restarts and stood by to pick up the pieces if, in our leaping and crabbing, we went over the edge. Determined to get up somehow, he raced ahead on his two feet to where the track ended at a final slate quarry, and then disappeared skyward over the rocks—on hands and knees! It was no use ; we doubted whether any wheeled vehicle could climb those last slopes with their vicious gradient and deep, loose shale. No wonder we saw no tracks—not even of the sledges they use lower down. We returned and made for Walna Scar, the correct hill. The track became rough—so much so that we were soon ploughing through masses of rocks like the dried-up river bed on the Mamore Section in the Scottish. We lurched, we crashed up and down, we scrunched. At one point more vile than the rest the sidecar came up and we landed on the bank with the outfit on top of me. ‘Shall we turn back—if we can?’ I asked the maker. ‘No, we’ll get through somehow,’ he replied. ‘Righto!’ I answered, ‘I was only asking you, for it’s your outfit, and it may be smashed up.’ We struggled onward to land at another quarry. Then over a series of extraordinary rock-covered humps of about eight-foot span and shaped like a semi-circle. By short rushes we scraped over all except the last two, where, mercifully, we stuck, grounded with the wheels in the air. Not 10 feet ahead, on the edge of the track, was a sheer drop of 50 or more feet into a great hole with green, sinister-looking rocks at the foot. We looked at each other; had we got those few feet farther with the steep gradient and the inevitable crabbing there would be an unhealthy chance of there being only battered remains. We prospected; this could not be Walna Scar, for nothing could get up here, whereas some cars, we’d heard, had been over the Scar. On our return we met a bronzed hiker in an officer’s tunic. He laughed; we had tried to tackle Doe Crag, a haunt of climbers, where two had been killed earlier in the year. Wrong again! We should have turned left along a grass track. To say that a hill you fail upon is easy is, I suppose, hardly done. The trouble was wheelspin resulting from the wet weather, for the shale-covered, hairpinned gradient of the Scar was innocuous compared with the wild tracks the Brough had negotiated. We returned—defeated, and dog tired. To our surprise, it was 9.30pm, the time at which we were due back at Nottingham. So we filled up—men and machines—and set off on the 200-mile run. This time I was on the solo. I was too tired properly to appreciate the solo, but this I did learn: that it is the most effortless, thrilling, gliding batting-iron I have ever been on. So to Nottingham, safely reached at 3.30am, where three red-eyed men crept off to bed, defeated, perhaps, and Old Man Coniston still laughing, and the sheep still baa-a-a-ing, but three men who had had one of the most enjoyable trips of their lives.”

“DURING THE LAST YEAR or two a big improvement has been noticeable in the important feature of accessibility and ease of adjustment. Many machines of the 1926-1930 era were very bad in this respect, but since that time great strides have been made. We would, however, urge manufacturers to continue the good work, while there is time, in the production of their 1934 models. There is still room for improvement, particularly in lower-priced machines, on which one bolt or similar fitting is often made to serve a variety of purposes; there are still too many mounts on which half a dozen parts have to be dismantled or removed before one part can be reached. Particularly is this true of primary chain cases. Bearing in mind that nowadays almost all motor cyclists do their own maintenance work, designers might do worse than to hand over to a non-expert a new model equipped with only the standard tool-kit, and make a study of the time and trouble he expends in dis-mantling and assembling various parts.”

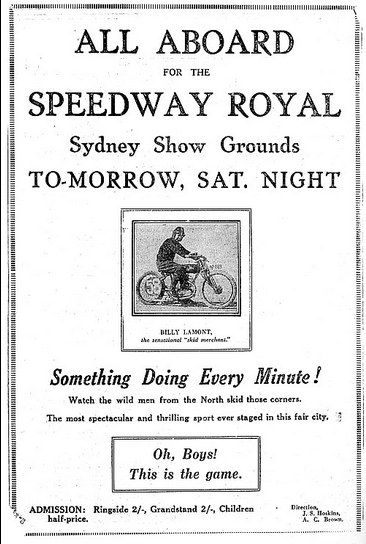

THE AUSSIES (WHO ELSE?) revived chariot racing at the Police and Firemen’s Carnival. The Sydney Morning Herald reported: “A more spectacular attraction has never been seen on Sydney Showground…A shining duet of V-twin Harley-Davidsons bolted abreast, each towing an elaborately decorated chariot with full-size H-D wheels, these contraptions exceeded anything conceived by filmmaker Cecil B.”

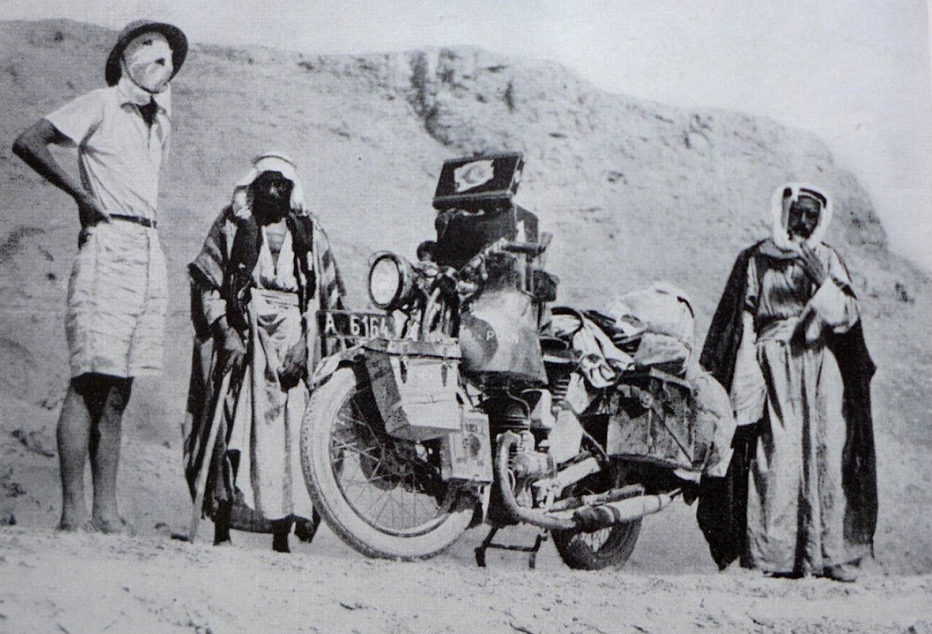

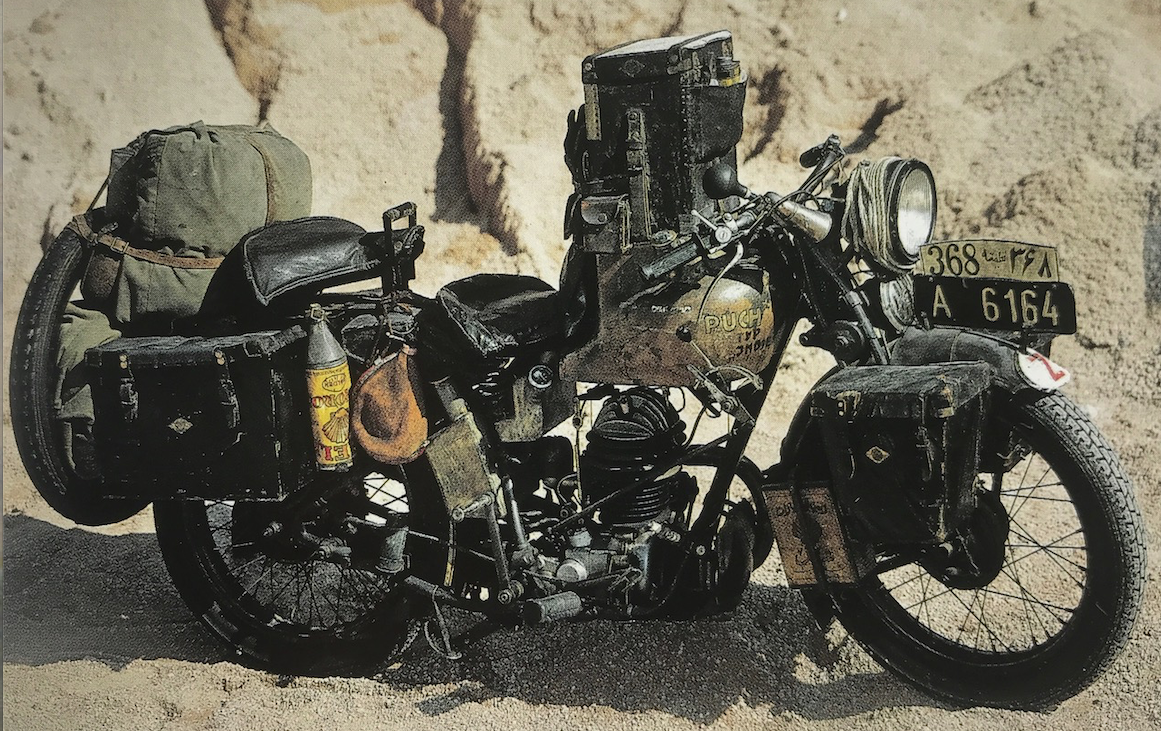

MAX REISCH, A 20-YEAR-OLD student from Vienna, and his pal Herbert Tichy clearly felt in need of adventure: they planned to make the first overland journey on a motor cycle to India. Max was no novice—when he was just 16 he made a ‘test run’ through Italy, France and Spain, by sea to Morocco, Algeria and Libya, returning via Sicily and Italy. With this record Reish persuaded Puch to sponsor the expedition with a 250cc two-stroke model 250T. Their 8,000-mile, six-month odyssey took them across the Balkans, Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran and Pakistan to Bombay. They detoured round Afghanistan which was too dangerous for Europeans. A crash on the first day and bent the bike’s forks and set a pattern for the rest of the run; they came off several times most days. Puch used the run to demonstrate the 250’s durability: the engine and gearbox were sealed and those seals remained undisturbed. The only attention the bike needed was a periodic decoke, although it did break an alarming number of spokes. The pair had to deal with fever, heat exhaustion, bush fires, customs problems and unwelcome attention from men with guns, although they brought back tales of extraordinary hospitality too. As if they needed reminding that this was a dangerous journey, at one point they passed the grave of a European motor cyclist. Luggage included a hefty glass-plate camera and typewriter, Reisch wrote a book, India, The Shimmering Dream, which is still readily available. In it he wrote: “There were many things on our journey which we could take in only superficially, but we did so with wholehearted enthusiasm. I do not envy Americans who slave away their entire lives to go around the world in their old age. For them, such a journey is the fulfilment of a life but for us it was an education.’ Talking of the hardships they faced he added: “This was how we lived in the desert, because we were young and did not need the approval of civilisation and because our eyes were set on our final goal, the wonderland of India.Nothing is achieved by fussing over trivialities.’