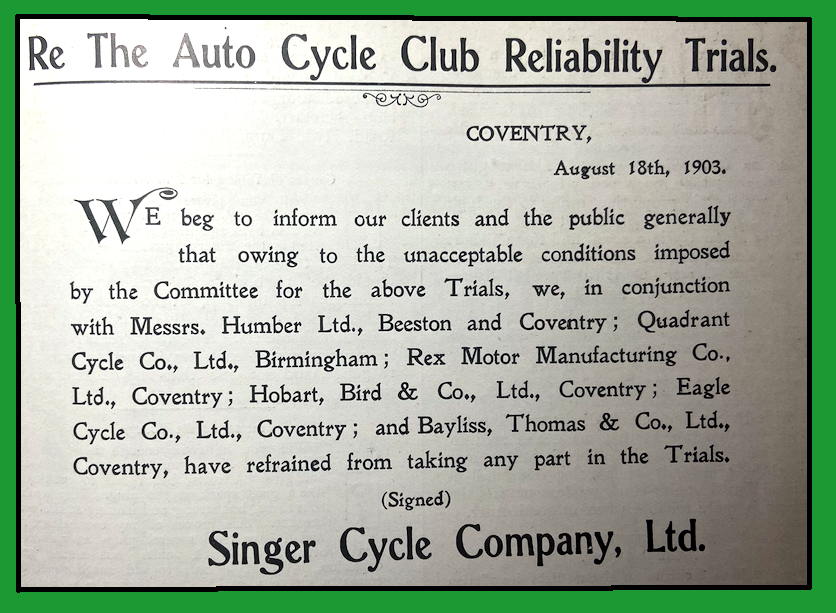

“ACC 1000 MILE TRIAL. Forty-eight entries have been received for these important trials, which commence next Tuesday. Of these, 13 are from private owners, and we set out now the full details of each entry. We are pleased to note that several new makes of motor-bicycles are in competition with other well known manufactures. The start and finish is at the Crystal Palace, different routes being taken each day, the trials concluding on August 22nd with speed tests on the track. Whilst on the road the machines have to cover sections of 10 miles within specified limits, the scoring being by a system of marks. We notice, with great regret, that the signatories to the recent protest against the scheme have refrained from entering machines for the trials. We are afraid that the action of this section of the trade is not a wise one, making neither for individual nor collective good.”

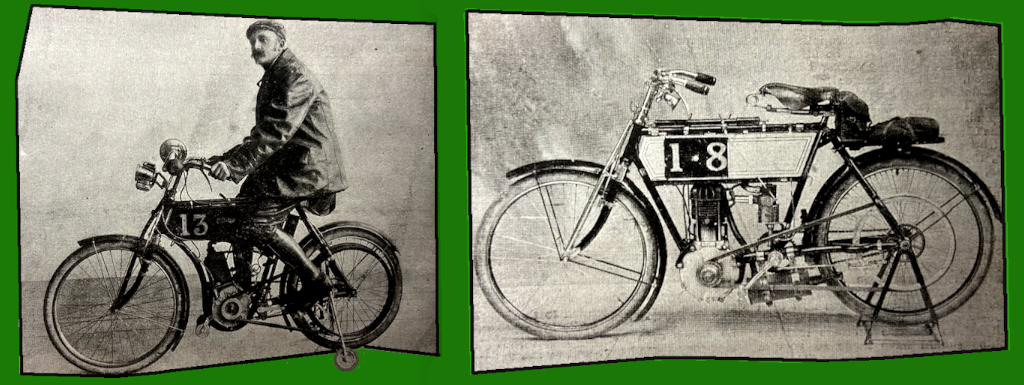

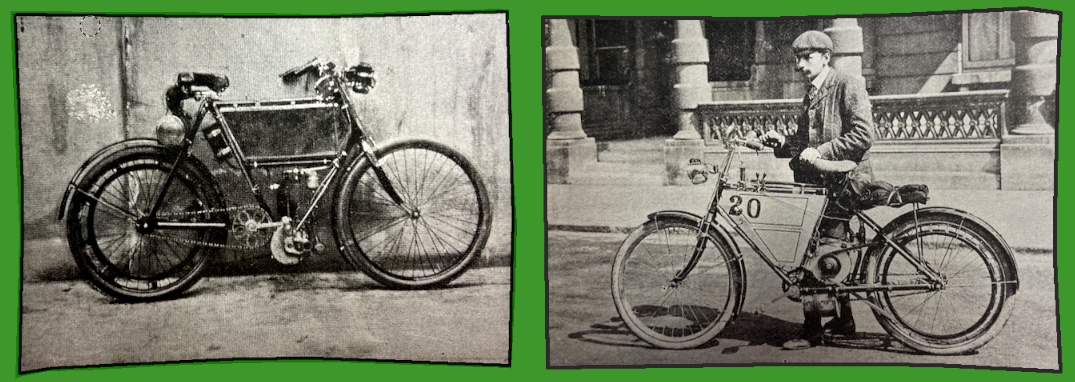

“CLASS FOR MANUFACTURERS and Agents: 1, Bradbury (entered by Bradbury & Co); 292cc Bradbury engine; claimed power, 2hp@1,500rpm; kerbweight, 125lb; claimed top speed, 25mph; retail price, £45. 2, Bradbury (Bradbury & Co), 363cc Bradbury, 2½hp@1,500rpm, 140lb, 30mph, £50. 3, Peugeot (Friswell Ltd), 232cc Peugeot, 2hp@n/a, 114lb, n/a, £42. 4, JAP (Prestwich & Co), 288cc JAP, 2½hp@1,200rpm, 110lb, 20mph, £45. 5, Noble (Noble Motor Co), 292cc Noble, 2½hp@1,100rpm, 110lb, 17mph, £32. 6, Booth ( Booth Motor Co), 254cc Booth, 2hp@2,000rpm, 120lb, 17mph, £45. 7, Booth ( Booth Motor Co), 433cc Booth, 3½hp@1,800rpm, 125lb, 45mph, n/a. 8, Roc (AW Wall), n/a Roc, 2¼hp@1,500rpm, 90lb, n/a, £45. 9, Roc (AW Wall), 482cc Kelecom, 3¼hp@1,500rpm, 150lb, 30mph, £55. 10, Griffon (FR Goodwin), 2½hp, n/a. 11, Bat (Bat Motor Co), 382cc MMC, 2¾hp@382cc, 1,200rpm,150lb, 40mph, £50. 12, Bat spring frame (Bat Motor Co), 382cc MMC, 2¾hp@1,200rpm, 150lb, 40mph, £55. 13, Kerry (East London Rubber Co), 308cc Kerry, 2¼hp@1,400rpm, n/a, 30mph, £44. 14, Phoenix (Phoenix Motor Co), 331cc Minerva, 2½hp@1,500rpm, n/a, 20mph, £50. 15, Phoenix Trimo (Phoenix Motor Co), 433cc Minerva, 3½hp@1,500rpm, n/a, 20mph, £73.10s. 16, Ariel (Ariel Cycle Co), 372cc Ariel, 3hp@1,700rpm, 150lb, 40mph, £52.10. 17, Brown (Brown Bros), 331cc Brown, 2¾hp@1,600rpm, 145lb, 25mph, £42. 18, King (W King & Co), 412cc King, 2¾hp@600rpm, 170lb, 12mph, £50. 19, Robinson and Price (Robinson and Price ), 269cc R&P, 2¼hp@1,200rpm, 108lb, 20mph, £45. 20, Ormonde (Ormonde Motor Co), 376cc Kelecom, 2¾hp@1,500rpm, 130lb, 35mph, £50. 21, Weller (Weller Bros), 292cc Weller, 2¼hp@1,500rpm, 120lb, 25mph, £45. 22, Werner (Werner, Ltd), 345cc Werner, 2¾hp@1,800rpm, 118lb, 32mph, £45. 23, Werner forecarriage (Werner, Ltd), 454cc Werner, 3¼hp@1,650rpm, 124lb, 35mph, £75. 24, Werner (Werner, Ltd), 279cc Werner, 2hp@2,000rpm, 105lb, 26mph, £40. 25, Lagonda (Lagonda Co), 363cc Lagonda, 2¾hp@1,800rpm, 130lb, 31mph, £55. 26, Castell (Castell & Sons), 402cc Fernhead, 2¾hp@1,200rpm, 127lb, 16mph, £45. 27, Jehu (Jehu Motor Co), 239cc Jehu, 2hp@1,800rpm, 120lb, 25mph, £45. 28, Chase (Chase Motors), 239cc Ariel, 2¼hp@1,800rpm, 120lb, 22mph, £47 5s. 29, Chase (Chase Motors), 382cc Ariel, 3hp@1,800rpm, 130lb, 24mph, £52 10s. 30, Rex (HW Stone), 331cc Rex, 3hp@2,400rpm, 170lb, 35mph, £52 10s. 31, Matchless (HA Collier), 327cc MMC, 2¾hp@800rpm, 160lb, 16mph, £45. 32, Regina (Ilford Motorcycle Co), 416cc MMC, 2¾hp@1,500rpm, 140lb, 20mph, £50. 33, Evart Hall (Evart Hall, Ltd), 399cc n/a, 2½hp@1,200rpm, 140lb, 30mph, £45. 34, Alldays (Alldays and Onions), 292cc n/a, 2¼hp@1,600rpm, 110lb, 25mph, £45. 35, FN (McTaggart), 232cc FN, 2hp@700rpm, 115lb, n/a, £43. Private Owners’ Class: 36, Phoenix tricycle (A Hooydonk), 433cc Booth, 3½hp@1,500rpm, n/a, 20mph, £70. 37, Ormonde (C Vandeville), 386cc Kelecom, 2¾hp@1,500rpm, 130lb, 20mph, £50. 38, Ormonde ( D Elgard Brown), 285cc Kelecom, 2¼hp@1,500rpm, 130lb, 30mph, £45. 39, Quadrant (A Candler), 239cc n/a, 2hp@1,500rpm, 100lb, 35mph, £50. 40, Werner (A. Hoffman); 345cc Werner, 2¾hp@1,800rpm, 120lb, 32mph, £45. 41, Roc (A Haufton); n/a Roc, 2¾hp@1,500rpm, 170lb, n/a, n/a. 42, Ormonde (n/a), 376cc Kelecom, 2¾hp@1,500rpm, 130lb, 35mph, £50. 43, Rex (n/a), 345cc Rex, 3hp@1,600rpm, n/a, n/a, £52. 44, Booth (SB Moore); n/a Fernhead, n/a@2,000rpm, n/a, n/a. 45 Spark (A Hirst), 274cc Spark, 2hp@1,800rpm, n/a, 25mph, £38. 46, Spark (n/a), 274cc Spark, 2hp@1,800rpm, n/a, 25mph, £38. 47, Rex, (CF Law), 373cc Rex, 3hp@n/a, 170lb, n/a, £52 10s. 48 N/a (J Bond), 168cc n/a, 2¼hp@1,700rpm, 120lb, 30mph, £47.5s.”

“THE 2HP WERNER ENTERED for the trials should have been described in our table as 68 bore x 72 stroke, instead of 68×77. The list of entries was drawn up very hurriedly, and contained some errors for which we are not responsible.”

“THE MOTOR-CYCLE RELIABILITY TRIALS: August 11, ride to Canterbury and back; August 12, ride to Brighton and back; August 13, ride to Worthing and back; August 14, ride to Eastbourne and back; August 17, ride to Folkestone and back; August 18, ride to Brighton and back; August 19, ride to Basingstoke and back; August 20, ride to Eastbourne and back; August 21, ride to Worthing and back; August 22, Speed Trials on Crystal Palace Track.”

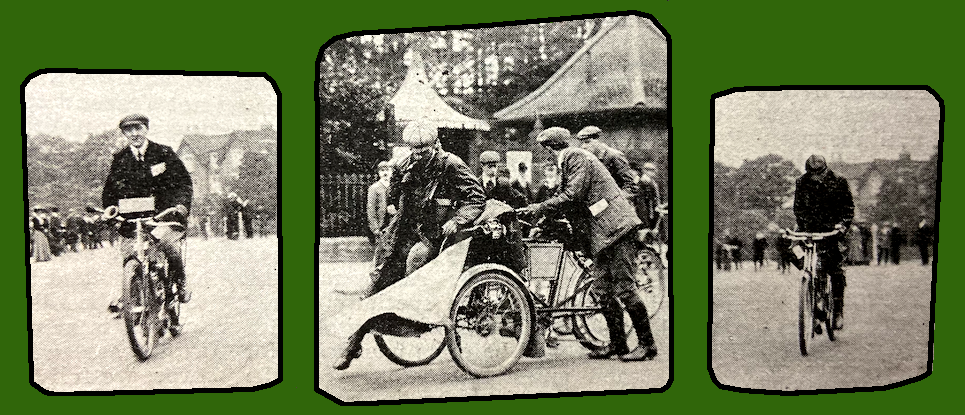

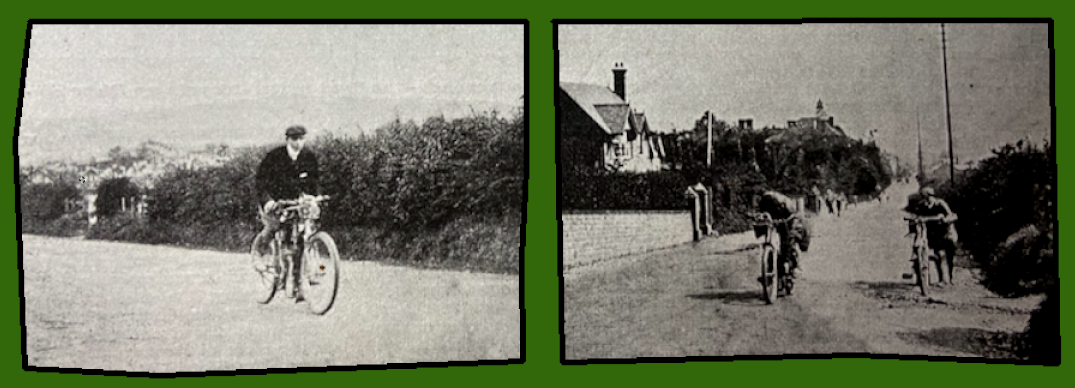

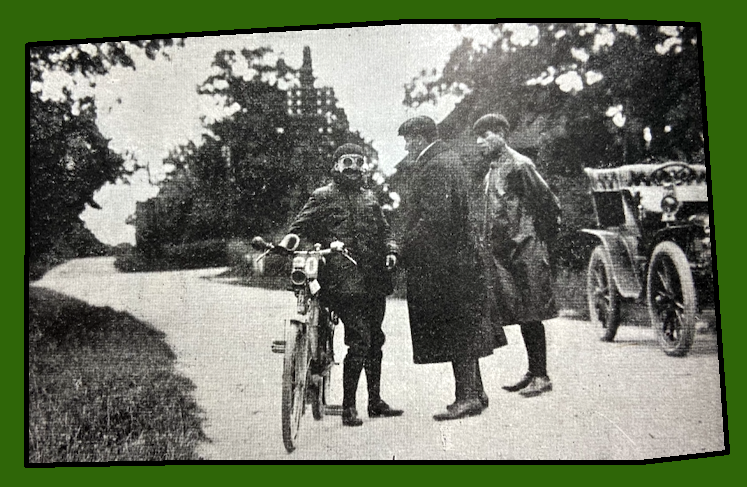

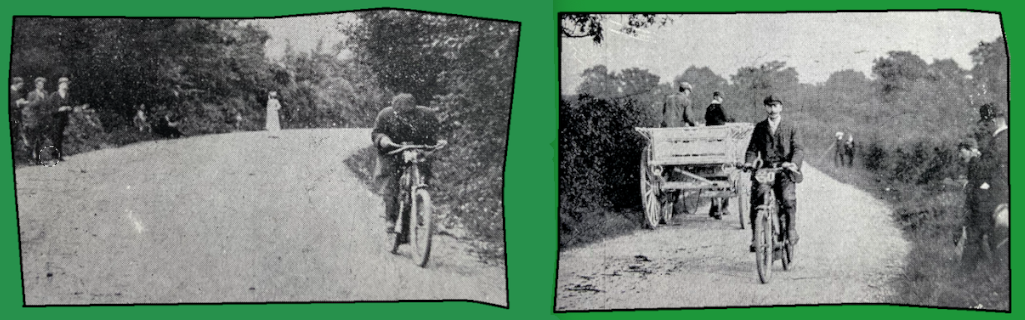

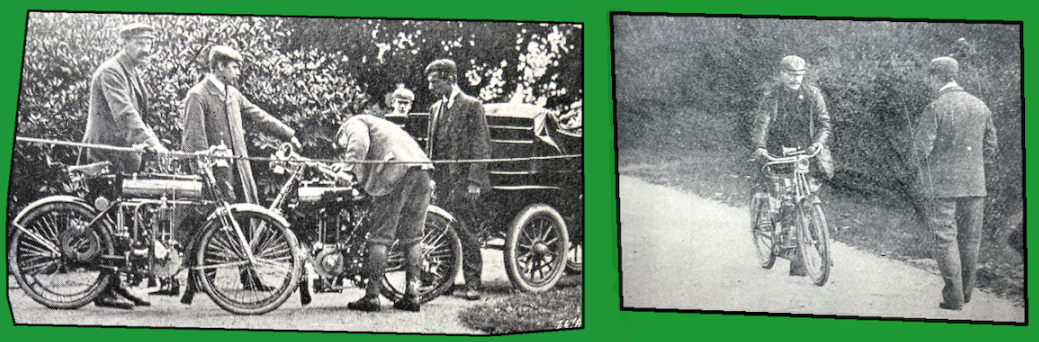

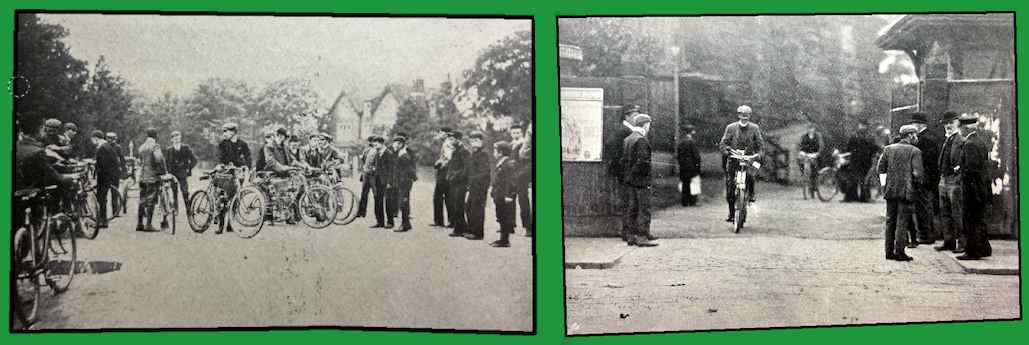

“ON TUESDAY MORNING [11 August] the roads were wet and holding in places, and the sky was very threatening. Soon after eight in the morning the competitors were admitted to the tent, and the final preparations were made, and then the machines were pushed up to the exit on the Parade, most of the men showing fatigue as the result. The route was through Bromley, Wrotham, Maidstone, and Sittingbourne, to Canterbury, returning the same way. By a curious coinciderice rain commenced to fall just as Rainham was reached. A little further along a cow took offence and charged the Regina motorcycle, doing so much damage that a conveyance had to be requisitioned. Buquet, the famous Werner speed merchant, had entered, thinking that it was a 1,000 miles race, and that as long as he got through first he need not worry. So he used a high-powered, big-geared Werner, and then found that he was embarked on a game totally foreign to him. A side-slip was his only trouble on Tuesday. FW Chase was amongst those who gathered punctures. Theo Hooydonk, on the Ariel, was standing and shaking the raindrops from his person, when his machine slipped out of his hand, resulting in a broken left handlebar. He very pluckily rode the rest of the day over vile roads with a single bar, and replaced the member next morning. His ride was rendered more notable because the broken part of the bar contained his switch, and moreover his emergency brake was gone. Two

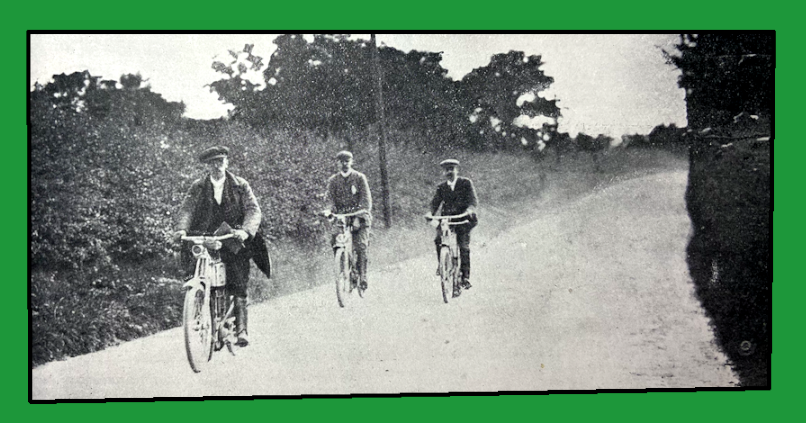

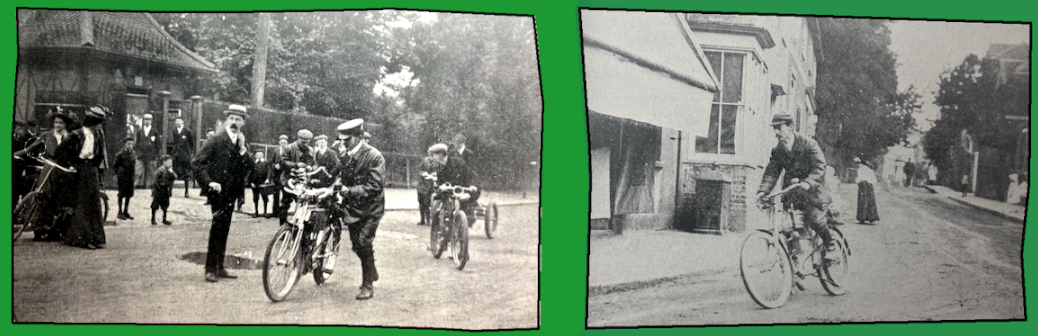

machines dropped out of the ranks before they had gone two miles but out of the remaining 42, 36 regained the Palace amidst the most gloomy surroundings. A clean down improved matters, and dry clothes and some food took the riders many stages away from their previous unhappiness. Wednesday fortunately broke fine and genial, and 35 riders turned out to essay the journey. J van Hooydonk, on his Trimo, with a double load of passenger and luggage, had come to the conclusion that the game was not good enough. He had felt more fatigued as the result of his day’s hill climbing than he had ever felt before, and, although his machine had gone splendidly all day, with never a misfire, even in the pouring rain, he had resolved to leave the contest, so far as the Phoenix was concerned, to the safety and tricycle which also represented his interests. So on Wednesday he was a spectator, and a very interested one, particularly on Westerham Hill. The route for the day was via Keston, Westerham, Hartfield, Uckfield, and Lewes to Brighton, returning the same way. All got away well except one, the Jehu, which had tyre troubles, as the result of the previous day. It made a late start, however. Westerham was sufficiently formidable for many to walk down, and after that the road was exceedingly hilly to Uckfield. The machines travelled wonderfully well, showing never a sign of the fearful punishment administered the day before. Westerham Hill was found to be in good condition, and soon after four o’clock FW Chase came up the hill on one of the new 3hp Chase machines. He pedalled up the steep

portion, but dismounted just over the brow, pumped out. The 2¾hp Matchless did nearly as well, and then came the FN, pushed by its rider up the worst part. Wright, on the 2¾hp Ormonde, now came up splendidly, and he was immediately followed by Mills on the 2½hp Phoenix. A few light strokes of the pedals constituted the whole of the assistance given by these riders, who certainly made the best showing on the hill. The other machines which surmounted the hill with continuous pedal assistance were the 2½hp Griffon, the 2½hp Bradbury, the 2¼hp Alldays, the 2¼hp Kerry, and the 3hp Ariel, and, amongst the private owners, the 2¾hp Ormonde of Mr Vandervell, the 2¼hp Ormonde of Mr DE Brown, and the 3hp Rex of Mr FW Applebee. [Note the name—FA and FW Applebee will figure prominently in this timeline—Ed.] Some dismounted either on the steep portion or farther up near the summit, and then, remounting, after a rest for breath recovery, finished the task. These included the Chase and the Matchless previously mentioned, the 2hp Werner, the 2¾hp Brown, and, in the private owners’ class, the 2¾hp Werner of Mr Hoffma. The other 18 machines had to be pushed over the steep portion at least, whilst one or two might be classed as complete failures on the hill. But, on the whole, the performance was satisfactory indeed for road machines geared on a compromise between Westerham and a speed trial on the track (admittedly an absurd idea which must never be repeated). Thursday was another fine day, the route being via Epsom and Horsham to Worthing and back. The police had prepared a trap, with telephonic communication from one end of it to the other, and as a result most of the riders were stopped and compelled to communicate names and addresses. It was a most glaring instance. of the prejudice of the local authorities, and a proof that the police intended to hatch. up cases if possible. The rules

provided against any excess of speed, and as controls were established but 10 miles apart it was absurd to imagine that any competitor should travel at 30, or even 20mph for nine miles, and then crawl at 2mph until the control was reached. But the police have their instructions, and so a motorist must be captured and fined irrespective of circumstances. The route on Friday was to Eastbourne and back via Sevenoaks and Tunbridge Wells, another excessively hilly route. Unfortunately rain commenced to fall just before the starting hour, so that the riders had before them the prospect of another comfortless day. Rain fell at intervals for the great part of the day, and, to make matters worse, it was a bitingly cold rain. A good start was effected, although Tessier and Wright got into collision in the Palace grounds through the former’s action in returning down the narrow steep lane to the tent. Some small replacements to Tessier’s machine were necessary, and both he and Wright went through satisfactorily. Some short circuiting troubles occurred amongst the competitors, and punctures occasionally thrust their unwelcome attention upon the wet riders. But perhaps the most universal trouble was the clogged-up clutch to the rear wheel, the mud and dirt getting in, fixing the pawls and giving a free-wheel both ways, thus rendering the pedals useless. The hills were taken philosophically: they might be bad and greasy, thought the riders, but on the other hand, they might have been worse! The rain eased off during the middle of the day, and the sun actually peeped out at times. But later on the heavens opened again, and those who had secured a change of clothing (dry socks or stockings having been the favourite purchase) were in as parlous a state as ever in a very brief time. As instancing the spirit of the riders, a little group in the evening was discussing the subject of suitable motor clothing for rainy seasons, many new ideas being brought out, such as the assertion that the ends of the knickers should be made to lap over the gaiters, instead of being placed inside, as they invariably are, for water runs down the knickers, enters the inside of the gaiters, swamps the stockings, and fills up the boots so that they ‘squelch’ when walking! The difficulty of keeping the water from going down the neck, the porosity of leather under a heavy soaking, and other kindred subjects, showed how contented the riders were to regard their experiences from the educational point of view. Police attentions were practically absent from the ride, although they had been expected. August Hooydonk, on the single-seated Trimo, was the recipient of the attentions of some blustering busybody—a noted anti-motorist—near Eastbourne. The Palace was reached by the first rider at about six o’clock, and, for four hours the men were coming in, very wet and dirty, but glad that the first week’s work was over. Machines were cleaned up and covered over until Monday. The machines which seem to be doing well are the Chase, the Bradbury, the Griffon, the Bat, the Phoenix, the Brown, the King, the Robinson & Price, the Ormonde, the Werner, the Matchless, the Alldays, the Ariel and the Rex. Bucquet cracked the boss on his cylinder on Wednesday, and retired ; the Weller had a petrol blaze one morning before the start; the Lagonda spoilt a good record through getting pieces of a sparking-plug in the cylinder, but has gone well since. However, no comparison can possibly be drawn until the figures are published at the end of the week, so that the above list of those apparently doing well is merely the outcome of superficial observation, and must be open to considerable modification. Tessier, who had been riding a Bat through the trials, came to grief on Canning Town track—one of the disadvantages of interlude’—and the makers were unable to put up another man, which was a pity,

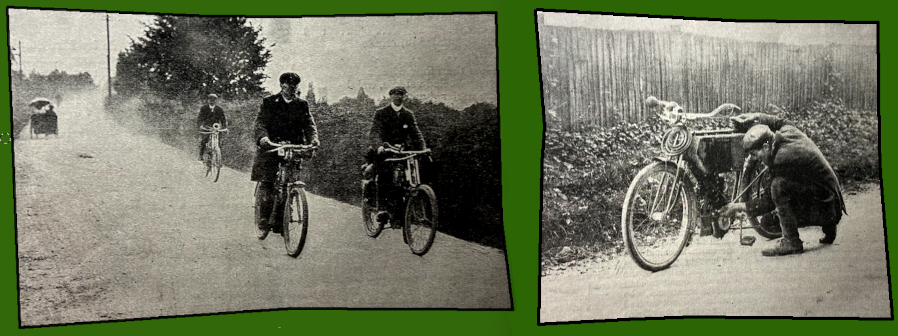

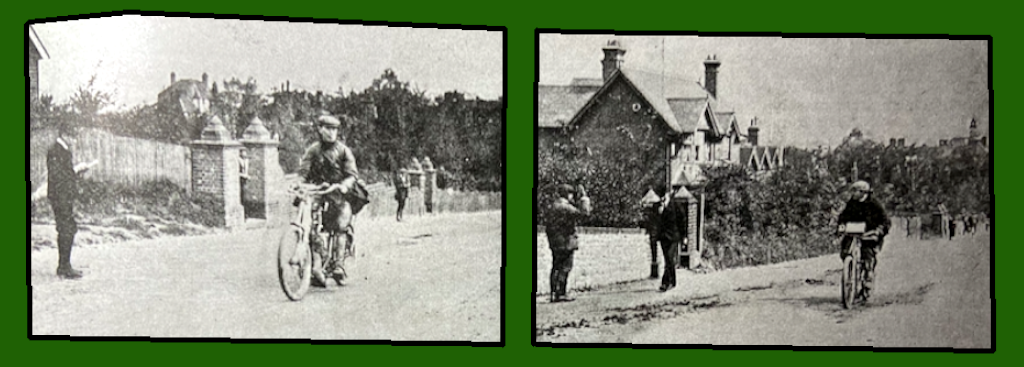

for the machine had travelled well. So, on the Monday morning, 32 machines set out for the second week of the trials, and throughout the week rain has fallen at intervals, sometimes exceedingly heavily, and generally at such times as to leave the suburban roads in a very greasy state, making them more difficult to negotiate than if they had been really flooded. The Monday run was to Folkestone via Wrotham, Maidstone, Ashford and Hythe and, as the total distance for this day was no less than 134 miles, an early start was made, the word to go being given at eight o’clock. The run passed off with little or no incident, but one of the riders reported that at one part of the route he came across a line of bricks laid across the road. All who started finished in good time. This run was the longest in the whole trial, next to it in length being the two Eastbourne runs, which worked out at 125 miles. On the Tuesday the Brighton road via Redhill and Handcross was traversed for the first time, and the 32 riders reached the Old Ship Hotel in close order, and as this was a short journey—95 miles—the Palace was re-gained by the leaders just after four o’clock. The rider of the 2hp Booth, which has a dropped or lady’s pattern frame, was upset by a dog, and he decided to return by train, thus forfeiting the whole of a day’s marks. The Evart-Hall also sustained a slight mishap, but both machines and riders were again in good order for the run on Wednesday to Basingstoke. There was every promise of a fine day when the whole 32 turned out to a man. But, of course, the customary showers fell—and fell heavily, too—before Guildford was reached, the road via Croydon, Epsom and Leatherhead being taken. However, rain was being so looked upon as the usual thing that scarcely any notice was taken of it, and the only delay was that which ensued through the officials’ vehicle, which was to lead the way to Guildford, but which jibbed on the way. Expert hands soon put matters to right, however, and the journey was resumed. At Guildford the riders stopped at the Town Hall, and were dispatched singly down the High Street and round over the railway bridge to the

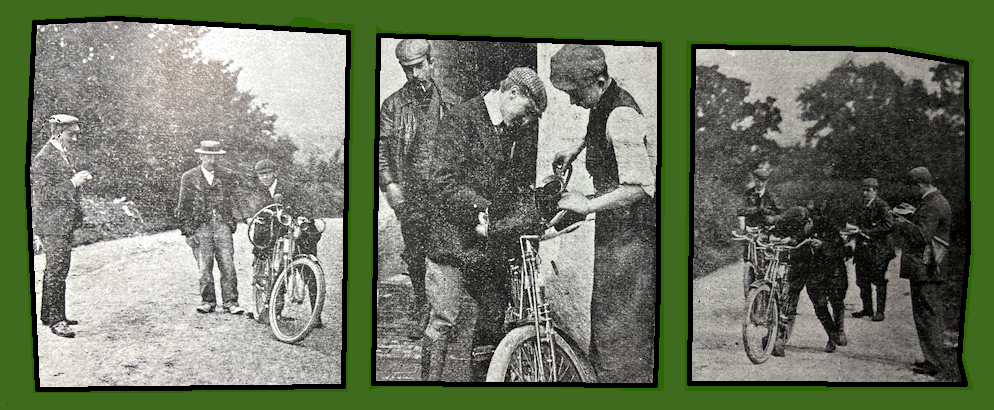

Farnham Road, meeting the hill which carries the road up to the top of the Hog’s Back. Notices had been issued the evening before, stating that this was to be the compulsory hill, and that every machine must climb it, with or without pedalling, the penalty for failure being the loss of 10 marks—rather a serious deduction from a possible total of 100 marks for the whole of the trials. However, every machine rode the hill, mostly without any pedal assistance whatever, the only variations being the Kerry and Ormonde, which stopped at the bottom to tighten their somewhat slack belts before breasting the hill, and the Jap, the belt of which broke when half-way up the hill. However, as this was a hill test and not one of belts, the Jap was given a second trial, when it acquitted itself well. So the result of the test on the compulsory hill was that no machine lost any marks. At the top of the hill, Mr JW Orde, secretary of the Automobile Club, stopped the riders, who were then sent down the hill again, with instructions to pull up on their brakes whenever they heard a whistle blown. Two tests were given to each machine, but the results were by no means conclusive. There was a disturbing element introduced by the uncertainty as to when the sound of the whistle would occur, and there was frequently hesitation in the application of the brake. Moreover, the riders were compelled by the judges to keep their engines running, and thus a most unnatural condition of affairs was introduced. The rider’s instincts told him to shut off his power and to watch the road in front; official instructions compelled him to keep the engine and to listen for some unfamiliar sound. The best stoppages were made within 10 yards on the upper portion of the hill, but some riders took 60 yards to pull up. On the steeper portion the best result was a check in 25 yards, and was worst ran to 100 yards. Seven machines secured full marks, and six only lost one

mark. We should like to see a well planned brake test, where each machine was compelled to attain a certain pace, the rider to apply all brakes at a certain mark, and to come to a dead stop as expeditiously as he could. As it was some riders were travelling fast and some slow when the whistle sounded on the Guildford Hill; some riders could stop the engine quickly, and some hesitated over the operation, and so the tests were, at the best, but a makeshift. After these tests the riders went off to Basingstoke and returned to the Palace. There were three mishaps on this day. Coles, on the Brown motorcycle, in some mysterious way fractured the frame of his machine and had to abandon the rest of the run at Guildford. He returned to the Palace and changed his engine gear over to another frame. The Evart-Hall, through a faulty dismount, bent its crank, and one rider broke the gudgeon pin and had to return by train. On the Thursday the long Eastbourne run, via Sevenoaks and Hailsham, was repeated, and for this 31 riders set out. On the return journey the rain, a heavy, saturating downpour, driven by a relentless south-west wind, was met as the Kentish hills were neared. At the foot of River Hill the officials were found, and with AJ Wilson timing at the foot the men were dispatched for the climb up this famous gradient. The wind was favourable, but on the stiff portion of the hill the riders were sheltered from it by the trees. The first to appear was Wright on his Ormonde. He came up with his usual smile, giving a few easy strokes of the pedals, at nearly 20mph. For nearly two hours the riders were coming up at intervals. The officials had been at their

posts nearly an hour before the first arrived, and they waited for over an hour after the last had gone through, waiting for three others who did not turn up. And for the whole of those four hours they walked up and down in the incessant pouring rain with no shelter and nowhere to rest the weary limbs! Such are the pains and penalties for enthusiasm! The best performance was by the Jap, which came up the hill in 2min 3⅗sec, giving a speed of just about 20mph. The rider of this machinel had started on the trials quite unfit, and the first day had punished him severely; so much so, in fact, that he could not push his machine up Westerham on the next day. But on River Hill he retrieved his reputation, for he rode splendidly, pedalling so as to get the best work out of his engine. FW Chase on a Chase motorcycle did second best in 2min 12⅖sec and Wright, on the Ormonde, was third, in 2min 13sec. One machine, the Evart-Hall, surmounted the hill without pedal assistance, and the Bradbury, Phoenix, Alldays, Castell, and Ormonde got up with but the merest touch to the pedals, which may have been quite unnecessary. Some riders had to pedal furiously, and five machines had to be pushed over the worst section. The run through Sevenoaks and Green Street Green was through gradually slackening rain, and thence through Wickham some dry patches were met, so the day finished at least better than it at one time promised. The Jehu shed its clutch on the homeward journey, and was brought back by train. Tyre troubles delayed Aug van Hooydonk and A Hoffman. Both of these are in the Private Owners’ class, and had gone through so far with scarcely any trouble, so it was rather hard to catch tyre trouble so near the close of the trial. D Elyard Brown, another private owner riding an Ormonde, met with a nasty smash whilst travelling down Polhill. A miller’s cart came out of a side road right across his path, the carman taking no step to see that his way was clear. Brown was suddenly confronted with the choice between three evils, the cart, a group of pedestrians, or the hedge. He chose the latter, and then found that oaken posts and barbed wire were included in the hedge. The front of his machine was wrecked, but the rider fortunately got off with a few facial scratches. It was very hard lines, because he had done so well all through; he was riding purely for the fun of the thing, and he was so near the end of the trial. The last day dawned with no great promise, but it turned out very well. The run was to Worthing, but on the previous ride over this course, via Horsham, the police were about, and despite cautious riding in the ‘trappists” district, names and addresses were taken, and it was reported that the police were all ready for a second haul. So, with the utmost secrecy, a new route was planned, via Brighton. Fresh maps were prepared and distributed just before the ride commenced. The Surrey police waited in the ditches, and were astonished that the motorcyclists did not come by. Then they received a telegram saying that the riders had reached Brighton via Crawley, so rapidly the telephones and watches and constables were bundled into carts and sent over to Crawley, where the trap was fixed up. But a friendly pedestrian stood and warned the riders, who crawled through the trap, whilst the twice-frustrated

police fretted and fumed. What a pity they have nothing better to do with their time! Thirty men set out, and the first arrival reached the Palace very early in the evening and placed his cycle in the rack with a huge sigh of content. All but two of those who started completed the day’s run and then the machines were given their final cleansing preparatory to the work of Saturday. It had been hoped that by Saturday morning, when the final inspection and the speed trials on the track were to take place, the number of marks gained by each machine for reliability on the road—which means punctuality on all the sections—would be available for publication. But numerous discrepancies were discovered, and more still have been pointed out by the riders themselves. It is curious to note the reason for some of these variations. The observers or timekeepers for the various controls were, as far as possible, appointed from the neighbourhood, so that they could reach their posts with the least amount of inconvenience, and for the purpose of timing the men, the observers were instructed to set their watches by the clock at the local post office. Whether the post office clocks—which, one would unhesitatingly say, would constitute about the nearest approach there is to a standard of time—were inaccurate, or the watches ran badly, remains to be found out, but it is an undoubted fact that the timetakers’ watches often disagreed with the riders’ own time-pieces and, as the latter were usually set each morning by the official watch and compared again at night, it was obvious that the timekeepers’ watches had gone astray. A good many instances of a variation of from two to three minutes were observed, but at two controls the error was 17 minutes and 22 minutes respectively! The result of these errors is that many riders are debited with adverse marks for lack of punctuality, and protests innumerable are flying about. However, the club is anxious that no machine should be harshly dealt with, and so each complaint is being investigated, and the final awards on reliability will be arrived at on Thursday next, when the judges meet to go over the whole of the reports.”

“ON SATURDAY MORNING THE JUDGES were again at work, Capt the Hon WH Ruthven and Mr GF Sharp minutely examining every machine and modifying and correcting the marks given under the head of ‘convenience’. Each fitting was examined, and marks were deducted in cases where there was proof of the inability of the fitting for the work demanded of it. Such a minor point as the comparative cleanliness of the crank case was fully considered and, where it was evident that the engine was not cleanly in working, marks were deducted. Finish and style, accessibility of valves, convenience in the matter of lever position, oiling devices, portable stand, and so forth were all carefully weighed up and the marks given accordingly. Silence was judged during the speed trials by Mr CW Brown, and in the end the machines which were placed at the head of the list on the score of ‘convenience’ were the Chase, the Matchless, the Phoenix, the King, the Bradbury, the Ariel and the Jap. A few machines had weathered rather badly, but, on the whole, the appearance of the machines and the scantiness of any signs of wear were really remarkable. With a little more attention paid to some details by a few of the makers the impression made by the machines would be more than

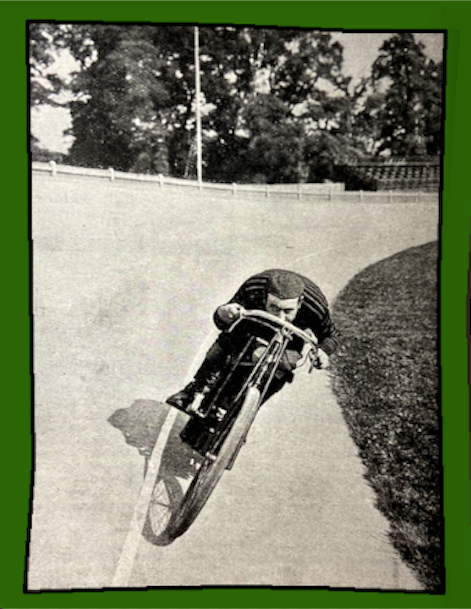

doubled. The marks for weight are awarded on the basis of one mark for every twenty pounds saved. So, whilst a machine weighing 170lb gets no marks, one weighing 150lb or less gets one mark, and one weighing 130lb gets two marks. The highest marks obtainable are five for a weight of 70lb or less. It is a curious fact that the machines getting over three marks did not survive the trials, which fact suggests that the weight cannot be kept inside 110lb when heavy tyres, sufficient brake power, large petrol capacity and the many little conveniences required by the rider are all provided. The machines which will appear to score a mark over their competitors on the matter of weight are the Jap, the Griffon, the R&P, the Werner and the Alldays. They are run close by most of the others, including the Bradbury, the Peugeot, the Kerry, the Phoenix, the Ormonde, the Weller, the Werner, the Lagonda, the Castell, the Jehu, the Chase, the FN, and the Ariel. On the matter of price, marks could be gained for every substantial reduction on £70. A machine costing over that sum scored no marks, whilst one costing £35 scored full marks, namely, five. Two machines gained full marks, and of these only the Griffon got through the trials. This was run close by the 2hp Werner, and that in turn led the Bradbury, the Peugeot, the Jap, the Kerry, the R&P, the 2¾hp Werner, the Castell, the Matchless, the Evart-Hall, the Alldays, the FN and the Ormonde. The marks for convenience and brake efficiency are secrets with the judges, and no information is being published beyond the groupings already given. But the speed trials on the track enable us to again calculate the awards under this head. For the purpose of the trials, the machines were conveyed to the track under official observation, nothing being permitted to be done to them. During the week the pulleys had been secretly measured and the measurements recorded, and just before the speed trials they were checked over again, every one being found in order. The machines were sent on in batches of four or thereabouts, and set to do five miles at their best pace. Considerable variation in the speeds were at once apparent, FW Chase, on the new aspirant for public support, the 3hp Chase motorcycle, covering the distance in 8min 8⅕sec, or 37mph, thus gaining four marks out of a possible five. The next fastest was AC Wright on the 2¾hp Ormonde, whose time was 8min 27sec, giving a speed of 35½mph. The Ormonde thus gained four marks. Other good performances were as follows: 2¾hp Matchless, 9min 18sec, 32½mph, 3 marks; the 2¾hp Bat, 9min 20⅖sec, 32½mph, 3 marks; the 3½hp Booth, 9min 25sec, 32mph, 3 marks; the 2¾hp King, 9min 25⅖sec, 32mph, 3 marks. The average time was between 10 and 11 minutes, or just inside 30mph, and the majority did something around these figures. Only three machines exceeded 13 minutes. Professor CV Boys and Mr J Pennell were the technical judges overlooking the speed events. Mr O’Gorman, who has worked like a Trojan at the judging, had gone off for his well-earned annual holiday, so was absent on the last day. It is both interesting and instructive to analyse the motor-bicycle, and to note the behaviour of each component part of the machine during the trial. Careful consideration of the following notes will give readers the best birdseye view of the trials which we could present. With the summary before them, makers will be able to devote particular attention to those details which are proven to be most in need of attention, and riders will be able to make a better choice when purchasing a machine if they know what to watch for. We will first of all state in a few words the behaviour of each essential part, and then amplify where necessary—(1) Motor: Scarcely any troubles whatever. (2) Carburetters: Not many difficulties. (3) Ignition: Only minor troubles with the high-tension (coil and accumulator) system. (4) Silencers: Quite satisfactory in nearly all cases. (5) Frame: Quite efficient. (6) Tyres: Almost endless troubles in most cases. (7) Belts : Seldom out of trouble. (8) Clutches: Thoroughly useless and dangerous. (9) Chains: No trouble. (10) Brakes: Generally excellent. (11) Lamps: Could be stronger. (12) Lamp brackets: Too weak in many cases. (13) Saddles: Unable to stand the wet. (14) Portable stands : Invaluable. (15) Gauges for oil or petrol: Most useful. (16) Tanks, mudguards, pedals, foot-rests: No trouble. The behaviour of the engine generally was remarkably good: we only heard of a two to one gear breaking, and the failure of a screw holding the gudgeon pin. Otherwise 40 motors carried out their part of the work admirably. The frame of the Brown motorcycle gave out on the run down the Hog’s Back, and a new one had to be substituted to enable the machine to be ridden next day. The cause of the failure has not been made public. Otherwise frames behaved well, and there were no signs of weakness about forks or steering heads. Tyres were the most unsatisfactory feature. On the flinty roads, saturated with water, punctures were often occurring. The bad fit of inner tubes also caused nipping and bursting. And yet we were told by the rider of one of the Bradbury machines that he had ridden his machine to London from Oldham and had gone right through the trials, covering altogether about 1,200 miles, and had not found it necessary to even inflate the tyres the whole time. They were Clinchers. Tyre makers must really endeavour to supply something good for next year. Belts were the cause of endless trouble. Most riders carried spare ones, whilst one had quite a stock of them. Hooydonk on his Trimos had fitted double pulleys on the engine and on the rear wheel, using two belts. The result was very good, because they would adjust themselves one to the other and then divide the driving strains. The chain-driven Jehu had few chain troubles, whilst the only other chain-driven machine in the trial withdrew because its engine was not powerful enough. Clutches were abominations. Makers seen, to forget that the clutch used for a free-wheel cycle is quite useless for a motorcycle. With the latter the clutch is running free nearly all the time; the pawls are depressed in their chambers and springs are under constant compression. The result is that when mud works in, as it must do with constant movement between the inner and outer members of the clutch, the pawls get glued down, and so a free-wheel both ways is provided. After the muddy rides the machines invariably arrived in such a state that the rider could give no pedal assistance. A liberal flooding with paraffin was the only preventive and cure. Stronger clutches and small guards to protect them are required. Chains, having little work to do, give no trouble, whilst the other matters set out above are such as can easily be rectified.

WE SHALL NOT BE SURPRISED if the trials which come to an end on Saturday, after nearly a fortnight and covering well over a thousand miles, should produce results which will please nobody. In the nature of things the test has been made most severe, because if this were not done an opportunity to scoff would be provided. Moreover, it has been hedged around with restrictions which are necessary, perhaps, in order to secure that the straightforward entrant and rider shall not suffer through the sharp practices of an unscrupulous person; but these restrictions bring about an artificial state of affairs, and thus a machine may lose points through some absurdly petty incident. Thus, for checking purposes, controls are established on the routes 10 miles apart, where the times of the riders in and out are checked. But if a competitor takes a wrong road and thus misses a control, his loss of marks is serious, and whilst it may have been that a longer distance or a worse road has been encountered through the error, yet that machine stands falsely condemned. This is a simple instance of the difficulty of scheming out a set of trials which shall be absolutely fair, and give an accurate indication to the public of the relative merits of the competing machines. When the scheme was first mooted there were many representatives of the trade who said that the test was too easy. Some wanted the daily distance to be150 miles, and they even talked of a 200 miles’ trip—’something really long.’ There was a large substratum of truth in their statements that a motorcycle can easily do its hundred miles or more in a day, and as for 1,000 miles, why, and well-made machine would show no signs of wear after it; in fact it would be in much better order at the end of its 1,000 miles than at the start. All this is perfectly true, but the argument is based upon one factor alone. Instead of that, there are other factors to consider which, in importance, overshadow the one stated. The rider is the chief item in the scheme, and we will jot down, without a word of exaggeration, his programme for the first day of the trials. He had been kept at work for weeks preparing for the trials, and had finally got his ideas into practical form. On the Monday he had seen his machine through the judging, weighing and sealing stages, and had been set in a whirl with a recital from the officials of the hundred and one things he had to do, and the thousand and one things he must not do, under pain of disqualification and worse penalties. Up early on Tuesday morning, consumed with anxiety as to how his machine had weathered the torrential rains of the preceding 24 hours, and with the cheerful prospect before him of treacherous roads, and a threatening sky. Breakfast, and then down to the tent in the grounds of Crystal Palace, where the machines were partly protected from the elements. A space of 20 minutes is given for preparations, and then the word to go is given. The machine has to be pushed the whole of the way up the Rock Hill, out of the grounds and on to the parade—a cruel, wicked arrangement, resulting in most of the men arriving there badly blown, some of them really being too fatigued for a prompt start. But they are whipped up like a Siberian convict gang, and at the hour of starting the riders are despatched over heavy and greasy roads. The course is a very hilly one in Kent, and at about midday the rain commences. It pours down in torrents, and side-slips occur or—what is really worse—are feared all the day. In the end the men, tortured by fear of road accidents and by the needs for keeping to the schedule, and in the direst of personal discomfort and racked by the knowledge that the rules do not permit the machine to be touched until the morning, arrive at the Palace in a state which we have only seen approached at the close of a gruelling 24 hours’ road race under the worst conditions: No wonder some said straight-away that it -was not good enough. No wonder the rules had to be relaxed, the riders being allowed to clean the machines down. It was certainly a most unfortunate and unpropitious start for a fortnight’s series of trials, and it says much for the pluck of the average motor-cyclist that the next day’s sun dispelled the gloom from the minds of the majority, few, indeed, holding to the over-night resolution to abandon the trials. One other matter has made itself felt by the riders, and that is the persecution of the police. The latter having found out about the trials, the routes taken and likely times at which the riders would be at certain points, must also have been made aware of the fact that the rules stipulate for a slow pace, in order that the law of the land may be observed. Yet with that sneaking underhandedness developed be the rural police in recent years, electrical traps have been set, and the riders have been snapped up wholesale. Besides the ignominy of the proceedings, there will now be the need for an endeavour to counteract falsehoods about the speed, and the waste of time in answering summonses. The whole thing is disgusting. So much for the personal element, which, it will be seen, is extremely powerful, and in itself capable of completely wrecking the scheme even though the machines are quite equal to the task. The hills and the soddened road and the pitiless rain, however, are all arrayed against the machines. A very hilly series of routes has been selected and, as this was scarcely anticipated, few machines have been entered for the trials geared sufficiently low. The result was seen at Westerham on Wednesday, when only two machines surmounted the hill easily, and only 10 all told got up without a dismount. Of the remaining 24, five were able to reach a fairly good elevation, and either by restarting the machine or by walking were able to cover the last of the stiff gradient without undue struggles, but the remaining 19 had a big gruelling in

their endeavours to push their machines up the 1 in 6 gradient of Westerham. This hill is the most wicked that we have south of the Thames, and we do assert that, being a freak hill, it almost requires a freak machine to surmount it. At any rate, the machine requires to be specially geared for the task, but the gearing suitable for Westerham would be quite unsuitable for a thousand miles’ run, because of the constant danger of overheating an engine running at high speed when the machine itself was travelling slowly. Then again, take the matter of wet roads and heavy rain. Side-slips will occur, generally in an endeavour to avoid some badly driven horse-drawn vehicle, and the result may be a broken handlebar or a bent crank, and the marks lost through such an incident may be sufficient to prevent a machine getting its first-class certificate, which is an obvious absurdity. A chance spot of rain on a sparking plug again will cause a distressing amount of misfiring, and when.this occurs on a hill a dismount and a walk may be the consequence, with possibly a loss of marks because of a late arrival at the next control. Thus we see that, unavoidably, to a large extent the trial is an unfair one, because no ordinary rider would dream of subjecting his machine to such usage. He would steer clear of the unridable hills; he would not turn out for a hundred miles’ run in the pouring rain, or, if rain came on, he would at least consider the advisability of seeking shelter; he would not descend to the absurdity of depreciating the qualities of a machine because of a side-slip or a short circuit over raindrops, and moreover he would consider himself, and when he had become fatigued would cease work for the day. Consequently, as none of these considerations are extended to the motorcycles in the trials, the absolute artificiality of the scheme is at once apparent, and writing as we are, when the trials are not half over, we fully anticipate that the number of first-class machines which actually get the first-class certificates to which they at any time fully entitled will be small indeed. Should this come about, the trials will have proved themselves absolutely valueless and false in their results. Entries had been received of 35 machines from the trade, and of 13 machines from private owners. The cycles were taken to the Crystal Palace on Monday morning, and there stored in a toy tent on the lawn just below the north end of the terrace. The tent was old and porous, it was pitched on sloping ground, and was just about half as large as it should be. Now Monday turned out wet, is fact, the word ‘wet’ is totally inadequate to the occasion, for at times the rain fell in sheets, whilst the sky was rent with lightning flashes. Needless to say, the ground on which the machines stood was like a swampy morass, and the drippings from the roof (so-called) directed themselves on to spotless nickel and polished metal of the machines in a fiendish manner. This sort of accommodation is now the best that the Crystal Palace authorities can do, because of the terms of its fire insurance policies. It appears that policies were rendered void by the presence of cars and cycles during the trials of last year, and so tents will be provided for future events of the kind. But we do say this, that a tent is inadequate for the protection of £2,500 worth of cycles, such as is now collected at the Crystal Palace, and even the presence of a watchman is really not enough to prevent the possibility of theft. Should these trials be repeated a new rendezvous must be found. Monday was spent in the examination of the machines by the judges, consisting of Capt the Hon WH Ruthven, DSO, Professor CV Boys, FRS, Mr Mervyn O’Gorman, Mr J Pennell and Mr GF Sharp. During the examination the machines were weighed and numbered and vital parts were sealed. The first duty of the judges was to award marks for ‘convenience’, 10 out of a total of 100 being allotted for this. The points considered were efficiency and rigidity of mudguards, accessibility and convenience for lubricating, petrol capacity, ease of replacement and repair, provision of a portable stand or luggage carrier, excellence of brakes and quality of work, of design and of finish. The work required to be well done, and so it took a long time. In fact, it was quite dark when the day’s work was over. In all, 44 machines were submitted to the scrutiny and the day closed with a meeting of competitors and officials, when the arrangements were explained and discussed. The marks to be allotted for certain features of the machines are as follow: for reliability and regularity of running, 70 marks; for convenience, 10; for speed on the track, 5; for lightness, 5; for cheapness, 5; for efficiency of brakes, 5; total, 100. Under the head of reliability 10 marks per day can be lost. If the speed be less than the minimum over any of the 10-mile sections of the route 2½ marks are deducted, whilst for late arrivals at control anything up to 10 marks can be lost, but not more than 10 can be deducted for any one day. We have already explained the item ‘convenience’. On the last day, Saturday next, the machines will be sent on to the track, and, without changing gear or making any preparations, they will be set to cover a certain distance at their best speed: 40mph secures full marks; 35mph, 4; 30mph, 3 marks; 25mph, 2; 20mph, 1; no marks for any less speed. In order that the cheap low speed machine shall not suffer, the item ‘cheapness’ is introduced. A cycle costing £35 receives 5 marks; one costing £40 gets 4 marks ; £45, 3 marks; £50, 2½ marks; £55, 2 marks; £60, 1½ marks; £65, 1 mark; £70, ½ mark; and above £70, 0 marks. And weight also is penalised on this scale: a cycle weighing up to the limit, 170lb, receives no marks; one weighing 150lb or less, 1 mark; 130lb, 2marks; 110lb, 3 marks; 90lb, 4 marks; and 70lb or less, 5 marks. The awards for brakes depend on their efficiency as demonstrated at a test to be included in one of the runs this week. As to hill climbing, no marks can be gained or lost unless the machine falls to climb an average hill to be indicated on one of this week’s runs. But the doings on Westerham will be recorded on the certificates for the information of purchasers.

“THE GREAT FORTNIGHT’S TEST has come to an end, and the general feeling is that the motorcycles have made an astonishing display. The test had been made as complete and comprehensive as could possibly be done, the object which the organisers consistently kept in view being to instruct and inform the public so that when orders are placed in the autumn, buyers will have certain information before them on the bona fides of which they could rely to help them in the choice of the machines which would suit their individual requirements. Any potential purchaser who has harboured the thought that the motorcycle has not yet been shorn of its crudities, or that it would be judicious to wait until the machine has been made more reliable, most dismiss all such ideas from his mind in the face of such evidence as is now placed before him. From the very first issue of this paper we urged the trade to go ahead and perfect the motorcycle—to develop it upon the lines of completeness and reliability, and to give the buying public the best bicycle at the lowest cost. We believe that the trade has risen to the task, and we now feel that machines of any of the makers which successfully underwent the arduous trial which has just come to an end would be good and splendid investments.”

“WHEN EVERYTHING IS TAKEN into consideration; when it is remembered that the scheme was (according to the judgment of the firms who held aloof) not one to really permit a machine to show up to advantage; when it is considered that under the same conditions of rain and mud, of puncturing roads, of heavy traffic, of wearied nerves, and of all the other distressing elements of that fateful 1,000 miles, these seven machines went through from end to end with a minimum of trouble, four of them losing not a single mark because of lack of punctuality at any one of the hundred controls, and the other three losing no more than could be counted on the fingers of one hand, we do think that they deserve the fullest praise, and that their drivers are to be most highly commended upon a performance which will be memorable. Of the machines which gained second-class awards we shall have something to say later. Taking the machines in their alphabetical order, the first is the Bat, ridden by Mr EB Blaker, a well-known amateur sportsman in the South of England. The machine was built by the Bat Motor Manufacturing Co, of Beckenham Road, Penge, SE. It is driven by a 2¾hp MMC engine, disposed vertically in the frame, a belt of the

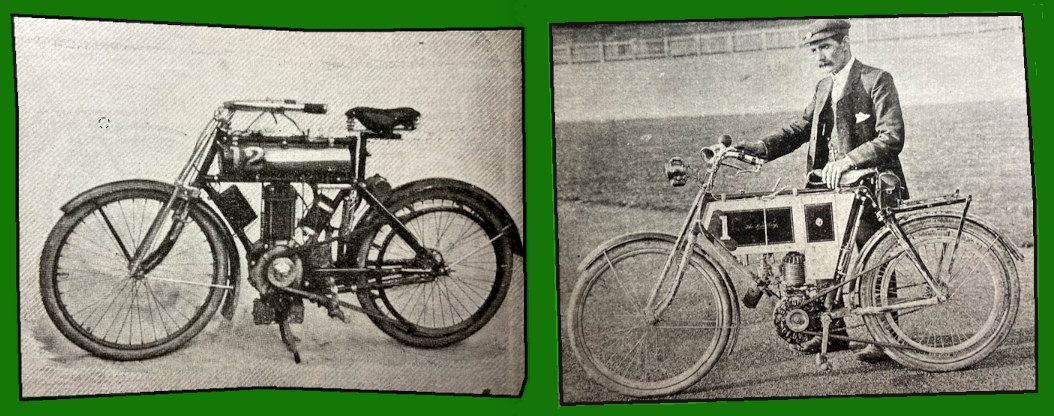

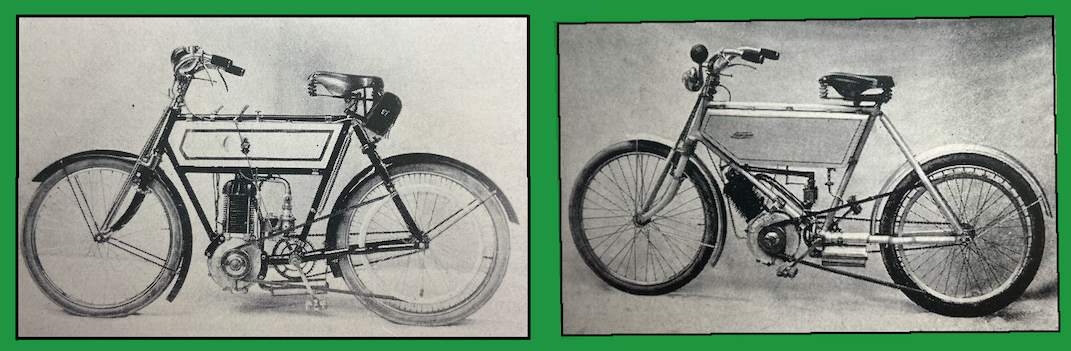

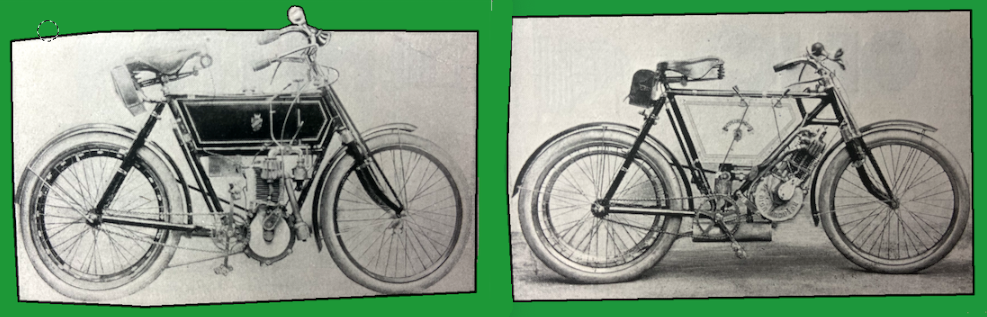

popular V-shape, specially made for the company, being utilised for power transmission. This belt is remarkable for its wearing properties. Those used in the trials were exceedingly satisfactory. A spray carburetter, high-class batteries and coil, two brakes, the one on the back wheel being specially designed to act on a drum, and various effective patent devices are used on the machine, notably the Bat switch and brake lever, the special pulley, with rocking pawls, the special belt fastener, and a new and comfortable shape in handlebars. A most convenient feature is the new stand, which supports the machine in such a wav that, using the motor as a fulcrum, either front or rear wheel may be lifted clear of the ground. The machine is fitted with Dunlop motorcycle tyres. The batteries are very conveniently placed, and are quickly get-at-able. The machine has no pedals, but so good is the carburetter that the engine responds at once to the release of the valve lifter, and the fixed footrests are easily gained, whereas a flying pedal seldom is. The Bat sells at £45, the spring frame adding another £5 to this cost. The Bradbury, ridden by Mr James Hall (whose Lancashire brogue resulted in the officials thinking that his name was ‘Jimshall’), was made by Messrs Bradbury and Co, of Oldham, who have long been noted for the excellence of their cycle workmanship. It is built to Birch’s design, in which the crank bracket of the motor is of malleable iron, and forms an integrals part of the frame, a face plate being made detachable should t necessary to examine the fly-wheels or bearings. The engine is of 2hp, is placed vertically, and being made throughout at the Oldham works, any replacements are most readily obtainable. The contact breaker is of a special type, to ensure a perfect contact, and, with the trembler coil used, a most satisfactory ignition system is provided. The combined switch and exhaust lifter is a very simple and effective contrivance. The surface carburetter is supplied as a standard, but a spray can be fitted at a small extra charge. Clincher tyres are supplied, and those fitted on the machine illustrated behaved splendidly on the trials. The Bradbury sells at £45 for the 2hp size, and £45 with a 2½hp engine. The Chase motorcycle, ridden by Mr FW Chase, is

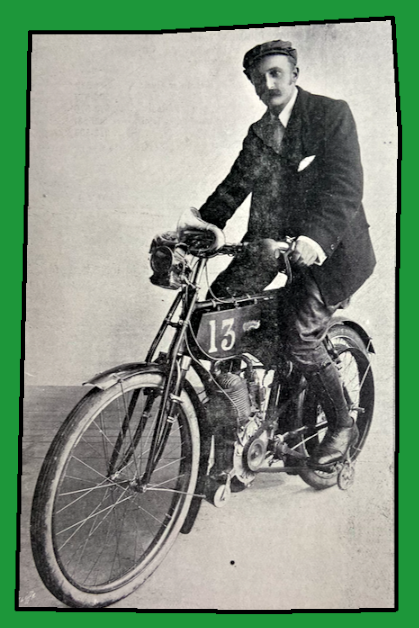

made by a newly-established firm, Chase Motors, of Station Road, Anerley, SE, the two brothers AA and FW, having brought into the business their wealth of experience. And probably few riders in this country have had more experience than they have, for it must be over five years ago when they were experimenting with motor tandems for pacing purposes, and since then their attention has never been diverted from the production of a satisfactory motor-cycle. Their manufacture has now been seriously entered upon, and it must be gratifying to the two brothers that the machine should have made so good a showing on its first appearance. The ma-chine is specially designed to take a 3bhp Ariel engine in a vertical position, well forward of the pedal bracket. This position not only gives the machine perfect balance, but it allows ample clearance for the pedals. Convenience and accessibility are particularly claimed for the machine, every nut, both the valves, and all other parts being accessible to hands and tools. A Longuemare carburetter is used, levers for adjustment of air and gas being taken to convenient positions, the levers being cone-adjusted, so ensuring perfect movements. The large tank carries petrol (1½ gallons), oil, batteries and coil, a sight feed oiler is fitted, and the two brakes give ample control, but if desired a back-pedal brake will also be supplied. The belt is a Chicago raw hide of V pattern, and it is worth noting that one belt went right through the trials to the last day, and then was only broken through something dropping from the carrier and getting twisted up with the belt. A very comfortable position has been provided for the rider, and the portable stand and carrier is a convenient item. The 3hp Chase sells at £52 10s, and it is good value for the money. It bore away the palm for style and finish in the trials. The Kerry motor-bicycle, entered and ridden by Mr WH Hayes, of the Empire Motorcycle Co, Bird Street, Oxford

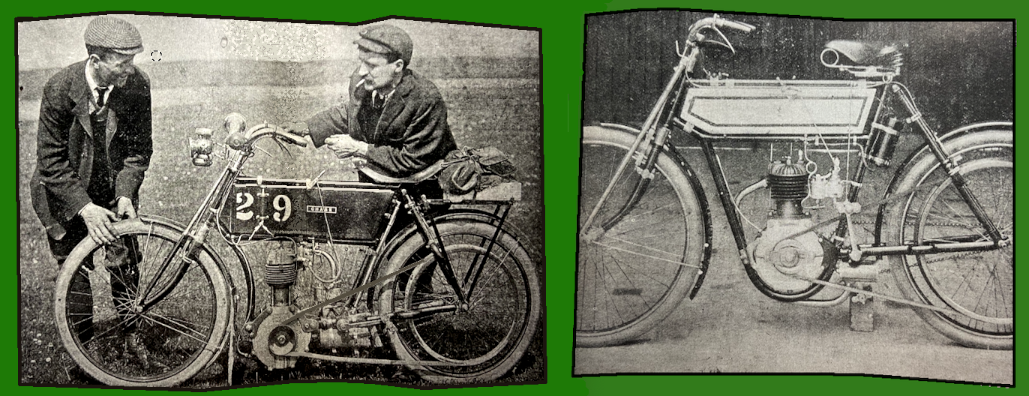

Street, London, W, is the production of the East London Rubber Co. It is a well-designed machine, the motor, of 2¼hp, being placed in the loop of the frame. Being exceedingly well made, its efficiency is very high. The Kerry carburetter is a simple and effective device, and it permits the engine to be quickly and easily started. A V-shaped belt is used, on accurately shaped pulleys. There is ample capacity in the tank for a journey of 100 miles. A special fitting which gained much notice and admiration during the trials, was the Empire support, shown fitted in the illustration. This is a pair of legs with small wheels at the extremities. When extended to their fullest they serve as a jack, or by lowering them by means of a backward motion of the foot they spread out, and in the event of a skid they stop the sliding action by coming into contact with the ground…it is only during the past few weeks that the maker has been able to keep pace with his orders. The Kerry, with the Empire support, sells at £44. The King motorcycle was ridden by Mr W King, of W King and Co, Bridge Street, Cambridge. It has a 2¾hp MMC engine, placed vertically and forward, driving by a large V-section belt, a De Dion or Longuemare carburetter being used. The frame is amply strong, a girder head being employed, and parallel tubes being used above the engine. The 26in. wheels are shod with Clincher tyres, well mudguarded, and a portable stand and carrier facilitates repairs, a special feature of the latter being the fact that the luggage need not be disturbed, the stand swinging away clear from beneath. Of brakes, there are two, front rim and back-pedal. The coil is of the trembler type, and two accumulators are provided, connected with a two-way switch, and placed very conveniently in a wood box. A petrol gauge is fitted, lubrication is by a sight feed pump, and generally the machine is well equipped and provided with every possible convenience. The machine went through the trials exceedingly well, making a good impression by its silence, its regularity of running, and its substantiability; its performance at the brake tests was also amongst the very best. The machine sells at £50, and is to be highly recommended. The Ormonde motorcycle, ridden by Mr AC Wright, is made by the

Ormonde Motor Co, of Wells Street, Oxford Street, London, W. It differs from most other designs in that the engine is placed more to the rear, behind the seat diagonal, a short belt drive to the rear wheel resulting. The machine has a long wheel base, and riders of it say that it is exceedingly steady in the running. The whole of the space in the frame is left available for the storage of petrol, oil and ignition apparatus, so that the machine is neat in appearance. The engine is a 2¾hp Kelecom, well designed, and splendidly made; it is fed by a, spray carburetter of a particularly good type, one which is certain in action and simple to manage. The ignition is by accumulators, contact breaker and coil, the batteries and coil being placed in the lower cupboard of the tank. The petrol tank holds seven quarts, and a float inside, connected to a pointer on a segment outside of the tank, acts as a petrol gauge. Lubricating oil is carried at the rear end of the tank, pipes conveying the oil to a plunger pump, of the pattern introduced by Mr Hooydonk, on the top tube in front of the rider, and from thence to the engine. The great advantages of sight feed lubrication are thus provided. A gauge shows the contents of the oil tank. It is claimed that the position of the engine ensures that it shall be considerably more free from mud and wet in dirty weather than most other makes, and this is an undoubted advantage.

The machine is well mudguarded, and efficient rim brakes are provided. A combined valve lifter and switch is used, and, with the handily placed throttle lever, the control is made perfectly easy. The Ormonde, with a 2¾hp, engine, sells at £50. The Werner motorcycle, ridden by Mr Young, is made by Werner Motors, Regent Street, London, W. The Werner was the pioneer motorcycle, and it has never lost the good position which it has held ever since. The engine on Mr Young’s machine is of 2hp. It is placed low in the frame and vertically, and drives by means of a flat belt to the rear wheel. The engine pulley is leather lined on a new principle, and slipping is prevented by this means. The carburetter is of special design, and is simple to handle. The ignition is, as usual, by batteries and coil, and great convenience is given by the transparent window to the contact breaker, whereby the spark may be examined without troubling to remove the cover. The tank is of large capacity, two brakes and wide guards are fitted, and a portable stand and luggage carrier are provided. The tyres are 2i Dunlops, with thickened edges. Lubrication can be effected from the saddle, a plunger pump being placed the left-hand side of the tank. The Werner is very silent and steady in running and is invariably successful in any task that may be demanded of it With a 2hp engine, which passed through the trials so satisfactorily, the Werner sells at £45.”

“TWO CURIOUS POINTS in connection with the winners. Happening, by chance, to note down the positions of the engines on the machines which gained first-class certificates, we were surprised to find that, of the seven, five had upright engines (the Chase, King, Bradbury, Bat and Werner), whilst the engines of the other twe (Kerry and Ormonde) have but a slight slope. Is this a mere coincidence, or does it point to any great advantage accruing from the use of a vertical engine? Another point worthy of notice is that in the five machines the engine forms an integral part of the frame. This feature has been somewhat questioned in the past, and the Bradbury, by the use of a malleable iron bracket casting, has overcome the objection, which was to the use of a aluminium in the frame. But the equal success of the others would show that there can be nothing radically wrong with the idea.”

“THE 1,000 MILES TRIAL for a motor cyclist is just as much a question of the man as of the machine. A hundred miles a day for ten days is nothing when on tour, but it becomes a different thing when done in open competition. There is always a nervous strain on the man who intends to do his best either for an employer or for himself. The knowledge also that he is constantly under surveillance from observers and judges does not tend to soothe his temperament. The motor cyclist who gets through a 1,000 miles trial creditably, in our opinion, has done a better performance than a car driver under similar conditions.”

“WE REFERRED TO THE MISPLACED activity of the police on the occasion of the recent motorcycle trials. The last act of the comedy was played at Horsham Police Court last week, when some of the riders were called upon to listen to the garbled evidence of the ditch-haunters and to pay up. Whatever doubts one may have upon the conflicting evidence of ordinary cases, thse who knew the conditions and observed the riding methods obtaining in the trials could only feel contempt for the manner in which the police had hatched up the cases. The magistrates would give little heed to the statements of the defendants, but levied fines of from l0s to. £1 with costs amounting to about 7s. in each case. The secretary of the Auto-Cycle Club had taken the trouble to write to the magistrates and officially acquaint them with the nature of the trials, and this fact may account for the comparative lightness of the fines.”

Having looked at the 1,000-mile trial as reported by The Motor, here’s the introduction to the trial as it appeared in The Motor Cycle—and the new kid on the block clearly wasn’t impressed by the organisation.

“IT WAS CLOSE ON ten o’clock on Monday morning last week when we arrived at the Crystal Palace, the starting place for the Auto Cycle Club’s thousand miles reliability trials; and as we passed through the great aisles of the huge building and caught a glimpse of the few machines exhibited at the north end, we could not help thinking how empty it looked after the splendid shows we have witnessed there from time to time. Passing through the North Garden we made our way to the tent where the motor cycles were to he stored, and where the weighing-in was to take place. We regret that we are unable to compliment the Auto Cycle Club on the arrangements made for the comfort of competitors and the storage of machines at the Crystal Palace. The tent provided appeared to us more suitable for storing about 20 rather than 50 machines, while the grass on which it is pitched—at least, when we visited it on the ‘weighing in’ day—was nothing more than a swamp, and that a number of valuable motor cycles should be exposed to such conditions while in store must be severely trying to the temper of both competitors and owners, whether manufacturers or private individuals. We may be accused of grumbling, and told that the climatic conditions were chiefly responsible for the swamp, but the worst meteorological conditions, not the best, are those which should be provided for. Those competitors whom we met in the tent were given anything but a good impression to enliven them with pleasurable anticipations of their task, while to add to the dissatisfaction a method of marking the machines for identification was

adopted which, if annoying to manufacturers, was disgusting to the private owner. First, it was decided to mark the machines in large white stencilled figures on the tank side; then it was discovered that, as most of the tanks were aluminium colour, the white was almost invisible. The suggestion that black figures would serve the purpose was then discussed, and finally, as some tanks were aluminium and some black, it was decided to paint on every machine a black groundwork, and stencil the identification figures in white. With the manufacturers, to whom unshipping the tanks and re-enamelling are perhaps but small items, the smearing of paint may not matter, except in spoiling the beauty of the machine for the time of the trials; but to the private owner entering in the trials merely for pleasure such a destructive method of marking is unpardonable. We do not know if the committee, or whoever may be responsible for the matter, gave the question thought, but it surely must occur to the observer of these matters that some better plan, such as a number attached by means of a card or metal plate, clamped to the desired position, would have been far preferable, and would have saved avoidable disfigurement and annoyance. Experience, of course, will be gained in the conduct of the trials, but in such small, yet important, details as those alluded to we cannot but think that some forethought might have been shown, and the strong feeling of protest and annoyance that was evident amongst those present on Monday last week thereby avoided. Between the hours of ten and one the cycles continued to arrive, and as they entered the tent they were weighed and given their distinctive numbers. After all the machines had been duly weighed, notice was given that all competitors were to be present at two o’clock, when the judges would examine their mounts and place their seal on the cylinder and carburetter. During this examination questions were asked as to whether the cycles entered were of standard pattern, and in some cases the engines were started, and all had the cylinder and carburetter sealed. After the machines—43 in all—had undergone this examination, the next meeting of all those interested in the proceedings was held at the White Swan Hotel*, hard by the Palace, at eight o’clock in the evening. Everybody, we regret to say, was not so punctual as were the officials, who took their seats punctually at the time appointed, and not until some portion of the business had been discussed did the meeting-room become really full. Mr Basil Joy, on taking the chair, proceeded to give a most clear and lucid explanation of the routes and regulations. These regulations had been most carefully planned out, and though he could not expect everybody to be satisfied, yet he trusted that all that was possible had been thought of for the benefit of those engaged in the trials, and though these rules might not be all that could be desired this year, yet next year they might hope for something better. Reliability, not speed, was the motto of the trials, and no credit would be given to any rider who finished first during any day. To one point, the speaker continued, he must specially call their attention. He begged to be allowed to remind them to consider other users of the road. The motor industry was at a critical stage, and any mauvais pas of this kind would be likely to bring about great injury to the cause. In conclusion he wished them all success, and begged that if anyone would care to make any suggestion he would be glad to give it his most careful consideration. One of those present suggested that confetti should be scattered at doubtful points while leaving the suburbs. Mr Joy accordingly placed the matter before the committee…We all found the way out of the suburbs most difficulty to follow and inwardly thanked the man who had suggested the sprinkling of confetti in doubtful places. unfortunately there was not enough, but in the evening more was promised for the following day—a promise which, we may remark, was not fulfilled. After taking a few wrong turns we followed several narrow winding lanes, and eventually found ourselves outside the control at Foots Cray, landing in the midst of a posse of riders who had probably exceeded the speed limit. In the control all seemed bustle and confusion, the poor little official—quite a boy—being thronged by the competitors. Among those who passed us we noticed Bucquet, of Paris-Madrid fame, on a 2¾hp Werner. We then waited till all had gone by and made our way to Maidstone, much disappointing the next control, who thought we were late competitors. So far, the day was all that could be desired—no dust and roads in perfect order, a pleasant air and pretty Kentish scenery; we almost wished we were going right through with the other riders…”

* Motor cyclists were still meeting at the Swan eighty years later; I was one of them—Ed.

“OUT OF THE TOTAL ENTRY received by the Auto Cycle Club in both classes—trade and private—there were 44 starters on August 11th for the first run to Canterbury. Twenty-eight survivors safely reached the Crystal Palace on the ninth day, August 21st, and 23 turned up on the last day to compete in the five miles speed trial on the Crystal Palace track—21out of this number successfully accomplished the speed contest…The judges have divided the awards into three classes, and have awarded certificated certificates to the 23 riders named below, a silver medal being given to Mr A V Hooydonk (3½hp Phoenix tricycle) for the best performance in the private owners’ section. Personally, we think that the whole of the competitors who successfully rode through the ten days’ road trial are deserving of all praise. Never has such an arduous task been undertaken by motor cyclists. For any hesitating purchaser to defer buying after this on the score that motor cycles are not reliable would be folly. Even those who from various minor causes relinquished the trial would in the ordinary case of touring have continued their ride after a short delay. It must be borne in mind that if a competitor in one of these competitions is unlucky enough to be delayed even by a burst tyre, he may lose so many marks that it is not worth his while to continue, if he is aspiring to first honours or nothing. In consequence, he relinquishes the ride, and in some instances the outside public might be led to think that the machine he rode is no good. This in most instances is very far from being the case. Below we give a table of the successful competitors:

1st Class: 2¾hp spring-frame Bat, EB Blaker; 2hp Bradbury, Jimshall; 3hp Chase (Ariel engine), F Chase; 2¼hp Kerry, Hayes; 2¾hp King (MMC engine), W King; 2¾hp Ormonde, AC Wright; 2hp Werner, Young. 2nd Class: 2¼hp Alldays & Onions, Simms; 3½hp Booth, Bramley Moore; 2½hp Bradbury, Milligan; 2hp FN, Chappell; 2½hp Griffon, Lambert; 2½hp JAP, Duffield; 2¾hp Lagonda W Gunn; 2¾hp Matchless (MMC engine) HA Collier; 2hp Peugeot, Galley; 3½hp Phoenix tricycle (Minerva engine), A Van Hooydonk; 2¾hp Werner, J Platt Betts; 2¼hp Robinson & Price, Mordell. 3rd Class: 2¼hp Ariel, J Bond; 2¾hp Phoenix bicycle (Minerva engine), Mills; 3hp Rex, FW Applebee.”

“SOME LESS KNOWN MACHINES in the 1,000 miles trials. The King motor bicycle. The 2¾hp King motor bicycle is made by Messrs W King & Co, Cambridge, and was ridden by Mr W King. The engine is an MMC, developing full power at 1,600rpm. The petrol capacity is 1½gal; the spirit is carried in a reservoir between the two top tubes—this also holds the two batteries and the induction coil. Two improvements recently added are a two-way switch and a petrol gauge. The Lagonda motor bicycle. This machine, engine included, is made at the company’s works, the Lagonda Engineering Co, Staines. Mr W Gunn, who rode it, pointed out to us that the horse-power was 2¾, and although the design does not offer any radical changes, it is well thought out and mechanically made. The three levers for air, gas and advance are fitted on the top of the reservoir and work laterally with a semi-circular motion in ratchet guides. The Castell motor bicycle.

This machine, which is made by Messrs Castell & Sons, of 164, Malden Road, Kentish Town, NW, presents several excellent features, both in design and in construction. The engine (a 2¾hp) is designed by Mr WE Fernhead (who, it will be remembered, was one of the first to adopt bevel gear on cycles), and is suspended in a special cradle bolted on to two ear or lug pieces on the front of the bottom bracket, the front of the engine being supported by a T-lug brazed on to the down tube. The valves are large, with flat seating to the inlet. A Longuemare carburetter is provided, the air slide of which can be governed from the top of tank by means of a small hand wheel. The Matchless motor bicycle. The 2¾hp Matchless motor bicycle is made by Messrs Collier & Sons, Herbert Road, Plumstead, SE. As will be seen, the engine (a De Dion) is fixed to the diagonal tube of the bicycle frame, just in front of the bracket. The carburetter, which is of ample size, is also made by Messrs De Dion et Cie. Two accumulators are provided, these being furnished with a two-way switch of the same type as those used on cars. We are also pleased to observe that a very large and efficient silencer is fixed in a horizontal position beneath the frame. This is certainly a step in the right direction, and we hope it will be more generally imitated than it is at the present time.

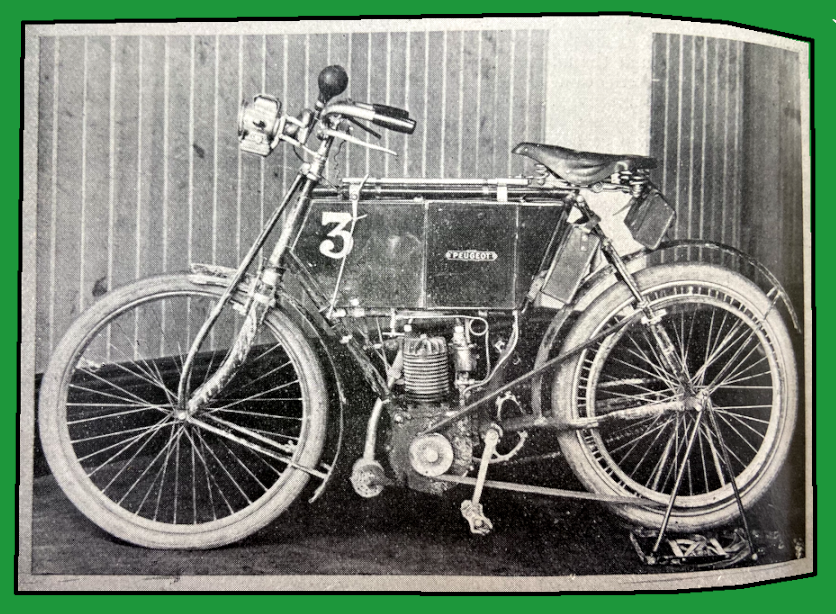

“THIS MOTOR BICYCLE, which was one of the winners of a second-class certificate in the late 1,000 miles reliability trial, is made by the well-known French firm of Peugeot Frères, their name alone being an excellent guarantee that it is a thoroughly reliable and scientifically constructed machine. The English agents are Messrs Friswell, 1, Albany Street, Regent’s Park, SW. The engine, which is of 2hp, forms part of the frame, being securely bolted to two lugs brazed on to the lower extremities of the down tube and the bottom bracket, by which means perfect and permanent alignment is provided. The weight is equally distributed between the two wheels as low down as possible, thus securing absence of vibration. The latest type of Longuemare carburetter is provided, fitted with throttle valve, and jacketed with warm air from the exhaust pipe.”

“LAST WEEK WE PUBLISHED the report of the judges’ awards for the 1,000 miles motor cycle trials. We understand that this is the final announcement from the judges. A further report has been contemplated, but apparently is not regarded as necessary. Now, we would be the last to quarrel with the judges’ awards. We have no doubt whatever they are eminently fair, and arrived at after most careful consideration of the individual performance of each machine. This, however, is not enough, and, while the judges are to be complimented upon the prompt publication of their awards, they cannot consider that their duties are finished until they have supplemented them by a report. For instance, the riding public are anxious to know what is meant by first, second, and third class awards. No standard or definition is given of what these awards are. Further than that, the total marks earned by each machine should be given and the reason for every loss of marks stated. The reliability trials of the Automobile Club are valued almost entirely on account of the system of marking which is adopted, as it enables every student of the trials to see at once why any particular vehicle lost marks. On the cycle awards as they stand, there are many inexplicable items, every one of which no doubt can be made perfectly clear by the judges, who alone have a complete record of the behaviour of each machine. As an instance, we notice in the list of first-class awards a well-known make of machine, which was notoriously bad in the hill-climbing, secures a first-class award, while another which did exceptionally in hill scaling is the recipient of a second-class certificate. Of course, this is not the only reason; there are other matters which the judges take into consideration, but the reason for this difference is not apparent. Again, another instance: A machine which to our knowledge was out of the trial for practically the whole of one day has secured an award in the second class, whereas another rider in the private section received none at all, and only retired for part of the run, and then it was owing to his disinclination to continue in inclement weather. This, again, cannot be the reason for disqualification or otherwise. If so, the machine that was absent for one day must have lost sufficient marks to prevent any award being secured. All this uncertainty only goes to prove our first remarks—that some further details should be published, showing the actual marks deducted on each day. These particulars were published for the first five days. Why were they discontinued?”

“DEAR SIR, RE THE 1,000 Miles Reliability Trials—With the knowledge that heavy deduction of marks for tyre troubles would handicap my chance of award in the trials, I was not altogether surprised to find my performance on the Rex relegated to the category of third-class certificates. But from the public point of view the result is wholly misleading and unfortunate, and I think it is only just and fair to the Rex Company that I should ask you to allow me through your medium to record the fact that not a mark was deducted from the Rex machine except for tyre troubles.

FW Applebee—Entrant of privately owned Rex.”

“DEAR SIR, RE THE 1,000 Miles Reliability Trials—I have read the letter from your anonymous contributor, who signs himself, and doubtless was, ‘A Competitor’. The only. part. of this letter which appears to call for comment is that in which he alludes to the severity of the rules and conditions. He knew these perfectly well before be started, but does not complain until after the trials are over. A great point which your correspondent has missed, as also have some other critics, is that the rules for these trials were framed by representatives of the trade, and prior to the trials more than one of these gentlemen were under the impression that these tests were not severe enough. It was inevitable that we, as well as the manufacturers, should learn something by these trials. This we all expected, but I venture to think that the lessons which the trade have obtained from then, will have a material effect in assisting towards the production of a perfect motor bicycle. There can be no question as to the satisfactory manner in which the mechanical portion of the machines came through, not withstanding the terrible weather experienced, and the unfortunate bugbear of tyre troubles could only be met by observation over every inch of the road. It was never expected that a machine would excel in all the teats imposed. They were designed to produce a good all-round machine, and any machine that has gained a certificate may safely be described as such. There is no doubt that the trials have served their purpose by producing absolutely independent and reliable reports, which, after all, are what alone the public can go by.

F Straight, Secretary Auto Cycle Club.”

“NOW THAT THE AUTO cycle trials are over for the year, and the judges have allotted their certificates, it may be well to review in some detail the behaviour of the machines as a whole. The question is often asked by persons who think of supplementing their ‘man-cycle’ (if the term may be used for want of a better) by a motor cycle, or of beginning in this form their cycling experience: ‘What will these motor’ bicycles really do? Are they not always breaking down, and is not the chief thing to be thought of in making the choice the ease with which this or that variety can be pedalled home when this happens?’ To this question the recent trials supply a clear answer. They undoubtedly justified their title by demonstrating reliability, and that, not in one or two exceptional instances, but almost all round. The steady running in face of every sort of adverse circumstance has been more than gratifying; it has been, as one of our contemporaries says, ‘astonishing’. Even experts scarcely realised the amount of progress which has of late been made by the builders. The motor cycle may now take rank with the car for trustworthiness.”— Automobile Club Journal.