1890

IN THE FACE OF the 2/4mph urban/rural speed limit Edward Butler gave up on his Petrol-cycle. He wrote in the magazine The English Mechanic: “The authorities do not countenance its use on the roads, and I have abandoned in consequence any further development of it.” It was a brave attempt that, had it not been scuppered by ridiculous legislation, would have put Britain at the forefront of the motor cycle (and automobile) revolution from the beginning.

KITCHEN GOODS specialist John Marston and Co expanded its output to include bicycles. As we’ll see in 1912, this was A Good Thing for motorcyclists.

HERBERT AKROYD Stuart patented a compression-ignition engine, a clea189r three years ahead of that nice Mr Diesel.

KARL BAYER developed the large-scale production of aluminium from bauxite.

IN JAPAN EISUKE Miyata set up a gun factory where he also made Asahi bicycles, closely based on the British Cleveland.

1891

EADIE MANUFACTURING renamed its Townsend bicycles Enfields to mark an arms deal with the Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield. The Enfield Manufacturing Co, soon renamed Royal Enfield, was set up to market them. In 1893 the firm adopted the slogan: ‘Built Like a Gun—Goes Like a Bullet’.

MAYBACH DEVELOPED a spray carburettor, though surface carbs would be more common for years to come.

1892

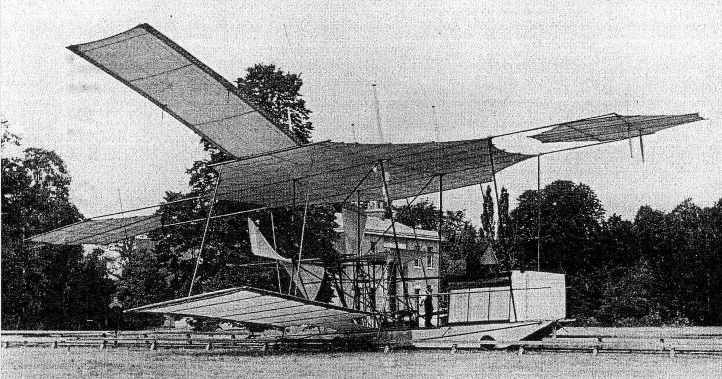

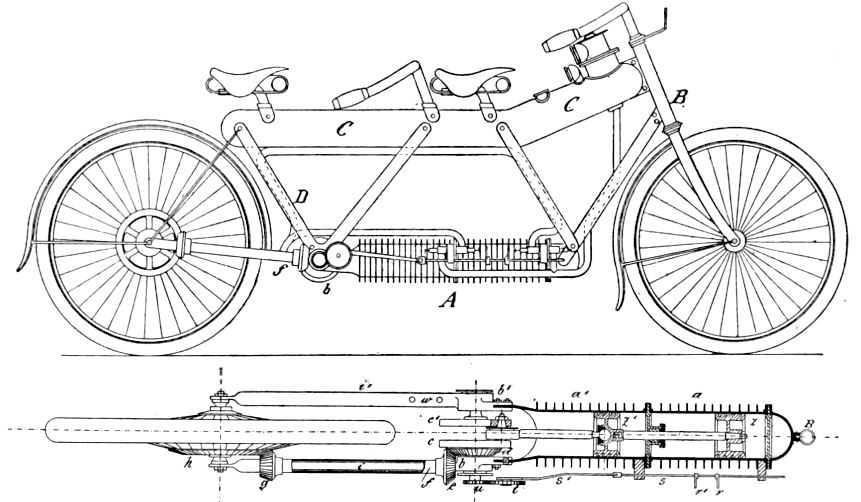

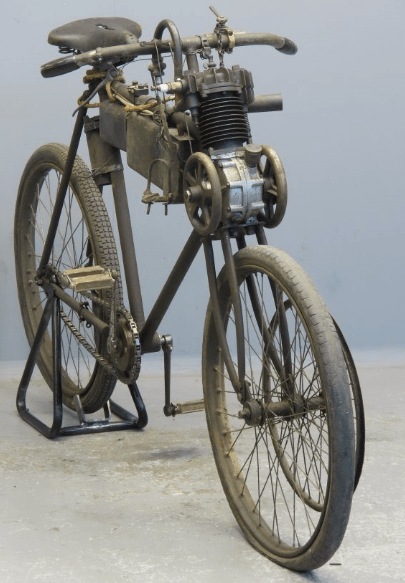

HANS GEISENHOF, who had worked with Karl Benz, designed a two-stroke petrol engine for the Hildebrand brothers. They fitted it into a bicycle frame but it was gutless so he and Alois Wolfmüller built a 1,489cc, water-cooled four-stroke parallel twin that developed 2½hp at 240rpm. The weight of this engine snapped the frame so the brothers used the frame from their 1889 steamer.

RUDOLPH DIESEL started development of a compression-ignition engine and was awarded a patent the following year.

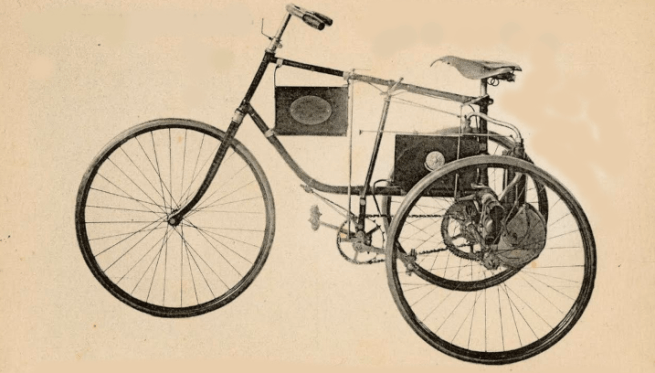

JD ROOTS DEVELOPED a water-cooled, two-stroke trike featuring shaft drive and exported its entire output to France to avoid Britain’s bonkers legislation.

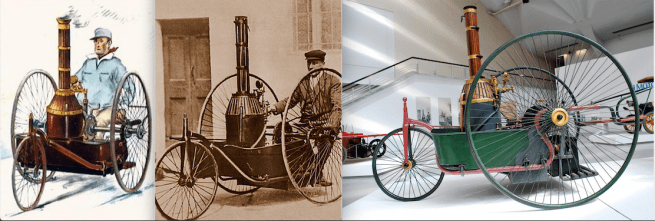

COMPTE ALBERTE de Dion, Georges Bouton and Charles Trepardoux had been making successful steamers for a decade when, following a visit to the Paris Exposition where they saw the Daimler engines, De Dion and Bouton decided internal combustion was the coming thing and began serious work on a petrol engine at the expense of their steamer projects. Trepardoux, a confirmed steam-head (‘vaporiste’, en Francais), walked out in disgust with the parting shot, “How can a motor function on a series of explosions?” His departure must have caused a row in the family, particularly when De Dion and Bouton were proved right.

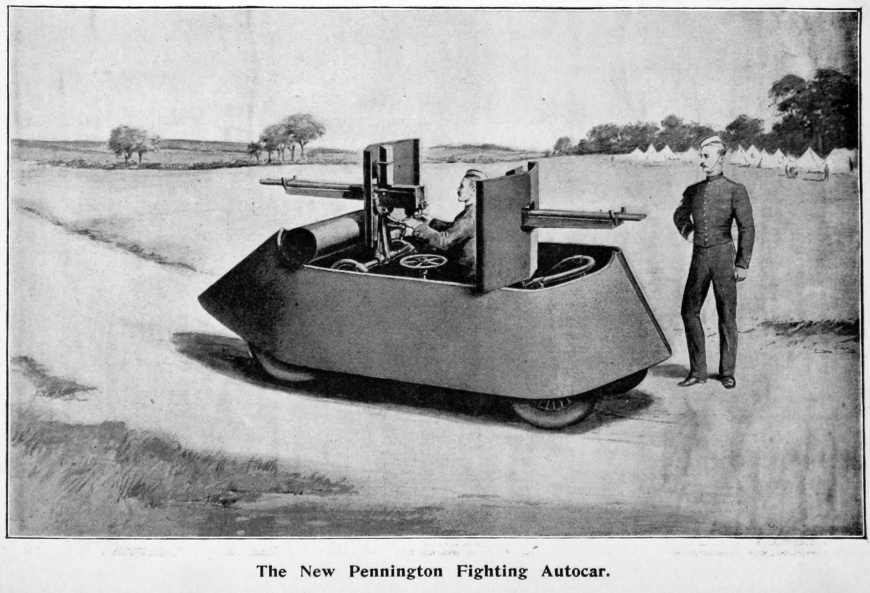

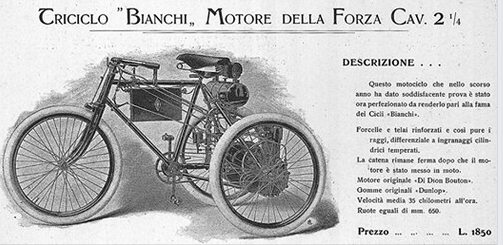

1893

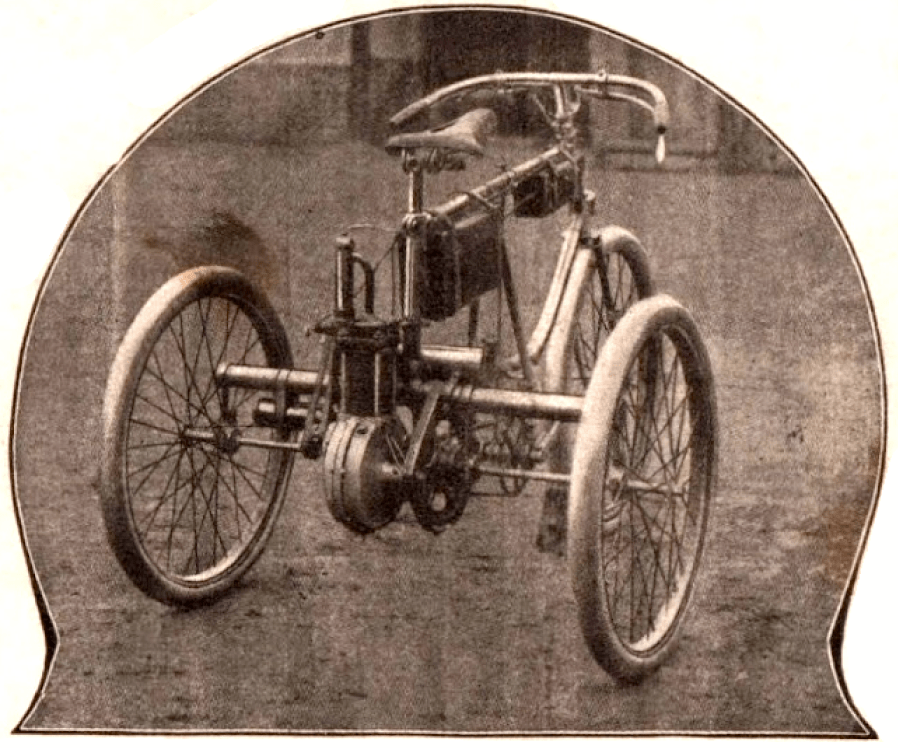

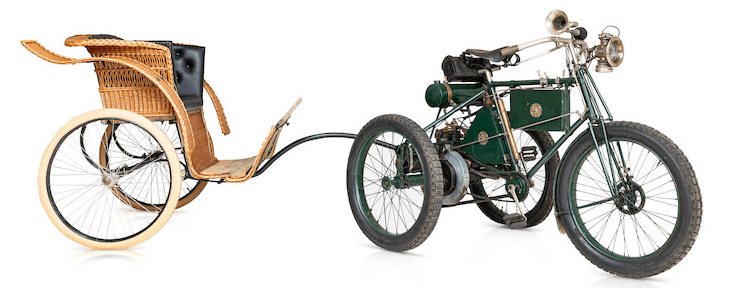

GEORGES BOUTON produced a 138cc single inspired by the Daimler engine in the 1885 Einspur but he found that it ran much smoother at higher revs. So while the Daimler engine ran at 250rpm and the Daimler at 750rpm, the De Dion Bouton ran at 1,500-2,000rpm and in trials reached 3,500rpm. Instead of hot-tube ignition the new ‘high-speed’ engine had a 4V battery/coil system with a contact breaker. Unlike many later engines it also boasted a detachable cylinder head; power output was about ½hp. De Dion and Bouton mounted their engine at the back of a pedal-powered Decauville trike which became a great success, running on the new tyres being mass produced by brothers Andre and Edouard Michelin. They also sold De Dion Bouton engines to power motor cycles, trikes and even an airship. This was the practicable proprietary engine that, combined with the many safety bicycles coming onto the market, launched an industry and, let it be said, an obsession.

ANGLO-GERMAN Frederick Simms, a pal of Daimler’s, bought the British rights to Daimler engines.

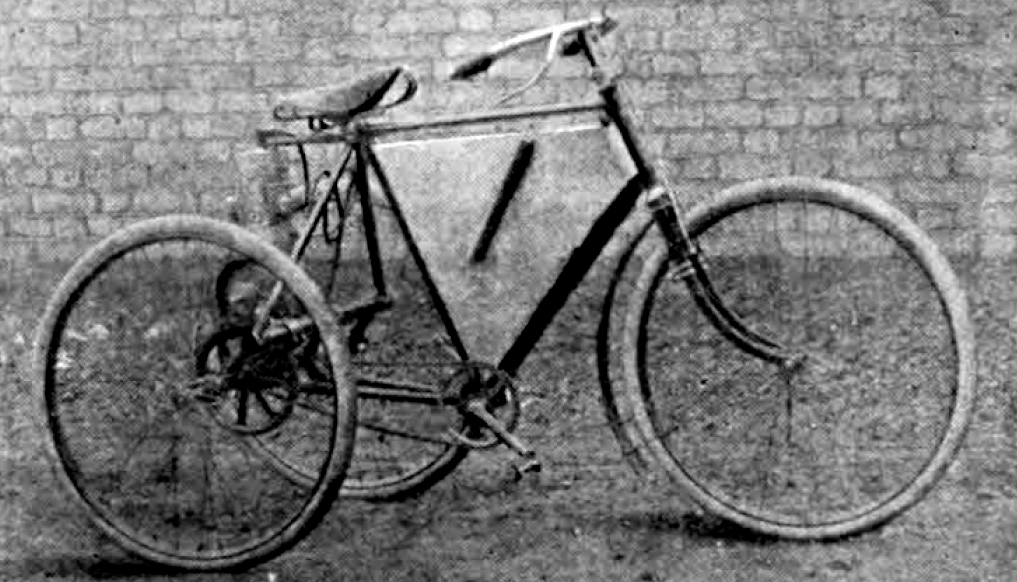

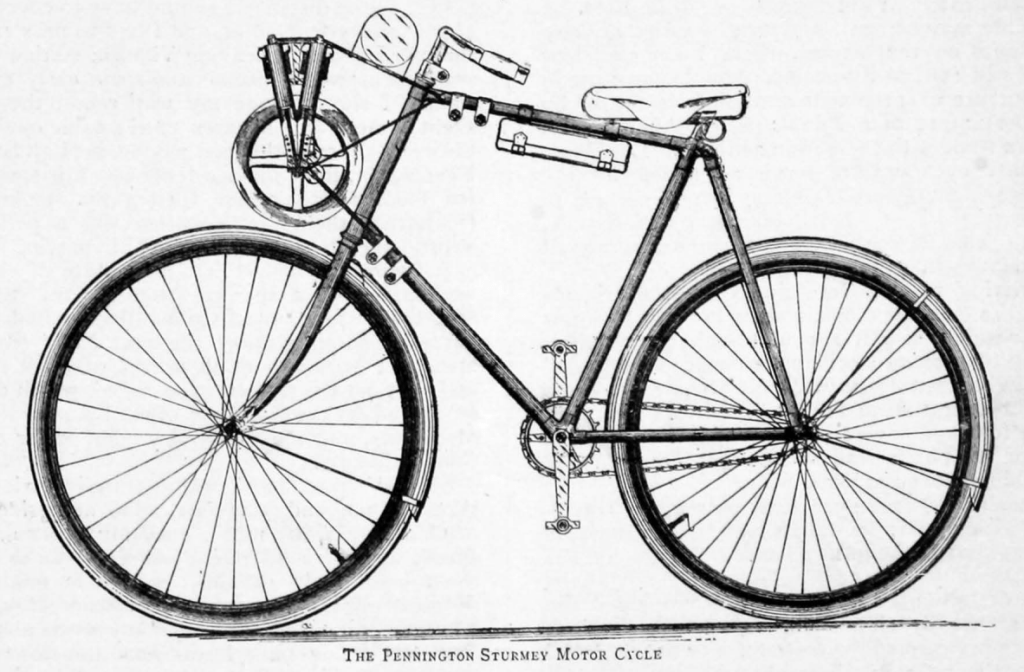

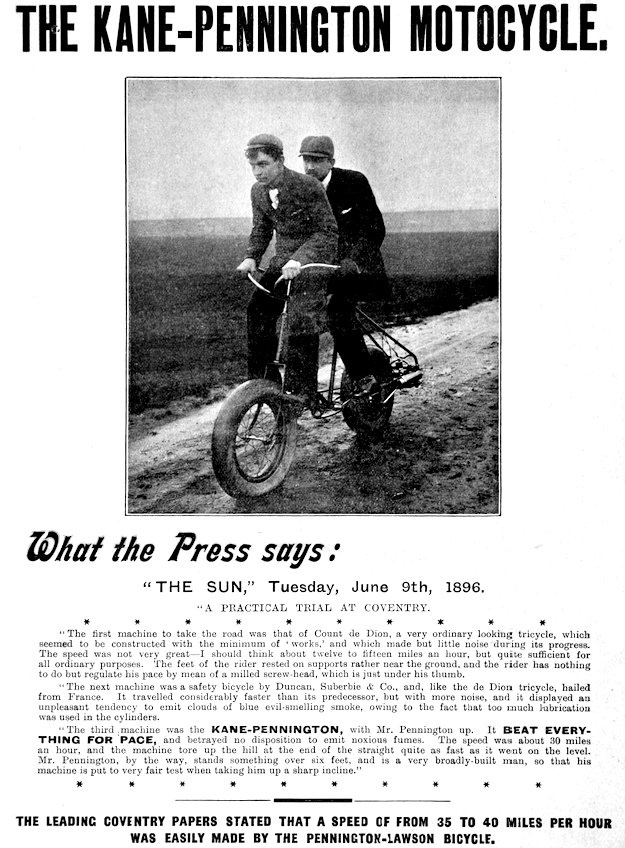

IN THE USA A bicycle was fitted with a rear-mounted horizontal twin two-stroke by one EJ Pennington—a second-rate designer but a first-class conman (‘premier division’ would be more accurate; he thought big. Take a look in the Galimaufrey for some of his scams).

A GERMAN CALLED von Mayenberg built a two-speed steamer with fuel for the burner carried inside the frame.

COTTON REINFORCING cords were moulded into bicycle tyres for tougher sidewalls.

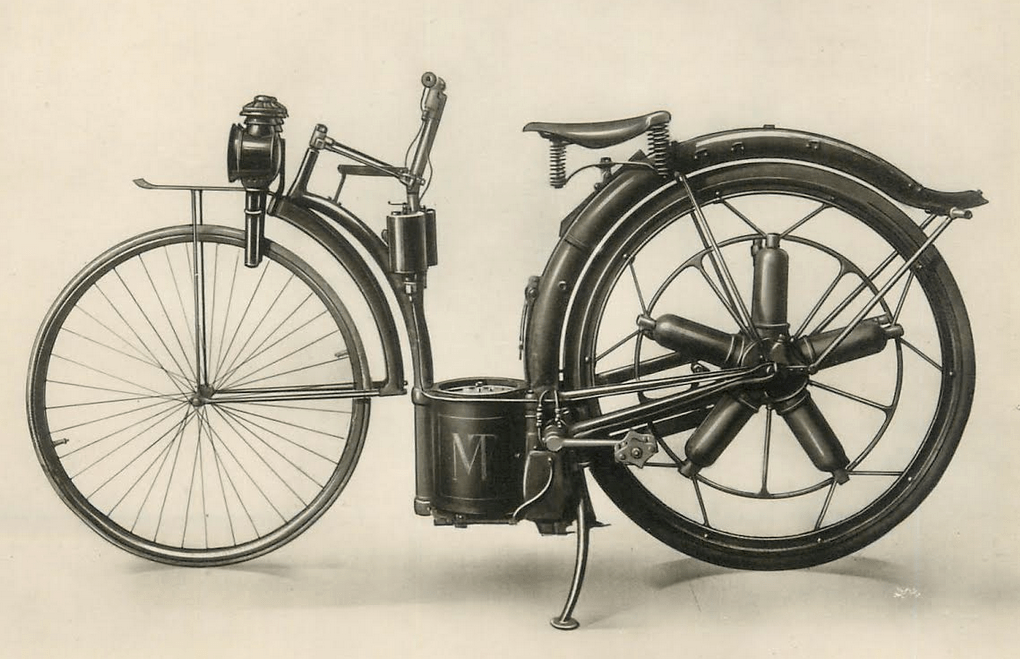

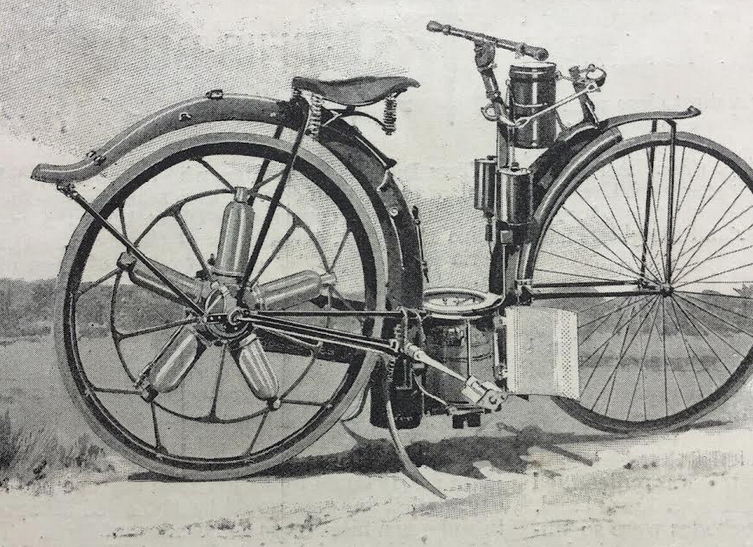

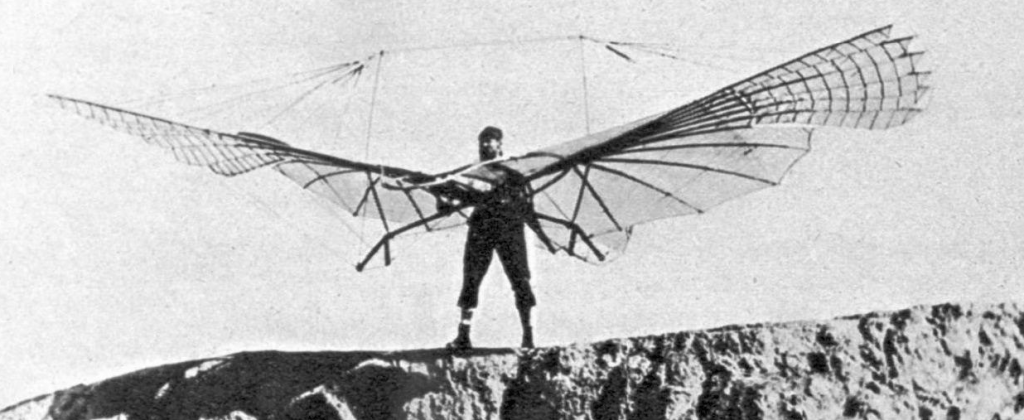

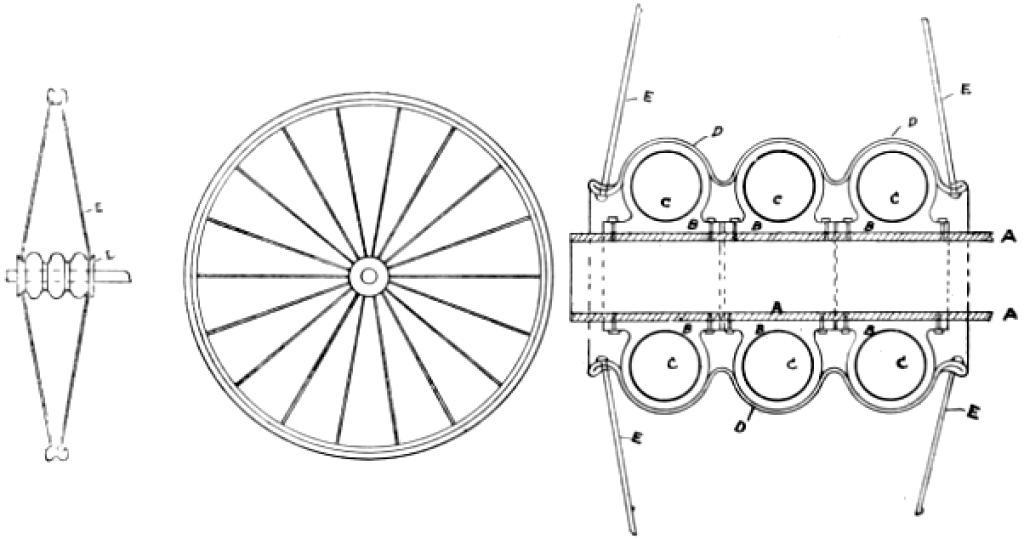

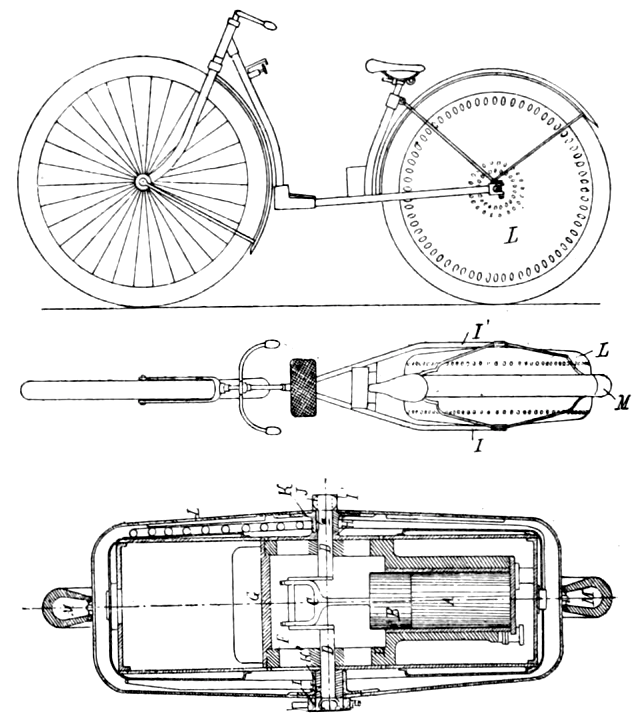

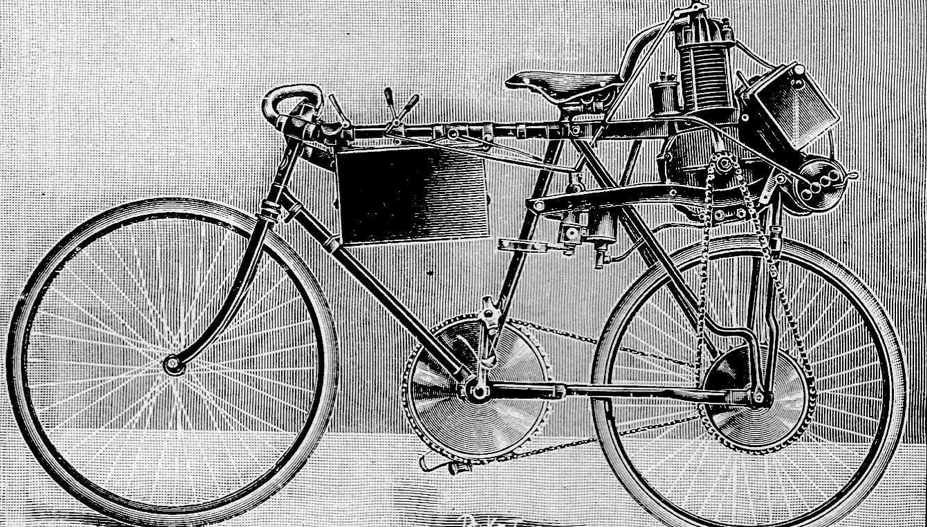

HAVING POWERED A TRIKE with his five-pot radial engine in 1887, Félix Millet built a motor cycle. This time the engine was in the rear wheel; the crankshaft served as the wheel spindle. Revolutionary features included a clutch (operated by back-pedalling, which also applied a brake), a semi-automatic frame lubrication system, mechanically operated valves, what was probably the first motorcycle centre stand (well, yes, it was a prop stand but it was in the middle) and an ‘elastic’ rear wheel which was an early attempt at suspension. The 1,924cc engine was rated at ¾hp at 180rpm giving a claimed top speed of 35mph. Fuel consumption was about 110mpg. Ignition was by a coil and lead-acid battery rather than the Hildebrand & Wolfmüller’s hot tube. Fuel was carried in the rear mudguard; a surface carb and air filter were fitted between the wheels. Millet sold the rights to Alexandre Darraq who planned to put the bike into series production; it was one of 17 starters (out of 102 two, three and four-wheeled entries) in in the Paris-Rouen Trials, generally accepted as the world’s first motoring contest. The Millet retired early in the race, production plans were dropped and Millet died in poverty.

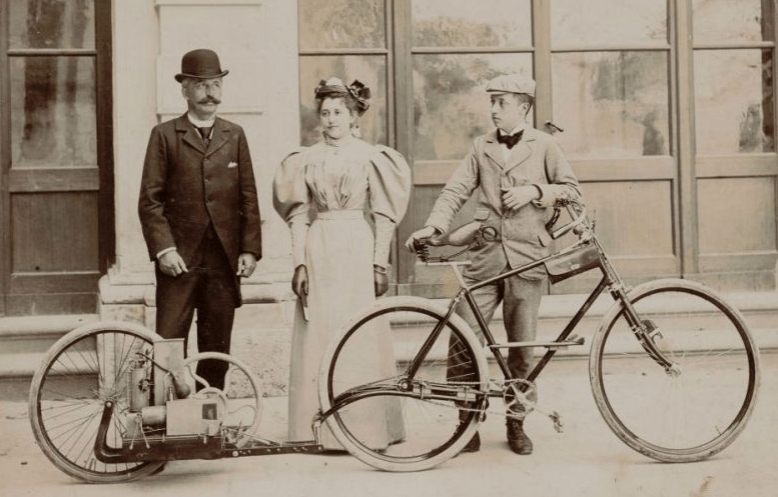

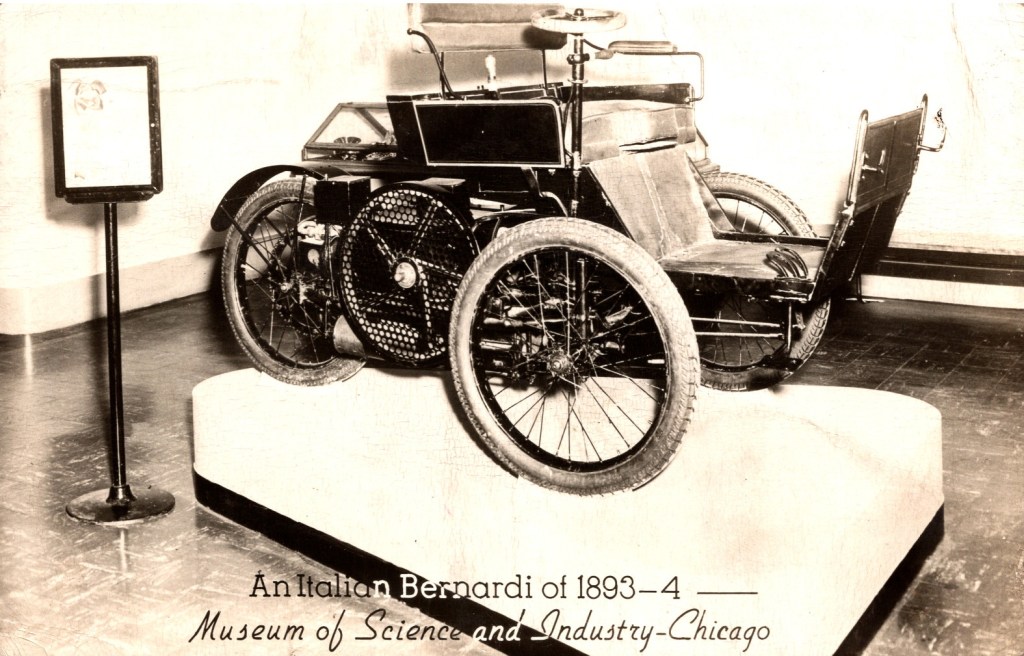

ENRICO BERNARDI, having registered the first patent for an Otto-cycle engine in 1882, also produced a petrol-powered two-wheeler, although in this case the engine was mounted in a trailer which pushed the bike.

1894

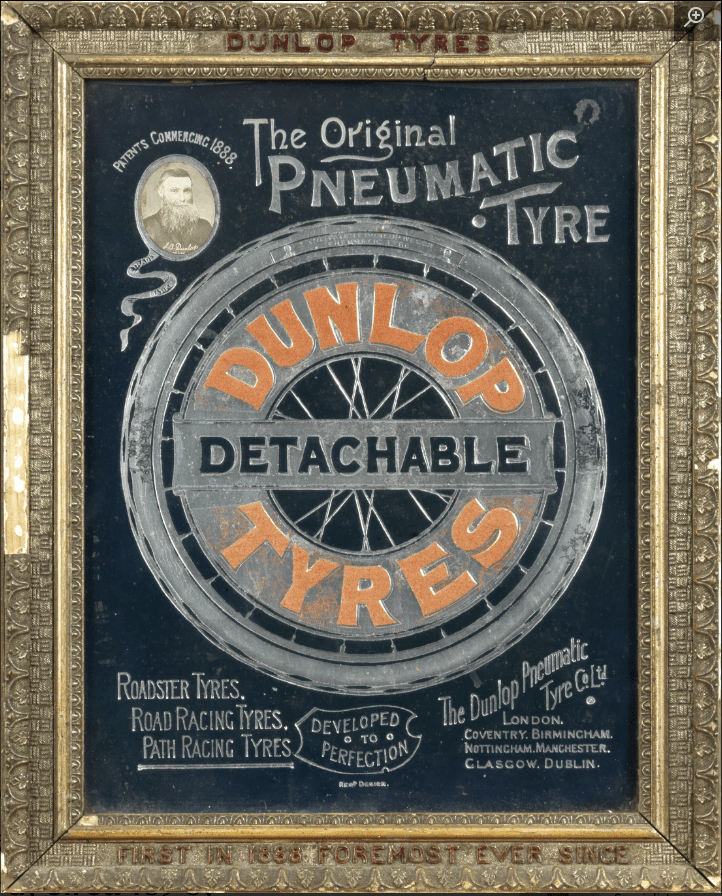

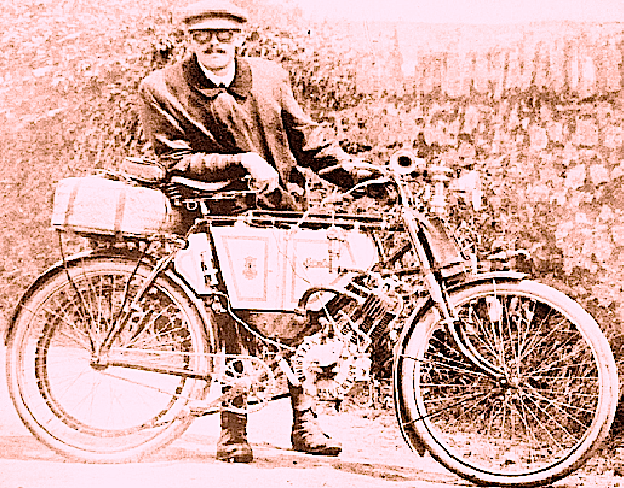

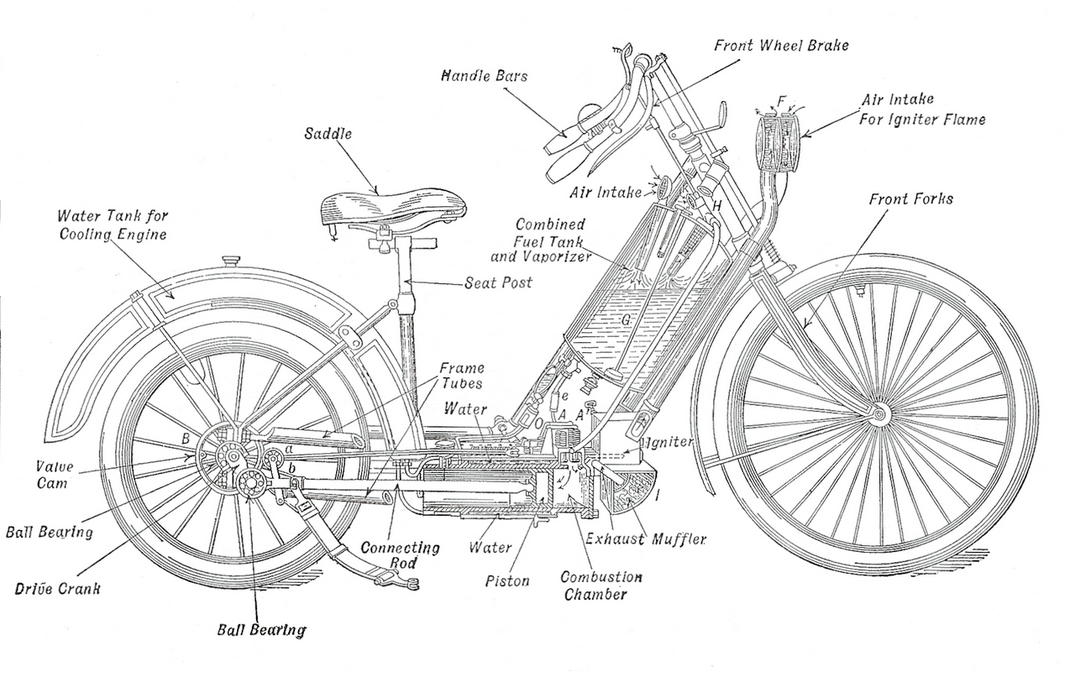

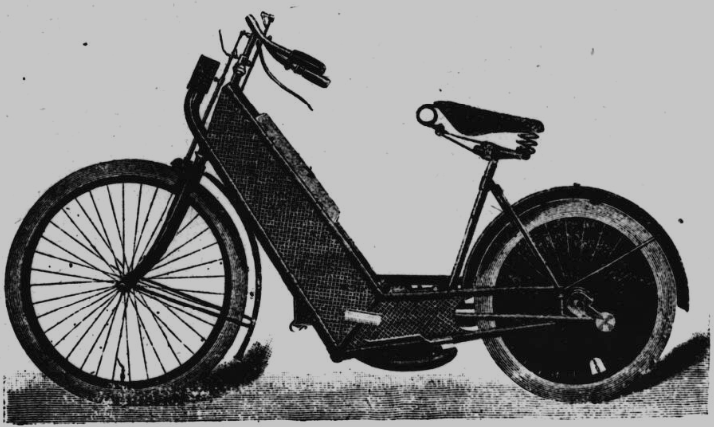

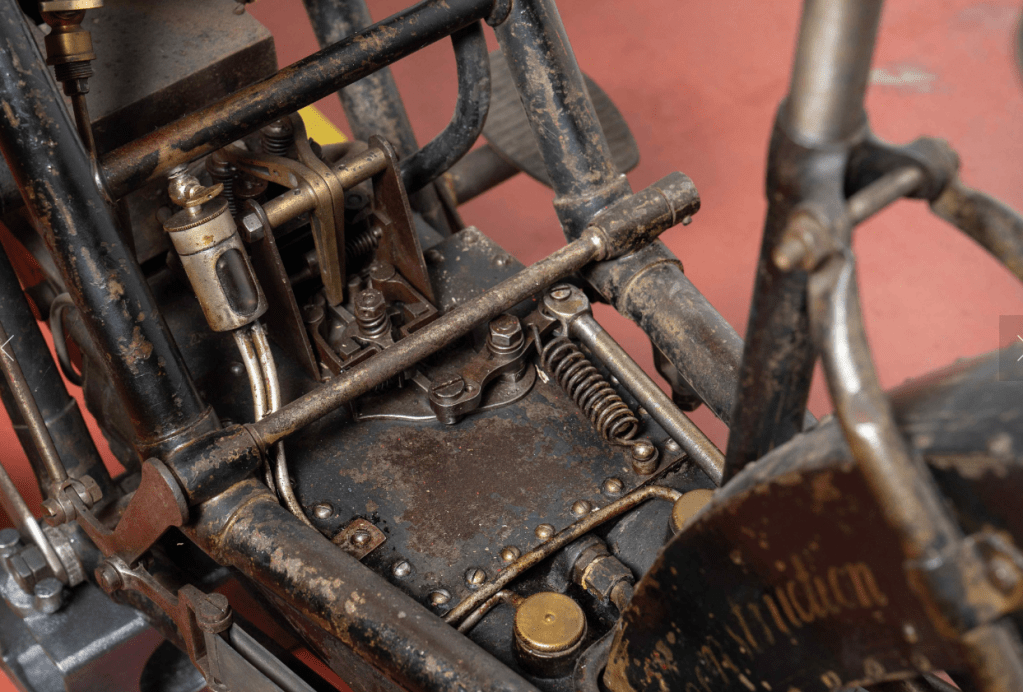

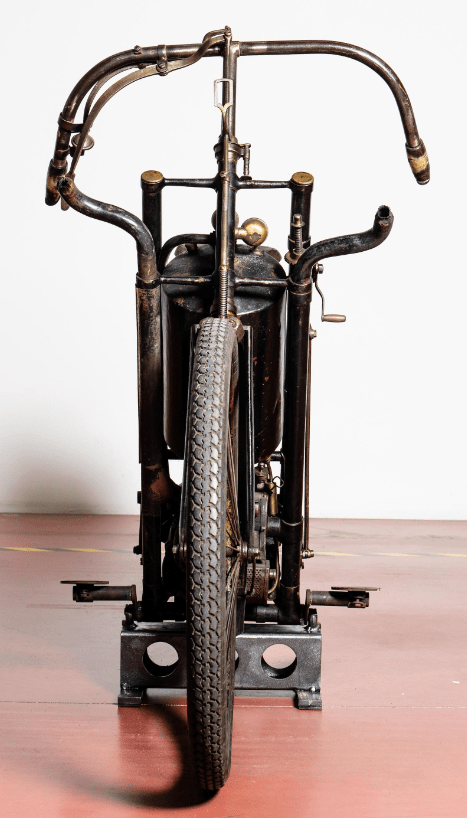

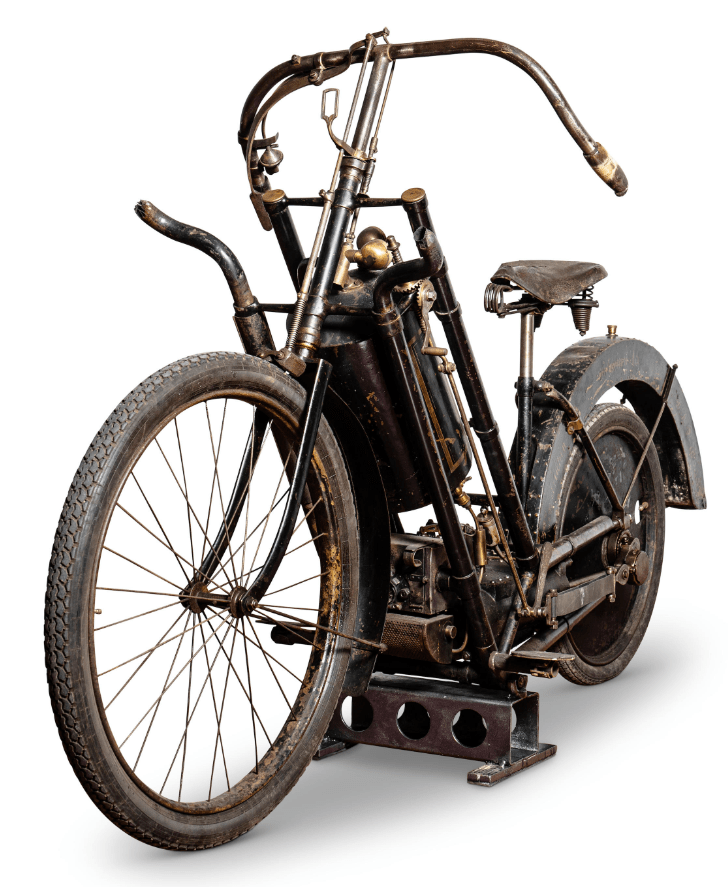

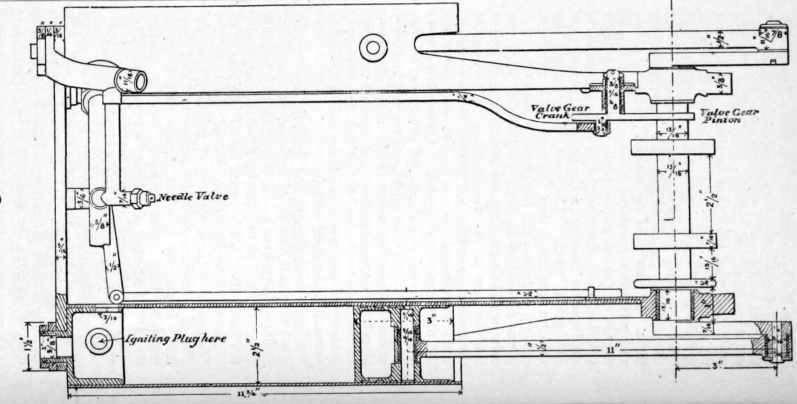

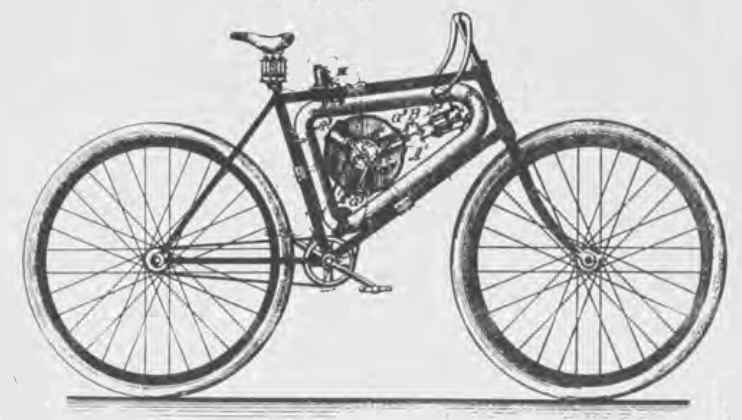

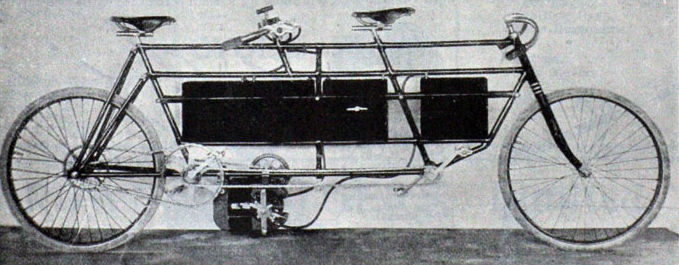

HEINRICH HILDEBRAND and Alois Wolfmüller patented the bike they’d been working on since 1892: a 1,428cc/2½hp water-cooled four-stroke twin (with hot-tube ignition and surface ‘bubbler’ carb) which would become the first motor cycle to sport pneumatic tyres, thanks to a deal with Dunlop. Following steam-locomotive practice the conrods drove the rear wheel so there was no crankcase and no belt, chain or shaft rear drive. Neither was there a flywheel; instead elastic straps helped the pistons back down the barrels. Claimed top speed was 25mph; brakes comprised a steel ‘spoon’ pressing against the front tyre and a pedal operated ‘sprag’ rear brake—a lump of metal that could be forced down against the road surface as an anchor of last resort. It was the world’s first motor cycle to go into series production, made in Munich by Motorfahrrad-Fabrik Hildebrand & Wolfmüller in a factory the brothers had purpose built for the project with 1,200 assembly workers; they also used many local engineering firms for components. ‘Motorfahrrad’ translates as ‘motorcycle’; an early use of the term. They even sent a demo model to Paris in a bid to win export business.

IN BETWEEN STORIES about “the latest design of unicycle” from Chicago (incorporating “a casing or cage for the rider…on which is loosely hung a frame carrying a seat for the rider) and advance notice of the Stanley Show “…as the space will be allotted strictly according to priority of application, delay will be dangerous for those who desire to share in the cream of the sites” Cycling magazine reported: The motor cycle, the invention of H Hildebrand, editor of Radfahr Humor, is now being actually made to supply orders and a factory is in course of construction, at Munich, to be devoted to the manufacture of the machine. A good pace can be obtained out of the machine, without any exertion on the part of the rider. Just what the motive power is we are not informed, further than that it is concealed in a reservoir, and can be obtained cheaply anywhere. We illustrate the machine, or engine.”

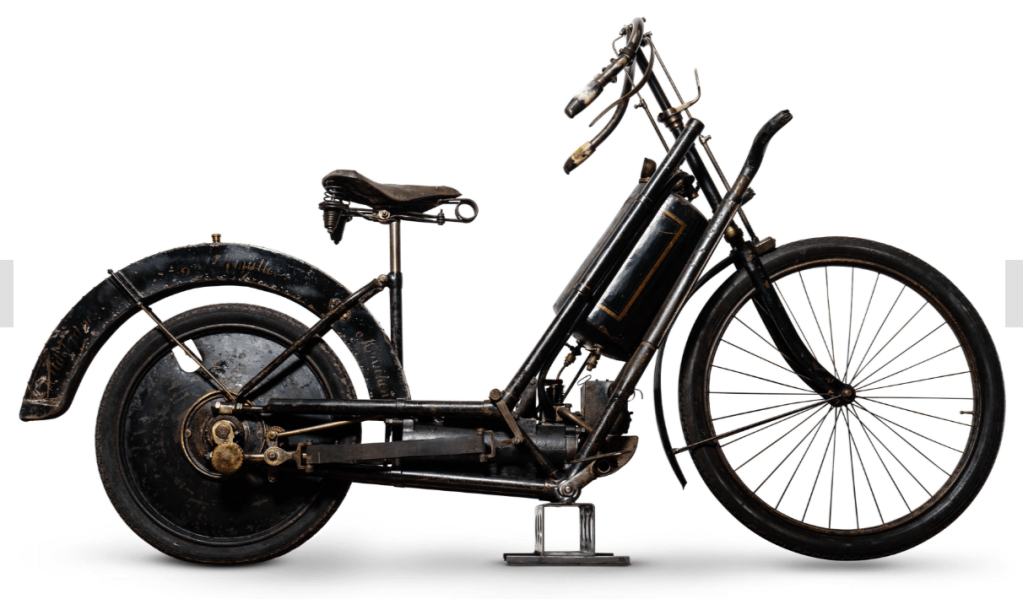

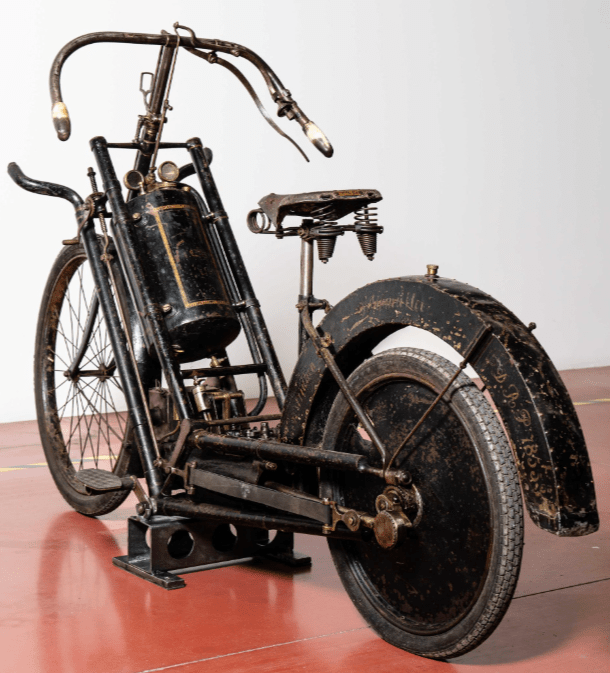

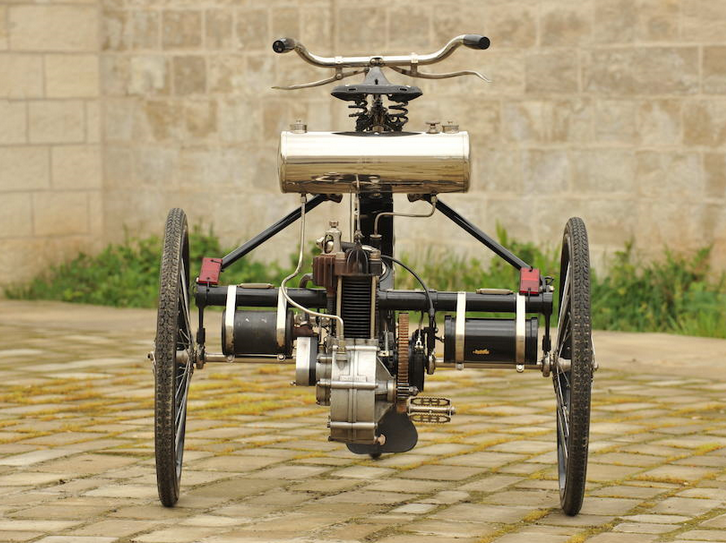

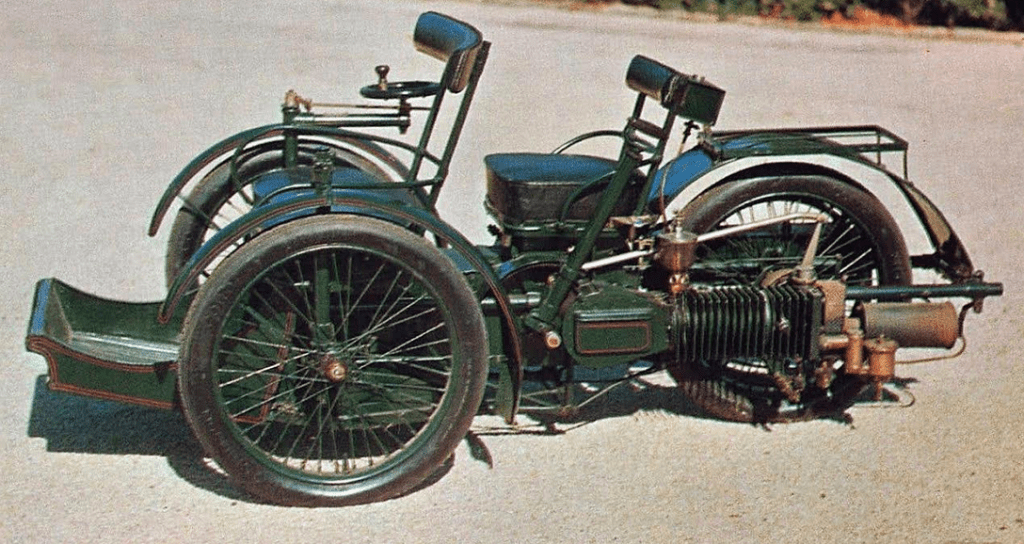

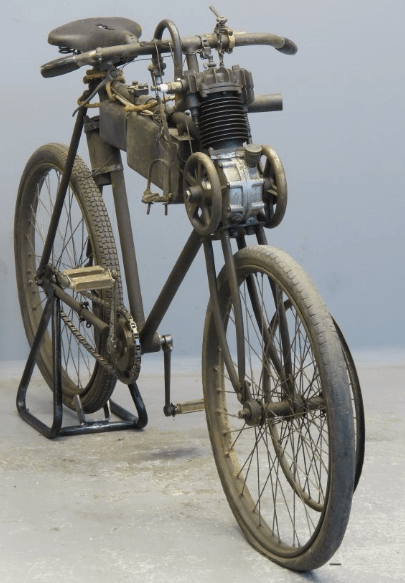

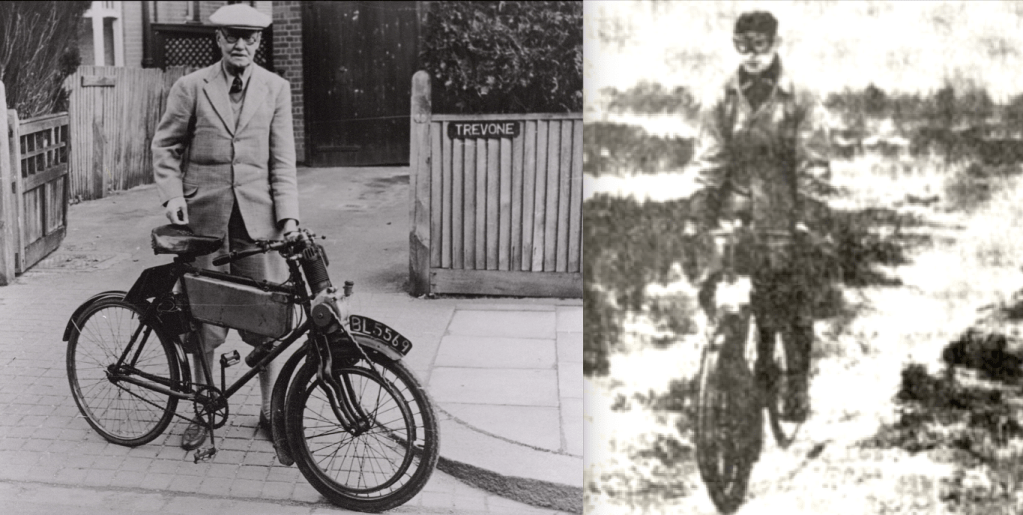

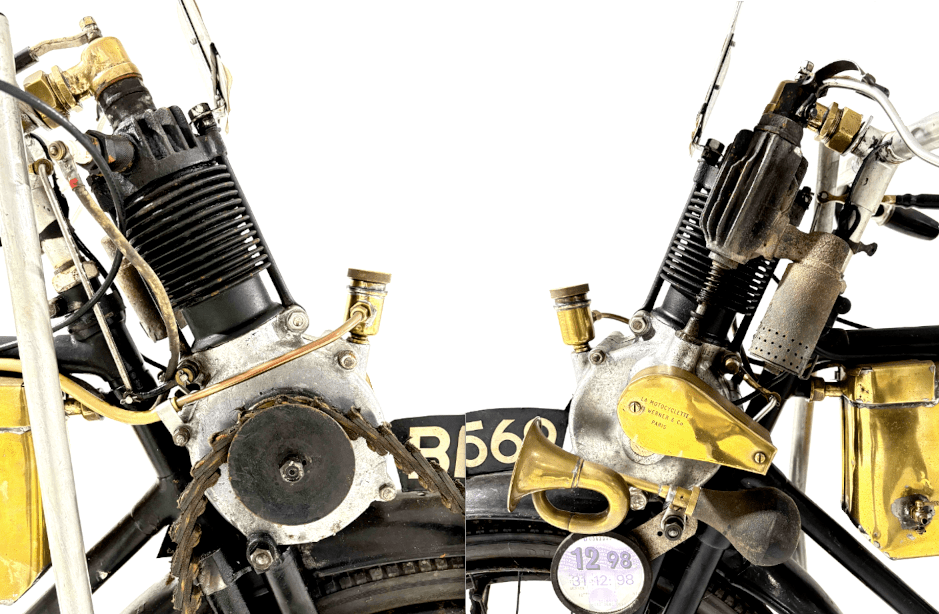

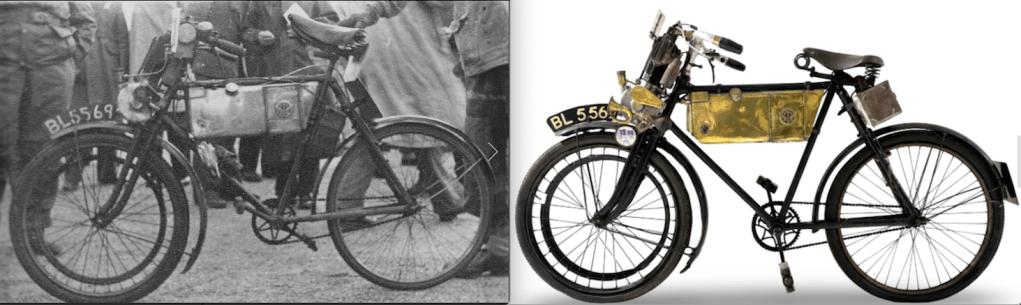

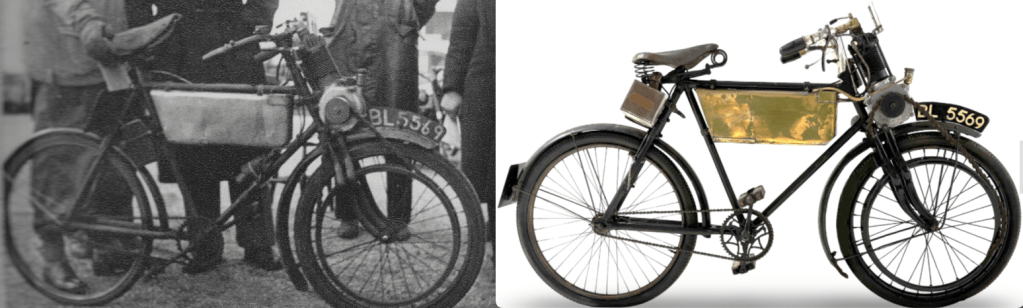

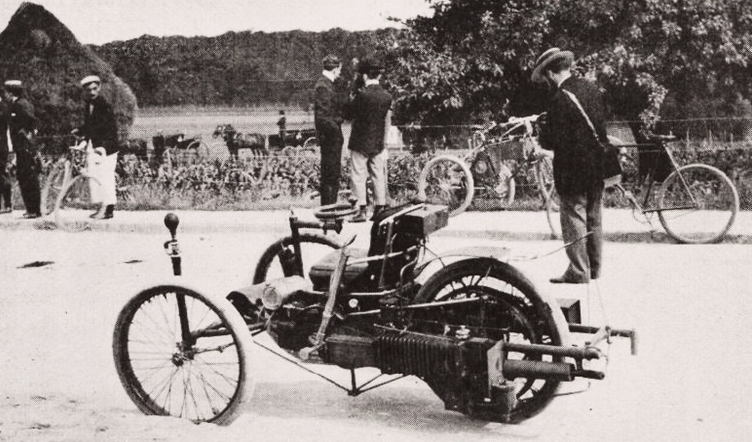

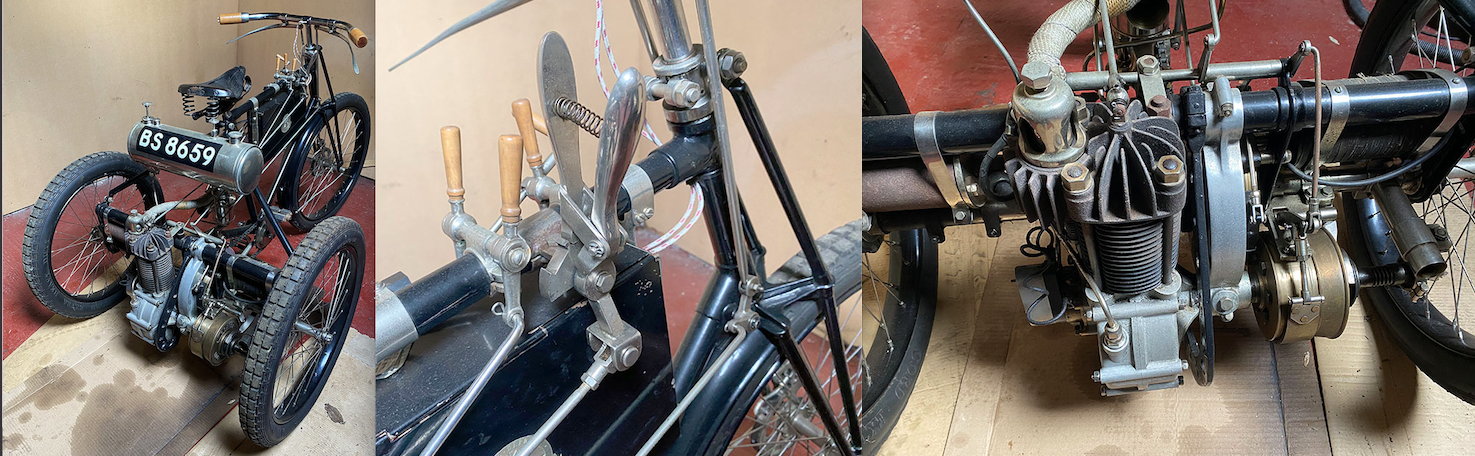

Stop press (spring 2025): A Hildebrand & Wolfmüller turned up in Italy and is due to go under the Bonhams hammer with an estimated price of £120-160,000. Here, for your delectation, are are some rather fine images of the 121-year-old, that looks pretty sprightly for its age…

PROFESSOR ENRICO Bernadi of Verona built a four-stroke, water-cooled ohv 265cc single-cylinder engine and named it the Lauro. It was too bulky to fit in a bicycle frame so Bernadi mounted it in a monowheel trailer. The engine turned the trailer wheel and the trailer pushed the bike. Control was via a rubber bulb which controlled a carburettor diaphragm.

I’M GRATEFUL TO my amigo Francois for recording the first known motor cycle race (read all about it in ‘Images of Yesteryear’ via the main menu). Italy was first past the post when two (sadly unidentified) bikes joined three cars in a 70-mile race from Turin to Asti and back. We don’t know who won, or indeed if anyone completed the course—but they tried. Viva l’italia! Within weeks the French had a go when two bikes started in the ambitious 732-mile Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race. The winning car finished in 48 hours; neither bike survived the course…you’ll find more details further down the page.

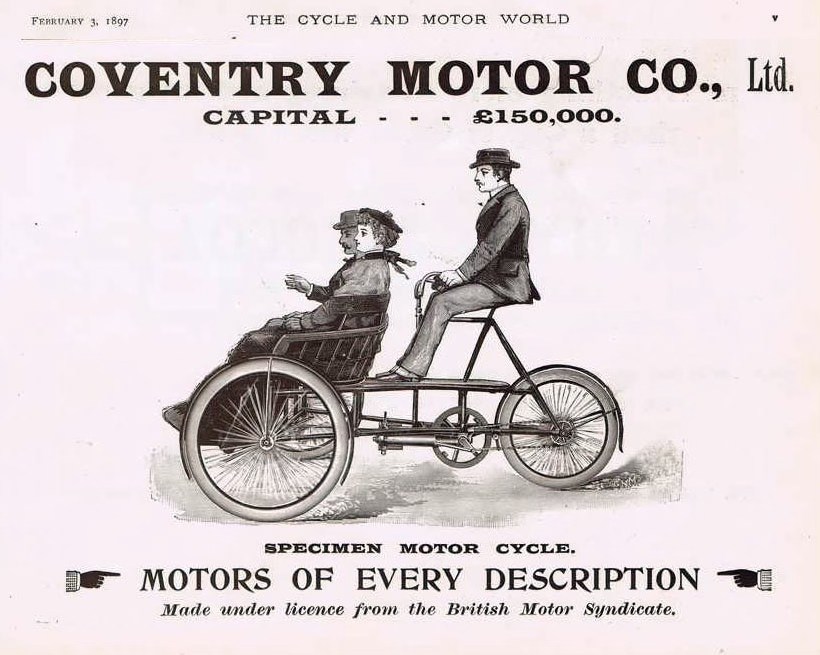

HARRY LAWSON’S Motor Manufacturing Company (MMC) company bought the British rights to De Dion engines.

1895

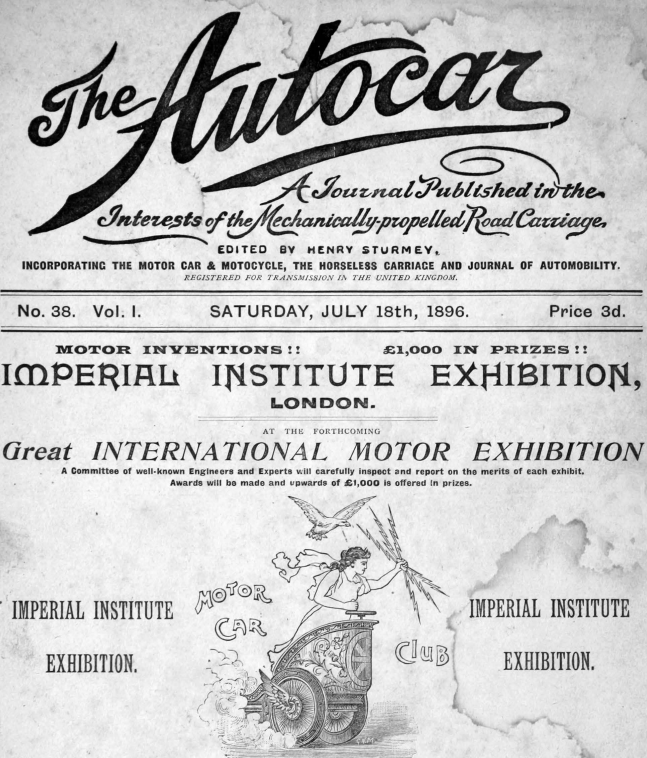

EIGHT YEARS BEFORE launching The Motor Cycle, Iliffe Press catered for the new breed of motorised transport with The Autocar. Here’s an excerpt from its first editorial: “Horseless carriage—automobile carriage—automatic carriage—autocar. All these names have been used to designate the latest production of the ingenuity of man, the motor-driven road carriage, irrespective of whether steam, electricity, hot air, or petroleum be the motive power. The last is the latest. The latest is the best, and, as ‘the best is good enough for us’—as our American cousins have it—its adoption to indicate the journal as well as the machine in whose interests it is published scarcely needs explanation. Nor is excuse needed for our entry into the world of periodic literature…The automatic carriage movement has come somewhat suddenly before the notice of the British public, although for over a year it has been making steady headway on the Continent, but now that it has reached our shores its practicality and far-reaching influence on the future life of the people force themselves irresistibly upon all thinking men. To those who have only now had their attention drawn to it, the idea, all new and fresh, falling suddenly on an unprepared mind, appeals with varying sensations, but to those who, like ourselves, have been pioneers in the early stages of automobility, and have seen and intimately followed the birth and growth to its present dimensions of the forerunner of the autocar—the bicycle—and have learnt to appreciate its advantages, there is nothing either strange or startling in the notion. It is the outcome and natural evolution of an idea to which the events of the past quarter century have led up, and which those whose thoughts have been cast in advance of the times have now for some time been looking forward to with pleasurable anticipation. The cyclist and the cycle maker have paved the way for the autocar…whilst the bicycle rider has accustomed the public mind to the sight of wheeled vehicles without horses, and convinced even the dense bucolic brain that such things have nothing uncanny in their composition, and can be as well controlled as the erstwhile equine steed, the manufacturer has brought the science of road-carriage construction to a point of perfection which enables the power developable by a motor to be utilised to the fullest and best advantage…To those who would revile the British engineer with having allowed both France and America to be before him, we point to the legislation of the past, which has throttled all enterprise at its birth, and now that way has been opened for the exercise of her powers we may say we have no fear that Great Britain will find herself in any way behind, as soon as the inventive talent of her mechanics has had time to develop itself.”

Unless stated otherwise, quotes for the rest of the year will be courtesy of The Autocar.—Ed

JOHN KNIGHT WAS prosecuted for “permitting a locomotive to be at work without a licence” in Castle Street, Farnham, Surrey—under local bylaws “no locomotive other than those employed for the repairing of roads, or for the purposes of agriculture should be used on the roads of the county without a licence”…another bylaw said locomotives could only be used within permitted hours. Knight contended that his machine was “not a locomotive within the meaning of the Act and thought he was “perfectly at liberty to use it”. He told the court that he had brought the carriage for the Bench to see and trusted they would not prosecute him for going home on it, adding that it was the “first machine of the kind to be made in England, though there were some 700 in France and on the Continent generally”. He was doing 4mph when stopped. The court imposed a fine of 2s 6d (12½p) on each of the two passengers. The Daily Telegraph reported: “The motor carriage in question, which was standing in the roadway outside the court, was the object of eager scrutiny. The task of getting up steam occupied about ten minutes after the case had been decided, and the tricycle, in charge of two men, moved off at a gentle pace in the direction of Mr Knight’s residence at Barfield, some two miles distant. The machine itself is remarkably compact, weighing only five and a half cwt, and there is nothing out of the common either in its shape or its appearance. In fact, it is nothing more or less than an enlarged and more elegant edition of the tricycle carts which are to be generally seen in the streets nowadays. As the tricycle moves along on its indiarubber tyres a little noise is given off from the motor, but nothing worth speaking of, and certainly insufficient to frighten horses. The vehicle seats two persons side by side, the levers, which are in front, being in close proximity to the driver’s seat, on the right hand. The machinery, which is at the back of the tricycle, is entirely, out of sight, and is stowed in a small compass. Driven entirely by the aid of benzine, the vehicle can cover eight miles an hour on good road, but, in view of the decision of the magistrates, no attempt was made to put the machine through its paces as it wended its homeward way.” The Autocar reported: “The carriage weighs in running order about 1,075lb. The gasoline engine is on the Otto principle, and has a piston 3¼in diameter and 4½in stroke [609cc] developing rather over three-quarter brake horse-power at 500 revolutions. The driving wheels, or rather the hind wheels—for one wheel only is a driver—are 3ft diameter, and the steering wheel 2ft 6in, all have 1½in solid rubber tyres. Two speeds are arranged for, corresponding to about three and a half and seven and a half miles per hour. No arrangement for reversing is used or thought necessary. The cooling water for the engine cylinder is contained in a tank under the seat, and a current of air is drawn by the exhaust over the water, and cools it to a considerable extent. We are informed that the motor cycle is almost silent in running, and that horses take no notice of it. With one person on, it will run seven and a half miles per hour on fairly level roads, and has run at from eight to nine miles per hour for short distances. With two passengers the speed is somewhat less. it was intended to be simply an experimental vehicle, chiefly to bring to public notice the restrictions which have hitherto prevented the use of motor carriages in England.In 1870 some excellent runs were made, and all difficulties were well overcome. The carriage, however, was very expensive to work, through repairs, and as some of the machinery was not very accessible, a good deal of time was taken up in adjusting brasses, etc. It was eventually sold to Mr James Braby, who converted it into a small traction engine, and fitted it with some peculiar wheels he had invented.” Knight’s four sons all drove it until 1903 when the minimum driving age of 17 was introduced—with Knight Snr’s encouragement the lads got stuck in and built themselves a wooden-framed trike.

“MR. KNIGHT’S PETROLEUM AUTOCAR—Please correct error in account of my motor cycle. The weight is not 1,0751b, but five and a quarter hundredweight [588lb] in running order. This, of course, includes three gallons of cooling water. In future machines of this size and type, the weight could be reduced considerably, but it must be remembered that in this first experimental machine facility for alteration and modification was of primary importance. May I add that the little carriage will take its load of two passengers up an incline of one in twenty, and one passenger up a fairly long hill of one in sixteen, and with a little care in driving up a much steeper incline. It can be turned round in a space of 12ft 6in.

John Henry Knight.”

“THE USE OF LOCOMOTIVES on public roads appears to be chiefly regulated by the Locomotives Act, 365. Section three of this Act provides that every locomotive propelled by steam or any other than animal power on any turnpike road or public highway shall be worked according to certain rules and regulations specified in the Act, amongst others that at least three persons shall be employed to drive or conduct such locomotive, that every such locomotive shall be instantly stopped on any person with a horse, or carriage drawn by a horse, signalling for the locomotive to be stopped; that those in charge of any such locomotive shall have two lights fixed conspicuously, one on each side on the front of the same, between the hours of one hour after sunset and one hour before sunrise; and section seven provides that the name and residence of the owner of every locomotive must be affixed thereto in a conspicuous manner. The Highways and Locomotives Amendment Act, 1878, orders that each locomotive must be preceded by some person by at least twenty yards, who shall, in case of need, assist horses in passing the same; and the same Act empowers county authorities to grant licences for the use of locomotives in their county. None of these regulations appear to have been repealed or in any way affected by later Acts, so they apparently regulate the use of all machines which are driven by other than animal power. The case Parkyns vs Priest supports this view, for in it a bicycle which was capable of being propelled by the feet of the rider, or by steam as an auxiliary, or by steam alone, which caused no smoke or gave any indication that it was worked by steam, and could not frighten horses or otherwise cause danger to the public more than an ordinary bicycle, was held to be a locomotive within the definition of sec 38 of the Highways and Locomotives Act, 1878, which defines a locomotive as ‘a locomotive propelled by steam or other than animal power’. It is exemption from laws such as this which is wanted in a new Act. It must be self-evident that such vehicles as the modern autocar were never contemplated when they were framed, and it is simply monstrous that the growth of trade and the development of a new industry of incalculable importance to the future prosperity of the country should be hindered and prevented by adhesion to the letter of laws intended to regulate traffic of quite a different character, and we confidently look forward to such a consummation in the immediate future.”

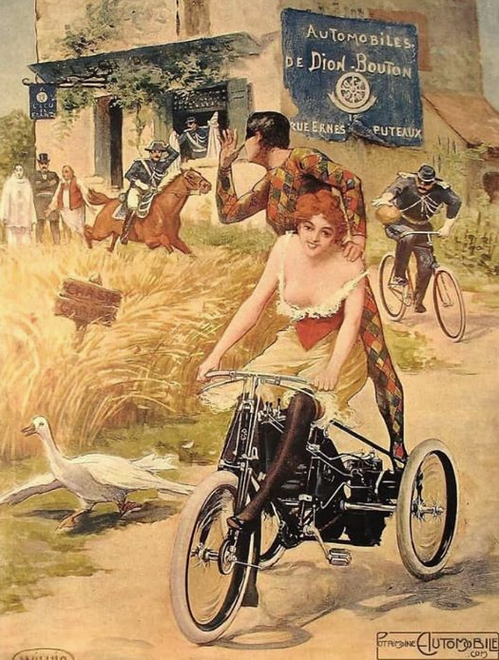

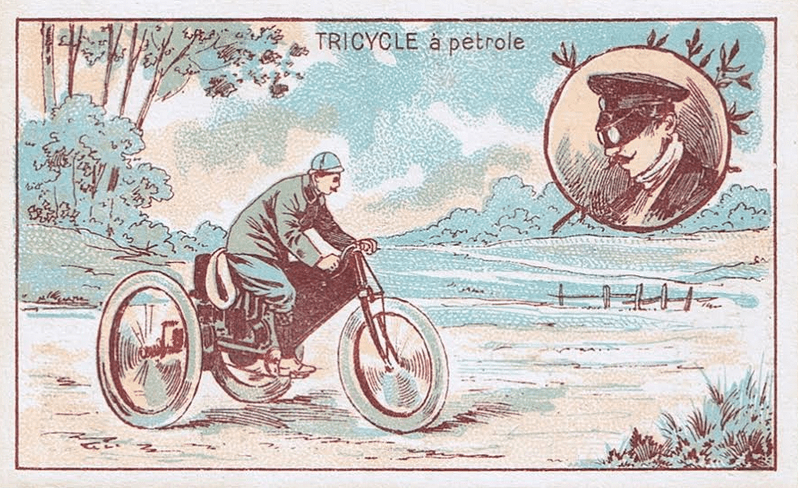

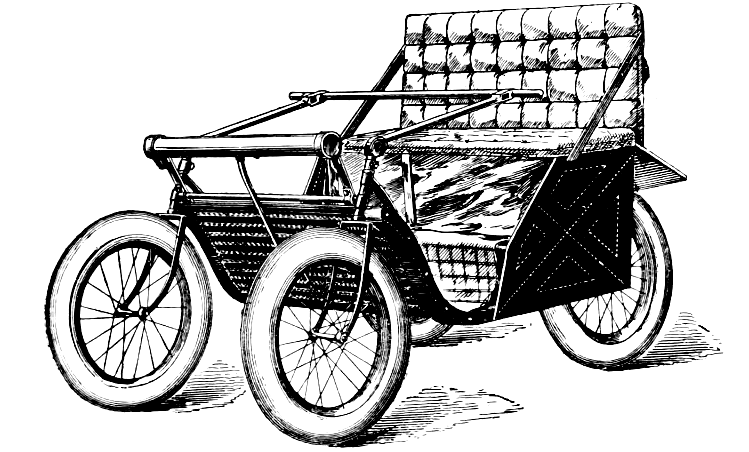

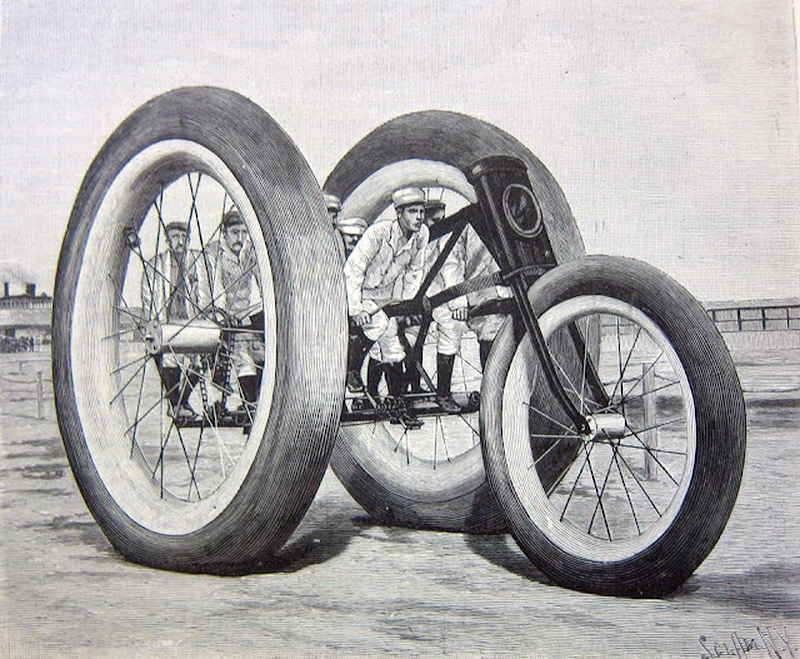

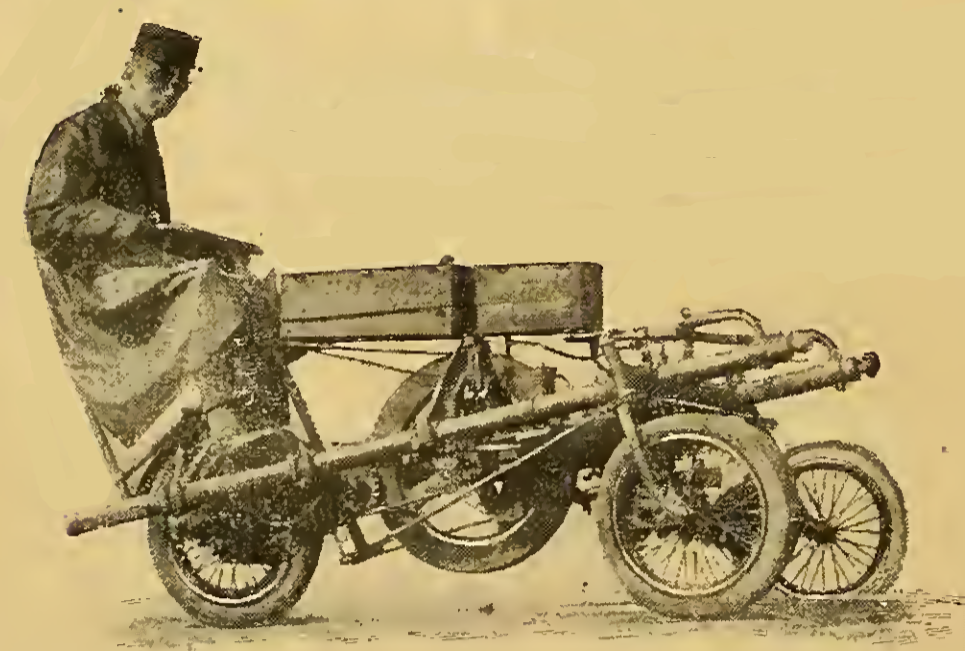

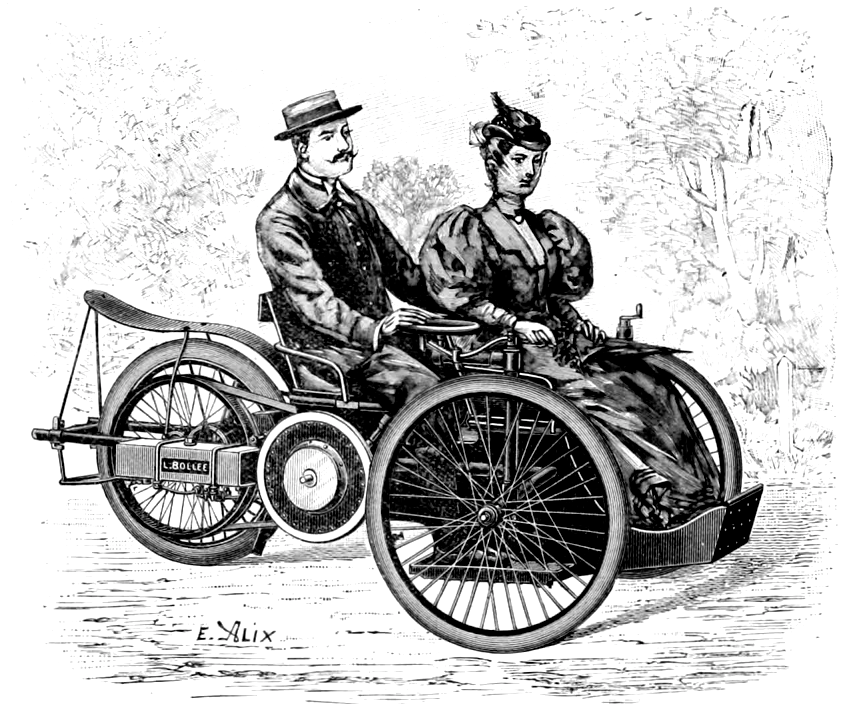

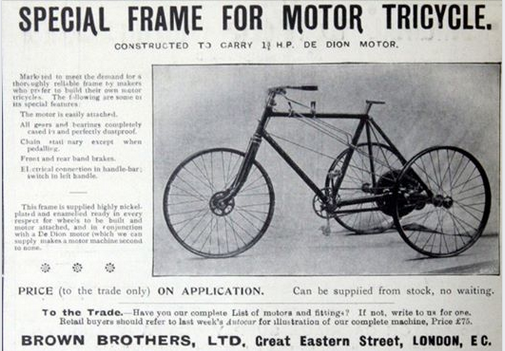

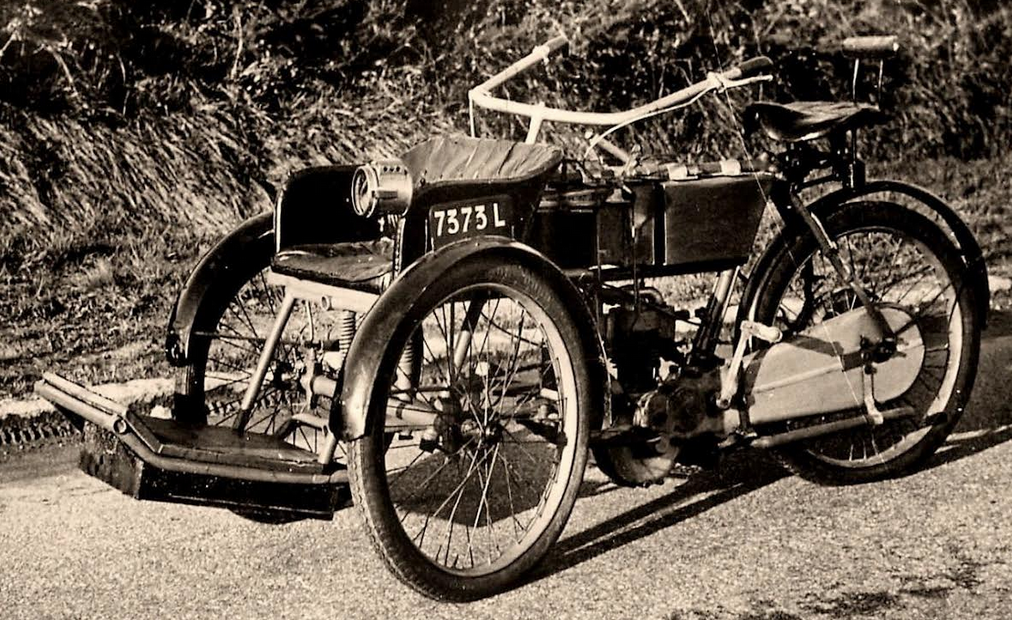

THE DE DION-BOUTON engine, enlarged to 185cc (1¼hp) and then to 211cc (1½hp), but still weighing less than 40lb including the battery and petrol tank, was mounted at the back of a Decauville pedal trike which was shod with the new tyres being mass produced by brothers Andre and Edouard Michelin. De Dion-Bouton were soon selling their own trikes and engines as fast as they could make them. The tricycle (with a 920mm track) was chosen because, according to the good count, “a bike appeared too fragile for this purpose”. It would be the most successful motor vehicle in Europe until 1901, with about 15,000 examples sold,

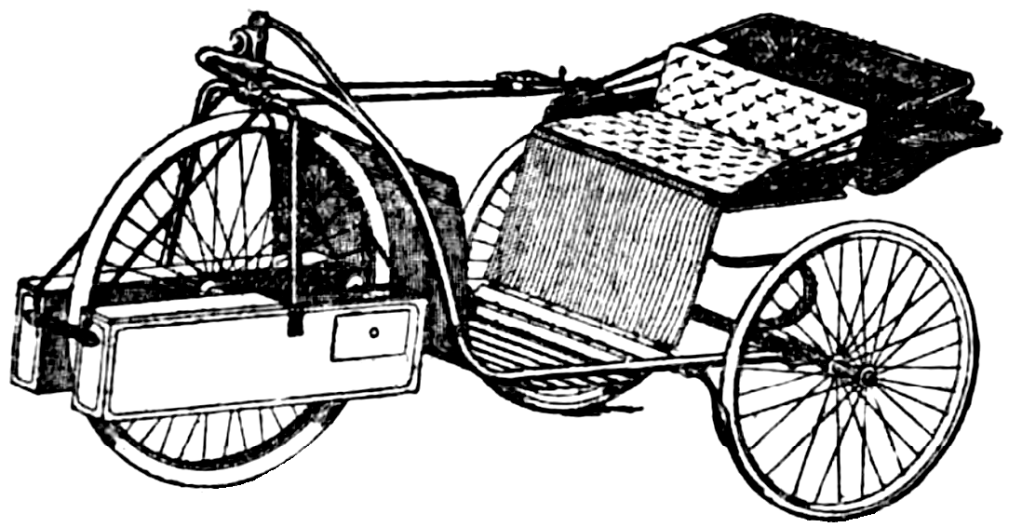

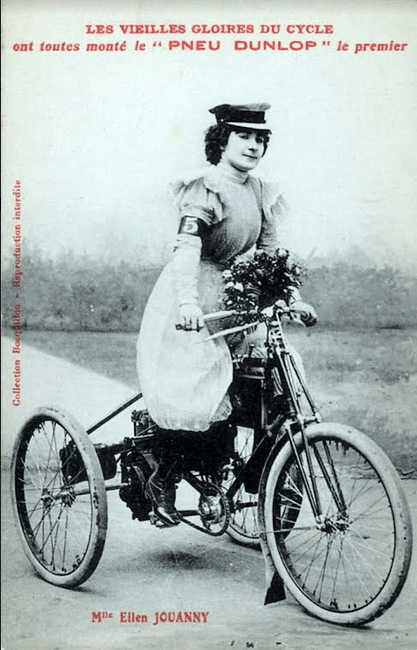

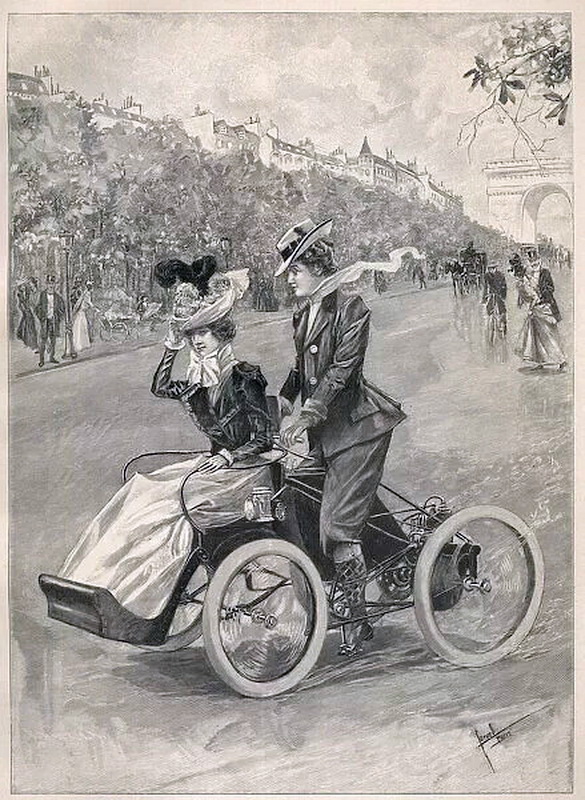

IT ALL LOOKS TRES JOLI but judging by the caption on this card, trikes were not universally popular in La Belle France…

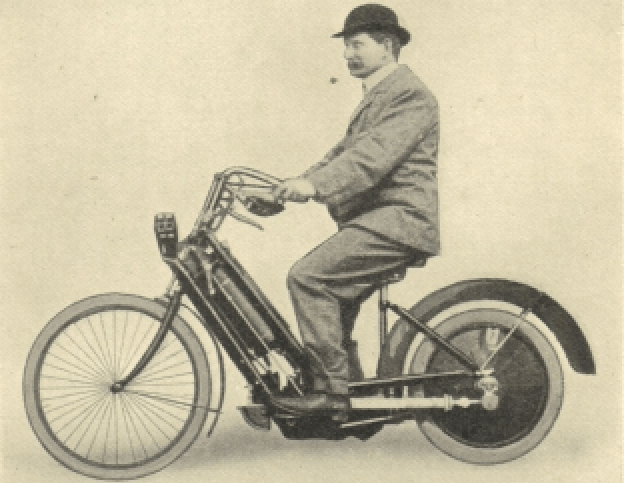

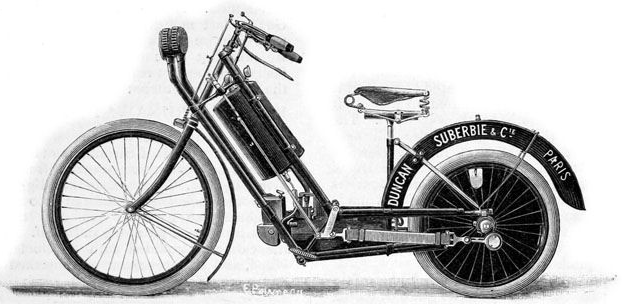

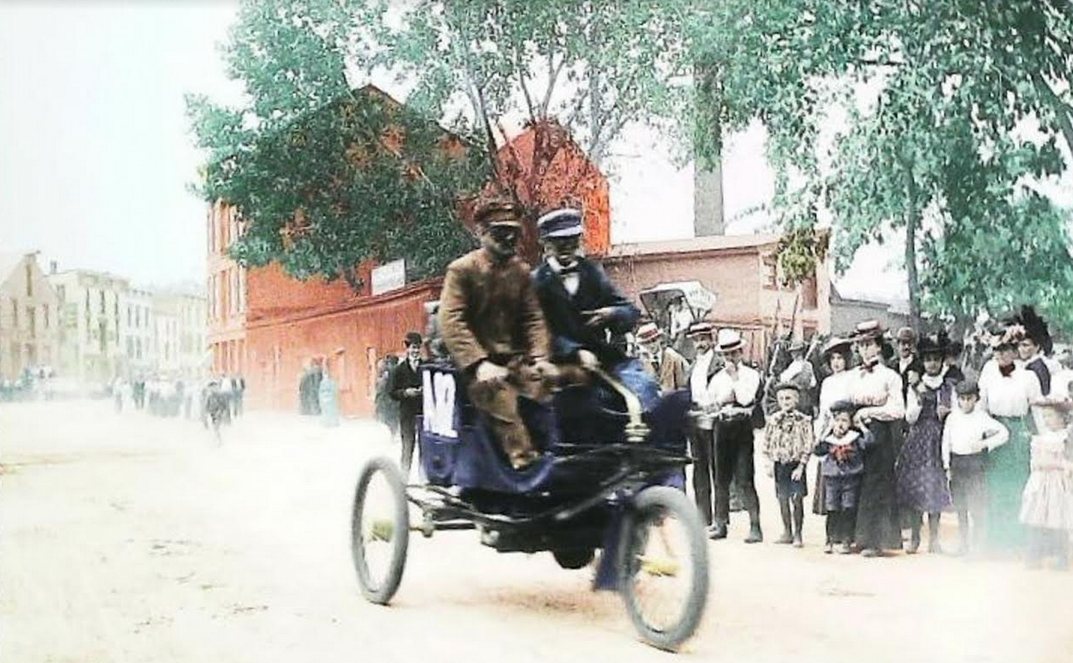

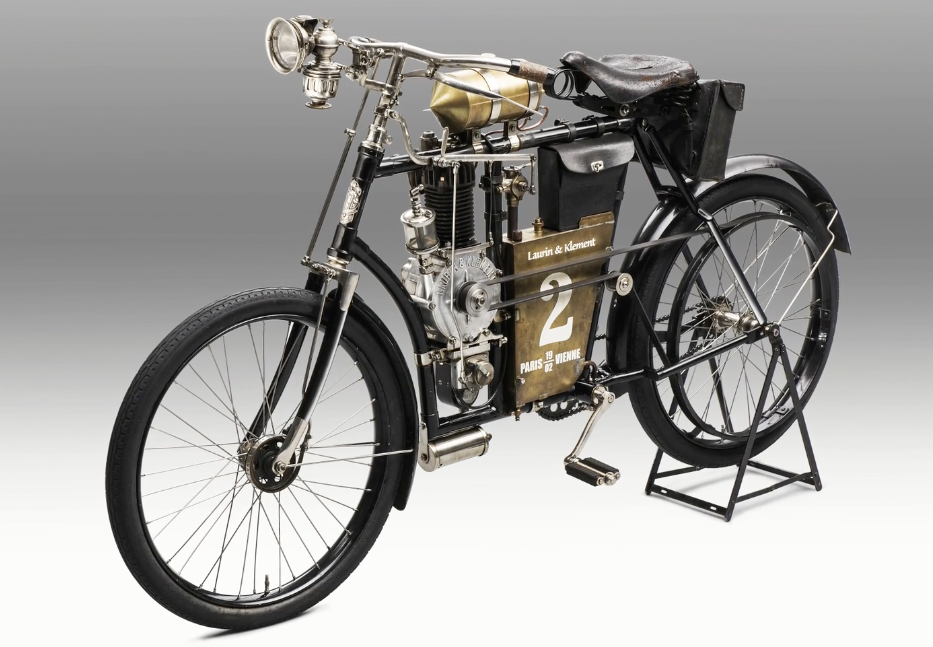

SIEGFRIED BETTMAN’S partner in Triumph, Mauritz Schulte, considered producing H&Ws under licence. He imported one for testing but the idea went no further. However the French manufacturer Duncan-Superbie & Co produced bikes developed from H&Ws which they marketed as Petrolettes (presumably to mollify painful French memories of the 1870-1 Franco-Prussian war). Wolfmüller took a brace of H&Ws to Italy for its first bike/car race; they came 2nd and 3rd over a rocky 62-mile course behind a Daimler car. Two Petrolettes were among the six bikes that entered the 732-mile Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race. None of them completed the course but a Petrolette, ridden by Georges Osmont, was the only two-wheeler to complete the first leg from Paris to Bordeaux, in 45 hours. The first car home was a Panhard et Lavossar (driven by Emile Levassor), in 48hr 48min, ahead of three Peugeots. However the first two finishers were ineligible for the cup as they were two-seaters and the rules called for at least three seats. A report for the French Institute of Civil Engineers predicted that motorcycles would be no more than a curiosity.

AND, FOR YOUR delectation, here’s how the big race was reported at the time: “The start was given to the first vehicle at midday, and the others followed at intervals of two minutes. As the contest was one of speed, it was not to be expected that the competitors would take any special precautions to ensure safety, and not long after the carriages had left Versailles, it was reported that one of the two Serpollet vehicles, driven by M Serpollet himself, had come to grief at a dangerous turning, and had fallen over a bridge. The vehicle was smashed, but, fortunately, none of the occupants were injured. The lead was taken by one of the smaller steam vehicles belonging to Dion, Bouton et Cie, which arrived at Etampes at 2hr 15min, followed a quarter of an hour afterwards by a petroleum carriage of Panhard et Levassor, and driven by M Levassor. About twelve minutes were spent in coaling up the steam carriage, but this was made up for by the faster pace on the road. Not long after leaving Etampes, the De Dion carriage came to grief through the breaking of an axle, and M Levassor thus took the first position, entering Tours at 8hr 40min. From this point, he continued to add to his lead, and reached Poitiers—338km—at 12hr 45min on Wednesday morning. Two hours afterwards, a Peugeot carriage arrived, followed, at long intervals, by six other petroleum vehicles, of which five belonged to the same firms, and the last to M Roger. The sole remaining Serpollet carriage made its appearance at 8hr 16min on Wednesday evening, while the large De Dion traction vehicle arrived at 9hr 30min. Nothing had then been heard of the electric carriage constructed by M Jeantaud, and it appeared afterwards that it had given up. This carriage was driven with the aid of Fulmen accumulators, which were changed along the route. The accumulators were conveyed to the different points by a special train, and the cost of the race to the owner is said to have been upwards of £1,000. The petroleum bicycles also fared badly, as one belonging to M Millit, of Persan-Beaumont, only went a part of the distance, while the Wolfmüller-Hildebrand bicycle also gave up after a long series of accidents. The ranks of the steam and petroleum carriages were thinned out considerably

by the difficulty of making repairs, which were necessitated very frequently by the excessive jolting of the vehicles over the ill-kept pavements of the different towns through which they passed, to say nothing of the vibration of the carriages caused by the motors. Before reaching Angoülême one of Panhard et Levassor’s carriages was thrown over by a dog, and a wheel was smashed, thus putting it out of the running. The leading vehicle, however, continued to make good headway, and M Levassor arrived at Bordeaux in 10hr 32min. Three Peugeot carriages completed half the distance between 2hr 10min and 5hr 23min, and then came Panhard et Levassor and Roger, while the Serpollet steam carriage did not reach Bordeaux until one o’clock on Thursday morning. The traction vehicle of Dion Bouton et Cie had long since given up, in consequence of repeated accidents; and, in fact, contrary to anticipations, steam made a very poor show indeed, even to the extent of the vehicles having to be pushed up the gradients. As some of the competitors allowed strangers to help them in pushing their vehicles, a great many protests have been laid with the committee, which is now occupied in considering them. Another drawback to these carriages is the blowing off of steam, which, in spite of every precaution, cannot be entirely avoided. On the return journey M Levassor continued to remain in charge of his carriage, and without further incident he arrived at the Porte Maillot, in Paris, at 12hr 57min on Thursday afternoon, having thus occupied less than 49 hours in covering the distance. This time would have been greatly reduced if it were not for the fact that owing to his lamp being smashed he was obliged to slow down during the night. The carriage showed very little evidence of the hard work to which it had been put, and during the long journey it hardly required any attention whatever. The next three arrivals were Peugeot’s carriages, one reaching Paris at 6hr 37min, another at 11hr 55min, and a third at midnight on Friday. Under the condition that the first prize was to be given to the owner of the first carriage containing’ four persons, the award was made to Peugeot for the vehicle which arrived fourth, and Panhard et Levassor only secured the second prize. The results, therefore, are as follows: First prize, the Fils de Peugeot Frères, of Valentigney, Doubs; second prize, Panhard et Levassor, 19, Avenue d’Ivry, Paris; the third and fourth prizes to the Fils de Peugeot Frères. The only steam carriage that completed the journey took 90 hours to cover the distance. It belonged to M Rollé of Mans—Sarthe—and was constructed about 20 years ago. Of the 28 vehicles that started from Versailles only 12 were able to reach Bordeaux, and eight completed the journey within 100 hours, when the race was declared closed. The result is not perhaps quite so good as to justify the hope that the difficulties in the way of adapting automatic carriages to everyday use are entirely overcome, but it is certain that a great many more competitors would have finished the journey if they had not been thrown so much on their own resources. Nor is such a hard test necessary to prove that the petroleum carriage, at any rate, can be conveniently employed for the ordinary purposes of road traction, though the fact that all the seven prizes were secured by petroleum vehicles places the superiority of this power beyond all question. It is noticeable, too, that the first five were all constructed upon the same system, that is to say, with the Daimler petroleum motor, of which a description has already been given in The Engineer. By employing a high explosion pressure, and working the motor at a high speed, it is possible to keep the weight very low, and, concealed in a box in front of the driver, the vehicle has a very neat appearance. The only difference between the systems employed by the two firms is that while the motor in the Panhard et Levassor carriage is in front, in the Peugeot vehicle it is placed in the rear, though in both cases the power is conveyed by a chain passing round the axle. The consumption of petroleum spirit in the Daimler motor is said to be about one pound per horse-power per hour, and the cost comes to about a halfpenny a kilometre with a carriage containing four persons, and rather less for the smaller vehicle.

“LONDONERS MUST HAVE these horseless carriages shown in the metropolis. The County Council should arrange for a display on our grand boulevard, the Thames Embankment, of the electrical tricycle, the petroleum carriage, and the steam waggon. They must he seen here as they have been in Paris.”—The Daily Telegraph

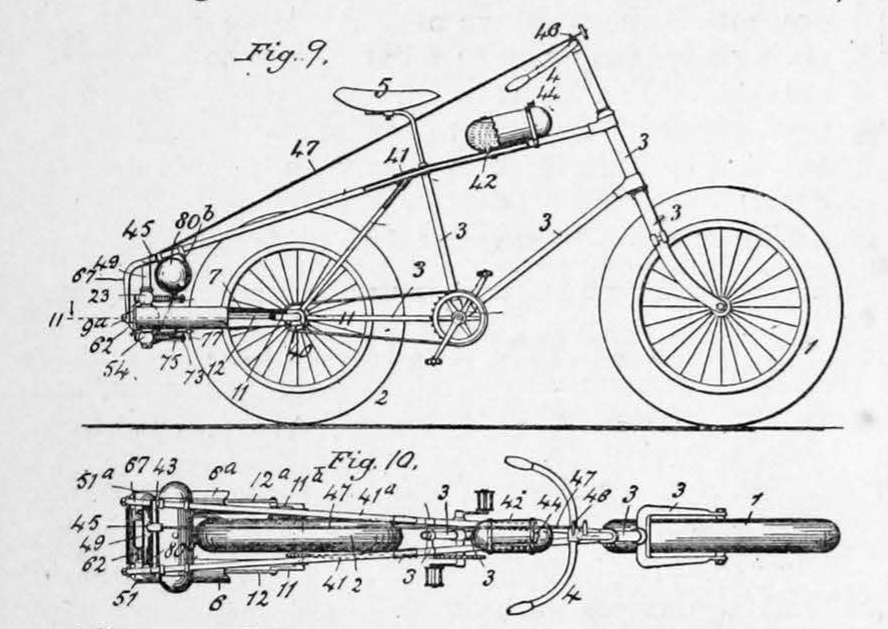

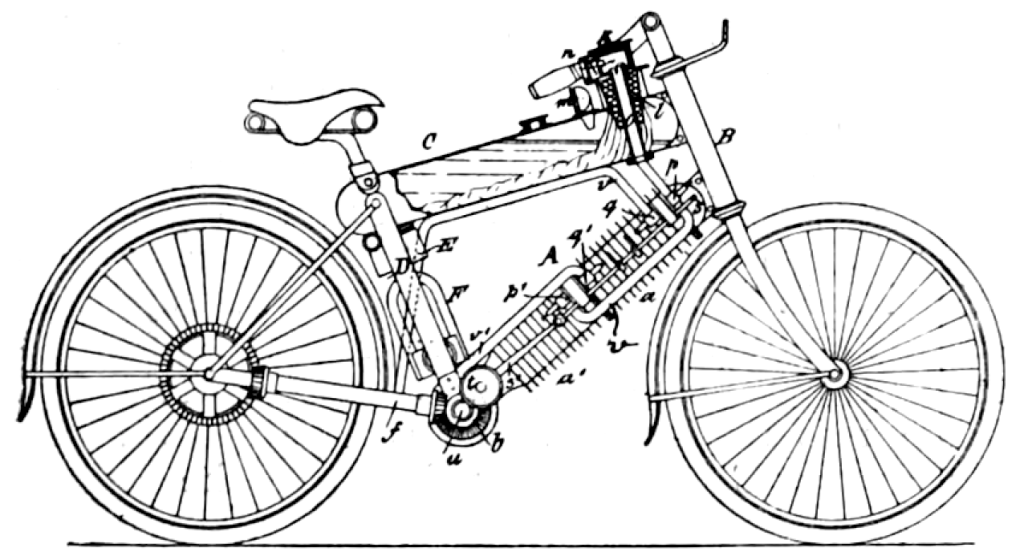

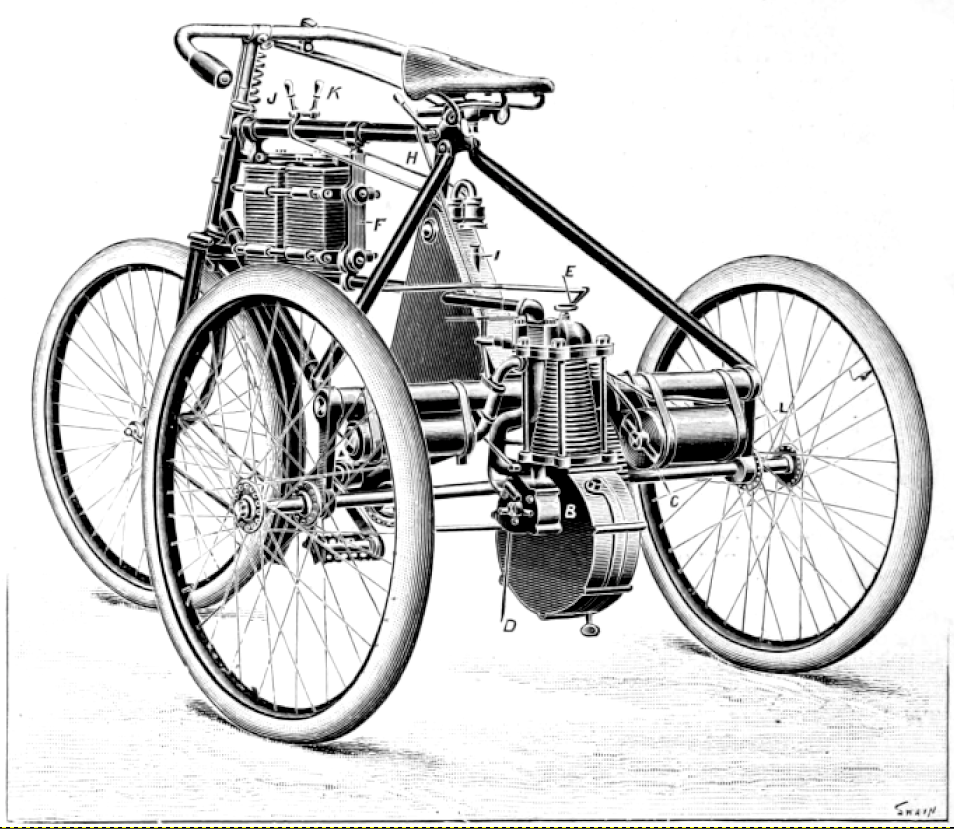

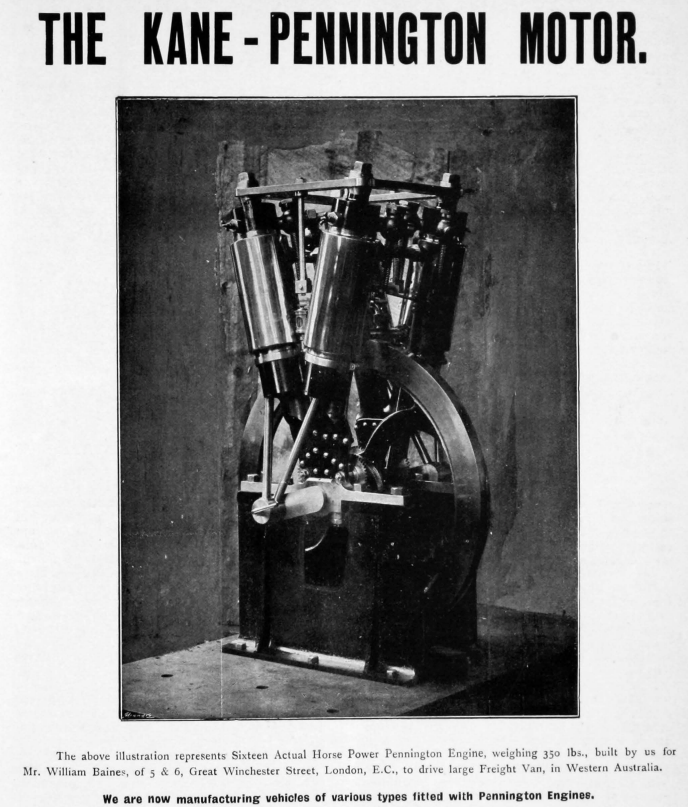

“WE HAVE ALREADY spoken in these columns of the Pennington engine which is attracting so much attention in America, and a few words concerning its construction will doubtless not be without interest to the readers of The Autocar. In the first place, we may say that the engine was first publicly experimented with about a year ago, and is the outcome of a series of successive developments which have been made in light engines by Thomas Kane and Company, of Chicago, Illinois, USA, who ten years since went into the business of manufacturing light machinery for the propulsion of boats and launches. The obtaining of the maximum of power with the minimum of weight was always the central point of their attention, and their Racine automatic engines and boilers, using oil for fuel, achieved a large success. Then, foreseeing that steam would in time be supplanted by a gas or gasoline engine using no boiler, they designed and built the Regan, and, later, the Kane electro-vapour engine, and claim to have been the first to use electricity for ignition purposes instead of fire. Their success in this line soon brought other similar engines on to the market, employing about the same principles and differing only in general construction, namely, making gas in a carburetter or vapouriser, and exploding it in the cylinder by means of an electric spark. This type of engine necessitated a large number of working parts, was necessarily constructed heavily to withstand the explosion in the cylinder, and to allow a large space for water jacket for cooling purposes, and required a heavy fly wheel to secure power and smooth running. The demand meanwhile called for a less complicated engine and one of fewer parts and light weight for stationary purposes, boat and vehicle use, and a thousand and one places where heavier power could not be used, and this ultimately led to the invention of the Pennington engine, which has been successfully used on motor cycles and light carriages, and is now built by the firm for all lines of work. Its general description is as follows: Ordinary

gasoline or kerosene oil is stored in a galvanised iron tank. Extending from this tank is a small pipe, and through this pipe the oil flows to the engine by gravitation, substantially as it does to an ordinary gasoline stove. A small primary battery is placed in any convenient position out of the way, from which a copper wire leads into the interior of the engine. It is a well-known law that rapid evaporation of any fluid produces cold; the more rapid the evaporation the more intense the cold. Pennington’s engine utilises this principle, and on the motor cycle no water is used for cooling purposes. On other engines for vehicles and marine and stationary work only sufficient water is required to keep an equal temperature, ie, about one gallon per horse power, and the water is used over and over again. For this purpose a small brass tube is slipped over the cylinder, which adds only a little to the weight, and gives the engine an attractive appearance. In all other engines of the gas or vapour type the explosive fluid is compounded and produced outside of the engine, by means either of a vapouriser or carburetter, and when thus prepared is pumped into the engine and there exploded. This produces only heat, and renders a water jacket necessary, as well as a large quantity of water for cooling purposes. The Pennington engine produces both heat and cold, as above described, and in such proportion that the temperature of the cylinder is never greater than that of an ordinary steam engine, and requires a minimum quantity of water. In a ¾hp engine there is only one cylinder, 2hp two cylinders, and in a 4hp four cylinders. Each cylinder is 2½in. in diameter, 6in. stroke. The engine runs 500 or more rpm as desired. The whole mechanism is extremely simple in construction, and is designed to be ignoramus-proof. There are said to be 14 chances for a locomotive engine to get out of order and fail to work. In an electric car motor 22 chances. In the Pennington engine them are but two, viz., the flow of fluid, and the electric spark. Both are very easily tested, and when both work properly the machine is bound to go. The cylinders are made of specially drawn steel tube, tested at a pressure of 8,000psi. The piston is made loose with spring rings, and needs no packing. It can be drawn out by loosening a single bolt, and the working parts seen. The balance wheel is utilised to start the engine, and a single turn is sufficient to set it in operation. In the motor bicycle no balance wheel is required, the start being effected by the pedals in the usual manner. As soon as the engine gets to work, it over-runs the pedals, which are connected with a ratchet gearing, and the rider can either pedal faster, and so keep ahead of the engine, and do some of the work of propulsion himself, or else put his feet on the rests, and ‘coast’ all the time. The engine is attached to the back wheel, the petroleum reservoir on the top of the frame, and the electric battery in a leather case beneath it. The oil is fed to the engine through the long

tube at the back, and the regulation is entirely under the control of the rider by a connection from the handle-bar, the regulation of the supply of oil regulating the speed of the machine. By turning a button on the handle-bar, the electric current is shut off, and instantly the cylinders convert themselves into air brakes. The bicycle, which has 4in tyres, thus obtaining the acme of comfort in riding, is, of course, built specially strong to stand the strain, yet with all this, and with engine and attachments complete, it weighs but 65lb, the weight of the engine and attachments alone being only 12lb. The electric battery will last for months, and is easily re-charged or renewed, whilst one charge of petroleum is sufficient for a run of 50-100 miles, according to gradients, etc., encountered. As to speed, the company claim to have done a mile in 58sec, and put the road speed down at from 6-50mph’ according to circumstances or inclination. The firm also produces a light form of Victoria carriage fitted with a 4hp four cylinder engine, and the entire carriage weighing about 140lb only. Doubtless practical engineers will be asking about efficiency, and whether the horse power of these little engines is actual or merely nominal. It may, therefore, be interesting if we quote the following extract from a letter received from Mr Kane last week by Mr Baines, the company’s representative here: ‘The invention grows upon us all as we make further trials with larger engines. To illustrate, a few days ago we tested one of our old type of cast iron engines, rated 2½hp. Under our old system of introducing gas it developed about 2hp in regular running. Putting in one spark and taking the fluid directly into the cylinder, it -developed 2.28hp. Substituting an electrode with a double

spark it developed 4.18hp. We attached a dynamo running 50 electric lights, and it did perfect work right along—in fact, it solves the electric lighting problem with gas engines, without any question. This problem has not hitherto been thoroughly solved in this country. We are now changing some ½hp old-style engines, and expect to develop fully 1hp, probably more.’ From this we fancy our readers will agree with us that on the face of it the Pennington engine seems to have about solved the motor question for light vehicles, more especially as ordinary petroleum—crude oil even—is used instead of the more expensive and more explosive benzoline. We may add that the English patents have been purchased by an English syndicate for a very large sum, a larger sum, we believe, than has ever been paid for any other petroleum motor patent, and that it will very probably he one of the series of engines which will be handled by the large company which is spoken of in another column. No engines are at present in England, but we understand that Mr Pennington leaves America today, bringing several specimens of the carriages with him, and that the public will ere long have the opportunity of seeing the vehicles at work.”

“A CORRESPONDENT TO The New York Herald speaks of a visit he recently paid to the factory where the Pennington motors are being built. He says that an engine of two horse-power has been fitted to a bicycle, the weight of the bicycle when equipped being only 65lbs, and this machine is reputed to have made a mile in the astonishing time of 58sec. The writer states that he was invited to take a seat on a tandem bicycle, the clever inventor riding with him. It was timed, and found to cover a distance of one mile in 1min 30sec. He was told that the machine was not even then being driven at its maximum speed, but on being asked if he would prefer to go at a higher pace he declined.”

“IN THE COLUMNS of The American Machinist, Mr John Randol, who, we understand, is an expert of some standing in American engineering circles, gives the following interesting report on the Pennington engine and a visit to the Kane-Pennington Works…During my first inspection of the Kane-Pennington motor, I thought I was not treated with the entire frankness due to an impartial observer, if he be allowed to observe a strange and wonderful thing. I saw a heat engine, for I suppose the explosion engines are as rightfully to be called heat engines as if they took their heat slowly and through the comparatively moderate and leisurely process of ordinary burning, instead of employing pressures established by the sudden and violent deflagration of some explosive compound. I saw, I say, a heat engine of such exquisite simplicity that a child might easily remember all of its few parts and their uses, and all so small and light that a child might use them for play-things; a machine so absurdly lacking in all the parts and appliances which I had been trained by example and theory to believe essential to the effectiveness of motors of its class, that if previous knowledge were not wholly error, this new wonder should not be able to even move itself; yet this incredible machine not only did move itself, but moved with such vigour of action as to drive loads far beyond its apparent possibilities…in some way, so far wholly unexplained, the great heat which in other explosive engines manifests itself in an inconvenient by-product, to be taken care of as best it may, is in the Pennington engine transformed into useful effect on the piston. I know that when the long, thin, first spark is not put through the charge the engine becomes weak and hot, and that when this first long, thin spark, this ‘mingling’ or ‘ripening’ spark, as Mr. Pennington calls it, is used, a common gas engine with its carburetter eliminated gives twice its ordinary effect on the crank…the two-spark mechanism of the Pennington motor…does not cost five cents, and yet when applied to the ‘Regan’ gas engine, largely built up to the present time by the Kane establishment at Racine, doubles the power of that motor. It is in the igniter, and in the double spark, or rather in the effect of the first spark, apparently, that the efficiency of the Pennington motor lies. This statement is as incredible to my mind now as it was when I first heard it from the lips of Mr Pennington, but this first spark seems to be the only possible agency through which this motor achieves its miraculous results, and gives us a heat engine which delivers in usable work a great part of the possible effect of the heat delivered to it, and so opens a new round of dazzling possibilities to the engineer…No fire, no water, no boiler, no carburetter—only a few pieces of steel, with a few brass-bushed joints, a battery weighing one pound, and a gallon of kerosene; put these with a bicycle, bringing the weight of the whole piece of wizardry up to 58lb, and a man may be carried by it on a smooth road a mile in fifty-eight seconds, as a man was carried on one of the asphalt-paved streets in the city of Milwaukee a few days since. To avoid the weight of reducing gear the diameter of the cycle wheels is dropped to twenty-two inches, and to give adhesion, and to avoid puncture, the pneumatic tyres are made four inches diameter, after Pennington’s specifications, and cannot be injured by a hammer and nail

in skilled hands; the attempt to drive the nail into the inflated tyre results in a simple rebound of the nail, the tyre remaining intact. To run a mile a minute with twenty-two inch diameter wheels requires over nine hundred turns; it is therefore certain, as the cycle did run a mile in fifty-eight seconds, that the motor can make about 920 turns per minute. I was one of the riders on a Pennington tandem weighing 106lb over a poor block pavement, railway tracks, etc; the time was not taken; it was quite sufficiently swift, however, to satisfy all my longings for speed…I hardly think there will be a dissenting voice from the assertion that this feat of the Pennington motor cycle is one of the most marvellous achievements of mechanism ever seen. There is evidently some heat-absorbing or diverting or abstracting element in operation in the Kane-Pennington engine not commonly present in the gas engine, and it is difficult to see what this can be, if it is not the truth that the heat of the cylinder walls is absorbed by the incoming charge previous to the moment of the ignition, or else transformed into work on the piston, as it seems impossible that the gases after ignition should be otherwise than very hot indeed. There is no visible discharge of vapour, and no evident odour, except in case of an over-admission of oil, and an over-admission of oil leads to a loss of efficiency which makes its continuance an impossibility. The one great mystery is the coolness of the naked cylinders, which should be red hot at the end of the first twenty strokes or so of a run. Chemists are familiar with the establishment of low temperature pressures, but pressures established by explosion are not cold as a rule, and the gas engine has always been hot. The Kane-Pennington shops are making, or have made, general trials of the water jacket cylinder; the 2½x12in expansion engine is jacketed and piped with top and bottom natural circulation pipes to a small water tank, which a run of some length did not seem to heat very much. The cylinders run perfectly well naked, with no cooling element more than their inevitable exposure to the atmosphere.”

“AT LAST WE ARE HAPPY. We have seen Mr. Pennington, and we have seen his motor, and we shall be happier still when we have seen it at work. Mr. Pennington, who arrived in this country late on Friday evening of last week, is a tall finely built man, with a deeply thoughtful expression of countenance, and a way of expressing himself which of itself goes very far towards carrying conviction with it. It is very evident that he has given deep and close attention to every detail of his little machine. The one we saw was a two-cylinder bicycle motor, and, as far as we could judge from an inspection, it bore out everything which has been said concerning it. For simplicity of construction there is nothing we have yet seen which can in any way approach it, and it only remains to be proved that the little midget will develop, as Mr. Pennington says it will, something over two brake hp, with a very much higher indicated record still.”

FILE THIS ONE under the heading “not directly relevant to the evolution of motor cycles but to good to ignore”—a row broke out between Pennington and the British manufacturer Root & Venables over the merits of their respective products. The Autocar consistently took Penington’s side leading to this no-nonsense letter in that illustrious organ: “Re The Pennington Motor—With regard to the remark made by you on behalf of Mr Pennington in your last issue, ‘but that until Messrs Roots & Venables can produce and establish their engine’, Mr Pennington must be singularly ignorant of what has been done in this country in connection with oil engines, and it must be noted we are now speaking of oil engines, not spirit engines. Mr. Roots was the first to make an oil engine to run in this country, or in any country. He was closely followed by Messrs. Priestman, who placed theirs on the market first. It was fully a year after this that an oil engine was produced on the Continent, and quite two that one was produced in the United States. For the past five years the Roots oil engine has been sent to most parts of the world, and many hundreds of them have been sold. The Roots oil engine is everywhere known favourably in Great Britain, New Zealand, India, Australia, South Africa, South America, Japan, etc, etc, and has been purchased among others by the Indian Government, by Eastern Princes, and by the Brighton and South Coast Railway Co. It is undoubtedly the most reliable and most automatic (ie free from attention) of any oil engine in the market. With regard to carriage oil motors we made one in 1893, and exhibited one at the Stanley Show in 1894, and since then we have sold them in France, India, and in this country also. All our motors use kerosene or Russolene of a specific gravity of 0.8 to 0.835. Our works are run day by day from 7.30 to six with a horizontal oil motor, using oil of 0.831, and having the high flash test of 130°; we shall be glad to show anyone and everyone our motors at work or otherwise, and we are willing to prove all that we claim. Any person may bring a sample of kerosene up to the specific gravity and flash test named, and we will put it into the engine and run it in anyone’s presence, or conversely we are prepared to supply a small quantity of the oil we use for any person to try the specific gravity and flash test. We shall be glad for every person to satisfy themselves; there is nothing we desire to hide. Again, we propose to Mr Pennington a test of our motor against his, and we make the following definite proposal under the auspices of The Autocar. We will place one of our carriage motors anywhere in London the editor appoints, Mr. Pennington to do the same, and we name three gentlemen well known, Professor Unwin, Professor Kennedy, Professor Robinson, one of whom, whichever Mr Pennington may select, to be asked (1) to test the engines and decide which motor gives the nearest approach to the BHP it is stated to give, both being run for four hours with full brake load; (2) what fuel from the point of view of safety each motor uses for starting or running; and (3) which costs most per BHP per hour. The loser to pay all costs, the competition to take place within three weeks, and we propose March 4th. We are very sorry if Mr Pennington considers our letters discourteous. We have read them through again to see if there are any indications of this, but we fail to find any. Our sole object is to elicit the truth; this, we believe, is manifest to everyone, and if Mr Pennington still fears to meet the competition everyone will draw his own conclusions. With regard to Mr New, we are not so discourteous as to call his letter ‘utter nonsense’, the words he applies to ours, but as he is stated to be an electrician, we would ask him to give a direct positive or negative to this question: Does he believe that upon anyone’s mere instruction one spark of electricity can be persuaded not to ignite while the next one will, or, in other words, that any person by wishing can induce an electric spark to alter entirely its usual action and behaviour?

Roots and Venables.”

[We are glad to find that Messrs Roots and Venables have seen fit to alter the tone of their correspondence. This letter was received too late for publication last week.—Ed.]

“IT WAS SCARCELY to have been expected that with the universal attention which is being paid to the autocar question throughout the length and breadth of the land, and the absolute certainty that all legal restrictions will immediately be removed, we should be long without some definite movement being made to introduce the vehicle commercially into this country, and we are now enabled to inform our readers that a company on a very large scale is at present in course of formation, which will immediately undertake the manufacture and introduction of this vehicle into England. Last week we had conversation on the subject with Mr HJ Lawson, who was intimately associated with the early days of the cycle movement, and who is now busily engaged in organising the company. Mr. Lawson recognises the immensity of the business before him, and has had the foresight to secure agreements with the owners of the principal motors, which, of course, are the key to the situation, and in doing so has already paid out some £16,000 as deposits to secure contracts. The two principal petroleum motors which will, we understand, be handled will be the Pennington engine and the Daimler motor, which, up to now, has the most striking record of any, having practically vanquished all competitors in the Paris-Bordeaux trials of last June, and being now almost the only engine utilised upon the large number of machines in use throughout France. No attempt will be made in any way to obtain a monopoly of the horseless carriage business, but the firm will virtually. secure a monopoly of the manufacture of practical motors covered by the large and important series of patents referred to. We may add that the capital of both the Daimler and Pennington syndicates is £100,000, some one-half of which represents actual cash paid for the patents. These syndicates are entirely private concerns, and arrangements have been made with them by Mr Lawson, on behalf of the new company, for the exclusive right of manufacture under royalty of the articles covered by the respective patents. In addition to these, what are believed to be master patents of value in the direction of both electric and steam motors, as well as the manufacturing rights of several entirely new forms of autocar, have been secured, and the very large capital of the company will enable it to introduce the autocar business into this country in a fit, thorough manner, and to experiment with and secure the rights over new inventions of value to the movement as they appear.”

THE HONOURABLE EVELYN ELLIS ordered a left-hand-drive motor car to be made to his own specifications from the Paris firm of Panhard-Levassor, powered by a 709cc Daimler engine developing 3½hp at 7000rpm. The car was driven from Paris to Le Havre, shipped to Southampton and by train to Micheldever station in Hampshire. From there, on 6 July, Ellis drove home. His passenger, Frederick Simms (who we’ll be meeting again) described the journey in the Saturday Review: “We set forth at exactly 9.26am and made good progress on the well-made old London coaching road; it was delightful travelling on that fine summer morning. We were not without anxiety as to how the horses we might meet would behave towards their new rivals, but they took it very well and out of 133 horses we passed only two little ponies did not seem to appreciate the innovation. On our way we passed a great many vehicles of of all kinds (ie horse-drawn), as well as cyclists. It was a very pleasing sensation to go along the delightful roads towards Virginia Water at speeds varying from three to twenty miles per hour, and our iron horse behaved splendidly. There we took our luncheon and fed our engine with a little oil. Going down the steep hill leading to Windsor we arrived right in front of the entrance hall of Mr Ellis’s house at Datchet at 5.40, thus completing our most enjoyable journey of 56 miles, the first ever made by a petroleum motor carriage in this country in 5 hours 32 minutes, exclusive of stoppages and at an average speed of 9.84 mph. In every place we passed through we were not unnaturally the objects of a great deal of curiosity. Whole villages turned out to behold, open mouthed, the new marvel of locomotion. The departure of coaches was delayed to enable their passengers to have a look at our horseless vehicle, while cyclists would stop to gaze enviously at us as we surmounted with ease some long hill.” Ellis was deliberately testing the law that required all self-propelled vehicles on public roads to travel at no more than 4mph and to be preceded by a man waving a red flag. He was not arrested and, as we’ll see, the Act was repealed in 1896.

“THE DAIMLER SYNDICATE has received no less than 73,000 letters during the past three months from persons desirous of being interested in the horseless carriage movement in this country. The prospects of the new company look rosy.”

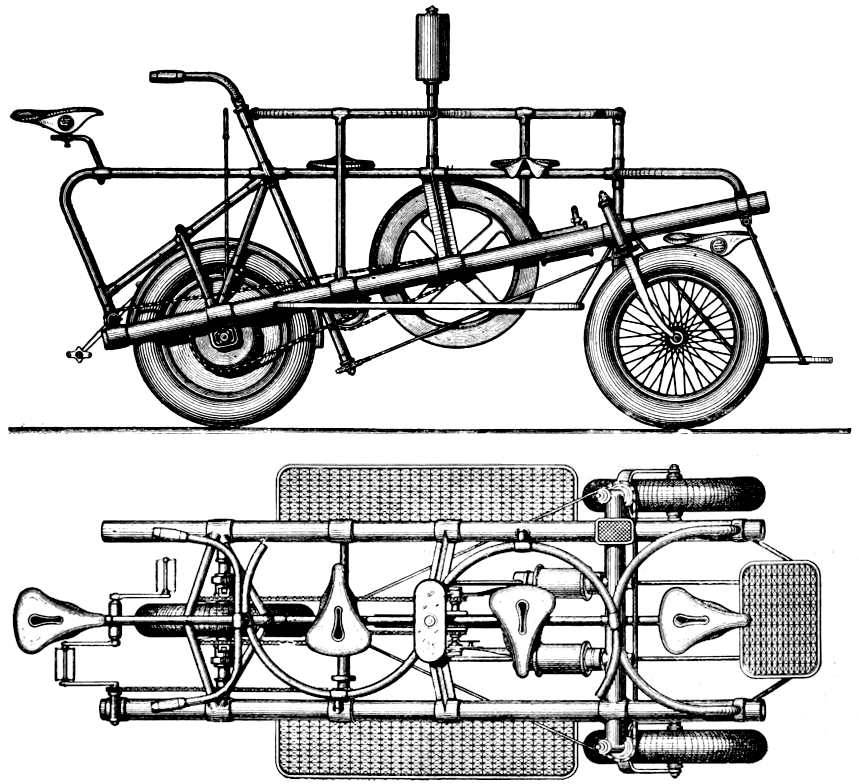

“ONE OF THE NEXT great advances in matters pertaining to the army in time of war will, in the opinion of Major-General Miles, of the American army, be in the adoption of horseless or automobile vehicles for the transportation of ammunition and supplies.”

“ALREADY, SAYS The Christian World of the 7th, the petroleum bicycle has made its appearance in London streets. Yesterday one of the genus might have been seen wending its way down Wellington Street, across the crowded Strand, where the rider dismounted, proceeding over Waterloo Bridge.”

“OUR AMERICAN COUSINS are already feeling inclined to crow over ‘effete Old England’ on the autocar question, although they have to admit they take a back seat as compared with France. A Chicago journal says: ‘It would appear that as far as English efforts in this line go American inventors are ahead, and their work in the field of motor cycles, as in that of bicycles, will lead that of the English makers. There ought to he a great market for these motor cycle vehicles in a hot climate, where horses sometimes suffer greatly from heat.'”

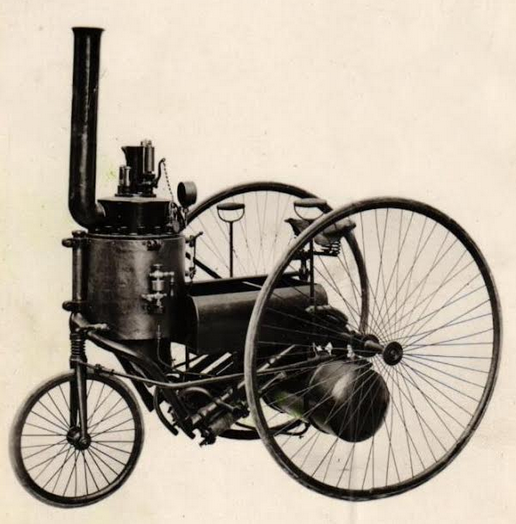

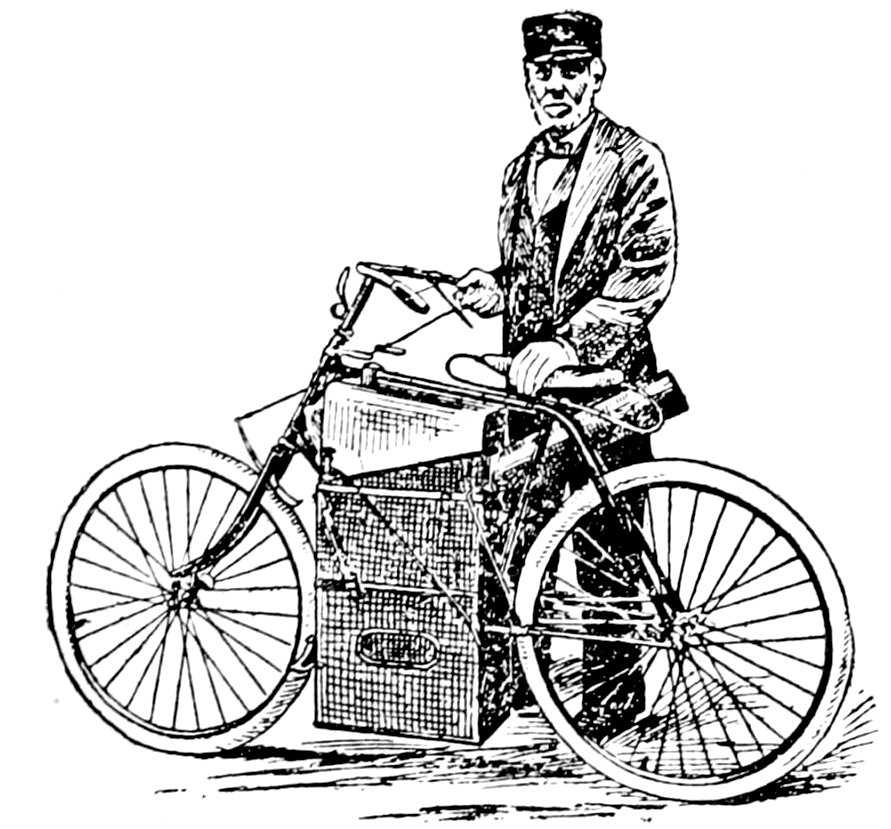

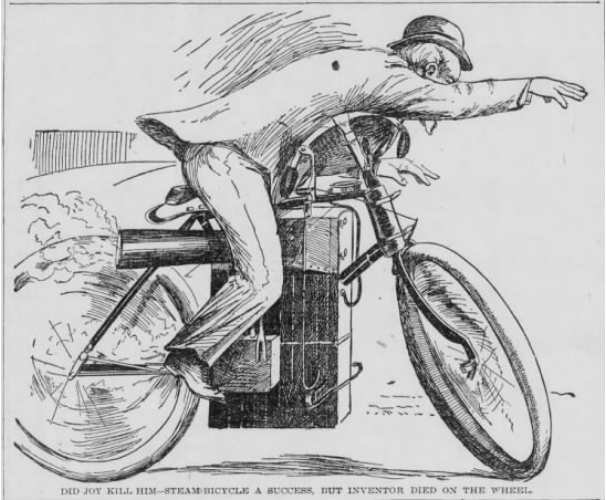

“MR JOHN GEORGE INSHAW, of Cheston Road, Nechells, Birmingham, sends us a photograph, which we reproduce, of an experimental steam carriage which he built in 1881. This carriage was, he says, well known in Birmingham and district, and its working was most satisfactory. The only reason he had for discontinuing his experiments was in consequence of the law prohibiting the use of steam-propelled carriages on the common road, although this carriage made no more noise than an. ordinary vehicle, and the exhaust steam, being entirely condensed, there was nothing against steam, which Mr. Inshaw says he is very much in favour of now, so much so indeed that he intends making another carriage as soon as the law has been repealed, which, naturally, he hopes will be very soon. Mr Inshaw gives the following particulars of this carriage: The boiler was almost entirely composed of steel tubes, and would generate steam in about 20 minutes to a pressure of 180-200psi, finding steam for two cylinders, 4in bore, 8in stroke. There were three different speeds for hill-climbing, etc, and the engines could be thrown out of gear for downhill, etc. There was also double driving gear, reversing gear, and, in fact, all the necessary contrivances were to be found in this machine. The steering was very satisfactory and quite easy to manage. When loaded with 10 passengers, fuel, and water, this carriage weighed 35cwt, and the speed on a good road averaged 8-12mph. The steerer had entire control over she carriage; in fact, far more than a coachman has over a pair of horses, and during the whole of his experiments, which lasted for several years, our correspondent says he never had the slightest accident of any kind.”

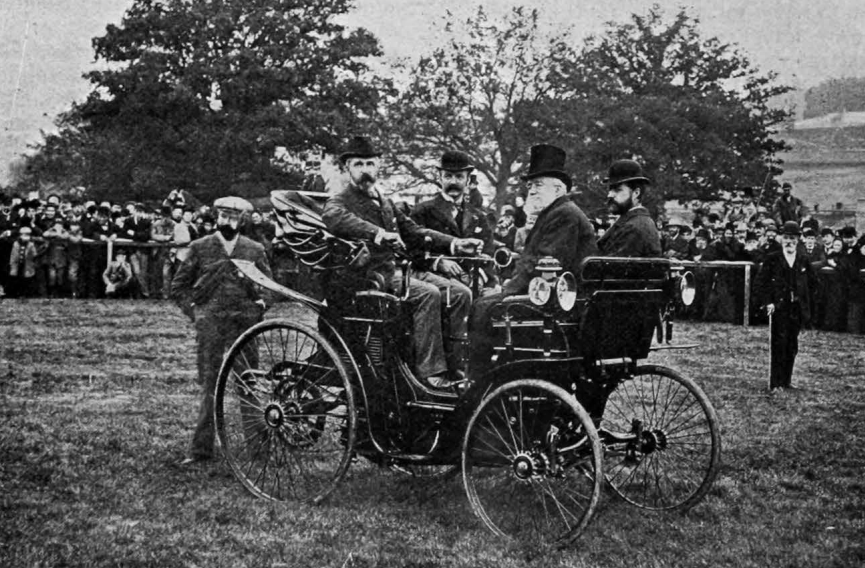

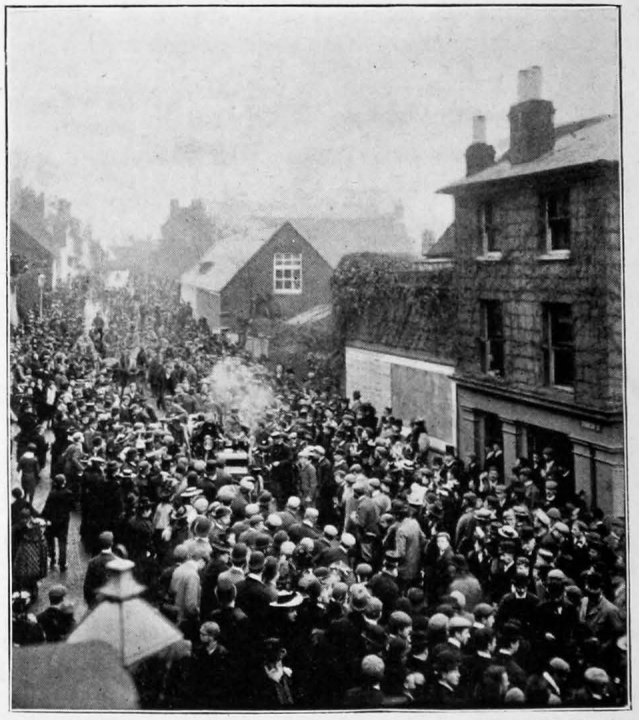

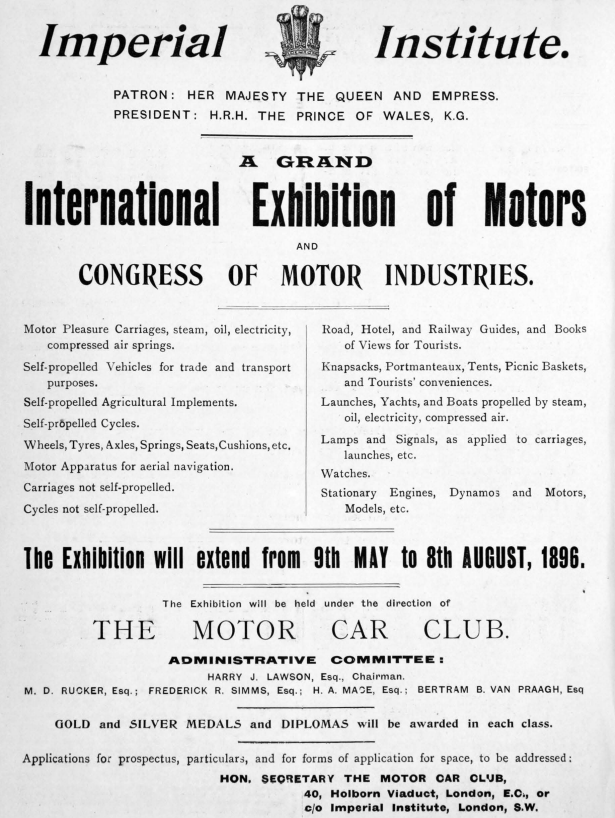

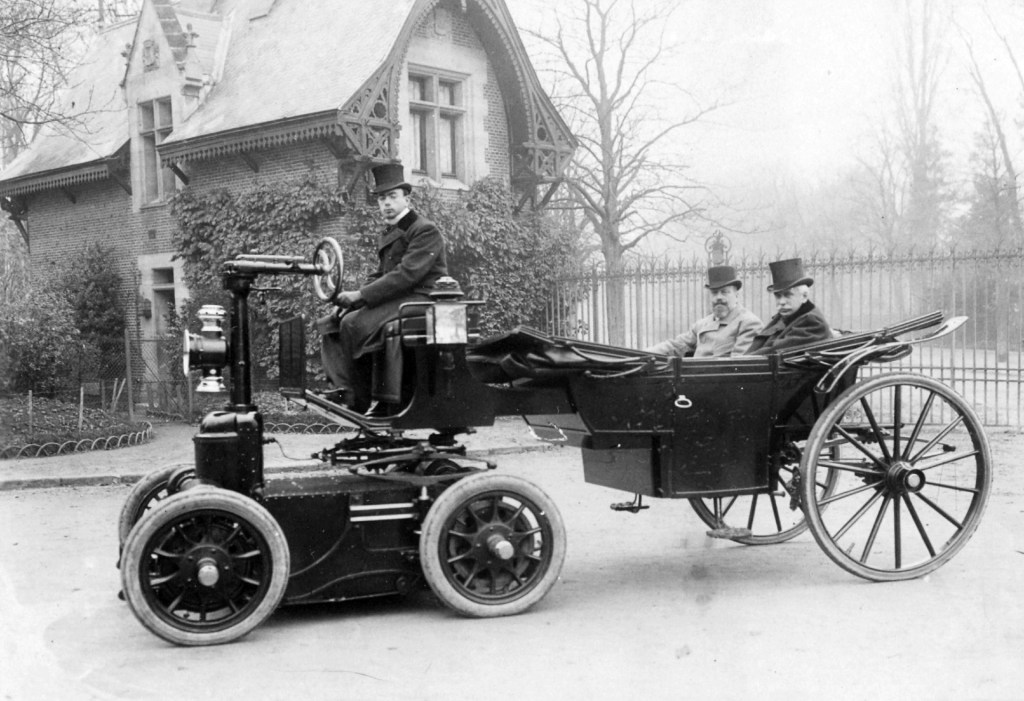

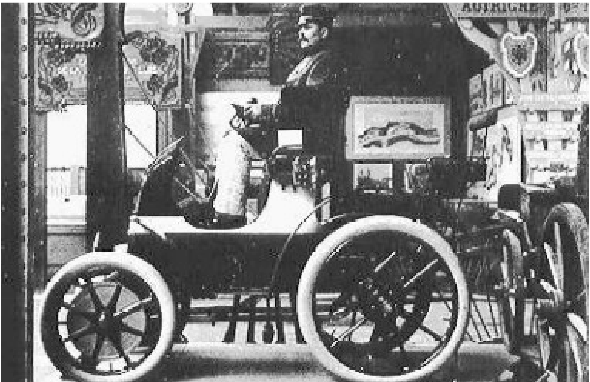

WEALTHY ENTHUSIAST AND Mayor of Tunbridge Wells Sir David Salomons teamed up with Frederick Simms to stage the first ever motor vehicle show. There was a grand total of five exhibits—two cars, a fire engine, a steam carriage and a trike. Among the spectators was one Harry J Lawson who clearly saw a great future for petrol power —he bought the British rights to Daimler engines from Frederick Simms and made a serious attempt to dominate the nascent British industry. The great day was recorded in the first issue of The Autocar: “The mayor of Tunbridge Wells, Sir David Salomons, deserves exceeding well of every member of the travelling community who desires to improve the means and facilities of vehicle transport over the roads of the country by the exhibition engineered by him in the grounds of the Tunbridge Wells Agricultural Show on Tuesday, Oct 15th last. When the day arrives, and by all surrounding signs the time is not far distant, when for many purposes a horsed vehicle will look as quaint as did the horseless chariots seen by us at the Wells a fortnight since, this exhibitive trial will rank for this class of vehicle very much on an equality with that memorable trial of locomotives, in which the famous old Rocket so completely defeated the engines opposed to it at Rainhill just sixty-six years ago. But in the present uncertain state of the law, the motor vehicles at Tunbridge hardly had fair play. They were obliged to demonstrate their pace and handiness over rough soft turf, a surface over which, under what should be the ordinary course of things, they would never be asked to travel. The trials brought quite a crowd of engineering notabilities to the Wells, to say nothing of the press representatives, and quite five thousand spectators, attracted by the novelty of the show. The list of exhibits promised six pieces, but of these five only materialised, the tricycle of the Gladiator Co not being in evidence. Punctually at three o’clock Sir David Salomons entered the ring, seated in his visa-vis, built by Messrs Peugeot, of Paris, and fitted with a Daimler engine by Messrs Panhard and Levassor, followed by the Hon Evelyn Ellis, with a carriage made by Messrs Panhard and Levassor, and also driven by a Daimler engine. This carriage excited much interest, as it is practically a duplicate of the vehicle that arrived first in the Paris-Bordeaux race for automobile vehicles this year. Following came a steam horse by Messrs de Dion & Bouton, of Paris, but as this is really only an improved, albeit greatly improved, form of traction engine, it hardly comes into the category of motor vehicles. It was attached to a landau occupied by two ladies, and as the front wheels and fore-carriage of the carriage had been removed, and the forward part thereof was hoisted upon and attached to the steam horse, it rather suggested a collision between the two, in which the steam horse had scored by the demolition of the fore-carriage, etc, and the capture and bearing off the landau. Dion

and Bouton’s tricycle, with petroleum motor, fired by electric spark ignition, came next, and, naturally, drew the particular attention of the cycle experts. A fire engine, designed for a country house, and worked, so far as the water jets were concerned, by a Daimler petroleum engine, was run on to the ground by a detachment of the local fire brigade under Captain Tinne, and the motor put into action. The motor vehicles and the tricycle made many circuits of the ground, and exhibited very remarkable speed capacity, considering the soft and lumpy nature of the turf. These disadvantages militated particularly against the show made by the Dion-Bouton tricycle, for the machine, excepting for the addition of the motor, placed very neatly and unobtrusively behind the saddle pillar, and nicely enclosed in a nickel casing, was in all respects an ordinary tricycle, and consequently not built for running over rough pasture. Sir David, who was much cheered as he passed, stopped from time to time and gave short descriptions of his own vehicle. As may be seen from our illustration, the carriage takes the form of a Victoria body with a seat for two in front; the back seat, also accommodating two passengers, is raised considerably above that facing it, in order that the directeur may have a good view ahead. His starting and stopping lever, and his speed

variation lever, is placed close to him on the right, and a foot lever is conveniently fitted for the purpose of throwing the engine out of gear, and for actuating the brake on the shaft that carries the gearing. A lever brake is also fitted which has several actions; it throws the engine out of gear, brakes the gear shaft, and both driving wheels. The engine is 3¾ horse-power, but will develop if more if required. The average speed on a good level road is about eight miles per hour, but fifteen miles per hour is attainable when desired. The engine, etc, is all neatly packed away under the back seat, and, except for the driving chain running naked at one side, there is no indication of machinery in connection with the vehicle, except the slight noise and smell of warm spirit as it passes, and the somewhat serious vibration when the carriage is stopped. The steering is done by a bicycle handle-bar in front of the directeur, which actuates the front pair of wheels, which run free of each other on a fixed axle. The axle of the rear driving wheels is fitted with differential gear. to allow of independent rotation when turning. The vehicle weighs 13cwt, and will run from 180 to 200 miles without a fresh charge of petroleum. The petroleum reservoir is well removed from the motor, being formed under the front seat. Five gallons of benzine, costing about 11d per gallon, is stored in this tank, from which it is pumped by a small pump into a smaller vessel which supplies the fuel for the two burners which keep the small platinum ignition tubes at a red heat. This having been done, a pump like a syringe is attached to the small tank, and, all tubes having been closed, is worked until the

pressure reaches a certain point indicated by the gauge, then a little spirits of wine is poured on the cups, one of which surrounds each burner. This when lighted heats the burner, and in two minutes the valves may be opened and the burners lighted. Very quickly the ignition tubes are red-hot, and the engine is ready to start. The engine is started, and the driving gear thrown into gear after the directeur has taken his seat. To stop the vehicle the gear is thrown out, and, though the vehicle stops, the engine rattles on as though it had not another moment to live, and causes so much noise and vibration that one is heard with difficulty, while the vehicle appears seized with a species of Brobdingnagian ague. This, we were informed, is to be averted in future by the fitting of a band-brake, which will cause the motor to moderate its transports when let loose for a while. In order to make the explanation clearer, we might say that, except for special fitting, these motors are practically the same as gas engines, except that the petroleum is vaporised at the moment of employment, and that it is the explosion of the gas so produced which gives the necessary impulse. The vehicle shown by the Hon Evelyn Ellis was driven by a similar motor, but the body took the form of a waggonette with seating accommodation for four. Both Sir David Salomon’ and the Hon Evelyn Ellis’s vehicles mounted the hill in the show-ground, which has a gradient of about one in forty, in excellent form. Of the motor attached to the Dion and Boston tricycle we are, unfortunately, unable to give much detailed description. It is neatly and unobtrusively fixed behind the saddle pillar, and the connection made there between the motor and the main axle. The motor in this case, however, is only to be regarded as an auxiliary, for the tricycle is fitted with the usual pedals, cranks, and chain, resource to which was always had when the machine was to be started, or was put at the hill. The motor is of the

same character as that referred to above, the chief difference being the employment of the electric spark for the ignition of the petroleum vapour in the cylinder. The storage battery is carried on the top tube, close up to the steering socket, and a Rumkhorf coil carried on the bridge. The machine shown weighed ninety pounds, and was priced at £50. These two characteristics may prove considerable factors in selling them by the gross. After a time Sir David evidently steeled himself to dare the majesty of the law, for the carriages left the ring and came out upon the excellently laid highway which stretches between the Agricultural Show Ground and the town. Directly the wheels of the automobiles revolved upon the surface of the high road, the serious handicap imposed upon their movement of propulsion by the rough turf of the ring was plainly apparent. Moreover, the experiment must at once have laid the ghost of all fear with regard to danger to pedestrians or fright to horses. The roadway was lined with spectators, and horses and carriages were stationed at very frequent intervals. The motor vehicles were shown to be under perfect control, and no one of the horses so much as lifted an eye as the horseless carriages sped somewhat noisily by. At the close of the proceedings, it was felt by all present that the occasion undoubtedly heralded the dawn of a new era in vehicular propulsion on the high roads of this country, and that for manifold purposes the horse would shortly be reckoned de trop. The whole of this undertaking to make something like a reasonable start in demonstrating the entire practicability of motor-driven carriages arose with, and its expenses were defrayed by, the Mayor of Tunbridge Wells, Sir David Salomons, to whom the thanks of the community at large, to say nothing of those of over-worked equines, are certainly due. Changes are rapid in these days, and the hour of the motor-driven road vehicle is close at hand.”

SIR DAVID SALOMONS wrote to The Daily Telegraph: “The vast number of communications which have reached me since the day of the announcement that a horseless carriage exhibition would be held in this town, and which correspondence still continues, proves conclusively that a widespread interest in this mode of locomotion exists throughout Great Britain. From a perusal of these letters it is evident that a desire is prevalent to form an association to deal with this subject, which closely affects agricultural, trade, and private interests. I have no right, nor have I the desire, to constitute myself sole guardian of this kind of locomotion in England, though I have so far taken an active put in the movement, for the reason that I felt it was necessary for someone, known to be a lover of horses and quite independent of any pecuniary stake in self-propelled vehicles, to make the start. May I now request that your influential columns give publicity to the fact that I am willing to receive communications from all those who are desirous of joining an association to deal with self-propelled traffic.”

“A MEETING FOR the purpose of forming an association to further the interests of self-propelled traffic was duly held on Tuesday last, and the association is now un fait accompli, with Sir David Salomons at its head. A provisional committee or council has been formed, and we may look upon the association now as in full working order. We wish the deputation which is to wait upon Mr [Henry] Chaplin [President of the Local Government Board] with regard to the proposed measure for amelioration that success which its object deserves, and we would impress upon it the importance in all negotiations of obtaining, if possible, absolutely unrestricted freedom for the use of the new vehicle, and the consequent development of the new industry…The users of autocars will always be amenable to the ordinary byelaws regulating carriage traffic, and they will in their own interests take particular good care that careless driving or high speed in crowded situations are avoided, and we are not likely to meet with a tithe of the recklessness which is seen every day with horse traffic.”

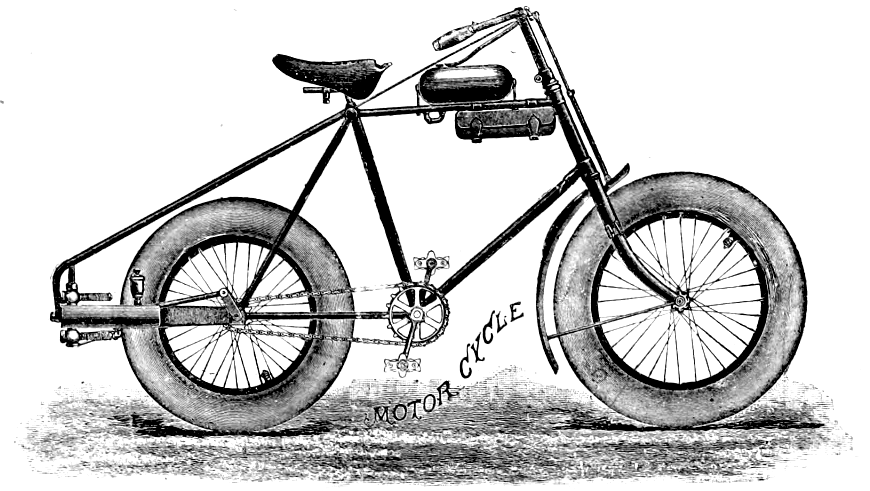

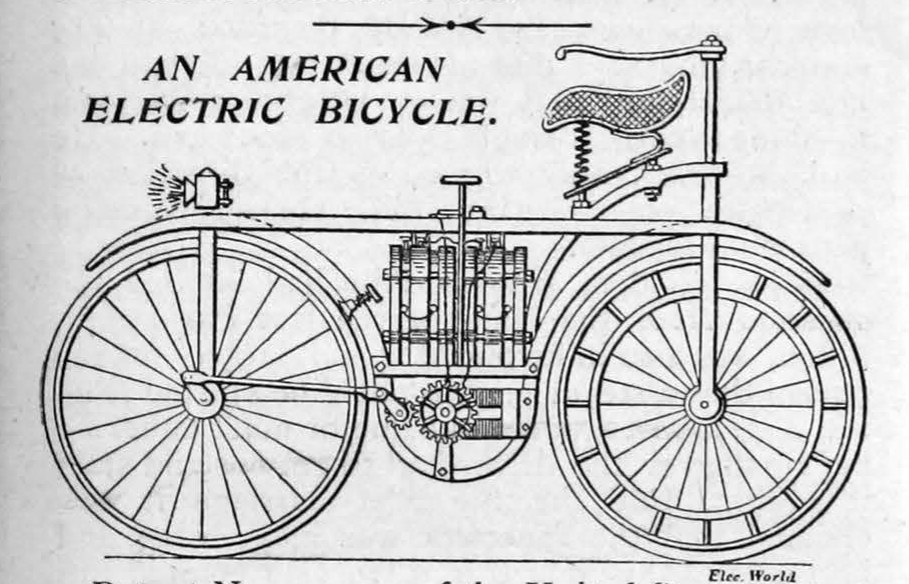

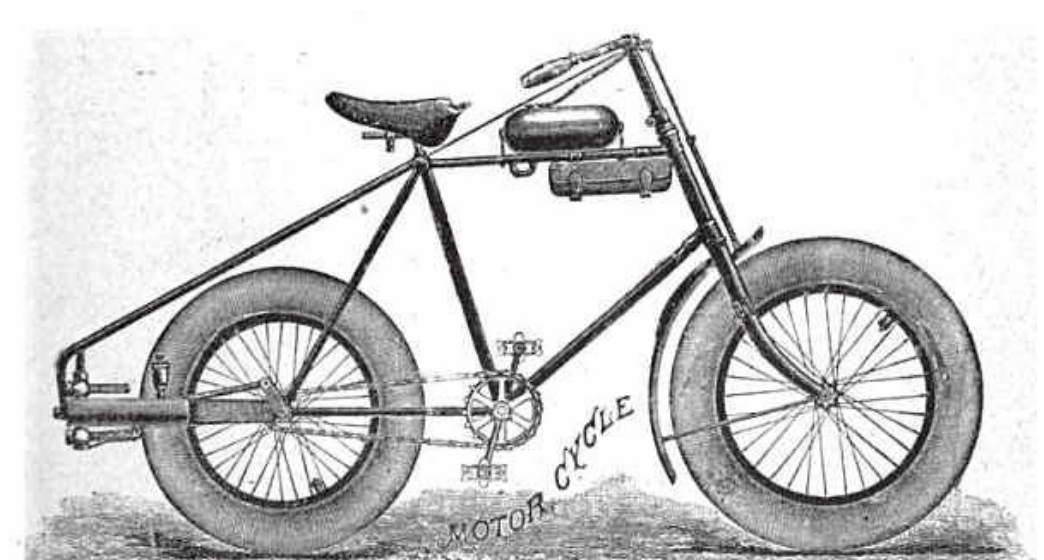

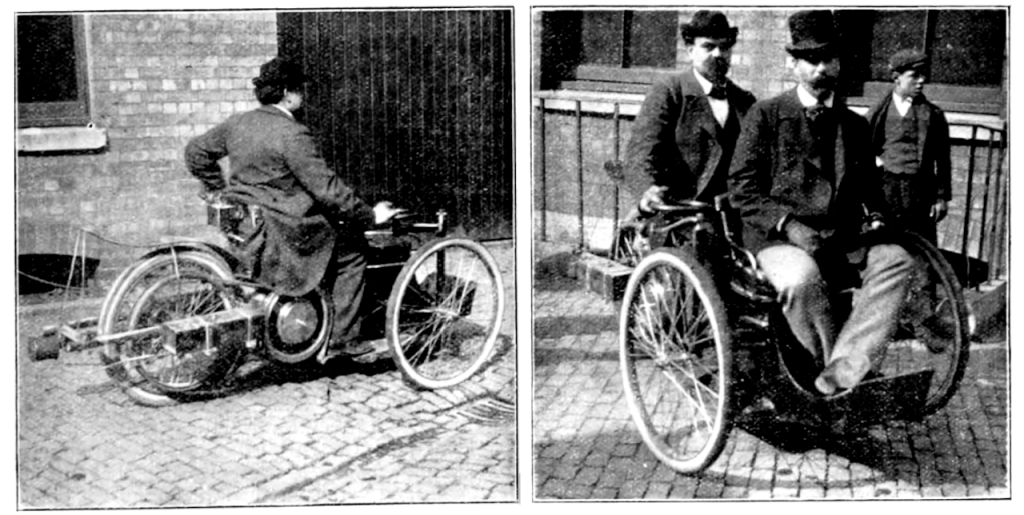

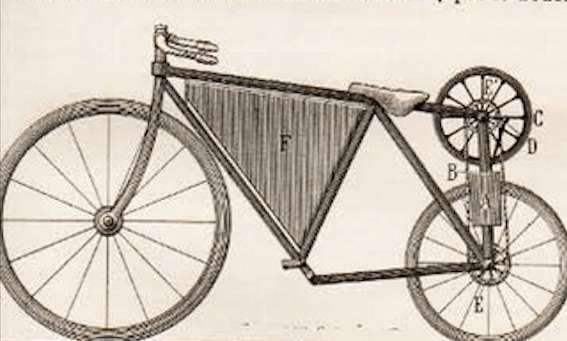

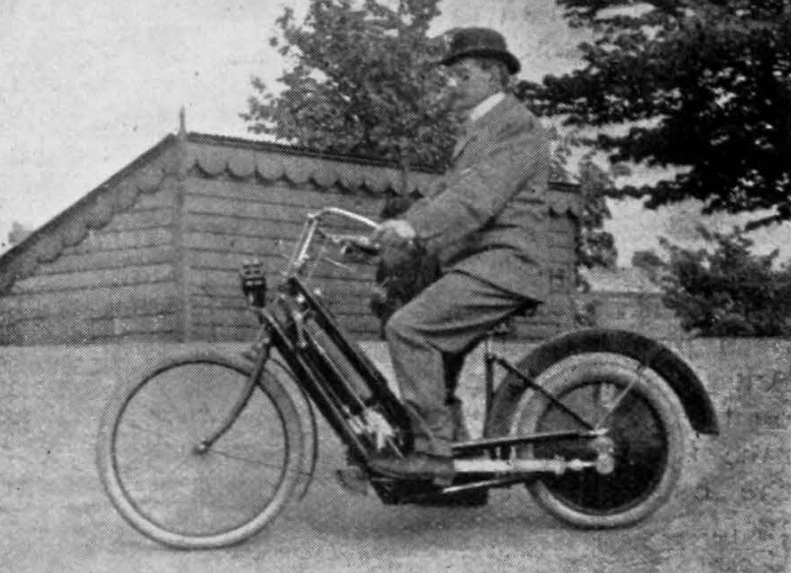

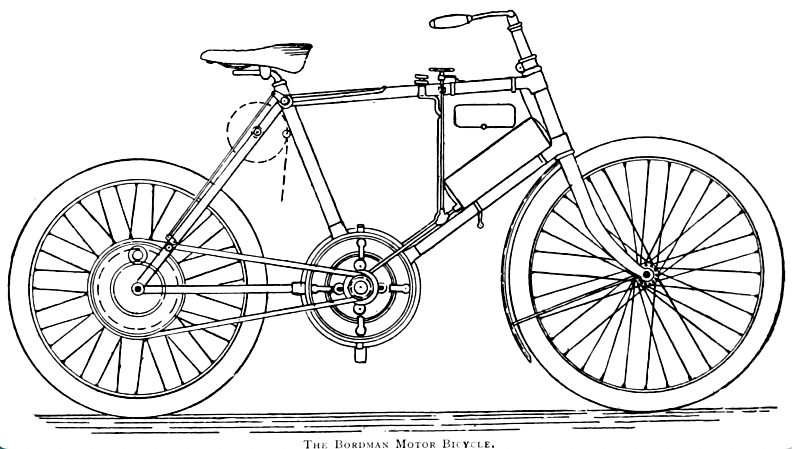

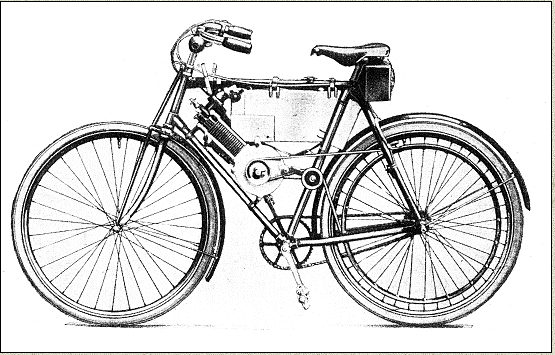

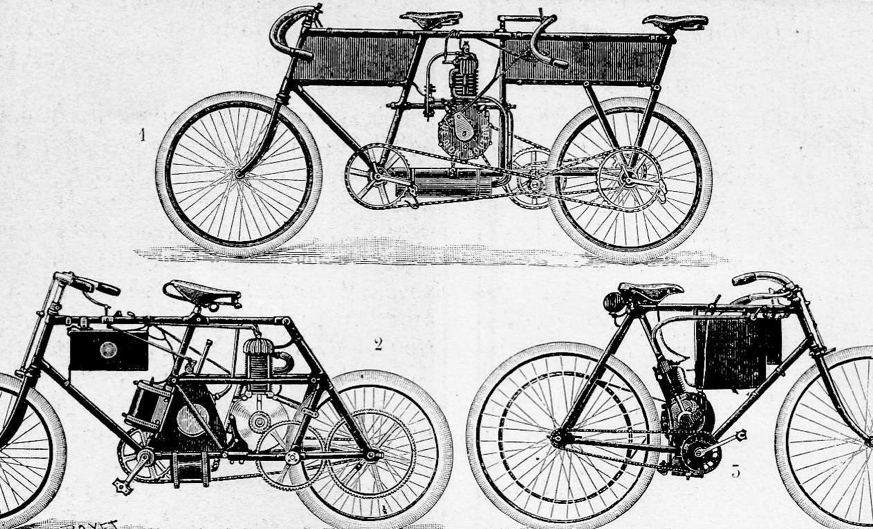

“IN THE EARLY ATTEMPTS to apply motive power to cycles, engineers were inclined to adopt the ‘safety’ for this purpose, probably because it was the most popular machine and the one most likely, in its new form, to meet with public favour. It cannot, however, be said that the bicycle driven by steam or petroleum has so far met with much success. One or two types that are being put upon the market are undoubtedly practicable machines, but they can hardly, with perfect safety, be placed in any but expert hands. The two-wheeled machine does not leave the engineer free enough to devise a motor of sufficient power and simplicity to withstand the somewhat rough usage to which it must be put upon a bicycle, nor is it always a matter of ease to start the machine or stop it in the event of the rider falling. The weight of the machinery, too, is likely to add to the gravity of any accident, while the fear of the bicycle skidding away to its own destruction is not calculated to promote the rider’s peace of mind. For these reasons, and for others it is unnecessary to enumerate, engineers now give very little attention to the bicycle, and think that the three-wheeled machine is the only one that can be safely and conveniently fitted with a motor. Some of them are being devised with powerful brakes and automatic stopping arrangements that make them perfectly safe for anyone who has the slightest idea of driving such machines. There is no doubt that the motor tricycle will very soon become quite as popular, if not more so, than the self-driven carriage.”

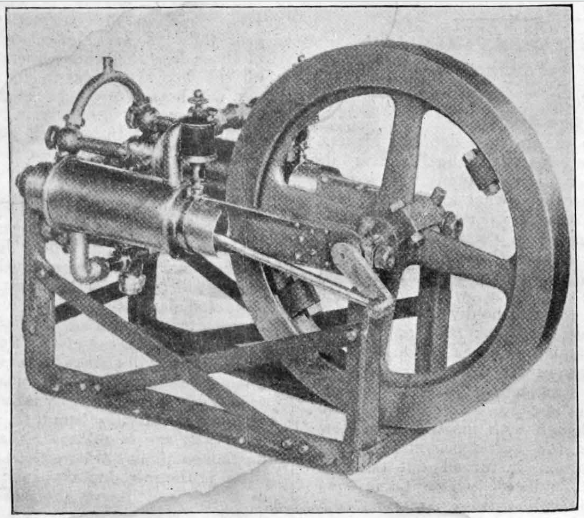

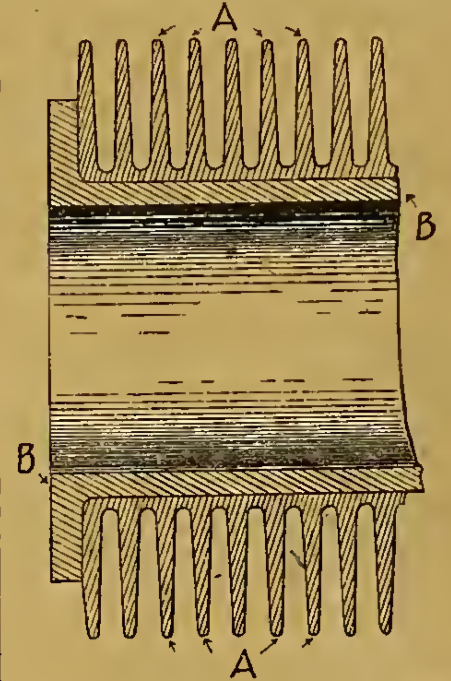

“IT WILL BE REMEMBERED that one of the rules governing the recent Chicago Times-Herald $5,000 Road Trials provided that the judges should be allowed to test the vehicles for efficiency, economy, etc. To aid them and the assisting experts in their tests, an apparatus was designed by two Chicago engineers on the lines of the locomotive testing plant at the Pardue University. It will be seen the driving wheels of the car run on a friction drum which is revolved by them when under steam, or, we should say, under vapour, and the friction drum is connected to a dynamometer. Two speed indicators, one run off the driving wheels of the car and the other off the friction drum, make it easy to deduce the mean speed of the vehicle. Besides these a draw bar pull register is fitted to register the tractive pull of the motor…the apparatus…is well designed to ascertain and register the actual power and efficiency of an autocar.”

FOLLOWING THE ROAD TRIALS, The Chicago Times-Herald asked organiser FU Adams how useful they’d been. “The influence of the contest held yesterday upon American mechanics cannot be estimated by a glance at the superficial results,” he concluded. “It is astounding that a self. propelled vehicle should be driven fifty-four miles through a sea of slush and mud at a speed which would kill any team of horses. It is remarkable that this vehicle should be guided over a course covered with pleasure carriages and crossed and cut up by railroad, cable, and electric tracks without serious accident to the drivers, or the users of the highways. But the vital question is, of what value is this demonstration, and does it settle the problem of automobile propulsion?’ The contest inaugurated by The Times-Herald has not demonstrated the perfection of the motocycle or proved its general adaptability to the various demands which are made on a street vehicle…It was the hope of the promoters of this contest that by it American inventors would be stimulated in a new and most important field, a field which, for some perverse reason, had been pre-empted abroad and neglected at home, and one in which the United States was vitally concerned. Of all countries this depends most largely for its continued supremacy upon the excellence of its transportation facilities…The response of American inventors to the offer made by The Times-Herald has never been equalled in the history of mechanical progress. In June of this year perhaps four inventors were at work on motocycles which possessed any features of practicability. Since that time five hundred applications have been filed in the patent office at Washington on inventions pertaining to this branch of transportation. Not less than two hundred distinct types of moto-cycles are now in process of construction…The American motocycle has not been produced, but the draughtsman has traced its lines and the machinist and expert will adjust its parts. This is a realisation which will come not in the remote future, but is for the to-morrow. It is the deliberate opinion of conservative capitalists and manufacturers that the Times-Herald motocycle contest has advanced the art not less than five years and saved this country untold millions in royalties which would have been paid to foreign inventors and builders. It has given direction to inventive genius in arts allied to the motocycle. It has stimulated the creation of compact motors of limited power, which are demanded in a thousand places for myriad purposes.”

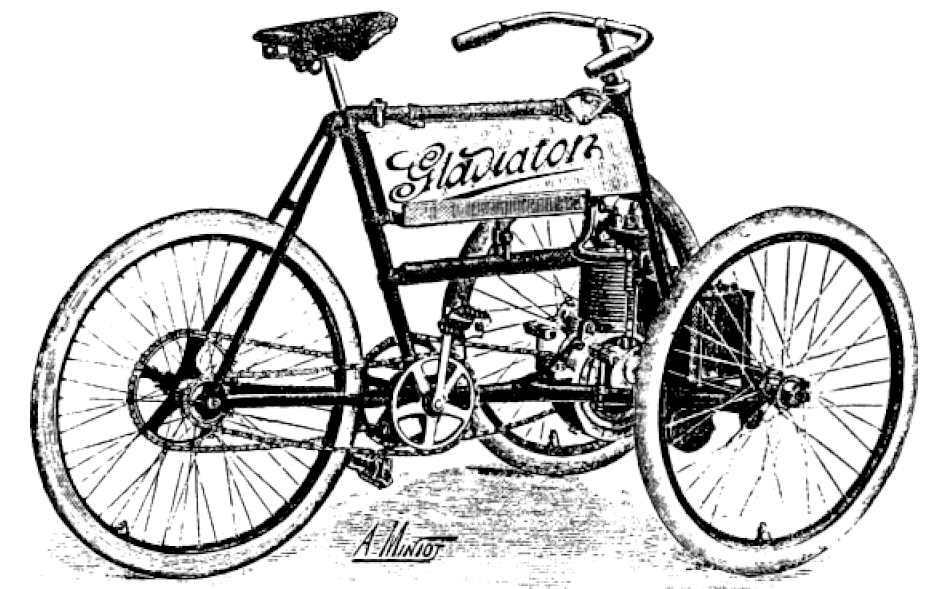

“IN FRANCE, ENTERPRISE, invention, and experiment in the direction of autocar construction is going on apace, and the success of the Daimler-propelled carriages of Peugeot Frères and Panhard & Levassor have incited much emulation. As we suggested recently, the peculiar adaptability of the cycle trade for the construction of this class of vehicle has already been recognised in France, Messrs Peugeot being already well known as cycle builders, whilst another firm, La Societé Francais des Cycles Gladiator, of Pré St Gervaise, have also been giving considerable attention to the matter, doubtless somewhat assisted by the fact that one of their principal works managers is Mr CR Garrard, one of the joint inventors of an electric autocar. This firm have for some time seen experimenting with a motor tricycle upon somewhat novel lines…we may here say that it is the result of a careful study of the adaptability of the inventions of Monsieur Beau de Rochas* and Dr. Otto [if you haven’t heard of the Otto cycle you might be reading the wrong timeline, but go on, google it, you’re secret’s safe with me—Ed] and is a four-cycle engine, the details having been so simplified that two great complications have been entirely, and, we are told, successfully, swept away, namely, the water jacket and the vaporiser. Like the Pennington and some other engines, the ignition of the charge is effected electrically, a small button making or breaking the contact. This being so readily done, we are informed, that the crowded boulevards are daily traversed with more safety when they are in a greasy condition than by a rider upon an ordinary safety bicycle. The store of mineral naphtha carried is sufficient for a run of about nine hours, and as no fire is employed, the fear of the liquid catching fire is altogether removed. The tricycle itself is built upon a principle formerly somewhat largely experimented with in this country, having a single driving wheel, and steering with two wheels swivelled upon a centre something like the front wheels of an ordinary four-wheeled carriage. The tricycle was originally studied as a stepping point to the regular autocar, or land yacht, as some of our French friends are inclined to term it, but turning out so well, and working so successfully, the Gladiator Co have put a number of them in hand, in addition to a tandem quadricycle and a light carriage. The total weight of the tricycle with its engine is 50kg, or about 110lb, and the power developed is three-quarter horse. The side wheels are constructed upon folding axles, so that the total width of the machine may be reduced by some five inches, which enables it to be readily wheeled into an ordinary house doorway. Some little time back, Mr Garrard brought one of the early samples of this machine on to the celebrated Velodrome Buffalo cycle track in Paris, and rode it between the races which were going on at the time. The public were not a little surprised at the audacity of the rider, who went off for ten yards with the pedals, then held the pedals still, and let the motor go, attaining a speed of some 29 kilos per hour, following this up by a sort of fancy riding exhibition, as the construction of the machine enables it to be ridden by a skilled cycle rider upon two wheels only, either of the two front steering wheels being able to be raised from the ground by leaning over in the opposite direction, and then steering the machine on its two wheels like a bicycle. We may further add that Mr Garrard himself is present at the Stanley Cycle Exhibition at the Agricultural Hall, which opened yesterday (Friday), and has with him specimens of the tricycle in full working order, where we have no doubt many of our readers will make a point of inspecting it.”

*Alphonse de Rochas; you’ll find him in the gallimaufry.

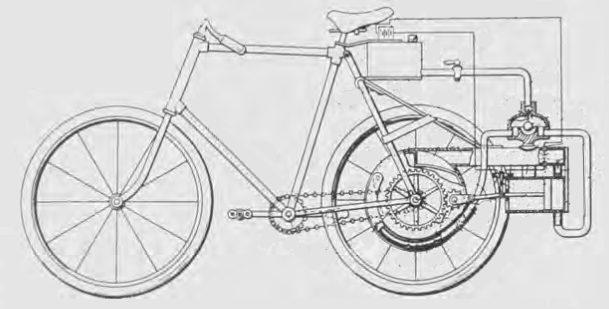

“A GENTLEMAN LAST WEEK applied to the Hove Police Committee for permission to introduce a tricycle partially propelled by electricity and petroleum into the town. It was not intended to let the motor do all the work; but simply to use it as a help to pedalling. The authorities, however, considered they had no power to grant the request, and for the present, therefore, the new invention is excluded from Hove.”

“NEW PATENT 21,167: J McKenny and FL North, ‘The utilisation of compressed air in the operation of driving cycles and other similar vehicles.'”

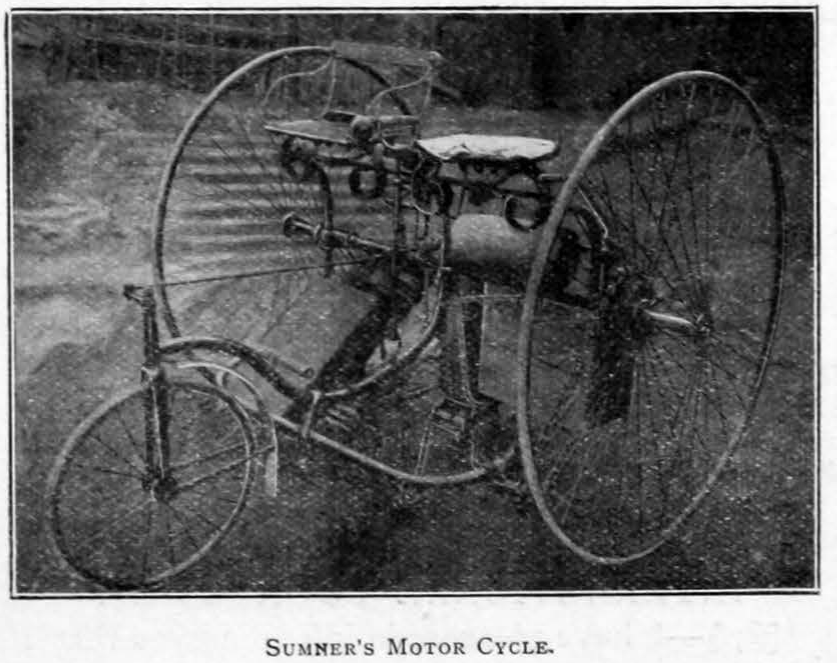

“THE STEAM TRICYCLE OF 1881. By Arthur H Bateman. In accordance with your request, I now give your readers the history of this machine. In the summer of 1880, my friend, Sir Thomas Parkyns, Bart, patented the application of steam to a tricycle or quadricycle, and constructed a vehicle that truly ran by steam, and was provided with a condenser, but as this latter appendage became too hot to work within a few minutes, there was little practical value in the whole affair. The idea was there, and the thing worked, but much had to be done before any claim could be reasonably made to call it a practical road carriage. At this stage the patentee placed the matter in my hands, and experiments began in earnest. Modifications in many details were immediately made; the con-denser was radically improved, and before long the time of continuous running was extended from a few minutes to about an hour, when a pail of cold water gave another hour, and so on. At this stage an additional 100lb of dead weight in the form of storage water for condensing was the alternative to frequent stoppages to obtain the same at a convenient horse-trough or