1870

JULIUS HOCK made an engine which “took in a charge of air and light petroleum spray” but relied on a flame jet for ignition.

JAMES BEGAN to make bicycles in Birmingham.

AMERICAN DR JW Carhart, professor of physics at Wisconsin State University, and the JI Case Company built a steam car that won a 200-mile race.

CARLESS, BLAGDON & CO, a chemical company based in Hackney Wick, came up with a solvent which was commonly used to remove nits. It was marketed as ‘Petrol’.

1871

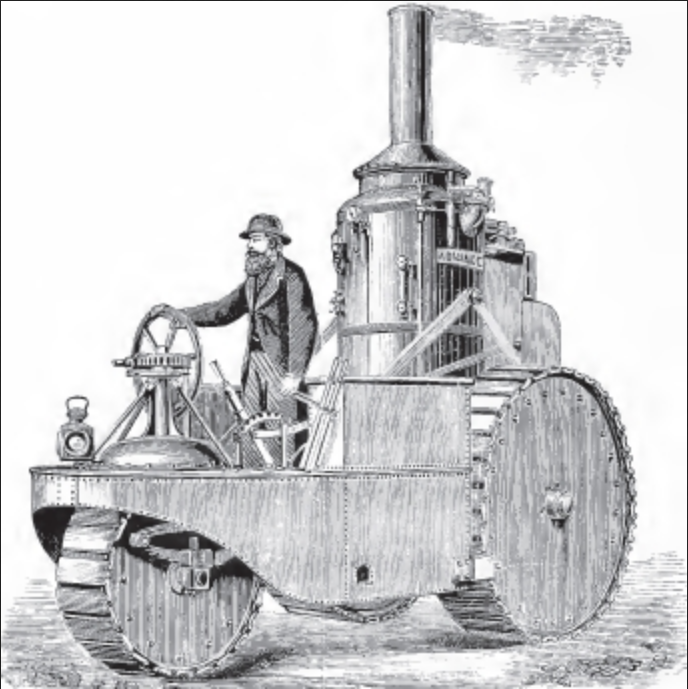

RW THOMPSON, WHO HAD cut his steam teeth working for the Stephensons, built a series of steamers but when demand exceeded his production capacity he called in another locomotion pioneer, Messrs Ransomes, Sims & Jefferies of Ipswich. This firm, which dated back to the 18th century, built a roadster called the Chenab (one of a batch destined for India) and sent it under its own steam to the Royal Show at Wolverhampton. Its stablemate, the Ravee, was driven from Ipswich to Edinburgh and back, covering 866 miles at an average of just over 6mphwith an occasional sprint at 20mph.

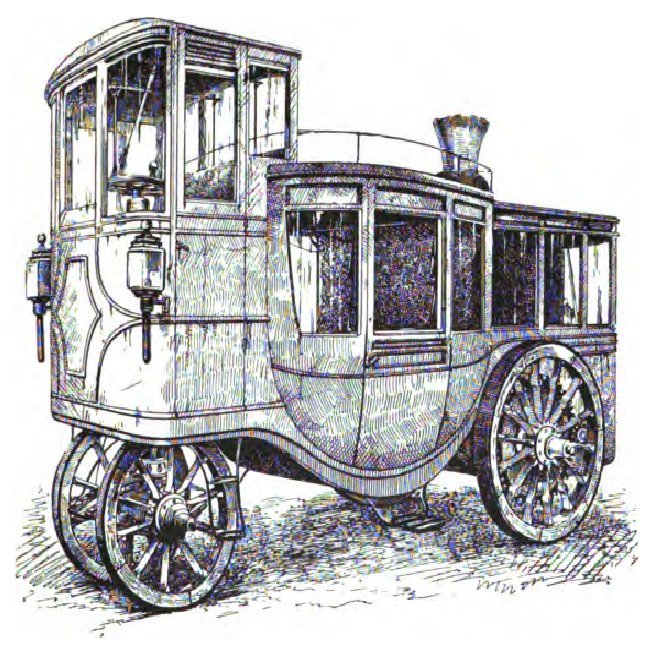

A STEAM-DRIVEN MOTORCAR made by Messrs. Tange Bros, Birmingham was designed for use in India, as UK legislation prohibiting the use of motorcars did not apply there. It featured a vertical boiler and side cylinders driving direct. The driver sat in front and stoker also was required. It boasted a foot brake, side lamps and a light canvas awning. The car might be better described as a charabanc as it was an eight-seater; the makers claimed a top speed of 25mph and boasted it could climb any gradient with the greatest ease. It was priced at £800.

1872

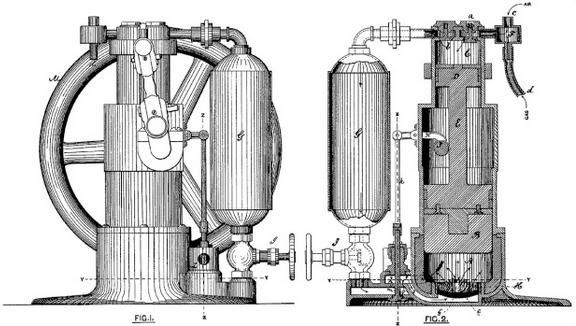

GEORGE BRAYTON OF Boston, Mass patented the first in a series of internal combustion ‘hydro-carbon engines’; they were fuelled by gas or vapourised fuel oil such as naptha. Ignition was by flame and engine pressure was about 45psi. They became known as Brayton Ready Motors because, unlike ‘external combustion’ steam engines these engines were available for immediate use. They worked on the constant-pressure Brayton cycle; pressure in the engine’s cylinder was maintained by the continued combustion of injected fuel as the piston moved down on its power stroke. This system is used in gas turbines and jet engines and is similar to the Diesel cycle. Over the next few years Ready Motors were built from 2.25lit (1hp, 408kg) to 19.3lit (10hp, 1.8 tonnes). They worked in factories as stationery engines, and powered boats, PSVs, automobiles and the Holland 1, the USA’s first submarine. These engines played a critical role in the development of the modern internal combustion engine. Hundreds were made; six still exist.

1873

JAMES CLERK MAXWELL published A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, based on four “linear partial differential equations” [don’t asked me; I scraped a grade 6 O-level in General Science] but Einstein considered the “change in the conception of reality” brought about by Maxwell “the most profound and the most fruitful that physics has experienced since Newton.” Suffice to say it laid the groundwork for moden motor cycle ignition, lighting and much more from powder coating to ABS and ASR.

AMEDEE BOLLEE of Le Mans built the first of a series of advanced steam cars.

IN WEST LONDON EH Levaux proposed a clockwork car that would be wound up by roadside engines. A number of 2hp engines were built but the weight of the steel springs killed the scheme.

BELGIAN ZENOBE Gramme opened a dynamo factory.

LOUIS ERRANI and Richard Anders of Liege patented a ‘hydrocarbon liquid’ engine.

SIEGFRIED MARKUS, who we met in 1864, exhibited an improved version of his petrol-fuelled car at the Vienna Exhibition.

1874

JOHN HENRY Knight, an amateur inventor from Farnham, Surrey, built a steam trike, or “voiturette”.

MESSRS BAYLISS, Thomas and Slaughter teamed up to make bicycles in Coventry under the trade name Excelsior.

TRACTION ENGINE builders Brown & May of Devizes, Wilts developed a steam truck with a four-ton payload and chain drive via a differential. It was a bit of a blind alley, as loaded traction engines were simply too heavy for contemporary roads but nonetheless it was a truck. And without trucks how would motorcycles and spares parts reach the dealers?

1876

OTTO-LANGEN & CO continued to develop their four-stroke gas engine; by 1876 their Deutz company had built 2,700 of them. Early models were notoriously noisy and the vibration could damage foundations but they were more fuel efficient than steam engines. In its final form the ‘Otto Silent’ gas engine is the ancestor of countless modern four-strokes. It was developed with the help of technical manager Willhelm Maybach who brought in a young gunsmith called Gottleib Daimler. As the engines were made smaller and smoother Maybach and Daimler realised that with a portable liquid fuel they could be made small enough to propel road going vehicles and laid their plans accordingly.

1877

OTTO-LANGEN & Co and the Crossley Brothers, Francis and William, jointly patented the four-stroke cycle: induction, compression, ignition, exhaust. All together now, “Suck! Squeeze! Bang! Blow!”

MR MEEK OF Toward & Co, Newcastle upon Tyne, built a lightweight steam trike that was more like a bike than a coach; it worked well.

GEORG LIECKFELD of the Hanover Machine Works, modified a two-stroke opposed/piston engine patented by Ferdinand Kindermann into a four-stroke. The Kindermann-Lieckfeld engine ran on ‘town gas’. The patent, granted to Lieckfeld’s boss Conrad Krauss, also covered a friction clutch, cam-operated inlet valve and a reverse gear.

1878

BRITAIN’S ‘RED Flag’ Act was revised to do away with the red flag, but every road going self-propelled vehicle still had to be preceded by a man to warn drivers of horse-powered vehicles. This was despite a parliamentary committee report in 1873 which strongly recommended the removal of all restrictions on vehicles under six tons, which would have put them on equal terms with horsedrawn transport.

SHOZO KAWASAKI set up the Kawasaki Tsukiji Shipyard in Tokyo.

DUGALD CLERK began work on his own engine designs after modifying a Brayton engine (see 1872). He later wrote: “This Brayton engine provided my first experience of an engine operated on the compression principle…I saw at that time, after making this test, that the Brayton engine could be altered with but little trouble to operate as an explosion engine, exploding under compression…I then proceeded to alter the Brayton engine. The first alteration consisted in rearranging the inlet valve and providing a spark plug to ignite the mixture electrically. The electrical ignition was made by a built-up spark plug, similar to the Lenoir engine, with the construction of which I had become at this time familiar…This experiment proved that the Brayton engine, working as an ordinary engine, gave more power than working in the ordinary flame method…”

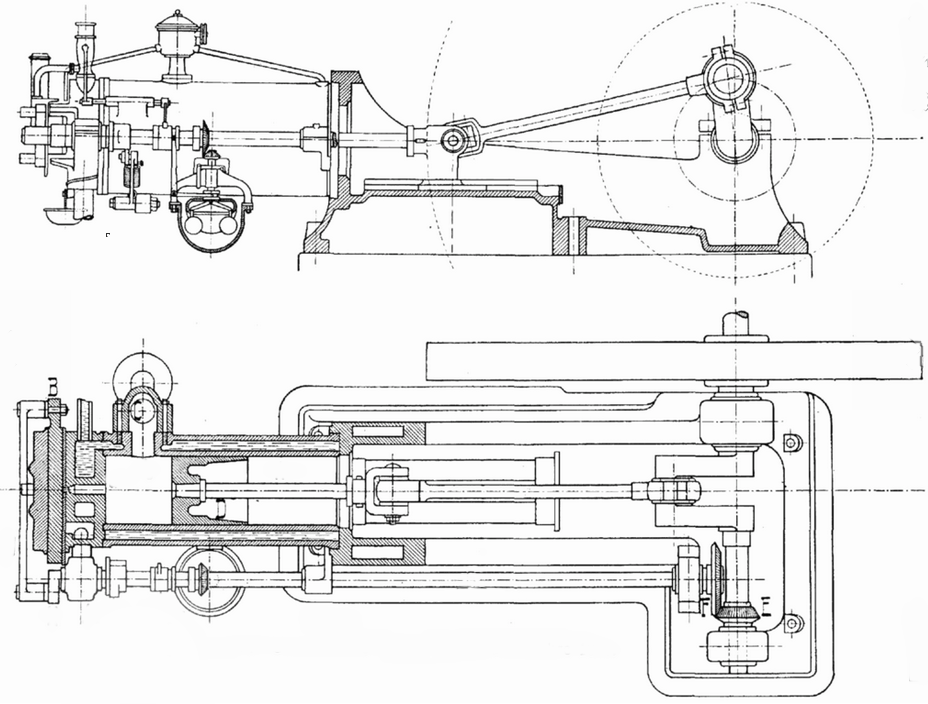

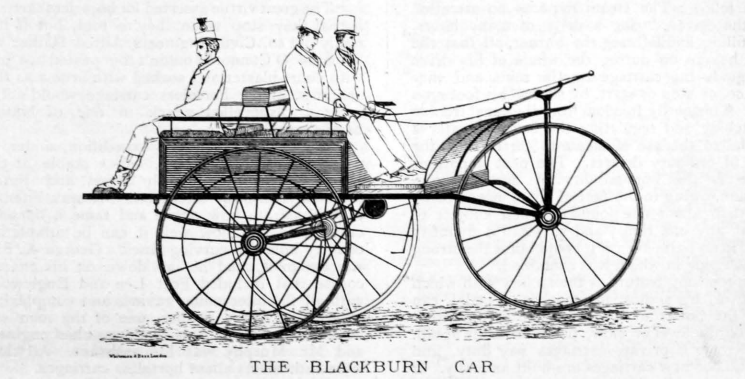

THIS REPORT APPEARED in The Field: “An invitation reached me a short time since to inspect a new vehicle, termed the Blackburn car. I was quite ignorant of the nature of the invention, and may therefore describe it as it was shown to me by Mr Blackburn. On presenting my credentials, I was informed that the machine was not in action, but that it should immediately be set going for my inspection. Opening the doors of a shed, the inventor pulled out a carriage which closely resembled an ordinary dogcart, but with this difference, that the shafts were very short and inclined together, meeting about two feet in front of the splash-board between them was third wheel working on an upright shaft, which was capable of being turned by a horizontal handle, in the same manner as the driving wheel of a bicycle. This handle was worked by reins which were held in the hands of the driver. For a few seconds I was puzzled as to the motor power, as I saw no signs of any, the whole contrivance being represented with sufficient accuracy in the annexed sketch; but going to the hack, Mr Blackburn lifted an opening, and striking a match placed it in the interior. He apologised for keeping me about a minute and a half while he turned a small handle, like that of a coffee mill, and then blandly invited me to get up. I did so, not without a slight twinge of remorse at the recollection that I had no policy in the Accidental Death Insurance Company. ‘Are you ready?’ ‘All right,’ I answered; but whether we were bound for Edenbridge or the Devil’s Dyke I did not know. Our course lay over a piece of rough waste ground; in some places there was no roadway; further on a corduroy road of railway sleepers was laid to afford a passage for brick carts over the uneven surface; now we were on level ground, then we went down a slope between two bushes that barely gave our vehicle room to pass. Again we turned sharply round an ugly corner, when I mentally resolved to insure for £1,000 if I were but spared this time. During all these wanderings, including some gyrations in a 20ft ring, we had been going at the rate of about eight miles an hour, when we approached a very awkward declivity. I accidentally, as it were, wondered whether it was possible to stop easily, when the machine was pulled up with a suddenness that nearly sent me on to the horse’s back—I beg pardon, on to the guiding handle. We then started at a slow pace, which was quickened at will until the full speed was obtained. This amusement lasted for about half-an-hour; when Mr. Blackburn asked me if I was quite satisfied with the practicability of the car, and its capability of being directed easily, and of being arrested, slowed, or quickened in its action, I could truly answer in the affirmative. I then dismounted and requested some enlightenment as to the modus operandi of this magic car, which was most fully and courteously given.

The motive power is obtained by the combustion of benzoline, a small jet of which is admitted into the burner. It is then set on fire, and is completely consumed up a current of air, which until the machine is in action is produced by turning the small handle already alluded to. The burner, about the size of an ordinary chimney-pot hat, and quite as elegant, is lined by coils of a copper tube containing water; this tube is calculated to bear 2,000lb on the square inch, and in working only receives 60lb; so that practically it is not likely to burst, and if such an accident did occur, the result would not be serious as the whole tube only contains a pound of water. The steam generated in the tube passes at one end into the cylinders of a small torpedo engine, which rotates a horizontal shaft; It then passes into a cooler, where it is condensed by the effect of a current of cold air driven against the outside of the vessel by a revolving fan, and the water so produced is forced back into the other end of the tubular boiler by a force pump; hence there is not the slightest escape of steam, nor is there any smoke, as the benzoline is entirely consumed by the current of air. The revolving engine shaft works the driving shaft, not directly, but by the medium of two cones placed side by side, their bases being reversed in position. A figure-of-eight band connects the two, and as it is moved towards the base of one it nears the apex of the other, and thus increases or diminishes the speed of the driving shaft, which, as is shown in our sketch, is connected with the driving wheel, or off wheel, by an endless band…I was much surprised at the efficacy of the machinery, and look upon it as a germ of what may not improbably prove a great revolution in our means of conveyance on common roads…The steam requires no attention from the driver during a drive of many hours. After filling and lighting the burner, all that the driver has to do during the whole of his drive is to guide the carriage by the reins and vary the pace, or stop or start, by sliding his foot on a pedal…The present carriage travels at about eight miles an hour on the level and about four miles up moderate hills. The weight of the steam power does not add to the weight of an ordinary dogcart more than about 180lb. The long distances which can be covered day by day beyond the capabilities of a horse, and the absence of all expense when not actually in use, combined with the small cost of three-halfpence per mile for the benzoline, renders it probable that light carriages of this description will be found to supply a great want among a very large number of people, to whom cheap, private conveyance is of much importance. As these vehicles make no smoke or objectionable noise, and are as much, or under control than a horse, and are not unsightly, it may be confidently expected that an amendment to the Highways Act will be obtained freeing carriages of this description from the restrictions still imposed on traction engines.”—WB Tegemeir.

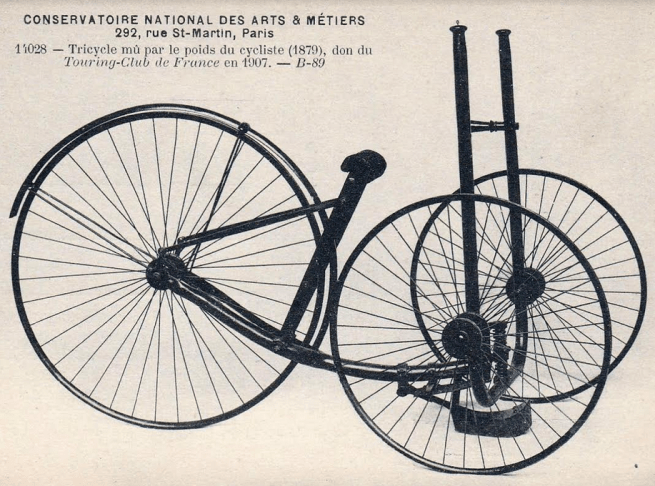

1879

KARL BENZ patented a two-stroke engine which he had designed the previous year. His other patents included spark ignition using a battery, the spark plug, the carburettor and the clutch.

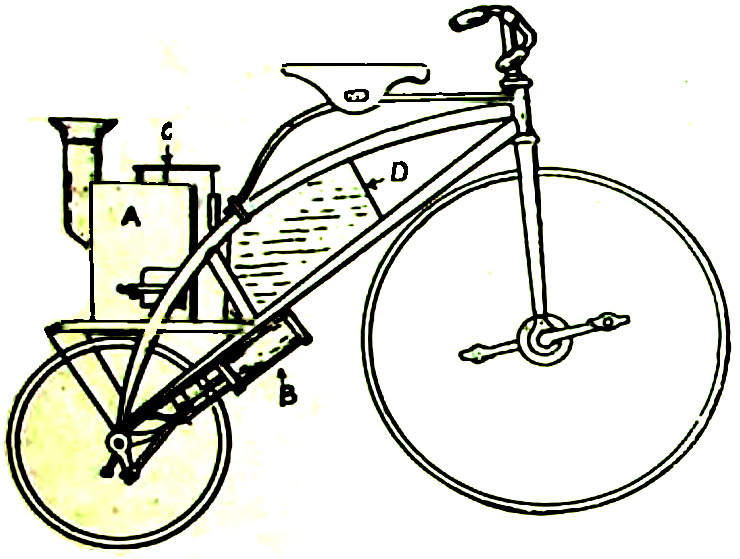

ITALIAN GUISEPPE Murnigotti of Bergamo patented a motore atmosferico al velocipede with a ½hp four-stroke parallel twin fuelled by coal gas and driving the front wheel via conrods. Steering was by tiller to the rear wheel so it’s probably A Good Thing it was never built.

EDOUARD DELAMARE-Deboutteville of Rouen invented a ‘universal machine’ capable of cutting, milling, drilling and turning.