1820

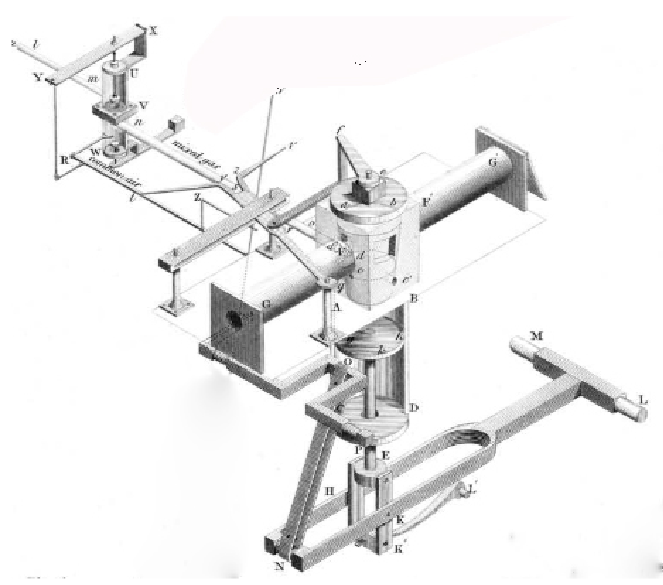

“ON THE APPLICATION OF HYDROGEN GAS to produce a moving Power in Machinery; with a Description of an Engine which is moved by the Pressure of the Atmosphere upon a Vacuum caused by Explosions of Hydrogen Gas and Atmospheric Air. By the Rev W Cecil, MA, Fellow of Magdalen College, And Of The Cambridge Philosophical Society. [Read Nov 27, 1820.] The engine, in which hydrogen gas is employed to produce moving force, was intended to unite two principal advantages of water and steam; so as to be capable of acting in any place, without the delay and labour of preparation…The general principle of this engine is founded upon the property, which hydrogen gas mixed with atmospheric air possesses, of exploding upon ignition, so as to produce a large imperfect vacuum. If two and a half measures by bulk of atmospheric air be mixed with one measure of hydrogen, and a flame be applied, the mixed gas will expand into a space rather greater than three times its original bulk. The products of the explosion are, a globule of water, formed by the union of the hydrogen with the oxygen of the atmospheric air, and a quantity of azote [nitrogen], which, in its natural state, (or density 1), constituted .556 of the bulk of the mixed gas. The same quantity of azote is now expanded into a space somewhat greater than three times the original bulk of the mixed gas; that is, into about six times the space which it before occupied: its density therefore is about ⅙th, that of the atmosphere being unity. If the external air be prevented, by a proper apparatus, from returning into this imperfect vacuum, the pressure of the atmosphere may be employed as a moving force, nearly in the same manner as in the common steam-engine: the difference consists chiefly in the manner of forming the vacuum. An engine upon this principle is found in practice to work with considerable power, and with perfect regularity. The advantages of it are that it may be kept, without expense, for any length of time in readiness for immediate action; that the engine, together with the means of working it, may easily be transferred from one place to another; that it may be worked in many places where a steam engine is inadmissible, from the smoke and other nuisances connected with it; a gas engine may be used in any place where a gas light may be burnt; in places which are already supplied with hydrogen for the purpose of illumination, the convenience of such an engine is sufficiently obvious. It may be added that it requires no attention so long as it is freely supplied with hydrogen. The supply of hydrogen is obtained, either from a large gazometer, which may be at any distance from the engine, or from a number of long copper cylinders filled with condensed hydrogen. In the latter case, the engine, with the apparatus for working it, will be transferable from one place to another. For pure hydrogen may perhaps be substituted carburetted hydrogen, coal gas, vapour of oil, turpentine, or any ardent spirit: but none of these have been tried; nor is it expected that any of them will be found so effective as pure hydrogen…In the model exhibited to the Society, the capacity of the working cylinder is about thirty cubic inches; which, at the rate of sixty revolutions in a minute, requires 1,800 cubic inches of mixed gas, or 450 cubic inches of pure hydrogen; the hydrogen being taken at one fourth part of the mixed gas. This multiplied by 60, gives 15.6 cubic feet of hydrogen for the consumption in one hour: and to this must be added two more cubic feet of pure or carburetted hydrogen for the supply of the gas light during the same time, making altogether about 17.6 cubic feet in an hour.”

1821

DAVID GORDON took out a patent for “improvements in wheel carriages”. His ideas included mounting the engine inside a sort of giant hamster wheel in the form of a cylinder 9ft in diameter and 5ft long. Teeth round the internal circumference meshed with the running wheels of an engine much like Trevithick’s. This caused the wheels of the carriage to climb up the internal rack of the large cylinder, making the cylinder roll forward, propelling the vehicle by means of side rods. Obvious when you come to think of it.

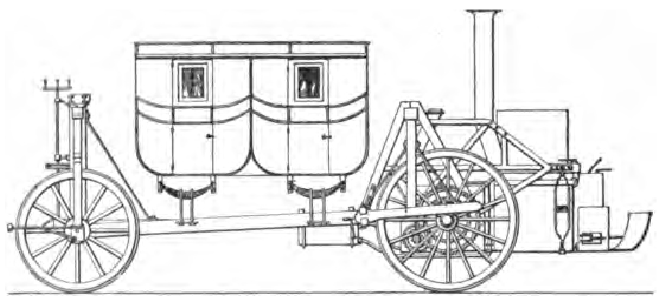

JULIUS GRIFFITHS of Brompton had a carriage built by the locksmith firm Bramah. It was designed to carry three tons at 5mph and was patented in England, Austria and the USA. It was also a flop, otherwise it might have been the first commerical vehicle.

1822

GOLDSWORTHY GURNEY, later to earn fame as a pioneer of steam-powered PSVs, built what was probably the first engine to run on ammonia. He claimed: “Elementary power is capable of being applied to propel carriages along common roads with great political advantage, and the floating knowledge of the day places the object within reach.” He was said to have used his amonia engine to power “a little locomotive”.

1823

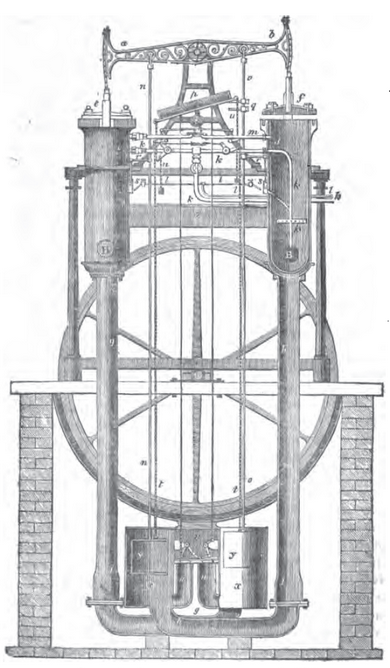

SAMUEL BROWN patented a gas engine adapted from Newcomen’s athmospheric engine. Like Cecil’s engine it relied on burning gas to expel the air from a vertical cylinder, but cold water was injected to “condense the flame and produce a vacuum”. Mechanics Magazine reported that one of his multi-cylinder engines had raised 300 gallons of water 15ft on a cubic foot of gas.

BRITISH INVENTOR (and qualified doctor) Sir Goldsworth Gurney, inspired by his chum and fellow Cornishman Richard Trevithick, built a model steam carriage; as we’ll see he would have an illustrious record with the real thing.

MACINTOSH USED rubber gum to waterproof cotton–and we all need waterproof riding gear.

1824

WALTER HANCOCK began to work on the first of a series of steam-powered coaches.

T BURSTALL OF Edinburgh and J Hill of London teamed up to patent and build an innovative steam coach featuring the ‘flash boiler’ technology which made later steam cars practicable. It was also the first vehicle to boast four-wheel drive—not directly relevant to our story but still damned clever.

MORE FEET! David Gordon built a coach he called The Comet featuring a modified version of William Brunton’s walking-carriage design; there was a view at the time that wheels alone would not have enough friction. As with Brunton’s walker, three wheels took the weight of the vehicle while six legs pushed it along, much like a nipper on a scooter. [Exactly 124 years later Corvair would build the B36 bomber with six propellors and four jets; a USAF wag described it as “six turning, four burning”. A Georgian wag might have remarked that The Comet had “three rolling, six strolling”] . Innovations included a rotary drive to the legs, described a ‘propellers’, for a smoother action. The propellers were formed of iron gas-tubes, filled with wood, to combine lightness with strength. According to a contemporary description: “To the lower ends of these propelling rods were attached the feet, of the form of segments of circles, and made on their under side like a short and very stiff brush of whale-bone, supported by intermixed iron teeth. These feet pressed against the ground in regular succession, by a kind of rolling, circular motion, without digging it up.” It took more than six years of experiments with four walking carriages to convince Gordon that wheels beat legs. Pity though; instead of mopeds we might have had been riding bipeds.

WILLIAM JAMES built a 20-seat steam coach featuring a double-cylinder engine on each rear wheel. This gave each driving wheel an independent source so power and speed could be varied for turning corners. Its turning radius was said to be less than 10ft—considerably more nimble than a 21st century minibus.

1825

GREAT DANE HANS Christian Orsted produced tiny amounts of aluminium (8% of the planet’s crust is made of aluminium; not a lot of people know that). It’s lighter than cast iron, of course, but as Ariel VB owners will know, the other difference is that iron heads don’t warp. Orsted was also a pioneer in the field of electromagnetism, which led to magnetos, dynamos, alternators, starter motors, regulators and solenoids. Nice one Hans.

GURNEY PATENTED and built a full-size version of his walking carriage and drove it up Windmill Hill, near Kilburn in North London. It weighed 1½ tons, had 21 seats and was rated at 12hp. The legs were found to be superfluous so he removed them.

JA WHITFIELD OF Bedlington Ironworks reported that one of Sam Brown’s gas engine was fitted into a carriage with 5ft wheels, a wheelbase of 6ft 3in, a track of 4ft 6in and a tare, including gas and water, of a ton. The bore/stroke were 12x24in. In May this carriage climbed the steepest part of Shooter’s Hill in South-East London (“a gradient of more than 13in in 12ft”) “with considerable ease”

SAMUEL BROWN fitted his ‘gas-vacuum’ engine to a carriage which climbed Shooter’s Hill in South-East London “to the satisfaction of numerous spectators”.

1826

SAMUEL MOREY patented an internal combustion ‘explosive engine’. It was fuelled by a gas/air mixture via a carburettor and featured cam-driven poppet valves with tappets, a crank and a flywheel. He also experimented with spark ignition but failed to find backing to develop his dream of “drawing carriages on good roads and railways and particularly for giving what seems to be much wanted direction and velocity to balloons”.

1827

THE BROTHERS Johnson of Philadelphia built a carriage with a bottle-shaped boiler, 8ft wooden rear driving wheels and much smaller front wheels. It worked well but “was sometimes altogether unmanageable” and caused considerable damage to local buildings.

MESSRS POCOCK and Viney attached kites to a light gig and rode in it from Bristol to London but they carried a pony on a platform at the rear “to make the carriage available when the wind did not serve”. They claimed to have regularly topped 20mph.

FRIEDRICH WÕHLER made aluminium by reacting potassium with anhydrous aluminium chloride.

HANCOCK PATENTED a steam boiler incorporating separate chambers of thin metal which could split rather than explode, a safety measure for operators and passengers alike.

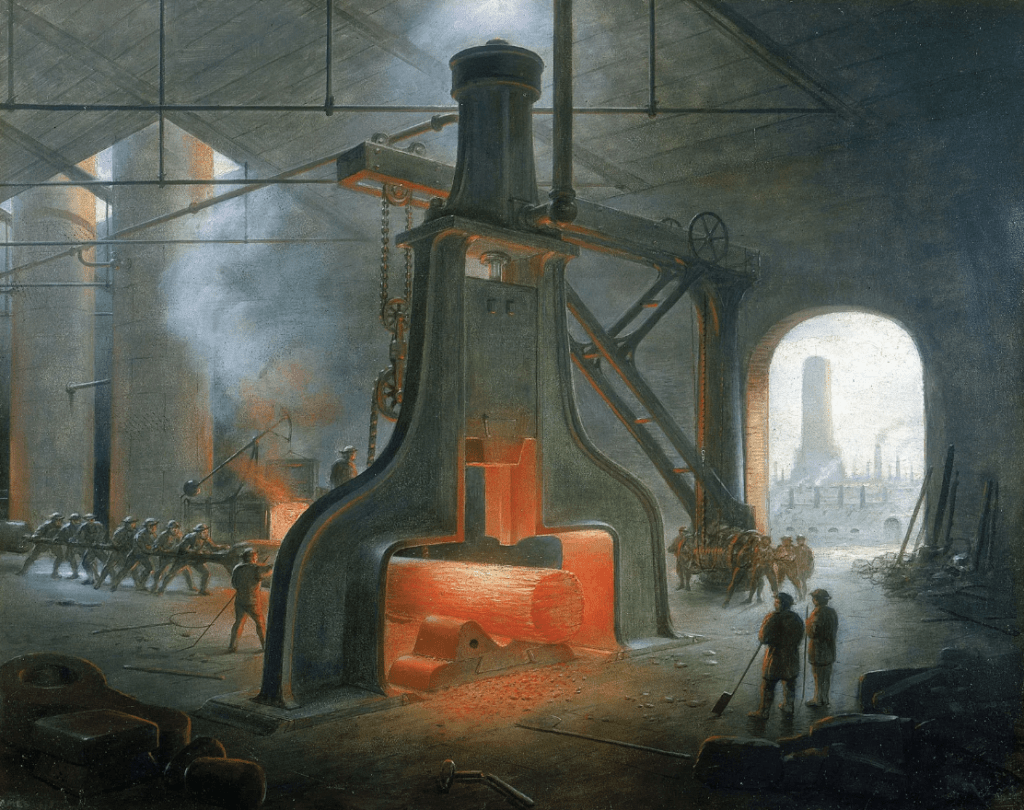

JAMES NASMYTH, WHO designed and made the steam hammer that was used on the drive shaft of Brunel’s Great Britain, also produced steam engines and locomotives. In 1827, aged 19, Nasmyth took delivery of a four-wheel steamer made by the Anderson foundry at Leith. For some months it made reguklar runs between Leith and Queensferry carrying eight passengers.

DR HARLAND OF Scarborough (whose son Edward was the Harland half of the shipbuilding giant Harland and Wolff) patented an advanced “steam carriage for running on common roads”. A working model was produced but the full-size carriage was never completed.

1828

THE WESTERN TIMES reported: “We were much gratified a day or two ago by witnessing a novel exhibition on the Hammersmith road of a large carriage propelled by a Gas Vacuum Engine, which rolled along with great ease, at the rate of seven miles per hour. There were several gentlemen in and upon it, who appeared quite satisfied of its power and safety. The public are indebted to Samuel Brown, Esq of Brompton, for this valuable discovery, who has been indefatigable in his exertions to bring it to its present state of perfection!’

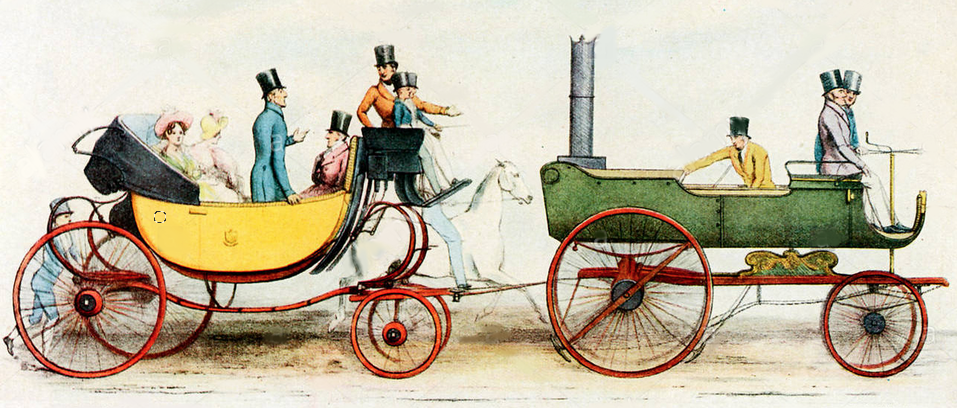

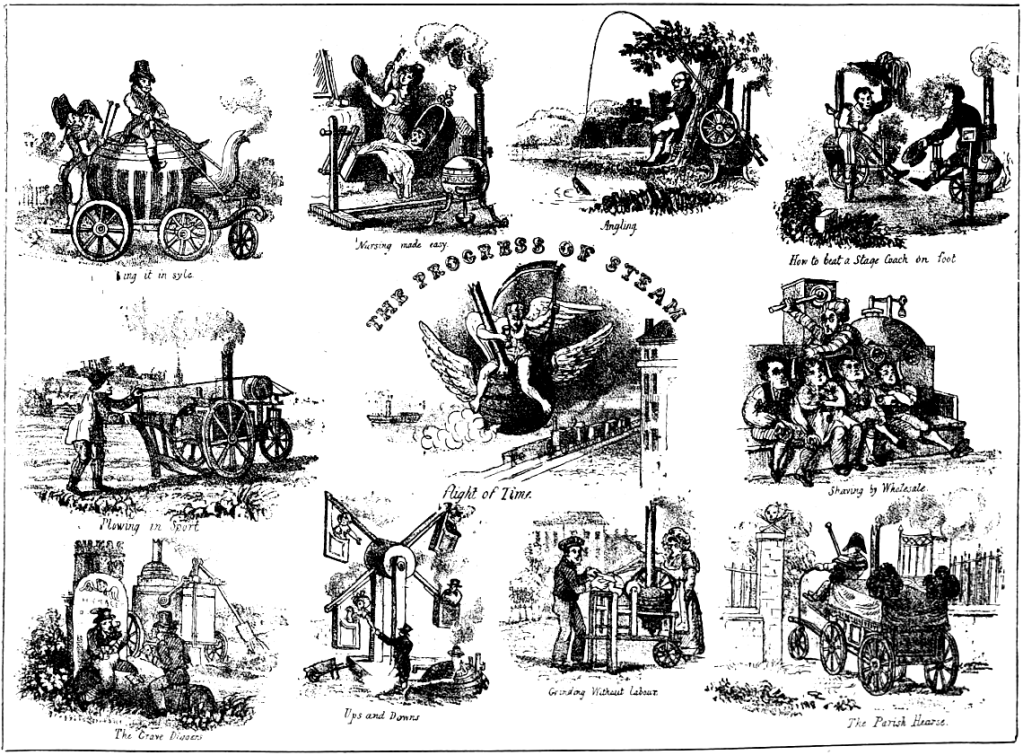

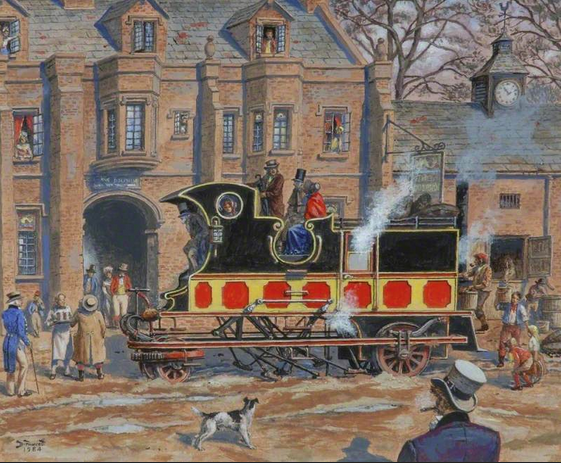

TWO YEARS BEFORE the first railway Blackwood’s Magazine looked to the future: “The most novel application of that most powerful of all agents, Steam, is now coming before the public in a form which at least promises practical effects. Gurney, an ingenious chemist and mechanician, has, after various attempts and failures, brought his steam carriage into a state allowing of actual experiment on the road. It some time since ran up Highgate Hill, a very steep ascent, at the rate of probably ten miles an hour; but its descent was more formidably rapid, for the pilot (better word than chauffeur, that!) was unable to guide its velocity, and it tore off one of its wheels. To be run away with by a horse of this kind, that would think nothing of whirling carriage, passengers, and all, into the third heavens, or dissolving them to a jelly in the face of mankind, was too perilous an adventure to be assured of popularity. In the meantime another engineer sent another steam carriage to perambulate the streets, but his name was the most disastrous imaginable for the purpose. An old Roman would have pronounced him destined by Fate never to prosper in steam apparatus, for the name was Burstall. The omen was true, for the carriage blew up, and boiled and parboiled several scientific spectators, doing at the same time the good work of washing the faces of the mob far and wide…But this machine has one grand defect, that the steamery is under the feet of the passengers…Where the journey may end, whether at Bristol or in the other world, is the problem…The engineer protests, by all the names of philosophy, that a blow up is utterly impossible. But in the modern philosophy the most impossible things have come to pass so often that a man attached to his own vertebrae may well be allowed to indulge a little scepticism…The machine will never be entitled to popularity, until the chance of blowing up is entirely out of the question; which it can scarcely be while the steam engine forms a part of the carriage. It must be detached, and at some distance from the carriage, and be not a steam coach, but a steam horse…and to this construction the machine will naturally come…Where we obtain a new power over Nature, we have a new source of national wealth; and no matter what it may displace for the moment [such as the huge industry surrounding horse powered transport], we are sure that it will replace the loss by ten times, or a thousand times, the gain.”

1829

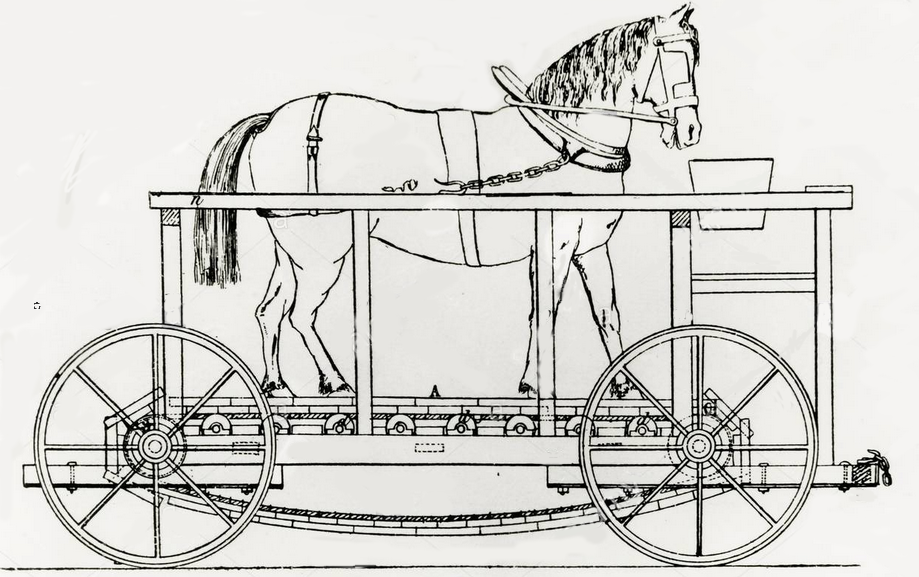

IN FEBRUARY 1829 Gurney drove one of his steam carriages 212 miles from London to Bath and back at an average of 15mph. Gurney’s pioneering run was made at the request of the Quartermaster General of the army who clearly grasped the advantage of moving troops and equipment at high speed. Gurney boosted the power of his engines with a high-pressure steam jet. The ‘Gurney Jet’ was applied to Stephenson’s Rocket locomotive for the Rainhill Trials on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in October 1829, and to steam carriages. Stevenson also claimed responsibility for Brandreth’s Cyclopede, powered by a horse on a conveyor belt, that competed at Rainhill but only managed 6mph.